Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Writing It Up: A Step-by-Step Guide To Publication For Beginning Investigators

Writing It Up: A Step-by-Step Guide To Publication For Beginning Investigators

Uploaded by

Sreya MolakalapalliOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Writing It Up: A Step-by-Step Guide To Publication For Beginning Investigators

Writing It Up: A Step-by-Step Guide To Publication For Beginning Investigators

Uploaded by

Sreya MolakalapalliCopyright:

Available Formats

Kliewer S p e c i a l A r t i c l e • Pe r s p e c t i v e

Guide to Publication

Writing It Up: A Step-by-Step

Guide to Publication for

Beginning Investigators

Mark A. Kliewer1 The secret of getting ahead is getting started.

Attributed to Mark Twain (source unknown)

Kliewer MA

OBJECTIVE. Writing scientific manuscripts can be unnecessarily daunting, if not para-

lyzing. This paralysis is usually the result of one of two reasons: either researchers do not know

how to start, or they do not know what to put where. However, most radiology manuscripts fol-

low a definable blueprint. In this article, I attempt to lay out the paragraph-by-paragraph de-

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.185:591-596.

velopment of a typical radiology paper.

CONCLUSION. If authors can accomplish the writing of the 18 paragraphs of text de-

scribed in this article, they will produce a manuscript that is properly organized, correct in its

essentials, and ready for the finishing hand of a seasoned writer and mentor.

oung investigators often finish Arranging the Pencils:

Y the data collection and analysis

phases of their projects flush

with the enthusiasm of finally

Preliminary Steps

Decide to Write the Paper

Make a conscious commitment to start and

arriving at an answer, only to find that en- complete the paper. Nothing succeeds like per-

thusiasm dwindle as they make their first sistence and resolve. If you are junior faculty,

attempts to write the manuscript. Indeed, writing papers is fundamental to your profes-

the number of abstracts presented at na- sion and crucial to your promotion.

tional meetings far exceeds the number of

manuscripts that ultimately are published in Confer with a Mentor

the medical literature [1]. Such failure to Before you begin writing, make sure you are

bring good work to publication stems in launching in an appropriate direction [2]. You

part from the confusion and perplexity that and your mentor should come to agreement on

besets inexperienced writers as they at- the hypothesis, the data analysis, and the basic

tempt to begin the process of manuscript interpretations of your study. Your mentor

preparation. should also be able to make a reasonable ap-

Writing a research paper, however, is praisal of the study and recommend a suitable

largely formulaic. Guidelines for structure target journal. Identifying a target journal early

and organization can be followed to make in the process allows you to format the paper in

the process much more straightforward. Al- accordance with the particular guidelines of

though there have been several fine discus- that journal as you write.

sions of the construction of a scientific

Received November 30, 2004; accepted after revision

February 1, 2005. manuscript [2–4], I believe these resources Create a Timetable

tend not to be as prescriptive and directive as It is commonplace that large jobs should

1Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin, E3/311 needed for a true novice. The intents of this be divided into smaller steps with provi-

CSC, 600 Highland Ave., Madison, WI 53792-3252. Address article, then, are to provide a concrete frame- sional completion dates. Some psycholo-

correspondence to M. A. Kliewer. work, a template of sorts, that can be fol- gists recommend conditioned response strat-

AJR 2005; 185:591–596

lowed to achieve a nearly complete paper, egies (defined workplace, timers) to help

and to provide the young writer with tech- bring concerted effort to the defined subtask

0361–803X/05/1853–591

niques that will facilitate a quick entry into and to keep you from the temptation (and

© American Roentgen Ray Society the process of manuscript preparation. disillusionment) of viewing the project as

AJR:185, September 2005 591

Kliewer

one monumental and arduous whole. Here is Outline these papers in the margins, identify- corresponding to the four sections of the manu-

one timetable: ing the topic of each paragraph. Make notes on script. Pick up the introduction pile and spread

• Session 1: Make notes on the literature, the first page (face sheet) under these head- these papers out before you. Then grab your pen-

outline template papers, set provisional ings: the main point, the population studied, cil, keyboard, or Dictaphone, and start. If possi-

date for completion. paragraphs or statements of particular interest ble, the first draft should be conceived in one sit-

• Session 2: Devise an outline and title for (highlight these), and the section of your paper ting, relentlessly moving from section to section.

your paper. where this paper might be used. As you para-

• Session 3: Create a rough first draft. phrase, be careful about plagiarism. If you Blueprint for a Radiology

• Sessions 4 and 5: Write revisions one and two. make use of a particularly felicitous phrase or Research Paper

• Session 6: Write third revision, prepare ta- statement, make sure it is appropriately attrib- A research article has five sections: the ab-

bles and graphs, then give to coauthors. uted and set off with quotation marks. stract, introduction, methods, results, and dis-

• Session 7: Incorporate suggestions from Read all other articles quickly. Keep the cussion (Appendix 1). Although so ordered in

coauthors into the text. pages turning. Read for concepts. Highlight the manuscript, the writing of these sections is

• Session 8: Prepare all figures and abstract. sparingly. Direct your attention to the first and often in an alternative sequence, such as mate-

• Session 9: Proof all changes, check all last paragraphs of the introduction, first sen- rials and methods, results, introduction, dis-

numbers and units, and review the final tences of methods and results, first and last cussion, and abstract. The reason for this is that

product with mentor. paragraphs of the discussion. Make notes on the process of writing is in fact the process of

• Session 10: Read one last time and send out. the face sheets (as above). thinking through the paper. Often, the central

message of the paper is discovered only after

Begin with a Thorough Literature Search Circumventing the Critical Mind the results are analyzed and written out.

Strongly consider a formal search by the Sketch an Outline As an organizing principle, you should

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.185:591-596.

reference librarians because they tend to do Sort the papers on the basis of the section(s) consider the gap of white space in a manuscript

a better job of it. Request all articles with di- of your paper in which you think they might be between the methods section and results sec-

rect relevance to your topic, but be prag- most useful. Use the papers as you would file tion as the space in which the experiment was

matic: you can waste a lot of time reading ar- cards, shuffling and reshuffling them as they performed. Everything before this gap could

ticles that are off the mark. Literature become relevant to the writing of different sec- be written before a single subject was enrolled.

searches should be at least 2 months current tions. Devise a preliminary title and then a Everything after this space can only be written

at the time of the paper submission. sketchy outline containing only main head- after the analysis of the data has been com-

ings, guided by the outline you discerned in the pleted. It is often helpful to write the introduc-

Sort Gathered Articles by Relevance template papers and the rules for section devel- tion and the methods sections before beginning

Photocopy the articles and number in order of opment given in the text that follows. In the any work on the study. This will tend to focus

greatest relevance. This will be your preliminary outline, do not be too detailed. Do not write the investigation on a single purpose.

reference list and can be used for callouts (refer- sentences, but rather jot notes and phrases for The following is a structured approach to

ence numbers at end of sentences) as you work the paragraphs of each section. writing the manuscript.

through the drafts. Do not worry that your final

reference list will use different numbering: re- Wing the First Draft Preliminary Title

ordering can be easily done by shuffling and re- The first draft is the largest hurdle because The title should include the imaging tech-

numbering the papers for the final reference list. writers often start with standards that are too ex- nique, the disease process, and an allusion to

The photocopied papers will be your file cards. acting and strive for eloquence too early in the the patient population. The title should be

To be sure, many younger authors will writing process. The goal is to get something on short. Often, the linking of two important

doubtless prefer software reference programs paper as quickly as possible. I prefer to dictate a phrases with a colon satisfies the need for brev-

(such as EndNote) to the paper methods just first draft because I can talk faster than I can type, ity and provides a sense of urgency. The title

described. These programs, I understand, have because I have an excellent secretary, and be- will almost surely change in the second draft,

particular advantages for large projects with cause it more effectively creates for me the illu- but writing this title first allows you to write

numerous references (review articles, chap- sion that I am producing persuasive, well-formed the first sentence of your introduction.

ters) and for writers who type their own drafts. sentences. Such self-deception is important and

necessary because it circumvents the overly crit- Introduction

Read the Articles with Varying ical, easily discouraged editorial mind [5]. The purpose of the introduction is to provide

Degrees of Thoroughness If you do not have a secretary who will tran- a rationale for the study. You must provide the

Identify two or three of the most relevant ar- scribe your dictation, then I suggest you write motivation and context for the current investi-

ticles and read these completely for content the first draft as freely and extemporaneously gation. The first sentence of the first para-

and topic development. Use these articles as as you can. Whether dictated or written, the graph should pick up some or most of the

templates or guides to the development of your end result, more likely than not, will be a draft words from the title. You need to articulate the

own paper. Think about it: these authors are that is rough, disorganized, and disappoint- issue your paper addresses within the first

published where you want to be published. Pay ing…and an entirely satisfactory start. three sentences to satisfy the expectations of

attention to what parameters and variables Put your sketchy outline in the middle of your your readers and maintain their attention. For

were included in the study. You should have a desk. Find the references you marked for each the opening sentence of the introduction, be

similar set of parameters in your own study. particular section and stack them in four piles sure to avoid sweeping generalizations (e.g.,

592 AJR:185, September 2005

Guide to Publication

Sonography is a proven means of assessing re- This first attempt should be regarded as a The second subheading should be proce-

nal transplants.). Such statements are usually preliminary introduction, and it may need to be dures. In this segment, you should detail ex-

vacuous and impede rather than advance your modified as your interpretation of your data actly what you did in the order in which you

purposes, and worse, waste the opportunity to matures. You may find that the argument you did it. The experiment should be described in

make your point in one of the most important make for your study can be recast for greater steps, so that readers can reproduce exactly

stress positions of the entire manuscript. Once import and immediacy as you discover the what you did if they so choose. Report the

the issue is established, the intellectual claim more compelling aspects of your results and technical parameters you found in your tem-

of the manuscript—its point—should be made interpretations. plate papers. For the equipment used, provide

explicit in the concluding sentence. In summary, the basic structure of the intro- manufacturer’s name and location (although

The second paragraph of the introduction duction is some journals will edit this out as advertising).

should provide a context and motivation for The next subheading is terms and mea-

the current investigation. Typically, there are statement of the issue → sures. In this segment, operational definitions

two reasons to write a paper: the study or ex- why your paper is needed → and criteria should be explicitly stated. If you

periment is the logical next step in a line of in- explicit purpose or hypothesis. have devised a ranking system, then the criteria

vestigation, or prior studies have been some- for each category should be stated explicitly.

how deficient in some way that the current Materials and Methods Do not assume everyone knows what you

study addresses. You should decide which ra- If lengthy, the materials and methods sec- mean by a certain diagnosis or level of sever-

tionale best justifies your study. If it is the first tion should be organized under subheadings. ity. You may think everyone agrees on what

reason, then the literature review should focus The first subheading should refer to subjects; defines an abdominal aortic aneurysm, but

on the most important two to four articles (you the second subheading to procedures; the third they don’t. Think criteria, criteria, criteria.

can reference many more if you like), and subheading to definitions and criteria; the In the next paragraph, the collection and

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.185:591-596.

show how this line of investigation has led to fourth to data collection; and the final subhead- validation of the data should be described with

your study. If the reason is the inadequacy of ing should refer to statistical tests. These sub- particular attention as to how the data quality is

previous studies, then the two to four most im- headings should be considered a kind of scaf- ensured, usually with blinding or intra- and in-

portant studies should be cited and their defi- folding that can be modified and collapsed as terobserver variability measures. Here too you

ciencies explicitly stated. You will try to jus- needed to suit the investigation being reported should establish what constitutes truth in your

tify your contentions by means of examples, and the requirements of the target journal. study (i.e., your gold standard). If proof against

proofs, or reasons, or by providing a narrative Under the subjects subheading, you should a diagnosis is presumed by a lack of symptoms

unfolding of the details or intricacies of the is- indicate in the first sentence the overall de- or manifestations, then it must be clear how

sue. As a rule, avoid referring to papers using sign of the study. The choices are case report, long the subjects were observed.

author names (e.g., Anderson, Lee, and Wilson case series, case-control study, cohort study, In the next paragraph, the statistical tests

report in their 1967 study that…). Such strings and clinical trial. You should also indicate should be discussed in the order in which they

of proper names tend to slow the pace of the whether the collection of data was retrospec- were applied to the data. If there were several

writing and become altogether too cumber- tive or prospective. questions asked of the data, the statistical

some. Rather, state the point you want to make Next, indicate how the study group was as- tests should be described in the same order as

about the study and reference it with a number sembled. The criteria for inclusion or exclu- the experiment was developed. Typically,

at the end of the sentence. sion should be explicitly stated. If there is a you will start with descriptive statistics to de-

The third paragraph of the introduction control group, the assembly of the control scribe the study subject population, and then

should open with the explicit statement of the group must be discussed. Were the case and proceed to specific statistical tests of associa-

overarching reason your study is needed, control groups chosen randomly; if not, were tion to describe the effects of the experiment

drawing from the preceding paragraph. The they representative of a certain population? or a comparison between populations. In

last sentence of this paragraph should begin, Often, the composition of the study group is these comparisons, use multiple comparison

“The purpose of this study was to…” Readers characterized by a listing of the clinical indica- techniques. This means use a global test of

have a very strong and fixed expectation that tions that brought the patients to imaging. Be significance and then make pairwise compar-

the purpose of the study will be found in last sure to indicate how many patients were en- isons. This approach first shows that there is

sentence of the last paragraph of the introduc- rolled for each indication. Statements about in- some difference between populations in the

tion. Do not worry about being unoriginal: this formed consent and institutional review board global test and then teases out the specific dif-

is not creative writing (at least in the common approval belong here. ferences between populations in the pairwise

sense), but rather formulaic, patterned writing. The demographics of the patient population comparisons.

A busy reviewer does not want to search for should be written in the methods section if this Make sure that the independent variables

certain elements of the paper: these should be is a retrospective study. If this is a prospective (factors or predictor variables) are clearly iden-

where he or she expects to find them, like tools study, then the inclusion and exclusion criteria tified, and that the dependent variables (out-

in their rightful place. represent the rules by which the study groups comes) are also identified. A statement about

Remember that the lack of a clearly stated are chosen. Your rules create the bins into sample size and power calculations may be

research question is the most common reason which subjects will be collected, and the ulti- needed, especially if the study reports negative

for rejection of manuscripts by journal edi- mate result of that collection will be reported in results. The last sentence of this paragraph

tors. There must be an identifiable hypothesis. the results section. That is, the demographics should include a statement of what p value rep-

There must be a question being asked. go in the results section for prospective studies. resents an acceptable level of statistical signif-

AJR:185, September 2005 593

Kliewer

icance. Traditionally, this value is 0.05, but if up or make sense, the paper will almost surely procedural results and sorted outcomes →

a different level is chosen (usually a more con- be harshly reviewed. measures of data validity →

servative one), then that should be stated and Depending on the study design, at least one results of statistical analyses.

the reason given. paragraph should be devoted to how well the

The methods section can often be written at predictor or independent variables led to the Discussion and Conclusion

the outset of the study, even as the study is be- outcome or dependent variable. If the experi- The first paragraph of this section should

ing planned. Presumably, all these factors have ment is such that the effects of several factors summarize the results that address your study

been decided on before the experiment occurs, are being measured against an outcome, then objectives. Do not start with a literature re-

and it is helpful to write this section, and in- the effect sizes of all the variables should be view or a protracted discussion of the patho-

deed the introduction section as well, before explicitly stated so that the reader will know logic entity under discussion. Such informa-

the experiment occurs. whether these are clinically significant (in ad- tion should never be included unless the

In summary, the basic structure of the meth- dition to being statistically significant). Sta- particulars have direct bearing on your con-

ods section is tistical significance is a statement of the clusions, and even then, should never be in-

strength of the evidence, not necessarily of troduced before the third paragraph of this

subjects → procedures and techniques → clinical importance. section (see following text). Talk specifically

definitions and criteria → The primary purpose of tables, graphs, and about your principal findings, which will be

data collection and validation → figures is to present data in a way that is easily the findings that address the questions posed

statistical tests. and quickly grasped. To this end, data should in the introduction. References to data from

be summarized, condensed, and displayed as the results section should be limited to the

Results transparently and memorably as possible. The most important numbers. Do not reiterate all

The development of the results section most common and significant problem with ta- the data from the results section, and never in-

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.185:591-596.

should parallel that of the methods section. If bles is that authors will attempt to present too troduce new data here.

subheadings are used in the methods section, much information [6] and create an overly The second paragraph advances the thesis

then the same subheadings should be provided complex and undistilled smattering of num- from findings to interpretations. The principal

in the same order in the results section. Again, bers that will almost surely be ignored by all findings of the first paragraph become the sub-

you may choose to eliminate these subhead- but the most diligent and critical of readers. Ta- strate on which the principal conclusions of the

ings, but the organization of the methods and bles are an especially effective way to summa- second paragraph are drawn. Do not extrapo-

results sections must coincide. rize demographic information and descriptive late beyond the evidence. Draw reasonable

The first paragraph of the results section statistics. If two nominal variables (names or conclusions from this current investigation

should describe the study population if this is a categories) are being compared, use a contin- only. Stay on topic: do not stray into discursive

prospective study. Here, general comparisons gency table. asides. If you have several major points to

of the baseline characteristics of the study pop- Regarding graphs, if you want to display the make, you may need to write more than one pa-

ulations are needed, and the descriptive statis- amounts or the percentages of a variable in dif- per. Too many conclusions dilute the impact of

tics (means, medians, SDs, range) should be ferent categories, use either a bar chart or a his- any one: it is always better to produce two, or

reported in tables or graphs. The population togram. If two numeric measures of the same even three, papers that are focused and tight

should be described in terms of number, sex, subjects are being compared, then choose scat- rather than create one comprehensive but dif-

age, symptoms, or presentations. The baseline terplots. If measurements consist of one or fuse magnum opus.

comparison should allow the readers to decide more nominal variables (categories) and one The third paragraph should state whether

whether the case and control groups are similar numeric variable, consider using box plots to your interpretations are in concert with those

or not, and more important, whether these illustrate the distribution of the numeric obser- of other researchers. Your interpretations will

groups resemble the patient populations in vations for each category [6]. Line charts can represent either consistency with current think-

their own practice. be used to display changes of a quantitative ing or a departure from current thinking. De-

The second paragraph should describe the variable over time. Pie charts and pictographs cide which it is and suggest reasons for this

results of the experiments or the sorting of pa- are best used to display resource information, consistency or inconsistency (such as different

tients into the created categories (what per- such as the relative portion or percentage of a patient populations, different procedures, or

centage of subjects or experiments leads to population that falls into various categories. different level of data quality). This paragraph

which results; often best illustrated with ta- Figures and images should illustrate the should place your conclusions in the context of

bles and graphs). The results of the various major imaging findings. The liberal use of ar- conclusions from prior studies. References to

procedures should be reported in the same or- rows on figures is encouraged. If the details of the literature in this paragraph should not re-

der as described in the methods section. Keep the data are reported in tables, graphs, or im- hash the second paragraph of the introduction

editorializing out of results as much as possi- ages, then the text should summarize the major (which provided a rationale for the study), but

ble. This section is simply for the reporting of points of the figure but not exhaustively reca- rather should develop lines or axes of compar-

facts and numbers, not for the interpretation pitulate the detail. ison between your study and earlier studies. Do

of these findings. In summary, the basic structure of the re- not exhaustively describe all the aspects of all

In your reporting, make sure you check your sults section is studies, but focus on the conclusions of those

units (e.g., cm vs mm). Make sure the numbers studies that relate to your own conclusions.

add up (all patients, lesions, and outcomes must descriptive statistics and baseline Again, avoid strings of author names when re-

be accounted for). When numbers do not add population comparisons → ferring to other studies.

594 AJR:185, September 2005

Guide to Publication

In the fourth paragraph, clearly articulate spondence between the purpose of the study research to ensure that those on the paper de-

the clinical implications of your findings. and the conclusions from the study. serve to be there.

What are the important clinical lessons to be As a rule, the principal writer should be the

drawn from your work? Are there diagnostic The Good-Enough Paper first author and the mentor the last. Other co-

pitfalls to avoid? Are there key imaging find- Revising the work is a task of systematic authors are listed after the first author in order

ings that can aid diagnosis? New factors to culling. If the first draft is the sowing of seeds, of their level of contribution. Again, much un-

consider? Try to make your new insights clin- then revision is the work of weeding and prun- pleasantness can be avoided if these issues are

ically relevant. If your work is more basic sci- ing. In editing, you must be willing to delete discussed early in a group meeting.

ence in orientation, explain how your findings your most cherished flights of rhetorical flour- In the final drafts, you will find the paper

illuminate larger issues of pathophysiology. ish in the service of a coherent thesis. This is taking final form. This is the time to be fastid-

Can your findings be fit into what is known detail work, best done piece by piece. For the ious, to strive for the persuasive expression of

about the physiology, pathology, chemistry, or revision, take a segment of text and work it your ideas through well-manicured sentences.

mechanics of the disease process under study? over, then move to the next and the next sys- Before you send the paper out, force yourself

Offer a theory as to why matters just might be tematically. Try not to linger: This is not your to read it carefully one last time, making sure

as you contend. last chance at the text. Take that rough first that the numbers all add up, that there are no

The fifth paragraph should indicate the lim- draft and write all over the paper copy. Reorder gross misspellings or grammatical errors, and

itations of your study. Be forthright, but do not things, restructure things, draw arrows, cross that the references are in the order of their call-

flagellate yourself or your investigation. You out. Make the changes, then sleep on it and outs in the text. If your reviewers are faced

want to be thoughtful and self-critical without look at it again the next day. with many errors, they are likely to give the

undermining the validity of your study. Such By the third or fourth draft, you should have project little credence.

commentary will tend to preempt criticism and a paper that is about 50–75% good. Stop here. Submit your paper for review when you

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.185:591-596.

thereby diffuse it, but more important, it pro- Pass off the paper to your coauthors and let think it is good enough. Do not strive for per-

vides your readers with an understanding of the them earn their place on the paper. You may fection or you will never send the paper out.

practical limits of your data and interpretations. also want to enlist a dispassionate third party

The last paragraph should be a summary (not a coauthor), who will have greater critical Submission: Abject and Otherwise

paragraph. First, restate your principal findings distance. Tell them you want their comments The selection of an appropriate journal turns

and conclusions. Second, emphasize the clini- in 1 week. Oftentimes, your coauthors will of- on whether the study is suitable for a general ra-

cal or basic science implications of your find- fer interpretations that you did not think of, or diology audience or a subspecialty audience.

ings. The last sentence should describe the log- make suggestions that lead to a complete re- Do not overvalue your paper (which can lead to

ical next step, if one is needed. If there is no structuring of your argument. Once you get the demoralizing rejections), but do not undervalue

logical next step, do not recommend that peo- paper back from your coauthors, critically de- your paper either. If you think it might make it

ple do further studies if you think this line of cide which comments you choose to incorpo- into one of the major radiology journals, send

investigation is going nowhere. rate into the next draft of your paper and which the paper with the foreknowledge that even sea-

In summary, the basic structure of the dis- you choose to ignore. soned investigators often have trouble publish-

cussion section is This leads to the thorny issue of coauthor- ing in these journals. If you get a rejection, pick

ship and order of authors. At one level, the is- yourself (and your paper) up, dust yourself off,

your chief results → sue is relatively simple: authorship estab- reformat the paper for another journal, and use

your interpretation of your results → lishes accountability, responsibility, and the critiques of the reviewers to improve your

your interpretation in the context credit [7, 8]. Unfortunately, the issue of au- paper. Look critically at your study for ways

of the literature → thorship can become awkwardly politicized. that the presentation can be more transparent

clinical or pathophysiologic implications → A substantial proportion of manuscripts con- and your purposes clearer. Remember that if

limitations → summary. tain honorary and ghost authors [7, 9, 10]. you make reviewers work too hard to under-

The most egregious abuses come from senior stand your paper, they will not like it.

The Abstract staff and division chiefs who insist that their If your paper is accepted pending major re-

The abstract is usually written after all the name be included, if only because the project vision, try to accommodate all or most of the

basic components of the paper have been writ- was conducted within their division. No edi- requests as best you can. You want at least to

ten. The abstract is a distillation of the four ma- tor would endorse such honorary authorship, appear to comply with the spirit of the criti-

jor segments: introduction, methods, results, but it is a strong junior faculty member indeed cism. A positive and conciliatory attitude in

and discussion. The abstract is organized along who can stand up to that kind of pressure. The your response will likely engender a positive

these subheadings. Economy is paramount. best advice perhaps is to clearly define ex- and conciliatory attitude in return; a pugna-

The purpose of the study should be encapsu- actly who is a member of the research group cious one will not. Quibbling with reviewers or

lated in one or two sentences. The methods at the outset of a project and have everyone in the editor never endears you to them and rarely

paragraph should include only an outline of the that group agree to their roles and responsibil- expedites progress to publication.

procedures and variables. The results should ities in a collective meeting. Coauthorship If your paper is not accepted, do not give up.

report only the principal findings of the study. then becomes a condition of the individual’s Of all papers submitted to the American Jour-

The conclusion should be limited to one or two fulfillment of this public contract. As a sec- nal of Roentgenology, 82% are eventually pub-

sentences and should directly reflect the words ondary resort, junior authors may also seek lished there or in some other journal [11]. If

of the purpose. There should be direct corre- the support and oversight of the vice chair for you do not know how to improve your paper,

AJR:185, September 2005 595

Kliewer

seek help from others who may not be in your clusion as a published manuscript, and no one 4. Huth EJ. Writing and publishing in medicine, 3rd

subspecialty but know how to market their deserves that satisfaction more than the one ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1999

wares. These are usually the people in the de- who did most of the work. 5. Lamott A. Bird by bird: some instructions on writ-

partment who have written and published ing and life. New York, NY: Doubleday, 1994

many papers. Other good sources of advice on Acknowledgments 6. Dawson-Saunders B, Trapp RG. Exploring and pre-

scientific writing are listed in Appendix 2. I thank Carrie Poole for general assistance senting data. In: Dawson-Saunders B, Trapp RG,

in manuscript preparation and Eileen Ahearn eds. Basic & clinical biostatistics, 2nd ed. Norwalk,

Last Words of Encouragement for her helpful discussion and manuscript CT: Appleton & Lange, 1994:20–40

First attempts at writing up an investiga- review. I also thank Jim Bowie, who mentored 7. Mowatt G, Shirran L, Grimshaw JM, et al. Preva-

tion are challenging. The most important and taught me. lence of honorary and ghost authorship in Cochrane

thing is to start. The next most important reviews. JAMA 2002; 287:2769–2771

thing is to get the elements of the paper in 8. Friedman PJ, Partain CL, Mettle FA Jr. Standards

some coherent order (Appendix 1). If these References for authorship and publication in academic radiol-

two objectives are fulfilled, you can usually 1. Weber EJ, Callaham ML, Wears RL, Barton C, ogy. AJR 1993; 161:899–900

count on an experienced writer or a mentor to Young G. Unpublished research from a medical 9. Chew FS. Coauthorship in radiology journals. AJR

help you guide the document to an acceptable specialty meeting: why investigators fail to publish. 1988; 150:23–28

state. What that mentor does not want is to JAMA 1998; 28:257–259 10. Flanagin A, Carey LA, Fontanarosa PB, et al. Prev-

have to take a completely disorganized docu- 2. Berk RN. Preparation of manuscripts for radiology alence of articles with honorary authors and ghost

ment and rewrite the entire thing. And, of journals: advice to first-time authors. AJR 1992; authors in peer-reviewed medical journals. JAMA

course, this is not what the junior researcher 158:203–208 1998; 280:222–224

wants either. Considerable satisfaction will 3. Siegelman SS. Advice to authors. Radiology 1988; 11. Chew FS. Fate of manuscripts rejected for publica-

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.185:591-596.

be gained in taking a project nearly to its con- 166:278–280 tion in the AJR. AJR 1991; 156:627–632

APPENDIX 1: Paragraph by Paragraph: Content and Order of the 18 Basic Paragraphs in the Typical Radiology Manuscript

Introduction

1. Statement of the issue

2. Why your paper is needed

3. Explicit purpose and hypothesis

Materials and Methods

4. Subjects

5. Procedures and techniques

6. Definitions and criteria

7. Data collection and validation

8. Statistical tests

Results

9. Descriptive statistics and baseline population comparisons

10. Procedural results and sorted outcomes

11. Measures of data validity

12. Results of statistical analyses (same order as in Materials and Methods;

often > 1 paragraph)

Discussion

13. Your chief results

14. Your interpretation of your results

15. Your interpretation in the context of the literature

16. Clinical or pathophysiologic implications

17. Limitations

18. Summary and future directions

APPENDIX 2: Good Sources of Advice on Scientific Writing

1. Gopen GD, Swan JA. The science of scientific writing. American Scientist 1990; 78:550–558

2. Gopen GD. The sense of structure: writing from the reader’s perspective. New York, NY: Pearson Longman, 2004

3. Booth WC, Colomb GG, Williams JM. The craft of research, 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2003

4. Eng J, Siegelman SS. Improving radiology research methods: what is being asked and who is being studied? Radiology 1997; 205:651–655

5. Griscom NT. Your research: how to get it on paper and in print. Pediatr Radiol 1999; 29:81–86

6. Laniado M. How to present research data consistently in a scientific paper. Eur Radiol 1996; 6:S16–S18

596 AJR:185, September 2005

You might also like

- ISO 22000 Audit Checklist ReportDocument37 pagesISO 22000 Audit Checklist ReportFlavones Extract100% (6)

- In A Dry SeasonDocument1 pageIn A Dry SeasonNico Mark Banting100% (6)

- Swales & Feak - Chapter 1Document15 pagesSwales & Feak - Chapter 1Sara Santos100% (1)

- The Importance of HRM For OrganizationDocument10 pagesThe Importance of HRM For OrganizationSmita Mishra100% (1)

- Turing Machine VS Pushdown AutomataDocument23 pagesTuring Machine VS Pushdown AutomataHimanshu100% (2)

- Saep 11Document35 pagesSaep 11Anonymous 4IpmN7OnNo ratings yet

- 10 Tips On How We Write PapersDocument3 pages10 Tips On How We Write PapersJunbo LuNo ratings yet

- 01 Writing A ThesisDocument8 pages01 Writing A ThesisモニカNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Popular ArticleDocument2 pagesHow To Write A Popular ArticleWiwid N Addhiani100% (1)

- ZERAH LUNA - Simmering and Swooping Creative Steps Before WritingDocument2 pagesZERAH LUNA - Simmering and Swooping Creative Steps Before WritingZerah LunaNo ratings yet

- Ess - Onward - c3 w16 - 2023Document52 pagesEss - Onward - c3 w16 - 2023imanigi40No ratings yet

- Tips: Working On Final Manuscript: Prepared byDocument7 pagesTips: Working On Final Manuscript: Prepared byreynaldo corpuzNo ratings yet

- One World Essay: Report Writing Guide!Document4 pagesOne World Essay: Report Writing Guide!jay prakashNo ratings yet

- Communication SkillDocument1 pageCommunication SkillFAISALNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Research Paper: Some BasicsDocument11 pagesHow To Write A Research Paper: Some BasicsJoselo HRNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Scientific Paper: Begin With A BlueprintDocument4 pagesHow To Write A Scientific Paper: Begin With A BlueprintWinalda EkaNo ratings yet

- Critiquing of A Research PaperDocument11 pagesCritiquing of A Research PaperAnnRubyAlcaideBlandoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 21Document3 pagesLesson 21redaiza nica odchigueNo ratings yet

- Structure of A Research Article A Practical Guide For A Successful JourneyDocument2 pagesStructure of A Research Article A Practical Guide For A Successful JourneySaúl HuertaNo ratings yet

- New Community Meeting Sheet For '09Document2 pagesNew Community Meeting Sheet For '09Ward6acdNo ratings yet

- Efficient Reading1Document2 pagesEfficient Reading1Teguh RijanandiNo ratings yet

- How To Write Your First Paper: Ethics/EducationDocument2 pagesHow To Write Your First Paper: Ethics/Educationtakiq laseNo ratings yet

- New Keystone LD U2 - Student's EditionDocument72 pagesNew Keystone LD U2 - Student's EditionDr.Rashed AlawamlehNo ratings yet

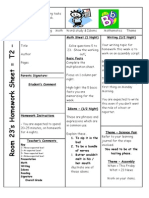

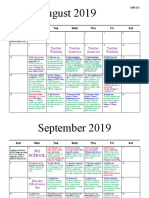

- Homework - Term 2 Week 7Document1 pageHomework - Term 2 Week 7TerryNo ratings yet

- Long Range Plan Writers WorkshopDocument7 pagesLong Range Plan Writers Workshopapi-336646580No ratings yet

- Preparing A Manuscript For Publication - A User-Friendly GuideDocument4 pagesPreparing A Manuscript For Publication - A User-Friendly GuideUche OnyeaborNo ratings yet

- Writting Archaeology. Brian Fagan. Cap11-1 Sesión 10Document16 pagesWritting Archaeology. Brian Fagan. Cap11-1 Sesión 10ColinOscarNo ratings yet

- Week of 1Document1 pageWeek of 1api-368156036No ratings yet

- Writing ProcessDocument13 pagesWriting ProcessDavor Tarade100% (1)

- PAALALA: Huwag Susulatan Ang Modyul. Pakibalik/Pakilagay Sa Portfolio Ang Mga Sinagutang PapelDocument2 pagesPAALALA: Huwag Susulatan Ang Modyul. Pakibalik/Pakilagay Sa Portfolio Ang Mga Sinagutang PapelSirr ArjayNo ratings yet

- Week of 1Document1 pageWeek of 1api-368156036No ratings yet

- Teaching Writing: We Teach EnglishDocument34 pagesTeaching Writing: We Teach EnglishЮлиана КриминскаяNo ratings yet

- Academic-Writing-1-Writing ProcessDocument6 pagesAcademic-Writing-1-Writing ProcessMayera TirmeziNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document6 pagesChapter 7Lyn Fernan0% (1)

- Writing Process - Bca.Document35 pagesWriting Process - Bca.irma coronadoNo ratings yet

- SIGILDocument10 pagesSIGILanjas widiNo ratings yet

- Six Month Book Publishing PlanDocument9 pagesSix Month Book Publishing PlanjenNo ratings yet

- 0lesson Plan VIIDocument2 pages0lesson Plan VIIHrib .AncaNo ratings yet

- 00 Unit-1-Slides - HandoutsDocument10 pages00 Unit-1-Slides - HandoutsShy OnNo ratings yet

- RM Unit1 Part2Document34 pagesRM Unit1 Part2udayNo ratings yet

- EAPP ReviewerDocument3 pagesEAPP ReviewerVeronica Hycinth SabidoNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Business Report Writing - Kuiper, Shirley - 2009 - Australia Mason, OH - South-Western Cengage Learning - 9780324587425 - Anna's ArchiveDocument564 pagesContemporary Business Report Writing - Kuiper, Shirley - 2009 - Australia Mason, OH - South-Western Cengage Learning - 9780324587425 - Anna's ArchiveBerkeley PhanNo ratings yet

- ExpositoryWritingUnit 1Document41 pagesExpositoryWritingUnit 1cheernteachNo ratings yet

- A Level Spanish Writing SkillsDocument11 pagesA Level Spanish Writing Skillsgzmiglesias50% (2)

- NWSTP Newsletter 3Document6 pagesNWSTP Newsletter 3api-432531382No ratings yet

- Wordsmith 5e Ch01Document12 pagesWordsmith 5e Ch01VIPA ACADEMICNo ratings yet

- Stage 1: Desired Results: Focused Learning Outcome(s) ProvocationsDocument3 pagesStage 1: Desired Results: Focused Learning Outcome(s) Provocationsapi-385154491No ratings yet

- Write It! Paragraph To Essay 3 TB Answer KeyDocument45 pagesWrite It! Paragraph To Essay 3 TB Answer Keydannyhwang1991No ratings yet

- June Remedial PlanDocument3 pagesJune Remedial PlanScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- What Is An EssayDocument9 pagesWhat Is An EssayAndi Syaiful RifliNo ratings yet

- Sample Chapter ch03 PDFDocument38 pagesSample Chapter ch03 PDFannisa100% (1)

- 2019-20 Cmu 111Document5 pages2019-20 Cmu 111api-216774555No ratings yet

- Narrative Essays: Lesson 4Document6 pagesNarrative Essays: Lesson 4Avtarjit KaurNo ratings yet

- Trainer Competition - Session Plan ExampleDocument3 pagesTrainer Competition - Session Plan ExampleMenvie PetremetreNo ratings yet

- Based Im HomoDocument25 pagesBased Im Homosaaransh besoyaNo ratings yet

- 2018 Curriculum Guide CompleteDocument139 pages2018 Curriculum Guide Completepenelopegerhard100% (4)

- Basic Introduction To Academic WritingDocument15 pagesBasic Introduction To Academic WritingRifqyRujaniNo ratings yet

- Lopez ProposalDocument1 pageLopez ProposalMariana LopezNo ratings yet

- How To: Write & Publish A ManuscriptDocument108 pagesHow To: Write & Publish A Manuscriptfirman DoctorNo ratings yet

- Research ProjectDocument4 pagesResearch Projectapi-240724606No ratings yet

- LEsson 3Document50 pagesLEsson 3Jomarie PauleNo ratings yet

- A Short Guide To Research Methods For M.Sc. and Ph.D. DegreesDocument22 pagesA Short Guide To Research Methods For M.Sc. and Ph.D. DegreesJohn Ryan C. DizonNo ratings yet

- Written Work #2 - Synthesis MatrixDocument2 pagesWritten Work #2 - Synthesis MatrixAngela MadridNo ratings yet

- Reading Techniques IIEDocument8 pagesReading Techniques IIEphilile654No ratings yet

- Four Square for Writing Assessment - Elementary: A Companion to the Four Square Writing MethodFrom EverandFour Square for Writing Assessment - Elementary: A Companion to the Four Square Writing MethodNo ratings yet

- ITSD Document StandardDocument77 pagesITSD Document StandardhenrykylawNo ratings yet

- Links For Production Planning and ControlDocument4 pagesLinks For Production Planning and ControlmehatajmosiqNo ratings yet

- DHCP Ubuntu 12.04Document6 pagesDHCP Ubuntu 12.04Adiel TriguerosNo ratings yet

- I Do Like CFD Vol1 - 2ed - v00Document299 pagesI Do Like CFD Vol1 - 2ed - v00ipixunaNo ratings yet

- RefacDocument5 pagesRefacknight1729No ratings yet

- Essbase Calc AguideDocument68 pagesEssbase Calc AguideSuman DarsiNo ratings yet

- 9608 November 2015 Question Paper 42 PDFDocument16 pages9608 November 2015 Question Paper 42 PDFCrustNo ratings yet

- Science Project: Green Chemistry: The Future of Sustainable ScienceDocument13 pagesScience Project: Green Chemistry: The Future of Sustainable Sciencethuanv2511No ratings yet

- Learning Theory by BanduraDocument5 pagesLearning Theory by BanduraOnwuka FrancisNo ratings yet

- DAO 29-92 IRR Ra6969 PDFDocument39 pagesDAO 29-92 IRR Ra6969 PDFaeronastyNo ratings yet

- Construction Project Proposal by SlidesgoDocument45 pagesConstruction Project Proposal by Slidesgoanisa nur'alifahNo ratings yet

- P-Diagram - Project Marcel Transmission SystemDocument1 pageP-Diagram - Project Marcel Transmission SystemkumarNo ratings yet

- Summary CH 4 Control Systems TightnessDocument5 pagesSummary CH 4 Control Systems TightnessShafira Alifiana ElmiraNo ratings yet

- A Guide To MPEGDocument48 pagesA Guide To MPEGNguyen Duong100% (1)

- Reading Unit 4Document6 pagesReading Unit 4Ngọc Quỳnh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Strategi Public Relations Dalam Mempertahankan Citra Perusahaan PT Sumber Alfaria Trijaya TBK (Alfamart)Document8 pagesStrategi Public Relations Dalam Mempertahankan Citra Perusahaan PT Sumber Alfaria Trijaya TBK (Alfamart)Lelian Tiara Harika PutriNo ratings yet

- STT Quiz-1Document4 pagesSTT Quiz-1School OnlyNo ratings yet

- Students' Council Involvement in Decision Making and Students' Discipline in Secondary Schools in Tongaren Sub County, KenyaDocument6 pagesStudents' Council Involvement in Decision Making and Students' Discipline in Secondary Schools in Tongaren Sub County, KenyaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- 5) Asymemtric - GRACHDocument34 pages5) Asymemtric - GRACHDunsScotoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3: Building Partnerships: 3.1 Stakeholders For The Watershed Restoration PlanDocument14 pagesChapter 3: Building Partnerships: 3.1 Stakeholders For The Watershed Restoration PlanSweet WaterNo ratings yet

- Facets of The Past The Challenge of The Balkan Neo Eneolithic 2008Document770 pagesFacets of The Past The Challenge of The Balkan Neo Eneolithic 2008Gaspar LoredanaNo ratings yet

- Devex 2018 Introduction To Reservoir SimulationDocument52 pagesDevex 2018 Introduction To Reservoir SimulationKonul AlizadehNo ratings yet

- Mignolo Interview PluriversityDocument38 pagesMignolo Interview PluriversityJamille Pinheiro DiasNo ratings yet

- Digital Libraries: Definitions, Issues, and Challenges: Review ArticleDocument3 pagesDigital Libraries: Definitions, Issues, and Challenges: Review ArticleARIEZ HAZARIL BIN AB.LLAH -No ratings yet

- Chance Aesthetics PDFDocument17 pagesChance Aesthetics PDFEl INo ratings yet