Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Frenkel1976 PDF

Frenkel1976 PDF

Uploaded by

César Manuel Trejo LuceroOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Frenkel1976 PDF

Frenkel1976 PDF

Uploaded by

César Manuel Trejo LuceroCopyright:

Available Formats

A Monetary Approach to the Exchange Rate: Doctrinal Aspects and Empirical Evidence

Author(s): Jacob A. Frenkel

Source: The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, Vol. 78, No. 2, Proceedings of a Conference

on Flexible Exchange Rates and Stabilization Policy (Jun., 1976), pp. 200-224

Published by: Wiley on behalf of The Scandinavian Journal of Economics

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3439924 .

Accessed: 26/11/2014 03:40

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Wiley and The Scandinavian Journal of Economics are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to The Scandinavian Journal of Economics.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A MONETARYAPPROACHTO THE EXCHANGE

ASPECTSANDEMPIRICAL

RATE:DOCTRINAL

EVIDENCE

JacobA. Frenkel*

Tel-Aviv,Israel

Universityof Chicago,Chicago,Illinois,USA and Tel-AvivUniversity,

"What, then, has determinedand will determine the

value of the Franc? First, the quantity, present and

prospective, of the francs in circulation. Second, the

amount of purchasingpower which it suits the public to

hold in that shape."

Keyne8(Introductionto French edition, 1924, xviii).

Abstract

This paper deals with the determinantsof the exchange rate and develops a

monetaryview (or more generally,an asset view) of exchangerate determination.

The firstpart traces some of the doctrinaloriginsof approaches to the analysis

of equilibrium exchange rates. The second part examines some of the empirical

hypotheses of the monetary approach as well as some featuresof the efficiency

of the foreignexchange markets. Special emphasis is given to the role of expecta-

tions in exchange rate determinationand a direct observablemeasureof expecta-

tions is proposed. The directmeasure of expectationsbuilds on the information

that is contained in data from the forwardmarket for foreignexchange. The

empiricalresultsare shown to be consistentwith the hypothesesof the monetary

approach.

Introduction

This paper deals withthe determinants of the exchangerate. The approach

that is takenreflectsthe currentrevivalof a monetaryview,or moregener-

allyan assetview,oftheroleoftheratesofexchange.1Basically,themonetary

approachto the exchangerate may be viewed as a dual relationshipto the

monetaryapproachto the balance of payments.These approachesemphasize

the role of moneyand otherassets in determining the balance of payments

* I am indebted to John Bilson forcomments,suggestionsand efficientresearchassistance.

In revising the paper I have benefitedfromhelpfulassistance fromR. W. Banz and useful

suggestionsby W. H. Branson, K. W. Clements,R. Dornbusch, S. Fischer, R. J. Gordon,

H. G. Johnson,M. Parkin, D. Patinkin and L. G. Telser. Financial support was provided

by a grant fromthe Ford Foundation.

1 This view has been forcefullyemphasized by Dornbusch (1975, 1976, 1976a). See, too,

Frenkel and Rodriguez (1975), Johnson (1975), Kouri (1975) and Mussa (1974, 1976).

For an early incorporationof monetaryconsiderationsin exchange rate determinationsee

Mundell (1968, 1971).

Sand. J. of Economica 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A monetary

approachtotheexchangerate 201

whenthe exchangerateis pegged,and in determining the exchangerate when

it is flexible.

Being a relativepriceoftwo assets (moneys),the equilibriumexchangerate

is attainedwhenthe existingstocksof the two moneysare willinglyheld. It is

reasonable,therefore, that a theoryof the determination of the relativeprice

of two moneyscould be statedconveniently in termsof the supplyof and the

demandforthesemoneys.

The renewedemphasison theroleofthesupplyofand thedemandformoneys

and assets as stocksin contrastwiththe circularflowapproachto thedeter-

minationof the exchangerate (that gained popularitywith the domination

of the Keynesianrevolution),revivesthe basic discussionof the Bullionist

controversy culiminatedin the early 1800's and led to the developmentsof

the "Balance of Trade Theory"and the "InflationTheory"of the determina-

tion of the exchangerate (Ricardo, 1811; Haberler,1936; Viner,1937). Re-

miniscenceof that controversy can be tracedto presenttimesin the various

discussionsand interpretation of the purchasingpower parity doctrine.It

may be arguedthat the long experiencewiththe gold standardand withthe

gold exchangestandardmay have led to the retrogression of the theoryof

flexibleexchangerates (Wicksell,1911,p. 231; Gregory,1922,p. 80).1

The firstpartofthepapertracessomeofthedoctrinaloriginsofapproaches

to exchangerate determination. Its purposeis to providesome perspective

into the evolutionof the theory.2The main emphasisof the paper lies in its

secondpart wherewe examinesomeof the empiricalhypothesesof the mone-

tary approach.In that part we analyze the role of expectations,we describe

a directmeasurethereof, examinetheefficiency oftheforeign exchangemarket

duringthe Germanhyperinflation, and provide some evidence which sup-

portsthe asset view of exchangerate determination.

I. A Doctrinal Perspective to Exchange Rate Determination

I.1. The PurchasingPowerParityDoctrine:

The Natureof Equilibrium

The purchasingpowerparitydoctrine(in its absoluteversion)statesthat the

equilibriumexchangerate equals the ratio of domesticto foreignprices.The

relativeversionof the theoryrelateschangesin the exchangerate to changes

in priceratios.Many of the controversies

aroundthat doctrinerelateto the

1 It is of interestto note that the introductionof the "liquidity preference"schedule which

emphasizes the role of asset markets and characterizes much of the Keynesian revolution

in macroeconomic analysis of the closed economy, did not carry over to the popular

versions of the Keynesian theoriesof the balance of payments. The Keynesian analysis of

the balance of payments emphasizes the circular flow of income, the foreigntrade multi-

plier and, in its popular version, ignores to a large extent the role of money and other

assets. For a notable exception, see Metzler (1968).

2 An analogous doctrinal perspective of the evolution of the monetary approach to the

balance of payments under fixed exchange rate is contained in Frenkel & Johnson (1976)

and Frenkel (1976). For a furtheranalysis see Myhrman (1976).

Scand. J. of Economic8 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

202 J. A. Frenkel

questionof choiceof properpriceindicesto be used in computingthe parity.'

One extremeview arguesthat the properpriceindex shouldpertainto traded

goods only(Angell,1922; Bunting,1939 Heckscher,1930; Pigou, 1930; Viner,

1937), whileaccordingto the otherextremeviewtheproperpriceindexshould

coverthe broadestrangeof commodities(Hawtrey,1919,p. 109; Cassel,1928,

p. 33).2

Those who advocate the use of traded goods index emphasizethe role of

commodityarbitragewhilethose who advocate the broaderpriceindex em-

phasize the role of asset equilibriumas determining the rate of exchange.If

the role of the exchangerate is to clear the moneymarketby equatingthe

purchasingpowerof the variouscurrencies, thenthe relevantmeasureshould

be a consumerpriceindex.3Proponentsofthisviewrejecttheuse ofthewhole-

sale priceindexsinceit givesan excessiveweightto tradedgoods (Ellis, 1936,

pp. 28-9; Haberler,1945,p. 312 and 1961,pp. 49-50).

The two viewsdifferfundamentally in the interpretation

ofthe equilibrium

exchangerate. The commodityarbitrageview goes even furtherin arguing

that no aggregateprice index is relevantand only individual commodity

pricesshouldbe analyzed:

"Foreignexchangerateshave nothingto do withthewholesalecommodity

price

levelas suchbut onlywithindividualprices"(Ohlin,1967,p. 290).

The equilibriumexchangerate reflectsspatial arbitragefromwhichnon-

tradedgoods are excluded:

"Patently,I cannotimportcheapItalianhaircutnorcan Niagra-Falls

honeymoons

be exported"(Samuelson,1964,p. 148).

The assetviewtakesit forgrantedthattheoperationofcommodity arbitrage

equates the pricesoftradedgoods and emphasizesthatifthedoctrineonlyap-

plies to tradedgoods,then:

"the purchasing powerparitydoctrinepresentsbut littleinterest... (it) simply

statesthatpricesin termsofanygivencurrency, ofsamecommodity mustbe the

same everywhere ... Whereasits essenceis thestatement

thatexchangeratesare

the index of the monetaryconditionsin the countriesconcerned"(Bresciani-

Turroni,1934,p. 121).

In fact since the exchangerate linksthe purchasingpowervalues of moneys

in termsofthe broaddefinition ofthe pricelevel,one mayimaginea situation

in whichall tradedgoods possessthe same price,whenexpressedin common

currency, but the exchangerate is in disequilibrium:

I See Viner (1937) and Johnson (1968).

2 It might be of interestto compare these discussions with those concerningthe range of

transactionsand prices that is relevant forthe quantity theoryof money. The latter ranged

fromsuggestionsto include transactions in assets and prices of securities to suggestions

to include only what is definedas national product.

8 On the relevance of the consumer price index as a measure of the purchasing power of

money see Marshall (1923, p. 30) and Keynes (1930, p. 54).

Scand. J. of Economies 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A monetary

approachtotheexchangerate 203

"The equilibrium to whichtheforeign exchangemarkettendsis an equilibrium of

thepricelevel... If thecurrency unitsoftwocountries be considered

in termsof

foreigntradeproductsonly,thentherateofexchangebetweenthetwocurrency

unitswillapproximate closelyto theratiooftheirpurchasing powerso calculated...

But thatis not theconditionof equilibrium ... It is to thepricelevelin general,

ofhometradeproductsas wellas foreign tradeproducts, thattherateofexchange

mustadjust" (Hawtrey,1919,p. 109).

To completelydivorcethe determinationof exchangeratesfromconsidera-

tions of commodityarbitrage,one could even go furtherin developingan

argumentforusingpriceindicesof non-tradedgoods only.Such an argument

was advanced by Graham:

"Strictlyinterpreted

then,pricesof non-internationally

tradedcommoditiesonly

shouldbe includedin the indiceson whichpurchasing powerpars are based"

(Graham,1930,p. 126,n. 44).

Furtherpursuitofthat idea leads to the use ofthe priceofthe least traded

commodity-thewage rate parity-advocated by Rueffin 1926 (reproduced

in Rueff,1967),and similarviewscan also be foundin Hawtrey(1919,p. 123)

and Cassel (1930,p. 144). The wagerate approachwas extendedto the concept

of productioncost paritiesadvocated by Hansen (1944, p. 182), Houthakker

(1962,pp. 293-4) and Friedmanand Schwartz(1963,p. 62).

Whateverthe price index used for computationsof parities,the question

remainsof distinguishing betweenan equilibriumrelationshipand a causal

relationship.Most authorsrecognizedthat pricesand exchangerates are de-

terminedsimultaneously.A minority,however,argued that there exists a

causal relationshipbetweenprices and exchangerates. While Cassel (1921)

claimedthat the causalitygoes frompricesto the exchangerate,Einzig (1935,

p. 40) claimedthe opposite.

1.2. The Asset View

Since in generalbothpricesand exchangeratesare endogenousvariablesthat

are determinedsimultaneously, discussionsof the link betweenthemprovide

littleinsightsinto the analysisof the determinants of the exchangerate. The

originalformulation of Cassel (1916) was statedin termsof the relativequan-

titiesof money.The formulation was then translatedinto a relationshipbe-

tweenpricesvia an applicationofthe quantitytheoryofmoney.Conceptually,

however,it seemsclear that the role of pricesin Cassel's computationof the

equilibriumexchangerate servesonlyto proxythe underlying monetarycon-

ditions.The determination of exchangerates does not seem to rely,directly

or indirectly,

on the operationof arbitragein goods.

In retrospectit seems that the translationof the theoryfroma relation-

ship betweenmoneysinto a relationshipbetweenprices-via the quantity

theoryof money-was counterproductive and led to a lack of emphasison

the fundamentaldeterminantsof the exchangerate and to an unnecessary

amountof ambiguityand confusion.It is noteworthy that the originatorsof

Scand. J. of Economics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

201 J. A. Frenkel

the theory(althoughnot in its presentname)-Wheatley (1803) and Ricardo

-stressed themonetarynatureoftheissuesinvolvedas wellas theirrelevance

of commodityarbitrageas determining the equilibriumrate:

"In speakingof the exchangeand the comparative value of moneyin different

countries,we mustnotintheleastreferto thevalueofmoneyestimated in commo-

ditiesin eithercountry.

The exchangeis neverascertained

by estimatingthecom-

parativevalueofmoneyin corn,clothoranycommodity whateverbutbyestimat-

ingthevalueofthecurrency ofonecountry, in thecurrencyofanother"(Ricardo,

1821,p. 128).

When consideringmoneysfor the purpose of determiningthe exchange

rate,the relevantconceptis that of a stockratherthan of a flow.These con-

ceptswerean integralpart ofmonetarytheory:

"We mayconsequently thinkofthesupply(ofcurrency) as we thinkofthesupply

ofhouses,as beinga stockratherthantheannualproduce... (and) ofthedemand

forcurrency as beingfurnishedby the abilityand willingnessof personsto hold

currency"(Cannan,1921,pp. 453-4).

Indeed, as Dornbusch(1976) puts it "The exchangerate is determined in the

stock market". It is this conceptionof money as a stock that resultedin

Keynes' perceptivestatementthat was quoted at the start of this paper.

The asset view of exchangerate determination became the traditionalview

as witnessedby Joan Robinson:

"The traditional

viewthattheexchangevalueofa country's in anygiven

currency

situationdependsuponthe amountof it in existenceis thusseento be justified,

providedthatsufficientallowanceis madeforchangesin theinternaldemandfor

money"(Robinson,1935-6,p. 229).

I.3. The Role of Expectations

A natural implicationof the asset approachis the special role expectations

play in determining the exchangerate. The demandfordomesticand foreign

moneysdepends,like the demandforany otherasset, on the expectedrates

of return.Thus it may be expectedthat currentvalues of exchangeratesin-

corporatethe expectationsof market participantsconcerningthe future

courseofevents.This notioncan accounttherefore, forlargechangesin prices

resultingfromlargechangesin expectations.This was indeedthe logicalargu-

ment used by Mill (1864, p. 178) in accountingforthe sharp changein the

priceof billsoccuringwiththe newsof Bonaparte'slandingfromElba.

The specificrole of expectationsin determining the exchangerate has been

also emphasizedby Marshall(1888), Wicksell(1919, p. 236), Gregory(1922,

p. 90) and Einzig (1935, p. 120). If the foreignexchangemarketis efficient

-as many otherasset marketsappear to be-then currentpricesshouldre-

flectall available information.

Therefore, an expectationof monetaryexpan-

sion shouldbe reflectedin the currentspot exchangerate since asset holders

willincorporatethe anticipatedreductionin the real rate ofreturnon the cur-

Scand. J. of Economic8 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A monetary

approachtotheexchange

rate 205

rencyin theirpricingof the existingstocks.This notionwas clearlystatedby

Cassel:

"A continuedinflation

... willnaturallybe discounted

to a certaindegreein the

presentratesofexchange"(Cassel,1928,pp. 25-26).

Similarly:

"The international

valuationofthecurrency will,thengenerally

showa tendency

to anticipateevents,so to speak,and becomesmorean expression oftheinternal

value thecurrencyis expectedto possessin a fewmonths,or pherhapsin a year's

time"(Cassel,1930,pp. 149-50).

The empiricalanalysisin Section II will be concernedwith details of the

roleof expectationsin determining the exchangerate.

Prior to concludingthis sectionit should be emphasizedthat its purpose

has notbeen to arguethat "It's all in Marshall".On the contrary,

a rereading

of the writingsof some of the eminentclassicaland neo-classicaleconomists

revealsthe greatneed forsupplementing theirgeneralconceptionswitha de-

tailed analysisof the transmission mechanisms.On theotherhand,however,

it is importantto gain perspectiveand to recognizethat someofthe general

conceptionsand framework ofanalysishave alreadybeen developedby earlier

generationsof economists.It is appropriate,therefore, to view the recent

revivalofthe monetaryapproachas a naturalevolutionratherthan a revolu-

tionarychangein views.'

II. Empirical Evidence: A Reexamination of the German

Hyperinflation

The foregoingdiscussioncontaineda doctrinalperspectiveto the assets ap-

proach to the determination of exchangerates. In this sectionwe develop

further someofthe theoreticalaspectsand reexaminethe determinants ofthe

exchangerate duringthe Germanhyperinflation in lightof theseconsidera-

tions. That episodeis of special interestsince it providesan opportunity to

examinethe assets approachto a situationin whichit is clearthat the source

of disturbancesis monetary.Furthermore, duringthe hyperinflation domestic

1 There are, of course, fundamentaldifficultiesin definingthe nature of the various junc-

tions of intellectualunderstanding.As noted by H. G. Johnson: "the concept of revolution

is difficultto transferfromits originsin politics to otherfieldsof social science. Its essence

is unexpected speed of change, and this requires a judgement of speed in the context of a

longer perspective of historicalchange the choice of which is likely to be debatable in the

extreme" (Johnson, 1971, p. 1).

A casual reading of many of the popular textbook versions of balance of payments

theoriessuggests,however,that the conditions,outlined by Johnson,fora rapid propaga-

tion of a new theorymay be satisfied:"the most helpfulcircumstancesfora rapid propaga-

tion of a new and revolutionarytheoryis the existence of an established orthodoxywhich

is clearly inconsistentwith the most salient facts of reality,and yet is sufficiently

confident

of its intellectualpower to attemptto explain those facts,and in its effortsto do so exposes

its incompetencein a ludicrous fashion" (Johnson, 1971, p. 3).

Scand. J. of Economics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

206 J. A. Frenkel

(German)influenceson the exchangerate dominatethose occurringin the

possibleto examinetherelationship

restof the world.It is therefore between

monetaryvariablesand the exchangerate in isolationfromotherfactors,at

homeand abroad,whichin a morenormalperiodwouldhave to be considered.

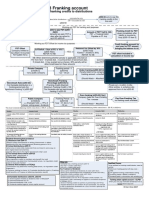

I.1. Moneyand theExchangeRate

Priorto a moreelaborateanalysisit may be instructiveto examinethe as-

sociationbetweenthe Germanmoneystockand its relativepricein termsof

foreignexchange(i.e., the exchangerate). This associationis shownin Figure

1 whichdescribesthe time seriesof the monthlylogarithmsof the German

money supply and the mark/dollar exchangerate for the period February

1920-November1923 (data sourcesare outlinedin the Appendix).As evident

fromFig. 1 the two timeseriesare closelyrelated.A highsupplyof German

marksis associatedwithits depreciationin termsofforeignexchange.

This relationshipcan be examinedfurtherby estimatinga polynomialdis-

tributedlag of the effectsof the moneysupply on the exchangerate. The

estimatesreportedin Table 1 pertainto (i) the effectsof currentand lagged

values of the money supply on the currentlevel of the exchangerate and

(ii) the effectsof currentand laggedvalues oftheratesofchangeofthe money

supplyon the currentrateof changeof the exchangerate. The estimatesof

the distributedlags forthe equationof the ratesofchangerevealthatthecur-

rentrate of changeof the exchangerate dependsonly on the currentrate of

DATE

2002

2005 _

2008 _

2011

2102 _ M

2105 _ . LOG MONEY

2108

2111

2202 _

2205 _

2208 -

2211

_ LOG EXCHANGE RATE

2302 -

2305

2308 _

2311 -

Fig. 1.

Scand. J. of Economics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

approachtotheexchangerate 207

A monetary

Table 1. Moneyand theexchange lag model.Monthly

rate:polynomialdistributed

data: February1920-November1923

Lag structure

0 1 2 3 4 5 Sum

1.032 - 0.019 - 0.248 -0.009 0.348 0.468 1.572

(0.140) (0.099) (0.127) (0.082) (0.107) (0.125) (0.177)

Dependent variable: Log Exch.

R2 = 0.996, s.e. c 0.379, D.W. = 2.05, e = 0.775, au = 0.617

0.975 0.114 -0.186 -0.136 0.052 0.168 0.987

(0.147) (0.121) (0.130) (0.101) (0.189) (0.203) (0.357)

Dependent variable: A Log Exch.

R2 = 0.895, s.e. = 0.390, D.W. = 2.27

Note: In the polynomial distributed lag equation, a fourthdegree polynomial with the

sixth lag coefficientconstrained to zero, was employed. The first equation relates the

logarithmof the exchange rate to currentand past levels of the logarithmof the money

supply. The second equation relates the percentage rate of change of the exchange rate to

currentand past percentage rates of change of the money supply. e is the final value of

the first order autocorrelation coefficient.An iterative Cochran-Orcutt transformation

was employed when firstorderserial correlationin the residuals of the regressionequations

was evident. a. given in the Table is the standard errorof the regressionequation when the

autoregressivecomponent of the error is included. All of the other statistics are for the

transformedmodel. Standard errorsare in parentheses below the coefficients.

monetaryexpansion.Furthermore, an accelerationof the rate of monetary

expansion induces an equi-proportionate contemporaneous accelerationin the

rate at whichthe currencydepreciates.None of the laggedvariablesare sta-

tisticallysignificant.The distributedlags on the level of the exchangerate

also show a unit elastic contemporaneous effect.In this case, however,some

lagged values exerta significant effecton the rate of exchange.The sum of

the coefficientsis 1.57, i.e., duringthat periodthe elasticityof the exchange

rate withrespectto the moneystockexceededunity.' The magnification ef-

fectof moneyon the exchangerate is consistentwiththe predictionof Dorn-

busch'smodel (1976a) as well as withthe predictionof the rationalexpecta-

tions modelsof Black (1973) and Bilson (1975). If the moneysupplyprocess

is generatedby an autoregressive scheme,expectationswill multiplythe in-

fluenceof currentchangesin the moneystocksince these changesare trans-

mittedinto the futurethroughthe autoregressive scheme.2

1 The firstequation in Table 1 should be interpretedwith some caution since the high

first order autocorrelation coefficientmay reflect a misspecification.Its purpose is to

provide a preliminarydescription of the relationship between money and the exchange

rate. A more detailed analysis follows.

2 Previous empirical work emphasizing monetary considerations in the analysis of the

German exchange rate during the hyperinflationinclude Graham (1930), Bresciani-

Turroni (1937) and more recently,Tsiang (1959-60) and Hodgson (1972).

Sand. J. of Economic8 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

208 J. A. Frenkel

II.2. TheBuildingBlock8oftheMonetary

Approach

The foregoinganalysisindicatedthe close associationbetweenmonetaryde-

velopmentsand the exchangerate. In thissectionwe outlinethe majorbuild-

ing blocksof the monetaryapproachto the exchangerate. Since in what fol-

lows we apply the frameworkto examine data pertainingto the German

hyperinflation,the followingpresentationis simplifiedconsiderablyby ignor-

ing developments in the restof the world.

Considerfirstthe demandforreal cash balancesmd as a functionofthe ex-

pectedrate ofinflationa*:

md g(n*);aga*<0 (1)

The formulation in eq. (1) reflectsthe assumptionthat duringthe hyperin-

flation,changesin the demandformoneyweredominatedby changesin in-

flationaryexpectationsso that the effectsof changesin outputand the real

rate ofinterestmay be ignored.

The supplyof real balances is MIP whereM denotesthe nominalmoney

stockand P "the" pricelevel (we bypassforthe momentthe questionofwhat

is theappropriatepricelevel). Equatingthe supplyofmoneywiththe demand

enablesus to expressthe pricelevel as a functionofthe nominalmoneystock

and inflationaryexpectations:

P = M/g(n*); aP/SM > 0, aP/ln*> 0. (2)

The elasticityofthe pricewithrespectto a* shouldapproximatethe (absolute

value of the) interestelasticityof the demandformoney,and in the absence

of moneyillusionthe elasticityof the pricewithrespectto the moneystock

shouldbe unity.

The secondbuildingblock of the theorylinksthe domesticpricelevel with

the foreignpricelevelP* throughthe purchasingpowerparitycondition:

P = SP* (3)

If the purchasingpowerparityconditionholds we can substituteeq. (3)

into (2) to get a relationshipbetweenthe exchangerate, the moneystock,

inflationaryexpectationsand the foreignpricelevel. Since duringthe German

hyperinflation it is justifiableto assumethat P* is practicallyfixed(as com-

pared withP), we can normalizeunits and defineP* as unity.Thus the ex-

changerate can be writtenas

S = M/g(nc*);bS/M > 0; aS/an*> 0. (4)

that theimplicationthataS/az*> 0 is in conflictwithsome

It is noteworthy

ofthetheoriesofexchangeratedetermination. It shouldbe possible,therefore,

to discriminateamong alternativetheoriesby examiningthe empiricalrela-

tionshipbetweenanticipatedinflationand the exchangerate. A popularana-

Scand. J. of Economice 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A monetary

approachtotheexchange

rate 209

7r*

7 CL

MO MO M

_I -, S Pa

Fig. 2.

lysisof this relationshipgoes as follows:a higheranticipatedinflationraises

the nominalrate ofinterestwhichinducesa surplusin the capital accountby

attractingforeigncapital,and therebyinducesa lowerspotexchangerate(i.e.,

an appreciationof the domesticcurrency).A variantof this approachwould

arguethat the higherrate ofinterestlowersspending,and thusinducesa sur-

plus in the balance of paymentswhichleads to a lowerspot exchangerate. A

thirdvariantwouldreachthe same resultby emphasizingthe implicationsof

the interestparitytheory(whichis discussedin the next Section). Accord-

ingly,a higherrate of interestimpliesa higherforwardpermiumon foreign

exchangeand if the risein the forwardexchangerate is insufficient to induce

the requiredpremiumon foreignexchange,the spot exchangeratewillhave to

fall (i.e., the domesticcurrency willhave to appreciate).Whateverthe route,

the above analysespredicta negativerelationshipbetweentherateofinterest

and the spot exchangerate whileequation (4) predictsa positiverelationship.

The alternativetheorypresentedhereemphasizesthe role of asset equilib-

riumin determining the exchangerate and its implicationsare illustratedin

Fig. 2. A risein anticipatedinflationfrom74 to a* lowersthe demandforreal

balances, and given the nominalmoneystock,asset equilibriumrequiresa

higherpricelevel. Since the domesticprice level is tied to the foreignprice

via the purchasingpowerparity,and sincethe foreignpriceis assumedfixed,

the higherpricelevelcan onlybe achievedthrougha risein the spotexchange

rate fromSOto S1 (i.e., a depreciationofthe domesticcurrency).

The foregoing analysisdid not specifythe cause of the risein the domestic

rate ofinterest.It is necessaryto emphasizethat the exact analysisof the ef-

fectsof a changein interestratesdependsupon the sourceofthe disturbance.

The presumption,however,is that duringthe hyperinflation the source of

disturbanceswas monetary.The higherinterestrate may be thoughtofas re-

sultingfroma rise in the rate of monetaryexpansionwhichis immediately

15-764816 Scand. J. of Economics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

210 J. A. Frenkiel

incorporated(via the Fishereffect)in inflationary expectations;to complete

the experiment,it is possibleto imagine(at least analytically)an acceleration

in the monetarygrowthrate whichdoes not instantaneously affectthe mone-

tarystock.

The resulthas an intuitiveappeal in that easy moneyinducesa deprecia-

tionofthe currency. It emphasizesagain the possibleconfusionthatmay arise

fromviewingtheinterestrate as an indicatoroftightor easy monetarypolicy.

The traditionalexpectationof a negativerelationshipbetweeninterestrates

and the exhangerate may, however,be reconciledwith the asset approach

if it emphasizesthe shortrun liquidityeffectof monetarychanges.Thus, in

the shortrun,a higherinterestrate is due to tightmoneywhichinducesan

appreciationof the currency(Dornbusch, 1976a). During hyperinflation,

however,the expectationseffectcompletelydominatesthe liquidityeffect

resultingtherefore in a predictedpositiverelationshipbetweenthe rate of in-

terestand the priceof foreignexchange.

The previousdiscussionemphasizedthe role of expectationsabout future

eventsin determining the currentvalue of the exchangerate. A major diffi-

cultyin incorporating the roleof expectationsin empiricalworkhas been the

lack of an observablevariablemeasuringexpectations.Thus, forexample,in

analyzingthe demand formoneyduringthe hyperinflation, Cagan (1956) in

his classicstudyconstructeda timeseriesof expectedinflationusinga speci-

fictransformation of the timeseriesof the actual rates of inflation.The con-

ceptualdifficultywithsuchan approachstemsfromthefactthatexpectations

are assumedto be based onlyon past experienceand the choiceofthe specific

transformation used to generatethe seriesof expectationsis to a largeextent

arbitrary.The thirdbuildingblockof the approachinvolvesthe choiceofthe

measureof expectationsthat is appropriateforempiricalimplementation. In

what followswe proposea directmeasureof expectationswhichis then in-

corporatedin the analysisof the determination of the exchangerate.

The fundamentalrelationshipthat is used in derivingthe marketmeasure

of inflationaryexpectationsrelieson the interestparitytheory.That theory

maintainsthatin equilibriumthepremium(or discount)on a forwardcontract

forforeignexchangefora given maturityis (approximately)relatedto the

interestrate differential accordingto:

F-S ._.

S z (5)

whereF and S are theforwardand spotexchangerates(thedomesticcurrency

priceof foreignexchange),respectively, i the domesticrate of interestand id

the foreignrate of intereston comparablesecuritiesforthe same maturity.

Evidence available for various countriesover various time periods suggest

that this parity conditionholds (Frenkel& Levich (1975a, 1975b); foran

earlyanalysisof the 1920's see Aliber(1962)). Although,due to lack ofdata,

Scand. J. of Economics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A monetary

approachtotheexchangerate 211

no comparablestudyhas been done on the periodof the Germanhyperinfla-

tion, it is assumedthat the parityconditionhas been maintained.Further-

more,it is reasonableto assume that duringthe hyperinflation most of the

variationsin the difference betweendomesticand foreignanticipatedratesof

inflationwere due to anticipateddomestic (German) inflation.It follows,

therefore, that the variationsof the forwardpremiumon foreignexchange

(F - S)/S, may be viewedas a measureof the variationsin the expectedrate

ofinflation(as well as the expectedrate of changeof the exchangerate).

II.3. The EfficiencyoftheForeignExchangeMarket

Priorto incorporating the forwardpremiumas a measureof expectations,it

is pertinentto explorethe efficiency of the foreignexchangemarketduring

the turbulenthyperinflation period.Evidenceon the efficiency ofthat market

will supportthe approachof usingdata fromthat marketas the basis forin-

ferenceon expectations.

If the foreignexchangemarketis efficientand ifthe exchangerate is deter-

minedin a similarfashionto otherasset prices,we shouldexpectthe behavior

in that marketto display characteristics similarto those displayedin other

stock markets.In particular,we shouldexpect that currentpricesreflectall

available information, and that the residualsfromthe estimatedregression

shouldbe seriallyuncorrelated.

To examinethe efficacyof the marketwe firstregressthe logarithmof the

currentspot exchangerate,log St, on the logarithmof theone-month forward

exchangerate prevailingat the previousmonth,log Ft-,.

log St = a + b log Ft-, +u (6)

The expectationis that the constanttermdoes not differsignificantly

from

zero, that the slope coefficient

does not differsignificantly

fromunityand

that the errortermis seriallyuncorrelated.Since data on the GermanMark-

Pound Sterling(DM/?)forwardexchangerateare availableonlyforthe period

February 1921-August 1923, eq. (2) was estimatedover those31 months.

The resultingordinary-least-squaresestimatesare reportedin eq. (6') with

standarderrorsin parenthesesbelowthe coefficients.

log St =-0.46 + 1.09 log Ft-, (6')

(0.24) (0.03)

1?2= 0.98, s.e. = 0.45; D.W. = 1.90

As can be seen,the constanttermdoes not differ significantlyfromzeroat the

95 percentconfidencelevel (althoughit seemsto be somewhatnegative),the

slope coefficient

is somewhatabove unity(at the 95 percentconfidencelevel)

and, most importantly, the Durbin-Watsonstatisticsindicatesthat the re-

sidualsare not seriallycorrelated.The factthatthe slope coefficient

is slightly

Scand. J. of Economic8 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

212 J. A. Frenkel

DATE

2101

2104

2107 _

_ - LOG EXCHANGE RATE (SPOT)

2110

2201_ v

2204 _

2207

2210

2301 LOG FORWARDRATE ( )

2304 _

2307

Fig. 3.

above unitymay be explainedin termsof transactioncostsor in termsof the

Keynesianconceptof normal-backwardation (Keynes,1930,vol. II, p. 143).1

Fig. 3 describesthe monthlytimeseriesplot of the logarithmsof the spot

exchangerate and the forwardrate prevailingin the previousmonth.The

generalpatternrevealsthat typically,whenthe spot exchangerate rises,the

forwardrate lies belowit whilewhenthe spot exchangerate fallsthe forward

rate exceeds it. This patternis also suggestedby the fact that the elasticity

ofthe spotratewithrespectto the previousmonth'sforwardrateis somewhat

above unity.

To explorefurtherthe implicationsof the efficient markethypothesiswe

examinewhetherthe forwardexchangerate summarizesall relevantinforma-

tion. In an efficientmarketFt-, summarizesall the information concerning

the expectedvalue of St that is available at periodt-1. Specifically,one of

the itemsofinformation available at t-1 is the stockofinformation available

at t-2, and if the marketis efficient, that information will be containedin

Ft-2. If howeverFt-, summarizesall available information includingthat

containedin Ft-2, we shouldexpectthat adding Ft-2 as an explanatoryvari-

able to the right-hand side of (6) will not affectthe coefficientof determina-

tion and will have a coefficient that is not significantlydifferent fromzero.

Eq. (6") reportsthe resultsof that regression:

log St =-0.45 + 1.10 log Ft, -0.006 log Ft-2 (6")

(0.26) (0.08) (0.08)

R2 = 0.98, s.e. = 0.46; D.W. = 1.91

The resultsin (6") supportthe efficient

markethypothesis.

1 The joint hypothesis that the constant term is zero and that the slope coefficientis

unity is rejected at the 95 percent confidencelevel.

Sand. J. of Economico 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A monetary

approachtotheexchangerate 213

To examinefurtherthe stabilityof the regressioncoefficients duringthe

various phases of the hyperinflation we divided the sample into two parts:

"Moderate" hyperinflation and "severe" hyperinflation, where the latter

characterizedthe last eightmonthsof the sample period.A Chow test was

performed on the estimatesof equations (6') and (6") to test the equalityof

each and everycoefficient of the two sub-period'sregressions. This procedure

showedthat the hypothesisthat the regressioncoefficients do not differbe-

tweenthe two sub-periodscannotbe rejectedat the 95 percentlevel.

The resultsreportedin thissectionprovidesupportto the notionthat dur-

ing the hyperinflation expectationsmay have behaved "rationally"in the

Muthsense.In fact,it shouldnot be surprising that even duringthe turbulent

periodofthehyperinflation theefficientmarkethypothesiscannotbe rejected.

It standsto reasonthatthelargervariabilityofexchangeratesincreasestherate

of returnfromand the amountof resourcesinvestedin accurateforecasting.'

II.4. Prices,Moneyand Expectations

In this sectionwe examinethe empiricalcontentof the firstbuildingblock

of the monetaryapproachto the exchangerate by usingthe marketmeasure

of inflationaryexpectationsin estimatingeq. (2). Log-linearizing

eq. (2) and

addingan errortermyields:

logP = a + b,log M + b2loga* + u (2')

One of the difficultiesof using the double-logformis that duringsome

months,earlyin the sampleperiod,the forwardpremiumon foreignexchange

was negative(reaching-0.8 percentper monthin early 1921) reflecting the

initial expectationthat the price rise has been temporary,that the process

will reverseitselfand priceswillreturnto theirpreviouslevels.Sincethelog-

arithmof a negativequantityis not defined,the independentvariable was

transformed fromn* to (k+a*) whichhenceforth is referred

to as a. Thus,the

estimatedequationwas:

logP =a'+b' log M+b' logn +u. (2")

A maximumlikelihoodestimationof the coefficients in (2") along with the

value of k resultedin a value of k rangingbetween0.9 and 1.1 percentper

month.2For ease of exposition,in what followswe set the value ofk at 1 per-

centper month,and thusthe coefficient b2= b'x*I(l +a*).

1 For an application of the "rational"

expectations hypothesisto the German hyperinfla-

tion see Sargent & Wallace (1973).

2

While the anticipated differencebetween the domestic and the foreignrates of inflation

that is proxied by the forwardpremiumn* may be negative, the nominal rate of interest

may not. In principle,a relevant variable in the demand formoney is "the" nominal rate

ofinterestwhichfrom(5) is equal to a"*+ i*. Our estimateofk, therefore,is not unreasonable

in proxying "the" foreignnominal rate of interest.Since the purpose of this section is to

indicate, in somewhat general terms,the implicationof the firstbuilding block ratherthan

to provide a precise estimate of the parameters of the demand for money, the procedure

that was followed seems justifiable. In a separate paper we apply the market measure of

expectations to a more detailed reexamination of the functionalformand the estimates

of the demand formoney duringthe German hyperinflation(Frenkel, 1975).

Scand. J. of Economic8 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

214 J. A. Frenkel

Table 2. Prices,moneyand expectations.

Monthlydata: February1921-August

1923

Estimated equation: Log P = a + b1log M + b. log nr+ u

Dependent

variable Constant log M log n S.e. R2 D.W. e u

LWPI -5.983 1.021 0.497 0.193 0.996 1.88 0.525 0.227

(0.611) (0.041) (0.061)

LWIG - 5.423 0.997 0.293 0.144 0.998 1.95 0.909 0.366

(0.779) (0.041) (0.053)

LWHG - 4.923 0.983 0.374 0.187 0.996 1.79 0.889 0.429

(0.925) (0.051) (0.069)

LCOL -7.215 1.073 0.236 0.125 0.998 2.13 0.729 .0182

(0.450) (0.029) (0.044)

LWAG - 10.027 1.103 0.194 0.254 0.992 2.06 0.373 0.274

(0.749) (0.051) (0.074)

Note: LWPI =log wholesale price index, LWIG = log imported-goodsprice index, LWHG =

log home-goods price index, LCOL =log cost of living index, LWAG =log wage index.

Standard errorsare in parentheses below each coefficient.e is the final value of the auto-

correlation coefficient.An iterative Cochran-Orcutt transformationwas employed to

account for firstorder serial correlationin the residuals. s.e. is the standard error of the

equation and au is the standard errorof the regressionwhen the autoregressivecomponent

of the erroris included.

It may be recalledthat in postulatingeq. (2) we bypassedthe questionof

the appropriateprice deflator.To a largeextent that questionis empirical

and dependson the theorythat underliesthe derivationof the demand for

money.The presumption, however,is that ifthe aggregatedemandformoney

is dominatedby householdbehavior,thenthe relevantpriceindex shouldbe

the consumerpriceindex (the cost of living).Table 2 reportsthe resultsof

estimatingeq. (2w)usingalternativepricedeflators.Judgedby the goodness

of fit it seemsthat the cost of livingindex is the most appropriatedeflator

although,strictlyspeaking,such a comparisonis insufficient sincethe various

equationsin Table 2 differ in the dependentvariable.

Judgedas a wholeit seemsthattheresultsin Table 2 are consistentwiththe

firstbuildingblock of the monetaryapproach to the exchangerate. In all

cases the elasticityof the pricelevel withrespectto the moneystockis close

to unityand the elasticitywithrespectto a is positiveas predictedfromthe

consideration ofthe demandformoney.

II.5. The PurchasingPowerParity

The secondbuildingblockofthe theoryof exchangerate determination

is the

purchasingpowerparity.The highstatisticalcorrelationbetweenpricesand

the exchangerate typicallyobservedduringperiodsofmonetarydisturbances

led to the developmentof the purchasingpowerparitydoctrine.Figs. 4, 5

Scand. J. of Economics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

approachtotheexchangerate 215

A monetary

DATE

2002 -

2005 f

2008 - i_ LOG WHOLESALE PRICE INDEX

_008

2011

2102 _

2105 _

2108 -

2111 - - LOS EXCHANGERATE

2202

2205 -

2208 -

2211

2302

2305 _

2308 _

2311

Fig. 4.

DATE

2002

200S_

_ - LOG COST OF LIVING INDEX

2008 _

2011

2102 _

2105 _

2108 _

2111

2202 -

2205

2208-

2211_E

2211 LOG EXCHANGE RATE

2302 -

2305 _

2308 _

2311

Fig. 5.

Sand. J. of Economic8 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

216 J. A. Frenkel

DATE

2002

2005_

2008

2011

2102 ..-LOG WAGE

2I 05

2108 _

2111

2202-

2205

2 208

LOG EXCHANGE RATE

22110l

2302

2305

2308

2311

Fig. 6.

and 6 show the relationshipsbetween(DM/$) exchangerate and the whole-

sale priceindex,the cost of livingindex and the wage rate index, and Figs.

7-8 show the relationshipsbetweenthe percentagechange of the exchange

rate and prices.These relationshipscorrespondto the various price indices

advocated forthe computationof purchasingpowerparities.'In view of the

observedhighcorrelationamongpricesand the exchangerate,even the skep-

tics agreedthat the doctrinemay possess an elementof truthwhen applied

to monetarydisturbances(e.g., Keynes (1930, p. 91), Haberler (1936, pp.

37-8), Samuelson(1948,p. 397)).

Table 3 reportsthe resultsof estimatesof the purchasingpowerparityfor

the alternativepriceindices.The estimatedequationsare derivedfromequa-

tion (3) by log-linearizing

and assumingthat duringthat periodP* couldbe

viewed as being fixed.As can be seen this buildingblock of the theoryof

exchangerate determination also standsup ratherwell.In all cases the elasti-

citiesof the exchangerate withrespectto the variouspriceindicesare very

closeto unity.It also seemsthat whilethe cost oflivingindexmay be the ap-

1 In addition to pure monetarydisturbancessome sharp turningpoints in the path of the

exchange rate (and its rate of change) can be attributedto political events whichcreated

facts and affectedexpectations. The followingoutlines some of the critical events that are

reflectedin the sharp turningpoints (based on Tinbergen (1934)). August 29, 1921: Murder

of Erzberger; October 20, 1921: League of Nations decision concerningpartition of Upper

Silesia-renewed disturbances. On that date there was the Wiesbaden agreementbetween

Rathenau and Loucheur concerningdeliveries in Rind. April 16, 1922: Rapallo Treaty

with Russia. June 24, 1922: Murder of Rathenau leading to a heavy depreciation of the

mark. January 11, 1923: Ruhr territoryoccupied by French. End of February 1923: Be-

ginningaction to support the mark. April 18, 1923: Collapse of supportingmeasures.

Sand. J. of Economic8 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

approachtotheexchangerate 217

A monetary

DATE

2102 -

2105

2108- .- _PERCENTAGE CHANGE IN

SPOT EXCHANGE RATE

2111

2202

2205 -

2208 *

2211

2302 _

2305

PERCENTAGE CHANGE

2308- IN WHOLESALE PRICE INDEX

Fig. 7.

propriatedeflatorin estimatingmoneydemandfunctions, the wholesaleprice

index performs best in the purchasingpowerparityequations.'

There remains,however,a questionof interpretation. Does the doctrine

specifyan equilibriumrelationshipbetweenpricesand exchangeratesor does

it,in addition,specifycasual relationships

and channelsoftransmission.While

the highcorrelationbetweenthe variouspriceindicesand the exchangerate

is of someinterestin describingan equilibriumrelationshipor in manifesting

the operationof arbitragein goods (dependingon the priceindex used), they

are oflittlehelpin explainingand analyzingthe determinantsof the exchange

rate.

DATE

210 2

2105

2108 PERCENTAGE CHANGE IN

7SPOT EXCHANGE RATE

2111

2202

2205

2208 _

2211

2302 -

2305

2308 PERCENTAGE CHANGE

COST OF LIVING INDEX

Fig. 8.

1 It is of interestto note that duringthe recentfloat (1973-74) the percentagedeviation of

the wholesale price index frompurchasing power parity exceeded that of the consumer

price index (Aliber (1976)).

Sand. J. of Economics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

218 J. A. Frenkel

Table 3. Exchangerateand prices.Monthlydata: February1921-August 1923

Estimated equation: log S = a + b log P + u

Independent

variable Constant log P s.e. B2 D.W. e au

LWPI 0.146 1.006 0.124 0.998 2.01 0.356 0.135

(0.114) (0.010)

LWIG -0.219 1.058 0.208 0.996 2.01 0.269 0.216

(0.177) (0.017)

LWHG -0.383 1.031 0.215 0.995 2.09 0.471 0.241

(0.244) (0.022)

LCOL 0.115 1.076 0.273 0.993 1.97 0.499 0.325

(0.311) (0.030)

LWAG 4.415 0.887 0.350 0.988 1.94 0.889 0.767

(0.788) (0.070)

LWAG 2.682 1.074 0.360 0.987 1.66 0.471 0.414

2SLS (0.310) (0.038)

Note: LWPI =log wholesale price index, LWIG - log imported-goodsprice index, LWHG =

log home-goods price index, LCOL =log cost of living index, LWAG =log wage index.

Standard errorsare in parenthesesbelow each coefficient.e is the final value of the auto-

correlation coefficient.An iterative Cochran-Orcutt transformationwas employed to

account for firstorder serial correlationin the residuals. s.e. is the standard error of the

equation and au is the standard errorof the regressionwhen the autoregressivecomponent

of the erroris included. To allow fora possible simultaneousequation bias due to the endo-

geneity of the various prices the above equations were also estimated using a two-stage

least squares procedure with the percentage change in the money supply and the money-

bond ratio as instruments.None of the coefficientswas significantlyaffectedexcept for

the equation using LWAG as the independentvariable. The 2SLS estimates are reported

in the last line of the Table.

11.6. The Determinants

oftheExchangeRate

The two buildingblocks analyzed in the previoussectionsprovide the in-

gredientsto the estimationof the determinants of the exchangerate. Given

the foreignpricelevel the purchasingpowerparitydeterminesthe ratioP/S.

Giventhe nominalmoneystockand the state of expectations,the pricelevel

is determinedso as to clearthe moneymarket.These two relationships imply

the equilibriumexchangerate.We turnnow to the estimationofthe emprical

counterpart of eq. (4). Log-linearizing

and addingan errortermyields

log S = a' +b1log M +b1loga +u (4')

whereas before,a 1 + *. The estimatesare reportedin eq. (4") withstandard

errorsbelowthe coefficients:

log S -5.135 + 0.975 log M + 0.591 logo (4")

(0.731) (0.050) (0.073)

R2 = 0.994;s.e. = 0.241;D.W. = 1.91.

As is evidenttheseresultsare fullyconsistentwiththe priorexpectations.

Sand. J. of Economics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A monetary

approachtotheexchange

rate 219

The elasticityof the exchangerate withrespectto the moneystockdoes not

differsignificantlyfromunity (at the 95 percentconfidencelevel) whilethe

elasticityof the spot exchangerate with respectto the forwardpremiumis

positive.The orderof magnitudeof the latterelasticityis similar(in absolute

value) to theinterestelasticityofthe demandformoney.'In comparisonwith

the polynomialdistributedlag of Table 1 it is seen that the standarderrorof

equation (4f) is significantlysmaller.It is also noteworthythat the lower

elasticityof the exchangerate withrespectto the moneystockis consistent

with the intuitiveexplanationprovidedto the high elasticityof Table 1.

Thereit was arguedthat the magnification effectwas due to the role of ex-

pectations.Indeed as is shownin eq. (4f) whenexpectationsare includedas

a separatevariable,the homogeneity postulatereemerges, the magnification

effectof the moneystock disappearsand thusindicatingthat the equations

in Table 1 mighthave been misspecified.

11.7. Conclusions,

Limitationsand Extensions

The foregoinganalysis examinedthe empiricalrelationshipsamong money,

prices,expectationsand the exchangerate duringthe Germanhyperinflation.

Concentrating on that periodprovidedthe opportunity to isolate empirically

some of the key relationshipsrelevantto exchangerate determination. In

particular,special attentionhas been given to simultaneousroles played by

expectationsand by monetarypolicyin determining the exchangerate. The

empiricalresultsare consistentwiththe monetary(or the asset) approachto

the exchangerate.

It shouldbe emphasizedthat the monetaryapproachto the exchangerate

doesnotclaimthat the exchangerate is determinedonlyin the money(orthe

asset) marketand that only stock considerations matterwhileflowrelation-

shipsdo not. Clearly,the exchangerate (likeany otherprice)is determined in

generalequilibriumby the interactionof flow and stockconditions.In this

respectthe asset marketequilibriumrelationshipthat is used in the analysis

may be viewedas a reducedformrelationshipthat is chosenas a convenient

framework.

Concentration on the periodofthe hyperinflationhas, however,someshort-

comings.First it does not provideany insightinto the exchangerate effects

of real disturbanceslike structuralchanges(see forexample Ballasa (1964);

Hekman (1975)). Second, and probablymore important,the rapid develop-

ments occuringduringthe hyperinflation preventeda detailed analysis of

1 Recall that due to the transformationon the independentvariable the (average) interest

elasticityof the exchange rate b2 is b'n*l(1 +?r*) wheren* is the average forwardpremium.

Over the sample period the average a* was about 6.2 percentper month,yieldingtherefore

an estimate of about 112 as the interestelasticity. This estimate of the elasticity is con-

sistent with the estimates in Frenkel (1975) as well as with the predictionsof the various

models of the transactions demand for cash.

Scand. J. of Economic81976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

220 J. A. Frenkel

Table 4. Correlationmatrix:prices,exchangerate and money.Monthlydata

February1920-November1923

LWPI LWIG LWHG LCOL LWAG LEXC LMON

LWPI 1.000 0.9986 0.9985 0.9959 0.9969 0.9992 0.9933

LWIG 1.000 0.9956 0.9934 0.9947 0.9968 0.9942

LWHG 1.000 0.9945 0.9949 0.9987 0.9892

LCOL 1.000 0.9984 0.9956 0.9875

LWAG 1.000 0.9960 0.9927

LEXC 1.000 0.9850

LMON 1.000

Note: LWPI =log wholesale price index, LWIG =log import-goodsprice index, LWHG =

log home-goods price index, LCOL = log cost of living index, LWAG = log wage index,

LEXC =log exchange rate index, LMON =log money supply index.

the channelsof transmission of disturbancesamongthe varioussectorsin the

economy.For example,it mightbe usefulto examinethe exact patternand

chronologicalorder by which monetarydisturbancesget transmittedinto

changesin the various priceindices. The monthlydata used in the present

paper do not permitsuch a detailed analysissince most of the dynamicsof

adjustmentoccur withinthe month.The extentof this phenomenonis re-

flectedin Table 4-a correlation matrixofthevariousvariablesforthemonthly

data over the entireperiod(February1920-November1923).To gaininsight

into the morerefineddetails of the adjustmentprocess,it may be necessary

to analyze the period usingweeklydata. A preliminary examinationof the

weeklydata suggeststhat the variouspricesdo differin the details of their

timepaths but at thisstageno conclusiveevidencecan yet be offered.'

Althoughthe monthlydata do not revealthe detailsofthe adjustmentpro-

cess, theydo reveal some systematicrelationshipsamongthe coefficients of

variationofthe (logarithms ofthe) variablesas reportedin Table 5. As is seen

in Table 5, the coefficient

of variationof the moneystockis about 0.15 while

the coefficients of variationcorresponding to the various price indices are

about twiceas large-about 0.30. In this respectall priceindices (wholesale,

imported-goods, home-goodsand cost of living)displaya commonbehavior.

A thirdgroupof variablesincludesthe variousexchangerates (spot and for-

ward) and the wage rate. All of thesevariablesdisplaya similarcoefficient of

variation-about 0.40. The interestingphenomenaare that the extent of

variationsin the various exchangerates (and in the wage rate) exceeds the

extentof variationsin the variouspriceswhichin turnexceedsthe variation

in the moneystock.Furthermore, in view of the wage rate approachto the

exchangerate (some of the doctrinaloriginsof whichwerementionedin Sec-

tion I), the associationamong variationsin the wage rate and the various

1 An inspection of Figs. 7-8 reveals that changes in the cost of living index

lag behind

changes in the wholesale price index which are closely related to changes in the exchange

rate.

Scand. J. of Economic8 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

approachto theexchangerate 221

A monetary

Table 5. Summarystatistics:prices,exchangerate and money.Monthlydata

February1921-August1923

Standard Coef.of

Variable Mean Variance deviation variation

LMON 15.3567 5.0948 2.2571 0.1469

LWPI 10.0477 9.5613 3.0921 0.3077

LWIG 9.8978 8.6178 2.9356 0.2965

LWHG 10.3210 9.1950 3.0323 0.2938

LCOL 9.4337 7.9337 2.8166 0.2985

LWAG 7.0522 7.6616 2.7679 0.3924

LEXC 8.6235 10.3370 3.2151 0.3728

LSPO 8.6235 10.3370 3.2151 0.3728

LFOR 8.6853 11.0123 3.3184 0.3820

Note: LMON =log money supply index, LWPI =log wholesale price index, LWIG =log

import-goodsprice index, LWHG log home-goods price index, LCOL =log cost of living

index, LWAG =log wage index, LEXC =log (DM/$) spot exchange rate index, LSPO =

log (DM/2) spot exchange rate index, LFOR =log (DM/I) one month forwardexchange

rate index.

exchangerates deservesa special notice.While a detailedanalysisof the im-

plicationsof Table 5 is beyondthescopeofthepresentpaper,it is ofinterestto

notetheassociationamongtheexchangeratesand thepriceoflaborservices-

the commoditywhichmay be mostnaturallyclassifiedas a non-tradedgood.

Appendix: Data Sources

Data on the DM/$ exchangerate (spot) are taken fromGraham(1930) and

fromInternationalAbstractof EconomicStatistics1919-30. London: Inter-

nationalConference of EconomicServices,London, 1934.

The one-monthforwardexchangerate (DM/Y,)as well as the (DM/f) spot

rates are fromEinzig (1937). The primarysourceforthis data is the weekly

circularpublishedby the Anglo-Portuguese Colonialand OverseasBank, Ltd.

(originallythe London branch of the Banco Nacional Ultramarinoof Lis-

bon). The rates quoted are thoseof the Saturdayof each week,but in cases

wherethe marketwas closed, the latest quotation available prior to that

Saturdayis used.

Data on moneysupplyare fromGrahamand HistoricalStatisticsas well

as some interpolations.Prices and wages are fromHistoricalStatisticsand

someinterpolations and primarysources.

OutstandingTreasury-Bills are fromGraham.

Scand. J. ofEconomics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

222 J. A. Frenkel

References

Aliber, R. Z.: Speculation in the foreignex- Cassel, G.: Money and Foreign Exchange

changes: The European experience, 1919- after1919. Macmillan, London, 1930.

1926. Yale Economic E88ays, Spring 1962. Dornbusch, R.: "Discussion". American

Aliber, R. Z.: The firm under fixed and Economic ReviewPapers and Proceedings,

flexible exchange rates. Scandinavian 147-151, 1975.

Journal of Economic878, No. 2, pp. 309- Dornbusch, R.: The theory of flexible ex-

322, 1976. change rate regimes and macroeconomic

Angell, J. W.: International trade under in- policy. Scandinavian Journal of Econo-

convertible paper. QuarterlyJournal of mics 78, No. 2, pp. 255-275, 1976.

Economic 36, 309-412, 1922. Dornbusch, R.: Capital mobility, flexible

Balassa, B.: The purchasing power parity exchangerates and macroeconomicequili-

doctrine: a reappraisal. Journal ofPoliti- brium. In E. Claassen and P. Salin (eds.),

cal Economy 72, No. 6, 584-96, 1964. Recent lumes in InternationalMonetary

Bilson, J. F.: Rational expectations and Economics. North-Holland, 1976.

flexible exchange rates. Unpublished Einzig, P.: World Finance, 1914-1935.

manuscript,Universityof Chicago, 1975. Macmillan & Co., New York, 1935.

Black, S. W.: International money markets Einzig, P.: The Theory of Forward Ex-

and flexible exchange rates. Princeton change.Macmillan, London, 1937.

Studie8 in InternationalFinance, No. 32. Ellis, H. S.: The equilibrium rate of ex-

Princeton University,1973. change. In Explorations in Economics.

Besciani-Turroni,C.: The purchasingpower Notes and Essays contributedin honorof

parity doctrine. Egypte Contemporaire, F. W. Taussig. McGraw-Hill, New York,

1934. Reprintedin his Saggi Di Economia, 1936.

1961, Milano, pp. 91-122. Frenkel, J. A.: Adjustmentmechanismsand

Bresciani-Turroni,C.: The Economic8of In- the monetaryapproach to the balance of

flation.Allen & Unwin, London, 1937. payments. In E. Claassen and P. Salin

Bunting, F. H.: Purchasing power parity (eds.), Recent Issues in International

theory reexamined. Southern Economic Monetary Economics. North-Holland,

Journal 5, No. 3, 282-301, 1939. 1976.

Cagan, P.: The monetary dynamics of Frenkel, J. A.: The forwardexchange rate,

hyperinflation. In M. Friedman (ed.), expectations and the demand for money

Studie8 in theQuantityTheoryof Money. during the German hyperinflation.Un-

University of Chicago Press, Chicago, published manuscript, University of

1956. Chicago, 1975.

Cannan, E.: The application of the theore- Frenkel,J. A. & Johnson,H. G.: The mone-

tical apparatus of supply and demand to tary approach to the balance of pay-

units of currency. Economic Journal 31, ments: essential concepts and historical

No. 124, 453-61, 1921. origins. In J. A. Frenkel and H. G.

Cassel, G.: The present situation of the Johnson (eds.), The MonetaryApproach

foreignexchanges. Economic Journal 26, to the Balance of Payments. Allen &

62-65, 1916. Unwin, London and University of Tor-

Cassel, G.: "Comment", Economic Journal onto Press, Toronto, 1976.

30, No. 117, 44-45, 1920. Frenkel, J. A. & Levich, R. M.: Covered

Cassel, G.: The World'8MonetaryProblem8. interest arbitrage: unexploited profits?

Constable and Co., London, 1921. Journal of Political Economy 83, No. 2,

Cassel, G.: Po8t-WarMonetaryStabilization. 325-338, 1975a.

Columbia University Press, New York, Frenkel, J. A. & Levich, R. M.: Transac-

1928. tions cost and the efficiencyof inter-

Scand. J. of Economics 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A monetary

approachtotheexchange

rate 223

national capital markets. Presented at ofPayment. JointEconomic Committee,

the Conferenceon The Monetary Mech- 87th Congress,2nd Session, December 14,

anism in Open Economies, Helsinki, 1962, pp. 289-304.

Finland, August, 1975b. Johnson, H. G.: The Keynesian revolution

Frenkel, J. A. & Rodriguez, C. A.: Portfolio and the monetarist counterrevolution.

equilibrium and the balance of pay- American Economic Review 61, No. 2, 1-

ments: A monetary approach. American 14, 1971. Reprinted in Ch. 7 in H. G.

Economic Review 65, No. 4, 674-88, 1975. Johnson, Economic8and Society.Univer-

Friedman, M. & Schwartz, A.: A Monetary sity of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1975.

History of the United States, 1867-1960. Johnson, H. G.: Theory of international

Princeton University Press, Princeton, trade. In International Encyclopedia of

1963. the Social Science&.The Macmillan Com-

Goschen, G. J.: The Theoryof the Foreign pany and Free Press, 1968.

Exchanges. lst ed. London, 1861; 2nd ed. Johnson, H. G.: World inflation and the

London, 1863; 4th ed. reprinted,1932. international monetary system. The

Graham, F.: Exchange Prices and Produc- ThreeBank8 Review,No. 107, 3-22, 1975.

tion in Hyper-Inflation:Germany,1920- Keynes, J. M.: A tract on monetaryreform.

23. Princeton University Press, Prince- 1st ed. 1923, French Edition, 1924; vol.

ton, N.J., 1930. IV in The Collected Writingsof J. M.

Gregory, T. E.: Foreign Exchange before, Keynes. Macmillan, London, 1971.

duringand afterthe War. OxfordUniver- Keynes, J. M.: A Treati8eon Money. Vol. I.

sity Press, London, 1922. Macmillan, London, 1930.

Haberler, G.: The Theory of International Kouri, P. J. K.: Exchange rate expecta-

Trade. William Hodge and Co., London, tions, and the short run and the long run

1936. effects of fiscal and monetary policies

Haberler, G.: The choice of exchange rates under flexible exchange rates. Presented

after the war. American Economic Re- at the Conferenceon The MonetaryMech-

view 35, No. 3, 308-318, 1945. anism in Open Economies, Helsinki, Fin-

Haberler, G.: A surveyof internationaltrade land, August 1975.

theory.Special Papers in International Lursen, K. & Pedersen, J.: The GermanIn-

Economics 1 (July 1961). International flation 1918-1923. North-Holland, Am-

Finance Section, Princeton University. sterdam, 1964.

Hansen, A. H.: A briefnote on fundamental Marshall, A.: Memorandum to the Effect8

disequilibrium. Review of Economics and which Differencesbetweenthe Currencies

Statistics26, No. 4, 182-84, 1944. of DifferentNations have on International

Hawtrey, R. G.: Currency and Credit. Trade, 1888.

Longmans, Green and Co., 1st ed. 1919, Marshall, A.: Money, Creditand Commerce.

4th ed. 1950, London. London, 1923.

Hekman, C. R.: Structural change and the Metzler,L. A.: The process of international

exchange rate: an empirical test. Un- adjustment under conditions of full em-

published manuscript, University of ployment: a Keynesian view. In R. E.

Chicago, 1975. Caves and H. G. Johnson(eds.), Readings

Heckscher, E. F., et al.: Sweden, Norway, in International Economic8, pp. 465-86.

Denmark and Iceland in the World War. Irwin, Homewood, Ill., 1968.

New Hawen, 1930. Mill, J. S. Principles of Political Economy.

Hodgson, J. S.: An analysis of floatingex- 5th ed. Parker & Co., London, 1862.

change rates: The dollar sterling rate, Mundell, R. A.: Monetary Theory. Pacific

1919-1925. Southern Economic Journal Palisades, Goodyear, 1971.

39, No. 2, 249-257, 1972. Mundell, R. A.: International EconomiC8.

Houthakker, H. S.: Exchange rate adjust- Macmillan, New York, 1968.

ment. Factors Affectingthe U.S. Balance Mussa, M. L.: A monetary approach to ba-

Sand. J. of Economica 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

224 J. A. Frenkel

lance of payments analysis. Journal of Rueff,J.: Balance of Payments. Macmillan,

Money, Credit and Banking 6, No. 3, New York, 1967.

333-351, 1974. Rueff,J.: Les fondements philosophiquesdes

Mussa, M. L.: The exchange rate, the ba- 8yst8meseconomiques.Payol, 1967.

lance of payments and monetary and Samuelson, P. A.: Disparity in postwar

fiscal policy under a regime of controlled exchange rates. In S. Harris (ed.),

floating. Scandinavian Journal of Econo- Foreign Economic Policy for the United

mics 78, No. 2, pp. 229-248, 1976. States, pp. 397-412. Harvard University

Myhrman, J.: Experiences of flexible ex- Press, Cambridge, 1948.

change rates in earlier periods: theories, Samuelson, P. A.: Theoreticalnotes on trade

evidence and a new view. Scandinavian problems. Review of Economics and

Journal of Economic-878, No. 2, pp. 169- Statistics46, No. 2, 145-154, 1964.

196, 1976. Sargent, T. J. & Wallace, N.: Rational

Ohlin, B.: Interregionaland International expectations and the dynamics of hyper-

Trade. Revised ed., Harvard University inflation. InternationalEconomic Review

Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1967; 1st ed. 14, No. 2, 328-50, 1973.

1933. Taussig, F. W.: InternationalTrade. New

Pigou, A. C.: Some problems of foreignex- York, 1927.

changes. Economic Journal 30, No. 120, Tinbergen, J. (ed.): International Abstract

460-472, 1920. of Economic Statistics 1919-30. Inter-

Ricardo, D.: The high price of bullion. national Conferenceof Economic Servi-

London, 1811. In Economic Es8ay8 by ces, London, 1934.

David Ricardo. Edited by E. C. Conner. Tsiang, S. C.: Fluctuating exchange rates in

Kelley, New York, 1970. countrieswithrelativelystable economies

Ricardo, D.: Reply to Mr. Bo0aquet'spracti- IMP StaffPapers 7, 244-273, 1959-60.

cal observationon thereportoftheBullion Viner, J.: Studies in the Theory of Inter-

Committee.London, 1811. In Economic national Trade. Harper and Bros., New

Es8ay8 by David Ricardo. Edited by E. C. York, 1937.

Connor. Kelley, New York, 1970. Wheatley, J.: Remarks on Currency and

Ricardo, D.: Principle8ofPolitical Economy Commerce.Burton, London, 1803.

and Taxation. London, 1821. Edited by Wicksell, K.: The riddle of foreign ex-

E. C. Connor. G. Bell and Sons, 1911. changes. 1919. In his SelectedPapers on

Ringer, F. K. (ed.): The German Inflation Economic Theory. Kelley, New York,

of 1923. Oxford Press, New York, 1969. 1969.

Robinson, J.: Banking policy and the ex-

changes. Review of Economic Studie8 3,

226-29, 1935-36.

Sand. J. of Economica 1976

This content downloaded from 192.231.202.205 on Wed, 26 Nov 2014 03:40:22 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Nielsen Global Home Care ReportDocument39 pagesNielsen Global Home Care ReportNikesh ShahNo ratings yet

- CROMA Products AnalysisDocument4 pagesCROMA Products AnalysisHARSH SHARMANo ratings yet

- Quotation Time Charter (EASTKAL)Document1 pageQuotation Time Charter (EASTKAL)angga subekti100% (1)

- Exchange Rates and The Balance of Payments: Reconciling An Inconsistency in Post Keynesian TheoryDocument27 pagesExchange Rates and The Balance of Payments: Reconciling An Inconsistency in Post Keynesian TheoryGregor SchwindelmeisterNo ratings yet

- Priewe 2004Document31 pagesPriewe 2004Kristina TehNo ratings yet

- McKinnon (1993)Document45 pagesMcKinnon (1993)Bautista GriffiniNo ratings yet

- The New' Theory of Optimum Currency Areas - George S. TavlasDocument23 pagesThe New' Theory of Optimum Currency Areas - George S. Tavlasskylord wiseNo ratings yet

- Brunner The Monetarist Revolution in Monetary TheoryDocument31 pagesBrunner The Monetarist Revolution in Monetary TheorykarouNo ratings yet

- Sharpe1964 (Editable Acrobat)Document19 pagesSharpe1964 (Editable Acrobat)julioacev0781No ratings yet

- A Post Keynesian Framework of Exchange Rate Determination A Minskyan ApproachDocument24 pagesA Post Keynesian Framework of Exchange Rate Determination A Minskyan ApproachFelipe RomeroNo ratings yet

- Ideal Money - John NashDocument9 pagesIdeal Money - John NashjustingoldbergNo ratings yet

- Kapar 2019Document3 pagesKapar 2019sonia969696No ratings yet

- Systematic Liquidity: Gur Huberman and Dominika HalkaDocument18 pagesSystematic Liquidity: Gur Huberman and Dominika HalkaabhinavatripathiNo ratings yet

- Dennis H Robertson and The Monetary Approach To ExDocument9 pagesDennis H Robertson and The Monetary Approach To ExA[N]TELOPE 63No ratings yet

- Interest Rates and Inflation: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Research DepartmentDocument19 pagesInterest Rates and Inflation: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Research DepartmentHarshit JainNo ratings yet

- Taxonomy of Finance TheoriesDocument16 pagesTaxonomy of Finance TheoriesDr. Vernon T Cox0% (1)

- Monetary Policy Under Exchange-Rate FlexibilityDocument37 pagesMonetary Policy Under Exchange-Rate FlexibilityJenNo ratings yet

- A Monetary Explanation of The Equity Premium, Term Premium, and Risk-Free Rate PuzzlesDocument38 pagesA Monetary Explanation of The Equity Premium, Term Premium, and Risk-Free Rate PuzzlesLeszek CzapiewskiNo ratings yet

- Foreign Exchange SpeculationDocument13 pagesForeign Exchange SpeculationKristy Dela PeñaNo ratings yet

- Rabin A Monetary Theory - 271 275Document5 pagesRabin A Monetary Theory - 271 275Anonymous T2LhplUNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Quality of MoneyDocument37 pagesMeasuring The Quality of MoneyAndré M. TrottaNo ratings yet

- Classifying Exchange Rate Regimes: Deeds vs. Words: Eduardo Levy-Yeyati and Federico SturzeneggerDocument27 pagesClassifying Exchange Rate Regimes: Deeds vs. Words: Eduardo Levy-Yeyati and Federico SturzeneggerKasey OwensNo ratings yet

- Diamond 1984Document21 pagesDiamond 1984Cristian Fernando Sanabria BautistaNo ratings yet

- G.M. Constant in Ides, A.G. MalliarisDocument30 pagesG.M. Constant in Ides, A.G. MalliarisphatsaweeNo ratings yet

- Arbitrage in The Foreign Exchange Market: Turning On The MicroscopeDocument44 pagesArbitrage in The Foreign Exchange Market: Turning On The MicroscopeFami mikaelNo ratings yet

- Variations in Trading Volume, Return Volatility, and Trading Costs Evidence On Recent Price Formation ModelsDocument26 pagesVariations in Trading Volume, Return Volatility, and Trading Costs Evidence On Recent Price Formation ModelsSamNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting The Income Velocity of Money in The Commonwealth PDFDocument20 pagesFactors Affecting The Income Velocity of Money in The Commonwealth PDFmaher76No ratings yet

- Foreign Exchange Market and The Asset Approach-IJRASETDocument8 pagesForeign Exchange Market and The Asset Approach-IJRASETIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- BF01676404Document22 pagesBF01676404Mbongeni ShongweNo ratings yet

- Olivera PassiveMoney 1970Document11 pagesOlivera PassiveMoney 1970Héctor Juan RubiniNo ratings yet

- Aepp/ppp 006Document18 pagesAepp/ppp 006sonia969696No ratings yet

- Institutionof FXTradingDocument22 pagesInstitutionof FXTradingelimarcos meloNo ratings yet

- Rabin A Monetary Theory 76 80Document5 pagesRabin A Monetary Theory 76 80Anonymous T2LhplUNo ratings yet

- Informational Integration and FX Trading: Martin D.D. Evans, Richard K. LyonsDocument25 pagesInformational Integration and FX Trading: Martin D.D. Evans, Richard K. LyonsMark StevensNo ratings yet

- Modelo InflaciónDocument17 pagesModelo InflaciónpedroezamNo ratings yet