Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A. Rodriguez Penney Desire

A. Rodriguez Penney Desire

Uploaded by

Alan Rodriguez PenneyOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A. Rodriguez Penney Desire

A. Rodriguez Penney Desire

Uploaded by

Alan Rodriguez PenneyCopyright:

Available Formats

Desire goes way back to ancient times, way before civilization existed when we

developed the neuronal synapses to spark the feelings of craving and want. It is a force, a drive

that guides our behaviors and our thoughts. Religions speak of desire in positive and negative

overtones, depending on the object of desire. The layman’s concept of Buddhism is that desire

is the cause of all suffering.

Desire walks a fine line between being ostracized and encouraged, cautioned and

nurtured. Looking at Morihei Ueshiba’s book The Art of Peace, he mostly describes desire in a

negative context, using words like “petty”, “evil”, and the such. The only exception to this is the

desire to “thirst for more and more training in the Way”. It is with this mindset that Brooklyn

Aikikai sets the tone of the Dojo. On one occasion or another, during one of Sensei’s post-class

reflections, he urges “Pick one thing to work on this week. It can be noticing how your neck is,

not just during training but also when you’re reading. When you’re on your phone. Is it like this

(flexes neck)? Or this (straightens neck)? And then you can pick something else next week.”

Admittedly, it’s not very often I go to my Aikido classes asking myself “What do I desire

in this training?” Or even the general question: “What do I desire out of my training in Aikido?” I

have been doing Aikido for 14 years and most of my focus has been to continuously work on my

technique, learn their names, work with different body types. Sensei usually talks about “big

Aikido”, learning as a means of personal development and growth, and a large reason why

Brooklyn Aikikai incorporates zazen and misogi.

As I pondered the latter question, it dawned upon me that this unusual persistence in a

single martial art stems from a desire to discover. Aikido is a dynamic martial art that is always

slightly different depending on what technique I’m doing, what side, what height, what body

type. There are so many variables, that it becomes an enriching way of having a conversation

through body art. Very subtle things like shifting my weight and the position of my fingers and

tailbone can make a world of difference. Hence, each ikkyo is always slightly different, and as

Heraticlus would philosophize, “You cannot step into the same river twice, for other waters are

continually floating on”. This continual discovery is what makes it so interesting, and when I’m

frustrated about not being able to get a technique or get the ukemi quite right, it is welcomed as

an acknowledgement that I have something to learn.

There are many paths of discovery in the practice of Aikido that vary from person to

person. If we imagine a mountain, there are many paths to climb towards the top. We can

incorporate other practices to complement our paths. Antonio Machado, a poet and a

philosopher, writes that there is no path to follow except the one that you make. Learning and

growing is a process that gives my life meaning, and it is this that fuels my desire to Aikido.

You might also like

- The Journey of UCADocument838 pagesThe Journey of UCAwolfpathe100% (5)

- The 7 Energies of the Soul: Awaken Your Inner Creator, Healer, Warrior, Lover, Artist, Explorer, and MasterFrom EverandThe 7 Energies of the Soul: Awaken Your Inner Creator, Healer, Warrior, Lover, Artist, Explorer, and MasterRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Way of Aiki: A Path of Unity, Confluence and HarmonyFrom EverandThe Way of Aiki: A Path of Unity, Confluence and HarmonyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Aikido Student ManualDocument89 pagesThe Aikido Student Manualsrbjkd100% (4)

- Realizing BodymindDocument7 pagesRealizing BodymindKickingEdgarAllenPoeNo ratings yet

- Mushin KarateDocument48 pagesMushin KarateBob Harwood100% (1)

- Yoga Gave Me Superior HealthDocument261 pagesYoga Gave Me Superior Healthrmuruganmca100% (1)

- Asanas The Complete Yoga Poses Daniel Lacerda PDFDocument1,132 pagesAsanas The Complete Yoga Poses Daniel Lacerda PDFSamanthaPerera100% (2)

- 11 Intro To Philo As v1.0Document21 pages11 Intro To Philo As v1.0jerielseguido-187% (15)

- How To Request A Letter of RecommendationDocument2 pagesHow To Request A Letter of RecommendationddddsfsdNo ratings yet

- Koichi Tohei-This Is AikidoDocument184 pagesKoichi Tohei-This Is AikidoOmar AlfaroNo ratings yet

- Ueshiba Kisshomaru - The Spirit of AikidoDocument121 pagesUeshiba Kisshomaru - The Spirit of AikidoIT SOLUTIONS100% (2)

- The Seidokan Communicator, October 1997Document6 pagesThe Seidokan Communicator, October 1997Sean LeatherNo ratings yet

- An Open Secret: A Student’s Handbook for Learning Aikido Techniques of Self-Defense and the Aiki WayFrom EverandAn Open Secret: A Student’s Handbook for Learning Aikido Techniques of Self-Defense and the Aiki WayRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Martial Arts - Experiences and Teachings of AikidoDocument58 pagesMartial Arts - Experiences and Teachings of AikidoChristopher SawyerNo ratings yet

- Earl Hartman - Essay On Kyudo TrainingDocument27 pagesEarl Hartman - Essay On Kyudo TrainingMeelis JoeNo ratings yet

- Satori: Enlightenment or A DreamDocument7 pagesSatori: Enlightenment or A DreamAdelSoftNo ratings yet

- Aikido IdeasDocument31 pagesAikido IdeasAris MursitoNo ratings yet

- Black Belts Only: The Invisible But Lethal Power of KarateFrom EverandBlack Belts Only: The Invisible But Lethal Power of KarateRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Japanese YogaDocument133 pagesJapanese YogaMinh Pham Ngoc100% (2)

- Zenshinkan Student HandbookDocument20 pagesZenshinkan Student HandbookalejandraNo ratings yet

- Kokorozashi - The Pursuit of Meaning in BusinessDocument120 pagesKokorozashi - The Pursuit of Meaning in BusinessYecid Alberto Mateus PradaNo ratings yet

- Ki in Daily LifeDocument9 pagesKi in Daily LifejovicasimicNo ratings yet

- Your Body As Teacher Anna CrowleyDocument4 pagesYour Body As Teacher Anna Crowleyc almaNo ratings yet

- The Dao That Is Tai Chi Chuan: Traditional Martial Arts AssociationDocument3 pagesThe Dao That Is Tai Chi Chuan: Traditional Martial Arts AssociationNicolas DrlNo ratings yet

- SiFu Donald Mak SanBao Mag 2013-01 PDFDocument4 pagesSiFu Donald Mak SanBao Mag 2013-01 PDFBudo MediaNo ratings yet

- Aiki ManDocument39 pagesAiki ManGas PochoNo ratings yet

- M D - July03 2009Document5 pagesM D - July03 2009so-xenolithNo ratings yet

- Manual de Hsing I de Li JianqiuDocument43 pagesManual de Hsing I de Li JianqiuandreaguirredoamaralNo ratings yet

- Attachment3 Papas ArisDocument4 pagesAttachment3 Papas ArisAris PapasNo ratings yet

- East Asia: Masters of The Martial ArtsDocument12 pagesEast Asia: Masters of The Martial ArtsDarra TanNo ratings yet

- Ki Aikido HandbookDocument15 pagesKi Aikido Handbookhrizi100% (5)

- Body As TeacherDocument5 pagesBody As TeacherClaire MoralesNo ratings yet

- AWA Newsletter Fall09Document22 pagesAWA Newsletter Fall09r_rochetteNo ratings yet

- Shugyo One ExplanationDocument1 pageShugyo One Explanationjpana3467No ratings yet

- The Spirit of the Matter: Mysore Style Ashtanga Yoga and the metaphysics of Yoga TaravaliFrom EverandThe Spirit of the Matter: Mysore Style Ashtanga Yoga and the metaphysics of Yoga TaravaliNo ratings yet

- Aiki Budo Tora Ha InformationDocument4 pagesAiki Budo Tora Ha Informationflintstone.comNo ratings yet

- The Martial Artist's Book of Yoga: Improve Flexibility, Balance and Strength for Higher Kicks, Faster Strikes, Smoother Throws, Safer Falls and Stronger StancesFrom EverandThe Martial Artist's Book of Yoga: Improve Flexibility, Balance and Strength for Higher Kicks, Faster Strikes, Smoother Throws, Safer Falls and Stronger StancesNo ratings yet

- Shorinji Kempo by Blue JohnsonDocument5 pagesShorinji Kempo by Blue JohnsonOushizaruNo ratings yet

- KYTHING HEART-Istry in EducationDocument18 pagesKYTHING HEART-Istry in EducationPearl Regalado MansayonNo ratings yet

- Functional Awareness and Yoga - Nancy Romita Allegra RomitaDocument163 pagesFunctional Awareness and Yoga - Nancy Romita Allegra Romitawatiu gonadu100% (1)

- Ki BreathingDocument66 pagesKi BreathingArief AminNo ratings yet

- Aikido Basico (001 050) .Es - enDocument50 pagesAikido Basico (001 050) .Es - enHammamiSalahNo ratings yet

- Find The Right Path Sveneric BogsaterDocument6 pagesFind The Right Path Sveneric BogsaterAl sa-herNo ratings yet

- MM8 Gathering Information and Scanning The EnvironmentDocument18 pagesMM8 Gathering Information and Scanning The EnvironmentRoxette CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Semester - 1: Course Timetable - FOUN 1001 (Evening University), English For Academic Purposes (Evening)Document4 pagesSemester - 1: Course Timetable - FOUN 1001 (Evening University), English For Academic Purposes (Evening)Alexis SinghNo ratings yet

- FUIW University Rankings (QS, THE, SCI, WEBO)Document8 pagesFUIW University Rankings (QS, THE, SCI, WEBO)ali abtalNo ratings yet

- Structural Reliability and Risk AnalysisDocument146 pagesStructural Reliability and Risk AnalysisAlexandru ConstantinescuNo ratings yet

- 4th Grade Newsletter OctoberDocument1 page4th Grade Newsletter Octoberapi-261669210No ratings yet

- RRL New Normal SchoolingDocument2 pagesRRL New Normal SchoolingAlthea Curie DomingoNo ratings yet

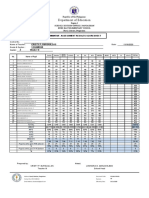

- Diamond Second Quarter Summative Test ResultDocument11 pagesDiamond Second Quarter Summative Test ResultDaesungNo ratings yet

- © Copyright, IAU, World Higher Education Database (WHED)Document11 pages© Copyright, IAU, World Higher Education Database (WHED)ch3tanNo ratings yet

- Brain Development: What We Know About How Children LearnDocument7 pagesBrain Development: What We Know About How Children Learnpradip_26No ratings yet

- 20230027: 2022-2023 2nd Term: Baguio Nezel Mae R: BEED 1stDocument1 page20230027: 2022-2023 2nd Term: Baguio Nezel Mae R: BEED 1stAngelie BranzuelaNo ratings yet

- Desain Ruang Pembelajaran Outdoor Bagi Kelompok Belajar (KB) Paud Terpadu Al-Furqan JemberDocument16 pagesDesain Ruang Pembelajaran Outdoor Bagi Kelompok Belajar (KB) Paud Terpadu Al-Furqan JemberDila MahardhikaNo ratings yet

- Execsum Apr 07Document15 pagesExecsum Apr 07Prashant RawatNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Preparation of Study Proposals For Funding Under The Uplb Basic Research ProgramDocument2 pagesGuidelines For The Preparation of Study Proposals For Funding Under The Uplb Basic Research ProgramrationalbossNo ratings yet

- Algebra Recap and Review (H) MSDocument2 pagesAlgebra Recap and Review (H) MSOana AlbertNo ratings yet

- Department of Cbucnion: Guidelines On Recruitment, Selection, and AppointmentDocument151 pagesDepartment of Cbucnion: Guidelines On Recruitment, Selection, and AppointmentAVELYN JAMORANo ratings yet

- Megan's ResumeDocument3 pagesMegan's ResumeMegan KnickerbockerNo ratings yet

- Terminal Report For Work ImmersionDocument2 pagesTerminal Report For Work Immersionfloreslorna86No ratings yet

- Therapetic Patient EducationDocument90 pagesTherapetic Patient EducationNurul HudaNo ratings yet

- Cronbacs Real StatDocument72 pagesCronbacs Real StatSer GiboNo ratings yet

- ISE I Trinity With AnswerDocument13 pagesISE I Trinity With AnswerPatricia SCNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: Secondary English Ed: Victorian Literature Review Lecture and Assignments (Ed Tech)Document4 pagesLesson Plan: Secondary English Ed: Victorian Literature Review Lecture and Assignments (Ed Tech)api-346999242No ratings yet

- Mathematics 9 - W3 - Module-5 For PrintingDocument20 pagesMathematics 9 - W3 - Module-5 For PrintingRONALD GACUTARA0% (1)

- DU PG Eligiblity Criteria 2015Document71 pagesDU PG Eligiblity Criteria 2015Neepur GargNo ratings yet

- Training Personal HygieneDocument3 pagesTraining Personal HygieneagswaluyoNo ratings yet

- DLSU D Undergraduate Research Handbook 2021 Approved by Academic Council2Document43 pagesDLSU D Undergraduate Research Handbook 2021 Approved by Academic Council2MicaNo ratings yet

- Genre-and-English-for-Specific-Purposes-WR s1Document5 pagesGenre-and-English-for-Specific-Purposes-WR s1jayson gargaritanoNo ratings yet

- Essentials of Strength Training and Cond PDFDocument36 pagesEssentials of Strength Training and Cond PDFLuis CastilloNo ratings yet

- StaticsDocument2 pagesStaticsAlonsoNo ratings yet