Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Memorial

Memorial

Uploaded by

Know NowOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Memorial

Memorial

Uploaded by

Know NowCopyright:

Available Formats

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 I

TEAM CODE: ALS-01

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW, 2019

BEFORE THE HON’BLE

SUPREME COURT OF INDIANA

ORIGINAL JURISDICTION

PIL UNDER ARTICLE 32 OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIANA

PIL NO: ___/ 2019

THE INDIANA YOUNG LAWYER ASSOCIATION & ORS.

………PETITIONERS

VERSUS

UNION OF INDIANA & ORS. ……...RESPONDENTS

WRITTEN SUBMISSION ON BEHALF OF THE RESPONDENTS

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 II

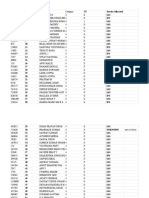

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS- - - - - - - - IV

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

BOOKS REFERRED - - - - - - - VI

ARTICLES & JOURNALS - - - - - - X

TABLE OF CASES - - - - - - - XII

STATUTES - - - - - - - - XVII

INTERNATIONAL CONVENTIONS - - - - - XVIII

REPORTS - - - - - - - - - XVIII

DICTIONARIES - - - - - - - - XVIII

OTHER PUBLICATIONS - - - - - - XIX

ONLINE SOURCES - - - - - - - XIX

STATEMENT OF FACTS - - - - - - - XXI

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION - - - - - - XXII

STATEMENT OF ISSUES - - - - - - - XXIII

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENTS - - - - - - - XXV

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED - - - - - - - 1

I. THE PETITIONER AND THE SUBSEQUENT INTERVENERS DO NOT HAVE THE LOCUS

TO FILE THE PRESENT WRIT PETITION- - - - - - 1

1.1 The Petitioners have the Locus standi but it is flouted- - - 1

1.2 The Present Petition is not driven by the noble cause of public interest. 2

1.3 The Petition cannot be filed against the Tenji board as it is not an

instrumentality of State.- - - - - - - 3

II. THE SUPREME COURT HAS LIMITED JURISDICTION IN DEFINING BOUNDARIES OF

RELIGION IN PUBLIC SPACES- - - - - - - 4

2.1 The rationality of religious practices is outside the ken of the Courts - 4

2.2 Hindu Temples are regulated by Agama Shastras - - - 6

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 III

2.3 Religion falls under custom and usage in Article 13 - - - 7

2.4 Separation of Powers and Judicial Overreach - - - 8

III. THE SAID RESTRICTION IMPOSED ON THE WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF CERTAIN

AGE DOES NOT AMOUNT TO VIOLATION OF THEIR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS IN LIGHT

OF RULE 3(b) OF TENJIKU HINDU PLACES OF PUBLIC WORSHIP (AUTHORIZATION

OF ENTRY) RULES. - - - - - - - - 9

3.1 The restriction imposed on the women and children of certain age does not

amount to violation of Article 14 of the Constitution - - 9

3.1.1. The twin test principle is satisfied in the present case - 10

3.1.2. Test of of arbitrariness - - - - - 12

3.2 Article 15 of the Constitution has not been violated - - 12

3.3 The said restriction does not violate Article 17 of the Constitution.- 14

3.4 Article 21 of the Constitution has not been violated.- - - 16

IV. THE PRACTICE OF EXCLUDING SUCH WOMEN CONSTITUTE AN ‘ESSENTIAL

RELIGIOUS PRACTICE’ UNDER ARTICLE 25 AND A RELIGIOUS INSTITUTION CAN

ASSERT A CLAIM IN THAT REGARD UNDER THE UMBRELLA OF RIGHT TO MANAGE

ITS OWN AFFAIRS IN THE MATTERS OF RELIGION. - - - 18

4.1 The practice of selective exclusion of women is an ‘essential religious

practice’ protected under Article 25 of the Constitution. - - 18

4.1.1 Test of essential religious practices – what can be classified as

essential or not. - - - - - - 18

4.1.2 Power or authority to decide what is an essential religious

practice- - - - - - - 20

4.2 The right of a religious institution to manage its affairs in the matters of

religion will prevail in the instant case.- - - - - 22

4.2.1 Characteristics of a religious denomination can be witnessed 22

4.2.2 The said practice is not against ‘public morality’. - 23

PRAYER - - - - - - - - XXVII

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 IV

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

SL. ABBREVIATIONS EXPANSION

NO.

1. & And

2. @ At

3. A.I.R. All India Reporter

4. A.P. Andhra Pradesh

5. All. L.J. Allahabad Law Journal

6. Anr. Another

7. Art. Article

8. Bom. Bombay

9. C.H.N. Calcutta High Court Notes

10. Cal. Calcutta

11. CEDAW Convention on Elimination of All Forms of

Discrimination Against Women

12. Cl. Clause

13. Co. Company

14. Commr. Commissioner

15. Corpn. Corporation

16. Dr. Doctor

17. Edn. / ed. Edition

18. F.C.R. Federal Court Records

19. H.P. Himachal Pradesh

20. Hon’ble Honorable

21. http Hypertext Transfer Protocol

22. I.L.R. Indian Law Reports

23. J&K Jammu and Kashmir

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 V

24. J.L.J. Jabalpur Law Journal

25. K.L.T. Kerala Law Times

26. M.L.J. Madras Law Journal

27. M.P. Madhya Pradesh

28. Mad. Madras

29. Ors. Others

30. P.L.R. Punjab Law Reports

31. Pg. Page

32. Punj. Punjab

33. Pvt. Private

34. R.L.W. Rajasthan Law Weekly

35. S.C.C. Supreme Court Cases

36. S.C.R. Supreme Court Reporter

37. S/§ Section

38. SC Supreme Court

39. U.P. Uttar Pradesh

40. U.S. United States

41. URL Universal Resource Locator

42. v. Versus

43. Vol. Volume

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 VI

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

(A.) Books Referred

SL No: Page

BOOKS

No:

1. ARVIND P.DATAR, COMMENTARY ON THE CONSTITUTION OF 1

INDIA (2nd ed., Lexis Nexis Butterworths Wadhwa, 2007)

2. CHAUDHARY, LAW OF WRITS (1st ed., Law Publishers Pvt. Ltd, 2

1956)

3. D.D. BASU COMMENTARY ON THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA (8th 5,17

ed., Lexis Nexis, 2014)

4. D.L. KEIR &, CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW (4thed., 17

Oxford University Press, 1979)

5. GRANVILLE AUSTIN, THE INDIAN CONSTITUTION (2nd ed., 20

Oxford University Press, 1999)

6. H. M. SHEERVAI, CONCEPT OF INDIAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 18

(3rd ed., Universal Law Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., 2010)

7. J. N PANDEY, CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF INDIA (53rd ed., 2

Central Law Agency, 2016)

8. KAILASH RAI, CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF INDIA (11th ed., 3,15

Central Law Publications, 2015)

9. M. C. JAIN KAGZI, KAGZI’S CONSTITUTION OF INDIA (7th ed., 15

Universal Law Publishing, 2014)

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 VII

10. M. LAXMIKANTH, INDIAN POLITY, (4th ed., MC Graw Hill, 18

2016)

11. M. P. JAIN, INDIAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW (7th ed., Lexis Nexis, 17

2016)

12. MADHAV KHOSLA, THE INDIAN CONSTITUTION (1st ed., Oxford 19

University Press, 2012)

13. B. RAMASWAMYHUMAN RIGHTS OF WOMEN (1st ed., Anmol 16

Publications Pvt. Ltd., 2002)

14. P.M. BAKSHI, THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA (14th ed., Universal 21

Law Publishing, 2017)

15. S.A. PALEKAR, INDIAN CONSTITUTION, GOVERNMENT AND 22

POLITICS (7thed. ABD Publishers 2003)

16. SUBHASH.C. KASHYAP, OUR CONSTITUTION: AN 23

INTRODUCTION TO INDIA’S CONSTITUTION AND

CONSTITUTIONAL LAW (22nd ed.,National Book Trust, 2011)

17. THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF INDIAN CONSTITUTION. (1st 3

Oxford University Press, 2016)

18. N. SHUKLA CONSTITUTION OF INDIA (4th ed., Lexis Nexis, 1

2008)

19. V.KRISHNA ANANTH, THE INDIAN CONSTITUTION AND SOCIAL 9

REVOLUTION (16th ed., Sage India, 1900)

20. ARUN SHOURIE, COURTS AND THEIR JUDGEMENTS (2nd ed., 8

Rupa and Co., 2002)

21. DR. ABHISHEK ATREY, LAW OF WRITS PRACTICE AND 1

PROCEDURE (1st ed., Kamal Publishers, 2016 Eastern Book

Company, 2004)

22. ERIC BARENDT, FREEDOM OF SPEECH (2nded Oxford University 4

Press,2007)

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 VIII

23. JUSTICE B. P. BANERJEE, WRIT REMEDIES (6th ed. Lexis 6

Nexis2013)

24. MONA SHUKLA, INDIAN JUDICIARY AND GOOD GOVERNANCE 8

(1st ed., Regal Publications, 2011)

25. P. ISHWARA BHATT, FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS - A STUDY OF 21

THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIP (2nd, Eastern Law House, 2004)

26. V.G. RAMACHANDRAN, LAW OF WRITS (1st ed. Eastern Book 1

Company, 2007)

4

27. T.K.VISWANATHAN, LEGISLATIVE DRAFTING- SHAPING THE

LAW FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM (1st ed., Indian Law Institute

New Delhi, 2007)

2

28. KARLE PEREZ PORTILLA, REDRESSING EVERYDAY

DISCRIMINATION- THE WEAKNESS AND POTENTIAL OF ANTI-

DISCRIMINATION LAW (1st ed., CPI Group Ltd, Croydon, 2016)

14

29. SANDRA FREDMAN, DISCRIMINATION LAW (2nd, Clarendon Law

Series Book House,2012)

15

30. TARUNABH KHAITAN, THE THEORY OF DISCRIMINATION LAW

(1st ed., Replika Press Pvt. Ltd., 2015)

7

31. RAJEEV BHARGAVA, SECULARISM AND ITS CRITICS (2nd ed.,

Oxford University Press, 2007)

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 IX

5

32. BS MURTHY, SECULARISM , RELIGION AND LIBERAL

DEMOCRACY (1ST ed., Andhra University, 1997)

17

33. RONJOY SEN, ARTICLES OF FAITH RELIGION, SECULARISM AND

THE INDIAN SUPREME COURT (4th ed., Oxford India Publishing

House, 2014)

5

34. IQBAL NARAIN , SECULARISM IN INDIA (1st ed., Classic

Publishing Book House, 1995)

6

35. B.S. CHAUHAN, MAYNE’S TREATISE ON HINDU LAW & USAGE,

834 (17th ed., Bharat Law House, 2017)

6

36. B.M.GANDHI, HINDU LAW 64 (4th ed., Eastern Book Co., 2016)

7

37. MULLA, HINDU LAW 224 (9th ed., Lexis Nexis ,1999)

9

38. N.S.BINDRA, INTERPRETATION OF STATUTES 65 (10th ed., Lexis

Nexis, 2008)

9

39. C.K.TAKWANI, LECTURES ON ADMINISTRATIVE LAW (1st ed.

Lexis Nexis 2008)

KHWAJA.A.MUNTAQIM, EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN & 17

40.

GENDER JUSTICE IN INDIA 415 (3rd ed., Law Publishers, 2011)

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 X

(B.) Articles and Journals

SL No : ARTICLES AND JOURNALS Page No:

1. Pankaj Kakde, Indian Women: Law and Policy In India, 17

JOURNAL OF CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE Issue 1, 59-76

(2014)

2. Dipak Mishra J., Women Empowerment and Gender Justice, 17

J6 – J26 (2014)

3. N Dharmadan, Will ‘Sabarimala’ Become a ‘Balikeramala’ 22

For Women? KHC J52-J56 (2018)

4. Prof. (Dr) N.R. Madhava Menon, Why Sabarimala Judgment 22

Warrant Review? J7-J10 (2018)

5. Jaclyn L.Neo, Definitional Imbroglios: A Critique Of The 21

Definition Of Religion And Essential Practice Tests In

Religious Freedom Adjudication, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

AND NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW 574-595 (2018)

6. A.B. Princeton, Temples, Courts, and Dynamic Equilibrium in 21

The Indian Constitution, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO 32-98

(2013)

7. Deepa Das, Secularism in The Indian Context, JOURNAL OF 21

AMERICAN BAR FOUNDATION 138-167 (2016)

8. Deepa Das Acevedo, God’s Homes, Men’s Courts, Women’s 20

Right, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS AND NEW YORK

UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW 52-128 (2018)

9. Marc Galanter, Hinduism, Secularism, And The Indian 20

Judiciary, UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS 467-487 (2019)

10. Vindhya Gupta, Cultural and Social Challenges Confronting 17

Women: Their Marginalization and Realities, JOURNAL OF

CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE Issue 1, (2014) pp.01-08

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XI

(C.) Table of Cases

SI CASES CITATION PAGE NO.

NO:

1. A S Naryana Deekshitulu v. State of 1996 (9) S.C.C. 548 6

A.P

2. A.L. Kalra v. P & E Corporation of A.I.R. 1984 S.C. 1361 10

India Ltd

3. Acharya Jagadishwarananda Avadhuta A.I.R. 1984 S.C.R. (1) 20

v. Commr. of Police, Calcutta 447

4. Adi Saiva Sivachariyargal Nata (2016) 2 S.C.C 725 4,5,11

Sangam v. Government of Tamil

Nadu and Anr.

5. Ajay Hasia v. Khalid Mujib A.I.R. 1981 S.C. 487 3

6. Andhra Industrial Works v. Chief A.I.R. 1974 S.C. 1539 1

Controller of Imports.

7. Andhra Pradesh Public Service (2009) 5 S.C.C. 1 10

Commission v. BalojiBadhavath

8. Anuj Garg and Ors. v. Hotel (2008) 3 S.C.C. 1 17

Association of India and Ors.

9. Asha Sharma v. Chandigarh Admin A.I.R. 2011 S.C.W. 10

5636

10. Ashoka Kumar Thakur v. U.O.I (2008) 6 S.C.C. 1 16

11. Baldev Singh v. State of Punjab A.I.R. 2002 S.C. 1124 1

12. Bannari Amman Sugars Ltd. v. CTO (2005) 1 S.C.C. 625 12

13. Bijoe Emmanuel v. State of Kerala A.I.R. 1987 S.C. 748 5,22

14. Bishan Das v. State of Punjab A.I.R. 1961 S.C. 1570 15

15. Budhan Chowdary v. State of Bihar 1955 (1) S.C.R. 1045 10

16. Centre for Public Interest Litigation v. A.I.R. 2016 S.C. 1777 3

U.O.I

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XII

17. Champakam Dorairajan and Ors. v. A.I.R. 1951 Mad. 120 16

The State of Madras

18. Charu Khurana and Ors. v. U.O.I and (2015) 1 S.C.C. 192 17

Ors.

19. Commissioner, Hindu Religious A.I.R. 1954 S.C. 282 5,19,20,22

Endowments, Madras v. Sri

Lakshmindra Thirtha Swamiar of Sri

Shirur Mutt

20. Confederation of Ex- Servicemen A.I.R. 2006 S.C. 2945 15

Associations v. U.O.I.

21. Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam A.I.R. 2012 S.C. 2191 12

and Ors. v. The Election Commission

of India

22. Devarajiah v. Padmanna A.I.R. 1961 Mad. 35 14

23. Dr. Subramanian Swamy v. State of (2014) 5 S.C.C. 75 23

T.N. & Ors

24. Durgah Committee, Ajmer & Anr. v. A.I.R. 1961 S.C. 1402 5,23

Syed Hussain Ali & Ors.

25. Dwarkadas Marfatia & Sons v. Board A.I.R. 1989 S.C. 1642 12

of Trustees, Bombay Port

26. E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu (1974) 4 S.C.C. 3 11

27. EV Chinnaiah v. State of A.P A.I.R. 2005 S.C. 162 11

28. Federal Bank Ltd v. Sagar Thomas (2003) 10 S.C.C 733 4

29. Food Corporation of India v. A.I.R. 1993 S.C. 1601 10

Kamdhenu Cattle Feed Industries

30. Francis Coralie Mullin v. Union A.I.R. 1981 S.C. 746 15

Territory Delhi, Administrator

31. Gopal Das Mohata v U.O.I A.I.R 1955 S.C. 1 1

32. Government of Andra Pradesh v. P.B. A.I.R 1995 S.C. 1648 18

Vijay Kumar

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XIII

33. Government of N.C.T. of Delhi v. (2016) 232 D.L.T. 196 24

U.O.I and Ors.

34. Hindu Religious Endowments v. Sri A.I.R. 1954 S.C. 11,19

LakshmindraThirthaSwamiar of Sri

Shirur Matt

35. In re Thomas A.I.R. 1953 Mad. 21 17

36. Independent Thought v. U.O.I & Ors. A.I.R. 2017 S.C. 4904 11

37. Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) A.I.R. 1986 S.C 515 1

Private Ltd. v. U.O.I

38. Indian Young Lawyers Association 2018 (4) K.L.T. 373 23, 24, 25

and Ors. v. The State of Kerala and

Ors.

39. Indra Sawhney v. U.O.I A.I.R. 1993 S.C. 477 11,10

40. J.K.S.Puttuswamy v. U.O.I (2017) 1 S.C.C. 10 15

41. J.K.S.Puttuswamy v. U.O.I MANU/SC/1054/2018 15

42. Jai Singh v. U.O.I A.I.R 1993 Raj. 177 13,14

43. Janata Dal v. H.S Chowdari (1992) 4 S.C.C. 305 2

44. Javed v. State of Haryana A.I.R. 2003 S.C. 3057 5

45. Jolly George Varghese v. Bank of A.I.R. 1980 S.C. 470 16

Cochin

46. Kathi Raning Rawat v. Saurashtra (1952) S.C.R. 435 16

47. Kedar Nath Bajoria v. State of West A.I.R. 1953 S.C. 404 11

Bengal

48. Kerala v.NM Thomas A.I.R. 1976 S.C. 490 11

49. Kesavananda Bharati v. State of (1973) 4 S.C.C. 225 8

Kerala

50. L.I.C. of India v. Consumer Education A.I.R. 1995 S.C. 1811 12

and Research Centre

51. L.I.C. v. Escorts A.I.R. 1986 S.C. 1370 12

52. Lachhmans v. State of Punjab A.I.R. 1963 S.C. 222 10

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XIV

53. M. Nagaraj v. U.O.I A.I.R. 2007 S.C. 71 10

54. M.S. Bhut Education Trust v. State of A.I.R. 2000 Guj. 160 12

Gujarat

55. M/s. Narinder Chand Hem Raj and A.I.R. 1971 S.C. 2399 8

Ors. v. Lt. Governor, Administrator,

Union Territory, Himachal Pradesh

and Ors.

56. Mahant Jagannath Ramanuj Das v. [1954] S.C.R. 1046 5,11

The State of Orissa

57. Maneka Gandhi v. U.O.I A.I.R. 1978 S.C. 597 14

58. Mohd. Usman v. State of A.P (1971) 2 S.C.C. 188 12

59. Motor General Traders v. State of A.I.R. 1984 S.C. 222 10

Andhra Pradesh

60. N. Adithayan v. Travancore (2002) 8 S.C.C. 106 13

Devaswom Board and Ors

61. Navtej Singh Johar and Ors. v. U.O.I A.I.R. 2018 S.C. 432 24

and Ors

62. New Okhla Industrial Development A.I.R. 2008 S.C. 1983 12

v.Arvind Sonekar

63. Northern Corporation v. U.O.I A.I.R. 1991 S.C 764 1

64. Olga Tellis v. Bombay Corporation A.I.R. 1986 S.C. 180 15

65. Parimal Chakraborty v. State of 2000 (3) G.L.T. 441 10

Meghalaya and Ors

66. Perarula Ramnya Swami v. State of A.I.R. 1972 S.C. 1586 5

Tamil Nadu

67. Prabodh Verma v. State of U.P A.I.R. 1984 S.C. 251 10

68. Raj Pal Sharma v. State of Haryana A.I.R. 1985 S.C. 72 10

69. Raja BiraKishore v. The State of A.I.R. 1964 S.C. 1501 23,24

Orissa

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XV

70. Rajasthan State Electricity Board v. A.I.R 1979 S.C. 131 3

Mohanlal

71. Rajpal Sharma v. State of Haryana A.I.R. 1985 S.C. 1623 12

72. Ram Jankijee Deities v. State of Bihar A.I.R. 1999 S.C.W. 6

1878

73. Ram Narayan Agarwal v. State of U.P A.I.R. 1984 S.C. 1213 16

74. Ram Prasad v. State of Punjab A.I.R. 1966 S.C. 1607 10

75. Rana Muneswar v. State A.I.R. 1976 Pat. 198 22

76. Roop Chand Adlakha v. D.D.A A.I.R. 1989 S.C. 307 10

77. S. Mahendran v. Secretary, A.I.R. 1993 Ker. 42 5,20

Travancore Devaswom Board

78. S.P Gupta and Ors. v. President of A.I.R 1982 S.C. 149 2

India and Ors.

79. S.P Mittal v. U.O.I A.I.R. 1983 S.C. 1 19

80. Sandeep Biswas v. State of West (2010) 2 Cal.W.N. 3

Bengal (Cal) 399

81. Sardar Syadna Taher Saifuddin Saheb A.I.R. 1962 S.C. 853 5,7,20

v. The State of Bombay

82. Sastri Yagnapureesh v. Muldas A.I.R. 1966 S.C. 1119 7

Bhudardas Vaishya

83. Seshammal v. State of Tamil Nadu (1972) 2 S.C.C. 11 6,19

84. Shantabai v. State of Maharashtra A.I.R. 1958 S.C. 531 2

85. Shri Ram Krishna Dalmia v. Shri (1959) S.C.R. 279 11

Justice SR Tendolkar

86. Shri. Balaganesan Metals v. M. N. (1987) 2 S.C.C. 707 13

Shanmukhan Chetti and Ors.

87. Smt. Anjali Roy v. State of West A.I.R. 1952 Cal. 825 16

Bengal

88. Sri Venkataramana Devaru and Ors. v. A.I.R 1958 S.C 255 4,5,6,22

State of Mysore

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XVI

89. State of Bihar v. Kameshwar Singh (1952) 1 S.C.R. 889 23

90. State of Karnataka v. Appa Balu 1995 Supp. (4) S.C.C. 14,17

Ingale 469

91. State of Kerala v. Peoples Union for (2009) 8 S.C.C. 46 10

Civil Liberties, Kerala State Unit

92. State of Madhya Pradesh v. Purachand A.I.R. 1958 M.P. 352 13

93. State of Madhya Pradesh v. Ram A.I.R. 1995 S.C. 1198 13

Krishna Bolathia

94. State of Nagaland v. Ratan Singh A.I.R. 1967 S.C. 212 10

95. State of Punjab v. Ajaib Singh A.I.R. 1953 S.C. 10 10

96. State of Uttar Pradesh v. Jeet S Bisht MANU/SC/7702/2007 9

97. State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali A.I.R. 1952 S.C. 12,10

Sarkar

98. State v. Gulab Singh A.I.R. 1953 All 483 13

99. Subramanian Swamy v. U.O.I and MANU/SC/0621/2016 15

Ors.

100. Sukhdev and Ors v. Bhagat Ram and A.I.R. 1975 S.C. 1331 1

Ors

101. Supreme Court Employees' Welfare (1989) 4 S.C.C. 187 2

Association v. U.O.I and Anr

102. The Durgah Committee, Ajmer v. A.I.R. 1961 S.C. 1402 11

Syed Hussain Ali

103. Tilkayat Shri Govinda/ji Maharaj v. (1964) 1 S.C.R. 561 5,20,22

State of Rajasthan

104. U.O.I and Anr. v. Deoki Nandan A.I.R. 1992 S.C. 96 8

Aggarwal

105. U.O.I v. Prakash P. Hinduja (2003) 6 S.C.C. 195 7

106. U.O.I v. S.B Vohra A.I.R. 2004 S.C. 1402 4

107. Uttam Kumar Samanta v. KIIT 118 (2014) C.L.T. 997 10

University

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XVII

108. V.K. Naswa v. Home Secretary, U.O.I (2012) 2 S.C.C. 542 9

& Ors

109. Vasant Abaji Mandke v. The State of 1979 (81) BomL.R. 542 12

Maharashtra

110. VinodChaturvedi v. State of Madhya A.I.R. 1984 S.C. 814 4

Pradesh

111. Yusuf v. State of Bombay A.I.R. 1954 S.C. 321 11

Foreign Cases

SL CASE CITATION Page

No: No:

1. Dash v. Van Kleeck (1811) 7 Johns 498 7

2 Bilston Corp. v. Wolverhampton Corp. (1942) 2 All E.R. 447 8

3. Sussex Peerage Case (1844) 11 Clark and 15

Finnelly 85

4. Hinds v. R. (1976) 1 All E.R. 353 8

5. Ogden v. Blackledge 2 Cr 276; 7

(D.) Statutes

1. Constitution of India, 1949.

2. Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987.

3. The Civil Rights Act, 1955.

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XVIII

(E.) International Conventions

1. CEDAW- Convention on Elimination of All Forms Discrimination Against

Women

(F.) Reports

4. All India Reporter (A.I.R.)

5. Supreme Court Cases (S.C.C.)

6. Kerala Law Times (K.L.T.)

7. Indian Law Reports (I.L.R.)

8. Supreme Court Journal (S.C.J.)

9. Judgement Today (J.T.)

10. Criminal Law Journal (Cr.L.J.)

11. Supreme Court Record (S.C.R.)

(G.) Dictionaries

1. Black’s Law Dictionary, Bryan .A. Garner, 8th Edition. 2004, West, Thompson

2. Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 5th Edition, 2002, Oxford University Press

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XIX

3.

The Chambers Dictionary, Deluxe Edition 1993, 15th Edition

Reprint,2011,Allied Chambers (India) Pvt Ltd.

4 The Law Lexicon (Ed. Justice Y.Y. Chandrachud), P. Ramanatha Iyer, 2nd

Edition, 2002

5 Wharton’s Law Lexicon, Dr. A. R. Lakshmana J, 15TH Edition 2011,

Universal Law Publishing Co.

(H.) Other Publications

1. CNN IBN

2. Frontline

3. Hindustan Times

4. India Today

5. The Hindu

6. The Wire

7. Times of India

(I.) Online Sources

1. Constitution Society www.Constitution.org

2. Hein Online https://home.heinonline.org/

3. India Kanoon http://indiankanoon.org

4. Jstor https://www.jstor.org/

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XX

5. Lawyers Club India http://www.lawyersclubindia.com/

6. Legal Services India http://www.legalserviceindia.com

7. Lexis Nexis Academia http://www.lexisnexis.com/academica

8. Lex Warrier http://lex warrier.in/

9. Manupatra Online http://www.manupatrafast.in

10. Oxford Dictionary http://www.oxforddictionaries.com

11. SCC Online http://www.scconline.co.in.

12. Westlaw https://www.westlaw.com/

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XXI

STATEMENT OF FACTS

I. BRIEF SKETCH OF HISTORY

The Himaya Temple located in Tenjiku, a city in the Union of Indiana, is one of the few temples

in Tenjiku where devotees of every caste can enter. As per the religious text Tenji was born to

both Shiva and Vishnu. When Tenji fulfils his destiny by killing the demon, a beautiful woman

emerges from the body. Now free, she asks Tenji to marry her. He refuses, explaining to her

that his mission is to go to Tenjiku where he would answer the prayers of his devotees.

However, he assures her, he will marry her when kanni-swamis stop coming. She now sits and

waits for him at a neighbouring shrine near the main temple and is also worshipped as Masma.

II. ISSUE INVOLVED

The temple is prominent for a unique reason — the selective ban imposed on women preventing

them from entering it. Women aged between 10 and 50, that is those who are in menstruating

age, are barred from entering the temple. Although there are numerous Tenji Temple in Indiana,

the Himaya Temple depicts Lord Tenji as a ‘Naistika Brahmcharya’. It is believed that Lord

Tenji’s powers derives from his ascetism, in particular from his being celibate. Celibacy is a

practice adopted by the pilgrims before and during the pilgrimage. The pilgrims have to follow

a strict vow over a period of forty one days, which lays down a set of practice. The custom has

evolved in line with this belief.

III. LEGAL SCENARIO

The Indiana Young Lawyers Association, five women lawyers and a group of women, part of

the "Happy Mensuration" campaign approached the Supreme Court’s seeking a direction to

allow entry of women into the temple without age restrictions and sought the Court's direction

on “menstrual discrimination." The same issue was adjudicated upon by the Tenjiku High

Court in 1991 wherein it was held that the restriction was in accordance with a usage and

custom and hence, not discriminatory. The case is now pending before the seven judge Bench

of this Honourable Court.

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XXII

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

THE PETITIONERS HAVE FILED THIS PETITION UNDER ARTICLE 32 OF THE

CONSTITUTION OF INDIA FOR THE VIOLATION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS

ENUMERATED IN PART III OF THE CONSTITUTION. THE RESPONDENT

MAINTAINS THAT NO VIOLATION OF RIGHTS HAS TAKEN PLACE. THEREFORE,

THIS HON’BLE COURT NEED NOT APPLY ITS JURISDICTION IN THIS PETITION.

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XXIII

STATEMENT OF ISSUES

PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION FILED UNDER ARTICLE 32 OF THE

CONSTITUTION

I. THE PETITIONER AND THE SUBSEQUENT INTERVENERS DO NOT HAVE THE

LOCUS TO FILE THE PRESENT WRIT PETITION

1.1 The Petitioners have the Locus standi but it is flouted

1.2 The Present Petition is not driven by the noble cause of public interest.

1.3 The Petition cannot be filed against the Tenji board as it is not an

instrumentality of State.

II. THE SUPREME COURT HAS LIMITED JURISDICTION IN DEFINING BOUNDARIES OF

RELIGION IN PUBLIC SPACES

2.1 The rationality of religious practices is outside the ken of the Courts

2.2 Hindu Temples are regulated by Agama Shastras

2.3 Religion falls under custom and usage in Article 13

2.4 Separation of Powers and Judicial Overreach

III. THE SAID RESTRICTION IMPOSED ON THE WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF CERTAIN

AGE DOES NOT AMOUNT TO VIOLATION OF THEIR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS IN LIGHT

OF RULE 3(b) OF TENJIKU HINDU PLACES OF PUBLIC WORSHIP (AUTHORIZATION

OF ENTRY) RULES.

3.1 The restriction imposed on the women and children of certain age does not

amount to violation of Article 14 of the Constitution

3.1.1. The twin test principle is satisfied in the present case

3.1.2. Test of of arbitrariness

3.2 Article 15 of the Constitution has not been violated

3.3 The said restriction does not violate Article 17 of the Constitution.

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XXIV

3.4 Article 21 of the Constitution has not been violated.

IV. THE PRACTICE OF EXCLUDING SUCH WOMEN CONSTITUTE AN ‘ESSENTIAL

RELIGIOUS PRACTICE’ UNDER ARTICLE 25 AND A RELIGIOUS INSTITUTION CAN

ASSERT A CLAIM IN THAT REGARD UNDER THE UMBRELLA OF RIGHT TO MANAGE

ITS OWN AFFAIRS IN THE MATTERS OF RELIGION.

4.1 The practice of selective exclusion of women is an ‘essential religious

practice’ protected under Article 25 of the Constitution.

4.1.1 Test of essential religious practices – what can be classified as

essential or not.

4.1.2 Power or authority to decide what is an essential religious

practice

4.2 The right of a religious institution to manage its affairs in the matters of

religion will prevail in the instant case.

4.2.1 Characteristics of a religious denomination can be witnessed

4.2.2 The said practice is not against ‘public morality’.

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XXV

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENTS

PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION PETITION UNDER ARTICLE 32 OF THE

CONSTITUTION

I. THE PETITIONER AND THE SUBSEQUENT INTERVENERS DO NOT HAVE THE

LOCUS TO FILE THE PRESENT WRIT PETITION

Public interest litigation has been filed by the Petitioners and subsequent interveners under

Art. 32 of the Constitution of Indiana. The locus standi of the Petitioners is flouted due to the

existence of personal gain. The Tenji Board cannot be considered an instrumentality of State

under Art. 12 of the Constitution as it is not an authority which performs public functions.

II. THE SUPREME COURT HAS LIMITED JURISDICTION IN DEFINING BOUNDARIES OF

RELIGION IN PUBLIC SPACES

Traditions and beliefs underlying such religion/practice have to be analyzed. Though there

exists an inherent judicial power in the Court to determine essential religious practices, such

exercise must always be restricted and restrained. When judicial activism crosses its limits, it

results in ‘Judicial Overreach’.

III. THE SAID RESTRICTION IMPOSED ON THE WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF CERTAIN

AGE DOES NOT AMOUNT TO VIOLATION OF THEIR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS IN

LIGHT OF RULE 3(b) OF TENJIKU HINDU PLACES OF PUBLIC WORSHIP

(AUTHORIZATION OF ENTRY) RULES.

The differentia for classification by the impugned Rule is on a rational basis, has reasonable

nexus to the object sought and does not suffer from the vice of arbitrariness. Thus, it is not

violative of Art. 14 of the Constitution. Article 15(2) is not violated as temples do not come

within the ambit of the term place of public resort. Also, no rule has been formulated

by the State for making special provisions for women and children, thus, rendering Article

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 XXVI

15(3) inapplicable.

There has been no violation of Article 17 as the rights of untouchables cannot be used in

reference with the right of entry of women. Such an analogy is misconceived and sustainable.

The State has neither enacted any law nor is there a legitimate State aim. The Tenji Board is

not a State entity and their rules cannot be violative of Art. 21 of the Constitution.

IV. THE PRACTICE OF EXCLUDING SUCH WOMEN CONSTITUTE AN ‘ESSENTIAL

RELIGIOUS PRACTICE’ UNDER ARTICLE 25 AND A RELIGIOUS INSTITUTION CAN

ASSERT A CLAIM IN THAT REGARD UNDER THE UMBRELLA OF RIGHT TO

MANAGE ITS OWN AFFAIRS IN THE MATTERS OF RELIGION.

The practice of selective exclusion of women is an ‘essential practice’ protected under Art. 25

of the Constitution for it is a part of religion. Moreover, devotees of Lord Tenji can be said to

constitute a separate religious denomination under Art. 26 and have a right to manage their

own affairs. The given custom which prohibits women is in no sense against public morality.

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 1

ARGUMENTS ADVANCED

PUBLIC INTEREST LITIGATION FILED UNDER ARTICLE 32 OF THE

CONSTITUION OF INDIANA

I. THE PETITIONER AND THE SUBSEQUENT INTERVENERS DO NOT HAVE THE LOCUS

TO FILE THE PRESENT WRIT PETITION

“If I was asked to name any particular Article in the Constitution as most important…. An

Article without which the Constitution would be a nullity- I could not refer, to any other Article

except this one. It is the very soul of the Constitution and the very heart of it.”1

It is humbly submitted before the Hon’ble Court that the petition is not maintainable under

Art.322 of the Constitution, as the Petitioners do not have locus standi and there is no violation

of fundamental rights. The sole object of Art. 32 is the enforcement of the fundamental rights

guaranteed by the Constitution3 but whatever other remedies may be open to an aggrieved

person, he has no right to complain under Art. 32 if no fundamental right has been infringed.4

Furthermore, the Judiciary can neither enforce the violation of Part III against a non- state entity

nor can it issue writs/directions5 based on the same6. Hence, the petition will not be

maintainable.

1.1 The Petitioners have the Locus standi but it is flouted

A Public interest litigation can be filed against the State for the violation of fundamental rights7

under Art. 328. In Northern Corporation v. U.O.I9 and Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay)

Private Ltd. v. U.O.I10, it was held that for invoking Art.32, there must be a clear breach of

1

Constituent Assembly Debates Volume III Page 953.

2

Gopal Das Mohata v. U.O.I., A.I.R. 1955 S.C. 1 (India).

3

ARVIND P. DATAR, COMMENTARY ON THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA 53 (2 nd ed., Lexis Nexis

Butterworths Wadhwa 2007).

4

Baldev Singh v. State of Punjab, A.I.R. 2002 S.C. 1124 (India).

5

ABHISHEK ATREY, LAW OF WRITS PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE 71 (1st ed., Kamal Publishers, 2004).

6

V.G. RAMACHANDRAN, LAW OF WRITS 253 (1st ed., Eastern Book Company 2007).

7

Sukhdev and Ors. v. Bhagat Ram and Ors., A.I.R. 1975 S.C. 1331 (India).

8

Andhra Industrial Works v. Chief Controller of Imports, A.I.R. 1974 S.C. 1539 (India).

9

Northern Corporation v. U.O.I., A.I.R. 1991 S.C. 764 (India).

10

Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) Private Ltd. v. U.O.I., A.I.R. 1986 S.C. 515 (India).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 2

fundamental right11 along with the requisite locus standi.12 Nevertheless, the traditional rule of

locus standi in a Public interest litigation is that a Non-Governmental Organization can file it,13

but further needs to prove that the petition is being filed on behalf of a group of people who

are incapable of protecting themselves. In the Judges Transfer case14, J. Bhagwati stated that:

Where a legal wrong or legal injury is caused to a person or a determinate

class of people by a reason of violation of any constitutional or legal rights

and such person or determinate class of people is by reason of poverty,

helplessness of disability or socially or economically disadvantaged position

unable to approach the Court for relief.15

In the present case, the women community does not belong to any of the classes

aforementioned.16 This petition needs to be considered as an abuse of Public interest litigation

as it amounts to the misuse of liberal rule of locus standi.17 In the light of the aforementioned

reason, it is submitted that the non-governmental organization’s locus standi is flouted.

1.2 The Present Petition is not driven by the noble cause of public interest

The subsequent interveners do not have the locus standi due to the existence of personal gain.

The five women lawyers and women forming part of the ‘Happy Mensuration’ campaign have

filed the petition in pursuance of their right to enter the temple.18 This is an abuse of the concept

of Public interest litigation as reiterated by J. Bhagwati:

It should be carefully analysed who approaches the Court in case of a PIL is

acting bona fide and not for personal gain or private profit or political or other

oblique consideration. The Court must not allow its process to be abused by

any.19

The present petition is to be considered as an act to garner sufficient publicity. According to

the reports published by the Centre for Public Interest Litigation, a strong rise has been noticed

11

V.N SUKLA, CONSTITUTION OF INDIA 324 (12th ed., Eastern Book Company 2016).

12

Shantabai v. State of Maharashtra, A.I.R. 1958 S.C. 531 (India).

13

Supreme Court Employees' Welfare Association v. U.O.I. and Anr., (1989) 4 S.C.C. 187 (India).

14

Id. at 13.

15

S.P. Gupta and Ors. v. President of India and Ors., A.I.R. 1982 S.C. 149; Janata Dal v. H.S Chowdari, (1992)

4 S.C.C. 305 (India).

16

KARLE PEREZ PORTILLA, REDRESSING EVERYDAY DISCRIMINATION- THE WEAKNESS AND

POTENTIAL OF ANTI-DISCRIMINATION LAW 67 (1st ed., CPI Group Ltd, Croydon 2016).

17

APPENDIX 1.

18

Moot Proposition ¶ 5.

19

J. N PANDEY, CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF INDIA 408 (52 nd ed., Central Law Agency 2015).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 3

in the number of petitions filed by NGOs in order to gain a fake reputation and name.20 The

Apex Court has vehemently held that all such petitions which are filed on the basis of publicity

or for personal gains shall be dismissed.21 Therefore, the present petition should stand

dismissed because of the nature of it being a publicity stunt.

1.3 The petition cannot be filed against the Tenji board as it is not an

instrumentality of State

The Tenji board in the instant matter cannot be considered as an instrumentality of State under

Art. 1222. The term ‘State’ occurring in Art. 13(2), or any other provision concerning

fundamental rights, has an expansive meaning23, i.e.:

(a) The Government and Parliament of India.

(b) The Government and the Legislature of a State.

(c) All local authorities; and

(d) Other authorities within the territory of India, or under the control of the

Central Government.24

To determine the ambit of the institutions falling under ‘other authorities’, a six-point test has

been laid down. Whether a body is an instrumentality of the Government or not will depend on

the types of functions performed by it, among other factors25:

(e) The functions performed by the corporation is also an indication of the

corporation being an instrumentality of the state, that is if the corporation

performs public functions or closely related to government functions, it

would be considered an instrumentality of the state.26

In the present case, the board is not an authority which performs public functions. A Public

function can be defined as any function/ activity carried on with respect to public places.27 It is

contended that though the Tenji Board maintains the temple, as long as the temple is not a

public place,28 any function performed in this aspect cannot be considered as a public function.

It is to be noted that ‘temples’ were consciously deleted from draft Indian Constitution since

20

APPENDIX 2.

21

Centre for Public Interest Litigation v. U.O.I., A.I.R. 2016 S.C. 1777 (India).

22

INDIAN CONST. art.12.

23

Rajasthan State Electricity Board v. Mohanlal A.I.R. 1979 S.C. 131 (India).

24

THE OXFORD HANDBOOK OF INDIAN CONSTITUTION 68 (1st Oxford University Press 2016).

25

Ajay Hasia v. Khalid Mujib, A.I.R. 1981 S.C. 487, Sandeep v. State of W.B, (2010) 2 Cal W.N. 399 (India).

26

KAILASH RAI, CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF INDIA 177(11 th ed., Central Law Publications 2015).

27

Federal Bank Ltd v. Sagar Thomas, (2003) 10 S.C.C. 733 (India).

28

Id. at 27.

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 4

the Constituent Assembly did not consider it fit to include temples along with places of public

worship29. Disregard of this legislative intent will result in an apparent error.30 Therefore, it

can be safely concluded that the Tenji Board is not a State entity under Art. 12.31

Under Art. 32, fundamental rights violation can be invoked only against a State or State entity32

and as long as Tenji Board is not incorporated under Art. 12, no writ can be enforced against

it.33

Therefore, it is humbly submitted that the Public interest litigation is not maintainable.

II. THE SUPREME COURT HAS LIMITED JURISDICTION IN DEFINING BOUNDARIES OF

RELIGION IN PUBLIC SPACES

It is humbly submitted that the Hon’ble Supreme Court has limited jurisdiction in defining the

boundaries of religion in public spaces. The arguments presented are three-fold in nature:

2.1 The rationality of religious practices is outside the ken of the Courts

Art. 25 of the Constitution34 declares the right of the individual to freedom of religion 35 while

Art. 2636 protects the exercise thereof. There exists no rigid, fixed or mechanical definition of

the word religion.37 Persons are given the fullest freedom to hold genuine beliefs.38

Furthermore, freedom of religion is not only confined to conscientious beliefs but also extends

to outward acts such as religious practices.39

A practice is deemed religious if it is regarded as an essential part of the religion.40 The

jurisdiction in applying the ‘essential and integral practice test’ in religious matters is vested in

29

Vol. No. VII, Constituent Assembly Debates, Amendment No. 301 p. 650-664.

30

T.K.VISWANATHAN, LEGISLATIVE DRAFTING- SHAPING THE LAW FOR THE NEW MILLENNIUM

(1st ed., Indian Law Institute New Delhi 2007).

31

ARTICLE 12, supra note 21.

32

Vinod Chaturvedi v. State of Madhya Pradesh, A.I.R. 1984 S.C. 814 (India).

33

U.O.I v. S.B. Vohra, A.I.R. 2004 S.C. 1402(India).

34

INDIAN CONST. art. 25.

35

Sri Venkataramana Devaru and Ors. v. State of Mysore, A.I.R. 1958 S.C. 255 (India).

36

INDIAN CONST. art. 26.

37

Adi Saiva Sivachariyargal Nata Sangam v. Government of Tamil Nadu and Anr., (2016) 2 S.C.C. 725 (India).

38

ERIC BARENDT, FREEDOM OF SPEECH 45 (2nded., Oxford University Press 2007).

39

Mahant Jagannath Ramanuj Das v. The State of Orissa, [1954] S.C.R. 1046; Sri Venkataramanav Devaru v.

State of Mysore, [1958] S.C.R. 895; Durgah Committee, Ajmer v. Syed Hussain Ali, [1962] 1 S.C.R., 383 (India).

40

Javed v. State of Haryana, A.I.R. 2003 S.C. 3057 (India).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 5

Court.41 If beliefs are sincerely held and responsibly professed, they are bound to be protected

by the Courts.42 The object of the test is to limit the scope of State’s interference with

religion.4344

Though there exists an inherent judicial power in the Court to determine essential religious

practices, such exercise must always be restricted and restrained as laid down in Adi Saiva

Sivachariyargal Nata Sangam v. Government of Tamil Nadu and Anr.45 When there arises a

necessity to determine the essential religious practice, then the Supreme Court has to

dispassionately examine the origins and basis of the religious practice46 by examining the

relevant scriptures, historical considerations47 and seek inputs from the Chief priest of the

Temple48 as has been laid down in Sardar Syadna TaherSaifuddin Saheb v. The State of

Bombay.49

Thus, the tradition and the beliefs underlying such religion/practice have to be analyzed.50 It is

not for the Courts to determine which of these practices of faith are to be struck down except

if they are pernicious, oppressive or a social evil. The Courts cannot straight away apply the

‘impact theory’ in religious matters. It would only lead to homogenization of religious places

of worship and killing their very identities in the process. The theory is indifferent to the rights

of stakeholders such as the Deity, the Temple and devotees. It is also precisely for this reason

that the legislature has not been given the power to alter religious practices under Art. 25(2),

since it only speaks of social reform or welfare. 51

The Supreme Court has limited jurisdiction in defining the boundaries of religion in public

spaces. The belief/ practice should be upheld at most times and judicial restraint should be

exercised in interfering in religious matters. Judicial review of religious practices ought not to

be undertaken as it imposes morality, or rationality with respect to the form of worship of a

41

DD BASU COMMENTARY ON THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA 680 (9 thedn., LEXIS NEXIS 2016)

42

Bijoi Emmanuel v. State of Kerala, A.I.R. 1987 S.C. 748 (India).

43

Perarula Ramnya Swami v. State of Tamil Nadu, A.I.R. 1972 S.C. 1586(India).

44

IQBAL NARAIN , SECULARISM IN INDIA (1st ed., Classic Publishing Book House 1995).

45

Adi Saiva Sivachariyargal, supra note 37.

46

Commr., H.R.E, Madras v. Sri Lakshmindra Swamiar of Sri Shirur Mutt, 1954 S.C.R. 1005 (India).

47

Tilkayat Shri Govinda/ji Maharaj v. State of Rajasthan (1964) 1 S.C.R. 561(India).

48

BS MURTHY, SECULARISM , RELIGION AND LIBERAL DEMOCRACY (1 st ed., Andhra Univ. 1997).

49

Sardar Syadna Taher Saifuddin Saheb v. The State of Bombay, A.I.R. 1962 S.C. 853(India).

50

S. Mahendran v. Secretary, Travancore Devaswom Board, A.I.R. 1993 Ker 42 (India).

51

RONJOY SEN, ARTICLES OF FAITH RELIGION,SECULARISM AND THE INDIAN SUPREME COURT

43(4th ed., Oxford India Publishing House, 2014).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 6

deity. If any practice can be traced to antiquity and is integral, then it must be taken as to be an

essential religious practice of that temple and courts should not interfere in it. The rationality

of the Courts is thus, outside the ken of the Courts.

2.2. Hindu Temples are regulated by Agama Shastras

The right recognized by Art. 25(2)(b) of the Constitution52 necessarily becomes subject to some

limitations or regulations and these limitations arise in the process of harmonizing the rights

conferred by Art. 25(2)(b) with that protected by Art. 26(b).53

In this regard, in the instant case, the judgement of the Tenjiku High Court in 1991 assumes

relevance where ‘The Himaya Thantri’ asserted that these customs and usages had to be

followed for the welfare of the temple. Only followers of penance and custom are eligible to

enter the temple.54 Thus, the sole reason for the restriction placed on the entry of women with

reproductive capabilities in the Tenji Temple is directly traceable to the custom.

The worship in Hindu temples is regulated in strict accordance with the rules laid down in the

Agama Sastras. The primacy of the Agama Shastras was observed by the Hon'ble Supreme

Court in Seshammal v. State of Tamil Nadu.55 The Apex Court had discussed in detail the

significance of Agama Shastras which apply to the religious aspects of a Temple.

The institution of temple worship has an ancient history. With the construction of temples, the

institution of Archakas also came into existence, the Archakas being professional men who

made their livelihood by attending on the images.56 Treatises on rituals were compiled and they

are known as Agamas. 57

The authority of these Agamas is recognized in Sri Venkataramana Devaru v. The State of

Mysore.58 Agamas are described as treatises of ceremonial law dealing with the construction of

temples, installation of idols therein and conduct of the worship of the deity. Rules with regard

to daily and periodical worship have been laid down for securing the continuance of the Divine

Spirit. According to the Agamas, a Deity becomes defiled if there is any departure or violation

52

INDIAN CONST. art. 25.

53

Sastri Yagnapureesh v. Muldas Bhudardas Vaishya, A.I.R. 1966 S.C. 1119 (India).

54

Moot Proposition, ¶ 8.

55

Seshammal v. State of Tamil Nadu, A.I.R. 1972 S.C. 1586 (India).

56

B.M. GANDHI, HINDU LAW 64 (4th ed., Eastern Book Co., 2016).

57

B.S. CHAUHAN, TREATISE ON HINDU LAW & USAGE, 834 (17th ed., Bharat Law House 2017)

58

Devaru, supra note 34.

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 7

of any of the rules relating to worship.59

In A S Naryana Deekshitulu v. State of A.P.60, held that:

The institution of the temple should be in conformity with the Agamas co-

existing with the institution of temple worship. Construction of the temple

and the institution of Archakas simultaneously came into existence. The

temples are constructed according to the Agama Shastra.61

Furthermore, in Sardar Syadna Taher Saifuddin Saheb v. The State of Bombay62, this Court

held that the reformative levers provided in the Constitution cannot be used to reform a

religious or a religious institution out of its identity and the State must be careful in applying

its notions of equality and modernity to religious institutions. Therefore, the ancient history of

the Himaya Temple in the case at hand should be preserved.

2.3 Religion falls under custom and usage in Article 13

Religious practices and traditions which apply to public places of worship, as distinguished

from personal laws based on religion, fall under custom and usage as used in Art.1363 of the

Constitution.64 Parliament exercises sovereign power to enact laws65 and Courts have to

interpret these laws. To declare what the law is or has been is judicial power; to declare what

law shall be is legislative.66

In M/s. Narinder Chand Hem Raj and Ors. v. Lt. Governor, Administrator, Union Territory,

Himachal Pradesh and Ors.,67 it was held that legislative power can be exercised only by the

legislature and its delegate and none else. In U.O.I and Anr. v. Deoki Nandan Aggarwal,68 the

Court observed that the power to legislate has not been conferred on the Court.

The Legislature has to regulate any activity related to customs and usages by formulating laws.

For instance, Sati, an obsolete and evil funeral custom, was banned by way of legislation i.e.

59

Ram Jankijee Deities v. State of Bihar 1999 A.I.R. S.C.W. 1878 (India).

60

A S Naryana Deekshitulu v. State of A.P., 1996 (9) S.C.C. 548 (India).

61

MULLA, HINDU LAW 224 (9th ed., Lexis Nexis, 1999).

62

Sardar Syadna , supra note 49.

63

INDIAN CONST. art.13 cl 1.

64

RAJEEV BHARGAVA, SECULARISM AND ITS CRITICS 191 (2 nd ed., Oxford University Press 2007).

65

U.O.I. v. Prakash P. Hinduja, (2003) 6 S.C.C. 195 (India).

66

Ogden v. Blackledge, 2 Cr 276; Dash v. Van Kleeck, (1811) 7 Johns 498 (Foreign).

67

M/s. Narinder Chand and Ors. v. Lt. Governor, Administrator, H.P and Ors., A.I.R. 1971 S.C. 2399 (India).

68

U.O.I. and Anr. v. Deoki Nandan Aggarwal, A.I.R. 1992 S.C. 96 (India).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 8

Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987. In the present matter, the Judiciary cannot play a role in deciding

on the custom as it has a force of law under Art.13 and only the Legislature can enact or amend

the law. 69

If the instant issue pending before a seven-judge bench of the Hon’ble Supreme Court of

Indiana,70 decides on the custom, it shall be binding on all the lower Courts/Benches of the

Supreme Court under Art. 141 of the Constitution. It will be quite an arduous task to constitute

a larger bench in the future to decide on similar religious matters. The subsequent decisions by

other lower or co-ordinate Benches will render the decision of the seven-judge Bench as per

incuriam, and will be liable to be ignored by other subsequent Benches.71

2.4 Separation of Powers and Judicial Overreach

When judicial activism crosses its limits, it results in ‘Judicial Overreach’. When the judiciary

oversteps the powers given to it, it may interfere with the proper functioning of the legislative

or executive organs of government. This is contrary to the Doctrine of Separation of Powers

which is a constituent of the basic structure of Indian Constitution.72

In the case at hand, the petition fails to distinguish between diversity in religious traditions and

discrimination.73 The aspect of discrimination in the petition has the potential of causing

irreparable harm to the religious rights protected under Art. 25 and 26 of the Constitution. In

Arguendo, even if the practice is not an essential and integral part of the belief concerned, the

Court can neither legislate nor issue a direction to the Legislature to enact in a particular

manner.74It is for the democratically elected Legislature to determine what would be for the

benefit of the society and the well-being of its members and, public policy.75

Moreover, if a Court were to dictate what is or is not in public interest, it would be usurping

the functions of the Legislature.76 In State of Uttar Pradesh v. Jeet S Bisht77, Markandey Katju

J. observed that:

69

MONA SHUKLA, INDIAN JUDICIARY AND GOOD GOVERNANCE 67 (1st ed., Regal Publications 2011).

70

Moot Proposition, ¶ 8.

71

ARUN SHOURIE, COURTS AND THEIR JUDGEMENTS 72 (2 nd ed., Rupa and Co. 2002).

72

Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala, (1973) 4 S.C.C. 225 (India).

73

Moot Proposition, ¶ 6.

74

V.K. Naswa v. Home Secretary, U.O.I & Ors. (2012) 2 S.C.C. 542 (India).

75

Bilston Corp. v. Wolverhampton Corp., (1942) 2 All E.R. 447 (451) (Foreign).

76

Hinds v. R., (1976) 1 All E.R. 353 (370) (PC) (Foreign).

77

State of Uttar Pradesh v. Jeet S Bisht, MANU/SC/7702/2007 (India).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 9

After all, it is only these two organs78 of the state that is responsible for

framing and implementing policies for the public good and the judiciary’s

role is to prevent any transgression in respect of Constitutional breach and

fundamental rights. The judiciary must exercise self-restraint and eschew the

temptation to encroach into the domain of the legislature.79

In this backdrop, it is worth emphasizing that according to the theory of separation of powers,

the judiciary cannot exercise its powers in domain of the executive and the legislature.80

Therefore, the Supreme Court has limited jurisdiction in defining boundaries of religion in

public spaces.

III. THE SAID RESTRICTION IMPOSED ON THE WOMEN AND CHILDREN OF CERTAIN

AGE DOES NOT AMOUNT TO VIOLATION OF THEIR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS IN LIGHT

OF RULE 3(b) OF TENJIKU HINDU PLACES OF PUBLIC WORSHIP (AUTHORIZATION

OF ENTRY) RULES?

It is humbly submitted that the said restriction imposed on the women and children of a certain

age does not amount to violation of their fundamental rights under Articles 14, 15, 17 and 21

in light of Rule 3(b) of Tenjiku Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorization of Entry)

Rules.81

3.1 The restriction imposed on the women and children of certain age does not amount

to violation of Article 14 of the Constitution

Art. 14 of the Constitution guarantees the right to equality to every person of India82 and

prohibits discrimination.83 It confers on all people equality before law and equal protection of

law.84 The doctrine of equality before law is a necessary corollary of Rule of Law 85 which

pervades the Indian Constitution.86 If a law is arbitrary or irrational, it would fall foul of Art.14

which prohibits class legislation and not reasonable classification for the purpose of

78

V.KRISHNA ANANTH, THE INDIAN CONSTITUTION AND SOCIAL REVOLUTION 63 (16 th ed., Sage

India1900).

79

N.S.BINDRA, INTERPRETATION OF STATUTES 65 (10 th ed., Lexis Nexis 2008).

80

C.K.TAKWANI, LECTURES ON ADMINISTRATIVE LAW (1 st ed., Lexis Nexis 2008).

81

The Tenjiku Hindu Places of Public Worship (Authorization of Entry) Rules, Rule 3: (b) Women at such time

during which they are not by custom and usage allowed to enter a place of public worship.

82

Thommen,J., in IndraSwahney v. U.O.I, A.I.R. 1993 S.C. 477 (India).

83

DR.J.N.PANDEY, CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF INDIA 237 (51 st, Central Law Agency 2018).

84

M.Nagaraj v. U.O.I., A.I.R. 2007 S.C. 71 (India).

85

Food Corporation of India v. Kamdhenu Cattle Feed Industries, A.I.R. 1993 S.C. 1601; Asha Sharma v.

Chandigarh Admin., 2011 A.I.R. S.C.W. 5636.

86

Andhra Pradesh Public Service Commission v. Baloji Badhavath, (2009) 5 S.C.C. 1 (India).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 10

legislation.87 The principle of equality enshrined in Art. 14 is a basic feature of the Constitution

and88to consider that Art.14 is not violated it is necessary to check arbitrariness along with the

twin test principles.89

3.1.1. The twin test principle is satisfied in the present case

This principle propounds that any classification should satisfy the test of reasonable

classification by fulfilling the following two conditions90-

(1) The classification must be founded on an intelligible differentia which

distinguishes persons or things that are grouped together from others left

out from the group91and,

(2) Secondly, there should be some rational nexus relation to the object

sought to be achieved by the Act.92

A classification may properly be made on geographical93 or territorial basis or on historical

considerations94 if that is germane to the purposes.95 The classification in the present case finds

its basis in the location of the said Tenji temple as distinct from the temples of Lord Tenji in

other parts of the state. Moreover, the historical background has been illustrated through the

depiction of the Lord as a ‘Naishtika Brahmachari’ or an eternal celibate. It is to preserve this

characteristic that the customs regarding the exclusion of women in procreative age group have

been established.96 Most importantly, a classification need not be scientifically perfect or

logically complete.97

87

Budhan Chowdary v. State of Bihar, 1955 (1) S.C.R. 1045 (India).

88

State of Kerala v. Peoples Union for Civil Liberties, Kerala State Unit, (2009) 8 S.C.C. 46 (India).

89

A.L. Kalra v. P & E Corporation of India Ltd., A.I.R. 1984 S.C. 1361 (India).

90

Parimal Chakraborty v. State of Meghalaya and Ors., 2000 (3) G.L.T. 441;Uttam Kumar Samanta v. KIIT

University, 118 (2014) C.L.T. 997 (India).

91

State of W.B v. Anwar Ali, A.I.R. 1952 S.C. 75, Motor Traders v. State of A.P , A.I.R.1984 S.C. 222.

92

Roop Chand Adlakha v. D.D.A., A.I.R. 1989 S.C. 307(India).

93

State of Punjab v. Ajaib Singh, A.I.R. 1953 S.C. 10 (India).

94

Lachhmans v. State of Punjab, A.I.R. 1963 S.C.222; Ram Prasad v. State of Punjab, A.I.R. 1966 S.C. 1607

(India).

95

State of Nagaland v. Ratan Singh, A.I.R. 1967 S.C. 212 (India).

96

Moot Proposition, ¶ 3.

97

Kedar Nath Bajoria v. State of West Bengal, A.I.R. 1953 S.C. 404 (India).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 11

Equal protection is not violated if the exception made is required by some other provision of

the Constitution.98 The protection under Articles 25 and 26 extends a guarantee for rituals and

observances, ceremonies and modes of worship99 which are integral parts of a religion.100 Thus,

both the fundamental rights need to be harmonized. The given custom in the instant case is

protected under the Constitution within the ambit of right to religion and there is nothing in the

custom which demands a social reform or contravenes with public order, morality or health.101

The Rule has rightly considered this scenario, and the classification envisaged is reasonable

and founded on rational reasons.

Furthermore, there is no constitutional or legal bar to reasonably differentiate between two sets

of groups/classes.102 Sub-classification, which is rational, relevant, based on intelligible

differentia, and with a nexus between the differentia and the object to be achieved is allowed.103

Thus, Art.14 does not forbid reasonable sub-classification. In the instant matter, there is no

restriction between two sections or between two classes amongst Hindus in the matter of entry

to a temple whereas the restriction is only in respect of women of a particular age group and

not women as a class.

Secondly, a rational nexus exists in the present case as the classification is solely for the

purpose of safeguarding the custom of exclusion of women within the age group of 10 to 50

years to preserve the belief that Lord Tenji exists in a celibate form.

The validity of a rule has to be judged by assessing its overall effect and not by picking up

exceptional cases.104 All aspects need to be taken into consideration while making a

classification. Taking all the factors into consideration in the present scenario, the historical

report, religious texts, beliefs, biological factors and other relevant matters, it can be asserted

that there has been no violation of Art.14 by the Tenji Board.

98

Independent Thought v. U.O.I and Ors., A.I.R. 2017 S.C. 4904; Yusuf v. State of Bombay, A.I.R. 1954 S.C.

321 (India).

99

Adi Saiva Sivachariyargal, supra note 37.

100

H.R.E v. Sri Swamiar of Sri Shirur Matt, A.I.R. 1954 S.C. 282; Mahant Sri Jagannath Ramanuj Das v. The

State of Orissa 1954 S.C.R. 1046; Durgah Commi., Ajmer v. Syed Hussain Ali, A.I.R. 1961 S.C. 1402 (India).

101

P. ISHWARA BHATT, FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS - A STUDY OF THEIR INTER-RELATIONSHIP 603

(2nd ed., Eastern Law House 2004).

102

EV Chinnaiah v. State of A.P., A.I.R. 2005 S.C. 162; Indra Sawhney v. U.O.I, A.I.R. 1993 S.C. 477; Kerala v.

NM Thomas, A.I.R. 1976 S.C. 490 (India).

103

Shri Ram Krishna Dalmia v. Shri Justice SR Tendolkar, (1959) S.C.R. 279; E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil

Nadu, (1974) 4 S.C.C. 3 (India).

104

Mohd. Usman v. State of A.P., (1971) 2 S.C.C. 188 (India).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 12

3.1.2. Test of arbitrariness

Every State action must be informed by reason and guided by public interest.105 It follows that

an act uninformed by reason is per se arbitrary.106The classification for achieving specific ends

should not be arbitrary, artificial or evasive. It should be based on an intelligible differentia,

some real and substantial distinction, which distinguishes persons or things grouped together

in the class from others left out of it.107

In the case at hand, the practices, traditions and customs of the Tenji Temple in Tenjiku are

based on the celibate nature of the deity. There exist temples of similar nature where restrictions

exist on men with respect to their entry and participation in festivals celebrating Female

Deities.108 The instant differentiation of women in the age of 10 to 50 years is in relation to the

aforesaid reason. The sub-classification is not arbitrary and has a rational nexus with respect to

the object sought to be achieved.109

3.2 Article 15 of the Constitution has not been violated

The law laid down under this Article is an anti-discriminative110law that prevents any

discrimination on the part of the State on the basis of religion, race, caste, sex, place of birth or

any of them.111 The judgment in Kathi Raning Rawat,112 gives a clear picture in extrapolating

the real sense of discrimination in which it was observed that ‘Discrimination thus involves an

element of unfavorable bias in any public place and it is in that sense that the expression has to

be understood in this context.’113

Any discrimination which is based solely on the grounds that a person belongs to a particular

race or caste or professes a particular religion or was born at a particular place or is of a

105

Dwarkadas Marfatia & Sons v. Board of Trustees, Bombay Port, A.I.R. 1989 S.C. 1642; L.I.C. v. Escorts,

A.I.R. 1986 S.C. 1370; L.I.C. of India v. Consumer Education and Research Centre, A.I.R. 1995 S.C. 1811; M.S.

Bhut Education Trust v. State of Gujarat, A.I.R. 2000 Guj. 160 (India).

106

Bannari Amman Sugars Ltd. v. CTO, (2005) 1 S.C.C. 625 (India).

107

Vasant Abaji Mandke v. The State of Maharashtra,1979 (81) BomLR 542 (India).

108

APPENDIX 3.

109

Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam and Ors. v. The Election Commission of India, A.I.R. 2012 S.C. 2191;

State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar, A.I.R. 1952 S.C.; New Okhla Industrial Development v. Arvind

Sonekar, A.I.R. 2008 S.C. 1983; Rajpal Sharma v. State of Haryana, A.I.R. 1985 S.C. 1623 (India).

110

Ashoka Kumar Thakur v. U.O.I, (2008) 6 S.C.C. 1 (India).

111

INDIAN CONST. art. 15 , cl.1.

112

KathiRaningRawatv.Saurashtra (1952) S.C.R. 435 (India).

113

B.RAMASWAMYHUMAN RIGHTS OF WOMEN 85 (1st ed., Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. 2002).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 13

particular sex and on no other ground is a violation of Art. 15 unless it is based on one or more

of these grounds and also on other grounds is not hit by the Article. 114 The significance of the

word ‘only’ in Art.15 is that, other qualifications being equal the race, religion etc. of a citizen

shall not be a ground of preference of disability.115 Additionally, in Anuj Garg and Ors. v.

Hotel Association of India and Ors.116 and Charu Khurana and Ors. v. U.O.I and Ors.,117 the

Court held that gender bias alone in any form is opposed to the constitutional norms.

Art. 15 (2) prohibit subjection of a citizen to any disability, liability, restriction or condition on

grounds only of religion, race, caste, sex or place of birth with regards to-

(a) access to shops, public restaurants, hotels and palaces of public

entertainment; or

(b) the use of wells, tanks, bathing Ghats, roads and places of public resort

maintained wholly or partly out of State funds or dedicated to the use of

the general public.118

And, Article 15(3) does not prevent the State from making any special provision for women

and children respectively.119

A challenge to a law on the ground that it violated Art.15 or any other Article must be pleaded

and proved to succeed, if a person fails to establish a right he will fail to establish a violation

of fundamental right.120 Without the infringement of a right, there cannot be a violation of Art.

15.121

Temples were consciously deleted from draft Art. 9 (Art.15 of Indian Constitution) since the

Constituent Assembly did not consider it fit to include temples along with places of public

resort where no citizens are subject to discrimination on the basis of the prohibited grounds122.

114

Smt. Anjali Roy v. State of West Bengal, A.I.R. 1952 Cal. 825 (India). INDIAN WOMEN: LAW AND

POLICY IN INDIA, Pankaj Kakde, Journal of Centre For Social Justice, Issue 1, (2014) pp.59-76

115

ChampakamDorairajanand Ors. v. The State of Madras, A.I.R. 1951 Mad. 120 (India).

116

Anuj Garg and Ors. v. Hotel Association of India and Ors, (2008) 3 S.C.C. 1 (India).

117

CharuKhurana and Ors v. U.O.I and Ors, (2015) 1 S.C.C. 192 (India).

118

WOMEN EMPOWERMENT AND GENDER JUSTICE, Dipak Mishra J.,(2014) 6 SCC (J) pp. J6 – J26

119

CULTURAL AND SOCIAL CHALLENGES CONFRONTING WOMEN:THEIR MARGINALIZATION

AND REALITIES, Vindhya Gupta, Journal Of Centre For Social Justice, Issue 1, (2014) pp.01-08

120

D.D BASU’S, COMMENTARY ON ‘THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA’ 680 (8 th ed., Lexis Nexus 2008)

121

In re Thomas, A.I.R. 1953 Mad. 21 (India).

122

Vol. No. VII, Constituent Assembly Debates, Amendment No. 301 p. 650-664.

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 14

Furthermore, the fact that the expression ‘and public place of public resort’ is added to a

specific enumeration of ‘wells, tanks, bathing Ghats, roads’123 indicates that the expression is

to be interpreted by the rule of ejusdem generis.124 Hence, for the same reason religious

institutions and places of public worship appear to be excluded from the purview of Art.15 (2)

and that is why separate provision in Articles 25 (2) (b) at 26 (b) were needed.125 Thus

petitioners cannot claim the right under 15(2) in case of religious institutions and places of

public worship, and hence they cannot plead a violation of the right guaranteed under Art.15.

Moreover, there is no infringement of Art. 15(3) as ‘special provisions’126 for women and

children can be made only by the State acc. to Art.15.127 So, the petitioners’ argument on

violation of Art.15(3) cannot be entertained by this Court as the rules were framed by the Tenji

board, which is neither State nor a State entity under Art.12128.129 Therefore, it is humbly

submitted that there is no breach of Art.15(2) or 15(3) as temples are not considered a public

place and it is not the state who has formulated the rules on special provisions for women and

children respectively.

3.3. The said restriction does not violate Article 17 of the Constitution

‘Untouchability is abolished and its practice in any form is forbidden. The enforcement of any

disability arising out of Untouchability shall be an offence punishable in accordance with

law.’130Art. 17 of the Constitution131gives expression to equality in abolishing untouchability:

a practice fundamentally at odds to the notion of an equal society.132In the light of the facts and

circumstances of the present case, it becomes imperative to analyse the scope of ‘any form ’.

According to the Black's Law Dictionary133 the word 'any' is defined as: ‘Any, some; one out

of many; an indefinite number; one indiscriminately of whatever kind or quantity; one or some

(indefinitely).”The word ‘any’134 indicates “all” or “every” as well as “some” or “one”

123

KHWAJA.A.MUNTAQIM, EMPOWERMENT OF WOMEN & GENDER JUSTICE IN INDIA 415 (3 rd ed.,

Law Publishers 2011).

124

State of Karnataka v. Appa Balu Ingale, A.I.R. 1993 S.C. 1126 (India).

125

D.D. BASU’S, COMMENTARY ON ‘THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA’,2735 (8 th ed., Lexis Nexus 2008).

126

Government of Andhra Pradesh v. P.B. Vijay Kumar, A.I.R. 1995 S.C. 1648 (India).

127

M. P JAIN, INDIAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 937 (7 th ed., Lexis Nexis 2016).

128

INDIAN CONST. art.12.

129

D.L. KEIR & AMP, CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 73 (4th ed., Oxford University Press 1979).

130

DR.J.N.PANDEY, CONSTITUTIONAL LAW OF INDIA 237 (51 sted., Central Law Agency 2018).

131

State v. Gulab Singh, A.I.R. 1953 All 483 (India).

132

N. Adithayan v. Travancore Devaswom Board and Ors., (2002) 8 S.C.C. 106 (India).

133

Black's Law Dictionary 64 (6th ed.).

134

LAW LEXICON, P. RAMANATHA AIYAR 116 (2 nd ed.).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 15

depending on the context and the subject matter of the statute as laid down in Shri. Balaganesan

Metals v. M. N. Shanmukhan Chetti and Ors.135 Relying on the Principles of Statutory

Interpretation136,

When a word is not defined in the Act itself, it is permissible to refer to

dictionaries to find out the general sense in which that word is understood in

common parlance. However, in selecting one out of the various meanings of

a word, regard must always be had to the context as it is a fundamental rule

that the meanings of words and expressions used in an Act must take their

colour from the context in which they appear.137

The intent with which the Article is embedded in the Constitution needs to be analysed. The

Constitutional Assembly Debates138 elucidate that the practice of “untouchability” 139

is a

symptom of the caste system.140 The subject-matter of Art.17141 is not untouchability in its

literal or grammatical sense142 but “as it had developed historically143 in this country”.144

Interpreting the same on the present facts and circumstances will fall foul under the literal rule

of interpretation.145 Moreover, in Devarajiah v. Padmanna146, the Court held that exclusion of

few individuals from worship, religious services etc., is not within the contemplation of

Art.17147:

Comprehensive as the word ‘ untouchables148’ in the Act is intended to be, it

can only refer to those regarded as untouchables in the course of historical

development. A literal construction of the term would include persons who

are treated as untouchables either temporarily or otherwise for various

reasons, such as their suffering from an epidemic or contagious diseases or

on account of social observances such as are associated with birth or death or

on account of social boycott resulting from caste or other such disputes.149

135

Shri. Balaganesan Metals v. M. N. Shanmukhan Chetti and Ors., (1987) 2 S.C.C. 707 (India).

136

G.P. SINGH, PRINCIPLES OF STATUTORY INTERPRETATION 302 (9 th ed., Lexis Nexis 2004).

137

E.A. DRIEDGER, “A NEW APPROACH TO STATUTORY INTERPRETATION”, 31 Canadian Bar

Review, at 838, (1951).

138

ANNEXURE 1.

139

Jai Singh v. U.O.I, A.I.R. 1993 Raj. 177; State of M.P v. Ram Krishna Bolathia, A.I.R. 1995 S.C. 1198 (India).

140

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar: Writings and Speeches, Government of Maharashtra, Vol. 1 (2014), at pages 5-6.

141

State of Madhya Pradesh v. Purachand, A.I.R. 1958 M.P. 352 (India).

142

H. M. SEERVAI, CONCEPT OF INDIAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 320 (3 rd ed., Universal Law Publishing

Co. Pvt. Ltd. 2010).

143

Dr. Ambedkar’s Paper “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development”, 1916.

144

M.P.JAIN, INDIAN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1008 (7 th ed., Lexis Nexis 2014).

145

Sussex Peerage Case, (1844) 11 Clark and Finnelly 85 (Foreign).

146

Devarajiah v. Padmanna, A.I.R. 1961 Mad. 35, 39 (India).

147

I.L.I., MINORITIES AND THE LAW, 143-170 (1972).

148

SANDRA FREDMAN, DISCRIMINATION LAW (2nded. Clarendon Law Series Book House, 2012).

149

Jai Singh v. U.O.I, A.I.R. 1993 Raj. 177 (India).

Written Submission on behalf of the Respondents

XII AMITY ALL INDIA MOOT COURT COMPETITION, LUCKNOW 2019 16

In State of Karnataka v. Appa Balu Ingale150, the origin of untouchability was traced. It was

sought to establish a new ideal for society by bestowing equality to the Dalits, and ensuring

absence of disabilities, restrictions or prohibitions on grounds of caste or religion, availability

of opportunities and a sense of being a participant in the mainstream of national life.151

It should be duly noted that such kind of gender untouchability152 is not practised in the light

of Rule 3(b). Women of a notified age group are not allowed to enter the temple and such