Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Armitage2005 PDF

Armitage2005 PDF

Uploaded by

ahmedOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Armitage2005 PDF

Armitage2005 PDF

Uploaded by

ahmedCopyright:

Available Formats

Staging Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Staging Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

James O. Armitage, MD

Dr. Armitage is Professor, Depart-

ment of Internal Medicine, Joe ABSTRACT Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas are always treatable and frequently curable malignan-

Shapiro Distinguished Chair of On- cies. However, choosing the most appropriate therapy requires accurate diagnosis and a

cology, University of Nebraska Med-

icine Center, Omaha, NE. careful staging evaluation. New patients with non-Hodgkin Lymphoma should have their tumors

This article is available online at classified using the World Health Organization classification. The specific choice of therapy is

http://CAonline.AmCancerSoc.org

dependent on a careful staging evaluation. Patients with non-Hodgkin Lymphoma are assigned

an anatomic stage using the Ann Arbor system. However, patients should also be classified

using the International Prognostic Index. New insights into the biology of the lymphomas in the

coming years might well improve our ability to evaluate patients and choose therapy. (CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:368–376.)

© American Cancer Society, Inc., 2005.

INTRODUCTION

The development of staging was an important advance in the care of patients with cancer. The concepts of staging

were developed during the 20th century and were formalized in the United States by the establishment of the

American Joint Commission on Cancer in 1959. Although anatomic stage (ie, the specific sites of involvement by

the cancer) was the initial focus of staging, for some cancers other factors are considered. Symptoms, the

differentiation of the tumor, and the results of specific laboratory tests are now included in assigning stage to certain

cancers. Staging accomplishes several important goals in cancer management. These include choosing the best

therapy, allowing an accurate prognosis to be given to the patient and their family, and accurately stratifying patients

to make clinical research and quality assessment possible. In addition, knowing the sites of involvement at diagnosis

makes it possible to accurately restage at the end of therapy and document a complete remission.

Assigning a stage to a newly diagnosed patient with non-Hodgkin Lymphoma is no less important than for other

cancers. However, the development of a staging system for non-Hodgkin Lymphoma has been a difficult and

complicated process. This is, at least in part, due to the heterogeneous nature of illnesses encompassed in the term

“non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.” Lymphoid malignancies are generally classified as leukemia if they involve primarily the

blood and bone marrow and as lymphoma if they present as tumors in lymph nodes or other organs. However, almost

all lymphoid malignancies can have either presentation and some are almost equally likely to present as a leukemia

or lymphoma. In addition, immune system malignancies represent a spectrum from some of the most indolent

malignancies (eg, some mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue [MALT] lymphomas) to the most rapidly progressive

human cancers (eg, Burkitt lymphoma).

The first system widely utilized for staging non-Hodgkin Lymphomas was actually developed for staging Hodgkin

disease and is referred to as the Ann Arbor Staging System.1 Although primarily an anatomic staging system, the Ann

Arbor stages are modified by the presence or absence of systemic symptoms. It was adjusted over the years for the

use in staging Hodgkin disease,2 but still represents a backbone of the staging system recommended today

for non-Hodgkin Lymphomas. However, recognition that the Ann Arbor system does not subdivide some types of

non-Hodgkin Lymphomas in a clinically useful way, and the recognition that other factors are important in

predicting treatment outcome, led to the development of the International Prognostic Index in 1993.3 The

recommendation for the evaluation of a new patient diagnosed with non-Hodgkin Lymphoma currently involves

application of both these systems.

The current recommendations for staging non-Hodgkin Lymphoma adopted by the American Joint Commission

on Cancer are published in the Cancer Staging Manual, sixth edition.4 These have been developed by a committee

368 CA A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:368–376

of experts and are reviewed on a regular basis. TABLE 1 American Joint Committee on Cancer

Lymphoma Task Force Members

The membership of the committee on staging

lymphoid neoplasms can be found in Table 1. Member Location

James O. Armitage, MD, Chair Nebraska

Fernando Cabanillas, MD Puerto Rico

CLASSIFICATION OF NON-HODGKIN LYMPHOMA Inez Evans, CTR, RHIT North Carolina

Richard I. Fisher, MD Illinois

Our ability to classify patients with non- Mary K. Gospodarowicz, MD Canada

Nancy Harris, MD Massachusetts

Hodgkin Lymphomas into clinically useful Richard T. Hoppe, MD California

groupings has steadily improved as our under- Robert A. Kyle, MD Minnesota

standing of the biology of the immune system Michael LeBlanc, PhD Washington

Andrew Lister, MD England

has advanced. The use of histopathology to John Sandlund, MD Tennessee

diagnose malignancies and the discovery of the Dennis D. Weisenburger, MD Nebraska

John W. Yarbro, MD Missouri

Reed Sternberg cell early in the 20th century

allowed a distinction between Hodgkin disease

and the other lymphomas grouped together as

overexpressing the associated Bcl-1 protein led

non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Gall and Mallory

to the acceptance of mantle cell lymphoma as a

proposed a widely used system for subclassify-

specific diagnosis.11 The discovery of CD30

ing the non-Hodgkin Lymphomas in the

(formerly Ki-1) and the recognition that some

1940s.5 However, this system had limited clin-

malignancies marked by CD30 had a t(2;5) and

ical utility. Henry Rappaport used the presence

overexpression of the ALK protein led to the

or absence of a follicular growth pattern and

acceptance of anaplastic large T/null cell lym-

the size and shape of cells to devise the first

phoma as a distinct clinical entity.12–16 Also,

classification system with striking clinical util-

the description of small B-cell lymphomas oc-

ity.6 However, subsequent recognition that

lymphomas were all tumors of lymphocytes curring in association with epithelial tissue,

and that there were different subsets of lym- sometimes developing in association with spe-

phocytes (ie, B, T, and NK cells) led to new cific infections, led to acceptance of the con-

systems. The most popular of these were the cept of MALT lymphomas.17,18 Of course, the

Lukes-Collins classification in the United prototype MALT lymphoma occurs in the

States7 and the Kiel classification in Europe.8,9 stomach and is usually associated with infection

The use of multiple systems of classification by Helicobacter pylori. None of these new lym-

throughout the world posed serious difficulties phomas fit easily into a preexisting category in

for therapeutic research. It was difficult or im- the widely used classification systems and, in

possible to compare the results of therapeutic fact, generally were found in several different

trials when different systems of classification categories.

were utilized. To solve this problem, the In the 1990s, a group of hematopathologists

Working Formulation was developed as a proposed a new system to take into account

compromise system.10 The Working Formula- advances in understanding the biology of the

tion adopted some aspects of the Rappaport immune system and the recognition of these

Classification, the Lukes-Collins Classification, newly accepted subtypes of non-Hodgkin

and Kiel Classification and was the primary Lymphoma, termed the Revised European

system used in publications in much of the American Lymphoma (REAL) classification.19

1980s and 1990s. However, it never became as Diagnoses in the REAL classification were

popular in Europe as in North America. The based on morphology, immunology, and clin-

1980s and 1990s also saw striking advances in ical characteristics. Study of the REAL classifi-

our understanding of biology of the immune cation showed that it was clinically relevant and

system and recognition that some lymphomas more reproducible than previous systems.20

didn’t fit easily into the existing categories. The The concepts embodied in the REAL classifi-

study of lymphomas carrying the t(11;14) and cation were used to develop the World Health

Volume 55 Y Number 6 Y November/December 2005 369

Staging Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Organization (WHO) classification of lym- extra lymphatic tumor. Large cutting needle

phoma that is currently the gold standard biopsies are an alternative in selected cases

throughout the world.21 where excisional biopsy is difficult or danger-

The WHO classification is presented in Ta- ous. Fine-needle aspirates are not appropriate

ble 2. It subdivides tumors into those of B-cell and should not be the basis for primary diag-

versus T/NK-cell origin and those with an nosis of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma and the sub-

immature or blastic appearance versus those sequent choice of therapy.22

developing from more mature stages of lym-

phoid development. The latter tumors, in the

case of T-cell lymphomas, were referred to as ANN ARBOR STAGING

“peripheral” T-cell lymphomas. Today, the

first step in evaluation of any patient with non- Although originally developed for staging

Hodgkin Lymphoma should be classification of patients with Hodgkin disease, the Ann Arbor

their tumor in the World Health Organization staging system provides the basis for anatomic

classification. This should include the per- staging in non-Hodgkin Lymphomas as well.

formance of immunophenotyping and might However, the use of the Ann Arbor staging

require cytogenetics, fluorescent in situ hybrid- system for non-Hodgkin Lymphomas has a

ization (FISH), antigen receptor gene rear- number of shortcomings. These relate in large

rangement studies, and other investigations. If part to the different pattern of disease seen in

at all possible, this should be done by an expe- the non-Hodgkin Lymphomas as opposed to

rienced hematopathologist working with an Hodgkin disease. For example, primary extra-

excisional biopsy of an affected lymph node or nodal Hodgkin disease is rare, but a primary

TABLE 2 World Health Organization Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms

B-cell neoplasms

Precursor B-cell neoplasm

Precursor B-lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (precursor B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia)

Mature (peripheral) B-cell neoplasms

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma

B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma

Splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (with or without villous lymphocytes)

Hairy cell leukemia

Plasma cell myeloma/plasmacytoma

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (with or without monocytoid B cells)

Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (with or without monocytoid B cells)

Follicular lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Burkitt lymphoma/Burkitt cell leukemia

T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms

Precursor T-cell neoplasm

Precursor T-lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (precursor T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia)

Mature (peripheral) T/NK-cell neoplasma

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia

T-cell granular lymphocytic leukemia

Aggressive NK-cell leukemia

Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (HTLV1⫹)

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type

Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma

Hepatosplenic gamma delta T-cell lymphoma

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma

Mycosis fungoides/Sezary syndrome

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, T/null cell, primary cutaneous type

Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise characterized

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma

Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, T/null cell, primary systemic type

370 CA A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:368–376

extra nodal site is frequently seen in certain tion with regional lymph node involvement

types of non-Hodgkin Lymphomas and is al- with or without involvement of other lymph

ways the case in MALT lymphomas. In addi- node regions on the same side of the diaphragm

tion, some types of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (IIE). The number of regions involved may be

(eg, small lymphocytic lymphoma and mantle indicated by a subscript, for example, II3. Stage

cell lymphoma) have bone-marrow involve- III: Involvement of lymph node regions on

ment in the majority of patients, placing a both sides of the diaphragm (III), which also

disproportionally high number of patients in may be accompanied by extralymphatic exten-

the highest stage. Despite these shortcomings, sion in association with adjacent lymph node

the Ann Arbor staging classification remains the involvement (IIIE) or by involvement of the

best method available for anatomic staging of spleen (IIIS) or both (IIIE,S). Stage IV: Diffuse

non-Hodgkin Lymphomas and has been uni- or disseminated involvement of one or more

versally adopted for this purpose. extralymphatic organs, with or without associ-

The Ann Arbor staging system divides pa- ated lymph node involvement; or isolated ex-

tients into four stages based on localized dis- tralymphatic organ involvement in the absence

ease, multiple sites of disease on one or the of adjacent regional lymph node involvement,

other side of the diaphragm, lymphatic disease but in conjunction with disease in distant

on both sides of the diaphragm, and dissemi- site(s). Any involvement of the liver or bone

nated extranodal disease (Table 3). Localized marrow, or nodular involvement of the lung(s)

extranodal sites of involvement are recognized is always Stage IV. The location of Stage IV

by a subscript E. disease is identified further by specifying site

The definition of these stages as found in the according to the notations listed for Stage III.

Cancer Staging Manual is as follows: Stage I: The distinction between Stage I and Stage II

Involvement of a single lymph node region (I), involvement is based not on individual lymph

or localized involvement of a single extralym- nodes but on what are termed as “lymph node

phatic organ or site in the absence of any lymph regions.” Lymph node regions were defined at

node involvement (IE) (rare in Hodgkin dis- the Rye Symposium in 1965 and have been

ease). Stage II: Involvement of two or more accepted by convention since that time. The

lymph node regions on the same side of the lymph node regions include right cervical (in-

diaphragm (II), or localized involvement of a cluding cervical, supraclavicular, occipital, and

single extralymphatic organ or site in associa- preauricular lymph nodes), left cervical, right

TABLE 3 Ann Arbor Classification and the Cotswold Modifications

Stage Features

I Involvement of a single lymph node region or lymphoid structure (eg, spleen, thymus, Waldeyer’s ring)

II Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm

III Involvement of lymph regions or structures on both sides of the diaphragm

IV Involvement of extranodal site(s) beyond that designated E

For all stages

A No symptoms

B Fever (⬎38oC), drenching sweats, weight loss (10% body weight over 6 months)

For Stages I to III

E Involvement of a single, extranodal site contiguous or proximal to known nodal site

Cotswold modifications

Massive mediastinal disease has been defined by the Cotswold meeting as a thoracic ratio of maximun transverse

mass diameter greater than or equal to 33% of the internal transverse thoracic diameter measured at the T5/6

intervertebral disc level on chest radiography.

The number of anatomic regions involved should be indicated by a subscript (eg, II3)

Stage III may be subdivided into: III1, with or without plenic, hilar, celiac, or portal nodes;III2, with para-aortic, iliac,

mesenteric nodes

Staging should be identified as clinical stage (CS) or pathologic stage (PS)

A new category of response to therapy, unconfirmed/uncertain complete remission (CR) can be introduced

because of the persistent radiologic abnormalities of uncertain significance

Volume 55 Y Number 6 Y November/December 2005 371

Staging Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

axillary, left axillary, right infraclavicular, left opsy. The basic staging and investigation for a

infraclavicular, mediastinal, hilar, periaortic, mes- patient with non-Hodgkin Lymphoma in-

sentary, right pelvic, left pelvic, right inguinal cludes all these studies with images usually ob-

femoral, and left inguinal femoral. Multiple tained using computed tomography (CT)

lymph nodes palpable in one of these regions scans. In patients unable to safely undergo a CT

would be Stage I, and involvement of two of scan, magnetic resonance imaging studies are

these regions but on one side of the diaphragm often substituted. Recent advances in func-

would represent Stage II. Unlike Hodgkin dis- tional imaging using positron emission tomog-

ease, it is not uncommon for non-Hodgkin Lym- raphy scans have expanded the possibilities for

phoma to involve other lymph node sites not imaging in non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. How-

included in the core sites from the original Ann ever, clear definitions of what constitutes a site

Arbor classification. These might include epitrao- of involvement and whether or not positron

clear, popliteal, internal mammary, occipital, sub- emission tomography scans can substitute for

mental, perauricular, and other small lymph node CT scans are a point for debate and investiga-

areas. Each of these could also be considered a tion. Patients at high risk for central nervous

separate lymph node site and used in the distinc- system involvement should have a lumbar

tion between Stage I and Stage II. puncture and cerebrospinal fluid cy-

The designation of Stage IV disease implies tology performed. Bone marrow biopsy is a

disseminated disease involving extranodal sites. standard part of the clinical investigation.

However, by convention, involvement of the However, what is an appropriate bone marrow

bone marrow, liver, pleura, and cerebrospinal biopsy has been a point of disagreement, with

fluid are always considered Stage IV even if the some experts saying that bilateral biopsies are

disease is isolated to that organ. Lymphatic necessary. The most important part of a bone

involvement in a draining area from a primary marrow biopsy is obtaining an adequate core

extranodal lymphoma should be designated as for histological evaluation (ie, at least 15 to 20

IIE (eg, a thyroid lymphoma with cervical mm). Whether this is done with one or mul-

lymph node involvement). Lymphoma extend- tiple punctures probably does not matter. Bi-

ing beyond the lymph node capsule involving opsy of other sites (ie, beyond the initial

adjacent organs should also receive the E suffix excisional biopsy on which the diagnosis was

and not be called Stage IV (eg, lymphoma in based) would normally only be done if the

mediastinal lymph nodes growing directly into results might modify therapy.

adjacent lung). It is true that unusual cases In the past there has been debate on how

might lead to debate about the appropriate large a lymph node needed to be for it to be

assignment of Stage IIE or Stage IV, and some- considered abnormal. By convention, lymph

times even experts can disagree about which nodes greater than 1.5 cm in maximum diam-

would be most appropriate. eter are now considered abnormal and assumed

Anatomic staging in non-Hodgkin Lym- to be involved by disease. Documenting

phoma can be done using history, physical ex- splenic involvement lymphoma can be prob-

amination, laboratory studies, and images, in lematic but is usually done by identifying pal-

addition to definitive proof of involvement of a pably enlarged spleens or focal defects seen on

particular site from biopsy. As a practical point, imaging studies. Liver involvement is usually

most patients are assigned their stage based on demonstrated by multiple defects on imaging

the results of noninvasive studies rather than studies consistent with involvement by neo-

having biopsies to document each apparent site plasm or by liver biopsy. The presence of a

of involvement. palpable liver or abnormal liver chemistries

Appropriate clinical staging includes: a care- should not be used alone to assume involve-

ful recording of history and physical examina- ment of the liver by lymphoma. Lung involve-

tion; appropriate images of the chest, abdomen, ment is usually documented by presence of

and pelvis; blood chemistry measurements; characteristic imaging abnormalities. On occa-

complete blood count; and bone marrow bi- sion, lung biopsy may be necessary to clarify

372 CA A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:368–376

equivocal cases. Clinical involvement of the are not localized and the ability to better assess

brain can be documented by characteristic im- the majority of patients for treatment decisions

aging abnormalities in a patient with lym- and to stratify patients in clinical trials is ex-

phoma known to metastasize to the brain. tremely important. In 1993, the International

However, this is an unusual situation. More Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Prognostic Index

commonly, primary brain lymphomas require was published.3 This was the result of an inter-

biopsy to document their presence. national collaboration involving more than

Although more useful in Hodgkin disease, 2,000 patients with aggressive non-Hodgkin

the Ann Arbor Staging system also designates Lymphoma who were treated with an anthra-

patients as either being suffix A or B. Designa- cycline-based combination chemotherapy reg-

tion as A indicates the absence of unexplained imen. Although originally intended for the use

fever with temperature greater than 38°C, in patients with aggressive lymphomas, this in-

dex has utility for all types of non-Hodgkin

drenching night sweats requiring the change of

Lymphoma and has been widely applied.

bedclothes, and unexplained weight loss of

Results of the International Prognostic In-

more than 10% in the 6 months before diag-

dex study showed that five factors were

nosis.

roughly equal in power in predicting treatment

outcome (Table 4). These included age greater

INTERNATIONAL PROGNOSTIC INDEX

or less than 60 years, Ann Arbor Stage I and II

versus Stage III or IV, none or one versus two

The Ann Arbor Staging system does not or more sites of extranodal involvement by

adequately provide prognostic information for lymphoma, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology

many subtypes of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Group performance status (Table 5) of Grade 0

and is far from optimal for making treatment or 1 versus Grade 2 or greater, and a normal

decisions. Knowing when the disease is local- versus elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

The number of adverse prognostic factors (ie,

ized is an important factor for all types of lym-

age ⬎ 60 years, advanced stage, two or more

phoma, but most non-Hodgkin Lymphomas

extranodal sites, poor performance status, or

elevated LDH) could be simply summed be-

TABLE 4 International Prognostic Index cause each had approximately the same power

Prognostic Factors

in predicting treatment outcome. Thus, a score

Age ⬎ 60 years of 0 to 5 was possible. The original publication

Performance status ⬎ 2 suggested the patients be lumped into groups

Lactate dehydrogenase 1⫻ normal

Extranodal sites ⬎ 2 with a low risk (ie, score of 0 or 1), low

Stage III or IV intermediate risk (score of 2), a high interme-

Risk Category (Factors) diate group (score of 3), and a high risk (score

Low (0 or 1)

Low-intermediate (2) of 4 or 5). In the original study and in previous

High-intermediate (3) experience, there is a highly significant impact

High (4 or 5)

on chances to achieve a remission, remain in

TABLE 5 Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status*

Grade Description

0 Fully active, able to carry on all predisease performance without restriction

1 Restricted in physically strenuous activity but ambulatory and able to carry out work of a light or sedentary nature (eg, light housework,

office work)

2 Ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities. Up and about more than 50% of waking hours

3 Capable of only limited self-care, confined to bed or chair more than 50% of waking hours

4 Completely disabled. Cannot carry on any self-care. Totally confined to bed or chair

5 Dead

*As published in Oken, et al.23

Volume 55 Y Number 6 Y November/December 2005 373

Staging Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

TABLE 6 International Prognostic Index

Five-year

Complete Relapse-free Five-year

Number of Response Rate Survival Overall Survival

Risk Factors (%) (%) (%)

All patients*

Low 0 or 1 87 70 73

Low intermediate 2 67 50 51

High intermediate 3 55 49 43

High 4 or 5 44 40 26

Age-adjusted index, patients ⱕ60 years†

Low 0 92 86 83

Low intermediate 1 78 66 69

High intermediate 2 57 53 46

High 3 46 58 32

*Adverse factors: age ⬎ 60 years, increasing lactate dehydrogenase, performance status 2 to 4, more than one extranodal

site, Ann Arbor Stage III or IV.

†Adverse factors: elevated lactate dehydrogenase, performance status 2 to 4, Ann Arbor Stage III or IV.

remission, and overall survival based on the

International Prognostic Index score. For ex-

ample, patients in the low-risk group in the

original publication had an 87% complete

remission rate and an overall survival of 73%

at 5 years versus a 44% complete remission

rate and 26% survival at 5 years in the high-

risk group (Table 6).3

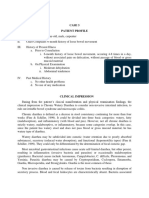

Particularly important was documentation

that the International Prognostic Index score

was able to subdivide patients in Ann Arbor

Stage II, III, and IV (Figure 1). The dramatic

difference in treatment outcome for patients

with the same Ann Arbor Stage found by

utilizing the International Prognostic Index

undoubtedly explains wide discrepancies in

the results of some previous clinical trials.

For example, in Phase II trials, several che-

motherapy regimens seemed to be superior

to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincris-

tine, and prednisone in the treatment of ag-

gressive lymphoma24 –26 but yielded the same

outcome in a head-to-head Phase III trial.27

In retrospect, the earlier studies almost cer-

tainly treated patients with a better progno-

sis, although the stages were similar.

The International Prognostic Index is pre-

sented in Table 4. This should be calculated on

FIGURE 1 The International Prognostic Index Score every new patient with non-Hodgkin Lym-

Identifies Patients With Differing Prognoses in Patients

With Ann Arbor Stage II, III, and IV Aggressive Non-

phoma and will have an important impact on

Hodgkin Lymphoma. the treatment decision.

374 CA A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:368–376

THE FUTURE The primary site of origin of a non-Hodgkin

Lymphoma almost certainly affects the biological

There will be further advances in our ability characteristics of the malignancy. There is no

to evaluate patients with non-Hodgkin Lym- reason to believe that diffuse large B-cell lym-

phoma. An obvious possibility, and one that is phoma originating in different sites of the body

currently being tested, is to have different sys- would have the same behavior any more than we

tems for different subsets of patients. For ex- would think that all squamous cell carcinomas,

ample, the International Prognostic Index has a regardless of origin, would have the same behav-

modification for patients younger than and

ior. It is possible that different types of evaluations

older than 60 years old (Table 5).3 A new

would be appropriate for tumors originating in

system has been developed for patients with

different parts of the body.

follicular lymphoma (ie, the Follicular Lym-

The most important factor likely to change

phoma Prognostic Index) to take into account

the way we evaluate patients with lymphoma is

differences between these patients and those

with diffuse aggressive non-Hodgkin Lympho- the rapidly expanding knowledge about gene

ma.28 The American College of Surgeons Stag- expression patterns and protein expression.29,30

ing Manual presents different systems for It is possible to imagine a time when the only

children with non-Hodgkin Lymphoma that evaluation of a new patient with lymphoma

are widely used by pediatric oncologists and that would be required would be identification

one for patients with cutaneous T-cell lympho- of the expression of certain key proteins. If

ma.4 drugs that specifically targeted these proteins

None of the systems currently in use for were available, and they could cure most or all

evaluation of adult patients with non-Hodgkin patients, other evaluation could be superfluous.

Lymphoma account for the presence of a bulky Although certainly a goal for the future, it is

mass. This probably relates the lack of uniform not impossible that we could reach this point.

data collection about the maximum tumor di- Whatever the future holds, at the present

ameter in previous studies. However, the pres- time an accurate staging evaluation is key to the

ence of a very large mass is a predictor of poor management of a patient with newly diagnosed

treatment outcome, and clinicians often take non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. Careful application

very bulky sites of disease into account by of the systems described in this paper will lead

adding radiotherapy to that site. to the best possible treatment outcome.

REFERENCES 7. Lukes RJ, Collins RD. Immunologic charac- 12. Stein H, Mason DY, Gerdes J, et al. The

terization of human malignant lymphomas. expression of the Hodgkin’s disease associated

1. Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K, et al.

Cancer 1974;34(4 Suppl):1488 –1503. antigen Ki-1 in reactive and neoplastic lym-

Report of the committee on Hodgkin’s disease stag-

8. Lennert K, Stein H. Malignant Lymphomas phoid tissue: evidence that Reed-Sternberg

ing classification. Cancer Res 1971;31:1860–1861.

Other than Hodgkin’s Disease: Histology, Cytol- cells and histiocytic malignancies are derived

2. Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, et al. from activated lymphoid cells. Blood 1985;66:

ogy, Ultrastructure, Immunology. New York:

Report of a committee convened to discuss the Springer-Verlag; 1978. 848–858.

evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin’s

9. Lennert K, Stein H, Kaiserling E. Cytological 13. Kaneko Y, Frizzera G, Edamura S, et al. A

disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol 1989;

and functional criteria for the classification of novel translocation, t(2;5)(p23;q35), in child-

7:1630–1636.

malignant lymphomata. Br J Cancer 1975;31 hood phagocytic large T-cell lymphoma mim-

3. A predictive model for aggressive non- (Suppl 2):29 – 43. icking malignant histiocytosis. Blood 1989;73:

Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The International Non- 806–813.

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Prognostic Factors Project. 10. National Cancer Institute sponsored

study of classifications of non-Hodgkin’s 14. Rimokh R, Magaud JP, Berger F, et al. A

N Engl J Med 1993;329:987–994.

lymphomas: summary and description of a translocation involving a specific breakpoint (q35)

4. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New working formulation for clinical usage. on chromosome 5 is characteristic of anaplastic

York: Springer; 2002. The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Pathologic large cell lymphoma (‘Ki-1 lymphoma’). Br J

5. Gall E, Mallory T. Malignant lymphoma. A clin- Classification Project. Cancer 1982;49:2112– Haematol 1989;71:31–36.

icopathologic survey of 618 cases. Am J Pathol 2135. 15. Bitter MA, Franklin WA, Larson RA, et al.

1942;18:381. 11. Rimokh R, Berger F, Delsol G, et al. Rear- Morphology in Ki-1(CD30)-positive non-

6. Hicks EB, Rappaport H, Winter WJ. Follic- rangement and overexpression of the BCL-1/ Hodgkin’s lymphoma is correlated with clinical

ular lymphoma; a re-evaluation of its position in PRAD-1 gene in intermediate lymphocytic features and the presence of a unique chromo-

the scheme of malignant lymphoma, based on a lymphomas and in t(11q13)-bearing leukemias. somal abnormality, t(2;5)(p23;q35). Am J Surg

survey of 253 cases. Cancer 1956;9:792–821. Blood 1993;81:3063–3067. Pathol 1990;14:305–316.

Volume 55 Y Number 6 Y November/December 2005 375

Staging Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

16. Mason DY, Bastard C, Rimokh R, et al. 21. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of 26. Shipp MA, Yeap BY, Harrington DP, et al.

CD30-positive large cell lymphomas (‘Ki-1 lym- Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, in Jaffe The m-BACOD combination chemotherapy regi-

phoma’) are associated with a chromosomal trans- E, Harris N, Stein H, Vardiman J (eds). World men in large-cell lymphoma: analysis of the com-

location involving 5q35 [see comments]. Br J Health Organization Classification of Tumors. pleted trial and comparison with the M-BACOD

Haematol 1990;74:161–168. Lyon: IARC Press; 2001. regimen. J Clin Oncol 1990;8:84–93.

17. Isaacson P, Wright DH. Malignant lym- 22. Hehn ST, Grogan TM, Miller TP. Utility of 27. Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, et al.

phoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. A fine-needle aspiration as a diagnostic technique in Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with

distinctive type of B-cell lymphoma. Cancer lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3046 –3052. three intensive chemotherapy regimens for ad-

1983;52:1410–1416. 23. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. vanced non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med

Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Co- 1993;328:1002–1006.

18. Isaacson P, Wright DH. Extranodal malig-

operative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol 28. Solal-Celigny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al.

nant lymphoma arising from mucosa-associated

1982;5:649 – 655. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic in-

lymphoid tissue. Cancer 1984;53:2515–2524. dex. Blood 2004;104:1258–1265.

24. Longo DL, DeVita VT, Jr., Duffey, PL,

19. Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, et al. A revised et al. Superiority of ProMACE-CytaBOM over 29. Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, et al.

European-American classification of lymphoid neo- ProMACE-MOPP in the treatment of ad- The use of molecular profiling to predict survival

plasms: a proposal from the International Lym- vanced diffuse aggressive lymphoma: results of after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lym-

phoma Study Group. Blood 1994;84:1361–1392. a prospective randomized trial. J Clin Oncol phoma. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1937–1947.

20. The non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma classification 1991;9:25–38. 30. Shipp MA, Ross KN, Tamayo P, et al. Dif-

project: a clinical evaluation of the International 25. Klimo P, Connors JM. MACOP-B chemo- fuse large B-cell lymphoma outcome prediction

Lymphoma Study Group classification of non- therapy for the treatment of diffuse large-cell by gene-expression profiling and supervised ma-

Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood 1997;89:3909 –3918. lymphoma. Ann Intern Med 1985;102:596–602. chine learning. Nat Med 2002;8:68–74.

376 CA A Cancer Journal for Clinicians

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- RxPrep 6-8 Week Study Review ScheduleDocument5 pagesRxPrep 6-8 Week Study Review ScheduleKilva Eratul100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Sel&Ass&Pae&Lis&Car&1 STDocument198 pagesSel&Ass&Pae&Lis&Car&1 STali tida100% (1)

- NCP: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and AsthmaDocument15 pagesNCP: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and AsthmaJavie100% (5)

- 25 RDSDocument7 pages25 RDSFinty ArfianNo ratings yet

- Neurology Clerkship UWORLD: Brain TumoursDocument13 pagesNeurology Clerkship UWORLD: Brain TumoursHaadi AliNo ratings yet

- Brain TumorsDocument2 pagesBrain TumorsScott McElroyNo ratings yet

- 1-CBC InterpretationDocument10 pages1-CBC Interpretationمصطفي خندقاويNo ratings yet

- Researching Alzheimer's Medicines - Setbacks and Stepping StonesDocument20 pagesResearching Alzheimer's Medicines - Setbacks and Stepping StonesOscar EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Leishmaniasis: Dr. Kazi Shihab Uddin Mbbs MRCP (Uk) Associate Professor & HOD Department of Internal MedicineDocument20 pagesLeishmaniasis: Dr. Kazi Shihab Uddin Mbbs MRCP (Uk) Associate Professor & HOD Department of Internal MedicineSHIHAB UDDIN KAZINo ratings yet

- Folinic AcidDocument1 pageFolinic AcidMuhammad ArsalanNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument7 pagesBackground of The StudyVern LeStrangeNo ratings yet

- Signs NotesDocument22 pagesSigns NotesVaidehi guptaNo ratings yet

- Herpes Simplex Type-1 Virus Infection (2003)Document16 pagesHerpes Simplex Type-1 Virus Infection (2003)Aron RonalNo ratings yet

- FMGE JUNE-2109 Questions: AriseDocument20 pagesFMGE JUNE-2109 Questions: AriseSugithaTamilarasanNo ratings yet

- Kawasaki Disease-NcpDocument5 pagesKawasaki Disease-NcpBelen SoleroNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology CVA (Final2)Document10 pagesPathophysiology CVA (Final2)Jayselle Costes FelipeNo ratings yet

- HeparinDocument6 pagesHeparinFrank Asiedu AduseiNo ratings yet

- Mixed Group: Name: Age: Sex: Weight: Address: OccupationDocument23 pagesMixed Group: Name: Age: Sex: Weight: Address: OccupationKristian Karl Bautista Kiw-isNo ratings yet

- Stroke Differential Diagnosis and Mimics Part 1Document11 pagesStroke Differential Diagnosis and Mimics Part 1AnthoNo ratings yet

- The 90 Day Program To Beat Candida Restore Vibrant HealthDocument136 pagesThe 90 Day Program To Beat Candida Restore Vibrant HealthMihaela NNo ratings yet

- Peptic Ulcer Disease UpdatedDocument19 pagesPeptic Ulcer Disease UpdatedKiara GovenderNo ratings yet

- Ovariancancer 161007042738Document63 pagesOvariancancer 161007042738Syahmi YahyaNo ratings yet

- Practice Essentials: Abruptio PlacentaeDocument2 pagesPractice Essentials: Abruptio PlacentaeNurnajwa PahimiNo ratings yet

- Case Study - Parkinson'S Disease: Clinical Pharmacy & Therapeutics 1Document13 pagesCase Study - Parkinson'S Disease: Clinical Pharmacy & Therapeutics 1Jenesis Cairo CuaresmaNo ratings yet

- HydronephrosisDocument2 pagesHydronephrosisStefan ZemoraNo ratings yet

- 2024-Article Text-6560-1-10-20230128Document4 pages2024-Article Text-6560-1-10-20230128Adniana NareswariNo ratings yet

- Anemia OsamaDocument57 pagesAnemia Osamaosamafoud7710No ratings yet

- Note DR Ikhwan SaniDocument39 pagesNote DR Ikhwan SaniShutter Man100% (1)

- Para PBL CompleteDocument9 pagesPara PBL CompleteMerill Harrelson LibanNo ratings yet

- XXX. MCQ Cardiovascular System Book 315-336Document19 pagesXXX. MCQ Cardiovascular System Book 315-336Maria OnofreiNo ratings yet