Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Civil Procedure II Outline

Civil Procedure II Outline

Uploaded by

Daniyal HstegOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Civil Procedure II Outline

Civil Procedure II Outline

Uploaded by

Daniyal HstegCopyright:

Available Formats

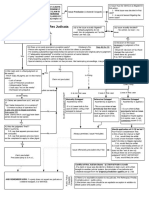

CHECKLIST TO CIVIL PROCEDURE II

I. JOINDER OF CLAIMS/PARTIES

A. Joinder Of Claims

B. Joinder Of Parties

II. DISCLOSURgDISCOVERY

A. Purpose/Effect

B. Automatic Disclosure

C. Scope

D. Discovery Devices

E. Protective Orders

F. Sanctions

G. Pretrial Conference

JII. PRE.TRIAL DISPOSITION

A. Default Judgment

B. Voluntary Dismissal

C. Involuntary Dismissal

D. Consent Judgment

E. Motion For Summary Judgment

IV. JURY TRIAL

V. MOTIONS AT THE CLOSE OF PROOF AND MOTIONS AFTER VERDICT

A. Motion For Judgment As A Matter Of Law

B. Renewed Motion for Judgment As A Matter Of Law

C. New Trial

VI. APPELLATE REVIEW

A. Appealability

B. Reviewability

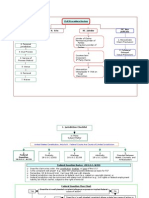

VII. DOCTRINES OF FORMER ADJUDICATION

A. Former Adjudication

B. Claim Preclusion - Res Judicata

C. Issue Preclusion - Collateral Estoppel

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page I

t.

A. Joinder Of Claims:

1. Joinder of claims by a single plaintiff against a single defendant

a. Federal practice: A single plaintiff may join any and all claims he has against

a single defendant, even if they are unrelated. F.R.C.P. 18. Therb is no

compulsory claims joinder rule, i.e., no joinder rule requires plaintiff to join

claims - even if related - in one suit. However, the common law doctrine of

Res Judicata, in effect, requires plaintiff to join related claims (no claim

splitting). See Res Judicata, Section VII, infra, atpage 41.

b. State practice (code pleading): Some state claims joinder rules require that

claims arise out of the same transaction or involve common questions of law.

2. Counterclaims and Cross-claims

a. Federal practice

1) Counterclaims: A counterclaim is an affirmative claim asserted in a

defensive pleading (typically, the answer) that the pleader (typically, a

defendant) has against an opposing party (typically, a plaintiff).

a) Compulsory counterclaims: If the counterclaim arises out of

the same transaction or occulrence ("logical relation" test) as

the opposing party's claim, it must be asserted or the claim will

be barred in a subsequent suit.

NOTE - Ancillary jurisdiction cross-over: Federal courts assert

ancillary jurisdiction over compulsory counterclaims.

b) Permissive counterclaims: If the counterclaim does not arise out of

the same transaction or occurrence as the opposing party's claim, it

may be asserted at defendant's option. Federal courts will not

assert ancillary jurisdiction over permissive counterclaims.

2) Cross-claims: A cross-claim is:

a) A claim by a party against a co-party (e.g., co-defendants)

b) That arises out of the same transaction or occurrence that is the

subject of the original action. ("Logical Relation" test)

Cross-claims are never compulsory; only permissive. They are

asserted in the defensive pleading (typically, the answer).

NOTE - Ancillary jurisdiction cross-over: Federal courts assert

ancillary jurisdiction over proper cross-claims.

b. State practice

1) Cross-complaint: California does not recognize the counterclaim or

cross-claim, but rather provides that a defendant's claim against any

party may be asserted by way of a cross-complaint.

a) A cross-complaint is a separate pleading and is not part of the

answer.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007') Civil Procedure II Page 2

B. Joinder Of Parties:

l Permissive party joinder: All persons may join in one action as plaintiffs or be joined

in one action as defendants if:

a. A right to relief is asserted by, or against, each plaintiff or defendant relating

to or arising out of the same transaction or occuffence, or series of

transactions or occutrences (logical relation test); and

b. Any question of law or fact common to all these persons will arise in the action.

NOTE - Potential "pendent party jurisdiction" crossover.

2. Compulsory party joinder ("necessary and indispensable parties")

a. Necessary party (a party who should be joined, if feasible): F.R.C.P. l9(a) provides

that a person who is subject to service of process (i.e., personal jurisdiction) and

whose joinder will not deprive the court of jurisdiction over the subject matter (i.e.,

destroy complete diversity) should be joined as a party in the action if:

1) In his absence complete relief cannot be accorded among those already

parties, or

2) His interest in the subject of the lawsuit is such that to proceed without

him may either

a) As a practical matter impair or impede his ability to protect that

interest in a later proceeding or

b) Expose those already parties to the lawsuit to a substantial risk

of double, multiple or otherwise inconsistent obligations.

b. Indispensable party (a necessary party whom it is not feasible to join and in

whose absence the lawsuit - "in equity and good conscience" - should be

dismissed): This issue arises where the court has determined, under Rule 19(a),

that the person (i.e., "nonparty") should be joined but it is not feasible to do

so, either because the nonparty is not subject to personal jurisdiction in the

forum or his joinder would destroy diversity jurisdiction.

The court then faces the "indispensable party" issue whether, "in equity and

good conscience", the lawsuit should proceed without the nonparty or should

be dismissed because proceeding in his absence would be too prejudicial to

the rights of both the nonparty and persons already parties to the action. If the

court, weighing the following factors, determines "in equity and good

conscience" that the suit should be dismissed, then the nonparty is labeled an

"indispensable party" :

l) To what extent a judgment rendered in the person's absence might be

prejudicial to him or those already parties;

2) The extent to which the court, by the shaping of relief or other

practical measures, can lessen or avoid prejudice;

3) Whether a judgment rendered in the person's absence will be adequate;

4) Whether the plaintiff, if his suit is dismissed for nonjoinder, will have

an adequate alternative forum in which to bring his suit.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 3

c. Exam analysis: Attempt to argue against indispensability. Modernly, any interested

party should be joined if practical considerations dictate (complete relief)

d. Challenging nonjoinder of an indispensable party: Defendant can move to dismiss

for failure to join an indispensable party either in a pre-answer motion [Rule 12(b)]

or anytime thereafter in the lawsuit (even on appeal for the first time). Therefore,

this objection is not waived during the life of the original lawsuit.

e. Exam tip:

1) Permissive joinder issue asks: may the plaintiffs join in one suit or

may they join several defendants in one suit?

2) Compulsory joinder issue asks: must a nonparty (e.g., one not

voluntarily sued by plaintiff and who does not seek to join the action

through "intervention") be joined? Three step analysis:

a) "Necessary party" issue asks: Should the nonparty be joined?

lApply Rule 19(a)l

b) If so, is it feasible to join the necessary party?

c) "Indispensable party" issue asks: if the nonparty should be joined

[applying Rule 19(a)], but it is not feasible to do so (because he is

not subject to personal jurisdiction or his joinder will destroy

complete diversity), should the court dismiss the suit rather than

proceed in the absence of the nonparty? [Apply Rule 19(b)]

3. Impleader ("third party practice"): A defendant is permitted to bring into the lawsuit an

additional party ("a person not a party to the action") who is or may be liable to the

defendant for all or part of the original plaintiffs claim against the defendant. The

additional party is called the third party defendant and the defendant is called the Third

Party Plaintiff. The purpose of impleader is to permit a defendant to join a derivative or

contingent claim for indemnity against a person not sued by the plaintiff as a defendant.

CAVEAT: A defendant cannot use impleader to shift liability to a person defendant

contends is directly liable to the plaintiff. Defendant can only join "derivative" or

"contingent" (not independent) claims against Third Party Defendant.

e.g., FRAZIER v. HARLEY DAVIDSON MOTOR CO.

Example: P sues D and D impleads his liability insurer.

NOTE - Ancillary jurisdiction crossover: Federal courts will assert ancillary

jurisdiction over properly impleaded claims.

4. Intervention: A nonparty, upon timely application, may voluntarily become a party to

a lawsuit between other parties in order to protect his interest

a. Intervention of right: A nonparty must be allowed to intervene

1) When a statute of the United States confers an unconditional right to

intervene; or

. 2) When one claims

a) An interest to the property or transaction which is the subject

of the lawsuit and

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 4

b) The disposition of the action in the intervenor's absence will be

likely to impair his ability to protect that interest and

c) Existing parties to the action cannot adequately protect the

intervenor's interests

NOTE - Ancillary Jurisdiction Crossover: Federal courts will assert

ancillary jurisdiction over claims asserted by one who intervenes as of

right, except where to do so would be inconsistent with the statutory

requirement of "complete diversity".

b. Permissive intervention: A nonparty may be allowed to intervene:

l) When a statute of the United States confers a conditional right to

intervene; or

2) When an applicant's claim or defense and the main action have a

question of law or fact in common. (key issue on exam)

NOTE - No ancillary jurisdiction: Permissive intervention requlres

an independent basis of subject matter jurisdiction

5. Interpleader

a. Interpleader is a joinder device by which a person holding property (the

"stakeholder"), who may be subject to inconsistent claims on that property

(the "stake"), can join all the claimants in one interpleader action and require

them to litigate among themselves to determine who has a right to the

property.

b. Purposes

1) To protect the stakeholder from the risk of incurring double or multiple

liability

Example: Husband dies leaving life insurance policy to "my wife". Wife 1

and Wife 2 both claim the total proceeds. Their claims are adverse (because

they are mutually exclusive). If Insurer pays the full amount to Wife 1, it

runs a substantial risk of having to pay Wife 2 also.

2) Interpleader can also be properly invoked where the claims against the

stake are not technically adverse so that there is no risk to the

stakeholder of incurring double or multiple liability, but the claims, in

the aggregate, exceed a limited fund held by the stakeholder.

Example: Insurer issues a liability insurance policy to Insured limited

to $20,000 per accident. If Insured is involved in an accident with Bus

Company, Insurermay properly file an interpleader action requesting

the court to determine how to allocate the $20,000 among the various

bus passenger-claimants. Here, the purpose of interpleader is not to

protect Insurer from multiple liability (because there is no such risk),

but rather to protect the claimants from prejudice which could occur if

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 5

the first few claimants to assert their claims totally depleted the

$20,000 leaving nothing for the remaining claimants.

3) Judicial economy

c. Federal interpleader ("Rule 22" and "Statutory"):

l) F.R.C.P. 22provides one means of bringing an interpleader action in

federal court. Allows stakeholder to assert a claim right in the stake in

addition to the "claimants". Drawback to proceeding under Rule 22: All

the normal limitations regarding personal and subject matter jurisdiction,

and venue, apply.

2) "Statutory Interpleader" under the Federal Interpleader Act: (liberal

approach) Facilitates bringing interpleader actions in federal courts by

loosening the traditional limitations on personal and diversity

jurisdiction, and venue. Courts have interpreted this Act as also allowing

the stakeholder to assert a claim in the stake as well as the "claimants".

Traditional Statuto 335

Amountin'n, $75,000.00 plus $500.00 minimum

Gontrovefslq

Diversity Complete Minimal (any 2 claimants)

Notice Strict - Territorial limits of the state Nationwide process

or state long arm Federal Long Arm

nue Normal venue rules apply Where any claimant resides

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 6

6. Class actions: This joinder device permits a lawsuit to be brought by a class representative

on behalf of large numbers of persons whose interests are sufficiently related so that it

serves the goal of judicial economy to adjudicate their rights and liabilities in one action.

a. To proceed as a class action, the court must, in its discretion, certify the action as

a class action at a certification hearing. Seven requirements must be satisfied:

l) An identifiable class: The class action complaint must contain a

description of the class which will permit the court to determine who

falls within the class and who doesn't. This is necessary to determine

who gets "notice" and who will be bound by the class action judgment

2) The class representative: Must be a member of the class

3) "Numerosity": The class must be large enough so that joinder of all

members as named parties is impracticable

4) "Commonality": The members of the class must share questions of law

or fact in common. In many jurisdictions, only one significant question

of law or fact will be sufficient

5) "Typicality": The claims or defenses of the class representative must

be typical of the members of the class

6) "Adequate representation": The class representative must adequately

represent and protect the interests of the class members.

NOTE: Even if the court finds, during the certification hearing, that the

class representative will adequately protect the class members' interests, if

in fact he does not provide adequate representation (e.g., inept conduct of

the litigation), then the class members, citing the Due Process Clause, may

not be bound by the class action judgment. HANSBERRY v. LEE

7) The class action must fit within at least one of the three types: (or

categories) of class actions:

a) "Prejudice" class action [Rule 23(bX1)]: Where the prosecution of

separate actions by the class members would create a substantial

risk of prejudice either (1) to other members of the class, not

parties to those actions, whose interests might be adversely

affected by those actions (e.g., where the class members are

claimants to a limited fund); or (2) to the defendant who could be

subjected to inconsistent judgments in those separate actions

b) "Injunctive" class action [Rule 23(b)(2)]: Where the defendant has

acted or refused to act on grounds generally applicable to the class

as a whole and the predominant relief sought by the class is final

injunctive relief or a corresponding declaratory judgment

c) "Damage" class action [Rule 23(bX3): Where the only relation

among the class members is that they claim to have been

damaged by defendant in a similar way and the predominant

relief sought by the class is damages. In order for the class action

to qualify as a "damage" class action, two additional

requirements must be satisfied:

(1) "Predominance": Common questions of law or fact

must predominate over questions affecting only

individual class members.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 7

(2) "Superiority": The court must determine that the class

action is superior to any other method (e.g., individual

actions) for resolving the controversy.

b. Notice reouirements

1) Required notice (strict): If the court certifies the class action as a

"Damage" class action [under Rule 23(b)(3)], then the court must

direct to the class members "the best notice practicable under the

circumstances, including individual notice to all members who can be

identified through reasonable effort. "

a) The class representative must bear the heavy expense of notice;

court cannot shift cost of notice to defendant.

b) The notice shall inform class members of their right to "opt

out" of the class, i.e., to terminate their involvement in the suit.

2) Discretionary notice: If the court certified the class action as a "Prejudice"

class action [under Rule 23(b)(1)] or an "Injunctive" class action [under

Rule 23(b)(2), then the method of notice is up to the court's discretion.

c. Subject matter jurisdiction requirements (Very testable crossover)

1) Diversity: Citizenship of the representative (not the class members)

controls in determining diversity.

2) Amount in controversy: Under case law existing prior to the enactment of

the Supplemental Jurisdiction provisions of the Judicial Improvements Act

of 1990, each individual class member's claim had to meet the $75,000

amount in controversy requirement (unless all claims could be aggregated

which was usually not allowed under the common law rules of aggregation).

In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court held EXXON CORP. V. ALLAPATTAH

SERVICES, that under the Supplemental Jurisdiction statute, supplemental

jurisdiction can be asserted over an individual class member's claim which

does not meet the amount in controversy requirement (assuming, of course,

complete diversity is satisfied) as long as a class representative's claim does

exceed $75,000.)

3) In 2005, Congress created the Class Action Fairness Act ("CAFA")

which amends both the diversity statute and the removal statute in big

multi-state class action suits. CAtr'A provides for "nunimal" diversily

in which any one member of the class (named or not) has diverse

citizenship from any one defendant and where the aggregate amount in

controversy exceeds $5 million. CAFA also expands removal

jurisdiction over class actions, in part, by eliminating, in removal of

class actions, the requirement, in diversity cases that no defendant may

be a citizen of the forum state.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 8

lt.

A. Purpose And Effect: Liberal federal discovery rules are designed to promote adjudication of

cases on the merits, rather than through the tactic of "surprise" (i.e., hiding evidence from the

adversary). Another purpose is to narrow the issues and to promote settlement (avoiding trial,

if possible, thereby promoting 'Judicial economy"). Facts placed in issue by the pleadings

may, after full and open disclosure of the evidence through discovery, not really be in dispute.

Hence, discovery may provide a basis for stipulations, settlements and summary judgment.

However, because of the nagging problem of continuing abuse of the discovery rules by

adversaries who employ these rules as litigation tactics, the Advisory Committee has added

F.R.C.P. 26(a) which provides for required disclosure of certain information.

"Disclosure" does not replace "Discovery" but is an additional requirement. It calls for

automatic exchange of specified categories of basic information by the parties to a federal

court lawsuit in three distinct stages corresponding to 26(a)(l), (a)(2) and (aX3).

This automatic "disclosure" obligation is not triggered by a discovery demand. Counsel, as

officers of the court, are required to comply with the demands of new Rule 26(a) without

awaiting discovery requests. The purpose behind this new "Disclosure" requirement is to cut

down on traditional "Discovery", and the interminable motion practice that accompanies it, to

save the parties and the court system time and money.

B. Automatic Disclosure:

l. Stage 1 - Initial disclosure under Rule 26(aX1): Rule 26(a) provides for three stages

of automatic disclosure. The first, under Rule 26(aX1), calls for the exchange of

basic, core information. It is, in effect, a kind of pre discovery, which, together with

the mandatory "meet and confer" conference under Rule 26(f), will (hopefully) cut

down on traditional discovery. NOTE: effective l2lll, Rule 26(a)(1) has been

amended to eliminate the ability to district courts to "opt out" of the required initial

disclosure rules. These amendments also changed the scope of initial disclosure as

follows:

' a. Subparagraph (aXlXA) requires disclosure of the identity of each individual

"likely to have discoverable information that the disclosing party may use to

support its claims or defenses, unless solely for impeachment.

b. Subparagraph (aXlXB) requires the disclosure of a copy, or a description, of

all documents, data compilations, and tangible things in a party's possession,

custody, or control and that the disclosing part may use to support its claims

or defenses, unless solely for impeachment.

E-DISCOVERY AMENDMENT: The category calted "data

ebftp,il4 th .b-oh-r.€iiltepd'ryitfi fi6rr:cs=te.Euif lle$,,.,=- ", '-;

'..

s,,lcironica .3torediinfo. lqd '{hiteinafter;:ffSili'} ig, 'alohg'=.=

with documents and tangible things, must be disclosed.

f,'leming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 9

c. Subparagraph (aXlXC) requires the disclosure of a computation of any category

of damages claimed and further requires that any supporting documentation and

other evidentiary material be made available for inspection and copying unless

privileged or otherwise protected from disclosure.

d. Subparagraph (aXlXD) requires disclosure of liability insurance agreements.

This provision converts the former "discovery" Rule 26(b)(2) which merely

allowed a party to request such information into a mandatory disclosure

requirement.

Timing of (aXl) disclosure: Disclosure under 26(a)(l) should take place at, or

within 14 days after, the mandatory "Meet and Confer" conference required

by Rule 26(f). At the "Meet and Confer" conference, the parties may agree to

extend the time for (aXl) disclosure.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 10

judg4ent that may be entered in the action or to indemnify or ieimburse for

payments made to satisfy the judgment. This discovery may include thi iaentity

of the carrier and the nature and limits of the coverage. A party may also obtain

discovery as to whethei ttrat insurance cairier is disputing the agreement'i

covgryge bf the claim ;nvolved'ihff ac,, ni but,'not ai to the nature1,5nd,.".., "

subsianceof that{isputeiInfoimatio6=-,c-@erxiug,theinsutlurceagieementisnot

,,by'f,+ason of disclosure athnissi'ble'in G* ehce:at,,trial.":Cal Code Ci*Proc,$,,. ..1

2011.210

The Economic Litigation Rules provide for a special discovery procedures simitar to

::

initid disclosuie, but avaiiable only in limited'.tivit cases (amoUnt in contioverSi

under $25,000):

. Reciprocal "case questionnaire": Plaintiff has the option to seive a case

., queslisnnaire on:the defendant at the startof titigat:ion which is designed to elicit

basic information about each partyts case, including names and addresses of all

5it*e$ses'ryith knowledge of $'i€levant fae$'li*,of alldocuurents relevant to ,,, ,,

. eca ;;itbtement o111r-e-rytur1anaam"!,3i'qffrnag;C;'*A,infsf,mation as to

.....:insurbncrecover4e;..iajuii*andtrea1ing.physicians.

2. Stage 2 - Disclosure under Rule 26(aX2): 26(a)(2) requires disclosure of the identity

of all persons who may offer expert testimony at trial (i.e., testifying expert trial

witnesses). Under old, unamended, Rule 26(b)(4XAXi), this information was

available only by serving interrogatories. Now, under 26(a)(2), the identity of expert

trial witnesses must be disclosed without waiting for a discovery request. 26(a)(2),

also requires, as to each expert witness who is "retained or specially employed" to

provide expert testimony at trial or whose duties as a party's employee regularly

involve giving expert testimony, the disclosure of a detailed report which contains the

opinions to be testified to, the grounds supporting those opinions, and details about

the expert witness' qualificatiohs and experience.

NOTE: Rule 26(b)(4), which used to provide very minimal protection to expert trial

witnesses from being deposed by requiring that interrogatories first be served and

answered and, afterwards, that a motion be made for further discovery, like deposing

the expert, has also been amended to allow routine deposition of expert witnesses

without seeking permission from the court.

Disclosure of expert trial witnesses is nol mandatory. A party seeking to discover the

opposing party's expert trial witnesses must serye a demand for exchange of expert

witness information:

CA RULE: "After the setting of the initial trial date for the action, any party may

obtain discovery by demanding that all parties simultaneously exchange

inform;tion conlCrniftg €a;:.h othtft$cxp€rf ial witnesses to 0l:lowing extClrt:

ihe

(a) Any party miy demand a mutual and simullaneous exchange by atl parties of a

list containing the name and address of any natural person, including one who is a

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 1L

p..-rty, whose,'oral-or@osition,testimont irt theform of,,ante*pert:, Iiinion any party

+$s,to btrir cnce at th$"F"= ,-..'.,

,.,

On;ni;.u"rt [esignati*.,brep"rty under subdivisiopLa).iq a purt Ji.a

employee of a party, or has been retained by a party for the purpose of forming and

:-fuiesws,Cn:oryrnion in 4nticipatioi oe tile titigtion or in preparation for the,,,triel,.,

ofitre uction, the designation of that witness shall include or be iccompanied by an

expert.witne*$d.iarati0[.under$ection2014.260;..::.

(c) Any party may ilso inctuOe a demand for the mutual and simultaneous

,produc,tion;fOiinip-ttion antl copyingof all discoverable r.-pgrts.*nd WritingS if

',.,

any, made by any eipert described in zubdivision (b) in the course of preparing that

expert's opinion.t'

3. Stage 3 - Disclosure under Rule 26(aX3):26(a)(3) requires disclosure shortly before trial

of the evidence (both testimonial and documentary) that each party may use at trial. For

many years prior to this amendment, pre-trial orders have routinely required parties to

exchange such information. 26(aX3) now incorporates such practice into the F.R.C.P.

26(a)(3) disclosure must occur at least 30 days before trial, unless changed by pretrial

order.

-

CA RULE: The compelled disclosure of the identity of nonexpert witnesses

intendedtobecalleilattriaIviolatesthiquaffiedworkproductprotection

doctrine." CITY OF LONG BEACH V. SL]PERIOR COURT. 64 CaI. App 3d 65.

Sorn-,supe*of courts hare,local rules that require paiii*t'exdangCir,qlldtiid .

.*itn€ases ln fuited'eitiliasesr,sny5arty=rnay $erve oh*e @ershordy, before

ffial a r*.q* ,'io iden-tify fu witn es,:wno-will.teSjify at t il, oth€f'thsn foii : ,' '

iinpeachm-nl-C*t€oAe Civ Froc,-$96(d;(Sbo.n C.'Litigaiionfur irnited Civil

Cases)

C. The Scope Of Discovery:

l. In general: NOTE - By amendment effective I2lW, Rule 26 (bxl) has been amended

to narrow the general scope of discovery, as follows: [F.R.C.P. 26(bX1)]: May

inquire into all non-privileged information that is "relevant to the claim or defense of

any party." For good cause, the court may order discovery of any matter relevant to

the subject matter involved in the action. Rule 26 (bxl) further provides that

"relevant information need not be admissible at the trial if the discovery appears

reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of admissible evidence."

a. Financial status: General rule - The financial worth of a party is normally not

relevant to the subject matter and, thus, not discoverable. Exception: Punitive

damages

b. Liability insurance coverage: Although not admissible at trial (because

normally irrelevant and prejudicial), the existence and scope of a liability

insurance policy is discoverable in most jurisdictions because such disclosure

of such information, on discovery, can promote settlement. F.R.C.P. 26(b)(2)

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure fI Page 12

has been amended so that the disclosure of liability insurance agreements

must be automatically disclosed under 26(aX1XD).

c. Privileged matter is not discoverable:

Examples

I ) Attorney-Client privilege

2) Confidential communications between spouses

3) Testimony against spouse

4) Privilege against Self-Incrimination

5) Doctor-Patient Privilege

d. CA RULE: NOTE: California has not followed the amendment to the

feileral niles,that nar..rowedthe scope of discovery toinfoffia.ti0n ,

Coraandiith'thisti .::'

*ni+irrty msy.ob'.t inldiScwely re r,ding:4,nJ mattcr, not pf,iVileg$that ds

relevant to the subjeci maner iivo,lied in the pending action or to the

determination of any motion made in that action, if the matter either is itself

admissible in evidence or appeair."asonably calculated to lead to the

discovery of admissible evidence. Diicovery may relate to the claim or

defenqe 'the'party sCekihg discoveryl,or,of auyothergar{;,to.dli!:action. .

Discovery may be obtained of the identity and location of persons having

*--*leitge,of.any, scovrCrCble'.rnat@ a-,'welt asd*'he'ixistence; deseription,

n-atuie, clrstody, conditiore, and location of any docurnent, {@gible,thihg, or

land or other property."

2. Proportionality Rule - Rule 26(b)(2): Allows court to limit discovery if the burden or

expense of the proposed discovery outweighs its likely benefit.

E-DISCOVERY AMEN DM E NT: Rule 26(b l(2, distinguishes between accessible

nSl ana ESI which is not reasonably accessible as follows: a party need not

provide discovery of ESI that the party identifies as "not reasonably accessible

because of undue burden or cost." On motion to compel, the burden of claiming

inaccessibility is on the claiming partJ. The burden of challenging the claim then

shifts to the requesting party who must show "good carse" for ordering

prduction

a

J. Trial preparation materials re: "Work Product" doctrine: IHICKMAN v. TAYLOR]

and codified in F.R.C.P. 26(bX3)1. Qualified immunity, meaning that work product

protection is not absolute (in contrast with the absolute protection afforded by

evidentiary privileges).

a. Elements which must be satisfied for "work product" protection:

1) Documents and other tangible things (e.g., reports, notes, memos,

witness statements, but note that one cannot ask an attorney to reveal his

mental impressions even though not contained in a document)

2) Prepared in anticipation of litigation

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 13

3) By or for a party or that party's representative (therefore, not only

attorneys can create protected work product; trial preparation materials

of a party or a party's representative, like an insurance claims agent,

also receive work product protection)

CA RULE: Requirements for CA 'kork product" protection: CA

case law applies a"derivativelnon-derivitive" test: to qualify as work

product, the material must be created by, or derived from, an

attorney's work on behalf of a client that reflects the attorney's

evaluation or interpretation of the law or facts (e.g., charts and

diagrams prepared for trial; compilations of entries in recordsl

appraisats, opinions, and reports of experts employed as consultants)

NOTE: (tntike federal work product rule,whichrequires the document

or other tangible thing to have been prepared "in anticipation of

litigation or for trialr" California case law applies work product

protection "to writings prepared by an attorney while acting in a

nonlitigation capacity." STATE COMP.INS. FUND V. SUP. CT.

(2001) 9l cA4th rom.)

Non-derivative Material:

Witness shtemcnts made'bf,,the'witne$s to th€ iilt€rviewing',;,. .,:;r .

attorney: Untit e the federal work product doctrine, witness

statements made by the witness to the interviewing attorney are

not protected as work product; these are considered non-

derivative, "evidentiilryr" material. However, such statements are

discoveiable for "good cauieo' (based on CCP$ 2031.010 et seq.,

where a demand for inspection has been refused, the demanding

party must show "specific facts showing good cause justifying

discoveiy" to obtain a court order compelling production). The

good cause showing is a lower standard than the "injustice or

unfair prejudice" showing required foi discovering non-mental

impressions work produiL To establish good sause, the requesting

party must show (1) a special necd foi discovery (e.g., to refresh

witness' memory) aid (2j the inability to obtain a similar

statement (e.g., can't locate witness or witnesi memory tral faaea).

NOTE: this is similar to the FRCP 26(bX3) requirement for

overcoming factual work product (substantial need + inability to

ffitai*imeubsf *i*rcaryut$haiashibt

The identity and location of witnesies, i.e., persons having

knowledge of relevant facts, are diicoverable.: NOTE: Under

FRCP 26{a),the identity and locaiions of "each individual likely to

have discoverable information that ihe disclosing party may use to

support its claims or defenses, unless solely for impe4chment" is

subjabt to',rb.Q-ifed$nitid) disblbsufn.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 14

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure tr Page 15

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 16

,these, d,piote as faetual. *b piodutf lnder th:Cft ileral'rules-)',,

and aiio includes photos or fihns that wiluld reveal an attorney's

mental impressions, conclusions or theories (e.g., by the camera angle

lir-o-sen bj.,thCatoine,.y:in fi ,$h-otogpaphl;-.r".

i

=,

c. Compare work product immunity with attorney client privilege: Attorney - Client

privilege protects confidential communications from client to his attorney

(benefits the client by encouraging full disclosure by client to attorney of

information necessary for sound legal counsel). In contrast, work product

immunity protects an attorney's trial preparation materials, not communications

between client and attorney (benefits the attorney by allowing him to prepare

case in privacy; deters "free-loading" by adversary).

d. The underlying facts and identity of witnesses, even though acquired by the

party in anticipation of litigation at great expense, are not protected from

discovery under the work product rule.

4. "Discovery of facts and opinions of experts [F.R.C.P. 26(b)(4)l

a. The facts and opinions of experts may be discovered only as follows:

1) "Testifying expert witnesses: Pursuant to amendment, effective llIl93,

F.R.C.P. 26(bX4XA) no longer provides any protection from discovery

for the facts and opinions of prospective expert trial witnesses, even if

they were acquired in anticipation of litigation or for trial. The

amended rule allows a party routinely to depose prospective expert

trial witnesses. Recall that, if the expert trial witness was "retained or

specially employed" to provide expert testimony or is a party's

employee whose duties regularly include giving expert testimony, a

detailed report must be prepared and disclosed under Rule 26(aX2). If

a report must be disclosed under 26(a)(2), amended Rule 26(b)(4XA)

requires that the deposition follow disclosure of the report."

2) Non-testifying expert "retained or specially employed in anticipation

of litigation or for trial:" Where an expert has been retained merely to

develop information or opinions to prepare for trial, but is not expected

to testify, the adversary can only discover such facts and opinions

upon motion and a showing of "exceptional circumstances". (Note: In

contrast with work product rule, which protects documents and other

tangible things but not the underlying facts, F.R.C.P. 26(b )(4) protects

an experts "facts and opinions" [whether or not contained in a report]

acquired in preparation for litigation.)

a) Examples of "exceptional circumstances": Monopolization of

qualified experts, or where the accident scene investigated by

an expert has been cleaned up.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 17

3) Casually or informally consulted expert: An expert who is only casually

or informally consulted in preparation for trial, but not retained or

specially employed, receives absolute protection, even as to his identity.

4) Protection of the intellectual property of an unretained expert: Rule 45

was amended in 1991 to provide protection for the opinions and

information of experts not prepared at the request of a party. Rule

a5(cX3XB)(ii) provides: "If a subpoena (ii) requires disclosure of an

unretained expert's opinion or information not describing specific

events or occurrences in dispute and resulting from the expert's study

made not at the request of any party the court may, to protect [the

expertl, quash or modify the subpoena or if the party in whose behalf

the subpoena is issued shows a substantial need for the testimony or

material that cannot be otherwise met without undue hardship and

assured that the [expert] will be reasonably compensated, the court

may order appearance or production only upon specified conditions."

D. Soecific Discoverv Devices:

1. Oral depositions IF.R.C.P. 301: An oral deposition is the testimony of a witness out-of-

court before an official who is empowered to administer an oath, by a party who has

given notice to all other parties so that they can be present to cross examine the deponent.

a. As a general rule, any party may take the deposition of any witness, either

party or nonparty, after the commencement of the action.

l) The number of depositions (both "oral" and "written" together) each

side can take is limited to 10 per side. Leave of court or agreement of

the parties is required before all plaintiffs, all defendants or all third

party defendants can take more than ten depositions.

2) Leave of court is now also required to depose a person who has

already been deposed in the action

3) Normally, discovery, including depositions, may not commence until

the parties meet and confer to plan their discovery. Such a meeting is

required in every action under Rule 26 (f). Therefore, in order to take

the deposition of either a party or a non-party before the Rule 26(0

conference, leave ofcourt is required, unless the person to be

examined is about to become unavailable for examination in the U.S.

4) The party noticing the deposition may, without leave of court or

agreement of the parties, record the deposition non-stenographically

5) NOTE: By amendment effective 1210I, "a deposition is limited to one

day of seven hours unless otherwise authorized by the court or agreed

by the parties."

b. Notice: The deposing party must give written notice to every other party,

. identifying the deponent and the time and place of the deposition. If a party

was not present or represented at the taking of the deposition or did not

f,'lemingos Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 18

receive reasonable notice, the deposition cannot be used against that party as

evidence at trial.

c. Place: In federal practice, a nonparty witness who has been subpoenaed may

be required to attend a deposition at any place within 100 miles from the place

where that person resides, is employed or transacts business in person, or is

served, or at such other convenient place as it fixed by order ofthe court.

F.R.C.P. a5(cX3XAX 1 1).

d. Deposition of a party witness: Notice of deposition is all that is required to

depose a party witness.

e. Deposition of a nonparty witness: In addition to the service of a notice of

deposition on all parties, the nonparty witness should be subpoenaed.

Deposition of a corporation: Where a corporation, association or governmental

body is a deponent, the adversary need not identify the particular individual who

must appear to give testimony. The notice of deposition need only name the

corporation and describe with reasonable particularity the matters on which

examination is requested. The corporation must then designate the appropriate

witness who will testify at the deposition on behalf of the corporation. The

corporation will be bound by its deponent's answers.

b' Documents: The deposing party may require the deponent to bring with him to the

(}

deposition relevant documents and tangible things in his possession. If the

deponent is a party, the notice of deposition shall contain a request for such

material, identified with reasonable particularity. If the deponent is a nonparty

witness, he should be served with a subpoena duces tecum which is court process

that commands the deponent to bring with him documents and tangible things

identified with reasonable particularity in the subpoena duces tecum

h. Use of deposition as evidence at trial [F.R.C.P. 32]: (Evidence crossover) The

problem here is that deposition testimony is made "out of court" ando thus,

raises "hearsay" issues if sought to be admitted as evidence at trial.

1) The deposition of a party or nonparty witness may be used for the

purpose of contradicting or impeaching the testimony of the deponent

as a trial witness.

2) The deposition of a party witness may be used for any purpose allowed

by the rules of evidence. Example: Party admission - any relevant

statement of an opposing party (e.g., deposition testimony) can be

introduced at trial to prove the truth of the matter asserted in the

statement, whether or not that party takes the witness stand at trial.

Theory: let the party who made the admission explain it in court. Note:

A party admission is just "evidentiary", i.e., it can be used as evidence

but it does not knock the issue admitted out of the case. By contrast,

see Effect of Rule 36 Admission, Section X, infra, atpage 45.

3) The deposition of a nonparty may be used as affirmative evidence if

the deponent is "unavailable", e.g., dead, ill, incompetent or beyond

the subpoena power of the court.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 19

i. NOTE: Effective l2l0l, rule 30 was amended to provide the court specific

authority to impose appropriate sanctions upon persons whose conduct impeded,

delayed or frustrated the fair examination of the deponent. See Rule 30 (dX3).

2. Written depositions [F.R.C.P. 31]: The deposing party submits, in advance, written

questions (along with written cross-examination questions of the other parties) which

an officer of the court puts to the deponent orally. The deponent answers orally, under

oath, and the answers are recorded. Much less effective than oral depositions because

there is no opportunity to frame follow-up questions (and cross-examination

questions) in light of answers to previous questions.

Interrogatories [F.R.C.P. 33]: Interrogatories are sets of written questions submitted by

ono party to another party requiring an answer by the party in writing under oath, unless

the question is objected to in which event the reasons for the objection shall be stated in

lieu of an answer. Rule 33 limits the number of interrogatories each party may serve to

25, including all discrete subparts. This number may be increased by leave of court.

a. Who may serve and be served: Any party may propound any number of

interrogatories to any other party. Non-parties cannot be served with

interrogatories. Interrogatories can be served by upon the plaintiff at any time

after commencement of the action and upon any other party after service of the

summons and complaint upon that party.

b. Duty to investigate: Interrogatories require the answering party to provide

such information as is available to the party (whether or not within the

personal knowledge of the party). The answering party is under a "duty of

reasonable inquiry" to undertake "simple investigatory procedures not

requiring undue burden or expense".

NOTE: Corporate duty - (re: corporate knowledge). Corporate parties are

required to undertake more extensive investigation in order to fully answer.

"Corporate knowledge" is held to include the collective knowledge of all

managers and important agents of the corporation.

c. Option to produce business records: Gives a party to whom interrogatories are

propounded the option to produce business records, in lieu of answering, if an

answer can be supplied only by extensive searching of the answering party's

records. Note, however, that this rule may not be used in bad faith merely to

shift the burden of the answering party back to the inquirer.

d. Failure to make adequate responses: Under F.R.C.P. 37(a), an evasive answer

is deemed to be a failure to answer. Hence, if an answer is incomplete or

evasive, the court may, on motion to compel [F.R.C.P. 37(a)], order the

responding party to answer more fully.

e. Use of interrogatory answers as evidence at trial: (Evidence crossover) As

with deposition testimony, interrogatory answers are out-of-court declarations

and, thus, ifthey are offered into evidence at trial, hearsay issues are raised.

The following hearsay exclusions or exceptions permit the use of

interrogatory answers as evidencei

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 20

1) Party admission: any relevant statement contained in an interrogatory

answer can be used by an opposing party as evidence at trial to prove

the truth of the matter asserted in the statement. A party admission is

only an evidentiary admission, i.e., it does not knock the fact admitted

out ofthe case as an issue.

2) Impeachment prior inconsistent statement: An interrogatory answer of

a party which is inconsistent with the testimony of that party as a

witness on the stand may be admitted into evidence to impeach that

witness's testimony.

E-DISCOVERY AMENDMENT: The 2006 e-discovery amendment to Rule

33,allows roduction of ESt in response to an interrogatory IF 'the buiden of

deriving ot ascertaining the answer is substantially the same for the party

serving ihC interrogatory as for the party served."

4. Request for admission [F.R.C.P. 36]: At any time during discovery, a party may serve

upon any other party a written request to admit to the truth of any relevant matters set

forth in the request that relate to statements or opinions of fact or of the application of

law to fact, including the genuineness of any documents described in the request. This

tends to expedite trial preparation in that it naffows the field of issues in controversy.

a. Effect of admission: An admission in response to a request for admission is a

"judicial" admission, i.e., it conclusively establishes the matter admitted for

pulposes of the pending matter. The matter admitted is no longer a disputed

issue in the case; the responding party cannot introduce evidence at trial to

controvert the matter admitted.

b. Failure to respond: If there is not timely response to the request, the matter is

deemed admitted.

c. Motion to withdraw or amend an admission: The court has the discretion, upon

motion, to permit withdrawal or amendment of an admission "when the

presentation of the merits of the action will be subserved thereby and the party

who obtained the admission fails to satisfy the court that withdrawal or amendment

will prejudice that party in maintaining the action or defense on the merits."

d. False denial: If the responding party denies a matter which, in good faith, he

should have admitted, the responding party may be liable to reimburse the

requesting party for the full costs of proof on that issue at trial.

"ff a party to whom requests for admission are directed fails to serve a timely

r@onse,:.. . {b} uestirtg pa$J nay.mbve,for:eh,order thCt the

genuineness of any documents and the truth of any matters speeified in the

requests be deemed admitted, as well as for a monetary sanction under

Chapter 7 {com mencing with Secti,on ?"023.0 lU."

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 21

5. Request for production of documents and things and entry upon land for inspection

and other purposes IF.R.C.P. 341: At any time during discovery. a party may request

any other party to produce for copying or inspection relevant documents and tangible

things in the possession, custody or control of the responding party. Also, a party may

request entry upon designated land or other property in the possession or control of

the responding party for the pulpose of inspection and measuring, surveying,

photographing, testing or sampling the property.

a. Designation of items - Time, place and manner: The request shall set forth the

items to be inspected either by individual item or by category, and describe each

item and category with "reasonable particularity". The request shall specify a

reasonable time, place and manner of making the inspection.

b. "Possession, custody or control": The responding party need only produce

items which are in his possession, custody or control. The responding party

has a duty to use his influence to obtain the requested items.

SOCIETE INTERNATIONALE V. ROGERS

c. Materials in possession of a nonparty: F.R.C.P. 34 may not be used to reach

materials in the possession of a nonparty. Such material must be reached by

subpoena duces tecum.

E- b-f SCOV*Y AM ENDM ENT -he ioOe d--on-ry amendmert to Rule 3 provid-i

tha,t a,,par.tj may,sefVe.:a reQuest:'to.:,inSpect, coPjo te r,sarnple dti. ents or

elecmniial.ly ito;,red infoT.marton . . ;' i).The rule now allows a party to "test sample" ESI

and allows access to the responding party's computer network subjeit lo reasonableness.

The request may specify the form or forms in which ESI is to be produced. The

responding party may then object to the requested form of production or, if no form of

production is requested, the responding party must state the form or forms it intends to

usei If the'iequesl doesnot s cify th€'form(S) of prducfion;.the iesp ndingparly must

produce fisl as oidinarily:, -intained or in reasonabty uiCbleform(s. .'Finally, the

responding patt5r,,s"u6 not,.pf.oduc€ the same ESI in mofe than one form.

6. Physical or mental examinations [F.R.C.P. 35]: When the mental or physical condition

(including the blood group) of a party, or of a person in the custody or under the legal

control of a party, is in controversy, upon motion and for good cause shown, the court

may order that party (or person) to submit to a mental or physical examination.

a. Motion required. This is the only federal discovery device, which requires a

motion to the court in the first instance. All other devices are "on notice".

b. Persons subject to examination: Only parties or persons in the custody or under

the legal control of a party are subject to examination. The latter refers to minor

children or legally incompetent adults who are represented in court by guardians.

Employees are not in the "custody or legal confol" of their employers.

c. Specific mental or physical condition must be "in controversy":

1) Where a party plabes his own mental or physical condition "in issue",

that condition is "in controversy" for purposes of Rule 35 and the court

will order an exam appropriate to that condition. Example: P sues D

for whiplash in auto accident suit. D moves for examination of P's

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 22

back, affixing a copy of P's complaint to his moving papers. P's back

condition is "in controversy".

2) Where the moving party places another party's condition in issue, the

moving party must make an evidentiary showing that the responding party

may well have a specific condition appropriate to the examination

requested. Movant can't use Rule 35 to go on "fishing expedition", hoping

to discover, through a battery of exams, a relevant condition.

Example: Bus rear ends a tractor-trailer. In suit by bus passenger against

bus driver, passenger moves to compel driver to submit to an eye exam.

Affidavit of another driver, driving in same direction as bus, affirming that

he saw the red brake lights of the tractor-trailer a half mile before bus

driver is sufficient to place driver's eyesight "in controversy".

SCHLAGENHAUF V. HOLDER

a) An examination cannot be compelled merely to test the

eyesight or mental or physical condition of an eyewitness for

impeachment purposes.

3) "Good cause": Court must find that the moving party cannot obtain the

necessary information from other sources, e.g., previous examinations of

the same condition by other doctors where there is no reason to doubt

their reliability.

4) Exchange of medical information: The examined party has a right to

receive a copy of the results of the compelled examination and of any

earlier reports on the same condition in the hands of the opposition.

However, by making such a request, the examined party must deliver to the

opposition, upon request, reports by his own doctors regarding the same

condition, (thereby waiving his evidentiary doctor-patient privilege).

,CA:nH[Rur$ ,,rn G iiea ciut c*ss - ueon t iiiig,itiqn Rul.t

Eiommic:Liiigation Rules limit discovery in Limitd Civil Cases (*nCer $25,000) in

order to reduce the cost of litigation in small cases. Under these rules:

. Each party is limited tn one oral deposition.

.,' {'Gmbba$'f le.M,,S.so? a-h-party mayserve onleach adir:rse pertyno rnore

than 35 of any combination of interrogatories, requests for admission or

dcmandsforinspection.Subpartsarenotallowed.

. No limit on physical, mental and blood examinations, or on discovery of the

identity of the opposing party?s expert witnesseJ

E. Protective Orders: Upon motion, and for good cause shown, the court, in its discretion, may

make any order which justice so requires to protect a party from "annoyance, embarrassment,

oppression or undue burden or expense", including preventing or limiting discovery. The court

has maximum flexibility in fashioning an order that strikes a balance between the burden on

the moving party and the need of the responding party for the information he seeks to discover.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 23

1. Inconvenient place of deposition

a. Nonresident defendant: Upon an application for a protective order, courts are

inclined to hold that a nonresident defendant should be deposed at his

residence rather than where the suit is pending.

b. Nonresident plaintiff: Courts are more inclined to require a nonresident

plaintiff to appear in the local forum since he chose to file his action therein.

2. Deponent too ill to attend deposition

3. Deposition questions limited only to certain matters

4. Unreasonable conduct of deposition

5. Unnecessary deposition

6. Burdensome interrogatories: If interrogatories are unnecessarily numerous,

overbroad, or costly to answer, the court may order that they be redrafted, or excuse

the opposing party from answering.

7. Confidential information: Protective orders may issue to prevent unnecessary exposure of

personal matters, or to require that the deposition be taken privately and sealed.

8. Trade secrets: Other secrets, such as business or trade secrets, may be protected from

unnecessary or irrelevant disclosure.

F. Sanctions:

l. Motion to compel (where responding party fails to answer) [F.R.C.P. 37(a\]: Where

deponent refuses to answer a question, where an interrogatory is objected to rather

than answered, or where a request for a document is refused, the discovering party

may move for an order compelling discovery.

2. Sanctions for failure to comply with court order IF.R.C.P. 37(b)l:

a. If a nonparty fails to obey a Rule 37(a) court order directing him to answer, he

may be held in contempt.

b. Under Rule 37(b), if a party fails to obey a Rule 37(a) court order directing him to

answer, the court may make such orders "as are just", including the following:

1) An establishment preclusion order that certain facts shall be taken to

be established for the purposes of the action in accordance with the

claim of the party obtaining the order.

2) An order refusing to allow the disobedient party to support or oppose

designated claims or defenses, or prohibiting that party from

introducing designated matters in evidence;

3) An order striking out pleadings, or staying proceedings until the order

is obeyed, or dismissing the action or rendering a default judgment

against the disobedient party;

4) In lieu of the above, or in addition, disobedient party may be held in

contempt.

5) In lieu of the above, or in addition, the court shall order the disobedient

party and/or his attorney to pay reasonable expenses caused by the failure

to obey.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure ll Page 24

c. In'deciding which sanction to impose under Rule 37(b), the court has wide

discretion to adjust the severity of the sanction to fit the importance of the

discovery sought and the reason for refusal. The harshest sanctions are

imposed for the most flagrant cases of disobedience. The severest sanctions,

such as dismissal, default judgment and, to some extent, an establishment

preclusion order, will not be upheld on appeal without a showing of a willful

failure to comply. Note: Negligence is generally the defense.

d. Sanctions for untruthfully denying a request to admit: Denying party must pay

cost to prove the matter involved.

Sanctions for filing a meritless claim: Rule 1 1 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure authorizes federal courts to impose sanctions only on the attorney

who signs the papers in a meritless claim, and not on the law firm.

3. Sanctions for failure to disclose under Rule 26 (a):

a. Rule 37(c)(1) provides that a party may not offer as evidence information which,

without substantial justification, was not included in the initial disclosure

{(26(aXl)}, unless the failure to disclose was harmless. The court may award

other sanctions in addition to, or in lieu of, this newly available sanction.

E-DISCOVERY AMENDMENT: The 2006 e-discovery amendment to Rule 37(f)

relates to the issue of document retention by providit g thut, absent exceptional

circumstances, a coart, ay otirnpose sanctions fof,fnlling to prq,ylde 8SI losf as a

iesult'of routine, god.faithoperation,of an electronic information systern.

G. Pretrial Conference: The purposes of the pretrial conference is to promote settlement

(thereby avoiding trial) or, if settlement is not possible, then to streamline the trial by

narrowing the issues (thereby shortening the trial), sharpening the issues to be tried, and

establishing an agenda for trial which will reduce the likelihood of surprise.

1 Pretrial order - Formal order containing matters agreed upon at the pretrial conference:

a. Supersedes the pleadings

b. Shall be modified "only to prevent manifest injustice"

c. Matters not included in order may be admissible in court if introduced and not

objected to in a timely manner

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007\ Civil Procedure II Page 25

III. PRE.TRIAL DISPOSITION

A. Default Judgment:

1. When a pafty against whom a judgment for affirmative relief is sought fails to plead

to the complaint or otherwise fails to contest the action, a default may be entered

against him. The default judgment may be entered either

a. By the clerk where the damages demanded in the complaint are for a "sum

certain" and defendant has not appeared [F.R.C.P. 55(bXl)], or

b. By the court in all other circumstances [F.R.C.P. 55(bX2)]

2. Right to Notice and Hearing Before Entry of Default Judgment

a. Where the amount of damages is unliquidated, the court will hold a hearing to

assess damages.

b. Notice to defaulting party: If the defaulting party has "appeared" in the action,

he must receive notice of the hearing at least three days prior to that hearing.

F.R.C.P.55(b)(2). Appearance means some conduct by the defaulting party by

which he shows some interest in defending the suit. He may then attend the

hearing and contest the amount, extent or type of relief sought or challenge the

entry of a default judgment altogether.

3. In light of the general preference for a full adjudication of cases "on the merits",

courts have the discretion not to enter a default judgment (or to set one aside, under

Rule 60(b), for a variety of reasons which include the following:

a. Defendant may have a meritorious case

b. "Excusable neglect"

c. The amounts involved or the issues at stake are great

4. Default judgments can also be entered as a sanction for disobeying a court order.

5. Once entered, and if not set aside [under Rule 60(b)], a default judgment carries all

the res judicata effect of a judgment upon the merits. A valid default judgment must

be enforced by sister-state courts under the Full Faith and Credit Clause, like any

other valid judgment on the merits. A default judgment can, however, be collaterally

attacked for lack of personal jurisdiction.

B. Voluntary Dismissal [F.R.C.P. 4l(a)]:

1. Notice of dismissal: Plaintiff retains the right to dismiss his own action by filing a

notice of dismissal. However, notice must be filed before the filing of the adversary's

answer or motion for summary judgment. Thereafter, plaintiff cannot dismiss without

defendant's consent or leave of court. The dismissal is without prejudice unless the

plaintiff has once before dismissed the same action based on the same claim.

2. By leave of court: A court may grant plaintiff s motion for leave to dismiss on such

terms and conditions as the court deems proper. Unless otherwise stated, such dismissal

is without prejudice.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure tr Page 26

C. Involuntary Dismissal [F.R.C.P. a1(b)]:

1. Before trial: Like a default judgment against a defendant, an involuntary dismissal

may be imposed on a plaintiff as a sanction for failure to comply with procedural

rules or orders. For example:

a. Failure to comply with a discovery order

b. Failure to amend pleadings within the time permitted after the nlotion to

dismiss for failure to state a claim (or demurrer) is granted

c. Failure of the plaintiff to appear at a pretrial conference

d. Failure to prosecute the action with "due diligence"

NOTE: A disciplinary dismissal is a harsh sanction in that it is a dismissal without

trial and carries full res judicata effect, unless the court specifies otherwise. Note: An

involuntary dismissal for lack of jurisdiction, improper venue or failure to join an

indispensable party does not have res judicata effect.

2. At trial: In an action tried without a jury, the court will, on proper motion, dismiss the

action at the close of the plaintiffs evidence if, on the facts and the law, no right to

relief is shown. Such a dismissal is a disposition on the merits.

D. Consent Judgment: (stipulated judgment) A court judgment which embodies the terms of a

settlement agreement between the parties.

E. Motion For Summary Judgment [F.R.C.P. 56]: (Testable)

t. Purpose: To determine whether a trial is necessary; whether there are disputed fact issues

for a jury to determine. In contrast with a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim (and

a motion for judgment on the pleadings), a summary judgment motion looks behind the

pleadings.

2. Test: Summary judgment shall be granted if there is "no genuine issue as to any

material fact" and, on the basis of the undisputed facts, the moving party is entitled to

a judgment as a matter of law.

-1- Procedure:

a. Movant's burden: The moving party has the initial burden to show that there is no

genuine issue as to a material fact. If he fails to meet that burden, his motion must

be denied (even if the respondent has submitted no evidence to show that a

genuine issue does exist). In attempting to meet his movant's burden, the moving

party may submit the pleadings, deposition transcripts, interrogatory answers,

admissions and affidavits made on personal knowledge.

b. Respondent's burden: If the moving party meets his burden, then the burden

shifts to the respondent to set forth specific facts showing that there is a genuine

issue for trial. If respondent fails to meet this burden, the court will grant

summary judgment. In attempting to meet his burden, respondent may submit

counter affidavits and discovery materials; however, he may not rest upon the

mere allegations of his pleadings (if respondent is the plaintiff) or upon the

denials in his answer (if respondent is the defendant).

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 27

c. A11 issues of credibility and all reasonable inferences are to be resolved in

favor of the non-moving party.

d. Effect: Summary judgment discourages frivolous suits and is used to prevent

very clear one-sided cases from going to trial.

e. Partial Summary Judgment: A partial summary judgment may be granted on

one claim (where multiple claims have been joined in one suit) or on the issue

of liability alone, leaving for trial the determination of damages. If summary

judgment is not rendered on the whole action, the court may make an order

specifying those facts that appear to be without substantial controversy.

CA Rule: As of 2001, the California Supreme Court has held that "zummary

judgment taw in this state now conforms, largely but not completely, to its

federal counterpart." AGUILAR V. ATLANTIC RICHFIELD CO., (2001)

25 C4th 826. Thus, in California. as in federal court under CELOTEX.

where the plaintiff has the burden of production at trial, the moving

defendant can meet its movant's burden of production to show "no genuine

issue as to a material fact" by sho*ing that the plaintiff lacks evidence to

meet its burden of production at trial. To make this showing, the defendant

,cann6i sinn$ty assert,that plaffitr has,n-o evid-nee,'but must affirmatively

show'an absencedevidence'by'the plaintiff, e.g., through,plaintiff's i. ,,1'

admissions, deposition testimony of plaintiff's own witnesses

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 28

IV. JURY TRIAL

A. Right To Trial By Jury:

1. Sources of the right: There are two major sources of the right to a jury rial in federal

court:

a. The Seventh Amendment is the federal constitutional source of the right to a jury

trial. Although it is not applicable to the states in civil actions, most state

constitutions contain similar provisions providing for jury trials in civil actions.

b. Some federal statutes creating federal causes of action expressly provide for a

jury trial.

2. "Historical Test": The Seventh Amendment states: "In suits at common law, where the

value in controversy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury shall be

preserved ..." This means that a party has the constitutional right to have all issues

relating to claims triable in a common law court tried by a jury ("legal" issues).

There is no right to have issues relating to equitable claims ("equitable" issues) tried by a

jury. The most important factor in characteizing a claim as legal or equitable is the

remedy sought. Hence, a claim for damages is generally considered "legal", whereas a

claim for injunction, rescission, specific performance or other "equitable" remedies is

considered "equitable".

a

J. BEACON THEATRES.INC. v. WESTOVER (1959) and its progeny:

a. BEACON THEATRES. INC. v. WESTOVER: In a case containing both

"legal" and "equitable" claims, issues that are common to these legal and

equitable claims must be tried first to a jury.

b. DAIRY QUEEN,INC. v. WOOD (1962):

1) This case brought about the demise of "clean-up" doctrine under which

legal issues which were "incidental" to an essentially equitable case were

tried to the court. DAIRY QUEEN held that issues common to equitable

and legal claims must be tried first to a jury, even if legal claims are

"incidental" to equitable claims.

2) In determining whether to characterize a claim as "legal" or

"equitable", the court can consider procedural developments since

1791. Thus, a claim for an "accounting", though historically an

equitable remedy, was recharacterized, in DAIRY QUEEN, as a

"legal" claim because it is similar to a damage remedy and a federal

court today, under F.R.C.P. 53(b), can appoint a special master to

assist the jury in computing complex damage awards.

c. ROSS v. BERNHARD (1970): Where procedures historically available only

in a court of equity are used as a vehicle to assert "legal claims", the

underlying legal issues should be tried to a jury. Thus, in a stockholder

. derivative suit asserting a legal claim for damages, issues relating to the

substantive legal claim must be tried to a jury, even though the stockholder

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007') Civil Procedure II Page 29

derivative suit historically could only be brought in an equity court. The court

looked to the "heart of the action", which was a legal claim for damages.

d. New statutory causes of action:

1) CURTIS v. LOETHBR (1974): Where Congress has created a new

statutory right, nonexistent in 1791, the statutory right must be

analogized to legal or equitable rights that were in existence in ll9l.

Thus, a claim for damages in a suit brought under the federal Civil

Rights Act of 1968 was analogized to a "legal" right because the damage

remedy was the traditional form of relief offered in common law courts.

2) ATLAS ROOFING COMPANY v. OCCUPATIONAL SAFETY &

HEALTH REVIEW COMMISSION (197 7); GRANFINANCIERA'

S.A. NORDBERG (1989): Where Congress has created a new statutory

"public" right closely intertwined with a federal regulatory program and

has provided for its enforcement in an administrative agency or a

specialized court (e.g., Bankruptcy Court), which function without juries,

the Seventh Amendment does not require a jury trial. Rationale: Congress

has the power to assign adjudication of "public" statutory rights to an

agency tribunal or specialized court for speedy determination by a

specialized group of experts.

4. Asserting the right to a jury trial and waiver: In federal court, a party who wants a

jury trial of an issue must affirmatively assert his jury trial right "by serving upon the

other parties a demand therefore in writing at any time after the commencement of the

action and not later than 10 days after the service of the last pleading directed to such

issue." Failure to do so will result in a waiver of the jury trial right. F.R.C.P. 38.

CA RULE: Unlike federal eour! where the demand for a jury triat of an issue must be

made early in the lawsuit, i.e., in writing and no later than 10 days after the service_of

the,la*t ple*fingdfccted to s-de$,idcue'in',Cditg no,particular fo ,of demand is ,

required; the demand could be made orallyfor the first time at a case management

:confer+ntC. Tha,iiEhi to,a juty tritfis waitpd if no,,dehand is made by the time the case

is first set for trial.-

B. Jury Selection: The 14th Amendment's Equal Protection Clause prohibits systematic

exclusions and arbitrary discrimination of minorities and women in jury selection.

C. Voir Dire Examination Of Jurors: Attorneys/Judges conduct an investigation to see if each

juror will be fair, impartial and unbiased.

1. Challenge for cause: Any juror who shows bias or an interest in the outcome of the case

can be excused for cause, and there is no limit to the number of such challenges a party

can make.

2. Peremptory challenges: Each party is entitled to a limited number of challenges

without showing cause (cannot be based on race or sex).

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 30

D. Comments By Trial Judge: The federal rules permit a trial judge to comment to the jury on

the quality of the proof presented which bears on the issues that the jury is to decide,

provided that he informs the jury that it, not he, is the decision maker.

E. Jury Instructions: While the ultimate responsibility for jury instructions rests with the

judge, counsel for each side may submit jury instructions to the judge who will decide

whether or not to submit such instructions to the jury. General rule - A failure to request an

omitted instruction or to object to an instruction results in a waiver. An erroneous or

insufficient instruction, even if properly challenged, will not lead to a reversal unless it

results in a prejudicial error.

F. Verdicts: (federal practice requires unanimous verdicts)

1. General verdict: The jury finds for either plaintiff or defendant but does not disclose

the grounds for the verdict.

2. Special verdict: A special verdict consists of the jury's answers to specific factual

questions on which it is instructed to make findings. The judge then applies the law to

the jury's findings of fact and enters the appropriate judgment.

3. General verdict with written interrogatories: The jury is asked to give a general

verdict and also to answer specific questions concerning the ultimate facts of the case,

so that the basis for that verdict is disclosed.

Fleming's Fundamentals Of Law (@ 2007) Civil Procedure II Page 31

V.

MOTIONS AFTER VERDICT

A. Motion For Directed Verdict. Now Called Motion For Judgment As A Matter Of Law:

In 1991, F.R.C.P. 50 amended to eliminate the terms "Directed Verdict" and "Judgment

Notwithstanding the Verdict." Each of these are now called "Motion for Judgment as a Matter

of Law." In addition, the 1991 amendment eliminated the requirement that the moving party

had to wait until the close of the opposing party's case. Under the amendment the motion can