Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

66 viewsBlue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim A

Blue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim A

Uploaded by

Rose Emmanuelle GarciaThis summary provides the key details from the document in 3 sentences:

Babo, the narrator's aunt, brings the young orphan boy to live with the wealthy Datu's family in hopes he will be cared for, as she is too poor to support them both. Upon arriving, the boy is nervous but intrigued by the Datu's daughter who laughs at his harelip. Babo ensures the boy understands the proper etiquette for interacting with the noble family and reassures him that he will be happy living with them, though he worries about missing Babo.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Daddys Little PetDocument8 pagesDaddys Little PetLovelessNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument4 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaCarla ArceNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument6 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaFranchesca Nicole CalmaNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument9 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanahIgh QuaLIty SVTNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument12 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaCarl Gabriel Calpe CulveraNo ratings yet

- Literary PiecesDocument8 pagesLiterary PiecesAlyssa VerdijoNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument11 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaBeatrix Medina100% (1)

- Blue Blood of Big AstanaDocument8 pagesBlue Blood of Big AstanaAdrian EstrelladoNo ratings yet

- Blue BloodDocument7 pagesBlue Bloodjean magallonesNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim JubairaDocument12 pagesBlue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim Jubairaramy hinolanNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument12 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaJustine Roice MorenoNo ratings yet

- Ibrahim Jubaira Is Perhaps The Best Known of The Older Generation of English LanguageDocument10 pagesIbrahim Jubaira Is Perhaps The Best Known of The Older Generation of English Languagesalack cosainNo ratings yet

- The Rhyme of The Ancient Barbie in Five PartsDocument6 pagesThe Rhyme of The Ancient Barbie in Five PartsAdam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Summer at the Cornish Farmhouse: Escape to Cornwall in 2024 with this absolutely feel-good romantic read!From EverandSummer at the Cornish Farmhouse: Escape to Cornwall in 2024 with this absolutely feel-good romantic read!No ratings yet

- Little Boy 'S Love For His Family I: MoralDocument3 pagesLittle Boy 'S Love For His Family I: MoralKajal GadeNo ratings yet

- Before Women Had WingsDocument5 pagesBefore Women Had WingsGianna RamirezNo ratings yet

- PDF of Masse Und Meinung Gabriel Tarde Full Chapter EbookDocument69 pagesPDF of Masse Und Meinung Gabriel Tarde Full Chapter Ebookphilispalae425100% (6)

- Kitten's New Collar: A Razor's Edge Daddy Dom Erotica ShortFrom EverandKitten's New Collar: A Razor's Edge Daddy Dom Erotica ShortNo ratings yet

- Buck Me Cowboy: A Secret Baby Western RomanceFrom EverandBuck Me Cowboy: A Secret Baby Western RomanceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- Abe by Jeff LockerDocument7 pagesAbe by Jeff LockerGizelaNo ratings yet

- DeclamationDocument9 pagesDeclamationIlham Jhann AcramanNo ratings yet

- Jambo Youth Issue 58Document2 pagesJambo Youth Issue 58ShyjanNo ratings yet

- A Fool Not To FuckDocument29 pagesA Fool Not To Fuckkadas alkadasNo ratings yet

- High - School DXD Volume - 4 - Ichiei IshibumiDocument268 pagesHigh - School DXD Volume - 4 - Ichiei Ishibumiashlynx.No ratings yet

- Download ebook pdf of От Arpanet До Internet 1St Edition Коллектив Авторов full chapterDocument24 pagesDownload ebook pdf of От Arpanet До Internet 1St Edition Коллектив Авторов full chapternkqayielhamm100% (12)

- A Reincarnated Mage's Volume 1Document125 pagesA Reincarnated Mage's Volume 1Addiedom BiacoloNo ratings yet

- Literary Works From The Mindanao Literature From The Past and The Present Time-1Document11 pagesLiterary Works From The Mindanao Literature From The Past and The Present Time-1Pascual GarciaNo ratings yet

- Life From The River by Jan HudsonDocument3 pagesLife From The River by Jan HudsonMiguel GutierrezNo ratings yet

- OceanofPDF - Com Our Family Secret - Savannah BrooksDocument118 pagesOceanofPDF - Com Our Family Secret - Savannah BrooksJessicaNo ratings yet

- Push The Envelope Draft 1Document63 pagesPush The Envelope Draft 1Marlaine AmbataNo ratings yet

- Why Does My Grandfather, Charles Darwin, Act So Strangely?: As Told by Bernard DarwinFrom EverandWhy Does My Grandfather, Charles Darwin, Act So Strangely?: As Told by Bernard DarwinNo ratings yet

- Que Tienes ?: Como Estas ?Document8 pagesQue Tienes ?: Como Estas ?JONNATHAN LOZADANo ratings yet

- 11 Physics Chapter 14 and 15 Assignment 5Document2 pages11 Physics Chapter 14 and 15 Assignment 5Mohd UvaisNo ratings yet

- 2024 Base Merit Brochure EditedDocument2 pages2024 Base Merit Brochure EditedImee Kaye RodillaNo ratings yet

- STS1 1Document42 pagesSTS1 1Peter Paul Rebucan PerudaNo ratings yet

- Plastic - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument6 pagesPlastic - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediadidodido_67No ratings yet

- Operating Instruction Analytical Balance: Kern AbtDocument71 pagesOperating Instruction Analytical Balance: Kern AbtdexterpoliNo ratings yet

- Chapter-3 - Pie ChartsDocument6 pagesChapter-3 - Pie Chartsvishesh bhatiaNo ratings yet

- M.H. Saboo Siddik College of Engineering: CertificateDocument55 pagesM.H. Saboo Siddik College of Engineering: Certificatebhanu jammu100% (1)

- LabVentMgmt RPDocument100 pagesLabVentMgmt RPGanesh.MahendraNo ratings yet

- MODULE-VIII Processing Seledted Food ItemDocument8 pagesMODULE-VIII Processing Seledted Food ItemKyla Gaile MendozaNo ratings yet

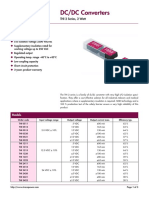

- DC/DC Converters: FeaturesDocument3 pagesDC/DC Converters: FeaturesPustinjak SaharicNo ratings yet

- Picking Manten Tebu' in The Syncretism of The Cembengan Tradition Perspective of Value Education and Urf'-Lila, Siti, Ning FikDocument10 pagesPicking Manten Tebu' in The Syncretism of The Cembengan Tradition Perspective of Value Education and Urf'-Lila, Siti, Ning FiklilaNo ratings yet

- KS3 Africa 5ghanafactsheetDocument3 pagesKS3 Africa 5ghanafactsheetSandy SaddlerNo ratings yet

- 6 Chapter 6 GasTurbineCombinedCyclesDocument47 pages6 Chapter 6 GasTurbineCombinedCyclesRohit SahuNo ratings yet

- Introductory Booklet On Solar Energy For Coaching StockDocument46 pagesIntroductory Booklet On Solar Energy For Coaching StockVenkatesh VenkateshNo ratings yet

- Impact of Electricity Power OutagesDocument13 pagesImpact of Electricity Power OutagesGaspard UkwizagiraNo ratings yet

- Chemostat Recycle (Autosaved)Document36 pagesChemostat Recycle (Autosaved)Zeny Naranjo0% (1)

- CSR of TI Company NotesDocument3 pagesCSR of TI Company NotesjemNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 8 QuestionsDocument3 pagesTutorial 8 QuestionsEvan DuhNo ratings yet

- TX 433Document8 pagesTX 433Sai PrintersNo ratings yet

- Newsweek 1908Document60 pagesNewsweek 1908Rcm MartinsNo ratings yet

- PT Indah Jaya II + III: 2 X JMS 620 GS-N.L J C345Document369 pagesPT Indah Jaya II + III: 2 X JMS 620 GS-N.L J C345SaasiNo ratings yet

- Mohammad Faisal Haroon - Envr506 - Week7Document4 pagesMohammad Faisal Haroon - Envr506 - Week7Hasan AnsariNo ratings yet

- Physical Sciences P1 Feb March 2018 EngDocument20 pagesPhysical Sciences P1 Feb March 2018 EngKoketso LetswaloNo ratings yet

- Benefits of FastingDocument6 pagesBenefits of FastingAfnanNo ratings yet

- Kotamovol2no5 WardialamsyahDocument27 pagesKotamovol2no5 WardialamsyahRo'onspadoSiiTorusNo ratings yet

- Math 241 Section 2.1 (3-2-2021)Document20 pagesMath 241 Section 2.1 (3-2-2021)H ANo ratings yet

- Secondary 6 FCE ExamPack SEVENDocument3 pagesSecondary 6 FCE ExamPack SEVENamtenistaNo ratings yet

- 1st Question Experimental DesignDocument16 pages1st Question Experimental DesignHayaa KhanNo ratings yet

- Asian33 112009Document40 pagesAsian33 112009irmuhidinNo ratings yet

- Medicine Buddha SadhanaDocument4 pagesMedicine Buddha SadhanaMonge Dorj100% (2)

Blue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim A

Blue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim A

Uploaded by

Rose Emmanuelle Garcia0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

66 views4 pagesThis summary provides the key details from the document in 3 sentences:

Babo, the narrator's aunt, brings the young orphan boy to live with the wealthy Datu's family in hopes he will be cared for, as she is too poor to support them both. Upon arriving, the boy is nervous but intrigued by the Datu's daughter who laughs at his harelip. Babo ensures the boy understands the proper etiquette for interacting with the noble family and reassures him that he will be happy living with them, though he worries about missing Babo.

Original Description:

Original Title

Blue Blood of the big Astana by Ibrahim A

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis summary provides the key details from the document in 3 sentences:

Babo, the narrator's aunt, brings the young orphan boy to live with the wealthy Datu's family in hopes he will be cared for, as she is too poor to support them both. Upon arriving, the boy is nervous but intrigued by the Datu's daughter who laughs at his harelip. Babo ensures the boy understands the proper etiquette for interacting with the noble family and reassures him that he will be happy living with them, though he worries about missing Babo.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

66 views4 pagesBlue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim A

Blue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim A

Uploaded by

Rose Emmanuelle GarciaThis summary provides the key details from the document in 3 sentences:

Babo, the narrator's aunt, brings the young orphan boy to live with the wealthy Datu's family in hopes he will be cared for, as she is too poor to support them both. Upon arriving, the boy is nervous but intrigued by the Datu's daughter who laughs at his harelip. Babo ensures the boy understands the proper etiquette for interacting with the noble family and reassures him that he will be happy living with them, though he worries about missing Babo.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 4

Blue Blood of the big Astana by Ibrahim

A. Jubaira Datu’s daughter, if I worked hard and behaved well.

I asked Babo, too, if might be allowed to prick your skin to see if

Although the heart may care no more, the mind can always recall.

you had blue blood, in truth. But Babo did not answer me anymore.

The mind can always recall, for there are always things to

She just told me to keep quiet. There, I became so talkative again.

remember: languid days of depressed boyhood; shared happy days

Was that really our house? My, it was so big! Babo chided me. “We

under the glare of the sun; concealed love and mocking fate; etc. So

don’t call it a house,” she said. “We call it Astana, the house of the

I suppose you remember too.

Datu,” So I just said oh, and kept quiet. Why did not Babo tell me

Remember? A little over the year after I was orphaned, my aunt

that before?

decided to turn me over to your father, the Datu. In those days,

Babo suddenly stopped in her tracks. Was I really very clean? Oh,

datus were supposed to take charge of the poor and the helpless.

oh, look at my hare-lip. She cleaned my hare-lip, wipping away with

Therefore, my aunt only did right in placing me under the wing of

her tapis the sticky mucus of the faintest conceivable green flowing

your father. Furthermore she was so poor, that by doing that, she

from my nose. Poi! Now it was better. Although I could not feel any

not only relieved herself of the burden of poverty but also safe-

sort of improvement in my deformity itself. I merely felt cleaner.

guarded my well-being.

Was I truly the boy about whom Babo was talking? You were

But I could not bear the thought of even a moment’s separation

laughing, young pretty Blue Blood. Happy perhaps that I was. Or

from my aunt. She had been like a mother to me, and would always

was it the amusement brought about by my hare-lip that had made

be.

you laugh? I dared not ask you. I feared that should you to dislike

“Please, Babo,” I pleaded. “Try to feed me a little more. Let me

me, you’d subject me to unpleasant treatment. Hence, I laughed

grow big with you, and I will build you a house. I will repay you

with you, and you were pleased.

someday. Let me do something to help, but please, Babo, don’t

Babo told me to kiss your right hand. Why not your feet? Oh, you

send me away…” I really cried.

were a child yet. I could wait until you had grown up.

Babo placed a soothing hand on my shoulder. Just like the hand of

But you withdrew your hand a once. I think my hare-lip gave it a

Mother. I felt a bit comforted, but presently I cried some more. The

ticklish sensation. However, I was so intoxicated by the momentary

effect of her hand was so stirring.

sweetness the action bought me that I decided inwardly to kiss your

“Listen to me. Stop crying—oh, now, do stop. You see, we can’t go

hand every day. No, no, it was not love. It was only an impish sort of

on like this,” Babo said. “My matweaving can’t clothe and feed both

liking. Imagine the pride that was mine to be thus in close heady

you and me. It’s really hard, son, it’s really hard. You have to go. But

contact with one of the blue blood….

I will be seeing you every week. You can have everything you want

in the Datu’s house.”

“Welcome, little orphan!” Was it for me? Really for me? I looked at

I tried to look at Babo through my tears. But soon, the thought of

Babo. Of course it was for me! We were generously bidden in.

having everything I wanted took hold of my child’s mind. I ceased

Thanks to your father’s kindness. And thanks to you laughing at me,

crying.

too.

“Say you will go,” Babo coaxed me. I assented finally. I was only

I kissed the feet of your Appab, your old, honorable resting-the-

five then—very tractable.

whole-day father. He was not tickled by my hare-lip as you were. He

Babo bathed me in the afternoon. I did not flinch and shiver, for the

did not laugh at me. And so did your Ambob, your kind mother. “Sit

sea was comfortably warm and exhilarating. She cleaned my

down, sit down; don’t be ashamed.”

fingernails meticulously. Then she cupped a handful of sand, spread

But there you were plying Babo with your heartless questions: Why

it over my back, and rubbed my grimy body, particularly the back of

was I like that? What had happened to me?

my ears. She poured fresh water over me afterwards. How clean I

To satisfy you, pretty Blue Blood, little inquisitive One, Babo had to

became! But my clothes were frayed….

explain: Well, mother had slid in the vinta in her sixth month with the

Babo instructed me before we left for your big house: I must not

child that was me. Result: my hare-lip “Poor Jaafar,” your Appab

forget to kiss your father’s feet, and to withdraw when and as

said. I was about to cry, but seeing you looking at me, I felt so

ordered without turning my back; I must not look at your father full in

ashamed that I held back the tears. I could not help being

the eyes; I must not talk too much; I must always talk in the third

sentimental, you see. I think my being bereft of parents in youth had

person; I must not… Ah, Babo, those were too many to remember.

much to do with it all.

Babo tried to be patient with me. She tested me over and over

“Do you think you will be happy to stay with us? Will you not yearn

again on those royal, traditional ways. And one thing more: I had to

any more for your Babo?”

say “Pateyk” for yes, and “Teyk” for what, or for answering a call.

“Pateyk, I will be happy,” I said. Then the thought of my not

“Oh Babo, why do you have to say all those things? Why really do I

yearning any more for Babo made me wince. But Babo nodded at

have?”

me reassuringly.

“Come along, son; come along.”

“Patek, I will not yearn any more for… for Babo.”

We started that same afternoon. The breeze was cool as it blew

And Babo went before the interview was through. She had to cover

against my face. We did not get tired because we talked on the way.

five miles before evening came. Still I did not cry, as you may have

She told me so many things. She said you of the big house had blue

expected I would, for—have I not said it? —I was so ashamed to

blood.

weep in your presence.

“Not red like ours, Babo?”

That as how I came to stay with you, remember? Babo came to see

Babo said no, not red like ours.

me every week as she had promised. And you— all of you— had lot

“And the Datu has a daughter of my age, Babo?”

Babo said yes—you. And I might be allowed to play with you, the

of things to tell her. That I was a good worker —oh, beyond flow of water? Hearts, hearts. Not brains. But I just kept silent. After

question, your Appab and Ambob told Babo. And you outspoken all, I was not there to ask impertinent questions. Shame, shame on

little Blue Blood joined the flattering chorus. But my place of sleep my hare-lip asking such question, I chided myself silently.

always reckoned of urine, you added, laughing. That downright

promise from me not to wet my mat again. That was how I played the part of an Epang-Epang, of a servant-

Yes, Babo came to see me, to advise me every week, for two escort, to you. And I became more spirited every day, trudging

consecutive years— that is, until death took her away, leaving no behind you. I was like a faithful, loving dog following its mistress with

one in the world but a nephew with a hare-lip. light steps and a singing heart. Because you, ahead of me, were

Remember? I was you’re your favorite and you wanted to play with something of an inspiration I could trail indefatigably, even to the

me always. I learned why after a time, it delighted you to gaze at my ends of the world….

hare-lip. Sometimes, when went out wading to the sea, you would The dreary monotone of your Koranchanting lasted three years.

pause and look at you, too, wondering. Finally, you would chime in, You were so slow, you Goro said. At times, she wanted to whip you.

not realizing I was making fun of myself. Then you would pinch me But did she not know you were the Datu’s daughter? Why, she

painfully to make me cry. Oh, you wanted to experiment with me. would be flogged herself. But whipping an orphaned servant and

You could not tell, you said whether I cried or laughed: the working clipping his split lips with two pieces of wood were evidently

of my lips was just the same in either to your gleaming eyes. And I permissible. So, your Goro found me a convenient substitute for

did not flush with shame even if you said so. For after all, had not you. How I groaned with pain under her lashings! But how your Goro

my mother slid in the vinta. laughed; the wooden clips failed to keep my hare-lip closed. They

Remember? I was apparently so willing to do anything for you. I always slipped. And the class, too roared with laughter—you

would climb for young coconuts for you. I would be amazed by the leading.

ease and agility. With which I made my way up the coconut tree, yet But back there in your spacious astana, you were already being

fear that I would implore me to come down at once, quick. “No.” you tutored for maidenhood. I was older than you by one Ramadan. I

would throw pebbles at me if thus refused to come down. No, I still often wondered why you grew so fast, while I remained a lunatic

would not. Your pebbles could not reach me— you were not strong dwarf. Maybe the poor care I received in early boyhood had much to

enough. You would then threaten to report me to your Appab. “Go do with my hampered growth. However, I was happy, in a way that I

ahead.” How I liked being at the top! And sing there as I looked at did not catch up with you. For I had a hunch you would not continue

you helpless. In a spasm of anger, you would curse me, wishing my to avail yourself of my help in certain intimate tasks—such as

death. Well, let me die. I would die. I would climb the coconut trees scrubbing your back when you took your bath— had I grown as fast

in heaven. And my ghost would shout, “Dayang-Dayang, I am as you.

coming down!” Then you would come back. You see? A servant, an There I was in my bed at night, alone, intoxicated with passion and

orphan, could also command the fair and proud Blue Blood to come emotions closely resembling those of a full-grown man’s. I thought

or go. of you secretly, unashamedly, lustfully: a full-grown Dayang-Dayang

Then we would pick up little shells, and search for sea-cucumbers; reclining in her bed at the farthest end of her inner apartment;

or dive for the sea-urchins. Or run along the along the long stretch of breasts heaving softly like breezekissed waters; cheeks of the

white glaring sand, I behind you— admiring your soft, nimble feet faintest red brushing against a soft pillow; eyes gazing dreamily into

and your flying hair. Then we would stop, panting, laughing. immensity—warm, searching, expressive; supple buttocks and pliant

After resting for a while, we would run again to the sea and wage arms; soft, ebon hair that rippled….

war against the crashing waves. I would rub your silky back after we Dayang-Dayang, could you have forgiven a deformed orphan-

had finished bathing in the sea. I would get fresh water in a clean servant had he gone mad, and lost respect and dread towards your

coconut shell, and rinse your soft, ebon hair. Your hair flowed down Appab? Could you have pardoned his rabid temerity had he leaped

smoothly, gleaming in the afternoon sun. Oh, it was beautiful. Then I out of his bed, rushed into your room, seized you in his arms, and

would trim your fingernails carefully. Sometimes you beg you to tickled your face with his hare-lip? I should like to confess that for at

whip me. Just so you could differentiate between my crying and my least a moment, yearning, starved, athirst… no, no, I cannot say it.

laughing. And even the pain you gave me partook of sweetness. We were of such contrasting patterns. Even the lovely way you

That was my way. My only way to show how grateful I was for the looked—the big astana you lived in—the blood you had….

things I had not tasted before: your companionship; shelter and food Not even the fingers of Allah perhaps could weave our fabrics into

in your big astana. So your parents sent you to a Mohammedan equality. I had to content myself with the privilege of gazing

school when you were seven. I was not sent to study with you, but it frequently at your peerless loveliness. An ugly servant must not go

made no difference to me. For after all, was not my work carrying beyond his little border.

your red Koran on my top of my head four times a day? And you But things did not remain as they were. A young Datu from Bonbon

were happy, because I could entertain you. Because someone could came back to ask for your hand. Your Appab was only too glad to

be a water –carrier for you. One of the requirements then was to welcome him. There was nothing better, he said, than marriage

carry water every time you showed up in your Mohammedan class, between two people of the same blue blood. Besides, he was

“Oh, why? Excuse the stammering of my hare-lip, but I really wished growing old. He had no son to take his place some day. Well, the

to know.” Your Goro, your Mohammedan teacher, looked deep into young Datu was certainly fit to take in due time the royal torch your

me as if to search my whole system. Stupid. Did I not know our Appab had been carrying for years. But I—I felt differently; of

hearts could easily grasp the subject matter, like the soft, incessant

course. I wanted…. No, I could not have a hand in your marital touch thrice the space between your eyebrows. And every time that

arrangements. What was I, after all? was done, my breast heaved and my lips worked.

Certainly your Appab was right. The young Datu was handsome. Remember? You were about to cry, Dayang – dayang. For, as the

And rich, too. He had a large tract of land planted with the fruit trees, people said, you would soon be separated from your parents. Your

coconut trees, and abaca plants. And you were glad, too. Not husband would soon take you to Bonbon, and you would live there

because he was rich—for you were rich yourself. I thought I knew like a country woman. But as you unexpectedly caught a glimpse of

why: the young Datu could rub your soft back better than I whenever me, you smiled at once, a little. And I knew why: my hare-lip

you took your bath. His hands were not as callous as mine…. amused you again. I smiled back at you, and withdrew at once. I

However, I did not talk to you about it. Of course. withdrew at once because I could not bear further seeing you sitting

Your Appab ordered his subjects to build two additional wings to beside the young Datu, and knowing fully well that I who had

your astana. Your astana was already big, but it had to be enlarged sweated, labored, and served you like a dog…. No, no, shame on

as hundreds of people would be coming to witness your royal me to think of all that at all. For was it not but a servant’s duty?

wedding. But I escaped that night, pretty Blue Blood. Where to? Anywhere.

The people sweated profusely. There was a great deal of That was exactly seven years ago. And those years did wonderful

hammering, cutting, and lifting as they set up posts. Plenty of eating things for me. I am no longer a lunatic dwarf, although my hare-lip

and jabbering. And chewing of betel nuts and native seasoned remains as it has always been.

tobacco. And emitting of red saliva afterwards. In just one day, the Too, I have amassed a little fortune after years of sweating I could

additional wings were finished. have taken two or three wives, but I had not yet found anyone

Then came your big wedding. People had crowded your astana resembling you lovely Blue Blood. So single I remained.

early in the day to help in the religious slaughtering of cows and And Allah’s Wheel of time kept on turning, kept on turning. And to,

goats. To aid, too, in the voracious consumption of your wedding once day your husband was transforted to San Ramon Penal Farm,

feast. Some more people came as evening drew near. Those who Zamboanga. He had raised his hand against the Christian

could not be accommodated upstairs had to stay below. government. He had wished to establish his own government. He

Torches fashioned out of dried coconut leaves blazed in the night. wanted to show his petty power by refusing to pay land taxes, on the

Half-clad natives kindled them over the cooking fire. Some pounded ground that the land he had were by legitimate inheritance his own

rice for cakes. And their brown glossy bodies sweated profusely. absolutely. He did not understand that the little amount he should

Out in the astana yard, the young Datu’s subjects danced in great give in the form of taxes would be utilized to protect him and his

circles. Village swains danced with grace, now swaying sensuously people from swindlers. He did not discern that he was in fact a part

their shapely hips, now twisting their pliant arms. Their feet moved of the Christian government himself. Consequently his subjects lost

deftly and almost imperceptibly. their lives fighting for a wrong cause. Your Appab, too, was drawn

Male dancers would crouch low, with a wooden spear, a kris, or a into the mess, and perished with the others. His possessions were

barong in one hand, and a wooden shield in the other. They confiscated. And your Ambob, died of a broken heart. Your

simulated bloody warfare by dashing through the circle of other husband, to save his life, had to surrender. His lands, too, were

dancers and clashing against each other. Native flutes, drums, confiscated. Only a little portion was left for you to cultivate and live

gabangs, agongs, and kulintangs contributed much to the musical on.

gayety of the night. Dance. Sing in delight. Music. Noise. And remember? I went one day to Bonbon on business. And I saw

Laughter. Music swelled out into the world like a heart full of blood, you on your bit of land with your children. At first, I could not believe

vibrant, palpitating. But it was my heart that swelled with pain. The it was you. Then you looked long deep into me. Soon the familiar

people would cheer: “Long live the Dayang-Dayang and the Datu, eyes of Blue Blood of years ago arrested the faculties of the

MURAMURAAN!” at every intermission. And I would cheer, too— erstwhile servant. And you could not believe your eyes either. You

mechanically before I knew. I would be missing you so…. could not recognize me at once. But when you saw my hare-lip

People rushed and elbowed their way up into your Astana as the smiling at you, rather hesitantly, you knew me at last. And I was glad

young Datu was led to you. Being small, I succeeded in squeezing you did.

in near enough to catch a full view of you. You, Dayang – Dayang. “Oh, Jaafar,” you gasped, dropping you janap, your primitive trowel,

Your moon-shaped face was meticulously powdered with pulverized instinctively. And you thought I was no longer living, you said.

rice. Your hair was skewered up toweringly at the center of your Curse, curse. It was still your frank, outspoken way. It was like you

head, and studded with glittering hold hair-pins. Your tight, to be able to jest even hen sorrow was on the verge of removing the

gleamingly black dress was covered with a flimsy mantle of the last vestiges of your loveliness. You could somehow conceal your

faintest conceivable pink. Gold buttons embellished your wedding pain and grief beneath banter and laughter. And I was glad of that,

garments. You sat rigidly on a mattress, with native embroidered too.

pillows piled carefully at the back. Candled-light mellowed your face Well, I was about to tell you that the Jaafar you saw now was a very

so beautifully you were like a goddess perceived in dreams. You different – a much improved – Jaafar. Indeed. But instead: “Oh,

looked steadily down. Dayang-Dayang,” I murmured, distressed to have seen you working.

The moment arrived. The turbaned pandita, talking in a voice of You who had been reared in case and luxury. However, I tried very

silk, led the young Datu to you, while maidens kept chanting songs much not to show traces of understanding your deplorable situation.

from behind. The Pandita grasped the Datu’s forefinger, and made it

One of your sons came running and asked who I was. Well, I was, I and rinse your dry, ruffled hair, that it might be restored to flowing

was…. smoothness and glorious luster. I wanted to trim your fingernails,

“Your old servant,” I said promptly. Your son said oh, and kept stroke your callous hand. I yearned to tell you that the land and the

quiet, returning at last to resume his work. Work, work, Eting. Work, cattle I owned were all yours. And above all, I burned to whirl back

son. Bundle of firewood and take it to the kitchen. Don’t mind your to you and beg you and your children to come home with me.

old servant. He won’t turn young again. Poor little Datu, working so Although the simple house I lived in as not as big as your astana at

hard. Poor pretty Blue Blood, also working hard. Patikul, it would at least be a happy, temporary haven while you

We kept strangely silent for a long time. And then: By the way, waited for your husband’s release.

where was I living now? In Kanagi. My business here in Bonbon That urge to go back to you, Dayang-Dayang, was strong. But I did

today? To see Panglima Hussin about the cows he intended to sell, not go back for a sudden qualm seized me: I had no blue blood. I

Dayang-Dayang. Cows? Was I a landsman already? Well, if the had only a hare-lip. Not even the fingers of Allah perhaps could

pretty Blue Blood could live like a countrywoman, why not a man like weave us, even now, into equality.

your old servant? You see, luck was against me in sea-roving

activities, so I had to turn to buying and selling cattle. Oh, you said.

And then you laughed. And I laughed with you. My laughter was dry.

Or was it yours? However, you asked what was the matter. Oh,

nothing. Really nothing serious. But you see…. And you seemed to

understand as I stood there infront of you, leaning against a mango

tree, doing nothing but stare and stare at you.

I observed that your present self was only the ragged reminder, the

mere ghost, of the Blue Blood of the big astana. Your resources of

vitality and loveliness and strength seemed to have been drained

out of your old arresting self, poured into the little farm you were

working in. Of course I did not expect you to be as lovely as you had

been. But you should have retained at least a fair portion of it-of the

old days. Not blurred eyes encircled by dark ring; not dull, dry hair;

not a sunburned complexion; not wrinkled, callous hand; not….

You seemed to understand more and more. Why was I looking at

you like that?

Was it because I had not seen you for so long? Or was it something

else? Oh, Dayang-Dayang, was not the terrible change in you the

old servant’s concern? You suddenly turned your eyes away from

me. You picked up your janap and began troubling the soft earth. It

seemed you could not utter another word without breaking into

tears. You turned your back toward me because you hated having

me see you in tears.

And I tried to make out why: seeing me now revived old memories.

Seeing me, talking with me, poking fun at me, was seeing, talking,

and joking as in the old days at the vivacious astana. And you

sobbed as I was thinking thus. I knew you sobbed, because your

shoulders shook. But I tried to appear as though I was not aware of

your controlled weeping. I hated myself for coming to you and

making you cry. So…

“May I go now, Dayang-Dayang” I said softly, trying hard to hold

back my own tears. You did not say yes. And you did not say no,

either. But the nodding of your head was enough to make me

understand and go. Go where? Was there a place to go? Of course.

There were many places to go to. Only, there was seldom a place to

which one would like to return.

But something transfixed me in my tracks after walking a mile or so.

There was something of an impulse that strove to drive me back to

you, making me forget Panglima Hussin’s cattle. Every instinct told

me it was right for me to go back to you and do something-perhaps

beg you to remember your old Jaafar’s hare-lip, just so you could

smile and be happy again. I wanted to rush back and wipe away the

tears from your eyes with my headdress. I wanted to get fresh water

You might also like

- Daddys Little PetDocument8 pagesDaddys Little PetLovelessNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument4 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaCarla ArceNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument6 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaFranchesca Nicole CalmaNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument9 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanahIgh QuaLIty SVTNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument12 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaCarl Gabriel Calpe CulveraNo ratings yet

- Literary PiecesDocument8 pagesLiterary PiecesAlyssa VerdijoNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument11 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaBeatrix Medina100% (1)

- Blue Blood of Big AstanaDocument8 pagesBlue Blood of Big AstanaAdrian EstrelladoNo ratings yet

- Blue BloodDocument7 pagesBlue Bloodjean magallonesNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim JubairaDocument12 pagesBlue Blood of The Big Astana by Ibrahim Jubairaramy hinolanNo ratings yet

- Blue Blood of The Big AstanaDocument12 pagesBlue Blood of The Big AstanaJustine Roice MorenoNo ratings yet

- Ibrahim Jubaira Is Perhaps The Best Known of The Older Generation of English LanguageDocument10 pagesIbrahim Jubaira Is Perhaps The Best Known of The Older Generation of English Languagesalack cosainNo ratings yet

- The Rhyme of The Ancient Barbie in Five PartsDocument6 pagesThe Rhyme of The Ancient Barbie in Five PartsAdam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Summer at the Cornish Farmhouse: Escape to Cornwall in 2024 with this absolutely feel-good romantic read!From EverandSummer at the Cornish Farmhouse: Escape to Cornwall in 2024 with this absolutely feel-good romantic read!No ratings yet

- Little Boy 'S Love For His Family I: MoralDocument3 pagesLittle Boy 'S Love For His Family I: MoralKajal GadeNo ratings yet

- Before Women Had WingsDocument5 pagesBefore Women Had WingsGianna RamirezNo ratings yet

- PDF of Masse Und Meinung Gabriel Tarde Full Chapter EbookDocument69 pagesPDF of Masse Und Meinung Gabriel Tarde Full Chapter Ebookphilispalae425100% (6)

- Kitten's New Collar: A Razor's Edge Daddy Dom Erotica ShortFrom EverandKitten's New Collar: A Razor's Edge Daddy Dom Erotica ShortNo ratings yet

- Buck Me Cowboy: A Secret Baby Western RomanceFrom EverandBuck Me Cowboy: A Secret Baby Western RomanceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- Abe by Jeff LockerDocument7 pagesAbe by Jeff LockerGizelaNo ratings yet

- DeclamationDocument9 pagesDeclamationIlham Jhann AcramanNo ratings yet

- Jambo Youth Issue 58Document2 pagesJambo Youth Issue 58ShyjanNo ratings yet

- A Fool Not To FuckDocument29 pagesA Fool Not To Fuckkadas alkadasNo ratings yet

- High - School DXD Volume - 4 - Ichiei IshibumiDocument268 pagesHigh - School DXD Volume - 4 - Ichiei Ishibumiashlynx.No ratings yet

- Download ebook pdf of От Arpanet До Internet 1St Edition Коллектив Авторов full chapterDocument24 pagesDownload ebook pdf of От Arpanet До Internet 1St Edition Коллектив Авторов full chapternkqayielhamm100% (12)

- A Reincarnated Mage's Volume 1Document125 pagesA Reincarnated Mage's Volume 1Addiedom BiacoloNo ratings yet

- Literary Works From The Mindanao Literature From The Past and The Present Time-1Document11 pagesLiterary Works From The Mindanao Literature From The Past and The Present Time-1Pascual GarciaNo ratings yet

- Life From The River by Jan HudsonDocument3 pagesLife From The River by Jan HudsonMiguel GutierrezNo ratings yet

- OceanofPDF - Com Our Family Secret - Savannah BrooksDocument118 pagesOceanofPDF - Com Our Family Secret - Savannah BrooksJessicaNo ratings yet

- Push The Envelope Draft 1Document63 pagesPush The Envelope Draft 1Marlaine AmbataNo ratings yet

- Why Does My Grandfather, Charles Darwin, Act So Strangely?: As Told by Bernard DarwinFrom EverandWhy Does My Grandfather, Charles Darwin, Act So Strangely?: As Told by Bernard DarwinNo ratings yet

- Que Tienes ?: Como Estas ?Document8 pagesQue Tienes ?: Como Estas ?JONNATHAN LOZADANo ratings yet

- 11 Physics Chapter 14 and 15 Assignment 5Document2 pages11 Physics Chapter 14 and 15 Assignment 5Mohd UvaisNo ratings yet

- 2024 Base Merit Brochure EditedDocument2 pages2024 Base Merit Brochure EditedImee Kaye RodillaNo ratings yet

- STS1 1Document42 pagesSTS1 1Peter Paul Rebucan PerudaNo ratings yet

- Plastic - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument6 pagesPlastic - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediadidodido_67No ratings yet

- Operating Instruction Analytical Balance: Kern AbtDocument71 pagesOperating Instruction Analytical Balance: Kern AbtdexterpoliNo ratings yet

- Chapter-3 - Pie ChartsDocument6 pagesChapter-3 - Pie Chartsvishesh bhatiaNo ratings yet

- M.H. Saboo Siddik College of Engineering: CertificateDocument55 pagesM.H. Saboo Siddik College of Engineering: Certificatebhanu jammu100% (1)

- LabVentMgmt RPDocument100 pagesLabVentMgmt RPGanesh.MahendraNo ratings yet

- MODULE-VIII Processing Seledted Food ItemDocument8 pagesMODULE-VIII Processing Seledted Food ItemKyla Gaile MendozaNo ratings yet

- DC/DC Converters: FeaturesDocument3 pagesDC/DC Converters: FeaturesPustinjak SaharicNo ratings yet

- Picking Manten Tebu' in The Syncretism of The Cembengan Tradition Perspective of Value Education and Urf'-Lila, Siti, Ning FikDocument10 pagesPicking Manten Tebu' in The Syncretism of The Cembengan Tradition Perspective of Value Education and Urf'-Lila, Siti, Ning FiklilaNo ratings yet

- KS3 Africa 5ghanafactsheetDocument3 pagesKS3 Africa 5ghanafactsheetSandy SaddlerNo ratings yet

- 6 Chapter 6 GasTurbineCombinedCyclesDocument47 pages6 Chapter 6 GasTurbineCombinedCyclesRohit SahuNo ratings yet

- Introductory Booklet On Solar Energy For Coaching StockDocument46 pagesIntroductory Booklet On Solar Energy For Coaching StockVenkatesh VenkateshNo ratings yet

- Impact of Electricity Power OutagesDocument13 pagesImpact of Electricity Power OutagesGaspard UkwizagiraNo ratings yet

- Chemostat Recycle (Autosaved)Document36 pagesChemostat Recycle (Autosaved)Zeny Naranjo0% (1)

- CSR of TI Company NotesDocument3 pagesCSR of TI Company NotesjemNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 8 QuestionsDocument3 pagesTutorial 8 QuestionsEvan DuhNo ratings yet

- TX 433Document8 pagesTX 433Sai PrintersNo ratings yet

- Newsweek 1908Document60 pagesNewsweek 1908Rcm MartinsNo ratings yet

- PT Indah Jaya II + III: 2 X JMS 620 GS-N.L J C345Document369 pagesPT Indah Jaya II + III: 2 X JMS 620 GS-N.L J C345SaasiNo ratings yet

- Mohammad Faisal Haroon - Envr506 - Week7Document4 pagesMohammad Faisal Haroon - Envr506 - Week7Hasan AnsariNo ratings yet

- Physical Sciences P1 Feb March 2018 EngDocument20 pagesPhysical Sciences P1 Feb March 2018 EngKoketso LetswaloNo ratings yet

- Benefits of FastingDocument6 pagesBenefits of FastingAfnanNo ratings yet

- Kotamovol2no5 WardialamsyahDocument27 pagesKotamovol2no5 WardialamsyahRo'onspadoSiiTorusNo ratings yet

- Math 241 Section 2.1 (3-2-2021)Document20 pagesMath 241 Section 2.1 (3-2-2021)H ANo ratings yet

- Secondary 6 FCE ExamPack SEVENDocument3 pagesSecondary 6 FCE ExamPack SEVENamtenistaNo ratings yet

- 1st Question Experimental DesignDocument16 pages1st Question Experimental DesignHayaa KhanNo ratings yet

- Asian33 112009Document40 pagesAsian33 112009irmuhidinNo ratings yet

- Medicine Buddha SadhanaDocument4 pagesMedicine Buddha SadhanaMonge Dorj100% (2)