Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robert Browning

Robert Browning

Uploaded by

Dimple PuriOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Robert Browning

Robert Browning

Uploaded by

Dimple PuriCopyright:

Available Formats

M. H.

Abrams, one of the general editors of the Norton Anthology of English Literature and a respected

American critic known especially for work on Romanticism, lists three features of the dramatic monologue as it

applies to poetry:

1. A single person, who is clearly not the poet, utters the speech that makes up the whole of the poem, in a specific

situation at a critical moment.

2. This person addresses and interacts with one or more people; but we know of the auditors’ presence, and what

they say or do, only from clues in the discourse of the single speaker.

3. The main principle controlling the poet’s choice and formulation of what the lyric speaker says is to reveal to the

reader, in a way that enhances its interest, the speaker’s temperament and chararcter

Jyoti Sheokand and Sandhya Saxena (2011) make a

distinction between the two poems on one side and the other poems of the same volume on the other

side:

Browning wrote poetry, broadly speaking, of two kinds of love poems – personal and

dramatic. Though his personal poems are very few, yet, he poured out his personal

experiences in the form of verse fully. "By the Fireside" and "One Word More" are a

few poems that can surpass the passion of love and where the veil of reserve is lifted to

reveal the poet's personal feelings for his wife. However, most of the other poems by

Browning dealing with love are dramatic in essence. In each, there is a certain situation

and revelation of the emotions of a character placed in the situation. (n. p.)Robert Browning is considered to be the

perfecter of the dramatic monologue, which had its heyday in the Victorian Period.

Cultural Context

Browning defied the conventions of Victorian poetry in as many ways as he followed

them. Browning enjoyed rich intellectual friendships with many of his artistic

contemporaries and was married to one of the most progressive and famous

Victorian writers. Despite this, he had a very unique poetic style. He preferred to

write about the personalities of other people rather than express his own feelings.

Similar to other Victorian writers, he was concerned with the role of art, morality,

corruption in organized religion, and corruption in governing bodies.

Browning pioneered the dramatic monologue. The use of dramatic monologues

allowed Browning to discuss controversial subjects without disclosing aspects of his

private identity. Artists and figures with religious ties were frequently the speakers

in Browning’s poetry because they provided a good basis for him to discuss issues

that mattered most to him. The subject Browning revisits most often is the purpose

of art.Men and Women reflects Browning's endeavor to challenge the reserved Victorian attitude

toward the direct expression of love in poetry. Victorian poets never externalized

the personal feelings of love in any explicit way. They neither addressed their readers directly

nor

dedicated love poems to their loved ones. The uniqueness of Browning's love lyrics is due to his

personal belief in the transformative

power of love as well as his belief in a love of a loftier type. This is partly what distinguishes

him

among his contemporaries. In "One Word More" Browning presents love as an emotional power

that is capable of

revealing one's true devotion and constancy.

Multiple Perspectives on Single Events

The dramatic monologue verse form allowed Browning to explore and probe the minds of specific characters in specific places

struggling with specific sets of circumstances. In The Ring and the Book, Browning tells a suspenseful story of murder using

multiple voices, which give multiple perspectives and multiple versions of the same story. Dramatic monologues allow readers to

enter into the minds of various characters and to see an event from that character’s perspective. Understanding the thoughts,

feelings, and motivations of a character not only gives readers a sense of sympathy for the characters but also helps readers

understand the multiplicity of perspectives that make up the truth. In effect, Browning’s work reminds readers that the nature of truth

or reality fluctuates, depending on one’s perspective or view of the situation. Multiple perspectives illustrate the idea that no one

sensibility or perspective sees the whole story and no two people see the same events in the same way. Browning further illustrated

this idea by writing poems that work together as companion pieces, such as “Fra Lippo Lippi” and “Andrea del Sarto.” Poems such

as these show how people with different characters respond differently to similar situations, as well as depict how a time, place, and

scenario can cause people with similar personalities to develop or change quite dramatically.

The Purposes of Art

Browning wrote many poems about artists and poets, including such dramatic monologues as “Pictor Ignotus” (1855) and “Fra Lippo

Lippi.” Frequently, Browning would begin by thinking about an artist, an artwork, or a type of art that he admired or disliked. Then he

would speculate on the character or artistic philosophy that would lead to such a success or failure. His dramatic monologues about

artists attempt to capture some of this philosophizing because his characters speculate on the purposes of art. For instance, the

speaker of “Fra Lippo Lippi” proposes that art heightens our powers of observation and helps us notice things about our own lives.

According to some of these characters and poems, painting idealizes the beauty found in the real world, such as the radiance of a

beloved’s smile. Sculpture and architecture can memorialize famous or important people, as in “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at

Saint Praxed’s Church” (1845) and “The Statue and the Bust” (1855). But art also helps its creators to make a living, and it thus has

a purpose as pecuniary as creative, an idea explored in “Andrea del Sarto.”

X

Video SparkNotes: Homer's The Odyssey summary

Video SparkNotes: Homer's The Odyssey summary

The Relationship Between Art and Morality

Throughout his work, Browning tried to answer questions about an artist’s responsibilities and to describe the relationship between

art and morality. He questioned whether artists had an obligation to be moral and whether artists should pass judgment on their

characters and creations. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Browning populated his poems with evil people, who commit crimes

and sins ranging from hatred to murder. The dramatic monologue format allowed Browning to maintain a great distance between

himself and his creations: by channeling the voice of a character, Browning could explore evil without actually being evil himself. His

characters served as Personae that let him adopt different traits and tell stories about horrible situations. In “My Last Duchess,”

the speaker gets away with his wife’s murder since neither his audience (in the poem) nor his creator judges or criticizes him.

Instead, the responsibility of judging the character’s morality is left to readers, who find the duke of Ferrara a vicious, repugnant

person even as he takes us on a tour of his art gallery.

Motifs

Medieval and Renaissance European Settings

Browning set many of his poems in medieval and Renaissance Europe, most often in Italy. He drew on his extensive knowledge of

art, architecture, and history to fictionalize actual events, including a seventeenth-century murder in The Ring and the Book, and

to channel the voices of actual historical figures, including a biblical scholar in medieval Spain in “Rabbi Ben Ezra” (1864) and the

Renaissance painter in the eponymous “Andrea del Sarto.” The remoteness of the time period and location allowed Browning to

critique and explore contemporary issues without fear of alienating his readers. Directly invoking contemporary issues might seem

didactic and moralizing in a way that poems set in the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries would not. For instance, the

speaker of “The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church” is an Italian bishop during the late Renaissance. Through the

speaker’s pompous, vain musings about monuments, Browning indirectly criticizes organized religion, including the Church of

England, which was in a state of disarray at the time of the poem’s composition in the mid-nineteenth century.

Psychological Portraits

Dramatic monologues feature a solitary speaker addressing at least one silent, usually unnamed person, and they provide

interesting snapshots of the speakers and their personalities. Unlike soliloquies, in dramatic monologues the characters are always

speaking directly to listeners. Browning’s characters are usually crafty, intelligent, argumentative, and capable of lying. Indeed, they

often leave out more of a story than they actually tell. In order to fully understand the speakers and their psychologies, readers must

carefully pay attention to word choice, to logical progression, and to the use of Figures Of Speech, including

any Metaphors or analogies. For instance, the speaker of “My Last Duchess” essentially confesses to murdering his wife, even

though he never expresses his guilt outright. Similarly, the speaker of “Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister” inadvertently betrays his

madness by confusing Latin prayers and by expressing his hate for a fellow friar with such vituperation and passion. Rather than

state the speaker’s madness, Browning conveys it through both what the speaker says and how the speaker speaks.

Grotesque Images

Unlike other Victorian poets, Browning filled his poetry with images of ugliness, violence, and the bizarre. His contemporaries, such

as Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Gerard Manley Hopkins, in contrast, mined the natural world for lovely images of beauty. Browning’s

use of the grotesque links him to novelist Charles Dickens, who filled his fiction with people from all strata of society, including the

aristocracy and the very poor. Like Dickens, Browning created characters who were capable of great evil. The early poem

“Porphyria’s Lover” (1836) begins with the lover describing the arrival of Porphyria, then it quickly descends into a depiction of her

murder at his hands. To make the image even more grotesque, the speaker strangles Porphyria with her own blond hair. Although

“Fra Lippo Lippi” takes place during the Renaissance in Florence, at the height of its wealth and power, Browning sets the poem in a

back alley beside a brothel, not in a palace or a garden. Browning was instrumental in helping readers and writers understand that

poetry as an art form could handle subjects both lofty, such as religious splendor and idealized passion, and base, such as murder,

hatred, and madness, subjects that had previously only been explored in novels.

Symbols

Taste

Browning’s interest in culture, including art and architecture, appears throughout his work in depictions of his characters’ aesthetic

tastes. His characters’ preferences in art, music, and literature reveal important clues about their natures and moral worth. For

instance, the duke of Ferrara, the speaker of “My Last Duchess,” concludes the poem by pointing out a statue he commissioned of

Neptune taming a sea monster. The duke’s preference for this sculpture directly corresponds to the type of man he is—that is, the

type of man who would have his wife killed but still stare lovingly and longingly at her portrait. Like Neptune, the duke wants to

subdue and command all aspects of life, including his wife. Characters also express their tastes by the manner in which they

describe art, people, or landscapes. Andrea del Sarto, the Renaissance artist who speaks the poem “Andrea del Sarto,” repeatedly

uses the adjectives gold and silver in his descriptions of paintings. His choice of words reinforces one of the major themes of the

poem: the way he sold himself out. Listening to his monologue, we learn that he now makes commercial paintings to earn a

commission, but he no longer creates what he considers to be real art. His desire for money has affected his aesthetic judgment,

causing him to use monetary vocabulary to describe art objects.

Evil and Violence

Synonyms for, images of, and Symbols of evil and violence abound in Browning’s poetry. “Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister,” for

example, begins with the speaker trying to articulate the sounds of his “heart’s abhorrence” (1) for a fellow friar. Later in the poem,

the speaker invokes images of evil pirates and a man being banished to hell. The diction and images used by the speakers

expresses their evil thoughts, as well as indicate their evil natures. “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” (1855) portrays a

nightmarish world of dead horses and war-torn landscapes. Yet another example of evil and violence comes in “Porphyria’s Lover,”

in which the speaker sits contentedly alongside the corpse of Porphyria, whom he murdered by strangling her with her hair. Symbols

of evil and violence allowed Browning to explore all aspects of human psychology, including the base and evil aspects that don’t

normally appear in poetry.

You might also like

- Qi Men Dun Jia (QMDJ)Document11 pagesQi Men Dun Jia (QMDJ)Customer SupportNo ratings yet

- Плутарх - Успоредни животописиDocument353 pagesПлутарх - Успоредни животописиauroradentataNo ratings yet

- Ss2 Ist Term Literature eDocument21 pagesSs2 Ist Term Literature eMD Teachers Resources100% (2)

- Savitri Book 1 Canto 1 Post 4Document3 pagesSavitri Book 1 Canto 1 Post 4api-3740764No ratings yet

- Claude Mackay Describes His Own Life:: A Negro PoetDocument4 pagesClaude Mackay Describes His Own Life:: A Negro PoetMaroonCastNo ratings yet

- The Empire Writes Back, Colonialism and PostcolonialismDocument4 pagesThe Empire Writes Back, Colonialism and PostcolonialismSaša Perović100% (1)

- Robert Browning A Dramatic MonologueDocument2 pagesRobert Browning A Dramatic MonologueArindam SenNo ratings yet

- WordsworthDocument3 pagesWordsworthMandyMacdonaldMominNo ratings yet

- Robert BrowningDocument18 pagesRobert BrowninganithafNo ratings yet

- RK NarayanDocument21 pagesRK NarayanSyed Mohammad Aamir AliNo ratings yet

- Themes of Waste LandDocument24 pagesThemes of Waste LandRaees Ali KhanNo ratings yet

- Chief Characteristics of Dryden As A CriticDocument4 pagesChief Characteristics of Dryden As A CriticQamar KhokharNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument32 pagesThesisNabanita Baruah0% (2)

- Realism in A K Ramanujans PoetryDocument8 pagesRealism in A K Ramanujans PoetryAnik KarmakarNo ratings yet

- Post Modern Indian Theatre - Ratan Thiyam's Silent War On WarDocument9 pagesPost Modern Indian Theatre - Ratan Thiyam's Silent War On Warbhooshan japeNo ratings yet

- Troilus and Criseyde: Chaucer, GeoffreyDocument8 pagesTroilus and Criseyde: Chaucer, GeoffreyBrian O'LearyNo ratings yet

- GORA' - A Postmodernist StudyDocument5 pagesGORA' - A Postmodernist StudyIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Toru DuttDocument5 pagesToru Duttsheenam_bhatiaNo ratings yet

- Riders To The SeaDocument45 pagesRiders To The SeaAshique ElahiNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Reality, Fantasy and Myth in The Select Plays of Girish KarnadDocument139 pagesTreatment of Reality, Fantasy and Myth in The Select Plays of Girish KarnadShachi Sood100% (1)

- What Kind of A Poem Is Matthew ArnoldDocument26 pagesWhat Kind of A Poem Is Matthew ArnoldDilip ModiNo ratings yet

- CANONIZATIONDocument7 pagesCANONIZATIONNiveditha PalaniNo ratings yet

- Dramatic Monologue Filippo Lippi Church Blank Verse Iambic PentameterDocument2 pagesDramatic Monologue Filippo Lippi Church Blank Verse Iambic PentameterEsther BuhrilNo ratings yet

- Tintern Abbey: William Wordsworth - Summary and Critical AnalysisDocument3 pagesTintern Abbey: William Wordsworth - Summary and Critical AnalysisBianca DarieNo ratings yet

- Emerson's "The Snow-Storm": A Representation of Natural BeautyDocument6 pagesEmerson's "The Snow-Storm": A Representation of Natural BeautyMustafa A. Al-HameedawiNo ratings yet

- MAEL - 201 UOU Solved Assignment MA17-English (Final Year) 2019Document13 pagesMAEL - 201 UOU Solved Assignment MA17-English (Final Year) 2019ashutosh lohani100% (3)

- Presented To: Dr. Archana Awasthi: A Study of Provincial LifeDocument7 pagesPresented To: Dr. Archana Awasthi: A Study of Provincial LifeJaveria MNo ratings yet

- Literaty CriticismDocument5 pagesLiteraty CriticismSantosh Chougule100% (1)

- Theory of ImpersonalityDocument1 pageTheory of ImpersonalityUddipta TalukdarNo ratings yet

- J.Weiner. The Whitsun WeddingsDocument5 pagesJ.Weiner. The Whitsun WeddingsОля ПонедильченкоNo ratings yet

- Epic Simile IsDocument2 pagesEpic Simile IsNishant SaumyaNo ratings yet

- Because I Could Not Stop For DeathDocument37 pagesBecause I Could Not Stop For DeathKenneth Arvin TabiosNo ratings yet

- Assignment 6 Acres and A ThirdDocument7 pagesAssignment 6 Acres and A ThirdTejaNo ratings yet

- Rupert BrookeDocument6 pagesRupert BrookehemalogeshNo ratings yet

- Coleridge Biographia Literaria: 3.0 ObjectivesDocument5 pagesColeridge Biographia Literaria: 3.0 ObjectivesSTANLEY RAYENNo ratings yet

- Abstract On "Dawn at Puri" by Jayanta MahapatraDocument10 pagesAbstract On "Dawn at Puri" by Jayanta MahapatraVada DemidovNo ratings yet

- The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock - StudyguideDocument6 pagesThe Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock - StudyguideChrista ChingMan LamNo ratings yet

- A View of Death in Emily Dickinson S BecDocument4 pagesA View of Death in Emily Dickinson S BecAeheris BlahNo ratings yet

- Indianness in Nissim EzekielDocument3 pagesIndianness in Nissim EzekielAniket BobdeNo ratings yet

- Digging by Seamus Heaney: Summary and AnalysisDocument1 pageDigging by Seamus Heaney: Summary and AnalysisTasnim Azam Moumi100% (1)

- Analysis of Sir Philip SidneyDocument2 pagesAnalysis of Sir Philip SidneyTaibur RahamanNo ratings yet

- All Poetry - 6th SemDocument17 pagesAll Poetry - 6th SemsahilNo ratings yet

- Essay On Dramatic Poesy Part22Document7 pagesEssay On Dramatic Poesy Part22Ebrahim Mohammed AlwuraafiNo ratings yet

- In Memory of WB YeatsDocument3 pagesIn Memory of WB YeatsBlueBoots15No ratings yet

- 1st Sem EnglishDocument14 pages1st Sem EnglishSoumiki GhoshNo ratings yet

- Themes in WDocument4 pagesThemes in Wirfanskipper786No ratings yet

- Dubliners: Modernist Avant-Garde Homer Stream of ConsciousnessDocument15 pagesDubliners: Modernist Avant-Garde Homer Stream of ConsciousnessMunteanDoliSiAtatNo ratings yet

- Ma 3Document6 pagesMa 3surendersinghmdnrNo ratings yet

- Musee de Beux ArtsDocument23 pagesMusee de Beux ArtsGaselo R Sta AnaNo ratings yet

- The Criticism of Nissim EzekielDocument6 pagesThe Criticism of Nissim EzekielKaushik RayNo ratings yet

- Riders To The Sea: A New Genre of Tragedy: Sibaprasad DuttaDocument5 pagesRiders To The Sea: A New Genre of Tragedy: Sibaprasad Duttaswayamdiptadas22No ratings yet

- BEG DSE 03 Block 02Document63 pagesBEG DSE 03 Block 02Pooja SharmaNo ratings yet

- Desires Come by The ThousandsDocument12 pagesDesires Come by The ThousandsSanah Ohsan100% (1)

- R.K.Narayan ThemesDocument17 pagesR.K.Narayan ThemesabinayaNo ratings yet

- There Is A Distinct Spiritual Flavour To The Verses of GitanjaliDocument12 pagesThere Is A Distinct Spiritual Flavour To The Verses of Gitanjaliashishnarain31No ratings yet

- Toru Dutt and Sarojini Naidu..Document9 pagesToru Dutt and Sarojini Naidu..veedarpNo ratings yet

- Longinus: On The SublimeDocument2 pagesLonginus: On The SublimeGenesis Aguilar100% (1)

- 073 Whitsun WeddingDocument1 page073 Whitsun WeddingDebmita Kar PoddarNo ratings yet

- Maurya As An Archetypal Figure in Riders To The Se112Document15 pagesMaurya As An Archetypal Figure in Riders To The Se112raskolinkov 120% (1)

- Philip Larkin Toads8585Document3 pagesPhilip Larkin Toads8585lisamarie1473No ratings yet

- JAYANTA MAHAPATRA'S POETRY - TMBhaskarDocument4 pagesJAYANTA MAHAPATRA'S POETRY - TMBhaskargksahu000100% (1)

- The Canonization by John Donne Essay Example For FreeDocument4 pagesThe Canonization by John Donne Essay Example For Freepriya royNo ratings yet

- There Is No Doubt ThatDocument4 pagesThere Is No Doubt ThatPamelaNo ratings yet

- Longinus As A CriticDocument6 pagesLonginus As A CriticJuma GullNo ratings yet

- Semi Detailed Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesSemi Detailed Lesson PlanslowmotioniraNo ratings yet

- Robert Greer Cohn (Ed.) - Mallarmé in The Twentieth Century - NodrmDocument325 pagesRobert Greer Cohn (Ed.) - Mallarmé in The Twentieth Century - NodrmXUNo ratings yet

- Summative Test English 9 Module 1 Lesson 4Document1 pageSummative Test English 9 Module 1 Lesson 4Argie Ray Ansino ButalidNo ratings yet

- Full Download Fundamentals of Phonetics A Practical Guide For Students 4Th Edition Ebook PDF Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full ChapterDocument23 pagesFull Download Fundamentals of Phonetics A Practical Guide For Students 4Th Edition Ebook PDF Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full Chapterbenjamin.waterman189100% (23)

- The Roaring TwentiesDocument17 pagesThe Roaring TwentiesAlexandraNicoarăNo ratings yet

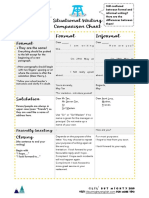

- LBM Situational Writing Comparison ChartDocument2 pagesLBM Situational Writing Comparison Chartngianbc5802No ratings yet

- Sentence Patterns 4-8Document8 pagesSentence Patterns 4-8sclarkgw100% (1)

- Popular NarrativeDocument13 pagesPopular NarrativeMEIMOONA HUSNAINNo ratings yet

- Problems With Chinese PhilosophyDocument7 pagesProblems With Chinese PhilosophyizhelNo ratings yet

- Elegy - NotesDocument2 pagesElegy - NotesCharu VaidNo ratings yet

- Red Rising Summary 1Document3 pagesRed Rising Summary 1JOSE MARIA ALONSO BALANZATEGUINo ratings yet

- Punjab & Andhra PradeshDocument28 pagesPunjab & Andhra PradeshguranshsaranNo ratings yet

- Gezelle - Works - Occasional Poetry - You Have Climbed The MountainsDocument4 pagesGezelle - Works - Occasional Poetry - You Have Climbed The MountainsoriginicsNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World Modules in This CourseDocument14 pages21st Century Literature From The Philippines and The World Modules in This CourseMa Glaiza MarasiganNo ratings yet

- (Love Song, With Two Goldfish) CommentaryDocument2 pages(Love Song, With Two Goldfish) CommentaryAlice Kayy92% (12)

- Essay 2 ReflectionDocument2 pagesEssay 2 Reflectionapi-582891715No ratings yet

- FLIT 3-Survey in The Philippine Literature in EnglishDocument4 pagesFLIT 3-Survey in The Philippine Literature in EnglishMarlon KingNo ratings yet

- Salya GanguliDocument139 pagesSalya GangulisoylentgreenNo ratings yet

- Unimex C 2 Unit 7 (4070) ContestadoDocument2 pagesUnimex C 2 Unit 7 (4070) Contestadomiguel angelNo ratings yet

- Board of Regents of The University of Wisconsin SystemDocument27 pagesBoard of Regents of The University of Wisconsin SystemАртём МорозовNo ratings yet

- Angel of The Sea (Darkness & Chaos)Document8 pagesAngel of The Sea (Darkness & Chaos)Agasif AhmedNo ratings yet

- (Download PDF) Critical Essays On Twin Peaks The Return Antonio Sanna Online Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument42 pages(Download PDF) Critical Essays On Twin Peaks The Return Antonio Sanna Online Ebook All Chapter PDFdustin.moore225100% (8)

- Nilai-Nilai Edukatif Dalam Lirik Nyanyian Onang-Onang Pada Acara Pernikahan Suku Batak Angkola Kabupaten Tapanuli Selatan Provinsi Sumatera UtaraDocument15 pagesNilai-Nilai Edukatif Dalam Lirik Nyanyian Onang-Onang Pada Acara Pernikahan Suku Batak Angkola Kabupaten Tapanuli Selatan Provinsi Sumatera UtaraFistiNo ratings yet