Professional Documents

Culture Documents

152373-1942-People v. Ching Kuan

152373-1942-People v. Ching Kuan

Uploaded by

Maria Rebecca Chua Ozaraga0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

60 views3 pagesThis document is a Supreme Court decision regarding a case where a man was fined for constructing a building without a permit. The Court upheld the fine of P175 imposed by the lower court. The Court explained that (1) considering the defendant's guilty plea as a mitigating circumstance was unnecessary since only a fine was imposed; and (2) article 66 of the Penal Code, which says fines should consider the defendant's wealth, aims for equality before the law since equal fines may be unequal punishment depending on one's income. The Court affirmed the fine, finding no error in the lower court's consideration of the defendant's financial ability to pay.

Original Description:

Original Title

152373-1942-People_v._Ching_Kuan

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document is a Supreme Court decision regarding a case where a man was fined for constructing a building without a permit. The Court upheld the fine of P175 imposed by the lower court. The Court explained that (1) considering the defendant's guilty plea as a mitigating circumstance was unnecessary since only a fine was imposed; and (2) article 66 of the Penal Code, which says fines should consider the defendant's wealth, aims for equality before the law since equal fines may be unequal punishment depending on one's income. The Court affirmed the fine, finding no error in the lower court's consideration of the defendant's financial ability to pay.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

60 views3 pages152373-1942-People v. Ching Kuan

152373-1942-People v. Ching Kuan

Uploaded by

Maria Rebecca Chua OzaragaThis document is a Supreme Court decision regarding a case where a man was fined for constructing a building without a permit. The Court upheld the fine of P175 imposed by the lower court. The Court explained that (1) considering the defendant's guilty plea as a mitigating circumstance was unnecessary since only a fine was imposed; and (2) article 66 of the Penal Code, which says fines should consider the defendant's wealth, aims for equality before the law since equal fines may be unequal punishment depending on one's income. The Court affirmed the fine, finding no error in the lower court's consideration of the defendant's financial ability to pay.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 3

FIRST DIVISION

[G.R. No. 48515. November 11, 1942.]

THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES , plaintiff-appellee, vs . CHING

KUAN , defendant-appellant.

Alfredo Feraren for appellant.

Solicitor-General De la Costa and Solicitor Kapunan, jr. for appellee.

SYLLABUS

1. CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE; REASON FOR IMPOSITION OF

UNEQUAL FINES UNDER ARTICLE 66 OF THE REVISED PENAL CODE. — Article 66 of

the Revised Penal Code does not discriminate between the rich and the poor when it

provides, among other things, that in xing the amount of nes attention shall be given

more particularly to the wealth or means of the culprit. It may seem paradoxical, but the

truth is that the codal provision in question, in authorizing the imposition of unequal

nes, aims precisely at equality before the law. Since a ne is imposed as penalty and

not as payment for a speci c loss or injury, and since its lightness or severity depends

upon the culprit's wealth or means, it is only just and proper that the latter be taken into

account in xing the amount. To an indigent laborer, for instance, earning P1.50 a day or

about P36 a month, a ne of P10 would undoubtedly be more severe than a ne of

P100 to an o ceholder or property owner with a monthly income of P600. Obviously,

to impose the same amount of a ne for the same offense upon two persons thus

differently circumstanced would be to mete out to them a penalty of unequal severity

and, hence, unjustly discriminatory.

2. ID.; ID.; EQUALITY BEFORE THE LAW. — This but goes to show that

equality before the law is not literal and mathematical but relative and practical. That is

necessarily so because human beings are not born equal and do not all start in life from

scratch; many have handicaps - material, physical, or intellectual. It is not within the

power of society to abolish such congenital inequality. All it can do by way of remedy is

to endeavor to afford everybody equal opportunity.

3. ID.; RULES CONCERNING AGGRAVATING AND MITIGATING

CIRCUMSTANCES NOT APPLICABLE WHEN PENALTY IMPOSED IS ONLY A FINE. — The

penalty imposed upon the appellant in the case at bar being only a ne, the rules

established in articles 63 and 64 of the Revised Penal Code concerning the presence of

aggravating and mitigating circumstances cannot be applied.

DECISION

OZAETA , J : p

Appellant was accused of a violation of section 86 of the Revised Ordinances of

the City of Manila in that on or about the 8th of May, 1941, he constructed a 297-

square-meter building of strong materials in the district of Tondo without the proper

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. 2018 cdasiaonline.com

permit from the city engineer. He pleaded guilty in the municipal court and was there

sentenced to pay a ne of P150 and the costs. He appealed to the Court of First

Instance, where he again pleaded guilty and was sentenced to pay a ne of P175, with

subsidiary imprisonment in case of insolvency, and the costs. Claiming that the ne

imposed on him was excessive, appellant has further appealed to this Court.

The penalty prescribed by section 1137 of the Revised Ordinances for the

violation committed by the accused is a ne of not more than P200 or imprisonment

for not more than six months, or both, in the discretion of the court. In other words the

maximum penalty that the court could have imposed was imprisonment for six months

and a fine of P200.

(1) Appellant urges us to take into consideration his plea of guilty as a

mitigating circumstance and to reverse our decisions in People vs. Durano, G. R. No.

45114, and People vs. Roque, G. R. No. 47561, in which we held that the rules of the

Revised Penal Code for the application of penalties when mitigating and aggravating

circumstances concur do not apply to a case where the accused is found guilty of the

violation of a special law and not of a crime penalized by said Code. (2) He also

contends that the trial court erred in taking into consideration his nancial ability to pay

the fine and that article 66 of the Revised Penal Code is unconstitutional.

1. As to the rst contention, we nd it unnecessary to reexamine or disturb

the decisions cited, because, the penalty imposed being only a ne, the rules

established in articles 63 and 64 of the Revised Penal Code concerning the presence of

aggravating and mitigating circumstances could not in any event be applied herein. If at

all, it would be article 66 of the same Code that should be applied. Said article reads as

follows:

"Art. 66. Imposition of nes . — In imposing nes the courts may x

any amount within the limits established by law; in xing the amount in each

case attention shall be given, not only to the mitigating and aggravating

circumstances, but more particularly to the wealth or means of the culprit."

2. So we proceed to pass upon appellant's second contention. The trial court

said:

"The accused in this case is well-to-do and could afford to pay a ne.

According to the attorney of the accused himself, he has a good business, and for

that reason he was able to construct a big building. In view thereof, the Court

believes that the penalty imposed by the Municipal Court is reasonable."

After quoting from article 66, counsel for the appellant says:

"As a consequence of this provision, when a ne has to be imposed, a poor

person will be required to pay less than one who is well-to-do, notwithstanding the

fact that both commit the same degree of violation of the law. In such case, the

above provision creates a discrimination between the rich and the poor, in the

sense of favoring the poor but not the rich, and thus causing unequal application

of the law. Consequently, the above provision is unconstitutional and void as

being a law which denies to all persons the equal protection of the laws . . ."

It may seem paradoxical, but the truth is that the codal provision in question, in

authorizing the imposition of unequal nes, aims precisely at equality before the law.

Since a ne is imposed as penalty and not as payment for a speci c loss or injury, and

since its lightness or severity depends upon the culprit's wealth or means, it is only just

and proper that the latter be taken into account in xing the amount. To an indigent

laborer, for instance, earning P1.50 a day or about P36 a month, a ne of P10 would

undoubtedly be more severe than a ne of P100 to an o ceholder or property owner

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. 2018 cdasiaonline.com

with a monthly income of P600. Obviously, to impose the same amount of a ne for the

same offense upon two persons thus differently circumstanced would be to mete out

to them a penalty of unequal severity and, hence, unjustly discriminatory.

This but goes to show that equality before the law is not literal and mathematical

but relative and practical. That is necessarily so because human beings are not born

equal and do not all start in life from scratch; many have handicaps — material, physical,

or intellectual. It is not within the power of society to abolish such congenital inequality.

All it can do by way of remedy is to endeavor to afford everybody equal opportunity.

The sentence appealed from is affirmed, with costs. So ordered.

Yulo, C.J., Moran, Paras, and Bocobo, JJ., concur.

CD Technologies Asia, Inc. 2018 cdasiaonline.com

You might also like

- CRIMINAL LAW - Estrada DOCsDocument10 pagesCRIMINAL LAW - Estrada DOCsMarko Kasaysayan100% (6)

- People VDocument20 pagesPeople VChris aribasNo ratings yet

- Ajeno vs. Inserto, 71 SCRA 166 (1976)Document3 pagesAjeno vs. Inserto, 71 SCRA 166 (1976)Rodolfo Villamer Tobias Jr.No ratings yet

- Santos To v. Cruz-Pano G.R. L-55130Document4 pagesSantos To v. Cruz-Pano G.R. L-55130Dino Bernard LapitanNo ratings yet

- Ivler vs. Modesto-San PedroDocument30 pagesIvler vs. Modesto-San PedroRay MacoteNo ratings yet

- Failure To Lend AssistanceDocument3 pagesFailure To Lend AssistanceNoelle Therese Gotidoc VedadNo ratings yet

- Leonilo Sanchez Alias Nilo, Appellant, vs. People of The Philippines and Court of AppealsDocument6 pagesLeonilo Sanchez Alias Nilo, Appellant, vs. People of The Philippines and Court of AppealsRap BaguioNo ratings yet

- Santos To V Cruz-PanoDocument3 pagesSantos To V Cruz-PanoBrian TomasNo ratings yet

- Reckless ImprudenceDocument29 pagesReckless ImprudenceKriska Herrero TumamakNo ratings yet

- 26ivler Vs Modesto-San Pedro, 635 SCRA 191, G.R. No. 172716, November 17, 2010Document40 pages26ivler Vs Modesto-San Pedro, 635 SCRA 191, G.R. No. 172716, November 17, 2010Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Claro M. Recto Assistant Solicitor General Guillermo E. Torres Solicitor Felixberto MilambilingDocument4 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Claro M. Recto Assistant Solicitor General Guillermo E. Torres Solicitor Felixberto MilambilingIsah Clarise LiliaNo ratings yet

- CD 121. Lito Corpuz v. People, G.R. No. 180016, April 29, 2014Document2 pagesCD 121. Lito Corpuz v. People, G.R. No. 180016, April 29, 2014JMae Magat100% (2)

- 249 Corpuz Vs PeopleDocument4 pages249 Corpuz Vs PeopleadeeNo ratings yet

- Bar Squad: Virtus Venustas IntegritasDocument10 pagesBar Squad: Virtus Venustas IntegritasChare MarcialNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Digests - ISL, PL, Art.89Document4 pagesCriminal Law Digests - ISL, PL, Art.89maccy adalidNo ratings yet

- Retroactive Effect of Laws Brings Good News To AccusedDocument3 pagesRetroactive Effect of Laws Brings Good News To AccusedKash K. AsdaonNo ratings yet

- General Provisions - Concept of DamagesDocument19 pagesGeneral Provisions - Concept of DamagesElica DiazNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE vs. Lacson, October 7, 2003Document4 pagesPEOPLE vs. Lacson, October 7, 2003Alan Nageena Arumpac MamutukNo ratings yet

- Bernardo Lacanilao vs. Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesBernardo Lacanilao vs. Court of Appealskim taboraNo ratings yet

- Reodica vs. CADocument14 pagesReodica vs. CAShiela BrownNo ratings yet

- People vs. DacuycuyDocument15 pagesPeople vs. DacuycuyChristine Karen BumanlagNo ratings yet

- A.M. No. 1098-CFIDocument2 pagesA.M. No. 1098-CFIPaolo CruzNo ratings yet

- Ivler Vs Modesto San PedroDocument22 pagesIvler Vs Modesto San PedroRay Lemuel AdajarNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 11555Document15 pagesG.R. No. 11555Chriscelle Ann PimentelNo ratings yet

- Bernardo Lacanilao Vs Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesBernardo Lacanilao Vs Court of AppealsDane DagatanNo ratings yet

- Corpuz Vs People Separate OpinionDocument57 pagesCorpuz Vs People Separate OpinionKristanne Louise YuNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-5790 - People vs. de La Cruz 92 Phil. 906 908Document2 pagesG.R. No. L-5790 - People vs. de La Cruz 92 Phil. 906 908HugeNo ratings yet

- Bearod - Atty. Axel CruzDocument13 pagesBearod - Atty. Axel CruzIsabella Rodriguez100% (2)

- En Banc: Syllabus SyllabusDocument6 pagesEn Banc: Syllabus SyllabusMargreth MontejoNo ratings yet

- Yuchengco vs. The Manila Chronicle Publishing Corporation GR No. 184315Document14 pagesYuchengco vs. The Manila Chronicle Publishing Corporation GR No. 184315Therese ElleNo ratings yet

- Rufino Nuñez Vs Sandiganbayan & The People of The PhilippinesDocument49 pagesRufino Nuñez Vs Sandiganbayan & The People of The PhilippinesZale CrudNo ratings yet

- People Vs Judge Auxencio C Dacuycuy 173 Scra 90Document3 pagesPeople Vs Judge Auxencio C Dacuycuy 173 Scra 90Kael MarmaladeNo ratings yet

- Ivler v. San PedroDocument2 pagesIvler v. San PedroMikaela Pamatmat100% (2)

- EXCESSIVE FINES Pp. Vs Dacuycuy & Agbanlog vs. Pp.Document3 pagesEXCESSIVE FINES Pp. Vs Dacuycuy & Agbanlog vs. Pp.Cel DelabahanNo ratings yet

- Ajeno Vs InsertoDocument1 pageAjeno Vs InsertoAiken Alagban LadinesNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Processual PresumptionDocument5 pagesDoctrine of Processual PresumptionFLORENCIO jr LiongNo ratings yet

- 850january 10, 2018Document18 pages850january 10, 2018Gi NoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 2 3 4 5Document62 pagesChapter 1 2 3 4 5Angel CabanNo ratings yet

- Torts Legal Paper - BunaganDocument14 pagesTorts Legal Paper - BunaganKristel Mae BunaganNo ratings yet

- Ynot vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument12 pagesYnot vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtLouie816No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 9601 September 29, 1914Document4 pagesG.R. No. 9601 September 29, 1914Jonathan WilderNo ratings yet

- Ynot vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtDocument12 pagesYnot vs. Intermediate Appellate CourtAngelie MercadoNo ratings yet

- Yuchengco vs. The Manila Chronicle Publishing Corporation GR No. 184315Document16 pagesYuchengco vs. The Manila Chronicle Publishing Corporation GR No. 184315Therese ElleNo ratings yet

- 127 - People V Garcia - 85 Phil 651Document6 pages127 - People V Garcia - 85 Phil 651IamtheLaughingmanNo ratings yet

- People V GarciaDocument4 pagesPeople V GarciaJem LicanoNo ratings yet

- Cojuangco Vs CADocument4 pagesCojuangco Vs CAjb_mesina100% (1)

- Lito Corpuz Vs People of The Philippines CASE DIGESTDocument4 pagesLito Corpuz Vs People of The Philippines CASE DIGESTCJ PonceNo ratings yet

- People V JuguetaDocument12 pagesPeople V JuguetaJeff Madrid100% (1)

- Petitioners vs. vs. Respondents: Third DivisionDocument23 pagesPetitioners vs. vs. Respondents: Third DivisionIsabel HigginsNo ratings yet

- U U U UDocument6 pagesU U U UPradeepan SasidharanNo ratings yet

- People Vs Gonzalez (1942)Document7 pagesPeople Vs Gonzalez (1942)nigel alinsugNo ratings yet

- Aclaracion Vs GatmaitanDocument4 pagesAclaracion Vs GatmaitanJosephine Berces100% (2)

- Criminal Law Review Case Digest - Fiscal GarciaDocument15 pagesCriminal Law Review Case Digest - Fiscal GarciaNeil MayorNo ratings yet

- People vs. CuelloDocument5 pagesPeople vs. CuellolictoledoNo ratings yet

- Ivler vs. Modesto-San PedroDocument15 pagesIvler vs. Modesto-San PedroNash LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Concept: Criminal Procedure Regulates The Steps by Which One Who Committed A Crime Is To Be PunishedDocument15 pagesConcept: Criminal Procedure Regulates The Steps by Which One Who Committed A Crime Is To Be PunishedKievan FakrizadehNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law II Notes and Cases BoadoDocument1,102 pagesCriminal Law II Notes and Cases BoadoEr33% (3)

- EL BANCO ESPAÑOL-FILIPINO, Plaintiff-Appellant, VICENTE PALANCA, Administrator of The Estate of Engracio Palanca TanquinyengDocument4 pagesEL BANCO ESPAÑOL-FILIPINO, Plaintiff-Appellant, VICENTE PALANCA, Administrator of The Estate of Engracio Palanca TanquinyengJohn Rey FerarenNo ratings yet

- The Illegal Causes and Legal Cure of Poverty: Lysander SpoonerFrom EverandThe Illegal Causes and Legal Cure of Poverty: Lysander SpoonerNo ratings yet

- 12 Asia - Pacific - Resources - International - Case DigestDocument3 pages12 Asia - Pacific - Resources - International - Case DigestMaria Rebecca Chua OzaragaNo ratings yet

- 3republit of Tbe Bilippines': Uprtmt OurtDocument10 pages3republit of Tbe Bilippines': Uprtmt OurtMaria Rebecca Chua OzaragaNo ratings yet

- Republic Act No. 9255: Home Civil Registration Civil Registration LawsDocument11 pagesRepublic Act No. 9255: Home Civil Registration Civil Registration LawsMaria Rebecca Chua OzaragaNo ratings yet

- 1 Manansala - v. - Marlow - Navigation - Phils. - GR 208314Document22 pages1 Manansala - v. - Marlow - Navigation - Phils. - GR 208314Maria Rebecca Chua OzaragaNo ratings yet

- 5 Magsaysay - Maritime - Corp. - v. - de - Jesus - GR 203943Document12 pages5 Magsaysay - Maritime - Corp. - v. - de - Jesus - GR 203943Maria Rebecca Chua OzaragaNo ratings yet

- Affordable Lazada Favorites Haul: Featured Budoleer: Rei GermarDocument5 pagesAffordable Lazada Favorites Haul: Featured Budoleer: Rei GermarMaria Rebecca Chua OzaragaNo ratings yet

- 0 A Toni Sia 11.11Document5 pages0 A Toni Sia 11.11Maria Rebecca Chua OzaragaNo ratings yet

- Petitioners Vs Vs Respondents Rodolfo A. Lockey Anacleto MontemayorDocument8 pagesPetitioners Vs Vs Respondents Rodolfo A. Lockey Anacleto MontemayorMaria Rebecca Chua OzaragaNo ratings yet

- Petitioners Vs VS: Second DivisionDocument10 pagesPetitioners Vs VS: Second DivisionMaria Rebecca Chua OzaragaNo ratings yet

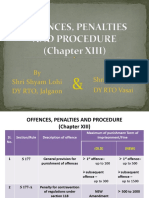

- Mva Offences, Penalties and ProcedureDocument47 pagesMva Offences, Penalties and ProcedureSagar SonawaneNo ratings yet

- Statutory ConstructionDocument53 pagesStatutory ConstructionDolores PulisNo ratings yet

- The Punjab Pure Food Ordinance, 1960Document16 pagesThe Punjab Pure Food Ordinance, 1960Waris ArslanNo ratings yet

- 2000-Ting v. Court of AppealsDocument10 pages2000-Ting v. Court of AppealsKathleen MartinNo ratings yet

- Rajasthan Public Gaming OrdinanceDocument9 pagesRajasthan Public Gaming OrdinanceJitendra Kumar BotharaNo ratings yet

- The Laws of The Federated Malay States 1877-1920 v3 1000311361Document815 pagesThe Laws of The Federated Malay States 1877-1920 v3 1000311361PetrMNo ratings yet

- Betty King Case Digest Stat ConDocument5 pagesBetty King Case Digest Stat ConAiko AbritoNo ratings yet

- Union JudiciaryDocument7 pagesUnion JudiciaryAman TiwariNo ratings yet

- Nrs Ecsa Profeng AppformDocument24 pagesNrs Ecsa Profeng AppformDjiems GauthierNo ratings yet

- Memorandum Nature of Affidavit - DMVDocument12 pagesMemorandum Nature of Affidavit - DMVGary Krimson100% (6)

- Section 233 IPCDocument4 pagesSection 233 IPCMOUSOM ROYNo ratings yet

- 1 EPF & Misc ActDocument17 pages1 EPF & Misc ActSipoy SatishNo ratings yet

- Sample ResolutionDocument3 pagesSample ResolutioncrimlawcasesNo ratings yet

- Professional Conduct InquiryDocument3 pagesProfessional Conduct InquiryAritra NandyNo ratings yet

- Supreme CourtDocument6 pagesSupreme CourtWestley AbluyenNo ratings yet

- Dpo 2018-03-000 (Anti Littering)Document5 pagesDpo 2018-03-000 (Anti Littering)Mary Chris100% (1)

- Ksce ActDocument20 pagesKsce ActFathima FarhathNo ratings yet

- Schuette Charges South East Michigan Man and His Company With Thirty-Five Felonies in Mortgage and Debt Management SchemeDocument3 pagesSchuette Charges South East Michigan Man and His Company With Thirty-Five Felonies in Mortgage and Debt Management SchemeMichigan NewsNo ratings yet

- Ra 3512Document3 pagesRa 3512givemeasign24No ratings yet

- Rule Iii Classification of Offenses and Schedule of PenaltiesDocument24 pagesRule Iii Classification of Offenses and Schedule of PenaltiesamadieuNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Factories Act (Ind. Law)Document118 pagesUnit 1 Factories Act (Ind. Law)Dinesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Arceo JR Vs People GR142641Document8 pagesArceo JR Vs People GR142641AnonymousNo ratings yet

- PAB ResolutionDocument27 pagesPAB Resolutionkat perezNo ratings yet

- Estafa and Criminal Negligence Under RA 10951Document5 pagesEstafa and Criminal Negligence Under RA 10951Jai HoNo ratings yet

- All Culpable Homicide Is Not Amounts To Murder, But All Murders Are Culpable HomicideDocument11 pagesAll Culpable Homicide Is Not Amounts To Murder, But All Murders Are Culpable HomicideinderpreetNo ratings yet

- Pesigan vs. AngelesDocument5 pagesPesigan vs. Angelescecee reyesNo ratings yet

- The Ocas Report and RecommendationDocument3 pagesThe Ocas Report and RecommendationcyhaaangelaaaNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Legal TermsDocument20 pagesGlossary of Legal TermsvovccristinaNo ratings yet

- Cases Under Katarungang PambarangayDocument10 pagesCases Under Katarungang PambarangayKathryn Crisostomo Punongbayan100% (1)