Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Communism, Feudalism, Capitalism

Communism, Feudalism, Capitalism

Uploaded by

zadanliranCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Communism, Feudalism, Capitalism

Communism, Feudalism, Capitalism

Uploaded by

zadanliranCopyright:

Available Formats

Vol 2, No 29

4 September

2000

CER INFO

front page Forward to

overview

sponsor us the Past

advertising Capitalism in post-Communist Europe

classifieds Sam Vaknin

submissions

jobs at CER

internships The core countries of Central Europe—the Czech Republic,

CER Direct Hungary and, to a lesser extent, Poland—employed industrial-

e-mail us capitalist systems during the inter-war period. But the countries

comprising the vast expanses of the Newly Independent States,

Russia and the Balkans had no real experience with such a

ARCHIVES system. To them, its zealous introduction was nothing but another

year 2000 ideological experiment, and not a very rewarding one at that.

year 1999

by subject It is often said that there was no precedent for the extant transition

by author from totalitarian Communism to liberal capitalism. This might well

kinoeye be true, yet nascent capitalism is not without historical examples.

books Thus, a discussion of the birth of capitalism in feudal Europe may

news lead to some surprising and potentially useful insights.

search

Insecurity and mayhem

MORE

ebookstore The Barbarian conquest of the teetering Roman Empire (410 to

pbookshop 476 AD) heralded five centuries of existential insecurity and

music shop mayhem. Feudalism was the countryside's reaction to this

video store damnation. It was a Hobson's choice and an explicit trade-off.

conferences Local lords defended their vassals against nomad intrusions in

diacritics return for perpetual service, which bordered on slavery. A small

FreeMail percentage of the population subsisted on trade behind the

papers massive walls of medieval cities.

links

In most parts of Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe,

feudalism endured well into the twentieth century. It was

entrenched in the legal systems of both the Ottoman Empire and

czarist Russia. Elements of feudalism survived in the mellifluous

and prolix prose of the Habsburg codices and patents. Most of the

denizens of these moribund swathes of Europe were farmers—

only the profligate and parasitic members of a distinct minority

inhabited the cities. The present agricultural sectors in countries as

diverse as Poland and Macedonia attest to this continuity of feudal

practices.

Toward an economic man

Both manual labour and trade were derided in the Ancient World.

This derision was partially eroded during the Dark Ages, and it

survived only in relation to trade and other "non-productive"

financial activities, but not past the thirteenth century. Max Weber,

in his opus The City (New York, MacMillan, 1958), described this

mental shift of paradigms thus: "The medieval citizen was on the

way towards becoming an economic man [...] the ancient citizen

was a political man."

What Communism did to the lands it permeated was to freeze this

early feudal frame of mind of disdain towards "non-productive,"

"city-based" vocations. Agricultural and industrial occupations were

romantically extolled. The cities were berated as hubs of moral

turpitude, decadence and greed. Political awareness was made a

precondition for personal survival and advancement. The clock

was turned back.

Weber's Homo economicus yielded to Communism's supercilious

version of the ancient Greeks' zoon politikon. John of Salisbury

might as well have been writing for a Communist agitprop

department when he penned this in Policraticus, in 1159 AD: "...if

[rich people, people with private property] have been stuffed

through excessive greed and if they hold in their contents too

obstinately, [they] give rise to countless and incurable illnesses

and, through their vices, can bring about the ruin of the body as a

whole." The body in the text being the body politic.

This inimical attitude should have come as no surprise to students

of either urban realities or of Communism, their parricidal off-

spring. The city liberated its citizens from the bondage of the feudal

labour contract, and it acted as the supreme guarantor of the rights

of private property. It relied on its trading and economic prowess to

obtain and secure political autonomy. John of Paris, arguably one

of the first capitalist cities (at least according to Braudel), wrote that

the individual "had a right to property which was not with impunity

to be interfered with by superior authority—because it was

acquired by [his] own efforts" (in Georges Duby, The Age of the

Cathedrals: Art and Society, 980-1420, Chicago, Chicago

University Press, 1981).

Despite the fact that Communism was an urban phenomenon

(albeit with rustic roots)—it abnegated these "bourgeois" values.

Communal ownership replaced individual property, and servitude

to the state replaced individualism. Under Communism, feudalism

was restored. Even geographical mobility was severely curtailed,

as was the case in feudal times. The doctrine of the Communist

party monopolized all modes of thought and perception—very

much the same as the Church-condoned religious strain did 700

years earlier. Communism was characterized by tensions between

party, state and the economy; exactly as the medieval polity was

plagued by conflicts between Church, king and merchant-bankers.

Paradoxically, Communism was a faithful re-enactment of pre-

capitalist history.

A distinction

Communism should be well-distinguished from Marxism, however.

Still, it is ironic that even Marx's "scientific materialism" has an

equivalent in the twilight times of feudalism. The eleventh and

twelfth centuries witnessed a concerted effort by medieval scholars

to apply "scientific" principles and human knowledge to the solution

of social problems. The historian R W Southern called this period

"scientific humanism" (in Flesh and Stone by Richard Sennett,

London, Faber and Faber, 1994).

John of Salisbury's Policraticus was an effort to map political

functions and interactions into their human physiological

equivalents. The king, for instance, was the brain of the body

politic. Merchants and bankers were the insatiable stomach. But

this apparently simplistic analogy masked a schismatic debate.

Should a person's position in life be determined by his political

affiliation and "natural" place in the order of things, or should it be

the result of his capacities and their exercise (merit)? Do the ever-

changing contents of the

economic "stomach," its kaleidoscopic

innovativeness, its "permanent revolution" and its

propensity to assume "irrational" risks adversely

affect this natural order, which, after all, is based

on tradition and routine? In short: is there an

inherent incompatibility between the order of the

world (read: the Church doctrine) and meritocratic (democratic)

capitalism? Could Thomas Aquinas' Summa Theologica (the world

as the body of Christ) be reconciled with Stadt Luft Macht Frei

("city air liberates" - the sign above the gates of the cities of the

Hanseatic League)?

Communism and Church

This is the eternal tension between the individual and the group.

Individualism and Communism are not new to history, and they

have always been in conflict. To compare the Communist Party to

the Church is a well-worn cliché. Both religions—the secular and

the divine— were threatened by the spirit of freedom and initiative

embodied in urban culture, commerce and finance. The order they

sought to establish, propagate and perpetuate conflicted with basic

human drives and desires.

Communism was a throwback to the days before the ascent of the

urbane, capitalistic, sophisticated, incredulous, individualistic and

risqué West. It sought to substitute one kind of "scientific"

determinism (the body politic of Christ) by another (the body politic

of "the Proletariat"). It failed, and when it unravelled, it revealed a

landscape of toxic devastation, frozen in time, an ossified natural

order bereft of content and adherents. The post-Communist

countries have to pick up where it left them, centuries ago. It is not

so much a problem of lacking infrastructure as it is an issue of

pathologized minds, not so much a matter of the body as a

dysfunction of the psyche.

Historian Walter Ullman says that John of Salisbury thought (850

years ago) that "the individual's standing within society... [should

be] based upon his office or his official function ... [the greater this

function was] the more scope it had, the weightier it was, the more

rights the individual had." (Walter Ullman, The Individual and

Society in the Middle Ages, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University

Press, 1966). I cannot conceive of a member of the Communist

nomenklatura who would not have adopted this formula

wholeheartedly. If modern capitalism can be described as "back to

the future," Communism was surely a "forward to the past."

Sam Vaknin, 4 September 2000

The author is General Manager of Capital Markets Institute Ltd, a

consultancy firm with operations in Macedonia and Russia. He is

an Economic Advisor to the Government of Macedonia.

DISCLAIMER: The views presented in this article represent only

the personal opinions and judgements of the author.

Moving on:

Archive of Sam Vaknin's articles in CER

Buy Sam Vaknin's After the Rain as an electronic book

Browse through the CER eBookstore for electronic

books

Buy English-language books on History through CER

Return to CER front page

You might also like

- Cold Therapy Seminar Level 1 Lecture NotesDocument10 pagesCold Therapy Seminar Level 1 Lecture Noteszadanliran100% (7)

- Anton Blok - The Mafia of A Sicilian Villiage, 1860-1960 - A Study of Violent Peasant Entrepreneurs-Harper (1974) PDFDocument330 pagesAnton Blok - The Mafia of A Sicilian Villiage, 1860-1960 - A Study of Violent Peasant Entrepreneurs-Harper (1974) PDFMaria Elena González Olayo100% (1)

- America's History Volume 1 Instructor's ManualDocument174 pagesAmerica's History Volume 1 Instructor's Manual112358j86% (7)

- Peter The Great DBQDocument4 pagesPeter The Great DBQapi-30532017167% (3)

- Ukraine-Russia Conflict EssayDocument1 pageUkraine-Russia Conflict EssayRiya CY100% (1)

- Coloniality The Darker Side of ModernityDocument6 pagesColoniality The Darker Side of ModernityMary Leisa Agda100% (1)

- Sam Vaknin's Autobiography (1961-1996) - Handwritten ManuscriptDocument243 pagesSam Vaknin's Autobiography (1961-1996) - Handwritten ManuscriptzadanliranNo ratings yet

- French Revolution Causes. Reading CompDocument4 pagesFrench Revolution Causes. Reading CompamayalibelulaNo ratings yet

- Wolin Revised 10-13 Benjamin Meets The CosmicsDocument27 pagesWolin Revised 10-13 Benjamin Meets The CosmicsMichel AmaryNo ratings yet

- 09 01 MorrisonDocument17 pages09 01 MorrisonAstelle R. LevantNo ratings yet

- The Transition Debate On The Origin of FeudalismDocument7 pagesThe Transition Debate On The Origin of FeudalismBisht SauminNo ratings yet

- Karl Polanyi Explains It AllDocument13 pagesKarl Polanyi Explains It AllThiên Phi TôNo ratings yet

- Chapter 21 Michael Harrington From Socialism Past and PresentDocument4 pagesChapter 21 Michael Harrington From Socialism Past and Presentekateryna249No ratings yet

- Collected Works of Marxism, Anarchism, Communism: The Communist Manifesto, Reform or Revolution, The Conquest of Bread, Anarchism: What it Really Stands For, The State and Revolution, Fascism: What It Is and How To Fight ItFrom EverandCollected Works of Marxism, Anarchism, Communism: The Communist Manifesto, Reform or Revolution, The Conquest of Bread, Anarchism: What it Really Stands For, The State and Revolution, Fascism: What It Is and How To Fight ItNo ratings yet

- Frank, W. José Carlos MariáteguiDocument4 pagesFrank, W. José Carlos MariáteguiErick Gonzalo Padilla SinchiNo ratings yet

- Biography: Nations, Perhaps The Most Influential Work Ever Written About Capitalism. Smith Explained How ADocument4 pagesBiography: Nations, Perhaps The Most Influential Work Ever Written About Capitalism. Smith Explained How AAlan AptonNo ratings yet

- Book Review Eric Hobsbawm Age of RevolutDocument2 pagesBook Review Eric Hobsbawm Age of RevolutPablo Benítez100% (1)

- The Stage of Modernity-MitchellDocument34 pagesThe Stage of Modernity-Mitchellmind.ashNo ratings yet

- PDF Roman Law and The Idea of Europe Incomplete Kaius Tuori Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Roman Law and The Idea of Europe Incomplete Kaius Tuori Ebook Full Chapterjoan.watkins250100% (1)

- Marxism and ImperialismDocument21 pagesMarxism and ImperialismMadanNo ratings yet

- Marxist View of ColonialismDocument9 pagesMarxist View of ColonialismEhsan VillaNo ratings yet

- The Communist Manufesto PDFDocument26 pagesThe Communist Manufesto PDFErmiasNo ratings yet

- Jack Goldestone - THE PROBLEM OF THE EARLY MODERN WORLD - TEXT PDFDocument36 pagesJack Goldestone - THE PROBLEM OF THE EARLY MODERN WORLD - TEXT PDFBojanNo ratings yet

- The Stage of Modernity-MitchellDocument34 pagesThe Stage of Modernity-MitchellAsijit DattaNo ratings yet

- V. G. Kiernan Marxism and Imperialism 1975Document136 pagesV. G. Kiernan Marxism and Imperialism 1975Rachel BrockNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx - The Communist ManifestoDocument58 pagesKarl Marx - The Communist ManifestoBogdan FedoNo ratings yet

- The Untold Slavery of Europe and The Communist's Manifesto: The Fundamental Principles of PoliticsFrom EverandThe Untold Slavery of Europe and The Communist's Manifesto: The Fundamental Principles of PoliticsNo ratings yet

- 1969 - Osborn - Review of Green-Belt CitiesDocument3 pages1969 - Osborn - Review of Green-Belt CitiesarghdelatableNo ratings yet

- Europe in Retrospect - A Brief History The Past Two Hundred YearsDocument33 pagesEurope in Retrospect - A Brief History The Past Two Hundred YearsDoobie ExNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Schmitt's "The Age of Neutralizations and Depoliticizations" (John E. McCormick)Document7 pagesIntroduction To Schmitt's "The Age of Neutralizations and Depoliticizations" (John E. McCormick)Isaac IconoclastaNo ratings yet

- Nurhadihhsusususussualdo PUKI PDFDocument62 pagesNurhadihhsusususussualdo PUKI PDFઝαżષyαNo ratings yet

- Nurhadialdo PUKI PDFDocument62 pagesNurhadialdo PUKI PDFઝαżષyαNo ratings yet

- Jeffrey Sachs 2Document12 pagesJeffrey Sachs 2sandisiwe dlomoNo ratings yet

- Communist Manifesto - Chapter 1 OnlyDocument11 pagesCommunist Manifesto - Chapter 1 OnlyMarissa NanceNo ratings yet

- Seminar-Paper - 1st - Abhinav Sinha - EnglishDocument58 pagesSeminar-Paper - 1st - Abhinav Sinha - EnglishSuresh Chavhan100% (1)

- DesaiDocument7 pagesDesaiLisandro MondinoNo ratings yet

- Magic Lantern Empire: Colonialism and Society in GermanyFrom EverandMagic Lantern Empire: Colonialism and Society in GermanyNo ratings yet

- Communist ManifestoDocument54 pagesCommunist ManifestoJoão NegroNo ratings yet

- Marxism and NationalismDocument22 pagesMarxism and NationalismApoorv AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Murphy 2Document4 pagesMurphy 2api-3835858No ratings yet

- McCloskey SlobodianLiteraryReview2018Document4 pagesMcCloskey SlobodianLiteraryReview2018Paul LinNo ratings yet

- Mandel, Ernest 1986 'The Place of Marxism in History' IIRF, Marxists - Org (46 PP.)Document46 pagesMandel, Ernest 1986 'The Place of Marxism in History' IIRF, Marxists - Org (46 PP.)voxpop88No ratings yet

- Heart of Darkness Intro and BackgroundDocument76 pagesHeart of Darkness Intro and BackgroundRebeh MALOUKNo ratings yet

- Marx and Engels - Communist Manifesto - ExcerptsDocument8 pagesMarx and Engels - Communist Manifesto - ExcerptsJuliana SheNo ratings yet

- Economic Mind Dorfman1Document541 pagesEconomic Mind Dorfman1Liz HackettNo ratings yet

- The Communist ManifestoDocument4 pagesThe Communist ManifestoValeria LeyceguiNo ratings yet

- MarxDocument13 pagesMarxUpsc StudyNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx - The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis BonaparteDocument114 pagesKarl Marx - The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis BonapartejeronimoxNo ratings yet

- Manifesto of The Communist PartyDocument15 pagesManifesto of The Communist PartyFergie LozanoNo ratings yet

- Kautsky, K., Communism in Central EuropeDocument379 pagesKautsky, K., Communism in Central EuropeRoland Jordan PerlitzNo ratings yet

- The Communist Manifesto PDFDocument83 pagesThe Communist Manifesto PDFiamnumber8No ratings yet

- Marx ColDocument3 pagesMarx Colsaira.aminNo ratings yet

- Communism in Central Europe in The Time of The ReformationDocument314 pagesCommunism in Central Europe in The Time of The ReformationArkadiusz Lorc100% (2)

- Malignant Self-Love: The Handwritten Manuscript (Hebrew, 1995)Document90 pagesMalignant Self-Love: The Handwritten Manuscript (Hebrew, 1995)zadanliranNo ratings yet

- Negativistic (Passive-Aggressive) Personality DisorderDocument3 pagesNegativistic (Passive-Aggressive) Personality DisorderzadanliranNo ratings yet

- Sam Vaknin Lectures and Seminars Topics: Economics, Finance, and PsychologyDocument4 pagesSam Vaknin Lectures and Seminars Topics: Economics, Finance, and PsychologyzadanliranNo ratings yet

- FIRST EVER Cold Therapy Certification Seminar in Vienna! REGISTER NOW!Document5 pagesFIRST EVER Cold Therapy Certification Seminar in Vienna! REGISTER NOW!zadanliran100% (1)

- The Archive MysteryDocument2 pagesThe Archive MysteryzadanliranNo ratings yet

- Smashwords Interview With Sam VakninDocument17 pagesSmashwords Interview With Sam Vakninzadanliran100% (2)

- Sam Vaknin's Workshop "How To Overcome Hurdles To Entrepreneurship: Fear, Greed, Envy, and Aggression"Document32 pagesSam Vaknin's Workshop "How To Overcome Hurdles To Entrepreneurship: Fear, Greed, Envy, and Aggression"Sam Vaknin100% (1)

- Britannica's Reference Galaxy 2016Document7 pagesBritannica's Reference Galaxy 2016zadanliranNo ratings yet

- Macedonian Economy On A Crossroads (MACEDONIAN)Document211 pagesMacedonian Economy On A Crossroads (MACEDONIAN)zadanliran100% (1)

- From Abuse To SuicideDocument5 pagesFrom Abuse To Suicidezadanliran100% (1)

- Requesting My Loved One (HEBREW)Document248 pagesRequesting My Loved One (HEBREW)zadanliranNo ratings yet

- 11th Annual and First International Battered Mothers Custody ConferenceDocument24 pages11th Annual and First International Battered Mothers Custody ConferencezadanliranNo ratings yet

- Table of Contents of Malignant Self-Love: Narcissism Revisited by Sam VakninDocument8 pagesTable of Contents of Malignant Self-Love: Narcissism Revisited by Sam VakninzadanliranNo ratings yet

- Chronon (Wikipedia)Document6 pagesChronon (Wikipedia)zadanliranNo ratings yet

- Psychology of Financial Crime and ScamsDocument2 pagesPsychology of Financial Crime and ScamszadanliranNo ratings yet

- Lecture HandoutDocument4 pagesLecture HandoutzadanliranNo ratings yet

- Guide To Divorcing The Narcissist, Psychopath, Bully, or StalkerDocument2 pagesGuide To Divorcing The Narcissist, Psychopath, Bully, or StalkerzadanliranNo ratings yet

- Narcissism and Psychopathy FREE Guides To IssuesDocument4 pagesNarcissism and Psychopathy FREE Guides To Issueszadanliran100% (1)

- Lone Wolf NarcissistDocument54 pagesLone Wolf Narcissistzadanliran100% (3)

- Glasnost and PerestroikaDocument5 pagesGlasnost and PerestroikaAnthony LuNo ratings yet

- Roman CrisisDocument5 pagesRoman CrisisVaibhavi PandeyNo ratings yet

- The Great War: The Sidney Bradshaw Fay Thesis Personal ResponseDocument4 pagesThe Great War: The Sidney Bradshaw Fay Thesis Personal ResponsePhas0077No ratings yet

- Unidad de Estudio México (En Español) MEXICAN HISTORY UNIT (SPANISH)Document44 pagesUnidad de Estudio México (En Español) MEXICAN HISTORY UNIT (SPANISH)Philip Pasmanick100% (1)

- Review Test For Unit III (1450-1750)Document9 pagesReview Test For Unit III (1450-1750)Alex McCrackenNo ratings yet

- Leaving Cert History Past Papers Essay Questions: Europe and The Wider World: Topic 3Document3 pagesLeaving Cert History Past Papers Essay Questions: Europe and The Wider World: Topic 3Sally MoynihanNo ratings yet

- Ar VW FS Ag 2017Document150 pagesAr VW FS Ag 2017Tangirala AshwiniNo ratings yet

- GLOBALIZATION - A Short History of The Modern World - Willian R. NesterDocument9 pagesGLOBALIZATION - A Short History of The Modern World - Willian R. NesterEdmilson MarquesNo ratings yet

- Like A MapDocument12 pagesLike A MapNila HernandezNo ratings yet

- My Friend PeterDocument2 pagesMy Friend PeterDonita Joy T. Eugenio0% (1)

- Industry Forecast MRO PDFDocument29 pagesIndustry Forecast MRO PDFtwj84100% (2)

- Compare The Policies and Methods Used by Otto Von Bismarck and Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel in Unification of Germany and Integration of States of India RespectivelyDocument5 pagesCompare The Policies and Methods Used by Otto Von Bismarck and Sardar Vallabh Bhai Patel in Unification of Germany and Integration of States of India RespectivelyHARINI. K.V.75% (4)

- Heartland TheoryDocument15 pagesHeartland TheoryShiv SuriNo ratings yet

- Croatia - Basic InformationDocument2 pagesCroatia - Basic Informationmedin321No ratings yet

- 1 PromisedlandDocument6 pages1 PromisedlandMin Hotep Tzaddik BeyNo ratings yet

- Infinite Craft Guide How To Make Europe in Infinite CraftDocument1 pageInfinite Craft Guide How To Make Europe in Infinite Craftfszp68btpbNo ratings yet

- Hussans ReviewerDocument5 pagesHussans ReviewerDiaren May NombreNo ratings yet

- Unification of Italy and GermanyDocument2 pagesUnification of Italy and Germanytuba player100% (2)

- Fuchs MWF Report - Europe PDFDocument30 pagesFuchs MWF Report - Europe PDFpriyagoswamiNo ratings yet

- Modern History: Tudor London (1485-1603)Document2 pagesModern History: Tudor London (1485-1603)RonaldNo ratings yet

- Burke 1980Document9 pagesBurke 1980shaheenfakeNo ratings yet

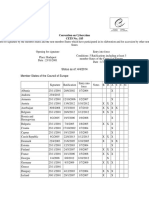

- Convention On Cybercrime CETS No.: 185Document3 pagesConvention On Cybercrime CETS No.: 185Vladimir3131No ratings yet

- Northern European Overture To War 1939 1Document536 pagesNorthern European Overture To War 1939 1Spaget 24No ratings yet

- SKANDERBEGDocument281 pagesSKANDERBEGArsim MulhaxhaNo ratings yet

- History of Religion in SloveniaDocument2 pagesHistory of Religion in SloveniaNoemiCiullaNo ratings yet