Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Correlating Parenting Styles With Child Behavior A

Correlating Parenting Styles With Child Behavior A

Uploaded by

Katherine SeptemberOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Correlating Parenting Styles With Child Behavior A

Correlating Parenting Styles With Child Behavior A

Uploaded by

Katherine SeptemberCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/266803388

Correlating Parenting Styles with Child Behavior and Caries

Conference Paper in Pediatric dentistry · March 2014

CITATIONS READS

13 554

6 authors, including:

Jeffrey Howenstein Daniel Lee Coury

3 PUBLICATIONS 62 CITATIONS

Nationwide Children's Hospital

124 PUBLICATIONS 2,244 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

SEE PROFILE

Han Yin

Taiho Oncology

24 PUBLICATIONS 205 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Autism Treatment Network View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Daniel Lee Coury on 01 April 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

HHS Public Access

Author manuscript

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Author Manuscript

Published in final edited form as:

Pediatr Dent. 2015 ; 37(1): 59–64.

Correlating Parenting Styles with Child Behavior and Caries

Dr. Jeff Howenstein, DMD, MS1, Dr. Ashok Kumar, DDS, MS2, Dr. Paul S. Casamassimo,

DDS, MS3, Dr. Dennis McTigue, DDS, MS4, Dr. Daniel Coury, MD5, and Dr. Han Yin, PhD6

1Pediatric dentist in private practice, Dakota Dunes, S.D

2Clinicalpediatric dental instructor, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, and associate professor of

pediatric dentistry, The Ohio State University

Author Manuscript

3Chief of dentistry, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, and professor and chair, Division of Pediatric

Dentistry and Oral Health, The Ohio State University

4Clinicalpediatric dental instructor, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, and associate professor of

pediatric dentistry, The Ohio State University

5Chiefof the Section of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Nationwide Children’s Hospital,

and professor of clinical pediatrics and psychiatry, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University

6Statistician, Biostats Core, Nationwide Children’s Hospital all in Columbus, Ohio, USA

Abstract

Purpose—This study evaluated the relationship between parenting style, sociodemographic data,

Author Manuscript

caries status, and child’s behavior during the first dental visit.

Methods—Parents/legal guardians of new patients aged three to six years presenting to

Nationwide Children’s Hospital dental clinic for an initial examination/hygiene appointment

completed the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) to assess parenting style

and a 15-question demographic survey. Blinded and calibrated expanded function dental

auxiliaries or dental hygienists (EFDA/DH) performed a prophylaxis and assessed child behavior

using the Frankl scale (inter-rater reliability was 92 percent). A blinded and calibrated dentist

performed an oral examination.

Results—132 parent/child dyads participated. Children with authoritative parents exhibited more

positive behavior (P<.001) and less caries (P<.001) compared to children with authoritarian and

permissive parents. Children attending daycare exhibited more positive behavior compared to

Author Manuscript

children who did not (P<.001). Patients with private dental insurance exhibited more positive

behavior (P>.04) and less caries (P>.024) compared to children with Medicaid or no dental

insurance.

Conclusions—Authoritative parenting and having private dental insurance were associated with

less caries and better behavior during the first dental visit. Attending daycare was associated with

better behavior during the first dental visit.

Correspond with Dr. Howenstein at jeffreyhowenstein@gmail.com.

Howenstein et al. Page 2

Author Manuscript

Keywords

PARENTING STYLES; CARIES; CHILD BEHAVIOR

A child’s behavior can make it challenging to provide effective dental treatment. Children

vary in their responses to the dental experience, which are influenced by health, culture,

parenting styles, age, cognitive level, anxiety and fear, reaction to strangers, pathology,

social expectations, and the temperament.1–9 Parents play a large role in how a child

behaves at the dental appointment, especially when they have had negative experiences with

dentists themselves. An anxious or fearful parent can negatively affect the child’s behavior

in the dental office.4,10

Parenting styles have been viewed with extreme interest recently. Parents, as primary

caregivers, exert a significant influence on the development of their child’s present and

Author Manuscript

future emotional health, personality, character,11 well-being, social and cognitive

development, and academic performance.12–18 Parenting style is an essential determinant of

children’s coping styles, and a child’s behavior toward adults varies according to different

parenting styles. This transfers to the dental office, affecting the interaction with the dentist.

Parenting style also influences how a child copes with stresses and stimuli, including those

in the dental setting.19

Baumrind defined three specific parenting styles: (1) authoritative; (2) authoritarian; and (3)

permissive (Table 1).18,20 The authoritarian (high control, low warmth) parenting style is

defined by harsh parenting practices, including physical punishment, yelling, and

commands.21 Children in authoritarian homes are often withdrawn and distrustful.18 The

authoritative (high warmth, high control) parent exhibits firm limit-setting, yet shows

Author Manuscript

compassion and warmth, and these households have bidirectional communication.21 The

permissive (high warmth, low control) parent provides few to no commands or limits to

behavior, and often spoils and coddles the child.21 Children in a permissive household are

“co-owners” of the house as far as rules go but have no responsibility.18

Lamborn describes another type of parenting style: neglectful. The neglectful style is

defined by low warmth and low control, and describes emotionally detached parents.14

These parents are typically not responsive and are uninvolved in their children’s lives. They

do not volunteer to be studied, so minimal research exists on this parenting style. Because of

the limited data on these families, the current study did not address the neglectful parenting

style.

The Diplomates of the American Board of Pediatric Dentistry agreed in 2002 that, during

Author Manuscript

their years of practicing dentistry, parenting styles had changed. Ninety-two percent felt

these changes were bad, and 85 percent felt these resulted in worse patient behaviors.22 This

evolution of parenting styles is documented in the current literature, specifically noting an

increase in indulgent parenting.15,23 These shifts have contributed to an increased potential

for dental disease, limited capacity of children to behave, and decreased parental control

over their child’s behavior.15 Specific behaviors can prolong the time in the dental chair or

create a need to use more advanced methods of behavior management, such as general

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 3

anesthesia. Poor behavior can delay necessary dental treatment, thus allowing further

Author Manuscript

progression of disease.

Parents today want to prevent their children from experiencing any pain or discomfort.

Sheller suggests this is a step away from the ‘traditional’ parenting techniques of setting

limits and saying ‘no’.23 Many parents are less accountable for behavior of their children

and provide less discipline, relying more on medical or psychological methods of

management.23 Parenting styles are changing, and pediatric dentists should be aware of

these changes to be prepared to treat each patient in the most efficient and effective manner.

Parenting styles influence the health of children. Childhood obesity and sugar consumption

are on the rise for children,24,25 and this is a concern for the oral and overall health of

children. Less obesigenic environments are associated with authoritative parenting.26

Another study indicates that obesity is most likely associated with authoritarian parenting,

Author Manuscript

and that children from indulgent homes have twice the risk of being obese than children

from authoritative homes.27 Parenting affects the child’s consumption of a sugary diet,28

and authoritative parents have healthier food choices for their children.29

Evidence supports a potential relationship between parenting styles, child behavior, and

dental caries, but limited research investigates this topic. The most relevant and closely

related publication is by Aminabadi et al., which showed a correlation between parenting

styles and the child’s behavior during a restorative dental visit.30 Aminabadi et al. gave

preliminary evidence that a child’s reaction to “restorative dental procedures is influenced

by the nature of the caregiver’s parenting style.”30 This publication also suggests that

permissive and authoritarian parenting styles are associated with much worse behavior than

the authoritative style.30 The limited literature on parenting styles suggests that little is

Author Manuscript

known about the effects of parenting on dental behaviors.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between parenting styles, the

child’s behavior in the dental setting, and caries status of the child.

Methods

Sample

This study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee of Nationwide Children’s

Hospital, Columbus, Ohio (IRB13-00266). The sample was drawn from patients presenting

to Nationwide Children’s Hospital for their first dental visit. Selection criteria for inclusion

were: three-to six-year-old patients; English-speaking; no known medical conditions

limiting the child’s cognitive development; no diagnosed chronic medical conditions; no

Author Manuscript

history of dental procedures elsewhere; no history of phobias related to the dental or medical

setting; no history of pain secondary to pulpitis; and no diagnosed behavior disorders.

Procedure

Patients were prescreened from the electronic health record (EHR) at Nationwide Children’s

Hospital upon scheduling in order to assess qualification for the study. They were

prescreened by a second-year dental student from The Ohio State University, Columbus,

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 4

who had no interaction with the parent/child dyad and was not involved in data collection.

Author Manuscript

Normal procedure for the first dental visit was followed: the expanded function dental

auxiliary or dental hygienist (EFDA/ DH) completed the dental cleaning and assessed

behavior, and a calibrated pediatric dentist or resident, who had no other interaction with the

parent/child dyad, performed the comprehensive examination and assessed caries status.

Caries status was then indicated as either ‘positive’, meaning caries was present, or

‘negative’, meaning caries was not present. The operators were blind to parenting style. The

parents of qualified patients were then given a description of the study by two of the

principal investigators. If parents agreed to participate and inclusion criteria were confirmed,

these same investigators obtained informed consent, and the parent filled out the Parenting

Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ) and an additional questionnaire.

Questionnaires were collected prior to the parent leaving. Two prospective study parents

declined to participate in the study because they had brought other young children. Data

Author Manuscript

from the questionnaires and EHR were transferred to a secure spreadsheet (Excel, Microsoft

Corp., Redmond, Wash., USA).

Instruments

The PSDQ31 contains 32 statements regarding different parent reactions to child behavior.

This shortened, validated, and reliable version was used in this study for convenience and

time considerations. This questionnaire assesses the parenting style based on Baumrind’s

primary parenting types: authoritarian; authoritative; and permissive.18 For example, ‘we

spoil our child’ correlates to the permissive parenting style, while ‘we give our child reasons

why rules should be obeyed’ correlates to the authoritative parenting style. Each parent was

asked to rank each statement on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 (1 equals never, 2 equals once in a

while, 3 equals half the time, 4 equals very often, and 5 equals always) as to how often they

Author Manuscript

and their spouse/significant other (if applicable) exhibited each behavior. “The internal

consistency-reliability of each question in the PSDQ is good to excellent, and both mothers

and fathers of school-age children can complete this questionnaire.”31

The scoring key of the PSDQ was used to classify parents into one of the three specific

parenting styles.20,31 For the authoritative parenting style, there are 15 items with a potential

range of scores from zero to 75. The authoritarian style includes 12 items with a potential

range of zero to 60. The permissive style includes five items with a potential range of zero to

25. An overall mean score in each parenting style category was calculated, and this score

determined the parent’s particular style; the highest mean score placed the parent in the

proper parenting category. This was used as the primary behavior rating scale.

The second part of the questionnaire involved individual data about the child and the family,

Author Manuscript

including: household income; educational level; marital status; health information; number

of children; daycare status; and social information.

A reliable and common behavior scale used in dentistry and research is the Frankl

scale,2,32,33 which has four potential rankings for the child’s behavior, including definitely

negative, negative, positive, and definitely positive.

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 5

Calibration procedures

Author Manuscript

A panel of four pediatric dental experts reviewed and validated a series of five videos

showing different young children’s behavior during dental visits. Before viewing the videos,

the dentists were trained and calibrated on the Frankl scale. Then, they reviewed the videos

independently and rated the behavior shown on each video. The reliability between doctors’

ratings was assessed by intraclass correlation coefficient and was equal to 1 (95 percent

confidence interval [CI], P<.001), thus validating the videos. Once these videos were

validated, the EFDA/DHs participating in the study were trained and calibrated on the

Frankl scale. The EFDA/DHs viewed the series of videos individually and rated the shown

behavior. The process was repeated for the EFDA/DHs a month later to determine their

intrarater reliability. Spearman’s correlation coefficient determined that the inter-rater

reliability was 92 percent (95 percent CI, P<.001) and intrarater reliability was 91 percent

(95 percent CI, P>.03).

Author Manuscript

Examining dentists used clinical and radiographic criteria to assess caries and were not

calibrated beyond clinical calibration. This exam was performed following the cleaning and

X-rays, consistent with procedures for a new patient exam.

Results

Data collection was completed for 132 parent/child dyads. The mean patient age was 4.25

years (±0.63 years). Eighty-seven parents (66 percent) exhibited authoritative parenting, 33

(25 percent) exhibited permissive parenting, 11 (eight percent) exhibited authoritarian

parenting, and one (one percent) exhibited permissive/authoritative parenting. The data set

for the single authoritative/permissive household was not included in the statistical analysis

to maintain discrete cohorts; hence, the sample for the analysis was 131. For 124 patients,

Author Manuscript

the mother was the respondent; for seven, the father was the respondent. Table 2 illustrates

the sociodemographic distribution gathered. Race was largely divided into Caucasian and

African American, so the other races (Somali, European, Asian, Hispanic, and Indian) were

combined into an ‘other’ category. For statistical analysis, behavior was dichotomized into

positive and negative by combining the two negative ratings into a single negative rating and

then doing the same with the two positive categories. Chi-squared analysis was used to

assess statistical significance.

Parenting style and behavior

Authoritative parenting style accounted for 81 children (93 percent) with positive behavior

and six children (seven percent) with negative behavior. Permissive parenting accounted for

19 children (58 percent) with positive behavior and 14 children (42 percent) with negative

Author Manuscript

behavior. Authoritarian parenting accounted for five children (45 percent) with positive

behavior and six children (55 percent) with negative behavior. Children with authoritative

parents exhibited significantly more positive behavior (P<.001) versus children with

authoritarian and permissive parents (Figure 1).

We were concerned that the age of the child could be a factor involved in this significant

difference. Figure 2 shows the distribution of child behavior with the mean age listed for

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 6

each behavior category. The prevalence of negative behavior was higher among three-to

Author Manuscript

four-year-olds (25 percent negative behavior) compared to five-to six-year-olds (19 percent

negative behavior), but the correlation between age and behavior was not statistically

significant (P=.51).

Parenting style and caries

Authoritative parenting accounted for 17 children (20 percent) with caries and 70 children

(80 percent) without caries. Permissive parenting accounted for 32 children (97 percent)

with caries and one child (three percent) without caries. Authoritarian parenting accounted

for 10 children (91 percent) with caries and one child (nine percent) without caries. Children

with authoritative parents had less caries (P<.001) compared to those with authoritarian and

permissive parents.

Author Manuscript

Daycare, insurance, caries, and behavior

Forty-one children (98 percent) who attended daycare showed positive behavior at the dental

office, while one child (one percent) did not. Of the children who did not attend daycare, 64

(72 percent) showed positive behavior while 25 (28 percent) showed negative behavior.

Children who attended daycare exhibited more positive behavior compared to those children

who did not (P<.001).

All children with private insurance (16 total) showed positive behavior, while none showed

negative behavior. Eighty-nine children (77 percent) with Medicaid or no insurance showed

positive behavior, while 26 (23 percent) showed negative behavior. Children with private

dental insurance exhibited more positive behavior (P>.04) than those with Medicaid or no

dental insurance.

Author Manuscript

Three children (19 percent) with private insurance had caries, while 13 children (81 percent)

did not. Fifty-six children (49 percent) with Medicaid or no insurance had caries, while 59

children (51 percent) did not. Children with private dental insurance exhibited less caries

(P>.02) versus those with Medicaid or no dental insurance.

Discussion

While anecdotal and popular press accounts relate parenting to behavior, this is one of the

first studies to examine the correlation between parenting styles and the child’s behavior and

caries in the dental office. A child’s personality and behavior are affected by numerous

factors, and the immediate family environment seems to have the greatest impact on the

child’s personality, development, and behavior.1–8,34 Current literature indicates that

Author Manuscript

authoritative parenting has the most consistently positive impact on children. The current

study found that authoritative parenting was associated with more desirable child behavior

and less dental caries compared to the other two parenting styles. This is consistent with

psychological research, which suggests that children in authoritative households have

happier dispositions, greater emotional control and regulation, and improved social skills,18

all of which would suggest they would behave better at the dental office. This is also

consistent with Aminabadi et al.’s finding that authoritative parenting was associated with

improved child behavior compared to authoritarian and permissive parenting.30

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 7

We found that permissive parenting was associated with worse behavior and increased

Author Manuscript

caries. This is consistent with current research, specifically Aminabadi’s finding that

permissive parenting resulted in worse child behavior in the dental chair during a restorative

dental visit.30 Permissive parents let a child make decisions, and the caregiver tries to keep

the child happy, often with bribery.18 When put into the dental setting, the child can choose

to misbehave, and the parent provides comfort without consequence or punishment. The

increased caries in permissive households could be attributed to the fact that the child may

be able to eat and drink cariogenic foods unabatedly and can also choose whether or not to

brush teeth at home without expectation of discipline/enforcement.15,23

Our research indicated an association between authoritarian parenting and increased caries

and less cooperative patient behavior in the dental office. This is consistent with Aminabadi

et al., who found that authoritarian parenting results in less cooperative behavior during a

restorative dental visit.30 Children in authoritarian homes often have difficulty in social

Author Manuscript

situations and act fearful or shy around others, which could explain the poor behavior in the

dental office.18 The increased caries in this group seems to contradict what would be

suggested by typical authoritarian homes (i.e., strict rules). If strict rules were created to get

children to brush teeth and adhere to a specific diet, then these children would abide by these

rules. Our findings could suggest that oral health is not a priority for these families. Another

possible explanation may be that oral hygiene and diet measures are not reinforced due to

the low parental responsiveness exhibited in these households. The number of authoritarian

households was limited in this study compared to authoritative and permissive households,

and an increased sample size in a future study could help clarify these findings.

Our study also showed that private insurance was associated with better behavior and less

dental caries compared to Medicaid. These results are consistent with the current literature,

Author Manuscript

which reports increased caries prevalence35 and increased behavior problems in children

with low socioeconomic status.36,37 It would have been interesting to assess parental history

of caries to compare to socioeconomic status and child caries; it has been shown that

parental history of caries is associated with early childhood caries.38

An interesting finding in our research was that daycare attendance was associated with better

behavior. This contradicts current research, which suggests that increased time in daycare is

negatively associated with social development, thus causing worse child behavior.39 For

many preschool children, meeting new people (especially adults) may be difficult. This

would be increasingly difficult if they were not used to interacting with people outside their

family on a regular basis. Our findings suggest that early interaction with other children and

adults at daycare may have a positive effect on their behavior at the dentist, perhaps because

Author Manuscript

of an acquired ability to interact with strangers and adults.

A limitation of the study was that subjects represented a convenience sample of patients

presenting to the dental clinic at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Also, since the sample was

small, only three main parenting styles were used to categorize the parenting. This led to

exclusion of other potential styles conceptualized by psychologists, including neglectful.

Another limitation was the potential selection bias: there were mostly authoritative parents

(Table 2). However, this could be a normal distribution for our population; the studies

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 8

similar to the present study do report a higher prevalence of the authoritative parenting style,

Author Manuscript

but there is no study reporting a clear indication of the prevalence of each parenting style in

the U.S.A.15 The high percentage of authoritative parents could be explained by the

possibility that mostly authoritative parents bring their children to the dentist compared to

the other parenting styles.

This would be an interesting topic to research further, correlating with other

sociodemographic information. Approximately 80 percent of the children behaved positively

at the first dental visit (Figure 2). This could be explained by the fact that this study used a

noninvasive dental appointment. Older children showed a higher prevalence of positive

behavior, which is consistent with previous research and intuition.1,40 An interesting future

topic to research would be to note if there are differences in parenting styles, social data, and

caries status of patients who arrive as walk-in emergencies versus those in the present study,

who presented without pain for a routine first examination and cleaning.

Author Manuscript

Future research is needed to further investigate the relationship between parenting styles,

child behavior, and caries in the pediatric dental setting. A large sample size from different

populations would be beneficial to confirm this study’s results. Future research could

complement the current study to develop a model for predictors of certain child behavior

and oral health.

Conclusions

Based on this study’s results, the following conclusions can be made:

1. Authoritative parenting and private dental insurance were associated with less

caries and better behavior during the first dental visit.

Author Manuscript

2. Attending daycare was associated with better behavior during the first dental visit

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by Award Number Grant UL1TR001070 from the National Center For

Advancing Transitional Sciences. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily

represent the official views of the National Center For Advancing Transitional Sciences or the National Institutes of

Health.

References

1. Allen KD, Hutfless S, Larzelere R. Evaluation of two predictors of child disruptive behavior during

restorative dental treatment. J Dent Child. 2003; 70:221–5.

2. American Academy on Pediatric Dentistry Clinical Affairs Committee. . Guideline on behavior

Author Manuscript

guidance for the pediatric dental patient. Pediatr Dent. 2008; 30(suppl):125–33. [PubMed:

19216411]

3. Arnrup K, Broberg AG, Berggren U, Bodin L. Lack of cooperation in pediatric dentistry: the role of

child personality characteristics. Pediatr Dent. 2002; 24:119–28. [PubMed: 11991314]

4. Baier K, Milgrom P, Russell S, Mancl L, Yoshida T. Children’s fear and behavior in private

pediatric dentistry practices. Pediatr Dent. 2004; 26:316–21. [PubMed: 15344624]

5. Brill WA. The effect of restorative treatment on children’s behavior at the first recall visit in a

private pediatric dental practice. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2002; 26:389–93. [PubMed: 12175134]

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 9

6. Carey WB. Teaching parents about infant temperament. Pediatrics. 1998; 102(suppl E):1311–6.

[PubMed: 9794975]

Author Manuscript

7. Klingberg G, Broberg AG. Temperament and child dental fear. Pediatr Dent. 1998; 20:237–43.

[PubMed: 9783293]

8. Rud B, Kisling E. The influence of mental development on children’s acceptance of dental

treatment. Scand J Dent Res. 1973; 81:343–52. [PubMed: 4519551]

9. Gustafsson A, Broberg A, Bodin L, Berggren U, Arnrup K. Dental behaviour management

problems: the role of child personal characteristics. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2010; 20:242–53. [PubMed:

20536585]

10. Klingberg G, Berggren U. Dental problem behaviors in children of parents with severe dental fear.

Swed Dent J. 1992; 16:27–32. [PubMed: 1579885]

11. Baumrind D. Parental disciplinary patterns and social competence in children. Youth Soc. 1978;

9:239–251.

12. DeVore ER, Ginsburg KR. The protective effects of good parenting on adolescents. Curr Opin

Pediatr. 2005; 17:460–5. [PubMed: 16012256]

13. Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman PH, Roberts DF, Fraleigh MJ. The relation of parenting style

Author Manuscript

to adolescent school performance. Child Dev. 1987; 58:1244–57. [PubMed: 3665643]

14. Lamborn S, Mounts N, Steinberg L, Dornbusch S. Patterns of competence and adjustment among

adolescents from authoritative, authoritarian, indulgent, and neglectful families. Child Dev. 1991;

62:17.

15. Law CS. The impact of changing parenting styles on the advancement of pediatric oral health. J

Calif Dent Assoc. 2007; 35:192–7. [PubMed: 17679305]

16. Rytkonen K, Aunola K, Nurmi J. Parents’ causal attributions concerning their children’s school

achievement: a longitudinal study. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2005; 51:20.

17. Cohen DA, Rice J. Parenting styles, adolescent substance abuse, and academic achievement. J

Drug Educ. 1997; 27:199–211. [PubMed: 9270213]

18. Baumrind D. Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol Monogr. 1971; 4:1–103.

19. Bailey PM, Talbot A, Taylor PP. A comparison of maternal anxiety levels with anxiety levels

manifested in the child dental patient. J Dent Child. 1973; 40:277–84.

20. Robinson C, Mandleco B, Olsen SF, Hart CH. The parenting styles and dimensions questionnaire

Author Manuscript

(PSDQ). Handb Fam Meas Tech. 2001; 3:319–21.

21. Querido JG, Warner TD, Eyberg SM. Parenting styles and child behavior in African American

families of preschool children. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002; 31:272–7. [PubMed:

12056110]

22. Casamassimo PS, Wilson S, Gross L. Effects of changing U.S. parenting styles on dental practice:

perceptions of diplomates of the American Board of Pediatric Dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 2002;

24:18–22. [PubMed: 11874053]

23. Sheller B. Challenges of managing child behavior in the 21st century dental setting. Pediatr Dent.

2004; 26:111–3. [PubMed: 15132271]

24. O’Connor TM, Yang SJ, Nicklas TA. Beverage intake among preschool children and its effect on

weight status. Pediatrics. 2006; 118:e1010–e1018. [PubMed: 17015497]

25. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of

overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006; 295:1549–55. [PubMed:

16595758]

Author Manuscript

26. Johnson R, Welk G, Saint-Maurice PF, Ihmels M. Parenting styles and home obesogenic

environments. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012; 9:1411–26. [PubMed: 22690202]

27. Decaluwe V, Braet C, Moens E, Van Vlierberghe L. The association of parental characteristics and

psychological problems in obese youngsters. Int J Obes (Lond). 2006; 30:1766–74. [PubMed:

16607384]

28. Lopez NV, Ayala GX, Corder K, et al. Parent support and parent-mediated behaviors are

associated with children’s sugary beverage consumption. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012; 112:541–7.

[PubMed: 22709703]

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 10

29. Golan M, Crow S. Parents are key players in the prevention and treatment of weight-related

problems. Nutr Rev. 2004; 62:39–50. [PubMed: 14995056]

Author Manuscript

30. Aminabadi NA, Farahani RM. Correlation of parenting style and pediatric behavior guidance

strategies in the dental setting: preliminary findings. Acta Odontol Scand. 2008; 66:99–104.

[PubMed: 18446551]

31. Robinson C, Mandleco B. Authoritative, authoritarian, and permissive parenting practices:

development of a new measure. Psychol Rep. 1995; 77:1.

32. Klingberg G, Broberg AG. Dental fear/anxiety and dental behaviour management problems in

children and adolescents: a review of prevalence and concomitant psychological factors. Int J

Paediatr Dent. 2007; 17:391–406. [PubMed: 17935593]

33. Wright, GZ.; Stigers, JI. McDonald and Avery’s Dentistry for the Child and Adolescent. 9.

Maryland Heights, Mo: Mosby-Elsevier; 2011. Nonpharmacologic management of children’s

behavior; p. 27-40.

34. Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: an integrative model. Psychol Bull. 1993;

113:487–96.

35. Vargas CM, Crall JJ, Schneider DA. Sociodemographic distribution of pediatric dental caries:

Author Manuscript

NHANES III, 1988–1994. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998; 129:1229–38. [PubMed: 9766104]

36. Molnar BE, Cerda M, Roberts AL, Buka SL. Effects of neighborhood resources on aggressive and

delinquent behaviors among urban youths. Am J Public Health. 2008; 98:1086–93. [PubMed:

17901441]

37. Spencer N, Thanh TM, Seguin L. Low income/socioeconomic status in early childhood and

physical health in later childhood/adolescence: a systematc reviw. Maten Child Health J. 2013;

17(3):424–31.

38. Thitasomakul S, Piwat S, Thearmontree A, Chankanka O, Pithpornchaiyakul W, Madyusoh S.

Risks for early childhood caries analyzed by negative binomial models. J Dent Res. 2009; 88:137–

41. [PubMed: 19278984]

39. Belsky J, Vandell DL, Burchinal M, et al. Are there long-term effects of early child care? Child

Dev. 2007; 78:681–701. [PubMed: 17381797]

40. Brill WA. Child behavior in a private pediatric dental practice associated with types of visits, age

and socioeconomic factors. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2000; 25:1–7. [PubMed: 11314346]

Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 11

Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript

Figure 1.

Percentage of children with positive behavior by parenting style

* Significant difference (P<.0001).

Author Manuscript

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 12

Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript

Figure 2.

Behavior distribution with mean age and N value listed by category

* No significant difference (P=.51).

Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Howenstein et al. Page 13

Table 1

DESCRIPTION OF PARENTING STYLES

Author Manuscript

Parenting style Description

Authoritative High parental responsiveness and high parental demand; warmth and involvement, reasoning/induction, demographic

participation

Authoritarian Low parental responsiveness but high parental demand; clear parental authority, unquestioning obedience and punitive

strategies

Permissive High parental responsiveness but low parental demand; tolerance, general acceptance of child’s decisions and tendencies to

ignore child’s misbehavior

Neglecting Low parental responsiveness and low parental demand

Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript

Author Manuscript

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript Author Manuscript

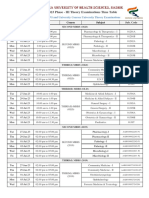

Table 2

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION

View publication stats

Subject’s gender N % Parent’s gender N %

Male 72 55 Male 7 5

Howenstein et al.

Female 59 45 Female 124 95

Attended daycare Parent’s race

No 88 67 African American 48 37

Yes 43 33 Caucasian 69 53

Caries status Other 14 10

No 72 55 Parent’s education

Yes 59 45 Less than high school diploma 23 18

Parenting style High school diploma 39 30

Authoritative 87 66 ≥1 y college 69 52

Permissive 33 25 Insurance type

Authoritarian 11 9 Private 16 12

Medicaid or no insurance 115 88

Total 131 100 131 100

Pediatr Dent. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2015 September 03.

Page 14

You might also like

- Temporary Anchorage Devices - NandaDocument435 pagesTemporary Anchorage Devices - NandaAmrita Shrestha100% (5)

- Piezoelectric Bone Surgery A New ParadigmDocument386 pagesPiezoelectric Bone Surgery A New ParadigmMihalache Catalin100% (1)

- The SAC Classification in Implant DentistryDocument266 pagesThe SAC Classification in Implant DentistryNiaz Ahammed100% (4)

- Sop Oral Surgeons AMADocument76 pagesSop Oral Surgeons AMAJassel DurdenNo ratings yet

- Correlating Parenting Styles With Child Behavior and CariesDocument7 pagesCorrelating Parenting Styles With Child Behavior and CariesAndrea Mariel RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Parenting Style in Pediatric Dentistry PDFDocument7 pagesParenting Style in Pediatric Dentistry PDFJude Aldo PaulNo ratings yet

- Basic Behaviour Guidance Factors and Techniques For Effective Child Management in Dental Clinic - An Update Review PDFDocument6 pagesBasic Behaviour Guidance Factors and Techniques For Effective Child Management in Dental Clinic - An Update Review PDFmadhuri nikamNo ratings yet

- Brodzinsky, 2011, Children's Understanding of AdoptionDocument9 pagesBrodzinsky, 2011, Children's Understanding of AdoptioncristianNo ratings yet

- Religiosity Is Associated With Caregivers PerceptDocument9 pagesReligiosity Is Associated With Caregivers PerceptMemex papNo ratings yet

- Types of Parenting Styles and Effects On Children - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument4 pagesTypes of Parenting Styles and Effects On Children - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfAna BarbosaNo ratings yet

- Young Children PDFDocument8 pagesYoung Children PDFfotinimavr94No ratings yet

- Berzinski 2019Document10 pagesBerzinski 2019mayac4811No ratings yet

- Types of Parenting Styles and Effects On Children - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument4 pagesTypes of Parenting Styles and Effects On Children - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfAdrianne Marie PinedaNo ratings yet

- Developmental Correlates Persistent Snoring in Preschool Children: Predictors and Behavioral andDocument10 pagesDevelopmental Correlates Persistent Snoring in Preschool Children: Predictors and Behavioral andsambalikadzilla6052No ratings yet

- Stein Cermak2012OralcareexperiencesinASDDocument6 pagesStein Cermak2012OralcareexperiencesinASDzsazsa nissaNo ratings yet

- Subha RamaswamyDocument159 pagesSubha RamaswamyAkanksha jainNo ratings yet

- Nonpharmacologic Management of Children's Behaviors: Chapter OutlineDocument16 pagesNonpharmacologic Management of Children's Behaviors: Chapter OutlineMuhammed HassanNo ratings yet

- 3679-Article Text-24641-1-10-20230329Document10 pages3679-Article Text-24641-1-10-20230329Muhammad ahmadNo ratings yet

- Effectsof Early NeglectonlanguageandcognitionDocument9 pagesEffectsof Early NeglectonlanguageandcognitionFARHAT HAJERNo ratings yet

- 2611 Inglehart5Document8 pages2611 Inglehart5Supriya BhataraNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Well-Being of Parents of Children With Oral CleftsDocument9 pagesPsychosocial Well-Being of Parents of Children With Oral CleftsSalma BibiNo ratings yet

- Tgs Bhs InggrisDocument7 pagesTgs Bhs InggrisAchmad HafirulNo ratings yet

- cs1 Annotated BibDocument10 pagescs1 Annotated Bibapi-417984366No ratings yet

- Alonso2019 - Reconhecimento CrençasDocument8 pagesAlonso2019 - Reconhecimento CrençasLoladaNo ratings yet

- Disruptive Beh ScriptDocument6 pagesDisruptive Beh ScriptJanine Erica De LunaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pediatrics: Parental Perspectives of Early Childhood CariesDocument10 pagesClinical Pediatrics: Parental Perspectives of Early Childhood CariesBasant ShamsNo ratings yet

- AED 222 The Controversy of MedicationDocument3 pagesAED 222 The Controversy of MedicationTonya HawkinsNo ratings yet

- Oral Care Experiences and Challenges For Children With Down Syndrome - Reports From CaregiversDocument12 pagesOral Care Experiences and Challenges For Children With Down Syndrome - Reports From CaregiverssssssNo ratings yet

- Parenting of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordeDocument15 pagesParenting of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordePollyanne AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Lec 3 5th 2020Document11 pagesLec 3 5th 2020Sajad AliraqinnnNo ratings yet

- Eng Research Body FinalDocument57 pagesEng Research Body FinalDarren Chelsea PacienciaNo ratings yet

- Parents' Experiences of Living With A Child With A Long-Term Condition: A Rapid Structured Review of The LiteratureDocument23 pagesParents' Experiences of Living With A Child With A Long-Term Condition: A Rapid Structured Review of The LiteratureSalman ArshadNo ratings yet

- (2013) - Terapia de Interacción Entre Padres e Hijos. Una Intervención Manualizada para El Sector Del Bienestar Infantil TerapéuticoDocument7 pages(2013) - Terapia de Interacción Entre Padres e Hijos. Una Intervención Manualizada para El Sector Del Bienestar Infantil TerapéuticoNAYELI MENDOZA FRIASNo ratings yet

- Emotional Distress Resilience and Adaptability A Qualitative Study of Adults Who Experienced Infant AbandonmentDocument18 pagesEmotional Distress Resilience and Adaptability A Qualitative Study of Adults Who Experienced Infant AbandonmentLoredana Pirghie AntonNo ratings yet

- Empirical Evidence of The Relationship Between Parental and Child Dental Fear: A Structured Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument20 pagesEmpirical Evidence of The Relationship Between Parental and Child Dental Fear: A Structured Review and Meta-AnalysisNabila RizkikaNo ratings yet

- 2015 Children With Chronic Conditions Perspectives On Condition ManagementDocument11 pages2015 Children With Chronic Conditions Perspectives On Condition ManagementDeanisa HasanahNo ratings yet

- SDLS 2008 PediatricsDocument7 pagesSDLS 2008 PediatricsmzerrahNo ratings yet

- Parenting Practices Across CulturesDocument18 pagesParenting Practices Across CulturesAmmara Haq100% (1)

- J Public Health Dent - 2020 - Alrashdi - Education Intervention With Respect To The Oral Health Knowledge Attitude andDocument10 pagesJ Public Health Dent - 2020 - Alrashdi - Education Intervention With Respect To The Oral Health Knowledge Attitude andGauri AtwalNo ratings yet

- To Develop A Set of Recommendations For Parents Whose Children Are in The Early Adolescent Age GroupDocument3 pagesTo Develop A Set of Recommendations For Parents Whose Children Are in The Early Adolescent Age GroupIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Adair Steven Behavier ManagementDocument4 pagesAdair Steven Behavier ManagementLiz GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Ethical Family Interv Obesity-1Document3 pagesEthical Family Interv Obesity-1Salma ChavanaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document25 pagesChapter 2Farah ZailaniNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Parents and Health Care Professionals Toward Active Treatment of Extremely Premature InfantsDocument8 pagesAttitudes of Parents and Health Care Professionals Toward Active Treatment of Extremely Premature InfantsAnnitaCristalNo ratings yet

- Behavsci 05 00461Document16 pagesBehavsci 05 00461NedNo ratings yet

- PCIT Plus Motivational interviewing-Nzi,+Lucash,+Clionsky,+Eyberg-2016Document11 pagesPCIT Plus Motivational interviewing-Nzi,+Lucash,+Clionsky,+Eyberg-2016Brenda KochNo ratings yet

- Blackwell Publishing LTD Psychosocial Concomitants To Dental Fear and Behaviour Management ProblemsDocument11 pagesBlackwell Publishing LTD Psychosocial Concomitants To Dental Fear and Behaviour Management ProblemsDra. María José CastilloNo ratings yet

- Fs 2Document2 pagesFs 2Zeynu KulizeynNo ratings yet

- Non-pharmacological behaviour management - 副本Document37 pagesNon-pharmacological behaviour management - 副本刘雨樵No ratings yet

- Chapter One Introduction 1.1 BackgroundDocument9 pagesChapter One Introduction 1.1 BackgroundEshetu DesalegnNo ratings yet

- Terapia de Interacción Padre-Hijo. MaltratoDocument7 pagesTerapia de Interacción Padre-Hijo. MaltratoJorge Mario Sarmientoperez VillarrealNo ratings yet

- Parenting Styles and Child Social DevelopmentDocument3 pagesParenting Styles and Child Social DevelopmentAndra Anamaria Negrici100% (1)

- Evidence Base For DIR 2020Document13 pagesEvidence Base For DIR 2020MP MartinsNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Oral Health Behavior of Parents As A Predictor of Oral Health Status of Their ChildrenDocument6 pagesResearch Article: Oral Health Behavior of Parents As A Predictor of Oral Health Status of Their ChildrenManjeevNo ratings yet

- 250 FullDocument12 pages250 FullSonia DzierzyńskaNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its Setting Background of The StudyDocument32 pagesThe Problem and Its Setting Background of The StudyGillian Alexis ColegadoNo ratings yet

- Parental Characteristics, Parenting Style, and Behavioral Problems Among Chinese Children With Down Syndrome, Their Siblings and Controls in TaiwanDocument11 pagesParental Characteristics, Parenting Style, and Behavioral Problems Among Chinese Children With Down Syndrome, Their Siblings and Controls in Taiwanrifka yoesoefNo ratings yet

- Child Care and The Development of Young Children (0-2) : February 2011, Rev. EdDocument5 pagesChild Care and The Development of Young Children (0-2) : February 2011, Rev. Edhanifah nurul jNo ratings yet

- 1080 1886 1 SM PDFDocument3 pages1080 1886 1 SM PDFAlverina Putri RiandaNo ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services ReviewDocument11 pagesChildren and Youth Services ReviewNadia Cenat CenutNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Parenting Styles and Depression in AdolescentsDocument12 pagesRelationship Between Parenting Styles and Depression in AdolescentsSantosoNo ratings yet

- Lack of Parental Supervision and Psychosocial Development of Children of School Going Age in Buea Sub DivisionDocument16 pagesLack of Parental Supervision and Psychosocial Development of Children of School Going Age in Buea Sub DivisionEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Clinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment of Communication DisordersFrom EverandClinical Guide to Assessment and Treatment of Communication DisordersNo ratings yet

- Periodontics (PDFDrive)Document329 pagesPeriodontics (PDFDrive)Rosvin FernandezNo ratings yet

- Effects of COVID-19 To Dental Education and Practice in The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesEffects of COVID-19 To Dental Education and Practice in The PhilippinesALongNo ratings yet

- Goa GCET 2014Document79 pagesGoa GCET 2014AnweshaBoseNo ratings yet

- Summer - 2023 Phase - III Time Table Remaining UG - PG and University Courses University Theory Examinations - 190523Document66 pagesSummer - 2023 Phase - III Time Table Remaining UG - PG and University Courses University Theory Examinations - 190523shivaNo ratings yet

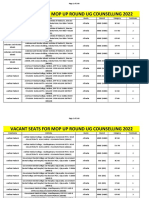

- Vacant Seats For Mop Up Round Ug Counselling 2022Document140 pagesVacant Seats For Mop Up Round Ug Counselling 2022Dnyaneshwar Kawale patilNo ratings yet

- January 28Document48 pagesJanuary 28fijitimescanadaNo ratings yet

- Textbook of Oral Medicine, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology PDFDocument924 pagesTextbook of Oral Medicine, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology PDFEman Azmi Omar50% (2)

- March 4 2011Document48 pagesMarch 4 2011fijitimescanadaNo ratings yet

- PDF Ingle S Endodontics 2 Volume Set 7Th Edition Ilan Rotstein Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Ingle S Endodontics 2 Volume Set 7Th Edition Ilan Rotstein Ebook Full Chaptereugene.alexander316100% (6)

- Advanced Education ProgramsDocument3 pagesAdvanced Education ProgramsDr. AtheerNo ratings yet

- Michigan COVID-19 Safety Grants MASTER Spreadsheet 705751 7Document99 pagesMichigan COVID-19 Safety Grants MASTER Spreadsheet 705751 7Shannon holmesNo ratings yet

- Polyetheretherketone in Implant Prosthodontics: A Scoping ReviewDocument9 pagesPolyetheretherketone in Implant Prosthodontics: A Scoping ReviewNelson BarakatNo ratings yet

- DPMTDocument38 pagesDPMTPunit GauravNo ratings yet

- Wa0002.Document1 pageWa0002.Subina nazrinNo ratings yet

- Prospectus: Adesh UniversityDocument28 pagesProspectus: Adesh UniversityChandrakant KhadkeNo ratings yet

- Fenestration Dehiscence PDFDocument4 pagesFenestration Dehiscence PDFSina Marduk100% (1)

- MX Sinus SurgeryDocument17 pagesMX Sinus SurgeryDrRudra ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Bond FailureDocument3 pagesBond Failuredentist97No ratings yet

- Commencement Dec2022rvs - FinalDocument49 pagesCommencement Dec2022rvs - FinalSteiner MarisNo ratings yet

- JIndianAssocPublicHealthDent164274-6341254 173652 PDFDocument3 pagesJIndianAssocPublicHealthDent164274-6341254 173652 PDFgurpreet singhNo ratings yet

- Endodontic TherapyDocument243 pagesEndodontic TherapyRadu FuseaNo ratings yet

- P.M.N.M.dental CollegeDocument13 pagesP.M.N.M.dental CollegeRakeshKumar1987No ratings yet

- PMDC 2Document2 pagesPMDC 2Maheen Iqbal0% (1)

- COVID 19 & MUCORMYCOSIS MCQs Part 2 126 Questions With ExplanationsDocument348 pagesCOVID 19 & MUCORMYCOSIS MCQs Part 2 126 Questions With ExplanationsZara VaraNo ratings yet

- Spring 2012Document32 pagesSpring 2012Roza NafilahNo ratings yet

- Muhimbili University of Health and Allied SciencesDocument151 pagesMuhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciencesdylan OfficialNo ratings yet