Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Janberidze Et Al 2015

Janberidze Et Al 2015

Uploaded by

Elene JanberidzeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Janberidze Et Al 2015

Janberidze Et Al 2015

Uploaded by

Elene JanberidzeCopyright:

Available Formats

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.

com

Research

Depressive symptoms in the last

days of life of patients with cancer:

a nationwide retrospective

mortality study

Elene Janberidze,1,2 Sandra Martins Pereira,3 Marianne Jensen Hjermstad,1,4

Anne Kari Knudsen,1,2 Stein Kaasa,1,2 Agnes van der Heide,5

Bregje Onwuteaka-Philipsen,3 on behalf of EURO IMPACT

For numbered affiliations see ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION

end of article.

Objectives Depressive symptoms are common Prevalence rates of depression and anxiety

Correspondence to in patients with cancer and tend to increase as in patients with long-term physical disor-

Dr Elene Janberidze, European death approaches. The study aims were to ders are about 25–30%.1 Also, in patients

Palliative Care Research Centre, examine the prevalence of depressive symptoms with advanced cancer, depressive symp-

Department of Cancer Research

and Molecular Medicine, Faculty

in patients with cancer in their final 24 h, and toms are commonly experienced.2 The

of Medicine, Norwegian their association with other symptoms, reported prevalence rates in this patient

University of Science and sociodemographic and care characteristics. population vary considerably from 2% to

Technology (NTNU), Methods A stratified sample of deaths was 56% depending on the assessment method

Kunnskapssenteret 4. etg.,

St. Olavs Hospital, drawn by Statistics Netherlands. Questionnaires used.3 Self-reporting of subjective symp-

Trondheim N-7006 Norway; on patient and care characteristics were sent to toms in patients with cancer is generally

elene.janberidze@ntnu.no the physicians (N=6860) who signed the death considered as the ‘gold standard’ of assess-

certificates (response rate 77.8%). Adult patients ment.4 However, in the last days of life,

Received 16 May 2014

Revised 13 October 2014 with cancer with non-sudden death were compliance with self-report measures vary

Accepted 19 December 2014 included (n=1363). Symptoms during the final dramatically5 since many patients may

24 h of life were assessed on a 1–5 scale and have multiple concurrent symptoms and a

categorised as 1=no, 2–3=mild/moderate and high symptom burden,6 for example, con-

4–5=severe/very severe. fusion, communication difficulties, and/or

Results Depressive symptoms were registered in physical and cognitive disability.7 Thus, in

37.6% of the patients. Patients aged 80 years or this phase, ratings of patients’ symptoms

more had a reduced risk of having mild/ by healthcare providers and/or their next

moderate depressive symptoms compared with of kin may be a feasible solution. Proxy

those aged 17–65 years (OR 0.70; 95% CI 0.50 ratings of this kind are reported to be rea-

to 0.99). Elderly care physicians were more likely sonably adequate.8 The benefits of the

to assess patients with severe/very severe proxy ratings may outweigh the limitations

depressive symptoms than patients with no when studying groups that would other-

depressive symptoms (OR 4.18; 95% CI 1.48 to wise be excluded from studies.8–10

11.76). Involvement of pain specialists/palliative Different sociodemographic character-

care consultants and psychiatrists/psychologists istics and symptoms have been identified as

was associated with more ratings of severe/very being associated with depression in popu-

severe depressive symptoms. Fatigue and lations with cancer. Those characteristics

confusion were significantly associated with include younger age,11 female gender,12

mild/moderate depressive symptoms and anxiety marital status13 and certain cancer diagno-

with severe/very severe symptoms. ses such as breast14 and pancreatic

To cite: Janberidze E, Conclusions More than one-third of the cancer.15 Most patients with cancer have

Pereira SM, Hjermstad MJ, patients were categorised with depressive several symptoms during their disease tra-

et al. BMJ Supportive &

symptoms during the last 24 h of life. jectory with fatigue, pain and dyspnoea

Palliative Care Published Online

First: [please include Day We recommend greater awareness of being among the most common,6 leading

Month Year] doi:10.1136/ depression earlier in the disease trajectory to to an impaired quality of life.16 Many of

bmjspcare-2014-000722 improve care. these somatic symptoms may overlap with

Janberidze E, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000722 1

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research

the nine symptoms included in the diagnostic criteria of patient’s death (n=848), (2) the patient died suddenly

depression in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of or unexpectedly according to the physician (n=635),

Mental Disorders (DSM) V,17 for example, fatigue.18 (3) the patient was younger than 17 years old

The present study makes use of survey data from a (n=121), (4) the cause of death was other than cancer

large nationwide retrospective death certificate study (n=1508) and if (5) the patient was unconscious in

from the Netherlands conducted in 2005,19 which the last days of life (n=709). This resulted in a sample

examines different aspects of end-of-life practice. Data of 1521 patients, with missing information on depres-

on depression and other symptoms prior to death sive symptoms in 10.4% (n=158). Thus, the final

were registered by the attending physicians retrospect- study population consisted of 1363 cases.

ively, and were used to address the following research

questions: Measures

1. What was the prevalence of depressive symptoms in A four-page questionnaire was completed 1–2 months

patients with cancer in the final 24 h of life based on after the patient’s death. It included information on

reports from the attending physician? care received by the patient, such as the medical spe-

2. Were there any associations between depressive symp- cialty of the attending physician, and whether other

toms as reported by physicians and the patients’ healthcare providers were involved in the care of the

sociodemographic characteristics and characteristics patient in the last month of life (eg, pain specialist).

of care? The prevalence and intensity of the following symp-

3. Were there any associations between depressive symp- toms were rated by the physician who signed the

toms and the following common symptoms: pain, vomit- death certificate: depression, pain, vomiting, fatigue,

ing, fatigue, dyspnoea, confusion and anxiety? dyspnoea, confusion and anxiety in the final 24 h

before death. Symptom intensity was registered on a

METHODS rating scale ranging from 1=no symptoms to 5=very

Study design severe symptoms.

A nationwide retrospective death certificate study was Sociodemographic characteristics (eg, gender, age at

performed in 2005 analogous to three previously con- death, marital status, place of death) and underlying

ducted studies.20–22 A stratified sample of deaths was cause of death were captured from the death certificates,

drawn by Statistics Netherlands (http://www.cbs.nl) which were linked to the questionnaires received.

which receives death certificates of all deaths in the

country. Depending on the cause of death registered on Statistical analysis

the death certificate, the death was assigned to one of In this study, the scale used for rating symptom inten-

five strata (1–5). Patients with instant death (eg, car acci- sity was categorised as 1=no, 2=mild, 3=moderate,

dent) were assigned to stratum 1. Cases from stratum 1 4=severe and 5=very severe, and further recoded

did not receive any assistance from a physician prior to into three groups: 1=no, 2–3=mild/moderate and

death. Consequently, questionnaires were not sent, but 4–5=severe/very severe. Sociodemographic character-

the cases were retained in the sample. All other deaths istics, care characteristics and patients’ physician-

were assigned to strata 2–5, with each stratum having a reported symptoms were chosen as independent

higher likelihood of having a medical end-of-life deci- variables based on the existing literature.6 11–13

sion preceding death.19 The final sample contained half Intensity of depressive symptoms was defined as the

of the cases in stratum 5, 25% of the cases in stratum 4, dependent variable divided into three categories: no

12.5% of those in stratum 3, 8.3% of those in stratum (reference), mild/moderate and severe/very severe.

2, and all cases in stratum 1 corresponding with the pre- The following analyses were performed:

vious publication.19 Patients with cancer registered as 1. The association between independent and dependent

the cause of death were included in stratum 4. variables was analysed using the χ2 test ( p<0.05).

For all sampled deaths, a questionnaire was mailed Weighted percentages were applied to adjust for differ-

to the physicians who had signed the death certificate, ences in the percentages of deaths sampled from each of

with a letter including the name and date of birth of the five strata, and differences in response rates in rela-

the diseased person. This information allowed physi- tion to the age, sex, marital status, region of residence

cians to identify the patient and to retrieve relevant and cause of death of the patients. After adjustment, the

information from the patient’s medical record. percentages were extrapolated to cover a 12-month

According to Dutch legislation, there was no need for period to reflect all deaths in the Netherlands in 2005.

ethical committee approval.19 As a result of this weighting procedure, the percentages

presented cannot be derived from the absolute numbers

Population presented.

Of 6860 questionnaires mailed, 5342 were returned, 2. Multinomial logistic regression analyses were used to

giving a response rate of 77.8%. For the present ana- further study the association between independent and

lysis, cases were excluded if (1) the physicians had dependent variables. No weighting procedure was

their very first contact with the patient after the applied. In the first step of this analysis, all independent

2 Janberidze E, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000722

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research

variables that showed a significant association with the patients were married. Forty-eight per cent died at

dependent variable were entered into the model, except home, 24% in hospital, 15% in nursing homes and

for place of death. This variable was left out from the 6% in residential homes. General practitioners

analysis because of its high correlation with the medical attended to 60% of the patients before or at the time

specialty of the attending physician. Using a backwards of death (table 1). The overall prevalence of depres-

stepwise approach, variables were excluded until the last sive symptoms in the last 24 h of life was 37.6%,

step of the analysis in which only variables with a statis- including 31.8% with mild/moderate symptoms and

tical significance ( p<0.05) remained in the model. 5.8% with severe/very severe depressive symptoms

Results are presented in terms of p values and ORs (figure 1).

along with 95% CIs. All of the statistical analyses

were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics V.19.0 for Sociodemographic and care characteristics

Windows (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, Table 1 shows the association between the presence of

USA). depressive symptoms (no, mild/moderate, severe/very

severe) and patients’ sociodemographic and care

RESULTS characteristics. There were more women in the group

Patient characteristics and prevalence of depressive with severe/very severe depressive symptoms (53%)

symptoms than in the other two groups (44% with no symptoms

Seventy-two per cent of the patients were 65 years or and 40% with mild/moderate symptoms). A larger

above, 43% were female and more than 50% of the proportion of patients with no depressive symptoms

Table 1 Association between depressive symptoms and sociodemographic and care characteristics in patients with cancer (n=1363)

Presence and absence of depressive symptoms in patients with cancer at the end of life

Mild/moderate Severe/very Total

No (n=855) (n=434) severe (n=74) (n=1363)

Variable N (%)* N (%)* N (%)* N (%)* p Value

Sociodemographic characteristics

Gender

Male 477 (56) 263 (60) 35 (47) 775 (57) <0.001

Female 378 (44) 171 (40) 39 (53) 588 (43)

Age, years

17–64 260 (27) 147 (31) 22 (27) 429 (28) <0.001

65–79 348 (43) 201 (47) 35 (48) 584 (44)

80 and older 247 (30) 86 (22) 17 (25) 350 (28)

Marital status

Married 483 (57) 263 (61) 44 (61) 790 (59) <0.001

Not married 372 (43) 171 (39) 30 (39) 573 (41)

Care characteristics

Place of death

Hospital 159 (22) 98 (26) 19 (30) 276 (24) <0.001

Nursing home 136 (17) 55 (13) 5 (7) 196 (15)

Residential home 56 (7) 18 (4) 7 (10) 81 (6)

Home 438 (47) 236 (51) 39 (48) 713 (48)

Other setting 66 (7) 27 (6) 4 (5) 97 (7)

Medical specialty of attending physician†‡

General practitioner 542 (60) 276 (60) 50 (63) 868 (60) <0.001

Clinical specialist 154 (22) 97 (26) 19 (30) 270 (24)

Elderly care physician 146 (18) 60 (14) 5 (7) 211 (16)

Which caregivers were involved in the care of the patient during the last month before death (beside yourself)?

Pain specialist/palliative care consultant 105 (11) 66 (14) 20 (27) 191 (13) <0.001

Psychiatrist/psychologist 16 (2) 12 (3) 8 (11) 36 (3) <0.001

Spiritual caregiver 128 (15) 62 (15) 15 (22) 205 (15) <0.001

Volunteer 131 (15) 76 (17) 11 (15) 218 (15) <0.001

Data present the absolute number of patients; however, the percentages are weighted.

*Percentages presented are weighted to adjust for the sampling fraction, non-response and random sampling deviation, to make them representative of all

deaths in 2005.

†The attending physicians were general practitioners, clinical specialists or elderly care physicians.

‡The sample included 14 physicians with an unknown specialty.

Janberidze E, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000722 3

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research

moderate depressive symptoms, and 8% of patients

without depression had severe/very severe anxiety.

Multinomial logistic regression analyses

Patients who were 80 years and older had a reduced

risk of having mild/moderate depressive symptoms

compared with those who were 17–65 years (OR 0.70,

95% CI 0.50 to 0.99) (table 3). Elderly care physicians

were more likely to assess patients with severe/very

severe depressive symptoms than patients with no

depressive symptoms (OR 4.18; 95% CI 1.48 to

11.76). Pain specialists or palliative care consultants

(OR 2.07; 95% CI 1.10 to 3.88) and especially psy-

chologists or psychiatrists (OR 4.83; 95% CI 1.59 to

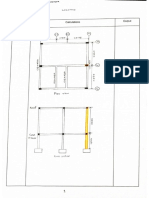

Figure 1 Bar chart presenting physician-reported depressive

symptoms in patients with cancer during the last 24 h of life.

14.70) were more likely to be involved in the care of

Percentages presented are weighted to adjust for the sampling the patients with severe/very severe depressive symp-

fraction, non-response and random sampling deviation, to make toms than in the care of patients with no depressive

them representative of all deaths in 2005. symptoms. Three symptoms fatigue (OR 1.83; 95% CI

1.36 to 2.46), anxiety (OR 1.92; 95% CI 1.33 to 2.77)

and confusion (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.05 to 2.11)

were 80 years or older compared with patients in the occurred more frequently in patients with mild/moder-

other two groups (30% vs 22% with mild/moderate ate depressive symptoms compared with patients with

symptoms and 25% with severe/very severe depressive no depressive symptoms. In addition, anxiety was asso-

symptoms). There was an uneven distribution of ciated with reporting severe/very severe depressive

patients categorised with severe/very severe, mild/ symptoms (OR 15.06; 95% CI 8.45 to 26.84).

moderate or no depression across places of death

( p<0.001). Among the 713 patients who died at DISCUSSION

home, 48% had severe/very severe depressive symp- This study applied data from a large population-based

toms; however, patients who died in nursing homes study conducted in 2005 in the Netherlands to

were less often categorised as having severe/very examine depressive symptoms in patients with cancer

severe depressive symptoms than patients with mild/ at the end of life. Attending physicians reported

moderate or no depressive symptoms (7% vs 13% depressive symptoms as being present in 37.6% of

and 17%). Patients with severe/very severe depressive patients, although only 5.8% were categorised as

symptoms were less frequently attended to by elderly severe/very severe. Patients who were 80 years and

care physicians than patients with mild/moderate or older had a reduced risk of having mild/moderate

no depressive symptoms (7% vs 14% and 18%). depressive symptoms compared with those aged 17–

Patients with severe/very severe depressive symptoms 65 years. Involvement of specialists in the care of the

more often had additional professionals involved in patient during the last month before death was asso-

their care than patients with mild/moderate or no ciated with severe/very severe depressive symptoms.

depressive symptoms: pain specialists or palliative care Fatigue and confusion occurred more frequently in

consultants (27% vs 14% and 11%), psychiatrists or patients categorised with mild/moderate depressive

psychologists (11% vs 3% and 2%) and spiritual care- symptoms, while anxiety was the only symptom asso-

givers (22% vs 15% and 15%). ciated with both mild/moderate and severe/very severe

depressive symptoms.

The presented results should be interpreted with

Other subjective symptoms caution. First, we used physicians as proxies for report-

Pain was reported as being mild/moderate in 46% of ing symptoms in patients with cancer, which may have

the patients, against severe/very severe in 33%. led to an underestimation of symptom severity or fre-

Anxiety was mild/moderate in 47% and severe/very quency, as physicians in general are likely to underesti-

severe in 14%, while 73% reported severe/very severe mate the presence of symptoms when compared with

fatigue (table 2). Physician-reported subjective symp- patient self-report.23–26 However, even if patients’ self-

toms differed across the three categories of intensity report of subjective symptoms is considered to be the

of depressive symptoms. More severe/very severe gold standard in palliative care,4 the use of proxy

symptoms were observed in patients with severe/very ratings may allow for inclusion of patients who would

severe depressive symptoms as compared with patients otherwise not be able to participate due to, for

with mild/moderate or no depressive symptoms; for example, cognitive or physical impairment. Second,

example, 63% of the patients with severe/very severe the study was retrospective and the time interval

depression symptoms, 18% of patients with mild/ between death and mailing the questionnaire varied

4 Janberidze E, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000722

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research

Table 2 Association between depressive symptoms and other symptoms in patients during the last 24 h before death (n=1363)

Presence and absence of depressive symptoms in patients with cancer at the end of life

Mild/moderate Severe/very Total

No (n=855) (n=434) severe (n=74) (n=1363)

Symptoms (missing) N (%)* N (%)* N (%)* N (%)* p Value

Pain (12%)

No pain 199 (25) 66 (16) 9 (14) 274 (21) <0.001

Mild/moderate pain 388 (45) 29 (40) 627 (46)

Severe/very severe pain 265 (30) 155 (35) 35 (46) 455 (33)

Vomiting (13%)

No vomiting 629 (76) 64 (64) 38 (52) 931 (71) <0.001

Mild/moderate vomiting 147 (16) 119 (27) 21 (31) 287 (20)

Severe/very severe vomiting 73 (8) 21 (9) 12 (17) 127 (9)

Fatigue (12%)

No fatigue 65 (9) 6 (2) 2 (3) 73 (6) <0.001

Mild/moderate fatigue 189 (24) 70 (17) 11 (16) 270 (21)

Severe/very severe fatigue 590 (67) 354 (81) 61 (81) 1005 (73)

Dyspnoea (12%)

No dyspnoea 325 (38) 104 (23) 16 (20) 445 (32) <0.001

Mild/moderate dyspnoea 266 (31) 188 (43) 28 (38) 482 (35)

Severe/very severe dyspnoea 259 (31) 139 (34) 30 (42) 428(33)

Confusion (12%)

No confusion 510 (58) 122 (26) 14 (17) 646 (46) <0.001

Mild/moderate confusion 248 (30) 233 (55) 36 (51) 517 (39)

Severe/very severe confusion 94 (12) 76 (19) 23 (32) 193 (15)

Anxiety (11%)

No anxiety 470 (54) 73 (16) 2 (2) 545 (39) <0.001

Mild/moderate anxiety 311 (38) 283 (66) 26 (35) 620 (47)

Severe/very severe anxiety 72 (8) 75 (18) 46 (63) 193 (14)

Data present the absolute number of patients; however, the percentages are weighted.

*Percentages presented are weighted to adjust for the sampling fraction, non-response and random sampling deviation, to make them representative of all

deaths in 2005.

between 1 and 2 months, which may have caused a therapeutic effects may be questionable.27 28 Detailed

recall error. Missing data on depressive symptoms registration of interventions for depressive symptoms,

(10.4%) probably illustrate some difficulties that physi- duration of receiving antidepressant medication, infor-

cians may have had in assessing depression or recalling mation of when depression was first identified and dur-

information and could engender bias. However, owing ation of depressive symptoms would have been given

to the large sample size, there are data on depressive important information about depression and treatment

symptoms in 1363 patients, which increases the reli- outcomes; however, this was beyond the scope of the

ability. Furthermore, the major group of attending phy- death certificate study. No control group was included

sicians included general practitioners (60%) who had as the primary aim of the study was to describe the

been the patients’ family doctors for several years. existing practice of end-of-life care in the Netherlands.

Thus, they did not only sign the death certificates or The major strength of this study is related to the

attend patients during the last days of life but were also sample size including 1363 patients with cancer at the

familiar with the patient and relatives. Third, no stan- end of life. The study included information on

dardised measure with validated cut-off scores was patients extracted from the death certificates in the

used for reporting, and the physicians were not asked Netherlands, and involved different care settings

if they assessed depression with any formal tools in the across the country, making the results representative

last 24 h before death. We also lack information on the of the entire cancer population in the Netherlands.

use of medication such as antidepressants, other psy- Furthermore, the response to the questionnaire was

chotropic drugs and opioids which may have led to high (77.8%).

fatigue, confusion or development of other distressing

symptoms at the end of life. However, from other Prevalence rates of depressive symptoms

studies, we know that antidepressants are often pre- In general, a comparison of prevalence rates is chal-

scribed close to death and in fact so late that the lenging partly due to the different study designs,

Janberidze E, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000722 5

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research

Table 3 Variables associated with depressive symptoms in multinomial logistic regression analyses (N=1363)

Presence and absence of depressive symptoms in patients with cancer at the end of life

Mild/moderate (n=434) Severe/very severe (n=74)

Variable OR (95% CI) p Value OR (95% CI) p Value

Age

17–64 1.00 1.00

65–79 1.09 (0.83 to 1.44) 0.530 0.55 (0.84 to 2.89) 0.162

80 and older 0.70 (0.50 to 0.99) 0.043 1.52 (0.71 to 3.22) 0.277

Medical specialty of attending physician*

General practitioner 1.00 1.00

Clinical specialist 1.30 (0.96 to 1.76) 0.095 1.16 (0.62 to 2.18) 0.641

Elderly care physician 1.13 (0.78 to 1.62) 0.517 4.18 (1.48 to 11.76) 0.007

Which caregivers were involved in the care of the patient during the last month before death (beside yourself)?

Pain specialist/palliative care consultant

No 1.00 1.00

Yes 1.16 (0.82 to 1.64) 0.412 2.07 (1.10 to 3.88) 0.023

Psychiatrist/psychologist

No 1.00 1.00

Yes 1.37 (0.59 to 3.21) 0.467 4.83 (1.59 to 14.70) 0.006

Symptoms during the last 24 h before death

Fatigue

No 1.00 1.00

Yes 1.83 (1.36 to 2.46) <0.001 1.46 (0.73 to 2.91) 0.282

Anxiety

No 1.00 1.00

Yes 1.92 (1.33 to 2.77) <0.001 15.06 (8.45 to 26.84) <0.001

Confusion

No 1.00 1.00

Yes 1.49 (1.05 to 2.11) 0.025 1.48 (0.79 to 2.79) 0.223

No weighting procedure was conducted during multinomial logistic regression analysis. Bold numbers represent ORs and 95% CIs showing statistically

significant difference (ORs differs significantly from 1.00) between the categories of mild/moderate or severe/very severe depressive symptoms compared

with the group with no depressive symptoms (reference category).

The variables not reaching statistical significance in multinomial logistic regression were: spiritual caregiver involved in the care of the patient for the last

month before death, patients’ marital status, volunteer involved in the care of the patients for the last month before death, physical symptoms such as

pain, vomiting, dyspnoea and patients’ gender.

*The attending physicians were general practitioners, clinical specialists or elderly care physicians.

inclusion of patients with different survival time, and physicians reporting the present data were not specific-

use of different assessment or reporting methods (eg, ally trained to identify depression at the end of life, or

self-report vs diagnostic tools or proxy ratings). A pre- to distinguish this from, for example, fatigue or late

vious study from the Netherlands examined primary stage infirmity. On the other hand, initiation of psycho-

care patients with cancer at a median of 15 weeks logical interventions near the end of life may some-

before death.29 Depressed mood was reported by times be thought to be too late or symptoms could be

general practitioners using a scale from 1 (not regarded as a normal part of the dying process.33

depressed) to 5 (very depressed). According to a

cut-off score of 2, the prevalence rate for depressive Sociodemographic and care characteristics

symptoms was 14%, which corresponds with our Our results regarding age were inconclusive and

results (17%) when using the same threshold. cannot confirm results from other studies showing that

Diagnosing depression is challenging, especially in younger age may be associated with depression.11 The

patients with other somatic illnesses where symptoms association between severe/very severe depressive

such as fatigue can be related to the cancer, its treat- symptoms and elderly care physicians might partly be

ment or interpreted as a sign of depression according explained by the fact that patients in need of specialist

to the DSM-V criteria.17 Unsystematic assessment of care have a higher symptom burden than patients not

symptoms,30 lack of communication skills31 and insuffi- requiring specialist care.34 Furthermore, specialists are

cient training of healthcare providers to recognise expected to have more experience with patients having

depressive symptoms at the end of life could be the complex conditions and may thus identify patients

most important explanations.32 The attending with cancer with depressive symptoms more easily

6 Janberidze E, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000722

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research

than general practitioners would.35 Additional profes- symptom control and quality of life, also at the end of

sional caregivers besides the responsible physician life.42–46 For example, in the well-known study by

involved in the management of patients with cancer in Temel et al,42 patients with non-small cell lung cancer

the last month before death (eg, pain specialist) appear who were randomised to palliative care had signifi-

to facilitate more precise patient identification in need cantly fewer depressive symptoms than those in the

of symptom treatment. Specialists in general may tend standard group.

to systematically assess and be able to diagnose the

patients with complex conditions. However, our data

CONCLUSIONS

showed that additional specialists were involved only

in a minor group of the patient cohort. This study showed that more than one-third of

patients with cancer were rated as having mild/moder-

ate to severe/very severe depressive symptoms by the

Symptoms

Patients with advanced cancer often experience symp- attending physicians during the last 24 h of life.

toms that are coexisting and interdependent, espe- Multiple symptoms, and especially depressive symp-

toms, in patients with cancer at the end of life still call

cially when facing the end of life.6 36 37 Studies show

an association between uncontrolled physical symp- for special attention. Improved knowledge among

toms, such as pain, and depression,38 39 but the caus- healthcare providers about assessment, classification

and treatment of depression and depressive symptoms

ality of this relationship is unclear.38 In this study, the

patients were reported to have a relatively high in patients with advanced cancer would be important

symptom burden in the last 24 h of life; for example, to optimise cancer patient care throughout the disease

trajectory.

79% of the patients had pain (46% reported as mod-

erate and 33% as severe). In the univariate analyses,

an association between pain and depressive symptoms Author affiliations

1

European Palliative Care Research Centre (PRC),

was observed. However, unexpectedly, no such associ-

ation was found in the multinomial logistic regression. Department of Cancer Research and Molecular

In this study, there was an association between Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Norwegian University

of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim,

involvement of pain specialists in patient treatment

and severe depressive symptoms. This may indicate Norway

2

that patients with depressive symptoms have a Department of Oncology, St. Olavs Hospital,

Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim, Norway

complex symptomatology and may need a multidiscip- 3

linary palliative care approach. Data on the actual Department of Public and Occupational Health, VU

pain treatment were not available. University Medical Center, and EMGO+ Institute

for Health and Care Research, VUmc Expertise

Fatigue is known to be more frequent and severe

among depressed than non-depressed patients.40 Center for Palliative Care, Amsterdam, Netherlands

4

Diagnosis of depression according to the DSM-V cri- Regional Centre for Excellence in Palliative Care,

South Eastern Norway, Oslo University Hospital,

teria17 is established if five of nine criteria symptoms are

present, with fatigue or loss of energy being one of Oslo, Norway

5

these. Our data showed that 73% of the patients were Department of Public Health, Erasmus Medical

Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

experiencing severe/very severe fatigue in the final 24 h

before death. Healthcare providers may have inter- Acknowledgements The authors thank the following EURO

preted fatigue as part of the dying process, a sign of IMPACT collaborators for their contribution.

depression, or something that may have contributed to Collaborators This article is part of the European Intersectorial

the development of depression in patients with both and Multidisciplinary Palliative Care Research Training (EURO

symptoms. In addition, anxiety was the only variable IMPACT). EURO IMPACT is funded by the European Union

Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013, under grant

associated with both mild/moderate and severe/very agreement n° [264697]). EURO IMPACT aims to develop a

severe depressive symptoms. This could be explained by multidisciplinary, multi-professional and inter-sectorial

the interdependent nature of those two conditions.37 educational and research training framework for palliative care

research in Europe. EURO IMPACT is coordinated by Professor

The seemingly high prevalence of symptoms in this Luc Deliens, Professor Lieve Van den Block, Zeger De Groote,

study, and of depressive symptoms in particular, Joachim Cohen and Koen Pardon of the End-of-Life Care

points to a need to increase awareness of thorough Research Group, Ghent University & Vrije Universiteit Brussel,

Brussels, Belgium. Other partners are: Anneke Francke, Luc

symptom assessment throughout the cancer disease Deliens and Roeline Pasman, VU University Medical Center,

trajectory. According to the WHO’s revised definition EMGO Institute for health and care research, Amsterdam, The

of palliative care,41early integration of palliative care Netherlands; Richard Harding and Irene J Higginson, King’s

College London, Cicely Saunders Institute, London, and Cicely

in the management of patients with cancer is recom- Saunders International, London; and Sarah Brearley and Sheila

mended.42 Introducing palliative care early to the Payne, International Observatory on End-of-Life Care,

patients with its systematic approach to symptom Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK; Augusto Caraceni, EAPC

Research Network, Trondheim, Norway; and Fondazione

assessment increases the awareness and attention to IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy, and Guido

symptoms at an earlier stage and results in better Miccinesi, Cancer Research and Prevention Institute, Florence,

Janberidze E, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000722 7

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research

Italy; Sophie Pautex, EUGMS European Union Geriatric 13 Schlegel RJ, Manning MA, Molix LA, et al. Predictors of

Medicine Society, Geneva, Switzerland; Karen Linden, Springer depressive symptoms among breast cancer patients

Science and Business Media, Houten, The Netherlands. during the first year post diagnosis. Psychol Health

Contributors BO-P and AVDH were responsible for the study 2012;27:277–93.

concept and devised the questionnaire. Statistics Netherlands 14 Zabora J, Brintzenhofeszoc K, Curbow B, et al. The prevalence

made the stratification analysis. EJ led the statistical analysis and

writing of the paper; all co-authors commented on the draft of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology

and agree on the final content. 2001;10:19–28.

Funding This study was funded by the Netherlands 15 Mayr M, Schmid RM. Pancreatic cancer and depression: myth

Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), and truth. BMC Cancer 2010;10:569.

grant number 1151.0001, and the VU University Medical 16 Zoega S, Fridriksdottir N, Sigurdardottir V, et al. Pain and

Center, EMGO Institute for Health and Care Research, other symptoms and their relationship to quality of life in

Department of General Practice & Elderly Care medicine, and

cancer patients on opioids. Qual Life Res 2013;22:1273–80.

the Department of Public and Occupational Health,

Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 17 American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 task force. Diagnostic

and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th edn.

Competing interests None.

Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally

18 Wang XS. Pathophysiology of cancer-related fatigue. Clin J

peer reviewed.

Oncol Nurs 2008;12(5 Suppl):11–20.

Data sharing statement EJ, BOP and AVDH have access to the

19 van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Rurup ML, et al.

full data set.

End-of-life practices in the Netherlands under the Euthanasia

Act. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1957–65.

20 Van Der Maas PJ, Van Delden JJ, Pijnenborg L, et al.

REFERENCES Euthanasia and other medical decisions concerning the end of

1 Cimpean D, Drake RE. Treating co-morbid chronic medical life. Lancet 1991;338:669–74.

conditions and anxiety/depression. Epidemiol Psychiatric Sci 21 Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Heide A, Koper D, et al.

2011;20:141–50. Euthanasia and other end-of-life decisions in the Netherlands

2 Hotopf M, Chidgey J, Addington-Hall J, et al. Depression in in 1990, 1995, and 2001. Lancet 2003;362:395–9.

advanced disease: a systematic review part 1. Prevalence and 22 van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G, Haverkate I, et al.

case finding. Palliat Med 2002;16:81–97. Euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide, and other medical

3 Janberidze E, Hjermstad MJ, Haugen DF, et al. How are practices involving the end of life in the Netherlands,

patient populations characterized in studies investigating 1990–1995. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1699–705.

depression in advanced cancer? Results from a systematic 23 Xiao C, Polomano R, Bruner DW. Comparison between

literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;48:678–98. patient-reported and clinician-observed symptoms in oncology.

4 Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Sprangers MA, et al. Comparison Cancer Nurs 2013;36:E1–16.

of patient and proxy EORTC QLQ-C30 ratings in assessing the 24 Kutner JS, Kassner CT, Nowels DE. Symptom burden at the

quality of life of cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol end of life: hospice providers’ perceptions. J Pain Symptom

1998;51:617–31. Manage 2001;21:473–80.

5 Hui D, Glitza I, Chisholm G, et al. Attrition rates, reasons, and 25 Stromgren AS, Groenvold M, Pedersen L, et al. Does the

predictive factors in supportive care and palliative oncology medical record cover the symptoms experienced by cancer

clinical trials. Cancer 2013;119:1098–105. patients receiving palliative care? A comparison of the record

6 Laugsand EA, Kaasa S, de Conno F, et al. Intensity and and patient self-rating. J Pain Symptom Manage

treatment of symptoms in 3,030 palliative care patients: 2001;21:189–96.

a cross-sectional survey of the EAPC Research Network. J 26 Laugsand EA, Sprangers MA, Bjordal K, et al. Health care

Opioid Manag 2009;5:11–21. providers underestimate symptom intensities of cancer patients:

7 Kurita GP, Sjogren P, Ekholm O, et al. Prevalence and a multicenter European study. Health Qual Life Outcomes

predictors of cognitive dysfunction in opioid-treated patients 2010;8:104.

with cancer: a multinational study. J Clin Oncol 27 Ng CG, Boks MP, Smeets HM, et al. Prescription patterns for

2011;29:1297–303. psychotropic drugs in cancer patients; a large population study

8 Sneeuw KC, Sprangers MA, Aaronson NK. The role of health in the Netherlands. Psychooncology 2013;22:762–7.

care providers and significant others in evaluating the quality 28 Shimizu K, Akechi T, Shimamoto M, et al. Can psychiatric

of life of patients with chronic disease. J Clin Epidemiol intervention improve major depression in very near end-of-life

2002;55:1130–43. cancer patients? Palliat Support Care 2007;5:3–9.

9 Klepstad P, Hjermstad MJ. Are all patients that count included 29 Ruijs CD, Kerkhof AJ, van der Wal G, et al. Depression and

in palliative care studies? BMJ Support Palliat Care explicit requests for euthanasia in end-of-life cancer patients in

2013;3:292–3. primary care in the Netherlands: a longitudinal, prospective

10 Stone PC, Gwilliam B, Keeley V, et al. Factors affecting study. Fam Pract 2011;28:393–9.

recruitment to an observational multicentre palliative care 30 Mitchell AJ. New developments in the detection and treatment

study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:318–23. of depression in cancer settings. Prog Neurol Psychiatry

11 Lo C, Lin J, Gagliese L, et al. Age and depression in patients 2011;15:12–20.

with metastatic cancer: the protective effects of attachment 31 Noorani NH, Montagnini M. Recognizing depression in

security and spiritual wellbeing. Ageing Soc 2010;30:325–36. palliative care patients. J Palliat Med 2007;10:458–64.

12 Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, et al. Emotional distress in 32 Mellor D, McCabe MP, Davison TE, et al. Barriers to the

cancer patients: the Edinburgh Cancer Centre symptom study. detection and management of depression by palliative care

Br J Cancer 2007;96:868–74. professional carers among their patients: perspectives from

8 Janberidze E, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000722

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Research

professional carers and patients’ family members. Am J Hosp of pain severity and pain interference. Cancer Nurs

Palliat Care 2013;30:12–20. 2006;29:400–5.

33 Periyakoil VS, Hallenbeck J. Identifying and managing 40 Kroenke K, Zhong X, Theobald D, et al. Somatic symptoms in

preparatory grief and depression at the end of life. Am Fam patients with cancer experiencing pain or depression:

Physician 2002;65:883–90. prevalence, disability, and health care use. Arch Intern Med

34 Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care 2010;170:1686–94.

—creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 41 World Health Organization. National cancer control

2013;368:1173–5. programmes: Policies and managerial guidelines. Secondary

35 Koopmans RT, Lavrijsen JC, Hoek JF, et al. Dutch elderly care National cancer control programmes: policies and managerial

physician: a new generation of nursing home physician guidelines. 2002. http://www.who.int/cancer/publications/

specialists. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1807–9. nccp2002/en/index.html

36 Kroenke K, Theobald D, Wu J, et al. The association of 42 Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care

depression and pain with health-related quality of life, for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl

disability, and health care use in cancer patients. J Pain J Med 2010;363:733–42.

Symptom Manage 2010;40:327–41. 43 Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early

37 O’Connor M, White K, Kristjanson LJ, et al. The prevalence palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-

of anxiety and depression in palliative care patients with cancer randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721–30.

in Western Australia and New South Wales. Med J Aust 44 Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and

2010;193(5 Suppl):S44–7. setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care

38 Laird BJ, Boyd AC, Colvin LA, et al. Are cancer pain and in cancer patients. Cancer 2014;120:1743–9.

depression interdependent? A systematic review. 45 Barton MK. Early outpatient referral to palliative care services

Psychooncology 2009;18:459–64. improves end-of-life care. CA Cancer J Clin 2014;64:223–4.

39 Mystakidou K, Tsilika E, Parpa E, et al. Psychological distress 46 Saarto T. Palliative care and oncology: the case for early

of patients with advanced cancer: influence and contribution integration. EJPC 2014;21:109.

Janberidze E, et al. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care 2015;0:1–9. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000722 9

Downloaded from http://spcare.bmj.com/ on February 28, 2015 - Published by group.bmj.com

Depressive symptoms in the last days of life

of patients with cancer: a nationwide

retrospective mortality study

Elene Janberidze, Sandra Martins Pereira, Marianne Jensen Hjermstad,

Anne Kari Knudsen, Stein Kaasa, Agnes van der Heide and Bregje

Onwuteaka-Philipsen

BMJ Support Palliat Care published online February 9, 2015

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://spcare.bmj.com/content/early/2015/02/09/bmjspcare-2014-0007

22

These include:

References This article cites 43 articles, 6 of which you can access for free at:

http://spcare.bmj.com/content/early/2015/02/09/bmjspcare-2014-0007

22#BIBL

Email alerting Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the

service box at the top right corner of the online article.

Notes

To request permissions go to:

http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions

To order reprints go to:

http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform

To subscribe to BMJ go to:

http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/

You might also like

- Mass and Energy Balance-122Document75 pagesMass and Energy Balance-122manish sengar100% (2)

- 2019 Education Council Member GuideDocument122 pages2019 Education Council Member GuidemariposanycNo ratings yet

- Graves 2007Document10 pagesGraves 2007Christine HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Mitchell Et All 2011 Prevalence Depression Anxiety Oncoligical HaematologicalDocument15 pagesMitchell Et All 2011 Prevalence Depression Anxiety Oncoligical HaematologicalGuillermoNo ratings yet

- Komorbid 1Document15 pagesKomorbid 1ErioRakiharaNo ratings yet

- Original Paper: Factors That Impact Caregivers of Patients With SchizophreniaDocument10 pagesOriginal Paper: Factors That Impact Caregivers of Patients With SchizophreniaMichaelus1No ratings yet

- Depression in Cancer Patients: Pathogenesis, Implications and Treatment (Review)Document6 pagesDepression in Cancer Patients: Pathogenesis, Implications and Treatment (Review)Fira KhasanahNo ratings yet

- 10 1002@onco 13528Document13 pages10 1002@onco 13528cheatingw995No ratings yet

- Geriatric Depression: Stephen C. Cooke and Melissa L. TuckerDocument13 pagesGeriatric Depression: Stephen C. Cooke and Melissa L. TuckerDini indrianyNo ratings yet

- Polsky 2005Document7 pagesPolsky 2005Tatiana FlorianNo ratings yet

- Comorbid Depression in Medical DiseasesDocument22 pagesComorbid Depression in Medical DiseasesArmando Marín FloresNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Depression and Anxiety of Hospitalized Patients With Heart FailureDocument10 pagesFactors Associated With Depression and Anxiety of Hospitalized Patients With Heart FailureineNo ratings yet

- H1P S A C: Sychological Ymptoms in Dvanced AncerDocument11 pagesH1P S A C: Sychological Ymptoms in Dvanced AnceryuliaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Depression Among Patients With Multiple Sclerosis in Erbil CityDocument10 pagesPrevalence of Depression Among Patients With Multiple Sclerosis in Erbil Citysarhang talebaniNo ratings yet

- A Study of Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Patients PDFDocument34 pagesA Study of Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Patients PDFIrdha Nasta KurniaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0749208122000043 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0749208122000043 Maincheatingw995No ratings yet

- Depression and Hopelessness in Patients With Acute LeukemiaDocument11 pagesDepression and Hopelessness in Patients With Acute LeukemiaPedro CampinaNo ratings yet

- 82264-Article Text-197411-1-10-20121015 PDFDocument6 pages82264-Article Text-197411-1-10-20121015 PDFJamesNo ratings yet

- Manejo Depresion 1Document10 pagesManejo Depresion 1Luis HaroNo ratings yet

- Park, 2019 - NEJM - DepressionDocument10 pagesPark, 2019 - NEJM - DepressionFabian WelchNo ratings yet

- Cruz Et AlDocument8 pagesCruz Et Alkang.asep008No ratings yet

- 120-Article Text-616-1-10-20230414Document6 pages120-Article Text-616-1-10-20230414NOOR SYAFAWATI HANUN MOHD SOBRINo ratings yet

- Depression in The Elderly: Clinical PracticeDocument9 pagesDepression in The Elderly: Clinical PracticejpenasotoNo ratings yet

- Articulo 1Document5 pagesArticulo 1lucia acasieteNo ratings yet

- (R) Nyeri DG Kualitas Hidup (Cancer SCR Umum) 0,77Document8 pages(R) Nyeri DG Kualitas Hidup (Cancer SCR Umum) 0,77Vera El Sammah SiagianNo ratings yet

- Oral Oncology: Hoda Badr, Vishal Gupta, Andrew Sikora, Marshall PosnerDocument7 pagesOral Oncology: Hoda Badr, Vishal Gupta, Andrew Sikora, Marshall PosnerpadillaNo ratings yet

- Depression and Anxiety in Multisomatoform DisorderDocument4 pagesDepression and Anxiety in Multisomatoform DisorderAdeyemi OlusolaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Adjustment Disorder in Oncological, Haematological, and Palliative-Care Settings: A Meta-Analysis of 94 Interview-Based StudiesDocument16 pagesPrevalence of Depression, Anxiety, and Adjustment Disorder in Oncological, Haematological, and Palliative-Care Settings: A Meta-Analysis of 94 Interview-Based StudiesClaudia EvelineNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Depression in Elderly PatientsDocument8 pagesDiagnosis of Depression in Elderly PatientsJosé Jair Campos ReisNo ratings yet

- Guided Discontinuation Versus Maintenance Treatment in Remitted Firstepisode Psychosis Relapse Rates and Functional OutcomeDocument2 pagesGuided Discontinuation Versus Maintenance Treatment in Remitted Firstepisode Psychosis Relapse Rates and Functional Outcomewen zhangNo ratings yet

- Depression Among Patients Attending Physiotherapy Clinics in Erbil CityDocument6 pagesDepression Among Patients Attending Physiotherapy Clinics in Erbil Citysarhang talebaniNo ratings yet

- SomatoformDocument8 pagesSomatoformwisnuNo ratings yet

- DNB Vol33 NoSuppl 2 190Document2 pagesDNB Vol33 NoSuppl 2 190Anel BrigićNo ratings yet

- Depresi CKD 2Document4 pagesDepresi CKD 2sufaNo ratings yet

- Unsaved Preview Document 3Document6 pagesUnsaved Preview Document 3NadewdewNo ratings yet

- The Overdiagnosis of Depression in Non-Depressed Patients in Primary CareDocument7 pagesThe Overdiagnosis of Depression in Non-Depressed Patients in Primary Careengr.alinaqvi40No ratings yet

- Long-Term Effects of The Concomitant Use of Memantine With Cholinesterase Inhibition in Alzheimer DiseaseDocument10 pagesLong-Term Effects of The Concomitant Use of Memantine With Cholinesterase Inhibition in Alzheimer DiseaseDewi SariNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence, Detection and Intervention For Depression and Anxiety in OncologyDocument12 pagesThe Prevalence, Detection and Intervention For Depression and Anxiety in OncologyClaudia EvelineNo ratings yet

- P76 Depression AnnIntMed 2007Document16 pagesP76 Depression AnnIntMed 2007Gabriel CampolinaNo ratings yet

- T I C P W - B F C C P: HE Mpact of Aregiving On THE Sychological ELL Eing of Amily Aregivers and Ancer AtientsDocument10 pagesT I C P W - B F C C P: HE Mpact of Aregiving On THE Sychological ELL Eing of Amily Aregivers and Ancer AtientsNurul ShahirahNo ratings yet

- The Side Effects of Sick Leave Are PsychDocument33 pagesThe Side Effects of Sick Leave Are PsychthefrankoneNo ratings yet

- Anxiety and Sleep Disorders in Cancer Patients: Maria Die TrillDocument9 pagesAnxiety and Sleep Disorders in Cancer Patients: Maria Die TrillAmelia KristiantiNo ratings yet

- SAJPsy 25 1382 PDFDocument7 pagesSAJPsy 25 1382 PDFNix SantosNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Cardiology: A B A B B C D B e D F G H G F I B C DDocument6 pagesInternational Journal of Cardiology: A B A B B C D B e D F G H G F I B C DFrederick WeeNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Measurement of Anxiety in Samples.13Document13 pagesPrevalence and Measurement of Anxiety in Samples.13Tirta SusantoNo ratings yet

- Trastorno Depresivo en Edades TempranasDocument15 pagesTrastorno Depresivo en Edades TempranasManuel Dacio Castañeda CabelloNo ratings yet

- Cancer - 2007 - Miovic - Psychiatric Disorders in Advanced CancerDocument12 pagesCancer - 2007 - Miovic - Psychiatric Disorders in Advanced CancerKarla MiraveteNo ratings yet

- Extrapyramidal Symptoms in 10 Years of Long Term Treatment of Schizophrenia: Independent of Psychopathology and OutcomeDocument5 pagesExtrapyramidal Symptoms in 10 Years of Long Term Treatment of Schizophrenia: Independent of Psychopathology and OutcomeSeiska MegaNo ratings yet

- Datadrive WWW Psy Wp-Content Uploads 2021 02 11656 Clinical-Guidance-On-Treatment-Resistant-SchizophreniaDocument9 pagesDatadrive WWW Psy Wp-Content Uploads 2021 02 11656 Clinical-Guidance-On-Treatment-Resistant-SchizophreniaDiana IstrateNo ratings yet

- Sam072g PDFDocument8 pagesSam072g PDFChristian MorenoNo ratings yet

- Cancers: Symptom Clusters in Survivorship and Their Impact On Ability To Work Among Cancer SurvivorsDocument11 pagesCancers: Symptom Clusters in Survivorship and Their Impact On Ability To Work Among Cancer SurvivorsSteve GannabanNo ratings yet

- Ansiedade 04Document9 pagesAnsiedade 04Karina BorgesNo ratings yet

- Severely Affected by Parkinson Disease: The Patient's View and Implications For Palliative CareDocument7 pagesSeverely Affected by Parkinson Disease: The Patient's View and Implications For Palliative CareLorenaNo ratings yet

- Artikel InterDocument6 pagesArtikel InterHafid LuizNo ratings yet

- Delerium MultipleregressionDocument7 pagesDelerium MultipleregressionK. O.No ratings yet

- Predicting Trends in Dyspnea and Fatigue in Heart Failure Patients' OutcomesDocument8 pagesPredicting Trends in Dyspnea and Fatigue in Heart Failure Patients' Outcomesabraham rumayaraNo ratings yet

- PSY53 PATIENT PREFERENCES IN THE TREATMENT OF HEMOPHILIA A - 2019 - Value in HDocument1 pagePSY53 PATIENT PREFERENCES IN THE TREATMENT OF HEMOPHILIA A - 2019 - Value in HMichael John AguilarNo ratings yet

- Parkinsonism and Related DisordersDocument4 pagesParkinsonism and Related DisordersLorenaNo ratings yet

- Estudo. Espectro BipolarDocument9 pagesEstudo. Espectro BipolarGabriel LemosNo ratings yet

- Depression, Alzheimer, Family CaregiversDocument13 pagesDepression, Alzheimer, Family CaregiversCathy Georgiana HNo ratings yet

- Prieto6 Roleofdepression Jco2005Document9 pagesPrieto6 Roleofdepression Jco2005jesusprietusNo ratings yet

- The Holistic Approach to Redefining Cancer: Free Your Mind, Embrace Your Body, Feel Your Emotions, Nourish Your SoulFrom EverandThe Holistic Approach to Redefining Cancer: Free Your Mind, Embrace Your Body, Feel Your Emotions, Nourish Your SoulNo ratings yet

- MBA Internship ReportDocument47 pagesMBA Internship Reportডক্টর স্ট্রেইঞ্জ100% (1)

- Gonzales vs. Rufino HechanovaDocument3 pagesGonzales vs. Rufino Hechanovamarc abellaNo ratings yet

- Mac 5000Document228 pagesMac 5000anwar1971No ratings yet

- Final DPR Bareilly PDFDocument197 pagesFinal DPR Bareilly PDFPatan Abdul Mehmood Khan100% (1)

- Design of Speed Controller For Squirrel-Cage Induction Motor Using Fuzzy Logic Based TechniquesDocument9 pagesDesign of Speed Controller For Squirrel-Cage Induction Motor Using Fuzzy Logic Based TechniquessmithNo ratings yet

- Review Questions Exam 2 ECDocument3 pagesReview Questions Exam 2 ECSandip AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Digital Switching Concept - ADET - FINALDocument35 pagesDigital Switching Concept - ADET - FINALAMIT KUMARNo ratings yet

- WWW Techomsystems Com AuDocument7 pagesWWW Techomsystems Com Autechomsystems stemsNo ratings yet

- BBH 470 Assignment 3 SEPT 2022-1Document4 pagesBBH 470 Assignment 3 SEPT 2022-1Rubini ShivNo ratings yet

- Teaching With Simulations: What Are Instructional Simulations?Document4 pagesTeaching With Simulations: What Are Instructional Simulations?Norazmah BachokNo ratings yet

- Women On WheelsDocument19 pagesWomen On Wheelsmaitrishah_18No ratings yet

- Bridging The Gap - Decoding The Intrinsic Nature of Time in Market DataDocument15 pagesBridging The Gap - Decoding The Intrinsic Nature of Time in Market DatashayanNo ratings yet

- A Demonstration Plan in EPP 6 I. Learning OutcomesDocument4 pagesA Demonstration Plan in EPP 6 I. Learning Outcomeshezil CuangueyNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document48 pagesModule 1ronaleneoNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Naturopathy PDFDocument8 pagesAn Introduction To Naturopathy PDFrentpe propertyNo ratings yet

- Akhil MMDocument32 pagesAkhil MMAkshay Kumar RNo ratings yet

- Mineral Resources of BangladeshDocument25 pagesMineral Resources of BangladeshFOuadHasan100% (1)

- Skripta - Teorija Iz.... (Za Ispit)Document46 pagesSkripta - Teorija Iz.... (Za Ispit)Mahmad FatihNo ratings yet

- BS 4466Document25 pagesBS 4466Umange Ranasinghe100% (6)

- Imds Newsletter 53Document4 pagesImds Newsletter 53taleshNo ratings yet

- Column DesignDocument26 pagesColumn DesignZakwan ZakariaNo ratings yet

- ME Part2Malaria Toolkit enDocument39 pagesME Part2Malaria Toolkit enWassim FekiNo ratings yet

- 7plus Unit 1 Lesson 1 Opposite Quantities Combine To Make ZeroDocument6 pages7plus Unit 1 Lesson 1 Opposite Quantities Combine To Make Zeroapi-261894355No ratings yet

- Home Automation SystemDocument10 pagesHome Automation SystemrutvaNo ratings yet

- 1z0 447 DemoDocument5 pages1z0 447 Demojosegitijose24No ratings yet

- GUNN DiodeDocument29 pagesGUNN DiodePriyanka DasNo ratings yet

- API 580 MCQs (119 Nos.)Document19 pagesAPI 580 MCQs (119 Nos.)Qaisir MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Table Manners in A Formal Restaurant. 1.: Make Good Use of Your Napkin. Place Your Napkin in Your Lap Immediately UponDocument2 pagesTable Manners in A Formal Restaurant. 1.: Make Good Use of Your Napkin. Place Your Napkin in Your Lap Immediately UponAllen KateNo ratings yet