Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Role of Physical Therapists in The Management of Individuals at Risk For or Diagnosed With Venous Thromboembolism - Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline

Role of Physical Therapists in The Management of Individuals at Risk For or Diagnosed With Venous Thromboembolism - Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline

Uploaded by

Pascha ParamurthiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Role of Physical Therapists in The Management of Individuals at Risk For or Diagnosed With Venous Thromboembolism - Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline

Role of Physical Therapists in The Management of Individuals at Risk For or Diagnosed With Venous Thromboembolism - Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline

Uploaded by

Pascha ParamurthiCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Practice

Guideline

Role of Physical Therapists in the

Management of Individuals at Risk

for or Diagnosed With Venous

Thromboembolism: Evidence-Based

Clinical Practice Guideline E. Hillegass, PT, EdD, CCS,

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

FAACVPR, FAPTA, Department of

Ellen Hillegass, Michael Puthoff, Ethel M. Frese, Mary Thigpen, Dennis C. Sobush, Physical Therapy, Mercer Univer-

Beth Auten; for the Guideline Development Group sity, 220 Lackland Ct, Atlanta, GA

30350 (USA). Address all corre-

spondence to Dr Hillegass at:

The American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), in conjunction with the Cardiovascular & ezhillegass@gmail.com.

Pulmonary and Acute Care sections of APTA, have developed this clinical practice guideline to M. Puthoff, PT, PhD, GCS, Depart-

assist physical therapists in their decision-making process when treating patients at risk for ment of Physical Therapy, St

venous thromboembolism (VTE) or diagnosed with a lower extremity deep vein thrombosis Ambrose University, Davenport,

(LE DVT). No matter the practice setting, physical therapists work with patients who are at risk Iowa.

for or have a history of VTE. This document will guide physical therapist practice in the

E.M. Frese, PT, DPT, MHS, CCS,

prevention of, screening for, and treatment of patients at risk for or diagnosed with LE DVT.

Department of Physical Therapy,

Through a systematic review of published studies and a structured appraisal process, key St Louis University, St Louis,

action statements were written to guide the physical therapist. The evidence supporting each Missouri.

action was rated, and the strength of statement was determined. Clinical practice algorithms,

based on the key action statements, were developed that can assist with clinical decision M. Thigpen, PT, PhD, NCS,

making. Physical therapists, along with other members of the health care team, should work Department of Physical Therapy,

Brenau University, Gainesville,

to implement these key action statements to decrease the incidence of VTE, improve the

Georgia.

diagnosis and acute management of LE DVT, and reduce the long-term complications of LE

DVT. D.C. Sobush, PT, MA, DPT, CCS,

CEEAA, Department of Physical

Therapy, Marquette University,

Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

B. Auten, MLIS, MA, AHIP, Library,

South Piedmont Community Col-

lege, Monroe, North Carolina.

See eAppendix 1 (available at

ptjournal.apta.org) for brief

author biographies.

[Hillegass E, Puthoff M, Frese EM,

et al; for the Guideline Develop-

ment Group. Role of physical ther-

apists in the management of indi-

viduals at risk for or diagnosed

with venous thromboembolism:

evidence-based clinical practice

guideline. Phys Ther. 2016;96:

143–166.]

© 2016 American Physical Therapy

Association

Published Ahead of Print:

October 29, 2015

Accepted: September 24, 2015

Submitted: May 12, 2015

Post a Rapid Response to

this article at:

ptjournal.apta.org

February 2016 Volume 96 Number 2 Physical Therapy f 143

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

V enous thromboembolism (VTE) is

the formation of a blood clot in a

deep vein that can lead to compli-

cations, including deep vein thrombosis

(DVT), a pulmonary embolism (PE), or

• Provide physical therapists with

specific tools to identify patients

who may have an LE DVT and deter-

mine the likelihood of an LE DVT.

• Assist physical therapists in deter-

ranges from 70 to 120 cases per 100,000

inhabitants per year, and in Europe there

are between 140 and 240 cases per

100,000 inhabitants per year, with sud-

den death being a frequent outcome.7

postthrombotic syndrome (PTS). Venous mining when mobilization is safe

thromboembolism is a serious condition, for a patient diagnosed with an LE Deep vein thrombosis is a serious, yet

with an incidence of 10% to 30% of peo- DVT based on the treatment cho- potentially preventable, medical condi-

ple dying within 1 month of diagnosis, sen by the interprofessional team. tion that occurs when a blood clot forms

and half of those diagnosed with a DVT • Describe interventions that will in a deep vein, most commonly in the

have long-term complications.1 Even decrease diagnosis complications, calf, thigh, or pelvis. A life-threatening,

with a standard course of anticoagulant such as PTS or another VTE. acute complication of LE DVT is PE. This

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

therapy, one third of individuals will • Create a reference publication for complication occurs when the clot dis-

experience another VTE within 10 health care providers, patients, fam- lodges, travels through the venous sys-

years.1 For those who survive a VTE, ilies and caretakers, educators, pol- tem, and causes a blockage in the pulmo-

quality of life can be decreased due to icy makers, and payers on the best nary circulatory system. A proximal LE

the need for long-term anticoagulation to current practice of physical thera- DVT, defined as occurring in the popli-

prevent another VTE.2 pist management of patients at risk teal vein or veins more cephalad, is asso-

for VTE and diagnosed with an LE ciated with an estimated 50% risk of PE if

No matter the practice setting, physical DVT. not treated, as compared with approxi-

therapists work with patients who are at • Identify areas of research that are mately 20% to 25% of LE DVTs below the

risk for or have a history of VTE. Addi- needed to improve the evidence knee.8 Approximately 1 in 5 individuals

tionally, physical therapists are routinely base for physical therapist manage- with acute PE die almost immediately,

tasked with mobilizing patients immedi- ment of patients at risk for or diag- and 40% will die within 3 months.9 In

ately after diagnosis of a VTE. Because of nosed with VTE. those who survive PE, significant cardio-

the seriousness of VTE, the frequency pulmonary morbidity can occur, most

This CPG, which contains 14 key action

that physical therapists encounter notably CTEPH.

statements (Tab. 1), can be applied to

patients with a suspected or confirmed

adult patients across all practice settings,

VTE, and the need to prevent future VTE, Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary

but it does not address or apply to

the American Physical Therapy Associa- hypertension can be the result of a single

women who are pregnant or to children.

tion (APTA) in conjunction with the Car- PE, multiple PEs, or recurrent PEs.

Additionally, this guideline does not dis-

diovascular & Pulmonary and Acute Care Acutely, PE causes an obstruction of

cuss the management of PE, upper

sections of APTA, support the develop- flow. This narrowing of the lumen may

extremity DVT (UE DVT), or chronic

ment of this clinical practice guideline lead to reduced oxygenation and pulmo-

thromboembolic pulmonary hyperten-

(CPG). It is intended to assist all physical nary hypertension. Chronically, the

sion (CTEPH). Although primarily writ-

therapists in their decision making pro- infarction of lung tissue following PE

ten for physical therapists, other health

cess when managing patients at risk for may result in a reduction of vasculariza-

care professionals should find this CPG

VTE or diagnosed with a lower extremity tion and concomitant pulmonary hyper-

helpful in their treatment of patients

deep vein thrombosis (LE DVT). tension. Over time, the workload

who are at risk for or have a diagnosed

VTE. imposed on the right heart increases and

In general, CPGs optimize the care of contributes to right heart dysfunction

patients by building upon the best evi- and then failure.10 A new syndrome,

dence available while examining the

Background and Need for a post-PE syndrome, has more recently

benefits and risks of each care option.3 CPG on VTE been proposed to capture those patients

The VTE Guideline Development Group Venous thromboembolism is a life- with persistent abnormal cardiac and

(GDG) followed a systematic process to threatening disorder that ranks as the

write this CPG with the overall objective third most common cardiovascular ill-

of providing physical therapists with the ness, after acute coronary syndrome and

stroke.4 This disorder consists of DVT

Available With

best evidence in preventing VTE, screen- This Article at

ing for LE DVT, mobilization of patients and PE, 2 interrelated primary conditions

caused by venous blood clots, along with

ptjournal.apta.org

with LE DVT, and management of com-

plications of LE DVT. Specifically, this several secondary conditions including

• eTable: Current

CPG will: PTS and CTEPH.5 From primary and sec-

Anticoagulation Options in Use

ondary prevention perspectives, the seri-

• Discuss the role of physical thera- ousness of VTE development related to • eAppendix 1: Brief Author

pists in identifying patients who are mortality, morbidity, and diminished life Biographies

at high risk for a VTE and actions quality is a worldwide concern.6 The • eAppendix 2: AGREE II Review of

that can be taken to decrease the incidence of VTE differs greatly among Current Guideline

risk of a first or recurring VTE. countries. For example, the United States

144 f Physical Therapy Volume 96 Number 2 February 2016

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

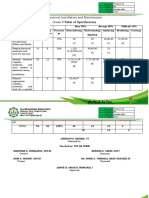

Table 1.

Key Action Statementsa

Number Statement Key Phrase

1 Physical therapists should advocate for a culture of mobility and physical activity unless Advocate for a culture of mobility and physical

medical contraindications for mobility exist. activity

(Evidence Quality: I; Recommendation Strength: A–Strong)

2 Physical therapists should screen for risk of VTE during the initial patient interview and Screen for risk of VTE

physical examination.

(Evidence Quality: I; Recommendation Strength: A–Strong)

3 Physical therapists should provide preventive measures for patients who are identified Provide preventive measures for LE DVT

as high risk for LE DVT. These measures should include education regarding signs

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

and symptoms of LE DVT, activity, hydration, mechanical compression, and referral

for medication.

(Evidence Quality: I; Recommendation Strength: A–Strong)

4 Physical therapists should recommend mechanical compression (eg, IPC, GCS) when Recommend mechanical compression as a

individuals are at high risk for LE DVT. preventive measure for LE DVT

(Evidence Quality: I; Recommendation Strength: A–Strong)

5 Physical therapists should establish the likelihood of an LE DVT when the patient has Identify the likelihood of LE DVT when signs

pain, tenderness, swelling, warmth, or discoloration in the lower extremity. and symptoms are present

(Evidence Quality: II; Recommendation Strength: B–Moderate)

6 Physical therapists should recommend further medical testing after the completion of Communicate the likelihood of LE DVT and

the Wells criteria for LE DVT prior to mobilization. recommend further medical testing

(Evidence Quality: I; Recommendation Strength: A–Strong)

7 When a patient has a recently diagnosed LE DVT, physical therapists should verify Verify the patient is taking an anticoagulant

whether the patient is taking an anticoagulant medication, what type of

anticoagulant medication, and when the anticoagulant medication was initiated.

(Evidence Quality: V; Recommendation Strength: D–Theoretical/Foundational)

8 When a patient has a recently diagnosed LE DVT, physical therapists should initiate Mobilize patients who are at a therapeutic

mobilization when therapeutic threshold levels of anticoagulants have been reached. level of anticoagulation

(Evidence Quality: I; Recommendation Strength: A–Strong)

9 Physical therapists should recommend mechanical compression (eg, IPC, GCS) when a Recommend mechanical compression for

patient has an LE DVT. patients with LE DVT

(Evidence Quality: II; Recommendation Strength: B–Moderate)

10 Physical therapists should recommend that patients be mobilized, once Mobilize patients after IVC filter placement

hemodynamically stable, following IVC filter placement. once hemodynamically stable

(Evidence Quality: V; Recommendation Strength: P–Best Practice)

11 When a patient with a documented LE DVT below the knee is not treated with Consult with the medical team when a patient

anticoagulation and does not have an IVC filter and is prescribed out of bed is not anticoagulated and without an IVC

mobility by the physician, the physical therapist should consult with the medical filter

team regarding mobilizing versus keeping the patient on bed rest.

(Evidence Quality: V; Recommendation Strength: P–Best Practice)

12 Physical therapists should screen for fall risk whenever a patient is taking an Screen for fall risk

anticoagulant medication.

(Evidence Quality: III; Recommendation Strength: C–Weak)

13 Physical therapists should recommend mechanical compression (eg, intermittent Recommend mechanical compression when

pneumatic compression, graduated compression stockings) when a patient has signs signs and symptoms of PTS are present

and symptoms suggestive of PTS.

(Evidence Quality: I; Recommendation Strength: A–Strong)

14 Physical therapists should monitor patients who may develop long-term consequences Implement management strategies to prevent

of LE DVT (eg, PTS severity) and provide management strategies that prevent them future VTE

from occurring to improve the human experience and increase quality of

life. (Evidence Quality: V; Recommendation Strength: P–Best Practice)

a

VTE⫽venous thromboembolism, LE DVT⫽lower extremity deep vein thrombosis, IPC⫽intermittent pneumatic compression, GCS⫽graduated compression

stockings, IVC⫽inferior vena cava, PTS⫽postthrombotic syndrome.

February 2016 Volume 96 Number 2 Physical Therapy f 145

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

pulmonary function who do not meet practice in the prevention of, screening to key words. Results were limited to

the criteria for CTEPH.5 These condi- for, and treatment of patients at risk for articles written in English. The search

tions are associated with diminished or diagnosed with LE DVT. This CPG is strategy by key words, MeSH terms, and

function and lowered quality of life.11 based on a systematic review of pub- databases is shown in Table 2. Using this

lished studies on the risks of early ambu- search strategy, 350 out of 8,652

Beyond the threat of PE and its sequelae, lation in patients with diagnosed DVT abstracts and citations of relevance were

LE DVT may lead to long-term complica- and on other established clinical guide- obtained from Web of Science, CINAHL,

tions. Postthrombotic syndrome is the lines on prevention, risk factors, and PubMed, and Cochrane Database of Sys-

most frequent complication and devel- screening for VTE and PTS. In addition to tematic Reviews.

ops in up to 50% of these patients even providing practice recommendations,

when an appropriate anticoagulant is this guideline also addresses gaps in the Clinical practice guidelines published

used.12,13 A clot remaining in the vein of evidence and areas that warrant further between 2003 and 2014 were searched

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

the lower extremity can obstruct blood investigation. including the same key words and MeSH

flow, leading to venous hypertension. terms using the National Guideline Clear-

Additionally, damage to the vein itself Methods inghouse (NGC, http://www.guideline.

occurs and leads to inflammation and The GDG, which comprised physical gov/) database and the Trip database

necrosis of the vein, which eventually therapists with special interest in acute (http://www.tripdatabase.com/). The

are removed by phagocytic cells, leading care and cardiovascular and pulmonary NGC database identified 169 guidelines,

to venous hypertension. This impaired practice, was appointed by the Cardio- of which 40 were deemed as appropriate

blood flow can lead to classic symptoms vascular & Pulmonary and the Acute to be reviewed. Three additional guide-

of PTS, which often includes chronic Care sections of APTA to develop a lines were identified through the Trip

aching pain, intractable edema, limb guideline to address the physical thera- database, and the appropriate target pop-

heaviness, and leg ulcers.10 This chronic pist’s role in the management of VTE. ulations were included.

pathology can cause serious long-term ill Specifically, the role of mobility was

health, impaired functional mobility, identified as a major issue facing both Method: Literature Review

poor quality of life, and increased costs sections. Models used by the APTA Pedi- Procedures

for the patient and the health care system. atric Section for its CPG on physical ther- The results of the literature and guideline

apy management of congenital muscular searches were distributed to the mem-

Across various practice settings, physical torticollis14 were primarily used to bers of the GDG. One member of the

therapists encounter patients who are at develop this CPG, as well as other APTA- group reviewed a list of citations, and

risk for VTE, may have an undiagnosed supported CPGs and international pro- another member performed a second

LE DVT, or have recently been diagnosed cesses. In July 2012, the GDG initiated review of the same list of citations. Arti-

with an LE DVT. The physical therapist’s the process under the guidance of APTA cles were included based on whether

responsibility to every patient is 5-fold: and developed a list of topic areas to be key topics were addressed and the

(1) prevention of VTE, (2) screening for covered by the CPG. In addition, topic appropriate target populations were

LE DVT, (3) contributing to the health areas were solicited from clinicians with included. Case reports and pediatric arti-

care team in making prudent decisions content experience in the area of VTE cles were excluded. The GDG, along

regarding safe mobility for these who volunteered to assist. A resultant list with clinicians and academicians who

patients, (4) patient education and of topic areas was developed to deter- volunteered from both the Cardiovascu-

shared decision making, and (5) preven- mine the scope of the CPG and provided lar & Pulmonary Section and the Acute

tion of long-term consequences of LE the GPG with limits to the literature Care Section, were invited to review the

DVT. Such decisions should always be search. identified literature.

made in collaboration with the referring

physician and other members of the Literature Review Reliability of appraisers was established

health care team (ie, it is assumed that A search strategy was developed and per- prior to articles being reviewed. Selected

such decisions will not be made in isola- formed by a librarian to identify literature articles were reviewed by 3 individuals

tion and that the physical therapist will published between May 1, 2003, and who used 1 of 3 critical appraisal tools

communicate with the medical team). May 2014 addressing mobilization adapted from an evidence-based practice

and anticoagulation therapy to prevent textbook to evaluate each according to

Due to the long-standing controversy and treat VTE. Searches were performed its type (ie, critical appraisal for studies

regarding mobilization versus bed rest in the following databases: PubMed, of prognosis, diagnosis, or interven-

following VTE diagnosis and with the CINAHL, Web of Science, Cochrane tion).15 The Assessment of Multiple Sys-

development of new anticoagulation Database of Systematic Reviews, Data- tematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool was

medications, the physical therapy com- base of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects used for systematic reviews.16 Selected

munity needs evidence-based guidelines (DARE), and the Physiotherapy Evidence diagnosis, prognosis, and intervention

to assist in clinical decision making. This Database (PEDro). Controlled vocabular- articles and systematic reviews were crit-

CPG is intended to be used as a reference ies, such as MeSH and CINAHL headings, ically appraised by the GDG to establish

document to guide physical therapist were used whenever possible in addition test standards. Interrater reliability

146 f Physical Therapy Volume 96 Number 2 February 2016

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

Table 2.

Search Strategy by Key Words, MeSH Terms, and Databases

Key Words MeSH Terms Databases

DVT “Venous Thrombosis” PubMed

“Venous Thrombosis” “Pulmonary Embolism” CINAHL

“Deep Vein Thrombosis” “Walking” Web of Science

VTE “Movement” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews

“Venous Thromboembolism“ “Immobilization” Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

“Pulmonary Embolism” “Mobility Limitation” Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro)

Walking “Motor Activity”

Walk “Early Ambulation”

Ambulation “Activities of Daily Living”

Ambulate “Anticoagulants”

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

Ambulated “Coumarins”

Movement “Fibrin Modulating Agents”

Mobility “Factor Xa/antagonists and inhibitors”

Immobilization “Thrombosis/prevention and control”

Immobilisation “Antithrombins”

“Mobility Limitation” “Citric Acid”

“Motor Activity” “Heparinoids”

“Early Ambulation” “Vitamin K/antagonists and inhibitors”

“Early Activization” “Antithrombin Proteins”

“Early Activisation” “Fibrinolytic Agents”

“Early Mobilization” “International Normalized Ratio”

“Early Mobilisation” “Prothrombin Time”

Anticoagulants “Vena Cava Filters”

Anticoagulant “Intermittent Pneumatic Compression Devices”

Anticoagulation “Stockings, Compression”

Dabigatran

Desirudin

Ximelagatran

Edoxaban

Rivaroxaban

Apixaban

Betrixaban

“YM150”

Razaxaban

“Factor Xa Inhibitor”

“Direct Thrombin Inhibitors”

“Direct Thrombin Inhibitor”

Coumadin

Warfarin

Fondaparinux

Idraparinux

“International Normalized Ratio“

“INR”

“Prothrombin Time”

“Vena Cava Filter*”

“Intermittent Pneumatic Compression Devices”

“Compression Stockings”

“Compression Socks”

“Compression Hose”

“Compression Hosiery”

among the 4 core group members was Clinical practice guidelines were tool to evaluate CPGs with subsequent

first established on test articles. Volun- reviewed that fit the scope of this CPG reliability testing being performed on all

teers completed critical appraisals of the and the patient population. Guidelines reviewers.

test articles to establish interrater reliabil- were included based on whether key

ity. Volunteers qualified to be appraisers topics were addressed and the target Levels of Evidence and Grades of

with agreement of 90% or more. Apprais- populations were included. The results Recommendations

ers were randomly paired to read each of of the CPG search were reviewed by one The GDG followed a previously pub-

the remaining diagnostic, prognostic, or member of the GDG. Four additional lished process on developing physical

intervention articles. Discrepancies in clinical expert volunteers underwent therapy CPGs.14 Table 3 lists criteria used

scoring between the readers were training in the Appraisal of Guidelines for to determine the level of evidence asso-

resolved by a member of the GDG. Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II)17 ciated with each practice statement,

February 2016 Volume 96 Number 2 Physical Therapy f 147

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

Table 3. ical interpretation. The statements are

Levels of Evidencea organized in Table 1 according to the

action statement number, the statement,

Level Criteria

and the key phrase or action statement.

I Evidence obtained from high-quality diagnostic studies, prognostic or prospective studies,

cohort studies or randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses or systematic reviews

(critical appraisal score ⬎50% of criteria) AGREE II Review

This CPG was evaluated by 5 GPG mem-

II Evidence obtained from lesser-quality diagnostic studies, prognostic or prospective studies,

cohort studies or randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses or systematic reviews (eg,

bers using the AGREE II instrument to

weaker diagnostic criteria and reference standards, improper randomization, no assess the methodological quality of the

blinding, ⬍80% follow-up) (critical appraisal score ⬍50% of criteria) guideline. The 5 members scored this

III Case-controlled studies or retrospective studies guideline as high quality according to the

AGREE II tool (eAppendix 2, available at

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

IV Case studies and case series

ptjournal.apta.org).

V Expert opinion

a

Reprinted from Kaplan S, Coulter C, Fetters L. Developing evidence-based physical therapy External Review Process by

clinical practice guidelines. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2013;25:257–270, with permission of Wolters Kluwer Stakeholders

Health Inc.

This CPG underwent 2 formal reviews.

First, draft reviewers were invited stake-

holders representing the American Col-

lege of Chest Physicians, Society for Vas-

with level I as the highest level of evi- Statements that received an A or B grade

cular Nursing, physical therapy clinicians

dence and level V as the lowest level of should be considered as well supported.

and researchers, and patient representa-

evidence. Table 4 presents the criteria The CPG lists each key action statement

tives. The second draft was posted for

for the grades assigned to each action followed by rating of level of evidence

public comment on both the APTA Car-

statement. The grade reflects the overall and grade of the recommendation.

diovascular & Pulmonary Section and

and highest levels of evidence available Under each statement is a summary pro-

Acute Care Section websites; notices

to support the action statement. viding the supporting evidence and clin-

were sent via email and an electronic

newsletter to Cardiovascular & Pulmo-

nary Section members, literature apprais-

Table 4. ers, and clinicians who inquired about

Grades of Recommendation for Action Statementsa the CPG during its development.

Grade Recommendation Quality of Evidence

Document Structure

A Strong A preponderance of level I studies but at least 1 level I The action statements organized in Table

study directly on the topic support the

recommendation. 1 are introduced with their assigned rec-

ommendation grade, followed by a stan-

B Moderate A preponderance of level II studies but at least 1 level

dardized content outline generated by

II study directly on the topic support the

recommendation. BRIDGE-Wiz software (http://gem.med.

yale.edu/BRIDGE-Wiz/).18 Each state-

C Weak A single level II study at ⬍25% critical appraisal score

or a preponderance of level III and IV studies, ment has a content title, a recommenda-

including statements of consensus by content tion in the form of an observable action

experts support the recommendation. statement, indicators of the evidence

D Theoretical/foundational A preponderance of evidence from animal or cadaver quality, and the strength of the recom-

studies, from conceptual/theoretical mendation. The action statement profile

models/principles, or from basic science/bench describes the benefits, harms, and costs

research, or published expert opinion in peer- associated with the recommendation; a

reviewed journals supports the recommendation.

delineation of the assumptions or judg-

P Best practice Recommended practice based on current clinical ments made by the GDG in formatting

practice norms, exceptional situations where

the recommendation; reasons for any

validating studies have not or cannot be performed

and there is a clear benefit, harm, or cost, and/or intentional vagueness in the recommen-

the clinical experience of the guideline dation; and a summary and clinical inter-

development group. pretation of the evidence supporting the

R Research There is an absence of research on the topic, or recommendation. The Delphi process

higher-quality studies conducted on the topic was used to determine level of evidence

disagree with respect to their conclusions. The and recommended strength for each key

recommendation is based on these conflicting

action statement. Each member of the

conclusions or absent studies.

GPG reviewed the supporting evidence

a

Reprinted from Kaplan S, Coulter C, Fetters L. Developing evidence-based physical therapy clinical for each key action statement and voted

practice guidelines. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2013;25:257–270, with permission of Wolters Kluwer Health Inc.

148 f Physical Therapy Volume 96 Number 2 February 2016

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

Key Action Statements

With Evidence

Action Statement 1: Advocate for

a culture of mobility and physical

activity

Physical therapists and other health

care practitioners should advocate

for a culture of mobility and physical

activity. (Evidence Quality: I; Recom-

mendation Strength: A–Strong)

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

Action statement profile

Aggregate Evidence Quality: Level I

Benefits: Decreased likelihood of LE

DVT and/or PE and/or PTS

Risk, Harm, Cost: Injuries from falls

Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponder-

ance of benefit

Figure 1. Value Judgments: Physical therapists

Algorithm for screening for risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). should advocate for mobility in all situa-

tions due to the evidence on the benefits

of activity and risks associated with inac-

on level of evidence and strength of rec- ing aspects of physical therapists’ man- tivity and bed rest except when there

ommendation independent of the other agement of patients with potential or could be a risk of harm (eg, emboli

group members using a Google survey diagnosed VTE. The CPG addresses these depositing in the pulmonary system).

upon which all votes were tallied and aspects of VTE management via 14 Intentional Vagueness: None

then reported. action statements. Clinical practice algo- Role of Patient Preferences: As the

rithms (Figs. 1, 2, and 3), based on the evidence for risks associated with inac-

tivity is strong and with little associated

Scope of the Guideline key action statements, were developed

that can assist with clinical decision risk of mobility in the absence of throm-

This CPG uses literature available from

making. boembolism, patients should be edu-

2003 through 2014 to address the follow-

Figure 2.

Algorithm for determining likelihood of a lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (LE DVT). DVT⫽deep vein thrombosis.

February 2016 Volume 96 Number 2 Physical Therapy f 149

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

Figure 3.

Algorithm for mobilizing patients with known lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. DVT⫽deep vein thrombosis, LMWH⫽low-molecular-

weight heparin, UFH⫽unfractionated heparin, NOAC⫽novel oral anticoagulants, INR⫽international normalized ratio, IVC⫽inferior vena

cava. *If started on Coumadin, LMWH usually also started. Use LMWH guidelines for mobilization decision in these situations.

cated regarding the benefits of mobility reduction in mobility, the risk for VTE is utes or if the surgical procedure involves

and encouraged to maintain mobility as significantly increased. Increased age the pelvis or lower limb and anesthesia

much as possible to decrease the risk of serves as an example. One study of hos- time is greater than 60 minutes, the risk

adverse outcomes. pitalized patients older than 65 years is much greater. Individuals who are

Exclusions: None found reduced mobility to be an inde- admitted acutely for surgical reasons or

pendent risk factor for VTE. The risk admitted with inflammatory or intra-

Summary of evidence increased based on the degree of immo- abdominal conditions also are at high

Reduced mobility is a known risk factor bility, and relative risk scores were risk for developing a VTE. These same

for VTE, yet the quantity and duration of derived according to the degree of immo- guidelines emphasized the need to iden-

the reduced mobility that defines degree bility (Tab. 5).19,25 The OR risk was tify all individuals who are expected to

of risk for VTE are not known.19 –21 Sig- found to be higher in older patients with have any significant reductions in mobil-

nificant variability exists in the literature more severe limitation of mobility (bed ity to be at risk for VTE and to mobilize

regarding reduced mobility and the rest versus wheelchair) and when the them as soon as possible.20 The Ameri-

resulting risk for VTE.22 Patients who loss of mobility was more recent (⬍15 can College of Chest Physicians (ACCP)

were ambulatory were found to be at days versus ⬎30 days). guidelines emphasize prevention of VTE

increased risk for developing a VTE with in patients not undergoing surgery by

a standing time of 6 or more hours (odds Recent national guidelines have associ- incorporating nonpharmacological pro-

ratio [OR]⫽1.9) or resting in bed or a ated reduced mobility with increased phylaxis measures, including frequent

chair (OR⫽5.6).23 Likewise, a significant risk for VTE.20,26 The National Institute ambulation, calf muscle exercise, and sit-

correlation exists between loss of mobil- for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) ting in the aisle and mobilizing the lower

ity status for 3 or more days and the guidelines present strong recommenda- extremities when traveling (Grade 2C

presence of LE DVT on duplex tions for the need to regard patients recommendations).26,27

ultrasound.24 undergoing surgery and patients with

trauma as at an increased risk of VTE. Previously, when individuals were diag-

When additional risk factors for VTE are When patients undergo surgery with an nosed with an LE DVT, they were placed

present in an individual who has any anesthesia time of greater than 90 min- on bed rest due to the concern that

150 f Physical Therapy Volume 96 Number 2 February 2016

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

Table 5. inherited thrombophilia, and obesity.

Reduced Mobility as a Risk Factor for Venous Thromboembolism19,25,a The relationship between particular risk

factors and presence of LE DVT has been

Degree of

Immobility OR 95% CI P

found through retrospective and pro-

spective studies and identified as having

Normal 1.0

support from level I evidence in other

Limited 1.73 1.08, 2.75 .02 CPGs.19,31–34

Wheelchair 30 d 2.43 1.37, 4.30 .002

Bed rest 30 d 2.73 1.20, 6.20 .02

The need for all health care providers to

screen for risk of LE DVT through

Wheelchair 15–30 d 3.33 1.26, 8.84 .02

system-wide approaches has been high-

Bed rest 15–20 d 3.37 1.00, 11.29 .05 lighted by the US Agency for Healthcare

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

Wheelchair 15 d 4.32 1.50, 12.45 .007 Research and Quality,35 the Finnish Med-

ical Society,31 and the Scottish Intercol-

Bed rest ⬍15 d 5.64 2.04, 15.56 .0008

legiate Guidelines Network,36 and such

a

OR⫽odds ratio, CI⫽confidence interval. screening is strongly recommended by

each of these groups. Furthermore, the

importance of screening was strongly

supported in a 2008 multinational cross-

ambulation would cause clot dislodg- Action statement profile sectional study of patients from more

ment and lead to a potentially fatal PE. Aggregate Evidence Quality: Level I than 350 hospitals across 32 countries.

However, a meta-analysis compiled data Benefits: Prevention or early detection The findings revealed that 39.5% of

from 5 randomized controlled trials of LE DVT patients at risk for VTE were not receiv-

(RCTs) on more than 3,000 patients and Risk, Harm, and Cost: Adverse effects ing appropriate prophylaxis.37 Hospital-

concluded that early ambulation follow- of prophylaxis interventions wide strategies were recommended to

ing diagnosis of an LE DVT was not asso- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponder- assess patients’ VTE risk and to monitor

ciated with a higher incidence of a new ance of benefit over harm whether those at risk received appropri-

PE or progression of LE DVT compared Value Judgments: None ate prophylaxis.

with bed rest.28 Rather, there was a Intentional Vagueness: Physical thera-

lower incidence of new PE and overall pists should work within their health To facilitate and standardize the process

mortality in those patients who engaged care system to determine specific algo- of screening for risk within health care

in early ambulation. Similar findings, as rithms or risk assessment models (RAMs) systems and across professions, RAMs

well as more rapid resolution of pain, to use. should be considered.36,38 Risk assess-

were reported in a systematic review Role of Patient Preferences: None ment models use a checklist to deter-

that included 7 RCTs and 2 prospective Exclusions: None mine whether risk factors for LE DVT are

observational studies.29 The importance present and each risk factor is assigned a

of mobility is further discussed in key Summary of evidence point value. If a set point level is reached,

Action Statement 8. The Guide to Physical Therapist Prac- the patient is considered at an increased

tice states that the physical therapist risk, and more aggressive prophylactic

In summary, mobility should be encour- examination is a comprehensive screen- interventions can be used. There are

aged in patients while in the hospital and ing and specific testing process leading numerous examples of RAMs in the liter-

when discharged to prevent the compli- to diagnostic classification or, as appro- ature, including the Padua score for

cations associated with immobility. In priate, to a referral to another practitio- assessing VTE risk in hospitalized

addition, mobility is recommended for ner.30 Understanding the factors that patients,39 the IMPROVE VTE RAM,40 the

those diagnosed with VTE once thera- place individuals at risk for a VTE is Autar DVT Risk Assessment Scale,41 and

peutic anticoagulant levels have been important for all physical therapists. Dur- the Geneva Risk Score.42 None have

reached (see Action Statement 8). ing the patient interview, physical ther- been shown to be superior to others

apists should ask questions and review through direct comparisons, and, for this

Action Statement 2: Screen for the medical history to determine reason, the GDG cannot recommend a

risk of VTE whether the patient is at risk for LE DVT. single RAM. It is more important that

Physical therapists should screen for Risk factors include previous venous physical therapists work within their

risk of VTE during the initial patient thrombosis or embolism, age, active can- health care system to understand and

interview and physical examination cer or cancer treatment, severe infec- even help develop an overall VTE proto-

(Evidence Quality: I; Recommenda- tion, oral contraceptives, hormonal col that uses an agreed-upon tool for VTE

tion Strength: A–Strong) replacement therapy, pregnancy or risk assessment.

given birth within the previous 6 weeks,

immobility (bed rest, flight travel, frac- In summary, given the risks and harms

tures), surgery, anesthesia, critical care associated with a VTE and the relation-

admission, central venous catheters,

February 2016 Volume 96 Number 2 Physical Therapy f 151

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

ship of VTE incidence to the presence of follow-up monitoring, importance of Value Judgments: None

risk factors, physical therapists should treatment adherence, and medication Intentional Vagueness: Specific types

screen for VTE risk. These results should issues (eg, regimen, adverse side effects of mechanical compression were not

be communicated with the rest of the and interactions, dietary restrictions).44 recommended. Physical therapists

health care team. should work within their health care sys-

Immobilization is one of the primary risk tem to develop institution-specific

Action Statement 3: Provide factors for VTE and is a problem for protocols.

preventive measures for LE DVT patients in the home and in acute care Role of Patient Preferences: Ease of

Physical therapists should provide settings and long-term care facilities. use, comfort level, and ability to operate

preventive measures for LE DVT Immobility, as it relates to residents in mechanical compression equipment

for patients who are identified as long-term care facilities, is defined by the properly should be evaluated with each

being at risk for LE DVT. These mea- presence of at least one of the following: patient.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

sures should include education lower limb cast, bedridden, bedridden Exclusions: Patients who have severe

regarding signs and symptoms of LE except for bathroom privileges, recent peripheral neuropathy, decompensated

DVT, activity, hydration, mechanical decreased ability to walk at least 3.1 m heart failure, arterial insufficiency, der-

compression, and referral for medi- (10 ft) for a least 72 hours, and inability matologic diseases, or lesions may have

cation assessment. (Evidence Qual- to walk at least 3.1 m (10 ft).45 Patients contraindications to selective mechani-

ity: I; Recommendation Strength: who are limited to a chair or bed greater cal compression modes.

A–Strong) than half the day during waking hours

are considered at elevated risk for VTE. Summary of evidence

Action statement profile The acuteness and severity of the immo- The influence of mechanical compres-

Aggregate Evidence Quality: Level I bility determines the elevated risk level sion on LE DVT or PE prophylaxis was

Benefits: Prevention of LE DVT of developing VTE.19 examined in 7 systematic reviews.46 –52

Risk, Harm, Cost: None to minimal The populations included patients who

Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponder- As immobility also occurs with long- were in postoperative recovery from a

ance of benefit over harm distance travel, travelers on planes for variety of surgical procedures, with or

Value Judgments: None greater than 2 to 3 hours are also at without pharmacological prophylaxis.

Intentional Vagueness: None increased risk for LE DVT. The ACCP27 Also included were airline travelers of

Role of Patient Preferences: Patients recommends that such travelers ambu- varying VTE risk levels. These studies

may or may not choose to adhere to late frequently, perform calf muscle exer- supported that GCS used alone signifi-

preventive measures. There is a role for cises, sit in an aisle seat, and use below- cantly decreased the incidence of LE

having shared decision making with the-knee compression stockings with at DVT or PE and that this mechanical com-

regard to their priorities. least 15 to 30 mm Hg compression (2C pression method provided additional

Exclusions: None recommendation). benefit when combined with other pro-

phylactic methods. Although GCS was

Summary of evidence Action Statement 4: Recommend the method of mechanical compression

For individuals who are at risk for LE mechanical compression as a in all 7 of these publications, the descrip-

tive features of the GCS were

DVT, preventive measures should be ini- preventive measure for DVT

tiated immediately, including education inconsistent.

Physical therapists should recom-

regarding leg exercises, ambulation, mend mechanical compression (eg,

proper hydration, mechanical compres- intermittent pneumatic compres- Screening to identify VTE risk is essential

sion, and assessment regarding the need sion [IPC], graded compression and will identify which, if any, mechan-

for medication referral. stockings [GCS]) when individuals ical compression method is appropriate

are at moderate to high risk to implement. In the CPG of the Japanese

Education is a key factor in risk reduction for LE DVT or when anticoagulation Circulation Society for PE and LE DVT

of VTE and should be provided for is contraindicated. (Evidence Quali- prevention, elastic stockings or IPC, IPC

patients who are at elevated risk for LE ty: I; Recommendation Strength: or anticoagulation, and anticoagulation

DVT and for their families. Documenta- A–Strong) plus IPC or elastic stockings are recom-

tion of the patient’s understanding of mended for postoperative patients with

these concepts also should be elevated risk.53 The Institute for Clinical

Action statement profile

included.43 Topics that should be Systems Improvement guidelines for VTE

Aggregate Evidence Quality: Level I

included in this education program for prophylaxis recommend that if contrain-

Benefits: Prevents LE DVT without

these patients and their families are: risk dications exist for both low-molecular-

increasing the risk of bleeding

factors for DVT, possible consequences weight heparin (LMWH) and low-dose

Risk, Harm, Cost: Improper fit can lead

of DVT, interventions to decrease the unfractionated heparin (UFH) and there

to skin irritation, ulceration, or interrup-

risk of DVT, signs and symptoms of DVT is high risk for VTE but not high risk for

tion of blood flow.

and importance of seeking medical help bleeding, fondaparinux or low-dose aspi-

Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponder-

if DVT is suspected, importance of rin or IPC be used.43 One example would

ance of benefit over harm

152 f Physical Therapy Volume 96 Number 2 February 2016

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

be someone with a history of heparin- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponder- relationship has held up across multiple

induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). Inter- ance of benefit over harm subgroups of patients, including outpa-

mittent pneumatic compression or GCS Value Judgments: Although the Wells tients, inpatients, those with malignancy,

are recommended for patients who are criteria for LE DVT are recommended by and patients grouped by sex and previ-

acutely or critically ill and who are bleed- this GDG, there are other tools that may ous history of an LE DVT.

ing or are at high risk for major bleeding, be preferred by other interprofessional

until bleeding risk decreases, at which teams. In 2003, the Wells criteria for LE DVT

time pharmacological thromboprophy- Intentional Vagueness: None were modified to a 2-stage stratification

lactic methods can be substituted.38,54 Role of Patient Preferences: None (ie, LE DVT likely or LE DVT unlikely),

Exclusions: None and a history of previous LE DVT was

A systematic review of 6 RCTs looked at added to the tool.67 Reducing the model

patients at high risk for VTE who under- Summary of evidence to 2 levels made it easier to use and did

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

went various surgical procedures to The major signs and symptoms of LE not compromise patient safety when

assess the effectiveness of IPC combined DVT include pitting edema, pain, tender- used in conjunction with a D-dimer test.

with pharmacological prophylaxis ver- ness, swelling, warmth, redness or dis- Individuals with 2 or more points were

sus single modality usage.55 Combining coloration (erythema), and prominent categorized as likely, and those with less

IPC with an anticoagulant (eg, LMWH) superficial veins.36,45,61,62 The presence than 2 points were categorized as

was more effective in VTE prevention of these signs and symptoms should raise unlikely. In a study of 1,082 outpatients,

than either IPC or anticoagulant use the suspicion of an LE DVT, but they 27.9% (95% CI⫽23.9%, 31.8%) of those

alone, which is consistent with the CPG cannot be used alone in the diagnostic classified as likely had a proximal LE DVT

recommendation offered by the Japanese process.31,61 The likelihood of LE DVT or a PE. Of those patients classified as

Circulation Society. should be established through use of a unlikely, 5.5% (95% CI⫽3.8%, 7.6%) had

standardized tool. This recommendation a proximal LE DVT or a PE.

In summary, there is substantial support- is supported by numerous CPGs26,36,61,63

ive evidence for the use of mechanical and a meta-analysis.62 A standardized tool Beyond the Wells criteria for LE DVT,

compression methods for patients with uses the presence of clinical features of other risk stratification tools have been

medical conditions or undergoing sur- an LE DVT to determine the likelihood developed, but there are limited compar-

gery,36,56 – 60 prolonged air-flight travel- that an LE DVT is present and guides the ison studies among the tools. One exam-

ers,6,47,49 and patients in long-term care selection of the most appropriate test to ple is the Oudega rule, developed for

facilities.45 For those people at increased diagnose an LE DVT. Physical therapists primary care providers. When compared

risk for VTE, the use of GCS or IPC, with should use a standardized tool as part of to the Wells criteria for LE DVT, it has

or without anticoagulation therapy, is their examination process when signs similar effectiveness.68,69

considered to be beneficial. The evi- and symptoms of LE DVT are present.

dence is inconsistent, however, in The results of the assessment should The Wells criteria for LE DVT have a long

describing the optimal protocols for use then be communicated with the medical and well-supported history of success-

of GCS, elastic stockings, or IPC. Poten- team. fully stratifying risk or likelihood of LE

tial for rare circulatory compromise with DVT across patient populations and prac-

the use of GCS (ie, knee or thigh length) The Wells criteria for LE DVT are the tice settings; therefore, the GDG recom-

warrants proper fitting and careful mon- most commonly used tool to determine mends this tool for risk stratification.

itoring of skin condition by the patient likelihood of LE DVT (Tab. 6).21,64 Orig- Physical therapists should advocate for

and physical therapist. inally, the Wells criteria for LE DVT used its use with their interdisciplinary team

a 3-tier risk stratification of low, moder- and determine the best way to commu-

Action Statement 5: Identify the ate, and high. A score of 3 or greater was nicate the results and risks.

likelihood of LE DVT when signs high risk, a score of 1 to 2 was moderate

and symptoms are present risk, and a score of 0 or below was low Action Statement 6:

Physical therapists should establish risk. In a study of 593 patients, 16% had Communicate the likelihood of

the likelihood of LE DVT when the an LE DVT. When the rate of LE DVT was

LE DVT and recommend further

patient has pain, tenderness, swell- examined in each stratification level, the

rates were 3% (95% confidence interval

medical testing

ing, warmth, or discoloration in the Physical therapists should recom-

lower extremity. (Evidence Quality: [CI]⫽1.7%, 5.9%), 16.6% (95% CI⫽12%,

mend further medical testing after

II; Recommendation Strength: B– 23%), and 74.6% (95% CI⫽63%, 84%) for

the completion of the Wells criteria

Moderate) low, moderate, and high risk, respec-

for LE DVT prior to mobilization

tively. Other studies have shown a clear

(Evidence quality: I; Recommenda-

distinction in the rate of LE DVT among

Action statement profile tion strength: A–Strong)

the 3 risk stratification levels.62,65 A 2014

Aggregate Evidence Quality: Level II

systematic review showed that, as the

Benefit: Early intervention and preven-

score on the Wells criteria increased, so

tion of adverse effects of LE DVT

did the likelihood of an LE DVT.66 This

Risk, Harm, Cost: None

February 2016 Volume 96 Number 2 Physical Therapy f 153

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

Table 6. sound.26,31,44,63 Individuals in the DVT–

Two-Level Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) Wells Criteria Scorea likely category will test positive on the

D-dimer test, so the D-dimer test has lit-

Clinical Feature Points

tle value. If the ultrasound is negative,

Active cancer (treatment ongoing, within 6 mo, or palliative) 1 the physical therapist should consider

Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization of the lower extremities 1 the patient safe to mobilize. If the ultra-

Recently bedridden for 3 d or longer or major surgery within 12 wk 1

sound is positive, the physical therapist

requiring general or regional anesthesia should defer mobility until medical treat-

ment has achieved therapeutic levels.

Localized tenderness along the distribution of the deep venous system 1

Entire leg swollen 1 In summary, the results of the Wells cri-

Calf swelling at least 3 cm larger than asymptomatic side 1 teria for LE DVT should guide the selec-

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

Pitting edema confined to the symptomatic leg 1

tion of medical testing. Following the

results of the medical testing, the physi-

Collateral superficial veins (nonvaricose) 1

cal therapist can then make a decision

Previously documented DVT 1 about when it is safe to mobilize the

Alternative diagnosis at least as likely as DVT ⫺2 patient.

Clinical probability simplified score

Action Statement 7: Verify the

DVT likely 2 points or more

patient is taking an

DVT unlikely Less than 2 points anticoagulant

a

Reprinted from Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, et al. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of When a patient has a recently

suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1227–1235. © 2003 Massachusetts Medical diagnosed LE DVT, the physical ther-

Society. Reprinted with permission from the Massachusetts Medical Society.

apist should verify whether the

patient is taking an anticoagulant

medication, what type of anticoagu-

Action statement profile with an LE DVT– unlikely classification

lant medication, and when the

Aggregate Evidence Quality: Level I and a negative D-dimer test, fewer than

anticoagulant medication was

Benefit: Risk stratification can ensure 1% have an LE DVT, and studies report

initiated. (Evidence Quality: V;

proper diagnostic testing is completed sensitivity in the upper 90% to 100%.71–73

Recommendation Strength: D–

Risk, Harm, Cost: None These patients need no further testing

Theoretical/Foundational)

Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponder- and can be considered safe to

ance of benefit over harm mobilize.26,31,36,43,70

Action statement profile

Value Judgments: None

Aggregate Evidence Quality: Level V

Intentional Vagueness: None Although the D-dimer test has high sen-

Benefit: Decreased risk of a PE in

Role of Patient Preferences: None sitivity, it has poor specificity. A positive

patients who are adequately anticoagu-

Exclusions: None D-dimer test does not indicate a definite

lated

LE DVT. A range of conditions, such as

Risk, Harm, Cost: Risk of bleeding with

Summary of evidence older age, infections, burns, and heart

anticoagulation, risk of adverse effects

Once the Wells criteria for LE DVT are failure, can lead to an elevated D-dimer

with restrictions in inactivity, and cost of

complete, medical testing can be test, and hospitalized individuals have a

new anticoagulants may be prohibitive

ordered by the medical team to diagnose high rate of false positives when the

in those with inadequate pharmacy

or rule out an LE DVT. The selection of D-dimer is used for a suspected LE

insurance coverage.

which medical test is beyond the scope DVT.74 When a patient who is LE DVT–

Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponder-

of physical therapist practice, but there unlikely has a positive or high D-dimer

ance of benefit over harm

is benefit in understanding why tests are level, further testing is necessary. Most

Value Judgments: Intentional vague-

selected and how results guide the diag- guidelines recommend a duplex ultra-

ness. This CPG has provided therapeutic

nostic process. If a patient is classified as sound to confirm an LE DVT.26,43,44,63

ranges for anticoagulants that have been

unlikely to have an LE DVT, the over- There is some debate on the type of

provided by the manufacturers due to

whelming recommendation is for the ultrasound that is ordered, but this factor

the limited evidence beyond this.

medical team to order a D-dimer test is beyond the focus of these guidelines. If

Although the recommendation strength

over other more costly and invasive the ultrasound confirms an LE DVT, med-

is weak based on scientific evidence, the

tools.26,31,43,44,70 Within the referenced ical treatment should be initiated and

GDG considers it prudent to follow the

CPGs, the evidence is rated as level I, mobilization postponed. If the ultra-

manufacturer’s recommendations.

with grade of A to B for the recommen- sound is negative, the patient is safe to

Role of Patient Preference: Patients

dation. The D-dimer test is a measure of mobilize.

should be informed of the importance

the breakdown or degradation of cross-

for continuing anticoagulation upon dis-

linked fibrin, which increases in the A patient rated as LE DVT–likely should

charge from the hospital as different anti-

presence of a thrombosis. In patients immediately undergo a duplex ultra-

154 f Physical Therapy Volume 96 Number 2 February 2016

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

coagulants require monitoring, cost, and play a role in recommending the antico- been reported when LMWH is used in

modification of diet and bleeding risk. agulant of choice, they should identify patients with renal insufficiency and

Exclusions: None which anticoagulant the patient has been other populations. Therefore, precau-

prescribed and date and time of the first tions for bruising and bleeding with

Summary of evidence dose. This approach will assist the phys- physical therapy interventions should be

Anticoagulants are the primary defense ical therapist in determining when the taken when LMWH is used in patients

used to prevent and treat an LE DVT and patient has reached a therapeutic dose, with kidney injury or dysfunction,

consequent PE or PTS. Contrary to pop- and consequently, when mobility may be patients in extreme weight ranges,

ular belief, anticoagulants do not actively initiated safely. patients who are pregnant, and neonates

dissolve a blood clot but instead prevent and infants.63

new clots from forming. Although anti- The current options for anticoagulation

coagulants are often referred to as blood include UFH, LMWH, Coumadin (Bristol- Unfractionated heparin is indicated for

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

thinners, they do not actually thin the Myers Squibb, New York, New York) individuals with high bleeding risk

blood. This class of drugs works by alter- (warfarin), fondaparinux, and oral (eTable) or renal disease. Patients with

ing certain chemicals in the blood nec- thrombin or Xa inhibitors (eTable, avail- established or severe renal impairment

essary for clotting to occur. Conse- able at ptjournal.apta.org). Most patients are defined as those with an estimated

quently, blood clots are less likely to with a confirmed diagnosis of LE DVT or glomerular filtration rate of less than 30

form in the veins or arteries, and yet PE are prescribed a form of LMWH or mL/min/1.73 m2. Unfractionated heparin

continue to form where needed. fondaparinux (both given with subcuta- is often prescribed and dosed to achieve

Although anticoagulants do not break neous injections).31,44,61 Low-molecular- therapeutic levels quickly. Lower speeds

down clots that have already formed, weight heparin is principally used to of infusion are usually given in acute cor-

they do allow the body’s natural clot lysis treat any LE DVT below the knee, at onary syndromes, whereas higher speeds

mechanisms to work normally to break thigh level, and more proximal of infusion are given with VTE. Several

down clots that have formed. thrombi.31 It is the anticoagulant of institutions have transitioned from mon-

choice for pregnancy and for active can- itoring heparin with anti-factor Xa levels

Once an LE DVT is diagnosed, anticoag- cer and the primary choice of physicians instead of activated partial thromboplas-

ulant therapy is initiated, most com- for treatment of VTE in the outpatient or tin time (aPTT) due to influencing factors

monly with LMWH. Anticoagulant ther- home setting due to ease of use and low that can alter aPTT levels.83 One study

apy will help to stop an existing clot incidence of side effects.31,43,61 Low- has shown anti-Xa detects therapeutic

from getting larger and prevent any new molecular-weight heparin is used in most levels faster than aPTT (patients with

clots from forming. In addition, LMWH cases except when a patient has renal UFH achieved therapeutic anticoagula-

has been shown to stabilize an existing dysfunction or a creatinine clearance less tion in approximately 24 hours com-

clot and resolve symptoms through the than 30 mL/min. Concomitant Coumadin pared with patients monitored with

drug’s anti-inflammatory properties, use may be started and provided for 3 aPTT, which averaged 48 hours).83

making a clot less likely to migrate as an days, with subsequent international nor- Patients with a documented PE, includ-

embolus. malized ratio (INR) values being deter- ing those who are hemodynamically

mined. Most individuals will continue unstable, are often prescribed UFH, and

A patient diagnosed with an LE DVT is at with their initial anticoagulant (LMWH or similar aPTT monitoring should be

risk of developing a PE; therefore, mobil- fondaparinux) for 3 to 6 months for the reviewed by the physical therapist see-

ity is contraindicated until intervention is first episode of diagnosed thrombosis. If ing the patient.44

initiated to reduce the chance of emboli Coumadin is given concomitantly, they

traveling to the lungs.75–79 According to will likely be removed from the initial Coumadin is usually not the first medica-

the ACCP guidelines on antithrombotic anticoagulant and continued on Couma- tion choice for anticoagulation due to

therapy, anticoagulation is the main din for 3 to 6 months.44,80 the length of time to achieve peak ther-

intervention and should be initiated as apeutic levels. Coumadin is typically

soon as possible (level I, strong evi- Anti-Xa levels can be used to monitor introduced on day 1 during administra-

dence).26,43,44,61 If the patient is at a high LMWH. However, evidence does not tion of another anticoagulation, usually

risk for bleeding, the primary contraindi- support the use of anti-Xa assay levels for with LMWH or UFH.61 The loading anti-

cation to anticoagulation, then medica- predicting thrombosis and bleeding coagulant (LMWH or UFH) is continued

tions may not be prescribed. Therefore, risk.81 Pharmacokinetic studies on for at least 5 days until an INR greater

prior to initiating mobility out of bed, a LMWH report that maximum anti-factor than 2.0 is achieved for at least 24 hours,

physical therapist should review all med- Xa and antithrombin IIa activities occur 3 prior to discontinuing the loading antico-

ications the patient has been prescribed to 5 hours after subcutaneous injection agulant, and first episodes of VTE should

and verify that the patient is taking an of LMWH.82 The optimal therapeutic be treated with a target INR range of

anticoagulant. The physical therapist anti-Xa levels for treatment are 0.5 to 1.0 2.5.80 The UFH or LMWH is often discon-

should next consult with the medical U/mL. Due to the fact that LMWH is tinued when the INR is greater than

team regarding appropriateness of mobil- excreted primarily by the kidneys, 2.0.61

ity. Although physical therapists do not increased bleeding complications have

February 2016 Volume 96 Number 2 Physical Therapy f 155

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

Fondaparinux (Arixtra, GlaxoSmith- ing patient safety. When the INR is hours; thrombocytopenia (platelet count

Kline, Research Triangle Park, North Car- greater than 6.0, the medical team less than 7,500); uncontrolled systolic

olina) is similar to LMWH, is monitored should consider bed rest until the INR is hypertension (defined as blood pressure

using anti-Xa assays, and is often used corrected.85,86 In most cases, INRs can of 230/120 mm Hg or higher), and

when individuals need treatment or pro- be corrected within 2 days.85 When untreated inherited bleeding disorders,

phylaxis for VTE but have a history of reversal of anticoagulation is needed for such as hemophilia or von Willebrand

HIT.43 The maximal therapeutic dosage surgery and the patient is taking Couma- disease.20

is reached in approximately 2 to 3 din, fresh frozen plasma is the choice to

hours.43,79 Fondaparinux also is used for replace the anticoagulation.86 Action Statement 8: Mobilize

thromboprophylaxis in patients with patients who are at a therapeutic

medical and surgical conditions, as is New oral anticoagulant drugs (direct level of anticoagulation

LMWH.63 thrombin inhibitors and direct factor Xa

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

When a patient has a recently diag-

inhibitors) are growing in popularity due nosed LE DVT, physical therapists

Both UFH and LMWH are associated with to their ease of use (no laboratory mon- should initiate mobilization when

HIT, defined as an immune-mediated itoring, no adverse dietary or other drug therapeutic threshold levels of anti-

reaction to heparins. Heparin-induced interactions) and their rapid time to peak coagulants have been reached. (Evi-

thrombocytopenia can occur in 2% to 3% therapeutic levels. In addition, there dence Quality: I; Recommendation

of patients treated with UFH and in appears to be less risk of cerebral hem- Strength: A–Strong)

approximately 1% of patients treated orrhage, as occurs in vitamin K antago-

with LMWH.43 Heparin-induced throm- nists.86 Rivaroxaban (Xarelto, Janssen Action statement profile

bocytopenia will result in a paradoxical Pharmaceuticals Inc, Titusville, New Jer- Aggregate Evidence Quality: Level I

increased risk for venous and arterial sey), dabigatran (Pradaxa, Boehringer Benefit: Decreased risk of subsequent

thrombosis, and this risk lasts approxi- Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc, Ridge- LE DVT or PE; decreased risk of adverse

mately for 100 days following initial reac- field, Connecticut), and apixaban effects of bed rest

tion. Therefore, patients with a history of (Eliquis, Bristol-Myers Squibb Co) are the Risk, Harm, Cost: Risks associated with

HIT should not receive either LMWH or 3 new oral anticoagulant drugs in use at use of anticoagulants include increased

UFH with subsequent VTE.43,84 Treat- this time (refer to eTable for dosage, risk of bleeding. If an anticoagulant is not

ment for anticoagulation in individuals method of delivery, and peak at a therapeutic level, there may be an

with HIT involves using fondaparinux or therapeutic-level time frames). The new increased risk of PE with mobilization.

other thrombin-specific inhibitors such oral anticoagulant drugs are recom- Benefit-Harm Assessment: Preponder-

as lepirudin or argatroban. Indicators of mended by the American Academy of ance of benefit

HIT are: skin lesion reaction at injection Orthopaedic Surgeons for hip and knee Value Judgments: The evidence for

site, systemic reaction to a bolus admin- arthroplasty but have not been tested or mobility to prevent VTE is strong,

istration of heparin, and 50% decrease in recommended for individuals who have although the evidence on when to initi-

platelet count from normal ranges while cancer, are undergoing treatment for ate mobility may not be as strong and is

on heparin. Indicators of delayed-onset cancer, or are pregnant.89 There are con- based on the patient achieving the ther-

HIT are: thromboembolic complications cerns regarding reversal of anticoagula- apeutic level of the anticoagulant. Phys-

1 to 2 weeks after receiving the last dose tion with these medications. However, ical therapists should mobilize patients

of LMWH or UFH, and mild-to-moderate reconstructed recombinant factor Xa or as soon as possible after diagnosis of VTE

thrombocytopenia. activated charcoal have both been pro- as long as the risk of PE is decreased.

posed as antidotes.89,90 The time for Achieving the therapeutic level of the

Mobility decisions with an individual reversal is the amount of time to elimi- anticoagulant has been shown to dimin-

receiving Coumadin are based on the ini- nate the drug from the body, which is ish the risk of developing a PE.

tial anticoagulant and not Coumadin. based on the drug’s half-life, usually Intentional Vagueness: Specific antico-

Concern regarding exercise and out-of- within 12 to 24 hours. With all anticoag- agulants or their therapeutic levels are

bed activity should be raised for elevated ulants there is a risk of bleeding. There- not recommended. Instead, evidence-

INRs greater than 4.0 when patients are fore, in addition to the risk of VTE, phys- based guidelines and algorithms have

taking warfarin.85 If the INR is between ical therapists should be aware of and been provided for guidance. Physical

4.0 and 5.0, resistive exercises should be assess for risk of bleeding in all patients. therapists should work within their

avoided, with participation in light exer- Factors associated with high risk of health care system to develop institution-

cise only (eg, rating of perceived exer- bleeding are: active bleeding; acute specific protocols.

tion ⱕ11) due to increased risk of bleed- stroke; acquired bleeding disorders (eg, Role of Patient Preference: Patients

ing.85 Ambulation should be restricted if acute liver failure); concurrent use of should be aware of the anticoagulation

gait is unsteady to prevent falls.85 The anticoagulants known to increase the they are prescribed and the effect that

likelihood of bleeding rises steeply as risk of bleeding (eg, Coumadin with an the anticoagulant will have on their life-

INR increases above 5.0.86 – 88 If the INR international normalized ratio ⬎2); lum- style (eg, amount of medical monitoring,

is greater than 5.0, discussion should be bar puncture, epidural, or spinal anesthe- risk of bleeding, foods to avoid, risk of

held with the referring physician regard- sia expected to be given within next 12 brain bleed). In addition, patients should

156 f Physical Therapy Volume 96 Number 2 February 2016

Management of Individuals With Venous Thromboembolism

be informed regarding the risk of immo- because of the potential to decrease PTS Summary of evidence

bility in developing further VTE and the and improve quality of life.27 In the ninth edition (2012) CPG by the

benefit of mobility. ACCP, recommendations pertaining to

Exclusions: The risk of bleeding is pres- In summary, early mobilization of mechanical compression based on

ent when anyone takes anticoagulants. patients with an LE DVT who are antico- moderate-quality data for patients with

However, patients with HIT, a history of agulated does not put the patient at diagnosed LE DVT were given.91 For

HIT, recent bleeding events, or increased increased risk of PE. Early mobilization patients with acute symptomatic LE DVT

risk of bleeding should be prescribed has added benefits. The GDG recom- and in those having PTS, GCS were sug-

treatment other than anticoagulation, mends mobilizing patients with an LE gested based on studies using at least 30

including mechanical compression or DVT once anticoagulation is initiated and mm Hg of pressure at the ankle. In

intravenous filters. therapeutic levels have been achieved. patients with severe PTS of the leg not

Based on the evidence that exists on time adequately relieved with GCS, a trial with

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ptj/article-abstract/96/2/143/2686356 by guest on 15 June 2019

Summary of evidence to peak therapeutic levels of the antico- IPC was suggested.

Patients who have a documented LE DVT agulants (refer to eTable), expert consen-

and have reached therapeutic levels of sus exists to recommend early ambula- Systematic reviews pertaining to the

the prescribed anticoagulant should be tion of individuals with an LE DVT who adjuvant use of mechanical compression

mobilized out of bed and ambulate to are receiving anticoagulation and have garments for patients who are anticoag-

prevent venous stasis. In doing so, reached their peak therapeutic levels ulated and have acute VTE (eg, LE DVT)

deconditioning is minimized, length of based on the specific anticoagulation while on bed rest or with early ambula-

hospital stay may be shortened, and medication they are prescribed. tion compared with controls provide

other adverse effects of prolonged bed supportive evidence for their use.92 The

rest (eg, decubiti) can be avoided. A Action Statement 9: Recommend 7 RCTs in these reviews concluded that

common concern for mobilizing a mechanical compression for mechanical compression lowered the

patient with an LE DVT is that the clot patients with LE DVT relative risk for progression of a throm-

will dislodge and embolize to the lungs, Physical therapists should recom- bus or the development of a new

causing a potentially fatal PE. However, mend mechanical compression (eg, thrombus.

early ambulation has been shown to lead IPC, GCS) when a patient has an LE

to no greater risk of PE than bed rest for DVT. (Evidence Quality: II; Recom- Two earlier RCTs conducted over 2 years