Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 viewsScan00121 PDF

Scan00121 PDF

Uploaded by

udit raj singhCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- New Doc 2019-10-17 21.16.16Document4 pagesNew Doc 2019-10-17 21.16.16udit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Flattening of The Phillips Curve Implications For PDFDocument22 pagesFlattening of The Phillips Curve Implications For PDFudit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Ecode Marks-Fya 1. QUIZ / 40 Total Score AG QUIZ MarksDocument2 pagesEcode Marks-Fya 1. QUIZ / 40 Total Score AG QUIZ Marksudit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Macro Project PDFDocument8 pagesMacro Project PDFudit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Fashion Clothing Consumption Among NMIMS Students: 3.1 ToolDocument3 pagesFashion Clothing Consumption Among NMIMS Students: 3.1 Tooludit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Law Assignment Tort-Liability Udit Raj Singh, FYA Roll No. A050Document4 pagesLaw Assignment Tort-Liability Udit Raj Singh, FYA Roll No. A050udit raj singhNo ratings yet

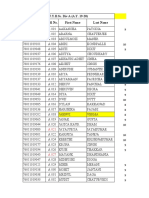

- F.Y.B.Sc. Div A (A.Y. 19-20) Roll No. First Name Last Name Student NumberDocument6 pagesF.Y.B.Sc. Div A (A.Y. 19-20) Roll No. First Name Last Name Student Numberudit raj singhNo ratings yet

Scan00121 PDF

Scan00121 PDF

Uploaded by

udit raj singh0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views23 pagesOriginal Title

scan00121.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views23 pagesScan00121 PDF

Scan00121 PDF

Uploaded by

udit raj singhCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 23

IMME e ecard

Agsregate Expenditure

and Equilibrium Output

the macroeconomy works. We

know how to calculate gross

domestic product (GDP), but what

factors determine it? We know how

to define and measure inflation ane

unemployment, but what circum

stances cause inflation and unem

ployment? What, if anything, can

government do to reduce unem

ployment and inflation?

‘Analyzing the various compo-

nents of the macroeconomy is a

complex undertaking, The level of

GDP, the overall price level, and

the level of employment—three

chief concerns of macroecono-

smists—are influenced by events in three broadly defined “markets”

= Goods-and-services markets

= Financial (money) markets

= Labor markets

We will explore each market, as well as the links between them, in our discussion of

‘macroeconomic theory. Figure 21.1 presents the plan of the next seven chapters, which form

the core of macroeconomic theory. In Chapters 21 and 22, we describe the market for goods

arket.In Chapter

show how the equilibrium level of national income is

government and no imports or exports. In Chapter 22, we provide a more complete picture of

the economy by adding government purchases, taxes, and net exports to the analysis.

In Chapters 23 and 24, we focus on the money market. Chapter 23 introduces the money

market and the banking system and discusses the way the US. central bank (the Federal Reserve

controls the money supply. Chapter 24 analyzes the demand for money and the way interes

rates are determined, Chapter 25 then examines the relationship between the goods market and

the money market. Chapter 26 explores the aggregate demand and supply curves first men.

tioned in Chapter 18, Chapter 26 also analyzes how the overall price level is determined, as well

asthe relationship between output and the price level. Finally, Chapter 27 discusses the supply of

and demand for labor and the functioning of the labor markerin the macroeconomy. This mate

rials essential to an understanding of employment and unemployment.

Before we begin our discussion of aggregate output and aggregate income, we need te

stress that production, consumption, and other activities that we will be discussing in the

‘we explain several basic concepts and

and services, often called the goods

‘mined in a simple economy with no

Chapter Outline

Aggrogate Output and

Aggregate Income (Y)

Equilibrium Aggregate

‘Output (Income)

The Saving/in

0 Equi

Adjustment to Equiitia

|

|r

Mulipier Equator

The Size ofthe Mutipi

The Mutipier in Action

Depres

Looking Ahead

‘Appondix: Deriving the

“Multiplier Algebraicaly

455

fiaicoe

Sissons

cuseren 26

—— aaa

Consumption (0) sTiaeaws Sant

Permedimestren () agente donand oe

Goverment (6) =

Nvspos (X— = caurronz7

+ Aggregate output

(income) (Y) Connections between —__¥ re ee ae

the gods maaan pggrgate supp cue «The supply of bor

7 > Site Semana abr

: Ss D coe

dairies 20 ae Senelomen

‘The Money Market + Eaulibiuminorest

rate (r')

He a1 of money + Equlorum ouput

‘+The demand for money (income) (¥*)

Titoes to eam pce

level (P*)

‘We build up the macroecanomy slowly. In Chapters 22. and 22 we examine the market for goods and services, and in Chapters 23 and 24

we examine the money market. Then in Chapter 25 we bring the two markets together, In so doing explaining the links between aggregate

‘output (7) and the interest rate (7). In Chapter 26 we explain how the aggregate demand curve can be derived from Chapters 22 through

25, and we introduce the aggregate supply curve. This sets the stage for an explanation ofthe price level (P). We then explain in Chapter

2 how the labor market fits into the macroeconomic picture.

following chapters are ongoing activities. Nonetheless, itis helpful to think about these activ-

they took place ina series of production periods. A period might be a month long or

pethaps 3 months long. During each period, some output is produced, income is generated,

and spending takes place. At the end of each period we can examine the results. Was every-

thing that was produced in the economy sold? What percentage of income was spent? What

percentage was saved? Is output (income) likely to rise r fallin the next period?

AGGREGATE OUTPUT AND AGGREGATE INCOME (Y)

Each period, firms produce some aggregate quantity of goods and services, which we refer to

as aggregate output (¥). In Chapter 19, we introduced real gross domestic product as a mea

sure of the quantity of output produced in the economy, ¥. Output includes the production

of services, consumer goods, and investment goods. Its important to think of these as com-

ponents of “real” output.

We have already seen that GDP (1) can be calculated in terms of either income or expendi-

tures. Because every dollar of expenditure is received by someone as income, we can compute

total GDP (¥) either by adding up the total spent on all final goods during period orby adding

‘roduced (oF supplied) in an upaall the income—wages, rents, interest, and profits—received by all the factors of production. |

‘canon in agen period. We will use the variable Y to refer to both aggregate output and aggregate income

adgregate income te because they are the same seen from two different points of view. When output increases,

{otal icome recived ty a additional income is generated. More workers may be hired and paid; workers may put in,

factors of production n'a gwen and be paid for, more hours; and owners may earn more profits. When output is cut, income

pet. falls, workers may be laid off or work fewer hours (and be paid less), and profits may fall.

aggregate output

(income) (¥) A sombines In any given period, there is an exact equality between aggregate output (production)

term used to remind you of the and aggregate income. You should be reminded of this fact whenever you encounter

exact equality between agzregate the combined term, % aces}

‘output and aggregate income. bon ined err neato utp (K .

456

Aggregate output can also be considered the aggregate quantity supplied, because itis the

amount that firms are supplying (producing) during the period. Inthe discussions that follow,

‘we use the phrase aggregate output (income), instead of aggregate quantity supplied, ut keep in

‘mind that the two are equivalent. Also remember that “aggregate output” means “real GDP”

Think in Real Terms From the outset you must think in “real terms” For example, when

we talk about output (¥), we mean real output, not nominal output. Although we discussed in

‘Chapter 19 thatthe calculation of real GDP is complicated, you can ignore these complications in

the following analysis. To help make things easier to read, we will frequently use doar values for

¥, but do not confuse ¥ with nominal output. The main point is to think of Y as being in real

terms—the quantities of goods and services produced, not the dollars circulating in the economy.

INCOME, CONSUMPTION, AND SAVING (Y, C, AND S)

Each period (a month or 3 months) households receive some aggregate amount of income

(1). We begin our analysis in a simple world with no government and a “closed” economy,

that is, no imports and no exports In such a world, a household can do two, and only two,

things with its income: Itcan buy goods and services—that is it can consume—or it can save.

This is shown in Figure 21.2. The part ofits income that a household does not consume in a

given period is called saving. Total household saving in the economy (S) is by definition

equal to income minus consumption (C):

saving = income ~ consumption

Se¥-c

‘The triple equal sign means this is an Identity, or something that is always true. You will

encounter several identities inthis chapter, which you should commit to memory.

Remember that saving does not refer to the total savings accumulated over time. Saving

(without the finals) r=fers to the portion of a single period’s income that is not spent in that

period. Saving (S) is the amount added to accumulated savingsin any given period. Saving is

a flow variable; savings is stock variable, (Review Chapter 3 if you are unsure of the differ-

ence between stock and flow variables.)

EXPLAINING SPENDING BEHAVIOR

So far, we have said nothing about behavior. We have not described the consumption and

saving behavior of households, and we have not speculated about how much aggregate out

pt firms will decide to produce in a given period. Instead, we have only a framework and a

set of definitions to work with.

“Macroeconomics, you will recall isthe study of behavior. To understand the functioning

of the macroeconomy, we must understand the behavior of households and firms. In our

Consumption (C)

‘saving (S)

Ser

Households

‘Aggregate meame (Y)

All income is either spent on consumption or saved in an economy in which there are no taxes. Thus,

S2¥-C. ei

cnaprer 21. 457

‘Agrees penta

and Eaulbrim Outpt

‘saving (S) The part of ts

income that a household does

‘ot consume in a given period

Distinguished trom savings.

\ihich i the curent stock of

‘ccumulated saving.

Identity Something that is

always te.

458 parry simple economy in which there is no government, there are two types of spending behavior:

‘The Goods and Money Markets. 3 - . e a a ui a

spending by households, or consumption, and spending by firms, or investment.

Household Consumption and Saving How do households decide how much to

consume? In any given period, the amount of aggregate consumption in the economy

depends on a number of factors

Some determinants of aggregate consumption include:

1. Household income

2. Household wealth

23. Interest rates

4. Households’ expectations about the future

‘These four factors work together to determine the spending and saving behavior of house

holds, both for individual ones and for the aggregate. This is no surprise. Households with

higher income and higher wealth are likely to spend more than households with less income

and less wealth. Lower interest rates reduce the cost of borrowing, so lower interest rates are

likely to stimulate spending. (Higher interes rates increase the cost of borrowing and are likely

to decrease spending.) Finally, positive expectations about the future are likely to increase cur-

rent spending, whereas uncertainty about the future is likely to decrease current spending.

All these factors are important, but we will concentrate for now on the relationship

between income and consumption.! In The General Theory, Keynes argued that the amount

of consumption undertaken by a household is directly related to its income:

‘The higher your income is, the higher your consumption is likely to be. People with

‘more income tend to consume more than people with less income.

The relationship between consumption and income is called a consumption function.

tener between Figure 21.3 shows a hypothetical consumption function for an individual household. The

Household consumption ()

-

Household income ()

‘A consumption funetion for an individual household shows the level of consumption at each level of

household income,

‘The assumption tha consumption i dependent soley on income of cous, ony splits: Nonethles, many important

‘insights bout how the economy works an be obtained though this smpliferion Ln Cher 29, we els his stmpton ot

onsider the behavior of households and fms in the macrocconomy in mote deta

re ee

curve is labeled cy), which is read “casa function of y” or “consumption as a function of

income.” There are several things you should notice about the curve. First, it has a positive

slope. In other words, as y increases, so does c. Second, the curve intersects the c-axis above

zero, This means that even at an income of zero, consumption is positive. Even if a house-

hold found itself with a zero income, it still must consume to survive. It would borrow or live

off its savings, but its consumption could not be zero.

Keep in mind that Figure 21.3 shows the relationship between consumption and income

for an individual household, but also remember that macroeconomics is concerned with

aggregate consumption. Specifically, macroeconomists want to know how aggregate con-

sumption (the total consumption of all households) is likely to respond to changes in

aggregate income. If all individual households increase their consumption as income

increases, and we assume that they do, itis reasonable to assume that a positive relationship

exists between aggregate consumption (C) and aggregate income (¥)

For simplicity, assume that points of aggregate consumption, when plotted against

aggregate income, lie along a straight lin, as in Figure 21.4. Because the aggregate consump.

tion function is a straight line, we can write the following equation to describe it

C=a+bY

Yiis aggregate output (income), C is aggregate consumption, and a is the point at which

the consumption function intersects the C-axis—a constant. The letter b is the slope of,

the line, in this case AC /AY [because consumption (C) is measured on the vertical axis,

and income (¥) is measured on the horizontal axis.’ Every time income increases (say

by AY), consumption increases by b times AY. Thus, AC = b x AY and AC/AY = b.

Suppose, for example, that the slope of the line in Figure 21.4 is .75 (that is, b= .75). An

increase in income (AY) of $100 would then increase consumption by BAY = .75 x $100,

or $75.

‘The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the fraction of a change in income

that is consumed. In the consumption function here, bis the MPC. An MPC of .75 means

consumption changes by .75 of the change in income. The slope of the consumption

function is the MPC.

consumption (C)

Ageregate income (¥)

‘The consumption function shows the level of consumption at every evel of income. The upward slope

Indicates that higher levels of income lead to higher levels of consumption spending,

he Gree eter (dela) means "change in” For ample AY (read “deka Y") meas the" changin income income (1) in

2004 $100 and income ln 208110 then AY for this period 10 $100» $10, ora eview ofthe concept af slope, se

‘Appendix Chae

cuapter 21 459.

‘Areas Expenditure

sd Elion Out

marginal propensity

to consume (MPC) That

fraction of a change in income

‘that's consumed, or spent.

marginal propensity to

‘save (MPS) That traction of 2

change in income that's saved

‘There are only two places income can go: consumption or saving. If $0.75 of a $1.00

increase in income goes to consumption, $0.25 must go to saving. If income decreases by

$1.00, consumption will decrease by $0.75 and saving will decrease by $0.25. The marginal

propensity to save (MPS) is the fraction of a change in income that is saved: ASIAY, where

Sis the change in saving. Because everything not consumed is saved, the MPCand the MPS

must add up to 1

‘MPC+ MPS=1

Because the MPC and the MPS are important concepts, it may help to review their

definitions.

‘The marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the fraction of an increase in income

that is consumed (or the fraction of a decrease in income that comes out of consump-

61 eee eee fractioii of fn increase in income

"tht is Saved (or the fraction of a decteasein income that comes out of saving).

Because C is aggregate consumption and Y's aggregate income, it follows that the MPC is,

society's marginal propensity to consume out of national income and that the MPS is society's

‘marginal propensity to save out of national income,

Numerical Example The numerical examples used in the rest of this chapter are

based on the following consumption function:

00+ 25x

tb

‘This equation is simply an extension of the generic C= a + bY consumption function we

have been discussing. At a national income of zero, consumption is $100 billion (a). As

income rises, so does consumption. We will assume that for every $100 billion increase in,

income (AY), consumption rises by $75 billion (AC). This means that the slope of the

consumption function (b) is equal to ACIAY, or $75 billion/$100 billion = .75. The mar-

ginal propensity to consume out of national income is therefore .75; the marginal

propensity to save is .25. Some numbers derived from this consumption function are

listed and graphed in Figure 21.5.

Now consider saving, We already know Y= C+ S, income equals consumption plus sa

ing. Once we know how much consumption will result from a given level of income, we

know how much saving there will be. Recall that saving is everything that is not consumed.

eG

From the numbers in Figure 21.5, we can easily derive the saving schedule that is shown. Atan

income of $200 billion, consumption is $250 billion; saving is thus a negative $50 billion

(Ss ¥- C= $200 billion - $250 billion = -$50 billion). At an aggregate income of $400 billion,

consumption is exactly $400 billion, and saving is zero. At $800 billion in income, saving isa

positive $100 billion.

‘The consumption and saving functions we have been discussing are shown in

Figure 21.6. To analyze their relationship, we will use the device of the 45° line as a way of

comparing C and Y. The 45° line—the solid black line in the top graph—shows all the

points at which the value on the horizontal axis equals the value on the vertical axis.

‘Thus, the 45° line in Figure 21.6 represents all the points at which aggregate income equals

aggregate consumption.) Where the consumption function is above the 45° line, con

sumption exceeds income, and saving is negative. Where the consumption function

cnarrer 21 461

‘Aegegte Expendre

00 | daub Outpt

00 }

ony

1o0+.75¥

eee

om ano son to sto eo 70000 oD 100

Aggregate income, ¥(billons of dollars)

AGGREGATE INCOME, Y AGGREGATE CONSUMPTION, ¢

LIONS OF DOLLARS) (BILLIONS OF DOLLARS)

100

160

15

250

400

150

700

850

In this simple consumption function, consumption is $100 biion at an income of zero, As income

rises, so does consumption. For every $100 billn increase in income, consumption rises by $75 bit

lian, The slope ofthe line is .75.

crosses the 45° line, consumption is equal to income, and saving is zero. Where the con-

sumption function is below the 45° line, consumption is less than income, and saving is

positive. Note that the slope of the saving function is AS/AY, which is equal to the mar:

ginal propensity to save (MPS).

‘The consumption function and the saving function are mirror images of one another

No information appears in one that does not also appear in the other. These functions

tell us how households in the aggregate will divide income between consumption

spending and saving at every possible income level. In other words, they embody

aggregate houschold behavior.

PLANNED INVESTMENT (1)

Consumption, as we have seen, is the spending by households on goods and services, but

what kind of spending do firms engage in? The answer is investment.

What Is Investment? Let us begin with a brief review of terms and concepts. In

everyday language, we use investment to refer to what we do with our savings: “I invested in a

mutual fund and some AOL stock.” In the language of economics, however, investment

462 party

‘The Goode and Money Marat

Aggregate income, ¥(hilions of dors)

. c : s

Acgrecare ‘AGGREGATE

‘CONSUMPTION ‘SAVING

LIONS OF DOLLARS) (BILLIONS OF DOLLAR:

| 100 =100|

160 80

‘Because S = Y~ G tis easy to derive a saving function from a consumption function. A 45° line drawn

{fom the origin can be used as a corwenient too to compare consumption and income graphically At

Y= 200, consumption is 250. The 45" ine shows us that consumption Is lager than income by 60. Thus

'S=¥—C=-50. At Y= 800, consumption isles than income by 100. Thus, S

always refers to the creation of capital stock. To an economist, an investment is something

produced that is used to create value in the future.

‘You must not confuse the two uses of the term. When a firm builds a new plant or adds

new machinery to its current stock, itis investing. A restaurant owner who buys tables,

chairs, cooking equipment, and silverware is investing. When a college builds a new sports

nt Pscas centr its investing, rom now on, ve use Investment only to refer to purchases by firms of

sre scyaget® 2m ew buildings and equipment and inventories, all of which add to frm capital stocks

oowacmen Recall hat inventories are par of the capital stock. When ims add to their inventories,

tis cata soc they are investing—they are buying something that creates value in the future. Most ofthe

Investment Purchases by

capital stock of a clothing store consist of its inventories of unsold clothes in its warehouses

and on its racks and display shelves. The service provided by a supermarket or department

store is the convenience of having a large variety of commodities in inventory available for

purchase ata single location,

‘Manufacturing firms generally have two kinds of inventories: mputs and final products

General Motors (GM) has stocks of tires, rolled steel, engine blocks, valve covers, and thou-

sands of other things in inventory, all waiting to be used in producing new cars. In addition,

GM has an inventory of finished automobiles awaiting shipment.

Investment isa flow variable—it represents additions to capital stock in a specific period

A firm's decision on how much to invest each period is determined by many factors. For now.

‘we will focus simply on the effects that given investment levels have on the

st of the economy.

Actual versus Planned Investment One of the most important insights of macro

economics is deceptively simple: A firm may not always end up investing the exact amount

that it planned to. The reason is that a firm does not have complete control over its investment

decision; some parts of that decision are made by other actors in the economy. (This is not

true of consumption, however. Because we assume households have complete control over

their consumption, planned consumption is always equal to actual consumption.)

Generally, firms can choose how much new plant and equipment they wish to purchase

in any given period. If GM wants to buy anew robot to stamp fenders or McDonald’ decides

to buy an extra french fry machine, it can usually do so without difficulty. There is, however,

another component of investment over which firms have less control—inventory investment.

Suppose GM expects to sell 1 million cars this quarter and has inventories ata level it

considers proper. Ifthe company produces and sells 1 million cars, it wll keep its inventories

just where they are now (at the desired level). Now suppose GM produces I million cars, but

due to a sudden shift of consumer interest it sells only 900,000 cars. By definition, GM’s

inventories of cars must go up by 100,000 cars. The firm's change in inventory is equal to

production minus sales. The point here is:

‘One component of investment—inventory change—is partly determined by how much

households decide to buy, which is not under the complete control of firms. If households

do not buy as much as firms expect them to, inventories willbe higher than expected, and

firms will have made an inventory investment that they did not plan to make.

Because involuntary inventory adjustments are neither desired nor planned, we need to

distinguish between actual investment and desired, or planned, investment. We will use Ito

refer to desired or planned investment only. In other words, Iwill refer to planned purchases

of plant and equipment and planned inventory changes. Actual investment, in contrast, is

the actual amount of investment that takes place. If actual inventory investment turns out to

be higher than firms planned, then actual investment is greater than J, planned investment.

For the purposes of this chapter, we will ake the amount of investment that firms together

plan to make each period (/) as fixed at some given level, We assuume this level does not vary

with income. In the example that follows, we will assume that I= $25 billion, regardless of

income. As Figure 21.7 shows, this means the planned investment function isa horizontal line.

PLANNED AGGREGATE EXPENDITURE (AE)

We define total planned aggregate expenditure (AE) in the economy to be consumption

(©) plus planned investment (I.

planned aggregate expenditure = consumption + planned investment

AE=C+I

“tn practic, plnned aggre esenie ao ncads government spending (@) and net exports (EXIM: AB C+ 1+ G

“F(X IND nhs caper af sing that Gand (EX I ate eo, This sung ean inthe ex chapter

cnapren2s 463

‘asso

and eal Output

change in inventory

Production mieus sales.

te-captal stock and inventory

‘that ae planned by tes.

actual Investment Te

takes place: it includes tems

‘ch 8 unplanned changes in

planned aggregate

expenditure (AE) The toa!

‘amount the economy plans to

spend in a given period. Equal to

consumation plus planned

Investment: AE = C+

464 party

The Gonds and Money Marts

equilibrium Occurs when

there is no tendency for change

Inthe macroeconomic goods

‘market equim occurs when

planned aggregate expenditure is

leaual to aggregate outout

Aggregite income, ¥ (billions of las)

For the time boing, we will assume that planned investment is fixed. It does not change when income

changes, s0 its graph Is a horizontal line

Bis the total amount that the economy plans to spend in a given period. We will now use

the concept of planned aggregate expenditure to discuss the economy's equilibrium level

of output.

EQUILIBRIUM AGGREGATE OUTPUT (INCOME)

Thus far, we have described the behavior of firms and households. We now discuss the

nature of equilibrium and explain how the economy achieves equilibrium.

‘A number of definitions of equilibrium are used in economics. They all refer to the idea

that at equilibrium, there is no tendency for change. In microeconomics, equilibrium is said

to exist in a particular market (for example, the market for bananas) at the price for which

the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied. At this point, both suppliers and

demanders are satisfied. The equilibrium price of a good is the price at which suppliers want

to furnish the amount that demanders want to buy.

In macroeconomics, we define equilibrium in the goods market as that point at which

planned aggregate expenditure is equal to aggregate output.

aggregate output = ¥

‘planned aggregate expenditure = AE =

equilibrium: ¥ = AE, or ¥ =C+1

40

Note that the equilibrium condition is not an identity.

This definition of equilibrium can hold if, and only if, planned investment and actual

investment are equal. (Remember, we are assuming there is no unplanned consumption.) To

understand why, consider Y not equal to AE. First, suppose aggregate output is greater than

planned aggregate expenditure:

y>c4l

aggregate output > planned aggregate expenditure

‘When output is greater than planned spending, there is unplanned inventory investment

Firms planned to sell more oftheir goods than they sold, and the difference shows up as an

unplanned increase in inventories.

‘Next, suppose planned aggregate expenditure is greater than aggregate output:

CHI>Y

planned aggregate expenditure > aggregate output

@

@

ulate np hen

agnesare sactoare vest

our agoneoare exrtnTURE AE ‘Seaver

(NcOME}on —__CONSUMPHION ( wor een

10 5 200 |

» | 20 | 2

oo | io | 2

= os | | +00 | °

= | 0 | | es | a

= | ito | ms te

1.000 850 | ! 815 1125

‘When planned spending exceeds output, firms have sold more than they planned to,

Inventory investment is smaller than planned. Planned and actual investment are not equal

Only when output is exactly matched by planned spending will there be no unplanned inven:

tory investment. If there is unplanned inventory investment, this will be a state of disequilib-

rium, The mechanism by which the economy returns to equilibrium will be discussed later.

Equilibrium in the goods market is achieved only when aggregate output (¥) and planned

aggregate expenditure (C+ 1) are equal, or when actual and planned investment are equal.

‘Table 21.1 derives a planned aggregate expenditure schedule and shows the point of equi

librium for our numerical example. (Remember, all our calculations are based on C= 100 +

75Y.) To determine planned aggregate expenditure, we add consumption spending (C) to

planned investment spending (1) at every level of income. Glancing down columns I and 4,

‘we see one, and only one, level at which aggregate output and planned aggregate expenditure

are equal: Y= 500.

igure 21.8 illustrates the same equilibrium graphically. Figure 21.8(a) adds planned.

investment, constant at $25 billion, to consumption at every level of income. Because

planned investment is a constant, the planned aggregate expenditure function is simply the

consumption function displaced vertically by that constant amount. Figure 21,8(b) plots the

planned aggregate expenditure function with the 45° line. The 45° line represents all points

‘on the graph where the variables on the horizontal and vertical axes are equal. Any point on

the 45° line is a potential equilibrium point. The planned aggregate expenditure function

crosses the 45° line at a single point, where Y = $500 billion. (The point at which the two

lines cross is sometimes called the Keynesian cross.) At that point, Y= C+ I.

"Now let us look at some other levels of aggregate output (income). First, consider Y = $800

billion. Is this an equilibrium output? Clearly itis not. At Y= $800 billion, planned aggregate

expenditure is $725 billion. (See Table 21.1.) This amount i less than aggregate output, which is

‘$809 billion. Because output is greater than planned spending, the difference ends up in inventory

as unplanned inventory investment. In this case, unplanned inventory investment is $75 billion.

Next, consider Y= $200 billion. Is this an equilibrium output? No. At ¥= $200 billion,

planned aggregate expenditure is $275 billion. Planned spending (AE) is greater than output

(1), and there is unplanned inventory disinvestment of $75 billion.

At Y= $200 billion and Y= $800 billion, planned investment and actual investment are

unequal. There is unplanned investment, and the system is out of balance. Only at ¥ = $500

billion, where planned aggregate expenditure and aggregate output are equal, will planned

investment equal actual investment.

Finally, let us find the equilibrium level of output (income) algebraically. Recall that we

know the following:

wy

(2)C=100+.75Y (consumption function)

c+ (equilbrium)

@)1=25 (planned investment)

EQUILIBRH

(= Ae?)

uM?

Planned ageregate

expenditure:

z planned

ik inventor

5 cotpat ae

b

é

a

:

é

Aggregate output, ¥

(billions of dollars)

Equilibrium occurs when planned aggregate expenditure and aggregate output are equal. Planned

‘aggregate expenditure is the sum of consumption spending and planned investment spending.

By substituting (2) and (3) into (1), we get:

y

00 +.75Y, +25,

Cat

‘There is only one value of ¥ for which this statement is true, and we can find it by rearrang-

ing terms:

¥ ~75Y = 100+ 25

Y= 75 = 125

23¥ = 125

125. so

25

‘The equilibrium level of output is 500, as seen in Table 21.1 and Figure 21.8

a @

pane

a —

meh con cy

- ve 1

= = |

= | |

wo | 0 | |

1,000 I 850, 1 1

When planned spending exceeds output, firms have sold more than they planned to.

Inventory investment is smaller than planned. Planned and actual investment are not equal

‘Only when output is exactly matched by planned spending will there be no unplanned inven

tory investment. If there is unplanned inventory investment, this will be a state of disequilib-

rium, The mechanism by which the economy returns to equilibrium will be discussed later.

Equilibrium in the goods market is achieved only when aggregate output (¥) and planned

aggregate expenditure (C+ 1) are equal, or when actual and planned investment are equal.

Table 21.1 derives planned aggregate expenditure schedule and shows the point of equi

librium for our numerical example. (Remember, all our calculations are based on C= 100 +

75Y.) To determine planned aggregate expenditure, we add consumption spending (C) to

planned investment spending (J) at every level of income. Glancing down columns 1 and 4,

‘we see one, and only one, level at which aggregate output and planned aggregate expenditure

are equal: ¥ = 500.

Figure 21.8 illustrates the same equilibrium graphically. Figure 21.8(a) adds planned.

investment, constant at $25 billion, to consumption at every level of income. Because

planned investment is a constant, the planned aggregate expenditure function is simply the

consumption function displaced vertically by that constant amount. Figure 21.8(b) plots the

planned aggregate expenditure function with the 45° lin. The 45° line represents all points

on the graph where the variables on the horizontal and vertical axes are equal. Any point on

the 45° line is a potential equilibrium point. The planned aggregate expenditure function

crosses the 45° line at a single point, where Y= $500 billion. (The point at which the two

lines cross is sometimes called the Keynesian cross.) At that point, Y= C+ I.

‘Now let us look at some other levels of aggregate output (income). First, consider Y= $800

billion. Is this an equilibrium output? Clearly itis not. At ¥ = $800 billion, planned aggregate

expenditure is $725 billion. (See Table 21.1.) This amount is ess than aggregate output, which is

{$800 billion. Because output is greater than planned spending, the difference ends up in inventory

as unplanned inventory investment. In this case, unplanned inventory investment is $75 billion.

Next, consider Y= $200 billion. Is this an equilibrium output? No. At ¥= $200 billion,

planned aggregate expenditure is $275 billion. Planned spending (AE) is greater than output

(¥), and there is unplanned inventory disinvestment of $75 billion.

‘At Y= $200 billion and Y= $800 billion, planned investment and actual investment are

unequal. There is unplanned investment, and the system is out of balance. Only at ¥ = $500

billion, where planned aggregate expenditure and aggregate output are equal, will planned

investment equal actual investment.

Finally, let us find the equilibrium level of output (income) algebraically. Recall that we

know the following

wy=ce+r (cquilbrium)

(2) =100+.75Y (consumption function)

@)1=25 (planned investment)

EQUILIBRIUM?

(y= Ae?)

No

No

wo} cu

Planned aguezate

‘capediar

i, Unplanned

e =

g:

22 ns

Aggregate output, ¥

(Glions of dali)

Equilibrium occurs when planned aggregate expenditure and aggregate output are equal. Planned

aggregate expenditure isthe sum of consumption spending and planned investment spending.

‘By substituting (2) and (3) into (1), we get:

y

(00 +.75Y +25,

E47

‘There is only one value of ¥for which this statement is true, and we can find it by rearrang:

ing terms:

Y ~.75Y = 100-425

Y ~.75Y = 125

25Y = 125

125

25

500

The equilibrium level of output is 500, as sen in Table 21.1 and Figure 21.8

THE SAVING/INVESTMENT APPROACH TO EQUILIBRIUM

Because aggregate income must cither be saved or spent, by definition, Y= C+ S, which isan

identity. The equilibrium condition is Y= C+ 1, but this is not an identity because it does not

hold when we are out of equilibrium.* By substituting C+ § for Yin the equilibrium condi

tion, we can write

C+S=C+1

Because we can subtract C from both sides of this equation, we are left with

S=1

Thus, only when planned investment equals saving will there be equilibrium,

‘This saving/investment approach to equilibrium stands to reason intuitively if we recall

‘two things: (1) Output and income are equal, and (2) saving is income that is not spent. Because

it is not spent, saving is like a leakage out of the spending stream. Only if that leakage is coun-

terbalanced by some other component of planned spending can the resulting planned aggre

gate expenditure equal aggregate output. This other component is planned investment (0)

This counterbalancing effect can be seen in Figure 21.9. Aggregate income flovis into

households, and consumption and saving flow out. The diagram shows saving flowing from

households into the financial market. Firms use this saving to finance investment projects. If

the planned investment of firms equals the saving of households, then planned aggregate

expenditure (AE = C + 1) equals aggregate output (income) (¥), and there is equilibrium:

The leakage out of the spending stream—saving—is matched by an equal injection of

planned investment spending into the spending stream. For this reason, the saving/invest-

‘ment approach to equilibrium is also called the leakages/injecrions approach to equilibrium,

Planned aggregate

‘expenditure

ence)

Saving (5)

Aggregate neome Y)

‘Saving isa leakage out ofthe spending stream. If planned investment is exactly equal to saving, then

planned aggregate expenditure is exactly equal to aggregate output, and there is equilirium.

‘ti would bean deny Fincad unplanned invetory acumuaions—in eer won f ere actaalimvestment instead of

nme este

cuarter 21 467

‘Aageaats Expenditure

an Elo Output

inventories, investment, aggregate expenditure Ea

© Further Exploration © News Analysis

SS Inventory Changes Signal

Slower Growth

The Effect of a Natural

Disaster on Government

Spending and Taxation, | IN JUNE 2005, THE GOVERNMENT

announced that imentres hed at

ce USS wlesaler increase by 1.1 pe

cert, woh was more han analyte

and fms had expected, Since inven

Real Goods as a Store | tary inaases are par of ivestment

of Value During Inflation | spending, the nee was counted 2

ar of GDP Bix what abot “lanes

lvestment spending which measures

the toa spending on goods and se

wees that ms “plan make in

en prog?

| an unerecod increase in iment

| ies means tat actual sales ae less

Money Demand than what was expected Ths they

and interest Rates to lead to fms outing back on pro

ducton inthe fate

Pemaps the unantipated sein

invemores in 2005 was 0 signal of

with Detiation

things to come?

Bloonoers.com ‘mor than a year, @ goverment reper _iwentariesat_ wholesales of

sowed. durable goods, which include cat,

- The June increase in vetoes, machinery and appliances, ose 14

U.S. Wholesalers’ whlch brought the value of goods at percent June after rsing 1.9 per

Sisbutors,warsnouses an termi- ent the previous month, Sales ose

Inventories Rose 1.1% fais $309.5 nilon,foloned a 05 pera ater nochange te

i {ain of 14 percent the moth bea, vious month. A 1 pereet crop in

in June (Update 1) te commerce Deparment sai In Sls of electal equpment ater a

Washington, Sales were unchanged 39 erent increase 8 month arer

ee Se

‘ug. 9 (Bloomberg)Imentores stan increase of 0.3 percent in May. sales.

US. wholesalers ose 1.1 percent in Consumer spending cooled bythe

June, eater than forecast, as sales most in almost thee year ving the =

fale 0 Inerease for he fst time in month “Sauer oonoea ie

Figure 21.10 reproduces the saving schedule derived in Figure 21.6 and the horizontal

investment function from Figure 21.7. Notice that $= at one, and only one, level of aggregate

output, Y= 500. At Y = 475 and I = 25. In other words, Y= C+ I, and therefore

equilibrium exists.

ADJUSTMENT TO EQUILIBRIUM

We have defined equilibrium and learned how to find it, but we have said nothing about how

firms might react to disequilibrium. Let us consider the actions firms might take when

planned aggregate expenditure exceeds aggregate output (income).

‘We already know the only way firms can sell more than they produce is by selling some

inventory. This means that when planned aggregate expenditure exceeds aggregate output,

cnapter 21 469

xponature

2d Eglo Outpt

Aggregate output, Y(ilions of dolls)

‘Aggregate outout will be equal to planned aggregate expenciture only when saving equals planned

investment (S =. Saving and planned investment are equal at ¥ = 500.

‘unplanned inventory reductions have occurred. It seems reasonable to assume firms will

respond to unplanned inventory reductions by increasing output. If firms increase output,

income must also increase (output and income are two ways of measuring the same thing).

[As GM builds more cars it hires more workers (or pays its existing workforce for working

‘more hours), buys more steel uses more electricity, and so on. These purchases by GM rep-

resent income for the producers of labor, stel, electricity, and so on. If GM (and all other

firms) try to keep their inventories intact by increasing production, they will generate more

income in the economy as a whole. This will lead to more consumption. Remember, when

income rises, consumption also rises

The adjustment process will continue as long as output (income) is below planned

aggregate expenditure. If firms react to unplanned inventory reductions by increasing

‘output, an economy with planned spending greater than output will adjust to equilib-

rium, with ¥ higher than before. If planned spending is less than output, there will be

unplanned increases in inventories. In this case, firms will respond by reducing output.

‘As output falls, income falls, consumption falls, and so forth, until equilibrium is

restored, with Ylower than before.

AAs Figure 21.8 shows, at any level of output above Y= 500, such as Y= 800, output will

fall until it reaches equilibrium at Y = 500, and at any level of output below Y= 500, such as.

Y= 200, output will rise until it reaches equilibrium at Y= 5005

THE MULTIPLIER

"Now that we know how the equilibrium value of income is determined, we ask: How does

the equilibrium level of output change when planned investment changes? If thre isa sud:

dden change in planned investment, how will output respond, if it responds at all? As we will

see, the change in equilibrium output is greater than the initial change in planned invest-

‘ment. Output changes by a multiple of the change in planned investment. So, this multiple is,

called the multiplier.

“tn dicusing simple supply and demand equim in Chapters 3 and 4 we that when quanti spi ced uanty

ead the pic fale nd the quantity pie declines Sar when quantity demande exces quant sapped the pice

"sand the qunaty spied nce th ana ere we ae orig poten in pies oi the pice vane

‘easing on chang inthe el of lott income Later ae we hve intodued mote athe pric lee the anass,

pre wl beer pore A his sg, however only peste output (nce) (1) ads when area xpd xed

reat: tpt ith ovestor ling or when geal cxrde appeal expend (wh venoy lg).

‘multiptior The ratio of the

change inthe equilibrium eve of

output toa change in some

‘autonomous variable,

autonomous variabi

Avarable tat is assumed not

to depend onthe state of the

‘economy—that sit does not

change when the economy

changes.

‘The muttiplier is defined as the ratio of the change in the equilibrium level of output to a

‘change in some autonomous variable, An autonomous variable isa variable that is assumed

not to depend on the state of the econom)—that is, a variable is autonomous if it does not

change in response to changes in the economy: In this chapter, we consider planned investment

to be autonomous. This simplifies our analysis and provides a foundation for later discussions.

With planned investment autonomous, we can ask how much the equilibrium level of

‘output changes when planned investment changes. Remember that we are not trying here to

explain why planned investment changes: we are simply asking how much the equilibrium

level of output changes when (for whatever reason) planned investment changes. (Beginning

in Chapter 25, we will no longer take planned investment as given and will explain how

planned investment is determined.)

Consider a sustained increase in planned investment of $25 billion—that is, suppose 1

increases from $25 billion to $50 billion and stays at $50 billion. If equilibrium existed at [= $25

billion, an increase in planned investment of $25 billion will cause a disequilibrium, with

planned aggregate expenditure greater than aggregate output by $25 billion. Firms immediately

see unplanned reductions in their inventories, and, as a result they begin to increase output.

Let us say the increase in planned investment comes from an anticipated increase in

travel that leads airlines to purchase more airplanes, car rental companies to increase pur-

chases of automobiles, and bus companies to purchase more buses (all capital goods). The

firms experiencing unplanned inventory declines will be automobile manufacturers, bus

producers, and aircraft producers—GM, Ford, Boeing, and so forth. In response to declining

inventories of planes, buses, and cars these firms will increase output.

Now suppose these firms raise output by the full $25 billion increase in planned invest-

ment. Does this restore equilibrium? No, it does not, because when output goes up, people

earn more income and a part of that income will be spent. This increases planned aggregate

expenditure even further. In other words, an increase in Talso leads indirectly to an increase

in C.To produce more airplanes, Boeing has to hire more workers or ask its existing employ-

ces to work more hours. It also must buy more engines from General Electric, more tires

from Goodyear, and so forth. Owners of these firms will earn more profits, produce more,

hire more workers, and pay out more in wages and salaries.

‘This added income does not vanish into thin ait. It is paid to households that spend

some oft and save the rest. The added production leads to added income, which leads

to added consumption spending.

If planned investment (1) goes up by $25 billion initially and is sustained at this higher

levelan increase of output of $25 billion will not restore equilibrium, because it generates even

‘more consumption spending (C). People buy more consumer goods. There are unplanned

reductions of inventories of basic consumption items—washing machines, food, clothing,

and so forth—and this prompts other firms to increase output. The cycle stars all over again.

Output and income can rise by significantly more than the initial increase in planned invest

‘ment, buthow much and how large isthe multiplier? This is answered graphically in Figure 21.11

‘Assume the economy isin equilibrium at point A, where equilibrium output is 300. The increase

in fof 25 shifts the AE= C+ Icurve up by 25, because Iis higher by 25 at every level of income.

The new equilibrium occurs at point B, where the equilibrium level of output is 600. Like

‘eng th ciclo nay agg out it gi with Y= > 1 Tha cer per rege opt pr

‘iced yrs and every period, lane agate expen ss sue take hse gods ad series of he marke

Now ote what happens we planed neste spending incense nd insted a higher eel ems experience

‘npland declines in irene od they ince opt ore el utp produced in aubeequnt prods, However, the

ded opt means more income; hus we se added noms ving to hocks Ths meats more spending Howseelds

spend some portion other ed incon (equal othe aed income times the MPC) on consumer sod.

‘hat wth ighereonsumption planed aggrept expenditure wil be preter Firms ain se an npn dectine invents

tie and they respond by nceting the opt of consume rods Ths set of et anther round of income and expendi

increase Output ise and income ss esl, thi increnng consampion Higher consumption eds oye another d-

‘alluvial and outta ser pin

cnapren s1 471.

agree pence

and Eulbam Ovtpt

aye 00

Aggregate output, Y(ilions of dallas)

{At point A the economy is in equilrium at Y= 500. When | increases by 25, planned aggregate expen

‘ture is intially greater than aggregate output. As output rises in response, additional consumption is

generated, pushing equlvium output up by a multiple ofthe intial increase in|. The new equilibrium

Is found at point 8, where Y = 600. Equilbrium output has increased by 100 (600 - 500) o four times

‘the amount of the increase in planned investment.

point A, point Bis on the 45° line and is an equilibrium value. Output (¥) has increased by 100

(600 — 500), or four times the inital increase in planned investment of 25, between point A and

point B The multiplier in this example is 4. At point B, aggregate spending is also higher by 100.

If 25 of this additional 100 is investment (J, as we know itis the remaining 75 is added con-

sumption (C), From point Ato point B then, AY= 100, Al= 25, and AC=75.

Why doesn't the multiplier process go on forever? The answer is that only a fraction of

the inerease in income is consumed in each round, Successive increases in income become

smaller and smaller in each round of the multiplier process, due to leakage as saving, until

equilibrium is restored.

The size of the multiplier depends on the slope of the planned aggregate expenditure

line. The steeper the slope of this line is, the greater the change in output for a given change

in investment. When planned investment is fied, asin our example, the slope of the AE= C

+ Tine is just the marginal propensity to consume (ACIAY). The greater the MPC is, the

{greater the multiplier. This should not be surprising. A large MPC means that consumption

increases a lot when income increases. The more consumption changes, the more output has

to change to achieve equilibrium.

THE MULTIPLIER EQUATION

Is there a way to determine the size ofthe multiplier without using graphhic analysis? Yes, theres.

‘Assume that the market is in equilibrium at an income level of ¥ = 500. Now suppose

planned investment (/)—thus planned aggregate expenditure (AE)—increases and remains

higher by $25 billion, Planned aggregate expenditure is greater than output, there is an

unplanned inventory reduction, and firms respond by increasing output (income) (¥). This,

leads to a second round of increases, and so on.

What will restore equilibrium? Look at Figure 21.10 and recall: Planned aggregate expen-

diture (AE® C+ 1)is not equal to aggregate output (¥) unless $= fthe leakage of saving must

exactly match the injection of planned investment spending for the economy to be in equi-

librium. Recall also we assumed that planned investment jumps to a new, higher level and

stays there; i isa sustained increase of $25 billion in planned investment spending. As income

rises, consumption rises and so does saving. Our $= I approach to equilibrium leads us to

conclude:

Equilibrium will be restored only when saving has increased by exactly the amount of

‘the initial increase in J

Otherwise, will continue to be greater than $, and C+ Iwill continue to be greater than ¥.

(The $= approach to equilibrium leads to an interesting paradox in the macroeconomy.

‘See the Further Exploration box, “The Paradox of Thrift”)

Itis possible to figure how much ¥ must increase in response to the additional planned

investment before equilibrium will be restored. ¥ will rie, pulling $ up with it until the

change in saving is exactly equal to the change in planned investment—that is, until Sis

again equal to [at its new higher level. Because added saving isa fraction of added income

(the MPS), the increase in income required to restore equilibrium must be a multiple of the

increase in planned investment.

Recall that the marginal propensity to save (MPS) isthe fraction of a change in income

that is saved. Iti defined as the change in S (AS) over the change in income (AY).

as

ps = 9S

ay

Because AS must be equal to Al for equilibrium to be restored, we can substitute AJ for AS

and solve:

AL

ay

‘Therefore,

ay =arx

MPS

As you can see, the change in equilibrium income (A¥) is equal to the initial change in

planned investment (Al) times 1/MPS. The multiplier is 1/ MPS:

1

‘multiplier = 1

la ‘MPS

Because MPS + MPC 1, MPS= 1 - MPC. It follows that the multiplier is equal to

1

ultplier =

multiplier

In our example, the MPCis.75, so the MPS must equal 1 ~.75, or 25. Thus, the multi-

plier is 1 divided by .25, or 4. The change in the equilibrium level of Yis 4 x $25 billion,

6 $100 billion.” Also note that the same analysis holds when planned investment falls. If

The muir an aloe drive algebraic s the append to this chapter demonstrates

An interesting paradox can arise wiien house

holds attempt to increase their saving. What

happens i households become concerned

about the future and want to save more today

to be prepared for hard times tomorrow? It

households increase ther planned saving, the

saving schedule in Figure 1 shits upward from

$05; The plan to save more isa planto con

sme less, and the resulting drop In spending

leads to a drop in income. Income drops by 3

‘multiple ofthe inital shit the saving sched

le. Before the increase in saving, equilibrium

exists at point A, whete S, = and Y= $500 bi

lion Increased saving shits the equim to

intB, the point at which, = New equi

rium output is $300 bilion—a $200 billion

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- New Doc 2019-10-17 21.16.16Document4 pagesNew Doc 2019-10-17 21.16.16udit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Flattening of The Phillips Curve Implications For PDFDocument22 pagesFlattening of The Phillips Curve Implications For PDFudit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Ecode Marks-Fya 1. QUIZ / 40 Total Score AG QUIZ MarksDocument2 pagesEcode Marks-Fya 1. QUIZ / 40 Total Score AG QUIZ Marksudit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Macro Project PDFDocument8 pagesMacro Project PDFudit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Fashion Clothing Consumption Among NMIMS Students: 3.1 ToolDocument3 pagesFashion Clothing Consumption Among NMIMS Students: 3.1 Tooludit raj singhNo ratings yet

- Law Assignment Tort-Liability Udit Raj Singh, FYA Roll No. A050Document4 pagesLaw Assignment Tort-Liability Udit Raj Singh, FYA Roll No. A050udit raj singhNo ratings yet

- F.Y.B.Sc. Div A (A.Y. 19-20) Roll No. First Name Last Name Student NumberDocument6 pagesF.Y.B.Sc. Div A (A.Y. 19-20) Roll No. First Name Last Name Student Numberudit raj singhNo ratings yet