Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Semiotics Preprint

Semiotics Preprint

Uploaded by

Ragam NetworksCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- English Stage 7 P2 QPDocument8 pagesEnglish Stage 7 P2 QPHarvey Haron100% (4)

- Toronto Biennial PDFDocument45 pagesToronto Biennial PDFRagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- Prior Semiotics 2014 PDFDocument16 pagesPrior Semiotics 2014 PDFVanessa PalmaNo ratings yet

- Prior Semiotics 2014Document16 pagesPrior Semiotics 2014Denise Janelle GeraldizoNo ratings yet

- Arzarello Semiosis Mudimodal 08 PDFDocument32 pagesArzarello Semiosis Mudimodal 08 PDFJoseph M. GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Field and Dynamic Nature of Sensemaking. Theoretical and Methodological ImplicationsDocument41 pagesField and Dynamic Nature of Sensemaking. Theoretical and Methodological ImplicationsLucas EdNo ratings yet

- IndexicalityDocument6 pagesIndexicalityInsight PeruNo ratings yet

- Encoding DecodingDocument7 pagesEncoding Decodingpericles127897No ratings yet

- Vdoc - Pub Classics of Semiotics 226 250Document25 pagesVdoc - Pub Classics of Semiotics 226 250limberthNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Language and What Comes Beyond ItDocument11 pagesMeaning of Language and What Comes Beyond Itsanjana singhNo ratings yet

- CassLogicSenseandSenseRelations PDFDocument13 pagesCassLogicSenseandSenseRelations PDFمحمد العراقيNo ratings yet

- 130 - Gestures and Iconicity: 5 - ReerencesDocument21 pages130 - Gestures and Iconicity: 5 - ReerencesAlejandro Israel Garcia EsparzaNo ratings yet

- Footing Frame AlignmentDocument3 pagesFooting Frame AlignmentGallagher RoisinNo ratings yet

- Carston CogpragsDocument17 pagesCarston CogpragsOmayma Abou-ZeidNo ratings yet

- Halliday, M.a.K. - (1992) How Do You Mean2ppDocument16 pagesHalliday, M.a.K. - (1992) How Do You Mean2ppGladys Cabezas PavezNo ratings yet

- FUNCTIONS of LANGUAGE L. HébertDocument7 pagesFUNCTIONS of LANGUAGE L. HébertGonzalo Muniz100% (2)

- Conceptual and Historical Background: 2.2.1 The English Passive ConstructionDocument14 pagesConceptual and Historical Background: 2.2.1 The English Passive Constructionhoggestars72No ratings yet

- Semiotics TheoryDocument24 pagesSemiotics TheoryAyyash AlyasinNo ratings yet

- GrammarDocument28 pagesGrammarmarcelolimaguerraNo ratings yet

- H. Paul Manning - On Social Deixis (2001) (10.2307 - 30028583) - Libgen - LiDocument48 pagesH. Paul Manning - On Social Deixis (2001) (10.2307 - 30028583) - Libgen - LiGLORIA CHENNo ratings yet

- Lectures 5 Word-Meaning Types of Word-Meaning. Grammatical Meaning and Lexical MeaningDocument4 pagesLectures 5 Word-Meaning Types of Word-Meaning. Grammatical Meaning and Lexical MeaningЕкатерина ПустяковаNo ratings yet

- Imagining Cog Life ThingsDocument9 pagesImagining Cog Life ThingsLilia VillafuerteNo ratings yet

- The Power of Javanese - SEMIOTIKADocument17 pagesThe Power of Javanese - SEMIOTIKAHappiness DelightNo ratings yet

- Discursive Practices. Verbal InteractionsDocument90 pagesDiscursive Practices. Verbal InteractionsDaniela RDNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Semiotic and Mimetic Processes in Australopithecus AfarensisDocument13 pagesAn Analysis of Semiotic and Mimetic Processes in Australopithecus AfarensisDyah AmuktiNo ratings yet

- Gofman (Review) Frame Analysis Reconsidered PDFDocument10 pagesGofman (Review) Frame Analysis Reconsidered PDFCarlos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Barthes: Intro, Signifier and Signified, Denotation and ConnotationDocument5 pagesBarthes: Intro, Signifier and Signified, Denotation and ConnotationDungarmaa ErdenebayarNo ratings yet

- The Difference Between Semiotics and SemDocument17 pagesThe Difference Between Semiotics and SemNora Natalia LerenaNo ratings yet

- Materiality Ontology and The AndesDocument25 pagesMateriality Ontology and The AndesSILVIA ESTELANo ratings yet

- LexikologiaDocument2 pagesLexikologiaLeysan AkhmetshinaNo ratings yet

- 5 - Bab 2Document21 pages5 - Bab 2rifai asnawiNo ratings yet

- The Functions of LanguageDocument7 pagesThe Functions of LanguageFlorinNo ratings yet

- Skinners Elementary Verbal Relations - Some New CategoriesDocument3 pagesSkinners Elementary Verbal Relations - Some New CategoriesJuan EstebanNo ratings yet

- The Referential Hierarchy and Attention (Faits de Langues, Vol. 39, Issue 1) (2012)Document15 pagesThe Referential Hierarchy and Attention (Faits de Langues, Vol. 39, Issue 1) (2012)Maxwell MirandaNo ratings yet

- Mittelberg I Evola V 2014 Iconic and RepDocument15 pagesMittelberg I Evola V 2014 Iconic and RepDenisaNo ratings yet

- Context in The Analysis of Discourse and Interaction: Ingrid de Saint-GeorgesDocument7 pagesContext in The Analysis of Discourse and Interaction: Ingrid de Saint-GeorgesAbdelhamid BNo ratings yet

- The Semiotic TriangleDocument5 pagesThe Semiotic TriangleEstefania Penagos CanizalesNo ratings yet

- Tracking The Origin of Signs in Mathematical Activity: A Material Phenomenological ApproachDocument35 pagesTracking The Origin of Signs in Mathematical Activity: A Material Phenomenological ApproachWolff-Michael RothNo ratings yet

- Word Semantics, Sentence Semantics and Utterance SemanticsDocument11 pagesWord Semantics, Sentence Semantics and Utterance SemanticsАннаNo ratings yet

- SEMASIOLOGY 1 - Aspects of Lexical MeaningDocument5 pagesSEMASIOLOGY 1 - Aspects of Lexical MeaningLilie Bagdasaryan100% (2)

- лексикологія 3 семінарDocument9 pagesлексикологія 3 семінарYana DemchenkoNo ratings yet

- CDA (Article) - Norman FaircloughDocument28 pagesCDA (Article) - Norman Faircloughমুহাম্মাদ হুসাইনNo ratings yet

- SemioticsDocument4 pagesSemioticsPrincess MuskanNo ratings yet

- Comparative Translational Semiotic Analysis of The River of Fire' Through Systemic Functional Linguistic ApproachDocument12 pagesComparative Translational Semiotic Analysis of The River of Fire' Through Systemic Functional Linguistic ApproachLinguistic Forum - A Journal of LinguisticsNo ratings yet

- Discovering The Functions of Language in Online ForumsDocument6 pagesDiscovering The Functions of Language in Online ForumsBarbara ConcuNo ratings yet

- Modeling Intersemiotic TranslationDocument10 pagesModeling Intersemiotic TranslationAnonymous gp78PX1WcfNo ratings yet

- Hodge Semiotics PrimerDocument6 pagesHodge Semiotics Primeryolanda candimaNo ratings yet

- 0apuntes PragmaticaDocument36 pages0apuntes PragmaticarandomeoNo ratings yet

- 2001 Gibbs Embodied Experience and Linguistic MeaningDocument15 pages2001 Gibbs Embodied Experience and Linguistic MeaningJoseNo ratings yet

- Vdoc - Pub Classics of Semiotics 251 275Document25 pagesVdoc - Pub Classics of Semiotics 251 275limberthNo ratings yet

- Menin & Schiavo - Rethinking Musical Affordances PDFDocument16 pagesMenin & Schiavo - Rethinking Musical Affordances PDFTomás CabadoNo ratings yet

- 475 Lecture 3Document13 pages475 Lecture 3Ангелина МихалашNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4Document5 pagesLecture 4Bohdan HutaNo ratings yet

- Pragmatism PragmaticsDocument6 pagesPragmatism PragmaticsGeorgiana Argentina DinuNo ratings yet

- Divjak, Milin & Medimorec (2019) Construal in LanguageDocument36 pagesDivjak, Milin & Medimorec (2019) Construal in LanguageClara Iulia BoncuNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document32 pagesUnit 1marta aguilarNo ratings yet

- Zooming On IconicityDocument18 pagesZooming On IconicityJuan MolinayVediaNo ratings yet

- Meaning Making in Communications Procceses. The Rol of A Human Agency - ARTICULO-2015Document4 pagesMeaning Making in Communications Procceses. The Rol of A Human Agency - ARTICULO-2015Gregory VeintimillaNo ratings yet

- Tolman y Brunswik Organism and The Causal Texture of The Environment PDFDocument35 pagesTolman y Brunswik Organism and The Causal Texture of The Environment PDFItzcoatl Torres AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Social Semiotics and Visual Grammar: A Contemporary Approach To Visual Text ResearchDocument13 pagesSocial Semiotics and Visual Grammar: A Contemporary Approach To Visual Text ResearchSemyon A. AxelrodNo ratings yet

- CUMMING, Naomi - SemioticsDocument8 pagesCUMMING, Naomi - Semioticsjayme_guimarães_3No ratings yet

- Comments on Chris Sinha’s Essay (2018) "Praxis, Symbol and Language"From EverandComments on Chris Sinha’s Essay (2018) "Praxis, Symbol and Language"No ratings yet

- Katalog Gieff Catalogue - 150dpiDocument43 pagesKatalog Gieff Catalogue - 150dpiRagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- 2020 Experiments in CinemaDocument12 pages2020 Experiments in CinemaRagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- The Same Thing From Different Angles ResDocument18 pagesThe Same Thing From Different Angles ResRagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- 2019 Danusiri Toronto Biennial ONE PAGEDocument1 page2019 Danusiri Toronto Biennial ONE PAGERagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- Japanese StudiesDocument4 pagesJapanese StudiesRagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- Son ETDocument10 pagesSon ETRagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- Revolution of Hope: Independent Films Are Young, Free and Radical by Katinka Van HeerenDocument4 pagesRevolution of Hope: Independent Films Are Young, Free and Radical by Katinka Van HeerenRagam Networks100% (1)

- CAVELL WITTGENSTEIN Seminar Syllabus PDFDocument6 pagesCAVELL WITTGENSTEIN Seminar Syllabus PDFRagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- Next Steps For Nodes, Nets, and SNA Analysis in Evaluation: Maryann M. Durland, Kimberly A. FredericksDocument3 pagesNext Steps For Nodes, Nets, and SNA Analysis in Evaluation: Maryann M. Durland, Kimberly A. FredericksRagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- 156 FTPDocument4 pages156 FTPRagam NetworksNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1,2,3Document48 pagesLecture 1,2,3Mercyless K1NG-No ratings yet

- Reception and Reception AreaDocument1 pageReception and Reception AreaPattieNo ratings yet

- Subject Verb AgreementDocument21 pagesSubject Verb AgreementKiervin ZapantaNo ratings yet

- Learning Module Euthenics 2 Philippine CultureDocument7 pagesLearning Module Euthenics 2 Philippine CultureCedie BringinoNo ratings yet

- Taos To EnglishDocument11 pagesTaos To EnglishZachary RobinsonNo ratings yet

- The Sacrifice LPDocument4 pagesThe Sacrifice LPregineNo ratings yet

- Purposive Communication Semi ExamDocument28 pagesPurposive Communication Semi ExamAngelie Selle A. GaringanNo ratings yet

- EAPP Lesson 1 Academic TextDocument17 pagesEAPP Lesson 1 Academic TextJennifer DumandanNo ratings yet

- UNIT 7 ComparisonDocument5 pagesUNIT 7 ComparisonEmbenNo ratings yet

- Karina Didenko - Present PerfectDocument4 pagesKarina Didenko - Present PerfectKarina SmilleNo ratings yet

- Model United Nations: CETMUN XXIIDocument3 pagesModel United Nations: CETMUN XXIIMAURICIO ORTEGA GORDILLONo ratings yet

- B2 Grammar Communication Teacher - S NotesDocument5 pagesB2 Grammar Communication Teacher - S NotesАлена СылтаубаеваNo ratings yet

- 2AS Yearly Planning Bendjeddou NailaDocument10 pages2AS Yearly Planning Bendjeddou NailaNadia TemimNo ratings yet

- Word FormationDocument4 pagesWord FormationGia Hung TaNo ratings yet

- Situation: Unit 2. Session 2.-Commercial LetterDocument29 pagesSituation: Unit 2. Session 2.-Commercial LetterVictor Felix Espinoza DiazNo ratings yet

- Ielts 4.5 Listening Wk.10Document10 pagesIelts 4.5 Listening Wk.10Tran Ngoc Bao Chau 700646No ratings yet

- APTIS Advanced READING With Answer KeyDocument6 pagesAPTIS Advanced READING With Answer KeySattarov IslambekNo ratings yet

- List of English Irregular VerbsDocument6 pagesList of English Irregular VerbsWagner L MedeirosNo ratings yet

- RedundancyDocument73 pagesRedundancyLAIZA SOJONNo ratings yet

- That O: What Y MEDocument64 pagesThat O: What Y MESeemant Dadu100% (1)

- Language Hub Workbook Beginner Unit 1Document4 pagesLanguage Hub Workbook Beginner Unit 1Severo Colin KarinaNo ratings yet

- English - Grammar - L.No. 4 - Singular and PluralDocument6 pagesEnglish - Grammar - L.No. 4 - Singular and PluralRashmi ChoudhariNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Post-Velar Consonants On Vowels in Nuu-Chah-Nulth: Auditory, Acoustic, and Articulatory EvidenceDocument40 pagesThe Effects of Post-Velar Consonants On Vowels in Nuu-Chah-Nulth: Auditory, Acoustic, and Articulatory EvidenceDương NguyễnNo ratings yet

- key đọc 1Document40 pageskey đọc 1Nguyễn HuynhNo ratings yet

- Phonological Reconstruction of Proto HlaiDocument618 pagesPhonological Reconstruction of Proto HlaipeterchtrNo ratings yet

- 26 English Swear Words That You Thought Were HarmlessDocument7 pages26 English Swear Words That You Thought Were HarmlessAmr Khalid Al-MosabiNo ratings yet

- Key2e L1 Worksheets Vocabulary Unit 3 2starDocument1 pageKey2e L1 Worksheets Vocabulary Unit 3 2starMelissa IglesiasNo ratings yet

- Evidence Consolidation ActivityDocument3 pagesEvidence Consolidation Activityjorge zuluagaNo ratings yet

- Your Next Holiday Destination - Maria JoseDocument11 pagesYour Next Holiday Destination - Maria JoseJuan Diego LozanoNo ratings yet

Semiotics Preprint

Semiotics Preprint

Uploaded by

Ragam NetworksOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Semiotics Preprint

Semiotics Preprint

Uploaded by

Ragam NetworksCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/292653946

Semiotics: Interpretants, inference, and intersubjectivity

Chapter · January 2010

DOI: 10.4135/9781446200957.n12

CITATIONS READS

4 99

1 author:

Paul Kockelman

Yale University

67 PUBLICATIONS 795 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Paul Kockelman on 29 January 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

12

Semiotics

Paul Kockelman

12.1 INTRODUCTION1 fundamental features of semiotic processes

through the lens of Peirce’s lexicon: sign, object,

Charles Sanders Peirce (1839–1914) was an interpretant; iconic, indexical, symbolic; and so

American philosopher, mathematician and logi- forth. It differs from the usual summaries of

cian. To sociolinguists, he is perhaps best known Peirce by focusing on the interpretant (in contrast

for his theory of semiotics, with its focus on logic to the sign or object), and by focusing on infer-

and nature, and the ways this contrasted with ence (in contrast to indexicality). Section 12.3

Saussure’s semiology, with its focus on language uses these concepts to reframe the nature of social

and convention. In particular, he foregrounded relations and cognitive representations. Starting

iconic and indexical relations between signs and out from the work of the Boasian, Ralph Linton, it

objects, theorizing the way meaning is motivated theorizes social statuses and mental states through

and context-bound. And he foregrounded inferen- the lens of semiosis and intersubjectivity. Section

tial relations between signs and interpretants, 12.4 uses this reframing to recast performativity

foregrounding the role of abduction (or hypothesis) and agency. By reading Mead through the lens of

over deduction, and thereby the role of context Peirce, and reading Austin through the lens of

over code. He inspired Roman Jakobson’s (1990) Mead, it widens our understanding of the efficac-

understanding of the role of shifters in language – ity of speech acts to include sign events more

which has provided a central insight for two generally.

decades of linguistic anthropology and discourse

analysis: for example, Haliday and Hasan (1976)

on cohesion, Brown and Gilman (1972 [1960]) on

pronouns, and Silverstein (1995 [1976]) and Hanks 12.2 SEMIOSIS: THE PUBLIC FACE

(1990) on social and spatial deixis. He inspired OF COGNITIVE PROCESSES

George Herbert Mead’s (1934) understanding of

the relation between selves and others, as gener- Semiotics is the study of semiosis, or ‘meaning,’ a

ated by the unfolding of gestures and symbols – process which involves three components: ‘signs’

which grounded influential ideas in philosophy and (whatever stands for something else); ‘objects’ (what-

biosemiosis (Morris 1938; Sebeok and Umiker- ever a sign stands for); and ‘interpretants’

Sebeok, 1992), conversational analysis (Sachs, (whatever a sign creates insofar as it stands for an

Schegloff and Jefferson, 1974), sociolinguistics object) – see Table 12.1 (column 2).

(Goffman, 1959; Labov, 1966), and even speech In particular, any semiotic process relates these

act theory (Austin, 2003 [1955]; Searle, 1969). three components in the following way: a sign

This chapter explicates key terms from semiot- stands for its object on the one hand, and its inter-

ics and pragmatics, and uses these to reconceptu- pretant on the other, in such a way as to make

alize the relation between mental states, social the interpretant stand in relation to the object

statuses and speech acts. Section 12.2 lays out the corresponding to its own relation to the object

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 1 3/19/2010 6:48:12 PM

2 THE SAGE HANDBOOK OF SOCIOLINGUISTICS

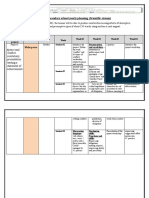

Table 12.1 Typology of distinctions (semiosis)

Categories Semiotic Sign Ground Interpretant Social Agent Community

process relation

Firstness Sign Qualisign Iconic Affective Role Control Commonality

Secondness Object Sinsign (token) Indexical Energetic Status Compose Contrast

Thirdness Interpretant Legisign (type) Symbolic Representational Attitude Commit Consciousness

(see Peirce, 1931–35). What is at issue in mean- (the sign and interpretant) are foregrounded.

ingfulness, then, is not one relation between a sign In particular, a type of utterance (or action) gives

and an object (qua ‘standing for’), but rather a rise to another type of utterance (or action) insofar

relation between two such relations (qua ‘corre- as it is understood to express a proposition

spondence’). The logic of this relation between (or purpose).

relations is shown in Figure 12.1. Indeed, the constituents of so-called ‘material

For example, ‘joint-attention’ is a semiotic culture’ are semiotic processes (Kockelman,

process. In particular, a child turning to observe 2006a). For example, an ‘affordance’ is a semiotic

what her father is observing, or turning to look at process whose sign is a natural feature, whose

where her mother is pointing, involves an interpre- object is a purchase, and whose key interpretant is

tant (the child’s change of attention), an object an action that heeds that feature, or an instrument

(what the parent is attending to, or pointing that incorporates that feature (so far as the feature

towards) and a sign (the parent’s direction of ‘provides purchase’). For example, walking care-

attention, or gesture that directs attention). As fully over a frozen pond (as an action) is an inter-

Mead noted (1934), any interaction is a semiotic pretant of the purchase provided by ice (as an

process. For example, if I pull back my fist affordance), insofar as such a form of movement

(first phase of an action, or the sign), you duck heeds the slipperiness of ice. An ‘instrument’ is a

(reaction, or the interpretant) insofar as my next semiotic process whose sign is an artificed entity,

move (second phase of action, or the object) whose object is a function, and whose key interpre-

would be to punch you. Generalizing interaction, tant is an action that wields that entity, or another

the ‘pair-part structures’ of everyday interaction – instrument that incorporates that instrument

the fact that questions are usually followed by (so far as it ‘serves a function’). For example, a

answers, offers by acceptances, commands by knife (as an instrument) is an interpretant of the

undertakings, assessments by agreements, and so purchase provided by steel (as another instrument),

forth (Goffman, 1981; Sachs et al., 1974) – consist insofar as such a tool incorporates the hardness

of semiotic processes in which two components and sharpness of steel.

(c)

Object Interpretant

correspondence

(b)

(a)

Sign

Figure 12.1 Semiosis as a Relation between Relations. A sign stands for its object on the one hand

(a), and its interpretant on the other (b), in such a way as to bring the latter into a relation to the former

(c), corresponding to its own relation to the former (a).

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 2 3/19/2010 6:48:12 PM

SEMIOTICS 3

Notice from these examples that signs can be quality that must necessarily be paired with a type

eye-directions, pointing gestures, utterances, con- of object (across all events) and is sometimes

trolled behaviours, environmental features and referred to as a ‘type’ – see Table 12.1 (column 3).

artificial entities. Objects can be the focus of For example, in the case of utterances, a quali-

attention, purposes, propositions and functions. sign is a potential cry (say, what is conceivably

And interpretants can be other utterances, changes utterable by a human voice); a sinsign is an actual

in attention, reactions, instruments, and heeding cry (say, the interjection ouch uttered at a particu-

and wielding actions. Notice that very few of lar time and place); and a legisign is a type of cry

these interpretants are ‘in the minds’ of the inter- (say, the interjection ouch in the abstract, or what

preters; yet all of these semiotic processes embody every token of ouch has in common as a type).

properties normally associated with mental enti- Any sinsign that is a token of a legisign as a

ties: attention, desire, purpose, propositionality, type may be called a ‘replica’. Replicas, then, are

thoughts and goals. Notice that very few of these just run-of-the mill sinsigns: any utterance of the

signs are addressed to the interpreters (in the sense word ouch. And, in keeping within this Peircean

of purposely expressed for the sake of their inter- framework, we might call any unreplicable or

pretants) – so that most semiotic processes (such unprecedented sinsign a ‘singularity’ – that is, any

as wielding an instrument) are not intentionally sinsign that is not a token of a type. Singularities,

communicative. And notice how the interpretant then, are one-of-a-kind sinsigns: e.g., Nixon’s

component of each of these semiotic processes is resignation speech. One of the key design features

itself the sign component of an incipient semiotic of language may be stated as follows: given a

process – and hence the threefold relationality finite number of replicas (qua individual signs as

continues indefinitely. parts), speakers may create an infinite number of

While many theorists take semiotic objects to singularities (qua aggregates of signs as wholes).

be relatively ‘objective’ (things like oxen and

trees), these examples show that most objects are _______________________

relatively intersubjective (a shared perspective,

turning on correspondence, in regard to a rela- Given the definition of semiotic process offered

tively intangible entity – such as a proposition or above, the object of a sign is really that to which

purpose). An object, then, is whatever a signer and all (appropriate and effective) interpretants of that

interpreter can correspondingly stand in relation sign correspondingly relate (Kockelman, 2005).

to – it need not be continuously present to the Objects, then, are relatively abstract entities by

senses, taking up volume in space, detachable definition. They should not be confused with

from context, or ‘objective’ in any other sense ‘objects’ in the Cartesian sense of res extensa. Nor

of the word. And while many theorists take inter- should they be confused with the ‘things’ that

pretants – if they consider them at all – to be rela- words seem to stand for. Indeed, it is best to think

tively ‘subjective’ (say, a thought in the mind of an of the object as a ‘correspondence-preserving

addressee), these examples show that most inter- projection’ from all interpretants of a sign. It may

pretants are as objective as signs. Indeed, it may be more or less precise, and more or less consist-

be argued that the typical focus on sign–object ent, as seen by the dotted portion of Figure 12.2.

relations (or ‘signifiers’ and ‘signifieds’), at the For example, if a cat’s purr is a sign, the object

expense of sign–interpretant relations, and this of that sign is a correspondence-preserving pro-

concomitant understanding of objects as ‘objective’ jection from the set of behaviours (or interpretants)

and interpretants as ‘subjective’ – and hence the humans may or must do (within some particular

assimilation of meaning to mind, rather than community) in the context of, and because of, a

grounding mind in meaning – is the fatal flaw of cat’s purr: pick it up and pet it; stroke in under the

twentieth-century semiotics (Kockelman, 2005, chin; exclaim, ‘Oh, that’s so cute!’; offer a sympa-

2006a). These claims will be further fleshed out in thetic low guttural; stay seated, petting it even

what follows. when one needs to pee; and so on. Needless to say,

humans tend to objectify such objects by glossing

_______________________ them in terms of physiology (say, the ‘purr-organ’

has been activated), emotion (say, ‘she must be

Peirce theorized three kinds of signs (1955a). content’), or purpose (say, ‘she wants me to con-

A ‘qualisign’ is a quality that could possibly be tinue petting her’).

paired with an object: i.e. any quality that is acces- While the abstract nature of objects is clearly

sible to the human sensorium – and hence could true for semiotic processes like instruments and

be used to stand for something else (to someone). actions, it is less clearly true for words like ‘cat,’

A ‘sinsign’ is a quality that is actually paired with or utterances such as ‘the ball is on the table,’

an object (in some event) and is sometimes which seem to have ‘objects’ (in the Cartesian

referred to as a ‘token’. A ‘legisign’ is a type of sense) as their objects (in the semiotic sense).

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 3 3/19/2010 6:48:12 PM

4 THE SAGE HANDBOOK OF SOCIOLINGUISTICS

Interpretant #3

(turn to look)

Object Interpretant #1

(objectified as ‘pain’) (ask, are you okay? )

Interpretant #2

(assert, don’t be a sissy)

Sign

(exclaim, ouch! )

Figure 12.2 Object as Correspondence-Preserving Projection. The object of a sign is that to which

all appropriate and effective interpretants of that sign correspondingly relate. It may be understood as a

correspondence-preserving projection from all interpretants.

In order to understand the meaning of such signs, logical relationality, where the object in question

several more distinctions need to be made. First, relates interpretants via inferential articulation

just as there are sin-signs (or sign tokens) and (material and formal deduction and induction).

legisigns (or sign types), there are ‘sin–objects’ And, hand in hand with this inferential articula-

and ‘legi–objects’. Thus, an assertion (or a sen- tion, unlike other object tokens (say, the specific

tence with declarative illocutionary force – say, function of a hammer as wielded on some particu-

‘the dog is under the table’) is a sign whose object lar occasion, or the specific cause of a scream

type is a proposition, and whose object token is a uttered on some particular occasion), states of

state of affairs. A word (or a substitutable lexical affairs and referents are ‘objective’ – in that there

constituent of a sentence – say, ‘dog’ and ‘table’) seem to be actual events that an assertion ‘repre-

is a sign whose object type is a concept, and sents,’ or actual things that a word ‘refers to’. In

whose object token is a referent. Finally, the set short, as will be further developed below, sen-

of all possible states of affairs of an assertion – or tences and words have the property of aboutness

what the assertion could be used to represent – that characterizes intentional phenomena more

may be called an ‘extension’. And the set of generally – not only speech acts like assertions

all possible referents of a word – or what the and promises but also ‘mental states’ like beliefs

word could be used to refer to – may be called a and intentions. While all signs have a property of

‘category’ – see Table 12.2. As is well known, directedness by definition (i.e. they stand for

many battles have been fought over the vector of objects), signs whose objects are propositions

mediation: words mediating concepts and catego- have received extensive characterization – for

ries (‘nominalism’); concepts mediating words their objects seem to be ‘of the world’, and so

and categories (‘conceptualism’); and categories metaphysical worries about mind-world media-

mediating words and concepts (‘realism’). In gen- tion can flourish.

eral, contributions come from all sides.

Unlike other object types (say, the general _______________________

function of a hammer across wieldings, or the

general cause of a scream across utterances), In Peircean semiotics, the relation between the

propositions (and concepts) are inferentially sign and object is fundamental, and is sometimes

articulated. In particular, there is a key species of referred to as the ‘ground’ (Parmentier, 1994: 4;

conditional relationality which may be called Peirce, 1955a). Famously, in the case of symbols,

this relation is arbitrary, and is usually thought to

reside in ‘convention’. Examples include words

Table 12.2 The objects of inferentially like boy and run. In the case of indices, this rela-

articulated signs tion is based in spatiotemporal and/or causal

contiguity. Examples include exclamations like

Sign Sentence Word

‘ouch!’ and symptoms like fevers. And in the case

Object (type) Proposition Concept

of icons, this relation is based in similarity of

Object (token) State of affairs Referent

qualities (such as shape, size, colour or texture).

Object (set of tokens) Extension (world) Category

Examples include portraits and diagrams.

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 4 3/19/2010 6:48:12 PM

SEMIOTICS 5

Notice, then, that the exact same object may objects exist independently of the signs that stand

be stood for by a symbol (say, the word dogs), for them.

an index (say, pointing to a dog), or an icon Importantly, every sign has both an immediate

(say, a picture of a dog). When Saussure speaks of and a dynamic object, and hence involves both a

the ‘arbitrary’ and the ‘motivated’ (1983 [1916]), vector of representation and a vector of determina-

he is really speaking about semiotic processes tion. In certain cases, these immediate and dynamic

whose sign–object relations are relatively sym- objects can overlap – as least in lay understand-

bolic vs relatively iconic–indexical – see Table 1 ings. For example, an interjection ‘ouch!’ or a

(column 4). facial expression of pain may be understood as

Another sense of motivated is the type of regi- determined by pain (as their dynamic objects) and

mentation that keeps a sign–object–interpretant as representing pain (as their immediate objects):

relation in place – be it grounded in norms, rules, one only knows about another’s pain through

laws, causes and so on. In particular, for an entity their cry; yet their pain is what caused that cry.

to have norms requires two basic capacities: it Indeed, a ‘symptom’ should really be defined as a

must be able to imitate the behaviour of those sign whose immediate object is identical to its

around it, as they are able to imitate its behaviour; dynamic object. Dynamic objects, needless to say,

and it must be able to sanction the (non-) imitative often bear a primarily (iconic) indexical relation

behaviour of those around it, and be subject to to their signs, whereas immediate objects often

their sanctions (Brandom, 1979; Haugeland, 1998; bear a primarily (indexical) symbolic relation

Sapir, 1985 [1927]). Norms, then, are embodied in to their signs. However, just as any third is sym-

dispositions: one behaves a certain way because bolic, indexical and iconic, so any sign is partially

one is disposed to behave that way; and one is so determined (having a dynamic object) and par-

disposed because of imitation and sanctioning. tially representing (having an immediate object).

While rules presuppose a normative capacity, Stereotypically, however, one takes the grounds of

they also involve a linguistic ability: a rule must signs to be symbolic and representing, rather than

be formulated in some language (oral or written); (iconic) indexical and determining.

and one must ‘read’ the rule, and do what it says

because that’s what it says (Haugeland, 1998: _______________________

149). Rules, then, are like recipes; following a rule

is like following a recipe; and to have and follow Reframing Grice’s insights (1989; and see

rules requires a linguistic ability. As used here, Strawson, 1954) in a semiotic idiom, there are

‘laws’ are rules that are promulgated and enforced at least four objects of interest in non-natural

by a political entity – say, following Weber (1978: meaning:

54), an organization with a monopoly on the

legitimate use of force within a given territory. 1 My intention to direct your attention to an object

Laws, then, typically make reference to the threat (or bring an object to your attention).

of violence within the scope of polity. Notice, 2 The object that I direct your attention to (or bring

then, that laws presuppose rules, and rules presup- to your attention).

pose norms. Sometimes when scholars speak 3 My intention that you use (2), usually in conjunc-

about motivation, they mean iconic and indexical tion with (1), to attend to another object.

grounds rather than symbolic ones; and some- 4 The object that you come to attend to.

times they mean regimentation by natural causes

rather than cultural norms (rules, laws or conven- There are several ways of looking at the details

tions). The issues are clearly related; but they of this process. Focusing on the relation between

should not be conflated. (2) and (4), there are two conjoined semiotic proc-

Peirce distinguished between immediate objects esses, the first as means and the second as ends.

and dynamic objects. By the ‘immediate object’, Using some kind of pointing gesture as a sign, I

he means ‘the object as the sign itself represents direct your attention to some relatively immediate

it, and whose Being is thus dependent upon the object in concrete space (indexically recoverable);

representation of it in the Sign’ (4.536, cited in and this object, or any of its features, is then used

Colapietro, 1989: 15). This is to be contrasted as a sign to direct your attention to some relatively

with the ‘dynamic object’, which Peirce takes to distal object in abstract space (inferentially recov-

be ‘the Reality which by some means contrives to erable). In other words, the first sign (whatever

determine the Sign to its Representation’ (ibid.). initially points) is a ‘way marker’ in a relatively

In short, the dynamic object is the object that concrete environment; and the second sign (what-

determines the existence of the sign; and the ever is pointed to by the first sign, and subse-

immediate object is the object represented by the quently points) is a ‘way marker’ in a relatively

sign. Immediate objects only exist by virtue of abstract environment. Loosely speaking, if the first

the signs that represent them, whereas dynamic sign causes one’s head to turn, the second sign,

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 5 3/19/2010 6:48:13 PM

6 THE SAGE HANDBOOK OF SOCIOLINGUISTICS

itself the object of the first sign, causes one’s mind with propositional content, such as an assertion

to search. Relatively speaking, the first path taken (or explicit speech act more generally). Thus, to

is maximally concrete-indexical; and the second describe someone’s movement as he raised his

path taken is maximally abstract-inferential. hand, is to offer an interpretant of such a control-

Objects (2) and (4), then, are relatively fore- led behaviour (qua sign) so far as it has a purpose

grounded. They are immediate objects in Peirce’s (qua object). And hence while such representa-

sense: objects which signs represent (and hence tions are signs (that may be subsequently inter-

which exist because the sign brought some inter- preted), they are also interpretants (of prior signs).

preter’s attention to them). Objects (1) and (3) are, Finally, it should be emphasized that the same sign

in contrast, relatively backgrounded. They are can lead to different kinds of interpretants – some-

dynamic objects: objects which give rise to the times simultaneously and sometimes sequentially.

existence of signs (and hence which are causes of, For example, upon being exposed to a violent

or reasons for, the signer having expressed them). image, one may blush (affective interpretant),

In other words, whenever someone directs our avert one’s gaze (energetic interpretant), or say

attention there are two objects: as a foregrounded, ‘that shocks me’ (representational interpretant) –

immediate object, there is whatever they direct see Table 12.1 (column 5).

our attention to (2); and as a backgrounded, Finally, each of these three types of interpre-

dynamic object, there is their intention to direct tants may be paired with a slightly more abstract

our attention (1). Grice’s key insight is that, for double, known as an ultimate interpretant (cf.

a wide range of semiotic processes, my interpre- Peirce, 1955c: 277). In particular, an ‘ultimate

tant of your dynamic object is a condition for my affective interpretant’ is not a change in bodily

interpretant of your immediate object. In other state per se, but rather a disposition to have one’s

words, learning of your intention to communicate bodily state change – and hence is a disposition to

is a key resource for learning what you intend to express affective interpretants (of a particular

communicate. Loosely speaking, whereas the type). Such an interpretant, then, is not itself a

object is revealed by what the point ostends (or by sign, but is only evinced in a pattern of behaviour

what the utterance represents), the intention is (as the exercise of that disposition). Analogously,

revealed by the act of pointing (or by the act of an ‘ultimate energetic interpretant’ is a disposition

uttering). to express energetic interpretants (of a particular

type). In short, it is a disposition to behave in

_______________________ certain ways – as evinced in purposeful and non-

purposeful behaviours. And finally, an ‘ultimate

While many anthropologists are familiar with representational interpretant’ is the propositional

Peirce’s distinction between icons, indices and content of a representational interpretant, plus all

symbols, most are not familiar with his threefold the propositions that may be inferred from it,

typology of interpretants – and so these should be when all of these propositions are embodied in

fleshed out in detail. In particular, as inspired by a change of habit, as evinced in behaviour that

Peirce, there are three basic types of interpretants conforms to these propositional contents. For

(1955c: 276–7; Kockelman, 2005). An ‘affective example, a belief is the quintessential ultimate

interpretant’ is a change in one’s bodily state. It representational interpretant: in being committed

can range from an increase in metabolism to to a proposition (i.e. ‘holding a belief’), one is

a blush, from a feeling of pain to a feeling of also committed to any propositions that may be

being off-balance, from sweating to an erection. inferred from it; and one’s commitment to this

This change in bodily state is itself a sign that is inferentially articulated set of propositions is

potentially perceptible to the body’s owner, or evinced in one’s behaviour: what one is likely or

others who can perceive the owner’s body. And, as unlikely to do or say insofar as it confirms or con-

signs themselves, these interpretants may lead to tradicts these propositional contents. Notice that

subsequent, and perhaps more developed, inter- these ultimate interpretants are not signs in them-

pretants. ‘Energetic interpretants’ involve effort, selves: while they dispose one toward certain

and individual causality; they do not necessarily behaviours (affective, energetic, representational),

involve purpose, intention or planning. For exam- they are not the behaviours per se – but rather

ple, flinching at the sound of a gun is an energetic dispositions to behave in certain ways. Ultimate

interpretant; as is craning one’s neck to see what interpretants are therefore a very precise way of

made a sound; as is saluting a superior when accounting for a habitus: which, in some sense, is

she walks by; as is wielding an instrument (say, just an ensemble of ultimate interpretants as

pounding in a nail with a hammer); as is heeding embodied in an individual, and as distributed

an affordance (say, tiptoeing on a creaky floor). among members of a community (cf. Bourdieu,

And ‘representational interpretants’ are signs 1977 [1972]).

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 6 3/19/2010 6:48:13 PM

SEMIOTICS 7

While such a six-fold typology of interpretants 12.3 SOCIAL RELATIONS AND

may seem complicated at first, it should accord

with one’s intuitions. Indeed, most emotions COGNITIVE REPRESENTATIONS

really involve a complicated bundling together of

all these types of interpretants (Kockelman, Ultimate (representational) interpretants deserve

2006b). For example, upon hearing a gunshot (as further theorization. For the Boasian, Ralph Linton

a sign), one may be suffused with adrenaline (1936), a ‘status’ (as distinct from the one who

(affective interpretant); one might make a fright- holds it) is a collection of rights and responsibili-

ened facial expression (relatively non-purposeful ties attendant upon inhabiting a certain position in

energetic interpretant); one may run over to see the social fabric: i.e. the rights and responsibilities

what happened (relatively purposeful energetic that go with being a parent or child, a husband or

interpretant); and one might say ‘that scared the wife, a citizen or foreigner, a patrician or plebian,

hell out of me’ (representational interpretant). and so forth. A ‘role’ is any enactment of one’s

Moreover, one may forever tremble at the sight of status: i.e. the behaviour that arises when one puts

the woods (ultimate affective interpretant); one one’s status into effect by acting on one’s rights

may never go into that part of the woods again and according to one’s responsibilities. And, while

(ultimate energetic interpretant); and one might untheorized by Linton, we may define an ‘atti-

forever believe that the woods are filled with tude’ as another’s reaction to one’s status by

dangerous men (ultimate representational inter- having perceived one’s role. Many attitudes, then,

pretant). In this way, most so-called emotions are themselves statuses: upon inferring your status

may be decomposed into a bouquet of more basic (by perceiving your role), I adopt a complemen-

and varied interpretants. And, in this way, the tary status.

seemingly most subjective forms of experience Roles, statuses and attitudes, then, are three

are reframed in terms of their intersubjective components of the same semiotic process – map-

effects. ping onto signs, objects and interpretants, respec-

tively – see Table 12.1 (column 6). Indeed, one

_______________________ cannot perceive a status (which is just a collection

of rights and responsibilities); one can only infer

Putting all the foregoing ideas together, a set of a status from a role (any enactment of those rights

three-fold distinctions may be enumerated. First, and responsibilities); and one may therefore adopt

any semiotic process has three components: sign, an attitude towards a status. In this way, a status

object, interpretant. There are three kinds of signs may be understood in terms similar to an ultimate

(and objects): quali-, sin- and legi-. There are interpretant: a disposition or propensity to signify

three kinds of sign–object relations, or grounds: and interpret in certain ways. A role may be

iconicity (quality), indexicality (contiguity) and understood as any sign of one’s propensity to sig-

symbolism (convention). And there are three nify and interpret in particular ways – itself often

kinds of interpretants: affective, energetic and a particular mode of signifying or interpreting.

representational (along with their ultimate vari- And an attitude, qua complementary status, may

ants). Finally, Peirce’s categories of firstness, itself just be an embodied sense of what to expect

secondness and thirdness (1955b), while notori- from another, itself often an ultimate interpretant,

ously difficult to define, are best understood as where this embodied sense is evinced by being

genus categories, which include the foregoing surprised by or disposed to sanction non-expected

categories as species – see Table 12.1 (column 1). behaviours. The basic process is therefore as fol-

In particular, firstness is to secondness is to lows: we perceive others’ roles; from these per-

thirdness, as sign is to object is to interpretant, ceived roles, we infer their statuses; and from

as iconic is to indexical is to symbolic, as affective these inferred statuses, we anticipate other roles

is to energetic is to representational. Thus, from them which would be in keeping with those

firstness relates to sense and possibility; second- statuses. In short, a status is modality personified,

ness relates to force and actuality; and thirdness a role is personhood actualized, and an attitude

relates to understanding and generality. Indeed, is another’s persona internalized. Here, then, we

given that thirdness presupposes secondness, may understand social relations in terms of

and secondness presupposes firstness, Peirce’s semiotic processes.

theory assumes that human-specific modes of

semiosis (thirdness per se) are grounded in modes _______________________

of firstness and secondness. Peirce’s pragmatism,

then, is a semiotic materialism – one in which With these basic definitions in hand, several

meaning is as embodied and embedded as it is finer distinctions may be introduced, and several

‘enminded’. caveats may be established. First, Linton focused

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 7 3/19/2010 6:48:13 PM

8 THE SAGE HANDBOOK OF SOCIOLINGUISTICS

on rights and responsibilities, with no indication expressing certain desires to espousing certain

of how these were to be regimented. For present beliefs. More generally, a role can be any sign that

purposes, the modes of permission and obligation one gives (off) for others to interpret, and any inter-

that make up a status may be regimented by any pretant of the signs others give (off).

number of means: while typically grounded in Just as statuses are no more mysterious than

norms (as commitments and entitlements), they any other object, attitudes are no more mysterious

may also be grounded in rules (as articulated than any other interpretant. Hence attitudes may

norms) or laws (as legally-promulgated and be affective interpretants (blushing when you

politically-enforced rules). learn your date used to be a porn star), energetic

While the three classic types of status come interpretants (reaching for your pistol when you

from the politics of Aristotle (husband/wife, learn your date is a bounty hunter), or representa-

master/slave, parent/child), statuses are really tional interpretants (saying ‘you can’t be serious’

much more varied and much more basic. For when your date makes his or her intentions known).

example, kinship relations involve complementary In particular, attitudes may themselves be ultimate

statuses: aunt/niece, father-in-law/daughter-in-law, interpretants, and hence statuses: i.e. my status

and so forth. Positions in the division of labour might be regimented by others’ attitudes towards

are statuses: spinner, guard, nurse, waiter, etc. my status, which are themselves just statuses.

Positions within civil and military organizations Given that others may use any sign or interpre-

are statuses: CEO, private, sergeant, secretary. tant that one expresses as a means to infer one’s

Goffman’s ‘participant roles’ (1981) are really status, and given that one inhabits a multitude of

statuses: speaker and addressee; participant and constantly changing statuses, there is much ambi-

bystander. What Marx called the ‘dramatis perso- guity: not only does the same person inhabit many

nae’ of economic processes (1967: 113) are also statuses and many persons inhabit the same status

statuses: buyer and seller, creditor and debtor, but also many different roles can indicate the

broker and proxy. Social categories of the more same status and the same role can indicate many

colourful kind are statuses: geek, stoner, slut, bon different statuses. For these reasons, the idea of

vivant, as are social categories of the more politi- an ‘emblematic role’ should be introduced. For

cal kind: male, black, Mexican, rich, gay. Finally, example, wearing a uniform (say, that of a ser-

and quite crucially, any form of possession is a geant in the army) is probably the exemplary

status: one has rights to, and responsibilities for, emblematic role. It is minimally ambiguous and

the possession in question: i.e. to own a home (qua maximally public. Members of a status have it in

use-value), or have $50.00 (qua exchange-value), common; it contrasts them with members of other

is a kind of status. statuses; and members of all such statuses are

Just as the notion of status can be quite compli- conscious of this contrastive commonality. It may

cated, so can the role that enacts it. In particular, a only and must always be worn by members of a

role can be any normative practice – and hence certain status. And finally, it provides necessary

anything that one does or says, any sign that one and sufficient criteria for inferring that the bearer

purposely gives or unconsciously gives off (cf. has the status in question – see Table 12.3. While

Goffman, 1959). It may range from wearing a most statuses don’t come with uniforms, they

particular kind of hat to having a particular style nonetheless have relatively emblematic roles – or

of beard, from techniques of the self to regional roles which satisfy some, but not all, of these

cooking, from standing at a certain point in a soccer criteria.

field to sitting at a certain place at a dinner table, In addition to emblematic roles, there are sev-

from deferring judgment to a certain set of people to eral other key means by which statuses are distin-

praying before certain icons, from having various guished, perpetuated, explicated and objectified.

physical traits to partying on certain dates, from While the emphasis so far has been on the

Table 12.3 The four dimensions of relatively emblematic roles

Phenomenological A role which is maximally public (i.e. perceivable and interpretable); and a role which is

minimally ambiguous (i.e. one-to-one and onto)

Relational A role which all members of an intentional status have in common; a role by which

members of different intentional statuses contrast, and a role of which all members are

conscious

Normative A role which may (only) be expressed by members of a particular intentional status; and a

role which must (always) be expressed by members of a particular intentional status

Epistemic A role which provides necessary and sufficient criteria for inferring (and/or ascribing) the

intentional status in question

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 8 3/19/2010 6:48:13 PM

SEMIOTICS 9

commitments and entitlements that constitute a extended to cover mental states – or what might

particular status, this is merely the substance of a best be called ‘intentional statuses’ – as particular

status: what anyone who holds that status has in kinds of ultimate (representational) interpretants.

common with others who hold that status. As For example, believing it will rain, or intending to

implicit in Linton’s definition, any status is also go to the store, or remembering that one had

defined by its contrast to other statuses (its com- bacon for breakfast can each be understood as an

mitments and entitlements in relation to their inferentially articulated set of commitments and

commitments and entitlements): husband versus entitlements to signify and interpret in particular

wife, parent versus child, etc. And finally, though ways: normative ways of speaking and acting

not remarked upon by Linton, anyone who inhabits attendant upon being a certain sort of person – a

a status usually has a second-order, or ‘reflexive’ believer that the earth is flat, or a lover of dogs. A

understanding of this contrastive commonality – role is just any enactment of that status: actually

typically called self-consciousness. These are putting one or more of those commitments and

often structured as stereotypes, and they may be entitlements into effect; or speaking and acting in

the crucial locus for the expectations underlying a way that conforms with one’s mental states. And

other’s behaviour: he must be a waiter, because an attitude is just another’s interpretant of one’s

he has a stereotypic sign of being a waiter; and mental state by way of having perceived one’s

if he is a waiter, then he should behave in further roles: I know you are afraid of dogs, as a mental

stereotypic ways – not so much grounded in state, insofar as I have seen you act like someone

commitments and entitlements, as similar to some afraid of dogs; and as a function of this knowledge

culturally-circulating exemplar or prototype of a (of your mental state through your role), I come to

waiter. expect you to act in certain ways – and perhaps

In short, a status should be defined as a collec- sanction your behaviour as a function of those

tion of commitments and entitlements to signify expectations (where such sanctions are often

and interpret in particular ways; a role should be the best evidence of my attitude towards your

defined as any mode of signification or interpreta- mental state).

tion that enacts these commitments and entitlements; The real difference, then, between social statuses

and an attitude should be defined as any interpre- and mental states, is that mental states are inferen-

tant of a status through a role – usually itself tially articulated (their propositional contents

another status. Here, then, is where modality stand in logical relation to other propositional

(entitlement and commitment) is most intimately contents) and indexically articulated (their propo-

tied to meaning (signification and interpretation). sitional contents stand in causal relation to states

It should be emphasized, then, that the defini- of affairs). For example, and loosely speaking:

tion of status being developed here should not be beliefs may logically justify and be logically justi-

confused with the folk-sociological understanding fied by other beliefs; perceptions may logically

of status as relative prestige, qua ‘high status’ and justify beliefs and be indexically caused by states

‘low status’. Moreover, the definition of role being of affairs; and intentions may be logically justified

developed here should not be confused with the by beliefs and be indexically causal of states of

folk-sociological sense of ‘status symbols’. affairs (Brandom, 1994; Kockelman, 2006c).

Table 12.4 orders what are perhaps the five most

_______________________ basic mental states as a function of their prototypic

inferential and indexical articulation: memory,

So far the discussion has been about social perception, belief, intention and plan.

statuses as particular kinds of object, or ultimate Finally, there are relatively emblematic roles of

interpretants. However, the entire analysis can be mental states: behaviours (such as facial expression

Table 12.4 Inferential and indexical articulation of intentional statuses

Couched as semiotic process Observation Assertion Action

Couched as mode of commitment Empirical Epistemic Practical

Couched as mental state Memory Perception Belief Intention Plan

Stand as reason × × ×

Stand in need of reason × × ×

Caused by state of affairs × ×

Causal of state of affairs × ×

Non-displaced causality × ×

Displaced causality × ×

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 9 3/19/2010 6:48:13 PM

10 THE SAGE HANDBOOK OF SOCIOLINGUISTICS

and speech acts) which provide relatively incon- signs that humans are singularly adept at tracking.

trovertible evidence of one’s mental state. This And so-called ‘theory of mind’ is really just a

means that the so-called privateness of mental particular mode of the ‘interpretation of signs’.

states is no different from the privateness of social More generally, the attitudes of others towards

statuses: each is only known through the roles that our social statuses and mental states are evinced in

enact them, and only incontrovertibly known their modes of interacting with us: they expect

when these roles are emblematic. Such a fact is certain modes of signification and interpretation

captured in the phrase to wear one’s heart on from us (as a function of what they take our social

one’s sleeve. As we will take up in detail, speech statuses and mental states to be); and they sanc-

acts such as I believe it’s going to rain are rela- tion certain modes of signification and interpreta-

tively emblematic signs of both the propositional tion from us (as a function of these expectations).

mode (belief) and the propositional content (that Thus, we perceive others’ attitudes towards our

it’s going to rain). Moreover, the so-called subjec- social statuses and mental states in their modes of

tivity of mental states arises from the fact that interacting with us (just as we perceive others’

they may fail (normatively speaking) to be logi- social statuses and mental states by their patterns

cally justified (or logically justifying), and they of behaviour). In this way, if one wants to know

may fail (normatively speaking) to be indexically where social statuses and mental states reside, or

causal (or indexically caused). There are non- where ultimate (representational) interpretants are

sated intentions, false beliefs, invented memories, embodied and embedded, the answer is as

non-veridical perceptions, plans that fall through, follows: in the sanctioning practices of a sign-

and so forth. In short, mental states have been community, as embodied in the dispositions of its

theorized from the standpoint of social statuses, members, and as regimented by reciprocal atti-

on the one hand, and speech acts, on the other. tudes towards each others’ social statuses and

This is the proper generalization of Peirce’s mental states (as evinced in each other’s roles). If

understanding of ultimate representational inter- you think this is circular, you’re right; if you think

pretants – when grounded in a wider theory of circularity is bad or somehow avoidable, you’re

sociality and linguistics. wrong. Indeed, if there is any sense to the slogan

meaning is public, this is it.

_______________________

Another way to characterize all these ultimate 12.4 PERFORMATIVITY REVISITED:

(representational) interpretants is as ‘embodied

signs’. In particular, ultimate (representational) SEMIOTIC AGENTS AND

interpretants, and mental states and social statuses GENERALIZED OTHERS

more generally, have the basic structure of semi-

otic processes: they have roots leading to them The ‘signer’ is the entity that brings a sign into

(insofar as they are the proper significant effects, being – that is, brings a sign into being (in a par-

or interpretants, of other signs); and they have ticular time and place) such that it can be inter-

fruits following from them (insofar as they give preted as standing for an object, and thereby give

rise to modes of signifying and interpreting, or rise to an interpretant. It is often accorded a maxi-

roles, that may be interpreted by others’ attitudes). mum sort of agency, such that not only does it

The key caveat is that the mental state or social control the expression of a sign but also it com-

status itself is non-sensible or ‘invisible’: one poses the sign–object relation, and commits to

knows it only by its roots and fruits, the sign and the interpretant of that relation. As will be used

interpretant events that lead to it and follow from here, to control the expression of a sign, means to

it. For example, any number of sign events may determine its position in space and time. Loosely

lead to the belief that it will rain tomorrow (you speaking, one determines where and when a sign

hear it on TV, your farmer friend tells you, the sky is expressed. To compose the relation between a

has a certain colour, you hear the croaking of the sign and an object means to determine which sign

toads, etc.), and any number of sign events may stands for the object and/or which object is stood

follow from the belief it will rain tomorrow (you for by the sign. Loosely speaking, one determines

shut the windows, you tell your friends, you buy what a sign expresses and/or how this is expressed.

an umbrella, you take in the washing, etc.). Thus, To commit to the interpretant of a sign–object

intentional statuses are inferentially and indexi- relation, means to determine what its interpretant

cally articulated: they may logically lead to and will be. This means being able to anticipate what

follow from other intentional statuses; and they the interpreter will do – be the interpreter the

may causally lead to and follow from states of signer itself (at one degree of remove), another

affairs. In this way, so-called ‘mental states’ may (say, someone other than the signer), or ‘nature’

be understood as complex kinds of embodied (in the case of regimentation by natural causes

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 10 3/19/2010 6:48:13 PM

SEMIOTICS 11

rather than by cultural norms): see Table 12.1, interpretant. More carefully phrased, to commit to

column 7. Phrasing all these points about residen- the interpretant of a sign means that one is able to

tial agency in an Aristotelian idiom, the committer anticipate what sign the interpreter will express,

determines the end, the composer determines the where this anticipation is evinced in being surprised

means, and the controller determines when and by and/or disposed to sanction, non-anticipated

where the means will be wielded for the end. In interpretants. Mead (1934), for example, made a

this way, one may distinguish between ‘undertaker- famous distinction between the gestural and the

based agency’ (control: when and where), ‘means- symbolic (and see Vygotsky, 1978). In particular,

based agency’ (composition: what and how), and he says that

‘ends-based agency’ (commitment: why and to

what effect). The vocal gesture becomes a significant symbol …

Notice, then, that there are three distinguishable when it has the same effect on the individual

components of a signer (controller, composer and making it that it has on the individual to whom

committer), corresponding to three distinguisha- it is addressed or who explicitly responds to it,

ble components of a semiotic process (sign, object and thus involves a reference to the self of the

and interpretant). When the sign involves verbal individual making it. (Mead, 1934: 46)

behaviour, and the signer controls, composes and

commits, the signer is usually called a ‘speaker’. That is, for Mead, symbols are inherently self-

And when the sign involves non-verbal behaviour, reflexive signs: the signer can anticipate another’s

and the signer controls, composes and commits, interpretant of a sign insofar as the signer can

the signer is usually called an ‘actor’. In both stand in the shoes of the other, and thereby expect

cases, responsibility for some utterance or action – and/or predict the other’s reaction insofar as they

some ‘word’ or ‘deed’ – is usually assigned as a know how they themself would respond in a simi-

function of the degree to which the signer con- lar situation. In this way, the symbolic for Mead is

trols, composes and commits. And, as a function the realm of behaviour in which one can seize

of this responsibility, the signer may be rewarded control of one’s appearance – and thereby act

or punished, praised or blamed, held accountable for the sake of others’ interpretants. For example,

or excused, and so on. in Mead’s terms, using a hammer to pound in a

One understanding of agency would locate it at nail is gestural, whereas wielding a hammer to

the intersection of these dimensions of control, (covertly) inform another of one’s purpose (rather

composition and commitment. In particular, it than, or in addition to, driving a nail through a

may be shown that each of these three dimensions, board) is symbolic.

or roles, is not usually simultaneously inhabited Crucially, while Mead’s distinction between

by identical, individual, human entities. For exam- the gestural and the symbolic relates to Peirce’s

ple, the signer need not an individual (nor need be distinction between index and symbol, they should

any of its individual components – controller, not be confused. Moreover, Mead’s terms should

composer, committer). It may be some less than or not be confused with the everyday meaning of

larger than individual entity – say, a super-individ- gesture (say, in comparison to verbal language).

ual (e.g. a nation-state) or a sub-individual (e.g. Indeed, for Mead, the features of a semiotic proc-

the unconscious). The signer need not be human. ess that really contribute to its being a symbol

It may be any sapient entity (e.g. a rational adult rather than a gesture are whether the ground (or

person or an alien life form with something like sign–object relation) is symbolic rather than

natural language), sentient entity (e.g. a dog or indexical, and whether the sign is symmetrically

fish), responsive entity (e.g. a thermostat or pin- accessible to the signer’s and interpreter’s senses:

wheel), or even the most unsapient, unsentient and i.e. signs with relatively conventional grounds

unresponsive entity imaginable (e.g. rocks and (in Peirce’s sense) are more likely to be symbols

sand as responsive only to gravity and entropy). (in Mead’s sense); and signs with relatively

More generally, these signers may be distributed indexical grounds (in Peirce’s sense) are more

in time (now or then), space (here or there), unity likely to be gestures (in Mead’s sense). And by

(super-individual or sub-individual), individual symmetric is meant that the sign appears to the

(John or Harry), entity (human or non-human) and signer and interpreter in a way that is sensibly

number (one or several). In this way, agency identical: both perceive (hear, see, smell, touch)

involves processes which are multi-dimensional, the sign in a relatively similar fashion. For exam-

by degrees, and distributed. Accountability scales ple, spoken language is relatively symmetric and a

with the degree of agency one has over each of facial expression is relatively asymmetric, with

these dimensions. sign language being somewhere in the middle.

For the moment, it is enough to focus on the (Mirrors are one of the ways we endeavour to

last of these three dimensions. By ‘commitment’ make symmetric relatively asymmetric signs.)

is meant that a signer can ‘internalize’ another’s In short, taking Mead’s cues, semiotic processes

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 11 3/19/2010 6:48:13 PM

12 THE SAGE HANDBOOK OF SOCIOLINGUISTICS

whose signs are relatively symmetric, and whose • cases where our own attitudes take us to have

grounds are relatively symbolic, are easier to statuses the attitudes of others don’t;

commit to than semiotic processes whose signs • and cases where neither our own attitudes,

are relatively asymmetric, and whose grounds are nor the attitudes of others, take us to have

relatively iconic-indexical. And commitment is statuses we seem to have (insofar as our

crucial because it allows for self-reflexive semio- behaviour evinces it as a regularity, though per-

sis, in which a signer has internalized – and hence haps not a norm).

can anticipate – the interpretants of others. Some senses of the term ‘unconscious’ turn on

Commitment, then, is fundamental to reflexivity exactly these kinds of discrepancies.

as a defining feature of selfhood.

As used here, an addressed semiotic process is _______________________

one whose interpretant a signer commits to, and

one whose sign is expressed for the purpose of Each individual has many statuses, and each of

that interpretant. Address may be overt or covert these statuses is regimented via the attitudes of

depending on whether or not the interpreter is different sets of others (cf. Mead, 1934; Linton,

meant to (or may easily) infer the signer’s commit- 1936). Usually, these sets are institution-specific

ment and purpose. These distinctions (committed (indeed, this is one of the key criteria of any insti-

and non-committed, addressed and non-addressed, tution). For example, as a mother, my status is

overt and covert) cross-cut pre-theoretical distinc- regimented by the attitudes of my children, my

tions such as Mead’s distinction between ‘gesture’ husband, the babysitter, several close friends,

and ‘symbol’ (1934), and Goffman’s distinction my own parents, and so forth. As a bank-teller, my

between signs ‘given’ and signs ‘given off’ (1959). status is regimented by the attitudes of my boss,

Needless to say, the ability to commit to an inter- my co-workers, my customers, and so forth. As a

pretant of a sign – and thereby address one’s thirds shortstop (baseball fielder), my status is regi-

and/or dissemble with one’s addressed thirds – mented by the attitudes of the pitcher, the base-

turns on relatively peculiar cognitive properties of men, the fielders, the batter, the fans, and so forth.

signers, social properties of sign communities and As someone committed to the claim that you had

semiotic properties of signs. ice-cream for dessert last night, my status is regi-

Just as one can commit to others’ interpretants mented by your attitude (insofar as you just

of one’s signs, one can commit to others’ attitudes informed me of this), and perhaps the attitudes of

towards one’s roles: i.e. one can anticipate what any other participants in the speech event, and so

attitude the interpreter will adopt, where this antici- forth. And, within each of these institutions, my

pation is evinced in being surprised by and/or attitudes regiment the statuses of my children and

disposed to sanction, non-anticipated attitudes. In husband, my boss and customers, my basemen

a Meadian or Vygotskian idiom, one can ‘internal- and batters, the participants in our speech event. In

ize’ another’s attitude (towards one’s status). And, short, for each of our statuses, there is usually a

in cases of self-reflexive semiosis, where this set of others whose attitudes regiment it, and

other is oneself, one can self-sanction one’s own whose statuses our attitudes help regiment. The

behaviour as conforming or not with one’s status. speech event is perhaps the minimal generalized

This is, of course, a crucial aspect of selfhood. other: a speaker and an addressee, each regiment-

For the moment, it should be noted that it is ing the social statuses and mental states of the

both a relatively human-specific and a relatively other; what we mutually know about each other

sign-specific capability. In particular, it seems that given the immediate context; what we mutually

only humans, and only humans at a particular age, know about each other given the ongoing dis-

can commit to others’ attitudes (i.e. affect certain course; and what we mutually know about each

roles such that others will take them to have cer- other given our shared culture.

tain statuses as evinced in these others’ attitudes); In cases where one has committed to the regi-

and this commitment is differentially possible as a menting attitudes of sets of others towards one’s

function of what kind of role, and hence sign, is status (within some institution), the sets of com-

being committed to (e.g. relatively symbolic mitted to (or ‘internalized’) attitudes may be

semiotic processes are easier to commit to than called a ‘generalized other’, loosely following

relatively indexical semiotic processes, and Mead’s famous definition (1936: 154). (Indeed,

emblematic roles are relatively easy to commit to we can say that a status is that to which all atti-

almost by definition). Indeed, this relative ability tudes conditionally relate.) Most of us have an

to commit to others’ attitudes may lead to three infinity of generalized others, some being wide

sorts of discrepancies: enough to encompass all of humanity (say, our

status as a person – at least we hope so), some

• cases where the attitudes of others take us to being so narrow as to encompass only our lovers

have statuses our own attitudes don’t; (say, as holding a certain awkward desire that we

5434-Wodak-Chap-12.indd 12 3/19/2010 6:48:13 PM

SEMIOTICS 13

have shyly informed them of). And sometimes we set of attitudes of others which one himself

have statuses, as regimented by the attitudes of assumes’ (1934: 175). That is, the me is the status

others, that we have not internalized. These form of the self as regimented by the attitudes of some

part of what may be called our unconscious self. generalized other. And the I is the role of the self

These questions – of different kinds of multiply that transforms the generalized other. Or, in the

overlapping generalized others, and of conscious idiom introduced above – a semiotic and temporal

and unconscious selves (via committed to and reading of Linton, Mead and Austin – the me is

uncommitted to, or internalized and uninternal- the self as appropriating, having taking into

ized attitudes) – are crucial for understanding account others’ attitudes towards its social and

agency and selfhood. Here, then, the true impor- intentional statuses; and the I is the self as effect-

tance of emblematic roles comes to the fore: they ing, enacting social and intentional roles that

are our best means of securing mutual recogni- change others’ attitudes.

tion, or rather intersubjective attitudes.

_______________________

NOTE

Putting all these ideas together we may revisit

Austin’s understanding of performativity. For a 1 This essay is a highly abridged and slightly

sign event to be felicitous it must be appropriate in extended version of Kockelman, P. (2005) ‘The

context and effective on context. And sign events semiotic stance’, which appeared in Semiotica,

are only appropriate insofar as participants already 157(1): 233–304.

have certain social statuses and mental states (or

in which a space of intersubjectively recognized

commitments and entitlements is already in place),

and are only effective insofar as participants come REFERENCES

to have certain social statuses and mental states

(or by which a change in the space of intersubjec- Austin, J. L. (2003 [1955]). How to do things with words.

tively recognized commitments and entitlements 2nd edn. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

takes place). Thus, just as we comport within a Bourdieu, P. (1977 [1972]) Outline of a theory of practice.

given space of commitments and entitlements, our Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.