Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Canadian English PDF

Canadian English PDF

Uploaded by

Smith AldanaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Grammar of The Sicilian LanguageDocument220 pagesGrammar of The Sicilian LanguageAaron Caldiero100% (1)

- English 10 Curriculum MapDocument14 pagesEnglish 10 Curriculum MapChristi Garcia Rebucias100% (3)

- Against the Current: The Remarkable Life of Agnes Deans CameronFrom EverandAgainst the Current: The Remarkable Life of Agnes Deans CameronNo ratings yet

- Canada - A Linguistic ReaderDocument241 pagesCanada - A Linguistic Readerمنیر ساداتNo ratings yet

- Brathwaite - History of The VoiceDocument52 pagesBrathwaite - History of The VoiceZachary Hope100% (1)

- Brathwaite HistoryoftheVoiceDocument45 pagesBrathwaite HistoryoftheVoicealmariveraNo ratings yet

- The Complete Book of Dutch-ified English: An ?Inwaluable? Introduction to an ?Enchoyable? Accent of the ?Inklish Lankwitch?From EverandThe Complete Book of Dutch-ified English: An ?Inwaluable? Introduction to an ?Enchoyable? Accent of the ?Inklish Lankwitch?No ratings yet

- Useful Phrases For Toefl Independent WritingDocument2 pagesUseful Phrases For Toefl Independent WritingEmeritta Tshoopara100% (1)

- Capital, Punctuation, Affixes QUIZDocument2 pagesCapital, Punctuation, Affixes QUIZFherlyn FaustinoNo ratings yet

- The 90sDocument26 pagesThe 90sMolean GaudiaNo ratings yet

- Loyal To The Crown: A Truly Distinct, Independent American Version of EnglishDocument4 pagesLoyal To The Crown: A Truly Distinct, Independent American Version of EnglishSilvina LeonNo ratings yet

- Writing between the Lines: Portraits of Canadian Anglophone TranslatorsFrom EverandWriting between the Lines: Portraits of Canadian Anglophone TranslatorsNo ratings yet

- Peer To Pier Conversations With Fellow TravelersDocument12 pagesPeer To Pier Conversations With Fellow TravelersDu Ho DucNo ratings yet

- History of Canadian EnglishDocument5 pagesHistory of Canadian EnglishIon PopescuNo ratings yet

- New Literatures in EnglishDocument22 pagesNew Literatures in EnglishKamal Suthar100% (1)

- Found PoemDocument5 pagesFound Poempoiu0987No ratings yet

- TTMC Translation of Creole in Caribbean English Literature The Case of Oonya KempadooDocument35 pagesTTMC Translation of Creole in Caribbean English Literature The Case of Oonya KempadoobibliotecafadelNo ratings yet

- Writers and Their Milieu: An Oral History of Second Generation Writers in English, Part 2From EverandWriters and Their Milieu: An Oral History of Second Generation Writers in English, Part 2Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Aboriginality: The Literary Origins of British Columbia, Volume 3From EverandAboriginality: The Literary Origins of British Columbia, Volume 3Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Conversation With Julia AlvarezDocument9 pagesConversation With Julia AlvarezThe EducatedRanterNo ratings yet

- World Literature ReportDocument10 pagesWorld Literature ReportAyaNo ratings yet

- M. Nourbese Philip - Frontiers - Selected Essays and Writings On Racism and Culture 1984-1992 (1992, Mercury Press) - Libgen - LiDocument292 pagesM. Nourbese Philip - Frontiers - Selected Essays and Writings On Racism and Culture 1984-1992 (1992, Mercury Press) - Libgen - LiTorrin SutherlandNo ratings yet

- Specific Features of Canadian English - Course - AssignmentDocument6 pagesSpecific Features of Canadian English - Course - AssignmentNevena HalevachevaNo ratings yet

- Jean Rhys's Historical Imagination: Reading and Writing the CreoleFrom EverandJean Rhys's Historical Imagination: Reading and Writing the CreoleNo ratings yet

- Americanizing Immigrants WSDocument1 pageAmericanizing Immigrants WSmrwagenbergNo ratings yet

- British Columbia Nova Scotia: A Unique DialectDocument6 pagesBritish Columbia Nova Scotia: A Unique DialectМарія ГалькоNo ratings yet

- "Am Here": Am I? (I, Hope, So.) - Bino A. RealuyoDocument6 pages"Am Here": Am I? (I, Hope, So.) - Bino A. RealuyoApril SesconNo ratings yet

- Portfolio 1.0.Document5 pagesPortfolio 1.0.Ederson VillarealNo ratings yet

- Writing to Cuba: Filibustering and Cuban Exiles in the United StatesFrom EverandWriting to Cuba: Filibustering and Cuban Exiles in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Canadian LiteratureDocument12 pagesCanadian Literatureapi-250327327No ratings yet

- Washington Irving ThesisDocument8 pagesWashington Irving Thesiskarenharkavyseattle100% (2)

- BRITISH-AMERICAN LANGUAGE DICTIONARY - For More Effective Communication Between Americans and BritonsDocument201 pagesBRITISH-AMERICAN LANGUAGE DICTIONARY - For More Effective Communication Between Americans and BritonsFrancesco Atzori100% (2)

- Contemporary Irish PoemsDocument35 pagesContemporary Irish PoemsRoger ValentineNo ratings yet

- Walk the Barrio: The Streets of Twenty-First-Century Transnational Latinx LiteratureFrom EverandWalk the Barrio: The Streets of Twenty-First-Century Transnational Latinx LiteratureNo ratings yet

- A Thanksgiving Story and Why People Speak English in The USADocument5 pagesA Thanksgiving Story and Why People Speak English in The USADusan StojsinNo ratings yet

- Transported Varieties 2Document71 pagesTransported Varieties 2Kritika RamchurnNo ratings yet

- History of English Canadian EnglishDocument17 pagesHistory of English Canadian EnglishsulfikarNo ratings yet

- What's Your English?: Varieties of English Around The WorldDocument2 pagesWhat's Your English?: Varieties of English Around The WorldMichelle YlonenNo ratings yet

- Dialnet LanguageAndJamaicanLiterature 7724714Document14 pagesDialnet LanguageAndJamaicanLiterature 7724714Jedidiah GrovesNo ratings yet

- Canadian EnglishDocument4 pagesCanadian EnglishMery AloyanNo ratings yet

- Spread of English Beyond The British IslesDocument26 pagesSpread of English Beyond The British IslesPamNo ratings yet

- Lexical Differences Between American and British English: A Survey StudyDocument15 pagesLexical Differences Between American and British English: A Survey StudyStefania TarauNo ratings yet

- Translating The Culture: by Linda White, Assistant Coordinator Thomas Mcclanahan, PH.D., PresidentDocument4 pagesTranslating The Culture: by Linda White, Assistant Coordinator Thomas Mcclanahan, PH.D., PresidentjackitoKopNo ratings yet

- Aguinaldos: Christmas Customs, Music, and Foods of the Spanish-speaking Countries of the AmericasFrom EverandAguinaldos: Christmas Customs, Music, and Foods of the Spanish-speaking Countries of the AmericasNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document8 pagesModule 1irish adla0wanNo ratings yet

- Myth, Symbol, and Colonial Encounter: British and Mi'kmaq in Acadia, 1700-1867From EverandMyth, Symbol, and Colonial Encounter: British and Mi'kmaq in Acadia, 1700-1867Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- TT3. Reading IiiDocument4 pagesTT3. Reading IiiMaria Caroline SamodraNo ratings yet

- Reyburn 1999 My Pilgrimage in MissionDocument3 pagesReyburn 1999 My Pilgrimage in MissionZaynab GatesNo ratings yet

- 7 Language and ClassDocument38 pages7 Language and ClassGrace JeffreyNo ratings yet

- Americans All Stories of American Life of To-DayFrom EverandAmericans All Stories of American Life of To-DayNo ratings yet

- Remedial Class-Activity #3 - Adverb - Joseth PasaloDocument4 pagesRemedial Class-Activity #3 - Adverb - Joseth PasaloJosethNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 (Present Indicatives)Document4 pagesChapter 5 (Present Indicatives)Dummy AccountNo ratings yet

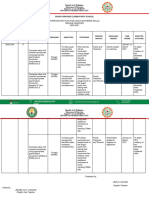

- Department of Education Region III Schools Division of Zambales District of SubicDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education Region III Schools Division of Zambales District of SubicLarriie May SaleNo ratings yet

- IX. Uluslararası Hititoloji Kongresi Bildiri KitabıDocument43 pagesIX. Uluslararası Hititoloji Kongresi Bildiri KitabıBir Arkeoloji ÖğrencisiNo ratings yet

- ALBARACIN - Teaching Reading and WritingDocument57 pagesALBARACIN - Teaching Reading and WritingJessaMae AlbaracinNo ratings yet

- Bahan Ajar AnnouncementDocument7 pagesBahan Ajar AnnouncementJumanNo ratings yet

- Word-Formation: Group 3Document9 pagesWord-Formation: Group 3Juwita SariNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarter Intervention Plan For Least Mastered Skills English 5 S.Y 2019 2020Document3 pages2nd Quarter Intervention Plan For Least Mastered Skills English 5 S.Y 2019 2020Xsob LienNo ratings yet

- Nouns - Intro.Document1 pageNouns - Intro.Riyas JalalNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Explanation Text For HighSchool StudentsDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Explanation Text For HighSchool StudentsMy EducationNo ratings yet

- Handle Meetings With Confidence: ElementaryDocument5 pagesHandle Meetings With Confidence: ElementaryislamNo ratings yet

- Carretero Jackeline 233429885 Diagnostic-Results Reading 05012021Document17 pagesCarretero Jackeline 233429885 Diagnostic-Results Reading 05012021api-517983133No ratings yet

- Linguistic Modality in Ghanaian President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo's 2017 Inaugural AddressDocument9 pagesLinguistic Modality in Ghanaian President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo's 2017 Inaugural AddressKwabena Antwi-KonaduNo ratings yet

- Part 2 - Reading: English Language Final Exam - A1Document3 pagesPart 2 - Reading: English Language Final Exam - A1Hernan SantosNo ratings yet

- PPC PPS PPDocument15 pagesPPC PPS PPkarla AtaurimaNo ratings yet

- Basic English II BookletDocument72 pagesBasic English II BookletJonathan RodriguezNo ratings yet

- How To Say I Love You in 100 LanguagesDocument4 pagesHow To Say I Love You in 100 LanguagesRosca MariusNo ratings yet

- IELTS - Speaking Band DescriptorsDocument1 pageIELTS - Speaking Band DescriptorsIngrid FaberNo ratings yet

- Unit 10 Knowing A Second LanguageDocument4 pagesUnit 10 Knowing A Second LanguageNhật Minh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Variation in Child Language by J L RobertsDocument7 pagesVariation in Child Language by J L RobertsNandini1008No ratings yet

- Teacher's Manual - Phonics: Letter SoundsDocument21 pagesTeacher's Manual - Phonics: Letter SoundsPriya ChandranNo ratings yet

- Fola Final PassDocument6 pagesFola Final PassJovie EsguerraNo ratings yet

- English I Lesson Plan - DetailedDocument10 pagesEnglish I Lesson Plan - DetailedAdriyel Mislang SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Focus Teacher's BookDocument7 pagesFocus Teacher's BookViktória Iskum100% (1)

- Arabic Awakened Prospectus 21-22Document25 pagesArabic Awakened Prospectus 21-22Januhu ZakaryNo ratings yet

- Cause: The Game Was Cancelled Caused by Torrential RainDocument3 pagesCause: The Game Was Cancelled Caused by Torrential RainSam SmithNo ratings yet

Canadian English PDF

Canadian English PDF

Uploaded by

Smith AldanaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Canadian English PDF

Canadian English PDF

Uploaded by

Smith AldanaCopyright:

Available Formats

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English

Sarah Elaine Eaton, M.A., University of Calgary

Paper presented at the

Workshop on teaching English as a Foreign Language (WEFLA), 1998

Universidad de Holguín, Cuba

The inspiration for this paper comes from a regular column called “Our Home and Native

Tongue”1 written by Bill Casselman in the magazine Canadian Geographic. I have long been

drawn to languages, their history, etymology, and idiosyncrasies. As an undergraduate, I

studied English (and later Spanish) literature, but it was not until my second year of

university that I became consciously aware that Canadian English is not simply a hybrid of

British and American English.

This revelation was brought on by a relatively obscure book entitled Wordstruck. It had been

recommended by my poetry professor at Saint Mary’s University, where I was a second-year

English major. It was not a textbook or an obligatory reading, but rather it was deemed one of

those books that would affect one in such a way that you’d never be the same person again

after having read it.

Wordstruck was written by Robert MacNeil, a writer about whom I knew nothing. The book

is his personal, conscientious and analytical recollection of how he learned English —

specifically, Canadian English.

I felt an immediate bond with this writer. Like me, he grew up on the East coast of Canada in

the city of Halifax. Like me he had a mother conscious of her British roots and attempted to

teach her child more standardized pronunciation, clear enunciation and at the same time,

discouraged the use of regionalisms (known as “vulgarisms” to my mother — and Mr.

MacNeil’s). At the same time, we kept some British constructions, such as:

• “Shall we go?” instead of the more common North American “Will we go?”

• Saying “I have to go to the loo”, instead of “I have to use the bathroom.”

• The less common custom of spelling the diminutive of “mother” as “Mum”, instead

of “Mom”. (My pronunciation of the word also corresponds better with the English

spelling, as my mother abhorred the sound of her children calling her “mawm”.)

It was only after reading MacNeil’s book that I realized that I was neither alone, nor a

linguistic anomaly. A discussion arose with my classmates who were also majoring in

English. We soon came to the same conclusion — linguistically we are neither British nor

American. We are Canadian.

1 The title of this column is a reference to the beginning lines of the Canadian national

anthem, “O Canada! Our home and native land...”

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 2

This realization was somewhat of a revelation, for as a child growing up in Canada one is

trained to recognize that the Brits and the Americans spell certain words differently:

British American

colour color

favour favor

A teacher of one grade could demand that a student use only American spellings, arguing

that, “It’s more common,” or “We’re right next door to them,” or (with a certain tinge of

resignation) “Someday that’ll be the standard here too, so you might as well get used to it.”

In the next grade, a teacher could demand the use of British spelling only and would mark

any “Yankee aberrations” of the language as being wrong and reminding students that

Canada, while perhaps geographically close to the US, was in every other way closer to

Britain and its monarch. Thus the cultural — and linguistic — dichotomy of Canada. By the

time one reaches university, most professors have resigned themselves to saying, “I don’t

care which spelling you use, as long as you keep it consistent.”

Every Canadian who has travelled abroad and been mistaken for an American (and this will

undoubtedly happen at least once during any international voyage -- except perhaps in Cuba)

has no doubt experienced irritation or even anger at the charge, without necessarily being

able to articulate why. I remember two different occasions in Spain when my national

identity was questioned. The first instance was on my first day in there, as I was more or less

lost and trying to find my way to the university residence. After wandering around for almost

half an hour, being too embarrassed to try my broken Spanish on any of the Madrileños

hurrying by, I finally recognized that it was getting later and if I didn’t ask someone, I could

spend my first night in Madrid in an alley. The exchange was something like this:

- Euh... Perdone, señora, me puede dirigir al colegio Santa María de la Universidad

Complutense, por favor? (Translation: “Excuse me, ma’am, can you please direct me to Saint

Maria’s residence at the Compluentese University?”)

- Sí, sí ...

And she rattled off the directions in rapid Spanish full of rolling “r”’s and heavy “th”s. She

evidently saw my utter confusion and after explaining it three times, decided to walk with me

there. I was grateful for this and as it turned out, the residence was not far. The first question

she asked me was:

- ¿Eres inglesa? (Translation: “Are you English?”)

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 3

In a split second I decided that it wasn’t a bad thing to be English, at least not for this very

kind lady who was walking me to the place where I could finally put down my bags and

sleep.

- Euh.... no... Mi madre es inglesa. Yo soy canadiense.... (Translation: “No, my mother is

English. I am Canadian.”)

- ¡Ah! ¡De Canadá! Pensaba que eras inglesa porque me pareces un poco tímida...

(Translation: “Ah, from Canada! I thought you were English because you seem a bit timid.”)

Timid? Me? I hardly thought so! But whatever she was labelling “timid” meant, for her, in a

roundabout sort of way, “not American”. I wasn’t about to complain. We exchanged pleasant

conversation and I thanked her profusely for walking with me to the residence.

A couple of weeks later, I was in a small shop with another Canadian. The shop owner heard

us speaking English and called us, “Gringas americanas”. We were furious and replied,

- “No señor, no somos americanas. Somos canadienses.” (Translation: “No sir, we are not

American. We are Canadian.”)

- “¡Aj! ¡Es igual!” (Translation: “Same difference.”)

- “Son dos países diferentes.” (Translation: “They’re two different countries.”)

- “¡América, norteamérica, es todo igual!” (Translation: “America. North America. It’s all the

same!”)

We left the store without buying anything. Now, I can’t remember what kind of shop it was

or what we were trying to buy, or even if the shop was in Madrid, Toledo or Avila. All that I

remember is being shocked that anyone would think that “America” and “North America”

were both the same place and that there was no difference between Canada and the U.S.

The question of Canadian identity has plagued us for many years. It reached a new peak in

1995, when the French-speaking province of Québec was preparing for a referendum on

whether or not to separate from the rest of the country. The subject came up time and time

again and generated discussions on the news, in cafés, in classrooms and around the dinner

table. One of our provinces was talking about separating from the rest of the country, saying

that they are not like the rest of the country — they are different and distinct in language,

culture and identity.

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 4

This is true to some extent. Quebec is the only province where the French language, and

consequently the French Canadian culture, dominate. But then again, every region of Canada

has its distinct cultural differences:

Newfoundland

• The last province to join confederation

• Strong sense of loyalty to the English monarch

• Economically underprivileged compared to the rest of Canada

• First settlers came mainly from Ireland

• A distinct “island culture”

• Main industry is fish

• Radically different accent not found anywhere else in Canada

Maritime Region (includes Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia)

• First settlers came mainly from Scotland, Ireland, Germany, France

• Economically underprivileged compared to the rest of Canada

• Main industries are fish and coal mining

Quebec

• French is the principal language spoken

• First settlers came mainly from France

• Main industries are forestry and hydro-power

Ontario

• Home of the Parliament of the federal government; Wealthy

• Industrially well-developed

Manitoba

• Strong sense of bilingualism

• Home of the “Métis” — a racial mix of French and indigenous

• Home of the Parliament of the federal government; Wealthy

• First settlers came mainly from Iceland, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Russia, Poland,

Hungary and the Ukraine.

• Farming is a major industry

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 5

Prairie Region (Saskatchewan and Alberta)

• Strong indigenous culture

• Very little French

• Birthplace of new political parties in Canada

• Strong sense of feminism

• Less socially tolerant than other regions of the country (more racism, homophobia,

etc.)

• Wealthy region

• Major industries are petroleum, wheat farming and cattle raising

• Immigrants came mainly from Ukraine, Russia and China

• Great expanses of land

British Columbia

• Most socially progressive province

• Relaxed culture (often comparted to California)

• Most expensive province to live in

• Variety of natural resources: timber, fruit, vegetables, fish

In 1980, the province of Quebec held its first vote on whether or not to separate from the rest

of Canada and lost. Fifteen years later, in October 1995, another referendum was scheduled

to be held. A new generation of voters would decide the fate of our country. A new generation

of Canadians — mine — was faced with the question we had never before considered: What

exactly does it mean to be Canadian?

Because of the huge regional differences in our country due to its size, it is sometimes

difficult for us to identify symbols of our national identity. Of course, we have a flag. But our

current flag with the red maple leaf was only created in 1965. Before that, we used the

British Union Jack.

Yes, we have a national anthem, but “O Canada” was not made our official national anthem

until 1980. Before that, we used “God Save the Queen” and an unofficial version of “O

Canada”. When it was finally accepted in 1980, a few “minor” changes in wording were

made. The result? Not that all Canadians learned the new version. On the contrary, unless one

was an elementary or high school student at the time and had to learn the revised anthem by

singing it every day in school, many people simply didn’t bother. To this day, there are many

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 6

adult Canadians who do not know the exact words of their national anthem.2

This was evidenced earlier this year when the internationally renowned Canadian rock star

Bryan Adams mixed up the words of the anthem while singing in front of thousands of

people gathered for a national hockey game. Hockey, is one of the few things Canadians

would identify as a national symbol. The irony is that officially, hockey is not our national

sport. Lacrosse is. Many people, including many Canadians, don’t know that. Even fewer

Canadians have played it, seen it played or even know the rules of the game. Hockey, on the

other hand, is to Canada what polo is to England or what soccer is to Brazil. We go crazy

over it. The sport is broadcast from coast to coast on national television. That’s how we all

heard our famous rock star, Bryan Adams, make his embarrassing error of mixing up the

words of the current and old version of our national anthem. For anyone who missed the

hockey game on TV that night, there were replays of the mistake on the national news.

These examples must strike Cubans as strange — the idea that some people (national

“heroes” included) could mix up the words to the national anthem or that many of us don’t

know what the “official” national sport is. Does it signify ignorance and a lack of education?

Not particularly. Rather, it embodies the sense of apathy we have when it comes to who we

are as a nation. Our lack of identity is our identity. We like to think of ourselves as people

who are unassuming, apologetic and benign, people who like to blend in; who are moderate

in opinions and politics and respectful of other ways of thinking and living.

We are proud of who we are, but don’t like to talk about it. Personally, I would bet that more

Canadians would know that we have never been involved in a civil war or a revolution than

those who would know that hockey is not our national sport. Even fewer would know that we

are linguistically different from our neighbours to the south or our imperialist cousins across

the Atlantic. But we are.

2 Subsequent to writing this paper, a Canadian elementary school teacher informed me that

the national anthem is no longer sung in schools on a daily basis as once was. The reason

given is that the anthem contains the word “God”, which may be offensive to non-

believers. The anthem is therefore no longer “forced upon” children of different (or no)

faith.

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 7

Here are four characteristics of Canadian speech 3:

1) Sound shifts, especially in the middle of a word:

Sound “t” pronounced “d”:

“Alberta” is pronounced “Al-bird-a”

“Arctic” is pronounced “Ar-dic”

“bottom” is pronounced “bod-dum”

Sound “d” pronounced “j” (or soft “g” sound in English)

“Did you eat yet?” is said “Jeet jet?”

“Canadian” is pronounced “Can-a-jan”

2) Dropping of syllables in the middle or at the end of a word”

Ca na di an (4 syllables) Ca na jan (3 syllables)

for in stance (3 syllables) “frin stance” (2 syllables)

im mi grant (3 syllables) “imm grunt”(2 syllables)

Am er i can (4 syllables) “Mare can” (2 syllables)

na tio nal an them (5 syllables) “nash null an thum” (4 syllables)

3) A lack of superlatives in everyday speech. (Note that this may be more common when

Canadians speak to each other, rather than when they speak to foreigners.)

Mark Orkin notes that Canadians use “not bad” when they really mean “good” and that they

say “not good” when they really mean “quite bad” and that something that is “fair” is

expressed as being “not too bad.”

3 The individual word examples given here come from Mark Orkin’s book Canajan, eh? I

have analysed his individual word examples and categorized them in the above four

groups.

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 8

The contrast of these Canadian expressions can be contrasted to the American and British

equivalents in the following manner:

American British Canadian

great, terrific awfully good, awfully not bad

well

OK not too bad

fair

lousy, terrible not too good

awfully bad, poorly

Orkin notes the “intrusion” of the American “Great!” into Canadian English, but emphasizes

that it has been Canadianized by the sound shift of “t” to “d”, resulting in a Canadian

sounding exclamation of “Grade!”

For Canadians, the above expressions can be used adverbally or adjectivally:

“How are you today?” “Not too good. I have a cold.” (Adverb)

“How was the hockey game last night?” “Not too bad. My team won.” (Adjective)

4) The Canadian “eh?”

Orkin’s presentation of the Canadian “eh?” is superb and much would be lost by

paraphrasing his original text. Thus, the following is a direct quote (pages 35-37):

Eh? Rhymes with hay. The great Canajan monosyllable and shibboleth, ‘eh?’, is all things

to all men. Other nations may boast their interjections and interrogative expletives -

such as the Mare Can4 ‘huh?’, the Briddish 5 ‘what?’, the French ‘hein?’ - but none of

them can claim the range and scope of meaning that are encompassed by the simple

Canajan ‘eh?’. Interrogation, assertion, surprise, bewilderment, disbelief, contempt —

these are only the beginning of ‘eh?’ and already we have passed beyond the

limitations of ‘huh?’, ‘what?’ and ‘hein?’ and their pallid analogues.

4 “Mare Can” is Canadian for “American”, according to Orkin.

5 Briddish = British

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 9

To begin with, ‘eh?’ is an indicator, sure and infallable, that is one is in the presence

of an authentic Canajan speaker. Although ‘eh?’ may be met with in Briddish and

Mare Can litter choor6, no one else ‘eh?s’ his way through life as a Canajan does, nor

half so comfortably. By contrast, ‘huh?’ is a grunt; ‘what?’ foppish and affected; and

‘hein?’ nasal and querulous. Whereas ‘eh?’ takes you instantly into the speaker’s

confidence. Only ‘eh?’ is frank and open, easy and unaffected, friendly and even

intimate.

Viewed syntactically, ‘eh?’ may appear solo or as part of a set of words, in which case

it may occupy either terminal, medial or initial position. We shall consider these

briefly.

Its commonest solo use is as a simple interrogative calling for the repetition of

something either not heard because inaudible or, if heard, then not clearly understood.

In this context ‘eh?’ equals ‘What did you say?’, ‘How’s that?’ Or in Canajan, ‘Wadja

say?’, ‘Howzat?’

According to intonation, the meaning of solo ‘eh?’ may vary all the way from inquiry

(as we have seen) through doubt to incredulity. Here are a few examples:

‘I’m giving up smoking.’

‘Eh?’ (A cross between what? and oh yeah?)

‘Could you loan me two bucks7?

‘Eh?’ (Are you kidding?)

‘Here’s the two bucks I owe you.’

‘Eh?’ (I don’t believe it!)

‘Eh?’ in terminal position offers a running commentary on the speaker’s narrative, not

unlike vocal footnotes:

“I’m walking down the street, eh?” (Like this, see?)

“I’d hadda few beers en I was feeling priddy good, eh?” (You know how it is.)

“When all of a sudden I saw this big guy, eh?” (Ya see.)

“He musta weighed all of 220 pounds, eh?” (Believe me.)

6“Litter chore” is Canadian for “literature”, according to Orkin.

7 “Bucks”, slang for “dollars”.

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 10

“I could see him from a long ways off en he was a real big guy, eh?” (I’m not

fooling.)

“I’m minding my own business, eh?” (You can bet I was.)

“But this guy was taking up the whole sidewalk, eh?” (Like I mean he really was.)

“So when he came up to me I jess stepped inta the gudder, eh?” (I’m not crazy, ya

know.)

“En he went on by, eh?” (Just like that.)

“I gave up, eh?” (What else could I do?)

“Whattud you a done, eh?” (I’d like to know since you’re so smart.)

‘Eh?’ in medial position is less common and so more prized by collectors:

“We’re driving to Miami, eh? for our holidays.” (Like where else?)

“There aren’t many people, eh?, that can find their way around Oddawa8 like he

can.” (You know as well as I do.)

‘Eh?’ rarely appears in initial position. Thus, while one might ask: “N’est-ce pas qu’il

a de la chance?”, Canajans could only say, “He’s lucky, eh?”

Forners9 are warned to observe extreme caution with ‘eh?’ since nothing will give

them away more quickly than its indiscriminate use. Like the pronunciation of

Skatchwan10 (only much more so), it is a badge of Canajanism which requires half a

lifetime to learn to use with the proper panache.

8Orkin’s interpretation of how Canadians say the name of their national capital, Ottawa.

9 “Foreigners”

10 “Saskatchewan”, one of Canada’s Prairie provinces.

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 11

A teacher at Arm See11 suggested recently that ‘eh?’ is not Canajan since it may also

be found in the Knighted12 States, the You Kay 13 and Sow Thafrica14 . In the same way

sign tists 15 tried to prove that hockey was not invented in Canada, but Canajans

remain unconvinced, eh?

Thus concludes this brief study on Canadian English. Certainly, we have only begun to

scratch the surface, but if throughout the course of this short paper you have come to

understand better a few of the characteristics — even the idiosyncrasies — of Canadian

English, then that’s not to bad then, eh?

Questions or comments on this paper may be directed to:

Sarah Eaton

University of Calgary

2500 University Dr. NW

Calgary, AB, T2N 1N4

Canada

e-mail: seaton@ucalgary.ca or saraheaton2001@yahoo.ca

Bibliography

MacNeil, Robert. Wordstruck. Viking Press. New York, NY: 1989

Orkin, Mark M. Canajan, eh? General Publishing Company Ltd., Don Mills, Ontario,

Canada: 1973.

Sauvé, Virginia and Monique Sauvé. Gateway to Canada. Oxford UP, Toronto, Canada:

1997.

11“Arm See” = R.M.C, short for “Royal Military College”, a prestigious private school in

Ontario.

12 “United”

13 U. K. = United Kingdom

14 “South Africa”

15 “Scientists”

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

Canadian English: Not Just a Hybrid of British and American English 12

Responses to the question, “What is a Canadian?”

As part of my research for this paper, I interviewed a number of Canadians to understand

their sense of national identity. I asked them one simple question: “What is a Canadian?”

These are their direct answers:

“To be Canadian is to enjoy the rights and freedoms of a progressive, nonaggressive nation,

while claiming a cultural heritage from anywhere else.”

Connie (age 42)

“Someone who lives in a frozen land... um... someone who believes in some semblance of

universal health care... What else?... A weird combination of socialism and capitalism... I’m

trying to avoid saying, ‘not American’”.

Dan (age 45)

“To me, being Canadian means that when I travel, I'm proud to say I'm from Canada because

everybody seems to like Canadians and thus one generates a reasonably friendly reaction.”

Claire (age 29)

“A Canadian? Oh my gosh... What is a Canadian?... A person who lives in Canada and speaks

English and French.”

Millie (age 50)

“I don’t know what it is... I never thought of it before... It’s a person who lives in this

country. ‘My Canada includes Quebec!’”

Wendy (age 25)

“What’s a Canadian? A tolerant person... multi-cultural and conservative... humble.”

Dave (age 31)

“A person who has Canadian citizenship (whether it’s acquired at birth or from

immigrating).”

Line (36)

Sarah Elaine Eaton University of Calgary, Canada

You might also like

- Grammar of The Sicilian LanguageDocument220 pagesGrammar of The Sicilian LanguageAaron Caldiero100% (1)

- English 10 Curriculum MapDocument14 pagesEnglish 10 Curriculum MapChristi Garcia Rebucias100% (3)

- Against the Current: The Remarkable Life of Agnes Deans CameronFrom EverandAgainst the Current: The Remarkable Life of Agnes Deans CameronNo ratings yet

- Canada - A Linguistic ReaderDocument241 pagesCanada - A Linguistic Readerمنیر ساداتNo ratings yet

- Brathwaite - History of The VoiceDocument52 pagesBrathwaite - History of The VoiceZachary Hope100% (1)

- Brathwaite HistoryoftheVoiceDocument45 pagesBrathwaite HistoryoftheVoicealmariveraNo ratings yet

- The Complete Book of Dutch-ified English: An ?Inwaluable? Introduction to an ?Enchoyable? Accent of the ?Inklish Lankwitch?From EverandThe Complete Book of Dutch-ified English: An ?Inwaluable? Introduction to an ?Enchoyable? Accent of the ?Inklish Lankwitch?No ratings yet

- Useful Phrases For Toefl Independent WritingDocument2 pagesUseful Phrases For Toefl Independent WritingEmeritta Tshoopara100% (1)

- Capital, Punctuation, Affixes QUIZDocument2 pagesCapital, Punctuation, Affixes QUIZFherlyn FaustinoNo ratings yet

- The 90sDocument26 pagesThe 90sMolean GaudiaNo ratings yet

- Loyal To The Crown: A Truly Distinct, Independent American Version of EnglishDocument4 pagesLoyal To The Crown: A Truly Distinct, Independent American Version of EnglishSilvina LeonNo ratings yet

- Writing between the Lines: Portraits of Canadian Anglophone TranslatorsFrom EverandWriting between the Lines: Portraits of Canadian Anglophone TranslatorsNo ratings yet

- Peer To Pier Conversations With Fellow TravelersDocument12 pagesPeer To Pier Conversations With Fellow TravelersDu Ho DucNo ratings yet

- History of Canadian EnglishDocument5 pagesHistory of Canadian EnglishIon PopescuNo ratings yet

- New Literatures in EnglishDocument22 pagesNew Literatures in EnglishKamal Suthar100% (1)

- Found PoemDocument5 pagesFound Poempoiu0987No ratings yet

- TTMC Translation of Creole in Caribbean English Literature The Case of Oonya KempadooDocument35 pagesTTMC Translation of Creole in Caribbean English Literature The Case of Oonya KempadoobibliotecafadelNo ratings yet

- Writers and Their Milieu: An Oral History of Second Generation Writers in English, Part 2From EverandWriters and Their Milieu: An Oral History of Second Generation Writers in English, Part 2Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Aboriginality: The Literary Origins of British Columbia, Volume 3From EverandAboriginality: The Literary Origins of British Columbia, Volume 3Rating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Conversation With Julia AlvarezDocument9 pagesConversation With Julia AlvarezThe EducatedRanterNo ratings yet

- World Literature ReportDocument10 pagesWorld Literature ReportAyaNo ratings yet

- M. Nourbese Philip - Frontiers - Selected Essays and Writings On Racism and Culture 1984-1992 (1992, Mercury Press) - Libgen - LiDocument292 pagesM. Nourbese Philip - Frontiers - Selected Essays and Writings On Racism and Culture 1984-1992 (1992, Mercury Press) - Libgen - LiTorrin SutherlandNo ratings yet

- Specific Features of Canadian English - Course - AssignmentDocument6 pagesSpecific Features of Canadian English - Course - AssignmentNevena HalevachevaNo ratings yet

- Jean Rhys's Historical Imagination: Reading and Writing the CreoleFrom EverandJean Rhys's Historical Imagination: Reading and Writing the CreoleNo ratings yet

- Americanizing Immigrants WSDocument1 pageAmericanizing Immigrants WSmrwagenbergNo ratings yet

- British Columbia Nova Scotia: A Unique DialectDocument6 pagesBritish Columbia Nova Scotia: A Unique DialectМарія ГалькоNo ratings yet

- "Am Here": Am I? (I, Hope, So.) - Bino A. RealuyoDocument6 pages"Am Here": Am I? (I, Hope, So.) - Bino A. RealuyoApril SesconNo ratings yet

- Portfolio 1.0.Document5 pagesPortfolio 1.0.Ederson VillarealNo ratings yet

- Writing to Cuba: Filibustering and Cuban Exiles in the United StatesFrom EverandWriting to Cuba: Filibustering and Cuban Exiles in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Canadian LiteratureDocument12 pagesCanadian Literatureapi-250327327No ratings yet

- Washington Irving ThesisDocument8 pagesWashington Irving Thesiskarenharkavyseattle100% (2)

- BRITISH-AMERICAN LANGUAGE DICTIONARY - For More Effective Communication Between Americans and BritonsDocument201 pagesBRITISH-AMERICAN LANGUAGE DICTIONARY - For More Effective Communication Between Americans and BritonsFrancesco Atzori100% (2)

- Contemporary Irish PoemsDocument35 pagesContemporary Irish PoemsRoger ValentineNo ratings yet

- Walk the Barrio: The Streets of Twenty-First-Century Transnational Latinx LiteratureFrom EverandWalk the Barrio: The Streets of Twenty-First-Century Transnational Latinx LiteratureNo ratings yet

- A Thanksgiving Story and Why People Speak English in The USADocument5 pagesA Thanksgiving Story and Why People Speak English in The USADusan StojsinNo ratings yet

- Transported Varieties 2Document71 pagesTransported Varieties 2Kritika RamchurnNo ratings yet

- History of English Canadian EnglishDocument17 pagesHistory of English Canadian EnglishsulfikarNo ratings yet

- What's Your English?: Varieties of English Around The WorldDocument2 pagesWhat's Your English?: Varieties of English Around The WorldMichelle YlonenNo ratings yet

- Dialnet LanguageAndJamaicanLiterature 7724714Document14 pagesDialnet LanguageAndJamaicanLiterature 7724714Jedidiah GrovesNo ratings yet

- Canadian EnglishDocument4 pagesCanadian EnglishMery AloyanNo ratings yet

- Spread of English Beyond The British IslesDocument26 pagesSpread of English Beyond The British IslesPamNo ratings yet

- Lexical Differences Between American and British English: A Survey StudyDocument15 pagesLexical Differences Between American and British English: A Survey StudyStefania TarauNo ratings yet

- Translating The Culture: by Linda White, Assistant Coordinator Thomas Mcclanahan, PH.D., PresidentDocument4 pagesTranslating The Culture: by Linda White, Assistant Coordinator Thomas Mcclanahan, PH.D., PresidentjackitoKopNo ratings yet

- Aguinaldos: Christmas Customs, Music, and Foods of the Spanish-speaking Countries of the AmericasFrom EverandAguinaldos: Christmas Customs, Music, and Foods of the Spanish-speaking Countries of the AmericasNo ratings yet

- Module 1Document8 pagesModule 1irish adla0wanNo ratings yet

- Myth, Symbol, and Colonial Encounter: British and Mi'kmaq in Acadia, 1700-1867From EverandMyth, Symbol, and Colonial Encounter: British and Mi'kmaq in Acadia, 1700-1867Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- TT3. Reading IiiDocument4 pagesTT3. Reading IiiMaria Caroline SamodraNo ratings yet

- Reyburn 1999 My Pilgrimage in MissionDocument3 pagesReyburn 1999 My Pilgrimage in MissionZaynab GatesNo ratings yet

- 7 Language and ClassDocument38 pages7 Language and ClassGrace JeffreyNo ratings yet

- Americans All Stories of American Life of To-DayFrom EverandAmericans All Stories of American Life of To-DayNo ratings yet

- Remedial Class-Activity #3 - Adverb - Joseth PasaloDocument4 pagesRemedial Class-Activity #3 - Adverb - Joseth PasaloJosethNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 (Present Indicatives)Document4 pagesChapter 5 (Present Indicatives)Dummy AccountNo ratings yet

- Department of Education Region III Schools Division of Zambales District of SubicDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education Region III Schools Division of Zambales District of SubicLarriie May SaleNo ratings yet

- IX. Uluslararası Hititoloji Kongresi Bildiri KitabıDocument43 pagesIX. Uluslararası Hititoloji Kongresi Bildiri KitabıBir Arkeoloji ÖğrencisiNo ratings yet

- ALBARACIN - Teaching Reading and WritingDocument57 pagesALBARACIN - Teaching Reading and WritingJessaMae AlbaracinNo ratings yet

- Bahan Ajar AnnouncementDocument7 pagesBahan Ajar AnnouncementJumanNo ratings yet

- Word-Formation: Group 3Document9 pagesWord-Formation: Group 3Juwita SariNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarter Intervention Plan For Least Mastered Skills English 5 S.Y 2019 2020Document3 pages2nd Quarter Intervention Plan For Least Mastered Skills English 5 S.Y 2019 2020Xsob LienNo ratings yet

- Nouns - Intro.Document1 pageNouns - Intro.Riyas JalalNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Explanation Text For HighSchool StudentsDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Explanation Text For HighSchool StudentsMy EducationNo ratings yet

- Handle Meetings With Confidence: ElementaryDocument5 pagesHandle Meetings With Confidence: ElementaryislamNo ratings yet

- Carretero Jackeline 233429885 Diagnostic-Results Reading 05012021Document17 pagesCarretero Jackeline 233429885 Diagnostic-Results Reading 05012021api-517983133No ratings yet

- Linguistic Modality in Ghanaian President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo's 2017 Inaugural AddressDocument9 pagesLinguistic Modality in Ghanaian President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo's 2017 Inaugural AddressKwabena Antwi-KonaduNo ratings yet

- Part 2 - Reading: English Language Final Exam - A1Document3 pagesPart 2 - Reading: English Language Final Exam - A1Hernan SantosNo ratings yet

- PPC PPS PPDocument15 pagesPPC PPS PPkarla AtaurimaNo ratings yet

- Basic English II BookletDocument72 pagesBasic English II BookletJonathan RodriguezNo ratings yet

- How To Say I Love You in 100 LanguagesDocument4 pagesHow To Say I Love You in 100 LanguagesRosca MariusNo ratings yet

- IELTS - Speaking Band DescriptorsDocument1 pageIELTS - Speaking Band DescriptorsIngrid FaberNo ratings yet

- Unit 10 Knowing A Second LanguageDocument4 pagesUnit 10 Knowing A Second LanguageNhật Minh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Variation in Child Language by J L RobertsDocument7 pagesVariation in Child Language by J L RobertsNandini1008No ratings yet

- Teacher's Manual - Phonics: Letter SoundsDocument21 pagesTeacher's Manual - Phonics: Letter SoundsPriya ChandranNo ratings yet

- Fola Final PassDocument6 pagesFola Final PassJovie EsguerraNo ratings yet

- English I Lesson Plan - DetailedDocument10 pagesEnglish I Lesson Plan - DetailedAdriyel Mislang SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Focus Teacher's BookDocument7 pagesFocus Teacher's BookViktória Iskum100% (1)

- Arabic Awakened Prospectus 21-22Document25 pagesArabic Awakened Prospectus 21-22Januhu ZakaryNo ratings yet

- Cause: The Game Was Cancelled Caused by Torrential RainDocument3 pagesCause: The Game Was Cancelled Caused by Torrential RainSam SmithNo ratings yet