Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Randomised Controlled Trial of Motivational Interviewing For Smoking Cessation

A Randomised Controlled Trial of Motivational Interviewing For Smoking Cessation

Uploaded by

jamie carpioOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Randomised Controlled Trial of Motivational Interviewing For Smoking Cessation

A Randomised Controlled Trial of Motivational Interviewing For Smoking Cessation

Uploaded by

jamie carpioCopyright:

Available Formats

R Soria, A Legido, C Escolano, et al

A randomised controlled trial

of motivational interviewing

for smoking cessation

Raimundo Soria, Almudena Legido, Concepión Escolano, Ana López Yeste

and Julio Montoya

INTRODUCTION

ABSTRACT Smoking is the main cause of preventable death in

Background developed countries.1 The natural history of

Motivational interviewing is a technique used to untreated smoking involves an increased probability

promote change in addictive behaviour, initially used to

of cardiovascular, respiratory and neoplastic

treat alcoholism. Despite this, its effectiveness has not

been sufficiently demonstrated for giving up smoking. diseases. Every year, tobacco causes 3.5 million

Aim deaths throughout the world.

The aim of the study was to establish whether In Spain, every year 56 000 people die from

motivational interviewing, compared with anti-smoking diseases directly related to smoking.2 According to the

advice, is more effective for giving up the habit.

2001 National Public Health Survey, the prevalence of

Design of study

smoking in the Spanish population over 16 years of

Randomised controlled trial.

age was 34.4% in that year. Compared with the figures

Setting

Primary care in Albecete, Spain. obtained in 1987, when the prevalence was 38.4%, a

Method slight drop in smoking in Spain can be found.3 In men,

Random experimental study of 200 smokers assigned smoking has gone down from 55% in 1987 to 42.1%

to two types of interventions: anti-smoking advice (n = in 2001. During the same period the habit in women

86) and motivational interviewing (n = 114). Subjects in

increased from 23 to 27.2%.

both groups were offered bupropion when nicotine

dependency was high (Fagerström score >7). The Within the sphere of primary health care, treatment

success rate was evaluated by intention to treat; point of tobacco addiction is one of the main challenges,

prevalence abstinence was measured 6 and 12 months in both primary and secondary prevention.

post intervention by personal testimony, confirmed by

However, since utilisation by the general

means of CO-oximetry (value < 6ppm).

population of primary healthcare consultations is

Results

The measure of effectiveness of the treatment for high (it is estimated that 75% of Spaniards consult

giving up smoking after both 6 and 12 months, showed their doctor at least once a year), with average

that the motivational interviewing action was 5.2 times frequency of 5.5 consultations per person yearly, this

higher than anti-smoking advice (18.4 % compared to

gives the GP and the health service numerous

3.4%; 95% confidence interval = 1.63 to 17.13).

opportunities to deal with tobacco addiction.4

Conclusion

The results of our study show that motivational There are many types of interventions to aid in

interviewing is more effective than brief advice for smoking cessation:5 anti-smoking advice given by

giving up smoking. doctors, structured actions in clinic consultations, self-

Keywords

clinical trial; motivation; motivational interviewing;

psychological techniques; smoking; treatment

effectiveness

R Soria, MBBS; A Legido, MBBS; C Escolano, MBBS;

A López Yeste, MBBS, Albacete, Zone I Health Centre, Spain.

J Montoya, MBBS, Albacete, Zone IV Health Centre, Spain.

Address for correspondence

Almudena Legido, Calle los Refranes no 17, Albacete, Spain.

E-mail: allegido17@hotmail.com

Submitted: 15 June 2005; Editor’s response: 4 January 2006;

final acceptance: 12 April 2006.

©British Journal of General Practice 2006; 56: 768–774.

768 British Journal of General Practice, October 2006

Original Papers

help materials, nicotine substitutes, antidepressants

and anxiolytics, aversion therapies, acupuncture and

hypnotherapy.

How this fits in

Smoking is the main cause of preventable death in developed countries.

Research into smoking by primary health care has,

Motivational interviewing is a useful tool for promoting change in addictive

given its feasibility, traditionally been based on

behaviour, although there is not sufficient proof of its effectiveness for smoking

medical anti-smoking advice. It has been shown that

cessation. Evidence from this trial indicates that motivational interviewing may be

brief medical advice is somewhat effective in a useful intervention for giving up smoking in primary healthcare settings.

promoting smoking cessation. Pooled data from 17

studies of brief advice versus no advice (or routine

care) revealed a small but significant increase in the interviews, versus anti-smoking advice for smoking

odds of quitting (odds ratio [OR] = 1.74, 95% cessation, at 6 and 12 months post intervention.

confidence interval [CI] = 1.48 to 2.05) following brief

advice. This equates to an absolute difference in the METHOD

quit rate of 2.5% between those receiving physician This is a randomised experimental study to assess

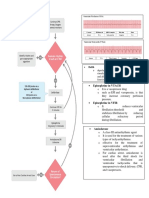

advice and those receiving routine care only. More two actions: advice versus MI (Figure 1).

intensive advice may result in slightly higher rates of

quitting. There is insufficient evidence to determine Physicians

whether use of aids or providing follow-up support The two categories of interventions, as well as all

after offering the advice increases the quit rates any initial and follow-up data collection and measures,

further.6 were conducted by five family physicians working

The apparent low efficacy is offset by the high within the Spanish Public Health Care System in two

number of smokers who may receive this treatment different Health Centres in the city of Albacete. Both

action, through minimum effort on the part of the Centres attend to an urban population of

physician. approximately 48 000 persons each, 13% of whom

More recently, recommendations from various are older than 65 years of age. The five doctors are

agencies (WHO 20017 and CDC 20008) indicate the members of the permanent staff in their respective

need to include motivational interviewing (MI) in the centres, each one assigned to attend a roster of 1900 Figure 1. Flow diagram of

treatment of smoking. patients over the age of 14 years. trial.

MI, a technique described by Miller in 1983,

initially used for treating alcoholism,9,10 is useful for

promoting change in addictive behaviour. It is a 200 smokers (patients)

patient-centred medical interview focused on Random allocation

examination and resolution of ambivalences

regarding unhealthy behaviours or habits. The

Brief advice Motivational

basic idea of this technique is that it is the patient n = 86 interviewing, n = 114

who reflects on and expresses their problems and

desire to change. The MI techniques allow the GP

to bring about an increase in the patient’s

First session First session

motivation, taking into account what their base

History of smoking Motivational History of smoking

motivational level is and always respecting their Stage of change

Stage of change interviewing sessions:

final decisions without penalising them. Brief advice 1. n = 26 (22.8%) First motivational

2. n = 50 (43.9%) interview

Prochaska11 et al, studying processes of change in

3. n = 38 (33.3%)

people who had given up smoking, found that they

were going through a series of stages, each one

characterised by a particular mental attitude and

level of motivational readiness. At present, the Six months Six months

Attendance n = 74 (86%) Attendance n = 87 (76.3%)

process of giving up smoking is studied mainly by No responsea n = 12 (14%) No responsea n = 27 (23.7%)

following the model that these authors put forward.

Most of the studies published using MI as a tool in

the treatment of addictive behaviour deal with

alcohol dependence. Nonetheless, numerous Twelve months Twelve months

Attendance n = 77 (89.5%) Attendance n = 97 (85.1%)

studies have applied the technique to tobacco No responsea n = 9 (10.5%) No responsea n = 17 (14.9%)

addiction, though few of them compare

effectiveness of MI with brief advice.12 a

Some of the patients who did not attend follow-up at 6 months were located for

The aim of the current study is to compare the follow-up at 12 months and vice-versa.

effectiveness in smokers of three motivational

British Journal of General Practice, October 2006 769

R Soria, A Legido, C Escolano, et al

The five GPs had been given specific training in MI Intervention

techniques by means of role-playing and video After opening the envelope, patients in both groups

recordings, in order to establish and combine the were given verbal and written information about the

basic contents, both of the brief individual action study’s purpose, aims and procedures.

(anti-smoking advice) and the MI action. The personal details of each patient were then

collected (age, sex, educational level, employment),

Participants variables relating to tobacco consumption (presence

All subjects in this study were patients on the rosters of disease related to tobacco consumption — chronic

of the five physician–investigators described above. obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and

200 active smoker patients between the ages of 15 ischaemic heart disease — number of cigarettes

and 75 years were recruited during regular visits to smoked a day, age when the patient started smoking,

their respective GPs, for whatever reason. None of years smoking) and stage of change, according to the

the subjects had been recipients of pre-selection five stages of change described by Prochaska-

cards nor publicity regarding the trial, nor were they DiClemente:11 precontemplative, contemplative,

chosen for the study with respect to any particular action, maintenance and relapse.

pathology. The degree of nicotine dependency was assessed

A smoker was considered to be any person who by Fagerström’s test.13 Depending on the result that

replied ‘yes’ to the question: Do you smoke? each smoker gives to each question, a certain mark

Patients were recruited over a period of is obtained, that may vary from 0–10 points.

23 months; informed consent was requested from all A degree of slight dependency is considered when

those taking part in the trial. Exclusion criteria were the test varies from 0 to 3 points; moderate

existence of severe psychiatric disorder, a terminal dependency is from 4 to 6 points; a severe degree of

illness or drug-addiction, or age <15 or >75 years. dependency is 7 points or over.

The smokers participating in the study were In all patients, the level of carbon monoxide in the

assessed over a total period of 1 year, and follow- air expired at the start of the study was measured by

ups of the effectiveness of the interventions were means of a micro smokerlyser carbon monoxide (CO)

conducted after 6 and 12 months post intervention. monitor14 (Bedfont Technical Instruments Ltd). CO

values were used as abstinence markers, 6 and

Sample size calculation 12 months after the action. Figures of ≥10 ppm of

Calculation of the sample size was made by CO indicate smokers; 6–10 ppm sporadic smokers,

considering an effectiveness in giving up smoking of and <6 ppm, non-smokers.15

5% with anti-smoking advice and of 20% with MI, In the same first consultation, following data

that is to say a relative effectiveness four times collection and CO measurements, the action

higher for MI over advice. Two groups of 100 assigned to each subject case was carried out.

subjects were necessary (α risk level of 0.05% and Patients receiving anti-smoking advice were

90% capacity to detect the difference existing given one intervention session consisting of a

between groups). personal talk by their physician, lasting

approximately 3 minutes. The dangers of smoking

Randomisation sequence generation were explained, as well as the advantages of giving

The patients were randomly assigned to either one of it up. The information given in all advice

the actions groups by means of a non-block table of consultations was the same and in accordance with

random numbers. The assignment sequence the recommendations of the Smoking Department

established resulted in one group of 86 patients of the Spanish Pneumology and Chest Surgery

receiving brief advice and another of 114 subjects Association (SEPAR).16

assigned to MI. Patients assigned to MI were given the first of a

Two hundred non-transparent sealed envelopes total of three 20–minute interviews conducted in the

containing the interventions (either brief advice or MI) physician’s office. There was no established protocol

were prepared. Before the start of daily for time lapse between interviews; rather,

consultations, the GPs conducting the interventions appointments for the subsequent session were set

would extract one of the envelopes, not knowing the up with the GP at the patient’s convenience.

type of action it contained. The first smoker patient Patients in both intervention groups showing high

who attended the consultation would be offered the nicotine-dependency (Fagerström’s test scores of

possibility of taking part in the study. If they accepted ≥7), were offered the possibility of concurrent

and signed the informed consent form, the envelope treatment with bupropion, the first non-nicotine

would be opened, upon which the GP would learn of medication approved for treating tobacco

the patient’s group assignment. dependence.17

770 British Journal of General Practice, October 2006

Original Papers

Outcome measures

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the smokers in both

All patients were contacted at 6 and 12 months post

actions.

intervention for follow-up appointments. Smoking

habits were assessed 6 and 12 months post Motivational Advice

intervention, by measuring number of cigarettes Action Interviewing n = 114 n = 86

smoked a day, the degree of nicotine dependency Mean age in years (SD) 38.58 (12.17) 38.44 (12.37)

according to Fagerström’s test, stage of change, as Women (%) 51.8 53.5

well as level of CO in expired air in all those taking Mean age in years when 16.31 (3.70) 17.13 (5.11)

part in the MI group and in those in the advice group started smoking (SD)

who reported abstinence. Smokers in active 86.0 75.6

The final primary variable measured was success employment (%)

index, namely point prevalence of abstinence at 6 and Mean number of years 21.40 (12.29) 19.94 (12.15)

12 months post intervention. Abstinence was of consumption (SD)

subjectively ascertained by means of direct personal Mean number of cigarettes 19.40 (10.26) 17.47 (10.24)

testimony, and objectively confirmed by obtaining smoked a day (SD)

values of less than 6 ppm of CO in expired air Mean CO-oximetry (SD) 15.40 (9.00) 15.10 (10.03)

(reference value acknowledged as a cut-off point Mean Fagerström’s test score (SD) 4.16 (2.71) 3.87 (2.59)

between smokers and non-smokers). Failure of COPD (%) 8.8 4.7

abstinence was defined as continuation of the Ischaemic heart disease (%) 2.6 1.2

smoking habit or non-attendance of follow-ups to Precontemplative stage (%) 56.1 70.9

confirm abstinence. Contemplative stage (%) 36.8 27.9

Decision stage (%) 7.0 1.2

Statistical analysis

COPD = coronary obstructive pulmonary disease.

Statistical analysis was made in blind form, without

knowing the identification labels of the groups that

were compared. The results were analysed using (range = 16–75 years), with a slight predominance of

SPSS. First of all, a description was made of the women over men (52.5 versus 47.5%).

variables studied in both groups, comparing the Only 7% of smokers had been diagnosed with

distribution of the determining factors that may have COPD and 2% with ischaemic heart disease. The

affected the final result, and then a comparison was majority (80.8%) of subjects were in active

made of the proportion of successes by means of the employment, while 19.2% were unemployed or

χ2 test. retired. The average age for starting smoking was

In order to evaluate the modifying variables of the 16 years. Average consumption was 18 cigarettes a

effect and avoid confusion factors, recourse was day and the average smoking period was 20 years

made to multivariant analysis, constructing a logistic (range = 1–55 years). The average score in

regression model by the step-by-step inclusion Fagerström’s test was 4.04. The level of CO in

method, in which the dependent variable was the expired air at the start of the study was 15.27 ppm.

success or failure of the anti-smoking action, after Regarding the degree of motivation according to the

both 6 and 12 months. classification of stages of change, 63.5% of smokers

The trial was analysed by intention to treat, were in a precontemplative stage at the start of the

evaluating each subject in the study group to which study, 32.4% in a contemplative stage and 4.1% had

they were randomly assigned. The extent of the taken the decision to give up smoking. In patients

therapeutic effect and the accuracy in its estimation assigned to advice, 70.9, 27.9 and 1.2% were in the

was considered, calculating the reduction in relative precontemplative, contemplative and determined

risk, the reduction in absolute risk and the absolute stages, respectively, with P = 0.04. In the MI group,

increase in benefit, as well as the number of patients 56.1, 36.8 and 7% were in the above-mentioned

it would be necessary to treat in order to avoid a stages, respectively.

negative result. Patients in this study with high physical

The study was approved by the medical research dependency levels (that is; Fagerström’s test scores

ethics committee of the Albacete University Hospital of ≥7) were offered the possibility of using bupropion

Complex (Spain) on 3 April 2003. as an adjunct medical treatment. This medication

was to be self-financed by the patient. Only 2.5%

RESULTS (five patients) began bupropion use; these five

Demographic and smoking characteristics patients were assigned to the MI intervention.

The baseline characteristics of the two groups are Patient adherence to the MI intervention was as

shown in Table 1. Patients’ average age was 38 years follows: 26 (22.8%) smokers attended the first

British Journal of General Practice, October 2006 771

R Soria, A Legido, C Escolano, et al

changes, without imposition or blame by the

Table 2. Effectiveness of actions to give up smoking after 6

and 12 months. physician. Repeated advice, on the other hand, may

be perceived as preaching, with subsequent risk of

Motivational damaging the doctor–patient relationship and

Advice Interviewing

producing contrary behaviour.18

n = 86 n = 114 P OR 95% CI NNT

Abstinence after 3 (3.5) 21(18.4) 0.00 6.25 1.8-21.71 7

Comparison with existing literature

6 months (%)a

Abstinence after 3 (3.5) 21(18.4) 0.001 6.25 1.8-21.71 7 Until now, there has been limited evidence that MI

12 months (%)a and stage-of-change based interventions are

a

The fact that identical abstinence figures were obtained at 6 and 12 months in both groups

effective for smoking cessation.19 The use of these

was purely coincidental. NNT = number needed to treat. OR = odds ratio. methods has therefore not been justified in routine

care by family physicians. Brief advice, however,

interviewing only, 50 (43.9%) attended two interviews about which more has been published, has been

and 38 (33.3%) patients kept all three appointments. more extensively employed in clinical practice.6

A previous study conducted in a primary care

Effectiveness setting by Butler et al12 comparing effectiveness of MI

The measure of effectiveness of smoking cessation versus brief advice for smoking cessation in 536

treatment at both 6 and 12 months post smokers not selected for any other pathology,

intervention showed that the action based on MI showed moderately higher success for the stage-

was 5.28 times more successful than anti-smoking based intervention. At 6 months post intervention,

advice (Table 2; odds ratio [OR] = 6.25, 95% CI = significant differences between groups in scores on

1.8 to 21.7 at both 6 and 12 months).The fact that self-reported abstinence in the previous 24 hours

identical abstinence figures were obtained at 6 and were found (OR = 2.86, 95% CI = 1.21 to 6.76).

12 months in both patient groups was purely However, the odds of abandonment of the smoking

coincidental, given that some patients who did not habit at 6 months were considerably higher in our

respond at 6 months to confirm abstinence, did so study for the MI group (OR = 7.65, 95% CI = 2.18 to

at 12 months and vice versa. 26.84) than in the Butler trial.12

The absolute increase in benefit was 14.9% (95% Our relatively high abstinence levels for the MI

CI = 6.8 to 23%) and the number of smokers intervention may be partly attributed to the fact that

necessary to treat was 7 (95% CI = 5 to 15). the GPs conducting the interviews in our study

Regarding attendance of follow-up, 12 patients were the patients’ regular family physicians. The GP

from the advice group and 27 patients from the MI registrars in the Butler et al study12 (resident

group did not attend the first follow-up at 6 months doctors) trained in MI techniques were not the

post intervention. At 12 months, nine advice and 17 patients’ habitual physicians; thus, although

MI subjects did not attend appointments. In the perhaps more enthusiastic, their experience and

logistic regression model, after both 6 and knowledge of the study subjects would have been

12 months, the action appeared as a variable more limited. Moreover, patients tend to respond

independently associated with smoking cessation. more positively to doctors with whom they have

No confusion factors or effect-modifying variables maintained enduring doctor–patient relationships.

were found. The probability of giving up the habit Another difference between the current study and

was 7.6 times greater in the MI group after the Butler trial lies in the intensity of the MI

6 months (OR = 7.65, 95% CI = 2.18 to 26.84) and intervention. Our patients were scheduled for three

6.9 times greater after 12 months (OR = 6.91, 95% MI consultations, whereas in the Butler study, they

CI = 1.98 to 24.15). were exposed to only one interview. Therefore,

repeated stage of change based interventions may

DISCUSSION be more effective than a single consultation.

Summary of main findings Other interventions reviewed by Lancaster and

The primary objective of this study was to Stead20 of a similar nature to MI, such as individual

determine whether MI was a more effective anti- behavioural counselling, have shown a certain

smoking intervention than brief advice. Our results efficacy, with a reported OR of abandonment of the

show that MI is more effective than brief advice for smoking habit of 1.56 (95% CI = 1.32 to 1.84). Once

smoking cessation in a primary care setting. Higher again, however, the OR we report are considerably

levels of abstinence in the MI group may be higher. These differences in results may be due to

attributed, in part, to the patient-centred nature of the nature of stage-based interventions, as

the stage based intervention, where smokers previously described, and/or to the fact that in the

actively involve themselves in making habit behavioural counselling studies reviewed, sessions

772 British Journal of General Practice, October 2006

Original Papers

were administered by a trained therapist unknown opposed to a block table, resulting in unbalanced

to the patient. group sizes of 114 MI patients and 86 belonging to

the advice group.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This is a study of the development and evaluation of Implications for future research

a motivational interviewing intervention for primary The unusually high OR of abandonment of the

care use only. In our trial, patients were recruited smoking habit obtained in our study by the MI

during a regular visit to their GP for whatever reason intervention, raises several questions for future

and were not selected for any type of disease. No research. Since the current study was conducted in

prior advertisements were issued regarding the trial a general practice setting with GPs familiar to

and subjects had not received pre-selections cards. patients, comparisons should be made with stage-

Therefore a more realistic assessment of the based techniques carried out by therapists

effectiveness of the intervention variable could be unconnected to subjects, in specific tobacco

made under normal conditions experienced by GPs addiction treatment consultations.

and their patients on a daily basis. The MI group in our study received three treatment

The design of our study presents several sessions, whereas patients in the advice group were

limitations. As part of our efforts to evaluate the exposed to only one consultation with the GP,

efficacy of MI in the normal course of a GP’s daily suggesting that intensity of the intervention, rather

practice, adolescents as young as 15 years of age than efficacy of stage-based therapy and MI, may be

were included in the trial, given the reality that family responsible for higher abstinence levels. Further

physicians in Spain attend patients over the age of investigations are needed to compare effectiveness

14 years (minors of 14 years and younger are treated of more brief tailored MI interventions with brief

by paediatricians). The drawback to the admittance advice and to evaluate whether single session MI

of young adolescent smokers in the study lies with interventions are as effective as repeated ones.

the fact that they have not had sufficient time to It may also be of interest to ascertain from which

develop established nicotine dependency, thus stage of change anti-smoking therapy is most likely to

increasing their chances of successful quitting. be successful. The cost-effectiveness of MI

For ethical reasons, patients in our study with high compared to other interventions should also be

nicotine dependency were offered bupropion as investigated, since application of the method requires

adjunct therapy (five patients from the MI group training of physicians and extra consultation time.

accepted). It is well-demonstrated that this therapy is

effective for smoking cessation, increasing quitting Funding body

odds by 1.5–2 times, independent of setting.17 Research project financed by the Department of Health,

Health Science Institute of the Government of the

Therefore, these patients should probably have been Autonomous Communities of Castille – La Mancha,(Spain)

excluded from the trial, as they may potentially have according to the decision taken at the meeting of 19

February 2003 (D. O. C. M. number 21)

skewed results in favour of the MI intervention.

Ethics committee

Regarding patient characteristics at the outset of

Project approved by the Medical Research Ethics

the study, the two groups were not homogeneous Committee of the Albacete Health Service,(Spain) taking

with respect to the variable ‘stage of change.’ A into consideration that the aforesaid project was in

accordance with the essential ethical standards used in this

greater number of MI patients than advice patients field, as recorded in minutes no. 05/03 of the Medical

were classified as belonging to a contemplative or Research Ethics Committee meeting in Albacete held on

3 April 2003

decision stage (Table 1), thus favouring more

successful outcomes in the MI group. However, it is Competing interests

The authors have stated that there are none

also possible that since stage of change was

Acknowledgements

determined following group assignation of subjects, We wish to thank all the patients who worked with us and

GPs tended to overestimate the motivation of were involved in the project. Special thanks go to Dr. López

Torres for his impartial cooperation as scientific advisor.

patients belonging to the MI group. Ideally, data

collection from smokers and classification of stage of

REFERENCES

change should have been performed by an 1. Peto R, López AD, Boreham J, et al. Mortality from tobacco in

independent investigator before randomisation and developed countries: indirect estimation from national vital

statistics. Lancet 1992; 339: 1268–1278.

group assignation of patients. However, our wish to

2. Banegas Banegas JR, Diez Gañan L, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, et al.

be pragmatic and produce minimal alterations in the Mortalidad atribuible al tabaquismo en España en 1998.

course of our consultations did not allow us to (Smoking-attributable deaths in Spain in 1998). Med Clin (Barc)

2001; 117: 692–694.

proceed in this way.

3. Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Encuesta Nacional de Salud de

Lastly, patient randomisation was achieved by España 1997. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo, 1999.

applying a non-block table of random numbers as 4. Alonso JM, Magro R, Martínez JA, Sanz N. Tabaco y atención

British Journal of General Practice, October 2006 773

R Soria, A Legido, C Escolano, et al

primaria. En: Comité Nacional para la Prevención del Tabaquismo.

El Libro Blanco sobre el tabaquismo en España. (Tobacco and

Primary Care. In: National Committee Smoking Prevention. White

Paper about Smoking in Spain). Barcelona: Glosa SL, 1998.

5. Lancaster T, Stead L, Silagy C, Sowden A. Effectiveness of actions

to help people stop smoking: findings from the Cochrane Library.

BMJ 2000; 321: 355–358.

6. Lancaster T, Stead LF. Physician advice for smoking cessation

[review]. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; Issue 4: CD000165.

7. World Health Organisation. Evidence-based recommendations on

the treatment of tobacco dependency. Copenhagen: WHO, 2001.

8. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Strategies for

reducing exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, increasing

tobacco-use cessation and reducing initiation in communities and

health-care systems. A report on recommendations of the Task

Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR 2000; 49(RR-

12): 1–11.

9. Miller WR. Motivational interviewing with problem drinkers.

Behavioural Psychotherapy 1983; 11: 147–172.

10. Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people

to change addictive behaviour. Barcelona: Ed Paidós; 1999.

11. Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change

of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin

Psychol 1983; 51(3): 390–395.

12. Butler C, Rollnick S, Cohen D, et al. Motivational consulting versus

brief advice for smokers in general practice: a randomised trial. Br

J Gen Pract 1999; 49: 611–616.

13. Fagerström KO, Schneider NG. Measuring nicotine dependence: a

review of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. J Behav Med

1989; 12: 159–182.

14. Jarvis M J, Russell MAH, Saloojee Y. Expired air carbon monoxide:

a simple breath test of tobacco smoke intake. BMJ 1980; 281:

484–485.

15. Russell MAH, Merriman R, Stapleton J, Taylor W. Effect of

nicotine chewing gum as an adjunct to general practitioner advice

against smoking. BMJ 1983; 287: 1782–1785.

16. Jiménez CA, Solano S, González de Vega JM, et al. Tratamiento del

tabaquismo. En: Recomendaciones SEPAR. (Treatment of tobacco

dependency. In: SEPAR Recommendations). Barcelona: Doyma,

1998: 421–436.

17. Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking

cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; Issue 4: CD000031.

18. Butler CC, Pill R, Stott NC. Qualitative study of patients’

perceptions of doctors’ advice to give up smoking: implications for

opportunistic health promotion. BMJ 1998; 316: 1878–1881.

19. Riemsma RP, Pattenden J, Bridle C, et al. Systematic review of the

effectiveness of stage based interventions to promote smoking

cessation. BMJ 2003; 326: 1175–1177.

20. Lancaster T, Stead LF. Individual behavioural counselling for

smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; Issue 2:

CD001292.

774 British Journal of General Practice, October 2006

You might also like

- Jake - MH TeamDocument1 pageJake - MH Teamjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Aversive Smoking For Smoking CessationDocument22 pagesAversive Smoking For Smoking Cessation77felixNo ratings yet

- Clinical Hypnosis For Smoking CessationDocument9 pagesClinical Hypnosis For Smoking Cessationamad90100% (1)

- Putting Evidence Into Practice Smoking CessationDocument48 pagesPutting Evidence Into Practice Smoking CessationXinyi LiewNo ratings yet

- Intervention For Smoking ReductionDocument15 pagesIntervention For Smoking Reductionben mwanziaNo ratings yet

- Passed and Cleared' - Former Tobacco Smokers' Experience in Quitting SmokingDocument9 pagesPassed and Cleared' - Former Tobacco Smokers' Experience in Quitting SmokingzikriNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Metode Konseling Dalam Membantu Mengurangi Kecanduan RokokDocument5 pagesJurnal Metode Konseling Dalam Membantu Mengurangi Kecanduan RokokNina MarliatiNo ratings yet

- Efektifitas Terapi Akupresur Terhadap Upaya Berhenti Merokok Di Desa Sungai Terap Kecamatan Kumpeh UluDocument8 pagesEfektifitas Terapi Akupresur Terhadap Upaya Berhenti Merokok Di Desa Sungai Terap Kecamatan Kumpeh UluOktia Rahmi100% (1)

- Factors Relating To Failure To Quit Smoking A Prospective Cohort StudyDocument7 pagesFactors Relating To Failure To Quit Smoking A Prospective Cohort StudySilas SilvaNo ratings yet

- Does A Population-Based Multi-Factorial Lifestyle Intervention Increase Social Inequality in SmokingDocument9 pagesDoes A Population-Based Multi-Factorial Lifestyle Intervention Increase Social Inequality in SmokingIr. Nyoman MahardikaNo ratings yet

- Cesation For Mild Intelectual Singh 2013Document10 pagesCesation For Mild Intelectual Singh 2013alejandroNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1.4 yDocument20 pagesJurnal 1.4 yAmbarsari HamidahNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Smoking Cessation Success in AdultsDocument8 pagesEvaluation of Smoking Cessation Success in AdultsSISNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Metode Konseling Dalam Membantu Mengurangi Kecanduan Rokok-DikonversiDocument5 pagesJurnal Metode Konseling Dalam Membantu Mengurangi Kecanduan Rokok-DikonversiNina MarliatiNo ratings yet

- A Game For SmokersDocument4 pagesA Game For SmokerstifaniNo ratings yet

- Aspek Neurologi Hipnoterapi Untuk Penghentian Merokok: Neurogical Aspects of Hypnotherapy For Smoking CessationDocument9 pagesAspek Neurologi Hipnoterapi Untuk Penghentian Merokok: Neurogical Aspects of Hypnotherapy For Smoking CessationSulaiman Noer FaiezyNo ratings yet

- Psychological Features of Smokers: Askin Gu Lsen MD and Bu Lent Uygur MDDocument6 pagesPsychological Features of Smokers: Askin Gu Lsen MD and Bu Lent Uygur MDMarianaNo ratings yet

- Tobacco Cessation Treatment PlanDocument7 pagesTobacco Cessation Treatment PlanyellowishmustardNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Different Treatment Methods To Curb Smoking AddictionDocument15 pagesThe Effectiveness of Different Treatment Methods To Curb Smoking AddictionAzreZephyrNo ratings yet

- 9721 Smoking Cessaton Newsletter 1981Document8 pages9721 Smoking Cessaton Newsletter 1981Julia PurperaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal StopSmoking! PDFDocument21 pagesJurnal StopSmoking! PDFIbrahim JutNo ratings yet

- Research Paper-2Document9 pagesResearch Paper-2api-741551545No ratings yet

- Antidepresivos y PesoDocument11 pagesAntidepresivos y Pesogtellez25No ratings yet

- Hynoterapi Untuk Berhenti Merokok PDFDocument14 pagesHynoterapi Untuk Berhenti Merokok PDFsri subektiNo ratings yet

- AJGP 10 2019 Focus Manger Lifestyle Interventions Mental Health WEBDocument4 pagesAJGP 10 2019 Focus Manger Lifestyle Interventions Mental Health WEBisitugasnandasekarbuanaNo ratings yet

- Tobacco Cessation in India: Labani Satyanarayana, Smita Asthana, Sumedha Mohan, Gourav PopliDocument3 pagesTobacco Cessation in India: Labani Satyanarayana, Smita Asthana, Sumedha Mohan, Gourav PopliHakim ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Dapus Referat No.4Document7 pagesDapus Referat No.4Muhammad AkrimNo ratings yet

- Smoking Cessation Nursing InterventionsDocument12 pagesSmoking Cessation Nursing Interventionsapi-741272284No ratings yet

- Smoking in Psychiatric Hospitals: What Is The Role of Nursing Staff?Document5 pagesSmoking in Psychiatric Hospitals: What Is The Role of Nursing Staff?International Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, KarnatakaDocument26 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, KarnatakaAmit TamboliNo ratings yet

- Nursing Research Paper Final DraftDocument15 pagesNursing Research Paper Final Draftapi-593455086No ratings yet

- Psychological Effect F NicotineDocument6 pagesPsychological Effect F NicotinehelfiNo ratings yet

- 2018 HuanDocument8 pages2018 HuanRahul GoyalNo ratings yet

- Q 3 Cdy HKB PHBXM 5 WN QX VW XG PDocument8 pagesQ 3 Cdy HKB PHBXM 5 WN QX VW XG P517wangyiqiNo ratings yet

- Walid Sarhan F. R. C. PsychDocument46 pagesWalid Sarhan F. R. C. PsychFree Escort ServiceNo ratings yet

- Accepted ManuscriptDocument40 pagesAccepted ManuscriptsueffximenaNo ratings yet

- Smoking Cessation or Reduction With Nicotine Replacement Therapy: A Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Trial With Nicotine Gum and InhalerDocument28 pagesSmoking Cessation or Reduction With Nicotine Replacement Therapy: A Placebo-Controlled Double Blind Trial With Nicotine Gum and InhalerSigit Harya HutamaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Clinical TrialsDocument8 pagesContemporary Clinical TrialsAzisahhNo ratings yet

- Cooper 2019Document16 pagesCooper 2019Lee HaeunNo ratings yet

- RelapseDocument10 pagesRelapseEmil Eduardo Julio RamosNo ratings yet

- Cannabis Medicina Basada en Evidencia EspañaDocument6 pagesCannabis Medicina Basada en Evidencia EspañaCarla AndradeNo ratings yet

- AbstractreadingDocument2 pagesAbstractreadingapi-341690050No ratings yet

- Health Consequences of Sustained Smoking Cessation FinalDocument5 pagesHealth Consequences of Sustained Smoking Cessation FinalAmin Mohamed Amin DemerdashNo ratings yet

- Epidemiological Characteristics, Safety and Efficacy of Medical Cannabis inDocument7 pagesEpidemiological Characteristics, Safety and Efficacy of Medical Cannabis inDanielNo ratings yet

- Journal Analysis-RESKI NURUL AFIFAHDocument6 pagesJournal Analysis-RESKI NURUL AFIFAHResky Nurul AfifaNo ratings yet

- Tatarsky+Marlatt 2010Document6 pagesTatarsky+Marlatt 2010Iyari LovegoodNo ratings yet

- File 1491650685 PDFDocument10 pagesFile 1491650685 PDFAngga PratamaNo ratings yet

- Dong Liu WuDocument29 pagesDong Liu WuJohn Vincent Consul CameroNo ratings yet

- How To Encourage To Stop SmokingDocument12 pagesHow To Encourage To Stop SmokingSamNo ratings yet

- Dawley 1975Document4 pagesDawley 1975Noor ChahayaNo ratings yet

- A Randomized, Multicentre, Open-Label, Comparative Trial of Disulfuram, Naltrexone, and Acamprosate in The Treatment of Alcohol DependenceDocument9 pagesA Randomized, Multicentre, Open-Label, Comparative Trial of Disulfuram, Naltrexone, and Acamprosate in The Treatment of Alcohol DependenceAlexander ColeNo ratings yet

- Pembelajaran Penyakit Terkait Perilaku Merokok Dan Edukasi Untuk Berhenti Merokok Di Pendidikan Dokter Fakultas Kedokteran UgmDocument16 pagesPembelajaran Penyakit Terkait Perilaku Merokok Dan Edukasi Untuk Berhenti Merokok Di Pendidikan Dokter Fakultas Kedokteran UgmkiranaNo ratings yet

- Pepito, Rjay cls#3Document8 pagesPepito, Rjay cls#3PEPITO, ARJAY F.No ratings yet

- Comparison of Topiramate and Naltroxene For Treatment of Alcohol DependenceDocument8 pagesComparison of Topiramate and Naltroxene For Treatment of Alcohol Dependencejgwatson1979No ratings yet

- Fneur 10 01145Document9 pagesFneur 10 01145ivoroNo ratings yet

- A Population Level Analysis of Changes in AustraliDocument17 pagesA Population Level Analysis of Changes in AustraliYuning tyas Nursyah FitriNo ratings yet

- J Jpsychires 2010 06 006Document7 pagesJ Jpsychires 2010 06 006Lumeiko LukaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Tobacco and Cigarette Consumption and Their Relationship Between Psychological Behaviour - A Narrative ReviewDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Tobacco and Cigarette Consumption and Their Relationship Between Psychological Behaviour - A Narrative ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Drug and Alcohol DependenceDocument7 pagesDrug and Alcohol DependenceNur Melizza, S.Kep., NsNo ratings yet

- Developing and Implementing A Smoking Cessation Intervention in Primary Care in NepalDocument1 pageDeveloping and Implementing A Smoking Cessation Intervention in Primary Care in NepalCOMDIS-HSDNo ratings yet

- Motivasi Berhenti Merokok Pada Perokok Dewasa Muda Berdasarkan Transtheoretical Model (TTM)Document8 pagesMotivasi Berhenti Merokok Pada Perokok Dewasa Muda Berdasarkan Transtheoretical Model (TTM)ari edogawaNo ratings yet

- Culture and Sensitivity: InhalationDocument3 pagesCulture and Sensitivity: Inhalationjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Mari Andrew: Am I There Yet?: The Loop-De-Loop, Zigzagging Journey To AdulthoodDocument4 pagesMari Andrew: Am I There Yet?: The Loop-De-Loop, Zigzagging Journey To Adulthoodjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- RowariwudujiladekodazelaDocument3 pagesRowariwudujiladekodazelajamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Brunner and Suddarth's Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing 12th Ed. (Dragged) 4Document1 pageBrunner and Suddarth's Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing 12th Ed. (Dragged) 4jamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Disorders: Types of DysrythmiasDocument3 pagesCardiovascular Disorders: Types of Dysrythmiasjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Brunner and Suddarth's Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing 12th Ed. (Dragged) 6Document1 pageBrunner and Suddarth's Textbook of Medical-Surgical Nursing 12th Ed. (Dragged) 6jamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Jake PetersonDocument1 pageJake Petersonjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Public Health Community Health Nursing: Goal: To Enable EveryDocument10 pagesPublic Health Community Health Nursing: Goal: To Enable Everyjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Code MNGTDocument3 pagesCode MNGTjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Paid Maternity Leave Claiming Personal Exemptions National Immunization DayDocument2 pagesPaid Maternity Leave Claiming Personal Exemptions National Immunization Dayjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis A Hepatitis B Hepatitis C Hepatitis D Hepatitis E Hepatitis GDocument9 pagesHepatitis A Hepatitis B Hepatitis C Hepatitis D Hepatitis E Hepatitis Gjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- MS TopicsDocument1 pageMS Topicsjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- El Aqoul2017Document9 pagesEl Aqoul2017jamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Nusing NCP Blood Transfusion NCP: Total Parenteral NutriDocument2 pagesNusing NCP Blood Transfusion NCP: Total Parenteral Nutrijamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Rapid Rehabilitation Nursing in Postoperative Patients With Colorectal Cancer and Quality of LifeDocument8 pagesRapid Rehabilitation Nursing in Postoperative Patients With Colorectal Cancer and Quality of Lifejamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Communication Competency: The Topic of Lifelong Learning For Nurse Managers in HospitalsDocument7 pagesCommunication Competency: The Topic of Lifelong Learning For Nurse Managers in Hospitalsjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- CONCEPTSDocument1 pageCONCEPTSjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Family Nursing Care PlanDocument34 pagesFamily Nursing Care Planjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- OBSTETRICSDocument4 pagesOBSTETRICSjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Citation 336796047Document1 pageCitation 336796047jamie carpioNo ratings yet

- Electronic Physician (ISSN: 2008-5842) : 1.1. BackgroundDocument10 pagesElectronic Physician (ISSN: 2008-5842) : 1.1. Backgroundjamie carpioNo ratings yet

- 2012 PatrickWilliams SDTandMI IJBNPADocument12 pages2012 PatrickWilliams SDTandMI IJBNPATitis Retno Sawitri SawitriNo ratings yet

- Boanerges: LewisDocument1 pageBoanerges: Lewisapi-245244824No ratings yet

- Groundswell Room To Breathe Full Report 2016Document35 pagesGroundswell Room To Breathe Full Report 2016Maria MirabelaNo ratings yet

- Smoking Secnav 5100 - 13cDocument8 pagesSmoking Secnav 5100 - 13cWill BorrallNo ratings yet

- Example of A Healthy Meal Plan For A 45 Year Old ManDocument12 pagesExample of A Healthy Meal Plan For A 45 Year Old ManzyloexNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6026 Assessment 3 Population Health Policy AdvocacyDocument4 pagesNURS FPX 6026 Assessment 3 Population Health Policy AdvocacyEmma WatsonNo ratings yet

- Final Thesis Topic About Sin Tax LawDocument11 pagesFinal Thesis Topic About Sin Tax LawRomnick JesalvaNo ratings yet

- Potential Therapeutic Effects of PsilocybinDocument7 pagesPotential Therapeutic Effects of Psilocybindaniel_jose_skateNo ratings yet

- Market Research TRAIN LAWDocument60 pagesMarket Research TRAIN LAWRusselNo ratings yet

- Effect of VareniclineDocument8 pagesEffect of VareniclineDANIELA GUARDO CARMONA ESTUDIANTENo ratings yet

- Research Paper About Smoking in The PhilippinesDocument8 pagesResearch Paper About Smoking in The Philippinesefj02jba100% (1)

- Note GuideDocument2 pagesNote GuideDemetrius Hobgood0% (1)

- Final Draft of Smoking Cessation Poster TemplateDocument1 pageFinal Draft of Smoking Cessation Poster Templateapi-540025326No ratings yet

- Amanda B.'s Story - Real Stories - Tips From Former Smokers - CDCDocument4 pagesAmanda B.'s Story - Real Stories - Tips From Former Smokers - CDCalex SimpsonNo ratings yet

- Northwest Queens Community Health ProfileDocument16 pagesNorthwest Queens Community Health ProfileAlicia FernandezNo ratings yet

- Name: Shrushti Shah Class: 11 B Roll No.: 43 Subject: Biology Topic: How Cigarettes Affect Your Health?Document23 pagesName: Shrushti Shah Class: 11 B Roll No.: 43 Subject: Biology Topic: How Cigarettes Affect Your Health?AHMED NAEEM 2No ratings yet

- Hypnosis Scripts ExamplesDocument8 pagesHypnosis Scripts Exampleserich70No ratings yet

- Text For Number 1-5 Teenagers Smoke: Riventus Xiipa1Document3 pagesText For Number 1-5 Teenagers Smoke: Riventus Xiipa1zzzzjrjaNo ratings yet

- Best Pulmonologist in DelhiDocument3 pagesBest Pulmonologist in DelhiDr Vikas MittalNo ratings yet

- Test 30Document8 pagesTest 30Hùng Thân NguyênNo ratings yet

- Writing Letter FormatDocument8 pagesWriting Letter FormatIggy GalganoNo ratings yet

- Tobacco CessationDocument45 pagesTobacco CessationGhada El-moghlyNo ratings yet

- Directed Writing ArticleDocument2 pagesDirected Writing ArticleAhmad Ismail71% (7)

- Truth Initiative Statement On Harm Reduction FinalDocument13 pagesTruth Initiative Statement On Harm Reduction FinalBrent StaffordNo ratings yet

- Stage of Change-Questions and StrategiesDocument2 pagesStage of Change-Questions and Strategiespharmacist2000No ratings yet

- Plan of Care For Ineffective Air Way 1Document6 pagesPlan of Care For Ineffective Air Way 1LisaNo ratings yet

- Smoking, Smoking CessationDocument5 pagesSmoking, Smoking CessationNikhilNo ratings yet

- Harm Reduction Strategy PDFDocument184 pagesHarm Reduction Strategy PDFArjumand AdilNo ratings yet

- Smoking Cessation in RSNDocument5 pagesSmoking Cessation in RSNtonylee24No ratings yet