Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Communal State: Communal Councils, Communes, and Workplace Democracy

The Communal State: Communal Councils, Communes, and Workplace Democracy

Uploaded by

Theodor Ludwig WCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Four Theories of The PressDocument8 pagesFour Theories of The PressAmeya Bal100% (6)

- The Future in Question - Fernando CoronilDocument39 pagesThe Future in Question - Fernando CoronilCarmen Ilizarbe100% (1)

- Conscripts of Western CivilizationDocument10 pagesConscripts of Western CivilizationtoufoulNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Dual Power StrategyDocument10 pagesAn Introduction To Dual Power StrategyMosi Ngozi (fka) james harrisNo ratings yet

- The Social and Political Imaginary of The Venezuelan RevolutionDocument12 pagesThe Social and Political Imaginary of The Venezuelan RevolutionLuis R DavilaNo ratings yet

- Chat Week 5Document51 pagesChat Week 5Raghaw KhattriNo ratings yet

- 2.4 - Markovic, Mihailo - Self-Governing Political System and De-Alienation in Yugoslavia (1950-1965) (En)Document17 pages2.4 - Markovic, Mihailo - Self-Governing Political System and De-Alienation in Yugoslavia (1950-1965) (En)Johann Vessant RoigNo ratings yet

- Andean Left Turns: Constituent Power and Constitution-MakingDocument31 pagesAndean Left Turns: Constituent Power and Constitution-MakingHenrry AllanNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism - A - Foucauldian - PerspectiveDocument16 pagesNeoliberalism - A - Foucauldian - PerspectiveGracedy GreatNo ratings yet

- Means and Ends: The Anarchist Critique of Seizing State PowerDocument7 pagesMeans and Ends: The Anarchist Critique of Seizing State Poweryout ubeNo ratings yet

- Four Stages in The Chávez Government's Approach To ParticipationDocument13 pagesFour Stages in The Chávez Government's Approach To ParticipationJavier Castro ArcosNo ratings yet

- Venezuela's Experiment in Participatory Democracy - WilpertDocument32 pagesVenezuela's Experiment in Participatory Democracy - WilpertGregory WilpertNo ratings yet

- Vaclav Havel: The Politician Practicizing CriticismDocument9 pagesVaclav Havel: The Politician Practicizing CriticismthesijNo ratings yet

- Venezuelas Social Transformation and Growing ClasDocument29 pagesVenezuelas Social Transformation and Growing ClasSamuel PepitoNo ratings yet

- Reevaluating The Chávez Regime: Participatory Democracy or Rentier Populism?Document17 pagesReevaluating The Chávez Regime: Participatory Democracy or Rentier Populism?Magaly Valdez SarabiaNo ratings yet

- Meg Mclagan and Yates MckeeDocument18 pagesMeg Mclagan and Yates MckeeVaniaMontgomeryNo ratings yet

- Left-Wing Populism Inclusion and Authoritarianism in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador Carlos de La TorreDocument16 pagesLeft-Wing Populism Inclusion and Authoritarianism in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador Carlos de La TorreDasha KNo ratings yet

- Reflections On The Venezuelan Transition From A Capitalist Representative To A Socialist Participatory Democracy, 2010Document27 pagesReflections On The Venezuelan Transition From A Capitalist Representative To A Socialist Participatory Democracy, 2010Lucio JuarezNo ratings yet

- New Social MovementsDocument4 pagesNew Social MovementsRyan Paul RufinoNo ratings yet

- Where Are Chavez and The Bolivarian Revolution Heading?: Johan Rivas, Socialismo Revolucionario (CWI in Venezuela)Document8 pagesWhere Are Chavez and The Bolivarian Revolution Heading?: Johan Rivas, Socialismo Revolucionario (CWI in Venezuela)Παρης ΜακριδηςNo ratings yet

- Hegel Civi SocieryDocument1 pageHegel Civi SocieryDanexNo ratings yet

- The Cadres Backbone of The Revolution - Che GuevaraDocument7 pagesThe Cadres Backbone of The Revolution - Che Guevarakashmir100% (2)

- Hugo Chávez As Postmodern PerónDocument3 pagesHugo Chávez As Postmodern Peróns73a1thNo ratings yet

- African Association of Political ScienceDocument30 pagesAfrican Association of Political ScienceJorge Acosta JrNo ratings yet

- Feminism and The Politics of Empowerment in International DevelopmentDocument18 pagesFeminism and The Politics of Empowerment in International Development1968LiliethNo ratings yet

- Kate NashDocument6 pagesKate NashUdhey MannNo ratings yet

- Polity NotesDocument11 pagesPolity NotesAshutosh ManiNo ratings yet

- NUGENT, David and Adeem Suhail - State FormationDocument9 pagesNUGENT, David and Adeem Suhail - State FormationAnonymous OeCloZYzNo ratings yet

- Leadership, Local Governance and Nation-BuildingDocument22 pagesLeadership, Local Governance and Nation-BuildingArvhie SantosNo ratings yet

- 15 - PC Farman Ullah - 52!1!15Document17 pages15 - PC Farman Ullah - 52!1!15saad aliNo ratings yet

- New Social Movements in NepalDocument13 pagesNew Social Movements in NepalsumanNo ratings yet

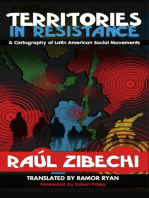

- Territories in Resistance: A Cartography of Latin American Social MovementsFrom EverandTerritories in Resistance: A Cartography of Latin American Social MovementsRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (1)

- 09 - The Role of Peoples OrganizationsDocument16 pages09 - The Role of Peoples OrganizationsGracia EmbudoNo ratings yet

- BUILDING ON THE BASICS Leadership, Local Governance and Nation-BuildingDocument23 pagesBUILDING ON THE BASICS Leadership, Local Governance and Nation-BuildingJoshua AmancioNo ratings yet

- The New Fascist MomentDocument6 pagesThe New Fascist MomentAna M. Fernandez-CebrianNo ratings yet

- Democracy Under Threat The Foundation ofDocument15 pagesDemocracy Under Threat The Foundation ofcardozorhNo ratings yet

- UCSP-Module 9Document6 pagesUCSP-Module 9angelabarientosNo ratings yet

- MondayDocument9 pagesMondaySaif EqbalNo ratings yet

- State of Power 2016: Democracy, Sovereignty and ResistanceFrom EverandState of Power 2016: Democracy, Sovereignty and ResistanceNo ratings yet

- Why We Need A New Theory of GovernmentDocument32 pagesWhy We Need A New Theory of GovernmentdecentturkishNo ratings yet

- Me The People How Populism Transforms DemocracyDocument273 pagesMe The People How Populism Transforms Democracytomasmoro73No ratings yet

- Jta People Power Final 28 JanDocument10 pagesJta People Power Final 28 JanVSPAN.asiaNo ratings yet

- Private Truths, Public Lies. The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification by Timur Kuran (Z-Lib - Org) - 4Document100 pagesPrivate Truths, Public Lies. The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification by Timur Kuran (Z-Lib - Org) - 4Henrique Freitas PereiraNo ratings yet

- The Thermidor of The Progressives: Managerialist Liberalism's Hostility To Decentralized OrganizationDocument48 pagesThe Thermidor of The Progressives: Managerialist Liberalism's Hostility To Decentralized OrganizationMimi BobekuninNo ratings yet

- Participatory Democracy Vs Representative DemocracyDocument5 pagesParticipatory Democracy Vs Representative DemocracyAdrianaArboleyaANo ratings yet

- Green Islam and Re Imagination of Khalifa Eco Politics and Muslim Youth Movements in South India by PK Sadique PDFDocument13 pagesGreen Islam and Re Imagination of Khalifa Eco Politics and Muslim Youth Movements in South India by PK Sadique PDFabdul basithNo ratings yet

- Class NOTES 5 October State DemoDocument4 pagesClass NOTES 5 October State DemoSaurav AnandNo ratings yet

- Unit-1 Social Movements - Meanings, Significance and ImportanceDocument6 pagesUnit-1 Social Movements - Meanings, Significance and Importanceshirish100% (1)

- Neo-Constitutionalism in Twenty-First Century Venezuela: Participatory Democracy, Deconcentrated Decentralization or Centralized Populism?Document26 pagesNeo-Constitutionalism in Twenty-First Century Venezuela: Participatory Democracy, Deconcentrated Decentralization or Centralized Populism?Mily NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Unit-2 Approaches To Study Social Movements Liberal, Gandhian and MarxianDocument8 pagesUnit-2 Approaches To Study Social Movements Liberal, Gandhian and MarxianJai Dev100% (1)

- The PeopleDocument2 pagesThe PeopleBTSAANo ratings yet

- HTTP Rccsar Revues Org 95Document18 pagesHTTP Rccsar Revues Org 95SurangaWeerasooriyaNo ratings yet

- 2013, Social Movements, Party Organization, and Populism, Insights From The Bolivian MASDocument29 pages2013, Social Movements, Party Organization, and Populism, Insights From The Bolivian MASAlba OsunaNo ratings yet

- Yugoslavia's Self-Management: Daniel JakopovichDocument7 pagesYugoslavia's Self-Management: Daniel JakopovichJose BarreraNo ratings yet

- Document 2Document2 pagesDocument 2stacysacayNo ratings yet

- Democracy, Indigenous Movements, and The Postliberal Challenge in Latin America by Deborah J. YasharDocument23 pagesDemocracy, Indigenous Movements, and The Postliberal Challenge in Latin America by Deborah J. YasharChrisálida LycaenidaeNo ratings yet

- Our Road To PowerDocument16 pagesOur Road To PowerCristóbal Karle SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism and The State: Martijn KoningsDocument14 pagesNeoliberalism and The State: Martijn KoningsAlexy Angle SkyNo ratings yet

- Charlatan Stew True and False in VenezuelaDocument9 pagesCharlatan Stew True and False in VenezueladefoemollyNo ratings yet

- Transformations in Capital AccumulationDocument20 pagesTransformations in Capital AccumulationTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- On Fred Moseleys Money and Totality A Ma PDFDocument18 pagesOn Fred Moseleys Money and Totality A Ma PDFTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Dismissals of The Congress For Cultural Freedom's Representatives in Latin America As Part of The Strategy of "Opening To The Left" (1961-1964)Document8 pagesDismissals of The Congress For Cultural Freedom's Representatives in Latin America As Part of The Strategy of "Opening To The Left" (1961-1964)Theodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- (Doi 10.2307 - 40404536) Cheol-Soo Park - The New Value Controversy and The Foundations of Economicsby Alan Freeman Andrew Kliman Julian WellsDocument4 pages(Doi 10.2307 - 40404536) Cheol-Soo Park - The New Value Controversy and The Foundations of Economicsby Alan Freeman Andrew Kliman Julian WellsTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Volume 2 Number 2 2017Document4 pagesVolume 2 Number 2 2017Theodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Lenin and SpainDocument14 pagesLenin and SpainTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Theodor W. Adorno On Marx and The Basic Concepts of Sociological Theory'Document11 pagesTheodor W. Adorno On Marx and The Basic Concepts of Sociological Theory'Theodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Art and The Possibility of A Liberated Nature: Camilla Flodin Uppsala UniversityDocument15 pagesArt and The Possibility of A Liberated Nature: Camilla Flodin Uppsala UniversityTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Takao Abe - The Jesuit Mission To New France - A New Interpretation in The Light of The Earlier Jesuit Experience in Japan (Studies in The History ofDocument243 pagesTakao Abe - The Jesuit Mission To New France - A New Interpretation in The Light of The Earlier Jesuit Experience in Japan (Studies in The History ofTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Tony Cliff's Family TreeDocument1 pageTony Cliff's Family TreeTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Theories and Methods of African Conceptual History: Rhiannon Stephens and Axel FleischDocument20 pagesTheories and Methods of African Conceptual History: Rhiannon Stephens and Axel FleischTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 5Document14 pagesWorksheet 5HiraiNo ratings yet

- Political Ideologies: What I Need To KnowDocument16 pagesPolitical Ideologies: What I Need To KnowVictoria Quebral CarumbaNo ratings yet

- Russian Revolution and Impact On Indian Freedom Struggle PDFDocument1 pageRussian Revolution and Impact On Indian Freedom Struggle PDFjashish911No ratings yet

- Marxist Criticism PresentationDocument43 pagesMarxist Criticism PresentationSheila Mae PaltepNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Trotskyism: Its Anti-Revolutionary NatureDocument214 pagesContemporary Trotskyism: Its Anti-Revolutionary NatureRodrigo Pk100% (1)

- Higher SuperstitionDocument47 pagesHigher SuperstitionsujupsNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Indian FeminismDocument11 pagesContemporary Indian FeminismArchana RajarajanNo ratings yet

- Leninism Under Lenin by Marcel LiebmanDocument479 pagesLeninism Under Lenin by Marcel LiebmanSergioNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Political IdeologiesDocument60 pagesLesson 2 - Political IdeologiesRuschelle Lao100% (1)

- Taguieff 1995Document35 pagesTaguieff 1995Tatiana S. Leal100% (1)

- The Recovery of Western MarxismDocument3 pagesThe Recovery of Western MarxismBen RosenzweigNo ratings yet

- Internal Assignment Batch BDocument3 pagesInternal Assignment Batch BAadhitya NarayananNo ratings yet

- Assignment # 1 Submitted By: F2019266364: Totalitarianism, Form of Government That Theoretically Permits NoDocument3 pagesAssignment # 1 Submitted By: F2019266364: Totalitarianism, Form of Government That Theoretically Permits NoRizwan KhadimNo ratings yet

- Communism The Vanishing Specter PDFDocument2 pagesCommunism The Vanishing Specter PDFDavidNo ratings yet

- Stalins Rise To PowerDocument2 pagesStalins Rise To PowerBecnash100% (1)

- Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism in South America - S. Fanny SimonDocument22 pagesAnarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism in South America - S. Fanny SimonTravihzNo ratings yet

- Feudalism PDFDocument2 pagesFeudalism PDFKomal MeenaNo ratings yet

- Socialism 102 RevisionDocument2 pagesSocialism 102 RevisionCammeron Anthony VaughnNo ratings yet

- (Historical Materialism Book Series) Jacob A. Zumoff - The Communist International and US Communism, 1919-1929 (2015, Brill)Document455 pages(Historical Materialism Book Series) Jacob A. Zumoff - The Communist International and US Communism, 1919-1929 (2015, Brill)abelNo ratings yet

- M.N. RoyDocument5 pagesM.N. RoyAyush ShrimalNo ratings yet

- Russian RevolutionDocument12 pagesRussian Revolution41-Pragya Yadav-9ENo ratings yet

- Animal Farm Introduction and Allegory ChartDocument4 pagesAnimal Farm Introduction and Allegory ChartmohamedNo ratings yet

- Historyvslenin ScriptDocument2 pagesHistoryvslenin Scriptapi-271959377No ratings yet

- Animal Farm Vs Russian Revolution ParallelsDocument15 pagesAnimal Farm Vs Russian Revolution ParallelsAnas HudsonNo ratings yet

- Capitalism and Communism in Hunger GamesDocument3 pagesCapitalism and Communism in Hunger GamesBen100% (1)

- Lipset - The Changing Class StructureDocument34 pagesLipset - The Changing Class Structurepopolovsky100% (1)

- The Fetish of The Margins: Religious Absolutism, Anti-Racism and Postcolonial Silence by Chetan BhattDocument27 pagesThe Fetish of The Margins: Religious Absolutism, Anti-Racism and Postcolonial Silence by Chetan Bhatt5705robinNo ratings yet

- AJITH - Against AvakianismDocument256 pagesAJITH - Against AvakianismPaulo Henrique FloresNo ratings yet

- Katsiaficas) The Subversion of Politics Study GroupDocument230 pagesKatsiaficas) The Subversion of Politics Study GroupKathy SorrellNo ratings yet

The Communal State: Communal Councils, Communes, and Workplace Democracy

The Communal State: Communal Councils, Communes, and Workplace Democracy

Uploaded by

Theodor Ludwig WOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Communal State: Communal Councils, Communes, and Workplace Democracy

The Communal State: Communal Councils, Communes, and Workplace Democracy

Uploaded by

Theodor Ludwig WCopyright:

Available Formats

Chavismo After Chávez

The “IV National Meeting of Comunars,” from July 29 to 31 July, 2011, in the Municipality of Torres (Lara). Photo By Dario Azzellini

The Communal State: Communal Councils,

Communes, and Workplace Democracy

Dario Azzellini

T he particular character of what Hugo

Chávez called the Bolivarian process lies in the

understanding that social transformation can

be constructed from two directions, “from above” and

“from below.” Bolivarianism—or Chavismo—includes

approaches, both of which see the state as the central

agent of change; it differs as well from movement-based

approaches that conceive of no role whatsoever for the

state in a process of revolutionary change.

The current transformation in Venezuela is thus the

among its participants both traditional organizations product of a tension between constituent and constituted

and new autonomous groups; it encompasses both state- power, with the principal agent of change being the con-

centric and anti-systemic currents. The process thus stituent. Constituent power is the legitimate collective

differs from traditional Leninist or social democratic creative capacity of human beings expressed in move-

ments and in the organized social base to create some-

thing new without having to derive it from something

Dario Azzellini is a visiting fellow at the CUNY Graduate Center previously existing. In the Bolivarian process, the con-

and works at the Johannes Kepler University (Linz, Austria). He stituted power—the state and its institutions—accompa-

has published several books and journal articles about popu- nies the organized population; it must be the facilitator of

lar movements, workers control, local self administration, and bottom-up processes, so that the constituent power can

privatization of military services, with a regional focus on Latin bring forward the steps needed to transform society.

Summer 2013 NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS 25

This approach was elaborated on various occasions can be today, the goal was defined as “socialism of the

by former president Hugo Chávez and has been con- 21st century,” which is an ongoing project. The name

firmed by his successor, Nicolás Maduro, during the also serves to distinguish it from the “real socialisms” of

recent electoral campaign. It is shared by sectors of the the 20th century. The process of seeking and building is

administration and by the majority of the organized guided above all by values such as collectivity, equality,

movements. Both from the government and from the solidarity, freedom, and sovereignty.3 It is embodied in

rank and file of the Bolivarian process, there is a declared the construction of councils.

commitment to redefine state and society on the basis of In January 2007, Chávez proposed to go beyond the

an interrelation between top and bottom and thereby to bourgeois state by building the communal state. He thus

move toward transcending capitalist relations. Although picked up and applied more widely a concern originat-

not free of contradictions and conflicts, this two-track ing with anti-systemic forces. The main idea was to

approach has been able to uphold and deepen the pro- form council structures of all kinds (communal coun-

cess of social transformation in Venezuela. cils, communes, and communal cities, for example), as

Constituent power, being comprehensive and ex- bottom up structures of self-administration. Councils of

pansive, has been the fundament for every revolu- workers, students, peasants, and women, among others,

tion, democracy, and republic; it is the greatest motor would then have to cooperate and coordinate on a high-

of history, the most powerful, innovative social force. er level in order to gradually replace the bourgeois state

Historically, however, we have seen constituent powers with a communal state. According to the National Plan

silenced and weakened after barely carrying out their for Economic and Social Development 2007-2013, “since

role of legitimating the constituted power. In a genuine sovereignty resides absolutely in the people, the people

revolutionary process, however, the constituent power can itself direct the state, without needing to delegate

must maintain its capacity to intervene and to shape its sovereignty as it does in indirect or representative

the present, to create something new that does not de- democracy.”4

rive from the old. This is what defines revolution: not The notion of a separation between “civil society”

the act of taking power, but rather a broad process of and “political society”—as expressed, for example,

constructing the new, an act of creation and invention.1 by NGOs—is thus rejected. The focus is rather upon

This is the global legacy of the Bolivarian process. fostering the potential and the direct capacity of the

In Venezuela, the concept of constituent power arose popular base to analyze, decide, implement, and evalu-

at the end of the 1980s as the defining trait of a continu- ate what is relevant to its life. The constituent power

ous process of social transformation. The main slogan is embodied in councils, in the institutions of popular

of the neighborhood assemblies was “We don’t want to power, and in the basic concept of the communal state.

be a government, we want to govern.” This idea, under- As was proposed in the constitutional reform that was

stood in increasingly radical terms, came to orient the rejected in the 2007 referendum, the future communal

revolutionary transformation, acquiring a hegemonic state must be subordinated to popular power, which

status in the political-ideological debate of the 1990s.2 replaces bourgeois civil society.5 This would overcome

The Bolivarian process began by calling for a strength- the rift between the economic, the social, and the politi-

ening of civil and human rights and for the building cal—between civil society and political society—which

of a “participatory and protagonistic democracy” in underlies capitalism and the bourgeois state. It would

search of a “third way” beyond capitalism and socialism. also prevent, at the same time, the over-centralization

Starting in late 2005, however, President Hugo Chávez that characterized the countries of “real socialism.”6

T

described socialism as the only alternative for bringing

about the necessary transcendence of capitalism. The he communal councils are a non-

presidential election of 2006 was defined by Chávez representative structure of direct democracy

as a choice between capitalism and a path towards so- and the most advanced mechanism of

cialism. The onset of the era of Chávez’s presidency ex- self-organization at the local level in Venezuela. In

panded and reinforced participatory possibilities and 2013, approximately 44,000 communal councils

council structures and created new ones. The idea of had been established throughout the country. Since

participation was officially defined in terms of popu- the new constitution of 1999 defined Venezuela as a

lar power, revolutionary democracy, and socialism. “participative and protagonistic democracy,” a variety

Because of the obvious difficulties of defining a clear of mechanisms for the participation of the population

path to socialism or a clear concept of what socialism in local administration and decision-making have been

26 NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS VOL. 46, NO. 2

experimented with. In the beginning they were connected state. In fact, however, they constitute a parallel struc-

to local representative authorities and integrated into the ture through which power and control is gradually drawn

institutional framework of representative democracy. away from the state in order to govern on their own.7

Competing on the same territory as local authorities and At a higher level of self-government there is the pos-

depending on the finances authorized by those bodies, sibility of creating socialist communes, which can be

the different initiatives showed little success. formed by combining various communal councils in a

Communal councils began forming in 2005 as an specific territory. The councils decide themselves about

initiative “from below.” In different parts of Venezuela, the geography of these communes. These communes

rank-and-file organizations, on their own, promoted can develop medium and long-term projects of greater

forms of local self-administration named “local govern- impact while decisions continue to be made in assem-

ments” or “communitarian governments.” During 2005, blies of the communal councils. As of 2013 there are

one department of the city administration of Caracas more than 200 communes under construction.

focused on promoting this proposal in the poor neigh- In the context of the creation of communes and com-

borhoods of the city. In January 2006, Chávez adopted munal cities, it is important to analytically distinguish

this initiative and began to spread it. On his weekly TV between (absolute) political-administrative space and

show, “Aló Presidente,” Chávez presented the commu- socio-cultural-economic (relational) space.8 Communes

nal councils—consejos comunales—as a kind of “good reflect the latter; their boundaries do not necessarily

practice.” At this point some 5,000 communal councils correspond to existing political-administrative spaces.

already existed. In April 2006, the National Assembly As these continue to exist, the institutionalization of the

approved the Law of Communal Councils, which was communal councils, communes, and communal cities

reformed in 2009 following a broad consulting process develops and shapes the socio-cultural-economic space.

Thus, the idea of council-based non-

representative local self-organization

Not surprisingly, the deepening of social creates a “new power-geometry.” The

concept of power in human geogra-

transformation multiplies the points of phy, as elaborated by Doreen Massey,

confrontation between top-down and has been put “to positive political

use” following the “recognition of

bottom-up strategies. the existence and significance, with-

in Venezuela, of highly unequal, and

of councils’ spokespeople. The communal councils in thus undemocratic, power-geometries.”9

urban areas encompass 150-400 families; in rural zones, Various communes can form communal cities, with

a minimum of 20 families; and in indigenous zones, at administration and planning “from below” if the entire

least 10 families. The councils build a non-representa- territory is organized in communal councils and com-

tive structure of direct participation that exists parallel to munes. The mechanism of the construction of com-

the elected representative bodies of constituted power. munes and communal cities is flexible; they themselves

The communal councils are financed directly by na- define their tasks. Thus the construction of self-govern-

tional state institutions, thus avoiding interference from ment begins with what the population itself considers

municipal organs. The law does not give any entity the most important, necessary, or opportune. The commu-

authority to accept or reject proposals presented by the nal cities that have begun to form so far, for example, are

councils. The relationship between the councils and rural and are structured around agriculture, such as the

established institutions, however, is not always harmo- Ciudad Comunal Campesina Socialista Simón Bolívar

nious; conflicts arise principally from the slowness of in the southern state of Apure or the Ciudad Comunal

constituted power to respond to demands made by the Laberinto in the northwestern state of Zulia. Organizing

councils and from attempts at interference. The com- and the construction of communes and communal cities

munal councils tend to transcend the division between has been easier in suburban and rural areas than in met-

political and civil society (i.e., between those who gov- ropolitan areas, since there is less distraction and less

ern and those who are governed). Hence, liberal analysts presence of opposition, while at the same time common

who support that division view the communal councils interests are easier to define.

in a negative light, arguing that they are not independent

civil-society organizations, but rather are linked to the

Summer 2013 NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS 27

Organopónicos—a system of urban organic gardens to grow food—in the Caracas city center, in front of the former Hilton Hotel

(now Hotel Alba) and managed by a workers cooperative. Photo By Dario Azzellini. 2010

R egarding the democratization

ownership and administration of the means

of production, Venezuela has experimented

with a series of different models. Between 2001 and

2006, the Venezuelan government—in addition

of the satisfaction of social needs and that their internal

solidarity based on collective property would extend

to their local communities, proved to be an error.

Most cooperatives still followed the logic of capital;

concentrating on the maximization of net revenue

to asserting state control over the core of the oil without supporting the surrounding communities,

industry—focused on promoting cooperatives for any many failed to integrate new members.11 In the light of

type of company, including models of cooperatives co- these experiences the government’s focus in supporting

administrated with the state or private entrepreneurs. the creation of cooperatives switched to cooperatives

The 1999 constitution assigned the cooperatives a controlled and owned by the communities.

special weight. They were conceived as contributing to In response to the employers’ lockout of 2002–2003,

a new social and economic balance, and thus received the “entrepreneurs strike,” with the stated intention of

massive state assistance. The favorable conditions led to toppling the Chávez government, workers began the

a boom in the number of cooperatives founded. In mid- process of taking over workplaces abandoned by their

2010, according to the national cooperative supervisory owners. At first, the government relegated the cases to

institute Sunacoop, 73,968 cooperatives were certified as the labor courts, and then in January 2005 began ex-

operative, with an estimated total of 2 million members, propriations. Beginning in July 2005, the government

although some people participated in more than one began to pay special attention to the situation of closed

cooperative and were thus counted twice.10 The initial businesses, and since then hundreds of such compa-

idea that cooperatives would automatically produce for nies have been expropriated. But a systematic policy for

28 NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS VOL. 46, NO. 2

expropriations in the productive sector did not exist un- are collective property of the communities, which de-

til 2007. The expropriated enterprises are officially sup- cide on the organizational structure of enterprises, the

posed to be turned into “direct social property” under workers incorporated and the eventual use of profits.

the direct control of workers and communities. In real- Government enterprises and institutions have pro-

ity most of them are not administered by workers and moted the communal enterprises since 2009, and since

communities but by state institutions. Working condi- 2013 several thousand EPSC have been constituted.

tions have not fundamentally changed, and expropria- Most belong to the sectors of community services like

tions have not automatically produced co-management public transport or are engaged in food production and

or workers’ control. food processing. The state-owned oil company, PDSVA,

The concept of “direct social property” is also sup- set up a local liquid gas distribution administered by

posed to apply to hundreds of new “socialist factories” communities call Gas Comunal.13

built by the government in the context of an overarch- Since 2007, the government’s ability to reform has

ing strategy of industrialization. The local communal increasingly clashed with the limitations inherent in

councils select the workers, while the required profes- the bourgeois state and the capitalist system. The move-

sionals are drawn from state and government institu- ments and initiatives for self-management and self-gov-

tions. The aim is to gradually transfer the administra- ernment, designed to overcome the bourgeois state and

tion of the factories into the hands of organized workers its institutions, with the goal of replacing it with a com-

and communities. But most state institutions involved munal state based on popular power, have grown. The

do little to organize this process or prepare the employ- broadening of direct grassroots participation brings

ees, which has generated growing conflicts between an increase in the conflicts between the state and its

workers and institutions. popular base (especially in the sphere of production)

In 2007, Chávez picked up the idea of “socialist as well as within the state itself, which becomes a site

workers councils,” which was already being discussed of class conflict. Not surprisingly, the deepening of

by many rank-and-file workers and by existing coun- social transformation multiplies the points of confron-

cils and workers’ initiatives. In fact, there was a net- tation between top-down and bottom-up strategies.

work with the same name: Socialist Workers Councils But simultaneously, because of the expansion of state

(CST). Chávez presented CST as a good practice and institutions’ work along with the consolidation of the

called on workers to form CST at their workplaces. Bolivarian process and growing resources, state insti-

Nevertheless, since most institutions were opposed to tutions have been generally strengthened and have be-

workers councils, only a few councils were formed at come more bureaucratized. Institutions of constituted

the beginning, mainly in recovered factories like the power aim at controlling social processes and repro-

valve factory, Inveval, or the water pipe factory, Inefa. ducing themselves. Since the institutions of constituted

Growing pressure from below led several government power are at the same time strengthening and limiting

institutions to start to accept or even promote the cre- constituent power, the transformation process is very

ation of workers councils in institutionally administered complex and contradictory.

workplaces, even without the benefit of an enacted law Institutions, as well as many individuals in charge

on workers councils. But while on the one hand the ma- in institutions, follow an inherent logic of perpetuating

jority of institutions tried to prevent the constitution of and expanding their institutional power and control to

workers councils in their workplaces, in others, and in guarantee the institution’s survival. Or as Thamara Esis,

state administered enterprises, the institutions often tried a consejo comunal activist from Caracas explains in a per-

to assume the lead and constitute the CST themselves. sonal interview, “These nice people who already made

This move represented an attempt to distort the councils’ themselves comfortable in their offices, are not willing

purpose and reduce them to a representative authority to renounce their benefits, they live on the needs of the

dealing with work and salary related questions within people. It is like a little enterprise, you understand?” This

the government bureaucracy. As a consequence, the CST tendency is strengthened in times of profound structural

turned into another site of struggle for workers control.12 changes when the purpose and existence of any institu-

The most successful attempt at a democratization of tion is questioned in the context of transformation.

ownership and administration of the means of produc- In fact, the Ministry of Communes turns out to be

tion is the model of Enterprises of Communal Social one of the biggest obstacles to the construction of com-

Property (EPSC), promoted to create local production munes and most of the communes under construc-

units and community services enterprises. The EPSC tion complain about the Ministry. Only the growing

Summer 2013 NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS 29

organization “from below,” especially the self-orga-

nized network of commune activists that brings togeth-

er about 70 communes could bring enough pressure on

the Ministry of Communes to start changing its politics

at the end of 2011. They forced the ministry to regis-

ter some 20 communes. In return, the communes had

to set up the registration sheet since the Ministry of

Communes not only did not register any communes in

the first three years of it’s existence, but one year after

the law on communes had been released, it had not

even created an official procedure for the registration

of communes.

Nevertheless, strategies “from above” and “from

below” have maintained themselves in the same pro-

cess of transformation for 14 years and the conflictive

relationship between constituent and constituted

power has been the motor of the Bolivarian process.

In his government plan for 2013-2019, presented dur-

ing the electoral campaign for the 2012 presidential

elections, Chávez stated clearly “We should not be-

tray ourselves: the still dominant socio-economic for-

mation in Venezuela is of capitalist and rentist char-

acter.”14 In order to move further towards socialism,

Chávez underlined the necessity to advance in the

construction of communal councils, communes and

communal cities, and the “development of social

property on the basic and strategic factors and means

of production.”15 His successor, Nicolás Maduro, com-

mitted to the program, and one of the central slogans

School funded by Venezuela in the Indigenous region of

of the movements supporting his electoral campaign

Dominica. Photo By Dario Azzellini. 2010

was “Comuna o nada”.

1. Antonio Negri, Il Potere Costituente (Carnago: 8. David Harvey, “Space as a keyword,” in David mia Solidária na América Latina: realidades

Sugarco Edizioni, 1992), 382. Harvey. A Critical Reader, ed. Noel Castree and nacionais e políticas públicas, ed. Sidney Lianza

2. Roland Denis, Los fabricantes de la rebelión (Ca- Derek Gregory, (Malden: Blackwell, 2006). and Flávio Chedid Henriques, (Rio de Janeiro:

racas: Primera Linea, 2001), 65. 9. Doree Massey, “Concepts of space and power Pró Reitoria de Extensão UFRJ, 2012): 147-160;

3. Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Comuni- in theory and in political practice,” Doc. Anàl. 12. Dario Azzellini, “De la Cogestión al Control

cación y la Información, “Líneas generales del Geogr 55 (2009): 20. Obrero. Lucha de clases al interior del proceso

Plan de Desarrollo Económico y Social de la 10. Interview with Juan Carlos Baute. Presidente bolivariano,” (PhD diss., Benemérita Universidad

Nación 2007-2013,” (Caracas: MinCI, 2007), 30. de Sunacoop, accessed January 16, 2009, Autónoma de Puebla, 2012), 183-196.

4. MinCI, Líneas generales, 30. http://www.sunacoop.gob.ve/noticias_detalle. 13. Aurelio Gil Beróes, “Los Consejos Comunales

5. Asamblea Nacional Dirección General de Inves- php?id=1361. deberán funcionar como bujías de la economía

tigación y Desarrollo Legislativo, “Ejes Funda- 11. Dario Azzellini, “From Cooperatives to Enterpri- socialista,” accessed January 4, 2010 http://

mentales del Proyecto de Reforma Constitucio- ses of Direct Social Property in the Venezuelan www.rebelion.org/noticia.php?id=98094.

nal. Consolidación del Nuevo Estado,” (Caracas: Process,” in Cooperatives and Socialism. A View 14. Aurelio Gil Beróes, “Los Consejos Comunales

AN-DGIDL, 2007). from Cuba, ed. Camila Piñeiro Harnecker, (Ba- deberán funcionar como bujías de la economía

6. Hugo Chávez, El Poder Popular (Caracas: Minis- singstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012): 259-278; socialista,” accessed January 4, 2010 http://

terio de Comunicación e Información, 2008), 38. Dario Azzellini, “Economía solidaria en Venezue- www.rebelion.org/noticia.php?id=98094.

7. Dario Azzellini, Partizipation, Arbeiterkontrolle la: Del apoyo al cooperativismo tradicional a la 15. “Propuesta del Candidato,” Chávez, 7.

und die Commune, (Hamburg: VSA, 2010). construcción de ciclos comunales,” in A Econo-

30 NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS VOL. 46, NO. 2

You might also like

- Four Theories of The PressDocument8 pagesFour Theories of The PressAmeya Bal100% (6)

- The Future in Question - Fernando CoronilDocument39 pagesThe Future in Question - Fernando CoronilCarmen Ilizarbe100% (1)

- Conscripts of Western CivilizationDocument10 pagesConscripts of Western CivilizationtoufoulNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Dual Power StrategyDocument10 pagesAn Introduction To Dual Power StrategyMosi Ngozi (fka) james harrisNo ratings yet

- The Social and Political Imaginary of The Venezuelan RevolutionDocument12 pagesThe Social and Political Imaginary of The Venezuelan RevolutionLuis R DavilaNo ratings yet

- Chat Week 5Document51 pagesChat Week 5Raghaw KhattriNo ratings yet

- 2.4 - Markovic, Mihailo - Self-Governing Political System and De-Alienation in Yugoslavia (1950-1965) (En)Document17 pages2.4 - Markovic, Mihailo - Self-Governing Political System and De-Alienation in Yugoslavia (1950-1965) (En)Johann Vessant RoigNo ratings yet

- Andean Left Turns: Constituent Power and Constitution-MakingDocument31 pagesAndean Left Turns: Constituent Power and Constitution-MakingHenrry AllanNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism - A - Foucauldian - PerspectiveDocument16 pagesNeoliberalism - A - Foucauldian - PerspectiveGracedy GreatNo ratings yet

- Means and Ends: The Anarchist Critique of Seizing State PowerDocument7 pagesMeans and Ends: The Anarchist Critique of Seizing State Poweryout ubeNo ratings yet

- Four Stages in The Chávez Government's Approach To ParticipationDocument13 pagesFour Stages in The Chávez Government's Approach To ParticipationJavier Castro ArcosNo ratings yet

- Venezuela's Experiment in Participatory Democracy - WilpertDocument32 pagesVenezuela's Experiment in Participatory Democracy - WilpertGregory WilpertNo ratings yet

- Vaclav Havel: The Politician Practicizing CriticismDocument9 pagesVaclav Havel: The Politician Practicizing CriticismthesijNo ratings yet

- Venezuelas Social Transformation and Growing ClasDocument29 pagesVenezuelas Social Transformation and Growing ClasSamuel PepitoNo ratings yet

- Reevaluating The Chávez Regime: Participatory Democracy or Rentier Populism?Document17 pagesReevaluating The Chávez Regime: Participatory Democracy or Rentier Populism?Magaly Valdez SarabiaNo ratings yet

- Meg Mclagan and Yates MckeeDocument18 pagesMeg Mclagan and Yates MckeeVaniaMontgomeryNo ratings yet

- Left-Wing Populism Inclusion and Authoritarianism in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador Carlos de La TorreDocument16 pagesLeft-Wing Populism Inclusion and Authoritarianism in Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador Carlos de La TorreDasha KNo ratings yet

- Reflections On The Venezuelan Transition From A Capitalist Representative To A Socialist Participatory Democracy, 2010Document27 pagesReflections On The Venezuelan Transition From A Capitalist Representative To A Socialist Participatory Democracy, 2010Lucio JuarezNo ratings yet

- New Social MovementsDocument4 pagesNew Social MovementsRyan Paul RufinoNo ratings yet

- Where Are Chavez and The Bolivarian Revolution Heading?: Johan Rivas, Socialismo Revolucionario (CWI in Venezuela)Document8 pagesWhere Are Chavez and The Bolivarian Revolution Heading?: Johan Rivas, Socialismo Revolucionario (CWI in Venezuela)Παρης ΜακριδηςNo ratings yet

- Hegel Civi SocieryDocument1 pageHegel Civi SocieryDanexNo ratings yet

- The Cadres Backbone of The Revolution - Che GuevaraDocument7 pagesThe Cadres Backbone of The Revolution - Che Guevarakashmir100% (2)

- Hugo Chávez As Postmodern PerónDocument3 pagesHugo Chávez As Postmodern Peróns73a1thNo ratings yet

- African Association of Political ScienceDocument30 pagesAfrican Association of Political ScienceJorge Acosta JrNo ratings yet

- Feminism and The Politics of Empowerment in International DevelopmentDocument18 pagesFeminism and The Politics of Empowerment in International Development1968LiliethNo ratings yet

- Kate NashDocument6 pagesKate NashUdhey MannNo ratings yet

- Polity NotesDocument11 pagesPolity NotesAshutosh ManiNo ratings yet

- NUGENT, David and Adeem Suhail - State FormationDocument9 pagesNUGENT, David and Adeem Suhail - State FormationAnonymous OeCloZYzNo ratings yet

- Leadership, Local Governance and Nation-BuildingDocument22 pagesLeadership, Local Governance and Nation-BuildingArvhie SantosNo ratings yet

- 15 - PC Farman Ullah - 52!1!15Document17 pages15 - PC Farman Ullah - 52!1!15saad aliNo ratings yet

- New Social Movements in NepalDocument13 pagesNew Social Movements in NepalsumanNo ratings yet

- Territories in Resistance: A Cartography of Latin American Social MovementsFrom EverandTerritories in Resistance: A Cartography of Latin American Social MovementsRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (1)

- 09 - The Role of Peoples OrganizationsDocument16 pages09 - The Role of Peoples OrganizationsGracia EmbudoNo ratings yet

- BUILDING ON THE BASICS Leadership, Local Governance and Nation-BuildingDocument23 pagesBUILDING ON THE BASICS Leadership, Local Governance and Nation-BuildingJoshua AmancioNo ratings yet

- The New Fascist MomentDocument6 pagesThe New Fascist MomentAna M. Fernandez-CebrianNo ratings yet

- Democracy Under Threat The Foundation ofDocument15 pagesDemocracy Under Threat The Foundation ofcardozorhNo ratings yet

- UCSP-Module 9Document6 pagesUCSP-Module 9angelabarientosNo ratings yet

- MondayDocument9 pagesMondaySaif EqbalNo ratings yet

- State of Power 2016: Democracy, Sovereignty and ResistanceFrom EverandState of Power 2016: Democracy, Sovereignty and ResistanceNo ratings yet

- Why We Need A New Theory of GovernmentDocument32 pagesWhy We Need A New Theory of GovernmentdecentturkishNo ratings yet

- Me The People How Populism Transforms DemocracyDocument273 pagesMe The People How Populism Transforms Democracytomasmoro73No ratings yet

- Jta People Power Final 28 JanDocument10 pagesJta People Power Final 28 JanVSPAN.asiaNo ratings yet

- Private Truths, Public Lies. The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification by Timur Kuran (Z-Lib - Org) - 4Document100 pagesPrivate Truths, Public Lies. The Social Consequences of Preference Falsification by Timur Kuran (Z-Lib - Org) - 4Henrique Freitas PereiraNo ratings yet

- The Thermidor of The Progressives: Managerialist Liberalism's Hostility To Decentralized OrganizationDocument48 pagesThe Thermidor of The Progressives: Managerialist Liberalism's Hostility To Decentralized OrganizationMimi BobekuninNo ratings yet

- Participatory Democracy Vs Representative DemocracyDocument5 pagesParticipatory Democracy Vs Representative DemocracyAdrianaArboleyaANo ratings yet

- Green Islam and Re Imagination of Khalifa Eco Politics and Muslim Youth Movements in South India by PK Sadique PDFDocument13 pagesGreen Islam and Re Imagination of Khalifa Eco Politics and Muslim Youth Movements in South India by PK Sadique PDFabdul basithNo ratings yet

- Class NOTES 5 October State DemoDocument4 pagesClass NOTES 5 October State DemoSaurav AnandNo ratings yet

- Unit-1 Social Movements - Meanings, Significance and ImportanceDocument6 pagesUnit-1 Social Movements - Meanings, Significance and Importanceshirish100% (1)

- Neo-Constitutionalism in Twenty-First Century Venezuela: Participatory Democracy, Deconcentrated Decentralization or Centralized Populism?Document26 pagesNeo-Constitutionalism in Twenty-First Century Venezuela: Participatory Democracy, Deconcentrated Decentralization or Centralized Populism?Mily NaranjoNo ratings yet

- Unit-2 Approaches To Study Social Movements Liberal, Gandhian and MarxianDocument8 pagesUnit-2 Approaches To Study Social Movements Liberal, Gandhian and MarxianJai Dev100% (1)

- The PeopleDocument2 pagesThe PeopleBTSAANo ratings yet

- HTTP Rccsar Revues Org 95Document18 pagesHTTP Rccsar Revues Org 95SurangaWeerasooriyaNo ratings yet

- 2013, Social Movements, Party Organization, and Populism, Insights From The Bolivian MASDocument29 pages2013, Social Movements, Party Organization, and Populism, Insights From The Bolivian MASAlba OsunaNo ratings yet

- Yugoslavia's Self-Management: Daniel JakopovichDocument7 pagesYugoslavia's Self-Management: Daniel JakopovichJose BarreraNo ratings yet

- Document 2Document2 pagesDocument 2stacysacayNo ratings yet

- Democracy, Indigenous Movements, and The Postliberal Challenge in Latin America by Deborah J. YasharDocument23 pagesDemocracy, Indigenous Movements, and The Postliberal Challenge in Latin America by Deborah J. YasharChrisálida LycaenidaeNo ratings yet

- Our Road To PowerDocument16 pagesOur Road To PowerCristóbal Karle SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Neoliberalism and The State: Martijn KoningsDocument14 pagesNeoliberalism and The State: Martijn KoningsAlexy Angle SkyNo ratings yet

- Charlatan Stew True and False in VenezuelaDocument9 pagesCharlatan Stew True and False in VenezueladefoemollyNo ratings yet

- Transformations in Capital AccumulationDocument20 pagesTransformations in Capital AccumulationTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- On Fred Moseleys Money and Totality A Ma PDFDocument18 pagesOn Fred Moseleys Money and Totality A Ma PDFTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Dismissals of The Congress For Cultural Freedom's Representatives in Latin America As Part of The Strategy of "Opening To The Left" (1961-1964)Document8 pagesDismissals of The Congress For Cultural Freedom's Representatives in Latin America As Part of The Strategy of "Opening To The Left" (1961-1964)Theodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- (Doi 10.2307 - 40404536) Cheol-Soo Park - The New Value Controversy and The Foundations of Economicsby Alan Freeman Andrew Kliman Julian WellsDocument4 pages(Doi 10.2307 - 40404536) Cheol-Soo Park - The New Value Controversy and The Foundations of Economicsby Alan Freeman Andrew Kliman Julian WellsTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Volume 2 Number 2 2017Document4 pagesVolume 2 Number 2 2017Theodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Lenin and SpainDocument14 pagesLenin and SpainTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Theodor W. Adorno On Marx and The Basic Concepts of Sociological Theory'Document11 pagesTheodor W. Adorno On Marx and The Basic Concepts of Sociological Theory'Theodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Art and The Possibility of A Liberated Nature: Camilla Flodin Uppsala UniversityDocument15 pagesArt and The Possibility of A Liberated Nature: Camilla Flodin Uppsala UniversityTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Takao Abe - The Jesuit Mission To New France - A New Interpretation in The Light of The Earlier Jesuit Experience in Japan (Studies in The History ofDocument243 pagesTakao Abe - The Jesuit Mission To New France - A New Interpretation in The Light of The Earlier Jesuit Experience in Japan (Studies in The History ofTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Tony Cliff's Family TreeDocument1 pageTony Cliff's Family TreeTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Theories and Methods of African Conceptual History: Rhiannon Stephens and Axel FleischDocument20 pagesTheories and Methods of African Conceptual History: Rhiannon Stephens and Axel FleischTheodor Ludwig WNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 5Document14 pagesWorksheet 5HiraiNo ratings yet

- Political Ideologies: What I Need To KnowDocument16 pagesPolitical Ideologies: What I Need To KnowVictoria Quebral CarumbaNo ratings yet

- Russian Revolution and Impact On Indian Freedom Struggle PDFDocument1 pageRussian Revolution and Impact On Indian Freedom Struggle PDFjashish911No ratings yet

- Marxist Criticism PresentationDocument43 pagesMarxist Criticism PresentationSheila Mae PaltepNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Trotskyism: Its Anti-Revolutionary NatureDocument214 pagesContemporary Trotskyism: Its Anti-Revolutionary NatureRodrigo Pk100% (1)

- Higher SuperstitionDocument47 pagesHigher SuperstitionsujupsNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Indian FeminismDocument11 pagesContemporary Indian FeminismArchana RajarajanNo ratings yet

- Leninism Under Lenin by Marcel LiebmanDocument479 pagesLeninism Under Lenin by Marcel LiebmanSergioNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Political IdeologiesDocument60 pagesLesson 2 - Political IdeologiesRuschelle Lao100% (1)

- Taguieff 1995Document35 pagesTaguieff 1995Tatiana S. Leal100% (1)

- The Recovery of Western MarxismDocument3 pagesThe Recovery of Western MarxismBen RosenzweigNo ratings yet

- Internal Assignment Batch BDocument3 pagesInternal Assignment Batch BAadhitya NarayananNo ratings yet

- Assignment # 1 Submitted By: F2019266364: Totalitarianism, Form of Government That Theoretically Permits NoDocument3 pagesAssignment # 1 Submitted By: F2019266364: Totalitarianism, Form of Government That Theoretically Permits NoRizwan KhadimNo ratings yet

- Communism The Vanishing Specter PDFDocument2 pagesCommunism The Vanishing Specter PDFDavidNo ratings yet

- Stalins Rise To PowerDocument2 pagesStalins Rise To PowerBecnash100% (1)

- Anarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism in South America - S. Fanny SimonDocument22 pagesAnarchism and Anarcho-Syndicalism in South America - S. Fanny SimonTravihzNo ratings yet

- Feudalism PDFDocument2 pagesFeudalism PDFKomal MeenaNo ratings yet

- Socialism 102 RevisionDocument2 pagesSocialism 102 RevisionCammeron Anthony VaughnNo ratings yet

- (Historical Materialism Book Series) Jacob A. Zumoff - The Communist International and US Communism, 1919-1929 (2015, Brill)Document455 pages(Historical Materialism Book Series) Jacob A. Zumoff - The Communist International and US Communism, 1919-1929 (2015, Brill)abelNo ratings yet

- M.N. RoyDocument5 pagesM.N. RoyAyush ShrimalNo ratings yet

- Russian RevolutionDocument12 pagesRussian Revolution41-Pragya Yadav-9ENo ratings yet

- Animal Farm Introduction and Allegory ChartDocument4 pagesAnimal Farm Introduction and Allegory ChartmohamedNo ratings yet

- Historyvslenin ScriptDocument2 pagesHistoryvslenin Scriptapi-271959377No ratings yet

- Animal Farm Vs Russian Revolution ParallelsDocument15 pagesAnimal Farm Vs Russian Revolution ParallelsAnas HudsonNo ratings yet

- Capitalism and Communism in Hunger GamesDocument3 pagesCapitalism and Communism in Hunger GamesBen100% (1)

- Lipset - The Changing Class StructureDocument34 pagesLipset - The Changing Class Structurepopolovsky100% (1)

- The Fetish of The Margins: Religious Absolutism, Anti-Racism and Postcolonial Silence by Chetan BhattDocument27 pagesThe Fetish of The Margins: Religious Absolutism, Anti-Racism and Postcolonial Silence by Chetan Bhatt5705robinNo ratings yet

- AJITH - Against AvakianismDocument256 pagesAJITH - Against AvakianismPaulo Henrique FloresNo ratings yet

- Katsiaficas) The Subversion of Politics Study GroupDocument230 pagesKatsiaficas) The Subversion of Politics Study GroupKathy SorrellNo ratings yet