Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Guilt As A Consequence of Migration

Guilt As A Consequence of Migration

Uploaded by

Irina MorosanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Guilt As A Consequence of Migration

Guilt As A Consequence of Migration

Uploaded by

Irina MorosanCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Published online in Wiley Online Library

(wileyonlinelibrary.com) DOI: 10.1002/aps.321

Guilt as a Consequence of Migration

CATHERINE WARD AND IRENE STYLES

ABSTRACT

Migration, for some individuals, can be a highly emotional experience. Guilt expressed

by daughters, as a result of leaving parents and family following migration, necessitates

exploration but has been largely neglected in migrant research. This study involved

migrant women from the United Kingdom (UK) to Australia. A cross-sectional design

in a naturalistic setting was used which involved both quantitative (questionnaire) and

qualitative approaches. In total 154 participants completed a questionnaire; however it

is the responses of a subset of 40 women who were interviewed which are reported here.

Bowlby’s (1969) mother–infant attachment theory provided the theoretical framework for

this investigation. Bowlby outlined the reaction to loss of attachment in four stages: it is in

Stage 2 (yearning and pining) that feelings of guilt manifest. Miceli and Castelfranchi’s

(1998) three component model of guilt was used to explore the construct of guilt which

can be associated with one’s behavior, with responsibility for one’s actions, and with the

consequences of that action.

Findings indicated that feelings of guilt, for some of these migrant participants, were

intense and long lasting. Guilt resulted from, firstly, leaving parents in the homeland,

secondly, being the only daughter or the only child and leaving parents in the homeland,

and thirdly, making the attachment between grandparents and grandchildren vulnerable

as a consequence of migration. Results from the study shows that guilt is a powerful

emotion that impacts on the well-being of migrant women and, through them, on their

families. The results also indicate that guilt, on the part of both men and women deserves

more in-depth inquiry to detail the psychological impact on migrants. Copyright © 2012

John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Key words: migration, guilt, attachment theory

INTRODUCTION

Studies have shown that people migrate for a variety of reasons such as improve-

ment in life style, better weather, better work opportunities for themselves and

their children, or to escape, family, persecution and war (Madden & Young,

1993; Pollock, 1981; Richardson, 1974; Ward, 2000). Migration may satisfy

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Ward and Styles

these expectations of a new life however, for some individuals it may bring about

the realization of what they have left behind in the homeland, in particular par-

ents and family (Ward, 2000).

As children grow and gain their independence they move out of the

parental home, however, according to Teaford (1993) as children mature

beyond this initial stage of independence, they tend to move closer, physi-

cally, to their parents, or alternatively, parents will move closer to their

children. It is when a young, newly independent, adult family plans to

migrate that the relationship between parents and adult child can be signif-

icantly challenged. The intense organization required in the process of

migration, means the migrants’ thoughts are focused on their new, perhaps

exciting, life and the challenges of settlement in the new country. Accord-

ing to Ward (2000), in this planning process the consequences of migration

are often not considered so that the realization what they have left behind

in the homeland occurs to the migrants either only at the time of actually

leaving the homeland, or later when parental closeness is missed. Only

when living in a new and distance place does the adult child recognize that

the geographical distance does not permit physical, or in some cases, psycho-

logical closeness. These limitations, therefore, significantly challenge the

child–parent relationship and the inherent responsibilities therein. Distance

makes caring for aging parents an almost impossible task, resulting in the

migrant adult child believing they have failed in their duty (Lewis, 1993).

The adult child may reason that if they had remained in the homeland, they

would be available to care for their aging parents. The guilt they feel as a con-

sequence of failing to care for aging parents is thus linked directly to migration

(Akhtar, 1999).

A study by, Baldassar, Baldock and Lange (1999) proposed that staying in

touch with family members in the homeland can be costly, both financially

and emotionally. Turnbull (1996) reported that for some British migrant women

the isolation and lack of family closeness was so unbearable that they returned to

their homeland. Important to the present study is the plight of those women

who remained in Australia. Certainly, geographical distance can make it impos-

sible to provide physical comfort and support. Baldock (1999) however argued

that it should not be assumed that care-giving is dependent on close proximity.

She has proposed that as parents age the adult child visits the homeland more

frequently and in some cases parents are encouraged to migrate and live with

their adult children. But these options may not be possible for many individuals

where financial constraints and family ties in the adopted country prohibit

frequent or long visits. Furthermore, parents may not wish to leave their home-

land to live in a strange place late in life. Despite the introduction of faster and

cheaper air flights Australia is still considered a remote place for people living on

the other side of the world.

“Homesickness” is one reaction to the perceived loss of parents and family

which is experienced as a grief process (Arredondo-Dowd, 1981; Baier &

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Guilt as a consequence of migration

Welch, 1992; Ward, 2000). In line with this perspective, the seminal work by

Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1979), which examined mother–infant attachment and

the subsequent development of the four stages of grieving served as the theoret-

ical framework for the study on the experiences of women migrants from which

this paper derived. The first stage of grieving numbing, can last for a few hours to

a few weeks. Yearning and pining is the next stage when the reality of what has

been lost begins to consciously register. The stage of disorganization and despair

follows, during which the person, believing that nothing can be salvaged of their

life, falls into a state of depression or apathy. Finally, the stage of re-organization

and resolution allows hope for a new beginning and a rebuilding of a new self.

Each of the four stages has specific characteristics related to grieving, however

for this paper, Stage 2 of pining and yearning is the most significant as it is

within this stage that guilt and self-reproach can feature.

Guilt, according to Izard (1991) and Lazarus (1991) is a basic human

emotion which can, in some individuals, invoke self-reproach. People expe-

rience guilt in relation to deeds which they regard as forbidden, with the

intensity of guilt differing between individuals according to race and culture

(Elvin-Nowak, 1999), as well as variations in individuals’ personalities.

Guilt in response to actions, inaction, or situations for which a person feels

personally responsible (Izard, 1991) is, in essence, a belief that the person

has failed themselves or others (Lewis, 1993). The feelings generated

by guilt can be unpleasant and painful for some individuals (Miceli &

Castelfranchi, 1998).

Grinberg and Grinberg (1989) proposed that guilt can be differentiated into

depressive and persecutory guilt. Whether these two types of guilt are evident in

the specific situations migrant women find themselves in is an empirical ques-

tion which is considered in this paper. Miceli and Castelfranchi (1998) offer a

perspective on guilt which may be more pertinent to a migrant situation: these

authors propose three components of this emotion. The first component is the

negative evaluation of one’s behavior (performed action) as injurious or bad.

Even if the transgressive action is unintentional the person feels bad about car-

rying it out. The second component relates to the assumption of responsibility

for their action, that is when the person may reason that they caused it (directly

or indirectly), they had the goal of causing it, or had the power to avoid it.

Similarly, Elvin-Nowak (1999) has proposed that responsibility “seems to be a

prerequisite for the appearance of guilt” (p. 74). The third component, lowering

of one’s moral self-esteem as a consequence of a particular action against

another, results in a negative evaluation of self as the perpetrator. It is this third

component that leads to the uncomfortable or even painful feelings experienced

by the guilt-laden person.

According to Akhtar (1999), in relation to migration guilt can manifest

on a conscious level when the person now enjoys a better standard of living

than family members and friends in their homeland. In this paper, we argue

that the complexity of feelings of guilt and their causes is compounded by

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Ward and Styles

geographical distance which can result in loss of attachment or physical close-

ness to parents, and also to grandparents, which may further amplify feelings

of guilt. Thus, for the purpose of this paper the statements of women migrants

to identify possible feelings of guilt and then evaluate whether such feelings

can be explained using Miceli and Castelfranchi’s three components.

In particular, we were interested in whether there was evidence of guilt

associated with loss of attachment with parents remaining in the homeland or

with denying parents a close relationship with grandchildren. We also wished

to determine whether women experience feelings of guilt until they believe their

parents have forgiven them for migrating (a perceived moral transgression).

Lastly, we wanted to examine whether these women, if suffering from feelings

of guilt, were able to forgive themselves or whether feelings of guilt endured over

long periods of time.

METHOD

This paper focuses on part of a larger study which investigated the impact of

migration on 154 British women from the United Kingdom (UK) who had relo-

cated to Australia at some time during the last 40 to 50 years. The study empha-

sized the lack of research on British migrants in general. Reactions included the

possibility of a grief reaction to perceived loss of homeland (homesickness), and

the perception of multiple loss (that is, loss of family, community, and cultural

aspects of the homeland) (Ward, 2000; Ward & Styles, 2003, 2007). However,

here we emphasize only those responses from participants deemed pertinent to

guilt. We note that the study did not set out to study guilt per se: these were

responses which became evident when analyzing statements for other purposes

but which seemed very important in understanding migrant women’s experiences.

The design incorporated a naturalistic, cross-sectional study in which both qual-

itative (semi-structured interview) and quantitative (questionnaire) approaches

were used to elicit the participant women’s perception of, and feelings about the

impact of migration. The results of the qualitative data from the responses of

a subset of 40 women who responded to both the questionnaire and the inter-

view are presented in this paper. The interview questions were developed fol-

lowing a comprehensive review of the literature related to migration, none of

which mentioned guilt. Questions included reasons for migration, attachment

to parent(s), feelings of homesickness, possible grief reactions, strategies to aid

settlement in the new country, and, of particular significance to this paper,

what, if anything, the women missed or felt they had lost as a result of migra-

tion (see Appendix for interview questions).

Participants

If a woman met the following two selection criteria she was invited to partici-

pate in the study; firstly, that she was born and grew up in the UK, and secondly,

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Guilt as a consequence of migration

that she had children (she may have had her first child in Australia, brought

children with her, or added to the family following migration). Participants were

recruited by distribution of a flyer outlining the study to local libraries, shopping

centers and two universities. A small feature describing the study and inviting

women to participate was placed in three community newspapers. If a volunteer

met the criteria, a questionnaire was sent to her with a reply-paid envelope. If a

volunteer did not meet the criteria, an explanation was given to her and she was

thanked for expressing an interest.

Of the 209 questionnaires distributed, 170 were completed and returned,

making a return rate of 81 percent. Of the returned questionnaires, 16 were

excluded either because they were incomplete or because the woman was very

young when she migrated. Thus, in total, 154 questionnaires were accepted

for the study – a satisfactory return rate of 73.6 percent. Of the 154 participants,

93 (60.3 percent) agreed to be interviewed. Respondents were allocated to one

of seven sub-groups according to the length of time (Residency) the participant

had resided in Australia. In order to provide a balanced perspective (negative

and positive) on the experience of migration, five people from each of the seven

sub-groups were selected on the basis of reporting (in the questionnaire) having

settled, or not, in the new country. Individuals forming this subset of 40 women

were interviewed about their experiences and reactions.

Once contacted, a mutually agreeable time, date, and venue for the interview

were arranged with each selected interviewee. It was emphasized that participa-

tion in the study was voluntary and that confidentiality would be maintained.

The researcher conducted all the interviews bearing in mind that for some

people, recounting their migration experiences might cause distress. Interviews

took approximately 45 minutes to one hour to complete: all were audiotaped

and later transcribed verbatim. Data gathered from the interviews and open

items in the questionnaire were coded by themes and managed using the

Non-numerical Unstructured Data Indexing Searching and Theory Building

(NUD●IST 4) software package (Richards & Richards, 1994).

FINDINGS

For the purpose of his paper findings from the 40 women interviewed are

presented.

Participants had resided in Australia, from less than one year up to

34 years. Ages ranged from 26 to 68 years [mean (M) = 46.9, standard devia-

tion (SD) = 12.12]. There was a cluster of participants between the ages of

35 to 54 years (n = 89, 57.3 percent).

Motivation or reasons to migrate

Table 1 shows the responses of the participants to a question about their rea-

sons for migrating categorized into two major types – lifestyle and social – and

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Ward and Styles

several more minor ones. A high proportion of participants selected lifestyle

factors as the primary reasons to migrate, especially better life opportunities

(24 percent, n = 24); a better climate (50 percent, n = 20); an improved family

lifestyle (47.5 percent, n = 19) and clean environment (27.5 percent, n = 11).

The major social factor selected by participants was job opportunities (22.5

percent, n = 9), followed by family reunion (17.5 percent, n = 7). Selection of

“other” accounted for 45 percent (n = 18) of various motivations. Overall

the results show that the motivation to migrate was driven by perceptions

of inadequate lifestyle within the UK, and the improvement in lifestyle that

Australia seemed to offer.

Attachment and attachment figure(s)

Interview data based on questions that related to the participants’ relationships

with their mothers, fathers as attachment figures, up to and just before migrating,

were examined to determine the basis and strength of that relationship. Data

were categorized to determine who the primary attachment figure was at the

time of migration, and how the participant responded to that figure; that is

did they have a close relationship. .

Results indicated that nearly all the participants regarded either their mother

or father as the major attachment figure. Of the 26 women who were deemed to

view their mother as their major attachment figure, only nine (23 percent) con-

sidered they had a close relationship with their mothers. In contrast, 17 (43 per-

cent) participants considered that they did not have a close relationship with

their mother. These women talked about a lack of “closeness” which caused a

difficulty in communicating with their mother. Of the remaining participants,

four (10 percent) identified their father as the major attachment figure with

whom they had a close relationship; whilst three (seven percent) participants

stated they were not close to their father.

Table 1: Responses from total number of participants related to motivation to migrate

Motivation to migrate Number and percentage of participantsa

Lifestyle

Better life opportunities 24 (60)

Climate 20 (50)

Improved family lifestyle 19 (47.5)

Clean environment 11 (27.5)

Social

Job opportunities 9 (22.5)

Family reunion 7 (17.5)

Other (45)

a

Percent shown in parentheses.

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Guilt as a consequence of migration

Due to the nature of the study there was reliance on retrospective data, there-

fore, it is possible that those participants who had resided in Australia for many

years were unable to recall specific and reliable details of how they felt about

leaving the homeland and parents/family. The newer migrants may have been

able to recount their experiences in clearer terms. However, what mattered were

participants’ judgments of the intensity of their feelings, and the engagement of

the participants with the questions indicated that they still felt strongly about

their experiences.

Guilt was a significant consequence of migration mentioned by many of the

participants in the interview group in relation to loss of attachment to the

homeland. In total, 29 incidences (mean value of 0.73) mentioned by 19

(47.5 percent) participants related to feelings of guilt. Thirteen incidences

(mean value of 0.33) related to feeling guilty at leaving their parents behind

in the homeland, 12 incidences (mean value of 0.3) related to taking grandchil-

dren away from their parents and family, and three incidences (mean value of

0.08) related to the participant being an only daughter and leaving her parents.

Feelings of guilt for some of the women did not emerge until later in life when

they realized what their decision to migrate had done to their mother/parents.

An event which triggered feelings of guilt for some of these women was when

they themselves became grandmothers and realized the wrench their parents

must have felt when parted from their grandchildren. The women in the inter-

view group mentioned that they maintained contact with parents and family in

the homeland by telephone (n = 20, 50 percent), letter (n = 14, 35 percent) and

email (n = 2, five percent).

An attempt was made to identify the two types of guilt mentioned by Ginsberg,

namely persecutory or depressive; however, there was no evidence of persecutory

guilt. Instead of pursuing this as an explanatory framework we used Miceli and

Castelfranchi’s (1998) conceptual framework. Findings from the interview group

are presented in relation to the three components of guilt proposed in that frame-

work: firstly, the negative evaluation of one’s behavior as injurious or bad; secondly,

the assumption of responsibility for one’s behavior; and thirdly, lowering of one’s

moral self-esteem as a consequence.

Negative evaluation of one’s behaviour as injurious or bad

A sense of guilt results from a person’s negative evaluation of a specific action

(Miceli & Castelfranchi, 1998). The following quotes encapsulate the

women’s negative evaluation of their actions in leaving parents and family

in the homeland – actions that were injurious to others or to the self, and

that resulted in a sense of guilt. The first two quotes demonstrate general feelings

of guilt.

Oh guilty, yes definitely guilty those first few years. (7836, resident 14 years)

Felt guilty, very guilty, extremely guilty. (5658, resident 21 years)

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Ward and Styles

Some women commented on women feeling guilty no matter what action

they took:

I felt guilty . . . lot to be guilty about. Yes it hurt. I think it [guilt] must be a women thing.

I don’t think men even think about it. I think women feel guilty about everything that

they can feel guilty about. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. (1604, resident

16 years)

Another woman describes how guilty she felt because she was certain her

family’s leaving resulted in the premature death of her father-in-law:

Oh terrible, absolutely. I honestly think it was probably one of the things that hastened my

father-in-law to death. It took him 18 months to accept . . . (he would) never see them

again. (7505, resident 30 years)

Here, one woman, even after many years, still agonizes over whether her

actions (migrating) were acceptable:

Should we have done it? Should we have come? Should we have taken the children away

from that extended family, grandparents and such? (5658, resident 21 years)

Guilty feelings are also felt in relation to a husband’s family:

We had a big round of goodbyes to do of course and there was an element of guilt as well

because we were leaving Ks parents behind and we could see how that was upsetting them

tremendously, especially his mum. (1126, resident 20 years)

Assume responsibility for action/behavior

Miceli and Castelfranchi’s second component of guilt is that the person has to

feel personally responsible for the “bad” action.

I feel very guilty taking my children away from their relatives. Very guilty. (6790, resident

29 years)

. . . she [mother] gave my elder daughter a big hug and a kiss then she took notice of the

little one, being very aware that she had known the older one first. It was later that I re-

alized what it must have been like and I did go through a lot of guilt very bad, very bad

guilt when it all really hit me that “oh my goodness”. I had always been aware of my chil-

dren’s loss of not having the extended family, but I hadn’t really looked upon it the other

way until everything just caved in around me. (1516, resident 32 years)

Some women noted that geographical distance prohibited provision of

support to parents for which they felt responsible:

I was abandoning them, that was an emotional issue. They had given me everything and I

was just going to take it and fly. (7131, resident 22 years)

Sometimes I felt guilty for leaving. I’m the only daughter of my parents they have four

sons, all of whom live near my parents and visit regularly. (1604, resident 16 years)

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Guilt as a consequence of migration

The responsibility for denying grandparents physical access to grand children

is evident here:

I felt a bit guilty because I was taking away their grandchildren, but at the same time I had

to think of their life as a family as well as my own. (1816, resident 15 years)

I felt guilty and I said how can I leave them [parents] how can I take their only grand-

daughter away from them. (2502, resident 1.6 years)

There is also responsibility for depriving children of their grandparents:

. . . she was only a baby when we brought her out here she was only five but when I tried to

discipline her she cried for nanna – so that was hard and its always been hard on the kids

cos they’ve not had you know . . . [participant cries]. (7937, resident 18 years)

They [children] don’t know what it’s like to have a granddad and grandma permanent they

don’t know about that [participant crying]. (1033, resident seven years)

Lowering of one’s moral self-esteem as a consequence

Having identified that they are the perpetrator of the action which injured

others (and the self), .the person experiences feelings in regard to the self, such

as remorse, sadness, shame, and selfishness. They may think they have made

loved ones feel abandoned, unloved, or betrayed.

I felt very sad actually that she was so hurt and disappointed. I felt very guilty I suppose.

(1021, resident 11.5 years)

. . . felt like we were betraying them in a way, made us feel guilty, selfish almost. (4115, res-

ident, 2.5 months)

Felt like we were betraying them in a way – made us feel guilty. (3425. resident 10 years)

I felt my parent might think that I didn’t love them that’s why I left. I am finally con-

vinced that I didn’t do it because I never loved them. So I felt a bit of guilt for years. I

had that for a long time. (1058, resident 17 years)

I was abandoning them. They were only 50 [years old], I mean it wasn’t a health issue. I

was abandoning them, that was an emotional issue. They had given me everything and

I was just going to take it and fly. (7131, resident 22 years)

Feelings such as anger and resentment focused towards others, such as part-

ners who may have instigated the action (migration), may also be apparent –

and can also undermine self-esteem.

I resent the fact that I can’t go home. I resent the fact that my kids don’t know my

parents and I suppose in a way I probably feel a bit guilty about that as well. (3425,

resident 10 years)

I’d have great feelings of anger, sadness and not to mention guilt when I think of what I

put them through during a period that was traumatic enough. (2502, resident 1.6 years)

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Ward and Styles

It was evident from some statements that women were trying to cope with

the guilt in different ways, for example, by ignoring guilty feelings or by viewing

themselves as deserving to feel bad or to have things go wrong as a punishment

for their actions:

I suppressed my feelings as I am an only child and did not want to leave my parents be-

hind. (2502, resident 1.6 years)

Leaving my mum especially was the worst and after 24 years and her death the feelings are

there, perhaps I don’t want them to go away. (4238, resident 24 years)

I felt a lot of guilt from taking my son away from his family in England. I know my son is

too young to miss them but I know how much our families are missing him. I also worry

about any health problems the family may have in England. I feel if anything goes wrong

it is my punishment for leaving them. (4155, resident 2.5 years)

Analysis of data in relation to the age of the participants, years of residency,

and motivation to migrate, did not reveal differences in the type or intensity of

guilt experienced by these women according to these factors. There were also no

discernable differences in regard to major attachment figures or the quality of

that attachment, however, because the larger study did not seek to specifically

assess type or strength of attachment, further studies should undertake a more

detailed investigation of the impact of these elements on guilt feelings.

DISCUSSION

Findings from this study show that guilt is a pervading, punishing and a long

lasting emotion. The expression of guilt by so many of the respondents was un-

expected as was the extent of the emotion which seemed complex, and deeply

rooted. Lin and Rogerson (1995) observe that when daughters migrate they con-

tinue to nurture emotional ties to their family in the homeland, especially close

family. There is a societal expectation that daughters in adulthood will continue

to have close emotional ties to the family and are expected to help more than

sons (Lin & Rogerson, 1995). Thus if, as a result of migration, a woman believes

she has not fulfilled her obligation to care for her parents as they age, guilt will

manifest. The initial act of migration, leaving parents behind and having

deprived their children of knowing their grandparents, results in long-term guilt

feelings which weigh heavy on the mind. Baldock (1999) has also concluded

that as both daughter and parents age the emotional turmoil that occurs can

be, especially for the daughter, most distressing. The geographical distance

between her homeland and the adopted country, and subsequent allegiance to

her family in Australia, aggravates the situation.

According to Bowlby (1979) there is a “supposition that guilt is intrinsic to

mourning” (p. 8): it is proposed here that for the migrant women in this study

this mourning with its attendant feelings of guilt, relates directly to the

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Guilt as a consequence of migration

consequences of migration. For the women in the present study, guilt was related

to a number of factors, firstly, leaving their parents in the homeland; secondly,

taking their children away from grandparents and family; thirdly, depriving their

children of their extended family; and, fourthly, not being close by parents as

they age. . Migrant women may feel they have “transgressed” against their

parents, their wider family and even their own children by willfully leaving

them.

Analysis of responses did not reveal evidence of depressive and persecutory guilt

(Grinberg & Grinberg, 1989), however the three components of guilt proposed by

Miceli and Castelfranchi (1998) was a valuable tool in explaining the reason for

guilt experienced by the women. These authors also provide strategies to overcome

this pervading emotion and propose the person should make amends for their per-

ceived transgression, since not doing so only “sharpens the original sense of guilt”

(p. 307). According to Miceli and Castelfranchi (1998) making amends is a means

to reconcile the transgression, however for these women the transgression is multi-

faceted and not only involves them but their children, parents and family. For

many of them, no reparation such as reuniting the family was possible. No woman

in this study mentioned reparation, thus feelings of guilt in some cases remained

after more than 20 years. Perhaps these women did not perceive that they deserved

forgiveness after the injury they had caused.

Morokvasic (1981) stresses that attention should be given to pertinent issues

which are exclusive to women that could otherwise remain unresearched and

unanalyzed, resulting in vital information remaining undiscovered. We

propose, however, that future research could investigate whether migrant men

experience the same level of guilt, and for the same reasons, as the participants

in this study. The findings from this study demonstrate that guilt expressed by

migrant women as a consequence of leaving the homeland, parents and family

deserves further research to determine what impact this pervading emotion

may have on a person’s ability to make amends as well as its impact on the

psychological well-being of the migrant.

APPENDIX: A SAMPLE OF THE INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

Decision

Was it a gradual decision over time (to migrate) or did something or someone

influence you?

Whose decision was it initially to go?

Leaving the homeland

Can you describe your feelings when you were preparing to leave your “home”?

How do you now feel about the decision to move?

Reaction to leaving

What was the reaction of your family to your move?

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Ward and Styles

What was the reaction to taking your children away?

What impact do you think your migration had on the family?

Relationship

Did you have a good relationship with your mother/father?

Impressions of Australia

What was your first impression of Australia?

What was your first impression of Australians?

Racism

Was there any incidence of racism toward you or your family?

Can you recall any culture shock when you first arrived?

Stressful times

When you first migrated can you recall any stressful times?

Did you feel lonely or trapped?

Belonging

Do you have a sense of belonging to Australia? If so, do think it was gradual or

did it occur at a specific time?

Homesick

Have you ever felt homesick? If so, how do you overcome the feelings?

Perception of self

Do you think the process of migration has changed you? In what way?

Old and new friends

Did you have a good circle of friends in the homeland?

How do your old friends differ from your new friends?

Childrearing

Can you tell me what it was like caring for a newborn?

When you had your baby who helped you before and after the birth?

Were you ever “blue” following the birth?

Child settlement

When you decided to come here do you think that the children understood

what was happening?

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Guilt as a consequence of migration

REFERENCES

Akhtar, S. (1999). Immigration and identity. Turmoil, torment and transformation. Lanham, MD:

Jason Aronson Inc.

Arrendondo-Dowd, P. M. (1981). Personal loss and grief as a result of immigration. The

Personnel and Guidance Journal, 59, 376–378.

Baier, M., & Welch, M. (1992). An analysis of the concept of homesickness. Archives of

Psychiatric Nursing, VI(1), 54–60.

Baldassar, L., Baldock, C. V., & Lange, C. (1999). Immigration and transnational care-giving:

Public policies and their impact on migrants’ ability to care from a distance. Proceedings of

the Annual Sociology Conference, December.

Baldock, C. V. (1999). The ache of frequent farewells. In M. Pool & S Feldman (Eds), Of a certain

age. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, vol. 1: Attachment. London: Hogarth Press.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss, vol. 2: Separation. New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1979). Affectional bonds: Their nature and origin. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Elvin-Nowak, J. (1999). The meaning of guilt: A phenomological description of employed

mothers experiencing guilt. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 40, 73–83.

Grinberg, L., & Grinberg, R. (1989). Psychoanalytic perspectives on migration and exile. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press.

Izard, C. E. (1991). The psychology of emotion. New York: Plenum Press.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, M. (1993). Self conscious emotions: Embarrassment, pride, shame and guilt. In M. Lewis &

J. Haviland (Eds), Handbook of emotions. New York: Guildford Press.

Lin, G., & Rogerson, P. A. (1995). Elderly parents and the geographic availability of their adult

children. Research on Aging, 17(3), 303–331.

Madden, R. & Young, S. (1993). Women and men immigrating to Australia: Their characteristics and

immigration decisions. Canberra: Bureau of immigration research.

Miceli, M., & Castelfranchi, C. (1998). How to silence one’s conscience: Cognitive defenses

against the feelings of guilt. Journal for the Theory of Self Behaviour, 28(3), 287–318.

Morokvasic, M. (1981). The invisible ones: A double role of women in the current European

migration. In Eitinger, L., & Schwartz, D. (Eds.), Strangers in the world (pp. 161–185). Bern:

Humber Hans Press.

Pollock, J. (1981). Settlement of British migrants in Australia (Unpublished report F 305.821 094).

Sydney: Australian British Society.

Richards, T. G., & Richards, L. (1994). Using computers in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin

& Y. S. Lincoln (Eds), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 445–462). London: Sage.

Richardson, A. (1974). British immigrants and Australia: A psycho-social inquiry. Canberra.

Teaford, M. H. (1993). Availability of adult children and residual mobility of older widows. Paper

presented at the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, New Orleans, LA.

Turnbull, P. (1996). Jogging memories. Voices, 6(3), 9–17.

Ward, C. (2000). Metamorphosis, migration and the residual link: Resources of British migrant

women to reinvent themselves. PhD Thesis, Murdoch University, Perth.

Ward, C., & Styles, I. (2003). Identity lost and found: Reinvention of the self following migration.

Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 5(3), 349–367.

Ward, C., & Styles, I. (2007). Evidence of the ecological self: English-speaking migrants’

residual link to their homeland. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 4(4),

319–332.

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

Ward and Styles

Catherine Ward, PhD,

Notre Dame University, Fremantle, 6160, Western Australia, Australia

Catherine.ward@nd.edu.au

Irene Styles, PhD,

Graduate School of Education and Pearson Psychometric Center, University of

Western Australia Crawley, 6009, Western Australia, Australia

irenestyles@uwa.edu.au

Int. J. Appl. Psychoanal. Studies (2012)

Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. DOI: 10.1002/aps

You might also like

- The Adjustment of Nondisabled Adolescent Siblings of Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorder in The HomeDocument18 pagesThe Adjustment of Nondisabled Adolescent Siblings of Individuals With Autism Spectrum Disorder in The HomeAutism Society Philippines100% (4)

- HomesicknessDocument25 pagesHomesicknessAnnKhoLugasan75% (4)

- A Psychoanalytic Review of Immigration: It S Unconscious Fantasies and Motivations - Claudia Melville, M.A.Document16 pagesA Psychoanalytic Review of Immigration: It S Unconscious Fantasies and Motivations - Claudia Melville, M.A.Claudia MelvilleNo ratings yet

- Hope in Homeless People: A Phenomenological Study: Mary PartisDocument12 pagesHope in Homeless People: A Phenomenological Study: Mary PartisAyesha Malik100% (1)

- Emotional Maturity, Self-Esteem and Attachment Styles: Preliminary Comparative Analysis Between Adolescents With and Without Delinquent StatusDocument16 pagesEmotional Maturity, Self-Esteem and Attachment Styles: Preliminary Comparative Analysis Between Adolescents With and Without Delinquent StatusIrina MorosanNo ratings yet

- Arc GeneralDocument7 pagesArc GeneralMistor Dupois WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Women Mental HelathDocument21 pagesWomen Mental Helathsanjana.mehtaNo ratings yet

- Karydi 2018 Childhood Bereavement The Role of The Surviving Parent and The Continuing BondsDocument12 pagesKarydi 2018 Childhood Bereavement The Role of The Surviving Parent and The Continuing Bondsgeorge.daher1No ratings yet

- Growing Up With GriefDocument20 pagesGrowing Up With GrieffernandamancilhapsiNo ratings yet

- Complicated Grief in Children-The Perspectives of Experienced ProfessionalsDocument13 pagesComplicated Grief in Children-The Perspectives of Experienced ProfessionalsGlenn ArmartyaNo ratings yet

- Mourning or Early Inadequate CareDocument17 pagesMourning or Early Inadequate CarefernandamancilhapsiNo ratings yet

- Copiii Lui DuplessisDocument19 pagesCopiii Lui DuplessisLoredana Pirghie AntonNo ratings yet

- Disenfranchised Grief 10.22Document20 pagesDisenfranchised Grief 10.22dofiajoijNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Imprisonment On Families and Children of PrisonersDocument21 pagesThe Effects of Imprisonment On Families and Children of PrisonersJu100% (1)

- Bowlby, The Strange Situation, and The Developmental NicheDocument7 pagesBowlby, The Strange Situation, and The Developmental NicheVoog100% (2)

- COUN 611 Counseling Grieving ChildrenDocument12 pagesCOUN 611 Counseling Grieving ChildrenPhillip F. MobleyNo ratings yet

- Psychological Well BeingDocument15 pagesPsychological Well Beingbluesandy1No ratings yet

- JournalofFamilyIssues 2009 Mitchell 1651 70Document21 pagesJournalofFamilyIssues 2009 Mitchell 1651 70makmurNo ratings yet

- "Lahat Po Tayo Ay May Katapusan": The Concepts of Death Among Filipino ChildrenDocument19 pages"Lahat Po Tayo Ay May Katapusan": The Concepts of Death Among Filipino ChildrenAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural Transition: International Teachers' Experience of 'Culture Shock'Document19 pagesCross-Cultural Transition: International Teachers' Experience of 'Culture Shock'Lourdes García CurielNo ratings yet

- Dissertation BereavementDocument5 pagesDissertation BereavementWriteMyStatisticsPaperUK100% (1)

- BSP3 3 Agony of A Winner A Phenomenological Study About The Struggles and Coping Mechanisms of The Eldest Sibling Being The Breadwinner of The FamilyDocument102 pagesBSP3 3 Agony of A Winner A Phenomenological Study About The Struggles and Coping Mechanisms of The Eldest Sibling Being The Breadwinner of The FamilyNathalie Aira GarvidaNo ratings yet

- 08 - Chapter 3Document17 pages08 - Chapter 3djamel eddineNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Psikologi SosialDocument23 pagesJurnal Psikologi SosialYasinta AuliaNo ratings yet

- Final ThesisDocument118 pagesFinal ThesisKyle DionisioNo ratings yet

- Loneliness CacioppoDocument35 pagesLoneliness CacioppoMindGrace100% (1)

- Childfree Women at MidlifeDocument10 pagesChildfree Women at Midlifedmollen0214100% (1)

- Duelo y Su Impacto en El Vinculo PrenatalDocument16 pagesDuelo y Su Impacto en El Vinculo PrenataljuanaNo ratings yet

- The Psychological Impact of Reproductive Difficulties On Women's LivesDocument20 pagesThe Psychological Impact of Reproductive Difficulties On Women's LivesAnaNo ratings yet

- Julia Badger and Peter Reddy 2009Document10 pagesJulia Badger and Peter Reddy 2009stephanieNo ratings yet

- A Story To Tell The Identity Development of Women Growing Up As Third Culture KidsDocument19 pagesA Story To Tell The Identity Development of Women Growing Up As Third Culture Kidshedgehog179No ratings yet

- Ocean of Tears: The Lived Experience of Bereaved Mothers by Intentional Self-HarmDocument16 pagesOcean of Tears: The Lived Experience of Bereaved Mothers by Intentional Self-HarmjonilynNo ratings yet

- Adolescents Chapt 11 and 12Document7 pagesAdolescents Chapt 11 and 12RUTH AUMANo ratings yet

- Death Studies Volume Issue 2016 (Doi 10.1080 - 07481187.2016.1203376) BatoolDocument11 pagesDeath Studies Volume Issue 2016 (Doi 10.1080 - 07481187.2016.1203376) Batooliqra.nazNo ratings yet

- End-of-Life Issues Term PaperDocument9 pagesEnd-of-Life Issues Term PaperSam OlewnikNo ratings yet

- GerontologyDocument13 pagesGerontologyAna MunteanNo ratings yet

- Childhood AmnesiaDocument15 pagesChildhood Amnesiatresxinxetes5406No ratings yet

- Stigmatising Feelings and Disclosure Apprehension Among Children With EpilepsyDocument5 pagesStigmatising Feelings and Disclosure Apprehension Among Children With Epilepsyanna regarNo ratings yet

- 10livedexperiencesof EarlyPregnancyDocument13 pages10livedexperiencesof EarlyPregnancyFRANCISCO MANICDAONo ratings yet

- De LyserDocument9 pagesDe LyserAna MoraisNo ratings yet

- Becoming A Father Psychosocial Challenges For Greek Men: Thalia DragonaDocument18 pagesBecoming A Father Psychosocial Challenges For Greek Men: Thalia DragonammtruffautNo ratings yet

- Attachment Theory in Adolescence and AdulthoodDocument6 pagesAttachment Theory in Adolescence and AdulthoodsimuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - Sample 2Document15 pagesChapter 2 - Sample 2Je CoNo ratings yet

- A Development Concept of Adolescence - The Case of Adolescents in The PH (Ogena, N.D.)Document19 pagesA Development Concept of Adolescence - The Case of Adolescents in The PH (Ogena, N.D.)Marianne SasingNo ratings yet

- The Use of Physical Objects in Mourning by MidlifeDocument15 pagesThe Use of Physical Objects in Mourning by MidlifeVivianna TanasiNo ratings yet

- Teenage Mothers, Stigma and Their 'Presentations of Self'Document21 pagesTeenage Mothers, Stigma and Their 'Presentations of Self'Roselyn PascobelloNo ratings yet

- The Life Cycle and DisabilityDocument16 pagesThe Life Cycle and DisabilityJeanYanNo ratings yet

- 18918-67015-1-PB PDFDocument11 pages18918-67015-1-PB PDFMatheus MajerNo ratings yet

- χριστακηςDocument15 pagesχριστακηςElizabeth HensleyNo ratings yet

- Ideal Ages For Family Among Immigrants in Europe (2012)Document13 pagesIdeal Ages For Family Among Immigrants in Europe (2012)Aulia Kusuma Wardani 'elDhe'No ratings yet

- #1 PDFDocument15 pages#1 PDFAlamay HansNo ratings yet

- Loneliness in Older Women A Review of The LiteratureDocument20 pagesLoneliness in Older Women A Review of The LiteratureEdłardo Fłentes GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Continuing Bonds After Suicide Bereavemet in ChildhoodDocument27 pagesContinuing Bonds After Suicide Bereavemet in Childhoodtrevor lawrenceNo ratings yet

- Individuation, Ego Development and The Quality of Conflict Negotiation in The Family of Adolescent GirlsDocument7 pagesIndividuation, Ego Development and The Quality of Conflict Negotiation in The Family of Adolescent GirlsMaria Elena Botero TobonNo ratings yet

- He As OnDocument18 pagesHe As OniolandaszaboNo ratings yet

- Death and Dying A Systematic Review Into Approaches Used To Support Bereaved ChildrenDocument28 pagesDeath and Dying A Systematic Review Into Approaches Used To Support Bereaved ChildrenIreneNo ratings yet

- Adult Adoptees Exploration of Self-Identity Through The Use of ArDocument33 pagesAdult Adoptees Exploration of Self-Identity Through The Use of Arnicole dufournel salasNo ratings yet

- +++barcons Et Al. 2011 Menores Adoptados Internacionales Problemas de ConductaDocument11 pages+++barcons Et Al. 2011 Menores Adoptados Internacionales Problemas de ConductaGonzalo Morán MoránNo ratings yet

- A Development Concept of Adolescence: The Case of Adolescents in The PhilippinesDocument19 pagesA Development Concept of Adolescence: The Case of Adolescents in The PhilippinesHannah dela MercedNo ratings yet

- Pinakafinal ThesisDocument132 pagesPinakafinal ThesisKim Cambaya HosenillaNo ratings yet

- Fingerman Applications of Family Systems Theory To AdulthoodDocument25 pagesFingerman Applications of Family Systems Theory To AdulthoodValeska NoheadNo ratings yet

- An exploratory study of the effect of age and gender on innocenceFrom EverandAn exploratory study of the effect of age and gender on innocenceNo ratings yet

- Friedman SummaryDocument12 pagesFriedman SummaryIrina MorosanNo ratings yet

- 11 Emotional Mchapter 4Document51 pages11 Emotional Mchapter 4Irina MorosanNo ratings yet

- GFMD Brussels07 Contribution Unicef Moldova enDocument97 pagesGFMD Brussels07 Contribution Unicef Moldova enIrina MorosanNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Parental Deprivation On The Development of Children PDFDocument112 pagesThe Impact of Parental Deprivation On The Development of Children PDFIrina MorosanNo ratings yet

- Development of The Cyberbullying Experiences SurveyDocument12 pagesDevelopment of The Cyberbullying Experiences SurveyIrina Morosan100% (1)

- Construing Benefits From AdversityDocument5 pagesConstruing Benefits From AdversityIrina MorosanNo ratings yet

- Cyber VictimizationDocument54 pagesCyber VictimizationIrina MorosanNo ratings yet

- Catat Materi Ini.: Social FunctionDocument3 pagesCatat Materi Ini.: Social Functionbudi hartantoNo ratings yet

- CSCI 3210: Theory of Programming Languages 3 Credit Hours: Instructor InformationDocument5 pagesCSCI 3210: Theory of Programming Languages 3 Credit Hours: Instructor InformationGES ISLAMIA PATTOKINo ratings yet

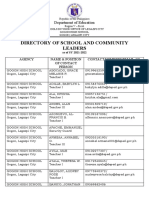

- Directory of School and Community LeadersDocument6 pagesDirectory of School and Community LeadersWinston CelestialNo ratings yet

- Cambridge English: First Practice Test ADocument3 pagesCambridge English: First Practice Test AJuan NarvaezNo ratings yet

- Presentation About Web DevelopmentDocument2 pagesPresentation About Web DevelopmentJamila NoorNo ratings yet

- Entertainment: Listening WS: Student's DetailsDocument3 pagesEntertainment: Listening WS: Student's DetailsDino CatNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Language Summary: People You Know Everyday ThingsDocument2 pagesUnit 1 Language Summary: People You Know Everyday ThingsRafael Conceição FalcãoNo ratings yet

- Self Directed LearningDocument52 pagesSelf Directed LearningGlenn M. Apuhin0% (2)

- 8623-1 Spring 2019 PDFDocument14 pages8623-1 Spring 2019 PDFFarooq ShahNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit Question BankDocument7 pagesSanskrit Question BankDeepak BisenNo ratings yet

- Cassandra Desrosiers Resume 11 27 15Document1 pageCassandra Desrosiers Resume 11 27 15api-270111279No ratings yet

- The Power of Positive Thinking E-BookDocument39 pagesThe Power of Positive Thinking E-Bookhitesha1448452No ratings yet

- Syllabus Purposive CommunicationDocument6 pagesSyllabus Purposive CommunicationEdlyn SarmientoNo ratings yet

- PAkistan Garden 3Document10 pagesPAkistan Garden 3Fahad KhanNo ratings yet

- Syllabus ENG 102 SP 2024 Jan. 14 2024Document17 pagesSyllabus ENG 102 SP 2024 Jan. 14 2024csrbz5zbs7No ratings yet

- MC No. 2021-003 - Establishment of The Professional Tour Guides Qualification Examination (PTGQUALEX)Document8 pagesMC No. 2021-003 - Establishment of The Professional Tour Guides Qualification Examination (PTGQUALEX)Dhon CaldaNo ratings yet

- Whole Brain Thinking and LearningDocument46 pagesWhole Brain Thinking and LearningScarlet BlackNo ratings yet

- 21ST LitDocument2 pages21ST LitClara ManriqueNo ratings yet

- Case Study PreliminariesDocument6 pagesCase Study PreliminariesEugene John DulayNo ratings yet

- John Robinson ResumeDocument2 pagesJohn Robinson Resumeapi-508032756No ratings yet

- Ipcr Part 3 4 NTP 2019Document3 pagesIpcr Part 3 4 NTP 2019Lavandera Lpt Vargas JoannaNo ratings yet

- DLL - MATH - 3 - Q4 - W8 - Solves Routine and Non-Routine Problems Using Data Prsented in A Single-Bhar Graph - @edumaymay@lauramosDocument8 pagesDLL - MATH - 3 - Q4 - W8 - Solves Routine and Non-Routine Problems Using Data Prsented in A Single-Bhar Graph - @edumaymay@lauramosjimNo ratings yet

- E3-LUNA-Art As A ConceptDocument2 pagesE3-LUNA-Art As A ConceptIrish Mae LunaNo ratings yet

- KTEA 3 Parent Report - 54433345 - 1712666972404Document9 pagesKTEA 3 Parent Report - 54433345 - 1712666972404p0074790No ratings yet

- Principles of High Quality AssessmentDocument46 pagesPrinciples of High Quality AssessmentBimbim WazzapNo ratings yet

- March17.2013solon To DOLE: Let Students Know Summer Jobs Program Exempted From Hiring BanDocument2 pagesMarch17.2013solon To DOLE: Let Students Know Summer Jobs Program Exempted From Hiring Banpribhor2No ratings yet

- Filipino, The Language That Is Not OneDocument7 pagesFilipino, The Language That Is Not OneRyan Christian BalanquitNo ratings yet

- Speakout 2e Elementary ContentsDocument2 pagesSpeakout 2e Elementary ContentsPhương HiếuNo ratings yet

- Directed Writing GuideDocument5 pagesDirected Writing GuideMasturaBtKamarudin100% (1)