Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

Uploaded by

Elina Pérez de KleinCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 3 - Differentiating Sex and GenderDocument7 pages3 - Differentiating Sex and GenderJapet J100% (1)

- Peaceful Coexistance - Autism, Asperger's, HyperlexiaDocument4 pagesPeaceful Coexistance - Autism, Asperger's, HyperlexiaDefault User100% (1)

- The Role of Self-Blaming Moral Emotions in Major Depression and Their Impact On Social-Economical Decision MakingDocument17 pagesThe Role of Self-Blaming Moral Emotions in Major Depression and Their Impact On Social-Economical Decision MakingJuan Camilo Osorio AlcaldeNo ratings yet

- Structure of Psychopathology in Adolescents and Its Association With High Risk Personality TraitsDocument16 pagesStructure of Psychopathology in Adolescents and Its Association With High Risk Personality TraitsjulianposadamNo ratings yet

- HHS Public AccessDocument19 pagesHHS Public AccessVirginia PerezNo ratings yet

- Musa & Lepine (2000)Document8 pagesMusa & Lepine (2000)Yijie HeNo ratings yet

- 10 1017@S0033291720002172Document22 pages10 1017@S0033291720002172Thati PonceNo ratings yet

- Social Cognition in Anorexia Nervosa: Specific Difficulties in Decoding Emotional But Not Nonemotional Mental StatesDocument8 pagesSocial Cognition in Anorexia Nervosa: Specific Difficulties in Decoding Emotional But Not Nonemotional Mental StatesRezafitraNo ratings yet

- Development Depression Children PDFDocument21 pagesDevelopment Depression Children PDFAndra VlaicuNo ratings yet

- The Neglected Relationship Between Social Interaction Anxiety and Hedonic Deficits: Differentiation From Depressive SymptomsDocument12 pagesThe Neglected Relationship Between Social Interaction Anxiety and Hedonic Deficits: Differentiation From Depressive SymptomsDan StanescuNo ratings yet

- Systems of Adversity, Psychological Distress, and CriminalityDocument23 pagesSystems of Adversity, Psychological Distress, and CriminalityjulianposadamNo ratings yet

- Judgemental AttitudeDocument7 pagesJudgemental AttitudeCaroline SanjeevNo ratings yet

- Contagious Depression - Automatic Mimicry and The Mirror Neuron System - A ReviewDocument12 pagesContagious Depression - Automatic Mimicry and The Mirror Neuron System - A ReviewJuliano Flávio Rubatino RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Harm Aversion As A Necessary Foundation For Morality: A Developmental Neuroscience PerspectiveDocument13 pagesInterpersonal Harm Aversion As A Necessary Foundation For Morality: A Developmental Neuroscience PerspectiveAleja ToPaNo ratings yet

- Attachment and Borderline Personality DisorderDocument18 pagesAttachment and Borderline Personality Disorderracm89No ratings yet

- Fisher Et Al. (2017)Document13 pagesFisher Et Al. (2017)ManthanNo ratings yet

- The Cognitive Emotional and Social Sequlae of Stroke Psychological and Ethical Concern in Post Stroke AdaptationDocument11 pagesThe Cognitive Emotional and Social Sequlae of Stroke Psychological and Ethical Concern in Post Stroke AdaptationFahim Abrar KhanNo ratings yet

- Watsonand Friend 1969Document11 pagesWatsonand Friend 1969LizbethNo ratings yet

- Redes SocialesDocument30 pagesRedes SocialesSofia Ramirez HoyosNo ratings yet

- Material Psicosis 5Document6 pagesMaterial Psicosis 5ALEJANDRO PALMA SOTONo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument29 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptMarisa CostaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0193953X06000074 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0193953X06000074 Mainkuniari sftr077No ratings yet

- Meta AnálisisDocument95 pagesMeta AnálisisSofia DibildoxNo ratings yet

- Social Anxiety and Social CognitionDocument14 pagesSocial Anxiety and Social CognitionDaniela Alvarez ForeroNo ratings yet

- Detecting Mental Disorders in Social Media Through Emotional Patterns - The Case of Anorexia and DepressionDocument12 pagesDetecting Mental Disorders in Social Media Through Emotional Patterns - The Case of Anorexia and DepressionPrerna RajNo ratings yet

- Hat Zen Buehler 2009Document24 pagesHat Zen Buehler 2009Dian Rachmah FaoziahNo ratings yet

- Wen 2021Document8 pagesWen 2021Xi WangNo ratings yet

- Schoen, C. B & Holtzer, R. (2017)Document17 pagesSchoen, C. B & Holtzer, R. (2017)rifqohNo ratings yet

- 2.A Multilevel Analysis of The Self-Presentation Theory of Social Anxiety Contextualized, Dispositional, and Interactive PerspectivesDocument13 pages2.A Multilevel Analysis of The Self-Presentation Theory of Social Anxiety Contextualized, Dispositional, and Interactive PerspectivesBlayel FelihtNo ratings yet

- Correlates and Consequences of Internalized Stigma For People Living With Mental IllnessDocument12 pagesCorrelates and Consequences of Internalized Stigma For People Living With Mental IllnessBruno HenriqueNo ratings yet

- Aa 5Document29 pagesAa 5api-395503981No ratings yet

- Journal of Personality Assessment Volume 47 Issue 1 1983 (Doi 10.1207/s15327752jpa4701 - 8) Leary, Mark R. - Social Anxiousness - The Construct and Its MeasurementDocument11 pagesJournal of Personality Assessment Volume 47 Issue 1 1983 (Doi 10.1207/s15327752jpa4701 - 8) Leary, Mark R. - Social Anxiousness - The Construct and Its MeasurementMilosNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: The Neuroscience of Social Feelings: Mechanisms of Adaptive Social FunctioningDocument71 pagesHHS Public Access: The Neuroscience of Social Feelings: Mechanisms of Adaptive Social FunctioningstefanyNo ratings yet

- Brunell 2019Document6 pagesBrunell 2019Joana RibeiroNo ratings yet

- JEduHealthPromot91157-4175279 113552Document8 pagesJEduHealthPromot91157-4175279 113552MCarmen MartinezNo ratings yet

- Predicting Suicidal Ideation in Adolescent Boys and Girls The Ro 2018Document12 pagesPredicting Suicidal Ideation in Adolescent Boys and Girls The Ro 2018kuntobimo2016No ratings yet

- Granieri, 2018Document8 pagesGranieri, 2018Zeynep ÖzmeydanNo ratings yet

- (2021) - Empathy and The Ability To Experience One's Own Emotions Modify The Expression of Blatant and Subtle Prejudice Among Young Male AdultsDocument9 pages(2021) - Empathy and The Ability To Experience One's Own Emotions Modify The Expression of Blatant and Subtle Prejudice Among Young Male AdultsBruno SallesNo ratings yet

- Clanek 2Document12 pagesClanek 2xetox97186No ratings yet

- The Recovery of Metacognitive Capacity in Schizophrenia Across 32 Months of Individual Psychotherapy: A Case StudyDocument9 pagesThe Recovery of Metacognitive Capacity in Schizophrenia Across 32 Months of Individual Psychotherapy: A Case StudyCeline WongNo ratings yet

- Transactional TheoryDocument24 pagesTransactional TheoryVaishnav VinodNo ratings yet

- Journal of Affective Disorders: Social Anxiety and Depression Stigma Among AdolescentsDocument10 pagesJournal of Affective Disorders: Social Anxiety and Depression Stigma Among AdolescentsPutri Indah PermataNo ratings yet

- Cruwys Et Al - When Trust Goes WrongDocument27 pagesCruwys Et Al - When Trust Goes WrongBill KeepNo ratings yet

- MEASUREMENT OF SOCIAL-EVALUATIVE ANXIETY - WatsonDocument10 pagesMEASUREMENT OF SOCIAL-EVALUATIVE ANXIETY - WatsonAjeng Putri SetiadyNo ratings yet

- Empathy, Stress & Memory 1Document9 pagesEmpathy, Stress & Memory 1api-595934402No ratings yet

- Vidaletal - PsychopathyandEI PDFDocument15 pagesVidaletal - PsychopathyandEI PDFMagally RinconNo ratings yet

- Topic 12 Hbse 4Document15 pagesTopic 12 Hbse 4Mary France Paez CarrilloNo ratings yet

- ASP2Document10 pagesASP2Hiba ThahseenNo ratings yet

- TOM and SADDocument3 pagesTOM and SADLENIN JEAN MARTIN BENDEZU ZARATENo ratings yet

- Social Anxiety and Its Effects1Document12 pagesSocial Anxiety and Its Effects1api-395503981No ratings yet

- Thinking Anxious, Feeling Anxious, or Both Cognitive Bias ModeratesDocument22 pagesThinking Anxious, Feeling Anxious, or Both Cognitive Bias ModeratesNASC8No ratings yet

- 7616 22975 1 PBDocument8 pages7616 22975 1 PBanindita tanayaNo ratings yet

- Attachment Security and Suicide Ideation and Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Reflective FunctioningDocument19 pagesAttachment Security and Suicide Ideation and Behaviour: The Mediating Role of Reflective FunctioningNicoleNo ratings yet

- Esquizofrenia CogniciónDocument1 pageEsquizofrenia CogniciónWendy RamírezNo ratings yet

- Social Anxiety Study Based On Coping Sty PDFDocument8 pagesSocial Anxiety Study Based On Coping Sty PDFAnna ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Theory of Mind 2Document15 pagesResearch Paper Theory of Mind 2api-529331295No ratings yet

- The Psychology of Criminal Conduct: Special SectionDocument10 pagesThe Psychology of Criminal Conduct: Special SectionGyeo MatatabiNo ratings yet

- 2023 - Fares Otero - Association Between Childhood Maltreatment and Social Functioning inDocument23 pages2023 - Fares Otero - Association Between Childhood Maltreatment and Social Functioning inxfxjose14No ratings yet

- Brick Ards Self AwarenessDocument8 pagesBrick Ards Self AwarenessLorenaUlloaNo ratings yet

- Cognitive ModelsDocument4 pagesCognitive Modelssofia coutinhoNo ratings yet

- Guilt and Shame Proneness in Relations To Covert Narcissism Among Emerging AdultsDocument9 pagesGuilt and Shame Proneness in Relations To Covert Narcissism Among Emerging AdultsnamratathenovelistNo ratings yet

- Dobson 2023 Metamorphoses of PsycheDocument281 pagesDobson 2023 Metamorphoses of PsycheCeciliaNo ratings yet

- Relevant Laws in The Practice of PsychologyDocument11 pagesRelevant Laws in The Practice of PsychologyDaegee AlcazarNo ratings yet

- Online Counselling AgreementDocument6 pagesOnline Counselling AgreementFairy AngelNo ratings yet

- Empathy Statements Help Guide PDFDocument3 pagesEmpathy Statements Help Guide PDFglenNo ratings yet

- G. T. N. ARTS COLLEGE (Autonomous)Document1 pageG. T. N. ARTS COLLEGE (Autonomous)Katrina KatNo ratings yet

- Great Man TeoriDocument12 pagesGreat Man TeoriLmay PhangNo ratings yet

- Neuro PDFDocument4 pagesNeuro PDFChris MacknightNo ratings yet

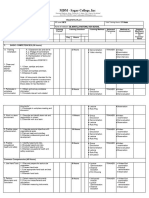

- DLL-Mam SionyDocument4 pagesDLL-Mam SionyCherryl SiquigNo ratings yet

- UDL Guidelines - Educator Checklist: Provide Multiple Means of RepresentationDocument2 pagesUDL Guidelines - Educator Checklist: Provide Multiple Means of Representationapi-530136228No ratings yet

- Aggression and Psychophysical-Health Among Adolescents of Buksa Tribe - Neeta GuptaDocument4 pagesAggression and Psychophysical-Health Among Adolescents of Buksa Tribe - Neeta GuptaProfessor.Krishan Bir SinghNo ratings yet

- Klinger 2014Document4 pagesKlinger 2014Alejandra CachoNo ratings yet

- John DeweyDocument2 pagesJohn DeweySalve May TolineroNo ratings yet

- Dance Movement Psychotherapy With People With Learning Disabilities Out of The Shadows Into The Light 1st EditionDocument5 pagesDance Movement Psychotherapy With People With Learning Disabilities Out of The Shadows Into The Light 1st Editionlamiss slimiNo ratings yet

- Training Plan EIMDocument4 pagesTraining Plan EIMRhyan Paul MontesNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ilmiah Hubungan Pengetahuan Dan Sikap Dengan Motivasi Keluarga Dalam Memberikan Dukungan Pada Klien Gangguan JiwaDocument9 pagesJurnal Ilmiah Hubungan Pengetahuan Dan Sikap Dengan Motivasi Keluarga Dalam Memberikan Dukungan Pada Klien Gangguan JiwaAri HardianiNo ratings yet

- Personality & PsychographicsDocument47 pagesPersonality & PsychographicsBullet Lad100% (1)

- What Are The Principles of GadDocument7 pagesWhat Are The Principles of GadRivin DomoNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Test Bank For Psychology in Everyday Life 4th Edition Myers PDF FullDocument32 pagesInstant Download Test Bank For Psychology in Everyday Life 4th Edition Myers PDF FullLisa Beighley100% (12)

- The Disciplines of CounselingDocument24 pagesThe Disciplines of CounselingMALOU ELEVERANo ratings yet

- Global Development DelayDocument3 pagesGlobal Development DelayMarvie TorralbaNo ratings yet

- (Quarter 2 in English 10 - Notebook # 3) - FORMULATE STATEMENTS OF OPINION OR ASSERTIONDocument5 pages(Quarter 2 in English 10 - Notebook # 3) - FORMULATE STATEMENTS OF OPINION OR ASSERTIONMaria BuizonNo ratings yet

- Embodied Spirit PDFDocument28 pagesEmbodied Spirit PDFLoraine AdacruzNo ratings yet

- (ENG) Psycho-Cybernetics - Maxwell MaltzDocument7 pages(ENG) Psycho-Cybernetics - Maxwell MaltzWierd SpecieNo ratings yet

- A. Questions 1. What Part of Your Body People Can Identify You With?Document3 pagesA. Questions 1. What Part of Your Body People Can Identify You With?Joshua MabilanganNo ratings yet

- 10th 5 E's Lesson Plan-2020-21Document21 pages10th 5 E's Lesson Plan-2020-21shrikant rathodNo ratings yet

- Employability Skills 2022 - 1st YearDocument32 pagesEmployability Skills 2022 - 1st Yearsiyon alappatNo ratings yet

- Discipline and Ideas in Applied Social SciencesDocument19 pagesDiscipline and Ideas in Applied Social SciencesDinamak KalatNo ratings yet

- High Performance Via Psychological SafetyDocument2 pagesHigh Performance Via Psychological SafetyPhilip BorgnesNo ratings yet

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

Uploaded by

Elina Pérez de KleinOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

Uploaded by

Elina Pérez de KleinCopyright:

Available Formats

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

http://psp.sagepub.com

Adult Attachment Dimensions and Specificity of Emotional Distress Symptoms: Prospective

Investigations of Cognitive Risk and Interpersonal Stress Generation as Mediating Mechanisms

Benjamin L. Hankin, Jon D. Kassel and John R. Z. Abela

Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2005; 31; 136

DOI: 10.1177/0146167204271324

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://psp.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/31/1/136

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.

Additional services and information for Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://psp.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://psp.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations (this article cites 33 articles hosted on the

SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms):

http://psp.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/31/1/136

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

10.1177/0146167204271324

PERSONALITY

Hankin et al. / ATTACHMENT

AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY

AND EMOTIONAL

BULLETIN

DISTRESS ARTICLE

Adult Attachment Dimensions and

Specificity of Emotional Distress Symptoms:

Prospective Investigations of Cognitive Risk and

Interpersonal Stress Generation as Mediating

Mechanisms

Benjamin L. Hankin

Jon D. Kassel

University of Illinois, Chicago

John R. Z. Abela

McGill University

Three prospective studies examined the relation between adult 2002) and interpersonal processes (Joiner, 2002) con-

attachment dimensions and symptoms of emotional distress tributing to the development of depressive symptoms.

(anxiety and depression). Across all three studies, avoidant and Although independent bodies of research have pro-

anxious attachment prospectively predicted depressive symp- vided evidence supporting both the cognitive and inter-

toms, and anxious attachment was associated concurrently personal theories, relatively little research has examined

with anxiety symptoms. Study 2 tested a cognitive risk factors models that integrate the cognitive and interpersonal

mediational model, and Study 3 tested an interpersonal stress factors into a more comprehensive model of depression.

generation mediational model. Both cognitive and interper- The few theorists that have attempted to examine the

sonal mediating processes were supported. The cognitive risk fac- etiology of depression from an integrative cognitive-

tors pathway, including elevated dysfunctional attitudes and interpersonal perspective have emphasized the role of

low self-esteem, specifically mediated the relation between inse- early attachment relationships in the development of

cure attachment and prospective elevations in depression but not cognitive and interpersonal vulnerability to depression

anxiety. For the interpersonal stress generation model, experienc- (e.g., Gotlib & Hammen, 1992; Haines, Metalsky,

ing additional interpersonal, but not achievement, stressors over Cardamone, & Joiner, 1999). According to these models,

time mediated the association between insecure attachment and individuals who exhibit insecure attachment to primary

prospective elevations in depressive and anxious symptoms. caregivers are hypothesized to be more likely than

Results advance theory and empirical knowledge about why securely attached individuals to exhibit vulnerability

these interpersonal and cognitive mechanisms explain how factors (e.g., negative representations of the self and

insecurely attached people become depressed and anxious. others) that increase their risk for developing depres-

sion in the future. In the current article, we will examine

(a) whether insecure-attachment dimensions prospec-

Keywords: attachment; depression; anxiety; mediating mechanisms tively predict the development of depressive symptoms

A variety of theoretical models have been proposed to Authors’ Note: Correspondence concerning this article should be ad-

dressed to Benjamin L. Hankin, who is now at the Department of Psy-

explain the etiology of depression (e.g., Abramson,

chology, University of South Carolina, Barnwell College, Columbia, SC

Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989; Beck, 1987; Joiner & Coyne, 29208; e-mail: hankinbl@gwm.sc.edu.

1999). Two of the central etiological theories are cogni-

PSPB, Vol. 31 No. 1, January 2005 136-151

tive and interpersonal models. Research has provided DOI: 10.1177/0146167204271324

support for both cognitive factors (Abramson et al., © 2005 by the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.

136

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Hankin et al. / ATTACHMENT AND EMOTIONAL DISTRESS 137

over time and (b) whether they do so through the medi- individual differences in intimacy and emotional expres-

ating role of cognitive (e.g., dysfunctional attitudes and sion, and the dimension of attachment-related anxiety

low self-esteem) and/or interpersonal (e.g., the occur- represents differences in sensitivity to abandonment,

rence of additional interpersonal stressors) processes. In separation, and rejection. The traditional attachment

addition, we will examine whether insecure-attachment dimension of security (low avoidance and anxiety) to

orientations and each of the proposed cognitive and insecurity (high avoidance and anxiety) is represented

interpersonal mediating processes specifically predict in this two-dimensional model.

depressive symptoms or whether they contribute to Attachment theory and research has progressed from

other forms of emotional distress (i.e., anxiety) as well. its origins in studying infants to more recent applications

and study within adult attachment security. Research has

Attachment Theory During the Life Span

shown that the attachment system is active in adult rela-

Bowlby (1969, 1973, 1980) proposed an ethological tionships (Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Hazan & Zeifman,

theory of attachment and loss that has been used to ex- 1999), and individual differences in attachment dimen-

plain both normal and abnormal behavior, social rela- sions are relatively stable over time from childhood

tionships, cognition, emotions, and personality across through adulthood, although there can be change in in-

the life span. Bowlby posited that infants exhibit attach- dividuals’ attachment orientation (Fraley, 2002; Waters,

ment behaviors, such as seeking contact and proximity Hamilton, & Weinfield, 2000). This is consistent with the

with caregivers, that serve to keep infants in close prox- view that attachment is a process that extends from “the

imity to a primary caregiver. The caregiver’s level of sup- cradle to the grave” (Bowlby, 1969). In infancy, parents

port, responsiveness, and accessibility influences how typically serve as attachment figures; in adulthood, peers

the child forms representations of the self and others. If and romantic partners typically serve as attachment fig-

the caregivers are consistently responsive, available, ures (Fraley & Davis, 1997; Hazan & Zeifman, 1999).

helpful, and warm, then the child likely develops a sense Thus, adults have a need for attachment bonds to others

of security and learns that others can be trusted and sup- during the life span, and individual attachment dimen-

portive when needed (Bretherton, 1985). Repeated in- sions are fairly stable over time.

teractions over time with caregivers contribute to the

Insecure Attachment and Emotional Distress

formation and consolidation of a set of expectations

and beliefs of others’ dependability and supportiveness; In his original writings, Bowlby (1969, 1980) sought to

these expectations are called internal working models understand the intense emotional distress displayed

(Bowlby, 1969, 1973). Internal working models are hy- when children were separated from primary caregivers.

pothesized to influence the capacity for regulating emo- He observed that children often experienced intense

tions and behaviors during the life span. anxiety when separated from their caregivers as mani-

There are individual differences in the working mod- fested by crying, clinging, and searching for their lost

els that people develop in response to variability in the caregiver. Bowlby suggested that this “protest-despair-

caregiver’s behaviors. In their classic book, Ainsworth, detachment” sequence may be used to understand dif-

Blehar, Waters, and Wall (1978) described three attach- ferent depressive experiences ranging from temporary

ment prototypes, including secure, anxious-avoidant, despair over separation to both grief and clinical depres-

and anxious-ambivalent. Most children are securely sion. Thus, Bowlby’s original ideas for understanding

attached and are comfortable seeking contact and com- despair, depression, and loss in children may be applica-

fort with a caregiver after separations. In contrast, ble to understanding vulnerability to depression among

anxious-ambivalent individuals vary between expres- adults.

sions of anger and reassurance seeking after separations Indeed, prior research has shown that insecure at-

from caregivers, whereas anxious-avoidant individuals tachment is associated with depressive symptoms among

typically respond with withdrawal or indifference after adults (e.g., Carnelley, Pietromonaco, & Jaffe, 1994;

separations. Eng, Heimberg, Hart, Schneier, & Liebowitz, 2001;

Subsequent to Ainsworth’s classic work on attach- Roberts, Gotlib, & Kassel, 1996) and youths (Abela et al.,

ment, attachment dimensions have been refined and 2003; Armsden & Greenberg, 1987; Hammen et al.,

studied across the life span. Recently, theoretical 1995; Kobak, Sudler, & Gamble, 1991). Although re-

and empirical research in the attachment literature search has established a correlation between insecure

(Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998; Fraley & Shaver, 2000; attachment and depression, little research has prospec-

Griffin & Bartholomew, 1994) has shown that individual tively explored mechanisms that might mediate this

differences in attachment can be represented by two rel- association. The primary impetus for this investigation is

atively distinct dimensions: avoidance and anxiety. The to examine processes by which insecure attachment

dimension of attachment-related avoidance represents leads to future elevations in depression and to explore

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

138 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN

whether these processes are specific to symptoms of sive reassurance seeking was associated with elevations

depression versus anxiety. in current depressive symptoms and a history of past

depressive episodes in children. Last, interpersonal fac-

Cognitive Mechanisms

tors, including perceptions of spousal anger and low

To date, the few studies that have examined mecha- social support, predicted elevated depressive symptoms

nisms have focused on cognitive risk factors as a poten- among anxiously attached women after the stressful

tial mediator of the attachment-depression association. transition of childbirth (Simpson et al., 2003). To date,

This work is based on Bowlby’s (1980) suggestion that however, no study has examined whether insecurely

internal working models are composed of cognitive- attached individuals experience additional stressors

affective representations of the self and others based on over time and whether the generation of these stressors

past experiences with caregivers. With inadequate, operates as a mediator of the association between inse-

unsupportive, and inconsistent parenting, a child is cure attachment and future depression.

likely to develop negative working models of the self as We hypothesize that insecurely attached individuals

unworthy and unlovable and of others as unsupportive are particularly likely to generate additional interper-

and unreliable. Such negative internal working models sonal stressors over time, and this interpersonal stress

are very similar to those posited by modern theories of generation mechanism is an important interpersonal

cognitive vulnerability to depression (Abramson et al., process that will explain, at least in part, why insecurely

2002). For example, Beck (1987) posited that dysfunc- attached adults are at elevated risk to become depressed.

tional attitudes, which are rigid and extreme beliefs The stress generation mechanism (see Hammen, 1991;

about the self and the world (e.g., “It is awful to be disap- Hankin & Abramson, 2001) posits that these additional

proved of by people important to you,” or “I am nothing stressors are created or generated over time by some-

if a person I love doesn’t love me”), operate as a vul- thing about the individual’s personality or behavior. In

nerability factor for depression. our theoretical integration of attachment theory and

To date, both cross-sectional (Carnelley et al., 1994; stress generation, we posit that insecure attachment is

Whisman & McGarvey, 1995) and short-term prospective such a personality structure that can contribute to the

research (Roberts et al., 1996) have found that cognitive increased likelihood that individuals will create addi-

vulnerability factors (i.e., dysfunctional attitudes) par- tional stressors for themselves as they seek reassurance

tially mediate the insecure attachment–depressive symp- or comfort from close peers, partners, or family mem-

toms link. Furthermore, Roberts and colleagues (1996) bers. According to attachment theory, insecurely

showed that an insecure attachment style was associated attached individuals with negative internal working

with more depresso-typic dysfunctional attitudes, which models of their self and others may act in ways that

in turn contributed to lower self-esteem levels, which in weaken important interpersonal relations and may

turn led directly to elevations in depression. Most alienate peers and partners who can provide social sup-

recently, Simpson, Rholes, Campbell, Tran, and Wilson port. However, no study has examined whether inse-

(2003) showed that cognitive perceptions of a lack of curely attached individuals will create more interper-

spousal support mediated the association between inse- sonal stressors for themselves over time. To date, the

cure attachment and depression after the birth of a child stress generation mechanism has been tested exclusively

only among anxiously attached women. with depressed individuals to investigate the hypothesis

that characteristics of depressed people (e.g., excessive

Interpersonal Mechanisms

reassurance, clinginess, dependency, etc.) would gener-

Although research has recently begun to examine ate more stressors (see Hammen, 1999). Indeed, inter-

cognitive factors as mediators, relatively little research personal depression researchers (e.g., Joiner, 2002;

has examined interpersonal processes that might explain Joiner & Coyne, 1999) have shown that mildly depressed

why insecurely attached individuals experience more individuals often seek reassurance excessively to assuage

emotional distress. This is surprising because attach- their insecurities, pessimistic beliefs, and depressed

ment theory is primarily a theory of interpersonal rela- mood. Furthermore, depressed people typically expect

tionships and social interactions. The few studies to that others will reject them (rejection sensitivity; Ayduk,

explore interpersonal risk factors have all conceptual- Downey, & Kim, 2001) and may inadvertently elicit

ized insecure attachment within a moderational frame- behaviors from others that confirm their negative self-

work. For example, Hammen and colleagues (1995) views (Giesler & Swann, 1999). Taken together, these

found that insecure attachment (the vulnerability) inter- lines of theory and evidence suggest that insecurely

acted with interpersonal stressors to predict depressive attached adults may create additional interpersonal neg-

symptoms. Also, Abela and colleagues (2003) found that ative events in their lives (e.g., breakup of romantic part-

the interaction between insecure attachment and exces- ner, arguments with close friends) while they seek verifi-

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Hankin et al. / ATTACHMENT AND EMOTIONAL DISTRESS 139

cation of their negative internal working models and as 1995; Simpson et al., 2003). Furthermore, whereas some

they seek excessive reassurance from their close friends, past research has investigated a cognitive mediational

romantic partners, and family. Last, we hypothesize that model (e.g., Roberts et al., 1996), none has examined an

insecurely attached individuals will generate additional interpersonal stress generation mediational model.

interpersonal stressors specifically, but not achievement- Within this stress generation model, we also are investi-

related stressors (e.g., failing an exam, losing a job). In- gating different domains of stressors (i.e., interpersonal

securely attached individuals should experience more versus achievement). Attachment theory suggests that

interpersonal stressors, but not any more achievement insecure attachment will predict greater interpersonal

stressors, compared with securely attached people stressors, but not achievement stressors, but no research

because the working models of individuals with inse- has explicitly examined this issue directly. Also, there is

cure attachment are hypothesized to influence the per- little extant research in general that has separated

ception of, and behaviors in, one’s social environment, domains of stressors (e.g., interpersonal and achieve-

whereas the self-views and behaviors in the achievement ment) to explore the discriminant predictive validity of a

domain should not be as affected by an insecure particular domain of stressors with emotional distress

attachment. symptoms (see Kendler, Hettema, Butera, Gardner, &

Prescott, 2003, for a recent exception). Little is known

The Current Research

about how different domains of stressors influence the

The goal of the current study is to examine whether development of different forms of emotional distress

the relationship between insecure attachment and symptoms, and no research has explicitly examined

depressive symptoms is mediated by (a) cognitive vulner- achievement versus interpersonal stressors as a mediator

ability factors (i.e., dysfunctional attitudes and low self- of the insecure-attachment association with emotional

esteem) and (b) interpersonal processes (i.e., the gener- distress symptoms. Thus, the present research can

ation of interpersonal stressors). In addition to investi- advance theory and knowledge on cognitive and inter-

gating mediating processes, we seek to advance the theo- personal mediating mechanisms as well as further

retical and empirical knowledge base and expand on understanding on what types of stressors are most asso-

past research examining the association between inse- ciated with insecure attachment and emotional distress.

cure attachment and depression in at least three impor- Third, surprisingly few prior studies have examined

tant ways. whether insecure attachment is associated specifically

First, the majority of past studies have been cross- with depressive symptoms or whether it is also associated

sectional. As such, they cannot sufficiently distinguish with other types of emotional distress. Such research is

between insecure attachment as a cause, correlate, or needed because (a) insecure attachment is theoretically

consequence of depression (Barnett & Gotlib, 1988; linked to both depression and anxiety (e.g., Cassidy,

Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord, & Kupfer, 2001). Conse- 1995), and (b) depressive and anxious symptoms fre-

quently, we used longitudinal designs in all three studies quently co-occur at very high levels (e.g., concurrent cor-

to establish temporal precedence and disentangle these relations often range r = .6 to .7; Mineka, Watson, &

possibilities. In addition, in Studies 1 and 2, we assessed Clark, 1998). Given the strong overlap between anxiety

attachment dimensions and symptoms of emotional dis- and depression, numerous authors (e.g., Hammen &

tress (both anxiety and depression) at two time points, Rudolph, 2003; Mineka et al., 1998) have argued persua-

whereas past studies have only measured attachment ori- sively that research investigating risk factors and pro-

entations at an initial baseline time point and not at a cesses for emotional distress needs to assess and examine

prospective follow-up. Prospectively assessing both both anxiety and depressive symptoms; otherwise, it is

attachment dimensions and symptoms is important impossible to discern whether the risk processes (cogni-

because individual differences in attachment dimen- tive or interpersonal) actually predict specific affective

sions are not entirely stable, so it is virtually unknown symptoms as hypothesized in a causal theory or emo-

whether different forms of emotional distress (i.e., anxi- tional distress in general.

ety and depression) will be prospectively predicted by or The few studies that have examined emotional symp-

only concurrently associated with insecure attachment tom specificity have been mostly cross-sectional and

after accounting for the stability of the attachment explored only social anxiety, even though there are dif-

dimensions at both time points. ferent facets of anxiety, including symptoms of gen-

Second, as introduced earlier, we are examining both eral anxiety and physiological/anxious arousal (Clark &

cognitive and interpersonal mediational models, Watson, 1991). The cross-sectional studies suggest that

whereas most prior studies have explicitly or implicitly insecure attachment is a nonspecific risk factor for both

tested moderational models (e.g., insecure attachment depression and social anxiety (Eng et al., 2001;

vulnerability interacting with stress; Hammen et al., Mickelson, Kessler, & Shaver, 1997; see also Hammen

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

140 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN

et al., 1995 for a longitudinal study). Consequently, to administered a battery of questionnaires in groups of 15

examine more rigorously the symptom specificity of to 20 individuals on two occasions (Times 1 and 2) sep-

insecure attachment as a risk factor for emotional dis- arated by an 8-week interval.

tress, we included prospective assessments of both MEASURES

depressive and anxious symptoms (both general and

anxious arousal). In addition, the studies that tested a Adult attachment dimensions. Collins and Read’s (1990)

cognitive factors mechanism (Carnelley et al., 1994, 18-item inventory was used to measure adult attachment

Roberts et al., 1996; Simpson et al., 2003; Whisman & and was administered at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2).

McGarvey, 1995) only examined symptoms of depres- Three scales are assessed with this measure: the extent to

sion, not anxiety, so the emotional specificity of the cog- which an individual is comfortable with closeness

nitive factors mechanism is unclear. Cognitive vulnera- (Close), feels that others are dependable (Depend), and

bility models of depression (e.g., Hankin & Abramson, is fearful about being unloved or abandoned (Anxiety).

2001) posit that cognitive risk factors and processes Participants rated items on a 5-point scale. A principal

should specifically predict elevations of depression, not factor analysis with varimax rotation of these 18 items

anxiety, and the few studies to test this prediction are extracting two factors resulted in a solution with good

largely supportive (e.g., Hankin, Abramson, Miller, & factor interpretability, and both factors had eigenvalues

Haeffel, 2004). As no research has investigated an inter- greater than 1. The first factor (eigenvalue = 4.79)

personal stress mechanism, the affective symptom speci- explained 26.6% of the variance, and the second factor

ficity of this process to anxiety and depression is (eigenvalue = 2.25) explained 12.5% of the variance; the

unknown. Thus, our prospective studies are poised to two factors combined accounted for 39% of the vari-

advance theory and evidence on the specificity of inse- ance. The first factor consisted of a combination of items

cure attachment as a predictor of anxiety versus from the Close and Depend Scales, and the second fac-

depression and on the affective specificity of cognitive tor was composed of items from the Anxiety Scale. Based

and interpersonal mediators. on this factor analysis and the theoretical views of attach-

To examine these issues, we report data from 3 sepa- ment as two dimensions (Fraley & Shaver, 2000), the

rate prospective studies. In these studies, we examined Close and Depend Scales were collapsed and reverse

the concurrent and prospective relation of the two scored to create an overall Avoidant Attachment Scale,

attachment dimensions (avoidant and anxiety) as pre- and Anxiety represented the Anxiety attachment dimen-

dictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms. In Study 1, sion. Coefficient alphas were .77 for Avoidance and .79

we assessed whether the attachment dimensions were for Anxiety.

associated either concurrently or prospectively with anx- Depressive symptomatology. The Inventory to Diagnose

iety and depressive symptoms over an 8-week follow-up. Depression (IDD; Zimmerman, Coryell, Corenthal, &

In Study 2, we measured attachment dimensions, dys- Wilson, 1986), administered at T1 and T2, was used to

functional attitudes, self-esteem, anxiety, and depressive measure depressive symptomatology during the pre-

symptoms over an 8-week interval to examine cognitive vious week. The IDD has good validity (Zimmerman

mediating processes. Study 3 used a 2-year follow-up in et al., 1986). Alpha coefficients at Times 1 and 2 were .92

which the attachment dimensions, interpersonal and and .94.

achievement negative life events, as well as anxiety and

depressive symptoms were assessed to examine an inter- Anxiety. The State Anxiety subscale of the State-Trait

personal stress generation mechanism. Anxiety Inventory Form Y (STAI-S; Spielberger,

Gorsuch, & Lushene, 1983), administered at T1 and T2,

was used to assess general anxiety during the past week.

STUDY 1

The STAI-S is a 20-item scale including feelings of ner-

Method vousness, tension, and worry. Participants respond to

statements on a 4-point scale. The psychometric prop-

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURES erties of the STAI are excellent and well established

Participants were undergraduate students who volun- (Spielberger et al., 1983). Coefficients alphas at T1 and

teered for extra credit for their Introduction to Psychol- T2 were .94 and .95.

ogy at a large southeastern university. Only those stu- Results

dents who completed questionnaires at both time points

were included, resulting in a final sample size of 187. Descriptive statistics. Table 1 provides the means, stan-

Ages of participants ranged from 17 to 24 years with the dard deviations, and correlations among all variables.

mean age (± SD) being 18.4 ± 0.87. The majority (81.4%) Table 1 reveals moderate associations between both Anx-

were female and Caucasian (89%). Participants were ious and Avoidant attachment dimensions and symp-

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Hankin et al. / ATTACHMENT AND EMOTIONAL DISTRESS 141

TABLE 1: Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Main Measures in Study 1 (N = 187)

Measure 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1. ANXIOUS1

2. AVOIDANT1 .15*

3. STAI1 .42*** .34***

4. DEPRESS1 .35*** .22** .51***

5. ANXIOUS2 .51*** .13 .34*** .38***

6. AVOIDANT2 .15* .66*** .32*** .27*** .17*

7. STAI2 .19** .18* .43*** .62*** .26*** .19**

8. DEPRESS2 .38*** .37*** .68*** .62*** .35*** .30*** .35***

M 16.07 40.61 45.50 12.80 16.20 40.89 45.80 10.47

SD 4.53 7.75 13.89 9.49 4.45 7.50 14.05 8.93

Skew 0.37 –0.26 0.35 1.44 0.24 –0.05 0.29 1.57

NOTE: ANXIOUS = anxious attachment style; AVOIDANT = avoidant attachment style; DEPRESS = Inventory to Diagnose Depression Question-

naire; STAI = Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

TABLE 2: Structural Equation Modeling Results for Associations

Between Attachment Dimensions and Emotional Distress

EMOTIONAL EMOTIONAL Symptoms in Study 1 (N = 187)

DISTRESS DISTRESS

SYMPTOMS T1 SYMPTOMS T2 β

Coefficient

Parameter Estimate χ2 df CFI RMSEA

ANXIETY ANXIETY Depression model .67 3 1.0 0.0

ATTACHMENT ATTACHMENT

T1 T2 T1 ANXIOUS → T2 DEPRES .15**

T1 AVOID → T2 DEPRES .26***

T2 ANXIOUS → T2 DEPRES .05

T2 AVOID → T2 DEPRES .04

AVOIDANT AVOIDANT

ATTACHMENT ATTACHMENT T2 T1 DEPRES → T2 ANXIOUS .23***

T1 T1 DEPRES → T2 AVOID .13**

T1 DEPRES → T2 DEPRES .50***

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 ANXIOUS .42***

T1 AVOID → T2 AVOID .63***

Figure 1 Structural equation model depiction of concurrent and

prospective associations between insecure attachment Anxiety model 1.12 3 1.0 .02

dimensions (attachment-related avoidance and T1 ANXIOUS → T2 STAI .06

attachment-related anxiety) and symptoms of emotional T1 AVOID → T2 STAI .02

distress assessed (anxiety and depression) at Times 1 and T2 ANXIOUS → T2 STAI .16**

2 (Study 1). T2 AVOID → T2 STAI .05

NOTE: T = time interval. T1 STAI → T2 ANXIOUS .16**

T1 STAI → T2 AVOID .10*

T1 STAI → T2 ANXIOUS .39***

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 ANXIOUS .44***

T1 AVOID → T2 AVOID .63***

toms of anxiety and depression. Anxiety and depression

correlated strongly at both time points. Individuals who NOTE: ANXIOUS = anxious attachment style; AVOIDANT = avoidant

were highly avoidant or anxious in attachment reported attachment style; DEPRES = Inventory to Diagnose Depression Ques-

tionnaire; STAI = Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory; T1 = Time 1;

heightened levels of anxiety and depression symptoms at T2 = Time 2; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA = root mean square

both T1 and T2. error of approximation.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) of insecure attachment

and emotional distress. We fit structural equation models

(Arbuckle, 1999) that included paths from anxious

attachment and avoidant attachment to symptoms of T1 anxious attachment and T1 avoidant attachment pre-

emotional distress at T1 and T2 (see Figure 1). Table 2 dicted T2 depressive symptoms even after controlling

reports the results of these SEMs fitted for depressive for T1 depression, although neither anxiety nor

and anxiety symptoms separately. The models for avoidant attachment at T2 remained as predictors of T2

depressive and general anxiety symptoms both fit well. depressive symptoms. Also, general anxiety symptoms

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

142 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN

were associated concurrently with T2 anxious attach- course credit. Only those students who completed ques-

ment but not avoidant attachment after controlling for tionnaires at both time points were included, resulting

T1 general anxiety. Neither T1 anxiety nor avoidant in a final sample size of 202. Ages of participants ranged

attachment predicted T2 general anxiety symptoms from 17 to 26 years with the mean age (± SD) being 19.5

after partialing T1 general anxiety symptoms. ± 2.08. The majority (75%) were female, with 43%

Caucasian, 31% Asian, 9% African American, and 17%

Discussion Study 1

Hispanic. Participants were administered a battery of

Findings from Study 1 implicate the potential role of questionnaires in groups of 5 to 15 individuals on two

adult attachment dimensions in contributing to emo- occasions (T1 and T2) separated by an 8-week interval.

tional distress symptoms, including general depressive MEASURES

and anxious symptoms. Anxiety and Avoidance attach-

ment dimensions, assessed at T1, independently pre- Adult attachment dimensions. As with Study 1, Collins

dicted prospective elevations of symptoms of depression and Read’s (1990) measure was used at both T1 and T2.

at T2 even after controlling for T1 symptoms. These Coefficient alphas were .74 for Avoidance and .84 for

results are consistent with previous studies reporting Anxiety at T1.

prospective associations between adult attachment and Depressive symptomatology. The IDD was used at T1 and

depression (e.g., Carnelley et al., 1994). Regarding affec- T2 to assess depressive symptoms experienced in the

tive symptom specificity, anxious attachment, but not past week. Alpha coefficients at T1 and T2 were .89 and

avoidant attachment, assessed at T2, was associated con- .90, respectively.

currently with anxiety symptoms at T2 after controlling

Anxiety. The STAI-S was given at T1 and T2 to measure

for T1 anxiety symptoms and T1 attachment dimen-

anxiety during the past week. Coefficients alphas at T1

sions. This finding appears consistent with the past cross-

and T2 were .92 and .93.

sectional studies that found insecure attachment cor-

related concurrently with both anxiety and depression Dysfunctional attitudes. The Dysfunctional Attitudes

(Eng et al., 2001; Mickelson et al., 1997). Our findings Scale (DAS; Weissman & Beck, 1978) is a 40-item ques-

replicate and extend this pattern because we assessed tionnaire assessing beliefs that reflect maladaptive con-

attachment dimensions and emotional distress symp- tingencies of self-worth. Items such as “If I fail at my

toms at both time points, so we could more rigorously work, then I am a failure as a person” and “I do not need

examine the predictive ability of insecure attachment the approval of other people in order to be happy” (re-

after modeling the moderate stability in individual dif- verse scored) are rated on a 7-point scale. Higher scores

ferences in attachment over time. In sum, Study 1 and reflect more dysfunctional attitudes. The DAS has estab-

past research show that anxious and avoidant attach- lished validity (Abramson et al., 2002). Coefficient alpha

ment dimensions are prospective predictors of changes was .93. The DAS was given at T1.

in depressive symptoms but may only concurrently cor- Self-esteem. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) is

relate with anxiety symptoms. a measure of global self-regard consisting of 10 items

In Study 2, we examined potential cognitive media- (Rosenberg, 1979). The questionnaire was scored on a 5-

tors of these relationships. We examined whether dys- point Likert-type scale. Higher scores reflect more posi-

functional attitudes and depleted levels of self-esteem tive self-esteem. The RSE has established validity (e.g.,

would mediate the association between insecure attach- Roberts et al., 1996). Coefficient alpha was .86. The RSE

ment and depressive symptoms (see also Roberts et al., was given at T2.

1996). In addition to replicating this cognitive risk path-

way with depression, we advance knowledge in this area Results

by examining whether this mediating cognitive pathway

Descriptive statistics. Table 3 shows the means, standard

is affectively specific to depression or predictive of anxi-

deviations, and correlations among all variables.

ety as well.

Avoidant and Anxiety attachment were negatively associ-

ated with self-esteem and positively related to affective

STUDY 2 distress and dysfunctional attitudes.

Method SEM of a cognitive factors mediational pathway accounting

for the association between attachment and emotional distress.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURES

We fit a series of structural equation models that in-

Participants were undergraduate students from an cluded the paths from anxious attachment and avoidant

Introduction to Psychology class at a large, ethnically attachment to emotional distress symptoms at T1 and T2

diverse midwestern university who volunteered for (see Figure 2 for an illustration). On the basis of criteria

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Hankin et al. / ATTACHMENT AND EMOTIONAL DISTRESS 143

TABLE 3: Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Main Measures in Study 2 (N = 202)

Measure 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

1. ANXIOUS1

2. AVOIDANT1 .17*

3. STAI 1 .45*** .40***

4. DEPRESS1 .39*** .42*** .71***

5. ANXIOUS2 .55*** .18* .37*** .37***

6. AVOIDANT2 .22** .68*** .33*** .34*** .21**

7. STAI 2 .37*** .33*** .67*** .56*** .31*** .30***

8. DEPRESS2 .33*** .33*** .48*** .66*** .33*** .31*** .70***

9. SELF-ESTEEM –.43*** –.32*** –.53*** –.54*** –.33*** –.33*** –.48*** –.59***

10. DAS .44*** .30*** .37*** .35*** .35*** .24** .39*** .32*** –.47***

M 14.41 40.17 43.04 13.66 16.06 40.60 43.71 11.26 38.12 120.30

SD 4.37 8.24 13.28 9.49 4.42 7.46 13.34 10.85 8.75 29.80

Skew 0.36 –0.28 0.32 1.35 0.28 –0.08 0.26 1.32 –0.75 0.48

NOTE: ANXIOUS = anxious attachment style; AVOIDANT = avoidant attachment style; DEPRESS = Inventory to Diagnose Depression Question-

naire; STAI = Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory; DAS = Dysfunctional Attitude Questionnaire.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Avoidant

Attachment

Anxious

Attachment

Emotional

Emotional Distress Dysfunctional Self-Esteem T2 Distress

Symptoms T1 Attitudes T1 Symptoms T2

Figure 2 Depiction of a cognitive risk factors pathway involving dysfunctional attitudes and self-esteem as mediators of the association

between adult attachment dimensions and emotional distress symptoms (Study 2).

NOTE: Solid lines indicate direct paths, and dotted lines indicate indirect paths in the model. T = time interval.

for testing and establishing mediation (e.g., Baron & as well as dysfunctional attitudes and attachment dimen-

Kenny, 1986; Kenny, Kashy, & Bolger, 1998), we first fit a sions as predictors of emotional distress symptoms.

model to examine the effect from insecure attachment Mediation is supported in this model if (a) self-esteem is

to emotional distress symptoms (as done in Study 1, so associated with emotional distress symptoms, (b) the

this step provides a replication of Study 1). The second effect of DAS on emotional distress is reduced, and (c)

model included the mediating effect of dysfunctional the effect of insecure attachment dimensions on emo-

attitudes as well as attachment dimensions predicting tional distress is reduced.

emotional distress outcomes. Here, it is important to ver- Table 4 shows that the initial models for depressive

ify whether (a) attachment dimensions predict DAS and and general anxiety symptoms both fit well and repli-

(b) DAS predicts symptoms of emotional distress. The cated the results from Study 1. T1 anxious and avoidant

third model included the mediating effect of self-esteem attachment predicted T2 depressive symptoms even

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

144 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN

TABLE 4: Structural Equation Modeling Results Examining was negatively associated with T2 depressive symptoms,

Cognitive Factors as Mediators Between Attachment and neither dysfunctional attitudes nor insecure attach-

Dimensions and Emotional Distress Symptoms in

ment dimensions predicted T2 depressive symptoms

Study 2 (N = 202)

with self-esteem in the model. More important, the in-

β clusion of self-esteem and dysfunctional attitudes in the

Coefficient model reduced the avoidant attachment and depression

Parameter Estimate χ2 df CFI RMSEA association (70%) and the anxious attachment and de-

Depression model—Step 1 1.03 3 1.0 0.0 pression association (46%).

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 DEPRES .15**

Discussion Study 2

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 DEPRES .27**

T2 ANXIOUS → T2 DEPRES .06 Results from Study 2 replicate and extend the find-

T2 AVOIDANT → T2 DEPRES .05

ings from Study 1. Insecure attachment dimensions,

Depression model—Step 2 3.49 3 1.0 0.0

T1 DAS → T2 DEPRES .23*** assessed at T1, predicted prospective changes in depres-

T1 ANXIOUS → T1 DAS .39*** sive symptoms during the follow-up, whereas only anx-

T1 AVOIDANT → T1 DAS .31** ious insecure attachment was associated concurrently

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 DEPRES .10 with T2 anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, in seeking to

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 DEPRES .21**

explain how insecure attachment is associated with emo-

Depression model—Step 3 6.45 3 1.0 .00

T2 RSE → T2 DEPRES –.31*** tional distress symptoms, Study 2’s results replicate past

T1 DAS → T2 RSE –.39*** research (e.g., Roberts et al., 1996) in showing that cog-

T1 DAS → T2 DEPRES .11 nitive factors represent one mediational pathway capa-

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 DEPRES .08 ble of explaining the association between insecure

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 DEPRES .08

attachment and later depressive symptoms. Insecure

Anxiety model—Step 1 1.63 3 1.0 .00

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 STAI .06 attachment was associated with dysfunctional attitudes,

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 STAI .03 which predicted lowered self-esteem, and in turn, poor

T2 ANXIOUS → T2 STAI .17** self-esteem was associated with elevated depressive

T2 AVOIDANT → T2 STAI .05 symptoms. In a novel extension, we investigated affective

Anxiety model—Step 2 1.97 3 1.0 .00

symptom specificity of this cognitive risk factors pathway

T1 DAS → T2 STAI .03

T2 ANXIOUS → T1 DAS .12* and found that it accounted for the insecure attachment

T2 AVOIDANT → T1 DAS .03 association with depression, but not anxiety symptoms.

T2 ANXIOUS → T2 STAI .16** Thus, these cognitive vulnerabilities were specific pre-

T2 AVOIDANT → T2 STAI .04 dictors of depression only.

NOTE: Only the paths required for demonstrating mediation are

shown. ANXIOUS = anxious attachment style; AVOIDANT = avoidant STUDY 3

attachment style; DEPRES = Inventory to Diagnose Depression Ques-

tionnaire; STAI = Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory; RSE =

Rosenberg Self-Esteem; DAS = Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale; T1 =

Method

Time 1; T2 = Time 2; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA = root mean

square error of approximation. PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURES

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. Participants were undergraduate students from an

Introduction to Psychology class at a different large mid-

western university who volunteered for extra credit. Par-

after controlling for T1 depression. General anxiety ticipants’ ages ranged from 18 to 23 (M = 18.6, SD = .84);

symptoms were associated concurrently with T2 anxious more than 90% of the sample was Caucasian. Partici-

attachment but not avoidant attachment after control- pants completed a packet of questionnaires for the ini-

ling for T1 anxiety. For the second condition of media- tial assessment (T1). They were then invited to complete

tion for depressive symptoms, T1 insecure attachment a follow-up assessment (T2) that occurred 2 years after

dimensions were associated with dysfunctional attitudes, the initial assessment. The participants who completed

and dysfunctional attitudes predicted T2 depressive the follow-up packet of questionnaires were paid for

symptoms. In contrast, for anxiety symptoms, dysfunc- their time. A total of 233 (70 male) participants com-

tional attitudes did not predict T2 anxiety symptoms, pleted the follow-up assessment. Twenty-five participants

although insecure attachment styles were associated declined participation in the follow-up; this resulted in

with dysfunctional attitudes. Thus, the cognitive factors an overall 90.3% retention rate during the 2-year follow-

mediational pathway is not supported for anxiety symp- up. There were no significant differences on any mea-

toms. Finally, the third condition of mediation for sures between the group who completed the follow-up

depressive symptoms was also supported. Self-esteem assessment and those who did not.

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Hankin et al. / ATTACHMENT AND EMOTIONAL DISTRESS 145

MEASURES NLEQ’s validity has been demonstrated in previous re-

search (e.g., Metalsky & Joiner, 1992). The NLEQ was

Adult Attachment Questionnaire (AAQ). The AAQ was

given at T1 and T2.

used to assess participants’ adult attachment dimen-

sions. The AAQ was based on Hazan and Shaver’s (1987) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Ward, Mendelson,

three attachment prototype descriptions. Instead of Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). The BDI assesses levels of

their forced-choice assessment, a 10-item questionnaire depressive symptoms with 21 items rated on a scale from

was created based on Hazan and Shaver’s (1987) attach- 0 to 3. Scores range from 0 to 63, and higher scores

ment descriptions. Respondents rated these 10 items for reflect more depressive symptoms. The BDI is a reliable

the degree to which secure, avoidant, and anxious adult and well-validated measure of depressive symptom-

attachment statements described them using a 7-point atology (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988), although it does

scale. An Anxious Attachment Scale and an Avoidant not enable diagnoses of depression. Participants were

Attachment Scale were created from the 10 AAQ items instructed to respond to the items thinking about the 1

based on recent theoretical and empirical research in week in the past 2 years when they had been feeling the

the adult attachment literature (Fraley & Shaver, 2000). most depressed. This methodology of thinking about a

A principal factor analysis with varimax rotation of these 1-week period when most depressed has been used suc-

10 items resulted in a two-factor solution based on the cessfully and been shown to be valid in previous research

scree criterion, factor interpretability, and eigenvalues (e.g., Hankin et al., 2004; Zimmerman et al., 1986).

greater than 1 as estimation criteria. The first factor Coefficient alpha for the BDI was .88. The BDI was given

(eigenvalue = 3.15) explained 31.5% of the variance, at T1 and T2. The mean at T1 was 12.94 (SD = 9.05), and

and the second factor (eigenvalue = 1.65) explained T2 was 15.96 (SD = 10.3).

16.5% of the variance; the two factors combined Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (MASQ;

accounted for 48% of the variance. Based on this factor Watson et al., 1995). This questionnaire contains 90 items

analysis and consistent with the more recent theoretical to assess the general distress and specific anxiety and

views of attachment as two dimensions, 6 items were depression symptoms based on the tripartite theory of

summed to create the Avoidant Attachment Scale (co- anxiety and depression (Clark & Watson, 1991). The

efficient alpha = .67), and 4 items comprised the MASQ subscales, General Distress: Depression (GDDEP),

Anxious Attachment Scale (alpha = .71). The AAQ was General Distress: Anxiety (GDANX), Anhedonic De-

given at T1. pression (DEP), and Anxious Arousal (ANXAR) were

Negative Life Events Questionnaire (NLEQ; Metalsky & used in this study. Examples of GDDEP include “felt

Joiner, 1992). The NLEQ assesses negative life events sad,” DEP include “felt cheerful” (reverse scored),

typically occurring among young adults. It assesses a GDANX include “felt afraid,” and ANXAR include “felt

broad range of life events from school/achievement faint.” According to the tripartite model, anhedonic

to interpersonal/romantic difficulties. Scores on the depression is a relatively more specific measure of

NLEQ are counts of stressors and range from 0 to 67. depression, and anxious arousal is a relatively more spe-

Higher scores reflect the occurrence of more negative cific measure of anxiety, compared with other com-

events. Participants were instructed to indicate which of monly used affective symptom scales that are saturated

these 67 events had occurred to them during the 2-year with high levels of nonspecific negative affect. The

follow-up. Prior to conducting analyses, we created a pri- MASQ scales were used to provide multiple, theoreti-

ori variables for negative life events in the interpersonal cally based, measures of emotional distress symptoms in

and achievement domains. Events in the achievement order to cover the general and specific affective aspects

domain (14 events) included items involving poor aca- of anxiety and depression. Higher scores on each of the

demics (e.g., “did poorly on, or failed, an exam or major subscales reflect greater levels of depressive or anxious

project in an important course” or work (e.g., “got laid symptomatology. Reliability and validity of the MASQ

off or fired from work”). Events in the interpersonal has been demonstrated in previous studies (e.g., Watson

domain (35 events) included items covering family et al., 1995). Participants were asked to respond to the

problems (e.g., “significant fight or argument with close items thinking about the 1 week in the past 2 years when

family member that led to serious consequences”), peer they had been feeling most upset. Coefficient alpha for

problems (e.g., “close friend has been withdrawing GDDEP was .92, for GDANX was .81, for ANXAR was .86,

affection from you”), and romantic problems (e.g., and for DEP was .92. The MASQ was given at T1 and T2.

“discovered boyfriend/girlfriend/spouse has been Results

cheating on you”). The remaining 18 events were nei-

ther clearly interpersonal nor achievement related and Preliminary analyses. For the purpose of analyses, two

so were not included in the current analyses. The composite symptom variables were created: a composite

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

146 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN

TABLE 5: Descriptive Statistics and Correlations Among Main Measures in Study 3 (N = 233)

Measure 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

1. ANXIOUS

2. AVOIDANT .33***

3. ANX1 .27*** .21***

4. DEPRESS1 .38*** .33*** .59***

5. ANX2 .37*** .27*** .49*** .46***

6. DEPRESS2 .47*** .37*** .42*** .65*** .66***

7. INTNLEQ2 .40*** .34*** .19** .23*** .35*** .41***

8. ACHNLEQ2 .16* .17** .15* .24*** .13* .20** .36***

M 5.37 2.63 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 15.17 4.55

SD 5.19 6.93 1.86 1.92 1.88 1.69 6.5 1.41

Skew 0.47 0.17 1.24 1.14 1.21 0.80 –0.09 –1.25

NOTE: ANXIOUS = anxious attachment style; AVOIDANT = avoidant attachment style; DEPRESS = composite depressive symptoms variables;

ANX = composite anxiety symptoms variable; INTNLEQ = interpersonal negative life events; ACHNLEQ = achievement negative life events.

*p <.05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

depressive symptoms variable (DEPRES) and a compos- as well as the attachment dimensions predicting emo-

ite anxiety symptoms variable (ANX). To form these vari- tional distress outcomes while controlling for T1 symp-

ables, each of the depressive symptom measures (BDI, toms and stressors. By controlling for initial stressors in

GDDEP, and DEP) and the anxiety symptom measures this model, we are examining prospective changes in

(GDANX and ANXAR), respectively, were standardized. negative life events beyond the effect of individuals’

We then summed the standardized depression measures usual stressor levels; this analytic strategy enables us to

to create the composite depression variable, and we investigate the stress generation hypothesis as opposed

summed the standardized anxiety measures to create the to merely the presence of typical levels of stressors. In

composite anxiety variable. This procedure creates this model, it is important to see that (a) attachment

highly reliable depression and anxiety variables. dimensions predict additional stressors, and (b) these

Descriptive statistics and the correlation matrix for stressors predict symptoms of emotional distress. In

the main variables are presented in Table 5. Both anx- these models, mediation is supported if (a) T1 insecure

ious and avoidant attachment dimensions moderately attachment predicts emotional distress symptoms at T2

correlated with depressive and anxious symptoms controlling for T1 symptoms; (b) additional stressors

assessed at T1 and T2. Both insecure attachment dimen- (particularly interpersonal, as hypothesized in the inter-

sions correlated with more negative events (especially personal stress generation mechanism) are associated

interpersonal stressors). with emotional distress symptoms; and (c) the effect of

insecure attachment on emotional distress symptoms

SEM testing an interpersonal stress generation mechanism is reduced. In these models, we fit a more conservative

accounting for the association between attachment and emo- model in which both initial depressive and anxiety symp-

tional distress. According to the interpersonal stress gen- toms were included together (see Hankin, Roberts, &

eration hypothesis, insecure attachment will contribute Gotlib, 1997). The pattern of results was the same when

prospectively to a greater occurrence of negative events models were fit for one set of symptoms alone (e.g., anxi-

during the 2 years (especially interpersonal stressors), ety without controlling also for initial depression) as for

and these extra stressors, in turn, will lead to elevations both symptoms together, so we present findings for the

in emotional distress symptoms. As in Study 2 and consis- more parsimonious model controlling for both anxiety

tent with the steps for mediation according to Kenny and and depression symptoms.

colleagues (1998), we fit a series of SEMs that included Table 6 shows that the initial models for depressive

the paths from anxious attachment and avoidant attach- and anxiety composite symptoms both fit well. T1 anx-

ment to emotional distress symptoms at T1 and T2 (see ious attachment and T1 avoidant attachment predicted

Figure 3 for an illustration). We first fit a model to exam- T2 depressive symptoms even after controlling T1

ine the effects from T1 insecure attachment dimensions depression and anxiety symptoms. T2 anxiety symptoms

to both depressive and anxious symptoms at T2 while were predicted by T1 anxious attachment, but not

controlling for the effect of T1 symptoms. The next avoidant attachment, after controlling for T1 anxiety

model included the mediating effect of stressors (inter- and depression. For the second condition of mediation,

personal in one model, achievement in a second model) T1 insecure attachment dimensions predicted interper-

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Hankin et al. / ATTACHMENT AND EMOTIONAL DISTRESS 147

Anxiety

Attachment T1

Avoidant

Attachment T1

Interpersonal T2 Emotional

Negative Events T2 Distress Symptoms

Negative Events

T1

T1 Emotional

Distress

Symptoms

Figure 3 Depiction of an interpersonal stress generation mechanism involving interpersonal stressors as mediators of the association between

adult attachment dimensions and emotional distress symptoms (Study 3).

NOTE: Solid lines indicate direct paths, and dotted lines indicate indirect paths in the model. T = time interval.

TABLE 6: Structural Equation Modeling Results Examining an sonal stressors, but not achievement stressors. Thus, an

Interpersonal Stress Generation Mechanism as Mediator achievement stressors mediational pathway is not sup-

Between Attachment Dimensions and Emotional Distress

Symptoms in Study 3 (N = 233)

ported. Finally, the third condition of mediation was also

supported for both depressive and anxious symptoms.

β Interpersonal stressors predicted both T2 depressive

Coefficient

and anxious symptoms with the insecure attachment

Parameter Estimate χ2 df CFI RMSEA

dimensions included in the model. Consistent with par-

Model—Step 1 .11 2 1.0 0.0 tial mediation, T1 anxious attachment’s effect on T2

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 DEPRES .24*** depression (25%) and T2 anxiety (25%) was reduced,

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 DEPRES .13** but it remained as a significant predictor of both T2

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 ANX .20***

depressive and anxious symptoms with the inclusion of

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 ANX .09

Model—Step 2 .79 3 1.0 0.0 interpersonal stressors in the model. Consistent with

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 INT complete mediation, T1 avoidant attachment no longer

STRESS .30*** significantly predicted T2 depression (54% reduction)

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 INT with interpersonal stressors in the model.

STRESS .22***

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 ACH Discussion Study 3

STRESS .05

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 ACH Results from Study 3 replicated the basic findings

STRESS .09 from Studies 1 and 2 in that insecure attachment dimen-

Step 3

sions, assessed at T1, predicted prospective changes in

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 DEPRES .18***

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 DEPRES .08 depressive symptoms during the 2-year follow-up. Fur-

T1 ANXIOUS → T2 ANX .15** thermore, anxious attachment, but not avoidant attach-

T1 AVOIDANT → T2 ANX .06 ment, predicted prospective changes in anxiety symp-

toms. Advancing theory and evidence for attachment

NOTE: Only paths necessary for testing mediation are shown. ANX-

IOUS = anxious attachment style; AVOIDANT = avoidant attachment theory in a novel direction, Study 3 showed that an inter-

style; DEPRES = composite depressive symptoms; ANX = composite personal stress generation mediational pathway ex-

anxiety symptoms; INT STRESS = interpersonal stressors from T1 to plained the association between insecure attachment

T2; ACH STRESS = achievement stressors from T1 to T2; T1 = Time 1;

T2 = Time 2; CFI = Comparative Fit Index; RMSEA = root mean square and later depressive and anxiety symptoms. Insecure

error of approximation. attachment predicted prospective changes in interper-

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. sonal stressors, but not achievement stressors, experi-

Downloaded from http://psp.sagepub.com at UNIV DE CONCEPCION BIBLIOTECA on March 23, 2008

© 2005 Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc.. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

148 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY BULLETIN

enced during the 2-year follow-up, and interpersonal tial anxiety symptoms and attachment stability. Thus,

stressors in turn were associated with elevated levels of anxious attachment may only be a correlate of, rather

both depressive and anxious symptoms. This is consis- than a causal risk factor for, anxiety symptoms.

tent with attachment theory as a social, relational model Finding that insecure attachment predicts prospec-

and provides important discriminant predictive valid- tive elevations in depression and concurrent symptoms

ity for interpersonal versus achievement stressors being of anxiety is particularly important because researchers

generated by insecurely attached people. have suggested that one reason for the strong overlap of

depression and anxiety is that both forms of emotional

distress share common vulnerability factors (Hankin &

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Abramson, 2001; Mineka et al., 1998). It is important to

Several broad findings emerged from the current identify both (a) the risk factors that are specific to either

investigation. First, insecure attachment dimensions depression or anxiety and (b) the risk factors that are

consistently predicted prospective increases in depres- shared by both forms of emotional distress. Our results

sive symptoms across all three studies, and anxious suggest that anxious attachment is a nonspecific risk fac-

attachment was associated only concurrently with anx- tor for emotional distress and may help to account for

ious symptoms. Second, the relationship between inse- the high concurrent co-occurrence between depression

cure attachment dimensions and increases in depressive and anxiety.

symptoms was mediated by both dysfunctional attitudes

and low self-esteem. At the same time, the relationship Cognitive Risk Factors Pathway

between insecure attachment orientations and increases A cognitive risk factors pathway mediated the rela-

in anxious symptoms over time was not mediated by tionship between insecure attachment and increases

either of these cognitive variables. Last, the relationship in depressive symptoms consistent with past research

between insecure attachment and increases in both (Roberts et al., 1996). Results from Study 2 showed that

depressive and anxious symptoms was mediated by avoidant and anxious attachment dimensions were asso-