Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Read The Text Below and Discuss The Contrastive Linguistics As A Systematic Branch of Linguistic Science

Read The Text Below and Discuss The Contrastive Linguistics As A Systematic Branch of Linguistic Science

Uploaded by

fytoxoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Dark Days at Sunnyvale Can Teamwork Part The CloudsDocument3 pagesDark Days at Sunnyvale Can Teamwork Part The CloudsAssignmentLab.com100% (1)

- Tiểu luận Contrastive Linguistic - LinhDocument15 pagesTiểu luận Contrastive Linguistic - LinhThảo TuberoseNo ratings yet

- Certificacion Autocad PDFDocument2 pagesCertificacion Autocad PDFFranco Sarmiento Ahon0% (1)

- Research IIRMDS Q2 MODULE 2Document18 pagesResearch IIRMDS Q2 MODULE 2Gideon Enoch Tilan GarduñoNo ratings yet

- Methods of Lexicological AnalysisDocument12 pagesMethods of Lexicological AnalysisClaudia HoteaNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Word-Formation 1Document1 pageSeminar On Word-Formation 1fytoxoNo ratings yet

- Oral Communication Skills (English 1) : Summative Test Part 1Document4 pagesOral Communication Skills (English 1) : Summative Test Part 1Teacher Mo100% (1)

- Course Paper in Contrastive Lexicology and Phraseology of English and UkrainianDocument23 pagesCourse Paper in Contrastive Lexicology and Phraseology of English and UkrainianKariuk_Rostyslav100% (1)

- Contrastive AnalysisDocument12 pagesContrastive Analysisvomaiphuong100% (2)

- Lexicology 3 K. FabianDocument6 pagesLexicology 3 K. FabianDiana GNo ratings yet

- 34 Methods of Analysis 1Document26 pages34 Methods of Analysis 1Vito AsNo ratings yet

- Assignment On MorphologyDocument13 pagesAssignment On MorphologySahel Md Delabul Hossain100% (1)

- Modern English Lexicology. Its Aims and SignificanceDocument7 pagesModern English Lexicology. Its Aims and SignificanceAlsu SattarovaNo ratings yet

- Semantics and PragmaticsDocument39 pagesSemantics and PragmaticsAmyAideéGonzález100% (1)

- A Contrastive Study of Reflexive Verbs I F8be3286Document7 pagesA Contrastive Study of Reflexive Verbs I F8be3286samavril715No ratings yet

- Phonology Is The Level That Deals With Language Units and Phonetics Is The Level That Deals With Speech UnitsDocument31 pagesPhonology Is The Level That Deals With Language Units and Phonetics Is The Level That Deals With Speech UnitsДаша МусурівськаNo ratings yet

- 1-4 тестDocument15 pages1-4 тестДаша МусурівськаNo ratings yet

- Part 1 - LiDocument12 pagesPart 1 - LiFarah Farhana Pocoyo100% (1)

- Branches of LinguisticsDocument6 pagesBranches of LinguisticsMohammed RefaatNo ratings yet

- Small Glossary of LinguisticsDocument33 pagesSmall Glossary of LinguisticsKhalil AhmedNo ratings yet

- Methods and Procedures of Lexicological AnalysisDocument4 pagesMethods and Procedures of Lexicological AnalysisAlyona KalashnikovaNo ratings yet

- What Is Grammar - The Meanings of The Notion of GrammarDocument4 pagesWhat Is Grammar - The Meanings of The Notion of GrammarCarmina EchaviaNo ratings yet

- Ministery of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Babylon College of Education For Human Sciences Department of EnglishDocument10 pagesMinistery of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Babylon College of Education For Human Sciences Department of EnglishOla AlduliamyNo ratings yet

- Ling 1 Module Number 1Document10 pagesLing 1 Module Number 1Jean Claude CagasNo ratings yet

- Some Basic Concepts in Linguistics: P. B. AllenDocument28 pagesSome Basic Concepts in Linguistics: P. B. AllenLau MaffeisNo ratings yet

- Analyzing EnglishDocument70 pagesAnalyzing EnglishToàn DươngNo ratings yet

- Language Is Primarily An Auditory System of SymbolsDocument6 pagesLanguage Is Primarily An Auditory System of SymbolsDomingos Tolentino Saide DtsNo ratings yet

- Kevin Handy: Answered May 30, 2018Document3 pagesKevin Handy: Answered May 30, 2018Francklin Nim'sNo ratings yet

- 1st and 2ndDocument5 pages1st and 2ndmosab77No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument8 pagesUntitledMilagros SalinasNo ratings yet

- Идиомы в английском языкеDocument11 pagesИдиомы в английском языкеrsarsarsarsa2006No ratings yet

- Nida Translation TheoryDocument4 pagesNida Translation TheoryNalin HettiarachchiNo ratings yet

- თეა ვერძაძის პროექტიDocument15 pagesთეა ვერძაძის პროექტილელა ვერბიNo ratings yet

- Essay - Parts of SpeechDocument15 pagesEssay - Parts of Speechsyed hyder ALI100% (2)

- Miram Basic TranslDocument54 pagesMiram Basic TranslVladimir NekrasovNo ratings yet

- WordSegmentationFL PDFDocument50 pagesWordSegmentationFL PDFCarlosSorianoNo ratings yet

- Name: Sabarni R Sipayung NPM: 1801030213 Quiz Contrastive AnalysisDocument4 pagesName: Sabarni R Sipayung NPM: 1801030213 Quiz Contrastive AnalysisSabarni R Sipayung 213No ratings yet

- Language Forms and Functions - Ebook Chapter 1Document49 pagesLanguage Forms and Functions - Ebook Chapter 1Harry ChicaNo ratings yet

- STYLISTICS: Related Discipline: Phonology - Is The Study of The Patterns of Sounds in A Language and Across LanguagesDocument6 pagesSTYLISTICS: Related Discipline: Phonology - Is The Study of The Patterns of Sounds in A Language and Across LanguagesaninO9No ratings yet

- Navigation Search Morphology List of References External LinksDocument12 pagesNavigation Search Morphology List of References External Links-aKu Ucoep Coep-No ratings yet

- LING 1ere Année Cours12 12Document4 pagesLING 1ere Année Cours12 12mohamedlmn1993No ratings yet

- Word Segment at I OnDocument34 pagesWord Segment at I OnxparetoNo ratings yet

- Modern English GrammarDocument287 pagesModern English GrammarAnonymous SR0AF3100% (4)

- SAJULGA Universal GrammarDocument3 pagesSAJULGA Universal GrammarJOYANo ratings yet

- MartinHaspelmath For DiscussionDocument15 pagesMartinHaspelmath For DiscussionPaulinho KambutaNo ratings yet

- The Structure of Language': David CrystalDocument7 pagesThe Structure of Language': David CrystalPetr ŠkaroupkaNo ratings yet

- Linguistic GlossaryDocument36 pagesLinguistic GlossaryGood OneNo ratings yet

- UE-13 (M) Maria MykhalchakDocument13 pagesUE-13 (M) Maria MykhalchakMariaNo ratings yet

- SociolinguisticsDocument39 pagesSociolinguisticsArif Efendi100% (1)

- Task 1 ElDocument5 pagesTask 1 ElNining SagitaNo ratings yet

- Okoro - NigE UsageDocument37 pagesOkoro - NigE UsageOjoblessing081No ratings yet

- Small Glossary of LinguisticsDocument24 pagesSmall Glossary of LinguisticsPatricia VillafrancaNo ratings yet

- Introduction to LinguisticsDocument4 pagesIntroduction to Linguisticsvincentpangan1988No ratings yet

- Binder 1Document38 pagesBinder 1Danijela VukovićNo ratings yet

- Makalah LinguisticDocument8 pagesMakalah Linguisticandiksetiobudi100% (3)

- Morphology PresentationDocument11 pagesMorphology PresentationMajda NizamicNo ratings yet

- What Is LanguageDocument12 pagesWhat Is Languageeimy ruiz hidalgoNo ratings yet

- English LexicologyDocument196 pagesEnglish Lexicologynata100% (1)

- Introduction. Fundamentals. A Word As The Basic Unit of The LanguageDocument7 pagesIntroduction. Fundamentals. A Word As The Basic Unit of The LanguageЛіза ФедороваNo ratings yet

- Branches of LinguisticsDocument5 pagesBranches of LinguisticsDahlia DomingoNo ratings yet

- First Language Acquisition and TeachingDocument12 pagesFirst Language Acquisition and Teachingfrenqui MussaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Phrasal VerbsDocument6 pagesChapter 1 Phrasal VerbsAnna ManukyanNo ratings yet

- SUMMARYDocument7 pagesSUMMARYLuis J. MartinezNo ratings yet

- Main Characteristic Features-1) Structural 2) Semantic 3) FunctionalDocument1 pageMain Characteristic Features-1) Structural 2) Semantic 3) FunctionalfytoxoNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Word-Formation 2Document1 pageSeminar On Word-Formation 2fytoxoNo ratings yet

- TranslatorDocument4 pagesTranslatorfytoxoNo ratings yet

- Chelsea Zappel's ResumeDocument2 pagesChelsea Zappel's ResumeChelsea ZappelNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument19 pagesLesson Planapi-451036143No ratings yet

- Reading SkillsDocument4 pagesReading SkillsAmina Ait SaiNo ratings yet

- Online Discussion Forum and NetiquittesDocument16 pagesOnline Discussion Forum and NetiquittesSameen RahatNo ratings yet

- Mini Project ON Driver Drowsiness Detection and Safety Alert System Using PythonDocument29 pagesMini Project ON Driver Drowsiness Detection and Safety Alert System Using PythonTaruni YenumulaNo ratings yet

- Format of PG (M.Tech.) ResumeDocument3 pagesFormat of PG (M.Tech.) ResumeTrushti SanghviNo ratings yet

- 8 Galilei Nathalie Joy G. Marticio 29 21 50 1 0 1 Mendeleev Rhaian M. Corpuz Rutheford Honorio G. Siso Jr. Aristotle Rona J. MoselinaDocument4 pages8 Galilei Nathalie Joy G. Marticio 29 21 50 1 0 1 Mendeleev Rhaian M. Corpuz Rutheford Honorio G. Siso Jr. Aristotle Rona J. MoselinaNhatz Gallosa MarticioNo ratings yet

- Edumate Educational Hub: ScienceDocument2 pagesEdumate Educational Hub: SciencekhanuniskyNo ratings yet

- Laws and Guidelines That Govern Architectural Practice in The PhilippinesDocument13 pagesLaws and Guidelines That Govern Architectural Practice in The PhilippinesJehan MohamadNo ratings yet

- Unit 10 Extra Grammar ExercisesDocument2 pagesUnit 10 Extra Grammar ExercisesHugo A FE22% (9)

- Java Lab ManualDocument53 pagesJava Lab ManualAlaa TelpNo ratings yet

- Course Guide: ME463 - Machine Design 2Document4 pagesCourse Guide: ME463 - Machine Design 2Christian Breth BurgosNo ratings yet

- Mysticism and Meaning MultidisciplinaryDocument326 pagesMysticism and Meaning MultidisciplinaryWiedzminNo ratings yet

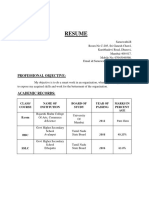

- Resume: Professional ObjectiveDocument3 pagesResume: Professional Objectivevinayak tiwariNo ratings yet

- Coursera VGFWHMFAAMZEDocument1 pageCoursera VGFWHMFAAMZEJdohndlfjbdNo ratings yet

- RPT Math DLP Year 3 2022-2023 by Rozayus AcademyDocument21 pagesRPT Math DLP Year 3 2022-2023 by Rozayus AcademyrphsekolahrendahNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Tg-Grade 8 MathematicsDocument62 pagesModule 1 Tg-Grade 8 MathematicsGary Nugas77% (30)

- Project Charter Template.2019Document10 pagesProject Charter Template.2019沈悦双No ratings yet

- Personal Reward101Document15 pagesPersonal Reward101karunaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Curriculum DevelopmentDocument19 pagesCurriculum Curriculum DevelopmentJeenagg Narayan50% (2)

- Homeroom Guidance: Quarter 4Document15 pagesHomeroom Guidance: Quarter 4AYSA GENEVIERE O.LAPUZ100% (1)

- 2013 KGSP Graduate Program Guideline (Dongguk)Document11 pages2013 KGSP Graduate Program Guideline (Dongguk)Astho RanieNo ratings yet

- Format Sip PDFDocument5 pagesFormat Sip PDFchander mauli tripathiNo ratings yet

- 2004-2005 Annual ReportDocument40 pages2004-2005 Annual ReportInggar PradiptaNo ratings yet

- Applying For Visitor Visa (Temporary Resident Visa - IMM 5256)Document20 pagesApplying For Visitor Visa (Temporary Resident Visa - IMM 5256)Metha DawnNo ratings yet

- Tillis CVDocument14 pagesTillis CVThe State NewsNo ratings yet

Read The Text Below and Discuss The Contrastive Linguistics As A Systematic Branch of Linguistic Science

Read The Text Below and Discuss The Contrastive Linguistics As A Systematic Branch of Linguistic Science

Uploaded by

fytoxoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Read The Text Below and Discuss The Contrastive Linguistics As A Systematic Branch of Linguistic Science

Read The Text Below and Discuss The Contrastive Linguistics As A Systematic Branch of Linguistic Science

Uploaded by

fytoxoCopyright:

Available Formats

Practical class 1.

1. Read the text below and discuss the contrastive linguistics as a systematic

branch of linguistic science.

Contrastive Linguistics as a systematic branch of linguistic science is of fairly recent

date, though it is not the idea which is new, but rather the systematization and the

underlying principles. It is common knowledge that comparison is the basic principle in

Comparative Philology. However, the aims and methods of Comparative Philology differ

considerably from those of Contrastive Linguistics. The comparativist compares languages

in order to trace their philogenic relationships. The material he draws for comparison

consists mainly of individual sounds, sound combinations and words, the aim is to establish

family relationship. The term used to describe this field of investigation is Historical

Comparative Linguistics.

Comparison is also applied in typological classification and analysis. This comparison

classifies languages by types rather than origins and relationships. One of the purposes of

typological comparison is to arrive at language universals — those elements and processes

which, despite their surface diversity, are common to all languages.

Contrastive Linguistics attempts to find out similarities and differences in both

philogenically related and non-related languages at the present stage of development. It is

now universally recognized that Contrastive Linguistics is a field of particular interest to

translators and teachers of foreign languages.

In fact, the contrastive analysis grew as a result of practical demands of language

teaching methodology where it was empirically shown that errors which are made

recurrently by foreign language students can be often traced back to the differences in the

structure of the target language and the learner's mother tongue.

It is common knowledge that one of the major problems in learning a foreign language

is the interference caused by the difference between the learner’s mother tongue and the

target language. The contrastive analysis has a part to play in evaluation of errors, in

predicting typical errors and thus must be seen in connection with overall endeavours to

rationalize and intensify foreign language teaching.

Linguistic scholars working in the field of Applied Linguistics assume that the most

effective teaching materials are those that are based upon a scientific description of the

target language carefully compared with a parallel description of the native language of the

learner. They proceed from the assumption that the categories, elements, etc. on the

semantic as well as on the syntactic and other levels are valid for both languages, i.e. are

adopted from a universal inventory. For example, linking verbs can be found in English,

French, Ukrainian, etc. Linking verbs having the meaning "change, become" are differently

represented in each of the languages. In English, e.g., become, come, fall, get, grow, run,

turn, wax, in German — werden, in French — devenir, in Ukrainian — cmaвamu.

The task set before the linguist is to find out which semantic and syntactic features

characterize:

1) the English set of verbs (cf.: grow thin, get angry, fall ill, turn traitor, run dry, wax

eloquent);

2) the French (Ukrainian, German, etc.) set of verbs;

3) how the sets compare: e.g., the English word-groups grow thin, get angry, fall ill and the

Ukrainian verbs cxyднymu, poзcepдumucя, зaxвopimu.

The contrastive analysis can be carried out at three linguistic levels: phonology,

grammar (morphology and syntax) and lexis (vocabulary).

On the level of lexis the contrastive analysis is applied to reveal the features of

sameness and difference in lexical meanings and semantic structures of correlated words in

different languages.

It is commonly assumed by non-linguists that all languages have rocabulary systems

in which words themselves differ in sound-form but refer to reality in the same way. From

this assumption it follows that for every word in the mother tongue there is an exact

equivalent in the foreign language. It is a belief which is reinforced by small bilingual

dictionaries where single word translations are often offered. Language learning, however,

cannot be just a matter of learning to substitute a new set of labels for the familiar ones of

the mother tongue.

It should be borne in mind that, though the objective reality exists outside human

beings and irrespective of the language they speak, every language classifies this reality in

its own way by means of vocabulary units. In English, e.g., the word foot is used to denote

the extremity of the leg. In Ukrainian there is no exact equivalent for foot. The word нога

denotes the whole leg including the foot.

Classification of the real world around us provided by vocabulary units of our mother

tongue is Jeamed and assimilated together with our native language. Because we are used to

the way in which our own language structures experience, we are often inclined to think of

this as the only natural way of handling things, whereas, in fact, it is highly arbitrary. One

example is provided by the words watch and clock. It would seem natural for Ukrainian

speakers to have a single word to refer to all devices that tell us what time it is; yet in

English they are divided into two semantic classes depending on whether or not they are

customarily portable. We also find it natural that kinship terms should reflect the difference

between male and female: brother or sister, father or mother, uncle or aunt, etc. Yet in

English we fail to make this distinction in the case of cousin (e.g.: Ukr. — двоюрідний

6pam, двоюрідна cecmpa).

The contrastive analysis also brings to light what can be labelled as problem pairs,

i.e. the words that denote two entities in one language and correspond to two different words

in another language. Compare, for example, годинник in Ukrainian and clock, watch in

English, xyдожник in Ukrainian and artist, painter in English.

Each language contains words which cannot be translated directly from this language

into another. For instance, favourite examples of untranslatable German words are

gemutlich (something like 'easy-going', 'humbly pleasant', 'informal') and Schadenfreude

('pleasure over the fact that someone else has suffered a misfortune'). Traditional examples

of untranslatable English words are sophisticated and efficient. '

This is not to say that the lack of word-for-word equivalents implies also the lack of

what is denoted by these words. If this were true, we should have to conclude that speakers

of English never indulge in Schadenfreude, that there are no sophisticated Germans or there

is no efficient industry in any country outside GB or the USA.

If we abandon the primitive notion of word-for-word equivalence, we can safely

assume, firstly, that anything which can be said in one language can be translated more or

less accurately into another; secondly, that correlated polysemantic words of different

languages are not, as a rule, co-extensive. Polysemantic words in all languages may denote

very different types of objects and, yet, all the meanings are considered by the native

speakers to be obviously logical extensions of the basic meaning. For example, to an

English-speaking person it is self-evident that one should be able to use the word head to

denote the following:

head of a person head of a match head of a bed

head of a table head of a coin head of a cane

head of an organisation

The very real danger for the Ukrainian language learner here is that (having

learned first that head is the English word which denotes a part of the body) he will

assume that it can be used in all the cases where the Ukrainian word голова is used

in Ukrainian, e.g., голова цукру ('a loaf of sugar'), міський голова ('mayor of the

city'), він хлопець з головою ('he is a bright lad'), nopuнamu в щось з головою ('to

throw oneself into smth.'), etc., but will never think of using the word head in

connection with 'a bed' or 'a coin'. Thirdly, the meaning of any word depends, to a

great extent, on the place it occupies in the set of semantically related words: its

synonyms, constituents of the lexical field the word belongs to, other members of

the word-family which the word enters, etc.

2. Answer the following questions:

What is lexicology as a separate branch of linguistics concerned with?

What are the subdivisions of lexicology?

Specify the difference between historical lexicology and etymology.

What is the theoretical and practical value of contrastive lexicology?

Speak on the connection of lexicology and

– Phonology

– Grammar

– Semasiology

– Pragmatics

– Stylistics

– Psycholinguistics

– Sociolinguistics

– Studies of speech varieties

You might also like

- Dark Days at Sunnyvale Can Teamwork Part The CloudsDocument3 pagesDark Days at Sunnyvale Can Teamwork Part The CloudsAssignmentLab.com100% (1)

- Tiểu luận Contrastive Linguistic - LinhDocument15 pagesTiểu luận Contrastive Linguistic - LinhThảo TuberoseNo ratings yet

- Certificacion Autocad PDFDocument2 pagesCertificacion Autocad PDFFranco Sarmiento Ahon0% (1)

- Research IIRMDS Q2 MODULE 2Document18 pagesResearch IIRMDS Q2 MODULE 2Gideon Enoch Tilan GarduñoNo ratings yet

- Methods of Lexicological AnalysisDocument12 pagesMethods of Lexicological AnalysisClaudia HoteaNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Word-Formation 1Document1 pageSeminar On Word-Formation 1fytoxoNo ratings yet

- Oral Communication Skills (English 1) : Summative Test Part 1Document4 pagesOral Communication Skills (English 1) : Summative Test Part 1Teacher Mo100% (1)

- Course Paper in Contrastive Lexicology and Phraseology of English and UkrainianDocument23 pagesCourse Paper in Contrastive Lexicology and Phraseology of English and UkrainianKariuk_Rostyslav100% (1)

- Contrastive AnalysisDocument12 pagesContrastive Analysisvomaiphuong100% (2)

- Lexicology 3 K. FabianDocument6 pagesLexicology 3 K. FabianDiana GNo ratings yet

- 34 Methods of Analysis 1Document26 pages34 Methods of Analysis 1Vito AsNo ratings yet

- Assignment On MorphologyDocument13 pagesAssignment On MorphologySahel Md Delabul Hossain100% (1)

- Modern English Lexicology. Its Aims and SignificanceDocument7 pagesModern English Lexicology. Its Aims and SignificanceAlsu SattarovaNo ratings yet

- Semantics and PragmaticsDocument39 pagesSemantics and PragmaticsAmyAideéGonzález100% (1)

- A Contrastive Study of Reflexive Verbs I F8be3286Document7 pagesA Contrastive Study of Reflexive Verbs I F8be3286samavril715No ratings yet

- Phonology Is The Level That Deals With Language Units and Phonetics Is The Level That Deals With Speech UnitsDocument31 pagesPhonology Is The Level That Deals With Language Units and Phonetics Is The Level That Deals With Speech UnitsДаша МусурівськаNo ratings yet

- 1-4 тестDocument15 pages1-4 тестДаша МусурівськаNo ratings yet

- Part 1 - LiDocument12 pagesPart 1 - LiFarah Farhana Pocoyo100% (1)

- Branches of LinguisticsDocument6 pagesBranches of LinguisticsMohammed RefaatNo ratings yet

- Small Glossary of LinguisticsDocument33 pagesSmall Glossary of LinguisticsKhalil AhmedNo ratings yet

- Methods and Procedures of Lexicological AnalysisDocument4 pagesMethods and Procedures of Lexicological AnalysisAlyona KalashnikovaNo ratings yet

- What Is Grammar - The Meanings of The Notion of GrammarDocument4 pagesWhat Is Grammar - The Meanings of The Notion of GrammarCarmina EchaviaNo ratings yet

- Ministery of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Babylon College of Education For Human Sciences Department of EnglishDocument10 pagesMinistery of Higher Education and Scientific Research University of Babylon College of Education For Human Sciences Department of EnglishOla AlduliamyNo ratings yet

- Ling 1 Module Number 1Document10 pagesLing 1 Module Number 1Jean Claude CagasNo ratings yet

- Some Basic Concepts in Linguistics: P. B. AllenDocument28 pagesSome Basic Concepts in Linguistics: P. B. AllenLau MaffeisNo ratings yet

- Analyzing EnglishDocument70 pagesAnalyzing EnglishToàn DươngNo ratings yet

- Language Is Primarily An Auditory System of SymbolsDocument6 pagesLanguage Is Primarily An Auditory System of SymbolsDomingos Tolentino Saide DtsNo ratings yet

- Kevin Handy: Answered May 30, 2018Document3 pagesKevin Handy: Answered May 30, 2018Francklin Nim'sNo ratings yet

- 1st and 2ndDocument5 pages1st and 2ndmosab77No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument8 pagesUntitledMilagros SalinasNo ratings yet

- Идиомы в английском языкеDocument11 pagesИдиомы в английском языкеrsarsarsarsa2006No ratings yet

- Nida Translation TheoryDocument4 pagesNida Translation TheoryNalin HettiarachchiNo ratings yet

- თეა ვერძაძის პროექტიDocument15 pagesთეა ვერძაძის პროექტილელა ვერბიNo ratings yet

- Essay - Parts of SpeechDocument15 pagesEssay - Parts of Speechsyed hyder ALI100% (2)

- Miram Basic TranslDocument54 pagesMiram Basic TranslVladimir NekrasovNo ratings yet

- WordSegmentationFL PDFDocument50 pagesWordSegmentationFL PDFCarlosSorianoNo ratings yet

- Name: Sabarni R Sipayung NPM: 1801030213 Quiz Contrastive AnalysisDocument4 pagesName: Sabarni R Sipayung NPM: 1801030213 Quiz Contrastive AnalysisSabarni R Sipayung 213No ratings yet

- Language Forms and Functions - Ebook Chapter 1Document49 pagesLanguage Forms and Functions - Ebook Chapter 1Harry ChicaNo ratings yet

- STYLISTICS: Related Discipline: Phonology - Is The Study of The Patterns of Sounds in A Language and Across LanguagesDocument6 pagesSTYLISTICS: Related Discipline: Phonology - Is The Study of The Patterns of Sounds in A Language and Across LanguagesaninO9No ratings yet

- Navigation Search Morphology List of References External LinksDocument12 pagesNavigation Search Morphology List of References External Links-aKu Ucoep Coep-No ratings yet

- LING 1ere Année Cours12 12Document4 pagesLING 1ere Année Cours12 12mohamedlmn1993No ratings yet

- Word Segment at I OnDocument34 pagesWord Segment at I OnxparetoNo ratings yet

- Modern English GrammarDocument287 pagesModern English GrammarAnonymous SR0AF3100% (4)

- SAJULGA Universal GrammarDocument3 pagesSAJULGA Universal GrammarJOYANo ratings yet

- MartinHaspelmath For DiscussionDocument15 pagesMartinHaspelmath For DiscussionPaulinho KambutaNo ratings yet

- The Structure of Language': David CrystalDocument7 pagesThe Structure of Language': David CrystalPetr ŠkaroupkaNo ratings yet

- Linguistic GlossaryDocument36 pagesLinguistic GlossaryGood OneNo ratings yet

- UE-13 (M) Maria MykhalchakDocument13 pagesUE-13 (M) Maria MykhalchakMariaNo ratings yet

- SociolinguisticsDocument39 pagesSociolinguisticsArif Efendi100% (1)

- Task 1 ElDocument5 pagesTask 1 ElNining SagitaNo ratings yet

- Okoro - NigE UsageDocument37 pagesOkoro - NigE UsageOjoblessing081No ratings yet

- Small Glossary of LinguisticsDocument24 pagesSmall Glossary of LinguisticsPatricia VillafrancaNo ratings yet

- Introduction to LinguisticsDocument4 pagesIntroduction to Linguisticsvincentpangan1988No ratings yet

- Binder 1Document38 pagesBinder 1Danijela VukovićNo ratings yet

- Makalah LinguisticDocument8 pagesMakalah Linguisticandiksetiobudi100% (3)

- Morphology PresentationDocument11 pagesMorphology PresentationMajda NizamicNo ratings yet

- What Is LanguageDocument12 pagesWhat Is Languageeimy ruiz hidalgoNo ratings yet

- English LexicologyDocument196 pagesEnglish Lexicologynata100% (1)

- Introduction. Fundamentals. A Word As The Basic Unit of The LanguageDocument7 pagesIntroduction. Fundamentals. A Word As The Basic Unit of The LanguageЛіза ФедороваNo ratings yet

- Branches of LinguisticsDocument5 pagesBranches of LinguisticsDahlia DomingoNo ratings yet

- First Language Acquisition and TeachingDocument12 pagesFirst Language Acquisition and Teachingfrenqui MussaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Phrasal VerbsDocument6 pagesChapter 1 Phrasal VerbsAnna ManukyanNo ratings yet

- SUMMARYDocument7 pagesSUMMARYLuis J. MartinezNo ratings yet

- Main Characteristic Features-1) Structural 2) Semantic 3) FunctionalDocument1 pageMain Characteristic Features-1) Structural 2) Semantic 3) FunctionalfytoxoNo ratings yet

- Seminar On Word-Formation 2Document1 pageSeminar On Word-Formation 2fytoxoNo ratings yet

- TranslatorDocument4 pagesTranslatorfytoxoNo ratings yet

- Chelsea Zappel's ResumeDocument2 pagesChelsea Zappel's ResumeChelsea ZappelNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument19 pagesLesson Planapi-451036143No ratings yet

- Reading SkillsDocument4 pagesReading SkillsAmina Ait SaiNo ratings yet

- Online Discussion Forum and NetiquittesDocument16 pagesOnline Discussion Forum and NetiquittesSameen RahatNo ratings yet

- Mini Project ON Driver Drowsiness Detection and Safety Alert System Using PythonDocument29 pagesMini Project ON Driver Drowsiness Detection and Safety Alert System Using PythonTaruni YenumulaNo ratings yet

- Format of PG (M.Tech.) ResumeDocument3 pagesFormat of PG (M.Tech.) ResumeTrushti SanghviNo ratings yet

- 8 Galilei Nathalie Joy G. Marticio 29 21 50 1 0 1 Mendeleev Rhaian M. Corpuz Rutheford Honorio G. Siso Jr. Aristotle Rona J. MoselinaDocument4 pages8 Galilei Nathalie Joy G. Marticio 29 21 50 1 0 1 Mendeleev Rhaian M. Corpuz Rutheford Honorio G. Siso Jr. Aristotle Rona J. MoselinaNhatz Gallosa MarticioNo ratings yet

- Edumate Educational Hub: ScienceDocument2 pagesEdumate Educational Hub: SciencekhanuniskyNo ratings yet

- Laws and Guidelines That Govern Architectural Practice in The PhilippinesDocument13 pagesLaws and Guidelines That Govern Architectural Practice in The PhilippinesJehan MohamadNo ratings yet

- Unit 10 Extra Grammar ExercisesDocument2 pagesUnit 10 Extra Grammar ExercisesHugo A FE22% (9)

- Java Lab ManualDocument53 pagesJava Lab ManualAlaa TelpNo ratings yet

- Course Guide: ME463 - Machine Design 2Document4 pagesCourse Guide: ME463 - Machine Design 2Christian Breth BurgosNo ratings yet

- Mysticism and Meaning MultidisciplinaryDocument326 pagesMysticism and Meaning MultidisciplinaryWiedzminNo ratings yet

- Resume: Professional ObjectiveDocument3 pagesResume: Professional Objectivevinayak tiwariNo ratings yet

- Coursera VGFWHMFAAMZEDocument1 pageCoursera VGFWHMFAAMZEJdohndlfjbdNo ratings yet

- RPT Math DLP Year 3 2022-2023 by Rozayus AcademyDocument21 pagesRPT Math DLP Year 3 2022-2023 by Rozayus AcademyrphsekolahrendahNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Tg-Grade 8 MathematicsDocument62 pagesModule 1 Tg-Grade 8 MathematicsGary Nugas77% (30)

- Project Charter Template.2019Document10 pagesProject Charter Template.2019沈悦双No ratings yet

- Personal Reward101Document15 pagesPersonal Reward101karunaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Curriculum DevelopmentDocument19 pagesCurriculum Curriculum DevelopmentJeenagg Narayan50% (2)

- Homeroom Guidance: Quarter 4Document15 pagesHomeroom Guidance: Quarter 4AYSA GENEVIERE O.LAPUZ100% (1)

- 2013 KGSP Graduate Program Guideline (Dongguk)Document11 pages2013 KGSP Graduate Program Guideline (Dongguk)Astho RanieNo ratings yet

- Format Sip PDFDocument5 pagesFormat Sip PDFchander mauli tripathiNo ratings yet

- 2004-2005 Annual ReportDocument40 pages2004-2005 Annual ReportInggar PradiptaNo ratings yet

- Applying For Visitor Visa (Temporary Resident Visa - IMM 5256)Document20 pagesApplying For Visitor Visa (Temporary Resident Visa - IMM 5256)Metha DawnNo ratings yet

- Tillis CVDocument14 pagesTillis CVThe State NewsNo ratings yet