Professional Documents

Culture Documents

American Indian Case

American Indian Case

Uploaded by

Min Kyu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

39 views9 pagesThe Havasupai Tribe filed a lawsuit against Arizona State University researchers for misusing DNA samples collected under the guise of diabetes research. Samples were used for unrelated studies on topics taboo to the tribe like schizophrenia and migration without consent. This violated informed consent and trust. The tribe received a $700,000 settlement but no legal precedent was set. The case highlighted issues like lack of specific informed consent, risks of stigmatization, and unauthorized access to medical records in genetic research with indigenous communities.

Original Description:

Original Title

American Indian Case.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe Havasupai Tribe filed a lawsuit against Arizona State University researchers for misusing DNA samples collected under the guise of diabetes research. Samples were used for unrelated studies on topics taboo to the tribe like schizophrenia and migration without consent. This violated informed consent and trust. The tribe received a $700,000 settlement but no legal precedent was set. The case highlighted issues like lack of specific informed consent, risks of stigmatization, and unauthorized access to medical records in genetic research with indigenous communities.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

39 views9 pagesAmerican Indian Case

American Indian Case

Uploaded by

Min KyuThe Havasupai Tribe filed a lawsuit against Arizona State University researchers for misusing DNA samples collected under the guise of diabetes research. Samples were used for unrelated studies on topics taboo to the tribe like schizophrenia and migration without consent. This violated informed consent and trust. The tribe received a $700,000 settlement but no legal precedent was set. The case highlighted issues like lack of specific informed consent, risks of stigmatization, and unauthorized access to medical records in genetic research with indigenous communities.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 9

For Tribes For Researchers About Us

Contact Us Index

search

156

Havasupai Tribe and the lawsuit settlement

aftermath

In 1989, researchers from Arizona State University (ASU)

embarked on a research partnership called the Diabetes

Project with the Havasupai Tribe, a community with high

rates of Type II Diabetes living in a remote part of the Grand

Canyon. The Diabetes Project with the Havasupai included

health education, collecting and testing of blood samples,

and genetic association testing to search for links between

genes and diabetes risk. After several years of trying, the

researchers were not successful in finding a genetic link to

Type II Diabetes. They then used the blood samples

containing DNA for other unrelated studies such as studies

on schizophrenia, migration, and inbreeding, all of which are

taboo topics for the Havasupai. Carletta Tilousi, a member

of the Havasupai tribe and a participant in the Diabetes

Project, attended a lecture at ASU in March 2003 where she

learned the samples were used for the later studies without

her consent or the consent of other tribal members (Rubin

2004).

In 2004, the Havasupai Tribe filed a lawsuit against Arizona

Board of Regents and ASU researchers for misuse of their

DNA samples (Havasupai Tribe of the Havasupai

Reservation v. Arizona Board of Regents and Therese Ann

Markow 2004). The lawsuit articulated concerns about

lack of informed consent, violation of civil rights through

mishandling of blood samples, unapproved use of data, and

violation of medical confidentiality. The initial case

complaints also listed misrepresentation, infliction of

emotional distress, conversion, violation of civil rights, and

negligence, but it was ultimately dismissed due to a

procedural error.

The Arizona Court of Appeals later reinstated the lawsuit,

leading to a lengthy legal battle. Eventually, the Arizona

Board of Regents v. Havasupai Tribe case reached a

settlement in April 2010 in which tribal members received

$700,000 for compensation, funds for a clinic and school,

and return of DNA samples (Harmon 2010; Mello and Wolf

2010). Because the lawsuit ended in an out-of-court

settlement, there is no legal precedent emerging from this

case over how informed consent issues in research should

be handled. Tribes could benefit from becoming informed

of the issues that arose in the case and develop safeguards

to prevent similar issues from arising in future studies.

Issues raised in the Havasupai lawsuit

Informed consent: Using samples without complete

informed consent and without permission from tribal

members was a major concern in the Havasupai lawsuit.

Informed consent was obtained by making oral statements

to the tribal members to recruit them to the research study,

and then they were given informed consent documents to

sign. All tribal members who gave blood were told that the

samples would be used for genetic studies on diabetes.

Although the consent forms mention that the samples would

be used for research on “behavioral and medical disorders,”

no Havasupai members were told this would include studies

on schizophrenia (Hart 2003). Use of broad language in

consent forms should be considered carefully. Advances in

genetic research happen all the time, so it can be hard for a

researcher to predict all the possible types of research that

can be done with a sample. Other informed consent forms

have created very specific language that allows researchers

to use the samples for particular types of studies.

Human Migration studies: In genetic research, migration

studies use genetic markers in people to look at how people

are related to their distant relatives. The studies trace

genetic markers back in time by comparing many people

from different tribes, communities, and parts of the world.

Scientists study these genetic markers by using statistics

and make calculations using models in order to predict how

closely related two or more tribes are to each other. These

models take genetic information from tribes and

communities that exist today, and then scientists compare

them with each other to predict how long ago distant

relatives were more closely related.

Imagine a case in which one modern-day tribe is able to

trace its history to being a part of another modern-day

tribe. For one reason or another, some people left that

other tribe to migrate, or move away, and live as a separate

people. Over time, the small group of people that left grew

larger, the language began to change, and this group of

people became their own distinct tribe. In fact, some tribes

do have old stories in their tribal history about a great

migration or about branching away from another group a

very long time ago. However, different tribal members

might interpret these stories differently, so it is important to

think carefully about how tribal migration stories or origin

stories might fit in with genetic migration studies, and

whether tribal members might be opposed to genetic

migration studies.

Scientists who study migration patterns will take genetic

information from dozens or even hundreds of different tribes

to look at how all these modern-day tribes are related. In

many cases, scientists use genetic information from people

in Mongolia and other parts of Asia to support the Bering

Strait theory that ancestors of modern-day Native

Americans came across the Bering Strait.

Languages can also be studied to look at possible

relationships between groups. For example, fluent Navajo

speakers can understand a lot of the Apache language.

Spanish speakers can understand a lot of the Portuguese

language. The Navajo and Apache languages are related,

and so are the Spanish and Portuguese languages. If you

go back far enough in time, you can say that these two

distinct groups of people used to live together and spoke

the same language at one time, but at some point the two

groups separated and the languages began to change and

became different from each other.

Scientists have already gathered a lot of information using

linguistics (from comparing different languages),

anthropology (such as cultural practices and cultural

beliefs), and archaeology (from bones, pottery, arrowheads,

and other ancient remains). Sometimes, scientists also use

genetic information to support theories and ideas of how

two distant groups might be related.

Migration studies are a concern for many tribes because the

scientific evidence for tribal origins may go against cultural

beliefs on tribal origins or be taken as true. Tribes who are

considering involvement in migration or ancestry studies

should think carefully about the implications this work

would have on their tribes and other related tribes. For

example, if a migration study suggests that a tribe originally

came across the Bering Strait from Asia, the results of the

study might have political implications and challenge tribal

sovereignty and land rights. Similarly, if a tribe is

genetically related to other nearby tribes, involvement in

research could affect those related tribes. In these ways,

nearby or related tribes might be affected by the actions of

one tribe who decides to participate in genetic research.

To address these potential concerns, it might be important

for tribes to communicate with each other to come to an

understanding or agreement about what types of genetic

research might be acceptable (such as understanding a

disease in the community) or not as acceptable (such as

research that may support negative stereotypes or that

might suggest a tribe is not “Native” to the U.S.).

Stigmatization: Stigmatization of the tribe was also a risk to

the Havasupai community, especially with the concern of

“inbreeding.” Scientists used a statistical measurement

called the “inbreeding coefficient” to estimate how similar

individuals within a population are to each other genetically

(Markow and Martin 1993). The “inbreeding coefficient” is

high if a community is small and isolated with few outsiders

coming into the community. On the other hand, the

“inbreeding coefficient” is low when the community is large

and in an area where there is a lot of outsiders who come

into the community and intermarry. For the Havasupai, the

“inbreeding coefficient” was high compared to other tribes.

The way in which this information was conveyed to the

Havasupai may have been insensitive, because it was

interpreted as tribal members who “inbreed” with each

other. That is not the case at all. For the Havasupai and

for many other tribes, inbreeding is a taboo and people who

break that taboo might have problems later in life. The

taboos are often very explicit; complex kinship, marriage,

and other cultural protocols have been in place for centuries

that prevent close coupling. Furthermore, measuring the

“inbreeding coefficient” did not benefit the community;

rather it may have caused harm and distress over

misinterpretation of the term.

Access to medical records: In the Havasupai case, some

researchers gained access to medical records without

permission from tribal officials or clinic administrators.

Obtaining medical records without permission is illegal, but

safeguards should also be in place to prevent breach and

unauthorized use. In some cases, it is important for

researchers to have access to medical records; for

example, if researchers are trying to determine how many

individuals in a tribe have diabetes, they can look at

medical records to determine how many people have

already been diagnosed, and this can be useful to carry out

a research project on diabetes. However, before

researchers should be allowed to have access to medical

records and other medical information, there should be

clear rules and guidelines on who can have access to the

information and specifically what information can be

accessed and for what purpose. For example, in the case

of diabetes, researchers might be allowed to have access to

information related to blood sugar levels, but should not be

allowed to have access to unrelated information such as

mental health, cancer, or other potential diseases that a

patient may have. Medical records should be secured in a

safe place where only authorized users can have access. If

the medical records are kept in an electronic format, such

as on a computer, they should be encrypted and stored on a

password-protected computer in a secure location.

Data from medical records could include a person’s genetic

information in addition to information about physical

characteristics (such as age, height, weight, blood pressure

measurements, disease status, medical prescription

information, and more). Medical records also contain

names and other personal identifiers, but that information is

not important for researchers to carry out a study. In cases

where it is not important to have personal information about

a person, researchers can “de-identify” a sample by

removing or not including information such as names and

addresses that would link a person to a sample. It is very

important to have a system in place to prevent researchers

and other unauthorized users from accessing personal

identifiers.

The Privacy Rule within the Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPAA) can offer some protection for

research participants. The Privacy Rule requires that

personal identifiers such as name, address, birthday, phone

numbers, social security numbers, email addresses, driver

license numbers, photographs, or any other identifiers be

removed to protect the identity of the individual. The

Privacy Rule also extends to “all geographic subdivisions

smaller than a state, including street address, city, county,

precinct, ZIP code, and their equivalent geographical codes”

(Health 2011). HIPAA only applies to “covered entities,”

which include health care facilities and organizations which

handle health-related data, such as insurance companies.

However, if research data are shared with organizations

that do not fall under HIPAA, those entities are not required

to follow the Privacy Rule. In addition, genetic data

specifically are covered by the Genetic Information

Nondiscrimination Act of 2008. This law prohibits

discrimination in health coverage and employment based on

an individual’s genetic information,

There may be a few other enforcement mechanisms

available to tribes once research has begun, including

appeals to university Institutional Review Boards or funders

(e. g., the federal government) who oversee medical and

other research and have requirements related to informed

consent, data collection and management, data de-

identification and secondary use, and dissemination.

However, in order for tribes to maintain the greatest control

over research that takes place on their lands and/or with

their citizens, they should consider developing their own

research review processes.

Identification: By naming the Havasupai tribe on scientific

papers, there was a risk of identification to individuals.

Although individual tribal members were not named, the

Havasupai census was 650 around the time the project

began, and samples were collected from about 400

Havasupai individuals. For potentially stigmatizing

research such as on inbreeding or schizophrenia,

identification of individuals becomes a concern. In

scientific publications, the tribe was described as “an

isolated Native American population, Havasupai of Arizona”

(Markow, Hedrick et al. 1993). Supai, AZ is such a small

town in an isolated part of the Grand Canyon that it is

relatively easy to identify people from that area.

Control of samples: When entering into a research

agreement or when deciding whether to participate, tribes

should consider whether they will enforce control over how

samples can and should be used, and dictate what can or

cannot be done with samples.

1 Some strategies that tribes might consider are to: 1)

create policies over control of samples, 2) suggest

changes in the informed consent form before

researchers begin to recruit individuals to the study, 3)

carefully review the policies from the researcher’s

institution. For more information on model research

agreements, informed consent form language, and

policies, please see Regulating Genetics Research in

Your Community.

2 Sometimes the researcher’s institution already has a

policy that states all samples that are obtained

become property of that institution. Some tribes have

their own research review boards and may have

requirements already in place for control of data or a

requirement to return data to the tribe at the

completion of a research study. However, ownership

of samples typically resides with the university where

the researcher is from. Even if control remains solely

with the researcher and his/her institution, tribes

should take the time to understand what the ownership

policies are for the institution. Sometimes tribes and

universities need to negotiate the differences between

the return of data and data ownership policies. For

more information on tribal data control and data

sharing, please see Sharing Data and Protecting Your

Community.

Discussion Questions:

1 What issues were raised in the Havasupai case? How

would your tribe respond to the issues that were raised

in the Havasupai case?

2 What were the risks to Havasupai individuals and to tribal

members? Would these also raise issues for your

tribe?

3 If your tribe decided to participate in genetic research,

how would you ensure full understanding (“informed

consent”) of the project goals?

4 What protections does your tribe have for tribal members

who decide to enroll in a research project as a

research participant?

5 What privacy protections would your tribe require?

6 Would it be okay for researchers to use your tribal

affiliation (i.e., Havasupai tribe) in publications, or

would you prefer that your tribe remain anonymous

(i.e., an American Indian tribe)? What are the reasons

for your decision?

How Do We Decide?

A Guide for American Indian/Alaska Native

Communities

The interactive decision guides provide a set of interactive

questions to help you reflect on your feelings regarding

research. Read More

• Home For Tribes For Researchers About Us Contact Us

Privacy Policy Disclaimer

Funding provided by National Human Genome Research

Institute (NHGRI)

You might also like

- The Psychology of Human SexualityDocument26 pagesThe Psychology of Human SexualityHailie JadeNo ratings yet

- Fausto-Sterling - The Five Sexes, RevisitedDocument7 pagesFausto-Sterling - The Five Sexes, RevisitedOni Jota50% (2)

- Romancing the Sperm: Shifting Biopolitics and the Making of Modern FamiliesFrom EverandRomancing the Sperm: Shifting Biopolitics and the Making of Modern FamiliesNo ratings yet

- AJPH - Sexual Behaviour in The Human MaleDocument5 pagesAJPH - Sexual Behaviour in The Human Maleel_papi98No ratings yet

- Issue Analysis Paper Cultural Competence in Nursing ApplebachDocument18 pagesIssue Analysis Paper Cultural Competence in Nursing Applebachapi-283260051No ratings yet

- Chu v. GuicoDocument2 pagesChu v. GuicoErvin John ReyesNo ratings yet

- Havasupai CaseDocument17 pagesHavasupai CaseCatalina NeculauNo ratings yet

- Genetic Research Among The Havasupai: A Cautionary Tale: Robyn L. Sterling, JD, MPHDocument10 pagesGenetic Research Among The Havasupai: A Cautionary Tale: Robyn L. Sterling, JD, MPHMin KyuNo ratings yet

- Race-Ethnicity in ResearchDocument32 pagesRace-Ethnicity in ResearchashankarNo ratings yet

- Indian Tribe Wins Fight To Limit Research of Its DNADocument8 pagesIndian Tribe Wins Fight To Limit Research of Its DNAAngie MandeoyaNo ratings yet

- Refashioning Race - Dna and The Politics of Health Care. Anne Fausto-SterlingDocument37 pagesRefashioning Race - Dna and The Politics of Health Care. Anne Fausto-SterlingOntologiaNo ratings yet

- Meston & Ahrold, 2008Document11 pagesMeston & Ahrold, 2008Gurvinder KalraNo ratings yet

- Race and SocietyDocument17 pagesRace and SocietyJohn Micah MalateNo ratings yet

- Genes, Peoples and LanguagesDocument7 pagesGenes, Peoples and LanguagesSergio PareiraNo ratings yet

- Ableism and Anti-BlacknessDocument8 pagesAbleism and Anti-BlacknessDarrian Carroll100% (1)

- Annals of The New York Academy of Sciences - 2010 - Williams - Race Socioeconomic Status and Health ComplexitiesDocument33 pagesAnnals of The New York Academy of Sciences - 2010 - Williams - Race Socioeconomic Status and Health ComplexitiesMahmudul Hasan SakilNo ratings yet

- Biology and IdentityDocument24 pagesBiology and IdentityOntologiaNo ratings yet

- Genetics and EssentialismDocument8 pagesGenetics and EssentialismJoMarie13No ratings yet

- Van Der Ven Susser 2023 Structural Racism and Risk of SchizophreniaDocument3 pagesVan Der Ven Susser 2023 Structural Racism and Risk of SchizophreniaLink079No ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Homosexuality in Men: A Term PaperDocument6 pagesFactors Influencing Homosexuality in Men: A Term PaperIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- The Status of The Race Concept in Physical AnthropologyDocument36 pagesThe Status of The Race Concept in Physical AnthropologyVictor RosezNo ratings yet

- J Terry Lesbians Under The Medical GazeDocument24 pagesJ Terry Lesbians Under The Medical GazeJillian Grace HurtNo ratings yet

- (Bioarchaeology and Social Theory) Danielle Shawn Kurin (Auth.) - The Bioarchaeology of Societal Collapse and Regeneration in Ancient Peru-Springer International Publishing (2016)Document229 pages(Bioarchaeology and Social Theory) Danielle Shawn Kurin (Auth.) - The Bioarchaeology of Societal Collapse and Regeneration in Ancient Peru-Springer International Publishing (2016)JOSE FRANCISCO FRANCO NAVIANo ratings yet

- Acculturation, Gender Disparity, and The Sexual Behavior of Asian American YouthDocument15 pagesAcculturation, Gender Disparity, and The Sexual Behavior of Asian American YouthVheey WattimenaNo ratings yet

- Angela Tharp PaperDocument6 pagesAngela Tharp PaperGeovanny Ramirez GiraldoNo ratings yet

- Tuskegee Syphilis Study ThesisDocument7 pagesTuskegee Syphilis Study ThesisCarmen Pell100% (1)

- End-Of-life Issues For Aboriginal Patients A Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesEnd-Of-life Issues For Aboriginal Patients A Literature ReviewafmabreouxqmrcNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 45.152.181.20 On Thu, 11 Mar 2021 15:01:07 UTCDocument18 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 45.152.181.20 On Thu, 11 Mar 2021 15:01:07 UTCMihai Vasile GeorgescuNo ratings yet

- Cells Genes and Stories by Priscilla WaldDocument19 pagesCells Genes and Stories by Priscilla WaldClarissa WorcesterNo ratings yet

- Eugenics Research Paper TopicsDocument5 pagesEugenics Research Paper TopicsmajvbwundNo ratings yet

- AAPA Statement On Race and RacismDocument3 pagesAAPA Statement On Race and RacismAngelina GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Havasupai Tribe v. Arizona Board of RegentsDocument50 pagesHavasupai Tribe v. Arizona Board of RegentsMikela St. JohnNo ratings yet

- Self-Reported Sexuality Among Women With and Without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)Document227 pagesSelf-Reported Sexuality Among Women With and Without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)Νήρια ΒαρβέρηNo ratings yet

- TOK May 2019 Title EssayDocument7 pagesTOK May 2019 Title Essayriya50% (2)

- Parental Attitudes About Sexual EducationDocument17 pagesParental Attitudes About Sexual EducationMera DeliaNo ratings yet

- AcculturationDocument3 pagesAcculturationFlory OanaNo ratings yet

- 2009 Article 9079Document5 pages2009 Article 9079Rodrigo BonsaverNo ratings yet

- Euthanasia RP 2Document3 pagesEuthanasia RP 2SHIVINo ratings yet

- Euthanasia RP 2Document3 pagesEuthanasia RP 2SHIVINo ratings yet

- Forensics Science ProjectDocument9 pagesForensics Science ProjectTanya SinglaNo ratings yet

- Prescription for Heterosexuality: Sexual Citizenship in the Cold War EraFrom EverandPrescription for Heterosexuality: Sexual Citizenship in the Cold War EraNo ratings yet

- Sex, Sin, and The Church: The Dilemma of HomosexualityDocument7 pagesSex, Sin, and The Church: The Dilemma of HomosexualityRoua KrimiNo ratings yet

- Yudell 2016Document2 pagesYudell 2016Andrés GonzálezNo ratings yet

- ERQ AcculturationDocument2 pagesERQ AcculturationCharlesNo ratings yet

- Gender EuphoriaDocument25 pagesGender EuphoriaillaritzaNo ratings yet

- Hill, Willoughby - 2005 - The Development and Validation of The Genderism and Transphobia Scale PDFDocument14 pagesHill, Willoughby - 2005 - The Development and Validation of The Genderism and Transphobia Scale PDFDan22212No ratings yet

- RAHMAN - Sexual OrientationDocument12 pagesRAHMAN - Sexual OrientationGuilherme JawaNo ratings yet

- The Genetic Ancestry Testing and Scientific RacismDocument12 pagesThe Genetic Ancestry Testing and Scientific RacismDure ShahwarNo ratings yet

- Hmong Research PaperDocument9 pagesHmong Research Papercammtpw6100% (1)

- PsychSexuality - and Sexual APDocument66 pagesPsychSexuality - and Sexual APDaniela Stoica100% (1)

- Term Paper About TransgenderDocument7 pagesTerm Paper About Transgenderafdtsxuep100% (1)

- Ethnocultural InfluencesDocument17 pagesEthnocultural Influencesmuwaag musaNo ratings yet

- Complete Week 2 Assignment Correction With in Text CitationDocument7 pagesComplete Week 2 Assignment Correction With in Text CitationRhonda ReedNo ratings yet

- BARRON, C and CAPOUS-DESYLLAS, M - Transgressing The Gendered Norms in Childhood - Transgender Children and Families PDFDocument33 pagesBARRON, C and CAPOUS-DESYLLAS, M - Transgressing The Gendered Norms in Childhood - Transgender Children and Families PDFArthurLeonardoDaCostaNo ratings yet

- "It Wasn't Feasible For Us": Queer Women of Color Navigating Family FormationDocument14 pages"It Wasn't Feasible For Us": Queer Women of Color Navigating Family FormationJo WilsonNo ratings yet

- Critical EssayDocument5 pagesCritical EssayJacqueline Joy BurroughsNo ratings yet

- The Bioarchaeology of Social Control: Ryan P. HarrodDocument27 pagesThe Bioarchaeology of Social Control: Ryan P. Harrodcarlos miguel angel carrascoNo ratings yet

- Abortion Pills, Test Tube Babies, and Sex Toys: Emerging Sexual and Reproductive Technologies in the Middle East and North AfricaFrom EverandAbortion Pills, Test Tube Babies, and Sex Toys: Emerging Sexual and Reproductive Technologies in the Middle East and North AfricaNo ratings yet

- Relational AlgebraDocument53 pagesRelational AlgebraJeyc RapperNo ratings yet

- Assessment II - Project ManagementDocument21 pagesAssessment II - Project ManagementJürg Müller0% (2)

- Doru Costache - Glimpses of A Symbolic Anthropology 4Document2 pagesDoru Costache - Glimpses of A Symbolic Anthropology 4Doru CostacheNo ratings yet

- MFIs in UgandaDocument34 pagesMFIs in UgandaKyalimpa PaulNo ratings yet

- Benefits of DecentralisationDocument2 pagesBenefits of DecentralisationSmita JhankarNo ratings yet

- Formal Education in The Middle AgesDocument64 pagesFormal Education in The Middle AgesAnjenethAldaveNo ratings yet

- #Karenhudes Karen Hudes Jesuit Vatican Gold #Chemtrails #Geoengineering PDFDocument20 pages#Karenhudes Karen Hudes Jesuit Vatican Gold #Chemtrails #Geoengineering PDFsisterrosettaNo ratings yet

- A Controvésia de Sião e o Tempo Da Angústia de JacóDocument5 pagesA Controvésia de Sião e o Tempo Da Angústia de Jacófabiano_palhanoNo ratings yet

- 22) Disaster Debris Management During The 2014-2015 MalaysiaDocument8 pages22) Disaster Debris Management During The 2014-2015 MalaysiaSusi MulyaniNo ratings yet

- Lab Report Exp. 3 FST261Document12 pagesLab Report Exp. 3 FST261Hazwan ArifNo ratings yet

- Nursery ApplicationDocument4 pagesNursery ApplicationMonotosh ByapariNo ratings yet

- Session 11 - Circular FailureDocument36 pagesSession 11 - Circular FailureNicolás SilvaNo ratings yet

- Chap1 - The Operational AmplifierDocument40 pagesChap1 - The Operational AmplifierzalikaseksNo ratings yet

- Erp Project AhsanDocument30 pagesErp Project Ahsanadeeba hassanNo ratings yet

- Beginning Journey - First Nations Pregnancy GuideDocument120 pagesBeginning Journey - First Nations Pregnancy GuideLena MikalaNo ratings yet

- ST Sir Gems, Subhadip Sir Pivots and Explanation of IDF by DR - VivekDocument101 pagesST Sir Gems, Subhadip Sir Pivots and Explanation of IDF by DR - VivekUsha JagtapNo ratings yet

- Digital Logics QuestionsDocument2 pagesDigital Logics QuestionsMSMETOOLROOM CITDNo ratings yet

- Settlement in Lacrosse CaseDocument4 pagesSettlement in Lacrosse CaseRobert WilonskyNo ratings yet

- What Makes Man Truly HumanDocument8 pagesWhat Makes Man Truly HumanMarylene Mullasgo100% (1)

- Exercise 1Document4 pagesExercise 1Nico RobinNo ratings yet

- Program - NCS 10th ConConDocument8 pagesProgram - NCS 10th ConConJim HoftNo ratings yet

- Management of Hypersensitivity ReactionDocument6 pagesManagement of Hypersensitivity Reactionmbeng bessonganyiNo ratings yet

- Why Should We Hire You? Learn How To Answer This Job Interview QuestionDocument24 pagesWhy Should We Hire You? Learn How To Answer This Job Interview QuestionDeniz SasalNo ratings yet

- Revision and Reflection L4M2 v1-3Document15 pagesRevision and Reflection L4M2 v1-3MWAKA DERRICKNo ratings yet

- Final Project IkbalDocument60 pagesFinal Project Ikbalikbal666No ratings yet

- Languages of PakistanDocument16 pagesLanguages of PakistanAtyab AliNo ratings yet

- Ch.1 - Introduction: Study Guide To Accompany Operating Systems Concepts 9Document7 pagesCh.1 - Introduction: Study Guide To Accompany Operating Systems Concepts 9John Fredy Redondo MoreloNo ratings yet

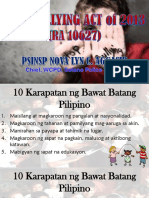

- Ra 10627Document41 pagesRa 10627Nvpmfc Ppo100% (1)

- 6 Psychoanalytic Theory: Clues From The Brain: Commentary by Joseph LeDoux (New York)Document7 pages6 Psychoanalytic Theory: Clues From The Brain: Commentary by Joseph LeDoux (New York)Maximiliano PortilloNo ratings yet