Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2002 Email-Marketing Chraq PDF

2002 Email-Marketing Chraq PDF

Uploaded by

Geetika KhandelwalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2002 Email-Marketing Chraq PDF

2002 Email-Marketing Chraq PDF

Uploaded by

Geetika KhandelwalCopyright:

Available Formats

PERMISSION E-MAIL MARKETING

Permission E-mail

Marketing

as a Means of Targeted Promotion

Hospitality operators should be able to use e-mail marketing (by permission) to build relationships

with their existing customers. The question is how to make it work.

BY ANA MARINOVA, JAMIE MURPHY, AND BRIAN L. MASSEY

E

-mail offers the hospitality industry a flexible and in- while a healthy four of five primary shoppers in the United

expensive tool for testing and distributing sales and States flip through mail-order catalogues sent to them, only

promotional messages to existing customers and pros- half actually buy an item out of those catalogues.3 That statis-

pects. Despite the explosion of internet-based communica- tic raises the question of whether direct mail is losing its punch

tion, however, conventional direct-mail has increased four- as a way of reaching customers.

fold in the past decade.1 One consequence of the increasing Marketers have responded to customers’ lack of interest by

volume of paper that people receive is that just 75 percent of trying to strengthen their mailing lists.4 It is common today

direct mail is opened nowadays, compared to an estimated to create targeted lists by analyzing customer-information

90 percent just a few years ago.2 That does not say anything databases and developing profiles of people who are most likely

about response to direct-mail messages, since opening does to be repeat buyers. The heart of relationship manage-

not automatically lead to buying. Researchers have found that ment lies in understanding one’s consumers: their preferences,

purchasing histories, and future purchasing intentions. Study-

1

D. Bird, “Direct Marketing Is as Relevant Now as It Was in 1900,” ing those factors helps marketers better profile their target

Marketing, October 12, 2000, p. 28.

2

Ibid. 3

D. Bell and D. Gordon, “Note on the Mail-order Industry,” Harvard

Business School Publishing, March 1995, pp. 1–16.

© 2002, CORNELL UNIVERSITY 4

See: F. Newell, loyalty.com (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2000).

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on November 7, 2015

FEBRUARY 2002 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 61

MARKETING PERMISSION E-MAIL

audiences for the potential delivery of personal- Permission Marketing via E-mail

ized products and services.5 The idea of so-called permission marketing is to

Data that a company collects from or about a cultivate a relationship with customers who have

consumer are considered to be its property. Those given a marketer the go-ahead to send them in-

data are legally available for marketing campaigns formation about a product, service, special offer,

until that customer “opts out,” or explicitly asks or sale.10 Such an approach “decreases the mail-

to be removed from the mailing list.6 Despite the ing volume but raises the percentage of success,”11

opt-out possibilities, consumers are growing ever and becomes potentially more effective through

more concerned about how businesses are using the use of information technology. Compared to

information about them.7 previous approaches, e-mail allows for easier cus-

Seth Godin has noted that in many cases con- tomer-data collection and more solid analysis of

sumers see direct-marketing regular mail—com- that data.

monly called junk mail—as the paper equivalent Permission marketing has three characteristics

of spam (the now-ubiquitous unsolicited e-mail).8 that set it apart from traditional direct (mail)

Both junk mail and spam arrive unanticipated marketing.12 Customers who permit their names

and unbidden, and they both clutter up people’s to be included on direct-mail lists can anticipate

mail (or e-mail) boxes. Such a comparison makes receiving commercial messages; the sending com-

e-mail an unattractive vehicle for reputable com- pany can personalize those messages; and the mes-

panies with established brand names. sages will be more relevant to the customers’

This is where “permission marketing” enters needs. Godin has likened permission marketing

into the direct-marketing equation. Obtaining a to “dating” a customer.13 Permission marketing

customer’s permission to be contacted as part of involves a long-term process that requires an in-

an advertising campaign works to the company’s vestment of time, information, and resources by

benefit.9 To begin with, obtaining permission both parties. The result is an active, participa-

promotes a corporate image of responsibility and tory, and interactive relationship between both

respect for the consumer. That, in turn, helps sides of the sales equation.

forge and maintain strong commercial relation- A company that embarks on a permission-

ships with current and prospective clients. Such marketing campaign will likely see its objectives

a personal relationship helps the marketer’s mes- evolve from mere communication to include

sage cut through the advertising clutter by creat- measuring the different levels of permission its

ing a distribution list of customers who want to customers grant it. A key part of cultivating a

receive that firm’s communications. relationship with one’s customers is to obtain

from them increasingly greater levels of permis-

5

See: Ibid.; and R. Stone and J.B. Mason, “Relationship sion for receiving commercial messages of either

Management: Strategic Marketing’s Next Source of Com- kind. In turn, customers who grant increasing

petitive Advantage,” Journal of Marketing Theory and Prac-

tice, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Spring1997), pp. 8–19.

levels of permission are signaling increasing trust

6

in the company—and that potentially translates

See, for example: Kin-nam Lau, Kam-hon Lee, Pong-yuen

Lam, and Ying Ho, “Web-site Marketing for the Travel-

into profit.

and-Tourism Industry,” Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Ad- Five levels of permission can be won from

ministration Quarterly, Vol. 42, No. 6 (December 2001), customers targeted by a permission-marketing

pp. 55–62.

7

J. Phelps, G. D’souza and G. Nowak, “Antecedents and 10

See: Godin, op. cit.; and S. Krishnamurthy, “A Compre-

Consequences of Consumer Privacy Concerns: An Empiri- hensive Analysis of Permission Marketing,” Journal of

cal Investigation,” Journal of Interactive Marketing, Vol. 15, Computer Mediated Communication, Vol. 6, No. 2 (2001)

No. 4 (2001), pp. 2–18. at www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol6/issue2/krishnamurthy.html,

8

S. Godin, Permission Marketing: Turning Strangers into as viewed on February 10, 2002.

Friends, and Friends into Customers (New York: Simon & 11

R. Perlstein, “Getting Permission,” Zip Target Marketing,

Schuster, 1999). Vol. 9, No. 7 (July 1986), p. 36.

9

See: Ibid.; and S. Krishnamurthy, “Spam Revisited,” Quar- 12

Godin, op. cit.

terly Journal of Electronic Commerce, Vol. 1, No. 4 (2000),

pp. 305–321. 13

Ibid.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on November 7, 2015

62 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly FEBRUARY 2002

PERMISSION E-MAIL MARKETING

campaign, according to Godin.14 In descending the hospitality industry, such intermediaries in-

order of involvement, he terms those levels as clude Travelocity, Click International, and

follows: intravenous, points, personal relation- Expedia. These companies typically induce web-

ship, brand trust, and situation. site visitors to register for e-mail newsletters or

“Intravenous” is the highest kind of permis- special-promotion updates. Customers provide

sion to be won from customers. It involves cus- data about themselves as part of the registration

tomers trusting the marketer to make buying process, and the intermediaries use that data to

decisions for them. target newsletter advertisements to specific cus-

“Points” permission involves customers allow- tomers (based on demographic assumptions).

ing the company to collect personal data and to

market its products and services to them on a One Hotel’s Experiment with

points-based loyalty scheme—the level of most Permission E-mail

frequent-customer programs. We conducted a study of an Australian hotel’s

The “personal relationship” level of permis- initial efforts to use e-mail at the “brand trust”

sion uses individual relationships between the level of permission marketing, in hopes of devel-

customer and marketer to temporarily refocus the oping a technique of customer-relationship man-

attention or modify a consumer’s behavior. For agement. The hotel’s broad goal was to experi-

example, an airline may target those frequent- ment with forging an interactive relationship with

flyer customers with hundreds of thousands of its customers through a permission-marketing

accumulated miles. This personalized approach e-mail campaign. Its specific goals were to en-

is the best way to sell customized, expensive, or courage repeat visits by previous guests, retain

highly involving products. them as part of the hotel’s customer base, and to

With “brand trust” permission, the customer increase the number of hotel services that guests

has developed a level of confidence in a product used during their stays.

or service that carries a particular, well-known

brand name. Brand-trust customers are likely to

give their permission to receive sales or promo- Obtaining a customer’s permission

tional messages about other items produced un- to be contacted as part of an

der the same trusted brand.

“Situation” permission is a one-time or limited- advertising campaign works to

time permission, which is the least potent of the company’s benefit.

the five levels of permission. This permission is given

when the customer agrees to receive sales or pro-

motional messages from a company for a specified Located in Perth, the capital of Western

time. This would occur, for instance, if a per- Australia, the hotel is part of a major interna-

son agrees to let a cold-calling sales person send tional chain. It targets the business-travel mar-

a packet of information about a travel package. ket, in which it maintains a “preferred hotel”

So far we have been discussing permission status with several client companies. Domes-

marketing in terms of a direct relationship, in tic and international leisure travelers also pa-

which the customer and company communicate tronize this hotel, and it markets itself as a site

directly, and the company typically offers the for hosting special functions and events. The

customer an additional service as an inducement hotel’s food service features restaurants, a caf-

to maintain the relationship. However, it is also eteria, and a bar, all of which are patronized

possible to conduct a permission-marketing pro- by its guests and local residents.

gram through intermediaries. In an intermedi- The hotel routinely collects detailed guest in-

ary relationship, the customer interacts with a formation at registration and throughout the

third party to the commercial transaction.15 For guests’ stay. These data include guests’ names,

addresses, the number of times they have stayed

14

Ibid. at the hotel, and their average spending during

15

Krishnamurthy, op. cit. their stays.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on November 7, 2015

FEBRUARY 2002 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 63

MARKETING PERMISSION E-MAIL

EXHIBIT 1 either responded—by e-mail—to say “thank you”

or, better still, took advantage of a particular

Permission-marketing e-mail treatments special offer.

Those early experiences encouraged the hotel’s

management to take the next step by establish-

Personalized Generic

salutation salutation

ing a full-fledged permission-marketing cam-

paign that targeted promotional e-mail to po-

High subject Sample 1 Sample 2

tential and current customers. To that end, the

relevance Dear Dear Valued Guest;

Complimentarytitle Take advantage of managers designed and conducted an “opt out”

Guestfirstname Hotelname’s Latest e-mail permission-marketing campaign. That is,

Guestlastname; Promotions people who received the hotel’s e-mail could re-

Take Advantage of

spond and ask that their names be removed from

Hotelname’s Latest

Promotions its e-mailing list, but the hotel did not ask them

first whether they wanted to receive that initial

Low subject Sample 3 Sample 4 promotional message.

relevance Dear Dear Valued Guest;

Relevance. The goal for this study was to iden-

Complimentarytitle News and Special

Guestfirstname Offers tify factors that could influence the effectiveness

Guestlastname; of an e-mail permission-marketing campaign.

News and Special The study also examined implementation issues

Offers

related to the hotel’s experimental campaign—

for example, how to handle the subject line in

Note: Each cell totaled 200 recipients. each e-mail message. The subject line is arguably

the most important field for marketers because

what the sender writes in that space has a lot to

do with whether the receiver is enticed into read-

ing the message.16 Just as direct-mail marketers

The hotel began collecting guests’ e-mail ad- fret over such issues as package size, design, and

dresses with the aim of replacing its printed message wording, e-mail marketers should con-

direct-mail initiatives with a less-expensive e-mail cern themselves with the text of subject lines.

marketing campaign. The e-mail addresses were We have seen few studies that explore the is-

gathered primarily from guest registrations, busi- sue of subject-line relevance, however. This led

ness cards left behind by hotel and restaurant to our first research question: “Will subject titles

guests, and from feedback questionnaires avail- that are highly relevant to the product or service

able in its restaurants. The hotel also used an in- being promoted (and, presumably, to the

ternal database compiled by its business- receiver’s need) generate larger response rates

development unit, which contained contact in- than subject titles that are low in relevance?”

formation—including e-mail addresses—for Personalization. Del Webb Corporation is

travel and function organizers, travel agents, and one firm that has experimented with personal-

tour operators. In all, the hotel’s database num- izing e-mail subject lines. The company found

bered some 6,000 records, of which 4,000 were that when it added the recipient’s first name

for its past guests. to the subject line, its response rate doubled—

The hotel’s e-mail marketing efforts—before to more than 12 percent—over e-mail that was

it undertook its permission-marketing experi- not personalized.17 The literature on customer-

ment—were sporadic at best. It previously used

e-mail to promote special room and restaurant

16

offers to members of its frequent-dining club. J. Hoffman, “The Anatomy of E-mail Marketing,”

Direct Marketing, Vol. 63, No. 3 (July 2000), pp. 38, 40.

Those tentative forays into e-mail marketing net-

17

ted generally positive feedback from their lim- E. Colkin, “Marketing Capitalizes on E-mail,”

InformationWeek (July 23, 2001) at www.informationweek.

ited audiences. Many of the dining-club mem- com/story/IWK20010719S0014, as viewed on February 10,

bers who received the hotel’s promotional e-mail 2002.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on November 7, 2015

64 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly FEBRUARY 2002

PERMISSION E-MAIL MARKETING

relationship management argues that personal- EXHIBIT 2

ization is a critical element for sales success.18

Along this line, the second research question Sample of hotel’s promotional e-mail message

was: “Will a permission-marketing campaign

using personalized e-mail generate a larger re-

Dear [personalized or generic salutation],

sponse rate than generic, mass-delivered e-mail

messages?” Hotel [name] thanks you for your past patronage and wishes to inform you in

Opt in or opt out? Two more research ques- advance of upcoming specials and promotions.

tions investigated opt-out requests from the

Please visit [URL] for details on:

hotel’s e-mail campaign recipients. The decision

to conduct an opt-in or opt-out permission- 1. Winter Break Accommodation Package—valid until 31 August 2001.

marketing campaign is an important one for 2. Curries of the World—[Name] Diner.

marketers. In an opt-out campaign, targeted cus- 3. Midweek Dinner Special—[Name] Restaurant.

4. Kids-eat-free Buffet—[Name] Restaurant.

tomers receive an initial e-mail that delivers a pro- 5. Musical Evenings—[Name] Restaurant.

motional message, but also offers recipients a way 6. Best of Western Australian Buffet—[Name] Restaurant.

to remove their names from the e-mailing list.

An opt-in campaign, by comparison, involves You’ve received this e-mail to inform you of upcoming events. Please e-mail

specials1@hotel[name].com to stop receiving this information.

explicitly asking customers whether they want to

receive promotional e-mail in the first place. Best regards,

In this study, the Australian hotel tested an [Name]

opt-out approach. Accordingly, the third research Director of Marketing

Hotel [Name] [URL]

question we investigated was, “Does high

subject-line relevance yield fewer instances of

opting out among e-mail recipients?” Similarly, Note: The high-relevance version of the e-mail carried the subject line,

the fourth question asked, “Does e-mail person- “Take Advantage of [hotel name]’s Latest Promotions.” The low-relevance version’s

subject line said simply, “News and Special Offers.” The personalized version

alization function to reduce recipients’ opting- began, “Dear [Mr., Ms., etc., First Name and Last Name of Guest].”

out behavior?” The generic version began with, “Dear Valued Guest.”

Study method. The 6,000 guests for whom

the hotel had e-mail addresses had not explicitly

agreed to receive sales or promotional e-mailings

from the hotel. The hotel chose to not pursue a So, rather than simply send messages to the

two-step process of e-mailing its entire list to ask entire 6,000 addresses in its database, the hotel’s

for recipients’ opt-in permission and then con- managers decided to test the waters of permis-

tacting only those who agreed to receive addi- sion e-mail marketing by sending messages to just

tional e-mailings. The risk it faced with an opt- 800 of the guests on its e-mail distribution list.

in strategy of that kind was that customers would With benefit of hindsight, we now recognize a

not opt in and the e-mail distribution list would problem that the hotel failed to consider when it

shrink unduly. On the other hand, with its opt- selected the opt-out approach over the opt-in

out approach the hotel risked alienating an un- campaign. As it turned out, a large portion of its

known number of its former guests who would e-mail list consisted either of bad addresses or

be offended by receiving an unbidden commer- the addresses were miskeyed in the sending. An

cial message, even with the opt-out opportunity. opt-in strategy would have caught those errors

before the actual sales message was sent out.

The hotel used a “two-by-two matrix” to test

18

the effects on response rates of the relevance of

See: D. Peppers, M. Rogers, and B. Dorf, “Is Your Com-

pany Ready for One-to-One Marketing?,” Harvard the e-mail’s subject line and the personalization

Business Review, Vol. 77, No. 1 (January–February 1999), of the promotional message. The matrix arrange-

pp. 151–160; J. Pine, B. Victor, and A. Boynton, “Making ment is shown in Exhibit 1.

Mass Customization Work,” Harvard Business Review,

Vol. 71, No. 5 (September–October 1993), pp. 108–119; For the first e-mail run, four samples of 100

and Newell, op. cit. e-mail addresses each were drawn at random from

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on November 7, 2015

FEBRUARY 2002 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 65

MARKETING PERMISSION E-MAIL

EXHIBIT 3 e-mailing is to purchase specialized software,

while the alternative is to manually personalize

each message. The hotel personalized the e-mails

Response rates by e-mail-message treatment

using a merge function and a little program that

its IT manager wrote for Lotus Notes.

Valid (delivered) Opt-out Web-page

The personalized version of the hotel’s pro-

messages requests visits

motional e-mail message began with a compli-

High relevance mentary title (“Dear Mr., Ms., Dr., or Profes-

Personalized (Sample 1) 112 4 (3.6%) 9 (8.0%) sor),” followed by the recipient’s first and last

Generic (Sample 2) 121 0 11 (9.1%) name. The generic salutation was “Dear Valued

Low relevance

Guest.”

To add relevance to the message, the hotel

Personalized (Sample 3) 128 4 (3.1%) 8 (6.3%)

included its name in the subject line. The idea

Generic (Sample 4) 131 2 (1.5%) 11 (8.4%)

was that the name would be familiar to the

e-mail’s recipients because of their prior involve-

ment with the hotel. Therefore, the high-

relevance version of the e-mail carried this sub-

ject line: “Take Advantage of [hotel name]’s Lat-

the hotel’s e-mail database. All 400 recipients re- est Promotions.” Conversely, the low-relevance

ceived the same basic e-mail message (shown in version carried this obviously ambiguous subject

Exhibit 2, on the previous page), except that each line: “News and Special Offers.”

sample of 100 received one of the experimental Fall tonic. The hotel sent out its first batch

variations in personalization and subject-line rel- of 400 e-mails on a Tuesday afternoon in April

evance. The hotel then repeated the process with 2001, as past experience indicated that the mid-

four more sets of 100 respondents each. week days were typically the heaviest in terms of

The basic message was crafted to satisfy the internet users’ visits to the hotel’s web site. The

characteristics that Weylman outlines for effec- e-mailing was repeated step-for-step a week later

tive direct-mail communication.19 It was brief, to a different batch of 400 e-mail addresses drawn

its language was straightforward, and its call to at random from the hotel’s database. This was

action (its request that recipients visit the hotel’s done to increase the validity of the experiment

web page) gave it the quality of clarity. The mes- and to guard against over-generalizing from the

sage asked recipients to visit a hotel web page for results.20 In all, then, each of the four experimen-

details about six promotional events and provided tal treatments—or each version of the hotel’s pro-

a return e-mail address for opting out of future motional message—was sent to 200 individual

messages. It ended with the hotel’s marketing recipients in the two e-mailing waves.

director’s “signature” as a way to ensure against Each version of the e-mail directed its recipi-

its recipients’ mistaking it for spam. The six room ents to one of four web pages that the hotel es-

and restaurant promotions that the message high- tablished specifically for gauging the response to

lighted arguably can be seen as offering recipi- its experiment. Each web page was monitored

ents “stimulation,” or incentives or rewards for for one week from the day the e-mail message

their attention. was distributed, as responses to commercial

Keyed by hand. The last characteristics cited e-mail generally occur within a few days of re-

by Weylman, personalization, was, as we said, one ceipt.21 The opt-out e-mail address also was moni-

of the treatments of the hotel’s experiment. The tored for one week to gauge that form of “unsuc-

easiest way to add personalization to a mass cessful” response to the hotel’s campaign.

20

E. Babbie, The Practice of Social Research, eighth edition

19

(Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing, 1998).

C.R. Weylman, “Direct Mail that Gets Opened and

21

Read,” American Salesman, Vol. 44, No. 10 (October 1999), L. Wathieu, “Yesmail.com,” Journal of Interactive

pp. 13–17. Marketing, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Summer 2000), pp. 79–92.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on November 7, 2015

66 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly FEBRUARY 2002

PERMISSION E-MAIL MARKETING

Bounce Backs and Opt Outs EXHIBIT 4

The hotel successfully reached 61.5 percent of

the 800 recipients targeted in its two experimen- Results by research questions

tal e-mail distributions, as shown in Exhibit 3.

This was a much lower penetration than the ho- Web-page visits

tel expected. Nearly two-fifths of the 800 pro- RQ1: Will high subject-line relevance

motional e-mail messages bounced back as un- increase web-page visits?

deliverable, from non-working or incorrect e-mail High relevance (n = 233) 20 (8.6%)

addresses. Both distributions experienced a simi- Low relevance (n = 259) 19 (7.3%)

lar level of bounce backs, at about 38 percent

χ2 = .262, df1, p < .61

each. This high rate of undeliverable e-mail speaks RQ2: Will personalization increase web-page visits?

to the importance of ensuring e-mailing data-

Personalized (n = 240) 17 (7.1%)

bases are entered accurately and kept up to date—

Generic (n = 252) 22 (8.7%)

and that addresses are keyed correctly.

Opting out. Overall, ten people, or 2 per- χ2 = .457, df1, p < .50

cent of the 492 who received the promotional e- Number of

mail message, responded by denying the hotel Opt-out Requests

their permission to send them future e-mailings. RQ3: Will high subject-title relevance

The two personalized versions of the e-mail gen- decrease opt-out requests?

erated the highest opt-out rates, as shown in Ex- High relevance (n = 233) 4 (1.6%)

hibit 3. Even so, those rates stood at less than 4 Low relevance (n = 259) 6 (2.3%)

percent for each version. A generic message χ2 = .222, df1, p < .64

coupled with a subject line that was low in relevance

brought a dropout rate of less than 2 percent. RQ4: Will personalization decrease

None of the ten opt-out requesters seemed opt-out requests?

angered by their initial inclusion in the hotel’s Personalized (n = 240) 8 (3.3%)

e-mailings. The typical opt-out reply was politely Generic (n = 252) 2 (0.08%)

phrased as follows: “As I am a business visitor to χ2 = 3.982, df1, p < .05

your fair city, please don’t send me further mate-

rial such as this. Nevertheless, thank you for

thinking of me.”

None of the 121 people who received the ge- None of the four message treatments gener-

neric message with a highly relevant subject line ated many e-mail replies that requested additional

asked to be removed from the hotel’s e-mail information about the advertised promotions or

database. To the contrary, all of them seemingly expressed a desire to take advantage of them. In

were content to remain cued up with the hotel fact, the hotel received only two such replies, and

for future promotional e-mails. those were drawn from opposite ends of the

Hard to tell. As for generating web-site visits, message-treatment spectrum. One came from

the two generic versions of the promotional e-mail a recipient of the “personalized, high relevance”

appeared to work better than the personalized ver- version of the e-mail and the other came from a

sions, although only slightly so. The highest per- “generic, low relevance” recipient.

centage of web-site responses resulted from the Research questions. A statistically significant

generic version with high subject-line relevance, difference was noted in comparing the opt-out

which drew about 9 percent of its 121 recipients to rates generated by message personalization and

its companion web page, as Exhibit 3 shows. The no personalization (x2 = 3.982; df1, p < .05).

lowest response rate was found for the combina- This answered our fourth research question nega-

tion of message personalization and low subject- tively. As Exhibit 4 shows, a personalized sal-

line relevance. Still, all four versions brought utation actually resulted in the most opt-out

web-site visits that exceeded the 1- to 2-percent requests (eight), compared to just two for the

response rate typical of direct-mail campaigns. generic e-mail.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on November 7, 2015

FEBRUARY 2002 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 67

MARKETING PERMISSION E-MAIL

Chi-square tests showed no statistically sig- grant permission in advance before being in-

nificant pattern to opt-out requests connected cluded in a direct e-mailing. Customers may feel

to subject-line relevance. Those tests also showed a greater affinity for a company that allows them

that personalization and subject relevance of the to engage in such proactive behavior. The alter-

hotel’s promotional e-mails had no statistically native of reactive behavior—of withdrawing per-

noteworthy effect on whether recipients re- mission after the fact—likely brings a sense of

sponded by visiting the corresponding web-site annoyance at best to receivers of an unanticipated

visits. e-mailing.

Future research should consider comparing

Confounding the effectiveness of opt-in versus opt-out permis-

The literature argues for the benefit of sending sion e-mail marketing. Future studies could also

promotional mailings that are personalized to explore the subtleties of whether different forms

their recipients, but this Australian hotel’s experi- of address have any effect. Rather than opening

ment with permission e-mail marketing points a promotional message with “Dear Mr. John

to the opposite conclusion. We found that per- Doe,” for instance, a study could test the even

sonalization seemed to encourage customers to more formal (but perhaps more distant) “Dear

shield themselves from future commercial per- Mr. Doe” or a decidedly more familiar “Dear

suasion. We need to study this point more, but John” (or “Dear Jane”).

it may be that personalization is an ineffective This study also suggests that subject-line rel-

device for generating the desired customer re- evance may be largely irrelevant in a permission

sponses to promotional e-mail messages. The e-mail marketing campaign.The Australian ho-

hotel received responses to the personalized ver- tel saw no substantial differences in the perfor-

sions of its e-mail all right, but it was in the form mance of promotional e-mails in the high- and

of opt-out requests, and not in the form of web- low-relevance subject-line categories. But this

site visits. finding seems counterintuitive, considering that

One possible explanation for this effect is that cyber viruses distributed through e-mail com-

people might object to having their names used monly carry ambiguous subject lines. It seems

by marketers when the relationship is tenuous. reasonable, therefore, to expect internet users to

That is, adopting a sales approach of familiar- be suspicious of e-mails with low-relevance or

ity—approaching potential customers by name— ambiguous subject lines—and to not open them

may be counterproductive to the marketer’s pur- readily. Then again, maybe the promotions in this

poses when the customer has had little or no mailing just weren’t of interest to the recipients,

face-to-face interaction with the business—say, regardless of what the subject line said. It may

just one brief stay in a hotel. also be that early autumn in Australia (April) is

We think that laying a foundation for famil- not the time to send out messages of this kind.

iarity ahead of a mailing might instill a more fa- Easy to measure. The simplicity of running

vorable perception in customers, one more con- the e-mail experiments described here and mea-

ducive to a commercial objective. For example, suring web-page visits, bounced e-mails, and

the front-desk clerk or the hotel’s registration e-mail messages opens up a rich avenue of future

form could explicitly ask guests whether they research possibilities. The costs are minimal, and

would like to receive future e-mails. Addition- the overall results can be positive. Ultimately, this

ally, the hotel could target its most loyal custom- hotel’s permission e-mail marketing campaign

ers with a preliminary direct-mail campaign, could be deemed successful in that it generated a

alerting them to future e-mails. greater response percentage than regular direct-

This finding highlights the need for research mail usually draws (9 percent versus 2 percent,

that compares responses to proactive campaigns at best). It’s also promising that all but ten of the

involving opt-in permission to those with a reac- 492 e-mail recipients chose to remain on the

tive opt-out approach. We wonder whether cus- hotel’s e-mail database—meaning that they are

tomers would be more receptive to personalized available for future promotional efforts.

sales approaches if they were given the chance to One practical benefit is that the hotel’s experi-

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on November 7, 2015

68 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly FEBRUARY 2002

PERMISSION E-MAIL MARKETING

ment highlights the need to train front-desk clerks

and other personnel involved in sending the pro-

motional messages. Harking back to our point

about making sure e-mail addresses are clean, the

hotel conducted a short seminar with the em-

ployees responsible for collecting or using e-mail

addresses after the e-mail experiment and found

ways to improve the e-mail database. For ex-

ample, several clerks assumed that an e-mail ad-

dress is similar to a surface-mail address in that a

typo will not keep it from being delivered. Simi-

larly, some of the employees did not realize that

e-mail addresses cannot contain spaces.

This work is limited in that the test included

only two variables—personalization and subject-

line relevance—and one medium. Future research

should consider exploring other media such as

mobile phones,22 as well as a fuller range of vari-

ables that could boost the effectiveness of a per-

mission e-mail marketing campaign. Such vari-

ables could include subject-line copy, the e-mails

“From:” field, the actual e-mail message, plain

text versus html e-mail format, the salutation

used, time of day, day of week, frequency of mail-

ings, and the message’s closing line. ■

22

P. Barwise and C. Strong, “Permission-based Mobile

Advertising,” Journal of Interactive Marketing, Vol. 16, No.

1 (Winter 2002), pp. 14–25.

Ana Marinova (above, left), the public-relations and marketing director for a major

Perth hotel (amarinova2000@yahoo.com.au), recently finished her master’s degree at

the University of Western Australia, where Jamie Murphy, Ph.D. (middle photo), is an

associate professor (jmurphy@ecel.uwa.edu.au). Brian L. Massey, Ph.D. (above, right),

is an assistant professor at the University of Utah (brian.massey@ utah.edu).

© 2002, Cornell University; an invited paper.

Downloaded from cqx.sagepub.com at East Carolina University on November 7, 2015

FEBRUARY 2002 Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 69

You might also like

- IMPLEMENTATION OF RED (Right Execution Daily)Document14 pagesIMPLEMENTATION OF RED (Right Execution Daily)chandooooo80% (5)

- CH 14 CSR: Review QuestionsDocument6 pagesCH 14 CSR: Review Questionsshahin317100% (1)

- The Marketing Audit: The Hidden Link between Customer Engagement and Sustainable Revenue GrowthFrom EverandThe Marketing Audit: The Hidden Link between Customer Engagement and Sustainable Revenue GrowthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- B2B Marketing 123: A 3 Step Approach for Marketing to BusinessesFrom EverandB2B Marketing 123: A 3 Step Approach for Marketing to BusinessesNo ratings yet

- Sandeep Garg Microeconomics Class 12Document5 pagesSandeep Garg Microeconomics Class 12Geetika Khandelwal0% (8)

- Brand Equity ModelDocument86 pagesBrand Equity ModelYash Vora100% (1)

- Marketing Plan MymuesliDocument15 pagesMarketing Plan Mymuesliapi-272376841100% (1)

- Testing The Dimensionality of Consumer Ethnocentrism Scale (CETSCALE) Among A Young Malaysian Consumer Market SegmentDocument12 pagesTesting The Dimensionality of Consumer Ethnocentrism Scale (CETSCALE) Among A Young Malaysian Consumer Market SegmentmibpurvNo ratings yet

- Final Edelman Trust Barometer Case StudyDocument7 pagesFinal Edelman Trust Barometer Case Studyapi-293119969No ratings yet

- SWOT SapphireDocument4 pagesSWOT SapphireVikash Kumar50% (2)

- Whitepaper ERFM SG English 1Document16 pagesWhitepaper ERFM SG English 1Iago MacedoNo ratings yet

- 02 Midterm Module For Business MarketingDocument36 pages02 Midterm Module For Business MarketingMyren Ubay SerondoNo ratings yet

- Unit-5: Managing Relationship and Building Loyalty: Service Marketing, MKT 541Document7 pagesUnit-5: Managing Relationship and Building Loyalty: Service Marketing, MKT 541Umesh kathariyaNo ratings yet

- Midterm Module 2023Document32 pagesMidterm Module 2023Jocelyn Mae CabreraNo ratings yet

- Trust and Customer Willingness PDFDocument15 pagesTrust and Customer Willingness PDFMedi RaghuNo ratings yet

- Direct Marketing 4Document39 pagesDirect Marketing 4International Conference and Research PresentationNo ratings yet

- Assignment OF Customer Relationship Management: Submitted To-M/S Kuljeet MinhasDocument6 pagesAssignment OF Customer Relationship Management: Submitted To-M/S Kuljeet MinhasPrashantNo ratings yet

- B2B Marketing ToolkitDocument8 pagesB2B Marketing ToolkitJgjbfhbbgbNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 and 2Document12 pagesLecture 1 and 2Ali RazaNo ratings yet

- Customer Profiling in E-Commerce: Methodological Aspects and ChallengesDocument15 pagesCustomer Profiling in E-Commerce: Methodological Aspects and ChallengesNi Putu Agustin PutrianiNo ratings yet

- 6 Tips To Turn Messaging Into A High-Converting Channel: 6.5 Billion SmartphonesDocument5 pages6 Tips To Turn Messaging Into A High-Converting Channel: 6.5 Billion Smartphonesmasterdoctor.clinicNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3 DDMDocument21 pagesLecture 3 DDMKomal KhanNo ratings yet

- CRM in Private BanksDocument27 pagesCRM in Private BanksManuKingKaushik67% (3)

- Semalt TipsDocument3 pagesSemalt TipsAnita AnisimovaNo ratings yet

- Is Likewise Helps in Securing New Clients or Persuading Current Clients To BuyDocument3 pagesIs Likewise Helps in Securing New Clients or Persuading Current Clients To BuyMerry Jane SP QuiatchonNo ratings yet

- Mr. Anand Chauhan Arpit Assistant Professor 12001432008 MBA-5 Year, 9 SemesterDocument12 pagesMr. Anand Chauhan Arpit Assistant Professor 12001432008 MBA-5 Year, 9 Semestervikki059No ratings yet

- Bridging The Map Marketing Commerce WP OracleDocument6 pagesBridging The Map Marketing Commerce WP OraclePaul NewportNo ratings yet

- DR SanjayBhayaniDr NishantVachhani PDFDocument12 pagesDR SanjayBhayaniDr NishantVachhani PDFvishiNo ratings yet

- Customer Retention Loyalty R FludgateDocument12 pagesCustomer Retention Loyalty R FludgateViCky PhangNo ratings yet

- Papers An Evaluation of E-Mail Marketing and Factors Affecting ResponseDocument15 pagesPapers An Evaluation of E-Mail Marketing and Factors Affecting ResponseGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Managing Personal CommunicationDocument16 pagesManaging Personal CommunicationJosefina CadizNo ratings yet

- Direct: MarketingDocument32 pagesDirect: MarketingMahnoor baqaiNo ratings yet

- Is Your Marketing ReadyDocument19 pagesIs Your Marketing ReadyPedro AlexandreNo ratings yet

- The Changing The Nature of The Customer RelationshipDocument20 pagesThe Changing The Nature of The Customer RelationshipBrazil offshore jobsNo ratings yet

- 4 Strategies For Successful Text MarketingDocument24 pages4 Strategies For Successful Text MarketingElenaAristarhova100% (1)

- Relationship MarketingDocument241 pagesRelationship MarketingNishant Kumar100% (1)

- Chapter Four: E-Commerce Marketing ConceptsDocument28 pagesChapter Four: E-Commerce Marketing ConceptsHK GalgeloNo ratings yet

- Business Marketing Module 2Document19 pagesBusiness Marketing Module 2Ericka Marie Almado100% (1)

- Research Note: Customer Intimacy and Cross-Selling Strategy: Management ScienceDocument7 pagesResearch Note: Customer Intimacy and Cross-Selling Strategy: Management ScienceHải YếnNo ratings yet

- Ailsa Kolsaker and Claire Payne 2002 Engendering Trust in E-Commerce A Study in Gender Base ConceptDocument9 pagesAilsa Kolsaker and Claire Payne 2002 Engendering Trust in E-Commerce A Study in Gender Base ConceptRen SuzakuNo ratings yet

- CRM in Private BanksDocument27 pagesCRM in Private BanksAbisha JohnNo ratings yet

- Ebusiness Article June 2014Document2 pagesEbusiness Article June 2014Pushpender SinghNo ratings yet

- Do Customer Loyalty Programs Really WorkDocument17 pagesDo Customer Loyalty Programs Really WorkUtkrisht Kumar ShandilyaNo ratings yet

- A Study of Online Marketing On Traditional MarketingDocument11 pagesA Study of Online Marketing On Traditional Marketingsonukrisani894No ratings yet

- Relationship MarketingDocument16 pagesRelationship MarketingVansh Raj YadavNo ratings yet

- Business Marketing Module 2Document26 pagesBusiness Marketing Module 2Janelle RiveraNo ratings yet

- Five Principles Dynamic MarketingDocument17 pagesFive Principles Dynamic MarketingOctober FansNo ratings yet

- Digital MarketingDocument105 pagesDigital MarketingSaran Kutty100% (2)

- Sample For Design and Develop An Integrated Marketing Communication PlanDocument30 pagesSample For Design and Develop An Integrated Marketing Communication PlanMuzammil AtiqueNo ratings yet

- Study Copy Relationship ManagementDocument7 pagesStudy Copy Relationship ManagementAngelo MedinaNo ratings yet

- Loyalty White Paper - FINALDocument16 pagesLoyalty White Paper - FINALvilmaNo ratings yet

- Direct MarketingDocument13 pagesDirect Marketingmukund shaNo ratings yet

- The FMCG Identity Crisis PDFDocument23 pagesThe FMCG Identity Crisis PDFAnonymous rjJZ8sSijNo ratings yet

- The Impact of CRM 2.0 On Customer InsightDocument11 pagesThe Impact of CRM 2.0 On Customer InsightNur Fitriah Ayuning BudiNo ratings yet

- Personalizing The Customer Experience Driving Differentiation in RetailDocument7 pagesPersonalizing The Customer Experience Driving Differentiation in RetailsyuglobaltvNo ratings yet

- How Customer Referral Programs Turn Social Capital Into Economic CapitalDocument15 pagesHow Customer Referral Programs Turn Social Capital Into Economic CapitalAmr ShakerNo ratings yet

- Relationship Marketing 3.0: Thriving in Marketing's New EcosystemDocument11 pagesRelationship Marketing 3.0: Thriving in Marketing's New EcosystemShanti PutriNo ratings yet

- 9-Habits of Leading Customer Feedback ManagersDocument5 pages9-Habits of Leading Customer Feedback ManagersAshish KumarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - 5Document42 pagesChapter 6 - 5berkNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE)Document6 pagesInternational Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE)salimNo ratings yet

- Q3 - Principles of Marketing - Week 3Document4 pagesQ3 - Principles of Marketing - Week 3Glaiza Perez100% (1)

- The Impact of Online Marketing On CustomDocument156 pagesThe Impact of Online Marketing On CustomEzatullah Siddiqi100% (2)

- Advantages of Marketing Communication MixDocument2 pagesAdvantages of Marketing Communication MixftjytrjyjNo ratings yet

- A Study On Database Marketing: Subject: Advertisement ManagementDocument26 pagesA Study On Database Marketing: Subject: Advertisement ManagementVivek RanaNo ratings yet

- Art of B2B MarketingDocument12 pagesArt of B2B MarketingROHIT DSUZANo ratings yet

- Don't Just Relate - Advocate (Review and Analysis of Urban's Book)From EverandDon't Just Relate - Advocate (Review and Analysis of Urban's Book)No ratings yet

- Competitions:: Legal Aspects of Coronavirus PandemicDocument3 pagesCompetitions:: Legal Aspects of Coronavirus PandemicGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Amity Online Constitutional Law QuizDocument3 pagesAmity Online Constitutional Law QuizGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Esomar Guideline For Online Research: World Research Codes and GuidelinesDocument23 pagesEsomar Guideline For Online Research: World Research Codes and GuidelinesGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Nlu Odisha:: 1 Harsh Mander & Anr. Versus Union of IndiaDocument7 pagesNlu Odisha:: 1 Harsh Mander & Anr. Versus Union of IndiaGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 and Its Impact On The International EconomyDocument17 pagesCOVID-19 and Its Impact On The International EconomyGeetika Khandelwal100% (7)

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. International Journal of Electronic CommerceDocument30 pagesTaylor & Francis, Ltd. International Journal of Electronic CommerceGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Guide To Understand An Offer Document: (WWW - Sebi.gov - In)Document5 pagesGuide To Understand An Offer Document: (WWW - Sebi.gov - In)Geetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- FSI Briefs: Expected Loss Provisioning Under A Global PandemicDocument9 pagesFSI Briefs: Expected Loss Provisioning Under A Global PandemicGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Center On Budget and Policy Priorities: This Content Downloaded From 14.139.214.181 On Thu, 07 May 2020 12:06:45 UTCDocument20 pagesCenter On Budget and Policy Priorities: This Content Downloaded From 14.139.214.181 On Thu, 07 May 2020 12:06:45 UTCGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Work860 PDFDocument61 pagesWork860 PDFGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- 3ludhiana Hand Tools Association PetitionDocument100 pages3ludhiana Hand Tools Association PetitionGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Signature Not VerifiedDocument1 pageSignature Not VerifiedGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- BIS Bulletin: Macroeconomic Effects of Covid-19: An Early ReviewDocument9 pagesBIS Bulletin: Macroeconomic Effects of Covid-19: An Early ReviewGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Companies Challenge To MHA OrderDocument2 pagesCompanies Challenge To MHA OrderGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Harsh Mander Vs UOI 07 04 2020Document1 pageHarsh Mander Vs UOI 07 04 2020Geetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Rajasthan Industry Group Order Part 1Document1 pageRajasthan Industry Group Order Part 1Geetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

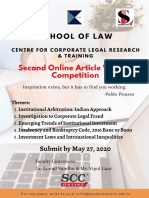

- School of Law: Centre For Corporate Legal Research & TrainingDocument4 pagesSchool of Law: Centre For Corporate Legal Research & TrainingGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Synopsis and List of DatesDocument20 pagesSynopsis and List of DatesGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Vyas Thesis Promowithch.1 PDFDocument29 pagesVyas Thesis Promowithch.1 PDFGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- 1 L A C P: Centre FOR Disaster Management AND LAWDocument5 pages1 L A C P: Centre FOR Disaster Management AND LAWGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- 6nagrika Export LTD Writ Petition Vs Union of IndiaDocument93 pages6nagrika Export LTD Writ Petition Vs Union of IndiaGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Permission-Based Mobile AdDocument15 pagesThe Impact of Permission-Based Mobile AdGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- MB Confront Coronavirus Catastrophe Public Health Plan 300320 enDocument10 pagesMB Confront Coronavirus Catastrophe Public Health Plan 300320 enGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Permission Masrketing 4 PDFDocument18 pagesPermission Masrketing 4 PDFGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Papers An Evaluation of E-Mail Marketing and Factors Affecting ResponseDocument15 pagesPapers An Evaluation of E-Mail Marketing and Factors Affecting ResponseGeetika KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Igcse: Mark Scheme Maximum Mark: 100Document5 pagesIgcse: Mark Scheme Maximum Mark: 100Azul IrlaundeNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Persepsi Kualitas Dan Citra Merek Terhadap Loyalitas Pelanggan Dimediasi Kepercayaan Dan Kepuasan PelangganDocument10 pagesPengaruh Persepsi Kualitas Dan Citra Merek Terhadap Loyalitas Pelanggan Dimediasi Kepercayaan Dan Kepuasan PelangganNelly RNo ratings yet

- A Study On Customer Preference of Adidas With Special Reference To Sports ShoesDocument49 pagesA Study On Customer Preference of Adidas With Special Reference To Sports Shoesakshay gangwani100% (1)

- Nectar BrochureDocument64 pagesNectar Brochurekishore13No ratings yet

- Visitor Attraction ProductDocument30 pagesVisitor Attraction ProductparawayNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Common Business Terminologies PDFDocument30 pagesChapter 6 Common Business Terminologies PDFDiya SardaNo ratings yet

- SANSDC Funding Proposal JulyDocument15 pagesSANSDC Funding Proposal JulyAhmad MuzammilNo ratings yet

- Social Media AssignmentDocument21 pagesSocial Media AssignmentBrysonNo ratings yet

- SachinDocument43 pagesSachinsachin patraNo ratings yet

- NTCC Summer Internship Report SAMPLEDocument47 pagesNTCC Summer Internship Report SAMPLESushant ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Syska Led-1Document9 pagesSyska Led-1Vijay AroraNo ratings yet

- Product Place Price Promotion People Packaging and PositioningDocument4 pagesProduct Place Price Promotion People Packaging and PositioningDimple MontemayorNo ratings yet

- A PR Study GuideDocument150 pagesA PR Study GuideDenise EmbonNo ratings yet

- PAK MCQS MarketingDocument4 pagesPAK MCQS MarketingsadqmNo ratings yet

- Brand ZZZZDocument6 pagesBrand ZZZZSurag VsNo ratings yet

- McDonald's France en CaseStudyDocument3 pagesMcDonald's France en CaseStudyVivek KumarNo ratings yet

- Sales Management ReportDocument23 pagesSales Management ReportSampath PereraNo ratings yet

- Key Partners Key Activities Value Proposition Customer Relationships Customer SegmentsDocument1 pageKey Partners Key Activities Value Proposition Customer Relationships Customer SegmentsSudipto Tahsin AurnabNo ratings yet

- Non-Aviation Business 393Document13 pagesNon-Aviation Business 393keen writerNo ratings yet

- 140390068XDocument63 pages140390068Xbublooo123No ratings yet

- Internship Report: Daffodil International UniversityDocument35 pagesInternship Report: Daffodil International UniversityTechHub BDNo ratings yet

- Reckitt Benckiser - Harpic CaseDocument23 pagesReckitt Benckiser - Harpic Casemanjul201050% (2)

- A Case Study of Consumer Satisfaction of KentuckyDocument15 pagesA Case Study of Consumer Satisfaction of KentuckyMuqadas JunejoNo ratings yet

- BLP Marketing ProjectDocument32 pagesBLP Marketing ProjectAneesh GondhalekarNo ratings yet