Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Modern Film Franchises Market-Researched Audience-Tested

Modern Film Franchises Market-Researched Audience-Tested

Uploaded by

AndyGladbachCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- 2 Michel Thomas Spanish AdvancedDocument48 pages2 Michel Thomas Spanish Advancedsanjacarica100% (2)

- Horror Films FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Slashers, Vampires, Zombies, Aliens and MoreFrom EverandHorror Films FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Slashers, Vampires, Zombies, Aliens and MoreRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Div ClassDocument3 pagesDiv Classapi-302656741No ratings yet

- The 100 Movies That Get No Respect: An Analysis and Evaluation of the Most Underrated Films of All TimeFrom EverandThe 100 Movies That Get No Respect: An Analysis and Evaluation of the Most Underrated Films of All TimeNo ratings yet

- The Western Film Review: A Second Look at Some Popular Western MoviesFrom EverandThe Western Film Review: A Second Look at Some Popular Western MoviesNo ratings yet

- Horror As A GenreDocument7 pagesHorror As A Genreapi-636571933No ratings yet

- The Kubrick Site - Comments by Kubrick On FilmDocument4 pagesThe Kubrick Site - Comments by Kubrick On FilmDukeStrangeloveNo ratings yet

- The Metaphoric Quasi Gonzo Pre FinaleDocument13 pagesThe Metaphoric Quasi Gonzo Pre FinaleTiphani LawNo ratings yet

- A Year at the Movies: One Man's Filmgoing OdysseyFrom EverandA Year at the Movies: One Man's Filmgoing OdysseyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (87)

- Hugo As Similar Examples of Which Michel Hazanavicius's The Artist Could RestDocument3 pagesHugo As Similar Examples of Which Michel Hazanavicius's The Artist Could RestJason ShanerNo ratings yet

- Thoughts On The Philosophy of Filmmaking, With Too Many Digressions and Avatar ReferencesDocument5 pagesThoughts On The Philosophy of Filmmaking, With Too Many Digressions and Avatar Referencesjorthwein1No ratings yet

- Questionnaire DataDocument10 pagesQuestionnaire DataSeemaEmmaNo ratings yet

- The Best Film You've Never Seen: 35 Directors Champion the Forgotten or Critically Savaged Movies They LoveFrom EverandThe Best Film You've Never Seen: 35 Directors Champion the Forgotten or Critically Savaged Movies They LoveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Homework 2.5 Mauricio PiedraDocument4 pagesHomework 2.5 Mauricio PiedraMauricio PiedraNo ratings yet

- Queued!: The Best and Worst of Netflix in 101 Independent Movie Reviews, Vol. 2From EverandQueued!: The Best and Worst of Netflix in 101 Independent Movie Reviews, Vol. 2No ratings yet

- "What Do You Mean, Murder?" Clue and the Making of a Cult ClassicFrom Everand"What Do You Mean, Murder?" Clue and the Making of a Cult ClassicNo ratings yet

- Flix You Missed: More Than 100 Movies from the Past Ten Years You (Probably) Didn’T See!From EverandFlix You Missed: More Than 100 Movies from the Past Ten Years You (Probably) Didn’T See!No ratings yet

- Your Next Favorite Movie, Vol. 1: 100+ Quick Movie Review To Help You Find Your Next Favorite Fast!: Your Next Favorite Movie, #1From EverandYour Next Favorite Movie, Vol. 1: 100+ Quick Movie Review To Help You Find Your Next Favorite Fast!: Your Next Favorite Movie, #1No ratings yet

- Moviebob's Game Overthinker & Beyond: The Video Game Writing of Bob ChipmanFrom EverandMoviebob's Game Overthinker & Beyond: The Video Game Writing of Bob ChipmanNo ratings yet

- The Return of The Silent Films?: TobeornottobeDocument4 pagesThe Return of The Silent Films?: TobeornottobeJason TanNo ratings yet

- The Hollywood H.I.P.* List: 100 Lame and Laughable Scenes in Movieland That Cling to Cinematic Life Like a Big-Screen Bad Guy Who Just Won’t Die!From EverandThe Hollywood H.I.P.* List: 100 Lame and Laughable Scenes in Movieland That Cling to Cinematic Life Like a Big-Screen Bad Guy Who Just Won’t Die!No ratings yet

- Reading the Silver Screen: A Film Lover's Guide to Decoding the Art Form That MovesFrom EverandReading the Silver Screen: A Film Lover's Guide to Decoding the Art Form That MovesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Film Philosophy Reflexive Journal Word DocumentDocument11 pagesFilm Philosophy Reflexive Journal Word DocumentMaría Victoria LondoñoNo ratings yet

- Pratt Essay 5Document4 pagesPratt Essay 5princesssaricka4No ratings yet

- The Worst We Can Find: MST3K, RiffTrax, and the History of Heckling at the MoviesFrom EverandThe Worst We Can Find: MST3K, RiffTrax, and the History of Heckling at the MoviesNo ratings yet

- Christopher McQuarrie Creative Screenwriting InterviewDocument10 pagesChristopher McQuarrie Creative Screenwriting InterviewMatt JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Killer B's: The 237 Best Movies on Video You've (Probably) Never SeenFrom EverandKiller B's: The 237 Best Movies on Video You've (Probably) Never SeenNo ratings yet

- So Bad, It's Good: More Than 50 Great Films for Your Bad Movie NightFrom EverandSo Bad, It's Good: More Than 50 Great Films for Your Bad Movie NightRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Nicolas Cage On Acting, Philosophy and Searching For The Holy Grail - The New York TimesDocument13 pagesNicolas Cage On Acting, Philosophy and Searching For The Holy Grail - The New York Timesemanala2015No ratings yet

- GoncharovDocument10 pagesGoncharovjust meNo ratings yet

- The Good, the Bad and the Godawful: 21st-Century Movie ReviewsFrom EverandThe Good, the Bad and the Godawful: 21st-Century Movie ReviewsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Get the Picture?: The Movie Lover's Guide to Watching FilmsFrom EverandGet the Picture?: The Movie Lover's Guide to Watching FilmsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (6)

- The Comedy Film Nerds Guide to Movies: Featuring Dave Anthony, Lord Carrett, Dean Haglund, Allan Havey, Laura House, Jackie Kashian, Suzy Nakamura, Greg ... Schmidt, Neil T. Weakley, and Matt WeinholdFrom EverandThe Comedy Film Nerds Guide to Movies: Featuring Dave Anthony, Lord Carrett, Dean Haglund, Allan Havey, Laura House, Jackie Kashian, Suzy Nakamura, Greg ... Schmidt, Neil T. Weakley, and Matt WeinholdNo ratings yet

- Leonard Maltin's 151 Best Movies You've Never SeenFrom EverandLeonard Maltin's 151 Best Movies You've Never SeenRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (16)

- Secrets of Breaking into the Film and TV Business: Tools and Tricks for Today's Directors, Writers, and ActorsFrom EverandSecrets of Breaking into the Film and TV Business: Tools and Tricks for Today's Directors, Writers, and ActorsNo ratings yet

- Science Fiction FilmsDocument5 pagesScience Fiction Filmsapi-483055750No ratings yet

- Save The Cat!: The Last Book On Screenwriting You'll Ever NeedDocument23 pagesSave The Cat!: The Last Book On Screenwriting You'll Ever NeedRis IgrecNo ratings yet

- Shutter Island Movie Review Martin HoodDocument5 pagesShutter Island Movie Review Martin HoodMartin HoodNo ratings yet

- Identity 2003: Like A Hit To The Head From Left FieldDocument20 pagesIdentity 2003: Like A Hit To The Head From Left FieldStefan TecliciNo ratings yet

- Back To The Future Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesBack To The Future Reaction PaperChelsy SantosNo ratings yet

- Moviebob's Strange Hollywood: Bob Chipman On the Movie BusinessFrom EverandMoviebob's Strange Hollywood: Bob Chipman On the Movie BusinessNo ratings yet

- New Script For PitchDocument5 pagesNew Script For Pitchapi-477398135No ratings yet

- Reel Life 101: 1,101 Classic Movie Lines That Teach Us About Life, Death, Love, Marriage, Anger and HumorFrom EverandReel Life 101: 1,101 Classic Movie Lines That Teach Us About Life, Death, Love, Marriage, Anger and HumorNo ratings yet

- The Princess Bride Movie Review - NishanthDocument2 pagesThe Princess Bride Movie Review - NishanthNishanth VNo ratings yet

- Nightmare Fuel: The Science of Horror FilmsFrom EverandNightmare Fuel: The Science of Horror FilmsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (11)

- Top Movie ReviewsDocument12 pagesTop Movie Reviewstovvovmpd100% (1)

- Articles Articles Articles Articles: "Watching The Lord of The Rings" by Christopher VoglerDocument20 pagesArticles Articles Articles Articles: "Watching The Lord of The Rings" by Christopher VoglersjstheesarNo ratings yet

- The Film I LikeDocument6 pagesThe Film I LikeArdhi Wanto FransiusNo ratings yet

- Strange Attractor and Beachcombing BY Terry RossioDocument10 pagesStrange Attractor and Beachcombing BY Terry RossioscoopercontactoNo ratings yet

- BOXedMAN: I'm Going To Make A Movie - Why Are You Laughing?From EverandBOXedMAN: I'm Going To Make A Movie - Why Are You Laughing?No ratings yet

- (123movies) Watch Eternals (2021) Full English Movies HDDocument23 pages(123movies) Watch Eternals (2021) Full English Movies HDDwayne HarrisonNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document42 pagesModule 2miles razorNo ratings yet

- HahayysDocument30 pagesHahayys2BGrp3Plaza, Anna MaeNo ratings yet

- KunalDocument5 pagesKunalPratik PawarNo ratings yet

- Various Artists - The Joy of ClassicsDocument82 pagesVarious Artists - The Joy of ClassicsCarlos Toledo88% (16)

- Proforma Invoice: TOTAL:300000 Meters $3,900,000Document3 pagesProforma Invoice: TOTAL:300000 Meters $3,900,000Eslam A. AliNo ratings yet

- PESO PPA Feedback FormDocument2 pagesPESO PPA Feedback FormJover MarilouNo ratings yet

- Guaranty and Suretyship CasesDocument82 pagesGuaranty and Suretyship Cases001nooneNo ratings yet

- Pediatric OrthopaedicDocument66 pagesPediatric OrthopaedicDhito RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Lataif, Exert Tafseer by Al QushayriDocument16 pagesLataif, Exert Tafseer by Al Qushayrimadanuodad100% (1)

- International Primary Curriculum SAM Science Booklet 2012Document44 pagesInternational Primary Curriculum SAM Science Booklet 2012Rere Jasdijf100% (1)

- OO ALV Status Led LightDocument6 pagesOO ALV Status Led LightRam PraneethNo ratings yet

- Dungeoncraft Wild Beyond The Witchlight v1.1Document9 pagesDungeoncraft Wild Beyond The Witchlight v1.1RalphNo ratings yet

- ASD PEDS Administration GuidelinesDocument5 pagesASD PEDS Administration GuidelinesInes Arias PazNo ratings yet

- Annex B - Intake Sheet FinalDocument2 pagesAnnex B - Intake Sheet FinalCherry May Logdat-NgNo ratings yet

- Novello's Catalogue of Orchestral MusicDocument212 pagesNovello's Catalogue of Orchestral MusicAnte B.K.No ratings yet

- Masterlist - Course - Offerings - 2024 (As at 18 July 2023)Document3 pagesMasterlist - Course - Offerings - 2024 (As at 18 July 2023)limyihang17No ratings yet

- Fadi CV 030309Document5 pagesFadi CV 030309fkhaterNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 Skeletal System Enhanced SciDocument126 pagesGrade 8 Skeletal System Enhanced SciCin TooNo ratings yet

- Annex VI - Final Narrative ReportDocument4 pagesAnnex VI - Final Narrative ReporttijanagruNo ratings yet

- Tve 8 Shielded Metal Arc WeldingDocument11 pagesTve 8 Shielded Metal Arc WeldingJOHN ALFRED MANANGGITNo ratings yet

- 4 Step Formula For A Killer IntroductionDocument8 pages4 Step Formula For A Killer IntroductionSHARMINE CABUSASNo ratings yet

- Scopes of Marketing AssignmentDocument4 pagesScopes of Marketing AssignmentKhira Xandria AldabaNo ratings yet

- Abhinavagupta (C. 950 - 1016 CEDocument8 pagesAbhinavagupta (C. 950 - 1016 CEthewitness3No ratings yet

- For StatDocument47 pagesFor StatLyn VeaNo ratings yet

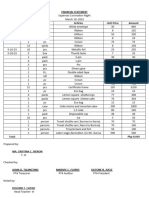

- Financial Statement Coronation NightDocument8 pagesFinancial Statement Coronation NightRuel Gapuz ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Brake Valves: Z279180 Z101197 Z289395 Z102626 (ZRL3518JC02)Document5 pagesBrake Valves: Z279180 Z101197 Z289395 Z102626 (ZRL3518JC02)houssem houssemNo ratings yet

- Mathematics: Quarter 3 - Module 5: Independent & Dependent EventsDocument19 pagesMathematics: Quarter 3 - Module 5: Independent & Dependent EventsAlexis Jon NaingueNo ratings yet

- Ahnan-Winarno Et Al. (2020) Tempeh - A Semicentennial ReviewDocument52 pagesAhnan-Winarno Et Al. (2020) Tempeh - A Semicentennial ReviewTahir AliNo ratings yet

- Brigada Solicitation and InvitationDocument3 pagesBrigada Solicitation and Invitationguendolyn templadoNo ratings yet

Modern Film Franchises Market-Researched Audience-Tested

Modern Film Franchises Market-Researched Audience-Tested

Uploaded by

AndyGladbachOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Modern Film Franchises Market-Researched Audience-Tested

Modern Film Franchises Market-Researched Audience-Tested

Uploaded by

AndyGladbachCopyright:

Available Formats

And in a way, certain Hitchcock films were also like theme parks.

I’m thinking of “Strangers on a Train,”

in which the climax takes place on a merry-go-round at a real amusement park, and “Psycho,” which I

saw at a midnight show on its opening day, an experience I will never forget. People went to be

surprised and thrilled, and they weren’t disappointed.

Sixty or 70 years later, we’re still watching those pictures and marveling at them. But is it the thrills and

the shocks that we keep going back to? I don’t think so. The set pieces in “North by Northwest” are

stunning, but they would be nothing more than a succession of dynamic and elegant compositions and

cuts without the painful emotions at the center of the story or the absolute lostness of Cary Grant’s

character.

The climax of “Strangers on a Train” is a feat, but it’s the interplay between the two principal characters

and Robert Walker’s profoundly unsettling performance that resonate now.

Some say that Hitchcock’s pictures had a sameness to them, and perhaps that’s true — Hitchcock

himself wondered about it. But the sameness of today’s franchise pictures is something else again.

Many of the elements that define cinema as I know it are there in Marvel pictures. What’s not there is

revelation, mystery or genuine emotional danger. Nothing is at risk. The pictures are made to satisfy a

specific set of demands, and they are designed as variations on a finite number of themes.

They are sequels in name but they are remakes in spirit, and everything in them is officially sanctioned

because it can’t really be any other way. That’s the nature of modern film franchises: market-

researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for

consumption.

Another way of putting it would be that they are everything that the films of Paul Thomas Anderson or

Claire Denis or Spike Lee or Ari Aster or Kathryn Bigelow or Wes Anderson are not. When I watch a

movie by any of those filmmakers, I know I’m going to see something absolutely new and be taken to

unexpected and maybe even unnameable areas of experience. My sense of what is possible in telling

stories with moving images and sounds is going to be expanded.

So, you might ask, what’s my problem? Why not just let superhero films and other franchise films be?

The reason is simple. In many places around this country and around the world, franchise films are now

your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen. It’s a perilous time in film

exhibition, and there are fewer independent theaters than ever. The equation has flipped and streaming

has become the primary delivery system. Still, I don’t know a single filmmaker who doesn’t want to

design films for the big screen, to be projected before audiences in theaters.

That includes me, and I’m speaking as someone who just completed a picture for Netflix. It, and it alone,

allowed us to make “The Irishman” the way we needed to, and for that I’ll always be thankful. We have

a theatrical window, which is great. Would I like the picture to play on more big screens for longer

periods of time? Of course I would. But no matter whom you make your movie with, the fact is that the

screens in most multiplexes are crowded with franchise pictures.

And if you’re going to tell me that it’s simply a matter of supply and demand and giving the people what

they want, I’m going to disagree. It’s a chicken-and-egg issue. If people are given only one kind of thing

and endlessly sold only one kind of thing, of course they’re going to want more of that one kind of thing.

You might also like

- 2 Michel Thomas Spanish AdvancedDocument48 pages2 Michel Thomas Spanish Advancedsanjacarica100% (2)

- Horror Films FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Slashers, Vampires, Zombies, Aliens and MoreFrom EverandHorror Films FAQ: All That's Left to Know About Slashers, Vampires, Zombies, Aliens and MoreRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Div ClassDocument3 pagesDiv Classapi-302656741No ratings yet

- The 100 Movies That Get No Respect: An Analysis and Evaluation of the Most Underrated Films of All TimeFrom EverandThe 100 Movies That Get No Respect: An Analysis and Evaluation of the Most Underrated Films of All TimeNo ratings yet

- The Western Film Review: A Second Look at Some Popular Western MoviesFrom EverandThe Western Film Review: A Second Look at Some Popular Western MoviesNo ratings yet

- Horror As A GenreDocument7 pagesHorror As A Genreapi-636571933No ratings yet

- The Kubrick Site - Comments by Kubrick On FilmDocument4 pagesThe Kubrick Site - Comments by Kubrick On FilmDukeStrangeloveNo ratings yet

- The Metaphoric Quasi Gonzo Pre FinaleDocument13 pagesThe Metaphoric Quasi Gonzo Pre FinaleTiphani LawNo ratings yet

- A Year at the Movies: One Man's Filmgoing OdysseyFrom EverandA Year at the Movies: One Man's Filmgoing OdysseyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (87)

- Hugo As Similar Examples of Which Michel Hazanavicius's The Artist Could RestDocument3 pagesHugo As Similar Examples of Which Michel Hazanavicius's The Artist Could RestJason ShanerNo ratings yet

- Thoughts On The Philosophy of Filmmaking, With Too Many Digressions and Avatar ReferencesDocument5 pagesThoughts On The Philosophy of Filmmaking, With Too Many Digressions and Avatar Referencesjorthwein1No ratings yet

- Questionnaire DataDocument10 pagesQuestionnaire DataSeemaEmmaNo ratings yet

- The Best Film You've Never Seen: 35 Directors Champion the Forgotten or Critically Savaged Movies They LoveFrom EverandThe Best Film You've Never Seen: 35 Directors Champion the Forgotten or Critically Savaged Movies They LoveRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Homework 2.5 Mauricio PiedraDocument4 pagesHomework 2.5 Mauricio PiedraMauricio PiedraNo ratings yet

- Queued!: The Best and Worst of Netflix in 101 Independent Movie Reviews, Vol. 2From EverandQueued!: The Best and Worst of Netflix in 101 Independent Movie Reviews, Vol. 2No ratings yet

- "What Do You Mean, Murder?" Clue and the Making of a Cult ClassicFrom Everand"What Do You Mean, Murder?" Clue and the Making of a Cult ClassicNo ratings yet

- Flix You Missed: More Than 100 Movies from the Past Ten Years You (Probably) Didn’T See!From EverandFlix You Missed: More Than 100 Movies from the Past Ten Years You (Probably) Didn’T See!No ratings yet

- Your Next Favorite Movie, Vol. 1: 100+ Quick Movie Review To Help You Find Your Next Favorite Fast!: Your Next Favorite Movie, #1From EverandYour Next Favorite Movie, Vol. 1: 100+ Quick Movie Review To Help You Find Your Next Favorite Fast!: Your Next Favorite Movie, #1No ratings yet

- Moviebob's Game Overthinker & Beyond: The Video Game Writing of Bob ChipmanFrom EverandMoviebob's Game Overthinker & Beyond: The Video Game Writing of Bob ChipmanNo ratings yet

- The Return of The Silent Films?: TobeornottobeDocument4 pagesThe Return of The Silent Films?: TobeornottobeJason TanNo ratings yet

- The Hollywood H.I.P.* List: 100 Lame and Laughable Scenes in Movieland That Cling to Cinematic Life Like a Big-Screen Bad Guy Who Just Won’t Die!From EverandThe Hollywood H.I.P.* List: 100 Lame and Laughable Scenes in Movieland That Cling to Cinematic Life Like a Big-Screen Bad Guy Who Just Won’t Die!No ratings yet

- Reading the Silver Screen: A Film Lover's Guide to Decoding the Art Form That MovesFrom EverandReading the Silver Screen: A Film Lover's Guide to Decoding the Art Form That MovesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Film Philosophy Reflexive Journal Word DocumentDocument11 pagesFilm Philosophy Reflexive Journal Word DocumentMaría Victoria LondoñoNo ratings yet

- Pratt Essay 5Document4 pagesPratt Essay 5princesssaricka4No ratings yet

- The Worst We Can Find: MST3K, RiffTrax, and the History of Heckling at the MoviesFrom EverandThe Worst We Can Find: MST3K, RiffTrax, and the History of Heckling at the MoviesNo ratings yet

- Christopher McQuarrie Creative Screenwriting InterviewDocument10 pagesChristopher McQuarrie Creative Screenwriting InterviewMatt JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Killer B's: The 237 Best Movies on Video You've (Probably) Never SeenFrom EverandKiller B's: The 237 Best Movies on Video You've (Probably) Never SeenNo ratings yet

- So Bad, It's Good: More Than 50 Great Films for Your Bad Movie NightFrom EverandSo Bad, It's Good: More Than 50 Great Films for Your Bad Movie NightRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Nicolas Cage On Acting, Philosophy and Searching For The Holy Grail - The New York TimesDocument13 pagesNicolas Cage On Acting, Philosophy and Searching For The Holy Grail - The New York Timesemanala2015No ratings yet

- GoncharovDocument10 pagesGoncharovjust meNo ratings yet

- The Good, the Bad and the Godawful: 21st-Century Movie ReviewsFrom EverandThe Good, the Bad and the Godawful: 21st-Century Movie ReviewsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Get the Picture?: The Movie Lover's Guide to Watching FilmsFrom EverandGet the Picture?: The Movie Lover's Guide to Watching FilmsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (6)

- The Comedy Film Nerds Guide to Movies: Featuring Dave Anthony, Lord Carrett, Dean Haglund, Allan Havey, Laura House, Jackie Kashian, Suzy Nakamura, Greg ... Schmidt, Neil T. Weakley, and Matt WeinholdFrom EverandThe Comedy Film Nerds Guide to Movies: Featuring Dave Anthony, Lord Carrett, Dean Haglund, Allan Havey, Laura House, Jackie Kashian, Suzy Nakamura, Greg ... Schmidt, Neil T. Weakley, and Matt WeinholdNo ratings yet

- Leonard Maltin's 151 Best Movies You've Never SeenFrom EverandLeonard Maltin's 151 Best Movies You've Never SeenRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (16)

- Secrets of Breaking into the Film and TV Business: Tools and Tricks for Today's Directors, Writers, and ActorsFrom EverandSecrets of Breaking into the Film and TV Business: Tools and Tricks for Today's Directors, Writers, and ActorsNo ratings yet

- Science Fiction FilmsDocument5 pagesScience Fiction Filmsapi-483055750No ratings yet

- Save The Cat!: The Last Book On Screenwriting You'll Ever NeedDocument23 pagesSave The Cat!: The Last Book On Screenwriting You'll Ever NeedRis IgrecNo ratings yet

- Shutter Island Movie Review Martin HoodDocument5 pagesShutter Island Movie Review Martin HoodMartin HoodNo ratings yet

- Identity 2003: Like A Hit To The Head From Left FieldDocument20 pagesIdentity 2003: Like A Hit To The Head From Left FieldStefan TecliciNo ratings yet

- Back To The Future Reaction PaperDocument2 pagesBack To The Future Reaction PaperChelsy SantosNo ratings yet

- Moviebob's Strange Hollywood: Bob Chipman On the Movie BusinessFrom EverandMoviebob's Strange Hollywood: Bob Chipman On the Movie BusinessNo ratings yet

- New Script For PitchDocument5 pagesNew Script For Pitchapi-477398135No ratings yet

- Reel Life 101: 1,101 Classic Movie Lines That Teach Us About Life, Death, Love, Marriage, Anger and HumorFrom EverandReel Life 101: 1,101 Classic Movie Lines That Teach Us About Life, Death, Love, Marriage, Anger and HumorNo ratings yet

- The Princess Bride Movie Review - NishanthDocument2 pagesThe Princess Bride Movie Review - NishanthNishanth VNo ratings yet

- Nightmare Fuel: The Science of Horror FilmsFrom EverandNightmare Fuel: The Science of Horror FilmsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (11)

- Top Movie ReviewsDocument12 pagesTop Movie Reviewstovvovmpd100% (1)

- Articles Articles Articles Articles: "Watching The Lord of The Rings" by Christopher VoglerDocument20 pagesArticles Articles Articles Articles: "Watching The Lord of The Rings" by Christopher VoglersjstheesarNo ratings yet

- The Film I LikeDocument6 pagesThe Film I LikeArdhi Wanto FransiusNo ratings yet

- Strange Attractor and Beachcombing BY Terry RossioDocument10 pagesStrange Attractor and Beachcombing BY Terry RossioscoopercontactoNo ratings yet

- BOXedMAN: I'm Going To Make A Movie - Why Are You Laughing?From EverandBOXedMAN: I'm Going To Make A Movie - Why Are You Laughing?No ratings yet

- (123movies) Watch Eternals (2021) Full English Movies HDDocument23 pages(123movies) Watch Eternals (2021) Full English Movies HDDwayne HarrisonNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document42 pagesModule 2miles razorNo ratings yet

- HahayysDocument30 pagesHahayys2BGrp3Plaza, Anna MaeNo ratings yet

- KunalDocument5 pagesKunalPratik PawarNo ratings yet

- Various Artists - The Joy of ClassicsDocument82 pagesVarious Artists - The Joy of ClassicsCarlos Toledo88% (16)

- Proforma Invoice: TOTAL:300000 Meters $3,900,000Document3 pagesProforma Invoice: TOTAL:300000 Meters $3,900,000Eslam A. AliNo ratings yet

- PESO PPA Feedback FormDocument2 pagesPESO PPA Feedback FormJover MarilouNo ratings yet

- Guaranty and Suretyship CasesDocument82 pagesGuaranty and Suretyship Cases001nooneNo ratings yet

- Pediatric OrthopaedicDocument66 pagesPediatric OrthopaedicDhito RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Lataif, Exert Tafseer by Al QushayriDocument16 pagesLataif, Exert Tafseer by Al Qushayrimadanuodad100% (1)

- International Primary Curriculum SAM Science Booklet 2012Document44 pagesInternational Primary Curriculum SAM Science Booklet 2012Rere Jasdijf100% (1)

- OO ALV Status Led LightDocument6 pagesOO ALV Status Led LightRam PraneethNo ratings yet

- Dungeoncraft Wild Beyond The Witchlight v1.1Document9 pagesDungeoncraft Wild Beyond The Witchlight v1.1RalphNo ratings yet

- ASD PEDS Administration GuidelinesDocument5 pagesASD PEDS Administration GuidelinesInes Arias PazNo ratings yet

- Annex B - Intake Sheet FinalDocument2 pagesAnnex B - Intake Sheet FinalCherry May Logdat-NgNo ratings yet

- Novello's Catalogue of Orchestral MusicDocument212 pagesNovello's Catalogue of Orchestral MusicAnte B.K.No ratings yet

- Masterlist - Course - Offerings - 2024 (As at 18 July 2023)Document3 pagesMasterlist - Course - Offerings - 2024 (As at 18 July 2023)limyihang17No ratings yet

- Fadi CV 030309Document5 pagesFadi CV 030309fkhaterNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 Skeletal System Enhanced SciDocument126 pagesGrade 8 Skeletal System Enhanced SciCin TooNo ratings yet

- Annex VI - Final Narrative ReportDocument4 pagesAnnex VI - Final Narrative ReporttijanagruNo ratings yet

- Tve 8 Shielded Metal Arc WeldingDocument11 pagesTve 8 Shielded Metal Arc WeldingJOHN ALFRED MANANGGITNo ratings yet

- 4 Step Formula For A Killer IntroductionDocument8 pages4 Step Formula For A Killer IntroductionSHARMINE CABUSASNo ratings yet

- Scopes of Marketing AssignmentDocument4 pagesScopes of Marketing AssignmentKhira Xandria AldabaNo ratings yet

- Abhinavagupta (C. 950 - 1016 CEDocument8 pagesAbhinavagupta (C. 950 - 1016 CEthewitness3No ratings yet

- For StatDocument47 pagesFor StatLyn VeaNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement Coronation NightDocument8 pagesFinancial Statement Coronation NightRuel Gapuz ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Brake Valves: Z279180 Z101197 Z289395 Z102626 (ZRL3518JC02)Document5 pagesBrake Valves: Z279180 Z101197 Z289395 Z102626 (ZRL3518JC02)houssem houssemNo ratings yet

- Mathematics: Quarter 3 - Module 5: Independent & Dependent EventsDocument19 pagesMathematics: Quarter 3 - Module 5: Independent & Dependent EventsAlexis Jon NaingueNo ratings yet

- Ahnan-Winarno Et Al. (2020) Tempeh - A Semicentennial ReviewDocument52 pagesAhnan-Winarno Et Al. (2020) Tempeh - A Semicentennial ReviewTahir AliNo ratings yet

- Brigada Solicitation and InvitationDocument3 pagesBrigada Solicitation and Invitationguendolyn templadoNo ratings yet