Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Addressing Pediatric Intoeing in Primary Care

Addressing Pediatric Intoeing in Primary Care

Uploaded by

Abraham SaldañaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Nse 417 Midterm Evaluation Rosette LenonDocument7 pagesNse 417 Midterm Evaluation Rosette Lenonapi-341527743No ratings yet

- Heart & Neck Vessel AssessmentDocument46 pagesHeart & Neck Vessel AssessmentLouise Nathalia VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Placenta ChecklistDocument2 pagesPlacenta ChecklistNidhi Shivam Ahlawat100% (7)

- Pediatric Radiography - Merrills Atlas of Radiographic Positioning and ProceduresDocument61 pagesPediatric Radiography - Merrills Atlas of Radiographic Positioning and ProceduresJonald Pulgo IcoyNo ratings yet

- Influence of Maternal Educational Instruction On.9Document5 pagesInfluence of Maternal Educational Instruction On.9Tô ThuỷNo ratings yet

- Future of Early Intervention With Infants and Toddlers For Whom Typical Experiences Are Not EffectiveDocument6 pagesFuture of Early Intervention With Infants and Toddlers For Whom Typical Experiences Are Not EffectiveSaniNo ratings yet

- Advocating For The Child: The Role of Pediatric Psychology For Children With Cleft Lip And/or PalateDocument7 pagesAdvocating For The Child: The Role of Pediatric Psychology For Children With Cleft Lip And/or PalateeducacionchileNo ratings yet

- Dentists' Behavior Management As It Affects Com Pliance and Fear in Pediatric PatientsDocument7 pagesDentists' Behavior Management As It Affects Com Pliance and Fear in Pediatric PatientsyioulaNo ratings yet

- Imci Components of IMCI StrategyDocument12 pagesImci Components of IMCI StrategyPebbles PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Artikel LeukemiaDocument4 pagesArtikel LeukemiaHandian FINo ratings yet

- Self Assessment - Midterm 2016Document11 pagesSelf Assessment - Midterm 2016api-341527743No ratings yet

- Important Considerations in The Initial Clinical Evaluation of The Dysmorphic NeonateDocument5 pagesImportant Considerations in The Initial Clinical Evaluation of The Dysmorphic NeonateKaroo_123No ratings yet

- CHN Course PlanDocument29 pagesCHN Course PlanSathya PalanisamyNo ratings yet

- What Causes ADHD Understanding What Goes Wrong.16Document2 pagesWhat Causes ADHD Understanding What Goes Wrong.16FiegoParadaOrtizNo ratings yet

- First Experiences With Early Intervention: A National PerspectiveDocument12 pagesFirst Experiences With Early Intervention: A National PerspectiveSaniNo ratings yet

- Pediatric RadiographyDocument10 pagesPediatric RadiographyRachelle Danya Dela RosaNo ratings yet

- Home-Based DIR/Floortime Intervention Program For Preschool Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: Preliminary FindingsDocument12 pagesHome-Based DIR/Floortime Intervention Program For Preschool Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: Preliminary FindingsJoao ColomaNo ratings yet

- Bab I PDFDocument6 pagesBab I PDFAwliyana Risla PutriNo ratings yet

- Children For SurgeryDocument7 pagesChildren For SurgeryHany ElbarougyNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Toilet TrainingDocument4 pagesEvidence Based Toilet TrainingAhmad HaqulNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Parent Engagement in DIR/Floortime For Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument9 pagesFactors Associated With Parent Engagement in DIR/Floortime For Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderSantiagoDavidSuárezNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument34 pagesResearchIza MascariñasNo ratings yet

- NCP Deficient Knowledge of ROPDocument2 pagesNCP Deficient Knowledge of ROPMark Zedrix MediarioNo ratings yet

- Integrated Management of Childhood IllnessesDocument5 pagesIntegrated Management of Childhood IllnessesPamela Joy Rico UnayNo ratings yet

- Pedia 19Document6 pagesPedia 19Christopher ObedenciaNo ratings yet

- Community FNCPDocument7 pagesCommunity FNCPCarl Jefferson Pagulayan100% (1)

- BehGuid 1 Acceptance of Behavior Guidance Techniques Used in Pediatric Dentistry by Parents From Diverse BackgroundsDocument8 pagesBehGuid 1 Acceptance of Behavior Guidance Techniques Used in Pediatric Dentistry by Parents From Diverse BackgroundsAbdulmajeed alluqmaniNo ratings yet

- Anc 0000000000000030Document9 pagesAnc 0000000000000030maya amaliaNo ratings yet

- H. Nursing Care Plan: Altered Parenting RoleDocument2 pagesH. Nursing Care Plan: Altered Parenting RoleClovie ArsenalNo ratings yet

- Cordewener 2017Document7 pagesCordewener 2017patricia brucellariaNo ratings yet

- PQCNC New Initiative Proposal NASDocument9 pagesPQCNC New Initiative Proposal NASkcochranNo ratings yet

- CPG For Assessment of Children and AdolescentsDocument18 pagesCPG For Assessment of Children and AdolescentsSarwar BaigNo ratings yet

- MCHN Group2 NCP 2aDocument20 pagesMCHN Group2 NCP 2ajaytoo202020No ratings yet

- Coek - Info Dentofacial Orthopedics With Functional AppliancesDocument2 pagesCoek - Info Dentofacial Orthopedics With Functional ApplianceshabeebNo ratings yet

- Gpsych 2018 000009Document9 pagesGpsych 2018 000009Ana paula CamargoNo ratings yet

- 20-Appendices PeriodicitySchedule Bright FuturesDocument1 page20-Appendices PeriodicitySchedule Bright FuturesdrjohnckimNo ratings yet

- Archdischild 2019 316928Document5 pagesArchdischild 2019 316928Krit KritNo ratings yet

- Bonding 3Document2 pagesBonding 3mama adjoa atoquaye-quayeNo ratings yet

- Case Studies in Pediatric Anesthesia-4.preoperative - AnxietyDocument5 pagesCase Studies in Pediatric Anesthesia-4.preoperative - AnxietyismailcemNo ratings yet

- Poster RF - Adam Draft May 26Document1 pagePoster RF - Adam Draft May 26Adam SandowNo ratings yet

- Ongoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedDocument18 pagesOngoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Diarrhoea and Its Management Among Mothers of Under Five Children at UHTC Vijayapura: A Cross Sectional StudyDocument4 pagesKnowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Diarrhoea and Its Management Among Mothers of Under Five Children at UHTC Vijayapura: A Cross Sectional StudyAnisa SafutriNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Self-MutilationoutDocument6 pagesAdolescent Self-Mutilationoutclaudia mihaiNo ratings yet

- A Four Part Approach To Assessing Feeding.13Document2 pagesA Four Part Approach To Assessing Feeding.13Adhitya TaslimNo ratings yet

- Peds 2022057010Document23 pagesPeds 2022057010hb75289kyvNo ratings yet

- Working With Children in Humanitarian WASH ProgrammesDocument13 pagesWorking With Children in Humanitarian WASH ProgrammesOxfamNo ratings yet

- Early Detection of Developmental and Behavioral Problems: Pediatrics in Review September 2000Document10 pagesEarly Detection of Developmental and Behavioral Problems: Pediatrics in Review September 2000annaNo ratings yet

- Sample ChapterDocument11 pagesSample ChapterTales SoNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Nursing Procedure ManualDocument12 pagesPediatric Nursing Procedure ManualGopal Pandey100% (1)

- Tricking Kids Into The Perfect ExamDocument2 pagesTricking Kids Into The Perfect ExamLesterNo ratings yet

- NCLEX Practice Exam For Pediatric Nursing 2 - RNpediaDocument14 pagesNCLEX Practice Exam For Pediatric Nursing 2 - RNpediaLot Rosit100% (1)

- A Pediatrician's Guide To Central Precocious PubertyDocument12 pagesA Pediatrician's Guide To Central Precocious PubertyAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- FNCPDocument7 pagesFNCPGwen Denielle PadillaNo ratings yet

- Peds 2022057010Document24 pagesPeds 2022057010aulia lubisNo ratings yet

- IMCI Lecture For NCM 104semisDocument171 pagesIMCI Lecture For NCM 104semisKathleen Joy G. TadleNo ratings yet

- Estimated Survival and Major Comorbidities of Very Preterm Infants Discharged Against Medical Advice Vs Treated With Intensive Care in ChinaDocument10 pagesEstimated Survival and Major Comorbidities of Very Preterm Infants Discharged Against Medical Advice Vs Treated With Intensive Care in ChinacepifhNo ratings yet

- Healthy You AdhdDocument1 pageHealthy You AdhdIndiana Family to FamilyNo ratings yet

- Delirium 3 PDFDocument9 pagesDelirium 3 PDFrizkymutiaNo ratings yet

- Telemedicina y SeguimientoDocument9 pagesTelemedicina y SeguimientoRobert MoyaNo ratings yet

- Intjhealthalliedsci611-Preoperative Preparation of ChildrenDocument4 pagesIntjhealthalliedsci611-Preoperative Preparation of ChildrenviviNo ratings yet

- Textbook Mcqs in Pediatrics Review of Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics 20Th Edition Zuhair M Almusawi Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Mcqs in Pediatrics Review of Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics 20Th Edition Zuhair M Almusawi Ebook All Chapter PDFsandra.millican277100% (11)

- Sedation and Analgesia for the Pediatric Intensivist: A Clinical GuideFrom EverandSedation and Analgesia for the Pediatric Intensivist: A Clinical GuidePradip P. KamatNo ratings yet

- Síndrome de Dolor MiofascialDocument7 pagesSíndrome de Dolor MiofascialAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Neuropathies in PregnancyDocument15 pagesPeripheral Neuropathies in PregnancyAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Síndrome de Dolor MiofascialDocument7 pagesSíndrome de Dolor MiofascialAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Neuropathies in PregnancyDocument15 pagesPeripheral Neuropathies in PregnancyAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Adult FlatfootDocument7 pagesAdult FlatfootAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- The Conservative Treatment of Traumatic Thoracolumbar Vertebral FracturesDocument9 pagesThe Conservative Treatment of Traumatic Thoracolumbar Vertebral FracturesAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Unfolding The Outcomes of Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 10 Year Follow UpDocument12 pagesUnfolding The Outcomes of Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 10 Year Follow UpAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Noise Around The KneeDocument8 pagesNoise Around The KneeAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Work-Related Carpal Tunnel Syndrome TreatmentDocument6 pagesWork-Related Carpal Tunnel Syndrome TreatmentAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- History Toe ProsthesisDocument12 pagesHistory Toe ProsthesisAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Low Back PainDocument24 pagesLow Back PainAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Chaptar 30 Degenerative Spine DiseaseDocument9 pagesChaptar 30 Degenerative Spine DiseaseAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Shoulder DysfociaDocument92 pagesShoulder DysfociaKagomie SaskieNo ratings yet

- Hyperemesis GravidarumDocument4 pagesHyperemesis GravidarumAaliyaan KhanNo ratings yet

- Elementary Animal ReproductionDocument8 pagesElementary Animal ReproductionJibachha SahNo ratings yet

- Smith-Blair-Assessment-And-Management-Of-Neuropathic-Pain-In-Primary-Care 2Document51 pagesSmith-Blair-Assessment-And-Management-Of-Neuropathic-Pain-In-Primary-Care 2Inês Beatriz Clemente CasinhasNo ratings yet

- Gastric CáncerDocument206 pagesGastric CáncerjorgehogNo ratings yet

- PhysioEx Exercise 7 Activity 1 Damagel)Document3 pagesPhysioEx Exercise 7 Activity 1 Damagel)CLAUDIA ELISABET BECERRA GONZALESNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Grade 11Document28 pagesModule 1 Grade 11Mae BeginoNo ratings yet

- Cancer Hallmark 1 (From Jargonwall - Com)Document9 pagesCancer Hallmark 1 (From Jargonwall - Com)eihimekpen02No ratings yet

- Usg ThoraxDocument64 pagesUsg ThoraxArvind KanagaratnamNo ratings yet

- Id2019b2 SampleDocument21 pagesId2019b2 SampleSheikh FaishalNo ratings yet

- Anusha Article IJIRMFDocument5 pagesAnusha Article IJIRMFAnusha SampathNo ratings yet

- Infection of The Urinary Tract: Campbell-Walsh 11th ED, CH12Document109 pagesInfection of The Urinary Tract: Campbell-Walsh 11th ED, CH12Sirawit Namkaeng ChoksuchatNo ratings yet

- Amoebiasis - and GiardiasisDocument59 pagesAmoebiasis - and GiardiasisSaurabh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Minutes of The India-Bhutan Onsite Bilateral Meeting Guwahati, AssamDocument40 pagesMinutes of The India-Bhutan Onsite Bilateral Meeting Guwahati, AssamsidhuzNo ratings yet

- Developing A Clinically Important Class of Glycan-Targeted Biologics With Unprecedented Tumor Specificity Funding First Human DataDocument17 pagesDeveloping A Clinically Important Class of Glycan-Targeted Biologics With Unprecedented Tumor Specificity Funding First Human DataNuno Prego RamosNo ratings yet

- Menstrual CycleDocument24 pagesMenstrual CycleMonika Bagchi100% (4)

- Topic OutlineDocument4 pagesTopic OutlineQuitet GutibNo ratings yet

- Transport of OxygenDocument13 pagesTransport of OxygenSiti Nurkhaulah JamaluddinNo ratings yet

- Hematologymnemonics 151002194222 Lva1 App6891Document8 pagesHematologymnemonics 151002194222 Lva1 App6891padmaNo ratings yet

- Covid 2Document34 pagesCovid 2Inthe MOON youNo ratings yet

- Oxytetracycline PowderDocument1 pageOxytetracycline Powderbejoy karimNo ratings yet

- Blood Culture LabDocument3 pagesBlood Culture LabOrhan AsdfghjklNo ratings yet

- Cancer 2019 PDFDocument652 pagesCancer 2019 PDFWahyu Maulana100% (1)

- Periodontal Case Study by Mae VirayDocument27 pagesPeriodontal Case Study by Mae Virayapi-610791922No ratings yet

- IMMUNIZATION LecDocument77 pagesIMMUNIZATION LecKavya ReddyNo ratings yet

- Theoretical FrameworkDocument2 pagesTheoretical FrameworkBearish PaleroNo ratings yet

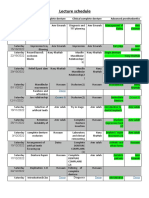

- Lecture Schedule: Advanced Prosthodontics Clinical Complete Denture Preclinical Complete Denture DateDocument3 pagesLecture Schedule: Advanced Prosthodontics Clinical Complete Denture Preclinical Complete Denture DateHaitham BakryNo ratings yet

- Original XIpaper 1999Document7 pagesOriginal XIpaper 1999Demilyadioppy AbevitNo ratings yet

Addressing Pediatric Intoeing in Primary Care

Addressing Pediatric Intoeing in Primary Care

Uploaded by

Abraham SaldañaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Addressing Pediatric Intoeing in Primary Care

Addressing Pediatric Intoeing in Primary Care

Uploaded by

Abraham SaldañaCopyright:

Available Formats

1.

0

CONTACT HOUR

Downloaded from https://journals.lww.com/tnpj by BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3ZI03TR16A97yKlvBf4BX9tVV8XO+M4gGx4uSvFdIQoU= on 05/16/2020

Jacqueline Southby / Thinkstock

Addressing pediatric intoeing

in primary care

Abstract: Primary care providers frequently encounter children with an intoed gait.

Intoeing is most often a normal variation of development that resolves without treatment.

The well-informed primary care NP can identify the small subset who need referral

through child and/or family history, physical exam, and identification of red flags.

By Lauren Davis, DNP, RN and Donna G. Nativio, PhD, CRNP, FAAN, FAANP

oncern about intoeing in children is a com- patients with intoeing and found that approximately

C mon presenting complaint in primary care.

Parents may expect this condition to re-

95% had a benign diagnosis that did not require any

treatment.1 This is consistent with other research

quire referral to and treatment with an orthopedic studies and supports that the majority of children

specialist and/or physical therapist. However, intoe- with intoeing can be managed in primary care.2

ing is one of the most common musculoskeletal However, there is a small subset of patients for

findings and is frequently due to normal variations whom intoeing is a sign of an underlying pathologic

in development. condition or who will require interventions led by an

An intoeing clinic conducted by advanced prac- orthopedic specialist. The patient’s history and physi-

tice providers (NPs, clinical nurse specialists, and cal exam will guide the NP to determine whether the

physician assistants) with an orthopedic surgeon as patient can be managed in primary care or requires a

consultant evaluated 926 otherwise healthy pediatric specialty care referral.

Keywords: femoral anteversion, intoeing, metatarsus adductus, pediatric physical exam, tibial torsion

www.tnpj.com The Nurse Practitioner • July 2018 31

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Addressing pediatric intoeing in primary care

The three most common causes of intoeing are also helpful to gain information regarding the onset

metatarsus adductus, internal tibial torsion, and in- and clinical course of intoeing. (See Expected clinical

creased femoral anteversion. These conditions can be course of intoeing.)

diagnosed by physical exam without the use of radio- It is important to remember that these conditions

graphical studies and can be managed by primary care can often occur in combination.2,8,9 Red flags obtained

providers.3 while acquiring the patient’s history may include uni-

lateral or asymmetric intoeing, with findings sugges-

■ Anatomy and pathophysiology tive of cerebral palsy or developmental dysplasia of the

The formation of lower extremity alignment begins at hip, delayed developmental milestones, associated pain

the seventh week of intrauterine life when the lower or limping, daily recurrent trips or falls, or a positive

limbs rotate medially and bring the great toe toward family history for disorders that can lead to intoeing

midline.4 This intrauterine positioning is hypothesized requiring treatment.7,10

to influence limb rotational deformities. Metatarsus

adductus is characterized by the medial deviation of ■ Physical exam

the metatarsals. This most often occurs bilaterally and A thorough developmental, musculoskeletal, and neu-

is thought to be a result of intrauterine positioning.3 rologic exam must be completed for the child present-

Internal tibial torsion is internal rotation of the tibia ing with intoeing. An age-appropriate assessment of

on its long axis.5 The exact etiology is unknown; how- developmental social and emotional, language and

ever, it is also thought to be a result of intrauterine po- communication, cognitive, and gross and fine motor

sitioning.6 A newborn normally has approximately 40 milestones should be documented.7 If the patient is

degrees of femoral anteversion at birth, which decreases ambulatory, he or she should be assessed while stand-

to 15 to 20 degrees by the age of 8 to 10 years.4 Some ing, walking, and running while observing for sym-

believe that increased femoral anteversion is a result of metry, limping, and foot or patellar progression an-

persistent infantile anteversion, whereas others believe gles.2,3,7 Specific physical exam techniques are used to

it is acquired secondary to abnormal sitting habits (W determine the origin of intoeing (see Physical exam

leg position) or the prone sleeping position.4 techniques to identify intoeing).2,3,11-14

When a patient’s presentation is consistent with one

■ History of these three diagnoses and there is a lack of red flags

The clinician should elicit a complete birth and medical or significant physical exam findings indicative of an-

history, including developmental milestones, presence other diagnosis, the NP can properly educate the family

of chronic illnesses, and any associated complaints.6,7 about the condition and manage the patient in primary

A family history of intoeing may suggest a genetic care. (See Physical exam findings of intoeing.)

variation and/or may be used to reassure parents that

these conditions frequently resolve with growth.7,8 It is ■ Differential diagnosis

Pathologic conditions associated with the presence of

Expected clinical course of intoeing7-9 red flags discussed in the history of intoeing include

neuromuscular diseases (cerebral palsy), developmen-

Condition Onset Course

tal dysplasia of the hip, lower leg deformities such as

club foot and skewfoot, infection, and bone tumor or

Metatarsus Apparent at Mild cases with good

adductus birth or early in range of motion show lesion.8,10 It is also key to differentiate intoeing from

infancy improvement by 12 genu varum (bowleg). Genu varum is most often physi-

months and resolve ologic and a normal variation seen in 1- to 3-year-olds.

by age 3 years

Similar to internal tibial torsion, it is often first noticed

Internal Between ages Improves by

tibial torsion 1 and 2 years age 6-8 years

once the child begins ambulation. On physical exam,

(when the child there is typically a waddling gait with symmetrical and

begins walking) diffuse lower extremity bowing and an increased dis-

Increased After the age Gradual improvement, tance between the knees when standing.

femoral of 2 years resolves around age There is no casting, bracing, or surgery indicated

anteversion 10-12 years

for physiologic bowing.3 If genu varum continues to

32 The Nurse Practitioner • Vol. 43, No. 7 www.tnpj.com

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Addressing pediatric intoeing in primary care

Physical exam techniques to identify intoeing2,3,7,8

Exam technique Explanation Findings Picture

Determined while viewing Foot and/or patellar angle

Foot/patellar

the foot and patella as the may be described as inter-

progression angle

patient walks forward nal, neutral, or external

Knee caps point a

straight ahead

With the patient sit-

Normally, lateral mal-

ting and patella facing Normal Internal

leolus is posterior to the tibial tibial

View of lateral and straight forward, view the torsion torsion

medial malleolus (0 to -10

medial malleolus relationship of the lateral

degrees internal rotation is

malleolus to the medial

average)

malleolus

With the patient prone,

Normally, the line crosses

view a line through the

Heel bisector line the forefoot between the

axis of the heel to the

second and third toes

forefoot

With the patient prone,

Normal mean in infants is

knee flexed, and foot

5 degrees internal angle

flexed, an angle is formed

Thigh-foot angle

by drawing a line that is

Normal mean by age 8 is

bisecting the thigh and a

10 degrees external

line bisecting the foot

.

External Internal c

With the patient prone: rotation rotation

Normal internal during

Internal (legs rotated 0˚

childhood is 40 to 50

away from center of the

degrees 40˚

body) 45˚

Hip internal/

external rotation

External (legs rotated to- Normal external is 40 to 70

ward center of the body) degrees

These angles are often measured subjectively, but a geniometer can be used to determine a more precise objective measurement.

a

Reproduced with permission from Merens TA. The toddler gait—normal or not. Pediatric Annals. 2015;44(5)187-190.

b

Reproduced with permission from Rosenfeld SB. Approach to the child with in-toeing. In: UpToDate, Post TW, eds. Waltham, MA: UpToDate. Copyright ©2018

UpToDate, Inc.

c

Reproduced with permission from Beetham WP, Polley HF, Slocumb CH, Weaver WF. Physical Examination of the Joints. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1965.

www.tnpj.com The Nurse Practitioner • July 2018 33

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Addressing pediatric intoeing in primary care

worsen or is seen beyond the age of 3 or 4 years, a risk factors present for a pathologic condition. Fur-

referral to an orthopedist for additional investigation thermore, surgical management is not necessary for

is warranted. Pathologic causes of genu varum include these conditions most of the time.1,7,8 Orthotics (braces

rickets, epiphyseal dysplasia, dwarfism, and other and splints) do not change the natural history or ad-

metabolic abnormalities or growth disturbances.3 vance resolution.7

For patients with metatarsus adductus, providers

■ Management can encourage families to massage and lightly stretch

Routine radiographs are not recommended for chil- the inside of the foot into a neutral position; however,

dren with intoeing and are typically only indicated if no research consistently supports the use of specific

there are complaints of pain to rule out hip dysplasia stretching or exercise to resolve intoeing quicker than

after an abnormal hip exam or if there are additional the child’s natural growth and development.8

Families were previously educated to discourage

their children with increased femoral anteversion from

Physical exam findings of intoeing2,3,7,8

sitting in the “W” position (sitting on the bottom with

Metatarsus adductus knees bent in the front center and legs splayed out

• Internal, neutral, or external foot and patella toward the back of each side); however, research has

progression angle shown this is unlikely to change the natural history as

• Mild deformity (heel bisector crosses third toe) well.6,7 The “W” position is comfortable for the child

• Moderate deformity (heel bisector crosses between

third and fourth toes) and this sitting position is not detrimental to normal

• Severe deformity (heel bisector crosses between development. The child will stop sitting in this posi-

fourth and fifth toes) tion once they can sit cross-legged more comfortably

Internal tibial torsion as natural improvement occurs.6

• Internal, neutral, or external foot and patella One of the most important aspects to the man-

progression angle agement of intoeing is family reassurance. If the

• Thigh-foot angle >10 degrees internal

• With patella forward, lateral malleolus is parallel child’s parents or guardians choose not to seek fur-

or anterior to medial malleolus ther workup treatment after obtaining the patient’s

Increased femoral anteversion history and performing a physical exam, families

• Internal foot and patella progression angle should be educated on the prevalence of these condi-

• Increased hip internal rotation (may be up to 90 tions and their expected resolutions.

degrees [legs rotate flat against exam table]) For long-term prognosis, these rotational deformi-

• Preference to sit in “W” position

ties do not lead to an increased risk of hip or knee

arthritis.7,15 Children with metatarsus adductus, inter-

Indications for orthopedic referral7,8

nal tibial torsion, and increased femoral anteversion

do not require activity restrictions or additional pre-

Metatarsus adductus cautions. These conditions are common developmen-

• Cannot passively bring foot into neutral position tal variations that often resolve without treatment as

(may indicate club foot) the child grows.7

• Severe deformity (heel bisector crosses between

fourth and fifth toes)

■ When to refer

Tibial torsion

Any of the red flags discussed in the history section

• Child older than 8 years with severe intoeing causing

indicate a need for referral to an orthopedic specialist.

functional or cosmetic deformity

Physical exam findings of limb length discrepancy and

Increased femoral anteversion

deformity progression should be referred as well.6 (See

• Child is >8 years old and complains of severe function-

al or cosmetic deformity with:

Indications for orthopedic referral.)

femoral anteversion >50 degrees (measured

radiographically) ■ Implications for practice

internal hip rotation >80 degrees

Intoeing can be distressing to pediatric patients and

Any diagnosis of intoeing that does not follow an ex- families, especially as patients get older and begin

pected clinical course

school and activities. NPs can reassure patients and

34 The Nurse Practitioner • Vol. 43, No. 7 www.tnpj.com

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

Addressing pediatric intoeing in primary care

families that these benign conditions resolve with 8. Spiegel DA, Horn BD. Lippincott’s Primary Care Orthopaedics. 2nd ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013.

growth and development and the child can participate

9. Harris E. The intoeing child: etiology, prognosis, and current treatment

in activities the same as other children. Awareness of options. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2013;30(4):531-565.

the red flags and indications for referral can help NPs 10. Evans AM. Mitigating clinician and community concerns about children’s

flatfeet, intoeing gait, knock knees or bow legs. J Paediatr Child Health.

identify patients who require additional specialty care 2017;53(11):1050-1053.

and allow them to manage the majority of intoeing 11. Carr JB 2nd, Yang S, Lather LA. Pediatric pes planus: a state-of-the-art

review. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20151230.

patients who will not need referral.

12. Merens TA. The toddler gait—normal or not. Pediatr Ann. 2015;44(5):

187-190.

REFERENCES 13. Rosenfeld SB. Approach to the child with in-toeing. 2017. www.Uptodate.

com.

1. Faulks S, Brown K, Birch JG. Spectrum of diagnosis and disposition of pa-

tients referred to a pediatric orthopaedic center for a diagnosis of intoeing. J 14. William P, Polley HF, Slocumb CH, Beetham WFW. Physical Examination

Pediatr Orthop. 2017;37(7):e432-e435. of the Joints. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1965.15. Weinberg DS, Park PJ,

Morris WZ, Liu RW. Femoral version and tibial torsion are not associated

2. Sielatycki JA, Hennrikus WL, Swenson RD, Fanelli MG, Reighard CJ, with hip or knee arthritis in a large osteological collection. J Pediatr Orthop.

Hamp JA. In-toeing is often a primary care orthopedic condition. J Pediatr. 2017;37(2):e120-e128.

2016;177:297-301.

3. Zitelli BJ, McIntire S, Nowalk AJ. Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis. 7th ed.

Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017. Lauren Davis is a recent DNP graduate from the University of Pittsburgh

School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, Pa.

4. Kliegman RM, Stanton B, Geme J, Schor NF. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.

20th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2015.

5. Iannotti JP, Parker RD. Netter Collection of Medical Illustrations: Musculoskel- Donna G. Nativio is an associate professor and DNP Program Director at the

etal System, Volume 6, Part II—Spine and Lower Limb. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, Pa.

PA: Saunders; 2013.

6. Mooney JF 3rd. Lower extremity rotational and angular issues in children. The authors and planners have disclosed no potential conflicts of interest,

Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014;61(6):1175-1183. financial or otherwise.

7. Rerucha CM, Dickison C, Baird DC. Lower extremity abnormalities in

children. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(4):226-233. DOI-10.1097/01.NPR.0000534939.42714.d0

For more than 278 additional continuing education articles related to

Advanced Practice Nursing topics, go to NursingCenter.com/CE.

Earn CE credit online:

Go to www.nursingcenter.com/CE/NP and receive a

certificate within minutes.

INSTRUCTIONS

Addressing pediatric intoeing in primary care

TEST INSTRUCTIONS DISCOUNTS and CUSTOMER SERVICE

• To take the test online, go to our secure website at www. • Send two or more tests in any nursing journal published by

nursingcenter.com/ce/NP. View instructions for taking the Lippincott Williams & Wilkins together and deduct $0.95 from the

test online there. price of each test.

• If you prefer to submit your test by mail, record your an- • We also offer CE accounts for hospitals and other healthcare facilities

swers in the test answer section of the CE enrollment form on nursingcenter.com. Call 1-800-787-8985 for details.

on page 36. You may make copies of the form.

Each question has only one correct answer. There is no PROVIDER ACCREDITATION

minimum passing score required. Lippincott Professional Development will award 1.0 contact hour for this

Complete the registration information and course evalua- continuing nursing education activity.

tion. Mail the completed form and registration fee of $12.95 Lippincott Professional Development is accredited as a provider of

to: Lippincott Professional Development CE Group, 74 Brick continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing

Blvd., Bldg. 4, Suite 206, Brick, NJ 08723. We will mail your Center’s Commission on Accreditation.

certificate in 4 to 6 weeks. For faster service, include a fax This activity is also provider approved by the California Board

number and we will fax your certificate within 2 business of Registered Nursing, Provider Number CEP 11749 for 1.0 contact

days of receiving your enrollment form. You will receive hour. Lippincott Professional Development is also an approved

your CE certificate of earned contact hours and an answer provider of continuing nursing education by the District of Columbia,

key to review your results. Georgia, and Florida CE Broker #50-1223.

• Registration deadline is June 5, 2020.

www.tnpj.com The Nurse Practitioner • July 2018 35

Copyright © 2018 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Nse 417 Midterm Evaluation Rosette LenonDocument7 pagesNse 417 Midterm Evaluation Rosette Lenonapi-341527743No ratings yet

- Heart & Neck Vessel AssessmentDocument46 pagesHeart & Neck Vessel AssessmentLouise Nathalia VelasquezNo ratings yet

- Placenta ChecklistDocument2 pagesPlacenta ChecklistNidhi Shivam Ahlawat100% (7)

- Pediatric Radiography - Merrills Atlas of Radiographic Positioning and ProceduresDocument61 pagesPediatric Radiography - Merrills Atlas of Radiographic Positioning and ProceduresJonald Pulgo IcoyNo ratings yet

- Influence of Maternal Educational Instruction On.9Document5 pagesInfluence of Maternal Educational Instruction On.9Tô ThuỷNo ratings yet

- Future of Early Intervention With Infants and Toddlers For Whom Typical Experiences Are Not EffectiveDocument6 pagesFuture of Early Intervention With Infants and Toddlers For Whom Typical Experiences Are Not EffectiveSaniNo ratings yet

- Advocating For The Child: The Role of Pediatric Psychology For Children With Cleft Lip And/or PalateDocument7 pagesAdvocating For The Child: The Role of Pediatric Psychology For Children With Cleft Lip And/or PalateeducacionchileNo ratings yet

- Dentists' Behavior Management As It Affects Com Pliance and Fear in Pediatric PatientsDocument7 pagesDentists' Behavior Management As It Affects Com Pliance and Fear in Pediatric PatientsyioulaNo ratings yet

- Imci Components of IMCI StrategyDocument12 pagesImci Components of IMCI StrategyPebbles PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Artikel LeukemiaDocument4 pagesArtikel LeukemiaHandian FINo ratings yet

- Self Assessment - Midterm 2016Document11 pagesSelf Assessment - Midterm 2016api-341527743No ratings yet

- Important Considerations in The Initial Clinical Evaluation of The Dysmorphic NeonateDocument5 pagesImportant Considerations in The Initial Clinical Evaluation of The Dysmorphic NeonateKaroo_123No ratings yet

- CHN Course PlanDocument29 pagesCHN Course PlanSathya PalanisamyNo ratings yet

- What Causes ADHD Understanding What Goes Wrong.16Document2 pagesWhat Causes ADHD Understanding What Goes Wrong.16FiegoParadaOrtizNo ratings yet

- First Experiences With Early Intervention: A National PerspectiveDocument12 pagesFirst Experiences With Early Intervention: A National PerspectiveSaniNo ratings yet

- Pediatric RadiographyDocument10 pagesPediatric RadiographyRachelle Danya Dela RosaNo ratings yet

- Home-Based DIR/Floortime Intervention Program For Preschool Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: Preliminary FindingsDocument12 pagesHome-Based DIR/Floortime Intervention Program For Preschool Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders: Preliminary FindingsJoao ColomaNo ratings yet

- Bab I PDFDocument6 pagesBab I PDFAwliyana Risla PutriNo ratings yet

- Children For SurgeryDocument7 pagesChildren For SurgeryHany ElbarougyNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based Toilet TrainingDocument4 pagesEvidence Based Toilet TrainingAhmad HaqulNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Parent Engagement in DIR/Floortime For Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument9 pagesFactors Associated With Parent Engagement in DIR/Floortime For Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderSantiagoDavidSuárezNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument34 pagesResearchIza MascariñasNo ratings yet

- NCP Deficient Knowledge of ROPDocument2 pagesNCP Deficient Knowledge of ROPMark Zedrix MediarioNo ratings yet

- Integrated Management of Childhood IllnessesDocument5 pagesIntegrated Management of Childhood IllnessesPamela Joy Rico UnayNo ratings yet

- Pedia 19Document6 pagesPedia 19Christopher ObedenciaNo ratings yet

- Community FNCPDocument7 pagesCommunity FNCPCarl Jefferson Pagulayan100% (1)

- BehGuid 1 Acceptance of Behavior Guidance Techniques Used in Pediatric Dentistry by Parents From Diverse BackgroundsDocument8 pagesBehGuid 1 Acceptance of Behavior Guidance Techniques Used in Pediatric Dentistry by Parents From Diverse BackgroundsAbdulmajeed alluqmaniNo ratings yet

- Anc 0000000000000030Document9 pagesAnc 0000000000000030maya amaliaNo ratings yet

- H. Nursing Care Plan: Altered Parenting RoleDocument2 pagesH. Nursing Care Plan: Altered Parenting RoleClovie ArsenalNo ratings yet

- Cordewener 2017Document7 pagesCordewener 2017patricia brucellariaNo ratings yet

- PQCNC New Initiative Proposal NASDocument9 pagesPQCNC New Initiative Proposal NASkcochranNo ratings yet

- CPG For Assessment of Children and AdolescentsDocument18 pagesCPG For Assessment of Children and AdolescentsSarwar BaigNo ratings yet

- MCHN Group2 NCP 2aDocument20 pagesMCHN Group2 NCP 2ajaytoo202020No ratings yet

- Coek - Info Dentofacial Orthopedics With Functional AppliancesDocument2 pagesCoek - Info Dentofacial Orthopedics With Functional ApplianceshabeebNo ratings yet

- Gpsych 2018 000009Document9 pagesGpsych 2018 000009Ana paula CamargoNo ratings yet

- 20-Appendices PeriodicitySchedule Bright FuturesDocument1 page20-Appendices PeriodicitySchedule Bright FuturesdrjohnckimNo ratings yet

- Archdischild 2019 316928Document5 pagesArchdischild 2019 316928Krit KritNo ratings yet

- Bonding 3Document2 pagesBonding 3mama adjoa atoquaye-quayeNo ratings yet

- Case Studies in Pediatric Anesthesia-4.preoperative - AnxietyDocument5 pagesCase Studies in Pediatric Anesthesia-4.preoperative - AnxietyismailcemNo ratings yet

- Poster RF - Adam Draft May 26Document1 pagePoster RF - Adam Draft May 26Adam SandowNo ratings yet

- Ongoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedDocument18 pagesOngoing Pediatric Health Care For The Child Who Has Been MaltreatedJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Diarrhoea and Its Management Among Mothers of Under Five Children at UHTC Vijayapura: A Cross Sectional StudyDocument4 pagesKnowledge, Attitude and Practices Regarding Diarrhoea and Its Management Among Mothers of Under Five Children at UHTC Vijayapura: A Cross Sectional StudyAnisa SafutriNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Self-MutilationoutDocument6 pagesAdolescent Self-Mutilationoutclaudia mihaiNo ratings yet

- A Four Part Approach To Assessing Feeding.13Document2 pagesA Four Part Approach To Assessing Feeding.13Adhitya TaslimNo ratings yet

- Peds 2022057010Document23 pagesPeds 2022057010hb75289kyvNo ratings yet

- Working With Children in Humanitarian WASH ProgrammesDocument13 pagesWorking With Children in Humanitarian WASH ProgrammesOxfamNo ratings yet

- Early Detection of Developmental and Behavioral Problems: Pediatrics in Review September 2000Document10 pagesEarly Detection of Developmental and Behavioral Problems: Pediatrics in Review September 2000annaNo ratings yet

- Sample ChapterDocument11 pagesSample ChapterTales SoNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Nursing Procedure ManualDocument12 pagesPediatric Nursing Procedure ManualGopal Pandey100% (1)

- Tricking Kids Into The Perfect ExamDocument2 pagesTricking Kids Into The Perfect ExamLesterNo ratings yet

- NCLEX Practice Exam For Pediatric Nursing 2 - RNpediaDocument14 pagesNCLEX Practice Exam For Pediatric Nursing 2 - RNpediaLot Rosit100% (1)

- A Pediatrician's Guide To Central Precocious PubertyDocument12 pagesA Pediatrician's Guide To Central Precocious PubertyAbdurrahman HasanuddinNo ratings yet

- FNCPDocument7 pagesFNCPGwen Denielle PadillaNo ratings yet

- Peds 2022057010Document24 pagesPeds 2022057010aulia lubisNo ratings yet

- IMCI Lecture For NCM 104semisDocument171 pagesIMCI Lecture For NCM 104semisKathleen Joy G. TadleNo ratings yet

- Estimated Survival and Major Comorbidities of Very Preterm Infants Discharged Against Medical Advice Vs Treated With Intensive Care in ChinaDocument10 pagesEstimated Survival and Major Comorbidities of Very Preterm Infants Discharged Against Medical Advice Vs Treated With Intensive Care in ChinacepifhNo ratings yet

- Healthy You AdhdDocument1 pageHealthy You AdhdIndiana Family to FamilyNo ratings yet

- Delirium 3 PDFDocument9 pagesDelirium 3 PDFrizkymutiaNo ratings yet

- Telemedicina y SeguimientoDocument9 pagesTelemedicina y SeguimientoRobert MoyaNo ratings yet

- Intjhealthalliedsci611-Preoperative Preparation of ChildrenDocument4 pagesIntjhealthalliedsci611-Preoperative Preparation of ChildrenviviNo ratings yet

- Textbook Mcqs in Pediatrics Review of Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics 20Th Edition Zuhair M Almusawi Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Mcqs in Pediatrics Review of Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics 20Th Edition Zuhair M Almusawi Ebook All Chapter PDFsandra.millican277100% (11)

- Sedation and Analgesia for the Pediatric Intensivist: A Clinical GuideFrom EverandSedation and Analgesia for the Pediatric Intensivist: A Clinical GuidePradip P. KamatNo ratings yet

- Síndrome de Dolor MiofascialDocument7 pagesSíndrome de Dolor MiofascialAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Neuropathies in PregnancyDocument15 pagesPeripheral Neuropathies in PregnancyAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Síndrome de Dolor MiofascialDocument7 pagesSíndrome de Dolor MiofascialAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Neuropathies in PregnancyDocument15 pagesPeripheral Neuropathies in PregnancyAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Adult FlatfootDocument7 pagesAdult FlatfootAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- The Conservative Treatment of Traumatic Thoracolumbar Vertebral FracturesDocument9 pagesThe Conservative Treatment of Traumatic Thoracolumbar Vertebral FracturesAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Unfolding The Outcomes of Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 10 Year Follow UpDocument12 pagesUnfolding The Outcomes of Surgical Treatment of Lumbar Spinal Stenosis, 10 Year Follow UpAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Noise Around The KneeDocument8 pagesNoise Around The KneeAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Work-Related Carpal Tunnel Syndrome TreatmentDocument6 pagesWork-Related Carpal Tunnel Syndrome TreatmentAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- History Toe ProsthesisDocument12 pagesHistory Toe ProsthesisAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Low Back PainDocument24 pagesLow Back PainAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Chaptar 30 Degenerative Spine DiseaseDocument9 pagesChaptar 30 Degenerative Spine DiseaseAbraham SaldañaNo ratings yet

- Shoulder DysfociaDocument92 pagesShoulder DysfociaKagomie SaskieNo ratings yet

- Hyperemesis GravidarumDocument4 pagesHyperemesis GravidarumAaliyaan KhanNo ratings yet

- Elementary Animal ReproductionDocument8 pagesElementary Animal ReproductionJibachha SahNo ratings yet

- Smith-Blair-Assessment-And-Management-Of-Neuropathic-Pain-In-Primary-Care 2Document51 pagesSmith-Blair-Assessment-And-Management-Of-Neuropathic-Pain-In-Primary-Care 2Inês Beatriz Clemente CasinhasNo ratings yet

- Gastric CáncerDocument206 pagesGastric CáncerjorgehogNo ratings yet

- PhysioEx Exercise 7 Activity 1 Damagel)Document3 pagesPhysioEx Exercise 7 Activity 1 Damagel)CLAUDIA ELISABET BECERRA GONZALESNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Grade 11Document28 pagesModule 1 Grade 11Mae BeginoNo ratings yet

- Cancer Hallmark 1 (From Jargonwall - Com)Document9 pagesCancer Hallmark 1 (From Jargonwall - Com)eihimekpen02No ratings yet

- Usg ThoraxDocument64 pagesUsg ThoraxArvind KanagaratnamNo ratings yet

- Id2019b2 SampleDocument21 pagesId2019b2 SampleSheikh FaishalNo ratings yet

- Anusha Article IJIRMFDocument5 pagesAnusha Article IJIRMFAnusha SampathNo ratings yet

- Infection of The Urinary Tract: Campbell-Walsh 11th ED, CH12Document109 pagesInfection of The Urinary Tract: Campbell-Walsh 11th ED, CH12Sirawit Namkaeng ChoksuchatNo ratings yet

- Amoebiasis - and GiardiasisDocument59 pagesAmoebiasis - and GiardiasisSaurabh AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Minutes of The India-Bhutan Onsite Bilateral Meeting Guwahati, AssamDocument40 pagesMinutes of The India-Bhutan Onsite Bilateral Meeting Guwahati, AssamsidhuzNo ratings yet

- Developing A Clinically Important Class of Glycan-Targeted Biologics With Unprecedented Tumor Specificity Funding First Human DataDocument17 pagesDeveloping A Clinically Important Class of Glycan-Targeted Biologics With Unprecedented Tumor Specificity Funding First Human DataNuno Prego RamosNo ratings yet

- Menstrual CycleDocument24 pagesMenstrual CycleMonika Bagchi100% (4)

- Topic OutlineDocument4 pagesTopic OutlineQuitet GutibNo ratings yet

- Transport of OxygenDocument13 pagesTransport of OxygenSiti Nurkhaulah JamaluddinNo ratings yet

- Hematologymnemonics 151002194222 Lva1 App6891Document8 pagesHematologymnemonics 151002194222 Lva1 App6891padmaNo ratings yet

- Covid 2Document34 pagesCovid 2Inthe MOON youNo ratings yet

- Oxytetracycline PowderDocument1 pageOxytetracycline Powderbejoy karimNo ratings yet

- Blood Culture LabDocument3 pagesBlood Culture LabOrhan AsdfghjklNo ratings yet

- Cancer 2019 PDFDocument652 pagesCancer 2019 PDFWahyu Maulana100% (1)

- Periodontal Case Study by Mae VirayDocument27 pagesPeriodontal Case Study by Mae Virayapi-610791922No ratings yet

- IMMUNIZATION LecDocument77 pagesIMMUNIZATION LecKavya ReddyNo ratings yet

- Theoretical FrameworkDocument2 pagesTheoretical FrameworkBearish PaleroNo ratings yet

- Lecture Schedule: Advanced Prosthodontics Clinical Complete Denture Preclinical Complete Denture DateDocument3 pagesLecture Schedule: Advanced Prosthodontics Clinical Complete Denture Preclinical Complete Denture DateHaitham BakryNo ratings yet

- Original XIpaper 1999Document7 pagesOriginal XIpaper 1999Demilyadioppy AbevitNo ratings yet