Professional Documents

Culture Documents

9 PDF

9 PDF

Uploaded by

GDKR ReddyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

9 PDF

9 PDF

Uploaded by

GDKR ReddyCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/258504978

Development of a Brief Instrument for Assessing Healthcare Employee

Satisfaction in a Low-Income Setting

Article in PLoS ONE · November 2013

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079053 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

9 40,754

7 authors, including:

Maureen E Canavan Zahirah McNatt

Yale University Columbia University

52 PUBLICATIONS 688 CITATIONS 11 PUBLICATIONS 113 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Dawit Tatek

Yale University

6 PUBLICATIONS 51 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Patterns and determinants of pain and emotional distress in older adults with cancer View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Dawit Tatek on 13 October 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Development of a Brief Instrument for Assessing

Healthcare Employee Satisfaction in a Low-Income

Setting

Rachelle Alpern1., Maureen E. Canavan2., Jennifer T. Thompson3, Zahirah McNatt2, Dawit Tatek2,

Tessa Lindfield4, Elizabeth H. Bradley2*

1 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States of America, 2 Yale School of Public Health, New Haven, Connecticut, United States of

America, 3 Department of Population Medicine, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, Boston, Massachusetts, United States of America, 4 Suffolk Primary Care Trust,

Suffolk, England

Abstract

Background: Ethiopia is one of 57 countries identified by the World Health Report 2006 as having a severely limited number

of health care professionals. In recognition of this shortage, the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health, through the Ethiopian

Hospital Management Initiative, prioritized the need to improve retention of health care workers. Accordingly, we sought to

develop the Satisfaction of Employees in Health Care (SEHC) survey for use in hospitals and health centers throughout

Ethiopia.

Methods: Literature reviews and cognitive interviews were used to generate a staff satisfaction survey for use in the

Ethiopian healthcare setting. We pretested the survey in each of the six hospitals and four health centers across Ethiopia

(98% response rate). We assessed content validity and convergent validity using factor analysis and examined reliability

using the Cronbach alpha coefficients to assess internal consistency. The final survey was comprised of 18 questions about

specific aspects of an individual’s work and two overall staff satisfaction questions.

Results: We found support for content validity, as data from the 18 responses factored into three factors, which we

characterized as 1) relationship with management and supervisors, 2) job content, and 3) relationships with coworkers.

Summary scores for two factors (relationship with management and supervisors and job content) were significantly

associated (P-value, ,0.001) with the two overall satisfaction items. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients showed good to excellent

internal consistency (Cronbach alpha coefficients .0.70) for the items in the three summary scores.

Conclusions: The introduction of consistent and reliable measures of staff satisfaction is crucial to understand and improve

employee retention rates, which threaten the successful achievement of the Millennium Development Goals in low-income

countries. The use of the SEHC survey in Ethiopian healthcare facilities has ample leadership support, which is essential for

addressing problems that reduce staff satisfaction and exacerbate excessive workforce shortages.

Citation: Alpern R, Canavan ME, Thompson JT, McNatt Z, Tatek D, et al. (2013) Development of a Brief Instrument for Assessing Healthcare Employee Satisfaction

in a Low-Income Setting. PLoS ONE 8(11): e79053. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079053

Editor: Yu-Kang Tu, National Taiwan University, Taiwan

Received April 15, 2013; Accepted September 18, 2013; Published November 5, 2013

Copyright: ß 2013 Alpern et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This study was supported, by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control; Clinton Health Access Initiative (1U2GPS0028242). The funders had no role

in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: Elizabeth.Bradley@yale.edu

. These authors contributed equally to this work.

Introduction resources have been linked with barriers to achieving the

Millennium Development Goals including low morale and

The severely limited number of health professionals in sub- motivation of health care workers, poor policies and practices

Saharan Africa negatively affects all types of health outcomes and for human resource development, and lack of supportive

threatens to limit the attainability of the Millennium Development supervision for health workers [3]. Although recruitment is critical

Goals. The World Health Report 2006 is dedicated to recognizing for addressing the shortage, retaining existing workers and

and addressing these workforce shortages. The report identified a instituting a scale up of successful programs is equally central to

total of 57 countries that had a critical shortage of healthcare address the workforce crisis.

employees with a global deficit of 2.4 million doctors, nurses, and The Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health has recently

midwives [1]. Ethiopia has one of the greatest shortages with a emphasized the need to produce and retain more health workers,

density of only 0.03 physicians, 0.23 clinical nurses, and 0.02 and increased efforts to improve human resource management in

midwives per 1,000 people in 2010 [2]. Several areas of human hospitals through the Ethiopian Hospital Management Initiative

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org 1 November 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 11 | e79053

Instrument for Assessing Employee Satisfaction

(EHMI) [4,5]. Experts in human resource management recognize should be included or excluded from our final survey using 11

the significant relationship between poor staff satisfaction and remaining articles from our literature review that were relevant,

lower employee retention rates, particularly in low-income but did not include validated surveys [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,

countries [6]. Despite the importance of staff satisfaction for 18,19,20,21].

employee retention, measures of staff satisfaction in health care

organizations in low-income countries are limited. We identified Survey Translation

five instruments [6,7,8,9,10] that have been validated as effective Individuals from the Medical Services Directorate (MSD) and

measures of satisfaction or motivation levels of employees in the the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) who were fluent in

healthcare settings; however, none had been designed for both English and Amharic translated the survey tool from English

healthcare employees including both nurses and non-nurses in into Amharic, Oromifa, and Tigrinya. During this translation

low-income countries. Furthermore, no instrument existed for use process, a committee was formed consisting of CHAI Ethiopian

specifically in Ethiopia. Hospital Management Initiative (EHMI) team members who have

Accordingly, we sought to develop and validate a staff technical background in Hospital Management, a strong under-

satisfaction measurement instrument for use with health care standing of the goals of the survey, and strong bilingual skills across

workers in government hospital and health centers throughout the four languages. A CHAI staff member made an initial

Ethiopia. To accomplish this objective, we used stakeholder translation for each question into each language, and then a

interviews and existing literature to develop sets of items and tested different CHAI staff member made a back translation indepen-

the instrument in ten healthcare facilities (six hospitals and four dently. At this point, the EHMI project team reviewed each back-

health centers), assessing both construct validity and internal translation. Last, project team members and translators met and

consistency. The resulting instrument may be helpful in Ethiopia’s discussed any discrepancies between the original questions and

ongoing efforts to expand the health workforce and strengthen its back-translations to agree upon the most appropriate final

health system. translation. Translation from English to Amharic was considered

a priority, because Amharic is the official language of Ethiopia,

Methods used nationwide, and the official working language of the Federal

Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. The EHMI project team

Ethics Statement member maintained a complete database on translation proce-

All research procedures were approved by the Institution dures, literature review findings, and survey refinement which was

Review Board of the Yale School of Medicine, the Ethiopian shared with both CHAI and MSD. Although this database was not

Ministry of Health, and the Centers for Disease Control. We released to the public, documented information on study

obtained Human Investigation Committee (HIC) exemption procedures can be obtained by contacting the authors.

(protocol number 1010007494) for our study which waived the

need for participant consent because no identifying participant Cognitive Interviews

information was obtained. Additionally, all participants were After compiling and translating potential items, we performed

provided with an information sheet to let them know what data cognitive interviews [22] to enhance the survey comprehensibility

would be collected, how it would be used and disseminated, and and applicability to all employees in hospitals and health centers.

any risks that would be encountered by participation. The We conducted five cognitive interviews in two hospitals in Addis

information sheet was translated and distributed to ensure that Ababa, Ethiopia. In order to ensure our questions were relevant to

participants fully understood that involvement in the study was different types of workers we selected interviewees from a range of

voluntary, they could refuse to participate at any time, and there jobs within the hospital: Acting Medical Director, Health

were no penalties if they declined participation. In order to Management Information Systems (HMIS) Officer, Quality

maintain participant anonymity, we provided envelopes and Management Team Officer, Physician, and Cleaner. During these

sealed collection boxes for employees to return completed surveys; interviews, we probed respondents about the comprehensibility

their names and specific job titles were not recorded and the name and meaning of each item, with particular focus on the translation

of the health facility they worked at was kept strictly confidential. from English to Amharic. In addition, as recommended by experts

in cognitive interviewing [22,23], we asked each respondent to

Survey Design comment on the content of the survey, including whether

To develop the Satisfaction of Employees in Health Care important topics might be missing or whether any questions were

(SEHC) survey, we first conducted a literature review to identify irrelevant. We used the results of the cognitive interviews to revise

validated surveys used to measure staff satisfaction in healthcare the survey tool, including translation modifications, refining the

settings. We found several pre-validated instruments used in items, dropping questions that were ambiguous and modifying

various areas, and identified questions within these instruments others to be more understandable.

that could be used to assess satisfaction of staff at all levels in low- Before piloting, we distributed the survey among relevant

income countries. We located five validated surveys from which stakeholders: the Ministry of Health, Black Lion Hospital (the

we extracted relevant questions: the Job Satisfaction Survey [7], largest hospital in the country), MSD and CHAI. Based on their

the Emergency Physician Job Satisfaction Instrument [8], the suggestions, we made some adjustments, including eliminating,

Measure of Job Satisfaction survey (designed for use in monitoring adding, and modifying questions and their order. The final survey

the morale of community nurses in four trusts) [9], Motivational was translated into three different languages (Amharic, Oromifa,

Outcome Constructs and Questions (designed for use in district and Tigrinya) and approved by MSD. Questions focused on

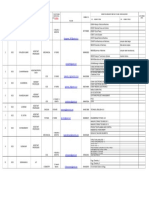

hospitals in Kenya) [10], and a job satisfaction scale developed to relationships with management and supervisors, job content, and

study the correlation between job satisfaction and turnover intent relationships with coworkers (Figure 1).

of primary healthcare nurses in rural South Africa [6]. All

extracted questions had to be appropriately modified for the use of Pilot Testing

measuring job satisfaction of all levels of employees in the We piloted the survey tool in six hospitals and four health

Ethiopian healthcare setting. We identified additional factors that centers across four regions (Amhara, Oromia, SNNPR and

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org 2 November 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 11 | e79053

Instrument for Assessing Employee Satisfaction

Figure 1. Satisfaction of Employees in Health Care (SEHC) Survey (English).

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079053.g001

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org 3 November 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 11 | e79053

Instrument for Assessing Employee Satisfaction

Tigray) and one city administration (Addis Ababa) throughout responses of items that loaded on that factor and dividing by the

Ethiopia, selected by Regional Coordinators from CHAI and number of responses, and then assessed the correlation between

MSD. The sample size of 70 surveys per facility was calculated the three summary scores and each of the overall staff satisfaction

conservatively, assuming at least 80% statistical power to detect a items.

difference of 1.0 on the staff satisfaction 0–10 scale with a standard For all analyses, we used multiple imputation [26] to calculate

deviation of 1.8 and 95% confidence. Hence, we approached all estimates for the missing item responses, which comprised 10% or

staff at hospitals with less than 70 employees, at least 70 staff at less for 93% of respondents. A total of 35 surveys (7% of

hospitals with between 70 and 140 employees, and at least 50% of respondents) had between 10% and 50% missing item responses.

staff at hospitals with more than 140 employees. In facilities with Multiple imputation procedure was performed using a series of

greater than 70 workers, participants were randomly selected from imputed data sets created by running an imputation model that

the list of all employed clinical and technical staff, including those incorporated all 20 survey items. The analysis was replicated for

in management positions. In facilities with 70 or fewer workers a each of the 10 imputed dataset and then the resulting estimates

census of all clinical, technical and management employees was were compiled. We conducted the analysis with the full sample

used. A total of 492 of the 500 staff approached (response rate (n = 492) using imputation, as well as with the smaller sample of

98%) completed face-to-face interviews with trained data collec- respondents (n = 457) with 10% or less missing item responses.

tors at both hospitals and health centers. At hospitals, project team Results were largely similar, thus we presented the findings from

members were assisted by the hospital staff member who was the full sample. We confirmed that imputed estimates matched

responsible for future SEHC survey distribution. Interpreters were valid answer values and were within the acceptable ranges for the

not needed, as team members were fluent in the local languages. 20 questions included in the final survey. All data analyses were

We added two additional questions to the survey for the pilot: a performed using SAS V 9.2.

free response question asking whether there are any topics related

to staff satisfaction that we did not ask about, and a fifth response

Results

column for asked if the response understood the question being

asked to them. Survey data were double-entered into Microsoft Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

Word templates by two different individuals to ensure data Of the 492 completed responses, 303 (61.6%) were from

accuracy and then imported into Excel. Discrepancies between the hospital employees, and 189 (38.4%) were from health center

two data entries were resolved by referring to the original paper employees fulfilling a range of positions; the survey was distributed

survey. The excel file and a Microsoft Access database were in a four different languages, Amharic, Oromifa, Tigrinya and

distributed to all hospitals and health centers. We also provided English, in diverse regions of the country, and responders

detailed training on survey management and database usage, represented an assortment of positions in the facility (Table 1).

including principles of data entry, so that hospital staff could make

the best use of these programs. Additional information can be

obtained by contacting the authors.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics for staff

Data collection took approximately four weeks, with one day

participants (N = 492).

spent collecting data at each site. Approximately 10 minutes was

spent per participant explaining the study and obtaining their

written consent for participation. Participants were asked to Variable N (%)

complete the survey independently; interviewers were available to

read questions aloud if requested, though he/she was not allowed Facility Type

to answer any questions about the content. The survey was Hospital 303 (61.6%)

designed to require an average of 30 minutes to complete. Health center 189 (38.4%)

Interviewers were trained in one day. Language

Amharic 393 (79.9%)

Data Analysis

English 7 (1.4%)

We evaluated construct validity, internal consistency, and

convergent validity to assess the instrument. To assess construct Oromifa 49 (10.0%)

validity, we conducted an varimax orthogonal rotated factor Tigrinya 43 (8.7%)

analysis with three factors specified a priori based on our hypotheses Geographical Region

about distinct concepts (i.e., relationship with management & Addis 189 (38.4%)

supervisors, job content, relationships with coworkers) and

Amhara 99 (20.1%)

confirmed the number of factors using a Scree test [24]. Survey

Oromia 101 (20.5%)

items that did not load strongly on any factor (i.e., loadings ,0.30)

or exhibited inadequate variability were dropped from further Southern Nations, Nationalities and People’s Region (SSNPR) 50 (10.2%)

analysis. For each factor, we calculated the Cronbach’s alpha Tigray 53 (10.8%)

coefficient to assess the internal consistency of the items with an Staff Position

alpha coefficient of 0.70 as the lower threshold for good reliability Management and administration 86 (17.5%)

[25]. Additionally, we evaluated if any items, when removed,

Medical doctors and dental 22 (4.5%)

substantially changed the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients. To assess

convergent validity, we examined the association between each of Nurse and midwife 130 (26.4%)

the individual survey items and the two overall measures of staff Other health professional 94 (19.1%)

satisfaction: ‘‘How would you rate this health facility as a place to Other support staff 72 (14.6%)

work on a scale of 1 (the worst) to 10 (the best)?’’ and ‘‘I would Missing 88 (17.9%)

recommend this health facility to other workers as a good place to

work.’’ We created summary scores for each factor by summing doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079053.t001

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org 4 November 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 11 | e79053

Instrument for Assessing Employee Satisfaction

Validity and Internal Consistency country in Africa, but it was only intended to measure health

The data supported three factors, or constructs, as hypothe- worker motivation and not overall job satisfaction.

sized: (1) relationships with management and supervisors, (2) job The SEHC survey represents a critical step in the pathway of

content, and (3) relationships with coworkers. Results from the addressing human resource issues necessary to help meet the

Scree test also suggested three distinct factors evidenced by the Millennium Development Goals as well as a situation with

point at which the curve began to level off. Each retained item had characteristics necessary for a successful scale up. This survey

a factor loading of 0.40 or higher on at least one of the factors and has been shown to be reliable, valid and easy to implement within

demonstrated strong construct validity (Table 2). Three items the hospital and health care setting to measure the satisfaction of

loaded on both job content and relationships with management all health care workers, a critical component for tools that are

and supervisors factors (Table 2). We dropped two items due to helpful in scale up [27]. Additionally, political support has been

inadequate variability or loadings ,0.40 for all factors. A third cited as an important component of effective scale-up framework

item was dropped because its removal resulted in significantly (P- [27,28,29], influencing the desirability for adoption and assimila-

value ,0.05) increased Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. These tion of an intervention [28], and has been noted to be an integral

modifications resulted in a total of 18 survey items on specific component for many successfully scaled up interventions in low-

aspects of employee experience plus two measures of overall staff and middle-income countries [30,31,32,33,34]. The Ethiopian

satisfaction for a 20-item final survey instrument (Figure 1). Ministry of Health demonstrated a leadership commitment to

Internal consistency of the items in each of the three factors using the SEHC survey by adopting it into the national

indicated good to excellent reliability (Cronbach alpha coefficients reformation guidelines and including a SEHC overall staff

were 0.89, 0.70 and 0.70 for factors 1–3 respectively). satisfaction score into the key performance indicators reported

The associations between the summary scores for each of the annually by hospitals to the government. Although this study

factors and the overall staff satisfaction measures were statistically shows implementation within one low-income country only, it

demonstrates a process and tool that could be applicable to other

significant (all P-values ,0.001) (Table 3). The magnitude of the

low-income countries and suggests that future testing of this survey

associations between overall staff satisfaction items and two of the

in other low-income countries is warranted to test the generaliz-

summary scores (one measuring the employee’s relationship with

ability of the SEHC survey.

management and supervisors and one measuring job content)

Several additional issues are important to recognize in order to

indicated moderate effect sizes (correlation coefficients ranged

promote the proper administration of the survey in the healthcare

from 0.40 to 0.44) [25]. The association between overall staff

setting. Training in data collection and analysis is necessary. As

satisfaction measures and the summary score measuring relation-

briefly noted in the methods, our training program provided

ships with coworkers was statistically significant but of more

detailed instruction on survey management. We advised which

modest in magnitude (correlation coefficients 0.14 and 0.15).

staff members should be involved in the data collection process, we

identified a human resources or quality improvement staff

Discussion member to be responsible for arranging the survey distribution,

The SEHC survey, developed for use in Ethiopian health care and we ensured that a trained and independent individual was

facilities with diverse types of staff, was shown to have strong available to assist staff who could not read with survey completion.

construct validity, excellent internal consistency and modest This person was trained to not attempt to explain or interpret

convergent validity. Although the instrument should be tested in questions, which might create bias, but merely to read the

additional low-income settings, these early data suggest this 20- questions out loud. Additionally, a database in Microsoft Access

item survey may be both practical and valid in assessing employee was developed and distributed, which produces a final report that

satisfaction in resource-limited hospitals and health centers in low- summarizes responses for each question. The database also has

income countries like Ethiopia. As countries turn to improve the additional capabilities, such as comparing changes in both overall

quality of health care and seek to recruit and retain a strong health category averages as well as individual question averages within

workforce, the availability of practical tools to assess employee categories. Last, the training package included a brief introduction

satisfaction is paramount. Data from such assessments can be to the four stages of the Plan Do Study Act (PDSA) Cycle [35] as a

method of introducing change based on the analysis of survey

important inputs to managerial decisions seeking to create

results [35,36].

organizational culture where staff flourish and provide high

In addition, ensuring confidentiality of respondents is vital in

quality health services to people in need.

order to encourage truthful responses by employees. In order to

To our knowledge, SEHC is the first survey that successfully

maintain confidentiality, we recommend that the data collector

captures satisfaction across all levels of employees within both

should provide envelopes in which completed surveys may be

hospital and health clinic facilities in a low-income country. Of the

placed to maintain anonymity, as well as sealed collection boxes

five existing surveys from which we extracted and modified

for employees to return their completed survey. Confidentiality

questions, the Job Satisfaction Survey [7] was most relevant, as it

should be explained to employees through promotional posters

was designed to capture job satisfaction levels of all employees in

that also provide logistical details and encourage staff to complete

an organization; however it was not designed specifically for the

the survey. We stressed that employees should never feel that they

health care setting. Both the Emergency Physician Job Satisfaction

might be punished for what they report on a survey, and that

Instrument [8] and the Measure of Job Satisfaction survey [9] participation is voluntary.

were designed solely for the hospital setting, and only targeted

Last, specifying the minimum number of surveys to be collected

specific populations (emergency physicians and community from each facility should be informed by the statistical power

nurses). The job satisfaction scale to study the correlation between needed to compare sites and analyze differences in single facilities

job satisfaction and turnover intent [6] was designed for use in over time. By ensuring that we collected large enough of a sample

rural South Africa but solely for nurses in clinics. Lastly, the to reach at least 80% power, we feel confident that our results

Motivation Outcome Constructs and Questions [10] was useful, as provide the accurate conclusions. For future applications of this

it was also designed for use in hospitals in a similar developing survey, we recommended that the survey be distributed annually

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org 5 November 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 11 | e79053

Instrument for Assessing Employee Satisfaction

Table 2. Factor analysis of staff satisfaction survey item (N = 492).

Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

Relationship with Job Content Relationships with Original source reference*

Management & Supervisors Coworkers

Factor Analysis*

Q1. The management of this 0.66 – – 8, 10, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21

organization is supportive of me.

Q2. I receive the right amount of 0.63 – – 8, 10, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21

support and guidance from my direct

supervisor.

Q3. I am provided with all trainings 0.47 – – 6, 7, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20

necessary for me to perform my job.

Q4. I have learned many new job 0.45 – – 6, 7, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20

skills in this position.

Q5. I feel encouraged by my 0.72 – – 8, 10, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21

supervisor

to offer suggestions and

improvements.

Q6. The management makes changes 0.70 – – 8, 10, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21

based on my suggestions and feedback.

Q7. I am appropriately recognized 0.59 0.44 – 13, 16

when I perform well at my regular

work duties.

Q8. The organization rules make it 0.50 0.40 – 10,21

easy

for me to do a good job.

Q10. I have adequate opportunities to 0.45 0.40 – 6, 7, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20

develop my professional skills.

Q13. My work assignments are 0.46 – – 21

always

clearly explained to me.

Q14. My work is evaluated based on a 0.43 – – 21

fair system of performance standards.

Q9. I am satisfied with my chances for – 0.41 – 6, 10, 13, 17

promotion.

Q11. I have an accurate written job – 0.46 – 21

description.

Q12. The amount of work I am – 0.42 – 12, 14, 16

expected to finish each week is

reasonable.

Q15. My department provides all the – 0.47 – 6, 7, 12, 13, 18

equipment, supplies, and resources

necessary for me to perform my duties.

Q16. The buildings, grounds and – 0.55 – 7, 8, 15

layout of this health facility are

adequate for me to perform my work

duties.

Q17. My coworkers and I work well – – 0.65 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 16, 18

together.

Q18. I feel I can easily communicate – – 0.60 21

with members from all levels of this

organization.

*–‘ Indicates that questions have a factor loading of ,0.4.

*Indicates the reference number for the original source of each SEHC survey question.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079053.t002

at a consistent time in order to minimize seasonal externalities. Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations.

Additionally, in order to maximize the generalizability of our First, we did not examine if employee satisfaction measured by this

results, careful attention was paid to provide the survey to staff instrument could be influenced by management interventions, but

members from all shifts and areas to be as inclusive and we anticipate, based on cognitive testing and management theory,

representative of the overall hospital and health center staff that employee satisfaction could be influenced by management.

population as possible. Future studies are required to assess changes in employee

satisfaction in response to management changes. Second, the

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org 6 November 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 11 | e79053

Instrument for Assessing Employee Satisfaction

Table 3. Convergent validity: Correlation coefficients for scales with overall staff satisfaction measures (N = 492).

Factor 1 Factor 2 Factor 3

Relationship with Management & Job Content Relationships with Coworkers

Supervisors

Correlation Coefficient (p-value) Correlation Coefficient (p-value) Correlation Coefficient

(p-value)

Q20. How would you rate this health facility 0.43 (,0.001) 0.41 (,0.001) 0.14 (0.003)

as a place to work on a scale of 1 (the worst)

to 10 (the best)?

Q19. I would recommend this health facility 0.42 (,0.001) 0.40 (,0.001) 0.15 (0.001)

to other workers as a good place to work.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079053.t003

instrument was developed specifically for the Ethiopian context of the SEHC survey into Ethiopian health care facilities has ample

and may produced biased estimates of employee satisfaction in leadership support, evident by the adoption of the survey by the

other countries if not tested and validated first. Before we can Ethiopian Ministry of Health into the national reformation

concluded that the SEHC is a generalizable instrument, findings guidelines and the presence of a SEHC overall staff satisfaction

should be replicated in other settings to clarify that our results are score into the key performance indicators reported by hospitals to

not affected by cultural elements specific to Ethiopia. Additional the government on an annual basis. Such support is critical for the

studies should consider adaptations to ensure the instrument successful integration of staff satisfaction measures into routine

captures key components of employee satisfaction in local settings. healthcare facility management, leading to potential remediation

Last, we had relatively few physicians who completed the survey of problems that reduce staff satisfaction and exacerbate excessive

and no staff that were employed in private sector facilities, where workforce shortages.

experiences may differ substantially. As a result, we may have

underestimated the importance of specific items to staff satisfac- Acknowledgments

tion. Although this instrument was applicable to physicians, a

physician-specific tool may allow for greater focus on issues of The authors of this study would like to acknowledge the Ethiopian Federal

primary importance to physicians. Ministry of Health for their help in facilitating the development of the

SEHC survey tool.

Conclusions

Author Contributions

The introduction of consistent and reliable measures of staff

Conceived and designed the experiments: RA ZM TL EHB. Performed

satisfaction is crucial in order to address poor employee retention the experiments: RA ZM DT TL. Analyzed the data: MEC JTT EHB.

rates, which threaten the successful achievement of the Millenni- Wrote the paper: RA MEC EHB.

um Development Goals in developing countries. The introduction

References

1. WHO (2006) The World Health Report 2006: Working Together for Health. 12. Ajiboye P, Yussuf A (2009) Psychological morbidity and job satisfaction amongst

Geneva, Switzerland. medical interns at a Nigerian teaching hospital. African journal of Psychiatry 12:

2. Elzinga G, Degu J, Gebrekidane M, Samrawit N (2010) Human Resources for 303–304.

Health Implications of Scaling Up For Universal Access to HIV/AIDS 13. Chirdan O, Akosu J, Ejembi C, Bassi A, Zoakah A (2009) Perceptions of working

Prevention, Treatment, and Care: Ethiopia Rapid Situational Analysis. In: conditions amongst health workers in state-owned facilities in northeastern

Group GHWATW, editor. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Nigeria. Annals of African Medicine 8: 243–249.

3. Dreesch N, Dolea C, Dal Poz MR, Goubarev A, Adams O, et al. (2005) An 14. Hagopian A, Zuyderduin A, Kyobutungi N, Yumkella F (2009) Job satisfaction

approach to estimating human resource requirements to achieve the Millennium and morale in the Ugandan health workforce. Health Affairs 28: w863–875.

Deelopment Goals. Health Policy and Planning 20: 267–276. 15. Mathauer I, Imhoff I (2006) Health worker motivation in Africa: the role of non-

4. Kebede S, Mantopoulos J, Ramanadhan S, Cherlin E, Gebeyehu M, et al. financial incentives and human resource management tools. Human Resources

(2012) Educating leaders in hospital management: a pre-post study in Ethiopian for Health 4.

hospitals. Global Public Health 7: 164–174. 16. McAuliffe E, Manafa O, Maseko F, Bowie C, White E (2009) Understanding job

5. Initiative USGH (2011) Global Health Initiative: Ethiopia Strategy. Washington satisfaction amongst mid-level cadres in Malawi: the contribution of organisa-

DC: US State Department tional justice. Reproductive Health Matters 17: 80–90.

6. Delobelle P, Rawlinson JL, Ntuli S, Malatsi I, Decock R, et al. (2011) Job 17. Mueller C, McCloskey J (1990) Nurses’ job satisfaction: a proposed measure.

satisfaction and turnover intent of primary healthcare nurses in rural South Nursing Research 39: 113–117.

Africa: a questionnaire survey. J Adv Nurs 67: 371–383. 18. Ntabaye M, Scheutz F, Poulsen S (1999) Job satisfaction amongst rural medical

7. Spector PE (1985) Measurement of human service staff satisfaction: development aides providing emergency oral health care in rural Tanzania. Community

of the Job Satisfaction Survey. Am J Community Psychol 13: 693–713. Dental Health 16: 40–44.

19. Nyathi M, Jooste K (2008) Working conditions that contribute to absenteeism

8. Lloyd S, Streiner D, Hahn E, Shannon S (1994) Development of the emergency

among nurses in a provincial hospital in the Limpopo Province. Curationis 31:

physician job satisfaction measurement instrument. Am J Emerg Med 12: 1–10.

28–37.

9. Traynor M, Wade B (1993) The development of a measure of job satisfaction for

20. Pillay R (2009) Work satisfaction of professional nurses in South Africa: a

use in monitoring the morale of community nurses in four trusts. J Adv Nurs 18:

comparative analysis of the public and private sectors. Human Resources for

127–136.

Health 7.

10. Mbindyo PM, Blaauw D, Gilson L, English M (2009) Developing a tool to 21. Songstad N, Rekdal O, Massay D, Blystad A (2011) Perceived unfairness in

measure health worker motivation in district hospitals in Kenya. Human working conditions: the case of public health services in Tanzania. BMC Health

Resources for Health 7. Serv Res 11.

11. Agyepong I, Anafi P, Asiamah E, Ansah E, Ashon D, et al. (2004) Health worker 22. Willis GB, Royston P, Bercini D (1991) The use of verbal report methods in the

(internal customer) satisfaction and motivation in the public sector in Ghana. development and testing of survey questionnaires. Applied Cognitive Psychology

International journal of health planning and management 19: 319–336. 5: 251–267.

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org 7 November 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 11 | e79053

Instrument for Assessing Employee Satisfaction

23. Willis GB, Schechter S (1997) Evaluation of Cognitive Interviewing Techniques: 31. Wilson D, Ford N, Ngammee V, Chua A, Kyaw Kyaw M (2007) HIV

Do the Results Generalize to the Field? Bulletin de Methodologie Sociologique Prevention, Care, and Treatment in Two Prisons in Thailand. PLoS Medicine

55: 40–66. 4: 988–992.

24. Cattell RB (1966) The Scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate 32. Khatri GR, Frieden TR (2002) Rapid DOTS expansion in India. WHO Bulletin

behavior research 1: 245–276. 80: 457–463.

25. Cohen J (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and 33. Kestler E, Valencia L, Del Valle V, Silva A (2006) Scaling up post-abortion care

Psychological Measurement 20: 37–46. in Guatemala: initial successes at national level Reproductive Health Matters 14:

26. Rubin DB (1987) Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: 138–147.

John Wiley. 34. Bhandari N, Kabir AK, Salam MA (2008) Mainstreaming nutrition into

27. Yamey G (2011) Scaling up global health interventions: a proposed framework. maternal and child health programmes: scaling up of exclusive breastfeeding.

PLoS Medicine 8. Maternal and Child Nutrition 4: 5–23.

28. Atun R, de Jongh T, Secci F, Ohiri K, Adeyi O (2009) Integration of targeted 35. Service NH (2013) Plan, Do, Study, Act (PDSA) Quality and service

health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. improvement tools. NHS Institute for innovation and improvement. London,

Health Policy and Planning 25: 104–111.

UK.

29. Rogers EM (1995) Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press.

36. Berwick DM (1996) A Primer on Leading the Improvement of Systems. BMJ.

30. Dickson KE, Tran NT, Samuelson JL, Njeuhmeli E, Cherutich P, et al. (2011)

Voluntary medical male circumcision: a framework analysis of policy and

program implementation in easter and southern Africa. PLoS Medicine 8.

PLOS ONE | www.plosone.org 8 November 2013 | Volume 8 | Issue 11 | e79053

View publication stats

You might also like

- Vasan Eye Care Hospital ProjectDocument86 pagesVasan Eye Care Hospital Projectkavilankutty100% (1)

- Research and Practice in Human Resource ManagementDocument6 pagesResearch and Practice in Human Resource ManagementGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- 9 PDFDocument9 pages9 PDFGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- Pone 0079053Document9 pagesPone 0079053Diksha KashyapNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction SurveyDocument9 pagesJob Satisfaction SurveyHammad TariqNo ratings yet

- Human Resources For Health: Developing A Tool To Measure Health Worker Motivation in District Hospitals in KenyaDocument11 pagesHuman Resources For Health: Developing A Tool To Measure Health Worker Motivation in District Hospitals in Kenyaanaliza laboratorijNo ratings yet

- Motivation and Factors Affecting It Among Health Professionals in The Public Hospitals, Central EthiopiaDocument12 pagesMotivation and Factors Affecting It Among Health Professionals in The Public Hospitals, Central EthiopiavNo ratings yet

- BMC Health Services Research: Motivation and Retention of Health Workers in Developing Countries: A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesBMC Health Services Research: Motivation and Retention of Health Workers in Developing Countries: A Systematic ReviewHafsa NasirNo ratings yet

- Webster 2011Document11 pagesWebster 2011Ontivia Setiani WahanaNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Rewards and Nurses' Work Motivation in Addis Ababa HospitalsDocument6 pagesRelationship Between Rewards and Nurses' Work Motivation in Addis Ababa Hospitalszaenal abidinNo ratings yet

- Developing A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan AfricaDocument11 pagesDeveloping A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan Africaallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Iranian Staff Nurses' Views of Their Productivity and Human ResourceDocument11 pagesIranian Staff Nurses' Views of Their Productivity and Human Resourcekhalil21No ratings yet

- Articulos Sobre CaphsDocument11 pagesArticulos Sobre CaphsJulioNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction With Clinical Laboratory SerdfgafDocument23 pagesCustomer Satisfaction With Clinical Laboratory SerdfgafcathialphaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Job Satisfaction of NursesDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Job Satisfaction of Nursesaflshtabj100% (1)

- Positive Practice Environments Influence Job Satisfaction of Primary Health Care Clinic Nursing Managers in Two South African ProvincesDocument14 pagesPositive Practice Environments Influence Job Satisfaction of Primary Health Care Clinic Nursing Managers in Two South African ProvincesErin IreneriinNo ratings yet

- Implementing Health Care Reform: Implications For Performance of Public Hospitals in Central EthiopiaDocument16 pagesImplementing Health Care Reform: Implications For Performance of Public Hospitals in Central EthiopiaÌßrãhïm ÄhmêdNo ratings yet

- JOB SATISFACTION OF HEALTH CARE WORKERS AshryDocument40 pagesJOB SATISFACTION OF HEALTH CARE WORKERS AshryJAHARA PANDAPATANNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Motivation Among Healthcare SLRDocument24 pagesDeterminants of Motivation Among Healthcare SLRyazanNo ratings yet

- Developing A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan AfricaDocument11 pagesDeveloping A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan Africaallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Human Resources For HealthDocument10 pagesHuman Resources For HealthzpazpaNo ratings yet

- Nurse Turnover A Literature Review. International Journal of Nursing StudiesDocument4 pagesNurse Turnover A Literature Review. International Journal of Nursing Studiesluwop1gagos3No ratings yet

- Chapter 1-3 FinalDocument52 pagesChapter 1-3 FinalDENNIS OWUSU-SEKYERENo ratings yet

- MQA Lab CepDocument19 pagesMQA Lab CepShaffan AbbasiNo ratings yet

- Saudi Journal of Business and Management Studies (SJBMS) : Ahmad Mohammad RbehatDocument10 pagesSaudi Journal of Business and Management Studies (SJBMS) : Ahmad Mohammad Rbehatneha singhNo ratings yet

- 26 Kohli EtalDocument6 pages26 Kohli EtaleditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Delivery SystemDocument14 pagesHealthcare Delivery Systemapi-3554840420% (1)

- Health Care Workers Motivation and Retention Approaches of Health Workersin Ethiopia A Scoping ReviewDocument7 pagesHealth Care Workers Motivation and Retention Approaches of Health Workersin Ethiopia A Scoping ReviewBSIT2C-REYES, ChristianNo ratings yet

- Impact of Human Resources Management On The Quality of Health Care at The General Reference Hospital of KalemieDocument9 pagesImpact of Human Resources Management On The Quality of Health Care at The General Reference Hospital of KalemiemaniNo ratings yet

- Patient Satisfaction With Nursing Care in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument12 pagesPatient Satisfaction With Nursing Care in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisgiviNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Retensi 2Document20 pagesJurnal Retensi 2tasyaNo ratings yet

- Qip Project PPT SlidesDocument2 pagesQip Project PPT Slidesapi-297799336No ratings yet

- High Rates of Burnout Among Maternal Health Staff at A Referral Hospital in Malawi: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument22 pagesHigh Rates of Burnout Among Maternal Health Staff at A Referral Hospital in Malawi: A Cross-Sectional StudyRoan Khaye CuencoNo ratings yet

- Research MethodologyDocument18 pagesResearch Methodologygmprocurement11No ratings yet

- Barriers and Facilitators To The Implementation of Lay Health Worker Programmes To Improve Access To Maternal and Child Health: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis (Review)Document5 pagesBarriers and Facilitators To The Implementation of Lay Health Worker Programmes To Improve Access To Maternal and Child Health: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis (Review)ArisNo ratings yet

- Hlongwa 2021Document9 pagesHlongwa 2021barrazahealthNo ratings yet

- ReactionpaperdevelopinganeffectivehealthcareworkforceplanningmodelDocument5 pagesReactionpaperdevelopinganeffectivehealthcareworkforceplanningmodelapi-310212918No ratings yet

- An Exploration of The Role of Hospital Committees To Enhance ProductivityDocument11 pagesAn Exploration of The Role of Hospital Committees To Enhance ProductivityLogan BoehmNo ratings yet

- Human Resources For HealthDocument8 pagesHuman Resources For Healthdenie_rpNo ratings yet

- Sources of Community Health Worker Motivation: A Qualitative Study in Morogoro Region, TanzaniaDocument12 pagesSources of Community Health Worker Motivation: A Qualitative Study in Morogoro Region, TanzaniaNurul pattyNo ratings yet

- Using Staffing Ratios For Workforce Planning: Evidence On Nine Allied Health ProfessionsDocument8 pagesUsing Staffing Ratios For Workforce Planning: Evidence On Nine Allied Health ProfessionstikamdxNo ratings yet

- Sister Blessing Project.Document41 pagesSister Blessing Project.ayanfeNo ratings yet

- Tonursj 11 108 PDFDocument16 pagesTonursj 11 108 PDFAnonymous OzgEr1FNvdNo ratings yet

- Quality Improvement ProjectDocument13 pagesQuality Improvement Projectapi-384138456No ratings yet

- Qip ProjectDocument12 pagesQip Projectapi-297797784No ratings yet

- Journal of Social Economics Research: Bassel Asaad Habeeb MahmoudDocument16 pagesJournal of Social Economics Research: Bassel Asaad Habeeb MahmoudBassel AsaadNo ratings yet

- NRHM Eleventh Five Year PlanDocument82 pagesNRHM Eleventh Five Year PlanSourav KunduNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Delivery Systems Improvement ProjectDocument12 pagesHealthcare Delivery Systems Improvement Projectapi-356232401No ratings yet

- Implementing Servant Leadership Atcleveland Clinic - A Case StudyDocument13 pagesImplementing Servant Leadership Atcleveland Clinic - A Case StudyKatherine LinNo ratings yet

- 08-06-2021-1623140416-6-Impact - Ijrbm-1. Ijrbm - "HR Retention Practices in Hospitals" - Validating The Measurement ScaleDocument8 pages08-06-2021-1623140416-6-Impact - Ijrbm-1. Ijrbm - "HR Retention Practices in Hospitals" - Validating The Measurement ScaleImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- GJHS 7 341Document17 pagesGJHS 7 341mandeep kaurNo ratings yet

- Math JournalDocument8 pagesMath Journalmars6esaunggulNo ratings yet

- JLi HRH ReportDocument217 pagesJLi HRH ReportJay-ar RetesNo ratings yet

- Measuring Community Nurses Job Satisfaction Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesMeasuring Community Nurses Job Satisfaction Literature ReviewafmzkbuvlmmhqqNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 19 13486 v2Document15 pagesIjerph 19 13486 v2Csanyi EditNo ratings yet

- Patient Safety Culture Status and Its Predictors Among Healthcare WorkersDocument7 pagesPatient Safety Culture Status and Its Predictors Among Healthcare Workerskristina dewiNo ratings yet

- Thesis Hospital AdministrationDocument8 pagesThesis Hospital Administrationjanaclarkbillings100% (1)

- Role of Health Surveys in National Health Information Systems: Best-Use ScenariosDocument28 pagesRole of Health Surveys in National Health Information Systems: Best-Use ScenariosazfarNo ratings yet

- Health RecordsDocument36 pagesHealth RecordsMatthew NdetoNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Barriers and Facilitators To The Implementation of An Action Plan To Strengthen The Midwifery Professional Role: A Moroccan Case StudyDocument27 pagesAnalyzing Barriers and Facilitators To The Implementation of An Action Plan To Strengthen The Midwifery Professional Role: A Moroccan Case StudyAnisah Tifani MaulidyantiNo ratings yet

- Strategies to Explore Ways to Improve Efficiency While Reducing Health Care CostsFrom EverandStrategies to Explore Ways to Improve Efficiency While Reducing Health Care CostsNo ratings yet

- Disasters, Hope and Globalization: Exploring Self-Identification With Global Consumer Culture in JapanDocument22 pagesDisasters, Hope and Globalization: Exploring Self-Identification With Global Consumer Culture in JapanGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- Gradual Internationalization Vs Born-Global/International New Venture ModelsDocument29 pagesGradual Internationalization Vs Born-Global/International New Venture ModelsGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- Practice Problems - Probability TheoryDocument3 pagesPractice Problems - Probability TheoryGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- Comment On "Consumer Cultural Identity ": Global Citizenship and ReactanceDocument5 pagesComment On "Consumer Cultural Identity ": Global Citizenship and ReactanceGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- Foreign Retail Banner Longevity: Carol FinneganDocument24 pagesForeign Retail Banner Longevity: Carol FinneganGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- Temporal Dynamism in Country of Origin Effect: The Malleability of Italians ' Perceptions Regarding The British SixtiesDocument24 pagesTemporal Dynamism in Country of Origin Effect: The Malleability of Italians ' Perceptions Regarding The British SixtiesGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Factors Affecting The Quality of Work Life Balance Amongst Employees: Based On Indian IT SectorDocument10 pagesA Study On The Factors Affecting The Quality of Work Life Balance Amongst Employees: Based On Indian IT SectorGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 4Document33 pagesChapter - 4GDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- 13 PDFDocument18 pages13 PDFGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- 9 PDFDocument9 pages9 PDFGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Impact of Empowerment On Employee Performance: The Mediating Role of AppraisalDocument14 pagesA Study On The Impact of Empowerment On Employee Performance: The Mediating Role of AppraisalGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Impact of Empowerment On Employee Performance: The Mediating Role of AppraisalDocument14 pagesA Study On The Impact of Empowerment On Employee Performance: The Mediating Role of AppraisalGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- Identifying The Factors Affecting Work-Life Balance of Employees in Banking SectorDocument4 pagesIdentifying The Factors Affecting Work-Life Balance of Employees in Banking SectorGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- A Study of Relationship Between Job Stress, Quality of Working Life and Turnover Intention Among Hospital EmployeesDocument18 pagesA Study of Relationship Between Job Stress, Quality of Working Life and Turnover Intention Among Hospital EmployeesGDKR ReddyNo ratings yet

- Mathematics: Quarter 1 - Module 8: Division of Whole Numbers by Decimals Up To 2 Decimal PlacesDocument34 pagesMathematics: Quarter 1 - Module 8: Division of Whole Numbers by Decimals Up To 2 Decimal PlacesJohn Thomas Satimbre100% (1)

- Pistons To JetsDocument41 pagesPistons To JetsRon Downey100% (2)

- 12B TB Book PDF-1 PDFDocument113 pages12B TB Book PDF-1 PDFامل العودة طالب100% (1)

- Shortest Route ProblemDocument7 pagesShortest Route ProblemkaushalmightyNo ratings yet

- Product Description: Mark II Electric Fire Pump ControllersDocument2 pagesProduct Description: Mark II Electric Fire Pump ControllersBill Kerwin Nava JimenezNo ratings yet

- Benstones Instruments IMPAQ ELITE 4 CanalesDocument8 pagesBenstones Instruments IMPAQ ELITE 4 CanalesmauriciojjNo ratings yet

- The Development of Self-Regulation Across Early ChildhoodDocument37 pagesThe Development of Self-Regulation Across Early ChildhoodvickyreyeslucanoNo ratings yet

- Dibrugarh AirportDocument30 pagesDibrugarh AirportRafikul RahemanNo ratings yet

- WINPROPDocument296 pagesWINPROPEfrain Ramirez Chavez100% (2)

- PC3000 6 PDFDocument8 pagesPC3000 6 PDFRocioSanchezCalderonNo ratings yet

- R Reference Manual Volume 1Document736 pagesR Reference Manual Volume 1PH1628No ratings yet

- Employee Training & DevelopmentDocument27 pagesEmployee Training & DevelopmentEnna Gupta100% (2)

- Catálogo Bombas K3V y K5VDocument15 pagesCatálogo Bombas K3V y K5VRamón Rivera100% (2)

- Model Course 1.07 PDFDocument75 pagesModel Course 1.07 PDFShiena CamineroNo ratings yet

- Zen and The ArtDocument3 pagesZen and The ArtMaria GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Nimble Number Logic Puzzle II QuizDocument1 pageNimble Number Logic Puzzle II QuizpikNo ratings yet

- Volume AdministrationDocument264 pagesVolume AdministrationeviyipyipNo ratings yet

- Proces CostingDocument14 pagesProces CostingKenDedesNo ratings yet

- 11th English BE Confident 5 Test Questions With Answer PDF DownloadDocument57 pages11th English BE Confident 5 Test Questions With Answer PDF Downloadbsai2749No ratings yet

- Business Freedom: An Animated Powerpoint TemplateDocument19 pagesBusiness Freedom: An Animated Powerpoint TemplateKevin LpsNo ratings yet

- Appositives and AdjectiveDocument2 pagesAppositives and AdjectiveRinda RiztyaNo ratings yet

- Process Flow ChartDocument22 pagesProcess Flow ChartKumar Ashutosh100% (1)

- Spare Parts Catalogue: AXLE 26.18 - (CM8118) REF: 133821Document8 pagesSpare Parts Catalogue: AXLE 26.18 - (CM8118) REF: 133821Paulinho InformáticaNo ratings yet

- Planificare Calendaristică Anuală Pentru Limba Modernă 1 - Studiu Intensiv. Engleză. Clasa A Vi-ADocument6 pagesPlanificare Calendaristică Anuală Pentru Limba Modernă 1 - Studiu Intensiv. Engleză. Clasa A Vi-Acatalina marinoiuNo ratings yet

- Item Wise Rate TenderDocument5 pagesItem Wise Rate TenderB-05 ISHA PATELNo ratings yet

- "Twist Off" Type Tension Control Structural Bolt/Nut/Washer Assemblies, Steel, Heat Treated, 120/105 Ksi Minimum Tensile StrengthDocument8 pages"Twist Off" Type Tension Control Structural Bolt/Nut/Washer Assemblies, Steel, Heat Treated, 120/105 Ksi Minimum Tensile StrengthMohammed EldakhakhnyNo ratings yet

- Staff Data Format-AUCDocument1 pageStaff Data Format-AUCSenthil KumarNo ratings yet

- 4 Quarter Performance Task in Statistics and ProbabilityDocument5 pages4 Quarter Performance Task in Statistics and ProbabilitySHS Panaguiton Emma Marimel HUMSS12-ANo ratings yet

- Learning Activity Sheet Computing Probabilities and Percentiles Under The Normal CurveDocument5 pagesLearning Activity Sheet Computing Probabilities and Percentiles Under The Normal CurveJhon Loyd Nidea Pucio100% (1)

- Productivity and Leadership SkillsDocument22 pagesProductivity and Leadership SkillsDan Jezreel EsguerraNo ratings yet