Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Descallar vs. CA

Descallar vs. CA

Uploaded by

Dara CompuestoCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- DIONISIO B. COLOMA, JR vs. HON. SANDIGANBAYANDocument2 pagesDIONISIO B. COLOMA, JR vs. HON. SANDIGANBAYANLearsi AfableNo ratings yet

- Clearfield DoctrineDocument2 pagesClearfield DoctrineEmre Murat Varlık100% (6)

- Motion To Reduce BailDocument3 pagesMotion To Reduce BailYulo Vincent PanuncioNo ratings yet

- Department of Education Culture and Sports Now Department of Education Et Al V Heirs of Regino Banguilan Et AlDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education Culture and Sports Now Department of Education Et Al V Heirs of Regino Banguilan Et AlSanjeev J. SangerNo ratings yet

- PAMACOvs REPUBLICDocument2 pagesPAMACOvs REPUBLICFred GoNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro DigestDocument3 pagesCiv Pro DigestAnonymous 4321No ratings yet

- Rule 57 Cases (Originals)Document76 pagesRule 57 Cases (Originals)Anonymous Ig5kBjDmwQNo ratings yet

- Olsen Case & Tanchan Case DigestsDocument4 pagesOlsen Case & Tanchan Case DigestsjorockyNo ratings yet

- Ticzon v. Media PostDocument3 pagesTiczon v. Media PostKatherine NavarreteNo ratings yet

- Legend Hotel v. RealuyoDocument2 pagesLegend Hotel v. RealuyoJunmer OrtizNo ratings yet

- @emiliano Court Townhouses Homeowners Association v. Dioneda, A.C. No. 5162 (2003Document13 pages@emiliano Court Townhouses Homeowners Association v. Dioneda, A.C. No. 5162 (2003James OcampoNo ratings yet

- Lorenza Ortega v. CA, 1998Document4 pagesLorenza Ortega v. CA, 1998Randy SiosonNo ratings yet

- Serg's Products, Inc. v. PCI Leasing and Finance, Inc., G.R. No. 137705Document9 pagesSerg's Products, Inc. v. PCI Leasing and Finance, Inc., G.R. No. 137705dondzNo ratings yet

- Phil Products Co, vs. Primateria, Societe Anonyme PourDocument5 pagesPhil Products Co, vs. Primateria, Societe Anonyme PourMaria Cristina MartinezNo ratings yet

- CD - 14. Tecson VS GutierrezDocument2 pagesCD - 14. Tecson VS GutierrezMykaNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila Second Division: Supreme CourtDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila Second Division: Supreme CourtChris InocencioNo ratings yet

- Shoemart Vs CADocument4 pagesShoemart Vs CACel C. CaintaNo ratings yet

- DE LA RIVA DigestDocument2 pagesDE LA RIVA DigestChristine Rose Bonilla LikiganNo ratings yet

- Service Specialists v. Sherriff of ManilaDocument3 pagesService Specialists v. Sherriff of ManilaAnjNo ratings yet

- Blackmer v. United StatesDocument1 pageBlackmer v. United StatescrlstinaaaNo ratings yet

- BF Corporation v. CA, 288 SCRA 267 (1998) FactsDocument1 pageBF Corporation v. CA, 288 SCRA 267 (1998) FactsMie TotNo ratings yet

- Baens vs. Sempio, Ac No 10378, June 9, 2014Document1 pageBaens vs. Sempio, Ac No 10378, June 9, 2014kateNo ratings yet

- Andrada Vs PhilhinoDocument12 pagesAndrada Vs PhilhinoRam Rael VillarNo ratings yet

- 15 JOS Managing Builders Vs United Overseas BankDocument2 pages15 JOS Managing Builders Vs United Overseas Banktimothy100% (1)

- Reyes vs. DiazDocument1 pageReyes vs. DiazJan Mar Gigi GallegoNo ratings yet

- Noceda vs. Court of Appeals (Property Case)Document3 pagesNoceda vs. Court of Appeals (Property Case)jokuanNo ratings yet

- 59 People Vs AgulayDocument2 pages59 People Vs AgulayJanno SangalangNo ratings yet

- Fabillo v. Iac 195 Scra 28Document5 pagesFabillo v. Iac 195 Scra 28Debbie YrreverreNo ratings yet

- Sarigumba - Cruz v. PahatiDocument3 pagesSarigumba - Cruz v. PahatiNorberto Sarigumba IIINo ratings yet

- Gabrito vs. Court of Appeals 167 SCRA 771, November 24, 1988Document12 pagesGabrito vs. Court of Appeals 167 SCRA 771, November 24, 1988mary elenor adagioNo ratings yet

- Almeda vs. Bathala Marketing Industries, 542 SCRA 470Document3 pagesAlmeda vs. Bathala Marketing Industries, 542 SCRA 470Gem Martle PacsonNo ratings yet

- Central Surety v. CN HodgesDocument12 pagesCentral Surety v. CN Hodgeskrys_elleNo ratings yet

- Su Zhi Shan V PeopleDocument1 pageSu Zhi Shan V PeopleBreth1979No ratings yet

- Machinery & Engineering Supplies, Inc. Vs CA 96 Phil 70 (1954)Document2 pagesMachinery & Engineering Supplies, Inc. Vs CA 96 Phil 70 (1954)Sarah Jade LayugNo ratings yet

- Fontana Development Corp. (FDC) v. Sascha VukasinovicDocument3 pagesFontana Development Corp. (FDC) v. Sascha VukasinovicKarl SaysonNo ratings yet

- Republic V CaDocument1 pageRepublic V CaRhodz Coyoca EmbalsadoNo ratings yet

- Fortune Life Insurance V Judge LuczonDocument3 pagesFortune Life Insurance V Judge LuczonElah ViktoriaNo ratings yet

- Laguna Transportation Co vs. SSSDocument3 pagesLaguna Transportation Co vs. SSSmyschNo ratings yet

- Climaco and Azcarraga For Plaintiff-Appellee. T. de Los Santos For Defendants-AppellantsDocument3 pagesClimaco and Azcarraga For Plaintiff-Appellee. T. de Los Santos For Defendants-AppellantsJL GENNo ratings yet

- ADR Case DoctrinesDocument7 pagesADR Case DoctrinesMichaela Anne CapiliNo ratings yet

- Utf-8 - 5 Rosales V AlfonsoDocument1 pageUtf-8 - 5 Rosales V Alfonsocmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Defensor-Santiago vs. COMELECDocument2 pagesDefensor-Santiago vs. COMELECJS DSNo ratings yet

- Santiago V GonzalesDocument1 pageSantiago V GonzalesKat JolejoleNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz vs. Sosing, 94 Phil. 260Document1 pageDela Cruz vs. Sosing, 94 Phil. 260RussellNo ratings yet

- Development Bank of The Philippines vs. Court of Appeals, Et - AlDocument2 pagesDevelopment Bank of The Philippines vs. Court of Appeals, Et - AlJanine CastroNo ratings yet

- Balagtas v. RomilloDocument2 pagesBalagtas v. RomilloBea Charisse MaravillaNo ratings yet

- Eugenia Lichauco Et Al., Plaintiffs and Appellants, vs. Faustino Lichauco, Defendant and AppellantDocument3 pagesEugenia Lichauco Et Al., Plaintiffs and Appellants, vs. Faustino Lichauco, Defendant and AppellantLorjyll Shyne Luberanes TomarongNo ratings yet

- Lagula, Et Al. vs. Casimiro, Et AlDocument2 pagesLagula, Et Al. vs. Casimiro, Et AlMay RMNo ratings yet

- Active WoodDocument2 pagesActive WoodCE SherNo ratings yet

- (Good Moral Character) 1 - Fr. Aquino Vs PascuaDocument3 pages(Good Moral Character) 1 - Fr. Aquino Vs PascuaFaye Jennifer Pascua PerezNo ratings yet

- Macalalag v. OmbudsmanDocument2 pagesMacalalag v. OmbudsmanChimney sweepNo ratings yet

- Borje V CFIDocument1 pageBorje V CFIJL A H-DimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Topic Date Case Title GR No Doctrine: Criminal Procedure 2EDocument1 pageTopic Date Case Title GR No Doctrine: Criminal Procedure 2EKattelsNo ratings yet

- Rule 6Document5 pagesRule 6Ezekiel T. MostieroNo ratings yet

- Rocha V Prats - Co.Document3 pagesRocha V Prats - Co.Cathy Belgira100% (1)

- 4.santos Evangelista v. Alto Surety and Insurance Co. Inc. (103 Phil 401)Document7 pages4.santos Evangelista v. Alto Surety and Insurance Co. Inc. (103 Phil 401)James OcampoNo ratings yet

- Extra Judicial Activities of JudgesDocument44 pagesExtra Judicial Activities of JudgesNabby MendozaNo ratings yet

- Buan v. Matugas - DIGESTDocument2 pagesBuan v. Matugas - DIGESTKarez MartinNo ratings yet

- 1 Jonald O. Torreda v. InvestmentDocument22 pages1 Jonald O. Torreda v. InvestmentCharlene MillaresNo ratings yet

- Descallar v.digeSTDocument3 pagesDescallar v.digeSTHv EstokNo ratings yet

- Provisional Remedies Case DigestDocument2 pagesProvisional Remedies Case DigestTanya PimentelNo ratings yet

- Descallar Vs CADocument1 pageDescallar Vs CAJL A H-DimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Decision Sum of MoneyDocument3 pagesDecision Sum of MoneyDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Actual Case of ControversyDocument120 pagesActual Case of ControversyDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Relative ConstitutionalityDocument31 pagesRelative ConstitutionalityDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- 316 U.S. 129 (1942) - 2Document11 pages316 U.S. 129 (1942) - 2Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Intervention,: (G.R. No. 155001. May 5, 2003)Document157 pagesIntervention,: (G.R. No. 155001. May 5, 2003)Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 119673 - 1Document55 pagesG.R. No. 119673 - 1Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Vicente J. Francisco and Francisco Zandueta For Petitioner. Solicitor-General Ozaeta and Ramon Diokno For RespondentDocument6 pagesVicente J. Francisco and Francisco Zandueta For Petitioner. Solicitor-General Ozaeta and Ramon Diokno For RespondentDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Norton v. Shelby County - Orthodox Vs Operative FactDocument18 pagesNorton v. Shelby County - Orthodox Vs Operative FactDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Resolution Purisima, J.:: (G.R. No. 131124. March 29, 1999)Document49 pagesResolution Purisima, J.:: (G.R. No. 131124. March 29, 1999)Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. CA, G.R. No. 163604, May 6, 2005Document2 pagesRepublic vs. CA, G.R. No. 163604, May 6, 2005Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Pacific Bank v. CA, G.R. No. 109373, March 1995Document8 pagesPacific Bank v. CA, G.R. No. 109373, March 1995Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. CA, G.R. No. 163604, May 6, 2005Document5 pagesRepublic vs. CA, G.R. No. 163604, May 6, 2005Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Solivio v. CA, G.R. No. 83484, Feb 12, 1990Document11 pagesSolivio v. CA, G.R. No. 83484, Feb 12, 1990Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Central Sawmill vs. Alto InsuranceDocument3 pagesCentral Sawmill vs. Alto InsuranceDara Compuesto0% (1)

- Lee v. CA, G.R. No. 118387, Oct 11, 2001Document15 pagesLee v. CA, G.R. No. 118387, Oct 11, 2001Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Sebastian v. V Alino, 224 SCRA 256 (1993) KDocument2 pagesSebastian v. V Alino, 224 SCRA 256 (1993) KDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Rivera v. Talavera, G.R. Nos. L-16280 and L-16805, May 30, 1961Document3 pagesRivera v. Talavera, G.R. Nos. L-16280 and L-16805, May 30, 1961Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Chavez v. CA, G.R. No. 174356, January 20, 2010Document2 pagesChavez v. CA, G.R. No. 174356, January 20, 2010Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- La Tondena vs. CADocument2 pagesLa Tondena vs. CADara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Provional RemediesDocument7 pagesProvional RemediesDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Ago v. CA, 16 SCRA 81 (1966)Document2 pagesAgo v. CA, 16 SCRA 81 (1966)Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Graño v. Hon - Paredes, G.R. No. L-27019, March 4, 1927Document2 pagesGraño v. Hon - Paredes, G.R. No. L-27019, March 4, 1927Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Pacific Merchndising Corp., Consolacion Insurance & Surety Co., 73 SCRA 564Document3 pagesPacific Merchndising Corp., Consolacion Insurance & Surety Co., 73 SCRA 564Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Case Digests PDF FreeDocument22 pagesCriminal Procedure Case Digests PDF FreeJoy ParasNo ratings yet

- Miranda RightsDocument3 pagesMiranda Rightssamilyrodriguez606060No ratings yet

- Calcutta HC Indranil Khan Writ Petition OrderDocument3 pagesCalcutta HC Indranil Khan Writ Petition OrderThe WireNo ratings yet

- Section 138 NI ActDocument28 pagesSection 138 NI ActDHIKSHITNo ratings yet

- Marvin O. Sanders v. Robert L. McCrady Individually and As Adjutant General of The State of South Carolina, 537 F.2d 1199, 4th Cir. (1976)Document4 pagesMarvin O. Sanders v. Robert L. McCrady Individually and As Adjutant General of The State of South Carolina, 537 F.2d 1199, 4th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Judge's Order in Stardust CaseDocument2 pagesJudge's Order in Stardust CaseZachary HansenNo ratings yet

- Statement in Reponse To Alfonso Rodriguez Death PenaltyDocument1 pageStatement in Reponse To Alfonso Rodriguez Death PenaltyRob PortNo ratings yet

- Waiver of Illegality of ArrestDocument2 pagesWaiver of Illegality of ArrestJai DouglasNo ratings yet

- Fifth Semester of Three Year LL.B. Examination, January 2012 Civil Procedure Code and Limitation ActDocument3 pagesFifth Semester of Three Year LL.B. Examination, January 2012 Civil Procedure Code and Limitation ActRanjan BaradurNo ratings yet

- Poe Vs Macapagal-ArroyoDocument2 pagesPoe Vs Macapagal-ArroyoMichaella RamirezNo ratings yet

- RCBC v. CIRDocument2 pagesRCBC v. CIRDaLe AparejadoNo ratings yet

- Court-Fees Act, 1870 (Act No. VII of 1870)Document12 pagesCourt-Fees Act, 1870 (Act No. VII of 1870)VAT A2ZNo ratings yet

- N434 Notice of Change of SolicitorDocument1 pageN434 Notice of Change of Solicitorvivalakhan7178No ratings yet

- Ruffy v. Chief of StaffDocument2 pagesRuffy v. Chief of StaffBart VantaNo ratings yet

- Licensing With Special Emphasis On Compulsory Licensing: Berne Convention (Paris Act, 1971)Document9 pagesLicensing With Special Emphasis On Compulsory Licensing: Berne Convention (Paris Act, 1971)Jai VermaNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Tilted ArcDocument13 pagesThe Politics of Tilted ArcVal Ravaglia100% (1)

- DD Basu 1-4Document213 pagesDD Basu 1-4Krishan AggarwalNo ratings yet

- GR No. 9865Document2 pagesGR No. 9865Raym TrabajoNo ratings yet

- Ekup vs. EtitsDocument2 pagesEkup vs. EtitsAldous Fred DiquiatcoNo ratings yet

- Arrest PDF WarrantDocument27 pagesArrest PDF WarrantLaxmi WankhedeNo ratings yet

- Petition For Bail of Patrick Baltazar and Angelica DecenaDocument3 pagesPetition For Bail of Patrick Baltazar and Angelica Decenafelix reyesNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 151866 September 9, 2004 SOLEDAD CARPIO, Petitioner, vs. LEONORA A. VALMONTE, Respondent. Tinga, J.Document3 pagesG.R. No. 151866 September 9, 2004 SOLEDAD CARPIO, Petitioner, vs. LEONORA A. VALMONTE, Respondent. Tinga, J.Law CoNo ratings yet

- MOTION FOR EXECUTION - TechnoDocument3 pagesMOTION FOR EXECUTION - TechnoFlorencio AlimanNo ratings yet

- Sahara CaseDocument5 pagesSahara CaseShehnila Athar100% (1)

- Mock Board Criminal Law 1Document11 pagesMock Board Criminal Law 1Noel Cervantes Aras100% (2)

- Federal and State ProhibitorsDocument3 pagesFederal and State Prohibitors13WMAZNo ratings yet

- WP 10772 2024 Order 08-May-2024 DigiDocument2 pagesWP 10772 2024 Order 08-May-2024 Digianushkashrivastava878No ratings yet

- Rodolfo vs. PeopleDocument2 pagesRodolfo vs. PeopleMinorka Sushmita Pataunia SantoluisNo ratings yet

Descallar vs. CA

Descallar vs. CA

Uploaded by

Dara CompuestoOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Descallar vs. CA

Descallar vs. CA

Uploaded by

Dara CompuestoCopyright:

Available Formats

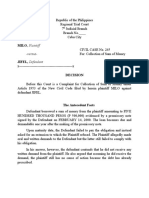

Descallar v. CA (G.R. No.

106473 July 12, 1993)

Facts:

On August 9, 1991, respondent Camilo Borromeo, a realtor, filed against Antonietta O.

Descallar (petitioner) a civil complaint for the recovery of three (3) parcels of land and the house built

thereon in the possession of the petitioner and registered in her name under TCT Nos. 24790,

24791 and 24792 of the Registry of Deeds for the City of Mandaue. Borromeo alleged that he

purchased the property from Wilhelm Jambrich, an Austrian national and former lover of the

petitioner for many years until he deserted her for the favors of another woman. Borromeo filed an

action to recover the ownership and possession of the house and lots from Descallar and asked for

the issuance of new transfer certificates of title in his name.

In her answer, Descallar alleged that the property belongs to her as the registered owner

thereof; that Borromeo's vendor, Wilhelm Jambrich, is an Austrian, hence, not qualified to acquire or

own real property in the Philippines. Borromeo asked the trial court to appoint a receiver for the

property during the pendency of the case. Despite the petitioner's opposition, Judge Mercedes Golo-

Dadole granted the application for receivership and appointed her clerk of court as receiver with a

bond of P250,000.00.

Petitioner sought relief in the Court of Appeals by a petition for certiorari which the CA. Hence, this

petition for certiorari under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court.

Issue:

Whether the trial court gravely abused its discretion in appointing a receiver for real property

registered in the name of the petitioner in order to transfer its possession from the petitioner to the

court-appointed receiver.

Ruling:

Yes. The appointment of a receiver is not proper where the rights of the parties (one of

whom is in possession of the property), are still to be determined by the trial court. Relief by way of

receivership is equitable in nature, and a court of equity will not ordinarily appoint a receiver where

the rights of the parties depend on the determination of adverse claims of legal title to real property

and one party is in possession. Only when the property is in danger of being materially injured or

lost, as by the prospective foreclosure of a mortgage thereon for non-payment of the mortgage loans

despite the considerable income derived from the property, or if portions thereof are being occupied

by third persons claiming adverse title thereto, may the appointment of a receiver be justified.

In this case, there is no showing that grave or irremediable damage may result to respondent

Borromeo unless a receiver is appointed. The property in question is real property, hence, it is

neither perishable or consummable. Even though it is mortgaged to a third person, there is no

evidence that payment of the mortgage obligation is being neglected. In any event, the private

respondent's rights and interests, may be adequately protected during the pendency of the case by

causing his adverse claim to be annotated on the petitioner's certificates of title.

Another flaw in the order of receivership is that the person whom the trial judge appointed as

receiver is her own clerk of court. This practice has been frowned upon by this Court.

You might also like

- DIONISIO B. COLOMA, JR vs. HON. SANDIGANBAYANDocument2 pagesDIONISIO B. COLOMA, JR vs. HON. SANDIGANBAYANLearsi AfableNo ratings yet

- Clearfield DoctrineDocument2 pagesClearfield DoctrineEmre Murat Varlık100% (6)

- Motion To Reduce BailDocument3 pagesMotion To Reduce BailYulo Vincent PanuncioNo ratings yet

- Department of Education Culture and Sports Now Department of Education Et Al V Heirs of Regino Banguilan Et AlDocument4 pagesDepartment of Education Culture and Sports Now Department of Education Et Al V Heirs of Regino Banguilan Et AlSanjeev J. SangerNo ratings yet

- PAMACOvs REPUBLICDocument2 pagesPAMACOvs REPUBLICFred GoNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro DigestDocument3 pagesCiv Pro DigestAnonymous 4321No ratings yet

- Rule 57 Cases (Originals)Document76 pagesRule 57 Cases (Originals)Anonymous Ig5kBjDmwQNo ratings yet

- Olsen Case & Tanchan Case DigestsDocument4 pagesOlsen Case & Tanchan Case DigestsjorockyNo ratings yet

- Ticzon v. Media PostDocument3 pagesTiczon v. Media PostKatherine NavarreteNo ratings yet

- Legend Hotel v. RealuyoDocument2 pagesLegend Hotel v. RealuyoJunmer OrtizNo ratings yet

- @emiliano Court Townhouses Homeowners Association v. Dioneda, A.C. No. 5162 (2003Document13 pages@emiliano Court Townhouses Homeowners Association v. Dioneda, A.C. No. 5162 (2003James OcampoNo ratings yet

- Lorenza Ortega v. CA, 1998Document4 pagesLorenza Ortega v. CA, 1998Randy SiosonNo ratings yet

- Serg's Products, Inc. v. PCI Leasing and Finance, Inc., G.R. No. 137705Document9 pagesSerg's Products, Inc. v. PCI Leasing and Finance, Inc., G.R. No. 137705dondzNo ratings yet

- Phil Products Co, vs. Primateria, Societe Anonyme PourDocument5 pagesPhil Products Co, vs. Primateria, Societe Anonyme PourMaria Cristina MartinezNo ratings yet

- CD - 14. Tecson VS GutierrezDocument2 pagesCD - 14. Tecson VS GutierrezMykaNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila Second Division: Supreme CourtDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila Second Division: Supreme CourtChris InocencioNo ratings yet

- Shoemart Vs CADocument4 pagesShoemart Vs CACel C. CaintaNo ratings yet

- DE LA RIVA DigestDocument2 pagesDE LA RIVA DigestChristine Rose Bonilla LikiganNo ratings yet

- Service Specialists v. Sherriff of ManilaDocument3 pagesService Specialists v. Sherriff of ManilaAnjNo ratings yet

- Blackmer v. United StatesDocument1 pageBlackmer v. United StatescrlstinaaaNo ratings yet

- BF Corporation v. CA, 288 SCRA 267 (1998) FactsDocument1 pageBF Corporation v. CA, 288 SCRA 267 (1998) FactsMie TotNo ratings yet

- Baens vs. Sempio, Ac No 10378, June 9, 2014Document1 pageBaens vs. Sempio, Ac No 10378, June 9, 2014kateNo ratings yet

- Andrada Vs PhilhinoDocument12 pagesAndrada Vs PhilhinoRam Rael VillarNo ratings yet

- 15 JOS Managing Builders Vs United Overseas BankDocument2 pages15 JOS Managing Builders Vs United Overseas Banktimothy100% (1)

- Reyes vs. DiazDocument1 pageReyes vs. DiazJan Mar Gigi GallegoNo ratings yet

- Noceda vs. Court of Appeals (Property Case)Document3 pagesNoceda vs. Court of Appeals (Property Case)jokuanNo ratings yet

- 59 People Vs AgulayDocument2 pages59 People Vs AgulayJanno SangalangNo ratings yet

- Fabillo v. Iac 195 Scra 28Document5 pagesFabillo v. Iac 195 Scra 28Debbie YrreverreNo ratings yet

- Sarigumba - Cruz v. PahatiDocument3 pagesSarigumba - Cruz v. PahatiNorberto Sarigumba IIINo ratings yet

- Gabrito vs. Court of Appeals 167 SCRA 771, November 24, 1988Document12 pagesGabrito vs. Court of Appeals 167 SCRA 771, November 24, 1988mary elenor adagioNo ratings yet

- Almeda vs. Bathala Marketing Industries, 542 SCRA 470Document3 pagesAlmeda vs. Bathala Marketing Industries, 542 SCRA 470Gem Martle PacsonNo ratings yet

- Central Surety v. CN HodgesDocument12 pagesCentral Surety v. CN Hodgeskrys_elleNo ratings yet

- Su Zhi Shan V PeopleDocument1 pageSu Zhi Shan V PeopleBreth1979No ratings yet

- Machinery & Engineering Supplies, Inc. Vs CA 96 Phil 70 (1954)Document2 pagesMachinery & Engineering Supplies, Inc. Vs CA 96 Phil 70 (1954)Sarah Jade LayugNo ratings yet

- Fontana Development Corp. (FDC) v. Sascha VukasinovicDocument3 pagesFontana Development Corp. (FDC) v. Sascha VukasinovicKarl SaysonNo ratings yet

- Republic V CaDocument1 pageRepublic V CaRhodz Coyoca EmbalsadoNo ratings yet

- Fortune Life Insurance V Judge LuczonDocument3 pagesFortune Life Insurance V Judge LuczonElah ViktoriaNo ratings yet

- Laguna Transportation Co vs. SSSDocument3 pagesLaguna Transportation Co vs. SSSmyschNo ratings yet

- Climaco and Azcarraga For Plaintiff-Appellee. T. de Los Santos For Defendants-AppellantsDocument3 pagesClimaco and Azcarraga For Plaintiff-Appellee. T. de Los Santos For Defendants-AppellantsJL GENNo ratings yet

- ADR Case DoctrinesDocument7 pagesADR Case DoctrinesMichaela Anne CapiliNo ratings yet

- Utf-8 - 5 Rosales V AlfonsoDocument1 pageUtf-8 - 5 Rosales V Alfonsocmv mendozaNo ratings yet

- Defensor-Santiago vs. COMELECDocument2 pagesDefensor-Santiago vs. COMELECJS DSNo ratings yet

- Santiago V GonzalesDocument1 pageSantiago V GonzalesKat JolejoleNo ratings yet

- Dela Cruz vs. Sosing, 94 Phil. 260Document1 pageDela Cruz vs. Sosing, 94 Phil. 260RussellNo ratings yet

- Development Bank of The Philippines vs. Court of Appeals, Et - AlDocument2 pagesDevelopment Bank of The Philippines vs. Court of Appeals, Et - AlJanine CastroNo ratings yet

- Balagtas v. RomilloDocument2 pagesBalagtas v. RomilloBea Charisse MaravillaNo ratings yet

- Eugenia Lichauco Et Al., Plaintiffs and Appellants, vs. Faustino Lichauco, Defendant and AppellantDocument3 pagesEugenia Lichauco Et Al., Plaintiffs and Appellants, vs. Faustino Lichauco, Defendant and AppellantLorjyll Shyne Luberanes TomarongNo ratings yet

- Lagula, Et Al. vs. Casimiro, Et AlDocument2 pagesLagula, Et Al. vs. Casimiro, Et AlMay RMNo ratings yet

- Active WoodDocument2 pagesActive WoodCE SherNo ratings yet

- (Good Moral Character) 1 - Fr. Aquino Vs PascuaDocument3 pages(Good Moral Character) 1 - Fr. Aquino Vs PascuaFaye Jennifer Pascua PerezNo ratings yet

- Macalalag v. OmbudsmanDocument2 pagesMacalalag v. OmbudsmanChimney sweepNo ratings yet

- Borje V CFIDocument1 pageBorje V CFIJL A H-DimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Topic Date Case Title GR No Doctrine: Criminal Procedure 2EDocument1 pageTopic Date Case Title GR No Doctrine: Criminal Procedure 2EKattelsNo ratings yet

- Rule 6Document5 pagesRule 6Ezekiel T. MostieroNo ratings yet

- Rocha V Prats - Co.Document3 pagesRocha V Prats - Co.Cathy Belgira100% (1)

- 4.santos Evangelista v. Alto Surety and Insurance Co. Inc. (103 Phil 401)Document7 pages4.santos Evangelista v. Alto Surety and Insurance Co. Inc. (103 Phil 401)James OcampoNo ratings yet

- Extra Judicial Activities of JudgesDocument44 pagesExtra Judicial Activities of JudgesNabby MendozaNo ratings yet

- Buan v. Matugas - DIGESTDocument2 pagesBuan v. Matugas - DIGESTKarez MartinNo ratings yet

- 1 Jonald O. Torreda v. InvestmentDocument22 pages1 Jonald O. Torreda v. InvestmentCharlene MillaresNo ratings yet

- Descallar v.digeSTDocument3 pagesDescallar v.digeSTHv EstokNo ratings yet

- Provisional Remedies Case DigestDocument2 pagesProvisional Remedies Case DigestTanya PimentelNo ratings yet

- Descallar Vs CADocument1 pageDescallar Vs CAJL A H-DimaculanganNo ratings yet

- Decision Sum of MoneyDocument3 pagesDecision Sum of MoneyDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Actual Case of ControversyDocument120 pagesActual Case of ControversyDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Relative ConstitutionalityDocument31 pagesRelative ConstitutionalityDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- 316 U.S. 129 (1942) - 2Document11 pages316 U.S. 129 (1942) - 2Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Intervention,: (G.R. No. 155001. May 5, 2003)Document157 pagesIntervention,: (G.R. No. 155001. May 5, 2003)Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 119673 - 1Document55 pagesG.R. No. 119673 - 1Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Vicente J. Francisco and Francisco Zandueta For Petitioner. Solicitor-General Ozaeta and Ramon Diokno For RespondentDocument6 pagesVicente J. Francisco and Francisco Zandueta For Petitioner. Solicitor-General Ozaeta and Ramon Diokno For RespondentDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Norton v. Shelby County - Orthodox Vs Operative FactDocument18 pagesNorton v. Shelby County - Orthodox Vs Operative FactDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Resolution Purisima, J.:: (G.R. No. 131124. March 29, 1999)Document49 pagesResolution Purisima, J.:: (G.R. No. 131124. March 29, 1999)Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. CA, G.R. No. 163604, May 6, 2005Document2 pagesRepublic vs. CA, G.R. No. 163604, May 6, 2005Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Pacific Bank v. CA, G.R. No. 109373, March 1995Document8 pagesPacific Bank v. CA, G.R. No. 109373, March 1995Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. CA, G.R. No. 163604, May 6, 2005Document5 pagesRepublic vs. CA, G.R. No. 163604, May 6, 2005Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Solivio v. CA, G.R. No. 83484, Feb 12, 1990Document11 pagesSolivio v. CA, G.R. No. 83484, Feb 12, 1990Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Central Sawmill vs. Alto InsuranceDocument3 pagesCentral Sawmill vs. Alto InsuranceDara Compuesto0% (1)

- Lee v. CA, G.R. No. 118387, Oct 11, 2001Document15 pagesLee v. CA, G.R. No. 118387, Oct 11, 2001Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Sebastian v. V Alino, 224 SCRA 256 (1993) KDocument2 pagesSebastian v. V Alino, 224 SCRA 256 (1993) KDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Rivera v. Talavera, G.R. Nos. L-16280 and L-16805, May 30, 1961Document3 pagesRivera v. Talavera, G.R. Nos. L-16280 and L-16805, May 30, 1961Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Chavez v. CA, G.R. No. 174356, January 20, 2010Document2 pagesChavez v. CA, G.R. No. 174356, January 20, 2010Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- La Tondena vs. CADocument2 pagesLa Tondena vs. CADara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Provional RemediesDocument7 pagesProvional RemediesDara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Ago v. CA, 16 SCRA 81 (1966)Document2 pagesAgo v. CA, 16 SCRA 81 (1966)Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Graño v. Hon - Paredes, G.R. No. L-27019, March 4, 1927Document2 pagesGraño v. Hon - Paredes, G.R. No. L-27019, March 4, 1927Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Pacific Merchndising Corp., Consolacion Insurance & Surety Co., 73 SCRA 564Document3 pagesPacific Merchndising Corp., Consolacion Insurance & Surety Co., 73 SCRA 564Dara CompuestoNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Case Digests PDF FreeDocument22 pagesCriminal Procedure Case Digests PDF FreeJoy ParasNo ratings yet

- Miranda RightsDocument3 pagesMiranda Rightssamilyrodriguez606060No ratings yet

- Calcutta HC Indranil Khan Writ Petition OrderDocument3 pagesCalcutta HC Indranil Khan Writ Petition OrderThe WireNo ratings yet

- Section 138 NI ActDocument28 pagesSection 138 NI ActDHIKSHITNo ratings yet

- Marvin O. Sanders v. Robert L. McCrady Individually and As Adjutant General of The State of South Carolina, 537 F.2d 1199, 4th Cir. (1976)Document4 pagesMarvin O. Sanders v. Robert L. McCrady Individually and As Adjutant General of The State of South Carolina, 537 F.2d 1199, 4th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Judge's Order in Stardust CaseDocument2 pagesJudge's Order in Stardust CaseZachary HansenNo ratings yet

- Statement in Reponse To Alfonso Rodriguez Death PenaltyDocument1 pageStatement in Reponse To Alfonso Rodriguez Death PenaltyRob PortNo ratings yet

- Waiver of Illegality of ArrestDocument2 pagesWaiver of Illegality of ArrestJai DouglasNo ratings yet

- Fifth Semester of Three Year LL.B. Examination, January 2012 Civil Procedure Code and Limitation ActDocument3 pagesFifth Semester of Three Year LL.B. Examination, January 2012 Civil Procedure Code and Limitation ActRanjan BaradurNo ratings yet

- Poe Vs Macapagal-ArroyoDocument2 pagesPoe Vs Macapagal-ArroyoMichaella RamirezNo ratings yet

- RCBC v. CIRDocument2 pagesRCBC v. CIRDaLe AparejadoNo ratings yet

- Court-Fees Act, 1870 (Act No. VII of 1870)Document12 pagesCourt-Fees Act, 1870 (Act No. VII of 1870)VAT A2ZNo ratings yet

- N434 Notice of Change of SolicitorDocument1 pageN434 Notice of Change of Solicitorvivalakhan7178No ratings yet

- Ruffy v. Chief of StaffDocument2 pagesRuffy v. Chief of StaffBart VantaNo ratings yet

- Licensing With Special Emphasis On Compulsory Licensing: Berne Convention (Paris Act, 1971)Document9 pagesLicensing With Special Emphasis On Compulsory Licensing: Berne Convention (Paris Act, 1971)Jai VermaNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Tilted ArcDocument13 pagesThe Politics of Tilted ArcVal Ravaglia100% (1)

- DD Basu 1-4Document213 pagesDD Basu 1-4Krishan AggarwalNo ratings yet

- GR No. 9865Document2 pagesGR No. 9865Raym TrabajoNo ratings yet

- Ekup vs. EtitsDocument2 pagesEkup vs. EtitsAldous Fred DiquiatcoNo ratings yet

- Arrest PDF WarrantDocument27 pagesArrest PDF WarrantLaxmi WankhedeNo ratings yet

- Petition For Bail of Patrick Baltazar and Angelica DecenaDocument3 pagesPetition For Bail of Patrick Baltazar and Angelica Decenafelix reyesNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 151866 September 9, 2004 SOLEDAD CARPIO, Petitioner, vs. LEONORA A. VALMONTE, Respondent. Tinga, J.Document3 pagesG.R. No. 151866 September 9, 2004 SOLEDAD CARPIO, Petitioner, vs. LEONORA A. VALMONTE, Respondent. Tinga, J.Law CoNo ratings yet

- MOTION FOR EXECUTION - TechnoDocument3 pagesMOTION FOR EXECUTION - TechnoFlorencio AlimanNo ratings yet

- Sahara CaseDocument5 pagesSahara CaseShehnila Athar100% (1)

- Mock Board Criminal Law 1Document11 pagesMock Board Criminal Law 1Noel Cervantes Aras100% (2)

- Federal and State ProhibitorsDocument3 pagesFederal and State Prohibitors13WMAZNo ratings yet

- WP 10772 2024 Order 08-May-2024 DigiDocument2 pagesWP 10772 2024 Order 08-May-2024 Digianushkashrivastava878No ratings yet

- Rodolfo vs. PeopleDocument2 pagesRodolfo vs. PeopleMinorka Sushmita Pataunia SantoluisNo ratings yet