Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 viewsCooper & Ellram 1993 PDF

Cooper & Ellram 1993 PDF

Uploaded by

Yaduan MaoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Colorscope 1Document6 pagesColorscope 1Oca Chan100% (2)

- Practica Alesca S.ADocument13 pagesPractica Alesca S.AAlondra TorresNo ratings yet

- A4 OdcgDocument8 pagesA4 OdcgOscarCg CRNo ratings yet

- Caso 1 Nutrilak - Identificacion de Problemas y Funciones GerencialesDocument3 pagesCaso 1 Nutrilak - Identificacion de Problemas y Funciones GerencialesDiana Milagros Rafael Acuña100% (2)

- The Concept of Sustainable Development in Pakistan: Full Length Research PaperDocument10 pagesThe Concept of Sustainable Development in Pakistan: Full Length Research PaperMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Implications For Sustainability: Dear Mr. President and Members of CongressDocument2 pagesImplications For Sustainability: Dear Mr. President and Members of CongressMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management 2005 10, 2 ABI/INFORM GlobalDocument12 pagesSupply Chain Management 2005 10, 2 ABI/INFORM GlobalMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Inter-Organizational Decision Coordination: Case StudyDocument12 pagesUnderstanding Inter-Organizational Decision Coordination: Case StudyMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Financial 2015Document64 pagesFinancial 2015Aftab SaadNo ratings yet

- Emergence of Modern RetailingDocument16 pagesEmergence of Modern RetailingMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Respected Sir/Madam Institute of Management Sciences, BZU, Multan Subject: Request For The Permission of Medical LeaveDocument1 pageRespected Sir/Madam Institute of Management Sciences, BZU, Multan Subject: Request For The Permission of Medical LeaveMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- La Théorie de ConsommateurDocument83 pagesLa Théorie de Consommateurabdelrh100% (1)

- 建築圖ALLDocument110 pages建築圖ALL陳俊佐No ratings yet

- CEMEX IntroduccionDocument2 pagesCEMEX Introduccionrokat atNo ratings yet

- Factura SimpleTVDocument2 pagesFactura SimpleTVAlejandro RiveraNo ratings yet

- Sintesis de Los Principios de Contabilidad Generalmente AceptadosDocument7 pagesSintesis de Los Principios de Contabilidad Generalmente AceptadosCarlos HernándezNo ratings yet

- EXAMEN FINAL DE ADMINISTRACIÓN DE MAQUINARIA AGRÍCOLA Julio 2016Document1 pageEXAMEN FINAL DE ADMINISTRACIÓN DE MAQUINARIA AGRÍCOLA Julio 2016Ricardo AndréNo ratings yet

- 02 ESTUDIO-HIDROLOGICO - RumichacaDocument33 pages02 ESTUDIO-HIDROLOGICO - RumichacaJose Norabuena VillarealNo ratings yet

- Desarollo Con Jumbo ElectrohidraulicoDocument11 pagesDesarollo Con Jumbo Electrohidraulicodmamani31No ratings yet

- Guía 2020. GyCDocument70 pagesGuía 2020. GyCDanis GoubaidoulineNo ratings yet

- Procedimiento Manejo de Desechos Peligrosos y No PeligrososDocument6 pagesProcedimiento Manejo de Desechos Peligrosos y No PeligrososInspección refamecaNo ratings yet

- ABSTRACT 16-17 (English)Document707 pagesABSTRACT 16-17 (English)DeepakNo ratings yet

- Cavinkare: Company Website AboutDocument3 pagesCavinkare: Company Website AboutKpvs NikhilNo ratings yet

- 113-S03 Mueller Lehmkuhl GMBH - Anexos en Excel AADocument8 pages113-S03 Mueller Lehmkuhl GMBH - Anexos en Excel AApaocvl892No ratings yet

- Cebu Winland Vs Ong Sia HuaDocument1 pageCebu Winland Vs Ong Sia HuahappypammynessNo ratings yet

- Unidad 2 Contabilidad GeneralDocument18 pagesUnidad 2 Contabilidad GeneralTamaraNo ratings yet

- Síntesis EEADocument7 pagesSíntesis EEAmlorentejimenezNo ratings yet

- Far - Chapter 7Document25 pagesFar - Chapter 7Danica TorresNo ratings yet

- Exp 41575 Servicio de Reubicacion de Estructuras Postes y Redes en El Sistema SecundarioDocument17 pagesExp 41575 Servicio de Reubicacion de Estructuras Postes y Redes en El Sistema SecundarioVANESSAMAMANI QUENTANo ratings yet

- Hernandez Karla U1G4T5Document6 pagesHernandez Karla U1G4T5Melissa VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- MM - TJ - Matematica Financeira - Conferido 7h (1) - Gabaritada 5Document12 pagesMM - TJ - Matematica Financeira - Conferido 7h (1) - Gabaritada 5RicardoAmaralNo ratings yet

- Expediente Tecnico PNX-02Document31 pagesExpediente Tecnico PNX-02Emicko EmiNo ratings yet

- Ejercicios de KardexDocument38 pagesEjercicios de KardexCamila RodriguezNo ratings yet

- OFERTA SAN NICOLAS Rev 04 AventoDocument5 pagesOFERTA SAN NICOLAS Rev 04 AventoNataLiia MonTezNo ratings yet

- Evaluación de Proyectos de Inversión PublicaDocument49 pagesEvaluación de Proyectos de Inversión PublicaEiner Nicolas Berduzco100% (1)

- Laboratorio Muro de Ladrillo SimpleDocument7 pagesLaboratorio Muro de Ladrillo SimpleDeynor MamaniNo ratings yet

- Ejercicio Tabla DinamicaDocument19 pagesEjercicio Tabla DinamicaSonlange Shantall CallerNo ratings yet

Cooper & Ellram 1993 PDF

Cooper & Ellram 1993 PDF

Uploaded by

Yaduan Mao0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views12 pagesOriginal Title

Cooper & Ellram 1993.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views12 pagesCooper & Ellram 1993 PDF

Cooper & Ellram 1993 PDF

Uploaded by

Yaduan MaoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 12

“an integrative

philosophy to manage

the total flow of a

distribution channel from

the supplier to the

ultimate user.”

Characteristics of Supply Chain

Management and the Implications for

Purchasing and Logistics Strategy

Martha C. Cooper

The Ohio State University

Lisa M. Ellram

Arizona State University

Purchasing and logistics.

The concepts of a supply chain and supply chain management are receiving

increased attention as means of becoming or remaining competitive in a globally

challenging environment. What distinguishes supply chain management from other

channel relationships? This paper presents a framework for differentiating between

traditional systems and supply chain management systems. These characteristics,

are then related to the process of establishing and managing a supply chain. A

Particular focus of this paper is on the implications of supply chain management for

Supply chain management is defined as

“an integrative philosophy to manage the

total flow of a distribution channel from the

supplier to the ultimate user” (1]. This means

greater coordination of business processes

and activities, such as inventory

management, across the entire channel and

not just between a few channel pairs. There

is an emerging literature regarding the

concept of a supply chain (2), the advantages

‘of forming supply chains over other

alternatives {3] and the management of

supply chains [4]. Building upon this work,

there is a need to explore what differentiates

a supply chain management approach from

other channel relationships. The

characteristics identified may have different

influences on the process of establishing and

managing a supply chain. Three general

stages of the process are examined: the initial

decision to form or join a supply chain; the

strategic planning before, during, and after

the formation; and the on-going operations of

the supply chain. Thus, the purposes of this

paper are: 1) to identify characteristics of

supply chains and 2) to examine when these

characteristics might affect the channel

management process.

The paper consists of four sections.

Section one is a brief background on supply

chain management. Section two identifies

characteristics that distinguish a supply chain

from other channel relationships. Next, these

characteristics are overlaid on the process of

developing and managing a supply chain

with the roles that purchasing and logistics

play examined in greater detail. The paper

concludes with a brief summary and

suggestions for future research.

The Supply Chain Management

Concept

Supply chain management is viewed as.

lying between fully-vertically-integrated

systems and those where each channel

member operates completely independently

In a fully-vertically-integrated system, the

functions are performed within one

company. One traditional example is the tire

industry where some companies grew their

own rubber, manufactured the tires, and sold

through their own retail stores or directly to

original equipment manufacturers (OEMs).

Economists (51 examined conditions, such as

economies of scale and availability of

suitable outside services, under which

Volume 4, Number 2 1993

Page 13

— — eeeeSeseSeSSsSsSeSeSeSeSeEeEe

functions should be vertically integrated or

should be performed by another entity

(outsourced). Unless there is complete

vertical integration, there is a channel

involving at least two entities.

In fully-vertically-integrated systems,

the structural relationships among the

functions, such as marketing and logistics,

are defined by top management. The

functions will work with each other

indefinitely, so their interactions are more

predictable. When functions are performed

by independent entities with few oF no ties to

one another, the relationships are more

tenuous. The players can change from one

transaction to the next. In contrast, supply

chain management may be likened to a well-

balanced and well-practiced relay team. A

relay team is more competitive when it

practices with the same core lineup so that

each runner knows how to be positioned for

the handoff, While relationships are strongest

among those who directly pass the baton, the

entire team must be coordinated to win the

race. This is the major benefit of supply

chain management. Missed handoffs may

well translate to lost market share in today’s

competitive marketplace.

Development of Supply Chain Management

The term supply chain management

first appears in the logistics literature as an

inventory management approach. Houlihan

[6] describes excess inventory buildup as

akin to snowdrifts against a fence. The more

independent entities, the more fences with

snow drifts and hence, the more inventory in

the system. Supply chain management looks

across the entire channel, rather than just at

the next entity or level.

Many functions and firms must be

involved in the effort to reduce inventory

system-wide. Better information systems can

curtail the need for large safety stocks of

production inputs and finished goods.

Shorter setup times and shorter production

runs keep inventory low but can increase

production costs. These cost increases

should be much less than the savings from

lower inventories.

Reasons for Forming Supply Chains

Three major reasons identified in the

literature and by companies are 1) to reduce

Page 14

inventory investment in the chain, 2) to

increase customer service, and 3) to help

build a competitive advantage for the

channel [7]. The inventory reduction efforts

alone have resulted in significant channel-

wide savings (8]. Increased stock availability

and reduced order cycle time occur through

channel-wide inventory management and

closer coordination among channel members,

[9]. These customer service dimensions

improve provided that only redundant stock

is removed from the system, leaving intact

sufficient safety stock to meet desired service

levels. The amount of safety stock required

may also be lower due to reduced

uncertainty. Examining which firms in the

channel have particular cost advantages,

such as lowest labor rates or costs of capital,

‘can result in advantages for the supply chain

‘as a whole, such as lower prices for products

[10]. Managing the supply chain as an entity

can help create a competitive advantage and

greater profitability [11] for the channel

through coordinated attention to costs, better

customer service, and lower inventories.

Examples

Two scenarios may illustrate the supply

chain management concept. A major

‘objective or a major benefit of establishing a

supply chain is suggested for each example.

Scenario #1 - reduced channel-

wide inventory, increased service

reliability.

Du Pont has reduced order cycle time

and pulled inventory out of some of its

product lines by working with suppliers and

customers. Du Pont concentrated on the

planning process throughout the supply

chain to affect the changes [12]. All

functions focus on customer requirements.

‘Asa result, cycle times have been reduced as

much as one quarter, service reliability has

increased, and there has been significant,

savings in inventory. For example, one

supplier now manages the inventory,

handling and distribution of spare parts. This,

increased supplier responsibility allows Du

Pont to focus on customer - related issues

rather than on managing many suppliers.

Scenario #2 - reduced order cycle

time as a competitive advantage.

The Limited owns approximately 4,400

retail clothing stores under several different

The International joumal of Logistics Managemen

«supply chain

‘management may be

likened to a well-

balanced and well-

practiced relay team.

a channel which enjoys

lower costs than its

ompetitors can allocate

the savings to more

productive uses...

.a supply chain

‘management approach

involves channel-wide

‘management of

inventories.

store names. The Limited also owns MAST

Industries which contracts for the

manufacture of clothing. MAST bids on

supplying various Limited lines and can also

bid for other non-Limited contracts. The

Limited does not own the manufacturing or

materials suppliers. MAST speed sources

from twenty countries. Speed sourcing is

defined as “the shortest possible time to

elapse between identifying a fashion item or

trend and getting it into a customer's

distribution channel in depth" [13]. Logistics

is viewed as a competitive tool in that

garments can be made and distributed to

stores in a short period of time. The 1990's

target is 30 to 35 days. This permits reorders

of more popularly selling items before the

fashion season is over.

Characteristics of Supply Chain

Management

To consider supply chain management

to be a different approach from other channel

relationships, there should. be some

characteristics that could be used to

differentiate it. Based on the literature on

business-to-business relationships {14} and

supply chains [15], as well as discussions

with executives, the following characteristics

‘emerge: inventory management approach,

total cost approach, time horizon, amount of

mutual sharing and monitoring of

information, amount of coordination of

multiple levels in the channel, joint planning,

compatibility of corporate philosophies,

breadth of supplier base, channel leadership,

amount of sharing of risks and rewards, and

the speed of physical and information flows

within and between entities. These

characteristics are contrasted between supply

chain and traditional, independent

relationships in Table 1. Those characteristics

derived from the partnership/ strategic

alliance literature [16], which usually deals

with only two entities, are proposed here for

wider channel acceptance and imple-

mentation than just one channel pair.

Inventory Management Approach

In contrast with each firm establishing

its own inventory management policy

independent of others in the channel, a

supply chain management approach involves

channel-wide management of inventories

117]. This approach does not necessarily

seek to eliminate most of the inventory from

the channel, such as zero inventory or just-

in-time systems, but only the redundant

inventories in the system. This emphasis on

inventory reduction may be a key difference

between supply chain management and

vertical marketing systems, which

concentrate on the control or equity

relationships of firms, such as franchise

agreements,

Cost Efficiencies

A supply chain management approach

implies a channel-wide evaluation of costs to

identify total cost advantages [18]. For

example, some channel members may enjoy

lower borrowing rates, especially when the

supply chain includes international channel

members. Other key areas for analysis are

lowest labor rates, most effective processes,

most capital available, lowest cost of capital,

lowest tax rate, most advantageous logistics

costs, and most depreciation or other tax

advantages [19]. Less-coordinated channel

structures leave each firm to ils own devices

for cost control. However, a channel which

enjoys lower costs than its competitors can

allocate the savings to more productive uses,

such as research and development or

lowering its price to the customer.

‘Time Horizon

An extended time horizon is important

to enduring relationships [20]. Each member

expects its membership in the supply chain

to continue for a considerable if not an

indefinite time into the future. Otherwise,

investments in integrated information

systems and operating systems may be too

high for payback during a shorter

relationship life cycle. While there is often a

fixed contractual time span, the relationship

is expected to extend beyond the life of the

contract indefinitely.

‘Amount of Mutual Information Sharing

and Monitoring

The entire channel is managed more

effectively when members have access to

information pertinent for the conduct of their

business [21]. Information monitoring is not

just down the channel, as from manufacturer

fume 4, Number 2 1993

Page 15

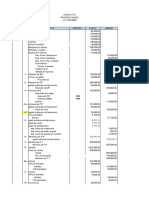

Table 1

‘Traditional and Supply Chain Management

‘Approaches Compared

Element

Inventory

Management Approach

“Traditional

Independent forts

‘Supply Chain

‘Joint eduction in|

‘channel inventories

Total Cost Approach

Minimize firm costs

CChannel-wide cost

efficiencies

"Time Horizon

‘Show term

Long term

“Amount of

Information Sharing

‘and Monitoring

Limited to needs of

Curent transaction

‘As requited for

planning and monitoring

processes

“Amount of

Coordination of

Multiple Levels in the

Channel

‘Single contact for

the transaction between

channel pairs

Multiple contacts

‘between levels in firms

‘and levels of channel

‘Joint Planning

Transaclion-based

On-going

‘Compatibility of

Coxporate

Philosophies

Not relevant

‘Compatibie atleast

for key relationships

Breath of Supplier

Base

tisk

Targe to increase

‘competition ard spread

‘Smale inevoass

‘coordination

‘Channel Leadership

Not needed

Needed for

coordination focus

“Amount of Sharing

Cf Risks and lewards

Each on its own

Fisks and rewards

shared over the long term

“Speed of Operations,

Information and Inventory

Flows

-warerouse™|

orientation (storage,

safety stock) interrupted

ty barriers to lows;

Localized to channel pairs

“DC orientation (inventory

velocity) interconnecting

flows; JIT, Quick Response

across the channel

to customer, but in both directions. It is not

necessary that all channel members have

access to the same information, only that

Which is needed for them to better manage

their supply chain linkages. For example,

certain channel members need to know what

to do in the case of a chemical spill but do

not need to know the proprietary chemical

formulae or production processes. This

approach to information sharing must

pervade the channel for the supply chain

Management concept to exist. In a traditional

channel situation, information exchanged is,

limited to the needs of the current

transaction [22].

Amount of Coordination of Multiple Levels

of the Channel!

Three kinds of coordination can be

identified: across channel members, across

management levels, and across functions. In

traditional, independent systems, the focus is

——

Page 16

‘on the specific transaction between buyer

and seller. The supply chain management

concept implies that most or all members of

the channel coordinate their efforts. For

example, a manufacturer may work with the

supplier’s supplier. While the day-to-day

interaction is most focused on immediate

channel pairs, the goals of the entire channel

guide operations

Several management levels within the

firm are also involved in the supply chain

management process. The top managements

of the various members will be involved in

the planning process. The operational

managers may be in almost constant contact

either verbally or via electronic

communications with their counterparts in

other organizations. There may well be more

contacts at different management levels of

functions and these may occur more

frequently than within traditional channels.

It is important that functions within the

member firms understand the supply chain

Jtis important that

functions within the

member firms

understand the supply

chain management

concept.

The International Journal of Logistics Managemer

lume 4, Number 2

management concept. Strong functional turf

battles are dysfunctional to the overall

operation of the firm, and hence the supply

chain, The silos are being broken down by

team management approaches [23]. The new

focus is on the business processes, such as

order fulfillment. The organization's structure

may be redesigned to better manage the

business processes in a supply chain firm

(24).

Joint Planning

In traditional channel systems, planning

between channel members focuses on the

transaction and is short term, such as the

delivery terms of a particular purchase order.

If the channel is to be more closely

coordinated, then joint planning of such

activities as material flows and development

‘of new products is in order. There is a

continuous process of planning, evaluation,

and improvement over multiple years [25].

‘A key difference for supply chain

management is the wider system planning

than just two levels. While joint planning

may be done in pairs as with partnerships

126}, supply chain management involves

more pairs in the planning process. The

supply chain management concept would

suggest that many entities in the channel

should take part in the planning.

‘Compatibility of Corporate Philosophies

Compatible comporate philosophies are

less important for one-time or infrequent

transactions than for longer term

relationships. Here, the term compatible

corporate philosophies is used to mean

agreement on the basic directions for the

channel, not necessarily similar operating

procedures and certainly not agreement on

every issue. A study of twelve thousand

executives around the world indicated that

compatible corporate cultures was most

important in long term supplier/buyer

relationships (271. Incompatible corporate

cultures make coordination more difficult

and moving the firms in the same direction

less likely [28]. Compatibility goes beyond

individual personalities as the individuals

involved may change over the life of the

corporate relationship. Less compatible

corporate cultures may exist between certain

pairs in supply chains [29], but this makes

the continued relationship more challenging.

Breadth of Supplier Base

Traditional systems often involve

several suppliers of the same materials or

services to increase competition and to

obtain more favorable terms of sale. This

approach also spreads the risk of shutdown if

one supplier becomes suddenly unable to

fulfill the contract or order. The supply chain

management approach suggests that the

supplier base be reduced so that the firms

can be more closely integrated. A reduced

supplier base permits closer management

and coordination of a few relationships [30]

Channel Leadership

Organizations are characterized by

having a top management structure, often

headed by a strong chief executive. The

supply chain clearly needs to have

leadership in order to develop and execute

strategy [31]. Traditionally, channels have a

leader which is an organization which

manages the channel and resolves conflict

(32). tn U.S. consumer channels, large

retailers appear to dominate. However, as

many firms are moving more toward a team

structure internally, and in working with

third parties, a team approach to supply

chain leadership may also emerge.

‘Sharing of Risks and Rewards

Williamson, Palay (33), and others

have suggested that a close relationship

requires that channel members be willing to

share risks and rewards over the long term.

This implies a win-win situation over the life

of the supply chain. In traditional systems,

channel members are relatively independent,

with a short term approach that does not

consider counter-balancing of risks and

rewards over time. If a very strong leader

commands a sufficient market share of the

supplier's business, the supplier may choose

to remain in the supply chain even though

the only sharing of rewards is the privilege of

doing business in the channel, or the sharing

is quite limited. This may be characterized

by a “win-not lose" relationship rather than

the expected “win-win” one.

Speed of Operations

Information systems, such as electronic

data interchange (ED!), can contribute to the

Page 17

Ss

speed of operations through reduced order

cycle times on the purchasing side.

Information technologies such as EDI and

barcoding help manage the flow of goods on

the distribution side, [34] such as faster

picking and dispatching. While these

technologies are currently applied in many

channels, their use is localized by function

or a few channel members. A supply chain

management approach examines the whole

channel and exploits these technologies

channel-wide.

Traditional systems might be

characterized as having a “warehouse”

orientation with emphasis on storage and

large safety stocks to prepare for variations in

demand. There are barriers to the flows of

information and inventory between firms.

The flow of goods is interrupted by stops at

plant warehouses, regional and local

warehouses. Improvements in inventory or

information flows are often localized to

immediate channel pairs. In contrast, the

supply chain approach may be more of a

‘distribution center" orientation emphasizing,

inventory velocity and interconnected

information flows across the entire channel.

Just-in-time and quick response systems

would be the extreme of this approach when

applied system-wide.

‘Assuming a supply chain is to be

formed, the next section addresses how the

characteristics identified might affect the

initial decision, the planning, and the on-

going operation of the supply chain

Establishing and Managing The Supply

Chain

First, the process for establishing a

supply chain is examined with respect to the

characteristics just discussed. Table 2 suggests

a framework to examine how supply chain

management characteristics influence the

Table 2

Planning and Managing the Supply Chain

Element Trilial

Decision’

Planning

Stage’

Inventory

Management Approach

Potential savings

is a major ofiver

‘Channet-wide

valuation

Continued search

for reductions

Total Cost

‘Approach

Potential

‘tigger

“Assess which

‘members have

‘advantages

Exploit cost

advantages

"Time Horizon

Long tem ‘Shomer term

“Amount of Information

Shating and

Nontoring

Planning the

system

Required

“Amount of

Coordination of

Multiple Levels in

the Channel

To establish

philosophy ané

goals

Required

Joint Planning

‘Swaiegic

level

‘Operations

level

Compabiity

Corporate

Philosophies

Prerequisite

‘Confirm

compatibility

Confirmed

‘Breadth of

Supple: Base

Potential

trigger

‘Choose right

suppliers

‘Channel Leadership | Prerequisite

Tnfluence channel

formation

quired for

continued

leadership,

“Amount of Sharing

‘of Fisks and Rewards

Balanced or

“aif inlong run

Wiling to take

short term hits

‘Speed of Operations,

Information and

Inventory Flows

Potential

trigger

Key planning Tnereased

concem

over me ie of he cman

1. The ial Decision votes the evaluation of and decison to orm or ener a supply chain,

2. The Panning Stage includes both ie al planingto establish the supply chan and tne ongoing sratogie planning

‘2. When the Supply Cain eperatonl, there wl be continuing issues for managing the dayto-cay operations.

«athe supply chain

approach may be more

of a “distribution center”

orientation emphasizing

inventory velocity and

interconnected

information flows across

the entire channel.

Page 18

The International Journal of Logistics Managemer

lume 4, Number 2

Tables

ing and Logistics (P & L) Contributions

Purch

to the Management of the Supply Chain (SC)

Element Tritial

Decision

Planning

inventory

Management Approach

‘en top

management to

Hol ientiy

where savings

potent savings

‘Alon top -

‘management to

potent savings.

Total Cost

Approach

Examing PAL

channel cost

advantages

Time Horizon

Long term

‘agreements for

arts and sanvicos

“Arount of Information

Sharing and

Monitoring

‘entity current

systoms, plan

Interfaces

‘Amount ot

Coordination of

Mutiple Levels in

the Channe!

Selection of

tied panies involve P&L

‘oint Planning| ‘dent potential

‘SC participants

Pat

Included

Functional

planning

Compaibitiy of Input on cuture

Corporate

Philosophies

Frontine

interactions

Breadth of

Suppor Bese,

‘Wenily polenta

suppor

Wontor

performance

Prequailying|

suppers

‘Chennel Leaderchip

Facials planning ‘Suppor leaders

goals

‘Amount of Sharing

of Pisks and Rewards

Determine cost

sharing arrangements

Koop track

forP aL

‘Speed of Operations,

Information and

Inventory Flows

Teeny Inventory and

improvement information

‘opportunites

initial decision to form or join a supply chain,

influence planning for the formation of the

supply chain and subsequent strategic

planning, and influence the on-going

‘operation of the supply chain. The roles that

purchasing and logistics can play are

discussed more specifically in relation to

Table 3.

Initial Decision

Supply chain management should not

be entered into without considering potential

benefits and pitfalls 135]. There are several

potential triggers that would initiate the

development of a supply chain management

approach. Of the characteristics discussed in

the previous section, there may be objectives

to: reduce inventory levels, improve total

cost efficiencies, reduce the supplier base,

and/or increase the speed of operations. One

major driver is the quest for channel-wide

inventory reductions. Purchasing and

logistics play key roles here due to their

direct influence on and management of

inventories. Potential cost efficiencies could

be a trigger depending on which ones are

examined prior to the establishment of the

chain. Purchasing and logistics would be in a

position to alert top management about

potential savings from channel-wide

inventory and other cost efficiencies.

‘The decision to reduce the number of

suppliers may cause the firm to review their

entire supplier base philosophy. Reducing

suppliers throughout the supply chain would

move toward a supply chain management

approach. The search for improved speed of

operations, inventory flow, and information

access may also drive @ supply chain

management philosophy.

Compatible corporate philosophies

136} would not be a sufficient reason for

forming a supply chain but may be a

prerequisite for selecting key members to

Page 19

———— SSS

belong to the chain. There should be at least

a willingness to support the goals of the

chain among members selected. Channel

leadership is a prerequisite, because there

must be a “champion” for supply chai

formation and coordination, based on

discussions with executives.

Purchasing and logistics can provide

corporate culture assessments, identify

potential supply chain members, and

evaluate potential increases in the speed of

operations. With the knowledge about

suppliers and customers routinely collected

bby purchasing and logistics, these functions

are in a position to assess areas of strength

and weakness of potential supply chain

members as the number of suppliers is

reduced. Purchasing and logistics also

develop some sense of the potential amount

of cooperation to be expected from other

members. This information can prove quite

valuable when selecting supply chain

members as well as working with them on an

‘on-going basis.

Planning for the Supply Chain Philosophy

Table 2 suggests issues to consider

regarding each supply chain management

clement during the planning stage. There will

be channel-wide searches for the appropriate

places to reduce inventory, reduce other

costs, and increase the speed of the

‘operations, information, and inventory flows

137]. The decisions in these areas will

influence the final form of the supply chain

and its competitiveness. Purchasing and

logistics can identify where inventory savings

are possible, along with manufacturing for

work-in-process levels. All functions can

assess which function costs can be reduced

channel-wide, such as logistics identifying

excess transportation capacity

The firm may not be organized

internally to take advantage of supply chain

membership [38]. More coordinated

information systems and increased sharing of

information are probably needed [39]. Since

purchasing and logistics are in the flow of

information, they are able to suggest changes

to the system for improved coordination,

information flow, and planning of new or

reconfigured distribution networks.

The focus during the initial planning

will be strategic. Building a supply chain will

involve all levels of management. The

overall philosophy and goals of the chain

must be determined. In addition, there will

be discussions regarding how to balance

risks and rewards across members and time.

Without top management support, the

changes in the organization needed to

interface with other supply chain members

will not occur [40]. Top level functional

support is required in order for the other

levels within the function to buy into the

supply chain concept, particularly if turf or

tradition are well-entrenched [41]

Initial and on-going strategic planning

should include input from purchasing and

logistics [42]. Long term decisions about the

buyer-seller relationships will be made at this,

point, such as purchasing agreements for

parts and logistics decisions about

Outsourced services. Purchasing and logistics

can also suggest cost-sharing arrangements

to spread the risks of investments in new

information and distribution networks. The

supplier base will be narrowed as supply

chain members are selected. Prequalifying

suppliers involves examining the ability of

suppliers to fulfill a set of criteria deemed

necessary to provide a consistent, high

quality supply of materials.

The channel leader will have a

profound effect on the character and makeup

‘of the supply chain. Firms will be working

closely to confirm that there is cultural

compatibility. Strategic planning during the

life of the supply chain will be heavily

influenced by the channel leader. This

planning should consider the need to provide

incentives for continued supply chain

participation among channel members.

Implementation and Operation

It is likely that many levels of

management within the firms will be

involved during the implementation phase

and on-going operations. The top levels will

examine more strategic issues of the

relationship, while middle and line managers

will be managing the day-to-day operations.

Frequent communication occurs either

person-to-person or electronically to track

goods movement and the effectiveness of the

interfaces among the firms in the supply

chain, Flexibility or the assumption of short

term difficulties may be required for the

benefit of the supply chain. However, these

are expected to balance out over the length

‘of the relationship [43]

Purchasing and logistics

can provide corporate

culture assessments,

identify potential supply

chain members, and

evaluate potential

increases in the speed of

operations.

je EE NaEEEE

The International journal of Logistics Managemer

Page 20

Target customer service

evels, such as throughput

and order cycle time,

should be agreed upon

across the channel

members and understood

by all levels of

‘management.

The traditional roles of

purchasing and logistics

personnel as inventory

‘managers, information

satherers and dissemina-

tors, and negotiators

should serve the firm

well in the new supply

chain management

atmosphere.

Table 4

Purchasing and Logistics

Contributions to

Supply Chain Management

Provide leadership in the process

Provide negotiation expertise

Present a broad, interfirm perspective

Provide inventory management expertise

Facilitate information links between and within firms

Provide expertise in working with third parties

All levels in the supply chain must

understand the commitments for the supply

chain to operate smoothly. Target customer

service levels, such as throughput and order

cycle time, should be agreed upon across the

channel members and understood by all

levels of management. The methods of

measuring performance, such as what

constitutes fill cate and the means of

monitoring the processes, are designed at the

beginning and maintained by the operations

managers. A goal of supply chain manage-

ment is continuous improvement. This

includes increased speed of operations, as

well as improved information and inventory

flows, due to better coordination and focused

goals across supply chain member

Key Roles of Purchasing and Logistics

Table 4 illustrates how purchasing and

logistics can contribute to establishing and

‘managing the supply chain, They will be key

functions in the operation of the supply

chain and should provide leadership in its

formation and management. In many cases,

they will manage the information flows for

sharing and monitoring purposes. They are

‘on the front line, along with marketing, for

coordinating between firms. They may be in

a good position to assess whether the risks

and rewards are in fact being shared from

purchasing and logistics standpoints

Purchasing and logistics managers should

take advantage of their unique positions and

knowledge to play leadership roles in the

design and implementation of integrated

‘supply chains.

Purchasing and logistics, along with

marketing, have served boundary-spanning

roles OUTSIDE the firm. Purchasing interacts

primarily up the channel with suppliers

while logistics and marketing have

traditionally concentrated on the

downstream aspects with customers and

third party providers. However, logistics

functions have also assisted purchasing to

achieve better coordination of inbound

transportation and warehousing [44]. Both

purchasing and logistics have experience

negotiating contracts and dealing with

outside suppliers in general which can be

utilized in forming supply chain

relationships. Information about the external

environment is collected by both functions

and passed on to the firm,

Both purchasing and logistics have

served key boundary-spanning roles INSIDE

the firms. Purchasing interfaces with the

functions who have purchasing requirements

or changes and with the planning and the

payments functions. Logistics interacts with

marketing via customer service and with

manufacturing with regard to product

availability. Thus, both functions already

have ties with most departments within the

organization. This permits them unique

perspectives on more effective interfirm and

intrafirm communications and integration.

The traditional roles of purchasing and

logistics personnel as inventory managers,

information gatherers and disseminators, and

negotiators should serve the firm well in the

new supply chain management atmosphere,

Conclus

This paper suggests a set of

characteristics that in combination would

iS

dlume 4, Number 2 1993,

Page 21

SSS

differentiate supply chain management

approaches from other channel systems.

These include means of working more

closely together, such as coordination across

firms and management levels within firms,

sharing and monitoring of information, and

joint planning. Supply chain management

also requires a long term orientation; the

relationship is expected to extend over an

indefinite horizon with sharing of risks and

rewards balanced over time. The expected

results include a more competitive channel

through reduced channel-wide inventory,

channel-wide total cost efficiencies, and

faster movement of operations, information,

and inventory. One organization may need

to take a leadership role to manage the

activities and direction of the channel.

The supply chain characteristics

identified may have different levels of

importance at different stages in the process

of establishing and managing supply chains.

Purchasing and logistics functions have

critical roles to play in the success of supply

chains through their knowledge and

expertise, particularly in the areas of

information and inventory management.

These functions should take leadership roles,

in the design and implementation of supply

chain management.

Future research should be designed to

verify the nature of the relationships

suggested by the literature and discussed

here. It is not known whether all of the

characteristics in Table 1 are necessary for a

supply chain management approach to exist

or whether some supersede others. For

example, it may be that a strong channel

leader will force a supply chain system,

regardless of the sharing of risks and rewards

or compatible corporate cultures. Some

specific research questions are listed below

which need to be addressed to advance the

knowledge of supply chain management as

an approach separate from other channel

relationships,

How do supply chain members

more than one level apart

interact?

Is there always coordination more than

one level away? Preliminary case studies and

a review of the literature indicate that some

‘companies do not seem to manage beyond

the adjacent level, leaving those

relationships to be managed by the adjacent

channel member. Other examples perform

joint planning across multiple levels.

How many levels of management

are involved in interfirm

activities?

Ic Is suggested in the present paper that

interfirm management activities occur at the

strategic, tactical, and operational levels

which would involve most levels of

management. The key functions and

management levels should be identified.

‘Are supply chains characterized

by one strong leader or does a

multi-firm leadership approach

also work?

In vertical marketing systems there is a

channel leader, especially for franchise

systems. Does this carry over to supply

chains where the emphasis is on inventory

reduction, cost control, and improved

customer service, as well as providing a

sustainable competitive advantage?

Are all hypothesized character

istics in all supply chains to some

degree or are there key drivers

that must exist while others

appear in varying combinations?

Since the original goal of supply chain

management is system-wide inventory

reduction, this characteristic should exist in

all supply chains. Which others are required,

or appear only in combination with other

characteristics is a matter for future

investigation.

Research on the supply chain

management approach is needed to help

‘guide managers in determining whether they

should initiate or become part of supply

chains. Many of the pieces discussed here

have been developed through the economics

and relationship literatures. However, how

these pieces are put together with channel-

wide inventory management and improved

information technologies represents new

‘opportunities for both business and

academia.

References

[1] Ellram, Lisa M. and Martha C.

Cooper, “Supply Chain Management,

Partnerships, and the Shipper-Third Party

Since the original goal oi

supply chain manage-

ment is system-wide

inventory reduction, this

characteristic should

exist in all supply chains.

————

The International Journal of Logistics Managemer

Page 22

Volume 4, Number 2

Relationship,” International journal of Logistics

‘Management, Vol. 1, No. 2 (1990), pp. 1-10.

[2] Houlihan, John B., ‘International

Supply Chains: A New Approach”,

Management Decision, Vol. 26, No. 3

(1988), pp. 13-19; Jones, Thomas C., and

Daniel W. Riley, "Using Inventory for

Competitive Advantage through Supply

Chain Management”, The International

Journal of Physical Distribution and Materials

‘Management, Vol. 15, No. 5 (1985), pp. 16-

26; Stevens, Graham C., “Integrating the

Supply Chain”, International Journal of

Physical Distribution and Materials

‘Management, Vol. 19, No. 8 (1989), pp. 3-8.

(3] Ellram, Lisa M. and Martha C

Cooper, 1990, opcit, Ellram, Lisa M., “Supply

Chain Management: The Industrial Organ-

ization Perspective,” International Journal of

Physical Distribution and Materials Manage-

ment, Vol. 21, No. 1 (1991), pp. 12-22.

[4] Houlihan, John B., “international

Supply Chain Management’, International

Journal of Physical Distribution and Materials

‘Management, Vol. 15, No. 1 (1985), pp. 22-38;

Lee, Hau L. and Corey Billington, "Managing

Supply Chain inventory: Pitfalls and Oppor-

tunities,” Sloan Management Review, Vol. 33,

No. 3 (Spring, 1992), pp. 65-73; Scott, Charles

and Roy Westbrook, “New Strategic Tools for

Supply Chain Management,” international

Journal of Physical Distribution and Materials

Management, Vol. 21, No. 1/1991), pp.23-33.

{5] Coase, R.M., "The Nature of the

Firm", Economica, Vol. IV (1937), pp. 385-

405; Stigler, George, “The Division of Labor

is Limited by the Extent of the Market”,

reprinted from The Journal of Political

Economy, reprinted from The Organization

of Industry, edited by George Stigler, Irwin:

Homewood, IL, 1968, pp. 129-141,

{6} Houlihan, John B., (1985), op. cit.

{71 Cooper, Martha C., "international

Supply Chain Management: implications for

the Bottom Line," Proceedings of the Society of

Logistics Engineers, Hyattsville, MD: Society of

Logistics Engineers, 1993, pp. 57-60.

[8] Traffic Management, “How Du Pont

Forged a Quality Supply Chain," Vol. 30, No.

6 une, 1991), pp. 55,57.

19} Hewitt, Frederick, “Myths and

Realities of Supply Chain Management,”

Proceedings of the Council of Logistics

Management, Oak Brook, IL: Council of

Logistics Management, 1992, pp. 333-337.

[10] Cavinato, joseph L., “Identifying

Interfirm Total Cost Advantages for Supply

Chain Competitiveness,” International

Journal of Purchasing and Materials

Management, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Fall, 1991),

pp.10-15; Shrank, John K. and Vijay

Govindarajan, ” Strategic Cost Management

and Value Chain,” journal of Cost

Management, Vol. 6, No. 4 (Winter, 1992),

pp. 5-21

(11) Battaglia, Alfred J. and Gene R.

Tyndall, “Working on the Supply Chain,” Chief

Executive, No. 66 (April, 1991), pp. 42-45.

{12] Slater, Lynn M. and Richard P.

Gordon, “Improving Inventory Productivity

by Compressing Cycle Time and Segmenting

the Product Line,” presentation at the

Council of Logistics Management Annual

Meeting, Oak Brook, IL, (October, 1992).

113] Johnson, C. Lee and Martin Trust,

"1000 Hours to Market,” W. Wayne Talarzyk,

ed., Manufacturing Excellence: Strategies for the

2 Ist Century, Proceedings of the Sixth Biennial

W. Arthur Cullman Symposium, Ohio State

University, Columbus, Ohio, (May 20, 1992),

pp. 16-18.

[14] Gardner, John, and Martha Cooper,

“Elements of Strategic Partnership,”

Partnerships: A Natural Evolution in Logistics,

J. E. McKeon ed., Cleveland: Logistics

Resource, inc., 1988, pp. 15-32; Macneil, lan

R,, The New Social Contract, an Inquiry into

‘Modern Contractual Relations, New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press, 1980; Palay,

Thomas, “Comparative | Institutional

Economics: The Governance of Rail Freight

Contracting,” Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 13

(1984), pp. 6-17; Williamson, Oliver E.,

‘Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Anti-

trust Implications, New York: Free Press, 1975.

(15] Cavinato, Joseph L., (1991), op. cit;

Houlihan, John B., (1985), op. cit.

[16] Gardner, john T. and Martha C.

Cooper, (1988), op. cit.; Macneil, lan R.,

1980, op. cit.; Palay, Thomas, (1984) op. cit,

117] Ellram, Lisa M.and Martha C.

Cooper (1990), op. cit.; Houlihan, (1988),

op. cit

[18] Cavinato, Joseph L., (1991), op.ct.

119] Cavinato, Joseph L., (1991), op.cit

[20] Macneil, lan R., 1980, op.cit;

Williamson, Oliver €., The Economic

Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets,

Relational Contracting, New York, New

York: The Free Press, 1985.

[21] Ellram, Lisa M. and Martha C.

Cooper (1990), op. cit.

[22] Gardner, John T. and Martha C.

Cooper, (1988), op. cit.

[23] Cooper, Martha C., Daniel

Innis, and Peter R. Dickson, Strategic

Planning for Logistics, Oak Brook, I: the

Council of Logistics Management, 1991

Poge 23

[24] Hewit, Frederick (1992), op.cit.

[25] Cooper, Martha C., Daniel E. Innis,

and Peter R. Dickson, 1992, op. cit.

126] Ellram, Lisa M. and Martha C

Cooper (1990), op. cit.; Gardner, John T. and

Martha C, Cooper, (1988), op. cil.

(271 Kanter, Rosabeth Moss,

“Transcending Business Boundaries: 12,000

World Managers View Change,” Harvard

Business Review, Vol. 69, No. 3 (May-lune,

1991), pp. 151-154

[28] “Building Successful Global

Partnerships,” The Journal of Business Strategy,

Vol. 9, No. 5 (1988), pp. 12-15; Main, Jeremy,

“Making Global Alliances Work,” Fortune,

(December 17, 1990), pp. 121-126.

[29] Gattorna, John L., Norman H.

Chorn, and Abby Day, “Pathways to

Customers: Reducing Complexity in the

Logistics Pipeline,” International Journal of

Physical Distribution and Materials

‘Management, Vol. 21, No. 8 (1991), pp.5

11; Hewitt, Frederick, (1992), op. cit.; Main,

Jeremy, (1990), op. cit.

(30) Ellram, Lisa M. and Martha C

Cooper (1990), op. cit; La Londe, Bernard J.

and Martha C. Cooper, Partnerships in

Providing Customer Service: A Third Party

Perspective, Oak Brook: Council of Logistics

Management, 1989.

[31] Ellram, Lisa M. and Martha C.

Cooper (1990), op. cit

[32] McCarthy, E Jerome and William

D. Perreault, Jr, Basic Marketing,

Homewood, IL: tnwin, 1990, Chapter 11

[33] Williamson, Oliver E., 1975, op.

cit; Palay, Thomas (1984) op. cit.

[34] La Londe, Bernard J. Martha C.

Cooper, and Thomas G. Noordewier,

Customer Service: A Management

Perspective, Oak Brook: Council of Logistics

Management, 1988,

[35] Ellram, Lisa M. and Martha C.

Cooper (1990), op. cit.

[36] Gardner, John T. and Martha C.

Cooper, (1988), op. cit.; Kanter, Rosabeth

Moss (1991), op. cit.

[37] Cavinato, Joseph L., (1991), op. cit.

[38] Hewitt, Frederick, (1992), op. cit.

(39) Ellram, Lisa M. and Martha C.

Cooper (1990), op. cit.

{40} Hewitt, Frederick, (1992), op. cit.

141} Cooper, Martha C., Daniel €.

Innis, and Peter R. Dickson, 1992, op. cit

[42] Cooper, Martha C., Daniel E.

Innis, and Peter R. Dickson, 1992, op. cit

{43} Gardner, john T. and Martha C.

‘Cooper, (1988), op. cit.

[44] Cooper, Martha C., Daniel E

Innis, and Peter R. Dickson, 1992, op. cit.

Martha C, Cooper is Associate Professor of Marketing and Logistics at the Ohio

State University. She received a B.S. in Math/Computer Science and a Masters in

Industrial Administration from Purdue University. Her doctorate is from Ohio State.

Professor Cooper's research interests include the role of customer service in

corporate strategy, supply chain management and partnership dimensions, and the

role of information technology in logistics practice and education. She has co-

authored three books on customer service, partnerships, and strategic planning.

‘She has published In several journals, including The international Journal of

Logistics Management, The International Journal of Physical Distribution and

Materials Management, The Journal of Business Logistics, The Logistics and

Transportation Review, and The Transportation Journal. Phone: 614-292-5761.

Lisa M. Ellram is Assistant Professor of Purchasing & Logistics Management at

Arizona State University. Dr. Ellram received her B.S.B. and M.B.A. from the

University of Minnesota, and her Ph.D. from the Ohio State University. She is a

Certified Purchasing Manager, Certified Public Accountant, and Certified

Management Accountant. Her current research interests include total cost of

ownership, international and domestic supply chain management, buyer-seller

relationships, and purchasing strategy. Dr. Ellram's publications have appeared in

The Intemational Journal of Physical Distribution and Materials Management, The

International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management, The international

Journal of Logistics Management, and The Journal of Business Logistics and

Management Decision. Phone: 602-965-6044,

Page 24 The International Journal of Logistics Management

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Colorscope 1Document6 pagesColorscope 1Oca Chan100% (2)

- Practica Alesca S.ADocument13 pagesPractica Alesca S.AAlondra TorresNo ratings yet

- A4 OdcgDocument8 pagesA4 OdcgOscarCg CRNo ratings yet

- Caso 1 Nutrilak - Identificacion de Problemas y Funciones GerencialesDocument3 pagesCaso 1 Nutrilak - Identificacion de Problemas y Funciones GerencialesDiana Milagros Rafael Acuña100% (2)

- The Concept of Sustainable Development in Pakistan: Full Length Research PaperDocument10 pagesThe Concept of Sustainable Development in Pakistan: Full Length Research PaperMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Implications For Sustainability: Dear Mr. President and Members of CongressDocument2 pagesImplications For Sustainability: Dear Mr. President and Members of CongressMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management 2005 10, 2 ABI/INFORM GlobalDocument12 pagesSupply Chain Management 2005 10, 2 ABI/INFORM GlobalMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Inter-Organizational Decision Coordination: Case StudyDocument12 pagesUnderstanding Inter-Organizational Decision Coordination: Case StudyMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Financial 2015Document64 pagesFinancial 2015Aftab SaadNo ratings yet

- Emergence of Modern RetailingDocument16 pagesEmergence of Modern RetailingMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- Respected Sir/Madam Institute of Management Sciences, BZU, Multan Subject: Request For The Permission of Medical LeaveDocument1 pageRespected Sir/Madam Institute of Management Sciences, BZU, Multan Subject: Request For The Permission of Medical LeaveMuhammad Umar RazaNo ratings yet

- La Théorie de ConsommateurDocument83 pagesLa Théorie de Consommateurabdelrh100% (1)

- 建築圖ALLDocument110 pages建築圖ALL陳俊佐No ratings yet

- CEMEX IntroduccionDocument2 pagesCEMEX Introduccionrokat atNo ratings yet

- Factura SimpleTVDocument2 pagesFactura SimpleTVAlejandro RiveraNo ratings yet

- Sintesis de Los Principios de Contabilidad Generalmente AceptadosDocument7 pagesSintesis de Los Principios de Contabilidad Generalmente AceptadosCarlos HernándezNo ratings yet

- EXAMEN FINAL DE ADMINISTRACIÓN DE MAQUINARIA AGRÍCOLA Julio 2016Document1 pageEXAMEN FINAL DE ADMINISTRACIÓN DE MAQUINARIA AGRÍCOLA Julio 2016Ricardo AndréNo ratings yet

- 02 ESTUDIO-HIDROLOGICO - RumichacaDocument33 pages02 ESTUDIO-HIDROLOGICO - RumichacaJose Norabuena VillarealNo ratings yet

- Desarollo Con Jumbo ElectrohidraulicoDocument11 pagesDesarollo Con Jumbo Electrohidraulicodmamani31No ratings yet

- Guía 2020. GyCDocument70 pagesGuía 2020. GyCDanis GoubaidoulineNo ratings yet

- Procedimiento Manejo de Desechos Peligrosos y No PeligrososDocument6 pagesProcedimiento Manejo de Desechos Peligrosos y No PeligrososInspección refamecaNo ratings yet

- ABSTRACT 16-17 (English)Document707 pagesABSTRACT 16-17 (English)DeepakNo ratings yet

- Cavinkare: Company Website AboutDocument3 pagesCavinkare: Company Website AboutKpvs NikhilNo ratings yet

- 113-S03 Mueller Lehmkuhl GMBH - Anexos en Excel AADocument8 pages113-S03 Mueller Lehmkuhl GMBH - Anexos en Excel AApaocvl892No ratings yet

- Cebu Winland Vs Ong Sia HuaDocument1 pageCebu Winland Vs Ong Sia HuahappypammynessNo ratings yet

- Unidad 2 Contabilidad GeneralDocument18 pagesUnidad 2 Contabilidad GeneralTamaraNo ratings yet

- Síntesis EEADocument7 pagesSíntesis EEAmlorentejimenezNo ratings yet

- Far - Chapter 7Document25 pagesFar - Chapter 7Danica TorresNo ratings yet

- Exp 41575 Servicio de Reubicacion de Estructuras Postes y Redes en El Sistema SecundarioDocument17 pagesExp 41575 Servicio de Reubicacion de Estructuras Postes y Redes en El Sistema SecundarioVANESSAMAMANI QUENTANo ratings yet

- Hernandez Karla U1G4T5Document6 pagesHernandez Karla U1G4T5Melissa VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- MM - TJ - Matematica Financeira - Conferido 7h (1) - Gabaritada 5Document12 pagesMM - TJ - Matematica Financeira - Conferido 7h (1) - Gabaritada 5RicardoAmaralNo ratings yet

- Expediente Tecnico PNX-02Document31 pagesExpediente Tecnico PNX-02Emicko EmiNo ratings yet

- Ejercicios de KardexDocument38 pagesEjercicios de KardexCamila RodriguezNo ratings yet

- OFERTA SAN NICOLAS Rev 04 AventoDocument5 pagesOFERTA SAN NICOLAS Rev 04 AventoNataLiia MonTezNo ratings yet

- Evaluación de Proyectos de Inversión PublicaDocument49 pagesEvaluación de Proyectos de Inversión PublicaEiner Nicolas Berduzco100% (1)

- Laboratorio Muro de Ladrillo SimpleDocument7 pagesLaboratorio Muro de Ladrillo SimpleDeynor MamaniNo ratings yet

- Ejercicio Tabla DinamicaDocument19 pagesEjercicio Tabla DinamicaSonlange Shantall CallerNo ratings yet