Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Public - Monument - Citas

Public - Monument - Citas

Uploaded by

magnolia pérez bejaranoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Public - Monument - Citas

Public - Monument - Citas

Uploaded by

magnolia pérez bejaranoCopyright:

Available Formats

Miles, Malcolm. Art, space and the city: Public art and urban futures. Ed: Routledge. London.

1997

The monument

Negando otras posibilidades del pasado. Los discursos hegemonicos

“the argument has a general application; whilst the monument as a device of hegemony establishes a

national history, so it may also bury a national memory (...)The history represented by statues is a

closure inhibiting the imagining of alternative futures by denying the possibility of alternative pasts;

but if this monument is an opening in society’s received structure of values, dislocating the assumptions

of an ‘official’ history, it is an act of resistance (…) what seems more to the point is whether it, or

public art in general, affirms or interrogates the structures of power in society ” (p. 50)

“THE MONUMENT AND NATIONAL IDENTITY Monuments stand in a complex relation to time:

they state a past or its imitation, but are erected to impress contemporary publics with the relation to

history of those who hold power and the durability of that relation expressed in stone or bronze. One

past out of many possible constructions is represented as the past, just as one concept of the city is

represented as a dominant concept in its planning” (p. 37)

antimonuments and graffiti

“Many kinds of graffiti were added to the column, exposing prejudices against ‘guest-workers’

reminiscent of anti-semitism, the controversy around the monument accepted by the artists as part of its

impact. The column has been described as an antimonument, which refuses the forgetfulness of

conventional monuments which do society’s remembering for it ”

habitantes construyen los paisajes urbanos

“h ‘a willingness to listen and learn from members of the public of all ages, ethnic backgrounds, and

economic circumstances’ (Hayden, 1995:235). (…) primary importance to the political and social

narratives of the neighbourhood, and to the everyday lives of working people. It assumes that every

inhabitant is an active participant in the making of the city, not just one hero-designer” (p. 118)

“the spontaneous visual interventions of urban dwellers through graffiti and ‘unofficial’ street murals.

Some kinds of art, such as the altering of advertising posters to invert their messages, is between the

two (…) cultural diversity and environmental awareness are cases of art as intervention ” (p. 123)

El arte que no pertenece al mainstream

“The ‘art of public engagement’ is misunderstood and often maligned by the mainstream and critical

contemporary art fields. It is vital to reassert the presence of community-based art…. The field must

expand its definition of art by broadening the knowledge of what art means within other societies

(Jacob, 1996) ” (p. 124)

THE CONTRADICTIONS OF PUBLIC ART arte público entre momumento y activismo

“The map of public art is difficult to delineate, and contested, but its polarities could be stated as, on

one hand, a contemporary equivalent of the nineteenth-century monument, a practice which

accepts social and artistic conventions, its contradictions concealed by relocation to an art space

outside the gallery or museum and by the lack of documentation of its reception; and an emerging

practice of art as activism and engagement” (p. 52)

“ (...) public art often fails to create a public (…) public art inevitably operates in the public realm and a

lack of critical engagement with the construction of that realm leads by default to n. Descriptions of

public art are generally not kind and reflect its marginality. It has been called ‘a special kind of

socioaesthetic pudding’ (Willett, 1984:11), and ‘an oxymoron…resolved in favour of banality’

(Brighton, 1993b:43), which indicates that there is a problem in using the term ‘public art’, and perhaps

it is no longer possible to do so for anything other than a co-option of art to public policy through

public funding. But, another writer states that artists ‘working in the public interest address a wide

range of human concerns’ ” (p. 52)

“a sculpture in a plaza is not made accessible by its site as such, and any work of art in a public

collection might be described as ‘public’,5 so that the issue becomes not ‘public art’ but ‘the reception

of art by publics’. That reception can be manipulated. ” (p. 53)

lo publico

“One basic assumption that has underwritten many of the contemporary manifestations of public art is

the notion that this art derives its ‘publicness’ from where it is located… The idea of the public is a

difficult, mutable, and perhaps somewhat atrophied one, but the fact remains that the public dimension

is a psychological…construct. (Phillips, 1988:93) ” (p. 60)

estructuras de poder

“‘conventional’ public art became increasingly characterised as collaboration with dominant state and

corporate, national and global structures of power ” (p. 61)

“The acceptance of difference (of gender, race, class, sexual orientation and age) contributes to the end

of social fragmentation; but it is a process of resistance as well as celebration, and it too requires

bridges from social theory to art practice. Jacob writes: ‘Difference is a key concept in the breakdown

of the mainstream power structure’ ” (p. 107)

You might also like

- Lee, Pamela M. - Forgetting The Art World (Introduction)Document45 pagesLee, Pamela M. - Forgetting The Art World (Introduction)Ivan Flores Arancibia100% (1)

- Community and Communication in Modern Art PDFDocument4 pagesCommunity and Communication in Modern Art PDFAlumno Xochimilco GUADALUPE CECILIA MERCADO VALADEZNo ratings yet

- Lawrence Alloway, The Arts and The Mass Media'Document3 pagesLawrence Alloway, The Arts and The Mass Media'myersal100% (2)

- The Value and Understanding of The Historical, Social, Economic, and Political Implications of ArtDocument6 pagesThe Value and Understanding of The Historical, Social, Economic, and Political Implications of ArtKraix Rithe RigunanNo ratings yet

- Hein, Hilde, What Is Public Art?: Time, Place, and MeaningDocument8 pagesHein, Hilde, What Is Public Art?: Time, Place, and MeaningAnonymous 07iOgJ52ozNo ratings yet

- Participation and Spectacle Where Are We Now - BishopDocument4 pagesParticipation and Spectacle Where Are We Now - Bishopfai_iriNo ratings yet

- Krzystof Wodiczko - Strategies of Public AddressDocument4 pagesKrzystof Wodiczko - Strategies of Public AddressEgor SofronovNo ratings yet

- 6int 2005 Jun QDocument9 pages6int 2005 Jun Qapi-19836745No ratings yet

- قواعد الانجليزية كاملة اهداء صفحة المدرس بوكDocument40 pagesقواعد الانجليزية كاملة اهداء صفحة المدرس بوكboudekhanaNo ratings yet

- Uncommon Threads The Role of Oral and Archival Testimony in The Shaping of Urban Public Art. Ruth Wallach, University of Southern CaliforniaDocument5 pagesUncommon Threads The Role of Oral and Archival Testimony in The Shaping of Urban Public Art. Ruth Wallach, University of Southern CaliforniaconsulusNo ratings yet

- (IID2013) Midterm Papers by Pho Vu (Hemin)Document6 pages(IID2013) Midterm Papers by Pho Vu (Hemin)Pho VuNo ratings yet

- Wallenberg1997 MichaelsorkinDocument52 pagesWallenberg1997 MichaelsorkinMiriam FitzpatrickNo ratings yet

- Street Art: A Semiotic RevolutionDocument8 pagesStreet Art: A Semiotic Revolutionanaktazija100% (1)

- Situationist Urbanism: Situationist International Movement, Concept of Spectacle and The CityDocument5 pagesSituationist Urbanism: Situationist International Movement, Concept of Spectacle and The CityHarsha VardhiniNo ratings yet

- Grafittijpcu 12843Document22 pagesGrafittijpcu 12843Rafaela MorelliNo ratings yet

- Themes of Postmodern Urbanism Part ADocument11 pagesThemes of Postmodern Urbanism Part ADaryl MataNo ratings yet

- Social Infusion: Crisis CityDocument5 pagesSocial Infusion: Crisis Citydlwilson1757No ratings yet

- Art Politcs and The Public Square DChild APSDocument20 pagesArt Politcs and The Public Square DChild APSสามชาย ศรีสันต์No ratings yet

- Participation and Spectacle: Where Are We Now?Document11 pagesParticipation and Spectacle: Where Are We Now?Cássia PérezNo ratings yet

- Relational AestheticsDocument11 pagesRelational AestheticsDominic Da Souza CorreaNo ratings yet

- 09 GarciaCanclini MulticulturalismDocument5 pages09 GarciaCanclini MulticulturalismStergios SourlopoulosNo ratings yet

- Monumentos Revista OctoberDocument175 pagesMonumentos Revista OctoberHenrique XavierNo ratings yet

- Globalizare Și IdentitateDocument12 pagesGlobalizare Și IdentitateMarina RusuNo ratings yet

- Symbolic Deterritorialization: The Case of Francis AlÿsDocument5 pagesSymbolic Deterritorialization: The Case of Francis Alÿscem demirciNo ratings yet

- Frampton - Towards A Critical RegionalismDocument22 pagesFrampton - Towards A Critical Regionalismfatima medinaNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Community Art and ActivismDocument9 pagesAn Introduction To Community Art and ActivismAntonio ColladosNo ratings yet

- Monica Juneja - Global Art History and The Burden of RepresentationDocument24 pagesMonica Juneja - Global Art History and The Burden of RepresentationEva MichielsNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Art and The Not-Now: Branislav DimitrijevićDocument8 pagesContemporary Art and The Not-Now: Branislav DimitrijevićAleksandar BoškovićNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Art At The End Of The Century, Approaches To A Postmodern Aesthetics" By María Rosa Rossi: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Art At The End Of The Century, Approaches To A Postmodern Aesthetics" By María Rosa Rossi: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Alien-Own/Own-Alien: Globalization and Cultural Difference: Gerardo MosqueraDocument11 pagesAlien-Own/Own-Alien: Globalization and Cultural Difference: Gerardo MosqueraCecilia LeeNo ratings yet

- A Thousand Kitchen TablesDocument4 pagesA Thousand Kitchen TableskollectivNo ratings yet

- Museums As Authorative Institutions: Politics of Collection and DisplayDocument15 pagesMuseums As Authorative Institutions: Politics of Collection and DisplaymajorbonoboNo ratings yet

- 2 Chapter On Art by Pablo MarkinDocument34 pages2 Chapter On Art by Pablo MarkinSonia Emilia MihaiNo ratings yet

- CproLfGoS9Summer School DraggedDocument2 pagesCproLfGoS9Summer School DraggedSanjaNo ratings yet

- The Violence of Public Art - Do The Right Thing - MitchellDocument21 pagesThe Violence of Public Art - Do The Right Thing - MitchellDaniel Rockn-RollaNo ratings yet

- Temporality and Permanence in Romanian Public Art: DOI: 10.15503/jecs20151.207.216Document10 pagesTemporality and Permanence in Romanian Public Art: DOI: 10.15503/jecs20151.207.216Quyền Lương CaoNo ratings yet

- Art-as-Ideology at The New Museum ModDocument3 pagesArt-as-Ideology at The New Museum ModLokir CientoUnoNo ratings yet

- Keywords Echoes Marine Schütz Decolonial Aesthetics 2018Document13 pagesKeywords Echoes Marine Schütz Decolonial Aesthetics 2018Jorge de La BarreNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Art Between Action and Work PDFDocument18 pagesContemporary Art Between Action and Work PDFMelissa Moreira TYNo ratings yet

- Afterward, Librito, 3Document5 pagesAfterward, Librito, 3silverdy79No ratings yet

- CityScope The Cinema and The CityDocument12 pagesCityScope The Cinema and The CityAmal HashimNo ratings yet

- Mapping The TerrainDocument7 pagesMapping The TerrainJody TurnerNo ratings yet

- 13.14 PP 391 393 The False Distinctions of Socially Engaged Art and ArtDocument3 pages13.14 PP 391 393 The False Distinctions of Socially Engaged Art and ArtPablo VelázquezNo ratings yet

- VMC Research DraftDocument7 pagesVMC Research Draftshadaer.3258No ratings yet

- City Guide: Urban Space After The Situationist InternationalDocument49 pagesCity Guide: Urban Space After The Situationist Internationaljeni_sarah3No ratings yet

- Mary Coffey, Introduction: How A Revolutionary Art Became Official CultureDocument24 pagesMary Coffey, Introduction: How A Revolutionary Art Became Official Culturemichael ballNo ratings yet

- REvista Hans Haacke InterviewDocument3 pagesREvista Hans Haacke InterviewTamar ShafrirNo ratings yet

- 1984b Jameson's PostmodernismDocument4 pages1984b Jameson's PostmodernismJorge SayãoNo ratings yet

- Altermodernity: A Postcolonial(s) ConstellationDocument10 pagesAltermodernity: A Postcolonial(s) ConstellationShirl B Innes50% (2)

- Frampton - 1983 - Towards A Critical RegionalismDocument15 pagesFrampton - 1983 - Towards A Critical RegionalismMatthew DalzielNo ratings yet

- Didaskalia AngielskiDocument63 pagesDidaskalia AngielskiDorota Jagoda MichalskaNo ratings yet

- Malcolm Miles Reclaiming The Public SphereDocument7 pagesMalcolm Miles Reclaiming The Public SphereAdina BogateanNo ratings yet

- The Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence AllowayDocument1 pageThe Arts and The Mass Media by Lawrence Allowaymacarena vNo ratings yet

- Modernismus Last Post: Stephen SlemonDocument15 pagesModernismus Last Post: Stephen SlemonCamila BatistaNo ratings yet

- Allais 2018Document175 pagesAllais 2018Laura KrebsNo ratings yet

- 010 Libeskind - and - The - Holocaust - Metanarrative - From - DisDocument13 pages010 Libeskind - and - The - Holocaust - Metanarrative - From - DisKurdistan SalamNo ratings yet

- Judith Adler - Revolutionary ArtDocument19 pagesJudith Adler - Revolutionary ArtJosé Miguel CuretNo ratings yet

- Very Important IntroductionDocument6 pagesVery Important IntroductionGrațiela GraceNo ratings yet

- Drucker - Who's Afraid of Visual CultureDocument13 pagesDrucker - Who's Afraid of Visual CultureMitch TorbertNo ratings yet

- Travels in Intermediality: ReBlurring the BoundariesFrom EverandTravels in Intermediality: ReBlurring the BoundariesRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Trinity Gese Grade 7 Conversation Questions Conversation Topics Dialogs Oneonone Activities - 70388Document2 pagesTrinity Gese Grade 7 Conversation Questions Conversation Topics Dialogs Oneonone Activities - 70388Anabel Moreno100% (2)

- Purposive Communication LectureDocument70 pagesPurposive Communication LectureJericho DadoNo ratings yet

- Staffing & RecruitmentDocument80 pagesStaffing & Recruitmentsuganthi rajesh kannaNo ratings yet

- Tata Acquired Luxury Auto Brands Jaguar and Land Rover - From Ford MotorsDocument15 pagesTata Acquired Luxury Auto Brands Jaguar and Land Rover - From Ford MotorsJoel SaldanhaNo ratings yet

- Check My TripDocument3 pagesCheck My TripBabar WaheedNo ratings yet

- March 2014 TstiDocument12 pagesMarch 2014 TstiDan CohenNo ratings yet

- Case Study (The Flaundering Expatriate)Document9 pagesCase Study (The Flaundering Expatriate)Pratima SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Law of Succession CATDocument11 pagesLaw of Succession CATSancho SanchezNo ratings yet

- Case Comment On Uttam V Saubhag SinghDocument8 pagesCase Comment On Uttam V Saubhag SinghARJU JAMBHULKARNo ratings yet

- Buddy HollyDocument3 pagesBuddy Hollyapi-276376703No ratings yet

- Kakori ConspiracyDocument8 pagesKakori ConspiracyAvaneeshNo ratings yet

- KaramuntingDocument14 pagesKaramuntingHaresti MariantoNo ratings yet

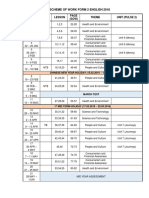

- Scheme of Work Form 2 English 2018: Week Types Lesson (SOW) Theme Unit (Pulse 2)Document2 pagesScheme of Work Form 2 English 2018: Week Types Lesson (SOW) Theme Unit (Pulse 2)Subramaniam Periannan100% (2)

- AC Checklist of ToolsDocument4 pagesAC Checklist of ToolsTvet AcnNo ratings yet

- LLB102 2023 2 DeferredDocument8 pagesLLB102 2023 2 Deferredlo seNo ratings yet

- Parental Involvement and Their Impact On Reading English of Students Among The Rural School in MalaysiaDocument8 pagesParental Involvement and Their Impact On Reading English of Students Among The Rural School in MalaysiaM-Hazmir HamzahNo ratings yet

- RA No. 9514 - Revised Fire Code of The Philippines (2008)Document586 pagesRA No. 9514 - Revised Fire Code of The Philippines (2008)Xyzer Corpuz Lalunio88% (33)

- Accounting 1 Module 3Document20 pagesAccounting 1 Module 3Rose Marie Recorte100% (1)

- Landscape of The SoulDocument2 pagesLandscape of The Soulratnapathak100% (1)

- Definition:: Handover NotesDocument3 pagesDefinition:: Handover NotesRalkan KantonNo ratings yet

- Attendance DenmarkDocument3 pagesAttendance Denmarkdennis berja laguraNo ratings yet

- Stone Houses of Jefferson CountyDocument240 pagesStone Houses of Jefferson CountyAs PireNo ratings yet

- A Reply To Prof Mark Tatz - Brian GallowayDocument5 pagesA Reply To Prof Mark Tatz - Brian GallowayAjit GargeshwariNo ratings yet

- Industrial Security ConceptDocument85 pagesIndustrial Security ConceptJonathanKelly Bitonga BargasoNo ratings yet

- Site Visit Report - 6 TH SEM - DssDocument9 pagesSite Visit Report - 6 TH SEM - DssJuhi PatelNo ratings yet

- Manual For Conflict AnalysisDocument38 pagesManual For Conflict AnalysisNadine KadriNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management NotesDocument35 pagesSupply Chain Management NotesRazin GajiwalaNo ratings yet

- Komunikasi SBAR Perawat Dan Dokter Dalam Kolaborasi Interprofesional Di Rumah Sakit X 2023Document13 pagesKomunikasi SBAR Perawat Dan Dokter Dalam Kolaborasi Interprofesional Di Rumah Sakit X 2023Laras Adythia PratiwiNo ratings yet