Professional Documents

Culture Documents

DROGADICCIÓN

DROGADICCIÓN

Uploaded by

lbritez7Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

DROGADICCIÓN

DROGADICCIÓN

Uploaded by

lbritez7Copyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Guideline Annals of Internal Medicine

Primary Care Behavioral Interventions to Reduce Illicit Drug and

Nonmedical Pharmaceutical Use in Children and Adolescents:

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement

Virginia A. Moyer, MD, MPH, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force*

Description: Update of the 2008 U.S. Preventive Services Task Recommendation: The USPSTF concludes that the current evi-

Force (USPSTF) recommendation on screening for illicit drug use. dence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of

primary care– based behavioral interventions to prevent or reduce

Methods: The USPSTF reviewed the evidence on interventions to illicit drug or nonmedical pharmaceutical use in children and ado-

help adolescents who have never used drugs to remain abstinent lescents. (I statement)

and interventions to help adolescents who are using drugs but do

not meet criteria for a substance use disorder to reduce or stop

their use. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:634-639. www.annals.org

For author affiliation, see end of text.

Population: This recommendation applies to children and adoles- * For a list of USPSTF members, see the Appendix (available at

cents younger than age 18 years who have not been diagnosed www.annals.org).

with a substance use disorder. This article was published online first at www.annals.org on 11 March 2014.

T he U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) makes

recommendations about the effectiveness of specific preven-

tive care services for patients without related signs or

children and adolescents. This recommendation applies to

children and adolescents who have not already been diag-

nosed with a substance use disorder. (I statement)

symptoms. See the Clinical Considerations section for suggestions

It bases its recommendations on the evidence of both the for practice regarding the I statement and definitions of

benefits and harms of the service and an assessment of the terms that are used.

balance. The USPSTF does not consider the costs of providing See the Figure for a summary of the recommendation

a service in this assessment. and suggestions for clinical practice.

The USPSTF recognizes that clinical decisions involve Appendix Table 1 describes the USPSTF grades, and

more considerations than evidence alone. Clinicians should Appendix Table 2 describes the USPSTF classification of

understand the evidence but individualize decision making to levels of certainty regarding net benefit (both tables are

the specific patient or situation. Similarly, the USPSTF notes available at www.annals.org).

that policy and coverage decisions involve considerations in

addition to the evidence of clinical benefits and harms.

RATIONALE

Importance

SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATION AND EVIDENCE According to the National Survey on Drug Use and

The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is Health (NSDUH), more than 4300 adolescents aged 12 to

insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of 17 years use drugs for the first time each day in the United

primary care– based behavioral interventions to prevent or States (1). (Note: The NSDUH collected data on use of

reduce illicit drug or nonmedical pharmaceutical use in illicit drugs and nonmedical use of prescription drugs but

not over-the-counter drugs; thus, actual drug use [illicit

and nonmedical use of all pharmaceuticals] rates may be

See also: greater.) Approximately 9.5% of youths aged 12 to 17

years report drug use in the past month (1). In addition, in

Related article. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 612

2012, 4.4% of eighth-, tenth-, and twelfth-grade students

Summary for Patients. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . I-24

reported using over-the-counter cough or cold medicine in

Web-Only the past year for nonmedical reasons (2). Drug use is asso-

CME quiz ciated with many negative health, social, and economic

Consumer Fact Sheet consequences and is a significant contributor to 3 of the

leading causes of death among adolescents—motor vehicle

Annals of Internal Medicine

634 6 May 2014 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 160 • Number 9 www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 10/31/2016

Interventions to Reduce Drug Use in Children and Adolescents Clinical Guideline

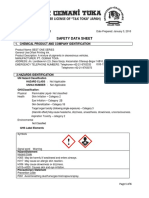

Figure. Primary care behavioral interventions to reduce illicit drug and nonmedical pharmaceutical use in children and adolescents:

clinical summary of U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation.

PRIMARY CARE BEHAVIORAL INTERVENTIONS TO REDUCE ILLICIT DRUG AND

NONMEDICAL PHARMACEUTICAL USE IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

CLINICAL SUMMARY OF U.S. PREVENTIVE SERVICES TASK FORCE RECOMMENDATION

Population Children and adolescents younger than age 18 y who have not already been diagnosed with a substance use disorder

No recommendation.

Recommendation

Grade: I statement

Although the evidence is insufficient to recommend specific interventions in the primary care setting, face-to-face

Behavioral Interventions counseling, videos, print materials, and interactive computer-based tools have been studied. Studies on these interventions

were limited, and findings on whether interventions significantly improved health outcomes were inconsistent.

Balance of Benefits and The evidence about primary care–based behavioral interventions to prevent or reduce illicit drug and nonmedical

Harms pharmaceutical use in children and adolescents is insufficient, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined.

Other Relevant USPSTF The USPSTF has made recommendations on screening for and interventions to decrease the unhealthy use of other

Recommendations substances, including alcohol and tobacco. These recommendations are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

For a summary of the evidence systematically reviewed in making this recommendation, the full recommendation statement, and supporting documents, please

go to www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

accidents, homicide, and suicide. Consequences not only children and adolescents is insufficient, and the balance of

arise from frequent and heavy drug use, but use increases benefits and harms cannot be determined.

risk-taking behaviors while intoxicated, such as driving un-

der the influence, unsafe sexual activity, and violence. In

CLINICAL CONSIDERATIONS

2011, more than 150 000 adolescents were treated in

Patient Population Under Consideration

emergency departments for complications of illicit drug

and nonmedical pharmaceutical use (3). This recommendation applies to children and adoles-

cents younger than age 18 years. It does not apply to chil-

Benefits of Behavioral Interventions dren and adolescents who have been diagnosed with a sub-

The USPSTF found inadequate evidence about the stance use disorder. All persons with a substance use

effect of behavioral interventions to reduce drug use on disorder should receive appropriate treatment. Although

health outcomes in adolescents. It also found inadequate this statement does not include a recommendation on

evidence about the effect of behavioral interventions to screening for drug use, further information on screening

reduce initiation of drug use in adolescents. The Task tests is provided in the Discussion section.

Force found no evidence about behavioral interventions for

children younger than age 11 years. Definitions

The USPSTF recognizes that various definitions have

Harms of Behavioral Interventions been applied to the terms drug use, misuse, and abuse. For

The USPSTF found no studies about the magnitude the purpose of this recommendation statement, “drug use”

of the harms of behavioral interventions to prevent or re- encompasses the general concepts of “illicit drug use” and

duce drug use. Although the USPSTF recognizes that the- “nonmedical use of pharmaceuticals” (prescription and

oretical harms, such as the potential to increase drug initi- over-the-counter drugs). “Illicit drug use” specifies use of

ation through a false sense of security, may exist, it illegal drugs (such as cocaine and heroin) and inhalants

concludes that the harms of behavioral interventions are (such as aerosols, glue, and gasoline). “Nonmedical use of

probably small to none. pharmaceuticals” includes the use of prescribed medica-

USPSTF Assessment tions for a purpose other than prescribed (or by a person

The USPSTF concludes that the evidence about pri- not prescribed the medication) or the use of over-the-

mary care– based behavioral interventions to prevent or re- counter drugs for a purpose other than medically indicated.

duce illicit drug and nonmedical pharmaceutical use in To be consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

www.annals.org 6 May 2014 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 160 • Number 9 635

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 10/31/2016

Clinical Guideline Interventions to Reduce Drug Use in Children and Adolescents

of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, “substance use disorder” behaviors, and even paradoxical increases in drug use or

is used instead of “substance abuse” and “substance depen- initiation. Although evidence is limited, no direct harms

dence” unless describing previously collected study or sur- were identified.

vey results that reported findings using the terms abuse and

dependence. Current Practice

Behavioral Interventions Most clinicians who care for children and adolescents

Although the evidence to recommend specific inter- in the United States do not provide behavioral interven-

ventions in the primary care setting is insufficient, inter- tions to reduce drug use. Given the lack of evidence of

ventions that have been studied include face-to-face effective primary care– based interventions, this is not sur-

counseling, videos, print materials, and interactive prising. It is important to recognize that this recommen-

computer-based tools. Studies on these interventions pro- dation does not address screening for drug use. Screening

vide little to no evidence of significant improvements in adolescents who are not suspected to be using drugs may

health outcomes. identify some who meet criteria for a substance use disor-

Suggestions for Practice Regarding the I Statement der and for whom treatment is available. The Task Force

In deciding whether to provide behavioral interven- did not find effective interventions to reduce future drug

tions to prevent or reduce illicit drug and nonmedical use in adolescents who have tried illicit drugs.

pharmaceutical use for children and adolescents, primary Useful Resources

care providers should consider the following factors. The USPSTF has made recommendations on screen-

ing for and interventions to decrease the unhealthy use of

Potential Preventable Burden

other substances, including alcohol and tobacco. These

According to the NSDUH, nearly 1 in 10 U.S. ado- recommendations are available on the USPSTF Web site

lescents use drugs (1). In 2011, the Drug Abuse Warning (www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org).

Network estimated that more than 75 000 emergency de-

partment visits by children and adolescents involved illicit OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

drugs, and more than 75 000 visits involved the nonmed- Research Needs and Gaps

ical use of pharmaceuticals (3). The consequences of drug Illicit drug and nonmedical pharmaceutical use in ad-

use include risk for progression to a substance use disorder, olescents is an important public health problem. Evidence

an increase in risk-taking behaviors while under the influ- to assess the effects of behavioral interventions in adoles-

ence, and lower educational achievement and attainment. cents is limited, and high-quality studies that focus on the

Persons who initiate marijuana use at younger ages are role of primary care professionals in preventing initiation

more likely to progress to drug abuse and dependence as of drug use and reducing use among those who have ex-

adults compared with those who initiate use after age 18 perimented are needed. Research on brief interventions;

years (1). interventions that link screening with tailored interven-

tions; and social media, cell phone, and Internet-based in-

Costs terventions is needed and may identify novel, effective risk-

The costs associated with primary care– based behav- reduction strategies. Research should continue to study

ioral interventions vary substantially and are similar to diverse populations and the effects of interventions on chil-

costs of interventions for tobacco and alcohol reduction. dren and adolescents with different risks, as well as which

Health systems and providers should account for the staff interventions work best in these subpopulations. Research

time associated with any intervention, which may range should continue to examine the effectiveness of behavioral

from distributing educational materials to a series of office- interventions with and without parental involvement. Ad-

based, 1-on-1 counseling sessions. Computer-based inter- ditional high-quality studies that evaluate interventions

active tools linked to an adolescent’s personal health record and address drug use in the context of other substances,

may require less ongoing staff time to administer. There including tobacco and alcohol, are also needed. Research to

are also potential costs for families, especially for interven- develop and validate tools to measure current and past

tions that require significant participation from parents as substance use is needed. Attention should be given to the

well as adolescents. standardization of research outcomes to improve the ability

of future systematic reviews to move the field forward.

Potential Harms

Potential harms associated with behavioral interven- DISCUSSION

tions include anxiety, interference with the clinician– Burden of Disease

patient relationship, opportunity costs (that is, time spent According to the NSDUH, more than 4300 adoles-

on these interventions that could be used for other, more cents aged 12 to 17 years use drugs for the first time each

effective interventions), unintended increases in other risky day in the United States (1). The first drug used is often

636 6 May 2014 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 160 • Number 9 www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 10/31/2016

Interventions to Reduce Drug Use in Children and Adolescents Clinical Guideline

marijuana (by approximately two thirds of adolescents). Nonmedical use of prescription and over-the-counter

However, for more than 1 in 4 adolescents, the initial drug medications involves taking a drug for reasons other than

is a prescription medication taken for nonmedical purposes why it was prescribed or recommended, often by a person

(most often an opioid pain medicine). The percentage of other than for whom it was prescribed and for the purpose

adolescents aged 12 to 17 years who report drug use in the of “getting high.” The largest classes of prescription medi-

past month is greater than those who report cigarette use cations used for nonmedical purposes within the scope of

and only slightly less than those who report alcohol use this recommendation are opioid pain relievers, central ner-

(9.5% vs. 6.6% vs. 12.9%, respectively) (1). More than vous system depressants (commonly called tranquilizers),

7% of adolescents aged 12 to 17 years report marijuana use and stimulants, including medications used to treat

in the past month; 2.8% report using prescription-type attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nonmedical use of

drugs for nonmedical purposes; and less than 1% report over-the-counter medications, including dextromethor-

cocaine, hallucinogen, or inhalant use (1). In addition, in phan and cough suppressants, also occurs. This recommen-

2012, 4.4% of eighth-, tenth-, and twelfth-grade students dation applies only to psychoactive medications and does

reported using over-the-counter cough or cold medicine in not include the nonmedical use of anabolic steroids or ath-

the past year for nonmedical reasons (2). In 2012, the rate letic performance– enhancing drugs.

of drug dependence or abuse in adolescents aged 12 to 17 Although alcohol and tobacco are both psychoactive

years was 4% (1). drugs, they are not the focus of this recommendation. The

Drug use is associated with many negative health, so- USPSTF has made separate recommendations on screening

cial, and economic consequences and is a significant con- and counseling adolescents for tobacco and alcohol use.

tributor to 3 of the leading causes of death among adoles- Screening Tests

cents: motor vehicle accidents, homicide, and suicide.

Although the focus of this recommendation is not on

Consequences not only arise from frequent or heavy drug

screening for drug use, screening may allow behavioral in-

use, but use increases risk-taking behaviors while intoxi-

terventions to be tailored to the situation of the individual

cated, such as driving under the influence, unsafe sexual

adolescent. The American Academy of Pediatrics recom-

activity, and violence. In 2011, more than 150 000 adoles-

mends the CRAFFT (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends,

cents were treated in emergency departments for compli- Trouble) screening tool (available at www.projectcork.org

cations of illicit drug and nonmedical pharmaceutical /clinical_tools/pdf/CRAFFT.pdf), which was developed

use (3). specifically for use with adolescents. The 2-part screening

Scope of Review tool takes less than 2 minutes to administer and screens for

The USPSTF uses the term drug use to reflect a spec- alcohol and drug use. It is designed to be delivered as an

trum of behaviors that may progress, typically in stages. interview or paper- or computer-based self-report. It is sim-

The stage of primary abstinence includes persons who ple to score and has good sensitivity and specificity across a

never use drugs. The stages of use begin with experimen- range of populations and settings.

tation and may progress from limited use to problematic or Although the USPSTF concludes that the evidence is

harmful use and mild to severe substance use disorder. The insufficient to make a recommendation for or against be-

stage of secondary abstinence includes persons who stop havioral interventions to prevent or reduce drug use in

using drugs. The focus of this recommendation is 2-fold: children and adolescents who do not have a substance use

interventions to help adolescents who have never used disorder, primary care professionals may consider screening

drugs to remain abstinent and interventions to help ado- adolescent patients to identify those who are experiencing

lescents who are using drugs but do not meet criteria for a consequences of drug use. Adolescents who have a sub-

stance use disorder should receive appropriate treatment.

substance use disorder to reduce or stop their use. Adoles-

cents who are diagnosed with a substance use disorder Effectiveness of Behavioral Interventions to Change

require treatment. These treatments are not part of clin- Behavior and Outcomes

ical prevention and are outside the scope of this The USPSTF found only 6 fair- or good-quality stud-

recommendation. ies of 4 primary care–relevant behavioral interventions

This review includes consideration of illicit drug and that focused on reducing drug use in adolescents (4). These

nonmedical pharmaceutical use, which includes both pre- interventions included face-to-face counseling, videos,

scription and over-the-counter medications. Although the print materials, and interactive computer-based tools. Al-

USPSTF recognizes that laws that apply to marijuana use though the interventions substantially varied in their inten-

are shifting in some areas of the United States, potentially sity, components, populations, and sample sizes, they pro-

raising questions about whether marijuana is an illicit drug, vide almost no evidence of significant improvements in

the Task Force includes marijuana use within the scope of health outcomes. A few changes in drug use and drug ini-

this recommendation. Other illicit drugs within the scope tiation were found, but given the lack of clear and consis-

of this recommendation include cocaine, heroin, halluci- tent findings and the overall small evidence base, the

nogens, and inhalants. USPSTF could not draw definitive conclusions. It is pos-

www.annals.org 6 May 2014 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 160 • Number 9 637

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 10/31/2016

Clinical Guideline Interventions to Reduce Drug Use in Children and Adolescents

sible that brief primary care–relevant interventions do not medical use of prescription drugs in all 3 studies after 12 to

significantly affect adolescent drug use or that more effec- 24 months, as well as statistically significant decreases in

tive interventions may need to be developed. inhalant use in 1 study. The studies used an unusual and

Harris and colleagues (5) conducted a large trial of a difficult-to-interpret measure of drug use. It seems that

brief behavioral intervention provided in primary care overall drug use was very low across the studies, and the

practice settings. The intervention included computer- clinical significance of the results is difficult to determine.

assisted screening of more than 2000 adolescents aged 12 It is not clear whether the intervention helped girls who

to 18 years using the CRAFFT screening tool; a non- had never used drugs to remain abstinent or helped a few

tailored, brief, computer-based educational session; and 2 girls who were frequently using drugs to reduce or stop

to 3 minutes of tailored advice from the patient’s primary their drug use (7–10).

care clinician. Clinicians were provided with training and

Potential Harms of Behavioral Interventions

given talking points for each patient based on his or her

No studies provided evidence about the magnitude of

responses to the CRAFFT questionnaire. The intervention

the harms of behavioral interventions to prevent or reduce

targeted alcohol and marijuana use and took fewer than 10

drug use. Although the USPSTF recognizes that theoretical

minutes to complete. Although relevant in U.S. practice,

harms, such as the potential to increase drug initiation

the U.S. group of the study found no significant differ-

through a false sense of security, may exist, it believes that

ences between the intervention and control groups in mar-

the harms of behavioral interventions are probably small to

ijuana initiation, cessation, or consequences of use at the

none.

12-month follow-up. The study did find a statistically sig-

nificant reduction in the number of adolescents who did Estimate of Magnitude of Net Benefit

not initiate alcohol use in the U.S. intervention group at Given the limited and inconsistent available evidence

12 months (adjusted relative risk ratio, 0.66 [95% CI, 0.47 about the effectiveness of behavioral interventions to pre-

to 0.93]). The study’s parallel group in the Czech Republic vent or reduce illicit drug use and the nonmedical use of

found a large and statistically significant reduction in the prescription medications, the USPSTF concludes that the

initiation of marijuana use and an increase in cessation balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined.

rates at 12 months in the intervention group (adjusted

Associated Issues

relative risk ratio, 0.47 [CI, 0.29 to 0.76] and 2.53 [CI,

Illicit drug and nonmedical pharmaceutical use is as-

1.06 to 6.05], respectively) but no effect on alcohol use (5).

sociated with alcohol and tobacco use in adolescents. Al-

Walton and colleagues (6) conducted a study that in-

though it was once believed that tobacco and alcohol use

volved more than 300 U.S. adolescents aged 12 to 18 years

were usually precursors to drug use, it is important to rec-

who reported marijuana use. The trial compared the effec-

ognize that more adolescents use drugs than tobacco.

tiveness of an interactive computer-delivered intervention

Drugs, including illicit drugs, may be easier for U.S. ado-

and a therapist-delivered intervention based on motiva-

lescents to obtain than tobacco products. The strong asso-

tional interviewing with a control group. Both interven-

ciation of use suggests that primary care professionals may

tions took approximately 35 to 40 minutes to complete.

want to screen for use of all 3 substances if they choose to

The study authors concluded that there were “no effects of

screen for any. Because of the strong association among

a computer or therapist behavioral intervention on canna-

tobacco, alcohol, and drug use in adolescents, researchers

bis use” (6).

should consider developing behavioral interventions to pre-

Schinke and colleagues (7–10) conducted 3 studies,

vent and reduce use of all 3 substances. However, it is also

reported in 4 publications, of a similar intensive, computer-

possible that effective strategies for preventing and reduc-

based behavioral intervention delivered at home to mothers

ing use may need to be targeted, especially among different

and their daughters aged 11 to 14 years. Mothers and

communities of adolescents and even for different drugs.

daughters each completed a 45-minute interactive session

Primary care professionals should remain aware of sub-

weekly for 9 weeks; some sessions were completed sepa-

stance use patterns in their communities and the evolving

rately and others completed together. The goals for the

evidence on effective prevention interventions.

mothers were not solely focused on drug use and included

improving communication with their daughters, monitor- Response to Public Comment

ing their daughters’ behaviors and activities, building their A draft version of this recommendation statement was

daughters’ self-image and self-esteem, and establishing posted for public comment on the USPSTF Web site from

rules and consequences for substance use. For the daugh- 1 October to 28 October 2013. All comments were re-

ters, the program focused on building skills for managing viewed and considered. Overall, most comments agreed

stress, conflict, and mood; dealing with peer pressure; and that more evidence is needed to evaluate the effectiveness

improving body esteem and self-efficacy. The studies of behavioral interventions to reduce drug use. The recom-

measured several outcomes and examined marijuana, non- mendation statement was revised in response to comments

medical prescription drug, and inhalant use. They found seeking clarification of the terminology used and the pa-

statistically significant decreases in marijuana use and non- tient population to whom the recommendation statement

638 6 May 2014 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 160 • Number 9 www.annals.org

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 10/31/2016

Interventions to Reduce Drug Use in Children and Adolescents Clinical Guideline

applies. A few comments requested that a future single study or other purposes: USPSTF. Authors not named here have disclosed

recommendation statement be issued that includes alcohol, no conflicts of interest. Authors followed the policy regarding conflicts

tobacco, and drug use in children and adolescents. The of interest described at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/methods

.htm. Disclosures can also be viewed at www.acponline.org/authors

USPSTF currently has separate recommendation state- /icmje/ConflictOfInterestForms.do?msNum⫽M14-0334.

ments that address each substance and will consider con-

currently updating recommendation statements that per-

tain to screening and interventions for all 3 areas in the Requests for Single Reprints: Reprints are available from the USPSTF

Web site (www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org).

future.

UPDATE OF PREVIOUS USPSTF RECOMMENDATION References

In 2008, the USPSTF issued a recommendation that 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from

focused exclusively on screening for illicit drug use (11). the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Find-

ings. NSDUH Series H-46. HHS publication no. (SMA) 13-4795. Rockville,

That recommendation included screening in adolescents,

MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013.

adults, and pregnant women. At that time, it concluded Accessed at www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2012SummNatFindDetTables

that the evidence was not sufficient to recommend for or /NationalFindings/NSDUHresults2012.htm on 4 February 2014.

against screening in any of these populations (I statement). 2. Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the

In updating this recommendation, and in response to feed- Future National Results on Drug Use: 1975–2012. 2012 Overview: Key Find-

ings on Adolescent Drug Use. Ann Arbor, MI: Univ of Michigan; 2013. Accessed

back from the public, the Task Force chose to refine the at www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2012.pdf on 4

scope of the recommendation in several notable ways. The February 2014.

scope of this recommendation was narrowed to focus only 3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug Abuse

on adolescents and children, was broadened to include il- Warning Network, 2011: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency

Department Visits. HHS publication no. (SMA) 13-4760. DAWN Series

licit drug and nonmedical pharmaceutical use, and shifted D-39. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Admin-

from screening to the effectiveness of behavioral interven- istration; 2013. Accessed at www.samhsa.gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED

tions to prevent and reduce drug use. A separate recom- /DAWN2k11ED.htm on 4 February 2014.

mendation will be developed on illicit drug and nonmed- 4. Patnode CD, O’Connor E, Rowland M, Burda BU, Perdue LA, Whitlock

EP. Primary Care Behavioral Interventions to Prevent or Reduce Illicit Drug and

ical pharmaceutical use in adults and pregnant women. Nonmedical Pharmaceutical Use in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Ev-

idence Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Evidence Synthesis

No. 106. AHRQ publication no. 13-05177-EF-1. Rockville, MD: Agency for

RECOMMENDATIONS OF OTHERS Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends 5. Harris SK, Csémy L, Sherritt L, Starostova O, Van Hook S, Johnson J, et al.

that all adolescents be screened for alcohol and drug use Computer-facilitated substance use screening and brief advice for teens in primary

and that, based on the results, clinicians conduct further care: an international trial. Pediatrics. 2012;129:1072-82. [PMID: 22566420]

6. Walton MA, Bohnert K, Resko S, Barry KL, Chermack ST, Zucker RA,

assessment, provide guidance and brief counseling inter- et al. Computer and therapist based brief interventions among cannabis-using

ventions, and, if appropriate, refer for treatment (12). The adolescents presenting to primary care: one year outcomes. Drug Alcohol De-

American Academy of Family Physicians’ recommendation pend. 2013;132:646-53. [PMID: 23711998]

on interventions to address drug use in children and ado- 7. Schinke SP, Fang L, Cole KC. Computer-delivered, parent-involvement in-

tervention to prevent substance use among adolescent girls. Prev Med. 2009;49:

lescents is currently under review. 429-35. [PMID: 19682490]

8. Schinke SP, Fang L, Cole KC. Preventing substance use among adolescent

From the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Rockville, Maryland. girls: 1-year outcomes of a computerized, mother-daughter program. Addict Be-

hav. 2009;34:1060-4. [PMID: 19632053]

Disclaimer: Recommendations made by the USPSTF are independent of 9. Fang L, Schinke SP, Cole KC. Preventing substance use among early Asian-

the U.S. government. They should not be construed as an official posi- American adolescent girls: initial evaluation of a web-based, mother-daughter

tion of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. program. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47:529-32. [PMID: 20970090]

Department of Health and Human Services. 10. Fang L, Schinke SP. Two-year outcomes of a randomized, family-based

substance use prevention trial for Asian American adolescent girls. Psychol Addict

Behav. 2013;27:788-98. [PMID: 23276322]

Financial Support: The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary body.

11. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Illicit Drug Use: U.S.

The U.S. Congress mandates that the Agency for Healthcare Research Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Rockville, MD:

and Quality support the operations of the USPSTF. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

12. Levy SJ, Kokotailo PK; Committee on Substance Abuse. Substance use

Disclosures: Dr. Moyer: Support for travel to meetings for the study or screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediat-

other purposes: AHRQ. Dr. Owens: Support for travel to meetings for the rics. 2011;128:e1330-40. [PMID: 22042818]

www.annals.org 6 May 2014 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 160 • Number 9 639

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 10/31/2016

Annals of Internal Medicine

APPENDIX: U.S. PREVENTIVE SERVICES TASK FORCE (Pima County Department of Health, Tucson, Arizona); Jessica

Members of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force at the Herzstein, MD, MPH (Air Products, Allentown, Pennsylvania);

time this recommendation was finalized† are Virginia A. Moyer, Douglas K. Owens, MD, MS (Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health

MD, MPH, Chair (American Board of Pediatrics, Chapel Hill, Care System, Palo Alto, and Stanford University, Stanford, Cal-

North Carolina); Michael L. LeFevre, MD, MSPH, Co-Vice ifornia); William R. Phillips, MD, MPH (University of Wash-

Chair (University of Missouri School of Medicine, Columbia, ington, Seattle, Washington); and Michael P. Pignone, MD,

Missouri); Albert L. Siu, MD, MSPH, Co-Vice Chair (Mount MPH (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Caro-

Sinai School of Medicine, New York, and James J. Peters Veter- lina). Former USPSTF members Adelita Gonzales Cantu, RN,

ans Affairs Medical Center, Bronx, New York); Linda Ciofu Bau- PhD, and Wanda Nicholson, MD, MPH, MBA, also contrib-

mann, PhD, RN (University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wiscon- uted to the development of this recommendation.

sin); Susan J. Curry, PhD (University of Iowa College of Public † For a list of current Task Force members, go to www

Health, Iowa City, Iowa); Mark Ebell, MD, MS (University of .uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/members.htm.

Georgia, Athens, Georgia); Francisco A.R. Garcı́a, MD, MPH

Appendix Table 1. What the USPSTF Grades Mean and Suggestions for Practice

Grade Definition Suggestions for Practice

A The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the Offer/provide this service.

net benefit is substantial.

B The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the Offer/provide this service.

net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net

benefit is moderate to substantial.

C The USPSTF recommends selectively offering or providing this service Offer/provide this service for selected patients depending on individual

to individual patients based on professional judgment and patient circumstances.

preferences. There is at least moderate certainty that the net

benefit is small.

D The USPSTF recommends against the service. There is moderate or Discourage the use of this service.

high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms

outweigh the benefits.

I statement The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to Read the Clinical Considerations section of the USPSTF Recommendation

assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is Statement. If the service is offered, patients should understand the

lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits uncertainty about the balance of benefits and harms.

and harms cannot be determined.

Appendix Table 2. USPSTF Levels of Certainty Regarding Net Benefit

Level of Certainty* Description

High The available evidence usually includes consistent results from well-designed, well-conducted studies in representative

primary care populations. These studies assess the effects of the preventive service on health outcomes. This

conclusion is therefore unlikely to be strongly affected by the results of future studies.

Moderate The available evidence is sufficient to determine the effects of the preventive service on health outcomes, but

confidence in the estimate is constrained by such factors as:

the number, size, or quality of individual studies;

inconsistency of findings across individual studies;

limited generalizability of findings to routine primary care practice; and

lack of coherence in the chain of evidence.

As more information becomes available, the magnitude or direction of the observed effect could change, and this

change may be large enough to alter the conclusion.

Low The available evidence is insufficient to assess effects on health outcomes. Evidence is insufficient because of:

the limited number or size of studies;

important flaws in study design or methods;

inconsistency of findings across individual studies;

gaps in the chain of evidence;

findings that are not generalizable to routine primary care practice; and

a lack of information on important health outcomes.

More information may allow an estimation of effects on health outcomes.

* The USPSTF defines certainty as “likelihood that the USPSTF assessment of the net benefit of a preventive service is correct.” The net benefit is defined as benefit minus

harm of the preventive service as implemented in a general primary care population. The USPSTF assigns a certainty level on the basis of the nature of the overall evidence

available to assess the net benefit of a preventive service.

www.annals.org 6 May 2014 Annals of Internal Medicine Volume 160 • Number 9

Downloaded From: http://annals.org/ on 10/31/2016

You might also like

- Surgery OSCE QuestionsDocument0 pagesSurgery OSCE QuestionsSinginiD86% (7)

- The Mechanism of Letting GoDocument6 pagesThe Mechanism of Letting Goxdownloader98% (42)

- Pharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,PharmacovigilanceFrom EverandPharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,PharmacovigilanceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Screen Drogas - Amf 2009Document2 pagesScreen Drogas - Amf 2009OSCAR_DF_mxNo ratings yet

- NIDA - ASSIST Modified PDFDocument22 pagesNIDA - ASSIST Modified PDFdinarNo ratings yet

- Order 3150873Document5 pagesOrder 3150873DENNIS GITAHINo ratings yet

- Shehnaz 2014Document17 pagesShehnaz 2014Divyanshu AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Misuse: Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions in Primary Care GuidelinesDocument11 pagesAlcohol Misuse: Screening and Behavioral Counseling Interventions in Primary Care GuidelinesRosnerNo ratings yet

- Clinical GuidelineDocument7 pagesClinical GuidelineTyas YuLinda DeCeNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument6 pagesDownloadMr AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Self-Medication Practices and Its Associated Factors in Rural Bengaluru, Karnataka, IndiaDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Self-Medication Practices and Its Associated Factors in Rural Bengaluru, Karnataka, IndiaVijaya RaniNo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment 1Document8 pagesIndividual Assignment 110PAMP2Dionisio, Ira Joy D.No ratings yet

- Young Adult Sequelae of Adolescent Cannabis Use: An Integrative AnalysisDocument8 pagesYoung Adult Sequelae of Adolescent Cannabis Use: An Integrative Analysisirribarra.nlopez3046No ratings yet

- Unlicensed and Off Label Uses of Drugs in Paediatrics A Review - Cuzzolin, 2003Document7 pagesUnlicensed and Off Label Uses of Drugs in Paediatrics A Review - Cuzzolin, 2003Mara KalitaNo ratings yet

- Prescribing Patterns of Drugs in Outpatient Department of Paediatrics in Tertiary Care HospitalDocument12 pagesPrescribing Patterns of Drugs in Outpatient Department of Paediatrics in Tertiary Care HospitalAleena Maria KurisinkalNo ratings yet

- Problems of Irrational Drug Use: Session GuideDocument21 pagesProblems of Irrational Drug Use: Session GuideAmit NikoseNo ratings yet

- Co-Prescription Trends in A Large Cohort of Subjects Predict Substantial Drug-Drug InteractionsDocument19 pagesCo-Prescription Trends in A Large Cohort of Subjects Predict Substantial Drug-Drug Interactionsadern-07huepfendNo ratings yet

- Drug Prescribing and Dispensing Pattern in PediatrDocument6 pagesDrug Prescribing and Dispensing Pattern in PediatrAestherielle SeraphineNo ratings yet

- STart StroppDocument1 pageSTart StroppHoang Mai NguyenNo ratings yet

- Polysubstance Use - Diagnostic Challenges, Patterns of Use and HealthDocument7 pagesPolysubstance Use - Diagnostic Challenges, Patterns of Use and HealthAndres Felipe Silva IbarraNo ratings yet

- Prescription Drug Abuse ThesisDocument5 pagesPrescription Drug Abuse Thesistpynawfld100% (2)

- Non-Prescription Medicines and Australian Community Pharmacy Interventions: Rates and Clinical SignificanceDocument10 pagesNon-Prescription Medicines and Australian Community Pharmacy Interventions: Rates and Clinical SignificanceMarcelle GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Cannabis Lower Risk Use GuidelinesDocument16 pagesCannabis Lower Risk Use GuidelinesZélia TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- NURS-FPX6026 - WhitneyPierre - Assessment 1-2docxDocument9 pagesNURS-FPX6026 - WhitneyPierre - Assessment 1-2docxCaroline AdhiamboNo ratings yet

- The Specter of Opiate Addiction in Reproductive Medicine: William D. Schlaff, M.DDocument2 pagesThe Specter of Opiate Addiction in Reproductive Medicine: William D. Schlaff, M.DericNo ratings yet

- Dawson Compton Grant 2010Document10 pagesDawson Compton Grant 2010Francisco Porá TuzinkievichNo ratings yet

- Pharmacovigilance - Review ArticleDocument4 pagesPharmacovigilance - Review ArticleKishore100% (1)

- Literature Review Medication Safety in AustraliaDocument5 pagesLiterature Review Medication Safety in Australiaea7gpeqm100% (1)

- EBP Deliverable Module 2Document6 pagesEBP Deliverable Module 2Marian SmithNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Estrat en APDocument6 pagesAlcohol Estrat en APPach AdamsNo ratings yet

- 16 Quality of Spon ReportingDocument5 pages16 Quality of Spon ReportingSagaram ShashidarNo ratings yet

- Institute For Safe Medication PracticesDocument6 pagesInstitute For Safe Medication Practicesadza30No ratings yet

- The Drug Abuse Screening TestDocument9 pagesThe Drug Abuse Screening TestMaria Paz RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Drug Prescribing Pattern and Prescription Error in Elderly: A Retrospective Study of Inpatient RecordDocument5 pagesDrug Prescribing Pattern and Prescription Error in Elderly: A Retrospective Study of Inpatient RecordhukamaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Pharma DostDocument3 pagesChapter 1 - Pharma DostabinchandrakumarNo ratings yet

- Problems of Irrational Drug Use: Session GuideDocument22 pagesProblems of Irrational Drug Use: Session Guidearyo aryoNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review On Medication Errors 2015Document3 pagesA Systematic Review On Medication Errors 2015Trang Hoàng ThịNo ratings yet

- Herbal Drug InteractionsDocument30 pagesHerbal Drug Interactionsdewinta_sukmaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Self-Medication Practice ADocument16 pagesAssessment of Self-Medication Practice ASyed Shabbir HaiderNo ratings yet

- Re Iew Factors Affecting Rational DR G Se (RD), CO Liance and AstageDocument19 pagesRe Iew Factors Affecting Rational DR G Se (RD), CO Liance and Astagenadirakhalid143No ratings yet

- Paediatric Drug Use With Focus On Off-Label Prescriptions in Lombardy and Implications For Therapeutic ApproachesDocument7 pagesPaediatric Drug Use With Focus On Off-Label Prescriptions in Lombardy and Implications For Therapeutic ApproachesDuat NDNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: US Emergency Department Visits For Outpatient Adverse Drug Events, 2013-2014Document26 pagesHHS Public Access: US Emergency Department Visits For Outpatient Adverse Drug Events, 2013-2014rosianaNo ratings yet

- Self PDFDocument5 pagesSelf PDFTommy Winahyu PuriNo ratings yet

- Physician Factors Associated With Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Medication UseDocument9 pagesPhysician Factors Associated With Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Medication UseratnatriaaNo ratings yet

- Nurses' Role in Preventing Prescription Opioid Diversion: HoursDocument7 pagesNurses' Role in Preventing Prescription Opioid Diversion: HoursPrasoon PremrajNo ratings yet

- The KIDs ListDocument17 pagesThe KIDs ListSantiago MerloNo ratings yet

- Jureidini 2006Document10 pagesJureidini 2006Carmen IonitaNo ratings yet

- Adb Adb0000026 PDFDocument8 pagesAdb Adb0000026 PDFΓιάννης ΓιαννέτοςNo ratings yet

- Evidencebased PracticeDocument10 pagesEvidencebased Practicerevathidadam55555No ratings yet

- 21 Iajps21102017 PDFDocument9 pages21 Iajps21102017 PDFBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNo ratings yet

- 2018 Value-in-HeDocument7 pages2018 Value-in-HeArchie CabacheteNo ratings yet

- Morbidity Profile and Prescribing Patterns Among Outpatients in A Teaching Hospital in Western NepalDocument7 pagesMorbidity Profile and Prescribing Patterns Among Outpatients in A Teaching Hospital in Western Nepalpolosan123No ratings yet

- NAPNAP Position Statement On The Acute Care Pediatric Nurse PractitionerDocument17 pagesNAPNAP Position Statement On The Acute Care Pediatric Nurse PractitionerMichael Greg Pengson LambiguitNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Self-Medication Among Harar Health Sciences College Students, Harar, Eastern EthiopiaDocument6 pagesAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Self-Medication Among Harar Health Sciences College Students, Harar, Eastern EthiopiaAzra SyafiraNo ratings yet

- Chibueze 2018Document8 pagesChibueze 2018AyuNo ratings yet

- Deprescribing Tools: A Review of The Types of Tools Available To Aid Deprescribing in Clinical PracticeDocument10 pagesDeprescribing Tools: A Review of The Types of Tools Available To Aid Deprescribing in Clinical PracticeandresadarvegNo ratings yet

- Systemtic ReviewDocument16 pagesSystemtic ReviewMohammad Ali Al-garniNo ratings yet

- Theory of Planned Behavior On The Psycho dd2b21d0Document10 pagesTheory of Planned Behavior On The Psycho dd2b21d0iansgor mikeNo ratings yet

- Side Effects From Use of One oDocument8 pagesSide Effects From Use of One oMary JohnNo ratings yet

- Minimizing Medication Errors Practical Pointers For PrescribersDocument4 pagesMinimizing Medication Errors Practical Pointers For PrescribersLuciana OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Prescription Medication Borrowing and Sharing Among Women of Reproductive AgeDocument8 pagesPrescription Medication Borrowing and Sharing Among Women of Reproductive AgeWulan CerankNo ratings yet

- Consenso Europeo Tep 2014Document48 pagesConsenso Europeo Tep 2014lbritez7No ratings yet

- Conjuntivitis AlérgicaDocument13 pagesConjuntivitis Alérgicalbritez7No ratings yet

- Fibrosis PulmonarDocument58 pagesFibrosis Pulmonarlbritez7No ratings yet

- Pancreatitis Aguda Guías ClínicasDocument1 pagePancreatitis Aguda Guías Clínicaslbritez7No ratings yet

- Apendicitis AgudaDocument17 pagesApendicitis Agudalbritez7No ratings yet

- Constipación CrónicaDocument7 pagesConstipación Crónicalbritez7No ratings yet

- DISFAGIA ConcensoDocument9 pagesDISFAGIA Concensolbritez7No ratings yet

- Mindfulness Meditation For Adolescent Stress and Well-Being: A Systematic Review of The Literature With Implications For School Health ProgramsDocument8 pagesMindfulness Meditation For Adolescent Stress and Well-Being: A Systematic Review of The Literature With Implications For School Health ProgramsMadame MoseilleNo ratings yet

- References in ThesisDocument2 pagesReferences in ThesisjonalynNo ratings yet

- Filipino Nurses For GermanyDocument6 pagesFilipino Nurses For GermanyRose Dyan Petallo Plandano50% (4)

- Drlee - Restless Leg SyndromeDocument1 pageDrlee - Restless Leg SyndromeSouheila MniNo ratings yet

- 1.3.FOUNDATIONS FOR Nursing Education PDFDocument23 pages1.3.FOUNDATIONS FOR Nursing Education PDFbereketNo ratings yet

- Acog 2019 Preeclampsia PDFDocument25 pagesAcog 2019 Preeclampsia PDFJhoel Zuñiga LunaNo ratings yet

- Your College Experience Transformation - Instructions and Grading RubricDocument5 pagesYour College Experience Transformation - Instructions and Grading Rubricapi-535279488No ratings yet

- Case Study-Pathways Out of Poverty (Progresa Opportunidaddes in Mexico)Document5 pagesCase Study-Pathways Out of Poverty (Progresa Opportunidaddes in Mexico)sherryl caoNo ratings yet

- Chapter Four: Operational Plan: 4.1 Production, Facilities and CapacityDocument4 pagesChapter Four: Operational Plan: 4.1 Production, Facilities and CapacityMonicah MuthokaNo ratings yet

- Codes For InfomercialDocument4 pagesCodes For Infomercialmark gilberoNo ratings yet

- ID Hubungan Kandungan Arsen As Dalam Urin Dengan Kejadian Goiter Pada Petani SayurDocument9 pagesID Hubungan Kandungan Arsen As Dalam Urin Dengan Kejadian Goiter Pada Petani SayurRedza RahimNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge and Attitude of Pharmacists Toward The Side Effects of Anesthetics in Patients With Hypertension: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument9 pagesAssessment of Knowledge and Attitude of Pharmacists Toward The Side Effects of Anesthetics in Patients With Hypertension: A Cross-Sectional StudyMediterr J Pharm Pharm SciNo ratings yet

- Đề HSG Trường 2023 Khối 11LinhDocument11 pagesĐề HSG Trường 2023 Khối 11LinhHàNo ratings yet

- SDS 175 BEST ONE SeriesDocument6 pagesSDS 175 BEST ONE SeriesWitara SajaNo ratings yet

- Veneers - Fantasy, Risk, SuccessDocument990 pagesVeneers - Fantasy, Risk, SuccessflaysminNo ratings yet

- Naturopathic Nutrition: Folate / Folic Acid, B12 and Biotin & OthersDocument29 pagesNaturopathic Nutrition: Folate / Folic Acid, B12 and Biotin & Othersglenn johnstonNo ratings yet

- AlexithymiaDocument18 pagesAlexithymiaEunike GraciaNo ratings yet

- Letter To EditorDocument12 pagesLetter To EditorHIMANSHU GOELNo ratings yet

- MS 220kVLCCPanelBCFDRD07 PDFDocument12 pagesMS 220kVLCCPanelBCFDRD07 PDFSuprodip DasNo ratings yet

- Up To Date. Acute Sinusitis and RhinosinusitisDocument28 pagesUp To Date. Acute Sinusitis and RhinosinusitisGuardito PequeñoNo ratings yet

- Driving NC III (Passenger Bus Straight Truck)Document113 pagesDriving NC III (Passenger Bus Straight Truck)Daniel S. Santos100% (5)

- Lift Plan-Wilco Extenral StairsDocument25 pagesLift Plan-Wilco Extenral StairsEdgar ChecaNo ratings yet

- HRM Report - Group 2Document31 pagesHRM Report - Group 2Huệ Hứa ThụcNo ratings yet

- Prost Ho Don TicDocument175 pagesProst Ho Don Ticrxmskdkd33No ratings yet

- Introductory Lecture On Environment and HealthDocument18 pagesIntroductory Lecture On Environment and HealthDenmar GarciaNo ratings yet

- MSDS Delstar Plus (Profenofos) Qingdao PDFDocument6 pagesMSDS Delstar Plus (Profenofos) Qingdao PDFAgung Septama AndrifazaNo ratings yet

- Best Sports Bra (Category Relaxation and Wellness)Document21 pagesBest Sports Bra (Category Relaxation and Wellness)Iqra 2000No ratings yet

- Monnal t75 Air Liquide Ventilator PDFDocument10 pagesMonnal t75 Air Liquide Ventilator PDFFederico DonfrancescoNo ratings yet