Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0448 Taps Jennifer

0448 Taps Jennifer

Uploaded by

MayraCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Medaille New Lesson Plan 3 Sheila HolmesDocument10 pagesMedaille New Lesson Plan 3 Sheila Holmesapi-418734224No ratings yet

- MFDM™ AiDocument48 pagesMFDM™ AiAyusman Panda50% (4)

- Flexible Instruction Delivery Plan (FIDP) : Quarter: Performance StandardDocument9 pagesFlexible Instruction Delivery Plan (FIDP) : Quarter: Performance StandardWeng Baymac II75% (8)

- Martin Mcquillan-Post Theory New Directions in Criticism-Edinburgh University Press PDFDocument188 pagesMartin Mcquillan-Post Theory New Directions in Criticism-Edinburgh University Press PDFfekir64No ratings yet

- Hope 1Document4 pagesHope 1Emily T. Nonato100% (7)

- 20 Minute Phonemic Training for Dyslexia, Auditory Processing, and Spelling: A Complete Resource for Speech Pathologists, Intervention Specialists, and Reading TutorsFrom Everand20 Minute Phonemic Training for Dyslexia, Auditory Processing, and Spelling: A Complete Resource for Speech Pathologists, Intervention Specialists, and Reading TutorsNo ratings yet

- DYSPHAGIA GOALS LONG TERM GOALS - SWALLOWING - PDF Free Download PDFDocument6 pagesDYSPHAGIA GOALS LONG TERM GOALS - SWALLOWING - PDF Free Download PDFMayraNo ratings yet

- Paul H. Hirst - Knowledge and The Curriculum - A Collection of Philosophical Papers PDFDocument156 pagesPaul H. Hirst - Knowledge and The Curriculum - A Collection of Philosophical Papers PDFDewi Sari WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Hope 3Document4 pagesHope 3Emily T. NonatoNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesRoessi Mae Abude AratNo ratings yet

- English 7 Cur MapDocument26 pagesEnglish 7 Cur MapVan DamNo ratings yet

- English 7 Curriculum MapdocxDocument26 pagesEnglish 7 Curriculum MapdocxStella Mariz ArganaNo ratings yet

- RPS KPT English 1Document5 pagesRPS KPT English 1Anna FauziahNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Lesson PlansDocument25 pagesAssignment 1 Lesson Plansapi-369323765No ratings yet

- Smith Metro Symp 15 ApraxiaDocument30 pagesSmith Metro Symp 15 ApraxiachamilaNo ratings yet

- Julia Mershon TLP HandoutDocument5 pagesJulia Mershon TLP Handoutapi-529096611No ratings yet

- Canchild - BrochuresDocument20 pagesCanchild - Brochurescharest.catherineNo ratings yet

- Training Design CSEDocument5 pagesTraining Design CSEMilesAlidoRamentoNo ratings yet

- Sight Word and Phonics Training in Children With DyslexiaDocument17 pagesSight Word and Phonics Training in Children With DyslexiaYamin PhyoNo ratings yet

- 4 Selecting An AccommodationDocument8 pages4 Selecting An AccommodationArenga, Mary RoseNo ratings yet

- Individual Learning Monitoring PlanDocument7 pagesIndividual Learning Monitoring PlanJanet Manalo GamayotNo ratings yet

- MI Symp 2008 Deaf Ed Toolkit2Document98 pagesMI Symp 2008 Deaf Ed Toolkit2Muhammad-YounusNo ratings yet

- Colaboración Fono y EducadoresDocument17 pagesColaboración Fono y EducadoresCamii MVNo ratings yet

- Eldoa Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesEldoa Lesson Planapi-359540985No ratings yet

- Southern Leyte State University - Bontoc CampusDocument5 pagesSouthern Leyte State University - Bontoc Campusjeden c. beltranNo ratings yet

- Prof Educ 2Document11 pagesProf Educ 2Cyrell RiezaNo ratings yet

- Masining Na PagpapahayagDocument14 pagesMasining Na PagpapahayagGeralyn Pelayo AlburoNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map English 7Document28 pagesCurriculum Map English 7Mark Cesar VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- DLP - Oral CommunicationDocument8 pagesDLP - Oral CommunicationAgnes Asuncion VelascoNo ratings yet

- Ucap 2016 UpdatedDocument2 pagesUcap 2016 Updatedapi-262717088No ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Region I Robert B. Estrella Memorial National High School Carmen East, Rosales, PangasinanDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Region I Robert B. Estrella Memorial National High School Carmen East, Rosales, PangasinanJaps GarciaNo ratings yet

- Presentation ParkerDocument17 pagesPresentation Parkerapi-456518489No ratings yet

- Planificacion Curricular 3er BguDocument16 pagesPlanificacion Curricular 3er BguethanNo ratings yet

- MTB MLE SyllabusDocument10 pagesMTB MLE Syllabusjade tagabNo ratings yet

- Mystery Science 1 TaskstreamDocument10 pagesMystery Science 1 Taskstreamapi-435596493No ratings yet

- Ele2 Week-4Document4 pagesEle2 Week-4nebrejakayeannvillelaNo ratings yet

- Assessing Listening and Speaking Skills. ERIC DigestDocument7 pagesAssessing Listening and Speaking Skills. ERIC DigestDini HaryantiNo ratings yet

- SW285@jh - Edu/: Classroom Management IDocument16 pagesSW285@jh - Edu/: Classroom Management Iapi-506389013No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan PortDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Portapi-397840564No ratings yet

- Canchild - Information - SheetDocument10 pagesCanchild - Information - Sheetcharest.catherineNo ratings yet

- Mystery Science 2 Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesMystery Science 2 Lesson Planapi-435596493No ratings yet

- Observation Report 1 - Ariana SzepDocument3 pagesObservation Report 1 - Ariana Szepapi-666802127No ratings yet

- Storkel 2019 Using Developmental Norms For Speech Sounds As A Means of Determining Treatment Eligibility in SchoolsDocument9 pagesStorkel 2019 Using Developmental Norms For Speech Sounds As A Means of Determining Treatment Eligibility in SchoolsameeraNo ratings yet

- ASHAGuidelines Roles School SLPDocument63 pagesASHAGuidelines Roles School SLProkiah.razakNo ratings yet

- FotippopcycleDocument4 pagesFotippopcycleapi-572147191No ratings yet

- Microcurrucular Planning p1 1bgu Q1uemsa 21-22Document7 pagesMicrocurrucular Planning p1 1bgu Q1uemsa 21-22Gabriela CarrilloNo ratings yet

- Div Research Agenda DraftDocument5 pagesDiv Research Agenda DraftALBERT HISOLERNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument11 pagesLesson Planshai mozNo ratings yet

- Subject Curriculum: Enhanced K To 12 CurriculumDocument6 pagesSubject Curriculum: Enhanced K To 12 Curriculumjohn tuberaNo ratings yet

- Inclusion Look-Fors Dec 10 2013 Final VersionDocument9 pagesInclusion Look-Fors Dec 10 2013 Final Versionapi-249399814No ratings yet

- Workplan-On-Tutok BasaDocument2 pagesWorkplan-On-Tutok BasaJohn SyNo ratings yet

- Task-Based Language TeachingDocument15 pagesTask-Based Language TeachingAnntonitte Jumao-asNo ratings yet

- Consolidation SMEA AnajaoES Q1 2022-2023Document3 pagesConsolidation SMEA AnajaoES Q1 2022-2023grace jay sarinasNo ratings yet

- Midway EvaluationDocument5 pagesMidway Evaluationapi-316050165No ratings yet

- Fidp Hope 4Document4 pagesFidp Hope 4Almerto RicoNo ratings yet

- Expanding Possibilities in Distance LearningDocument1 pageExpanding Possibilities in Distance LearningAchristalyn Alanzalon TamondongNo ratings yet

- Sw-Cmisummer2020elasyllabus 1Document16 pagesSw-Cmisummer2020elasyllabus 1api-506389013No ratings yet

- Kip Matrix Previous Studies SampleDocument3 pagesKip Matrix Previous Studies Sampleapi-520857608No ratings yet

- PD LogDocument2 pagesPD Logapi-722832988No ratings yet

- Microcurrucular Planning p1 9 Egb Q 1uemsa 21-22Document5 pagesMicrocurrucular Planning p1 9 Egb Q 1uemsa 21-22Gabriela CarrilloNo ratings yet

- Nuernberger 2013Document7 pagesNuernberger 2013Wanessa AndradeNo ratings yet

- EL RoadmapDocument16 pagesEL RoadmapSherry PerryNo ratings yet

- HSL 826 Aural Rehabilitation - Pediatric Syllabus Spring 2017Document43 pagesHSL 826 Aural Rehabilitation - Pediatric Syllabus Spring 2017api-349133705No ratings yet

- Activities to Facilitate Motor, Sensory and Language Skills: Parent Resource Series, #2From EverandActivities to Facilitate Motor, Sensory and Language Skills: Parent Resource Series, #2Rating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- ASHA Guidelines For Early Intervention IncludeDocument10 pagesASHA Guidelines For Early Intervention IncludeMayraNo ratings yet

- IDDSI Framework Testing Methods 2.0 - 2019Document14 pagesIDDSI Framework Testing Methods 2.0 - 2019MayraNo ratings yet

- 1009 Swigert PDFDocument143 pages1009 Swigert PDFMayraNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Brain Injury 9.17.19Document2 pagesTraumatic Brain Injury 9.17.19MayraNo ratings yet

- How To Treat Speech Sound Disorders 2Document5 pagesHow To Treat Speech Sound Disorders 2MayraNo ratings yet

- SC23 Gillon PDFDocument115 pagesSC23 Gillon PDFMayraNo ratings yet

- SPEECH TO GO: Ideas For Speech and Language Therapy: ASHA 2010 PhiladelphiaDocument25 pagesSPEECH TO GO: Ideas For Speech and Language Therapy: ASHA 2010 PhiladelphiaMayraNo ratings yet

- Introduc On: Renee Perona, B.S. & Abbie Olszewski, PH.D., CCC-SLP University of Nevada, RenoDocument1 pageIntroduc On: Renee Perona, B.S. & Abbie Olszewski, PH.D., CCC-SLP University of Nevada, RenoMayraNo ratings yet

- Ethics For Real: Case Studies Applying The Asha Code of EthicsDocument36 pagesEthics For Real: Case Studies Applying The Asha Code of EthicsMayraNo ratings yet

- Frey - SLIDES - OregonSLHS Conference - PMDocument111 pagesFrey - SLIDES - OregonSLHS Conference - PMMayraNo ratings yet

- 1116 FochtDocument195 pages1116 FochtMayraNo ratings yet

- Power Point SlidesDocument42 pagesPower Point SlidesMayraNo ratings yet

- GraduateDocument60 pagesGraduateMayraNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement: Children Should Be Involved in Programs of Early LiteracyDocument1 pageThesis Statement: Children Should Be Involved in Programs of Early LiteracyMayraNo ratings yet

- Spanish Resources For Childrens LiteracyDocument4 pagesSpanish Resources For Childrens LiteracyMayraNo ratings yet

- Oral Summary 1: "My Stroke of Insight" by Jill Bolte Taylor (TED Talk)Document1 pageOral Summary 1: "My Stroke of Insight" by Jill Bolte Taylor (TED Talk)MayraNo ratings yet

- Mayra Martinez Journal 7Document3 pagesMayra Martinez Journal 7MayraNo ratings yet

- For A Deaf Son (Script)Document6 pagesFor A Deaf Son (Script)Mayra100% (2)

- Initial Evaluation Flow ChartDocument58 pagesInitial Evaluation Flow ChartMayraNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Syllabus 2018 2019Document4 pagesSocial Studies Syllabus 2018 2019Jan Erica R. OlipasNo ratings yet

- Mid Exam Advance 4Document5 pagesMid Exam Advance 4Ernesto Aroon Pardo MinayaNo ratings yet

- Krashen Does Duolingo TrumpDocument3 pagesKrashen Does Duolingo TrumpbuhlteufelNo ratings yet

- Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE)Document7 pagesCambridge English: Advanced (CAE)neoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 4 - Present and Past TenseDocument4 pagesLesson Plan 4 - Present and Past Tenseapi-301142304No ratings yet

- BUS 727 Organisational Behaviour PDFDocument245 pagesBUS 727 Organisational Behaviour PDFLawrenceNo ratings yet

- Sample of Proposal LettersDocument3 pagesSample of Proposal LettersAtiqullah sherzadNo ratings yet

- 3 - Bias - and - Variance - With - Mismatched - Data - DistributionsDocument2 pages3 - Bias - and - Variance - With - Mismatched - Data - DistributionsArchit MangrulkarNo ratings yet

- Understanding Historical Life in Its Own TermsDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Historical Life in Its Own TermsPat AlethiaNo ratings yet

- Beginners Somali GrammarDocument176 pagesBeginners Somali GrammarIbratoxiic KeNo ratings yet

- Lesson-Plan-Template Jaypee 1Document4 pagesLesson-Plan-Template Jaypee 1Jerrelyn MagtagadNo ratings yet

- Supervisor and Pre-Service Teacher Feedback Reflection School PlacementDocument6 pagesSupervisor and Pre-Service Teacher Feedback Reflection School Placementapi-465735315100% (1)

- Exam Stress ManagementDocument31 pagesExam Stress ManagementBio Sciences90% (10)

- 2 Comparative Performance Study of DBN LSTM CNN and SAE Models For Wind Speed and Direction Forecasting 2Document5 pages2 Comparative Performance Study of DBN LSTM CNN and SAE Models For Wind Speed and Direction Forecasting 2Audace DidaviNo ratings yet

- Heyl 2007 Ethnographic Interviewing Handbook of EthnographyDocument16 pagesHeyl 2007 Ethnographic Interviewing Handbook of EthnographyJosé LópezNo ratings yet

- Chomsky, N. 2011 - Language and Other Cognitive SystemsDocument17 pagesChomsky, N. 2011 - Language and Other Cognitive SystemsrigsitoNo ratings yet

- Self-Paced Learning Module: Diffun CampusDocument10 pagesSelf-Paced Learning Module: Diffun CampusCharlie MerialesNo ratings yet

- 7 Cs 0F CommunicationDocument19 pages7 Cs 0F CommunicationQaisar BasheerNo ratings yet

- Adjectives 2 PDFDocument2 pagesAdjectives 2 PDFSally Consumo KongNo ratings yet

- Peer Reviewed Title:: Jany, CarmenDocument263 pagesPeer Reviewed Title:: Jany, CarmenGuglielmo CinqueNo ratings yet

- TOEFL IBT Cliche in TOEFL Ibt Writing Ingtd SortedDocument2 pagesTOEFL IBT Cliche in TOEFL Ibt Writing Ingtd SortediEnglish Garhoud 1No ratings yet

- Ryle On MindDocument1 pageRyle On MindAnna Sophia EbuenNo ratings yet

- Writing Sub-Test: Occupational English Test Test InformationDocument10 pagesWriting Sub-Test: Occupational English Test Test InformationKamel Souidi100% (2)

- English 4Document7 pagesEnglish 4Jane Balneg-Jumalon TomarongNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Translating Metaphorical Collocations in The Holy Qur'anDocument9 pagesStrategies For Translating Metaphorical Collocations in The Holy Qur'anJOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN LINGUISTICSNo ratings yet

- Imrad Research Format 1 AutorecoveredDocument30 pagesImrad Research Format 1 AutorecoveredDave Libres Enterina60% (5)

- Display Stock Level 2 BeautyDocument4 pagesDisplay Stock Level 2 Beautymeera punNo ratings yet

0448 Taps Jennifer

0448 Taps Jennifer

Uploaded by

MayraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

0448 Taps Jennifer

0448 Taps Jennifer

Uploaded by

MayraCopyright:

Available Formats

Innovations For Four Innovations

Addressing Single Sound 1. Shift to General Education (through

Articulation Errors In Speech Improvement Class)

2. Articulation Resource Center (ARC)

School Settings 3. Research-

Research-Based Methods

4. Required Home Practice

Jennifer Taps, M.A., CCC-

CCC-SLP

San Diego Unified School District

2007 ASHA Conference Boston, MA

November 15, 2007

Why Reform Social Ramifications

Crowe-

Crowe-Hall (1991)

2004 Survey of 178 SDUSD SLPs Videos of kids with mild speech disorders and

821 IEPs for SSADD only typical speech

14 full-

full-time SLPs Interviewed 4th and 6th graders about their

Average length of treatment: 3 years

perceptions of these peer groups

Children with mild speech errors viewed more

Average amount of service: 30 min a wk

negatively than peers with typical speech

Most SLPs used traditional approach

Encouraged school districts to intervene because

of possible social and emotional impact

Compliance Review by CDE

Failed to establish educational need

The Reform

Innovation 1 – Shift speech service to students with single

sound articulation differences from special

Shift to General education to general education

Education

Offer students with single sound articulation

differences intensive short term high quality

services within general education

Provide intensive professional development and

support to district SLPs

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

1

Single Sound Cases Over Time Critical Reform Features

SSADD = Single Sound Artic. Differences and Disorders

Staskowski, M., & Rivera, E. (2005)

Well-

Well-organized set of procedures

Prioritizing time for SLPs

Buy-

Buy-In from Administration, Staff & Community

Proposal: Benefits and Phase-

Phase-In Implementation Plan

Meetings and workshops with stakeholders

Adherence to Special Education Eligibility Criteria

Articulation Resource Center & Articulation

Differences and Disorders Manual (and many

other resources)

Speech Improvement Class at Every Site

(gradually implemented)

Articulation Differences

Eligibility Requirements & Disorders Manual

In California Ed Code, student must meet ALL (Dunaway, 2004)

three criteria to qualify for IEP services: http://csha.org/ResourceCenter/resourcecentermain.htm

(or csha.org Æ Resource Center Æ San Diego City Schools Manual)

Significantly interferes with communication

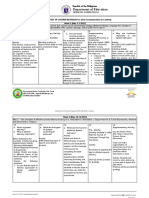

Overview of Service Delivery Approaches

AND Performance-

Performance-Based Assessment Procedures

Screening, Full Assessment, IEP, 504

Attracts adverse attention

Protocols, Checklists, Rating Scales

AND

Sample Report – section at beginning with IEP criteria

Speech Improvement Class

Adversely affects educational performance Description, Permission and Record Forms, Inventories

Intervention Approaches

SLP Benefits Student Benefits

Gradual implementation of SI class Access to high quality services

More technical support

Increased ability to manage workload Accurate diagnosis/identification

More latitude to decide who needs help & when Less treatment time

Programs allocates .5 day a week for Speech

Improvement: Counts 5 students toward Flexible scheduling

caseload total

Flexible scheduling Increased practice in classroom and

Wait list at home

Less paperwork

Introduce RTI to sites

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

2

ARC Coordinator

Innovation 2 – Two-

Two-day assignment

The Articulation Works from central location

Opportunities to educate, consult,

Resource Center model and coach

Service to staff not to individual

students

Cost-

Cost-effective

The ARC Provides... The ARC Provides...

Consultation (visits, e-

e-mails, phone calls) about Resources for and information about the

students with phonological or articulation needs Speech Improvement Class

Current research in assessment and intervention Library of resources, including research

ARC News articles, current phonological textbooks

Opportunity for observation and some materials

Therapy materials created for specific methods Handouts on placement techniques,

Workshops regarding current techniques for randomized treatment, ways to generate

SLPs and SLPAs mass practice

Speech Differences

Speech Neutral term that refers to sound

production that does not match Standard

Differences and American English

Developmental

Disorders

Dialect

Second language acquisition

Idiosyncratic (mild distortion)

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

3

Speech Deficit or Disorder

Atypical sound production that may

or may not Response to

affect

communication

drawadverse attention Intervention

impact educational performance

Phonological disorder, childhood

apraxia of speech or articulation

deficit

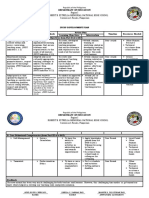

Tiers of Intervention Tier I Intervention

for Single Sounds

Layers of intervention

responding to student

TIER I: Core

needs Developmental information shared with

Each tier provides more

intense intervention teachers and parents (Tier I power point)

Aimed at preventing Teachers determine stimulability (given

TIER II: reading difficulties

Supplemental coaching)

TIER Teacher and family provide extra models

for target sounds & monitor progress

adapted from Vaughn, 2003, RtI Symposium

III

Intensive

Tier I Intervention Tier I Intervention -

for Single Sounds Recasts (Camarata, 1993)

Consistent visual cue given to child across “A critical element of naturalistic

environments (e.g., /s/ - running finger conversation training is that the clinician

down the arm) (Miccio & Elbert, 1996) maintains the integrity of the interaction

while providing the model.”

model.”

More time to respond

Conclusion: kids with sound errors may

If you cannot understand what the child require more relevant models of correct

says, say “I need help. Please help me productions than other children

understand…”

understand…” (take the communicative Other research bears this out –

burden off of the child) grammatical recasts, etc.

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

4

Tier II Intervention

for Single Sounds Who is the

Speech Improvement Class – twice a week for

Speech

30 minutes (intensive treatment)

Child given sufficient time for development

Ideally, extra services provided if sound not

acquired by age 7-7-7 ½

Improvement

Most treatment complete in 20 hours or fewer

Progress monitoring through conversation

Class for?

samples and Speech Improvement Sound

Inventory – samples target sounds in isolation,

words (singletons and clusters), sentences

Sound Acquisition Normative Data

A social interactive process that isn’

isn’t Unreliable

complete for some children until the age 8 Depends on the sample population

years, 5 months (speech normalization Children develop their sound repertoires

boundary – Shriberg et al, 1994) individually

Speech normalization boundary metric for Can provide general information about

SDUSD Speech Improvement Class sound development

Each child follows a unique developmental

timetable

Smit et al (1990) &

Smit (1993) Other

New data for Iowa and Nebraska

Cautioned against strict use of norms to

Considerations

guide treatment

New data about typical vs. atypical error Typical or atypical patterns

patterns Dialectical pattern

Stimulable or nonstimulable sound

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

5

English Learner or

Atypical Patterns

Dialectical Patterns

Lateral /s/ and /z/ (and other sounds)

production not developmental (intervene Determine if difference is due to first

at any time) (Smit, 1993a) language pattern or dialect

Consider other atypical patterns e.g., child who speaks Spanish says [tʃ

[tʃ] for

/ʃ/

Treat atypical patterns first

e.g., child who speaks African-

African-American

English says [f] for /θ

/θ/

Ideal Candidates for

Stimulability the SI Class

Stimulability for target sound 2nd or 3rd grade (ideally around age 7 - leaves

Research suggests that children who are 1.5 years before the speech normalization

stimulable for target sounds will acquire boundary) (except for lateralized productions)

them without intervention (Gierut, 2007) One sound/cognate (or two sounds)

Monitor children in K and 1st grade – Three IEP criteria not met - intelligibility,

intervention may not be warranted if child adverse attention AND educational impact

is stimulable Nonstimulable for target sounds (monitor kids

who are stimulable)

Motivated and willing to practice at home

SI Classes At Every Site Routes to Speech

Open to any grade level if the student is

motivated and will complete homework Improvement

May take a little longer at middle and high

Class &

school levels (past the speech

normalization boundary)

Procedures

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

6

1.Child Has Existing IEP –

Existing IEP Æ SIC

Student has IEP (from any district) Speech Improvement or

1. IEP Æ Dismiss from IEP Æ Consider Waitlist More Appropriate

SIC (often residual errors)

Ask teacher to complete Describing Speech

Misarticulations prior to meeting

Review progress at the annual IEP

If three criteria not met, consider dismissal

(following performance-

performance-based assessment)

Students may enroll in SIC

2. Child Has Existing IEP –

Existing IEP Æ IEP Stays on IEP (rare)

2. IEP Æ (Rarely) Keep on IEP

If only 30 minutes per week on IEP, consider

adding additional 30 minutes to accelerate

intervention

SLPs can do this in one of two ways:

1. Convene IEP to add 30 minutes (60 min/wk)

2. Add 30 minutes as a general education

service (30 minutes on IEP, 30 minutes SIC)

3. New Consultation –

New Student SIC or Waitlist

3. New student

Enroll in SI class

Teacher completes Describing Speech

Misarticulations

If three criteria not met and good

candidate for SI class, enroll in class

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

7

Procedures for SI Class Procedures for Completion

After parents sign and return, work with Document attendance and homework

teacher to schedule class time completion (on back of sound inventory)

Administer Speech Improvement Sound Readminister Speech Improvement Sound

Inventory for target sound prior class for Inventory to compare with baseline

baseline Conversation sample

Provide daily home practice opportunities Researchers have suggested 80% accuracy

Periodically check on progress and in conversation adequate for dismissal

communicate with parents and teacher Award Certificate of Completion

Continuation of Services Other Odds & Ends

With proper techniques, most kids will fully Students not billed for MediCal

acquire and generalize the sound in ~20 hours

SLPs can mix students with and

Services can carry over to next school year without IEPs in a Speech

SLP’

SLP’s discretion about whether to continue for Improvement Class

others beyond 20 hours

Funding source – 15% of IDEA funds

Students past speech normalization boundary

may take longer for early intervening services

71 students randomly selected – 76% finished SLPAs can implement class with

in 17 hours or fewer, other 24% required 25-

25-30 training

hours

File Contents Innovation 3 –

Signed Permission to Enroll

Describing Speech Misarticulations Form

Evidence-Based

Entry/Completion Form/Attendance

Speech Improvement Sound Inventory

Intervention

(before and after class) •Complexity Approaches (Phonemic)

Homework Contract/Documentation of

homework completion •Motor Learning Approach (Phonetic)

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

8

A. Lynn Williams: Complexity

“Regardless of the placement on the

phonetic-

phonetic-phonemic continuum, children Approach

with speech disorders require aspects of

each in remediating their sound (What to Teach)

disorders.”

disorders.”

Language

Laws

Clusters

Phonemic Targets

Complexity Approach

Principles (Phonemic)

Language Laws

Universals - implicational relationships

Guided by language laws and sound found across languages

features Laws can be used to guide treatment

Some laws applicable to SIC students

Treatment targets sounds - nonstimulable, Treating marked structures creates change

phonetically-

phonetically-complex and later-

later-developing in unmarked structures (Marked implies

unmarked)

Results in generalization to untreated

sounds and contexts

Phonemic Inventory Laws Phonemic Laws

Velars Æ Coronals (Stoel-

(Stoel-Gammon, 1996) Affricates Æ Fricatives (Gierut, 1990)

Teach affricates to create change in the

system

Fricatives Æ Stops (Dinnsen & Elbert, 1984)

Liquids Æ Nasals (Tyler & Figurski, 1994)

Voiced obstruents Æ Voiceless obstruents

(McReynolds & Jetzke, 1986)

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

9

Distributional Laws

Stops in final position Æ Stops in initial

position (Rockman, 1983)

Clusters

Fricatives in initial position Æ Fricatives

in final position (Smith, 1973)

Syllable Structure Laws Syllable Structure Laws

Clusters Æ Singletons (Gallagher & Shriner, 1975) 3- element clusters Æ 2-element /s/ and non /s/

clusters (Gierut & Champion, 2001)*

Clusters Æ Affricates (Gierut & O’

O’Connor, 2002) 3-element clusters typically last sequences to be

acquired; therefore, complex targets

Fricative + Liquid Clusters Æ Stop + Liquid Clusters

(Elbert et al, 1984) *Caveat: 3-

3-element clusters impact both cluster

types and promote system-

system-wide change;

however, results significant only if consonant 2

Liquid-

Liquid-onset Clusters Æ Liquids in Coda Position and consonant 3 already in system (i.e. teach

/skr/ only if /k/ and /r/ already in inventory)

(Baertsch, 2002; Fikkert, 1994)

Clusters Probe

Independent probe (Taps, 2005)

Each cluster targeted 2-

2-3 times

Untreated words to measure progress

May need to provide cues to elicit target

words

Some pictures include more than one

target word (e.g. “spider”

spider” and “smile”

smile” for

the same picture)

Identify which clusters are in the system

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

10

Other Complex

Adjunct Clusters

Clusters

/sp/, /sk/, /st/

Refer to handout – Sonority Sequencing

SSP does not apply (Perhaps due to

Principle for Clusters

difference of -2)

Clusters from most complex (sm-(sm-, sn-

sn-) to least

Treating these may inhibit generalization

complex (tw-

(tw-, kw-

kw-)

to other clusters

If several clusters missing from repertoire,

Led to overgeneralization of /s/ onset

treat more complex clusters to create change

clusters

Ideally, three-

three-element clusters or other

complex clusters (if consonant 2 and

consonant 3 not in phonetic inventory)

Phonological and

Lexical Learning

Phonemic Targets Research positing interaction

between the two

Complex interaction between

Real or Nonsense phonology and lexicon

Words?

New area of focus

High Frequency vs.

Real Words Low Frequency Words

Current research suggests (see Morrisette & Gierut

(2005) and Storkel & Morrisette (2002)): High-

High-frequency words impacted treated

High-

High-frequency words have greater impact than sounds

treating low-

low-frequency words (treating real, Also within and across class generalization

common words)

Frequency – number of occurrences of given

word in a language (Morrisette, 1999) Æ high-

high- Low frequency words generalized across

frequency words recognized faster and are class only

therefore more resistant to slips of the tongue

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

11

Neighborhood Density Low Density vs.

Neighborhood density – number of High Density Words

phonetically similar counterparts that

Both types of words yield change in child’

child’s

exist for a word based on one system

substitution, one deletion or addition

Choose words balanced in density (i.e. five

E.g. “feet”

feet” – fleet, meet, fee, eat, fit, high density and five low density)

fate, fete, etc. – 10

neighbors/counterparts

high-

high-density Æ 11 or more neighbors

low-

low-density Æ 10 or fewer neighbors

Combining Principles Web site

of High Frequency and http://128.252.27.56/Neighborhood/Home.asp

Density (Storkel, 2004) Identifies targets based on frequency and

density

Low-

Low-density High-

High-density Washington University in St. Louis

/r/ words /r/ words

“radio”

radio” “run”

run” Handout with high frequency words available

“read”

read” on web site – http://slpath.com

“river”

river”

Nonsense Words

Frequently utilized because these words are novel

and therefore not “frozen”

frozen” in a child’

child’s system

Motor Learning

May break into old pattern

Nonsense word stories give nonsense words a

Strategies

(How to Teach It)

sense of meaning (therefore phonemic value)

Nonsense words – character names and places

Can use nonsense words at different levels (single

words, conversation, story telling) •Three phases of motor learning

Picturable •Randomization

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

12

Traditional Approach vs.

Specificity of Learning Motor Learning Approach

“Specificity of learning”

learning” stipulates that the Both acknowledge different levels of

“most closely related movement/activity difficulty

creates most improvement in overall skill”

skill” Traditional – gradually gets more difficult

(Skelton, 2004) Æ 80% at the sound level, 80% at the

Practice connected, meaningful speech for syllable level, 80% at the word level, etc.

the most effective approach Motor learning – once sound established

Oral-

Oral-motor exercises less related and do in isolation/syllables Æ mix up levels

not create improvement in overall speech (move between various levels in given

intelligibility session)

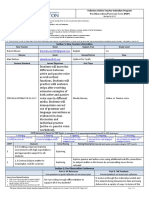

Traditional Motor Learning Motor Learning Skill

conversation

Acquisition - Three

sentences

syllables

sentences

phrases

Phases (Phonetic)

(Skelton, 2004)

stories

words

sounds

phrases words

1. Pre-

Pre-practice/placement

stories

sentences

sounds

phrases

words syllables

2. Practice

syllables

Sound 80% accuracy in 3. Generalization

isolation and syllables

isolation

Motor Learning Skill Pre-Practice/Placement

Acquisition – Phase I Strategies

(Skelton, 2004)

What works for one child may not for

Pre-practice: Brief

1. Pre- another

placement/production phase (OK to

return to this phase at any time) Many SLPs not trained in this area

Teach target sound in isolation and Critical to have a variety of resources

syllables until 80% accurate Bauman-

Bauman-Waengler chapter

May need to teach new strategies or

Dr. Bleile’

Bleile’s book: Late Eight (Plural)

make phonetic adjustments in how

student produces the sound(s) Dr. Secord’

Secord’s book: Eliciting Sounds (rev.)

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

13

Five Placement

Techniques

(Flipsen, 2002)

Imitation - visual or verbal cue

Shaping - shape from one sound to another (also

called sound modification)

Phonetic placement - describe how to make sound

by talking about articulators or through metaphors

Moto-

Moto-kinesthetic - stimulating sounds through use

of tongue depressors, etc.

Touch cues (e.g., PROMPT)

Motor Learning Skill Blocked vs. Random Practice

Acquisition – Phase II (Skelton, 2004)

(Skelton, 2004) Blocked practice (all practice

items of target stimulus practiced

2. Practice: Randomized variable

sequence of tasks together before moving on) Æ

Schema theory predicts greater transfer Better performance in given

and retention because “rules”

rules” are flexible sessions

Student practices at different levels or Randomized practice Æ Better

different numbers during each session

(more than one context - not “fixed”

fixed” at a

retention/motor learning

particular level as in traditional treatment)

Motor Learning Skill

Acquisition – Phase III

(Skelton, 2004)

3. Generalization: Practice skills in more Letting kids be kids

representative contexts of communication

Provides natural consequences of

performance, including a listener’

listener’s

reaction

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

14

Randomization Can Be Randomization Can

Accomplished By: Be Accomplished By:

Switching levels (words, Changing body position

sentences, conversation) (different actions) – standing,

sitting, jumping jacks, etc.

Switching the order of target

Self-monitoring while doing a

words

million things (as kids do)

Switching number of

Have kids brainstorm ideas

responses

Video

Randomization Can Be

Accomplished By Changing:

Stress

Feedback That

Intonation Fosters

Prosody

Rate of speech

Self-Monitoring

Emotional context - Video

Have kids brainstorm ideas

Delayed Feedback Kind of Feedback/Praise

Offer delayed feedback by waiting 5 seconds Praise that is nonspecific (“

(“Good job,”

job,”

More feedback during the pre-

pre-practice stage “Excellent”

Excellent”) can be viewed as insincere

than practice (the more specific to the process, Praise can undermine a child’

child’s self-

self-

the better) monitoring and self-

self-correction skills

Provides opportunity for child to assemble and (Donahue et al, 2004)

retrieve motor plans (Yorkston et al, 1999) Some children become so dependent on

Offers child more self-

self-monitoring opportunities praise that they lose ability to evaluate

own performance and fail to take pleasure

in own success (Burnett, 1991; Good, 1987)

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

15

Generalization Generalization

Koegel, Koegel, Voy & Ingram (1988) Koegel, Koegel, Voy & Ingram (1988)

Evaluated necessary conditions for Increased self-

self-monitoring led to

generalization to occur accuracy of production in all situations

Children taught self-

self-monitoring skills % of correct responses within clinic

within clinic (children become own unrelated to generalization

clinicians) Accuracy of self-

self-monitoring unrelated

Monitored own productions on wrist to generalization (kids who self-

self-

counters outside of clinic monitor correctly even intermittently

generalize)

Constructivist

Self-Monitoring

Strategies

Rating productions each day while talking

with family for five minutes (fridge log)

(Ertmer & Ertmer, 1998)

Encouraged child to employ metacognitive

Speech diary strategies (similar to those children who

Buzzing watches easily carried over learning)

Score caddy counters Ideas: child is the “leader”

leader” in authentic

www.outabounds.com/golf-

www.outabounds.com/golf-score-

score- situations to practice speech

counters-

counters-caddy-

caddy-golf-

golf-score-

score-counter.htm Student reflection during all aspects of the

Knitting counters process

Ways to Elicit

Mass Practice

Mass Practice Use tally counters to challenge students for

multiple productions (Go to

www.tallycounterstore.com)

www.tallycounterstore.com)

Have students subvocalize (“(“voices turned

off”

off”) during other students’

students’ turns to increase

the motor practice and number of practice

opportunities (may have to monitor initially)

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

16

Ways to Elicit Ways to Elicit

Mass Practice Mass Practice

Manipulatives can be used for random activities

Students track their totals using counters E.g., counting bears of various colors and

Add up group total and have contests numbers (perhaps 25 total)

across groups to see who produces the most First turn: put all yellow bears in cup while

Multiply the group total by the number of saying the practice items

students if subvocalizing Next turn: all the blue bears

E.g.: Group total (710) X students in group Ensures randomized practice by doing

(4) = 2,840 items for a 30 min. group something different each turn

Centers

Centers Create centers like those in general

education

Students do something different every

(Taps, 2005) minute or so while practicing sounds

Three centers could include the following:

1. one child at the board saying words

2. one child telling SLP a story

3. one child lying on the floor while

practicing sentence

Centers

Encourages students to use good

sounds in variety of contexts and to

become own clinicians Activities

Say “switch”

switch” at random times for

them to move to a new station

Write the sequence for kids to follow,

such as

board Æ SLP Æ floor Æ board

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

17

Meaningful Contexts

(Hoffman & Norris, 2005) Treat Like Fluency

Provide multiple opportunities to produce Multiple, meaningful contexts

words in a range of simple to complex contexts Speech room

(repetitive modeling, redundancy, immediate Classroom

recasting all facilitate generalization) Playground

Intervention independent of communication Media center

(i.e. drill only) Æ child defaults to old motor Phone calls

pattern of speech used in communicative Front office

situation (generalization may take years) Recess

Sample Activities More Activities

Barrier games Role playing

Shopping for items with target Puppet shows

sounds Operator

Hide and seek Old way/New way

Guessing targets Guess Who

Retelling stories Fishing pond

What’

What’s in Ned’

Ned’s head?

Home Practice – A

Innovation 4 – Critical Component

Required Home General education Æ can require homework

ASHA NOMS – children who practiced at

Practice

home significantly more likely to generalize

than children who did not

Letter provided to SLPs to send to families

about the importance of home practice

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

18

Child with Limited

Homework Policy

Home Support

Initial letter home

SLP can arrange something creative for

extra practice in another environment

One homework assignment not

(speech buddy in class, practice in library

completed – courtesy call home

(explain policy again) during recess, etc.)

Second homework assignment – Something that promotes thinking and

move to next child on wait list practice outside of the speech room

(enough to motivate most families)

Home Practice Options

ARC open to SLPs and visitors by

Applying the

appointment for treatment materials

(homework practice sheets organized by

Four Innovations

target sound available)

Make sure that homework consistent with in Your District

practice during sessions (do not switch to

blocked practice if randomizing)

May need to modify existing sheets – ask

the kids for ideas

Four Innovations –

What You Can Do

1. Shift to General Education Services Æ

Implement process over time

THANK

2.

3.

Articulation Resource Center Æ Develop

a support within your district

Research-

Research-Based Methods Æ Apply in

YOU!

treatment jtaps@sandi.net

4. Home Practice Æ Require it to facilitate Resources available at

generalization http://slpath.com

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

19

Best Practices

for SI Class

Summary of Consider whether or not differences are

developmental or dialect

Best Practices

Treat lateral /s/ and /z/ as soon as possible

Treat around ages 7/7 ½ (time before speech

normalization boundary)

Intensity of service critical

Treat nonstimulable sounds

Use three stages of motor learning – pre-

pre-

practice, practice and generalization

Best Practices Best Practices

for SI Class for SI Class

Treat real words (high-

(high-frequency/low-

frequency/low-

density) Randomized tasks

Lots of opportunities in natural

communication

Conversational recasts

Delayed, occasional feedback (but specific

to problem-

problem-solving or effort)

Build self-

self-monitoring from beginning

Home practice

Data from SLPs for Single Sound

Students (July 04, July 05, November

05, June 06, July 07, October 07)

Further July 2004

Sample size 178

Evidence

Total SSADD cases w/IEP 821

Total SSADD cases w/o IEP 0

July 2005

Sample size 159/203 (78% response rate)

Total SSADD cases w/IEP 560

Total SSADD cases w/out IEP 322

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

20

Data from SLPs for Single Sound Data from SLPs for Single Sound

Students (July 04, July 05, November Students (July 04, July 05, November

05, June 06, July 07, October 07) 05, June 06, July 07, October 07)

November 2005 July 2007

Sample size 199/207 (96% response rate) Sample size 199/207 (92% response rate)

Total SSADD cases w/IEP 147 Total SSADD cases w/IEP data unavailable

Total SSADD cases w/out IEP 273 Total SSADD cases w/out IEP 569

June 2006 October 2007

Sample size 195/223 (88% response rate) Sample size 240/255 (94% response rate)

Total SSADD cases w/IEP 46 Total SSADD cases w/IEP 95

Total SSADD cases w/out IEP 415 Total SSADD cases w/out IEP 470

Matched Pairs Analysis Matched Pairs Analysis

July 04, July 05, November 05, July 04, July 05, November 05,

June 06, October 2007 June 06, October 2007

July 2004 Nov 2005

Total cases SSADD w/IEP 101

Total cases SSADD w/IEP 573

Average # per SLP 1.3

Average # per SLP 7.2

Total cases SSADD w/o IEP 162

July 2005 Average # per SLP 2.0

Total cases SSADD w/IEP 395

June 2006

Average # per SLP 4.9

Total cases SSADD w/IEP 32

Average # per SLP 0.4

Total cases SSADD w/o IEP 208

Average # per SLP 2.6 Total cases SSADD w/o IEP 225

Average # per SLP 3.4

Matched Pairs Analysis

Matched Pairs Average Over Time

July 04, July 05, November 05,

June 06, October 2007

October 2007

Total cases SSADD w/IEP 25

Average # per SLP 0.5

Total cases SSADD w/o IEP 156

Average # per SLP 2.8

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

21

Bibliography Bibliography

American Speech-

Speech-Language Hearing Association (n.d.) National Bauman-

Bauman-Waengler, J. (2004). Articulatory and phonological

Outcome Measurement System. Retrieved August 1, 2004, from impairments: A clinical focus. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn &

http://www.asha.org/members/research/NOMS/noms_data.htm Bacon.

Baertsch, K. (2002). An optimality theoretic approach to syllable

syllable Bernthal, J. & Bankson, N. (2003). Articulation and Phonological

structure: The split margin hierarchy. Unpublished doctoral Disorders. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington. Bleile, K. (2004). Manual of Articulation and Phonological Disorders.

Barlow, J. (2004). Consonant clusters in phonological acquisition:

acquisition: San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group.

Applications to assessment and treatment. CSHA Magazine, Bleile, K. (2005). Late Eight. San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

Summer, 10-10-12. Camarata, S. (1993). The application of naturalistic conversation

conversation

Barlow, J. (2001). Recent advances in phonological theory and training to speech production in children with speech disabilities.

disabilities.

treatment. Language, Speech, and Hearing in the Schools, 32 (3), Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 26(2):173–

26(2):173–182.

295 – 297. Crowe-

Crowe-Hall, B. (1991). Attitudes of fourth and sixth graders toward

peers with mild articulation disorders. Language, Speech, and

Barlow, J. A. (2001). The structure of /s/ sequences: Evidence from a Hearing Services in Schools, 22, 334-

334-340.

disordered system. Journal of Child Language,

Language, 28,

28, 291-

291-324.

Dinnsen, D. A., & O'Connor, K. M. (2001). Implicationally related

related error

Barlow, J. A., & Gierut, J. A. (2002). Minimal pair approaches toto patterns and the selection of treatment targets. Language, Speech

phonological remediation. Seminars in Speech and Language,

Language, 23,

23, Schools, 32,

and Hearing Services in Schools, 32, 257-

257-270.

57-

57-68.

Bibliography Bibliography

Dinnsen, D. A., & O’

O’Connor, K. M. (2001). Typological predictions in Elbert, M., Dinnsen, D. A., & Powell, T. W. (1984). On the prediction

prediction of

developmental phonology. Journal of Child Language,

Language, 28,

28, 597-

597-618. phonologic generalization learning patterns. Journal of Speech and

Dinnsen, D.A., Chin, S.B., Elbert, M. & Powell, T.W. (1990). Some

Some Disorders, 49,

Hearing Disorders, 49, 309–

309–317.

constraints on functionally disordered phonologies. Journal of Ertmer, D. J., & Ertmer, P. A. (1998). Constructivist strategies

strategies in

Speech and Hearing Research, 33, 33, 28-

28-37. phonological intervention: Facilitating self-

self-regulation for carryover.

Dinnsen, D. & Elbert, M. (1984). On the relationship between Schools, 29,

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 29, 67-

67-75.

phonology and learning. In M. Elbert, D. Dinnsen & G. Weismer Fikkert, P. (1994). On the acquisition of prosodic structure. Dordrecht,

Dordrecht,

(Eds.), Phonological theory and the misarticulating child (ASHA the Netherlands: ICG.

Monographs, No. 22) (p. 5 -17) Rockville, MD: ASHA. Flipsen, P. (2002). http://web.utk.edu/~pflipsen/555-

http://web.utk.edu/~pflipsen/555-therapy.PDF

Dunaway, C. (2004). Articulation differences and disorders manual. Gallagher, R. & Shriner, T. (1975). Contextual variables related

related to

San Diego: San Diego City Schools Office of Instructional Support.

Support. inconsistent /s/ and /z/ productions in the spontaneous speech of of

Dweck, C. (1999). Self theories: Their role in motivation, personality children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Association Research, 18,

development. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

and development. 623 – 633.

Dyson, A.T. & Robinson, T.W. (1987). The effect of phonological Gierut, J.A. (2007). Phonological complexity and language learnability.

learnability.

analysis procedure on the selection of potential remediation targets.

targets. Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 6 – 17.

American Journal of Speech-

Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 18, 364-364-377. Gierut, J.A. (2004). Clinical application of phonological complexity.

complexity.

Elbert, M. & Gierut, J. (1986). Handbook of Clinical Phonology: CSHA Magazine, Summer, 7- 7-8.

Treatment. Boston: College-

Approaches to Assessment and Treatment. College-Hill

Press.

Bibliography Bibliography

Gierut, J. A. (2001). Complexity in phonological treatment: Clinical

Clinical Gierut, J.A. & Morrisette, M. (2005). The clinical significance of

factors. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools,

Schools, 32,

32, optimality theory for phonological disorders. Topics in Language

229-

229-241. Disorders. Clinical Perspectives on Speech Sound Disorders.

25(3):266 - 280.

25(3):266

Gierut, J.A. (1999). Syllable onsets: Clusters and adjuncts in

acquisition. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Gierut, J.A., Elbert, M., & Dinnsen, D.A. (1987). A functional analysis

Research, 42, 708 - 726. of phonological knowledge and generalization learning in

misarticulating children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research,

Gierut, J.A. (1998). Treatment efficacy: Functional phonological

phonological 30, 462-479.

disorders in children. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing

Research, 41, S85 – S100. Gierut, J.A. (1989). Maximal opposition approach to phonological

treatment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 51, 324-336.

Gierut, J.A. (1990). Differential learning of phonological

oppositions. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 33, 540- 540- Glaspey, A. & Stoel-Gammon, C. (2005). Dynamic assessment in

549. phonological disorders. Topics in Language Disorders. Clinical

Perspectives on Speech Sound Disorders. 25(3):220 - 230.

Gierut, J. A., & O’

O’Connor, K. M. (2002). Precursors to onset clusters

in acquisition. Journal of Child Language,

Language, 29,

29, 495–

495–517. Green, J., Moore, M., Higashikawa, M., & Steeve, R. (2000). The

physiologic development of speechmotor control: Lip and jaw

Gierut, J.A. & Champion, A.H. (2001). Syllable onsets II: Three

Three- coordination. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing

element clusters in phonological treatment. Journal of Speech, Research, 43, 239–256.

Language and Hearing Research, 44, 886 -904.

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

22

Bibliography Bibliography

Jacoby, G., Lee, L., Kummer, A.W., Levin, L., Creaghead, N. (2002). The number Masterson, J. & Apel, K. (2006). Optimal Phonology Assessment: Making

of individual treatment units necessary to facilitate functional communication Sound Decisions. National CEU, Portland.

improvements in the speech and language of young children. American

Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 370-380. Masterson, J., Bernhardt, B., & Hofheinz, M. (2005). A comparison

comparison of

Kamhi, A.G. & Pollock, K.E. (Eds.) (2005). Phonological Disorders in Children.

single word and conversational speech in phonological evaluation.

evaluation.

Baltimore: Brookes Publishing Co. American Journal of Speech-

Speech-Language Pathology, 14 (3), (3), 229 – 241.

Kamhi, A. G. (2006). Treatment decisions for children with speech-sound McReynolds, L. & Jetzke, E. (1986). Articulation generalization

generalization of voiced-

voiced-

disorders. Language, Speech & Hearing in Schools, 37, 280 – 283. voiceless sounds in hearing-

hearing-impaired children. Journal of Speech and

Kamhi, A. G. (2000). Practice makes perfect: The incompatibility of practicing Hearing Disorders, 51, 348 – 355.

speech and meaningful communication. Language, Speech, and Hearing Miccio, A. W. & Elbert, M. (1996). Enhancing stimulability: A treatment

Schools, 31,

Services in Schools, 31, 182–

182–186. program. Journal of Communication Disorders: Clinics Issue, 29,

Kehoe, M.M. (2001). Prosodic patterns in children’

children’s multisyllabic word 335 - 351.

productions. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 32, 32, 284-

284- Miccio, A. W., Elbert, M., & Forrest, K. (1999). The relationship

295. relationship between

stimulability and phonological acquisition in children with normally

normally

Kollia, B. & Eisenberg, S. (2005, November). Children’

Children’s performance on five tests developing and disordered phonologies. American Journal of Speech-Speech-

of articulation and phonology. Poster presented at the American Speech-

Speech-

Language Hearing Association Convention, San Diego, CA. Pathology, 8, 347-

Language Pathology, 347-363.

Lof, G. (2006). Logic, Theory and Evidence Against the Use of Oral Motor Morrisette, M. L., & Gierut, J. A. (2002). Lexical organization and

Productions. Paper presented at the

Exercises to Change Speech Sound Productions. phonological change in treatment. Journal of Speech, Language and

American Speech-

Speech-Language Hearing Association Convention, Miami, FL. Research, 45,

Hearing Research, 45, 143-

143-159.

Bibliography Bibliography

Morrisette, M. L. (1999). Lexical characteristics of sound change. Clinical Rvachew, S. (2005). Stimulability and treatment success. Topics in Language

13, 219–

Linguistics & Phonetics, 13, 219–238. Disorders. Clinical Perspectives on Speech Sound Disorders. 25(3): 207 - 219.

25(3):207

Munson, B., Edwards, J. & Beckman, M.E. (2005). Phonological knowledge in Secord, W. (2007). Eliciting Sounds. Florence, KY: Thomson Delmar Learning.

typical and atypical speech-

speech-sound development. Topics in Language

Disorders. Clinical Perspectives on Speech Sound Disorders. 25(3): 190--206.

25(3):190 Shriberg, L. D., Gruber, F. A., & Kwiatkowski, J. (1994). Developmental

Developmental phonological

disorders III: Long-

Long-term speech-

speech-sound normalization. Journal of Speech and

Powell, T. W., Elbert, M. and Dinnsen, D.A. (1991) Stimulability

Stimulability as a factor in the Research, 37,

Hearing Research, 37, 1151–

1151–1177.

phonological generalization of misarticulating preschool children.

children. Journal of

Speech and Hearing Research, 34, 1318-

1318-28. Shriberg, L., & Kwiatkowski, J. (1982). Phonological disorders II:

II: A conceptual

framework for management. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders,

Disorders, 47,

47, 242–

242–

Ristuccia, C. (2000). Entire World of R. Tybee Island, GA: Say It Right. 256.

Ristuccia, C. (2004). Entire World of S & Z. Tybee Island, GA: Say It Right.

Skelton, S. & Kerber, J.R. (2005, November). Using concurrent treatment

treatment to teach

Ristuccia, C. (2004). Entire World of Sh and Ch. Tybee Island, GA: Say It Right . multiple phonemes to phonologically-

phonologically-disordered children. Poster presented at the

Ristuccia, C. & Ristuccia, J. (2006). The Entire World of R Book of Elicitation American Speech-

Speech-Language Hearing Association Convention, San Diego, CA.

Techniques. Tybee Island, GA: Say It Right. Skelton, S. (2004). Motor-

Motor-skill learning approach to the treatment of speech-

speech-sound

Rockman, B. (1983). An experimental investigation of generalization and disorders. CSHA Magazine, Summer, 8- 8-9.

individual differences in phonological training. Unpublished doctoral Skelton, S. (2004). Concurrent task sequencing in single-

single-phoneme phonologic

dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington. treatment and generalization. Journal of Communication Disorders, 37, 131 –

155.

Bibliography Bibliography

Smit, A. (1993a). Phonologic error distributions in the Iowa-

Iowa-Nebraska Storkel, H. L., Hoover, J. R., & Young, J. M. (2004). Evidence-

Evidence-Based

articulation norms project: consonant singletons. Journal of Speech and Practice in Treatment of Preschool Children with Speech Delays:

Hearing Research, 36 (3), 533 – 547. What is the Evidence? [Handout]. Lawrence, Kansas: University of

Smit, A. (1993b). Phonologic error distributions in the Iowa-

Iowa-Nebraska Kansas.

articulation norms project: word-

word-initial consonant clusters. Journal of

Speech and Hearing Research, 36 (5), 931 - 947. Storkel H.L. & Morrisette, M. L. (2002). The lexicon and phonology:

phonology:

Smith, N. (1973). The Acquisition of Phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge

Interactions in language acquisition. Language, Speech and

University Press. Hearing Sciences in Schools, 33, 24 – 37.

Staskowski, M., & Rivera, E. (2005). Speech–

Speech–language pathologists’

pathologists’ Strand, E. & Kent, R. (2005). Treatment of Motor Speech Disorders

Disorders in

involvement in responsiveness to intervention activities: A complement

complement to Children: Dilemmas and Solutions. Presentation at the American

curriculum-

curriculum-relevant practice. Topics in Language Disorders, 25(2),

25(2), 132–

132– Speech-

Speech-Language Hearing Association Convention, San Diego, CA.

147. Taps, J. L. (2005). Randomized Principles and Practice. [Handout].

[Handout].

Steriade, D. (1990). Greek prosodies and the nature of syllabification.

syllabification. New San Diego, CA: San Diego Unified School District.

York: Garland Press.

Taps, J. L. (2005). Clusters Probe. [Handout]. San Diego, CA: San

Stoel-

Stoel-Gammon, C. (1996). On the acquisition of velars in English. In B.

B. Diego Unified School District.

Bernhardt, J. Gilbert, & D. Ingram ( Eds.), Proceedings of the UBC

UBC

International Conference on Phonological Acquisition ( pp. 201–

201–214). Tyler, A. A. and Figurski, G. R. (1994). Phonetic inventory changes

changes after

Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press. treating distinctions along an implicational hierarchy. Clinical

Phonetics, 8, 91-

Linguistics & Phonetics, 91-107.

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

23

Bibliography

Weston, A., & Bain, B. (2003, November). Current v. evidenced-

evidenced-based

practice in phonological intervention: A dilemma. Poster session

presented at the Annual Convention of the American Speech-

Speech-

Language-

Language-Hearing Association, Chicago.

Williams, A. (2005). From developmental norms to distance metrics:

metrics:

Past, present, and future directions for target selection practices.

practices. In

A. Kamhi & K. Pollock ( Eds.), Phonological disorders in children:

children:

Clinical decision making in assessment and intervention (pp. 101–101–

108). Baltimore: Brookes.

Williams, A.L. (2005). Assessment, target Selection and intervention.

intervention.

Topics in Language Disorders. Clinical Perspectives on Speech

25(3):207 - 219.

Sound Disorders. 25(3):207

Yorkston, K.M., Beukelman, D.R., Strand, E.A. & Bell, K.R. (1999).

(1999).

Management of Motor Speech Disorders in Children and Adults.

Austin, TX: Pro-

Pro-Ed.

Taps, San Diego Unified School District ASHA 2007

24

You might also like

- Medaille New Lesson Plan 3 Sheila HolmesDocument10 pagesMedaille New Lesson Plan 3 Sheila Holmesapi-418734224No ratings yet

- MFDM™ AiDocument48 pagesMFDM™ AiAyusman Panda50% (4)

- Flexible Instruction Delivery Plan (FIDP) : Quarter: Performance StandardDocument9 pagesFlexible Instruction Delivery Plan (FIDP) : Quarter: Performance StandardWeng Baymac II75% (8)

- Martin Mcquillan-Post Theory New Directions in Criticism-Edinburgh University Press PDFDocument188 pagesMartin Mcquillan-Post Theory New Directions in Criticism-Edinburgh University Press PDFfekir64No ratings yet

- Hope 1Document4 pagesHope 1Emily T. Nonato100% (7)

- 20 Minute Phonemic Training for Dyslexia, Auditory Processing, and Spelling: A Complete Resource for Speech Pathologists, Intervention Specialists, and Reading TutorsFrom Everand20 Minute Phonemic Training for Dyslexia, Auditory Processing, and Spelling: A Complete Resource for Speech Pathologists, Intervention Specialists, and Reading TutorsNo ratings yet

- DYSPHAGIA GOALS LONG TERM GOALS - SWALLOWING - PDF Free Download PDFDocument6 pagesDYSPHAGIA GOALS LONG TERM GOALS - SWALLOWING - PDF Free Download PDFMayraNo ratings yet

- Paul H. Hirst - Knowledge and The Curriculum - A Collection of Philosophical Papers PDFDocument156 pagesPaul H. Hirst - Knowledge and The Curriculum - A Collection of Philosophical Papers PDFDewi Sari WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Hope 3Document4 pagesHope 3Emily T. NonatoNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesRoessi Mae Abude AratNo ratings yet

- English 7 Cur MapDocument26 pagesEnglish 7 Cur MapVan DamNo ratings yet

- English 7 Curriculum MapdocxDocument26 pagesEnglish 7 Curriculum MapdocxStella Mariz ArganaNo ratings yet

- RPS KPT English 1Document5 pagesRPS KPT English 1Anna FauziahNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Lesson PlansDocument25 pagesAssignment 1 Lesson Plansapi-369323765No ratings yet

- Smith Metro Symp 15 ApraxiaDocument30 pagesSmith Metro Symp 15 ApraxiachamilaNo ratings yet

- Julia Mershon TLP HandoutDocument5 pagesJulia Mershon TLP Handoutapi-529096611No ratings yet

- Canchild - BrochuresDocument20 pagesCanchild - Brochurescharest.catherineNo ratings yet

- Training Design CSEDocument5 pagesTraining Design CSEMilesAlidoRamentoNo ratings yet

- Sight Word and Phonics Training in Children With DyslexiaDocument17 pagesSight Word and Phonics Training in Children With DyslexiaYamin PhyoNo ratings yet

- 4 Selecting An AccommodationDocument8 pages4 Selecting An AccommodationArenga, Mary RoseNo ratings yet

- Individual Learning Monitoring PlanDocument7 pagesIndividual Learning Monitoring PlanJanet Manalo GamayotNo ratings yet

- MI Symp 2008 Deaf Ed Toolkit2Document98 pagesMI Symp 2008 Deaf Ed Toolkit2Muhammad-YounusNo ratings yet

- Colaboración Fono y EducadoresDocument17 pagesColaboración Fono y EducadoresCamii MVNo ratings yet

- Eldoa Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesEldoa Lesson Planapi-359540985No ratings yet

- Southern Leyte State University - Bontoc CampusDocument5 pagesSouthern Leyte State University - Bontoc Campusjeden c. beltranNo ratings yet

- Prof Educ 2Document11 pagesProf Educ 2Cyrell RiezaNo ratings yet

- Masining Na PagpapahayagDocument14 pagesMasining Na PagpapahayagGeralyn Pelayo AlburoNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map English 7Document28 pagesCurriculum Map English 7Mark Cesar VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- DLP - Oral CommunicationDocument8 pagesDLP - Oral CommunicationAgnes Asuncion VelascoNo ratings yet

- Ucap 2016 UpdatedDocument2 pagesUcap 2016 Updatedapi-262717088No ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Region I Robert B. Estrella Memorial National High School Carmen East, Rosales, PangasinanDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Region I Robert B. Estrella Memorial National High School Carmen East, Rosales, PangasinanJaps GarciaNo ratings yet

- Presentation ParkerDocument17 pagesPresentation Parkerapi-456518489No ratings yet

- Planificacion Curricular 3er BguDocument16 pagesPlanificacion Curricular 3er BguethanNo ratings yet

- MTB MLE SyllabusDocument10 pagesMTB MLE Syllabusjade tagabNo ratings yet

- Mystery Science 1 TaskstreamDocument10 pagesMystery Science 1 Taskstreamapi-435596493No ratings yet

- Ele2 Week-4Document4 pagesEle2 Week-4nebrejakayeannvillelaNo ratings yet

- Assessing Listening and Speaking Skills. ERIC DigestDocument7 pagesAssessing Listening and Speaking Skills. ERIC DigestDini HaryantiNo ratings yet

- SW285@jh - Edu/: Classroom Management IDocument16 pagesSW285@jh - Edu/: Classroom Management Iapi-506389013No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan PortDocument4 pagesLesson Plan Portapi-397840564No ratings yet

- Canchild - Information - SheetDocument10 pagesCanchild - Information - Sheetcharest.catherineNo ratings yet

- Mystery Science 2 Lesson PlanDocument7 pagesMystery Science 2 Lesson Planapi-435596493No ratings yet

- Observation Report 1 - Ariana SzepDocument3 pagesObservation Report 1 - Ariana Szepapi-666802127No ratings yet

- Storkel 2019 Using Developmental Norms For Speech Sounds As A Means of Determining Treatment Eligibility in SchoolsDocument9 pagesStorkel 2019 Using Developmental Norms For Speech Sounds As A Means of Determining Treatment Eligibility in SchoolsameeraNo ratings yet

- ASHAGuidelines Roles School SLPDocument63 pagesASHAGuidelines Roles School SLProkiah.razakNo ratings yet

- FotippopcycleDocument4 pagesFotippopcycleapi-572147191No ratings yet

- Microcurrucular Planning p1 1bgu Q1uemsa 21-22Document7 pagesMicrocurrucular Planning p1 1bgu Q1uemsa 21-22Gabriela CarrilloNo ratings yet

- Div Research Agenda DraftDocument5 pagesDiv Research Agenda DraftALBERT HISOLERNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument11 pagesLesson Planshai mozNo ratings yet

- Subject Curriculum: Enhanced K To 12 CurriculumDocument6 pagesSubject Curriculum: Enhanced K To 12 Curriculumjohn tuberaNo ratings yet

- Inclusion Look-Fors Dec 10 2013 Final VersionDocument9 pagesInclusion Look-Fors Dec 10 2013 Final Versionapi-249399814No ratings yet

- Workplan-On-Tutok BasaDocument2 pagesWorkplan-On-Tutok BasaJohn SyNo ratings yet

- Task-Based Language TeachingDocument15 pagesTask-Based Language TeachingAnntonitte Jumao-asNo ratings yet

- Consolidation SMEA AnajaoES Q1 2022-2023Document3 pagesConsolidation SMEA AnajaoES Q1 2022-2023grace jay sarinasNo ratings yet

- Midway EvaluationDocument5 pagesMidway Evaluationapi-316050165No ratings yet

- Fidp Hope 4Document4 pagesFidp Hope 4Almerto RicoNo ratings yet

- Expanding Possibilities in Distance LearningDocument1 pageExpanding Possibilities in Distance LearningAchristalyn Alanzalon TamondongNo ratings yet

- Sw-Cmisummer2020elasyllabus 1Document16 pagesSw-Cmisummer2020elasyllabus 1api-506389013No ratings yet

- Kip Matrix Previous Studies SampleDocument3 pagesKip Matrix Previous Studies Sampleapi-520857608No ratings yet

- PD LogDocument2 pagesPD Logapi-722832988No ratings yet

- Microcurrucular Planning p1 9 Egb Q 1uemsa 21-22Document5 pagesMicrocurrucular Planning p1 9 Egb Q 1uemsa 21-22Gabriela CarrilloNo ratings yet

- Nuernberger 2013Document7 pagesNuernberger 2013Wanessa AndradeNo ratings yet

- EL RoadmapDocument16 pagesEL RoadmapSherry PerryNo ratings yet

- HSL 826 Aural Rehabilitation - Pediatric Syllabus Spring 2017Document43 pagesHSL 826 Aural Rehabilitation - Pediatric Syllabus Spring 2017api-349133705No ratings yet

- Activities to Facilitate Motor, Sensory and Language Skills: Parent Resource Series, #2From EverandActivities to Facilitate Motor, Sensory and Language Skills: Parent Resource Series, #2Rating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- ASHA Guidelines For Early Intervention IncludeDocument10 pagesASHA Guidelines For Early Intervention IncludeMayraNo ratings yet

- IDDSI Framework Testing Methods 2.0 - 2019Document14 pagesIDDSI Framework Testing Methods 2.0 - 2019MayraNo ratings yet

- 1009 Swigert PDFDocument143 pages1009 Swigert PDFMayraNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Brain Injury 9.17.19Document2 pagesTraumatic Brain Injury 9.17.19MayraNo ratings yet

- How To Treat Speech Sound Disorders 2Document5 pagesHow To Treat Speech Sound Disorders 2MayraNo ratings yet

- SC23 Gillon PDFDocument115 pagesSC23 Gillon PDFMayraNo ratings yet

- SPEECH TO GO: Ideas For Speech and Language Therapy: ASHA 2010 PhiladelphiaDocument25 pagesSPEECH TO GO: Ideas For Speech and Language Therapy: ASHA 2010 PhiladelphiaMayraNo ratings yet

- Introduc On: Renee Perona, B.S. & Abbie Olszewski, PH.D., CCC-SLP University of Nevada, RenoDocument1 pageIntroduc On: Renee Perona, B.S. & Abbie Olszewski, PH.D., CCC-SLP University of Nevada, RenoMayraNo ratings yet

- Ethics For Real: Case Studies Applying The Asha Code of EthicsDocument36 pagesEthics For Real: Case Studies Applying The Asha Code of EthicsMayraNo ratings yet

- Frey - SLIDES - OregonSLHS Conference - PMDocument111 pagesFrey - SLIDES - OregonSLHS Conference - PMMayraNo ratings yet

- 1116 FochtDocument195 pages1116 FochtMayraNo ratings yet

- Power Point SlidesDocument42 pagesPower Point SlidesMayraNo ratings yet

- GraduateDocument60 pagesGraduateMayraNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement: Children Should Be Involved in Programs of Early LiteracyDocument1 pageThesis Statement: Children Should Be Involved in Programs of Early LiteracyMayraNo ratings yet

- Spanish Resources For Childrens LiteracyDocument4 pagesSpanish Resources For Childrens LiteracyMayraNo ratings yet

- Oral Summary 1: "My Stroke of Insight" by Jill Bolte Taylor (TED Talk)Document1 pageOral Summary 1: "My Stroke of Insight" by Jill Bolte Taylor (TED Talk)MayraNo ratings yet

- Mayra Martinez Journal 7Document3 pagesMayra Martinez Journal 7MayraNo ratings yet

- For A Deaf Son (Script)Document6 pagesFor A Deaf Son (Script)Mayra100% (2)

- Initial Evaluation Flow ChartDocument58 pagesInitial Evaluation Flow ChartMayraNo ratings yet

- Social Studies Syllabus 2018 2019Document4 pagesSocial Studies Syllabus 2018 2019Jan Erica R. OlipasNo ratings yet

- Mid Exam Advance 4Document5 pagesMid Exam Advance 4Ernesto Aroon Pardo MinayaNo ratings yet

- Krashen Does Duolingo TrumpDocument3 pagesKrashen Does Duolingo TrumpbuhlteufelNo ratings yet

- Cambridge English: Advanced (CAE)Document7 pagesCambridge English: Advanced (CAE)neoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 4 - Present and Past TenseDocument4 pagesLesson Plan 4 - Present and Past Tenseapi-301142304No ratings yet

- BUS 727 Organisational Behaviour PDFDocument245 pagesBUS 727 Organisational Behaviour PDFLawrenceNo ratings yet

- Sample of Proposal LettersDocument3 pagesSample of Proposal LettersAtiqullah sherzadNo ratings yet

- 3 - Bias - and - Variance - With - Mismatched - Data - DistributionsDocument2 pages3 - Bias - and - Variance - With - Mismatched - Data - DistributionsArchit MangrulkarNo ratings yet

- Understanding Historical Life in Its Own TermsDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Historical Life in Its Own TermsPat AlethiaNo ratings yet

- Beginners Somali GrammarDocument176 pagesBeginners Somali GrammarIbratoxiic KeNo ratings yet

- Lesson-Plan-Template Jaypee 1Document4 pagesLesson-Plan-Template Jaypee 1Jerrelyn MagtagadNo ratings yet

- Supervisor and Pre-Service Teacher Feedback Reflection School PlacementDocument6 pagesSupervisor and Pre-Service Teacher Feedback Reflection School Placementapi-465735315100% (1)

- Exam Stress ManagementDocument31 pagesExam Stress ManagementBio Sciences90% (10)

- 2 Comparative Performance Study of DBN LSTM CNN and SAE Models For Wind Speed and Direction Forecasting 2Document5 pages2 Comparative Performance Study of DBN LSTM CNN and SAE Models For Wind Speed and Direction Forecasting 2Audace DidaviNo ratings yet

- Heyl 2007 Ethnographic Interviewing Handbook of EthnographyDocument16 pagesHeyl 2007 Ethnographic Interviewing Handbook of EthnographyJosé LópezNo ratings yet

- Chomsky, N. 2011 - Language and Other Cognitive SystemsDocument17 pagesChomsky, N. 2011 - Language and Other Cognitive SystemsrigsitoNo ratings yet

- Self-Paced Learning Module: Diffun CampusDocument10 pagesSelf-Paced Learning Module: Diffun CampusCharlie MerialesNo ratings yet

- 7 Cs 0F CommunicationDocument19 pages7 Cs 0F CommunicationQaisar BasheerNo ratings yet

- Adjectives 2 PDFDocument2 pagesAdjectives 2 PDFSally Consumo KongNo ratings yet

- Peer Reviewed Title:: Jany, CarmenDocument263 pagesPeer Reviewed Title:: Jany, CarmenGuglielmo CinqueNo ratings yet

- TOEFL IBT Cliche in TOEFL Ibt Writing Ingtd SortedDocument2 pagesTOEFL IBT Cliche in TOEFL Ibt Writing Ingtd SortediEnglish Garhoud 1No ratings yet

- Ryle On MindDocument1 pageRyle On MindAnna Sophia EbuenNo ratings yet

- Writing Sub-Test: Occupational English Test Test InformationDocument10 pagesWriting Sub-Test: Occupational English Test Test InformationKamel Souidi100% (2)

- English 4Document7 pagesEnglish 4Jane Balneg-Jumalon TomarongNo ratings yet

- Strategies For Translating Metaphorical Collocations in The Holy Qur'anDocument9 pagesStrategies For Translating Metaphorical Collocations in The Holy Qur'anJOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN LINGUISTICSNo ratings yet

- Imrad Research Format 1 AutorecoveredDocument30 pagesImrad Research Format 1 AutorecoveredDave Libres Enterina60% (5)

- Display Stock Level 2 BeautyDocument4 pagesDisplay Stock Level 2 Beautymeera punNo ratings yet