Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Muzzle An Ox

Muzzle An Ox

Uploaded by

the conquerorOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Muzzle An Ox

Muzzle An Ox

Uploaded by

the conquerorCopyright:

Available Formats

“You shall not muzzle an ox when it is treading out the grain”

(Deut. 25:4).

This command, which appears only once in the Old Testament,

would garner little attention except for the fact that the apostle Paul

cites it not once but twice (1 Cor. 9:9; 1 Tim. 5:18), making

apostolic application to his right to be supported financially as a

minister of the gospel. And he does so in such a way that it makes it

sound like he is bypassing what the command was originally about.

Moses (serving as the covenant mediator for Yahweh) seems

compassionately concerned about the oxen getting enough to eat,

getting their fair share when working hard.

Paul, on the other hand, seems to say that God isn’t primarily

concerned about oxen. In 1 Corinthians 9:9-10 he asks rhetorically:

Is it for oxen that God is concerned? [The Greek wording

implies an emphatic “No!”]

Does he [=Moses] not certainly speak for our sake?

This raises lots of questions, like:

Is Paul saying that Moses never meant this to be applied to

literal oxen?

Is he merely referring to the ultimate intention of the passage?

Is he focusing on contemporary application rather than original

meaning?

Is he quoting this verse out of context?

We can answer questions like this by going back to the text and

asking some questions of our own.

Are There Issues with the Original Text and Grammar?

There are no disputed textual or grammatical issues at play in

this Deuteronomy 25:4. A good literal translation would be: “do not

muzzle an ox in its threshing.” (“Out/of the grain” is added in many

English translations for clarification; Paul himself adds it to his

quotation for the same reason.) Contra the NET Bible, there is no

specification of the owner of the ox; in other words, there is no

indication of possession (e.g., “your ox” or “his ox”). Whether the

ox is owned or borrowed by the recipient of this command must be

determined from context (both textually and historically) and logic.

In my opinion, this is a more significant consideration than it

appears at first glance.

What Did It Originally Mean?

The terseness of the command means that the motivation, the

ground, and the application must all be inferred.

The surface issue is that of muzzling. If an ox wears a muzzle

during the process of tramping the grain on the threshing floor, then

it cannot eat the grain. Yahweh through Moses is saying that this is

wrong. But the reason is not specified.

Virtually all interpreters have recognized the upshot: if an ox is

without muzzle, then it can partake of the fruit of its own labor, and

this is regarded as a good thing. But many interpreters stop at this

point and fail to press in more deeply.

Who Is the Command Really For?

One question that commentators rarely ask or answer is this: Is it the

owner of the ox, or it is someone who is renting or borrowing it?

And what is the motivation behind the command? Is the primary

issue Yahweh’s compassion and protection for animals (cf. Prov.

12:10; Jonah 4:11), or is there an element of human justice and

protection at play (cf. Deut. 22:14)?

There are two basic options for the identity of the man to whom this

command is directed: he is either (1) the owner of the ox, or (2)

someone borrowing or renting the ox. Each option could then be

subdivided based on the location of the threshing: the owner of the

ox could be (1a) threshing his own grain, or (1b) threshing someone

else’s grain; likewise, the borrower/renter could be (2a) threshing

his own grain, or (2b) threshing someone else’s grain. Schematically

we could represent the possible logical options as follows:

Owner of Renter/Borrower of

Ox Ox

Own grain 1a 2a

Someone else’s 1b 2b

grain

There is nothing in the Hebrew grammar to answer these questions

for us. All four options are perfectly compatible with the

terminology and structure of this short command.

The option of a man renting or borrowing an ox to thresh someone

else’s grain, while possible, seems historically unlikely. It is more

likely that an owner of the ox is threshing his own grain or someone

else’s, or that a renter/borrower of the ox is threshing his own grain.

We must reason our way through the situation, asking if one or more

of these three remaining options makes more sense of the

surrounding literary context, the cultural situation, and the divine

motivation.

If the command is directed to the owner of the ox—whether

threshing in his own field or in another’s—it is difficult to

understand why the stipulation is required in the first place. Oxen

were viewed as property, and there was a built-in motivation for

maintaining one’s property to perform at a maximal level. It is

difficult to see why the command would make it into the Mosaic

law given the self-interest that would already ensure such actions.

As Jan Verbruggen notes in his excellent article on this verse, “The

economic value of the ox far outweighs the value of the threshed

grain that an ox could eat while it is threshing. . . . Economically, it

would not make sense if the owner of the ox muzzled his own ox

while it is doing hard labor.”

By process of elimination, this leaves us with the situation of a man

borrowing or renting an ox to thresh his own grain. In that event, his

self-interest would entail preserving as much of his threshed grain as

possible; on the other hand, he would have no intrinsic motivation to

let the ox eat of his grain. If the animal ended up in a weakened state

or unhealthy as a result, the situation does not result in any

economic loss on his end. This, then, seems like the most plausible

situation for requiring a command. The covenant stipulation works

against the selfish motive for a man to take advantage of another

man’s property. (To use a modern analogy, at the risk of

anachronism, this is the reason that rental stores today have

agreements about returning rented equipment in good working

order; they know that when someone doesn’t own something there

is an increased propensity for recklessness and lack of diligent care.)

If this line of reasoning is correct, it cuts against the interpretive

strategy taken by commentators like Raymond Brown: “Although

all the other laws in this passage concern human rights, a

commandment is suddenly introduced which protects animals from

owners who are more concerned about working them hard than

feeding them well.” This interpretation assumes (without argument,

or without considering any other alternative) that it is the owner of

the oxen who is receiving this command. Further, it assumes that the

primary motivation is the protection of the animal. While not

wanting to deny Yahweh’s compassion for animals as part of his

created order and in accordance with his attributes, it is difficult to

account for this interpretation in the context. It seems that

Verbruggen is on more solid footing here: “If it was just a

humanitarian law for the ox, the law is clearly at odds with its

context. However, if it is a law dealing with the economic

responsibility of someone using someone else’s property, the law

fits nicely in the context.” In other words, Deuteronomy 25:4 in

context is not fundamentally a law about how to treat animals

humanely but rather a law about how to treat properly treat the

property you are borrowing or renting from someone. Seen in this

light, v. 4 fits the original context quite well. Otherwise the verse is

an anomaly which seems to stand out.

So What’s Going on in the New Testament?

In 1 Timothy 5:17 Paul writes, “Let the elders who rule well be

considered worthy of double honor, especially those who labor in

preaching and teaching.” In v. 18 Paul grounds this teaching with

two quotations: “You shall not muzzle an ox when it treads out the

grain” (Deut. 25:4) and “The laborer deserves his wages” (Luke

10:7; cf. Matt. 10:10). Paul’s point is that pastor-elders should not

be taken for granted or taken advantage of, but rather should be

adequately compensated for their gospel labors.

Paul’s citation of Deuteronomy 25:4 in 1 Corinthians 9:9 is more

complicated and has generated more discussion. At the end of the

day, the function and argument is the same. What was a general

principle in 1 Timothy 5:18 now becomes a personal and specific

instantiation of this idea. Here Paul is arguing that he and Barnabas

have the right to receive adequate compensation for their ministry

labors. The most striking feature for our purposes is that Paul seems

to say that God is really not concerned about the oxen after all,

which is in tension with the traditional interpretation that the

primary purpose of Deuteronomy 25:4 is to protect the oxen (that is,

the one doing the work).

Numerous interpretations have been put forth. For example, Fee

argues that laws, by their very nature, “do not intend to touch all

circumstances; hence they regularly function as paradigms for

application in all sorts of human circumstances. . . . Paul does not

speak to what the law originally meant. . . . He is concerned with

what it means, that is, with its application to their present situation.”

More specifically, Ciampa and Rosner argue, “Paul’s statement

need not (and should not) be taken as an absolute denial that the law

was given for the sake of animals, but as a strong assertion that God

is even more concerned about humans (and that he was particularly

concerned to give guidance for the eschatological community of the

church).”

Luther, in a typically humorous but insightful aside, says that this

command can’t be for the oxen because “oxen can’t read!”

Calvin elaborates:

[T]hough the Lord commands consideration for the oxen, He does

so, not for the sake of the oxen, but rather out of regard for men, for

whose benefit even the very oxen were created. Therefore that

humane treatment of oxen ought to be an incentive, moving us to

treat each other with consideration and fairness. . . . God is not

concerned about oxen, to the extent that oxen were the only

creatures in His mind when He made the law, for He was thinking

of men, and wanted to make them accustomed to being considerate

in behaviour, so that they might not cheat the workman of his

wages. For the ox does not take the leading part in ploughing and

threshing, but man, and it is by man’s efforts that the ox itself is set

to work. Therefore, what he goes on to add, ‘he that plougheth ought

to plough in hope’ etc., is an interpretation of the commandment, as

though he said, that it is extended, in a general way, to cover any

kind of reward for labour.

These interpretations are legitimate so far as they go, but they lack

nuance by focusing only on the “compassion” aspect of original

while ignoring the “economic justice” factors that likely provided

the motivation and impetus for the command in the first place.

To review my argument: Moses gave the command to provide for

the ox, but ultimately to protect an Israelite from being unjustly

treated at the hand of one who borrows or rents his ox. The one

benefiting from the labor of an ox should not take economic

advantage of the owner of the ox.

Once this is seen, rich texture is added to Paul’s use of this verse.

His point is not really that the Corinthians should

have compassion or mercy for him and Barnabas, but that this is a

matter of fundamental justice. The issue is not really kindness, but

rights. When Paul says this is not really about the oxen, he is

pointing to this wider and deeper reality at play in this verse as it

was originally to be understood. Therefore the Corinthians should

want to provide appropriate compensation as an expression of

justice, even if Paul ultimately rejects the offer.

Help on the New Testament Citing the Old

If this minority interpretation—which is indebted to

Verbruggen’s helpful work—is correct, then there are at least two

implications for understanding how the New Testament cites the

Old Testament: (1) never ignore the original OT context; (2) be slow

to assume that the NT writers are quoting things out of context. And

even if my view is wrong, these two principles still apply!

You might also like

- 1 Cor 10.14-22 - Exegetical Case For Closed CommunionDocument17 pages1 Cor 10.14-22 - Exegetical Case For Closed Communion31songofjoy100% (1)

- Test Bank For Operations and Supply Chain Management The Core 1st Canadian Edition by JacobsDocument43 pagesTest Bank For Operations and Supply Chain Management The Core 1st Canadian Edition by Jacobsa852137207No ratings yet

- Ravi Zacharias - God's Sovereignty and Man's Free WillDocument2 pagesRavi Zacharias - God's Sovereignty and Man's Free Willpetsam00790% (10)

- Smith-Hear, My Son - An Examination of The Fatherhood of Yahweh in Deuteronomy - Ralph Allan Smith (Athanasius) 2011Document129 pagesSmith-Hear, My Son - An Examination of The Fatherhood of Yahweh in Deuteronomy - Ralph Allan Smith (Athanasius) 2011ralph_smith_29100% (1)

- Angels As Arguments The Rhetorical Funct PDFDocument8 pagesAngels As Arguments The Rhetorical Funct PDFIswadiPrayidnoNo ratings yet

- The Sacred Cows of Bible Study by Bill SomersDocument22 pagesThe Sacred Cows of Bible Study by Bill SomersBill SomersNo ratings yet

- Paul's View of The StateDocument6 pagesPaul's View of The Statejohnterry.80807No ratings yet

- Levi C. Jones N.T. Wright's Justificaton: God's Plan and Paul's Vision Chapter 1: What Does Wright See As The Two Key Puzzle Pieces To Reading Paul That Are Often Overlooked?Document10 pagesLevi C. Jones N.T. Wright's Justificaton: God's Plan and Paul's Vision Chapter 1: What Does Wright See As The Two Key Puzzle Pieces To Reading Paul That Are Often Overlooked?api-26004101No ratings yet

- FAMILY LIFE (Wofi)Document27 pagesFAMILY LIFE (Wofi)batsho mazwidumaNo ratings yet

- Roman Law in The Writings of Paul - AdoptionDocument10 pagesRoman Law in The Writings of Paul - Adoption31songofjoyNo ratings yet

- Eagle Eye: Cloudy VisionDocument5 pagesEagle Eye: Cloudy VisionBryan LynchNo ratings yet

- Animals Their Past and FutureDocument16 pagesAnimals Their Past and FutureAndrias SilvaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Figurative Language in Scripture: 1. SimileDocument8 pagesAn Overview of Figurative Language in Scripture: 1. SimileSonjathang SitlhouNo ratings yet

- Jewish Philanthropy - Whither?: Aharon LichtensteinDocument28 pagesJewish Philanthropy - Whither?: Aharon Lichtensteinoutdash2No ratings yet

- Loving Covenantal LoveDocument17 pagesLoving Covenantal LoveColt TNo ratings yet

- Alf Ross - Tu-TuDocument5 pagesAlf Ross - Tu-TusagararunNo ratings yet

- Pauline HomosexualityDocument6 pagesPauline Homosexualityapi-2409193040% (1)

- Slaves and SinDocument3 pagesSlaves and SinDuan GonmeiNo ratings yet

- GalutDocument3 pagesGalutAdim AresNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The TitheDocument11 pagesThe Evolution of The Tithemybiyi7740No ratings yet

- "Passing On The Torch": A Study of 2 Timothy Sermon # 4Document5 pages"Passing On The Torch": A Study of 2 Timothy Sermon # 4Alexander George SamNo ratings yet

- The Myth of The Meaning of The First Class Condition in Greek - WallaceDocument5 pagesThe Myth of The Meaning of The First Class Condition in Greek - WallaceVern PetermanNo ratings yet

- Bible StudiesDocument60 pagesBible StudiesSaulo BledoffNo ratings yet

- Grammar and SyntaxDocument22 pagesGrammar and SyntaxDbishNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical AnalysisDocument11 pagesRhetorical Analysisapi-643125012No ratings yet

- Toronto TorahDocument4 pagesToronto Torahoutdash2No ratings yet

- Toronto TorahDocument4 pagesToronto Torahoutdash2No ratings yet

- Righteousness by Faith - Gods Part Our PartDocument60 pagesRighteousness by Faith - Gods Part Our PartSimon kariukiNo ratings yet

- How Hobbes Struck Down God From The HeavenDocument9 pagesHow Hobbes Struck Down God From The HeavenAlex NemecNo ratings yet

- The Christian Man in Relation To His Children: The FirstbornDocument29 pagesThe Christian Man in Relation To His Children: The FirstbornebeshoNo ratings yet

- Surprised by OrthodoxyDocument34 pagesSurprised by OrthodoxyBMNo ratings yet

- A Brief Exegetical Study of Galatians 3:26 - 4:7Document14 pagesA Brief Exegetical Study of Galatians 3:26 - 4:7Andrew PackerNo ratings yet

- The Way for The World - Deuteronomy/Debareeym: The Way for The World, #5From EverandThe Way for The World - Deuteronomy/Debareeym: The Way for The World, #5No ratings yet

- Words: Matos-MaseiDocument2 pagesWords: Matos-Maseioutdash2No ratings yet

- The Society of Biblical LiteratureDocument17 pagesThe Society of Biblical LiteratureMa10cent100% (1)

- Talmud - Mas. Arachin 2a Talmud - Mas. Arachin 2aDocument119 pagesTalmud - Mas. Arachin 2a Talmud - Mas. Arachin 2abinchacNo ratings yet

- The Way for the World - Numbers/Bemidbar: The Way for The World, #4From EverandThe Way for the World - Numbers/Bemidbar: The Way for The World, #4No ratings yet

- JETS 49-3 527-548 MerkleDocument22 pagesJETS 49-3 527-548 Merklemorales silvaNo ratings yet

- Interpreting The ParablesDocument16 pagesInterpreting The Parablesrajiv karunakarNo ratings yet

- 3rd Angel's MessageDocument229 pages3rd Angel's MessageDIDAKALOSNo ratings yet

- An Overlooked Scriptural ParadoxDocument18 pagesAn Overlooked Scriptural ParadoxDamjanNo ratings yet

- Holy Is a Four-Letter Word: How to Live a Holy Life in an Unholy WorldFrom EverandHoly Is a Four-Letter Word: How to Live a Holy Life in an Unholy WorldNo ratings yet

- As We Approach Midnight 2Document7 pagesAs We Approach Midnight 2Theodore James TurnerNo ratings yet

- Is Ecclesiastes The Antithesis of Proverbs'?: What Is Wisdom Literature?Document9 pagesIs Ecclesiastes The Antithesis of Proverbs'?: What Is Wisdom Literature?Jose Miguel Alarcon CuevasNo ratings yet

- Westlaw Delivery Summary Report For IP USER, NOVUS: Tû-Tû. The Talk About Tû-Tû Is Pure NonsenseDocument5 pagesWestlaw Delivery Summary Report For IP USER, NOVUS: Tû-Tû. The Talk About Tû-Tû Is Pure NonsenseAbry AnthraperNo ratings yet

- THEPRODIGALSONDocument9 pagesTHEPRODIGALSONJoharah CuizonNo ratings yet

- RHODES Hobbes's UnReasonable FoolDocument10 pagesRHODES Hobbes's UnReasonable FoolMarcelo BoniniNo ratings yet

- Group 6 Report - Parables (Chapter 8) - 1Document11 pagesGroup 6 Report - Parables (Chapter 8) - 1Michaela PowellNo ratings yet

- I Will Open My Mouth in a Parable: A Study (Matthew's Parables on the Kingdom) of Biblical Parables, Part 1: Series on the Parables, #1From EverandI Will Open My Mouth in a Parable: A Study (Matthew's Parables on the Kingdom) of Biblical Parables, Part 1: Series on the Parables, #1No ratings yet

- Qohelet and MoneyDocument19 pagesQohelet and MoneyRyan HayesNo ratings yet

- The Law Was Meant To Be KeptDocument23 pagesThe Law Was Meant To Be KeptgregoryNo ratings yet

- Does God's Grace Nullify His Law?Document9 pagesDoes God's Grace Nullify His Law?Bryan T. HuieNo ratings yet

- Galatians 4Document76 pagesGalatians 4Ella CaspillanNo ratings yet

- Parables in The Bible and Their InterpretationDocument6 pagesParables in The Bible and Their InterpretationyedenarNo ratings yet

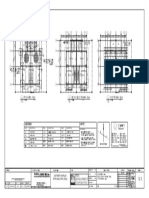

- Structural Irregularities - Version1 PDFDocument9 pagesStructural Irregularities - Version1 PDFthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Structural Irregularities PDFDocument13 pagesStructural Irregularities PDFthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Column Two BeamsDocument7 pagesColumn Two Beamsthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Column and Weak BeamDocument4 pagesColumn and Weak Beamthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Health SafetyDocument3 pagesHealth Safetythe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Small Space Staircase: Collection byDocument8 pagesSmall Space Staircase: Collection bythe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Evangelista-Final Report Structural Investigation PDFDocument16 pagesEvangelista-Final Report Structural Investigation PDFthe conqueror100% (3)

- Carbon Fiber PDFDocument6 pagesCarbon Fiber PDFthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- National Plumbing Code of The Philippines (Republic Act 1378 "Plumbing Law")Document15 pagesNational Plumbing Code of The Philippines (Republic Act 1378 "Plumbing Law")the conqueror100% (1)

- Subject: Design of Concrete Beam: F'C 21 Fy 415 Fyt 276Document2 pagesSubject: Design of Concrete Beam: F'C 21 Fy 415 Fyt 276the conquerorNo ratings yet

- Feliix Systems Furniture: 10 Small Staircases in Indian HomesDocument12 pagesFeliix Systems Furniture: 10 Small Staircases in Indian Homesthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- 12 Staircases For Small Indian Homes: Stiltz Homelift - ElevatorDocument17 pages12 Staircases For Small Indian Homes: Stiltz Homelift - Elevatorthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Small Staircase IdeasDocument4 pagesSmall Staircase Ideasthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Beef Nilaga RecipeDocument1 pageBeef Nilaga Recipethe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Teriyaki Chicken Broccoli RecipeDocument1 pageTeriyaki Chicken Broccoli Recipethe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Occipital Neuralgia - Symptoms, Causes, and TreatmentsDocument11 pagesOccipital Neuralgia - Symptoms, Causes, and Treatmentsthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Headache Behind The Ear - Causes, Treatment, and MoreDocument12 pagesHeadache Behind The Ear - Causes, Treatment, and Morethe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Interior DesignsDocument90 pagesInterior Designsthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- 35 Hair Tips For Men, According To Experts PDFDocument51 pages35 Hair Tips For Men, According To Experts PDFthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Structural Notes: Associates, IncDocument1 pageStructural Notes: Associates, Incthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Built in Gutter Design and Detailing: Levine & Company, Inc Ardmore, PennsylvaniaDocument17 pagesBuilt in Gutter Design and Detailing: Levine & Company, Inc Ardmore, Pennsylvaniathe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Stir-Fried Beef and Broccoli With Ginger - Kalyn's KitchenDocument2 pagesStir-Fried Beef and Broccoli With Ginger - Kalyn's Kitchenthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- VBDC Construction: Renovation of Marissa-Carlos ApartmentDocument5 pagesVBDC Construction: Renovation of Marissa-Carlos Apartmentthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Katigbak Enterprises, IncorporatedDocument14 pagesKatigbak Enterprises, Incorporatedthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- At Activity Projected Schedule Status: Total AccomplishmentDocument2 pagesAt Activity Projected Schedule Status: Total Accomplishmentthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- 05132020S THE2 PDD1 ss2 S-1Document1 page05132020S THE2 PDD1 ss2 S-1the conquerorNo ratings yet

- I Legends: Note:: & VLGVDocument1 pageI Legends: Note:: & VLGVthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Sinigang Na Baboy Recipe - Knorr PDFDocument2 pagesSinigang Na Baboy Recipe - Knorr PDFthe conquerorNo ratings yet

- Erf FormsDocument2 pagesErf FormsstartonNo ratings yet

- IFSCDocument250 pagesIFSCpapuali_100No ratings yet

- Full Resynchronization of An Admin ServerDocument6 pagesFull Resynchronization of An Admin ServerSatyasiba DasNo ratings yet

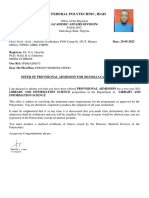

- The Federal Polytechnic, IdahDocument3 pagesThe Federal Polytechnic, Idahwisdomeneojoufedo0147No ratings yet

- Grammar Extra - The Present Perfect TenseDocument4 pagesGrammar Extra - The Present Perfect TenseNghĩa TrọngNo ratings yet

- Industrial and Commercial Training - Values Based LeadershipDocument8 pagesIndustrial and Commercial Training - Values Based LeadershipJailamNo ratings yet

- Pseudo Code ExamplesDocument4 pagesPseudo Code ExamplesViji RamNo ratings yet

- State Quality FilinnialDocument3 pagesState Quality FilinnialMichaella Acebuche50% (2)

- 11 04 04dccircnnorderDocument2 pages11 04 04dccircnnorderJonHealeyNo ratings yet

- 2024 Letter To City HallDocument5 pages2024 Letter To City HallJanelyn BayanNo ratings yet

- Joachim Hagopian v. Major General William Knowlton, 470 F.2d 201, 2d Cir. (1972)Document14 pagesJoachim Hagopian v. Major General William Knowlton, 470 F.2d 201, 2d Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- WB Mop Up RoundDocument6 pagesWB Mop Up RoundSpandan DaschowdhuryNo ratings yet

- 1 - SchoolisDead - ReimerDocument29 pages1 - SchoolisDead - ReimerKarmen RežekNo ratings yet

- Successful Entrepreneur in BangladeshDocument7 pagesSuccessful Entrepreneur in BangladeshRajib AhmedNo ratings yet

- Philippine LiteratureDocument3 pagesPhilippine Literatureobra_maestra111100% (3)

- ACTBFAR Exercise Set #1 - Ex 4 - PS SpacingDocument3 pagesACTBFAR Exercise Set #1 - Ex 4 - PS SpacingNikko Bowie PascualNo ratings yet

- Arts in Asia .Test Paper.1Document3 pagesArts in Asia .Test Paper.1Reziel Tamayo PayaronNo ratings yet

- JMAA Memo Motion For Protective OrderDocument4 pagesJMAA Memo Motion For Protective Orderthe kingfishNo ratings yet

- Simex International (Manila), Inc. vs. Court of AppealsDocument6 pagesSimex International (Manila), Inc. vs. Court of Appeals유니스No ratings yet

- IRDAI English Annual Report 2018-19 PDFDocument228 pagesIRDAI English Annual Report 2018-19 PDFDevraj DashNo ratings yet

- Final International ArbitrationDocument4 pagesFinal International ArbitrationSchool of Law TSUNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Climate Change On Hydropower Generation in China: SciencedirectDocument15 pagesImpacts of Climate Change On Hydropower Generation in China: SciencedirectWaldo LavadoNo ratings yet

- Đề kiểm tra giữa HKII - 11Anh 211Document6 pagesĐề kiểm tra giữa HKII - 11Anh 211Ngô ThảoNo ratings yet

- Grammar Handbook Parts of SpeechDocument29 pagesGrammar Handbook Parts of SpeechClayton OgilvyNo ratings yet

- The Fire of Freedom, Volume 1: Satsang With Papaji, Volume 1. Awdhuta FoundationDocument3 pagesThe Fire of Freedom, Volume 1: Satsang With Papaji, Volume 1. Awdhuta FoundationTechnologyNo ratings yet

- đề 15Document7 pagesđề 15Thuphuong LeNo ratings yet

- SAP 1 - Law - BCR Answer Key - (24-10-2021)Document13 pagesSAP 1 - Law - BCR Answer Key - (24-10-2021)PradeepNo ratings yet

- Assigment NutritionDocument10 pagesAssigment NutritionValdemiro NhantumboNo ratings yet

- End of Term Essay - PDF Version - El Alaoui SanaaDocument8 pagesEnd of Term Essay - PDF Version - El Alaoui SanaaallalNo ratings yet