Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 Summary

Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 Summary

Uploaded by

IkramCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Business Vantage Listening Sample Paper 2 - Full TestDocument8 pagesBusiness Vantage Listening Sample Paper 2 - Full TestDaniel KottnauerNo ratings yet

- Test Unit 4Document4 pagesTest Unit 4PepiLopez100% (2)

- An Analysis of Sonnet 18 by William ShakespeareDocument6 pagesAn Analysis of Sonnet 18 by William ShakespeareHilde LyshaugenNo ratings yet

- Journeys CC Writing Handbook Gr6 PDFDocument6 pagesJourneys CC Writing Handbook Gr6 PDFIkram100% (1)

- Ferrite Transformer Turns Calculation For HighDocument67 pagesFerrite Transformer Turns Calculation For Highjaigodara0% (1)

- Reading For Understanding: Sonnet 18: Analysis Version 1Document9 pagesReading For Understanding: Sonnet 18: Analysis Version 1Trang HoangNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18Document3 pagesSonnet 18mjostinaNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 - NotesDocument10 pagesSonnet 18 - NotesMaryke OberholzerNo ratings yet

- SonnetDocument11 pagesSonnetAndreea BalanNo ratings yet

- Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's DayDocument25 pagesShall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Dayserenan2306No ratings yet

- Shall I Compare You To A Summer Day AnalysisDocument9 pagesShall I Compare You To A Summer Day AnalysisStefNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 - Text and AnalysisDocument4 pagesSonnet 18 - Text and AnalysisNabinur rahmanNo ratings yet

- Sonnet (18) : Shall I Compare TheeDocument28 pagesSonnet (18) : Shall I Compare Theesarah100% (1)

- Sonnet 18 - NotesDocument6 pagesSonnet 18 - NotesFatima KabirNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer 'Document20 pagesSonnet 18 Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer 'mrstoyaNo ratings yet

- Lunaquezada 2017shakespearessonnetanalysisDocument3 pagesLunaquezada 2017shakespearessonnetanalysisapi-345781302No ratings yet

- Shakespeare Famously AsksDocument2 pagesShakespeare Famously AsksNoreen ShahNo ratings yet

- 23953Document9 pages23953bodatiger2002No ratings yet

- Shakespeare BDocument2 pagesShakespeare BGuim PedreroNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Sonnets ExerciseDocument2 pagesShakespeare Sonnets ExerciseKaylee KimNo ratings yet

- English PoemsDocument20 pagesEnglish PoemsShannon SwanepoelNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18Document3 pagesSonnet 18RemyNo ratings yet

- Workshop 2 - Oza 11dDocument3 pagesWorkshop 2 - Oza 11dapi-369154238No ratings yet

- Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Day? (Sonnet 18) : Interpret His Poem Line-By-Line Annotate 5 CommentsDocument3 pagesShall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Day? (Sonnet 18) : Interpret His Poem Line-By-Line Annotate 5 Commentsapi-318781847No ratings yet

- Shall I Compare Thee To A SummerDocument5 pagesShall I Compare Thee To A SummersarahNo ratings yet

- ShakespearesSonnet18PoetryCloseReadingAnalysisFREEBIE 1Document5 pagesShakespearesSonnet18PoetryCloseReadingAnalysisFREEBIE 1Sabrina MabantaNo ratings yet

- 16th C - Renaissance - ShakespeareDocument6 pages16th C - Renaissance - ShakespeareVlindertjeNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Sonnet1Document2 pagesShakespeare Sonnet1Michael GöppelNo ratings yet

- Before We Go Into Summarizing Sonnet 73Document15 pagesBefore We Go Into Summarizing Sonnet 73Camille Llamas EvangelioNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Sonnet18 HenrietDocument18 pagesShakespeare Sonnet18 Henrietmassaalkadri2006No ratings yet

- Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's DayDocument5 pagesShall I Compare Thee To A Summer's DayFront RowNo ratings yet

- Theme and Summary Mid Fall 23Document5 pagesTheme and Summary Mid Fall 23Jahangir AlamNo ratings yet

- Notes - Shall I Compare Thee by William ShakespeareDocument4 pagesNotes - Shall I Compare Thee by William ShakespeareAYESHA ROSHANNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18: AnalysisDocument3 pagesSonnet 18: AnalysisIrene BaeNo ratings yet

- This Is Forest Primeival The Murmuring Pines and Hemlock Sonnet 18 .. Page 113Document18 pagesThis Is Forest Primeival The Murmuring Pines and Hemlock Sonnet 18 .. Page 113Asmaa Hussain 2No ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 - PowerPointDocument17 pagesSonnet 18 - PowerPointayavuyancoko14No ratings yet

- "Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Day" Is TheDocument2 pages"Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Day" Is Theaus_92100% (3)

- Sonnet 18: William Shakespeare Listen To ThisDocument11 pagesSonnet 18: William Shakespeare Listen To ThisIlzeNo ratings yet

- "Sonnet 18" by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)Document2 pages"Sonnet 18" by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)Eniam GeeNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of Sonnet 18 by William ShakespeareDocument3 pagesThe Analysis of Sonnet 18 by William Shakespeareعلي هاشم وزيريNo ratings yet

- Metaphor Poem, Examples of Metaphor Poems by Silvia HartmannDocument7 pagesMetaphor Poem, Examples of Metaphor Poems by Silvia HartmannRajeshNo ratings yet

- Elizabethan PeriodDocument17 pagesElizabethan Periodlea guillermo100% (1)

- Shakespearean Sonnet Writing Made Easy For Year 8MDDocument3 pagesShakespearean Sonnet Writing Made Easy For Year 8MDHana JuiceNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18, Aquino.Document3 pagesSonnet 18, Aquino.Jamaica Ikan AquinoNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 NotesDocument8 pagesSonnet 18 NotesEla SinghNo ratings yet

- Spring and AllDocument4 pagesSpring and AllLovely CitraNo ratings yet

- Unit Three Sonnets OF Shakespeare: ObjectivesDocument11 pagesUnit Three Sonnets OF Shakespeare: ObjectivesEntertainment TimeNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18: Winds" in Them, The Sun ("The Eye of Heaven") Often Shines "Too Hot,"Document3 pagesSonnet 18: Winds" in Them, The Sun ("The Eye of Heaven") Often Shines "Too Hot,"احمد احمدNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18Document2 pagesSonnet 18Ry AbdelmoatyNo ratings yet

- Summary and Full Analysis of Sonnet 18Document2 pagesSummary and Full Analysis of Sonnet 18carmen predut50% (2)

- Lit AnalysisDocument29 pagesLit AnalysishansiNo ratings yet

- Name: Mahnoor Safeer Ch. SAP ID: 26292 Subject: Introduction To Literature Submitted To: Sir AbrarDocument6 pagesName: Mahnoor Safeer Ch. SAP ID: 26292 Subject: Introduction To Literature Submitted To: Sir AbrarMahnoor Ch.No ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 & 116Document6 pagesSonnet 18 & 116adnan100% (2)

- Sonnet 18Document16 pagesSonnet 18Phuong Thao LeNo ratings yet

- How To Use Close Reading MethodDocument3 pagesHow To Use Close Reading MethodDanah Mae AdvinculaNo ratings yet

- Class X English LiteratureDocument46 pagesClass X English Literaturedavidmshoute121No ratings yet

- Poetry-Sonnet 18Document4 pagesPoetry-Sonnet 18Hany FaroukNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 ShakespeareDocument2 pagesSonnet 18 ShakespeareMar MartinezNo ratings yet

- Irony Principle StructureDocument4 pagesIrony Principle Structureruttiger57No ratings yet

- The Sun Goes Down PT IIDocument1 pageThe Sun Goes Down PT IILuke Yee100% (1)

- Poetics (Translated by Ingram Bywater with a Preface by Gilbert Murray)From EverandPoetics (Translated by Ingram Bywater with a Preface by Gilbert Murray)No ratings yet

- CHALLAN No.316907828038 CHALLAN No.316907828038 CHALLAN No.316907828038Document1 pageCHALLAN No.316907828038 CHALLAN No.316907828038 CHALLAN No.316907828038IkramNo ratings yet

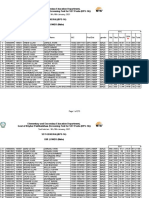

- Final Tentative Merit List CT (Bps-15) Dir Lower MaleDocument12 pagesFinal Tentative Merit List CT (Bps-15) Dir Lower MaleIkramNo ratings yet

- AbbreviationsDocument63 pagesAbbreviationsIkramNo ratings yet

- Elementary and Secondary Education Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Screening Test For SST Posts (BPS-16) )Document57 pagesElementary and Secondary Education Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Screening Test For SST Posts (BPS-16) )IkramNo ratings yet

- Seniority List of CT, Teachers District Dir Lower. (Corrected Up To 31/12/2020)Document39 pagesSeniority List of CT, Teachers District Dir Lower. (Corrected Up To 31/12/2020)IkramNo ratings yet

- Elementary and Secondary Education Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Screening Test For SST Posts (BPS-16) )Document273 pagesElementary and Secondary Education Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Screening Test For SST Posts (BPS-16) )IkramNo ratings yet

- Selection Letter Markhor 2021Document1 pageSelection Letter Markhor 2021IkramNo ratings yet

- Chapter # 1: Utmost Happiness, Roy Gives A Critical View of The Dilemma of Deviant Gender andDocument10 pagesChapter # 1: Utmost Happiness, Roy Gives A Critical View of The Dilemma of Deviant Gender andIkramNo ratings yet

- Physics 9Document71 pagesPhysics 9IkramNo ratings yet

- 4 Writing Purposes Guidance1 PDFDocument10 pages4 Writing Purposes Guidance1 PDFIkramNo ratings yet

- Bachelor Degree Essay Autumn - 08 Taawo PDFDocument21 pagesBachelor Degree Essay Autumn - 08 Taawo PDFIkramNo ratings yet

- The Theory of The Sublime From Longinus To Kant: More InformationDocument13 pagesThe Theory of The Sublime From Longinus To Kant: More InformationIkramNo ratings yet

- University of Cape Town: Pride and PrejudiceDocument96 pagesUniversity of Cape Town: Pride and PrejudiceIkramNo ratings yet

- Eighteenth-Century Female Conduct in Jane Austen's: Pride and PrejudiceDocument21 pagesEighteenth-Century Female Conduct in Jane Austen's: Pride and PrejudiceIkramNo ratings yet

- Preliminary: (The Himachal Pradesh Liquor Licence Rules, 1986)Document78 pagesPreliminary: (The Himachal Pradesh Liquor Licence Rules, 1986)Yogesh ThakurNo ratings yet

- Odisha Current AffairsDocument31 pagesOdisha Current AffairsSANGRAM SAHU100% (1)

- Allison Weir - A Study of FulviaDocument168 pagesAllison Weir - A Study of Fulviadumezil3729No ratings yet

- Prac-CAT # 10 TestDocument25 pagesPrac-CAT # 10 Testakash100% (1)

- A Study of Different Corporate Social Responsibility Activities by Tata Group in IndiaDocument48 pagesA Study of Different Corporate Social Responsibility Activities by Tata Group in IndiaJenny VermaNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Philippine TourismDocument11 pagesSyllabus Philippine TourismJohnson FernandezNo ratings yet

- A Study of Factors Affecting Travel Decision Making of TouristsDocument10 pagesA Study of Factors Affecting Travel Decision Making of TouristsAmmarah Rajput ParhiarNo ratings yet

- Instruments NotesDocument116 pagesInstruments Notesprithvih4No ratings yet

- Specification Sheet For Crystallizer Crystallizer Data SheetDocument3 pagesSpecification Sheet For Crystallizer Crystallizer Data SheetAmar RazinNo ratings yet

- Satheeshkumar Dhrithiya (NJC) - 2021-Is1-PA8.1 Tea Bag Activity - HBL (ST)Document6 pagesSatheeshkumar Dhrithiya (NJC) - 2021-Is1-PA8.1 Tea Bag Activity - HBL (ST)weiliNo ratings yet

- Middle Ages - Ged104-A7Document2 pagesMiddle Ages - Ged104-A7KleyrNo ratings yet

- Makale DosyasıDocument18 pagesMakale DosyasıBayram OzerNo ratings yet

- Guide To Getting CloserDocument17 pagesGuide To Getting CloserShaneNo ratings yet

- 56 5 3 ChemistryDocument24 pages56 5 3 ChemistrygettotonnyNo ratings yet

- GST ProjectDocument20 pagesGST ProjectHarshithaNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Accountancy, Business, and Management 2 Activity 2Document1 pageFundamentals of Accountancy, Business, and Management 2 Activity 2Joseph CincoNo ratings yet

- Database Development ProcessDocument8 pagesDatabase Development ProcessdeezNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure GF CASESDocument7 pagesSearch and Seizure GF CASESAnonymous GMUQYq8No ratings yet

- Psychiatry Question Bank - 65 Multiple Choice Questions On - Psychiatry in India - PDFDocument21 pagesPsychiatry Question Bank - 65 Multiple Choice Questions On - Psychiatry in India - PDFAnkit Gupta44% (9)

- Research Paper On Ergonomics PDFDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Ergonomics PDFefdwvgt4100% (3)

- How To Install XAMPP For WindowsDocument35 pagesHow To Install XAMPP For Windowsmarlon marcaidaNo ratings yet

- Biography Recount Text: Xi-Toi 2Document7 pagesBiography Recount Text: Xi-Toi 2Adinda GaluhNo ratings yet

- Birla AlokyaDocument18 pagesBirla AlokyaanjaligargisbNo ratings yet

- Thinker 51 Full PDFDocument84 pagesThinker 51 Full PDFNtate MoloiNo ratings yet

- Identify The Controls and Variables Worksheet: Scenario 1Document3 pagesIdentify The Controls and Variables Worksheet: Scenario 1Belen Cid ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Khedive IsmailDocument3 pagesKhedive IsmailAbimbola OyarinuNo ratings yet

- Image Image Image Image: Takeover Buybacks DelistingDocument5 pagesImage Image Image Image: Takeover Buybacks DelistingBhavin SagarNo ratings yet

Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 Summary

Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 Summary

Uploaded by

IkramOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 Summary

Shakespeare's Sonnet 18 Summary

Uploaded by

IkramCopyright:

Available Formats

12/30/2019 Sonnet 18 Summary

Sonnet 18

Sonnet 18 Summary

The speaker begins by asking whether he should or will compare "thee" to a summer day. He says that his beloved

i more lovely and more even-tempered. He then runs off a list of reasons why summer isn’t all that great: winds

shake the buds that emerged in Spring, summer ends too quickly, and the sun can get too hot or be obscured by

clouds.

He goes on, saying that everything beautiful eventually fades by chance or by nature’s inevitable changes. Coming

back to the beloved, though, he argues that his or her summer (or happy, beautiful years) won’t go away, nor will

his or her beauty fade away. Moreover, death will never be able to take the beloved, since the beloved exists in

eternal lines (meaning poetry). The speaker concludes that as long as humans exist and can see (so as to read), the

poem he’s writing will live on, allowing the beloved to keep living as well.

· Section I (lines 1-8) Lines 1-2

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

The speaker starts by asking or wondering out loud whether he ought to compare whomever

he’s speaking to with a summer’s day.

Instead of musing on that further, he jumps right in, and gives us a thesis of sorts. The

object of his description is more "lovely" and more "temperate" than a summer’s day.

"Lovely" is easy enough, but how about that "temperate"? The meaning that comes to mind

first is just "even-keeled" or "restrained," but "temperate" also introduces, by way of a double meaning,

the theme of internal and external "weather." "Temperate," as you might have heard on the Weather

Channel, refers to an area with mild temperatures, but also, in Shakespeare’s time, would have referred

to a balance of the "humours."

No need to explain this in great detail, but basically doctors since Ancient Greece had

believed that human behavior was dictated by the relative amount of particular kinds of

fluids in the body (if you must know, they were blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm.

Yummy, no?).

By the early 1600s, this theory was being strongly challenged, but people in Shakespeare’s

audience would have known that "temperate" meant that someone had the right amount of

those different fluids. The other important (and less disgusting) issue these lines bring up is

the question of "thee." Normally, we’d just assume that the object of the poem is his lover,

and leave it at that. But with Shakespeare, these things are always complicated.

What can we tell about the relationship between the speaker and his addressee from the way

he addresses "thee"?

For the moment, all we can really tell is this: the speaker doesn’t seem to care much what

"thee" thinks. He does ask whether he ought to make this comparison, but he certainly

doesn’t wait long (or at all) for an answer.

So is he just wondering out loud here, pretending "thee" is present?

Even better, and this is important, could "thee" also be us readers? Is it just us, or does some

small part of you imagine that Shakespeare might be asking you, the reader, whether you

want him to compare you to a summer’s day? Keep that on the back burner as you go

through the poem.

Finally, just a note on the meter here:

file:///C:/Users/Ikram ullah/Downloads/Sonnet 18 Summary.html 1/5

12/30/2019 Sonnet 18 Summary

Go ahead and read those first two lines out loud. Notice how they’re kind of bouncy? That’s the iambic

pentameter: "compare thee to a summer’s day."

So do you want to see a cool bit of foreshadowing? The pronoun "I" is a stressed syllable in the first line,

but the pronoun "Thou" is unstressed in the second line. Guess who’s going to be the real subject of this

poem.

Lines 3-4

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date:

Here the speaker begins to personify nature. In other words, some of the smack talking he’s

doing abou summer sounds like he’s talking about a person.

Basically, strong summer winds threaten those new flower buds that popped up in May, and

summer just doesn’t last very long.

The way he describes the short summer, though, is what’s interesting. Summer has a "lease"

on the weather, just as your family might have a lease on your car; like a person, summer

can enter into, and must abide by, agreements.

The point here is clear enough: the summer is fated to end.

But check this out: isn’t summer also fated to begin every year once again? Can the summer

possibly have "too short a date," if it happens an infinite number of times? Isn’t it, in a

meaningful sense, immortal?

Keep this in mind as you read on.

Lines 5-6

Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines,

And often is his gold complexion dimm’d;

Here comes the major personification of nature. Put simply, the speaker’s saying sometimes

the sun is too hot, and other times you can’t even see it at all (hidden, we assume, by

clouds).

But instead of being boring, he calls the sun the "eye of heaven," refers to it using the word

"his," and gives it a "complexion," which generally means refers to the skin of the face.

Check out how much more information about the summer we’re getting than we are about

the beloved. Indeed, the speaker is carefully describing the summer individually, and even

in human terms, while he only describes "thee" in one line and only relative to the summer.

"Complexion," in particular, is especially interesting, as it brings back the whole "humours"

theme we saw in "temperate."

"Complexion" used to be used to describe someone’s health, specifically with regard to their balance of

humours. Thus, we see here again that the speaker is combining descriptions of external weather

phenomena with internal balance.

Lines 7-8

And every fair from fair sometime declines,

By chance, or nature’s changing course

untrimm’d;

With these lines, the speaker gets even broader in his philosophy, declaring that everything

beautiful must eventually fade away and lose its charm, either by chance or by the natural

flow of time. Kind of like teen pop stars.

Now what exactly does "untrimm’d" refer to?

We might read it as what happens to "fair" or beautiful things. By that reading, things that

are beautiful eventually lose their trimmings, or their decorations, and thus fade from

beauty.

file:///C:/Users/Ikram ullah/Downloads/Sonnet 18 Summary.html 2/5

12/30/2019 Sonnet 18 Summary

On the other hand, "untrimm’d" is also a term from sailing, as you "trim," or adjust, the sails to take

advantage of the wind. This gives "untrimm’d" a completely opposite meaning; instead of "made ugly

and plain by natural changes," it means "unchanged in the face of nature’s natural changes." Here,

then, we are subtly prepped for the turn we’re about to see in…

· Section II (lines 9-14) Lines 9-10

But thy eternal summer shall not fade,

Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st,

The turn! Check out the "Form and Meter" section for more on line 9 in sonnets, but here’s

a classic example of a "turn."

Suddenly (though it was foreshadowed a bit in line 8), the tone and direction of the poem

changes dramatically. Moving on from bashing summer and the limitations inherent in

nature, the speaker pronounces that the beloved he’s speaking to isn’t subject to all of these

rules he’s laid out.

The speaker argues that, unlike the real summer, his beloved’s summer (by which he means

beautiful, happy years) will never go away, nor will the beloved lose his/her beauty.

But remember what we mentioned in line 4? The summer in real life actually is an "eternal

summer," since it comes back every year for all eternity. Just like we saw with all of the

personifications of nature in the previous lines, we begin to notice here that "thee" and the

"summer’s day" are really quite similar Both can fade away or, depending on how you look

at it, be eternal, and both can be personified. That’s why here, at line 9, the poet switches

direction – both the beloved and nature are threatened mainly by time, and it is only through

this third force (poetry), that they can live on.

It’s also worth picking up on that word "ow’st." That apostrophe might be contracting

"ownest" or "owest," and both work nicely. Either the beloved won’t lose the beauty he/she possesses

("owns"), or won’t have to return the beauty he/she borrowed from nature and now owes back.

These readings both resonate well with line 4, in which the speaker described the summer months as a

"lease," or a temporary ownership that had to be returned.

Lines 11-12

Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade,

When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st;

In another bit of personification (so far we’ve had summer and the sun), the speaker

introduces death. Death, the speaker claims, won’t get a chance to claim the beloved in the

valley of the shadow of death (this death’s shadow idea is from Psalm 23:4), since he/she is

immortal.

The general meaning of line 12 (you’re eternal) is actually easier to see if you read the line

as a metaphor. As a metaphor, "lines to time" definitely refers to a poem, since they are

lines set to a meter, or time.

Here, then, the poet is making two bold claims: first, that his poem is "eternal," and second,

that it nourishes and develops "thee," as it is where he/she is able to "grow."

Now this willingness to discuss the fact that he’s writing a poem within the poem itself is

pretty cool stuff.

One fancy way of describing this kind of artistic tactic is called "breaking the fourth wall." That’s a

metaphor itself, and you can think of it as a stage: in a normal play, any indoor action goes on as if the

front edge of the stage were an imaginary wall. The actors, in other words, are supposed to pretend

they’re in a real world with four walls and no audience watching them. If the actors, however, recogniz

that there’s an audience out there, they’re considered to be "breaking" through that fourth wall, as they

try to do away with the artificiality of pretending they’re just living out a normal life up there on stage.

Well that’s exactly what’s starting to go on here. If you were thinking this poem was a love letter to a

beloved, you can forget it. This is a poem written to be read by an audience, and that audience, by

continuing to read the poem, will try to make the beloved grow into a character, and in turn make

him/her immortal.

file:///C:/Users/Ikram ullah/Downloads/Sonnet 18 Summary.html 3/5

12/30/2019 Sonnet 18 Summary

Lines 13-14

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

The couplet, in the end, is really just a fuller admission of what the speaker points toward

in line 12. He has completely shattered the fourth wall, and (successfully, we should add)

predicted that this poem will continue to be read, and the beloved will continue to be

analyzed and re-analyzed for all time. In other words, by allowing us to try to give life to

"thee" (figuring out who he/she was), the speaker and the poem itself give "thee" life.

In other words: as long as men live and can read, this poem will continue to live, and so

keep "thee" alive.

But let's examine the language more closely. First of all, we’ve got some more

personification: technically, eyes don’t really "see," and poems certainly don’t "live."

Also, it’s worth noting the incredible arrogance here: why should we believe that as long as humankind

exists, this poem will continue to live? Can’t we imagine a world in which every copy of this poem were

burned, and so "thee" would stop living?

And even if people are still reading the poem, what kind of "life" is it that the beloved will

be leading? This definitely doesn’t sound like heaven. The beloved can’t make any choices

for his or her self, isn’t conscious, and can only be recognized as the poet described him or

her.

In fact, we ought to wonder whether it is "thee" who will be alive, or rather the poet’s (very

limited) representation of "thee."

Plus, remember how in line 9 we noted that summer could also be eternal? Well, the end of this poem

kind of makes you wonder. So why, again, is the beloved eternal but not summer? Just like summer, the

beloved is going to fade away in real life, and just like summer, the beloved has been written about and

preserved in a poem. How come, by the end of the poem, it’s only "thee" who lives on and

not nature? Finally, remember how back in line 1 we were already wondering if "thee"

might not just be the speaker’s lover, but also us readers? Well now the speaker has broken

through the fourth wall, and revealed himself as not just a lover, but also as a writer of

poetry.

So check this out (this should be fun for you math kids out there): the speaker is talking to

"thee," and that speaker is actually the poet. Now who do poets write for? That’s right, for

us readers.

So we have three conditions here: the speaker speaks only to "thee," the writer speaks only

to us, and the speaker and writer are the same thing. Doesn’t that mean, then, that "thee," is

the same as "us"?

Trippy.

Frankly, we think that’s a pretty cool reading. Basically, the speaker here is speaking to all

of mankind. All of us feel this pressure of mortality, but here Shakespeare crystallizes that anxiety in a

poem, so that this idea of mankind will live on forever.

The last lines, then, can be read as circular: "so long as mankind lives, mankind will continue to live."

Cool? Too weird? You decide.

In any case, these last two lines hammer home something we suspected from those very first pronouns:

this speaker seems more interested in himself and his abilities as a poet than the qualities of his

addresses.

A Shakespearean Sonnet in Iambic Pentameter

This is a classic Shakespearean sonnet with fourteen lines in very regular iambic pentameter. With the

exception of a couple relatively strong first syllables (and even these are debatable), there are basically

no deviations from the meter. There aren’t even any lines that flow over into the next line – every

single line is end-stopped. There are two quatrains (groups of four lines), followed by a third quatrain

in which the tone of the poem shifts a bit, which is in turn followed by a rhyming couplet (two lines)

that wraps the poem up. The rhyme scheme is ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.

Sonnet 18 Themes

Love

file:///C:/Users/Ikram ullah/Downloads/Sonnet 18 Summary.html 4/5

12/30/2019 Sonnet 18 Summary

Sonnet 18 opens up looking an awful lot like a traditional love poem, but by the end it’s pretty clear

that the poet is much more into himself and the poetry he produces than the beloved he’s addressing.

In fact, at times it seems like he might actually harbor some resentment toward the beloved. So if it is

a love poem it’s to the poet.

Literature and Writing

Like much of Shakespeare’s work, Sonnet 18 is all about writing and expressing one’s self through

language. This is, at its clearest, a poem about the power o the written word over death, fate, and

possibly even love.

Time

The speaker of Sonnet 18 is absolutely xated on fate and mortality, but believes he’s come up with an

effective time machine: poetry. Instead of contemplating a beautiful summer’s day, this speaker can’t

stop thinking about how everything in life is temporary and eeting. No need to fear, though – the hero-

poet steps in and announces that, by artistically representing his beloved, he can save him or her from

the ravages of time. "Time," then, is the intersection of the "Literature and Writing" theme and the

"Man and the Natural World" theme. Man, in the natural world, can’t avoid being subject to time, but

is through literature, the poet argues, that he can free himself.

Man and the Natural World

On one level, Sonnet 18 is clearly concerned with the relationship between man and the eventual,

inescapable death he’ll encounter in nature. On another leve the poet also seems fascinated by the

relationship between seasonal weather and personal, internal "weather" and balance.

file:///C:/Users/Ikram ullah/Downloads/Sonnet 18 Summary.html 5/5

You might also like

- Business Vantage Listening Sample Paper 2 - Full TestDocument8 pagesBusiness Vantage Listening Sample Paper 2 - Full TestDaniel KottnauerNo ratings yet

- Test Unit 4Document4 pagesTest Unit 4PepiLopez100% (2)

- An Analysis of Sonnet 18 by William ShakespeareDocument6 pagesAn Analysis of Sonnet 18 by William ShakespeareHilde LyshaugenNo ratings yet

- Journeys CC Writing Handbook Gr6 PDFDocument6 pagesJourneys CC Writing Handbook Gr6 PDFIkram100% (1)

- Ferrite Transformer Turns Calculation For HighDocument67 pagesFerrite Transformer Turns Calculation For Highjaigodara0% (1)

- Reading For Understanding: Sonnet 18: Analysis Version 1Document9 pagesReading For Understanding: Sonnet 18: Analysis Version 1Trang HoangNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18Document3 pagesSonnet 18mjostinaNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 - NotesDocument10 pagesSonnet 18 - NotesMaryke OberholzerNo ratings yet

- SonnetDocument11 pagesSonnetAndreea BalanNo ratings yet

- Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's DayDocument25 pagesShall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Dayserenan2306No ratings yet

- Shall I Compare You To A Summer Day AnalysisDocument9 pagesShall I Compare You To A Summer Day AnalysisStefNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 - Text and AnalysisDocument4 pagesSonnet 18 - Text and AnalysisNabinur rahmanNo ratings yet

- Sonnet (18) : Shall I Compare TheeDocument28 pagesSonnet (18) : Shall I Compare Theesarah100% (1)

- Sonnet 18 - NotesDocument6 pagesSonnet 18 - NotesFatima KabirNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer 'Document20 pagesSonnet 18 Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer 'mrstoyaNo ratings yet

- Lunaquezada 2017shakespearessonnetanalysisDocument3 pagesLunaquezada 2017shakespearessonnetanalysisapi-345781302No ratings yet

- Shakespeare Famously AsksDocument2 pagesShakespeare Famously AsksNoreen ShahNo ratings yet

- 23953Document9 pages23953bodatiger2002No ratings yet

- Shakespeare BDocument2 pagesShakespeare BGuim PedreroNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Sonnets ExerciseDocument2 pagesShakespeare Sonnets ExerciseKaylee KimNo ratings yet

- English PoemsDocument20 pagesEnglish PoemsShannon SwanepoelNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18Document3 pagesSonnet 18RemyNo ratings yet

- Workshop 2 - Oza 11dDocument3 pagesWorkshop 2 - Oza 11dapi-369154238No ratings yet

- Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Day? (Sonnet 18) : Interpret His Poem Line-By-Line Annotate 5 CommentsDocument3 pagesShall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Day? (Sonnet 18) : Interpret His Poem Line-By-Line Annotate 5 Commentsapi-318781847No ratings yet

- Shall I Compare Thee To A SummerDocument5 pagesShall I Compare Thee To A SummersarahNo ratings yet

- ShakespearesSonnet18PoetryCloseReadingAnalysisFREEBIE 1Document5 pagesShakespearesSonnet18PoetryCloseReadingAnalysisFREEBIE 1Sabrina MabantaNo ratings yet

- 16th C - Renaissance - ShakespeareDocument6 pages16th C - Renaissance - ShakespeareVlindertjeNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Sonnet1Document2 pagesShakespeare Sonnet1Michael GöppelNo ratings yet

- Before We Go Into Summarizing Sonnet 73Document15 pagesBefore We Go Into Summarizing Sonnet 73Camille Llamas EvangelioNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare Sonnet18 HenrietDocument18 pagesShakespeare Sonnet18 Henrietmassaalkadri2006No ratings yet

- Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's DayDocument5 pagesShall I Compare Thee To A Summer's DayFront RowNo ratings yet

- Theme and Summary Mid Fall 23Document5 pagesTheme and Summary Mid Fall 23Jahangir AlamNo ratings yet

- Notes - Shall I Compare Thee by William ShakespeareDocument4 pagesNotes - Shall I Compare Thee by William ShakespeareAYESHA ROSHANNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18: AnalysisDocument3 pagesSonnet 18: AnalysisIrene BaeNo ratings yet

- This Is Forest Primeival The Murmuring Pines and Hemlock Sonnet 18 .. Page 113Document18 pagesThis Is Forest Primeival The Murmuring Pines and Hemlock Sonnet 18 .. Page 113Asmaa Hussain 2No ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 - PowerPointDocument17 pagesSonnet 18 - PowerPointayavuyancoko14No ratings yet

- "Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Day" Is TheDocument2 pages"Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer's Day" Is Theaus_92100% (3)

- Sonnet 18: William Shakespeare Listen To ThisDocument11 pagesSonnet 18: William Shakespeare Listen To ThisIlzeNo ratings yet

- "Sonnet 18" by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)Document2 pages"Sonnet 18" by William Shakespeare (1564-1616)Eniam GeeNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of Sonnet 18 by William ShakespeareDocument3 pagesThe Analysis of Sonnet 18 by William Shakespeareعلي هاشم وزيريNo ratings yet

- Metaphor Poem, Examples of Metaphor Poems by Silvia HartmannDocument7 pagesMetaphor Poem, Examples of Metaphor Poems by Silvia HartmannRajeshNo ratings yet

- Elizabethan PeriodDocument17 pagesElizabethan Periodlea guillermo100% (1)

- Shakespearean Sonnet Writing Made Easy For Year 8MDDocument3 pagesShakespearean Sonnet Writing Made Easy For Year 8MDHana JuiceNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18, Aquino.Document3 pagesSonnet 18, Aquino.Jamaica Ikan AquinoNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 NotesDocument8 pagesSonnet 18 NotesEla SinghNo ratings yet

- Spring and AllDocument4 pagesSpring and AllLovely CitraNo ratings yet

- Unit Three Sonnets OF Shakespeare: ObjectivesDocument11 pagesUnit Three Sonnets OF Shakespeare: ObjectivesEntertainment TimeNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18: Winds" in Them, The Sun ("The Eye of Heaven") Often Shines "Too Hot,"Document3 pagesSonnet 18: Winds" in Them, The Sun ("The Eye of Heaven") Often Shines "Too Hot,"احمد احمدNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18Document2 pagesSonnet 18Ry AbdelmoatyNo ratings yet

- Summary and Full Analysis of Sonnet 18Document2 pagesSummary and Full Analysis of Sonnet 18carmen predut50% (2)

- Lit AnalysisDocument29 pagesLit AnalysishansiNo ratings yet

- Name: Mahnoor Safeer Ch. SAP ID: 26292 Subject: Introduction To Literature Submitted To: Sir AbrarDocument6 pagesName: Mahnoor Safeer Ch. SAP ID: 26292 Subject: Introduction To Literature Submitted To: Sir AbrarMahnoor Ch.No ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 & 116Document6 pagesSonnet 18 & 116adnan100% (2)

- Sonnet 18Document16 pagesSonnet 18Phuong Thao LeNo ratings yet

- How To Use Close Reading MethodDocument3 pagesHow To Use Close Reading MethodDanah Mae AdvinculaNo ratings yet

- Class X English LiteratureDocument46 pagesClass X English Literaturedavidmshoute121No ratings yet

- Poetry-Sonnet 18Document4 pagesPoetry-Sonnet 18Hany FaroukNo ratings yet

- Sonnet 18 ShakespeareDocument2 pagesSonnet 18 ShakespeareMar MartinezNo ratings yet

- Irony Principle StructureDocument4 pagesIrony Principle Structureruttiger57No ratings yet

- The Sun Goes Down PT IIDocument1 pageThe Sun Goes Down PT IILuke Yee100% (1)

- Poetics (Translated by Ingram Bywater with a Preface by Gilbert Murray)From EverandPoetics (Translated by Ingram Bywater with a Preface by Gilbert Murray)No ratings yet

- CHALLAN No.316907828038 CHALLAN No.316907828038 CHALLAN No.316907828038Document1 pageCHALLAN No.316907828038 CHALLAN No.316907828038 CHALLAN No.316907828038IkramNo ratings yet

- Final Tentative Merit List CT (Bps-15) Dir Lower MaleDocument12 pagesFinal Tentative Merit List CT (Bps-15) Dir Lower MaleIkramNo ratings yet

- AbbreviationsDocument63 pagesAbbreviationsIkramNo ratings yet

- Elementary and Secondary Education Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Screening Test For SST Posts (BPS-16) )Document57 pagesElementary and Secondary Education Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Screening Test For SST Posts (BPS-16) )IkramNo ratings yet

- Seniority List of CT, Teachers District Dir Lower. (Corrected Up To 31/12/2020)Document39 pagesSeniority List of CT, Teachers District Dir Lower. (Corrected Up To 31/12/2020)IkramNo ratings yet

- Elementary and Secondary Education Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Screening Test For SST Posts (BPS-16) )Document273 pagesElementary and Secondary Education Department, Govt of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (Screening Test For SST Posts (BPS-16) )IkramNo ratings yet

- Selection Letter Markhor 2021Document1 pageSelection Letter Markhor 2021IkramNo ratings yet

- Chapter # 1: Utmost Happiness, Roy Gives A Critical View of The Dilemma of Deviant Gender andDocument10 pagesChapter # 1: Utmost Happiness, Roy Gives A Critical View of The Dilemma of Deviant Gender andIkramNo ratings yet

- Physics 9Document71 pagesPhysics 9IkramNo ratings yet

- 4 Writing Purposes Guidance1 PDFDocument10 pages4 Writing Purposes Guidance1 PDFIkramNo ratings yet

- Bachelor Degree Essay Autumn - 08 Taawo PDFDocument21 pagesBachelor Degree Essay Autumn - 08 Taawo PDFIkramNo ratings yet

- The Theory of The Sublime From Longinus To Kant: More InformationDocument13 pagesThe Theory of The Sublime From Longinus To Kant: More InformationIkramNo ratings yet

- University of Cape Town: Pride and PrejudiceDocument96 pagesUniversity of Cape Town: Pride and PrejudiceIkramNo ratings yet

- Eighteenth-Century Female Conduct in Jane Austen's: Pride and PrejudiceDocument21 pagesEighteenth-Century Female Conduct in Jane Austen's: Pride and PrejudiceIkramNo ratings yet

- Preliminary: (The Himachal Pradesh Liquor Licence Rules, 1986)Document78 pagesPreliminary: (The Himachal Pradesh Liquor Licence Rules, 1986)Yogesh ThakurNo ratings yet

- Odisha Current AffairsDocument31 pagesOdisha Current AffairsSANGRAM SAHU100% (1)

- Allison Weir - A Study of FulviaDocument168 pagesAllison Weir - A Study of Fulviadumezil3729No ratings yet

- Prac-CAT # 10 TestDocument25 pagesPrac-CAT # 10 Testakash100% (1)

- A Study of Different Corporate Social Responsibility Activities by Tata Group in IndiaDocument48 pagesA Study of Different Corporate Social Responsibility Activities by Tata Group in IndiaJenny VermaNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Philippine TourismDocument11 pagesSyllabus Philippine TourismJohnson FernandezNo ratings yet

- A Study of Factors Affecting Travel Decision Making of TouristsDocument10 pagesA Study of Factors Affecting Travel Decision Making of TouristsAmmarah Rajput ParhiarNo ratings yet

- Instruments NotesDocument116 pagesInstruments Notesprithvih4No ratings yet

- Specification Sheet For Crystallizer Crystallizer Data SheetDocument3 pagesSpecification Sheet For Crystallizer Crystallizer Data SheetAmar RazinNo ratings yet

- Satheeshkumar Dhrithiya (NJC) - 2021-Is1-PA8.1 Tea Bag Activity - HBL (ST)Document6 pagesSatheeshkumar Dhrithiya (NJC) - 2021-Is1-PA8.1 Tea Bag Activity - HBL (ST)weiliNo ratings yet

- Middle Ages - Ged104-A7Document2 pagesMiddle Ages - Ged104-A7KleyrNo ratings yet

- Makale DosyasıDocument18 pagesMakale DosyasıBayram OzerNo ratings yet

- Guide To Getting CloserDocument17 pagesGuide To Getting CloserShaneNo ratings yet

- 56 5 3 ChemistryDocument24 pages56 5 3 ChemistrygettotonnyNo ratings yet

- GST ProjectDocument20 pagesGST ProjectHarshithaNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Accountancy, Business, and Management 2 Activity 2Document1 pageFundamentals of Accountancy, Business, and Management 2 Activity 2Joseph CincoNo ratings yet

- Database Development ProcessDocument8 pagesDatabase Development ProcessdeezNo ratings yet

- Search and Seizure GF CASESDocument7 pagesSearch and Seizure GF CASESAnonymous GMUQYq8No ratings yet

- Psychiatry Question Bank - 65 Multiple Choice Questions On - Psychiatry in India - PDFDocument21 pagesPsychiatry Question Bank - 65 Multiple Choice Questions On - Psychiatry in India - PDFAnkit Gupta44% (9)

- Research Paper On Ergonomics PDFDocument6 pagesResearch Paper On Ergonomics PDFefdwvgt4100% (3)

- How To Install XAMPP For WindowsDocument35 pagesHow To Install XAMPP For Windowsmarlon marcaidaNo ratings yet

- Biography Recount Text: Xi-Toi 2Document7 pagesBiography Recount Text: Xi-Toi 2Adinda GaluhNo ratings yet

- Birla AlokyaDocument18 pagesBirla AlokyaanjaligargisbNo ratings yet

- Thinker 51 Full PDFDocument84 pagesThinker 51 Full PDFNtate MoloiNo ratings yet

- Identify The Controls and Variables Worksheet: Scenario 1Document3 pagesIdentify The Controls and Variables Worksheet: Scenario 1Belen Cid ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Khedive IsmailDocument3 pagesKhedive IsmailAbimbola OyarinuNo ratings yet

- Image Image Image Image: Takeover Buybacks DelistingDocument5 pagesImage Image Image Image: Takeover Buybacks DelistingBhavin SagarNo ratings yet