Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Arbitration - Set 3

Arbitration - Set 3

Uploaded by

Jacquelyn RamosOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Arbitration - Set 3

Arbitration - Set 3

Uploaded by

Jacquelyn RamosCopyright:

Available Formats

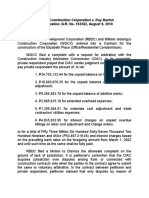

[19] G.R. No.

211504 construction contracts entered into by parties, and whether such disputes arise before or after the

completion of the contracts. Accordingly, the execution of the contracts and the effect of the agreement

FEDERAL BUILDERS, INC., Petitioner vs POWER FACTORS, INC., Respondent to submit to arbitration are different matters, and the signing or non-signing of one does not necessarily

affect the other. In other words, the formalities of the contract have nothing to do with the jurisdiction

Construction Industry Arbitration Commission; Jurisdiction; Under the Construction Industry of the CIAC.

Arbitration Commission Revised Rules of Procedure Governing Construction

Arbitration (CIAC Revised Rules), all that is required for the CIAC to acquire jurisdiction is for the Civil Law; Contracts; A contract does not need to be in writing in order to be obligatory and

parties of any construction contract to agree to submit their dispute to arbitration.—The need to effective unless the law specifically requires so.—Under Article 1318 of the Civil Code, a valid

establish a proper arbitral machinery to settle disputes expeditiously was recognized by the contract should have the following essential elements, namely: (a) consent of the contracting parties;

Government in order to promote and maintain the development of the country’s construction industry. (b) object certain that is the subject matter of the contract; and (c) cause or consideration. Moreover, a

With such recognition came the creation of the CIAC through Executive Order No. 1008 (E.O. No. contract does not need to be in writing in order to be obligatory and effective unless the law

1008), also known as The Construction Industry Arbitration Law. Section 4 of E.O. No. 1008 specifically requires so. Pursuant to Article 1356 and Article 1357 of the Civil Code, contracts shall be

provides: Sec. 4. Jurisdiction.—The CIAC shall have original and exclusive jurisdiction over disputes obligatory in whatever form they may have been entered into, provided that all the essential requisites

arising from, or connected with, contracts entered into by parties involved in construction in the for their validity are present. Indeed, there was a contract between Federal and Power even if the

Philippines, whether the dispute arises before or after the completion of the contract, or after the Contract of Service was unsigned. Such contract was obligatory and binding between them by virtue of

abandonment or breach thereof. These disputes may involve government or private contracts. For the all the essential elements for a valid contract being present.

Board to acquire jurisdiction, the parties to a dispute must agree to submit the same to voluntary

arbitration. x x x Under the CIAC Revised Rules of Procedure Governing Construction Construction Industry Arbitration Commission; Jurisdiction; Although the agreement to submit

Arbitration (CIAC Revised Rules), all that is required for the CIAC to acquire jurisdiction is for the to arbitration has been expressly required to be in writing and signed by the parties therein by Section

parties of any construction contract to agree to submit their dispute to arbitration. Also, Section 2.3 of 4 of Republic Act (RA) No. 876 (Arbitration Law), the requirement is conspicuously absent from the

the CIAC Revised Rules states that the agreement may be reflected in an arbitration clause in their Construction Industry Arbitration Commission (CIAC) Revised Rules, which even expressly allows

contract or by subsequently agreeing to submit their dispute to voluntary arbitration. The such agreement not to be signed by the parties therein.—The agreement contemplated in the

CIAC Revised Rules clarifies, however, that the agreement of the parties to submit their dispute to CIAC Revised Rules to vest jurisdiction of the CIAC over the parties’ dispute is not necessarily an

arbitration need not be signed or be formally agreed upon in the contract because it can also be in the arbitration clause to be contained only in a signed and finalized construction contract. The agreement

form of other modes of communication in writing. could also be in a separate agreement, or any other form of written communication, as long as their

intent to submit their dispute to arbitration is clear. The fact that a contract was signed by both parties

Same; Same; Executive Order (EO) No. 1008 emphasizes that the modes of voluntary dispute has nothing to do with the jurisdiction of the CIAC, and this is the explanation why the CIAC Revised

resolution like arbitration are always preferred because they settle disputes in a speedy and amicable Rules itself expressly provides that the written communication or agreement need not be signed by the

manner.—The liberal application of procedural rules as to the form by which the agreement is parties. Although the agreement to submit to arbitration has been expressly required to be in writing

embodied is the objective of the CIAC Revised Rules. Such liberality conforms to the letter and spirit and signed by the parties therein by Section 4 of Republic Act No. 876 (Arbitration Law), the

of E.O. No. 1008 itself which emphasizes that the modes of voluntary dispute resolution like requirement is conspicuously absent from the CIAC Revised Rules, which even expressly allows such

arbitration are always preferred because they settle disputes in a speedy and amicable manner. They agreement not to be signed by the parties therein. Brushing aside the obvious contractual agreement in

likewise help in alleviating or unclogging the judicial dockets. Verily, E.O. No. 1008 recognizes that this case warranting the submission to arbitration is surely a step backward. Consistent with the policy

the expeditious resolution of construction disputes will promote a healthy partnership between the of encouraging alternative dispute resolution methods, therefore, any doubt should be resolved in favor

Government and the private sector as well as aid in the continuous growth of the country considering of arbitration. In this connection, the CA correctly observed that the act of Atty. Albano in manifesting

that the construction industry provides employment to a large segment of the national labor force aside that Federal had agreed to the form of arbitration was unnecessary and inconsequential considering the

from its being a leading contributor to the gross national product. recognition of the value of the Contract of Service despite its being an unsigned draft.

Same; Same; Construction Disputes; Section 2.1, Rule 2 of the Construction Industry Arbitration DECISION

Commission (CIAC) Revised Rules particularly specifies that the CIAC has original and exclusive

jurisdiction over construction disputes, whether such disputes arise from or are merely connected BERSAMIN, J.:

with the construction contracts entered into by parties, and whether such disputes

arise before or after the completion of the contracts.—Worthy to note is that the jurisdiction of the An agreement to submit to voluntary arbitration for purposes of vesting jurisdiction over a

CIAC is over the dispute, not over the contract between the parties. Section 2.1, Rule 2 of the construction dispute in the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission (CIAC) need not be

CIAC Revised Rules particularly specifies that the CIAC has original and exclusive jurisdiction contained in the construction contract, or be signed by the parties. It is enough that the

over construction disputes, whether such disputes arise from or are merely connected with the agreement be in writing.

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 1 of 41

The Case Federal did not thereafter participate in the proceedings until the CIAC rendered the Final

Award dated May 12, 2010,9 disposing:

Federal Builders Inc. (Federal) appeals to reverse the decision promulgated on August 12,

2013,1 whereby the Court of Appeals (CA) affirmed the adverse decision rendered on May In summary: Respondent Federal Builders, Inc. is hereby ordered to pay claimant Power

12, 2010 by the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission (CIAC) with modification of the Factors, Inc. the following sums:

total amount awarded.2

1. Unpaid balance on the original contract ₱4,276,614.75;

Antecedents

2. Unpaid balance on change order nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, & 9 3,006,970.32;

Federal was the general contractor of the Bullion Mall under a construction agreement with 3. Interest to May 13, 2010 1,686,149.94;

Bullion Investment and Development Corporation (BIDC). In 2004, Federal engaged

respondent Power Factors Inc. (Power) as its subcontractor for the electric works at the 4. Attorney's Fees 250,000.00;

Bullion Mall and the Precinct Building for ₱l8,000,000.00. 3

5. Cost of Arbitration 149,503.86;

On February 19, 2008, Power sent a demand letter to Federal claiming the unpaid amount of ₱9,369 ,238.87

₱ll,444,658.97 for work done by Power for the Bullion Mall and the Precinct Building. Federal

replied that its outstanding balance under the original contract only amounted to

₱1,641,513.94, and that the demand for payment for work done by Power after June 21,

2005 should be addressed directly to BIDC. 4 Nonetheless, Power made several demands on The foregoing amount shall earn legal interest at the rate of 6% per annum from the date of

Federal to no avail. this Final Award until this award becomes final and executory, Claimant shall then be entitled

to 12% per annum until the entire amount is fully satisfied by Respondent.

On October 29, 2009, Power filed a request for arbitration in the CIAC invoking the arbitration

clause of the Contract of Service reading as follows: Federal appealed the award to the CA insisting that the CIAC had no jurisdiction to hear and

decide the case; and that the amounts thereby awarded to Power lacked legal and factual

15. ARBITRATION COMMITTEE - All disputes, controversies or differences, which may arise bases.

between the parties herein, out of or in relation to or in connection with this Agreement, or for

breach thereof shall be settled by the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission (CIAC) On August 12, 2013, the CA affirmed the CIAC's decision with modification as to the amounts

which shall have original and exclusive jurisdiction over the aforementioned disputes. 5 due to Power,10 viz.:

On November 20, 2009, Atty. Vivencio Albano, the counsel of Federal, submitted a letter to WHEREFORE, the CIAC Final Award dated 12 May 20l0 in CIAC Case No. 31-2009 is

the CIAC manifesting that Federal agreed to arbitration and sought an extension of 15 days hereby AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION. As modified, FEDERAL BUILDERS, INC. is

to file its answer, which request the CIAC granted. ordered to pay POWER FACTORS, INC. the following:

On December 16, 2009, Atty. Albano filed his withdrawal of appearance stating that Federal 1. Unpaid balance on the original contract ₱4,276,614.75;

had meanwhile engaged another counsel.6

2. Unpaid balance on change orders 2,864,113.32;

Federal, represented by new counsel (Domingo, Dizon, Leonardo and Rodillas Law Office), 3. Attorney's Fees 250,000.00;

moved to dismiss the case on the ground that CIAC had no jurisdiction over the case

inasmuch as the Contract of Service between Federal and Power had been a mere draft that 4. Cost of Arbitration 149,503.86;

was never finalized or signed by the parties. Federal contended that in the absence of the

agreement for arbitration, the CIAC had no jurisdiction to hear and decide the case. 7

The interest to be imposed on the net award (unpaid balance on the original contract and

change order) amounting to P.7, 140,728.07 awarded to POWER FACTORS INC. shall be

On February 8, 2010, the CIAC issued an order setting the case for hearing, and directing six (6%) per annum, reckoned from 4 July 2006 until this Decision becomes final and

that Federal's motion to dismiss be resolved after the reception of evidence of the parties. 8 executory. Further, the total award due to POWER FACTORS INC. shall be subjected to an

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 2 of 41

interest of twelve percent (12%) per annum computed from the time this judgment becomes Under the CIAC Revised Rules of Procedure Governing Construction

final and executory, until full satisfaction. SO ORDERED. 11 Arbitration (CIAC Revised Rules), all that is required for the CIAC to acquire jurisdiction is for

the parties of any construction contract to agree to submit their dispute to arbitration. 15 Also,

Anent jurisdiction, the CA explained that the CIAC Revised Rules of Procedure stated that Section 2.3 of the CIAC Revised

the agreement to arbitrate need not be signed by the parties; that the consent to submit to

voluntary arbitration was not necessary in view of the arbitration clause contained in the Rules states that the agreement may be reflected in an arbitration clause in their contract or

Contract of Service; and that Federal's contention that its former counsel's act of manifesting by subsequently agreeing to submit their dispute to voluntary arbitration. The CIAC Revised

its consent to the arbitration stipulated in the draft Contract of Service did not bind it was Rules clarifies, however, that the agreement of the parties to submit their dispute to

inconsequential on the issue of jurisdiction.12 arbitration need not be signed or be formally agreed upon in the contract because it can also

be in the form of other modes of communication in writing, viz.:

Concerning the amounts awarded, the CA opined that the CIAC should not have allowed the

increase based on labor-cost escalation because of the absence of the agreement between RULE 4 - EFFECT OF AGREEMENT TO ARBITRATE

the parties on such escalation and because there was no authorization in writing allowing the

adjustment or increase in the cost of materials and labor. 13 SECTION 4.1. Submission to CIAC jurisdiction - An arbitration clause in a construction

contract or a submission to arbitration of a construction dispute shall be deemed an

After the CA denied Federal's motion for reconsideration on February 19, 2004, 14 Federal has agreement to submit an existing or future controversy to CIAC jurisdiction, notwithstanding

come to the Court on appeal. the reference to a different arbitration institution or arbitral body in such contract or

submission.

Issue

4.1.1 When a contract contains a clause for the submission of a future controversy to

The issues to be resolved are: (a) whether the CA erred in upholding CIAC's jurisdiction over arbitration, it is not necessary for the parties to enter into a submission agreement before the

the present case; and (b) whether the CA erred in holding that Federal was liable to pay Claimant may invoke the jurisdiction of CIAC.

Power the amount of ₱7,140,728.07.

4.1.2 An arbitration agreement or a submission to arbitration shall be in writing, but it need

Ruling of the Court not be signed by the parties, as long as the intent is clear that the parties agree to submit a

present or future controversy arising from a construction contract to arbitration. It may be in

the form of exchange of letters sent by post or by telefax, telexes, telegrams, electronic mail

The appeal is bereft of merit.

or any other mode of communication.

1.The parties had an effective agreement to submit to voluntary arbitration; hence, the CIAC

The liberal application of procedural rules as to the form by which the agreement is embodied

had jurisdiction

is the objective of the CIAC Revised Rules. Such liberality conforms to the letter and spirit of

E.O. No. 1008 itself which emphasizes that the modes of voluntary dispute resolution like

The need to establish a proper arbitral machinery to settle disputes expeditiously was arbitration are always preferred because they settle disputes in a speedy and amicable

recognized by the Government in order to promote and maintain the development of the manner. They likewise help in alleviating or unclogging the judicial dockets. Verily, E.O. No.

country's construction industry. With such recognition came the creation of the CIAC through 1008 recognizes that the expeditious resolution of construction disputes will promote a

Executive Order No. 1008 (E.O. No. 1008), also known as The Construction Industry healthy partnership between the Government and the private sector as well as aid in the

Arbitration Law. Section 4 of E.O. No. 1008 provides: continuous growth of the country considering that the construction industry provides

employment to a large segment of the national labor force aside from its being a leading

Sec. 4. Jurisdiction. - The CIAC shall have original and exclusive jurisdiction over disputes contributor to the gross national product.16

arising from, or connected with, contracts entered into by parties involved in construction in

the Philippines, whether the dispute arises before or after the completion of the contract, or Worthy to note is that the jurisdiction of the CIAC is over the dispute, not over the contract

after the abandonment or breach thereof. These disputes may involve government or private between the parties.17 Section 2.1, Rule 2 of the CIAC Revised Rules particularly specifies

contracts. For the Board to acquire jurisdiction, the parties to a dispute must agree to submit that the CIAC has original and exclusive jurisdiction over construction disputes, whether

the same to voluntary arbitration. x x x such disputes arise from or are merely connected with the construction contracts entered into

by parties, and whether such disputes arise before or after the completion of the contracts.

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 3 of 41

Accordingly, the execution of the contracts and the effect of the agreement to submit to the Contract of Service that it wanted 30% as the downpayment. Even so, Power did not

arbitration are different matters, and the signing or non-signing of one does not necessarily modify anything else in the draft, and returned the draft to Federal after signing it. It was

affect the other. In other words, the formalities of the contract have nothing to do with the Federal that did not sign the draft because it was not amenable to the amount as modified by

jurisdiction of the CIAC. Power. It is notable that the arbitration clause written in the draft of Federal was unchallenged

by the parties until their dispute arose.

Federal contends that there was no mutual consent and no meeting of the minds between it

and Power as to the operation and binding effect of the arbitration clause because they had Moreover, Federal asserted the original contract to support its claim against Power. If Federal

rejected the draft service contract. would insist that the remaining amount due to Power was only ₱l,641,513.94 based on the

original contract,21 it was really inconsistent for Federal to rely on the draft when it is

The contention of Federal deserves no consideration. beneficial to its side, and to reject its efficacy and existence just to relieve itself from the

CIAC's unfavorable decision.

Under Article 1318 of the Civil Code, a valid contract should have the following essential

elements, namely: (a) consent of the contracting parties; The agreement contemplated in the CIAC Revised Rules to vest jurisdiction of the CIAC over

the parties' dispute is not necessarily an arbitration clause to be contained only in a signed

and finalized construction contract. The agreement could also be in a separate agreement, or

(b) object certain that is the subject matter of the contract; and (c) cause or consideration.

any other form of written communication, as long as their intent to submit their dispute to

Moreover, a contract does not need to be in writing in order to be obligatory and effective

arbitration is clear. The fact that a contract was signed by both parties has nothing to do with

unless the law specifically requires so.

the jurisdiction of the CIAC, and this is the explanation why the CIAC Revised Rules itself

expressly provides that the written communication or agreement need not be signed by the

Pursuant to Article 135618 and Article 135719 of the Civil Code, contracts shall be obligatory in parties.

whatever form they may have been entered into, provided that all the essential requisites for

their validity are present. Indeed, there was a contract between Federal and Power even if

Although the agreement to submit to arbitration has been expressly required to be in writing

the Contract of Service was unsigned. Such contract was obligatory and binding between

and signed by the parties therein by Section 4 22 of Republic Act No. 876 (Arbitration

them by virtue of all the essential elements for a valid contract being present.

Law),23 the requirement is conspicuously absent from the CIAC Revised Rules, which even

expressly allows such agreement not to be signed by the parties therein. 24 Brushing aside the

It clearly appears that the works promised to be done by Power were already executed albeit obvious contractual agreement in this case warranting the submission to arbitration is surely

still incomplete; that Federal paid Power ₱l ,000,000.00 representing the originally proposed a step backward.25 Consistent with the policy of encouraging alternative dispute resolution

downpayment, and the latter accepted the payment; and that the subject of their dispute methods, therefore, any doubt should be resolved in favor of arbitration. 26 In this connection,

concerned only the amounts still due to Power. The records further show that Federal the CA correctly observed that the act of Atty. Albano in manifesting that Federal had agreed

admitted having drafted the Contract of Services containing the following clause on to the form of arbitration was unnecessary and inconsequential considering the recognition of

submission to arbitration, to wit: the value of the Contract of Service despite its being an unsigned draft.

15. ARBITRATION COMMITTEE -All disputes, controversies or differences, which may arise 2. Amounts as modified by the CA are correct

between the Parties herein, out of or in relation to or in connection with this Agreement, or for

breach thereof shall be settled by the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission (CIAC)

We find no reversible error regarding the amounts as modified by the CA. Power did not

which shall have original and exclusive jurisdiction over the aforementioned disputes. 20

sufficiently establish that the change or increase of the cost of materials and labor was to be

separately determined and approved by both parties as provided under Article 1724 of

With the parties having no issues on the provisions or parts of the Contract of Service other the Civil Code. As such, Federal should not be held liable for the labor cost escalation.

than that pertaining to the downpayment that Federal was supposed to pay, Federal could not

validly insist on the lack of a contract in order to defeat the jurisdiction of the CIAC. As earlier

WHEREFORE, the Court AFFIRMS the decision promulgated on August 12, 2013;

pointed out, the CIAC Revised Rules specifically allows any written mode of communication

and ORDERS the petitioner to pay the costs of suit.

to show the parties' intent or agreement to submit to arbitration their present or future

disputes arising from or connected with their contract.

SO ORDERED.

The CIAC and the CA both found that the parties had disagreed on the amount of the

downpayment.1âwphi1 On its part, Power indicated after receiving and reviewing the draft of

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 4 of 41

[20] G.R. No. 184295 July 30, 2014 PERLAS-BERNABE, J.:

NATIONAL TRANSMISSION CORPORATION, Petitioner, vs. ALPHAOMEGA Assailed in this petition for review on certiorari 1 are the Decision2 dated April 8, 2008 and the

INTEGRATED CORPORATION, Respondent. Resolution3 dated August 27, 2008 of the Court of Appeals (CA) in CA-G.R. SP No. 99454

affirming with modification the Final Award4 of the Construction Industry Arbitration

Remedial Law; Civil Procedure; Section 1, Rule 45 of the Rules of Court provides that a petition Commission (CIAC) Arbitral Tribunal in favor of respondent Alphaomega Integrated

for review on certiorari under the said rule, as in this case, “shall raise only questions of law which Corporation (AIC) by increasing petitioner National· Transmission Corporation's (TRANSCO)

must be distinctly set forth.”—TRANSCO seeks through this petition a recalibration of the liability from Pl 7,495,117.44 to Pl 8,896,673.31.

evidence presented before the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal, insisting that AIC is not entitled to any

damages not only because it had previously waived all claims for standby fees in case of project delays The Facts

but had eventually failed to perform the workable portions of the projects. This is evidently a factual

question which cannot be the proper subject of the present petition. Section 1, Rule 45 of the Rules of AIC, a duly licensed transmission line contractor, participated in the public biddings

Court provides that a petition for review on certiorari under the said rule, as in this case, “shall raise conducted by TRANSCO and was awarded six ( 6) government construction projects,

only questions of law which must be distinctly set forth.” Thus, absent any of the existing exceptions namely: (a) Contract .for the Construction & Erection of Batangas Transmission

impelling the contrary, the Court is, as general rule, precluded from delving on factual determinations, Reinforcement Project Schedule III (BTRP Schedule III Project); (b) Contract for the

as what TRANSCO essentially seeks in this case. Construction & Erection of Batangas Transmission Reinforcement Project Schedule I (BTRP

Schedule I Project); (c) Contract for the Construction,Erection & Installation of 230 KV and 69

Same; Same; It is well-settled that findings of fact of quasi-judicial bodies, which have acquired KV S/S Equipment and Various Facilities for Makban Substation under the Batangas

expertise because their jurisdiction is confined to specific matters, are generally accorded not only Transmission Reinforcement Project (Schedule II) (Makban Substation Project); (d) Contract

respect, but also finality, especially when affirmed by the Court of Appeals (CA).—The Court finds no for the Construction, Erection & Installation of 138 & 69 KV S/S Equipment for Bacolod

reason to disturb the factual findings of the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal on the matter of AIC’s entitlement Substation under the Negros III-Panay III Substation Projects (Schedule II) (Bacolod

to damages which the CA affirmed as being well supported by evidence and properly referred to in the Substation Project); (e) Contract for the Construction, Erection & Installation of 138 & 69 KV

record. It is well-settled that findings of fact of quasi-judicial bodies, which have acquired expertise Substation Equipment for the New Bunawan Switching Station Project (Bunawan Substation

because their jurisdiction is confined to specific matters, are generally accorded not only respect, but Project); and (f) Contract for the Construction, Erection & Installation of 138 and 69 KV

also finality, especially when affirmed by the CA. The CIAC possesses that required expertise in the Substation Equipment for Quiot Substation Project (Quiot Substation Project). 5

field of construction arbitration and the factual findings of its construction arbitrators are final and

conclusive, not reviewable by this Court on appeal. In the course of the performance ofthe contracts, AIC encountered difficulties and incurred

losses allegedly due to TRANSCO’s breach of their contracts, prompting it to surrender the

Same; Same; It is well-settled that no relief can be granted a party who does not appeal and that projects to TRANSCO under protest. In accordance with an express stipulation in the

a party who did not appeal the decision may not obtain any affirmative relief from the appellate court contracts that disagreements shall be settled by the parties through arbitration before the

other than what he had obtained from the lower court, if any, whose decision is brought up on appeal. CIAC, AIC submitted a request for arbitration before the CIAC on August 28, 2006, and,

—It must be emphasized that the petition for review before the CA was filed by TRANSCO. AIC thereafter, filed an Amended Complaint against TRANSCO alleging that the latter breached

never elevated before the courts the matter concerning the discrepancy between the amount of the the contracts by its failure to: (a) furnish the required Detailed Engineering; (b) arrange a well-

award stated in the body of the Final Award and the total award shown in its dispositive portion. The established right-of-way to the project areas; (c) secure the necessary permits and

issue was touched upon by the CA only after AIC raised the same through its Comment (With Motion clearances from the concerned local government units (LGUs); (d) ensure a continuous

to Acknowledge Actual Amount of Award) to TRANSCO’s petition for review. The CA should not supply of construction materials; and (e) carry out AIC’s requests for power shut down. The

have modified the amount of the award to favor AIC because it is well-settled that no relief can be aforementioned transgressions resultedin protracted delays and contract suspensions for

granted a party who does not appeal and that a party who did not appeal the decision may not obtain each project,6 as follows:

any affirmative relief from the appellate court other than what he had obtained from the lower court, if

any, whose decision is brought up on appeal. The disposition, as stated in the fallo of the CIAC

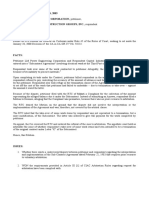

Arbitral Tribunal’s Final Award, should therefore stand. Contract Original Duration of Transco- Percentage (%) of Original

Contract Approved Suspension Contract Duration

DECISION Duration and/or Extensions

1) BTRP Schedule III 560 days 711 days 127%

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 5 of 41

2) BTRP Schedule I 270 days 406 days 170% obligated to furnish under the terms of the contract, among others. 14 The dispositive portion of

the Arbitral Tribunal’s Final Award reads:

3) Makban Substation 365 days 452 days 124%

WHEREFORE, Respondent, National Transmission Corporation [TRANSCO] is hereby

4) Bacolod Substation 360 days 289 days 80% ordered to pay Claimant, Alphaomega Integrated Corporation, the following sums:

5) Bunawan Substation 330 days 130 days 39%

(a) For BTRP Schedule III - ₱6,423,496.67

6) Quiot Substation 300 days 131 days 44%

(b) For BTRP Schedule I - 5,214,202.30

7

2119 days (c) For Makban Substation - 3,075,870.95

(d) For Bacolod Substation - 1,362,936.77

AIC prayed for judgment declaring all six (6) contracts rescinded and ordering TRANSCO to

pay, in addition to what had already been paid under the contracts, moral damages, (e) For Bunawan Substation - 820,481.72

exemplary damages, and attorney’s fees at ₱100,000.00 each, and a total of ₱40,201,467.19

(f) For Quiot Substation - 598, 129.03

as actual and compensatory damages.8

TOTAL ₱17,495,117.44

TRANSCO, for its part, contended that: (a) it had conducted Detailed Engineering prior to the

conduct of the bidding; and (b) it had obtained the necessary government permits and

Each Party shall shoulder its own cost of arbitration.

endorsements from the affected LGUs. It asserted that AIC was guilty of frontloading– that

is,collecting the bulk of the contract price for work accomplished at the early stages of the

project and then abandoning the later stagesof the project which has a lower contract price 9 – The foregoing amount of ₱17,495,117.44 shall earn interest at the rate of six percent (6%)

and that it disregarded the workable portions of the projects not affected by the lack of per annum from the date of promulgation of this Final Award until it becomes final and

supplies and drawings. TRANSCO further argued that AIC was estopped from asking for executory. Thereafter, the Final Award, including accrued interest, shall earn interest at the

standby fees to cover its overhead expenses during project suspensions considering that the rate of 12% per annum until the entire amount due is fully paid. 15 (Emphasis supplied)

delays, such as the unresolved right-of-way issues and non-availability of materials, were

factors already covered by the time extensions and suspensions of work allowed under the Unconvinced, TRANSCO instituted a petition for review16 with the CA.

contracts.10

Before filing its comment17 to the petition, AIC moved for the issuance of a writ of

11

On April 18, 2007, the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal rendered its Final Award in CIAC Case No. 21- execution,18 not for the amount of 17,495,117.44 awarded in the Final Award, but for the

2006 ordering the payment of actual and compensatory damages which AIC would not have increased amount of 18,967,318.49.19 It sought correction of the discrepancies between the

suffered had it not been for the project delays attributable to TRANSCO. It found ample amount of the award appearing in the dispositive portion 20 and the body of the Final

evidence to support the claim for the increase in subcontract cost in BTRP Schedule I, as well Award.21 The Arbitral Tribunal, however, denied AIC’s motion, holding that while the CIAC

as such items of cost as house and yard rentals, electric bills, water bills, and maintained Revised Rules of Procedure Governing Construction Arbitration (CIAC Rules) would have

personnel, but disallowed the claims for communications bills, maintenance costs for idle allowed the correction of the Final Award for evident miscalculation of figures, typographical

equipment, finance charges, and materials cost increases. 12 According to the Arbitral or arithmetical errors, AIC failed to file its motionfor the purpose within the time limitation of 15

Tribunal, even if AIC itself made the requests for contract time extensions, this did not bar its days from its receipt of the Final Award.22

claim for damages as a result of project delayssince a contrary ruling would allow TRANSCO

to profit from its own negligence and leave AIC to suffer serious material prejudice as a direct The CA Ruling

consequence of that negligence leaving it without any remedy at law. 13 The Arbitral Tribunal

upheld AIC’s right to rescind the contracts in accordancewith Resolution No. 018-2004 of the In the Decision23 dated April 8, 2008, the CAaffirmed the Arbitral Tribunal’s factual findings

Government Procurement Policy Board (GPPB), which explicitly gives the contractor the right that TRANSCOfailed to exercise due diligence in resolving the problems regarding the right-

to terminate the contract if the works are completely stopped for a continuous period of at of-way and the lack of materials before undertaking the bidding process and entering into the

least 60 calendar days, through no fault of its own, due to the failure of the procuring entity to contracts with AIC.24 It found no merit in TRANSCO’s allegation that AIC refused to perform

deliver within a reasonable time, supplied materials, right-of-way, or other items that it is the remaining workable portions of the projects not affected by problems of right-of-way,

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 6 of 41

shutdowns, supplies and drawings, firstly, because the certificates ofaccomplishments issued and computed by the CIAC and the CA. Generally, this would be a question of fact that this

by TRANSCO in the course of project implementation signifying its satisfaction with AIC’s Court would not delve upon. Imperial v. Jauciansuggests as much. There, the Court ruled that

performance negate such claim and, secondly, because all the orders issued by TRANSCO the computation of outstanding obligation is a question of fact:

suspended the contracts not only in part but in their entirety, thus, permitting no work activity

at all during such periods.25 Arguing that she had already fully paid the loan x x x, petitioner alleges that the two lower

courts misappreciated the facts when they ruled that she still had an outstanding balance of

The CA upheld the Arbitral Tribunal’s Final Award as having been sufficiently established by ₱208,430.

evidence but modified the total amount of the award after noting a supposed mathematical

error in the computation. Setting aside TRANSCO’s objections, it ruled that when a case is This issue involves a question of fact. Such question exists when a doubt or difference arises

brought to a superior court on appeal every aspect of the case is thrown open for as to the truth or the falsehood of alleged facts; and when there is need for a calibration of the

review,26 hence, the subject error could be rectified. The CA held that the correct amount of evidence, considering mainly the credibility of witnesses and the existence and the relevancy

the award should be ₱18,896,673.31, and not ₱17,495,117.44 as stated in the Arbitral of specific surrounding circumstances, their relation to each other and to the whole, and the

Tribunal’s Final Award.27 Dissatisfied, TRANSCO moved for reconsideration 28 but was, probabilities of the situation. (G.R. No. 149004, April 14, 2004, 427 SCRA 517, 523-524.)

however, denied by the CA in a Resolution 29 dated August 27, 2008, hence, the instant

petition. The rule, however, precluding the Court from delving on the factual determinations of the CA,

admits of several exceptions. In Fuentes v. Court of Appeals, we held that the findings of

The Issues Before the Court facts of the CA, which are generally deemed conclusive, may admit review by the Court in

any of the following instances, among others:

The essential issues for the Court’s consideration are whether or not the CA erred (a) in

affirming the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal’s findings that AIC was entitled to its claims for damages (1) when the factual findings of the [CA] and the trial court are contradictory;

as a result of project delays, and (b) in increasing the total amount of compensation awarded

in favor of AIC despite the latter’s failure to raise the allegedly erroneous computation of the (2) when the findings are grounded entirely on speculation, surmises, or conjectures;

award before the CIAC in a timely manner, that is, within fifteen (15) days from receipt of the

Final Award as provided under Section 17.1 of the CIAC Rules.

(3) when the inference made bythe [CA] from its findings of fact is manifestly

mistaken, absurd, or impossible;

The Court’s Ruling

(4) when there is grave abuse of discretion in the appreciation of facts;

TRANSCO seeks through this petition a recalibration of the evidencepresented before the

CIAC ArbitralTribunal, insisting that AIC is not entitled to any damages not only because it

had previously waived all claims for standby fees in case of project delays but had eventually (5) when the [CA], in making its findings, goes beyond the issues of the case, and

failed to perform the workable portions of the projects. This is evidently a factual question such findings are contrary to the admissions of both appellant and appellee;

which cannot be the proper subject of the present petition. Section 1, Rule 45 of the Rules of

Court provides that a petition for review on certiorariunder the said rule, as in this case, "shall (6) when the judgment of the [CA] is premised on a misapprehension of facts;

raise only questions of law which must be distinctly set forth." Thus, absent any of the existing

exceptions impelling the contrary, the Court is, as a general rule, precluded from delving on (7) when the [CA] fails to notice certain relevant facts which, if properly considered,

factual determinations, as what TRANSCO essentially seeks in this case. Similar to the will justify a different conclusion;

foregoing is the Court’s ruling in Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction Co., Ltd. v.

Dynamic Planners and Construction Corp.,30 the pertinent portions ofwhich are hereunder (8) when the findings of fact are themselves conflicting;

quoted:

(9) when the findings of fact are conclusions without citation of the specific evidence

Dynamic maintains that the issues Hanjin raised in its petitions are factual in nature and are, on which they are based; and

therefore, not proper subject of review under Section 1 of Rule 45, prescribing that a petition

under the said rule, like the one at bench, "shall raise only questions of law which must be

(10) when the findings of fact of the [CA] are premised on the absence of evidence

distinctly set forth." Dynamic’s contention is valid topoint as, indeed, the matters raised by

but such findings are contradicted by the evidence on record. (G.R. No. 109849,

Hanjin are factual, revolving as they do on the entitlement of Dynamic to the awards granted

February 26, 1997, 268 SCRA 703, 709)

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 7 of 41

Significantly, jurisprudence teaches that mathematical computations as well as the propriety limitation under the CIAC Rules.36 Clearly, having failed to move for the correction of the Final

of the arbitral awards are factual determinations. And just as significant is that the factual Award and, thereafter, having opted to file insteada motion for execution of the arbitral

findings of the CIAC and CA—in each separate appealed decisions—practically dovetail with tribunal’s unopposed and uncorrected Final Award, AIC cannot now question against the

each other. The perceptible essential difference, at least insofar as the CIAC’s Final Award correctness of the CIAC’s disposition. Notably, while there is jurisprudential authority stating

and the CA Decision in CA-G.R. SP No. 86641 are concerned, rests merely on mathematical that "[a] clerical error in the judgment appealed from may be corrected by the appellate

computations or adjustments of baseline amounts which the CIAC may have inadvertently court,"37 the application of that rule cannot be made in this case considering that the CIAC

utilized.31 (Emphases and underscoring supplied) Rules provides for a specific procedureto deal with particular errors involving "[a]n evident

miscalculation of figures, a typographical or arithmetical error." Indeed, the rule iswell

In any case, the Court finds no reason to disturb the factual findings of the CIAC Arbitral entrenched: Specialis derogat generali. When two rules apply to a particular case, thatwhich

Tribunal on the matter of AIC’s entitlement to damages which the CA affirmed as being well was specially designed for the said case must prevail over the other. 38

supported by evidence and properly referred to in the record. It is well-settled that findings of

fact of quasijudicial bodies, which have acquired expertise because their jurisdiction is Furthermore, it must be emphasized that the petition for review before the CA was filed by

confined to specific matters, are generally accorded not only respect, but also finality, TRANSCO.39 AIC never elevated before the courts the matter concerning the discrepancy

especially when affirmed by the CA. 32 The CIAC possesses that required expertise in the field between the amount of the award stated in the body of the Final Award and the total award

of construction arbitration and the factual findings of its construction arbitrators are final and shown in its dispositive portion. The issue was touched upon bythe CA only after AIC raised

conclusive, not reviewable by this Court on appeal.33 the same through its Comment (With Motion to Acknowledge Actual Amount of Award) 40 to

TRANSCO’s petition for review. The CA should not have modified the amount of the award to

While the CA correctly affirmed infull the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal’s factual determinations, it favor AIC because it is well-settled that no relief can be granted a party who does not

improperly modified the amount of the award in favor of AIC, which modification did not appeal41 and that a party who did not appeal the decision may not obtain any affirmative relief

observe the proper procedure for the correction of an evident miscalculation of figures, from the appellate court other than what he had obtained from the lower court, if any, whose

including typographical or arithmetical errors, in the arbitral award. Section 17.1 of the CIAC decision is brought up on appeal. 42 The disposition, as stated in the fallo of the CIAC Arbitral

Rules mandates the filing of a motion for the foregoing purpose within fifteen (15) days from Tribunal's Final Award, should therefore stand.43

receipt thereof, viz.:

WHEREFORE, the petition is PARTLY GRANTED. The Decision dated April 8, 2008 of the

Section 17.1 Motion for correction of final award– Any of the parties may file a motion for Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 99454 is hereby AFFIRMED with MODIFICATION. The

correction of the Final Award within fifteen (15) days from receipt thereof upon any of the compensation awarded in favor of Alphaomega Integrated Corporation in the amount of

following grounds: ₱17,495,117.44, as shown in the fallo of the ·construction Industry Arbitration Commission's

Final Award dated April 18, 2007, stands.

a. An evident miscalculation of figures, a typographical or arithmetical error; (Emphasis

supplied) SO ORDERED.

xxxx

Failure to file said motion would consequentlyrender the award final and executory under

Section 18. 1 of the same rules, viz.:

Section 18.1 Execution of Award – A final arbitral award shall become executory upon the

lapse of fifteen (15) days from receipt thereof by the parties.1âwphi1

AIC admitted that it had ample time to file a motion for correction of the Final Award but

claimed to have purposely sat on its right to seek correction supposedly as a strategic move

against TRANSCO34 and, instead, filed with the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal on June 13, 2007 a

"Motion for Issuance of Writ of Execution for the Total Amount of 18,967,318.49 as Embodied

in the Final Award."35 The Arbitral Tribunal eventually denied AIC’s aforesaid motion for

execution because, despite its merit, the Arbitral Tribunal could not disregard the time-

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 8 of 41

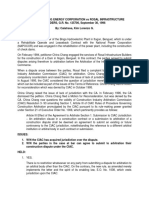

[21] G.R. No. 192725, August 09, 2017 Same; The most recent jurisprudence maintains that the Construction Industry Arbitration

Commission (CIAC) is a quasi-judicial body.—The most recent jurisprudence maintains that the CIAC

CE CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION, PETITIONER, VS. ARANETA CENTER INC., is a quasi-judicial body. This Court’s November 23, 2016 Decision in Fruehauf Electronics v.

RESPONDENT. Technology Electronics Assembly and Management Pacific, 810 SCRA 280, distinguished

construction arbitration, as well as voluntary arbitration pursuant to Article 219(14) of the Labor Code,

Construction Industry Arbitration Commission; The Construction Industry Arbitration from commercial arbitration. It ruled that commercial arbitral tribunals are not quasi-judicial agencies,

Commission (CIAC) was a creation of Executive Order (EO) No. 1008, otherwise known as the as they are purely ad hoc bodies operating through contractual consent and as they intend to serve

Construction Industry Arbitration Law.—The Construction Industry Arbitration Commission was a private, proprietary interests. In contrast, voluntary arbitration under the Labor Code and construction

creation of Executive Order No. 1008, otherwise known as the Construction Industry Arbitration Law. arbitration operate through the statutorily vested jurisdiction of government instrumentalities that exist

At inception, it was under the administrative supervision of the Philippine Domestic Construction independently of the will of contracting parties and to which these parties submit.

Board which, in turn, was an implementing agency of the Construction Industry Authority of the

Philippines (CIAP). The CIAP is presently attached to the Department of Trade and Industry. Same; Appeals; Petitions for Review; Rule 43, Section 1 explicitly lists Construction Industry

Arbitration Commission (CIAC) as among the quasi-judicial agencies covered by Rule 43. Section 3

Same; Construction Disputes; Alternative Dispute Resolution; Alternative Dispute Resolution indicates that appeals through Petitions for Review under Rule 43 are to “be taken to the Court of

Act of 2004; Arbitration of construction disputes through the Construction Industry Arbitration Appeals (CA) . . . whether the appeal involves questions of fact, of law, or mixed questions of fact and

Commission (CIAC) was formally incorporated into the general statutory framework on alternative law.”—Rule 43 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure standardizes appeals from quasi-judicial

dispute resolution through Republic Act No. 9285, the Alternative Dispute Resolution Act of 2004 agencies. Rule 43, Section 1 explicitly lists CIAC as among the quasi-judicial agencies covered by

(ADR Law).—Republic Act No. 9184 or the Government Procurement Reform Act, enacted on Rule 43. Section 3 indicates that appeals through Petitions for Review under Rule 43 are to “be taken

January 10, 2003, explicitly recognized and confirmed the competence of the CIAC: Section to the Court of Appeals . . . whether the appeal involves questions of fact, of law, or mixed questions of

59. Arbitration.—Any and all disputes arising from the implementation of a contract covered by this fact and law.”

Act shall be submitted to arbitration in the Philippines according to the provisions of Republic Act No.

876, otherwise known as the “Arbitration Law”: Provided, however, That, disputes that are within the Same; Same; Arbitral Tribunals; The Supreme Court’s (SC’s) primordial inclination must be to

competence of the Construction Industry Arbitration Commission to resolve shall be referred uphold the factual findings of arbitral tribunals.—Consistent with this restrictive approach, this Court

thereto. The process of arbitration shall be incorporated as a provision in the contract that will be is duty-bound to be extremely watchful and to ensure that an appeal does not become an ingenious

executed pursuant to the provisions of this Act: Provided, That by mutual agreement, the parties may means for undermining the integrity of arbitration or for conveniently setting aside the conclusions

agree in writing to resort to alternative modes of dispute resolution. Arbitration of construction arbitral processes make. An appeal is not an artifice for the parties to undermine the process they

disputes through the CIAC was formally incorporated into the general statutory framework on voluntarily elected to engage in. To prevent this Court from being a party to such perversion, this

alternative dispute resolution through Republic Act No. 9285, the Alternative Dispute Resolution Act Court’s primordial inclination must be to uphold the factual findings of arbitral tribunals.

of 2004 (ADR Law). Chapter 6, Section 34 of ADR Law made specific reference to the Construction

Industry Arbitration Law, while Section 35 confirmed the CIAC’s jurisdiction. Arbitral Tribunals; Common sense dictates that by the parties’ voluntary submission, they

acknowledge that an arbitral tribunal constituted under the Construction Industry Arbitration

Same; Construction; Words and Phrases; The Construction Industry Arbitration Commission Commission (CIAC) has full competence to rule on the dispute presented to it.—ACI and

(CIAC) has the state’s confidence concerning the entire technical expanse of construction, defined in CECON voluntarily submitted themselves to the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal’s jurisdiction. The

jurisprudence as “referring to all on-site works on buildings or altering structures, from land contending parties’ own volition is at the inception of every construction arbitration proceeding.

clearance through completion including excavation, erection and assembly and installation of Common sense dictates that by the parties’ voluntary submission, they acknowledge that an arbitral

components and equipment.”—The CIAC does not only serve the interest of speedy dispute resolution, tribunal constituted under the CIAC has full competence to rule on the dispute presented to it. They

it also facilitates authoritative dispute resolution. Its authority proceeds not only from juridical concede this not only with respect to the literal issues recited in their terms of reference, as ACI

legitimacy but equally from technical expertise. The creation of a special adjudicatory body for suggests, but also with respect to their necessary incidents. Accordingly, in delineating the authority of

construction disputes presupposes distinctive and nuanced competence on matters that are conceded to arbitrators, the CIAC Rules of Procedure speak not only of the literally recited issues but also of

be outside the innate expertise of regular courts and adjudicatory bodies concerned with other “related matters”: SECTION 21.3.

specialized fields. The CIAC has the state’s confidence concerning the entire technical expanse of

construction, defined in jurisprudence as “referring to all on-site works on buildings or altering Extent of power of arbitrator.—The Arbitral Tribunal shall decide only such issues and related

structures, from land clearance through completion including excavation, erection and assembly and matters as are submitted to them for adjudication. They have no power to add, to subtract from,

installation of components and equipment.” modify, or amend any of the terms of the contract or any supplementary agreement thereto, or any rule,

regulation or policy promulgated by the CIAC. To otherwise be puritanical about cognizable issues

would be to cripple CIAC arbitral tribunals. It would potentially be to condone the parties’ efforts at

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 9 of 41

tying the hands of tribunals through circuitous, trivial recitals that fail to address the complete extent of articulated in Articles 1370 to 1379 of the Civil Code. In so doing, a tribunal does not conjure

their claims and which are ultimately ineffectual in dispensing an exhaustive and dependable its own contractual terms and force them upon the parties.

resolution. Construction arbitration is not a game of guile which may be left to ingenious textual or

technical acrobatics, but an endeavor to ascertain the truth and to dispense justice “by every and all In addressing an iniquitous predicament of a contractor that actually renders services but

reasonable means without regard to technicalities of law or procedure.” remains inadequately compensated, arbitral tribunals of the Construction Industry Arbitration

Commission (CIAC) enjoy a wide latitude consistent with their technical expertise and the

Construction Contracts; Jurisprudence has settled that even in cases where parties enter into arbitral process' inherent inclination to afford the most exhaustive means for dispute

contracts which do not strictly conform to standard formalities or to the typifying provisions of resolution. When their awards become the subject of judicial review, courts must defer to the

nominate contracts, when one renders services to another, the latter must compensate the former for factual findings borne by arbitral tribunals' technical expertise and irreplaceable experience of

the reasonable value of the services rendered.—Jurisprudence has settled that even in cases where presiding over the arbitral process. Exceptions may be availing but only in instances when the

parties enter into contracts which do not strictly conform to standard formalities or to the typifying integrity of the arbitral tribunal itself has been put in jeopardy. These grounds are more

provisions of nominate contracts, when one renders services to another, the latter must compensate the exceptional than those which are regularly sanctioned in Rule 45 petitions.

former for the reasonable value of the services rendered. This amount shall be fixed by a court. This is

a matter so basic, this Court has once characterized it as one that “springs from the fountain of good This resolves a Petition for Review on Certiorari[1] under Rule 45 of the 1997 Rules of Civil

conscience”: As early as 1903, in Perez v. Pomar, this Court ruled that where one has rendered Procedure, praying that the assailed April 28, 2008 Decision[2] and July 1, 2010 Amended

services to another, and these services are accepted by the latter, in the absence of proof that the Decision[3] of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. SP No. 96834 be reversed and set aside. It

service was rendered gratuitously, it is but just that he should pay a reasonable remuneration therefore likewise prays that the October 25, 2006 Decision[4] of the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal be

because “it is a well known principle of law, that no one should be permitted to enrich himself to the reinstated.

damage of another.” Similary in 1914, this Court declared that in this jurisdiction, even in the absence

of statute, “. . . under the general principle that one person may not enrich himself at the expense of The CIAC Arbitral Tribunal October 25, 2006 Decision awarded a total sum of

another, a judgment creditor would not be permitted to retain the purchase price of land sold as the P217,428,155.75 in favor of petitioner CE Construction Corporation (CECON). This sum

property of the judgment debtor after it has been made to appear that the judgment debtor had no title represented adjustments in unit costs plus interest, variance in take-out costs, change orders,

to the land and that the purchaser had failed to secure title thereto.” The foregoing equitable principle time extensions, attendance fees, contractor-supplied equipment, and costs of arbitration.

which springs from the fountain of good conscience are applicable to the case at bar. Consistent with This amount was net of the countervailing awards in favor of respondent Araneta Center, Inc.

the Construction Industry Arbitration Law’s declared policy, the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal was (ACI), for defective and incomplete works, permits, licenses and other advances.[5]

specifically charged with “ascertain[ing] the facts in each case by every and all reasonable means.” In

discharging its task, it was permitted to even transcend technical rules on admissibility of evidence. The assailed Court of Appeals April 28, 2008 Decision modified the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal

October 25, 2006 Decision by awarding a net amount of P82,758,358.80 in favor of CECON.

Same; Article 1724 demands two (2) requisites in order that a price may become immutable: [6] The Court of Appeals July 1, 2010 Amended Decision adjusted this amount to

first, there must be an actual, stipulated price; and second, plans and specifications must have P93,896,335.71.

definitely been agreed upon.—Article 1724 demands two (2) requisites in order that a price may

become immutable: first, there must be an actual, stipulated price; and second, plans and specifications Petitioner CECON was a construction contractor, which, for more than 25 years, had been

must have definitely been agreed upon. Neither requisite avails in this case. Yet again, ACI is begging doing business with respondent ACI, the developer of Araneta Center, Cubao, Quezon City.

the question. It is precisely the crux of the controversy that no price has been set. Article 1724 does not [8]

work to entrench a disputed price and make it sacrosanct. Moreover, it was ACI which thrust itself

upon a situation where no plans and specifications were immediately agreed upon and from which no In June 2002, ACI sent invitations to different construction companies, including CECON, for

deviation could be made. It was ACI, not CECON, which made, revised, and deviated from designs them to bid on a project identified as "Package #4 Structure/Mechanical, Electrical, and

and specifications. Plumbing/Finishes (excluding Part A Substructure)," a part of its redevelopment plan for

Araneta Center Complex.[9] The project would eventually be the Gateway Mall. As described

by ACI, "[t]he Project involved the design, coordination, construction and completion of all

DECISION architectural and structural portions of Part B of the Works[;] and the construction of the

LEONEN, J.: architectural and structural portions of Part A of the Works known as Package 4 of the

Araneta Center Redevelopment Project."[10]

A tribunal confronted not only with ambiguous contractual terms but also with the total

absence of an instrument which definitively articulates the contracting parties' agreement As part of its invitation to prospective contractors, ACI furnished bidders with Tender

does not act in excess of jurisdiction when it employs aids in interpretation, such as those Documents, consisting of:

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 10 of 41

Volume I: Tender Invitation, Project Description, Instructions to Tenderers, Form of Tender, for only ninety (90) days, or only until 29 November 2002." This tender proposed a total of

Dayworks, Preliminaries and General Requirements, and Conditions of Contract; 400 days, or until January 10, 2004, for the implementation and completion of the project.

Volume II: Technical Specifications for the Architectural, Structural, Mechanical, Plumbing, CECON offered the lowest tender amount. However, ACI did not award the project to any

Fire Protection and Electrical Works; and bidder, even as the validity of CECON's proposal lapsed on November 29, 2002. ACI only

subsequently informed CECON that the contract was being awarded to it. ACI elected to

Addenda Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 4 relating to modifications to portions of the Tender Documents. inform CECON verbally and not in writing.

[11]

In a phone call on December 7, 2002, ACI instructed CECON to proceed with excavation

The Tender Documents described the project's contract sum to be a "lump sum" or "lump works on the project. ACI, however, was unable to deliver to CECON the entire project site.

sum fixed price" and restricted cost adjustments, as follows: Only half, identified as the Malvar-to-Roxas portion, was immediately available. The other

half, identified as the Roxas to-Coliseum portion, was delivered only about five (5) months

6 TYPE OF CONTRACT later.

6.1 This is a Lump Sum Contract and the price is a fixed price not subject to measurement or As the details of the project had yet to be finalized, ACI and CECON pursued further

recalculation should the actual quantities of work and materials differ from any estimate negotiations. ACI and CECON subsequently agreed to include in the project the construction

available at the time of contracting, except in regard to Cost-Bearing Changes which may be of an office tower atop the portion identified as Part A of the project. This escalated CECON's

ordered by the Owner which shall be valued under the terms of the Contract in accordance project cost to P1,582,810,525.00.

with the Schedule of Rates, and with regard to the Value Engineering Proposals under

Clause 27. The Contract Sum shall not be adjusted for changes in the cost of labour, After further negotiations, the project cost was again adjusted to P1,613,615,244.00. Still

materials or other matters.[12] later, CECON extended to ACI a P73,615,244.00 discount, thereby"reducing its offered

project cost to P1,540,000.00.

TENDER AND CONTRACT

Despite these developments, ACI still failed to formally award the project to CECON. The

Fixed Price Contract parties had yet to execute a formal contract. This prompted CECON to write a letter to ACI,

dated December 27, 2002,[20] emphasizing that the project cost quoted to ACI was "based

The Contract Sum payable to the Contactor is a Lump Sum Fixed Price and will not be upon the prices prevailing at December 26, 2002" price levels.

subject to adjustment, save only where expressly provided for within the Contract Documents

and the Form of Agreement. By January 2003 and with the project yet to be formally awarded, the prices of steel products

had increased by 5% and of cement by P5.00 per bag. On January 8, 2003, CECON again

The Contract Sum shall not be subject to any adjustment "in respect of rise and fall in the cost wrote ACI notifying it of these increasing costs and specifically stating that further delays may

of materials[,] labor, plant, equipment, exchange rates or any other matters affecting the cost affect the contract sum.

of execution of Contract, save only where expressly provided for within the Contract

Documents or the Form of Agreement. Still without a formal award, CECON again wrote to ACI on January 21, 2003[23] indicating

cost and time adjustments to its original proposal. Specifically, it referred to an 11.52%

The Contract Sum shall further not be subject to any change in subsequent legislation, which increase for the cost of steel products, totalling P24,921,418.00 for the project; a P5.00

causes additional or reduced costs to the Contractor.[13] increase per bag of cement, totalling P3,698,540.00 for the project; and costs incurred

because of changes to the project's structural framing, totalling P26,011,460.00. The contract

The bidders' proposals for the project were submitted on August 30, 2002. These were based sum, therefore, needed to be increased to P1,594,631,418.00. CECON also specifically

on "design and construct" bidding.[14] stated that its tender relating to these adjusted prices were valid only until January 31, 2003,

as further price changes may be forthcoming. CECON emphasized that its steel supplier had

CECON submitted its bid, indicating a tender amount of P1,449,089,174.00. This amount was actually already advised it of a forthcoming 10% increase in steel prices by the first week of

inclusive of "both the act of designing the building and executing its construction." Its bid and February 2003. CECON further impressed upon ACI the need to adjust the 400 days allotted

tender were based on schematic drawings, i.e., conceptual designs and suppositions culled for the completion of the project.

from ACI's Tender Documents. CECON's proposal "specifically stated that its bid was valid

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 11 of 41

On February 4, 2003, ACI delivered to CECON the initial tranche of its down payment for the First, on January 30, 2003, ACI issued Change Order No. 11,[37] which shifted the portion

project. By then, prices of steel had been noted to have increased by 24% from December identified as Part B of the project from reinforced concrete framing to structural steel framing.

2002 prices. This increase was validated by ACI. Deleting the cost for reinforced concrete framing meant removing P380,560,300.00 from the

contract sum. Nevertheless, replacing reinforced concrete framing with structural steel

Subsequently, ACI informed CECON that it was taking upon itself the design component of framing "entailed substitute cost of Php217,585,000, an additional Php44,281,100 for the

the project, removing from CECON's scope of work the task of coming up with designs. additional steel frames due to revisions, and another Php1,950,000 for the additional pylon."

On June 2, 2003, ACI finally wrote a letter[27] to CECON indicating its acceptance of Second, instead of leaving it to CECON, ACI opted to purchase on its own certain pieces of

CECON's August 30, 2002 tender for an adjusted contract sum of P1,540,000.00 only: equipment-elevators, escalators, chillers, generator sets, indoor substations, cooling towers,

pumps, and tanks-which were to be installed in the project. This entailed "take-out costs"; that

Araneta Center, Inc. (ACI) hereby accepts the C-E Construction Corporation (CEC) tender is, the value of these pieces of equipment needed to be removed from the total amount due

dated August 30, 2002, submitted to ACI in the adjusted sum of One Billion Five Hundred to CECON. ACI considered a sum totalling P251,443,749.00 to have been removed from the

Forty Million Pesos Only (P1,540,000,000.00), which sum includes all additionally quoted and contract sum due to CECON. This amount of P251,443,749.00 was broken down, as follows:

accepted items within this acceptance letter and attachments, Appendix A, consisting of one

(1) page, and Appendix B, consisting of seven (7) pages plus attachments, which sum of One (a) For elevators/escalators, PhP106,000,000;

Billion Five Hundred Forty Million Pesos Only (P1,540,000,000.00) is inclusive of any

Government Customs Duty and Taxes including Value Added Tax (VAT) and Expanded (b) For Chillers, PhP41,152,900;

Value Added Tax (EVAD, and which sum is hereinafter referred to as the Contract Sum.[28]

(c) For Generator Sets, PhP53,040,000;

Item 4, Appendix B of this acceptance letter explicitly recognized that "all design except

support to excavation sites, is now by ACI."[29] It thereby confirmed that the parties were not (d) For Indoor Substation, PhP23,024,150;

bound by a design-and-construct agreement, as initially contemplated in ACI's June 2002

invitation, but by a construct-only agreement. The letter stated that "[CECON] acknowledge[s] (e) For Cooling Towers, PhP5,472,809; and

that a binding contract is now existing."[30] However, consistent with ACI's admitted changes,

it also expressed ACI's corresponding undertaking: "This notwithstanding, formal contract (f) For Pumps and Tanks, PhP22,753,890.[39]

documents embodying these positions will shortly be prepared and forwarded to you for

execution. CECON avers that in removing the sum of P251,443,749.00, ACI "simply deleted the amount

in the cost breakdown corresponding to each of the items taken out in the contract

Despite ACI's undertaking, no formal contract documents were delivered to CECON or documents."[40] ACI thereby disregarded that the corresponding stipulated costs pertained

otherwise executed between ACI and CECON. not only to the acquisition cost of these pieces of equipment but also to so-called "builder's

works" and other costs relating to their preparation for and installation in the project. Finding it

As it assumed the design aspect of the project, ACI issued to CECON the construction unjust to be performing auxiliary services practically for free, CECON proposed a reduction in

drawings for the project. Unlike schematics, these drawings specified "the kind of work to be the take-out costs claimed by ACI. It instead claimed P26,892,019.00 by way of

done and the kind of material to be used."[33] CECON laments, however, that "ACI issued compensation for the work that it rendered.

the construction drawings in piece-meal fashion at times of its own choosing."[34] From the

commencement of CECON's engagement until its turnover of the project to ACI, ACI issued With many changes to the project and ACI's delays in delivering drawings and specifications,

some 1,675 construction drawings. CECON emphasized that many of these drawings were CECON increasingly found itself unable to complete the project on January 10, 2004. It noted

partial and frequently pertained to revisions of prior items of work.[35] Of these drawings, that it had to file a total of 15 Requests for Time Extension from June 10, 2003 to December

more than 600 were issued by ACI well after the intended completion date of January 10, 15, 2003, all of which ACI failed to timely act on.

2004: Drawing No. 1040 was issued on January 12, 2004, and the latest, Drawing No. 1675,

was issued on November 26, 2004. Exasperated, CECON served notice upon ACI that it would avail of arbitration. On January

29, 2004, it filed with the CIAC its Request for Adjudication.[43] It prayed that a total sum of

Apart from shifting its arrangement with CECON from design-and-construct to construct only, P183,910,176.92 representing adjusted project costs be awarded in its favor.[44]

ACI introduced other changes to its arrangements with CECON. CECON underscored two (2)

of the most notable of these changes which impelled it to seek legal relief. On March 31, 2004, CECON and ACI filed before the CIAC a Joint Manifestation[45]

indicating that some issues between them had already been settled. Proceedings before the

₯Construction Industry Arbitration Commission- Set III Page 12 of 41

CIAC were then suspended to enable CECON and ACI to arrive at an amicable settlement. total of P229,223,318.69 to CECON, inclusive of the costs of arbitration. It completely denied

[46] On October 14, 2004, ACI filed a motion before the CIAC noting that it has validated ACI's claims for liquidated damages, but awarded to ACI a total of P11,795,162.93 on

P85,000,000.00 of the total amount claimed by CECON. It prayed for more time to arrive at a account of defective and rectification works, as well as permits, licenses, and other

settlement. advances.Thus, the net amount due to CECON was determined to be P217,428,155.75.

In the meantime, CECON completed the project and turned over Gateway Mall to ACI.[48] It The CIAC Arbitral Tribunal noted that while ACI's initial invitation to bidders was for a lump-

had its blessing on November 26, 2004. sum design-and-construct arrangement, the way that events actually unfolded clearly

indicated a shift to an arrangement where the designs were contingent upon ACI itself.

As negotiations seemed futile, on December 29, 2004, CECON filed with the CIAC a Motion Considering that the premise for CECON's August 30, 2002 lump-sum offer of P1,540,000.00

to Proceed with arbitration proceedings. ACI filed an Opposition. was no longer availing, CECON was no longer bound by its representations in respect of that

lump-sum amount. It may then claim cost adjustments totalling P16,429,630.74, as well as

After its Opposition was denied, ACI filed its Answer dated January 26, 2005.[51] It attributed values accruing to the various change orders issued by ACI, totalling P159,827,046.94.

liability for delays to CECON and sought to recover counterclaims totalling P180,752 297.84.

This amount covered liquidated damages for CECON's supposed delays, the cost of The CIAC Arbitral Tribunal found ACI liable for the delays. This entitled CECON to extended

defective works which had to be rectified, the cost of procuring permits and licenses, and overhead costs and the ensuing extension cost of its Contractor's All Risk Insurance. For

ACI's other advances. these costs, the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal awarded CECON the total amount of P16,289,623.08.

As it was ACI that was liable for the delays, the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal ruled that ACI was not

On February 8, 2005, ACI filed a Manifestation and Motion seeking the CIAC's clearance for entitled to liquidated damages.

the parties to enter into mediation. Mediation was then instituted with Atty. Sedfrey Ordonez

acting as mediator. The CIAC Arbitral Tribunal ruled that CECON was entitled to a differential in take out costs

representing builder's works and related costs with respect to the equipment purchased by

After mediation failed, an arbitral tribunal was constituted through a March 16, 2005 Order of ACI. This differential cost was in the amount of P15,332,091.47.[63] The CIAC Arbitral

the CIAC. It was to be composed of Dr. Ernesto S. De Castro, who acted as Chairperson with Tribunal further noted that while ACI initially opted to purchase by itself pumps, tanks, and

Engr. Reynaldo T. Viray and Atty. James S. Villafranca as members. cooling towers and removed these from CECON's scope of work, it subsequently elected to

still obtain these through CECON. Considering that the corresponding amount deducted as

ACI filed a Motion for Reconsideration of the CIAC March 16, 2005 Order. This was denied in take-out costs did not encompass the overhead costs and profits under day work, which

the Order dated March 30, 2005. should have accrued to CECON because of these equipment, the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal

ruled that CECON was entitled to 18% day work rate or a total of P21,267,908.00.

In the Order dated April 1, 2005, the CIAC Arbitral Tribunal set the preliminary conference on