Professional Documents

Culture Documents

When Being - Deaf - Is - Centered - D - Deaf - Women

When Being - Deaf - Is - Centered - D - Deaf - Women

Uploaded by

Ramon SalCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Information Technology Project Management 9th Edition Schwalbe Solutions ManualDocument9 pagesInformation Technology Project Management 9th Edition Schwalbe Solutions Manualdonnahauz03vm100% (40)

- Martin Brammah - The Betta Bible - The Art and Science of Keeping BettasDocument368 pagesMartin Brammah - The Betta Bible - The Art and Science of Keeping Bettasvicnit100% (2)

- Edu 604 Issue InvestigationDocument9 pagesEdu 604 Issue Investigationapi-367685949No ratings yet

- Civil 3DDocument3 pagesCivil 3Dcristiano68071No ratings yet

- Caribbean Spaces: Reflective Essays/ Creative-Theoretical CirculationsDocument18 pagesCaribbean Spaces: Reflective Essays/ Creative-Theoretical CirculationsJose Valdivia100% (1)

- Linguistic Prejudice, Linguistic Privilege: Public ForumDocument5 pagesLinguistic Prejudice, Linguistic Privilege: Public ForumFitraAshariNo ratings yet

- Anya, Uju African Americans in World Language Study 2020Document16 pagesAnya, Uju African Americans in World Language Study 2020YomeritodetolucaNo ratings yet

- Memoir Memory and MasteryDocument9 pagesMemoir Memory and Masteryapi-344972038No ratings yet

- Diary Entry 7Document2 pagesDiary Entry 7Yeisson CardenasNo ratings yet

- Spoken Soul: The Language of Black Imagination and Reality: The Educational Forum October 2005Document12 pagesSpoken Soul: The Language of Black Imagination and Reality: The Educational Forum October 2005Tomás CallegariNo ratings yet

- Anya Ngay - Students' Coping Mechanisms On Accent Stigma's Impacts On Their Social Well-Being in A Multicultural SchoolDocument31 pagesAnya Ngay - Students' Coping Mechanisms On Accent Stigma's Impacts On Their Social Well-Being in A Multicultural School11009416No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Ed. Essay - Moira McCallum FinalDocument8 pagesAboriginal Ed. Essay - Moira McCallum Finalmmccallum88No ratings yet

- Eisner Creating A Narrative of Success FinalDocument19 pagesEisner Creating A Narrative of Success Finalapi-239857905No ratings yet

- Race, Racism, and Racialization in Sign Language Research and Deaf StudiesDocument2 pagesRace, Racism, and Racialization in Sign Language Research and Deaf StudiesDavid PlayerNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument6 pagesEssayapi-532442874No ratings yet

- Case Study NewDocument4 pagesCase Study Newapi-466313157No ratings yet

- Deaf FinalDocument10 pagesDeaf Finalapi-272576022No ratings yet

- Bab 2 AinunDocument12 pagesBab 2 AinunsitiNo ratings yet

- Cultural and CommunicationDocument5 pagesCultural and Communicationcliffe 103No ratings yet

- Diary of Chinese International Students in New Zealand: WavesDocument18 pagesDiary of Chinese International Students in New Zealand: WavesJj JanzbizzareNo ratings yet

- Assess Sociological Explanations of Ethnic Differences in Educational AchievementDocument3 pagesAssess Sociological Explanations of Ethnic Differences in Educational Achievementfeven multagoNo ratings yet

- 92 4 VillenasDocument9 pages92 4 VillenasRoberto MartinezNo ratings yet

- Rachael-Lyn Anderson EDED11458 LetterDocument14 pagesRachael-Lyn Anderson EDED11458 LetterRachael-Lyn AndersonNo ratings yet

- Final DraftDocument37 pagesFinal Draftapi-282441285No ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity and Language Socialization in The Early YearsDocument2 pagesCultural Diversity and Language Socialization in The Early Yearsvaleria feyenNo ratings yet

- Sembianteetal 2020Document26 pagesSembianteetal 2020AmaniNo ratings yet

- Axalan Lesson 7Document49 pagesAxalan Lesson 7Del Rosario, Ace TalainNo ratings yet

- Deaf Immigrant Education in America - Final DraftDocument12 pagesDeaf Immigrant Education in America - Final Draftapi-652934259No ratings yet

- Diversity and Social Justice Assignment OneDocument10 pagesDiversity and Social Justice Assignment Oneapi-357666701No ratings yet

- Bernal 2002 Critical Race Theory Latino Critical Theory and Critical Raced Gendered Epistemologies Recognizing StudentsDocument22 pagesBernal 2002 Critical Race Theory Latino Critical Theory and Critical Raced Gendered Epistemologies Recognizing StudentsJayden JenkinsNo ratings yet

- Developmental Language Disorders in A Pluralistic Society: Chapter ObjectivesDocument32 pagesDevelopmental Language Disorders in A Pluralistic Society: Chapter ObjectivesClaudia F de la ArceNo ratings yet

- The Connection Between Language and Identity: Carolyn Hart EST650 / Fulbright-Hays Group Project Abroad Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesThe Connection Between Language and Identity: Carolyn Hart EST650 / Fulbright-Hays Group Project Abroad Literature Reviewcarolynhart_415No ratings yet

- Oral and Literature Traditions Among Black Americans Living in PovertyDocument14 pagesOral and Literature Traditions Among Black Americans Living in PovertyAnonymous GQXLOjndTbNo ratings yet

- Deaf Mental Health: Enhancing Linguistically and Culturally Appropriate Clinical PracticeDocument20 pagesDeaf Mental Health: Enhancing Linguistically and Culturally Appropriate Clinical PracticeMay FuentesNo ratings yet

- PracticumreflectionpaperDocument5 pagesPracticumreflectionpaperapi-284114354No ratings yet

- Becoming Black: Rap and Hip-Hop, Race, Gender, Identity, and The Politics of ESL LearningDocument13 pagesBecoming Black: Rap and Hip-Hop, Race, Gender, Identity, and The Politics of ESL LearningJaypee de GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Lovelace and Wheeler 2006 PDFDocument8 pagesLovelace and Wheeler 2006 PDFShawn Lee BryanNo ratings yet

- Garcia Fernandez Dissertation 2014Document340 pagesGarcia Fernandez Dissertation 2014Viridiana MadridNo ratings yet

- Research Immigrant ChildDocument11 pagesResearch Immigrant Childapi-394744987No ratings yet

- Test 2Document24 pagesTest 2jaysonfredmarinNo ratings yet

- CSCC PaperDocument6 pagesCSCC Paperapi-341016087No ratings yet

- Reflection On The Impacts of Shifting Cultural MdenizDocument4 pagesReflection On The Impacts of Shifting Cultural Mdenizapi-273275279No ratings yet

- EssayDocument4 pagesEssayapi-427326490No ratings yet

- Reproducing Racism Schooling and Race in Highland BoliviaDocument21 pagesReproducing Racism Schooling and Race in Highland BoliviasterrazasvNo ratings yet

- Deaf Culture 101: Ivy Velez Intensive Care Coordinator Walden School Wraparound Program The Learning Center For The DeafDocument25 pagesDeaf Culture 101: Ivy Velez Intensive Care Coordinator Walden School Wraparound Program The Learning Center For The DeafMirza AryantoNo ratings yet

- Article Review Assignment RevisedDocument7 pagesArticle Review Assignment RevisedAhmad AliNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 DSJLDocument10 pagesAssignment 1 DSJLapi-321112414No ratings yet

- Heritage Language and Ethnic Identity: A Case Study of Korean-American College StudentsDocument16 pagesHeritage Language and Ethnic Identity: A Case Study of Korean-American College StudentsAnonymous nH6Plc8yNo ratings yet

- Acculturation Article MG 515Document38 pagesAcculturation Article MG 515ByKiaro18No ratings yet

- Cross Cultural Understanding: Taught By: Adelce Ferdinandus, S. PD., M. ADocument4 pagesCross Cultural Understanding: Taught By: Adelce Ferdinandus, S. PD., M. ANick GaryNo ratings yet

- Culture 3 (Definition)Document30 pagesCulture 3 (Definition)Javed IqbalNo ratings yet

- Cert III PaperDocument14 pagesCert III Paperapi-275168580No ratings yet

- Journal Table 1Document4 pagesJournal Table 1api-353261593No ratings yet

- Language and Religion As Key Markers of EthnicityDocument12 pagesLanguage and Religion As Key Markers of EthnicityTrishala SweenarainNo ratings yet

- حديثDocument14 pagesحديثALI MOHAMMEDNo ratings yet

- EAMES 2019 Imperialism's Effects On Lanugage Loss and Endangerment Maliseet-Passamaquoddy and Wopanaak Language CommunitiesDocument132 pagesEAMES 2019 Imperialism's Effects On Lanugage Loss and Endangerment Maliseet-Passamaquoddy and Wopanaak Language Communitiesabigail sessionsNo ratings yet

- Resource Used: Anita Woolfolk's Educational Psychology: Ninth EditionDocument3 pagesResource Used: Anita Woolfolk's Educational Psychology: Ninth EditionJerinz Del RosarioNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-4Document57 pagesChapter 1-4Lj YouNo ratings yet

- Keeping Culture in Mind Entry Unit (May30 2014)Document11 pagesKeeping Culture in Mind Entry Unit (May30 2014)Yvonne Hynson100% (1)

- Lack of Participation in Urban High School Music Ensembles and How To Rectify ItDocument13 pagesLack of Participation in Urban High School Music Ensembles and How To Rectify ItDaniel WhitworthNo ratings yet

- EDUC5429 EssayDocument11 pagesEDUC5429 EssayRuiqi.ngNo ratings yet

- Language Learning and The Relation To CultureDocument15 pagesLanguage Learning and The Relation To Cultureapi-347946759No ratings yet

- Ethnicity and Educational Attainment Notes - Sociology A-LevelsDocument7 pagesEthnicity and Educational Attainment Notes - Sociology A-LevelsbasitcontentNo ratings yet

- Good God but You Smart!: Language Prejudice and Upwardly Mobile CajunsFrom EverandGood God but You Smart!: Language Prejudice and Upwardly Mobile CajunsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Signall A European Partnership Approach PDFDocument10 pagesSignall A European Partnership Approach PDFRamon SalNo ratings yet

- Listening To Phonocentrism With - Deaf - EyeDocument15 pagesListening To Phonocentrism With - Deaf - EyeRamon SalNo ratings yet

- A Narrative Exploration of Educational e PDFDocument187 pagesA Narrative Exploration of Educational e PDFRamon SalNo ratings yet

- Signing Communities The SAGE Deaf StudiesDocument6 pagesSigning Communities The SAGE Deaf StudiesRamon SalNo ratings yet

- Wi System Fixing GuidanceDocument8 pagesWi System Fixing GuidanceRossanoNo ratings yet

- Mastering PHDocument12 pagesMastering PHDaniela PresiadoNo ratings yet

- Review Module-Reinforced Concrete Design (RCD Columns-USD)Document1 pageReview Module-Reinforced Concrete Design (RCD Columns-USD)Joseph Lanto100% (1)

- Bangalore Institute of TechnologyDocument4 pagesBangalore Institute of TechnologygirijaNo ratings yet

- Placas DialogicDocument53 pagesPlacas DialogicJULIOLIVANo ratings yet

- GNU Solfege 3.9.4 User ManualDocument66 pagesGNU Solfege 3.9.4 User Manualinfobits0% (1)

- What Is Marshall Mix DesignDocument5 pagesWhat Is Marshall Mix DesignBlance AlbertNo ratings yet

- Product and Application Description Technical Data: WarningDocument2 pagesProduct and Application Description Technical Data: WarningVishal SuryawaniNo ratings yet

- Hedland Scratch Band Tunebook (Dedicated To Colleen)Document219 pagesHedland Scratch Band Tunebook (Dedicated To Colleen)api-3836032100% (6)

- Resources: Circular Economy and Its Comparison With 14 Other Business Sustainability MovementsDocument19 pagesResources: Circular Economy and Its Comparison With 14 Other Business Sustainability MovementsTrần Thị Mai AnhNo ratings yet

- Cross Word PuzzleDocument1 pageCross Word PuzzleDominion EkpukNo ratings yet

- Turbo HD DVR V3.4.2 Release Notes - ExternalDocument3 pagesTurbo HD DVR V3.4.2 Release Notes - Externalcrishtopher saenzNo ratings yet

- Maxima Manual: Version 5.41.0aDocument1,172 pagesMaxima Manual: Version 5.41.0aRikárdo CamposNo ratings yet

- Iit Hybrid ScheduleDocument3 pagesIit Hybrid ScheduleAdithyan CANo ratings yet

- Digital Educational Technology in Improving Professional Auditory CompetenceDocument3 pagesDigital Educational Technology in Improving Professional Auditory CompetenceOpen Access JournalNo ratings yet

- EURORIB 2024 Second CircularDocument5 pagesEURORIB 2024 Second CircularEsanu TiberiuNo ratings yet

- Nordys Daniel Jovita: Contact Number: 09505910416 Address: Aflek Tboli South CotabatoDocument2 pagesNordys Daniel Jovita: Contact Number: 09505910416 Address: Aflek Tboli South CotabatoNoreen JovitaNo ratings yet

- Department of Public Works and Highways: Regional Office Vii Cebu 6Th District Engineering OfficeDocument10 pagesDepartment of Public Works and Highways: Regional Office Vii Cebu 6Th District Engineering OfficeLolNo ratings yet

- Activity 3 EntrepDocument2 pagesActivity 3 EntrepCHLOE ANNE CORDIALNo ratings yet

- Teaching GrammarDocument22 pagesTeaching GrammarMUHAMMAD RAFFINo ratings yet

- Anfis (Adaptive Network Fuzzy Inference System) : G.AnuradhaDocument25 pagesAnfis (Adaptive Network Fuzzy Inference System) : G.Anuradhamodis777No ratings yet

- Method Statement - Relocate Street LightingDocument6 pagesMethod Statement - Relocate Street Lightingahmad.nazareeNo ratings yet

- VochysiaceaeDocument5 pagesVochysiaceaeElyasse B.No ratings yet

- Alpolic Cladding Panel PDFDocument5 pagesAlpolic Cladding Panel PDFdep_vinNo ratings yet

- The Modernist Moment at The University of LeedsDocument26 pagesThe Modernist Moment at The University of LeedstobyNo ratings yet

- Hu 2000777037Document1 pageHu 2000777037Patrik RottenbergerNo ratings yet

When Being - Deaf - Is - Centered - D - Deaf - Women

When Being - Deaf - Is - Centered - D - Deaf - Women

Uploaded by

Ramon SalOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

When Being - Deaf - Is - Centered - D - Deaf - Women

When Being - Deaf - Is - Centered - D - Deaf - Women

Uploaded by

Ramon SalCopyright:

Available Formats

When Being Deaf is Centered: d/Deaf Women

of Color’s Experiences With Racial/Ethnic and

d/Deaf Identities in College

Lissa Stapleton

Approximately 30% of d/Deaf students are Amy and her mother, a small-framed Asian

successfully completing college; the reasons for woman with a bright red jacket and large

such a low graduation rate is unknown (Destler tan purse, knock on my door, apologizing

& Buckly, 2011). Most research on d/Deaf college for disturbing me. I quickly stand up to

greet them and ask them to please come

students lack racial/ethnic diversity within the

in and have a seat. I have had several one-

study; thus, it is unclear how d/Deaf Students on-one interactions with Amy over her

of Color are faring in higher education or what two years at the institution. She struggled

experiences they are having. It is no longer with shifting identities between her life

appropriate or socially just to conduct research at home and school. At home, her family

that does not intentionally seek out the voices of treated her like a hearing person; she spoke

d/Deaf Students of Color. Using a fundamental her ethnic language, participated in all her

descriptive qualitative methodology, this paper ethnic cultural practices, and used hearing

aids. When she came to school, she only

sheds light on a population of students, d/Deaf

signed and did not interact with other Asian

Women of Color, who are often invisible within students, as most of the d/Deaf* students

the mainstream higher education literature and on campus were White. She did not feel

expands our understand of the types of experiences hearing, Asian, or d/Deaf enough to fit into

they are having related to their racial/ethnic and the residential or campus community. She

d/Deaf identity while attending college. struggled. Afraid, because of cultural taboos,

to tell her parents that she needed counseling

and unable to find a counselor to meet her

Reflexive Statement of communication needs (simultaneously

the Problem signing and speaking), she started to shut

It is about 2:00 p.m., and I am expecting down. The lack of congruency and peace she

Amy and her mother to drop by my office felt affected her schoolwork, her friendship

at any moment. Amy is an Asian American circles, and now her ability to stay at

deaf student who lives in one of my school because her behavior had become

residential halls. She had been struggling unpredictable and distant.

with identity issues, and her mother, who

I share this story as a way for readers to

was deeply concerned about her daughter’s

change in behavior, was coming to my understand the tensions that may come from

office to discuss resources. As I hurry to negotiating the intersection of d/Deaf and

finish a few random administrative tasks, race/ethnic identities. As a Black hearing

* The upper case D in the word Deaf refers to individuals who connect to Deaf cultural practices, the centrality of

American Sign Language (ASL), and the history of the community (Johnson & McIntosh, 2009; Mitchell, 2005;

Woodcock, Rohan & Campbell, 2007). The lower case d in the word deaf refers to the audiological condition

or medical severity of the person’s hearing loss (Trowler & Turner, 2002; Woodcock et al., 2007). In this study

d/Deaf is used because the differences are not always clearly identified in the literature or among the participants.

Lissa Stapleton is Assistant Professor of Deaf Studies at California State University Northridge.

568 Journal of College Student Development

When Being Deaf is Centered

woman, I worked at West Coast University the reasons for such a low graduation rate

for three years in student housing. I interacted is unknown (Destler & Buckly, 2011; Lang,

with a diverse population of d/Deaf students. 2002). Most research on d/Deaf college

Some students struggled with their racial/ students lacks racial/ethnic diversity within the

ethnic and d/Deaf identities, whereas others study or does not use race as a variable; thus,

gravitated toward one or the other, unaware it is unclear how d/Deaf students of color are

or choosing not to navigate both identities. I faring in higher education or what experiences

never forgot Amy or the influence she had on they are having.

my professional commitment to examine the There are several reasons why this research

college experiences of d/Deaf women of color is important. First, d/Deaf students matter.

(women of color referring to self-identified d/Deaf students’ attendance in our colleges

women who also identify as Black/African and universities is continuing to grow (Lang,

American, Latina/Hispanic/Chicana, Native 2002; Woodcock et al., 2007). As of 1993,

American/Indigenous, Asian American/Pacific there were more than 25,000 d/Deaf students

Islander, Middle Eastern, multiracial and (National Center for Education Statistics,

biracial) and the intersections of their racial/ 1994) attending colleges and universities, and

ethnic† and d/Deaf identities. in 2000, there were 468,000 d/Deaf students

enrolled (Schroedel, Watson, & Ashmore,

Introduction 2003). Higher education practitioners

and faculty must understand the college

Approximately 1 in 20 individuals identifies experiences of d/Deaf students in order to find

as d/Deaf in the United States (Mitchell, ways to support and better work with d/Deaf

2005). The d/Deaf community is dynamic students. Second, d/Deaf experiences and the

and members of this community are very d/Deaf community have been essentialized,

diverse in their range of hearing loss, cultural fixed, or stereotyped to mean White or White

connections, and the methods they use to people, and this must change. Parasnis (2012)

interact with the dominant hearing world. stated, “The experiences of white American

Historically, hearing people have remained Deaf ASL users has created a perception of

in power positions relative to d/Deaf people’s Deaf culture as a monolithic overarching

lives, thus labeling them as disabled. This trait of all deaf people and has suppressed

power has played out within family life and recognition of the demographic diversity of

during the fomative years of schooling (Trowler individuals within the Deaf community itself ”

& Turner, 2002). There are connections (p. 64). The voices and perspective of d/Deaf

between early education preparation, family people of color have been left largely invisible

involvement, and identity development that (Foster & Kinuthia, 2003). Finally, there is

influence the success of d/Deaf college students limited research on the college experiences of

(Lang, 2002). Approximately 30% of d/Deaf students of color with disabilities and even less

students are successfully completing college; about the intersection of d/Deaf experiences

†

In an initial questionnaire, participants were asked how they racially identified, and throughout the interviews,

some participants revealed and talked about their ethnic identity. For this study, race was defined as socially

constructed categories loosely based on skin color, facial features, hair, and family background (Walker,

2011). Ethnicity was defined as a group of people who share attributes acquired through genetic, cultural,

and historical inheritance, which are believed to be associated with their family’s descent (Walker, 2011).

The breakdown of the participants’ race and ethnicity can be seen in Table 1.

September 2015 ◆ vol 56 no 6 569

Stapleton

and race (Foster & Kinuthia, 2003) within Literature Review

higher education literature. It is no longer

appropriate or socially just to conduct research There has been research focusing on the college

that allows the reader to assume unconsciously classroom experiences of d/Deaf students

that all d/Deaf students are White or to (Boutin, 2008; Convertino, Marschark,

conduct research with only White d/Deaf Sapere, Sarchet, & Zupan, 2009; Foster, Long,

participants. In order to best serve their & Snell, 1999; Lang, 2002, Stinson, Scherer,

needs, improve our higher education practices, & Walter, 1987), but most studies have

and encourage their success, the voices, failed to acknowledge or address the multiple

experiences, and stories of d/Deaf students identities of d/Deaf students, specifically with

of color must more visibly and intentionally reference to race. Kersting (1997) focused

show up in the literature. on the social interactions of d/Deaf college

The overarching study explored the college students who attended mainstream institutions

experiences of d/Deaf women of color and and had no previous contact with the d/Deaf

what they perceived as salient to shaping community. Seven men and three women

their college experiences as it related to their participated in this study, and only their

families, their college classroom experiences, gender and age ranges were given. Students

their extracurricular lives, and the role of their in the study ultimately found ways to connect

identities, specifically racial/ethnic and d/Deaf to a community (d/Deaf, hearing, or both)

identity. It was conducted at a 4-year public and were satisfied but not without a struggle

institution on the West Coast of the United and moments of isolation, loneliness, and

States that serves approximately 200 d/Deaf rejection. The types of communities students

undergraduate and graduate students and were trying to connect with is unclear (i.e.,

will be referred to as West Coast University communities of color, White communities,

(WCU). This paper focuses on a portion of or multicultural communities) as was if that

the overarching study and uses a fundamental information would have made a difference

descriptive qualitative methodology. There in the findings. At this point, there is “no

were two primary purposes: first, to shed light empirical data available regarding the campus

on a population of students, d/Deaf women comfort level and educational satisfaction of

of color, who are often invisible within the racial/ethnic minority deaf students” (Parasnis,

mainstream higher education literature; and Samar, & Fischer, 2005, p. 48).

second, to understand the types of experiences College and career programs for Deaf

d/Deaf women of color were having as it Studies have identified several thousand 2- and

related to their racial/ethnic and d/Deaf 4-year institutions that serve d/Deaf student

identity while attending WCU. populations and offer support services (Lang,

This paper starts with a literature review, 2002). Many institutions are serving small

followed by the research design. The research numbers of d/Deaf students and often do not

design incorporates the methodology, a more have racial diversity within the d/Deaf student

in-depth description of the participants, the population. Parasnis et al. (2005) studied

guiding research questions, and data analysis. d/Deaf students’ attitudes toward racial/ethnic

The summary of findings concentrates on diversity, campus climate, and role models at

the participants’ voices and experiences, the Rochester Institute of Technology. One

flowing directly into suggestions for future hundred and fifty-seven d/Deaf students

research and practice. participated in the quantitative study, and the

570 Journal of College Student Development

When Being Deaf is Centered

ethnic breakdown was 34 African Americans, to rely on gesturing and writing notes at home.

29 Asian Americans, 18 Latinos, and 76 Because of communication barriers within

Whites (Parasnis et al., 2005). The notion of their family, understanding their culture and

“critical mass,” or having several individuals heritage was challenging. Some students did

from the same d/Deaf racial/ethnic group not have a connection to their culture, but

was addressed in the study. A critical mass of one Black student said, “[I learned] myself

students of color was seen as both affirming . . . watch[ed] Black entertainment. Read

and problematic, because all d/Deaf women magazines” (Foster & Kinuthia, 2003, p. 278).

of color do not experience and/or embrace This particular participant relied on the media

their race and ethnicity in the same way. One and pop culture to learn about her race,

student commented, “It is a very positive which can be problematic because of the gross

experience to belong to both a minority group stereotypes portrayed in the media regarding

and the deaf community since it enhances people of color (Aramburo, 1989). We have

my sense of identity.” Offering a contrasting to look deeper at the ways in which d/Deaf

perspective, another student observed that women of color understand their racial and

“subgroups make me feel uncomfortable. The ethnic culture in order to understand how and

lack of education about multiculture [sic] if it influences them as they holistically develop.

disappoints me deeply” (Parasnis et al., 2005, The findings from the study showed that

p. 56). There are multiple truths illustrating identity “is conceptualized as an interaction

how d/Deaf women of color experience and between the self and the surrounding social

embrace their race and ethnicity. Having a structures” (Foster & Kinuthia, 2003, p. 286)

critical mass of racially diverse d/Deaf students and that identity salience changes depending

allows d/Deaf women of color to have options on d/Deaf students’ of color environment.

to explore the intersections of these two d/Deaf students are diverse and come

particular identities whereby the student does to college with a variety of experiences.

not have to be d/Deaf or a person of color but They need to have support services, such as

has a community in which both identities are interpreters, captionists, note takers, and

acknowledged. The study concluded that race tutors, in order to be successful, but that is not

and ethnicity matter in regards to influencing all students need to thrive academically. The

the perception of campus climate and that academic experience is just one component

all minoritized d/Deaf student communities of the college experience. Foster (1989)

cannot be grouped together or assumed to said, “Social/personal factors play a critical

have the same experiences, needs, or support role in the success of deaf students in higher

(Parasnis et al., 2005). education. . . . Qualities [such as] persistence,

The importance of not essentializing all self-identity, self-efficacy, perseverance, ability

d/Deaf women of color’s experiences can be to accommodate oneself in an integrative

clearly seen in Foster and Kinuthia’s (2003) environment, and general maturity” (p. 269)

qualitative study, which explored how d/Deaf all need to be further developed for student

college students of color think about and success in higher education. Unfortunately,

describe their identities, specifically their most research on d/Deaf students and higher

d/Deaf and racialized identities. Most of the education has painted a broad and essentialized

college participants attended mainstream picture of who d/Deaf students are; thus, this

K–12 schools, had families who did not know study was the beginning step of exploring

American Sign Language and, as a result, had how d/Deaf women of color understood and

September 2015 ◆ vol 56 no 6 571

Stapleton

experienced their racial/ethnic and d/Deaf fulfill the purpose of this study. It raises

identities while attending WCU. awareness about d/Deaf women of color and

the experiences they had with their racial/

Research Design ethnic and d/Deaf identity. In addition,

this methodology is congruent with Deaf

Methodology

epistemology. Deaf epistemology is a Deaf-

This was a fundamental qualitative descriptive centered perspective that has been influenced

study, which is “a descriptive summary of a by critical and cultural theories (Paul & Moores,

phenomenon, organized in a way that best 2010). This epistemology is anti-essentialist

contains the data collected and that will be and makes no claims that there is one Deaf

most relevant to the audience for whom it way of knowing (Parasnis, 2012). Deaf

is written” (Sandelowski, 2000, p. 339). The epistemology believes knowledge is socially

purpose of this study was to understand the constructed and centers d/Deaf voices and

experiences d/Deaf women of color were ways of operating in the world, using personal

having as it related to their racial/ethnic and accounts to document knowledge (Holcomb,

d/Deaf identities while attending WCU and 2010; Paul & Moores, 2012). This study

to shed light on a population of students who consciously privileges d/Deaf over hearing

often are invisible within higher education ways of knowing, and this methodological

and mainstream higher education literature. approach “produces a complete and valued

Sandelowski (2000) stated that the goal of this end-product in itself. . . . [It] entails a kind

type of study is “to stay closer to the surface of interpretation that is low-interference”;

of the data” (p.336) and to accurately convey thus, allowing d/Deaf women of color to

the story or events as well as the meaning really speak for themselves. Deaf epistemology

given by the participants. Fundemental was used throughout the data collection and

qualitative descriptive studies use conceptual analysis process, as it justified why the women

and philosophical frameworks as a way should have communication options during

to organize and look at the data, but not their interviews, stressed the importance of

necessarily to analyze, as they are not highly the women speaking for themselves, and

interpretative (Sandelowski, 2000). This study centered and valued the perspectives of all the

has phenomenological overtones, meaning it women, including the minority or differing

touches on the experiences of the women, but the voices. The following sections address the four

purpose is not to produce “phenomenological components of the research design including

renderings of the target phenomenon” (p. 337) participants, data collection, analysis, and re-

nor were phenomenological methods and presentation techniques.

analysis used. Sandelowski (2000) stated

that this is a common practice because Participants

“qualitative descriptive studies are different

from phenomenological, grounded theory, Fundamental qualitative descriptive studies

ethnographic and narrative studies; [however] use purposeful sampling (Sandelowski, 2000).

they may, have hues, tones, and textures from Patton (2002) stated, “The logic and power of

these approaches” (p.337). purposeful sampling derive from the emphasis

This methodology is appropriate for this on in-depth understanding and selecting

study because descriptive summaries and information-rich cases whose [perspectives]

accurate accounts of the women’s experiences will illuminate the questions under study”

572 Journal of College Student Development

When Being Deaf is Centered

(p. 46). For this study, the participants had to was mostly their mothers who communicated

identify as d/Deaf and a person of color as well with them through American Sign Language,

as attend WCU at the time of interviewing. Signed Exact English, or signing and talking.

The hope was to recruit a group of diverse Each woman also had varying degrees of

ethnicities and gender; however, eight d/Deaf contact with d/Deaf people and culture before

female students initially volunteered, and attending college, ranging from no exposure

seven completed the full study. Students were to deeply connected. They all attended K–12

recruited through flyers hung on bulletin mainstreamed schools, but their mainstream

boards, e-mailing d/Deaf students and d/Deaf experiences were very different. Some were in

student organizations’ listservs, interacting small all-d/Deaf classes of one to two people

with students while visiting campus, and and signed, whereas others were in hearing

contacting WCU’s academic advisors and staff classes with an interpreter and some women

interpreters. Students received a $20 bookstore were in oral programs. Most of the participants

gift card for their participation. Participants’ applied to more than one college, but most

names were changed to protect their privacy. selected WCU because it was close to home

Each woman was asked to describe her life and had resources for d/Deaf individuals.

growing up and her educational experiences

before college. As seen in Table 1, the women Data Collection

were diverse in regards to race/ethnicity,

d/Deaf identity, majors, year in school, and The data collection process within a funda

preferred communication methods. All but mental qualitative descriptive study focuses

two lived off campus. Five of the women were on “discovering the who, what, and where of

from California, one lived in multiple states events or experiences, or their basic nature and

growing up, and one was from out of state. shape” (Sandelowski, 2000, p. 338), which

All the women had siblings but were the only in this study was guided by the following

d/Deaf people in their families. Most of the research questions:

participants were raised by two parents (male 1. What experiences are d/Deaf women of

and female), but two were raised by single color having at West Coast University

mothers. Most of the participants’ parents did as it relates to their racial/ethnic and

not sign, but in the families that did sign, it d/Deaf identity?

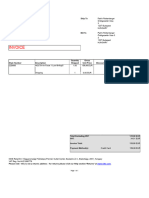

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

Year in Deaf/Hard of Communication

Name School Race/Ethnicity Hearing Major Category Preferencea

Deidra 3rd Chinese/Vietnamese Hard of hearing Deaf Studies SS

Jodie 3rd Korean Deaf Deaf Studies ASL

Mel 5th Black Deaf Education ASL

Joyce 3rd Asian American Deaf Deaf Studies ASL

Chloe 3rd Korean Deaf Liberal Arts ASL/SEE

Tiara 3rd Black Hard of hearing Education SS

Sunny 2nd Mexican Hard of hearing STEM ASL

a SS = signing and speaking; ASL = American Sign Language; SEE = Signed Exact English.

September 2015 ◆ vol 56 no 6 573

Stapleton

2. What aspects of racial/ethnic and used Google chat because each woman had a

d/Deaf identity are salient to d/Deaf Google account. The second interviews were

women of color? 60–90 minutes of typing back and forth,

Fundamental qualitative descriptive and the entire chat session was copied and

studies seek to collect as much data as possible used for analysis.

in order to capture accurate accounts of events

(Sandelowski, 2000). Thus, I collected data in Data Analysis

two ways through a preliminary questionnaire Using the first and second interviews, a

and two “moderately structured open-ended qualitative content analysis was conducted.

interviews” (Sandelowski, 2000, p. 338). The Fundamental qualitative descriptive studies

preliminary interview questionnaire included primarily use this analysis to analyze visual

demographics, educational background, and and verbal data to highlight the regularity of

communication preferences, which were ideas, feelings and thoughts within an event

used to establish a context for each of the in order to create an accurate summary of the

participants. Each participant filled out a participants’ voices and stories (Sandelowski,

consent form and face-to-face interviews were 2000). During the initial step in analysis,

conducted on campus in a private room. All the data was organized in a Word document

the questions were translated into American and the transcriptions were read several times

Sign Language syntax, and each of the women (Esterberg, 2002). Using open coding, color-

were given an English written copy of the coding was used for, all statements, stories,

interview questions to look at throughout ideas, thoughts and feelings connected to

the interviews. Based on the values of Deaf racial/ethnic and d/Deaf identity. Then,

epistemology and my experiences within experiences were identified that happened

the d/Deaf community, it was important to while the women attended WCU (working

build trust and rapport with the participants with faculty, encounters with peers, taking

by conducting my own signed interviews classes, student organization, etc.) or if it

without an interpreter. This allowed direct influenced their understanding of their racial/

communication with the women, greater ethnic and d/Deaf identity while at WSU

control over asking follow-up questions, and (encounters with family). Finally, focused

eliminated the filtering of the data through coding was used to narrow down the cate

an interpreter. gories, looking for similarities and differences

The first interviews were video-recorded among the women (Esterberg, 2002).

and lasted 1 hour. The second interviews Sandelowski (2000) stated, “There is

were set up before each participant left and nothing trivial or easy about getting the facts,

were conducted a month later, after the first and the meaning participants give to those

interviews had been translated and transcribed. facts, and then conveying them in a coherent

I read the transcriptions several times and and useful manner” (p.336). Thus, funda

developed additional and clarifying questions mental qualitative descriptive studies seek

for the second interviews. Because of the time interpretive and descriptive validity to ensure a

between the first and second interviews, and comprehensive summary of events and stories.

because of the fact that the participants and Interpretive validity is defined as “an accurate

I did not live in the same state, the second account of facts and meanings in which the

interviews were conducted from a distance participants would agree” (Sandelowski, 2000,

through instant messaging Google chat. I p. 338). Member checks were done during the

574 Journal of College Student Development

When Being Deaf is Centered

second Google chat interview, and divergent The word audism was coined by Deaf

participant perspectives were acknowledged scholar Tom Humphries (1977), who defined

throughout the findings in order to establish it as “the notion that one is superior based on

interpretive validity. Descriptive validity is one’s ability to hear or behave in a manner of

defined as “an accurate account of facts and one who hears” (p. 12). Many hearing people

meanings in which others observing would do not trust that d/Deaf people have the ability

agree” (Sandelowski, 2000, p. 338). This to control their own lives, and they believe they

was addressed by working with the academic can dominate and discriminate against d/Deaf

advisors in the d/Deaf resource center at individuals (Eckert & Rowley, 2013). Audism

WCU. The data were presented to them as is practiced overtly, covertly, and aversively.

a report, and a larger roundtable discussion Overt audism are practices that directly

was scheduled to talk through the findings as and openly dehumanize d/Deaf people, for

well as to compare the findings with what they example, policies and behaviors that isolate

experienced with students on a daily basis. and exclude d/Deaf people from society

without consequences (Eckert & Rowley,

Re-Presentation Techniques 2013). Covert audism are practices that are

The way in which a fundamental qualitative disguised and more difficult to identify, such

descriptive study is re-presented is a “straight as hiring practices and providing reasonable

descriptive summary of the informational accommodations. Aversive audism are practices

data organized in a way that best fits the that “concern a principle of equality accom

data” (Sandelowski, 2000, pp. 338–339). panied by contradictions and high levels of

This study used Deaf critical theory (Deaf anxiety when around Deaf people” (Eckert

Crit) as a tool to re-present the women’s & Rowley, 2013, p. 109) including avoiding

experiences because it is a Deaf-centered interaction and forcing d/Deaf people to

theory, created by and for d/Deaf people, assimilate into the hearing world.

to more accurately talk about their lived Similar to how CRT has adopted a

experiences. Developed by Gertz (2003), stance to challenge “the dominant group’s

Deaf Crit is informed by critical race theory linguistic and cultural snobbery, and to

(CRT), an interdisciplinary race-centered respect non-dominant discourses” (Gertz,

movement that is rooted in critical legal theory 2003, p. 419) as they relate to race, so too, has

and challenges notions of color-blindness and Deaf Crit focused on the liberation of d/Deaf

meritocracy (Delgado & Stefancic, 2012), individuals. The following four Deaf Crit

which surfaced as a result of Gertz’s (2003) tenets and explanations (Gertz, 2003), which

study with Deaf adults born and raised in are informed by the foundational principles of

Deaf families. She looked at how dysconscious CRT, were used as a way to think about and

audism, “a form of audism by means of an understand the women’s stories as well as a way

implicit acceptance of the dominant hearing to organize and re-present their experiences:

norms and privileges” (p. xii), impacted their • Centrality and intersectionality of

understanding of themselves as Deaf people d/Deaf people and audism,

as well as their awareness of unequal status

• Challenge of dominant hearing ideology,

in society. Deaf Crit was born as a way in

which to examine and talk about audistic • Centrality of d/Deaf experiential

subordination and marginalization of d/Deaf knowledge, and

people (Gertz, 2003).

September 2015 ◆ vol 56 no 6 575

Stapleton

• Commitment to social justice for identity and makes some connections and

d/Deaf people. observations back to the literature. The purpose

The data were not pulled apart, dissected, was to understand the experiences of d/Deaf

or analyzed using Deaf Crit as “concerns women of color at WCU related to their racial/

remained concerns and perceptions remained ethnic and d/Deaf identity, and ultimately,

perceptions” (Sandelowski, 2000, p. 338). shed light on a seemingly invisible student

However, Deaf Crit’s tenets helped organize population. The following tenets helped shape

and bring the women’s experiences together this summary: challenge of dominant hearing

and served as a lens in which to start to ideology, centrality and intersectionality of

understand how d/Deaf women of color d/Deaf people and audism, centrality of d/Deaf

at WCU experience their racial/ethnic and experiential knowledge, and commitment to

d/Deaf identity. social justice for d/Deaf people.

Limitations Challenge of Dominant Hearing

Ideology

There were limitations to this study. First,

the interviews were conducted in person and For many of the women, attending college

through Google chat. After completing the opened up a completely new world of accep

interviews, the women were asked which tance, communication, and friendship. Those

interviewing methods they preferred, and who did not learn to sign growing up or were

most said face-to-face. Google chat lacked the not exposed to d/Deaf people seemed thirsty

opportunity for nonverbal expression, which to connect to the d/Deaf community. The ways

aided them in understanding the questions, in which the women challenged the dominant

and they felt more comfortable responding in hearing ideology varied from subtle to direct. For

sign language. Although, measures were taken some of the women, challenging meant proudly

to maintain the integrity and accuracy of the identifying as d/Deaf, whereas others refused

interviews, a second limitation was posed by to be boxed in with all d/Deaf people. Some

the process of translating questions and data women joined and supported d/Deaf-specific

from language to language. student organizations, whereas others educated

themselves on d/Deaf history and culture.

Summary of Findings Tiara grew up active within the Black

community, used her voice and hearing aids,

The women understood their identities and and in many ways was able to mask her hard

cultures on a variety of levels. Some were of hearing identity. She focused mostly on

reflective about who they were and where they her newfound d/Deaf identity within the

came from, whereas others had a hard time interview. She talked passionately about her

articulating their identities and only knew experience of entering the d/Deaf community:

they felt a part of certain cultures but could Growing up I was very hearing minded

not express what the cultures meant. Coming and didn’t sign very well. When I came to

to WCU gave the women an opportunity to WCU, I have been very involved in the

be independent and discover who they were deaf world and not the hearing world. I

as d/Deaf people. This summary uses Deaf found my identity of who I am. I chose

critical theory as a tool to re-present the [the] deaf world; I can communicate

women’s stories, feelings, and experiences as in sign language rather than struggle to

understand what everyone is saying.

they related to their racial/ethnic and d/Deaf

576 Journal of College Student Development

When Being Deaf is Centered

Tiara consciously chose to find ways to learn She shared the following:

and connect with the d/Deaf community at The classes I took, as a Deaf Studies major,

WCU. In her desire to be a proud d/Deaf I just learned a lot, so I feel connected. In

person, she had to push back against her high school, I would just stumble through

family’s hearing ideology, as they saw her as conversation after conversation and just

a hearing person. Tiara refused to continue got by, and I did not know anything about

to be socialized or treated as if she was the deaf culture.

hearing. One way in which she pushed against Sunny’s way of challenging can be seen

this was through joining a d/Deaf student through her development of self-acceptance.

organization in spite of her family encouraging She spoke confidently:

her otherwise. She shared,

Here at WCU, I have learned to accept

I wanted to be more involved in the myself and my identity as a deaf woman.

deaf world, and I am glad I did. I have I am finally comfortable. When I got to

finally found myself, and I love it, being WCU and realized I sign, and everyone

able to communicate with all my [peers] around me is signing. I felt I finally fit in.

perfectly and can really be myself in that

[Deaf organization]. I wanted my family Although, she used speech most of her life at

to respect my deaf identity, so I decided home, Sunny spoke strongly about being a

to join the [Deaf organization]. Deaf person and used sign language and not

her voice at school. Challenging dominant

Opposite of Tiara, Mel grew up with more

hearing ideologies was complicated, as the

d/Deaf people around her. Her deafness played

women were the only d/Deaf people in their

a larger role in her life than did her Black

hearing families and were negotiating racial

culture. She shared her thoughts:

and ethnic identities. Sunny talked about how

I identify myself as Deaf, more so than her identities were situational:

with my Black ethnicity. I enjoy being

part of the Deaf community; I feel at At WCU, there are Mexican students on

home with Deaf people because we are the campus, but within the deaf community

same and we have a natural connection. here there are only a few that are Mexican,

It’s ingrained in me. I feel like I am still so I feel that it’s not as high of importance.

clueless on Black culture. However, back home I have many deaf

Mexican friends. I have a strong con

Mel acknowledged her positive connection nection to my Mexican heritage and

and sameness with d/Deaf people as a way to would give it the highest priority when I

normalize d/Deaf spaces and ways of being; am there. Really, I feel that my identities

however, this connection overshadowed her are more of a two and two [Deaf/ woman

racial identity, as she did not meet other Black or Mexican/woman] rather than all three

all the time.

d/Deaf people until college.

The d/Deaf culture and community at Challenging dominant hearing ideologies

WCU afforded the women the opportunity also meant questioning differences within the

and space to accept themselves as d/Deaf d/Deaf community. d/Deaf people are often

people. Deidra had a hard time explaining essentialized to have only one culture, and

what d/Deaf culture meant, but knew she had while attending WCU, Chloe realized she was

it inside of her. Her way of challenging hearing not like all d/Deaf people, particularly students

ideology was to educate herself about d/Deaf at Gallaudet University, the largest d/Deaf

people and culture as a Deaf Studies major. university in the world. She shared, “For me,

September 2015 ◆ vol 56 no 6 577

Stapleton

deafness is very different from [the] hearing sexism (Gertz, 2003). Jodie shared a couple

culture, but I am not into deaf pride like those of examples of when she was frustrated with

students at Gallaudet. I think of myself as an interpreter and faculty. She felt she was

normal, but deaf.” When asked to explain further, independent and could do a lot for herself, so

she stated, “If you go to Gallaudet, those students having a motherly interpreter was annoying:

are very different from here. Their sign language “I got a bad interpreter [and] she treated me

and their personality are very blunt. Deaf pride like I was a baby. She treated me like I did not

is usually in families full of deaf people.” know anything. Like how to raise my hand

The multiple ways in which the women were in class or meet other people for an activity.”

negotiating and challenging hearing ideology This is an example of aversive audism. The

varied, thus highlighting that not all d/Deaf interpreter was there to support and enhance

Women of Color have the same experiences. access, but in practice belittled her and did

For Tiara and Deidra, the d/Deaf community not treat her like a competent student. There

at WCU provided freedom, communication is a contradiction between what the interpreter

ease, and a deeper understanding of self, was paid to do and what actually happened.

which was affirming, whereas other women, Jodie continued by talking about an overt

like Mel, had the opportunity grow up audist experience with a faculty member: “I did

within the d/Deaf community, so WCU not have an interpreter during the professor’s

felt like a familiar home. Chloe and Sunny office hours, so I would have to communicate

shared the complex ways they were trying through pen and paper. And when I had to do

to make sense of their d/Deaf identity as it that, certain teachers had no patience for it.”

related to others. This study, itself, continues The unwillingness to use alternative methods

to challenge dominant hearing ideology by of communication outside of speaking is audist

raising consciousness about the importance of and privileges hearing people.

centering d/Deaf people of color’s discourse, Covert audism can be difficult to identify,

thus further acknowledging their “cultural as it is easy for hearing people to deny and

distinctiveness and validating Deaf people’s hide. Chloe talked more about working with

placement within the world” (Gertz, 2003, classmates. She gave an example of covert

p. 424) and in research. audism when she tried to work on a group

project with hearing students and felt their

Centrality and Intersectionality of lack of follow through was connected to their

d/Deaf People and Audism discomfort with d/Deaf people. She shared,

Deaf people’s lives intersect with issues of My deaf friend and I experienced this,

audism, and it is a central and constant form of hearing people look down at us. It’s how

oppression that attempts to belittle and shape they act around me. One time, I had a

d/Deaf people into hearing people. Although group project with two hearing students.

the women did not directly use the word We had to meet and discuss. They never

audism, they shared stories of overt, covert, showed up even though interpreters were

and aversive discrimination felt from their requested. My deaf classmates and I think

that they might not feel comfortable

families, classmates, and faculty. The women’s

working with us.

ability to share these experiences is vital, as it

speaks to their current lived experience and Chloe further elaborated that the hearing students

it may open the door to understanding other only wanted to e-mail and were not willing to

systems of oppression such as racism and meet in person after missing the meeting.

578 Journal of College Student Development

When Being Deaf is Centered

The subtleness of feeling left out or helped her resist her extended family’s overt

looked down upon also connected to Tiara’s audist behavior and thoughts by encouraging

experience with her peers inside her mixed her to go to college. Mel stated:

(hearing and d/Deaf ) student organization. I remember, after I graduated from high

The purpose of the group was to support school, my mom told my family that I

and uplift d/Deaf college women, but there was accepted at WCU. They were puzzled,

are more hearing members than d/Deaf, and asking if I could go to college even though

this shifted the dynamics of the group. Tiara I was deaf, and my mom told them I

wanted to increase d/Deaf membership, but could do it just like my other friends who

the exclusive overt audist behavior of hearing went to college. She strongly believed that

hearing and deaf were equal.

members made this very difficult. She said,

Audism was central to Tiara’s upbringing, as

During events, the [hearing members] will

talk in front of [d/Deaf members]. How she grew up learning only how to speak and

is that respectful to [d/Deaf members]? was not allowed to be involved with the d/Deaf

Because of [hearing members], we are community. Once she began college, she found

viewed negatively. [Hearing members] her own voice and identity and resisted her

don’t socialize much with deaf people, so family’s audist mindset:

that’s why [potential Deaf members] are

My mom didn’t really want me to be as

uncomfortable joining our group. [Current

involved [with d/Deaf-specific activities]

d/Deaf members] have tried and tried [to

because she thought that if I got involved

fix things]; it is the same cycle. Seems like

I would try to get away with things easier

[hearing members] don’t really understand

and use my deafness as an excuse, but

how [d/Deaf members] feel about it. It’s

that’s not how I work.

like nothing we can do about it.

Most of the women talked about ways in

The examples of hearing privilege displayed which they resisted or navigated through audist

by hearing members including talking around moments, but Chloe was the only woman who

d/Deaf members, and disregarding how this talked about internalized audism, or feelings

affected d/Deaf people in and out of the group of shame or embarrassment for being d/Deaf

were examples of overt audism. The hearing and needing accommodations. She shared,

members’ behavior was exclusionary, and there At [WCU] being the only deaf in a

was no fear of consequences (Eckert & Rowley, mainstream setting, sometimes it can be

2013). Tiara’s frustration with her peers not embarrassing . . . trying to communicate

respecting and understanding Deaf culture is with gestures and [writing] notes. You

often seen and felt within families. can’t communicate freely with hearing

Families, in general, want their children people having interpreters . . . it makes

to have productive and healthy lives, but things awkward like it’s supposed to be

two people, but the interpreter is my voice.

because most d/Deaf children are born into

hearing families, there can be a strong desire In some cases, because of her embarrassment,

to make their children hearing by simply Chloe would not request an interpreter

not acknowledging they are d/Deaf or by but would rely on hearing friends to help

not allowing them to be involved within the her navigate events and club meetings. The

d/Deaf community. In some cases, family negative ways internalized audism intersected

members were supportive of the women, and in Chloe’s life meant she struggled to be

in other cases, they were not. Mel’s mother involved in campus life.

September 2015 ◆ vol 56 no 6 579

Stapleton

The women shared a variety of positive and let me out alone even 5 minutes to walk

challenging aspects of navigating their college from my house. I have to do chores for

experiences in and outside of the classroom my parents since they are old. I want to

as d/Deaf women of color. The women break the rules from my parents because I

want to experience the world like others.

could more easily identify audist behavior or

Of course, I accept who I am, but the

moments of discrimination from their family, point of curfew and being dependent are

faculty, staff, and students that were directed hard for me.

at being d/Deaf as opposed to their race. They

had many resources but, often, overt, covert Unlike Joyce, who connected only cultural

and aversive practices of audism continued on expectations to her race/ethnicity, Sunny was

unquestioned and unresolved. able to articulately in greater depth what it

meant to be a part of her Mexican community,

Centrality of d/Deaf Experiential including values and behaviors. She shared,

Knowledge

[My family] taught me that the most

The experiential knowledge or lived experiences important thing in life is family. I will

of d/Deaf people are not necessarily the same as always respect my Mexican culture and

for hearing people (Gertz, 2003). The d/Deaf know that whatever happens in life, my

community is a cultural group (Gertz, 2003), family has my back. [They] also taught me

and there is no one lived d/Deaf experience; the importance of love. Oh, and we also

love our food!

thus, it was critical to ask the d/Deaf women

of color what their lives had been like and Some women’s lived experience suggested

how they navigated the world and center the that race did not matter, but they still felt a

study around their experiential knowledge with connection to their ethnicity. Deidra shared,

their racial/ethnic and d/Deaf identity. When “Really, race does not matter, but for me I

asked which identities were most salient, the would say hard of hearing is my main identity.

women offered varying perspectives on how That is most important to me because that is

they understood and connected with their race/ who I am . . . I am always going to be hard of

ethnicity as college students. The women did not hearing.” Even though she felt no connection

necessarily see or understand race and ethnicity to a racial identity, Deidra believed her mother

the same way. Some women talked about the had taught her about her ethnic identity

importance of their d/Deaf identity and could stating, “She taught me the way we pray, the

only connect with their racial/ethnic identity way we eat, the way we have to go through

through their appearance and ethnic cultural with funerals, the way we have to believe things

norms and not necessarily by membership in happen and the way we celebrate Chinese New

an ethnic community. After our first interview, Year.” Deidra’s deep connection to her hard

I was curious about what Joyce meant by of hearing identity seemed to be influenced

“I try to separate my Asian and American by her K–12 education and attending WCU.

identities.” Joyce offered an example of how she She shared, “The most important thing I have

understood her race/ethnicity as behaviors and learned from the community here at [WCU]

not connections with a community. is my similarity with [d/Deaf people]. I feel

I want to be independent like other equivalent to others in how we each got through

races. I noticed that most Asian parents life. My experience here has affected me.”

are strict about the kids’ rules. [You have It is important to honor the roles Deidra’s

to] study hard [and] my parents won’t educational environments have played in

580 Journal of College Student Development

When Being Deaf is Centered

shaping who she is. She grew up going to oral movies; I’ve tried to understand the Black

schools, or a school in which she was taught perspective because I want to relate to that

to speak and not sign and where she was not since I am Black. I don’t speak or act like

allowed to interact with d/Deaf children or Black people do with the snapping—I’m

a very humble person. When people tell

use sign language in school even though she

me I don’t act like a Black person, I feel

knew some signs. Her hard of hearing identity discouraged when really it’s just because

may be more salient now due to her inability, I don’t know Black culture.

but strong desire, to interact with the d/Deaf

community when she was younger. Deidre Mel’s experiential knowledge of Black

no longer had to struggle to communicate people was based on stereotypical pop culture

with her peers, and she was obtaining a views of Blacks that she had seen in the media.

new awareness of what it meant for her to She stated, “[Black people] tend to have an

be d/Deaf through her major, Deaf Studies. attitude and wear big hoop earrings and have

When d/Deaf students have the opportunity to big breasts and butts.” This was also displayed

learn more about Deaf history, language, and in Foster and Kinuthia’s (2003) research, as

culture through Deaf Studies courses or d/Deaf students used movies and entertainment as a

community interaction, they begin to better source of education, which did not give a wide,

understand themselves as d/Deaf people and positive, or diverse image of people of color

see themselves in more positive ways (Gertz, (Aramburo, 1989).

2003). This is what happened to Deidra Another potential factor that may have

when she became active within her academic contributed to the women’s experiential

program and spoke often about how much disconnection between their racial/ethnic

she was learning in her Deaf Studies classes. identities was the small number of d/Deaf

d/Deaf students’ identities change based on the people of color with whom the women

interaction between self and surrounding social interacted. Parasnis et al. (2005) addressed

structures (Foster & Kinuthia, 2003). The the importance of a critical mass of d/Deaf

college experience at WCU was fertile ground people of color in helping students find

for Deidra to explore her d/Deaf identity more congruency with both their d/Deaf and racial

readily than her race/ethnic identity. identity. This is not the case at WCU, and the

Some of the women had a hard time women specifically talked about how there

articulating how they identified and a harder were not many d/Deaf people from their

time describing what their race/ethnic culture ethnic group or how they had met only one

meant. These women did not express a tension or two other people. Mel’s first time meeting

between their race and d/Deaf identities another Black d/Deaf person was in college.

because they seemed to have no context for She thought she was the only one for most of

what their racial identity meant. Based on her life. These experiences of disconnectedness

comments like Mel’s, it is evident that they cut across racial groups. Chloe said, “I grew

had not had an opportunity to understand or up in America, so I have no idea about my

fully connect to their race/ethnic community culture and its traditions—I don’t know how

or culture. Mel spoke about her experiences as to cook Korean food.”

a Black Deaf person: Gertz (2003) stated, “The experiential

I have tried to learn, but I still don’t feel knowledge of Deaf people is legitimate,

a connection with that [Black] identity. appropriate and critical to analyzing and

I’ve watched many Black shows and understanding” (p. 424) the lives of Deaf

September 2015 ◆ vol 56 no 6 581

Stapleton

people. In this study, family, media, and their experiences of d/Deaf people of color, such

current lived experiences played a role in the as in this study, must be conducted. This

connection or lack of connection the women study provides an opportunity to continue

felt with their racial/ethnic identity. Most the dialogue on what is occurring in the

could not articulate what it meant to be a lives of d/Deaf college students and, more

part of their ethnic community or culture, but specifically, d/Deaf students of color. It is an

this was not the case for all the women. Their act of resistance to interrupt White and hearing

desire to belong and communicate with others ways of being. This study aids in preserving the

allowed their Deaf identity to be more salient stories of a marginalized community, creating

than their ethnic identity, particularly while visibility, and declaring that d/Deaf students

at school. They met other d/Deaf people with of color matter. In addition, collecting data in

whom they could communicate directly and d/Deaf-friendly ways, such as using multiple

had similar life experiences. forms of communication, and building

rapport with the community are all important

Centering d/Deaf People of Color components to social justice work with and

Voices and Social Justice Commitment within the d/Deaf community.

The experiential knowledge and stories of

d/Deaf women of color were acknowledged Conclusion, Future

and centered in this study. Their voices were Research, and Practice

legitimate, and the study relied heavily on

their narratives and family history. Intentional Most of the d/Deaf women of color in this study

efforts were made to not essentialize or make centered, acknowledged, and understood their

claims that all d/Deaf students of color d/Deaf identities more than their racial/ethnic

understand and negotiate their racial/ethnic identities. Family interactions, communication

and d/Deaf identity the same way. Research, breakdowns, discrimination, isolation, the

similar to the women’s stories, suggested the d/Deaf community at WCU, personal explor

salience of identities can shift depending on ation, and personal desires to belong all

different factors including family influence, influenced how the women saw themselves.

peers, and access to community, to name Coming to WCU served as a gateway to a

just a few (Foster & Kinuthia, 2003). Thus, larger and more established d/Deaf world. They

it would never be possible to capture one had the opportunity to explore language, form

universal d/Deaf student of color experience. friendships with other d/Deaf students, and

This is why it is necessary to center the voices navigate their world more easily because of the

of d/Deaf people of colors and not hear people support, community, and environment created

speaking for d/Deaf people, as their lived at WCU, both socially and academically. They

experiences are fluid. also faced discrimination and challenging

This study also falls in line with a com moments as they navigated their majority-

mitment to social justice; as Gertz (2003) hearing world such as encounters with faculty,

stated, “One of the important goals in the peers, and their families.

Deaf community for social justice is to ensure This fundamental descriptive qualitative

that the Deaf community is a cultural group study provides a starting point at which

in which Deaf people can view themselves to more deeply explore the lives of d/Deaf

as normal human beings” (p. 424). In order students of color. The college experience is

for this to happen, research that centers the supposed to be a rich environment in which

582 Journal of College Student Development

When Being Deaf is Centered

students grow and develop more complex ways and hearing privilege, as our hearing ability is

of seeing the world and themselves (Pascarella temporal; thus, issues of audism impact us all.

& Terenzini, 1998). Social and personal Start with educating staff and faculty through

factors, such as self-identity and self-efficacy, retreats, diversity teach-ins, and campus

are critical for d/Deaf students’ success in workshops. Then, move to incorporating

higher education (Foster, 1989). Thus, it is audism into orientation leader, Greek life, and

important that higher education professionals resident advisor training, to name just a few.

and faculty are mindful of the complexities Fourth, academic advisors and faculty

d/Deaf women of color are trying to navigate, mentors must support and promote the

as these professionals may serve as critical existence of Deaf and Ethnic Studies courses

resources. The educational community needs and programming on campus. This is often the

to ask more questions and continue researching first time students are exposed to social identity

d/Deaf communities of color. Future research material, and their self-identity development

focusing on a larger and more gender diverse can benefit from these opportunities (Gertz,

pool of d/Deaf students of color would offer 2003). Finally, institutions may not have

additional perspective and depth. In addition, a larger number of d/Deaf students or any

comparing the experiences of d/Deaf students d/Deaf students of color, but creating inclusive

of color from schools in different geographical campus cultures, policies, and opportunities

locations may offer additional insight. Finally, are changes that happen over time and cannot

concentrating on d/Deaf students of color begin after students arrive. Make current

who attended different types of institutions, student spaces more inclusive and considerate

including community, private, public, and of intersecting identities. For example, provide

for-profit institutions, would allow comparison resources for d/Deaf women in the women’s

of experience and thought. The dearth of center, purchase books on minoritized d/Deaf

research in this area makes this subject matter people for the multicultural center library,

rich for investigation, allowing for continued highlight famous d/Deaf people within ethnic

exploration of the intersections of d/Deaf month celebrations, and invite a d/Deaf queer

experiences and race, as well as other identities. speaker for National Coming Out Week. The

Concerning practice, there are many first purpose is to make our current spaces more

steps practitioners can explore. First, start by d/Deaf friendly, which ultimately benefits and

asking questions in order to become aware. exposes hearing and d/Deaf students to new

Do you have d/Deaf students attending diverse opportunities. Being mindful of all

your institution? If not, why? If so, how students’ multiple intersecting identities when

many students? What are the demographics hiring faculty and staff, planning orientations,

of these students? What accommodations designing programs, and constructing new

do they have access? Second, acquire an buildings is critical because the decisions and

understanding of Deaf identity development equitable seeds we plant today affect students

theory (Glickman, 1996) while maintaining 10 to 20 years in the future.

awareness that intersecting identities, such as

race, can influence how d/Deaf students sees

themselves and experience their racial and Correspondence regarding this manuscript should be sent

d/Deaf community. Third, it is important to to Lissa Stapleton, PhD., Department of Deaf Studies,

expand diversity and equity trainings beyond ED 1107, 18111 Nordhoff Street, Northridge, CA

race, class, and gender and incorporate audism 91330–8265, lissa.stapleton@csun.edu

September 2015 ◆ vol 56 no 6 583

Stapleton

References

Aramburo, A. (1989). Sociolingustic aspect of the Black Deaf Lang, H. (2002). Higher education for deaf students: Research

community. In C. Lucas (Ed.), The sociolingustics of the deaf priorities in the New Millennium. Journal of Deaf Studies and

community (pp. 103‑119). New York, NY: Academic Press. Deaf Education, 7, 267‑280.

Boutin, D. (2008). Persistence in postsecondary environments of Mitchell, R. E. (2005). How many deaf people are there in the

students with hearing impairments. Journal of Rehabilitation, United States? Estimates from the survey of income and program

74(1), 25‑31. participation. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 11, 1‑8.

Convertino, C. M., Marschark, M., Sapere, P., Sarchet, T., & National Center for Education Statistics. (1994). Deaf and hard

Zupan, M. (2009). Predicting academic success among Deaf of hearing students in postsecondary education. Washington,

college students. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, DC: U. S. Department of Education.

14, 324‑343. Parasnis, I. (2012). Diversity and deaf identity: Implications for

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2012). Critical race theory (2nd personal epistemologies in deaf education. In P. Paul & D. F.

ed.). New York, NY: New York University Press. Moores (Eds.), Deaf epsistemologies: Mulitple perspectives on

Destler, W., & Buckly, G. J. (2011). NTID 2011 annual report. the acquisition of knowledge (pp. 63‑80). Washington, DC:

Retrieved from http://www.ntid.rit.edu/media/annual-report Gallaudet University Press.

Eckert, R., & Rowley, A. J. (2013). Audism: A theory and Parasnis, I., Samar, V. J., & Fischer, S. D. (2005). Deaf college

practice of audiocentric privilege. Humanity and Society, students’ attitudes toward racial/ethnic diversity, campus

37(2), 101‑130. doi:10.1177/0160597613481731 climate and role models. American Annals of the Deaf, 150,

Esterberg, K. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research. 47‑58. doi 10.1353/aad.2005.0022

Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. Pascarella, E., & Terenzini, P. T. (1998). Studying college

Foster, S. (1989). Social alienation and peer identification: students in the 21st century: Meeting new challenges. Review

A study of the social construction of deafness. Human of Higher Education, 21, 151‑165.