Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Implementation of The Competence-Oriented Learning and Teaching in Finland

Implementation of The Competence-Oriented Learning and Teaching in Finland

Uploaded by

K DOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Implementation of The Competence-Oriented Learning and Teaching in Finland

Implementation of The Competence-Oriented Learning and Teaching in Finland

Uploaded by

K DCopyright:

Available Formats

Implementation of the Competence-oriented Learning and Teaching in Finland

Finland has been the showcase of a high quality education system for a long time. Finnish students score

high on the PISA test and show low high-school dropout rates. All Finnish teachers have master’s

degrees and enjoy autonomy in their work. The Finnish education system is built on competent

teachers, high expectations for students and flexible implementation of the curriculum (Kivinen, 2015).

To strengthen these values and adapt learning and teaching to the changes in society (digitalization and

globalization), Finland recognized a need for a curriculum reform.

In 2009 the Finnish National Board of Education (FNBE) ordered the design of The Future of Learning

2030 Barometer to support the curriculum reform. The Barometer was designed to identify the

futuribles, possible futures, and the challenges that could affect education. The Barometer is now used

as a tool for monitoring the implementation of the new NCC (Airaksinen, Halinen and Linturi, 2016).

Definitions and Terminology

EDUFI (Finnish National Agency for Education) - the national development agency responsible for early

childhood education and care, pre-primary, basic, general and vocational upper secondary education as

well as for adult education and training.

FNBE (Finnish National Board of Education) – national agency subordinate to the Ministry of Education

and Culture.

NCC (National Core Curriculum) – framework around which the local curricula are designed.

Local curriculum – designed in each municipality, complements the NCC with local emphasis.

The Future of Learning 2030 Barometer – a qualitative forecasting tool to determine possible futures

and challenges in education.

Implementation Process and Stages

The reform was carried out from 2012 to 2016/2017 and followed the timetable pictured below.

Image: Timeline of the General education reform in Finland

The reform was a team effort and the process was transparent and inclusive. There were working groups

in each municipality and over 300 people participated in the working groups. The FNBE organized three

open consultations in 2012, 2013, and 2014. During the consultations teachers and other education

providers could give feedback about the process. Students participated in an extensive survey about

their learning, school culture and environment, etc. The process involved many stakeholders and even

the Finnish police offered to work on the safety and security chapters of the curriculum. EDUFI aimed to

make everyone involved an expert in the process (Lähdemäki, 2016).

The core values of the new NCC were the following:

students in the central position (the NCC put emphasis on meaningful learning and the joy of

learning, and the uniqueness of each student)

student agency (although Finland had a student-centered approach before the reform, students

and teachers re-evaluated what learning is, what it looks like and how it can be facilitated)

school culture (school as a learning community with strong values)

integrative approach and competencies (students seeing the connections between their school

subjects and real life, recognizing one’s personal strengths and potential development)

multidisciplinary learning modules (phenomenon-based learning; all schools must offer enquiry-

based work at least once a year, specifics are decided on a local level)

assessment (focusing on feedback, self-reflection and peer feedback) (Halinen, 2018).

Implementation of the NCC on a local level required collaboration from teachers and other staff. The

only obligation is the single multidisciplinary module once a year. Schools and municipalities can plan

the rest of the modules according to their needs (Finnish National Board of Education, 2016).

Assessment

The curriculum provides criteria for good performance for assessment in grades 6 and 9. Overall, Finland

does not have high stakes tests for students and the purpose of assessment is to provide data for

teachers and guide student learning.

The biggest importance is placed on feedback and encouragement, since students are expected to take

responsibility for their learning. Students are taught to evaluate their performance against objectives.

Pupils are not compared to one another but encouraged to identify their strengths and work on them.

Self-reflection, self-assessment and peer-assessment is encouraged (Finnish National Board of

Education, 2016).

Results of Application

Firstly, because of the inclusive curriculum development process, the new NCC was generally well-

received and positively covered in the media. Generally, the NCC is a success and definitely

strengthened the Finnish education system. Phenomenon-based learning has gained popularity due to

the NCC and was also praised by Skola2030 experts in a trip to Finnish schools (Skola2030, 2020).

The Barometer identified some challenges that were later confirmed in the implementation process,

such as:

student and teacher roles – the change from a hierarchical structure in the classroom where the

teacher delivers content and a student receives requires change of mindsets from both students

and teachers;

cooperation – developing the local curricula meant collaboration between teachers and school

staff, as well as students and their parents. Schools identified weaknesses in teacher teamwork

and collaboration, now trying to find new ways to work together (Airaksinen, Halinen and

Linturi, 2016 and FNBE 2016).

Other issues that complicate the implementation of the NCC are lack of in-service training that could

help teachers make sense of the NCC and lack of leadership among teachers. Implementing new ideas

requires courage and, in some cases, standing up to the way things have been done for many years

(Lähdemäki, 2016). Overall, it seems that school culture plays a significant role in the success of the

reform.

References

1. Airaksinen, T., Halinen, I., Linturi, H. (2016) Futuribles of learning 2030 - Delphi supports the reform of

the core curricula in Finland. Source:

https://eujournalfuturesresearch.springeropen.com/articles/10.1007/s40309-016-0096-y

2. Finnish National Board of Education (n.d.) Curriculum Reform in Finland. Source:

http://www.euroedizioni.it/attachments/article/697798/Curriculum%20Reform%20in%20Finland.pdf

3. Finnish National Board of Education (2016) New National Core Curriculum for Basic Education: Focus

on School Culture and Integrative Approach. Source:

https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/new-national-core-curriculum-for-basic-

education.pdf

4. Halinen, I. (2018) The New Educational Curriculum in Finland in Improving the Quality of Childhood in

Europe. Alliance for Childhood European Network Foundation, Brussels, Belgium.

5. Kivinen, K. (2015) Why change the education system that has been ranked as top quality? Finnish

curriculum reform 2016. Source: https://kivinen.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/finnish-curriculum-

reform-2016-kk.pdf

6. Lähdemäki, J. (2016) Case Study: The Finnish National Curriculum 2016—A Co-created National

Education Policy in Sustainability, Human Well-Being, and the Future of Education. Palgrave Macmillan.

7. Skola2030 (2020) Skola2030 eksperti viesojas Somijas skolās. Source:

https://www.skola2030.lv/lv/jaunumi/blogs/skola2030-eksperti-viesojas-somijas-skolas

You might also like

- Selection Process ExperienceDocument1 pageSelection Process ExperienceRg Perola67% (3)

- Essay AASDocument4 pagesEssay AASGina KhayatunnufusNo ratings yet

- Finnish Teachers and Librarians in Curriculum ReformDocument11 pagesFinnish Teachers and Librarians in Curriculum Reformfrem1983No ratings yet

- Education Model Finland - Marianne PDFDocument12 pagesEducation Model Finland - Marianne PDFyellowcat91No ratings yet

- EducationmodelFinland MarianneDocument12 pagesEducationmodelFinland Mariannejose300No ratings yet

- Building Blocks For High Quality Science Education: Reflections Based On Finnish ExperiencesDocument16 pagesBuilding Blocks For High Quality Science Education: Reflections Based On Finnish ExperiencesEko WijayantoNo ratings yet

- Teacher Professional Development in Finland: Towards A More Holistic ApproachDocument17 pagesTeacher Professional Development in Finland: Towards A More Holistic ApproachSiti NoorhafizzaNo ratings yet

- The Theory of Pedagogical Leadership Enhancing HigDocument19 pagesThe Theory of Pedagogical Leadership Enhancing HigAnviti SinghNo ratings yet

- TL and PD Covid19Document22 pagesTL and PD Covid19Junn Ree MontillaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of School Administration and Educational Supervision On Teachers Teaching Performance: Training Programs As A Mediator VariableDocument17 pagesThe Effect of School Administration and Educational Supervision On Teachers Teaching Performance: Training Programs As A Mediator VariableIhla Katrina Tubigan100% (1)

- Phenomenon-Based Teaching and Learning Through The Pedagogical Lenses of Phenomenology: The Recent Curriculum Reform in FinlandDocument17 pagesPhenomenon-Based Teaching and Learning Through The Pedagogical Lenses of Phenomenology: The Recent Curriculum Reform in FinlandAgustín AlemNo ratings yet

- What Makes School Systems Perform?: Seeing School Systems Through The Prism of PisaDocument74 pagesWhat Makes School Systems Perform?: Seeing School Systems Through The Prism of PisaDjango BoyeeNo ratings yet

- Chapter Ii SampleDocument38 pagesChapter Ii Sampleprincesstiq04No ratings yet

- +promoted Widely But Not Valued Teachers Perceptions of Team Teaching As A Form of Professional Development in Post-Primary Schools in IrelandDocument18 pages+promoted Widely But Not Valued Teachers Perceptions of Team Teaching As A Form of Professional Development in Post-Primary Schools in Irelandmsduru1987No ratings yet

- Teacher Professional Development in FinlandDocument16 pagesTeacher Professional Development in FinlandKaren ManrillaNo ratings yet

- 162-Article Text-1685-1-10-20220131Document27 pages162-Article Text-1685-1-10-20220131Naiv Dela Cerna BarrantesNo ratings yet

- Torres Gordillo (2020)Document17 pagesTorres Gordillo (2020)MartaPBNo ratings yet

- Rieckmann Educationforsustainabledevelopmentinteachereducationaninternationalperspective Post-Print PDFDocument15 pagesRieckmann Educationforsustainabledevelopmentinteachereducationaninternationalperspective Post-Print PDFMaheen MohiuddinNo ratings yet

- 420 GHJDocument6 pages420 GHJSunil KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Conference Paper No. 35: Curriculum Redevelopment: Stakeholders Sharing The Decision MakingDocument18 pagesConference Paper No. 35: Curriculum Redevelopment: Stakeholders Sharing The Decision MakingWallacyyyNo ratings yet

- Finland SahlbergDocument39 pagesFinland SahlbergEddy TriyonoNo ratings yet

- Laptop Initiatives Summary of Research Across Seven StatesDocument20 pagesLaptop Initiatives Summary of Research Across Seven Stateschintan darjiNo ratings yet

- 6443 21242 2 LeDocument15 pages6443 21242 2 LeHendri ZainuddinNo ratings yet

- Jannietal2019tuhatEducationalResearch PDFDocument19 pagesJannietal2019tuhatEducationalResearch PDFShine Carie SagalaNo ratings yet

- Output For Program EvaluationDocument31 pagesOutput For Program EvaluationLordino AntonioNo ratings yet

- Midterm Research M 1Document3 pagesMidterm Research M 1TasyaNo ratings yet

- December Newsl 07 Feature Article Excellence in EducationDocument6 pagesDecember Newsl 07 Feature Article Excellence in EducationBimal SohailNo ratings yet

- Policy Dialogue Forum and Governance Meetings - Concept Note - EN 16 NovemberDocument15 pagesPolicy Dialogue Forum and Governance Meetings - Concept Note - EN 16 Novemberyujialing2011No ratings yet

- Ej 1114410Document10 pagesEj 1114410ogakun69No ratings yet

- SingaporeDocument11 pagesSingaporepoisonboxNo ratings yet

- LinakeandHlatini-MphomaneSPAIN2020Document8 pagesLinakeandHlatini-MphomaneSPAIN2020Catherine TalanaNo ratings yet

- Initial Teacher Education For Inclusion: A Review of The LiteratureDocument23 pagesInitial Teacher Education For Inclusion: A Review of The LiteratureJara MuñozNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal - LAC - Romano.PogoyDocument18 pagesResearch Proposal - LAC - Romano.PogoyJhay-are PogoyNo ratings yet

- ResearchinSpecEducNeeds 2014 Lakkala HowtomaketheneighbourhoodschoolaschoolforallDocument12 pagesResearchinSpecEducNeeds 2014 Lakkala Howtomaketheneighbourhoodschoolaschoolforallkrishnajoshijaipur2024No ratings yet

- Thesis Revision-ChaptersDocument79 pagesThesis Revision-ChaptersRonnie BalcitaNo ratings yet

- Factors Influence The Development of Curriculum.Document7 pagesFactors Influence The Development of Curriculum.hecamidaNo ratings yet

- Improving Literacy and Numeracy in Poor Schools: The Main Challenge in Developing CountriesDocument5 pagesImproving Literacy and Numeracy in Poor Schools: The Main Challenge in Developing Countriesmiemie90No ratings yet

- Unit 5 Pres NtationDocument53 pagesUnit 5 Pres Ntationambreenawan1702No ratings yet

- 3104 22755 1 PBDocument9 pages3104 22755 1 PBMardhatillah SamaduoNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Perception of Higher Diploma Program As Opportunity For Promoting Professional Development in Arba Minch University (Ethiopia) : A Qualitative InquiryDocument24 pagesTeachers' Perception of Higher Diploma Program As Opportunity For Promoting Professional Development in Arba Minch University (Ethiopia) : A Qualitative InquiryDessalegn EjiguNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive-Examination Maepm-413 2022Document7 pagesComprehensive-Examination Maepm-413 2022Rovie SaladoNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Analysis of School Inclusion Through Index For InclusionDocument13 pagesDescriptive Analysis of School Inclusion Through Index For InclusionAri MateaNo ratings yet

- 5 Movements in Education and Educational ReformsDocument5 pages5 Movements in Education and Educational ReformsJochris IriolaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT)Document11 pagesInternational Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT)Norlie ReangcosNo ratings yet

- Ej 1118589Document9 pagesEj 1118589ROHIT KALIYARNo ratings yet

- Oecd - Sistemas Escolares Sensibles - 2018Document304 pagesOecd - Sistemas Escolares Sensibles - 2018Francisco Alejandro Riveros RamírezNo ratings yet

- Competence Based CurriculumDocument8 pagesCompetence Based CurriculumBarakaNo ratings yet

- EJ1272191Document31 pagesEJ1272191WallaceAceyClarkNo ratings yet

- 6421 14773 1 SMDocument14 pages6421 14773 1 SMAl Patrick ChavitNo ratings yet

- MIDTERM EXAM - Iffianti Azka Atsani 1803287Document3 pagesMIDTERM EXAM - Iffianti Azka Atsani 1803287Iffianti Azka AtsaniNo ratings yet

- Development and Validation of Instructional Materials in Reading.Document38 pagesDevelopment and Validation of Instructional Materials in Reading.Ely Boy AntofinaNo ratings yet

- RRL Additional LiwoDocument5 pagesRRL Additional LiwoDick Jefferson Ocampo PatingNo ratings yet

- Teachers Understanding of Contemporary ApproachesDocument11 pagesTeachers Understanding of Contemporary ApproachesSheridan Yvonne AlabaNo ratings yet

- Teacher Education For Inclusive Education A Framework For Developing Collaboration For The Inclusion of Students With Support PlansDocument27 pagesTeacher Education For Inclusive Education A Framework For Developing Collaboration For The Inclusion of Students With Support PlansJohan Fernando Aza RojasNo ratings yet

- Developing Physics Learning Tools of Blended Learning Using Schoology With Problem-Based Learning ModelDocument14 pagesDeveloping Physics Learning Tools of Blended Learning Using Schoology With Problem-Based Learning ModelRara Aisyah RamadhanyNo ratings yet

- Bridging Insula Europae Swedish National Research: Reports of Results and ConclusionsDocument12 pagesBridging Insula Europae Swedish National Research: Reports of Results and ConclusionsCentro Studi Villa MontescaNo ratings yet

- 4591 Kamila & Agus RMDocument8 pages4591 Kamila & Agus RMRadhia HasibuanNo ratings yet

- Assessment 1Document6 pagesAssessment 1api-506928647No ratings yet

- Bulgarian National Research: Conducting Survey Research - Report of Results and ConclusionsDocument9 pagesBulgarian National Research: Conducting Survey Research - Report of Results and ConclusionsCentro Studi Villa MontescaNo ratings yet

- Final-Report TRP CUP 2016 BalciDocument20 pagesFinal-Report TRP CUP 2016 BalcithuyduongNo ratings yet

- High-Stakes Schooling: What We Can Learn from Japan's Experiences with Testing, Accountability, and Education ReformFrom EverandHigh-Stakes Schooling: What We Can Learn from Japan's Experiences with Testing, Accountability, and Education ReformNo ratings yet

- English As A Global LanguageDocument73 pagesEnglish As A Global LanguagePatrikNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Listening and CompositionDocument7 pagesRhetorical Listening and CompositionPatrick W. BerryNo ratings yet

- Final Stephnaie S-GroupDocument75 pagesFinal Stephnaie S-GroupMichael Stephen GraciasNo ratings yet

- Golden Bee Global School: One of The Best International Schools in BannerghattaDocument5 pagesGolden Bee Global School: One of The Best International Schools in BannerghattagoldenbeeNo ratings yet

- Unit - 2Document14 pagesUnit - 2vivek singhNo ratings yet

- Empirical Review of Stroop EffectsDocument14 pagesEmpirical Review of Stroop EffectsFrank WanjalaNo ratings yet

- Business Analytics Assignment: Submitted By, Nithin Balakrishnan S4 Mba Roll No 6Document3 pagesBusiness Analytics Assignment: Submitted By, Nithin Balakrishnan S4 Mba Roll No 6Anonymous VP5OJCNo ratings yet

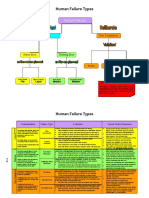

- Types of Mistake PDFDocument2 pagesTypes of Mistake PDFAdita Yumanda100% (1)

- Theatrical InterpretingDocument1 pageTheatrical Interpretingapi-484414718No ratings yet

- Teacher'S Guide: Exploratory Course On Handicraft ProductionDocument14 pagesTeacher'S Guide: Exploratory Course On Handicraft ProductionAngel Raphael90% (10)

- AcademicCareers Research Statements 07 08Document3 pagesAcademicCareers Research Statements 07 08ariatinining120876No ratings yet

- Primary 1-7 HBL - T3W1 Tue 2 JunDocument2 pagesPrimary 1-7 HBL - T3W1 Tue 2 JunOnaFajardoNo ratings yet

- 6 Time Management FinalDocument28 pages6 Time Management Finalxr4dmNo ratings yet

- Hate Speech Detection in Twitter Using Natural Language ProcessingDocument7 pagesHate Speech Detection in Twitter Using Natural Language ProcessingAtılay YeşiladaNo ratings yet

- Conflicting Perspectives of Power, Identity, Access and Language Choice in Multilingual Teachers' VoicesDocument15 pagesConflicting Perspectives of Power, Identity, Access and Language Choice in Multilingual Teachers' VoicesRuzzen Dale CaguranganNo ratings yet

- Rbi For Pces MTCDocument3 pagesRbi For Pces MTCMary-Ann SanchezNo ratings yet

- Human Development NotesDocument6 pagesHuman Development NotesMORALES, V.No ratings yet

- Predicate Calculus AIDocument43 pagesPredicate Calculus AIvepowo LandryNo ratings yet

- Camack ResumeDocument2 pagesCamack Resumeapi-532500926No ratings yet

- Developing Functional Language (A2 Practice)Document55 pagesDeveloping Functional Language (A2 Practice)Roxana Caia GheboianuNo ratings yet

- Bluffing and Betting Behavior in A Simplified Poker GameDocument18 pagesBluffing and Betting Behavior in A Simplified Poker GameDiego GrandonNo ratings yet

- The Functions of Mathematics TextbookDocument4 pagesThe Functions of Mathematics TextbookSangteablacky 09No ratings yet

- Comparing Fractions Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesComparing Fractions Lesson Planapi-352928743No ratings yet

- Blended LearningDocument6 pagesBlended LearningAnnaly SarteNo ratings yet

- Service Learning Assignment: ImagineDocument6 pagesService Learning Assignment: Imagineapi-511159191No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan #01 I. General Information:: Modal Verbs: Can/could, Will/would, Shall/should, Must/have ToDocument4 pagesLesson Plan #01 I. General Information:: Modal Verbs: Can/could, Will/would, Shall/should, Must/have ToSulin CruzNo ratings yet

- Quiz #1 Level 3 A.C 1 Term School Year: Date: 25 / 10 / 2008Document3 pagesQuiz #1 Level 3 A.C 1 Term School Year: Date: 25 / 10 / 2008ACHRAF DOUKARNENo ratings yet

- Midterm ExamDocument12 pagesMidterm ExamLeiza Linda PelayoNo ratings yet