Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

66 viewsCh. 1-1 Definition and Meaning of Tortious Liability

Ch. 1-1 Definition and Meaning of Tortious Liability

Uploaded by

kumar devabrataThe document defines tortious liability and distinguishes torts from breach of contract, crime, and quasi-contracts. It explains that a tort involves the violation of a legal duty owed to people generally, which results in unliquidated damages. This is different from breach of contract, which involves a violation of duties between contracting parties, and from crime, which involves harm against the public. It also defines the "reasonable man" standard used in negligence cases and discusses how motive and malice are generally irrelevant in tort cases, except when an unlawful act is committed.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- TORT LAW Notes 1Document2 pagesTORT LAW Notes 1rs111409No ratings yet

- Chapter 15 - Law of TortDocument25 pagesChapter 15 - Law of TortYi JieNo ratings yet

- Lawoftorts-Notes-160317081339 (TORT NOTES) PDFDocument17 pagesLawoftorts-Notes-160317081339 (TORT NOTES) PDFramu50% (2)

- TortsDocument28 pagesTortsvivek.sharmaNo ratings yet

- MR ImasikuDocument37 pagesMR ImasikuFreddie NsamaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document12 pagesChapter 1Kumar MangalamNo ratings yet

- Tort by Rahul IAS (English)Document100 pagesTort by Rahul IAS (English)Ankit AnandNo ratings yet

- Law of TortsDocument12 pagesLaw of Tortsnagaraju.kasettyNo ratings yet

- The Law of TortsDocument13 pagesThe Law of Torts08 Manu Sharma A S100% (1)

- The Law of TortsDocument18 pagesThe Law of TortsWaseem Afzal100% (1)

- Assignment TortsDocument14 pagesAssignment Tortsusman soomroNo ratings yet

- Development of Torts in IndiaDocument15 pagesDevelopment of Torts in IndiaArkaprava Bhowmik40% (5)

- K - 103 Law of TortDocument34 pagesK - 103 Law of TortPravin Sinha100% (1)

- Tort CrimeDocument21 pagesTort Crimesaumya shahNo ratings yet

- Law of TortsDocument19 pagesLaw of TortsGitika TiwariNo ratings yet

- 3-Law of TortsDocument22 pages3-Law of Tortsdeepti_kawatraNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts New Syllabus 2020Document27 pagesLaw of Torts New Syllabus 2020arjun0505No ratings yet

- TortsDocument8 pagesTortsJOSEPH MALINGONo ratings yet

- Reading 1 Basics of TortDocument13 pagesReading 1 Basics of TortShruti agrawalNo ratings yet

- Definition, Nature & Development of Tort Law-1Document40 pagesDefinition, Nature & Development of Tort Law-1Dhinesh Vijayaraj100% (1)

- Inna FROLOVA. ENGLISH LAW For Students of EnglishDocument10 pagesInna FROLOVA. ENGLISH LAW For Students of EnglishholoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Law of TortsDocument15 pagesIntroduction To The Law of TortssrinivasaNo ratings yet

- Torts Project22Document10 pagesTorts Project22Satyam SoniNo ratings yet

- A. Aims of The Law of Tort: 1. N F L TDocument7 pagesA. Aims of The Law of Tort: 1. N F L TGaurav RaneNo ratings yet

- Tort - Topic 1 Introduction Definition NaDocument13 pagesTort - Topic 1 Introduction Definition NaVishal Singh Jaswal100% (1)

- Bballb 104Document59 pagesBballb 104Soumil RawatNo ratings yet

- Law of TortsDocument28 pagesLaw of TortsSam KariukiNo ratings yet

- Torts Final NotesDocument53 pagesTorts Final Notesnagaraju.kasettyNo ratings yet

- 1 Intro. To TortDocument21 pages1 Intro. To TorttumeloNo ratings yet

- (ICSI Notes) Law of TortsDocument9 pages(ICSI Notes) Law of TortsKedar BhasmeNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts Notes - Prof Bhoomi KatiraDocument80 pagesLaw of Torts Notes - Prof Bhoomi KatiraTanveer Singh NarulaNo ratings yet

- LawoftortrealestatelawDocument18 pagesLawoftortrealestatelawNur AsikinNo ratings yet

- Datius Didace Law of TortsDocument39 pagesDatius Didace Law of TortsKamran RasoolNo ratings yet

- Legal Environment of Business (1jjDocument115 pagesLegal Environment of Business (1jjAnkur ChandraNo ratings yet

- Mid Semester Prep - RohitDocument8 pagesMid Semester Prep - RohitDeeps WadhwaNo ratings yet

- Ch-1 Nature of Torts: How The Law Developed and What Was Need To Create The Law?Document22 pagesCh-1 Nature of Torts: How The Law Developed and What Was Need To Create The Law?HJ ManviNo ratings yet

- Negligence Notes 2022Document26 pagesNegligence Notes 2022Nicholas Freduah KwartengNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts 2020Document84 pagesLaw of Torts 2020Gargi PandeyNo ratings yet

- 01 Nature and Definition of TortDocument5 pages01 Nature and Definition of TortSmriti RoyNo ratings yet

- TORT and ITS ESSENTIALSDocument6 pagesTORT and ITS ESSENTIALSMalik Kaleem AwanNo ratings yet

- Tort (Final)Document10 pagesTort (Final)Rahul VishwakarmaNo ratings yet

- Law of Tort BDocument20 pagesLaw of Tort BSamuel LahatNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Law of TortsDocument7 pagesIntroduction To Law of TortsSia ShawaniNo ratings yet

- 4 Tort Law 2017.2018Document22 pages4 Tort Law 2017.2018Constantin LazarNo ratings yet

- Lecture I - The Law of Torts, The Law of ContractsDocument28 pagesLecture I - The Law of Torts, The Law of ContractsOana Ancuţa CristinoiuNo ratings yet

- Torts:wrongful ActDocument14 pagesTorts:wrongful ActRUDRESH SINGH100% (2)

- Law of Torts Paper 1Document18 pagesLaw of Torts Paper 1Purva KharbikarNo ratings yet

- Ashwin Murthy Torts (1) (1) (18259)Document26 pagesAshwin Murthy Torts (1) (1) (18259)Abhay SinghNo ratings yet

- Torts - NotesDocument35 pagesTorts - NotesIram K KhanNo ratings yet

- Tort Law - An IntroductionDocument111 pagesTort Law - An Introductionahem ahemNo ratings yet

- Essential Feature of TortsDocument18 pagesEssential Feature of TortsUtkarshNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Juridical Sciences COURSE: B.B.A.LL.B. I ST Semester Subject: Law of Torts Subject Code: BBL 106Document4 pagesFaculty of Juridical Sciences COURSE: B.B.A.LL.B. I ST Semester Subject: Law of Torts Subject Code: BBL 106Yash SinghNo ratings yet

- LAW 203 Notes Vol 1Document22 pagesLAW 203 Notes Vol 1Nicholas Freduah KwartengNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Criminal LawDocument13 pagesCivil Law Criminal LawAdityaNo ratings yet

- TORTS-including Consumer Protection Act, 1986 and Motor Vehicles Act, 1988Document10 pagesTORTS-including Consumer Protection Act, 1986 and Motor Vehicles Act, 1988prosenjeet_singhNo ratings yet

- Elements of A Crime: Basic IntroductionDocument17 pagesElements of A Crime: Basic IntroductionUollawNo ratings yet

- Torts AdditionalDocument24 pagesTorts AdditionalMario O Malcolm100% (1)

- Wa0000Document72 pagesWa0000MOTIVATION ARENANo ratings yet

- LAW OF TORT NotesDocument33 pagesLAW OF TORT NotesGaurav Firodiya50% (2)

- Rejection List - Specilaist PDFDocument1,341 pagesRejection List - Specilaist PDFkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

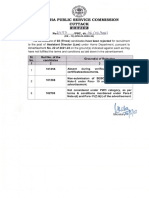

- OCS RescheduleDocument1 pageOCS Reschedulekumar devabrataNo ratings yet

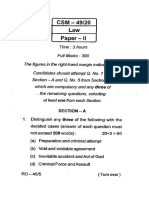

- CSM Law-P IIDocument4 pagesCSM Law-P IIkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- ADL Rejected ListDocument1 pageADL Rejected Listkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Barrack No. L Umt - V Bhubaneswar 751054 2: Odisha Staff Selection Commission No - IIE-100/2019/-55 NoticeDocument1 pageBarrack No. L Umt - V Bhubaneswar 751054 2: Odisha Staff Selection Commission No - IIE-100/2019/-55 Noticekumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- OJS Rejection ListDocument2 pagesOJS Rejection Listkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Faq On Orissa Govt Servants Conduct Rules 1959Document6 pagesFaq On Orissa Govt Servants Conduct Rules 1959kumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Suchismita Das - 16th BatchDocument20 pagesSuchismita Das - 16th Batchkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Unit-I: 1. Various Powers of Courts. What Are The Modes of Conferring and Withdrawals of Powers?Document44 pagesUnit-I: 1. Various Powers of Courts. What Are The Modes of Conferring and Withdrawals of Powers?kumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Prilim ListDocument84 pagesPrilim Listkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Memory AidDocument36 pagesCriminal Procedure Memory AidZainne Sarip BandingNo ratings yet

- Transnational CrimesDocument11 pagesTransnational CrimesSalvador Dagoon Jr0% (1)

- Kebijakan Kriminal KuliahDocument52 pagesKebijakan Kriminal Kuliahnuel ch100% (1)

- Sample Investigative ReportDocument2 pagesSample Investigative ReportJandy PratamaNo ratings yet

- Oscar Suarez's Arrest AffidavitDocument10 pagesOscar Suarez's Arrest AffidavitAmanda RojasNo ratings yet

- Crime MappingDocument8 pagesCrime MappingBimboy CuenoNo ratings yet

- Community Supervision Handbook: Questions and Answers Concerning Release and Community SupervisionDocument41 pagesCommunity Supervision Handbook: Questions and Answers Concerning Release and Community SupervisionWilliamNo ratings yet

- Forum Family Law, Divorce, Custody Child Custody and SupportDocument45 pagesForum Family Law, Divorce, Custody Child Custody and Supportvalerie Runyan HoughtonNo ratings yet

- Esternon, Mariel Q. 3rdyr-OLM10 20180485 Mr. Mabutol, Mark Ryan MDocument3 pagesEsternon, Mariel Q. 3rdyr-OLM10 20180485 Mr. Mabutol, Mark Ryan MSintas Ng SapatosNo ratings yet

- Teodora Altobano-Ruiz Vs Hon. PichayDocument3 pagesTeodora Altobano-Ruiz Vs Hon. PichayDane Pauline AdoraNo ratings yet

- In The Court of District and Session Judge, Saket CourtDocument3 pagesIn The Court of District and Session Judge, Saket CourtAkanksha DubeyNo ratings yet

- People v. DunigDocument9 pagesPeople v. DunigAstrid Gopo BrissonNo ratings yet

- Terry Frisking: The Law, Field Examples and AnalysisDocument6 pagesTerry Frisking: The Law, Field Examples and AnalysisAWhNo ratings yet

- People v. Castro, G.R. No. 172874Document14 pagesPeople v. Castro, G.R. No. 172874Abbie KwanNo ratings yet

- PP v. Norzilan Yaacob & AnorDocument13 pagesPP v. Norzilan Yaacob & AnorSyaheera RosliNo ratings yet

- PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS Criminal Procedure, Defined. Criminal Procedure Has Been Defined AsDocument7 pagesPRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS Criminal Procedure, Defined. Criminal Procedure Has Been Defined Asbfirst122317No ratings yet

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocument5 pages(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowNo ratings yet

- Tan Chor Jin (Document17 pagesTan Chor Jin (Alfred Mujah JimmyNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-7616 May 10, 1955 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, VICTORIO HERNANDEZ, Defendant-AppellantDocument2 pagesG.R. No. L-7616 May 10, 1955 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, VICTORIO HERNANDEZ, Defendant-AppellantMsiNo ratings yet

- Crim - People V Puno - Alyssa AgustinDocument2 pagesCrim - People V Puno - Alyssa AgustinPouǝllǝ ɐlʎssɐNo ratings yet

- CRIM 4 Midterm Exam QuestionerDocument2 pagesCRIM 4 Midterm Exam QuestionerKenneth AlatanNo ratings yet

- Attorney General Elisa Wolfe Donato Exposes WhistleblowerDocument6 pagesAttorney General Elisa Wolfe Donato Exposes WhistleblowerGregTinkerNo ratings yet

- Research Topics 3rd LLB Sem-V 2023-24Document32 pagesResearch Topics 3rd LLB Sem-V 2023-24komalhotchandani1609No ratings yet

- BPOPSDocument30 pagesBPOPSYang Rhea100% (1)

- CRIMINAL JUSTIC-WPS OfficeDocument10 pagesCRIMINAL JUSTIC-WPS OfficeReymond PerezNo ratings yet

- Criminal Investigation Thesis TopicsDocument5 pagesCriminal Investigation Thesis TopicsBuyLiteratureReviewPaperCanada100% (2)

- Anti-Money Laundering Act As AmendedDocument18 pagesAnti-Money Laundering Act As AmendedIan Joshua RomasantaNo ratings yet

- Rule 113 - People V Morial To Rule 114 People V RabaDocument143 pagesRule 113 - People V Morial To Rule 114 People V RabaPre PacionelaNo ratings yet

- People v. Avila, 207 SCRA 1568Document13 pagesPeople v. Avila, 207 SCRA 1568Val SanchezNo ratings yet

- Crime Against Person IIDocument21 pagesCrime Against Person IIallan quintoNo ratings yet

Ch. 1-1 Definition and Meaning of Tortious Liability

Ch. 1-1 Definition and Meaning of Tortious Liability

Uploaded by

kumar devabrata0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

66 views4 pagesThe document defines tortious liability and distinguishes torts from breach of contract, crime, and quasi-contracts. It explains that a tort involves the violation of a legal duty owed to people generally, which results in unliquidated damages. This is different from breach of contract, which involves a violation of duties between contracting parties, and from crime, which involves harm against the public. It also defines the "reasonable man" standard used in negligence cases and discusses how motive and malice are generally irrelevant in tort cases, except when an unlawful act is committed.

Original Description:

Original Title

tort.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe document defines tortious liability and distinguishes torts from breach of contract, crime, and quasi-contracts. It explains that a tort involves the violation of a legal duty owed to people generally, which results in unliquidated damages. This is different from breach of contract, which involves a violation of duties between contracting parties, and from crime, which involves harm against the public. It also defines the "reasonable man" standard used in negligence cases and discusses how motive and malice are generally irrelevant in tort cases, except when an unlawful act is committed.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

66 views4 pagesCh. 1-1 Definition and Meaning of Tortious Liability

Ch. 1-1 Definition and Meaning of Tortious Liability

Uploaded by

kumar devabrataThe document defines tortious liability and distinguishes torts from breach of contract, crime, and quasi-contracts. It explains that a tort involves the violation of a legal duty owed to people generally, which results in unliquidated damages. This is different from breach of contract, which involves a violation of duties between contracting parties, and from crime, which involves harm against the public. It also defines the "reasonable man" standard used in negligence cases and discusses how motive and malice are generally irrelevant in tort cases, except when an unlawful act is committed.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 4

CHAPTER 1

Ch. 1-1 Definition and Meaning of Tortious Liability :

"Tort" comes from "Tortum" which means "to twist". What is twisted is the conduct of the

wrong-doer, called the defendant. Such a twist causes a legal injury (a civil wrong)) to the

plaintiff and the courts provide for a remedy to him in the law of Torts.

"Tortious liability arises from a breach of duty fixed by law. This duty is towards persons

generally and its breach is redressible by an action for unliquidated damages" (Winfield).

Salmond defines tort as a civil wrong for which the remedy is

-•* an action for damages and which is not exclusively a breach of contract

or breach of trust or breach of other merely equitable obligations.

Thus "torts are civil wrongs. But all civil wrongs are not torts". To be a tort, the civil wrong

should have three essentials :-

1. The duty is primarily fixed by law. Law provides for legal rights and legal duties. In fact,

one man's rights are another man's duties. Such legal rights are numerous in number, as for

example, everyone has a right to his reputation, right to property, right to his person etc. On

every other man duties are imposed by law, such duties are numerous in number; Eg. Not to

assault others, not to commit Nuisance, not to slander others, not to deceive others, not to

trespass on other's land, not to defame others etc. The violation of such a legal duty gives

rise to a tortious liability.

2. The legal duty is towards persons generally: The legal duty, for example, not to slander

means not only that slander should not be committed against X or Y but in tort the duty is

considered general, i.e., it is against all persons in the world (in rem). Hence, the legal duty

not to assault, libel, trespass etc., is against all persons in the world.

3. Unliquidated Damages: Damages are divided into liquidated and unliquidated.

'Liquidated', means the amount is pre-estimated and fixed by the parties themselves as

in a contract. Damages are unliquidated when the court, in its discretion, awards

compensation taking into consideration a large number of factors that help to assess the

compensation. In fact, according to winfield action for unliquidated damages, is the

basis of tortious liability. It may be noted that there are other remedies as well. Eg. Self-

defence, temporary or permanent injunction, action for specific restitution of land and

chattels, or abatement of nuisance etc.

Ch. 1-2 Torts Distinct From Breach of Contract:

Torts Breach of Contract

1. In tort, there is an infliction 1. Consent is the basic of an injury without the consent

essential of all contractual of the plaintiff. Consent negatives obligations. In fact, if

liability under "Volenti non fit there is no consent, there injuria", subject to certain is no

contract at all. exceptions. Eg. Rescue cases (Haynes V, Harwood).

2. There is no privity between 2. There is privity of parties. Ex: Donoughue V contract

between the parties Stevenson: the manufacturer of called the contracting

ginger-beer was held liable for parties, negligence to the ultimate consumer.

(Legal neighbour) Another leading case is Grant V. Australian knitting Mills Ltd.

**

3. In the law of torts, thereis a specific violation of a right inrem (right against all

thepersons in the world). Right topersonal safety, right to reputation, breach of contract

to sell.right to property etc., are examples.In case of a contract, thebreach is due to the

violation of a right in personam (a persona] right) Eg. Vendor'sThough the above

distinctions are made out, it cannot be disputed that there are caseswhere torts and

breach of contract overlap eg. A surgeon negligently operating P's minor son.There is no

contract between the surgeon and the father of the minor son, but there is a tort

ofnegligence by the surgeon in relation to the boy.

Ch. 1-3 Torts Distinct From Crime:

Torts

1. In tort, there is an infringement of a civil right or a private right of

the party. Hence, a tort is a private wrong.

2. In tors, the wrong-doer (tort feasor) should pay compensation to the plaintiff

according to the decision of the court.

3. In tort, the affected or injured party may sue.

Crime

1. In crime, there is an infringement of a public right affecting the whole community.

Hence, a crime is public wrong.

2. In crime, the criminal is punished by the state in the interests of the society,

punishment may be death, imprisonment or fine as the case may be.

3. In crime, the state is under a duty to institute criminal proceedings against the

accused.

4. The right to sue or to be 4. The legal action dies with sued survives to the successor. the

person in crimes subject The leading case is Rose V. Ford, to certain exceptions. The maxim

is 'Actio personalis moritur cum persona', (personal action dies with the person).

Ch. 1-4 Tort Distinct from Quasi-Contracts :

a) In tort, there is a primary legal duty fixed by law, but in quasi-contract there is no such

duty. A qualified surgeon who operates on P, owes a legal duty to P, and hence becomes

liable for negligence. In quasi-contract, for example, in unjust enrichment, there is no legal

duty where A delivers goods by mistake to B instead of to C. B is not under a legal duty not

to receive the goods. Of course, B must return the goods to A, but he is not liable to pay

compensation to A.

b) In tort, breach of duty is redressible by an action for dam ages. The damages are

determined by the Courts. There is no such liability in quasi-contracts.

Ch. 1-5 Reasonable Man Explained:

The reasonable man has a reference to the ''Standard of care" fixed by law in negligence or

in other tortious obligations. A reasonable man is a person who exhibits a reasonable

conduct which is the behaviour of an ordinary prudent man in a given set of circumstances.

This is an abstract standard. As Lord Bowen rightly stated "he is a man on the Clapham

Omnibus". "He is not a person who is having the courage of Achilles or the wisdom of

Ulysses or the strength of Hercules." But he is a person who by experience conducts himself

according to the circumstances, as an ordinary prudent man. He shows a degree of skill,

ability or competence which is general in the discharge of functions. He is not a perfect

citizen nor a "paragon of circumspection." Winfield. As Winfield pointed out, the reasonable

man's standard is a guidance to show how a person regulates his conduct. A driver should

have the capacity to drive as an ordinary prudent driver. He need not show the skill of a

surgeon, an advocate, an architect or an engineer. He must show his skill in his own work or

profession. In fact, "a reasonable man is a judicial standard or yardstick which attempts to

reach exactness. This is because complete exactness may not be reached". Hence, the judge

first decides what a reasonable man does and then proceeds to find out whether in the

circumstances of the case, the defendant has acted like a reasonable man. Conflicts do arise

as it is not possible to specify reasonableness in all its exactness, or with specifications.

Reasonableness can be best explained in cases of negligence. Negligence is in fact the

omission to do something which an ordinary prudent man would not do in the

circumstances. Hence, reasonable man is a man who uses ordinary care and skill.

In Daly V. Liverpool Corporation it was held that in deciding whether a 70 year old woman

was negligent in crossing a road, the standard was that of an ordinary prudent women of

her age in the circumstances, and not a hypothetical pedestrian. The standard of conduct is

almost settled since the case of Vaughan V. Manlove. The defendant D's hay stock caught

fire and caused damage to p's cottages. D was held liable as he had not acted like a prudent

man: In the Wagon Mound case (No 1) the test of "reasonable foresight" was applied and

the defendants were held not liable. In fine, a reasonable man is only a legal standard

invented by the courts.

CHAPTER 2

MOTIVE AND MALICE

Ch. 2-1 Motive and malice explained:

The general rule is that motive is irrelevant in torts. Motive denotes the reason for the

conduct of an individual. Thus, if the act is unlawful then mere good motive will not

exonerate it. If the conduct is lawful then a bad motive will not make him liable. The fact

that motive is irrelevant is evident from the leading case: Mayor of BroadFord Corporation

V. Pickles. Here, the corporation refused to purchase the land which belonged to pickles, for

the purpose of the water supply scheme. In revenge, he sank a shaft on his land. In

consequence, the water of the corporation became discoloured and diminished. The

corporation sued pickles. It was held that pickles was not liable. The judge said "we are to

take the man's act into consideration, not the motive behind it". In another case, Allen V.

Flood this was re-stated. In this case, P was appointed by A to make repairs to the ship and

this was terminable at will. D, belonging to an union objected to the appointment and

threatened to go on strike if P was not removed. A dismissed P. P sued D. Held, the motive

of D may be bad but not unlawful and hence not liable. This shows that if the act is lawful,

mere bad motive will not make the act tortious. Malice: It means (1) evil motive and (2) a

wilful act done without just cause or excuse. The rule is that if lawful, evil motive will not

make the act tortious. Further, if the act is good, still the defendant becomes liable if the act

injures and damages the rights of the plaintiff. In Bradford Corporation V. Pickles, the court

observed; 'If the act gives rise to damage without legal injury, then motive however

reprehensible it may be, will not make the act tortious'. In another case (Guive V. Swan), D,

a baloonist landed on the garden of P. People, in large number, entered the garden to see

him, but much damage was done to the vegetables and flowers. P sued D. Held, D had

committed trespass and liable. Though, D had no motive or malice he was held liable.

Exceptions to the rule that Motive is irrelevant: i) Malicious prosecution, ii) Conspiracy.

iii) Deceit or Negligent Misstatements. iv) Some circumstances in Nuisance. (Christie V.

Davey)

Ch. 2-2 Ubi jus ibi remedium:

"Where there is a right, there is a remedy"

According to some jurists, the law of torts had developed from this maxim."Jus" means the

"legal right", to do something, "Remedium" is the right to take action (ie. remedy according

to law). Hence, a person who has a legal right also has the means to vindicate his rights. It is

difficult to imagine a legal right without a legal remedy. In injuria sine damno, there is a legal

remedy available to the plaintiff through the court. But, in cases coming under damnum

sine injuria there is no legal injuria and hence there is no compensation.

Ch. 2-3 Injuria Sine Damno and Damnum Sine Injuria Explained:

'Damnum' is damage in the substantial sense of the term, involving economic loss or loss of

comfort, service, health, or the like. 'Injuria' is legal injury and hence tortious.

Injuria sine Damno: Injuria Sine Damno means "legal injury, without damage". There is an

infringement of a legal right, but no substantial damage or loss, The plaintiff has a cause of

action under section 42 of specific Relief

Ashby V. White:

The defendant, a returning officer, without proper reason refused to register P's vote duly

tendered. Held that the plaintiff had a legal right to vote and that there was a legal injury to

him. Defendant was held liable. The Court observed "every injury imports a damage, though

it may not cost a farthing to the party". Merzette V. william (Bank Case):

In this case without any excuse the Banker refused to honour the cheque presented by a

customer. Held: that the Banker was liable to the drawer. Compensation was paid by the

Bank.

Damnum Sine injuria:

Damnum sine Injuria means actual and substantial loss without the infringement of the legal

right. The actual loss sustained by the plaintiff may be substantial enough, but as no

legal injury has been done to him, no compensation can be recovered.

Chasemore V. Richards:

The defendant D dug a well on his own soil. In consequence, the adjoining owner P's stream

of water dried up and his mill was closed down. P sustained heavy economic loss. Held: No

compensation. There was no legal injury to P but only economic loss.

Gloucester Grammar School:

A teacher who was illegally terminated by Gloucestor school opened a school opposite to it.

The pupils, who loved the teacher joined his school in large numbers. Thereupon the

Gloucestor school was closed. Held; No compensation. Reason: Business competition, and

teacher has not infringed any legal right of the Gloucestor School.

Moghul Steamship Co., V. Mcgregor:

A B C and D four ship owners joined together and offered special terms to the consignors to

book cargo. In consequencee, P a' prosperous steamship company suffered substantial loss,

for which it sued ABC and D for compensation. Held: Not liable. (Business competition and

no legal injury to P).

Dickson V. Reuter Telegraph Company:

A sent a telegram to B to send goods. The telegram was wrongly delivered by the post office

to c. c sent the goods to A. A refused to take the goods. C sued A. Held : No compensation.

Ch. 2-4 Misfeasance Non feasance and Mai feasance:

Misfeasance means doing a lawful act in an improper manner. (Cases in master and

servant). Nonfeasance means not performing or omitting to do that which must be legally

done (cases of negligence). Malfeasance means doing an unlawful act e.g.

trespass.

: (Refer Chapters 4,10 & 14)

You might also like

- TORT LAW Notes 1Document2 pagesTORT LAW Notes 1rs111409No ratings yet

- Chapter 15 - Law of TortDocument25 pagesChapter 15 - Law of TortYi JieNo ratings yet

- Lawoftorts-Notes-160317081339 (TORT NOTES) PDFDocument17 pagesLawoftorts-Notes-160317081339 (TORT NOTES) PDFramu50% (2)

- TortsDocument28 pagesTortsvivek.sharmaNo ratings yet

- MR ImasikuDocument37 pagesMR ImasikuFreddie NsamaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document12 pagesChapter 1Kumar MangalamNo ratings yet

- Tort by Rahul IAS (English)Document100 pagesTort by Rahul IAS (English)Ankit AnandNo ratings yet

- Law of TortsDocument12 pagesLaw of Tortsnagaraju.kasettyNo ratings yet

- The Law of TortsDocument13 pagesThe Law of Torts08 Manu Sharma A S100% (1)

- The Law of TortsDocument18 pagesThe Law of TortsWaseem Afzal100% (1)

- Assignment TortsDocument14 pagesAssignment Tortsusman soomroNo ratings yet

- Development of Torts in IndiaDocument15 pagesDevelopment of Torts in IndiaArkaprava Bhowmik40% (5)

- K - 103 Law of TortDocument34 pagesK - 103 Law of TortPravin Sinha100% (1)

- Tort CrimeDocument21 pagesTort Crimesaumya shahNo ratings yet

- Law of TortsDocument19 pagesLaw of TortsGitika TiwariNo ratings yet

- 3-Law of TortsDocument22 pages3-Law of Tortsdeepti_kawatraNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts New Syllabus 2020Document27 pagesLaw of Torts New Syllabus 2020arjun0505No ratings yet

- TortsDocument8 pagesTortsJOSEPH MALINGONo ratings yet

- Reading 1 Basics of TortDocument13 pagesReading 1 Basics of TortShruti agrawalNo ratings yet

- Definition, Nature & Development of Tort Law-1Document40 pagesDefinition, Nature & Development of Tort Law-1Dhinesh Vijayaraj100% (1)

- Inna FROLOVA. ENGLISH LAW For Students of EnglishDocument10 pagesInna FROLOVA. ENGLISH LAW For Students of EnglishholoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Law of TortsDocument15 pagesIntroduction To The Law of TortssrinivasaNo ratings yet

- Torts Project22Document10 pagesTorts Project22Satyam SoniNo ratings yet

- A. Aims of The Law of Tort: 1. N F L TDocument7 pagesA. Aims of The Law of Tort: 1. N F L TGaurav RaneNo ratings yet

- Tort - Topic 1 Introduction Definition NaDocument13 pagesTort - Topic 1 Introduction Definition NaVishal Singh Jaswal100% (1)

- Bballb 104Document59 pagesBballb 104Soumil RawatNo ratings yet

- Law of TortsDocument28 pagesLaw of TortsSam KariukiNo ratings yet

- Torts Final NotesDocument53 pagesTorts Final Notesnagaraju.kasettyNo ratings yet

- 1 Intro. To TortDocument21 pages1 Intro. To TorttumeloNo ratings yet

- (ICSI Notes) Law of TortsDocument9 pages(ICSI Notes) Law of TortsKedar BhasmeNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts Notes - Prof Bhoomi KatiraDocument80 pagesLaw of Torts Notes - Prof Bhoomi KatiraTanveer Singh NarulaNo ratings yet

- LawoftortrealestatelawDocument18 pagesLawoftortrealestatelawNur AsikinNo ratings yet

- Datius Didace Law of TortsDocument39 pagesDatius Didace Law of TortsKamran RasoolNo ratings yet

- Legal Environment of Business (1jjDocument115 pagesLegal Environment of Business (1jjAnkur ChandraNo ratings yet

- Mid Semester Prep - RohitDocument8 pagesMid Semester Prep - RohitDeeps WadhwaNo ratings yet

- Ch-1 Nature of Torts: How The Law Developed and What Was Need To Create The Law?Document22 pagesCh-1 Nature of Torts: How The Law Developed and What Was Need To Create The Law?HJ ManviNo ratings yet

- Negligence Notes 2022Document26 pagesNegligence Notes 2022Nicholas Freduah KwartengNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts 2020Document84 pagesLaw of Torts 2020Gargi PandeyNo ratings yet

- 01 Nature and Definition of TortDocument5 pages01 Nature and Definition of TortSmriti RoyNo ratings yet

- TORT and ITS ESSENTIALSDocument6 pagesTORT and ITS ESSENTIALSMalik Kaleem AwanNo ratings yet

- Tort (Final)Document10 pagesTort (Final)Rahul VishwakarmaNo ratings yet

- Law of Tort BDocument20 pagesLaw of Tort BSamuel LahatNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Law of TortsDocument7 pagesIntroduction To Law of TortsSia ShawaniNo ratings yet

- 4 Tort Law 2017.2018Document22 pages4 Tort Law 2017.2018Constantin LazarNo ratings yet

- Lecture I - The Law of Torts, The Law of ContractsDocument28 pagesLecture I - The Law of Torts, The Law of ContractsOana Ancuţa CristinoiuNo ratings yet

- Torts:wrongful ActDocument14 pagesTorts:wrongful ActRUDRESH SINGH100% (2)

- Law of Torts Paper 1Document18 pagesLaw of Torts Paper 1Purva KharbikarNo ratings yet

- Ashwin Murthy Torts (1) (1) (18259)Document26 pagesAshwin Murthy Torts (1) (1) (18259)Abhay SinghNo ratings yet

- Torts - NotesDocument35 pagesTorts - NotesIram K KhanNo ratings yet

- Tort Law - An IntroductionDocument111 pagesTort Law - An Introductionahem ahemNo ratings yet

- Essential Feature of TortsDocument18 pagesEssential Feature of TortsUtkarshNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Juridical Sciences COURSE: B.B.A.LL.B. I ST Semester Subject: Law of Torts Subject Code: BBL 106Document4 pagesFaculty of Juridical Sciences COURSE: B.B.A.LL.B. I ST Semester Subject: Law of Torts Subject Code: BBL 106Yash SinghNo ratings yet

- LAW 203 Notes Vol 1Document22 pagesLAW 203 Notes Vol 1Nicholas Freduah KwartengNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Criminal LawDocument13 pagesCivil Law Criminal LawAdityaNo ratings yet

- TORTS-including Consumer Protection Act, 1986 and Motor Vehicles Act, 1988Document10 pagesTORTS-including Consumer Protection Act, 1986 and Motor Vehicles Act, 1988prosenjeet_singhNo ratings yet

- Elements of A Crime: Basic IntroductionDocument17 pagesElements of A Crime: Basic IntroductionUollawNo ratings yet

- Torts AdditionalDocument24 pagesTorts AdditionalMario O Malcolm100% (1)

- Wa0000Document72 pagesWa0000MOTIVATION ARENANo ratings yet

- LAW OF TORT NotesDocument33 pagesLAW OF TORT NotesGaurav Firodiya50% (2)

- Rejection List - Specilaist PDFDocument1,341 pagesRejection List - Specilaist PDFkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- OCS RescheduleDocument1 pageOCS Reschedulekumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- CSM Law-P IIDocument4 pagesCSM Law-P IIkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- ADL Rejected ListDocument1 pageADL Rejected Listkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Barrack No. L Umt - V Bhubaneswar 751054 2: Odisha Staff Selection Commission No - IIE-100/2019/-55 NoticeDocument1 pageBarrack No. L Umt - V Bhubaneswar 751054 2: Odisha Staff Selection Commission No - IIE-100/2019/-55 Noticekumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- OJS Rejection ListDocument2 pagesOJS Rejection Listkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Faq On Orissa Govt Servants Conduct Rules 1959Document6 pagesFaq On Orissa Govt Servants Conduct Rules 1959kumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Suchismita Das - 16th BatchDocument20 pagesSuchismita Das - 16th Batchkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Unit-I: 1. Various Powers of Courts. What Are The Modes of Conferring and Withdrawals of Powers?Document44 pagesUnit-I: 1. Various Powers of Courts. What Are The Modes of Conferring and Withdrawals of Powers?kumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Prilim ListDocument84 pagesPrilim Listkumar devabrataNo ratings yet

- Criminal Procedure Memory AidDocument36 pagesCriminal Procedure Memory AidZainne Sarip BandingNo ratings yet

- Transnational CrimesDocument11 pagesTransnational CrimesSalvador Dagoon Jr0% (1)

- Kebijakan Kriminal KuliahDocument52 pagesKebijakan Kriminal Kuliahnuel ch100% (1)

- Sample Investigative ReportDocument2 pagesSample Investigative ReportJandy PratamaNo ratings yet

- Oscar Suarez's Arrest AffidavitDocument10 pagesOscar Suarez's Arrest AffidavitAmanda RojasNo ratings yet

- Crime MappingDocument8 pagesCrime MappingBimboy CuenoNo ratings yet

- Community Supervision Handbook: Questions and Answers Concerning Release and Community SupervisionDocument41 pagesCommunity Supervision Handbook: Questions and Answers Concerning Release and Community SupervisionWilliamNo ratings yet

- Forum Family Law, Divorce, Custody Child Custody and SupportDocument45 pagesForum Family Law, Divorce, Custody Child Custody and Supportvalerie Runyan HoughtonNo ratings yet

- Esternon, Mariel Q. 3rdyr-OLM10 20180485 Mr. Mabutol, Mark Ryan MDocument3 pagesEsternon, Mariel Q. 3rdyr-OLM10 20180485 Mr. Mabutol, Mark Ryan MSintas Ng SapatosNo ratings yet

- Teodora Altobano-Ruiz Vs Hon. PichayDocument3 pagesTeodora Altobano-Ruiz Vs Hon. PichayDane Pauline AdoraNo ratings yet

- In The Court of District and Session Judge, Saket CourtDocument3 pagesIn The Court of District and Session Judge, Saket CourtAkanksha DubeyNo ratings yet

- People v. DunigDocument9 pagesPeople v. DunigAstrid Gopo BrissonNo ratings yet

- Terry Frisking: The Law, Field Examples and AnalysisDocument6 pagesTerry Frisking: The Law, Field Examples and AnalysisAWhNo ratings yet

- People v. Castro, G.R. No. 172874Document14 pagesPeople v. Castro, G.R. No. 172874Abbie KwanNo ratings yet

- PP v. Norzilan Yaacob & AnorDocument13 pagesPP v. Norzilan Yaacob & AnorSyaheera RosliNo ratings yet

- PRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS Criminal Procedure, Defined. Criminal Procedure Has Been Defined AsDocument7 pagesPRELIMINARY CONSIDERATIONS Criminal Procedure, Defined. Criminal Procedure Has Been Defined Asbfirst122317No ratings yet

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocument5 pages(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowNo ratings yet

- Tan Chor Jin (Document17 pagesTan Chor Jin (Alfred Mujah JimmyNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-7616 May 10, 1955 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, VICTORIO HERNANDEZ, Defendant-AppellantDocument2 pagesG.R. No. L-7616 May 10, 1955 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, VICTORIO HERNANDEZ, Defendant-AppellantMsiNo ratings yet

- Crim - People V Puno - Alyssa AgustinDocument2 pagesCrim - People V Puno - Alyssa AgustinPouǝllǝ ɐlʎssɐNo ratings yet

- CRIM 4 Midterm Exam QuestionerDocument2 pagesCRIM 4 Midterm Exam QuestionerKenneth AlatanNo ratings yet

- Attorney General Elisa Wolfe Donato Exposes WhistleblowerDocument6 pagesAttorney General Elisa Wolfe Donato Exposes WhistleblowerGregTinkerNo ratings yet

- Research Topics 3rd LLB Sem-V 2023-24Document32 pagesResearch Topics 3rd LLB Sem-V 2023-24komalhotchandani1609No ratings yet

- BPOPSDocument30 pagesBPOPSYang Rhea100% (1)

- CRIMINAL JUSTIC-WPS OfficeDocument10 pagesCRIMINAL JUSTIC-WPS OfficeReymond PerezNo ratings yet

- Criminal Investigation Thesis TopicsDocument5 pagesCriminal Investigation Thesis TopicsBuyLiteratureReviewPaperCanada100% (2)

- Anti-Money Laundering Act As AmendedDocument18 pagesAnti-Money Laundering Act As AmendedIan Joshua RomasantaNo ratings yet

- Rule 113 - People V Morial To Rule 114 People V RabaDocument143 pagesRule 113 - People V Morial To Rule 114 People V RabaPre PacionelaNo ratings yet

- People v. Avila, 207 SCRA 1568Document13 pagesPeople v. Avila, 207 SCRA 1568Val SanchezNo ratings yet

- Crime Against Person IIDocument21 pagesCrime Against Person IIallan quintoNo ratings yet