Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pub - Clinical Outline of Oral Pathology Diagnosis and T PDF

Pub - Clinical Outline of Oral Pathology Diagnosis and T PDF

Uploaded by

TOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pub - Clinical Outline of Oral Pathology Diagnosis and T PDF

Pub - Clinical Outline of Oral Pathology Diagnosis and T PDF

Uploaded by

TCopyright:

Available Formats

CLINICAL OUTLINE OF ORAL

PATHOLOGY: DIAGNOSIS

AND TREATMENT

FOURTH EDITION

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd i 1/25/2011 9:48:08 PM

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd ii 1/25/2011 9:48:09 PM

CLINICAL OUTLINE OF ORAL

PATHOLOGY: DIAGNOSIS

AND TREATMENT

FOURTH EDITION

Lewis R. Eversole

2011

PEOPLE’S MEDICAL PUBLISHING HOUSE–USA

SHELTON, CONNECTICUT

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd iii 1/25/2011 9:48:09 PM

People’s Medical Publishing House-USA

2 Enterprise Drive, Suite 509

Shelton, CT 06484

Tel: 203-402-0646

Fax: 203-402-0854

E-mail: info@pmph-usa.com

© 2011 PMPH-USA, Ltd.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher.

11 12 13 14/PMPH/9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN: 978-1-60795-015-8

Printed in China by People’s Medical Publishing House

Editor: Jason Malley; Copyeditor/Typesetter: Newgen

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eversole, Lewis R.

Clinical outline of oral pathology : diagnosis and treatment / Lewis R. Eversole. — 4th ed.

p. ; cm.

ISBN 978-1-60795-015-8

1. Mouth—Diseases. 2. Teeth—Diseases. I. Title.

[DNLM: 1. Diagnosis, Oral. 2. Mouth Diseases—diagnosis. 3. Diagnosis, Differential.

4. Mouth Diseases—therapy. WU 140]

RC815.E9 2010

616.3’1—dc22

2010051383

Sales and Distribution

Canada United Kingdom, Europe, Middle East, Brazil

McGraw-Hill Ryerson Education Africa SuperPedido Tecmedd

Customer Care McGraw Hill Education Beatriz Alves, Foreign Trade Department

300 Water St Shoppenhangers Road R. Sansao Alves dos Santos, 102 | 7th floor

Whitby, Ontario L1N 9B6 Maidenhead Brooklin Novo

Canada Berkshire, SL6 2QL Sao Paolo 04571-090

Tel: 1-800-565-5758 England Brazil

Fax: 1-800-463-5885 Tel: 44-0-1628-502500 Tel: 55-16-3512-5539

www.mcgrawhill.ca Fax: 44-0-1628-635895 www.superpedidotecmedd.com.br

www.mcgraw-hill.co.uk

Foreign Rights India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka,

People’s Medical Publishing House Singapore, Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia

Suzanne Robidoux, Copyright Sales Indonesia, CBS Publishers

Manager Vietnam, Pacific Rim, Korea 4819/X1 Prahlad Street 24

International Trade Department McGraw-Hill Education Ansari Road, Darya Ganj,

No. 19, Pan Jia Yuan Nan Li 60 Tuas Basin Link New Delhi-110002

Chaoyang District Singapore 638775 India

Beijing 100021 Tel: 65-6863-1580 Tel: 91-11-23266861/67

P.R. China Fax: 65-6862-3354 Fax: 91-11-23266818

Tel: 8610-59787337 www.mcgraw-hill.com.sg Email:cbspubs@vsnl.com

Fax: 8610-59787336

www.pmph.com/en/

Australia, New Zealand, Papua People’s Republic of China

New Guinea, Fiji, Tonga, Solomon Islands, People’s Medical Publishing House

Japan Cook Islands International Trade Department

United Publishers Services Limited Woodslane Pty Limited No. 19, Pan Jia Yuan Nan Li

1-32-5 Higashi-Shinagawa Unit 7/5 Vuko Place Chaoyang District

Shinagawa-ku, Tokyo 140-0002 Warriewood NSW 2102 Beijing 100021

Japan Australia P.R. China

Tel: 03-5479-7251 Tel: 61-2-9970-5111 Tel: 8610-67653342

Fax: 03-5479-7307 Fax: 61-2-9970-5002 Fax: 8610-67691034

Email: kakimoto@ups.co.jp www.woodslane.com.au www.pmph.com/en/

Notice: The authors and publisher have made every effort to ensure that the patient care recommended herein, including

choice of drugs and drug dosages, is in accord with the accepted standard and practice at the time of publication. However,

since research and regulation constantly change clinical standards, the reader is urged to check the product information

sheet included in the package of each drug, which includes recommended doses, warnings, and contraindications.

This is particularly important with new or infrequently used drugs. Any treatment regimen, particularly one involving

medication, involves inherent risk that must be weighed on a case-by-case basis against the benefits anticipated. The

reader is cautioned that the purpose of this book is to inform and enlighten; the information contained herein is not

intended as, and should not be employed as, a substitute for individual diagnosis and treatment.

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd iv 1/25/2011 9:48:09 PM

Contents

1. THE DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS 1

Procurement of the Data Base 2 Assessment of the Findings 5

CHIEF COMPLAINT AND HISTORY OF THE Formulating a Differential

PRESENT ILLNESS 2

Diagnosis 5

MEDICAL AND DENTAL HISTORY 3

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION 4 Securing a Definitive Diagnosis 6

RADIOGRAPHIC EXAMINATION 4

CLINICAL LABORATORY TESTS 4 Formulating a Treatment Plan 7

2. WHITE LESIONS 9

Flat Plaques, Solitary 11 PROLIFERATIVE VERRUCOUS

LEUKOPLAKIA 31

FRICTIONAL BENIGN KERATOSES 11 VERRUCOUS CARCINOMA 33

LEUKOPLAKIA 12

ACTINIC CHEILITIS 14 Lacey White Lesions 34

SMOKELESS TOBACCO KERATOSES 14 LICHEN PLANUS 34

SANGUINARIA-INDUCED KERATOSES 16 LICHENOID REACTIONS 36

DYSKERATOSIS CONGENITA 17 LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS 37

FANCONI’S ANEMIA 18

HIV-ASSOCIATED HAIRY LEUKOPLAKIA 38

DYSPLASIA, CARCINOMA IN SITU,

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA, AND Papular Lesions 40

VERRUCOUS CARCINOMA 19

LICHEN PLANUS (HYPERTROPHIC TYPE) 21 KOPLIK SPOTS OF MEASLES 40

MUCOUS PATCHES (SECONDARY FORDYCE’S GRANULES 41

SYPHILIS) 22 DENTAL LAMINA CYSTS, BOHN’S NODULES,

EPSTEIN’S PEARLS 41

Flat Plaques, Bilateral or STOMATITIS NICOTINA 42

Multifocal 23

SPECKLED LEUKOPLAKIA 43

LEUKOEDEMA 23

GENOKERATOSES 24 Pseudomembranous Lesions 44

PLAQUE-FORM LICHEN PLANUS (SEE CHEMICAL BURNS 44

ABOVE) 30

CANDIDIASIS (MONILIASIS, THRUSH) 45

CHEEK/TONGUE BITE KERATOSIS 30

VESICULO-BULLOUS-ULCERATIVE

Verrucous/Rippled Plaques 31 DISEASES 47

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd v 1/25/2011 9:48:09 PM

vi Contents

3. RED AND PIGMENTED LESIONS 49

Focal Erythemas 51 Petechiae 73

NONSPECIFIC (IRRITATIONAL) SUCTION PETECHIAE 73

MUCOSITIS 51 INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS 74

MEDIAN RHOMBOID GLOSSITIS 52 THROMBOCYTE DISORDERS 75

HEMANGIOMA 53 HEREDITARY HEMORRHAGIC

VARIX 54 TELANGIECTASIA 76

ERYTHROPLAKIA 55

Focal Pigmentations 77

Diffuse and Multifocal Red Lesions 56 AMALGAM AND GRAPHITE TATTOO 77

GEOGRAPHIC TONGUE (MIGRATORY MUCOCELE 78

GLOSSITIS) 56 HEMATOMA 79

ERYTHEMA MIGRANS (MIGRATORY NEVUS 80

STOMATITIS) 57 EPHELIS, ORAL MELANOTIC MACULE 81

ATROPHIC GLOSSITIS 58

RADIATION MUCOSITIS 59

Diffuse and Multifocal

Pigmentations 82

XEROSTOMIC MUCOSITIS 60

LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS 61 MALIGNANT MELANOMA 82

ALLERGIC MUCOSITIS, FOREIGN BODY RACIAL PIGMENTATION 83

GINGIVITIS 63 PIGMENTED LICHEN PLANUS 84

BULLOUS/EROSIVE DISEASES 64 PEUTZ-JEGHERS SYNDROME 85

CANDIDIASIS 65 MULTIPLE NEUROFIBROMATOSIS 86

LYMPHONODULAR PHARYNGITIS 67 ADDISON’S DISEASE 87

SCARLET FEVER 67 HEMOCHROMATOSIS 88

ATROPHIC LICHEN PLANUS 68 HIV-ASSOCIATED ORAL

PIGMENTATION 89

ECCHYMOSIS AND CLOTTING FACTOR

DEFICIENCIES 70 HEAVY METAL INGESTION 90

FIELD CANCERIZATION 71 DRUG-INDUCED PIGMENTATION 91

KAPOSI’S SARCOMA 72 HAIRY TONGUE 92

4. ORAL ULCERATIONS AND FISTULAE 95

Recurrent and Multiple ACUTE NECROTIZING ULCERATIVE

GINGIVITIS 105

Ulcerations 96

ACUTE STREPTOCOCCAL/

APHTHOUS STOMATITIS 96 STAPHYLOCOCCAL STOMATITIS 106

MAJOR SCARRING APHTHOUS CHRONIC ULCERATIVE STOMATITIS 107

STOMATITIS 97 GONOCOCCAL STOMATITIS 107

BEHÇET’S SYNDROME 99 HIV PERIODONTITIS AND ORAL

GLUTEN ENTEROPATHY 100 ULCERATIONS 108

AGRANULOCYTOSIS AND

IMMUNOSUPPRESSION 100 Focal Ulcerations 109

CYCLIC NEUTROPENIA 101 TRAUMATIC ULCER 109

UREMIC STOMATITIS 102 TRAUMATIC GRANULOMA WITH STROMAL

VIRAL VESICULAR STOMATITIS 103 EOSINOPHILIA 111

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd vi 1/25/2011 9:48:09 PM

Contents vii

ATYPICAL HISTIOCYTIC GRANULOMA 112 OROANTRAL FISTULA 122

NECROTIZING SIALOMETAPLASIA 113 SOFT TISSUE ABSCESS 123

SPECIFIC GRANULOMATOUS ULCER 114 DEVELOPMENTAL ORAL SINUSES 124

CHANCRE (PRIMARY SYPHILIS) 115 FISSURED (SCROTAL) TONGUE 125

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA 116

Perioral and Commissural Necrotic and Osseous Destructive

Lesions 126

Ulcerations and Fistulae 117

FACTITIAL INJURY AND TRAUMA 126

COMMISSURAL PITS 117

WEGENER’S GRANULOMATOSIS 127

CONGENITAL LIP PITS 118

EXTRANODAL NK/T-CELL LYMPHOMA 128

ANGULAR CHEILITIS 119

TERTIARY SYPHILIS 129

Oral Fistulae 120 OSTEORADIONECROSIS 130

PERIAPICAL ABSCESS AND MUCORMYCOSIS 131

OSTEOMYELITIS 120 ANTRAL CARCINOMA 132

PERIODONTAL ABSCESS 121 BISPHOSPHONATE-RELATED

ACTINOMYCOSIS 122 OSTEONECROSIS OF THE JAWS 133

5. VESICULOBULLOUS AND DESQUAMATIVE LESIONS 137

Febrile-Associated Vesicular BULLOUS PEMPHIGOID 151

Eruptions 139 BENIGN MUCOUS MEMBRANE

PEMPHIGOID 152

HERPETIC GINGIVOSTOMATITIS 139 BULLOUS LICHEN PLANUS 154

HERPANGINA 140 ERYTHEMA MULTIFORME 155

HAND-FOOT-AND-MOUTH DISEASE 141 STEVENS-JOHNSON SYNDROME 156

PRIMARY VARICELLA-ZOSTER PARANEOPLASTIC PEMPHIGUS 157

(CHICKENPOX) 143 ANGINA BULLOSA HEMORRHAGICA 158

SECONDARY VARICELLA-ZOSTER EPIDERMOLYSIS BULLOSA 159

(SHINGLES) 144 DERMATITIS HERPETIFORMIS (GLUTEN

Nonfebrile-Associated Vesicular ENTEROPATHY) 161

Eruptions 145 Desquamative Lesions 161

RECURRENT HERPES STOMATITIS 145 GINGIVOSIS (DESQUAMATIVE

RECURRENT HERPES LABIALIS 146 GINGIVITIS) 161

CONTACT VESICULAR STOMATITIS 148 EROSIVE LICHEN PLANUS 163

IMPETIGO 149 LICHENOID CONTACT STOMATITIS 164

CHRONIC ULCERATIVE STOMATITIS 165

Bullous Diseases 150

PYOSTOMATITIS VEGETANS 166

PEMPHIGUS VULGARIS 150 TOOTHPASTE IDIOSYNCRATIC LESIONS 168

6. INTRAORAL SOFT TISSUE SWELLINGS 171

Localized Gingival Tumefactions 173 PERIPHERAL GIANT CELL GRANULOMA 176

PERIPHERAL FIBROMA 177

PARULIS 173 GIANT CELL FIBROMA 178

PYOGENIC GRANULOMA 175 PERIPHERAL OSSIFYING FIBROMA 179

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd vii 1/25/2011 9:48:09 PM

viii Contents

JUVENILE SPONGIOTIC GINGIVAL CHEILITIS GLANDULARIS 217

HYPERPLASIA 180 ANGIONEUROTIC EDEMA 218

RETROCUSPID PAPILLAE 181 ACTINIC PRURIGO 219

TORUS MANDIBULARIS AND INFLAMMATORY FIBROUS HYPERPLASIA 220

EXOSTOSES 181 FOREIGN BODY GRANULOMA 220

GINGIVAL CYST 183 CROHN’S DISEASE 221

ERUPTION CYST 184 TRAUMATIC FIBROMA 222

EPULIS FISSURATA 185 TRAUMATIC (AMPUTATION) NEUROMA 224

CONGENITAL EPULIS 185 MESENCHYMAL NEOPLASMS 224

MESENCHYMAL TUMORS 187 HERNIATED BUCCAL FAT PAD 225

PERIPHERAL ODONTOGENIC TUMORS 188 REACTIVE LYMPHOID HYPERPLASIA 226

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA 189 HEMANGIOMA AND VARIX 227

SARCOMAS 190 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA 229

MUCOEPIDERMOID CARCINOMA 191 MONOMORPHIC ADENOMA 230

NON-HODGKIN’S LYMPHOMA 192 OTHER SALIVARY NEOPLASMS 231

METASTATIC CARCINOMA 193

LANGERHANS CELL HISTIOCYTOSIS 194 Tongue Swellings 232

Generalized Gingival Swellings 195 MEDIAN RHOMBOID GLOSSITIS 232

ECTOPIC LINGUAL THYROID 233

FIBROMATOSIS GINGIVAE 195 THYROGLOSSAL DUCT CYST 234

DRUG INDUCED HYPERPLASIA 196 LINGUAL CYST (ENTEROCYSTOMA, GASTRIC

NONSPECIFIC HYPERPLASTIC CYST) 235

GINGIVITIS 197 HYPERPLASTIC LINGUAL TONSIL 236

WEGENER’S GRANULOMATOSIS 198 LINGUAL ABSCESS 237

TYPE I DIABETES MELLITUS 199 REACTIVE LESIONS (FIBROMA, PYOGENIC

PUBERTY/PREGNANCY GINGIVITIS 200 GRANULOMA) 237

LEUKEMIA 201 MUCOCELE 238

Swellings of the Oral Floor 202 HEMANGIOMA AND LYMPHANGIOMA 239

NEURAL SHEATH TUMORS 241

RANULA AND SIALOCYSTS 202 GRANULAR CELL TUMOR 242

DISONTOGENIC CYSTS 203 LEIOMYOMA 243

LYMPHOEPITHELIAL CYST 204 OSTEOCARTILAGINOUS CHORISTOMA 244

SIALOLITHIASIS WITH SIALADENITIS 205 ECTOMESENCHYMAL CHONDROMYXOID

SALIVARY GLAND TUMORS 207 TUMOR 245

ADENOMATOID HYPERPLASIA 207 SARCOMAS 245

MESENCHYMAL NEOPLASMS 208 AMYLOID NODULES 246

LUDWIG’S ANGINA 209 SPECIFIC GRANULOMA 247

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA 210 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA 248

Swellings of the Lips and Buccal Palatal Swellings 250

Mucosa 211 TORUS PALATINUS 250

MUCOUS RETENTION (EXTRAVASATION) CYST OF THE INCISIVE PAPILLA 251

PHENOMENON (MUCOCELE) 211 PALATAL ABSCESS 251

SIALOCYST 213 REACTIVE LESIONS OF PALATAL

MINOR GLAND SIALOLITHIASIS 214 GINGIVAL 252

NASOALVEOLAR (KLESTADT) CYST 215 ADENOMATOUS HYPERPLASIA 252

CHEILITIS GRANULOMATOSA 216 PLEOMORPHIC ADENOMA 253

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd viii 1/25/2011 9:48:09 PM

Contents ix

POLYMORPHOUS LOW-GRADE ADENOCARCINOMA, NOS 259

ADENOCARCINOMA 254 ATYPICAL LYMPHOPROLIFERATIVE

MISCELLANEOUS ADENOCARCINOMAS 255 DISEASE 259

ADENOID CYSTIC CARCINOMA 256 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA 261

MUCOEPIDERMOID CARCINOMA 258 CARCINOMA OF THE ANTRUM 262

7. PAPILLARY, PAPULAR, AND MULTIPLE POLYPOID LESIONS 265

Focal Papillary Lesions 267 PAPILLARY SQUAMOUS CELL

CARCINOMA 281

PAPILLOMA 267

VERRUCA VULGARIS 268

Diffuse Papular and Polypoid

Lesions 282

CONDYLOMA ACUMINATUM 269

VERRUCIFORM XANTHOMA 270 PAPILLARY HYPERPLASIA 282

SIALADENOMA PAPILLIFERUM 271 STOMATITIS NICOTINA 283

GIANT CELL FIBROMA 272 ACUTE LYMPHONODULAR

SQUAMOUS ACANTHOMA 273 PHARYNGITIS 284

KERATOSIS FOLLICULARIS 284

Focal and Umbilicated Papules 273 FOCAL EPITHELIAL HYPERPLASIA

(HECK’S DISEASE) 285

KERATOACANTHOMA 273

MULTIPLE HAMARTOMA (COWDEN)

WARTY DYSKERATOMA 274

SYNDROME 286

MOLLUSCUM CONTAGIOSUM 275 PYOSTOMATITIS VEGETANS 287

Diffuse and Multifocal Papillary CROHN’S DISEASE 288

Lesions 276 SPECIFIC GRANULOMATOUS

INFECTIONS 289

FOCAL DERMAL HYPOPLASIA (GOLTZ AMYLOIDOSIS 290

SYNDROME) 276 HYALINOSIS CUTIS ET MUCOSAE

NEVUS UNIUS LATERIS 277 (LIPOID PROTEINOSIS) 291

ACANTHOSIS NIGRICANS 278 HEMANGIOMA/LYMPHANGIOMA 292

ATYPICAL VERRUCOUS MULTIPLE ENDOCRINE NEOPLASIA,

LEUKOPLAKIA 278 TYPE IIB 293

VERRUCOUS CARCINOMA 280 DENTAL LAMINA CYSTS 294

8. SOFT TISSUE SWELLINGS OF THE NECK AND FACE 297

Lateral Neck Swellings 300 ACTINOMYCOSIS 306

REACTIVE PROLIFERATIONS 307

BRANCHIAL CLEFT CYST 300 SINUS HISTIOCYTOSIS 308

CERVICAL RIB AND TRANSVERSE BENIGN MESENCHYMAL TUMORS 309

PROCESS 301 CYSTIC HYGROMA (LYMPHANGIOMA) 310

NONSPECIFIC LYMPHADENITIS 301 CAROTID BODY TUMOR

INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS 303 (CHEMODECTOMA) 311

TUBERCULOUS LYMPHADENITIS METASTATIC CARCINOMA 312

(SCROFULA) 304 SARCOMAS 314

CAT-SCRATCH FEVER 305 MALIGNANT LYMPHOMA 315

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd ix 1/25/2011 9:48:10 PM

x Contents

Unilateral Parotid and DYSGENETIC CYSTS OF THE PAROTID 338

Submandibular Swellings 316 METABOLIC SIALADENOSIS 339

ACUTE SIALADENITIS (SURGICAL Midline Neck Swellings 340

MUMPS) 316

THYROGLOSSAL TRACT CYST 340

SIALOLITHIASIS AND OBSTRUCTIVE

GOITER 341

SIALADENITIS 317

CHRONIC SIALADENITIS 318 THYROID NEOPLASIA 342

INTRAPAROTID MESENCHYMAL DERMOID CYST 343

TUMORS 319

LYMPHOMA 320

Growths and Swellings of the

Facial Skin 344

PLEOMORPHIC ADENOMA 322

PAPILLARY CYSTADENOMA NEVI 344

LYMPHOMATOSUM 323 SEBACEOUS CYST 345

ONCOCYTOMA 324 SEBORRHEIC KERATOSIS 346

MISCELLANEOUS ADENOMAS 325 ADNEXAL SKIN TUMORS 347

ADENOID CYSTIC CARCINOMA 326 BASAL CELL CARCINOMA 348

MUCOEPIDERMOID CARCINOMA 327 SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA 350

ACINIC CELL CARCINOMA 329 KERATOACANTHOMA 351

ADENOCARCINOMA NOS AND MESENCHYMAL TUMORS 352

MISCELLANEOUS MALIGNANCIES 330

MALIGNANT MELANOMA 353

Bilateral Parotid and Submandibular

Swellings 332

Diffuse Facial Swellings 354

CELLULITIS AND SPACE INFECTIONS 354

ENDEMIC PAROTITIS (MUMPS) 332

SJÖGREN’S SYNDROME 333 EMPHYSEMA 355

MIKULICZ’S DISEASE 334 ANGIONEUROTIC EDEMA 356

SARCOID SIALADENITIS AND HEERFORDT’S CUSHING’S SYNDROME 357

SYNDROME 335 FACIAL HEMIHYPERTROPHY 358

TUBERCULOSIS 336 FIBROUS DYSPLASIA AND OTHER BONE

HIV SALIVARY DISEASE (DIFFUSE INFILTRATIVE LESIONS 359

LYMPHOCYTOSIS SYNDROME) 337 MASSETERIC HYPERTROPHY 360

9. RADIOLUCENT LESIONS OF THE JAWS 363

Periapical Radiolucencies 366 STATIC BONE CYST (SUBMANDIBULAR

GLAND DEPRESSION) 377

APICAL PERIODONTITIS (ABSCESS, SUBLINGUAL GLAND DEPRESSION 377

GRANULOMA, AND CYST) 366 PARADENTAL (BUCCAL INFECTED)

PERIAPICAL CEMENTAL DYSPLASIA 367 CYST 379

FOCAL CEMENTO-OSSEOUS CENTRAL GIANT CELL GRANULOMA 380

DYSPLASIA 369 MALIGNANCIES 380

FOCAL SCLEROSING OSTEOMYELITIS 371

BENIGN CEMENTOBLASTOMA 371 Interradicular Radiolucencies 383

INCISIVE CANAL CYST 372 LATERAL PERIODONTAL CYST 383

MEDIAN MANDIBULAR CYST 375 LATERALLY DISPLACED APICAL

TRAUMATIC (HEMORRHAGIC) CYST 375 PERIODONTAL CYST OR GRANULOMA 384

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd x 1/25/2011 9:48:10 PM

Contents xi

RESIDUAL CYST 385 Multilocular Radiolucencies 423

ODONTOGENIC KERATOCYST 386

PRIMORDIAL CYST 386 ODONTOGENIC KERATOCYST 423

CALCIFYING CYSTIC ODONTOGENIC BOTRYOID ODONTOGENIC CYST 425

TUMOR 388 GLANDULAR ODONTOGENIC CYST 425

SQUAMOUS ODONTOGENIC TUMOR 389 CHERUBISM (FAMILIAL FIBROUS

SURGICAL CILIATED CYST 391 DYSPLASIA) 427

OSTEOPOROTIC BONE MARROW CENTRAL GIANT CELL GRANULOMA 429

DEFECT 392 ANEURYSMAL BONE CYST 429

CENTRAL OSSIFYING (CEMENTIFYING) HYPERPARATHYROIDISM 431

FIBROMA 393 AMELOBLASTOMA 432

ODONTOGENIC ADENOMATOID MYXOMA 433

TUMOR 394 CENTRAL NEUROGENIC NEOPLASMS 434

ODONTOGENIC FIBROMA 396 CENTRAL ARTERIOVENOUS

CENTRAL GIANT CELL GRANULOMA 397 MALFORMATION 436

Periodontal (Alveolar) Bone Loss 398 CENTRAL (LOW FLOW) HEMANGIOMA OF

BONE 437

CHRONIC PERIODONTITIS 398 CENTRAL LEIOMYOMA 438

DIABETIC PERIODONTITIS 400 PSEUDOTUMOR OF HEMOPHILIA 439

JUVENILE PERIODONTITIS AND PAPILLON- MYOFIBROMATOSIS (DESMOPLASTIC

LEFEVRE SYNDROME 401 FIBROMA OF BONE) 440

VANISHING BONE DISEASE (MASSIVE FIBROUS DYSPLASIA 442

OSTEOLYSIS) 402 INTRAOSSEOUS MUCOEPIDERMOID

LANGERHANS CELL HISTIOCYTOSIS 403 CARCINOMA 443

CYCLIC NEUTROPENIA 405 THALASSEMIA MAJOR 443

LEUKEMIA 406

Moth-Eaten Radiolucencies 443

Widened Periodontal Ligament OSTEOMYELITIS 443

Space 407

OSTEORADIONECROSIS 445

PERIODONTIC/ENDODONTIC BISPHOSPHONATE-RELATED

INFLAMMATION 407 OSTEONECROSIS OF THE JAWS

SCLERODERMA 409 (BRONJ) 446

OSTEOGENIC SARCOMA 410 PRIMARY INTRAOSSEOUS CARCINOMA 448

CYSTOGENIC CARCINOMA 449

Pericoronal Radiolucencies 411

METASTATIC CARCINOMA 450

DENTIGEROUS CYST 411 MALIGNANT ODONTOGENIC TUMORS 452

ODONTOGENIC KERATOCYST 413 OSTEOSARCOMA AND

GLANDULAR ODONTOGENIC CYST 414 CHONDROSARCOMA 453

UNICYSTIC AMELOBLASTOMA 414 EWING’S SARCOMA 455

CALCIFYING EPITHELIAL ODONTOGENIC PRIMARY LYMPHOMA OF BONE 456

TUMOR 417 BURKITT’S LYMPHOMA 457

ODONTOGENIC ADENOMATOID FIBROGENIC AND NEUROGENIC

TUMOR 417 SARCOMA 458

AMELOBLASTIC FIBROMA 419 MELANOTIC NEUROECTODERMAL TUMOR

ODONTOGENIC FIBROMA-LIKE OF INFANCY 459

HAMARTOMA/ENAMEL HYPOPLASIA 420

CENTRAL MUCOEPIDERMOID

Multifocal Radiolucencies 461

CARCINOMA 421 BASAL CELL NEVUS SYNDROME 461

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd xi 1/25/2011 9:48:10 PM

xii Contents

LANGERHANS CELL HISTIOCYTOSIS 462 SENILE OSTEOPOROSIS 466

MULTIPLE MYELOMA 463 STEROID OSTEOPOROSIS 467

SICKLE CELL ANEMIA 468

Generalized Osteoporotic THALASSEMIA MAJOR 469

Lesions 465

OSTEOMALACIA 465

10. RADIOPAQUE LESIONS OF THE JAWS 473

Periapical Radiopacities 475 ANTRAL INVASIVE MYCOSES 506

FUNGUS BALL (ASPERGILLUS

PERIAPICAL CEMENTAL DYSPLASIA 475 MYCETOMA) 507

FOCAL CEMENTO-OSSEOUS DYSPLASIA 477 ALLERGIC FUNGAL SINUSITIS 508

FOCAL SCLEROSING OSTEOMYELITIS 479 DISPLACED TEETH, ROOTS, AND FOREIGN

FOCAL PERIAPICAL OSTEOSCLEROSIS 480 BODIES 509

BENIGN CEMENTOBLASTOMA 481 AUGMENTATION MATERIALS 510

ANTROLITH/RHINOLITH 511

Inter-Radicular Radiopacities 482

ODONTOGENIC TUMORS 512

RESIDUAL FOCAL OSTEITIS AND OSTEOMAS AND EXOSTOSES 513

CEMENTOMA 482 BENIGN MESENCHYMAL NEOPLASMS 515

IDIOPATHIC OSTEOSCLEROSIS 483 INVERTING PAPILLOMA 516

BISPHOSPHONATE-RELATED ANTRAL CARCINOMA 517

OSTEONECROSIS OF THE JAWS 484 ANTRAL SARCOMA 519

CALCIFYING AND KERATINIZING EPITHELIAL SILENT SINUS SYNDROME 520

ODONTOGENIC CYST/TUMOR 486

ODONTOGENIC ADENOMATOID Ground-Glass Radiopacities 521

TUMOR 486

ODONTOMA 489 FIBROUS DYSPLASIA 521

CENTRAL OSSIFYING OR CEMENTIFYING CHRONIC DIFFUSE SCLEROSING

FIBROMA 489 OSTEOMYELITIS 523

BENIGN OSTEOBLASTOMA 492 OSTEITIS DEFORMANS (PAGET’S DISEASE OF

BONE) 524

Pericoronal Radiopacities 493 HYPERPARATHYROIDISM 526

SEGMENTAL ODONTOMAXILLARY

ODONTOGENIC ADENOMATOID

DYSPLASIA 528

TUMOR 493

OSTEOPETROSIS 529

CALCIFYING EPITHELIAL ODONTOGENIC

TUMOR 494 Multifocal Confluent (Cotton-Wool)

AMELOBLASTIC FIBRODENTINOMA 496 Radiopacities 530

AMELOBLASTIC FIBRO-ODONTOMA 497

ODONTOMA 498 OSTEITIS DEFORMANS (PAGET’S DISEASE OF

ODONTOAMELOBLASTOMA 499 BONE) 530

FLORID OSSEOUS DYSPLASIA 531

Antral Opacities 500 GARDNER’S SYNDROME 533

MAXILLARY SINUSITIS 500 FAMILIAL GIGANTIFORM CEMENTOMA 534

ANTRAL POLYP 502 Cortical Redundancies (Onion-Skin

SINUS MUCOCELE 503 Patterns) 536

PERIAPICAL INFECTION WITH ANTRAL

POLYPS 504 GARRÉ’S PERIOSTITIS 536

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd xii 1/25/2011 9:48:10 PM

Contents xiii

INFANTILE CORTICAL HYPEROSTOSIS 537 OSTEOGENIC AND CHONDROGENIC

GENERALIZED CORTICAL SARCOMA 545

HYPEROSTOSIS 538 METASTATIC CARCINOMA 546

JUXTACORTICAL OSTEOGENIC

SARCOMA 539

Superimposed Soft Tissue

Radiopacities 547

OSTEOID OSTEOMA 540

MANDIBULAR TORI AND EXOSTOSES 541 SIALOLITHIASIS 547

PHLEBOLITHIASIS 548

Irregular, Ill-Defined Expansile OSSEOUS/CARTILAGINOUS

Radiopacities 542 CHORISTOMA 549

CALCIFYING EPITHELIAL ODONTOGENIC FOREIGN BODIES 550

TUMOR 542 CALCIFIED LYMPH NODES 551

DESMOPLASTIC AMELOBLASTOMA 543 MYOSITIS OSSIFICANS 552

11. DENTAL DEFECTS 555

Alterations in Number: Missing EROSION 575

Teeth 558 HYPERCEMENTOSIS 576

HYPODONTIA 558 Alterations in Structure 577

INCONTINENTIA PIGMENTI 559 DENTAL CARIES 577

HYALINOSIS CUTIS ET MUCOSAE 559 ENAMEL HYPOPLASIA 579

MANDIBULO-OCULO-FACIAL CONGENITAL SYPHILIS 580

DYSCEPHALY 560

DENTAL FLUOROSIS 581

HEREDITARY ECTODERMAL DYSPLASIA 560

SNOW-CAPPED TEETH 582

CHONDROECTODERMAL DYSPLASIA 561

AMELOGENESIS IMPERFECTA, HYPOPLASTIC

Alterations in Number: TYPES 582

Supernumerary Teeth 562 AMELOGENESIS IMPERFECTA,

HYPOMATURATION/HYPOCALCIFICATION

HYPERDONTIA 562 TYPES 584

CLEIDOCRANIAL DYSPLASIA 563 SYNDROME-ASSOCIATED ENAMEL

GARDNER’S SYNDROME 564 DEFECTS 585

DENTINOGENESIS IMPERFECTA 587

Alterations in Morphology 565

OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA 588

MICRODONTIA AND MACRODONTIA 565 DENTIN DYSPLASIA TYPE I 589

ACCESSORY CUSPS AND ROOTS 566 DENTIN DYSPLASIA TYPE II 590

DENTAL TRANSPOSITION 567 REGIONAL ODONTODYSPLASIA 591

ENAMEL PEARL 568 HYPOPHOSPHATASIA 593

DILACERATION 568 VITAMIN D REFRACTORY RICKETS 593

DENS INVAGINATUS (DENS IN DENTE) 570 DENTICLES AND PULP CALCIFICATION 595

TAURODONTISM 571 SEGMENTAL ODONTOMAXILLARY

GEMINATION 571 DYSPLASIA 595

FUSION 572 INTERNAL RESORPTION 597

CONCRESCENCE 573 EXTERNAL RESORPTION 598

ATTRITION 574 SUBCERVICAL RESORPTION 599

ABRASION 575 CORONAL FRACTURE 600

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd xiii 1/25/2011 9:48:10 PM

xiv Contents

Alterations in Eruption/Exfoliation BILIARY ATRESIA 604

Times 601 POSTMORTEM PINK TEETH 605

PORPHYRIA 605

PREMATURE ERUPTION 601 DENTAL FLUOROSIS 606

DELAYED ERUPTION 601 TETRACYCLINE STAINING 607

IMPACTION 602 EXTRINSIC STAINING 608

PREMATURE EXFOLIATION 603 FOCAL PIGMENTATION 609

Pigmentations 603

ERYTHROBLASTOSIS FETALIS 603

12. FACIAL PAIN AND NEUROMUSCULAR DISORDERS 611

Ophthalmic Division Pain 614 Neck and Throat Pain 638

ODONTOGENIC INFECTION 614 STYLOHYOID SYNDROME (EAGLE’S

FRONTAL/ETHMOIDAL SINUSITIS 615 SYNDROME) 638

VASCULAR OCCLUSIVE DISEASE AND HYOID SYNDROME 638

ANEURYSMS 616 GLOSSOPHARYNGEAL NEURALGIA 639

CAROTIDYNIA 640

Maxillary Division Pain 616

SUPERIOR LARYNGEAL NEURALGIA 641

ODONTOGENIC INFECTION 616 LARYNGEAL NEOPLASMS 641

MAXILLARY SINUSITIS 617

PATHOLOGIC JAWBONE CAVITIES 619 TMJ Region Pain 642

ANTRAL AND MAXILLARY NEOPLASMS 620 MYOGENIC PAIN 642

CLUSTER HEADACHE 621 TYPE I INTERNAL DERANGEMENT

TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA 623 (REDUCING) 644

POSTHERPETIC NEURALGIA 624 TYPE II INTERNAL DERANGEMENT

COMPLEX REGIONAL PAIN SYNDROME (TRANSIENT LOCK) 646

(CAUSALGIA) 625 TYPE III INTERNAL DERANGEMENT (CLOSED

CRANIAL BASE AND CNS NEOPLASMS 626 LOCK) 647

ATYPICAL FACIAL PAIN 628 MENISCUS PERFORATION 648

OSTEOARTHRITIS (DEGENERATIVE JOINT

Mandibular Division Pain 629 DISEASE) 649

ODONTOGENIC INFECTION 629 RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS 650

OSTEOMYELITIS 630 ACUTE INFECTIOUS ARTHRITIDES 651

TRAUMATIC NEUROMA 631 MISCELLANEOUS ARTHRITIDES 652

SUBACUTE THYROIDITIS 632 CONDYLAR FRACTURE 653

STOMATODYNIA/GLOSSOPYROSIS 633 SYNOVIAL CHONDROMATOSIS 654

CARDIOGENIC FACIAL PAIN 634 PIGMENTED VILLONODULAR

SYNOVITIS 655

Otogenic Pain 634

ACUTE OTITIS MEDIA 634

Sialogenic Pain 656

CHRONIC OTITIS MEDIA 635 SIALOLITHIASIS 656

HERPES ZOSTER OTICUS 636 ENDEMIC PAROTITIS (MUMPS) 657

MIDDLE EAR NEOPLASMS 637 ACUTE SUPPURATIVE SIALADENITIS 658

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd xiv 1/25/2011 9:48:10 PM

Contents xv

Temporal Pain 659 CONVERSION TRISMUS 671

ANKYLOSIS 671

MIGRAINE 659 HECHT-BEALS-WILSON SYNDROME 672

MYOGENIC PAIN (TENSION HEADACHE) 659 CORONOID HYPERPLASIA 673

GIANT CELL ARTERITIS 660 CONDYLAR HYPERPLASIA 673

Paresthesia 661 TMJ REGION NEOPLASMS 674

SCLERODERMA 676

MENTAL PARESTHESIA 661

ORAL SUBMUCOUS FIBROSIS 676

INFRAORBITAL PARESTHESIA 662

TETANUS 677

Localized Motor Deficits 664

Generalized Motor Function

FACIAL PARALYSIS 664 Disorders 678

HORNER’S SYNDROME 665

OPHTHALMOPLEGIA 666 AURICULOTEMPORAL SYNDROME 678

HYPOGLOSSAL PARALYSIS 667 JAW-WINKING PHENOMENON 679

SOFT PALATE PARALYSIS 668 MOTOR SYSTEM DISEASE 680

MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS 680

Limited and Deviant Mandibular MUSCULAR DYSTROPHIES 681

Opening 669 MYOTONIAS 682

MUSCLE SPLINTING 669 CONGENITAL FACIAL DIPLEGIA 683

POSTINJECTION/POSTINFECTION HEMIFACIAL ATROPHY 683

TRISMUS 670 MYASTHENIA GRAVIS 684

Appendix I 685

Appendix II 688

Appendix III 688

Appendix IV 689

Appendix V 694

Index 701

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd xv 1/25/2011 9:48:10 PM

PMPH_Eversole_FM.indd xvi 1/25/2011 9:48:11 PM

The Diagnostic

Process 1

Procurement of the Data Base 2

CHIEF COMPLAINT AND HISTORY OF THE PRESENT ILLNESS 2

MEDICAL AND DENTAL HISTORY 3

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION 4

RADIOGRAPHIC EXAMINATION 4

CLINICAL LABORATORY TESTS 4

Assessment of the Findings 5

Formulating a Differential Diagnosis 5

Securing a Definitive Diagnosis 6

Formulating a Treatment Plan 7

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-01.indd 1 1/17/2011 3:22:30 PM

The diagnostic process involves four sequen-

tial steps: (1) obtainment of a comprehensive Procurement of the Data Base

overview of the patient’s past and current

health status, referred to as the historical CHIEF COMPLAINT AND

data base; (2) evaluation of all the findings HISTORY OF THE PRESENT

to correlate the chief sign or symptoms with ILLNESS

the current history, other physical findings,

and the medical history; (3) formulation of a The initial contact with the patient should be

differential diagnosis to include all disease met with concern conveying a desire to be of

processes that could conceivably account assistance. Patients are often upset, fearful,

for the collective findings; and (4) arrival at annoyed, or short-tempered when they feel

a definitive diagnosis on the basis of inter- they are ill or have something wrong with

rogation and specific clinical and laboratory them, particularly when pain is the primary

tests that exclude specific diseases and point complaint or when they have sought help

to a definite disease process. Once the diag- from other health practitioners who were

nostic process is consummated, a plan for unable to arrive at a diagnosis. Nonverbal

treatment can be generated with establish- communication such as a hand on the

ment of a follow-up assessment program. shoulder, a look of kindness, or a comment

Thorough and open communication expressing concern and determination to

between doctor and patient is a prereq- help will open the doors to trust and com-

uisite to the diagnostic process. Because munication. Once these subtle gestures have

the ultimate goal is the definitive diagno- helped to establish rapport, an assessment

sis, the doctor is charged with the duty of of the patient’s problem or chief complaint

sleuth par excellence, meaning he or she can be explored. The chief complaint usu-

must develop the communication skills to ally emerges as a symptom, a sign, or both.

become an eminent interrogator. The ques- Symptoms are subjective, represent-

tioning process is as important as having ing a definite problem expressed by the

a large knowledge base regarding disease patient. Common symptoms of oral and

processes and the skills necessary to recog- maxillofacial disease processes include the

nize tissue changes. The process of interro- following:

gation helps to exclude diseases that, on the

basis of physical appearance or symptoms Discomfort: Pain, ache, numbness (hyp-

alone, would have been included as initial esthesia), tingling (paresthesia), itching

possibilities. What questions does one ask? (pruritus), burning, rawness, tenderness,

First, the clinician must have a reasonable and clicking/popping of temporoman-

comprehensive knowledge of the possible dibular joint (TMJ).

disease entities he or she may encounter. Textural changes: Roughness, dryness

Without this knowledge base, the appro- (xerostomia, xerophthalmia), and swelling

priate line of questioning may not be obvi- (growth, enlargement).

ous. Alternatively, the examiner who is Functional changes: Difficulty with swal-

aware of the various diseases sharing com- lowing, opening, or chewing: altered bite,

mon symptoms or physical signs can ask taste, or hearing; difficulty with speech:

appropriate questions to begin the process tooth clenching or grinding: joint sounds;

of elimination (i.e., limiting the differen- loose teeth and bleeding from mouth,

tial diagnosis). As we proceed through the gingiva, or nose.

sequential steps of the diagnostic process,

emphasis is placed on the development of a Once the chief symptom is recorded,

logical approach to interrogation. questioning helps to define the problem

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-01.indd 2 1/17/2011 3:22:30 PM

The Diagnostic Process 3

more accurately. Interrogation revolving tissue changes that the patient observes

around the chief complaint should explore or changes that may be unknown to the

the nature of the problem, the duration, patient but have been detected during

the periodicity, the location, and associa- the course of the physical examination.

tion with factors known to the patient. For Signs should be characterized in detail by

example, if a patient complains of pain, the exploring their features and history. When

examiner should explore its nature (i.e., a patient states that he or she discovered a

sharp, dull, throbbing, etc.). How long has tissue change, the clinician should attempt

the symptom been a problem? Has it per- to uncover, through questioning, the nature

sisted for a few hours, a few days, or for of the disease from the patient’s perspec-

weeks, or months? What is the periodic- tive, the duration, the location, and any

ity of the pain? Is it constant, intermittent, associated factors. For example, a patient

only at night, only at mealtime? Where is may state that while looking in the mirror

the pain located? It is localized or does it he or she discovered a white patch on the

radiate? Can it be associated with hot liq- tongue. The examiner will want to know

uids, cold liquids, spicy foods, citrus fruits, how the patient perceives the change. Is

sugar, pressure, percussion? A similar line it sore? Can you feel its presence? How

of questioning can be pursued for other long ago did you first notice it? Is that the

subjective complaints or symptoms. only place in your mouth you’ve noticed a

Signs are objective changes that can change? Do you recall biting your tongue

be observed or detected by palpation, per- or burning it?

cussion, auscultation, or analysis of labo-

ratory data. Common signs of oral and

maxillofacial disease processes include the MEDICAL AND DENTAL

following: HISTORY

The recording of the problem—be it a

Soft-tissue changes: White, red, or pig- symptom, a sign, or both—along with the

mented spots or patches; ulcerations; history of the illness should have allowed

blisters; multiple small nodules (papules); the examiner to contemplate a partial list

nodules; papillary growths; localized of suspected disease processes. At this

swellings; and diffuse swellings. point, the chief complaint is put aside until

Hard-tissue changes (Clinical): Dental other aspects of the data base are procured.

changes in number, shape, or structure; The next step in the diagnostic process

localized or diffuse osseous swellings; is to evaluate the patient’s history of ill-

and facial asymmetry. ness. The patient’s general health status is

Hard-tissue changes (Radiographic): reviewed by determining how the patient

Dental changes, radiolucent or feels. Does he or she feel weak or febrile?

radiopaque lesions, and mixed radiolu- Any significant weight loss or loss of appe-

cent/radiopaque lesions. tite? A history of past illness according to

Neuromuscular functional changes: the body’s organ systems is reviewed; the

Paralysis or flaccidness, muscle spasm or examiner knows that certain medical prob-

hypertrophy, sensory deficits, and altera- lems require dental treatment precautions.

tion in salivation. Furthermore, many systemic diseases

manifest observable oral and facial lesions.

Not all patients relate a specific symp- Habits and medications can also affect the

tom. Often, they observe a change in the tissues of the head and neck. Previous hos-

tissues. Objective signs can be noticeable pitalizations and any complications from

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-01.indd 3 1/17/2011 3:22:31 PM

4 Chapter 1

past medical treatment can have a bear- RADIOGRAPHIC

ing on the oral and maxillofacial tissues. EXAMINATION

Finally, the dental history might have some

influence with regard to the presenting When the patient’s history and physi-

problem. cal examination suggest pain of dental or

osseous origin, salivary occlusion, asym-

metry, or osseous enlargement, appropriate

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION radiographs are obtained to characterize

dental or intraosseous disease processes.

Provided the patient has no significant med- In general, periapical and panoramic films

ical problems that would militate against are used initially. The location of the sus-

proceeding with the physical examina- pected problem dictates the use of specific

tion, the examiner should begin a system- types of radiographs (Table 1.1). New tech-

atic evaluation of the tissues. In medicine, nology is emerging rapidly in radiology;

physical diagnosis involves examination of detailed tissue imaging is possible with

the organ systems. In dentistry, the primary the use of three-dimensional computerized

emphasis is examination of the head and tomography, radioisotopic scanning, xero-

neck. Usually, prior to a detailed evaluation radiography, and nuclear magnetic reso-

of these tissues, the vital signs, including nance imaging techniques. Many of these

blood pressure, pulse, respiration, and tem- techniques are costly, yet may be extremely

perature are assessed. Subsequently, physi- valuable diagnostically as well as for deter-

cal examination should include the external mining extent of disease. In most cases,

structures of the scalp, face, exposed skin, routine radiographs and tomograms are

and hands; the oral, nasal, and laryngeal obtained initially, and special radiographs

cavities; the tympanic membrane; the sali- are obtained as needed or when indicated.

vary glands and neck; the TMJ; and the Cone beam CT has become an extremely

dentition and periodontium. During the valuable tool for dental diagnostics.

physical examination, deviations from nor- The ability of the radiologist or the cli-

mal are recorded. nician to describe the radiomorphology and

Once the physical examination has list diseases known to exhibit specific pat-

been completed, the examiner should recall terns is of major importance. Radiographic

the chief complaint and focus attention on interpretation alone is rarely diagnostic.

physical changes associated with the pre-

senting signs and symptoms. Once a lesion

has been uncovered and clinically char- CLINICAL LABORATORY

acterized, the examiner should proceed TESTS

by ordering adjunctive diagnostic tests.

Many tests are available, and they should Clinical findings may indicate the need

be used discriminantly to avoid excessive for diagnostic clinical tests conducted by

cost to the patient. In general, a differen- the pathology laboratory. These tests are

tial diagnosis is established once the data used to evaluate blood chemistries, immu-

base from the history and physical exami- nologic reactivity (serology), hematologic

nation has been completed. When signs functions, urinalysis, microbiology, and

and symptoms point to a disease process genomic assays. Specific oral signs and

in bone, however, radiographs are usually symptoms may suggest a metabolic dis-

obtained prior to formulation of a differen- ease such as hyperparathyroidism whereby

tial diagnosis. testing for serum calcium, phosphate, and

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-01.indd 4 1/17/2011 3:22:31 PM

The Diagnostic Process 5

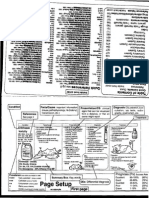

TABLE 1.1 Radiographs in Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine

Area of Investigation Radiography

Dental caries Bitewing

Infections of dental origin Periapicals

Impactions Panoramic, cone beam CT

Jaw lesions Panoramic, cone beam CT

Salivary stones (submandibular) Mandibular occlusal, sonograms, cone beam CT

Salivary stones (parotid) Panoramic, sonograms, cone beam CT

Salivary occlusion, inflammation, tumors Sialogram, radioisotope scan

Sinus lesions Water’s sinus, Caldwell sinus, sinus tomograms, cone beam CT

Other paranasal sinuses Paranasal sinus tomograms, CT scans

Facial deformities CT scans, cephalometric survey

Temporomandibular joints TMJ tomograms, arthrograms, CT scans, nuclear magnetic

resonance images, cone beam CT

Facial fractures Many different radiographs are available to visualize specific

sites, cone beam CT

Jaw and facial tumors Panoramic, CT scans, radioisotope scans, nuclear magnetic

resonance images, PET scans

Vascular jaw lesions Angiography

Dental implant sites Cone beam CT

parathormone levels support or confirm a examiner’s knowledge base is comprehen-

clinical impression; serologic testing for sive, the pieces of the puzzle usually fall

antinuclear antibodies may confirm an into place readily. Occasionally, however,

autoimmune process; a blood count in a some of these puzzles are quite complex

patient with swollen, inflamed gingiva and require more sophisticated diagnostic

may disclose leukemia; a urine sample may procedures. After all the data have been

show protein indicative of renal disease; a reviewed, collated, and correlated, the clini-

culture may be obtained to identify a sus- cian should be able to list possible disease

pected fungal infection; a gene rearrange- entities that could be responsible for the

ment study may confirm lymphoma. The findings. This list of entities represents the

tests performed in the clinical laboratory differential diagnosis.

may, therefore, be the means to a definitive

diagnosis.

Formulating a Differential

Diagnosis

Assessment of the Findings The list of entities subsumed under the

Once all the preliminary data, including designation “differential diagnosis” can be

initial radiographs, is secured, the clini- quite staggering, particularly when only

cian must return to the chief complaint the presenting signs or symptoms are taken

and physical findings. All these data must into account. To the astute clinician, the

be placed in perspective by focusing on interrogative process along with the review

the problems and correlating them with of all findings should have eliminated many

the overall findings. During this process, entities from the differential diagnosis list.

new lines of interrogation may emerge. In this regard, the “differential” has already

The problems and findings represent a been limited in scope. Perhaps only two or

mosaic that must achieve the best fit in three disease processes remain worthy of

order to arrive at a diagnosis. Provided the consideration.

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-01.indd 5 1/17/2011 3:22:31 PM

6 Chapter 1

So far, the discussion has revolved

around principles and generalities. A spe- Securing a Definitive Diagnosis

cific example may help to clarify some Once a reasonable limited differential diag-

of these general considerations. Suppose nosis is formulated, specific tests are con-

a 40-year-old woman comes to you with ducted. These tests can further limit the

a chief complaint of painful sores in her differential by excluding some diseases

mouth. This is a presenting symptom. If (i.e., the rule out process). It is more advis-

you were to develop a differential diag- able, however, to rule in probable disease

nosis including all lesions that manifest processes. In oral medicine, the most use-

mouth sores, you would probably use up an ful diagnostic tool is biopsy. In most, yet not

entire notebook. This task might be a ter- all instances, the pathologist can provide a

rific academic exercise, but the patient is definitive diagnosis based on histologic

waiting for help. At this point, you would evaluation of the diseased tissue. Some dis-

want to obtain more history. She states that eases exhibit ambiguous or nonspecific his-

they appeared 2 weeks ago, she never had tologic changes, and clinical or laboratory

anything like this before, and they are get- findings are more germane to the process of

ting worse. Despite all this, she does not inclusion or exclusion.

feel tired or feverish. Review of her medi- Another important concept is the prin-

cal history is noncontributory, meaning she ciple of “cause and effect.” Just because two

has a clean bill of health. Furthermore, she factors occur simultaneously (i.e., they are

is not taking any medication. At this point, correlated) doesn’t mean one causes the

the long list in your differential diagnosis other. For example, an ulcer may occur on

may be somewhat shortened. the tongue adjacent to a fractured tooth

You conduct the physical examination cusp. Before concluding a cause-and-effect

and find multiple oral lesions that are red, relationship, the dentist should restore the

ulcerated, and sloughing. Furthermore, you tooth to normal contour and allow 2 weeks

discover a few large intact blisters. Being to pass. If the lesion persists, the initial

a sharp clinician, you conclude that this observation ascribing an irritational caus-

patient suffers from one of the bullous disor- ative role can no longer be substantiated. A

ders. You have now considerably shortened biopsy should then be performed, and it may

the list because less than a dozen bullous reveal an early cancerous lesion. Therefore,

diseases affect the oral tissues. Also, during a cause should be sought in all cases, and if

your examination, you failed to note any found, documentation is pursued to deter-

conjunctival, nasal, or skin lesions. What mine whether or not the observation was

you have is a limited, working differential indeed causative or merely correlative.

diagnosis. Furthermore, based on her age, In most instances, a definitive diagnosis

sex, and distribution of the oral lesions, you can be secured on a clinical, histologic, radio-

can eliminate some of the entities in the logic, and/or laboratory basis. Occasionally,

bullous disease category. a final diagnosis cannot be made because all

This example, then, helps to clarify definitive tests and criteria are ambiguous.

the process of limitation of the differen- Under these circumstances, therapeutic tri-

tial diagnosis. The final step in the diag- als may be in order. Perhaps the diagnosis is

nostic phase of the approach to the patient limited to two or three possibilities; if so, the

involves devising a plan to secure a defini- most likely disease is selected and treated

tive diagnosis. accordingly. If the treatment succeeds, then

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-01.indd 6 1/17/2011 3:22:31 PM

The Diagnostic Process 7

one can usually conclude, on the basis of that has a potential for recurrence should

response to treatment, that the probable be placed on periodic recall. The length and

diagnosis was correct. periodicity are determined by the behavior

and natural history of the disease process.

Formulating a Treatment Plan Some diseases never recur, and initial ther-

apy is conclusive and complete; therefore,

Once a definitive diagnosis is made, the short-term follow-up and assessment are

most efficacious treatment must be selected. adequate. Alternatively, neoplastic diseases

Depending on the disease, the following and chronic illnesses may require frequent

management strategies are considered: (1) recall assessment and retreatment.

no treatment, (2) surgical removal, (3) phar- The diagnostic process must be thor-

macologic agents, (4) palliative treatment, ough and include history procurement,

(5) behavioral or functional treatment, and physical examination, and radiologic exam-

(6) psychiatric therapy. Referral to a medical ination when indicated. All patient find-

or dental specialist may be required. One ings are integrated to synthesize a differ-

should realize that many diseases cannot ential diagnosis. The differential diagnosis

be cured, and treatment is aimed at control is pared down with selective interrogation

and alleviation of symptoms. Some diseases and specific diagnostic procedures, such as

resolve of their own accord, some require a biopsy and clinical laboratory tests. With

single curative treatment, and others require establishment of a definitive diagnosis, a

prolonged or indefinite treatment. management plan can be devised; results of

After a management strategy has been therapy should be evaluated by follow-up

formulated and implemented, a plan for assessment, and preventive measures, when

prevention of recurrence should be devised. applicable, should be instituted.

For example, a patient with leukoplakia The remainder of this text is designed

showing microscopic evidence of premalig- to aid the clinician in the attainment of

nant change (i.e., dysplasia) may have been a definitive diagnosis; each disease is

successfully treated surgically. Failure to described so that the examiner can evaluate

eliminate important etiologic factors such efficiently the signs and symptoms to arrive

as continued alcohol and tobacco use could at a definitive diagnosis. Most chapters are

result in a recurrence of the disease in the arranged according to physical findings;

same site or in a new location. The clinician the final chapter, dealing with facial pain,

should advise the patient about these poten- being subjective, is outlined according to

tially harmful habits and help the patient to presenting symptoms. The recommended

curtail them. therapy is mentioned briefly, and the reader

The final consideration, and one of may find more detail regarding manage-

paramount importance, is patient follow-up ment by referring to the current references

and assessment. Patients with a disease listed for each disease.

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-01.indd 7 1/17/2011 3:22:31 PM

a b

Normal mucosa Hyperkeratosis

c d

Acanthosis Lymphocytic infiltration

e f

Extrinsic coating Ulcerative pseudomembrane

White Lesions

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 8 1/17/2011 3:23:32 PM

White Lesions

2

Flat Plaques, Solitary 11 Verrucous/Rippled Plaques 31

FRICTIONAL BENIGN KERATOSES 11 PROLIFERATIVE VERRUCOUS

LEUKOPLAKIA 12 LEUKOPLAKIA 31

ACTINIC CHEILITIS 14 VERRUCOUS CARCINOMA 33

SMOKELESS TOBACCO

KERATOSES 14 Lacey White Lesions 34

SANGUINARIA-INDUCED LICHEN PLANUS 34

KERATOSES 16

LICHENOID REACTIONS 36

DYSKERATOSIS CONGENITA 17

LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS 37

FANCONI’S ANEMIA 18

HIV-ASSOCIATED HAIRY

DYSPLASIA, CARCINOMA IN SITU, LEUKOPLAKIA 38

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA,

AND VERRUCOUS CARCINOMA 19

LICHEN PLANUS

Papular Lesions 40

(HYPERTROPHIC TYPE) 21 KOPLIK SPOTS OF MEASLES 40

MUCOUS PATCHES FORDYCE’S GRANULES 41

(SECONDARY SYPHILIS) 22 DENTAL LAMINA CYSTS, BOHN’S

NODULES, EPSTEIN’S PEARLS 41

Flat Plaques, Bilateral STOMATITIS NICOTINA 42

or Multifocal 23 SPECKLED LEUKOPLAKIA 43

LEUKOEDEMA 23

GENOKERATOSES 24

Pseudomembranous Lesions 44

PLAQUE-FORM LICHEN CHEMICAL BURNS 44

PLANUS 30 CANDIDIASIS (MONILIASIS, THRUSH) 45

CHEEK/TONGUE BITE VESICULO-BULLOUS-ULCERATIVE

KERATOSIS 30 DISEASES 47

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 9 1/17/2011 3:23:34 PM

White lesions of oral mucous membranes Inflammatory lesions that may pro-

appear thus because one or more of the epi- duce thickened epithelium and/or a sur-

thelial layers is thickened or an extrinsic face pseudomembrane appear white; in

or intrinsic pseudomembrane is adherent these instances, the surface coating may be

to the surface mucosa. The white lesions rubbed away with gauze. The diagnosis of

encountered in practice may be subdivided inflammatory white lesions can be secured

into groups on the basis of pathogenesis by obtaining a thorough history, including

or etiologic factors. Developmental white questions regarding use of drugs, sexual

lesions are generally bilateral. Patients habits or promiscuity, recent contact with

relate that a familial pattern exists, because persons manifesting similar illness, or con-

most of the developmental white lesions are tact with injurious chemicals.

genetically inherited (genokeratosis). This chapter illustrates and enumer-

As a gardener’s hands become cal- ates the features of white lesions in the

loused from hours of friction from the hoe, context of clinical features as outlined ear-

so may the oral epithelium become calloused lier. The differential diagnosis for a given

or thickened in response to chronic trauma. white lesion depends on obtaining a his-

Tobacco in its many forms is also consid- tory, with primary considerations of (1) a

ered a local irritant and indeed is associated familial pattern; (2) presence or absence

with carcinomatous transformation in white of a causative agent with notations on oral

lesions of the oral mucosa. The white lesions habits, particularly tobacco use; (3) pres-

associated with physical or tobacco-product ence or absence of associated skin lesions;

irritation are grouped under the heading (4) questions relating to contact with indi-

leukoplakias, as are other white lesions of viduals showing similar lesions; (5) AIDS-

undetermined origin. Because tobacco-as- risk status; (6) presence or absence of fever;

sociated and idiopathic white lesions may and (7) exploration of the nature of the

show microscopic evidence of malignancy, white patch as to tenacity to underlying

biopsy must be performed when (1) a cause structures and ease of removal by rubbing.

cannot be detected or (2) the suspected trau- Based on responses and fi ndings regard-

matic agent is eliminated yet the lesion fails ing these considerations, a ranking of

to involute or regress. Leukoplakia of the entities in the differential diagnosis may

lateral tongue may be indicative of human ensue and, ultimately, biopsy—or in cer-

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) seropositiv- tain instances serology and blood count—

ity, particularly among patients who fall must be performed to obtain a defi nitive

into AIDS-risk categories. diagnosis.

White lesions of nonhereditary dis- The white lesions encountered most

eases may coexist with skin lesions. These frequently are (1) friction, idiopathic or

keratotic dermatoses may, however, occur tobacco-associated leukoplakias, (2) lichen

as oral lesions with skin involvement. As no planus, (3) candidiasis, and (4) Fordyce’s

etiologic agent can be discerned in oral ker- granules.

atotic dermatoses, biopsy must be under- White lesions associated with a poten-

taken to confirm the diagnostic impression tially lethal outcome include (1) premalig-

when classic clinical features of these disor- nant leukoplakias, (2) hairy leukoplakia,

ders are lacking. and (3) lupus erythematosus.

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 10 1/17/2011 3:23:35 PM

White Lesions 11

MICROSCOPIC FEATURES

Flat Plaques, Solitary Frictional irritation may cause thickening

FRICTIONAL BENIGN of any layer or combination of layers of

the epithelium with hyperorthokeratosis,

KERATOSES

hyperparakeratosis, and/or acanthosis.

Figure 2-1 Depending on the degree of irritation,

Age: No predilection

the underlying submucosa may show an

Sex: No predilection inflammatory cell infiltrate, which is usu-

ally chronic.

CLINICAL FEATURES

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Frictional keratoses represent callus forma-

tion from chronic trauma with resultant White lesions arising from chronic irritation

thickening of one of the epithelial cell lay- may be diagnosed as such when a causative

ers. The white lesions are therefore associ- agent presents itself. Providing the cause can

ated with various etiologic agents, including be eliminated or reduced (e.g., leaving ill-fit-

ill-fitting dental prostheses, chronic irrita- ting dentures out of the mouth for 2 weeks,

tional habits such as cheek- or lip-biting, smoothing irritating tooth cusps, avoiding

overzealous tooth brushing, and white cal- habits), and the white lesion regresses or

luses formed from occluding on edentulous resolves; a cause-and-effect relationship can

ridges or the retromolar pads, a condition be substantiated. Failure of a white lesion

termed oral lichen simplex chronicus. The to regress subsequent to elimination of the

individual lesions may be smooth or irregu- causative agent(s) should arouse suspicion

lar in texture, and their location and con- with regard to precancerous leukoplakia,

figuration coincide with the corresponding and biopsy is then indicated. In addition,

location of the causative agent. Frictional other diseases manifesting white lesions

keratoses may also be multifocal. may coincidentally correspond to denture-

FIGURE 2-1

Frictional keratosis due to

irritation.

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 11 1/17/2011 3:23:35 PM

12 Chapter 2

bearing zones; however, diseases such as more often seen on the buccal mucosa,

lichen planus, moniliasis, or the genokera- mucobuccal fold, and oral floor. These leu-

toses are typically located in regions beyond koplakias may be smooth, ridged, rough,

the confines of a potential irritant. delineated, or diffuse. The smooth form or

planar type fails to exhibit surface irregu-

TREATMENT larity, being homogeneously white without

Elimination of the causative agent is indi- a verrucous texture, yet others may have a

cated. White lesions attributed to a chronic ridged or verrucous appearance. The term

irritant probably have a limited tendency leukoplakia is strictly clinical and has no

to undergo malignant change. Should the implications with regard to microscopy.

lesions fail to resolve after removal of the These lesions are usually benign yet may

irritant, however, a biopsy should be per- show microscopic evidence of premalig-

formed to rule out atypical cell changes that nant cellular change. Whereas leukoplakias

occur independently. as a collective group display microscopic

evidence of dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or

squamous cell carcinoma in approximately

Additional Reading 20% of the cases, evidence suggests that

the atypical cell changes are less prevalent

Axell T, Holmstrup P, Kramer Irh, Pindborg JJ, Shear M. in the smooth planar form compared with

International seminar on oral leukoplakia and associat- the verrucous appearing lesions. Leukopla-

ed lesions related to tobacco habits. Community Dent kias of the oral floor manifest the highest

Oral Epidemiol. 1984;12:146. incidence of atypical cell change; approxi-

Cawson RA. Leukoplakia and oral cancer. Proc R Soc

Med. 1969;62:610. mately 40% harbor atypical cells.

Natarajan E, Woo SB. Benign alveolar ridge keratosis

(oral lichen simplex chronicus): a distinct clinicopatho- Microscopic features

logic entity. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):151-157.

Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. A Textbook of Oral The clinical extent does not necessarily pre-

Pathology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders; dict the microscopic features. Idiopathic or

1983:92. tobacco-induced leukoplakias may merely

Waldron CA. In: Gorlin RJ and Goldman HM, eds. show hyperorthokeratosis, hyperparakera-

Thoma’s Oral Pathology. Vol 2. 6th ed. St Louis, MO:

C. V. Mosby; 1970:811.

tosis, acanthosis, or a combination. Alterna-

tively, and most important, cellular atypia,

dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or frank super-

ficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma

LEUKOPLAKIA may be encountered microscopically.

Figure 2-2

Differential diagnosis

IDIOPATHIC/SMOKED TOBACCO-

ASSOCIATED LEUKOPLAKIA Idiopathic and tobacco-associated leukopla-

kia must be differentiated from frictional

Homogeneous Leukoplakia leukoplakia on the basis of history. Lichen

Age: Middle-aged and elderly adults planus, lupus erythematosus, the genokera-

Sex: Males predominantly toses, and inflammatory white lesions must

also be eliminated from consideration on

Clinical features the bases of history and biopsy findings.

White plaques of unknown etiology or

those encountered in smokers and tobacco Treatment

chewers are a common malady that may Biopsy should be performed in all instances

occur on any oral mucosal surface yet are of idiopathic or tobacco-associated leuko-

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 12 1/17/2011 3:23:45 PM

White Lesions 13

FIGURE 2-2

Thickened, diffuse white

lesions representing idio-

pathic leukoplakia.

plakia to ascertain whether or not prema- managed by combined radiotherapy and

lignant cell changes exist. Benign cellular surgery.

features do not preclude future malignant

change in the same location or in a new site.

About 2% to 3% of benign leukoplakias may

progress to carcinoma, whereas 17.5% of all

Additional Reading

oral leukoplakias, including cases with and Bánóczy J, Csiba A. Comparative study of the clinical

picture and histopathologic structure of oral leukopla-

without dysplastic change, progress to car-

kia. Cancer. 1972;29:1230.

cinoma over a mean follow-up period of 7½ Holmstrup P, Vedtofte P, Reibel J, et al. Long-term

years. Most dysplasias fail to progress to car- treatment outcome of oral premalignant lesions. Oral

cinoma and many spontaneously regress. Oncol. 2006;42:461-474.

Recent studies have disclosed that benign Hsue SS, Wang WC, Chen CH, et al. Malignant trans-

formation in 1458 patients with potentially malig-

leukoplakias may progress to carcinoma nant oral mucosal disorders: a follow-up study based

over time in almost comparable numbers in a Taiwanese hospital. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:

to those that are dysplastic. For these rea- 25-29.

sons, patients should be subjected to peri- Mincer HH, Coleman SA, Hopkins KP. Observations on

the clinical characteristics of oral lesions showing his-

odic follow-up with rebiopsy, particularly tologic epithelial dysplasia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

when a change in the clinical character of Pathol. 1972;33:389.

a lesion evolves. Lesions with a microscopic Silverman S, Jr, Gorsky M, Lozada F. Oral leukoplakia

diagnosis of dysplasia or carcinoma in situ and malignant transformation. A follow-up study of

2157 patients. Cancer. 1984;53:563.

should be surgically stripped or removed Waldron CA, Shafer WG. Leukoplakia revisited. A clini-

in toto by standard surgery, cryosurgery, or copathologic study of 3256 oral leukoplakias. Cancer.

laser surgery. Invasive carcinoma is usually 1975;36:1386.

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 13 1/17/2011 3:23:45 PM

14 Chapter 2

ACTINIC CHEILITIS TREATMENT

Figure 2-3 A biopsy should be performed to deter-

mine whether or not dysplasia is present.

Age: Middle-aged and elderly adults A lack of premalignant cellular changes in

Sex: Males predominate actinic cheilitis does not preclude future

CLINICAL FEATURES evolvement. Protection from the sun with

solar protective cream containing p-amin-

Solar or ultraviolet light exposure may pre- obenzoic acid (PABA) is recommended.

dispose the vermilion border to keratotic Histologically, atypical change should be

change, and certain individuals whose managed by lip stripping with incontinuity

occupations or hobbies provide continu- wedge resection if a zone of superficial car-

ous exposure to sun are most prone to cinomatous invasion is coexistent.

develop actinic cheilitis. The lower lip If no foci of carcinoma exist, topical

is more prominent and, therefore, more application of 1% 5-fluorouracil cream twice

prone to actinic change than the upper. daily for 2 weeks will remove dysplastic epi-

The lesion is white and usually smooth thelium, allowing for regeneration of nor-

and diffuse. The borders may be sharply mal epithelium. Other effective treatments

delineated from uninvolved vermilion, or include 5% imiquimod cream and photody-

the transition may be gradual. Ulcerations namic therapy with methyl aminolevulinic

or focal zones of highly thickened keratin acid as the photosensitizer and red light at

plaque may indicate early carcinomatous 630 nm.

transformation.

MICROSCOPIC FEATURES Additional Reading

Solar cheilitis reflects a spectrum of micro- Bernier JL, Reynold MC. The relationship of senile elas-

scopic changes similar to leukoplakia. The tosis to actinic radiation and to squamous cell carci-

noma of the lip. Milit Med. 1955;117:209.

early limited changes are restricted to the

Castaño E, Comunión A, Arias D, et al. Photodynamic

keratin layer, which manifests thickening, therapy for actinic cheilitis. Actas Dermosifiliogr.

and the subjacent connective tissue zones, 2009;100:895-898.

which characteristically show clumping, Picascia DD, Robinson JK. Actinic cheilitis: a review of

fragmentation, and granulation of elastic etiology, differential diagnosis, and treatment. J Am

Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:255.

fibers known as solar or senile elastosis. Smith KJ, Germain M, Yeager J, Skelton H. Topical 5%

Progression to cytologic atypia, dysplasia, imiquimod for the therapy of actinic cheilitis. J Am

and frank invasive carcinoma can develop Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:497-501.

in actinic cheilitis. The earliest premalig- Warnock GR, Fuller RP, Jr, Pelleu GB, Jr. Evaluation of

5-fluorouracil in the treatment of actinic keratosis of

nant atypicality is represented by atrophy the lip. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1981;52:501.

of the spinous cell layer, fragmentation of

the basement membrane, and mild hyper-

SMOKELESS TOBACCO

chromatism and/or pleomorphism of the

basal cells. KERATOSES

Figure 2-4

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Age: No predilection

Habitual lip chewing must be differenti- Sex: No predilection

ated from actinic cheilitis. Tobacco irritants

CLINICAL FEATURES

(cigars, pipe stems, and reverse smoking)

may induce hyperkeratotic lesions of the White lesions caused by snuff and chewing

lips. tobacco usage are located under the area in

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 14 1/17/2011 3:23:53 PM

White Lesions 15

FIGURE 2-3

Actinic cheilitis of the lip.

FIGURE 2-4

Corrugated white plaques attributed to smokeless tobacco (snuff dipper’s keratosis).

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 15 1/17/2011 3:23:53 PM

16 Chapter 2

which these agents are habitually placed;

they are therefore encountered in the Additional Reading

mucobuccal fold region. The lesion is some- Brown RL, Suh JM, Scarborough JE, Wilkins SA, Jr,

what rough and may manifest an undulat- Smith RR. Snuff dipper’s intraoral cancer; clini-

ing or wrinkled surface. The white areas cal characteristics and response to therapy. Cancer.

are relatively well circumscribed and local- 1965;18:2.

Greer RO, Jr, Poulson TC. Oral tissue alterations asso-

ized to the area of snuff placement. Dur- ciated with the use of smokeless tobacco by teenag-

ing the 1980s and currently, the incidence ers. Part 1. Clinical findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

of smokeless tobacco use by teenagers has Pathol. 1983;56:275.

increased. Rodu B, Jansson C. Smokeless tobacco and oral cancer:

A review of the risks and determinants.Crit Rev Oral

Biol Med. 2004;15:252-263.

MICROSCOPIC FEATURES

Roed-Petersen B, Pindborg JJ. A study of Danish

As with other forms of tobacco-induced snuff-induced oral leukoplakia. J Oral Pathol Med.

leukokeratosis, snuff keratosis may show 1973;2:301.

Rosenfeld L, Callaway J. Snuff dipper’s cancer. Am J

a thickening of one of the epithelial lay- Surg. 1963;106:840.

ers (i.e., hyperorthokeratosis, hyperparak-

eratosis, acanthosis), with a tendency for

“chevron”-shaped projections in the corni- SANGUINARIA-INDUCED

fied layer. Cytologic atypia is rarely seen, KERATOSES

and progression to invasive carcinoma is

Figure 2-5

rare among moist snuff users yet is signifi-

cantly more carcinogenic when dry snuff Age: no predilection

is used or when snuff is mixed with slaked Sex: no predilection

lime, a common additive in India and the

Middle East. CLINICAL FEATURES

Sanguinaria (blood root) is a chemical that

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS has been shown to be antimicrobial and was

A white lesion in the mucobuccal fold may placed in dentifrice as well as in a mouth

represent frictional keratosis or leukoplakia rinse preparation to reduce microbial

related to tobacco products. A thorough his- plaque on tooth biofilms. A spurious find

tory will indicate whether or not the lesion among chronic and heavy users of these

is smokeless tobacco related. The “ebbing Sanguinaria products was the appearance

tide” effect on the white surface implicates of leukoplakias, particularly on the maxil-

snuff usage. lary anterior gingival and mucobuccal fold.

This localization has been attributed to the

TREATMENT physiology of mouth rinsing whereby the

All smokeless tobacco-associated white rinse is forcefully extended into the labial

lesions must be examined microscopi- compartment of pursed lips.

cally to rule out premalignancy. If atypi-

MICROSCOPIC FEATURES

cal cytologic changes are present in high

risk populations, complete excision is rec- Most biopsies from Sanguinaria-induced

ommended. Absence of cellular prema- leukoplakias exhibit benign keratosis with-

lignant changes does not preclude future out dysplasia. DNA ploidy studies, how-

evolution to cancer; therefore, the habit ever, have disclosed abnormal DNA content

should be curtailed. Tobacco-specific nit- in some of these lesions and, therefore, both

rosamines are thought to be the chief car- rinse and dentifrice have been withdrawn

cinogens in chewing tobacco and snuff. from the market.

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 16 1/17/2011 3:24:20 PM

White Lesions 17

FIGURE 2-5

Sanguinaria-induced keratoses of the anterior maxillary gingival and vestibule.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS complex (DKC1, TERC, TERT, NOP10,

Sanguinaria leukoplakia may simulate idio- NHP2) or shelterin (TINF2). The syndrome

pathic leukoplakias and plaque-form lichen is characterized by atrophic nail changes,

planus. telangiectatic pigmented reticular lesions of

skin, pancytopenia, and oral white lesions

TREATMENT associated with dorsal tongue depapillation

and atrophy. Premature aging is also fea-

Discontinuing the use of the product is tured. Forty percent of oral lesions progress

required, and many months may elapse to squamous cell carcinoma before the age

before the lesions resolve. of 50.

Additional Reading MICROSCOPIC FEATURES

A nonspecific thickening of the parakeratin

Allen CL, Loudon J, Mascarenhas AK. Sanguinaria- and spinous cell layer is seen. Dysplastic

related leukoplakia: epidemiologic and clinicopatho-

logic features of a recently described entity. Gen Dent. changes, absent in pachyonychia, evolve

2001;49:608-614. and progress to squamous cell carcinoma

Eversole LR, Eversole GM, Kopcik J. Sanguinaria- in dyskeratosis congenita.

associated oral leukoplakia: comparison with other

benign and dysplastic leukoplakic lesions. Oral Surg

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:455-

464. The mucosal white lesions and constellation

of other clinical findings of dyskeratosis con-

genita may be confused with pachyonychia

DYSKERATOSIS CONGENITA congenita. Fanconi’s anemia is a significant

Figure 2-6 syndrome to consider in the differential

diagnosis since it presents with bone mar-

Age: Childhood onset

row suppression and oral white lesions that

Sex: No predilection

can progress to carcinoma. Other keratoses

CLINICAL FEATURES such as white sponge nevus, HBID, and

Dyskeratosis congenita (Zinsser-Engman- lichen planus should also be considered.

Cole syndrome) is inherited as either an

autosomal recessive, X-linked or autosomal TREATMENT

dominant disorder with telomere shorten- Close clinical follow-up of oral lesions is

ing mediated by mutations in six genes that mandatory since malignant transformation

encode either components of the telomerase will occur later in life.

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 17 1/17/2011 3:24:20 PM

18 Chapter 2

FIGURE 2-6

Dyskeratosis congenita. White lesions that progress to carcinoma.

deformed thumbs or agenesis. Pancytopenia

Additional Reading occurs with thrombocytopenia and neutro-

Alter BP, Giri N, Savage SA, Rosenberg PS. Cancer in penia. These events occur due to mutations

dyskeratosis congenita. Blood. 2009;113:6549-6557. in a group of core protein complexes (the FA

Armanios M. Syndromes of telomere shortening. Ann genes) whose function involves DNA repair

Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:45-61. and antioxidant synthesis. These patients

Kirwan M, Dokal I. Dyskeratosis congenita, stem cells

and telomeres. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792(4D): may develop leukoplakias located on the

371-379. tongue or floor of the mouth that can later

Walne AJ, Dokal I. Advances in the understanding of transform to carcinoma.

dyskeratosis congenita. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:

164-172.

MICROSCOPIC FEATURES

The keratotic lesions in Fanconi’s anemia

FANCONI’S ANEMIA exhibit the same histology as those found

Figure 2-7 in idiopathic leukoplakias (i.e., benign kera-

tosis, dysplasia, carcinoma).

Age: Childhood onset

Sex: No predilection DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

CLINICAL FEATURES The white lesions are similar to other leuko-

Fanconi’s anemia is an autosomal recessive plakias being flat plaques. The unique con-

genetic disorder involving as many as 13 stellation of syndromic characteristics usu-

genes of which mutations occur. If both par- ally allow for a straightforward diagnosis.

ents are carriers, there is a 25% risk of having

an affected child. Affected children develop TREATMENT

bone marrow suppression with erythrocyte The pancytopenia and leukemia can be

macrocytosis, and many will progress to managed by chemotherapy with greatest

acute myelogenous leukemia. Digital anom- response being seen after bone marrow

alies are characterized by anatomically transplantation. Importantly, many head

PMPH_Eversole_Chapter-02.indd 18 1/17/2011 3:24:24 PM

White Lesions 19

DYSPLASIA, CARCINOMA

IN SITU, SQUAMOUS

CELL CARCINOMA, AND

VERRUCOUS CARCINOMA

Figure 2-8

Age: Elderly adults

Sex: Males predominate

CLINICAL FEATURES

Early cancerous change within the oral epi-

thelium may initially manifest as a white

lesion or may arise in a preexisting leuko-

plakic area. Depending on the extent of the

tumor, the white lesion may be relatively

macular or plaque-like or, in larger lesions,

associated with tumefaction and indura-

tion. Whereas oral cancer is generally local-

ized, it may, on occasion, be multifocal with

numerous isolated separate white lesions

manifesting microscopic evidence of neo-

plastic transformation. Location is highly

significant when considering the possibility

of malignancy; although malignant change

may be seen on any surface, the most com-

mon locations are oral floor, alveolar ridge

FIGURE 2-7 and vestibule, and lateral posterior tongue.

Fanconi’s anemia. Thumb anomaly, oral carcinoma. The most important contributing etio-

logic factors regarding carcinogenesis of

and neck cancers have evolved in Fanconi oral epithelium are use of tobacco and a high

patients after marrow transplantation. intake of alcohol. Patients with untreated

syphilis and the Plummer-Vinson syndrome

are also prone to develop oral or oropharyn-

Additional Reading geal cancer. Recent research indicates that

a subpopulation of patients have tumors