Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vrij & Turgeon. (2018) - Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses

Vrij & Turgeon. (2018) - Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses

Uploaded by

Andrea Guerrero ZapataCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Application of Psychology in The Legal SystemDocument18 pagesApplication of Psychology in The Legal SystemOpsOlavario100% (2)

- Nourhan Habib - Forensic Psychology - Curtis FlowersDocument14 pagesNourhan Habib - Forensic Psychology - Curtis FlowersSima Habib100% (1)

- Offender ProfillingDocument192 pagesOffender Profillingcriminalistacris100% (3)

- Associate CalassDocument151 pagesAssociate CalassMuhammad Naveed AnjumNo ratings yet

- Assignment Topic 3 Cá NhânDocument9 pagesAssignment Topic 3 Cá NhânTrường Tiểu học Phú Thịnh Hưng YênNo ratings yet

- ESRB Response To Senator HassanDocument4 pagesESRB Response To Senator HassanPolygondotcomNo ratings yet

- Networked Knowledge Psychological Issues Homepage DR Robert N MolesDocument28 pagesNetworked Knowledge Psychological Issues Homepage DR Robert N MolesSamuel BallouNo ratings yet

- Body Language and Veracity - Lord LeggattDocument21 pagesBody Language and Veracity - Lord LeggattRajah BalajiNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document5 pagesUnit 3ShivaniNo ratings yet

- The Trial Process, Demeanor Evidence and Admissibility 1Document15 pagesThe Trial Process, Demeanor Evidence and Admissibility 1priyanshuNo ratings yet

- John E. Reid and Associates, Inc.: Clarifying Misrepresentations About Law Enforcement Interrogation TechniquesDocument36 pagesJohn E. Reid and Associates, Inc.: Clarifying Misrepresentations About Law Enforcement Interrogation TechniquesCHUKS BRENDANNo ratings yet

- Clarifying Misrepresntations of Law Enforcement Interrgoation Techniques Feb 2022 2022 03-18-140724 NabuDocument36 pagesClarifying Misrepresntations of Law Enforcement Interrgoation Techniques Feb 2022 2022 03-18-140724 NabugrandamianbNo ratings yet

- Cornell Law Review ArticleDocument30 pagesCornell Law Review Articlepalmite9No ratings yet

- Chapter - 1: Circumstantial Evidence Is Evidence That Relies On An Inference To Connect It To ADocument17 pagesChapter - 1: Circumstantial Evidence Is Evidence That Relies On An Inference To Connect It To ARupali RamtekeNo ratings yet

- Re Evaluating The Credibility of Eyewitness Testimony The Misinformation Effect and The Overcritical JurorDocument25 pagesRe Evaluating The Credibility of Eyewitness Testimony The Misinformation Effect and The Overcritical Juroralysa.leemynnNo ratings yet

- Evidence Law ProjectDocument10 pagesEvidence Law ProjectTulika GuptaNo ratings yet

- Methods of InterrogationDocument16 pagesMethods of InterrogationJoshua ReyesNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper # 1-"How To Spot A Liar", by Pamela Meyer, TED TalksDocument7 pagesReaction Paper # 1-"How To Spot A Liar", by Pamela Meyer, TED TalksRoel DagdagNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument7 pagesChapter IAnna Marie BorciNo ratings yet

- Bloom 3Document118 pagesBloom 3jbsayadNo ratings yet

- ProjDocument19 pagesProjAmar SinghNo ratings yet

- Evidence 7TH SemDocument18 pagesEvidence 7TH SemANANYA AGGARWALNo ratings yet

- Psycho ProjectDocument19 pagesPsycho ProjectKashish ChhabraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15 Social Psychology in CourtDocument31 pagesChapter 15 Social Psychology in CourtReyalyn AntonioNo ratings yet

- Principles of Evidence: Jon SmibertDocument240 pagesPrinciples of Evidence: Jon SmibertArbab Ihtishamul Haq KhalilNo ratings yet

- Eyewitness Testimony Is Not Always AccurateDocument7 pagesEyewitness Testimony Is Not Always AccuratejaimieNo ratings yet

- NAME: Sushmitha.S REG NO: 21BLA1112 SUBJECT: Law of Evidence SUBMITTED TO: Prof. Arjun DATE: 20/07/23Document9 pagesNAME: Sushmitha.S REG NO: 21BLA1112 SUBJECT: Law of Evidence SUBMITTED TO: Prof. Arjun DATE: 20/07/23Sushmitha SelvanathanNo ratings yet

- CDI 313 Module 2Document28 pagesCDI 313 Module 2Anna Rica SicangNo ratings yet

- De-Ritualising The Criminal TrialDocument39 pagesDe-Ritualising The Criminal TrialDavid HarveyNo ratings yet

- Eye Witness Memory: Convictions Were Subsequently Overturned With DNA Evidence, See The Innocence Project WebsiteDocument2 pagesEye Witness Memory: Convictions Were Subsequently Overturned With DNA Evidence, See The Innocence Project WebsiteashvinNo ratings yet

- Circumstantial EvidenceDocument15 pagesCircumstantial Evidencegauravsingh0110No ratings yet

- Monika ReportDocument110 pagesMonika ReportMohit PacharNo ratings yet

- John E. Reid and Associates, IncDocument14 pagesJohn E. Reid and Associates, IncAngelika BandiwanNo ratings yet

- Bite MarksDocument54 pagesBite Marksrobsonconlaw100% (1)

- Beyond PDFDocument7 pagesBeyond PDFLuis gomezNo ratings yet

- Eyewitness EvidenceDocument31 pagesEyewitness Evidencea_gonzalez676No ratings yet

- Circumstantial EvidenceDocument15 pagesCircumstantial EvidenceJugheadNo ratings yet

- Report Wrongful ConvictionDocument16 pagesReport Wrongful ConvictionLorene bby100% (1)

- Can Children Provide Reliable Eyewitness Testimony 01Document2 pagesCan Children Provide Reliable Eyewitness Testimony 01Sam HoqNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document4 pagesModule 2GULTIANO, Ricardo Jr C.No ratings yet

- Witness Interviewing and Suspect Interrogation Nyanza 22-23 Feb 2021 Class BDocument137 pagesWitness Interviewing and Suspect Interrogation Nyanza 22-23 Feb 2021 Class BGabriel Mganga100% (1)

- Lying To A SuspectDocument2 pagesLying To A SuspectAdrian IcaNo ratings yet

- Hearsay Evidence and Its General ExceptionsDocument2 pagesHearsay Evidence and Its General ExceptionsAabir ChattarajNo ratings yet

- American Justice in the Age of Innocence: Understanding the Causes of Wrongful Convictions and How to Prevent ThemFrom EverandAmerican Justice in the Age of Innocence: Understanding the Causes of Wrongful Convictions and How to Prevent ThemNo ratings yet

- JYSONDocument5 pagesJYSONLhiereen AlimatoNo ratings yet

- Procedural Fairness, The Criminal Trial and Forensic Science and MedicineDocument36 pagesProcedural Fairness, The Criminal Trial and Forensic Science and MedicineCandy ChungNo ratings yet

- Newring and OdonohueDocument27 pagesNewring and Odonohuegabrielolteanu101910No ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia: A Project OnDocument18 pagesJamia Millia Islamia: A Project OnSandeep ChawdaNo ratings yet

- Dna: Evidentiary Value of Dna TestingDocument6 pagesDna: Evidentiary Value of Dna TestingAnkit NandeNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Exercise (4.1-4.4)Document8 pagesUnit 3 Exercise (4.1-4.4)xTruthNo ratings yet

- ForensicDocument23 pagesForensicManjot Singh RaiNo ratings yet

- Inglés CriminológicoDocument7 pagesInglés CriminológicoGisela CNo ratings yet

- The Standard of Proof in Criminal Proceedings: The Threshold To Prove Guilt Under Ethiopian LawDocument33 pagesThe Standard of Proof in Criminal Proceedings: The Threshold To Prove Guilt Under Ethiopian LawHenok TeferiNo ratings yet

- Face-Coverings, Demeanour Evidence and The Right To A Fair Trial Lessons From The USA and CanadaDocument19 pagesFace-Coverings, Demeanour Evidence and The Right To A Fair Trial Lessons From The USA and CanadaKen MutumaNo ratings yet

- Trial ProceduresDocument6 pagesTrial ProceduresChristopher LaneNo ratings yet

- The Multiple Dimensions of Tunnel Vision - Findley e ScottDocument108 pagesThe Multiple Dimensions of Tunnel Vision - Findley e ScottPedro Ivo De Moura TellesNo ratings yet

- Expert Evidence Detailed PDFDocument77 pagesExpert Evidence Detailed PDFVarunPratapMehtaNo ratings yet

- Polygraphy Look Judicail Vala PDFDocument47 pagesPolygraphy Look Judicail Vala PDFishmeet kaurNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Forensic Science in The United States: A Path ForwardDocument12 pagesStrengthening Forensic Science in The United States: A Path Forwardchrisr310No ratings yet

- Cases in EvidenceDocument237 pagesCases in EvidenceMary Grace Dionisio-RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Victimless CrimeDocument65 pagesDissertation Victimless CrimeBenjamin SalmonNo ratings yet

- Contextual Bias in Verbal Credibility AssessmentDocument13 pagesContextual Bias in Verbal Credibility AssessmentAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Rape Victim Assessment: Findings by Psychiatrists and Psychologists at Weskoppies HospitalDocument5 pagesRape Victim Assessment: Findings by Psychiatrists and Psychologists at Weskoppies HospitalAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Hamlin Et Al. (2018) - The Dimensions of Deception Detection Self Reported Deception Cue Use Is Underpinned by Two Broad FactorsDocument9 pagesHamlin Et Al. (2018) - The Dimensions of Deception Detection Self Reported Deception Cue Use Is Underpinned by Two Broad FactorsAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisDocument14 pagesPerceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Deprived of Human Rights: Disability & SocietyDocument7 pagesDeprived of Human Rights: Disability & SocietyAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Australian Clinical Consensus Guideline: The Diagnosis and Acute Management of Childhood StrokeDocument13 pagesAustralian Clinical Consensus Guideline: The Diagnosis and Acute Management of Childhood StrokeAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Denault Et Al. (2019) - The Detection of Deception During TrialsDocument9 pagesDenault Et Al. (2019) - The Detection of Deception During TrialsAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Science and Justice: Samuel J. Leistedt, Paul LinkowskiDocument4 pagesScience and Justice: Samuel J. Leistedt, Paul LinkowskiAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Wright & Wheatcroft. (2017) - Police Officers Beliefs About, and Use Of, Cues To DeceptionDocument14 pagesWright & Wheatcroft. (2017) - Police Officers Beliefs About, and Use Of, Cues To DeceptionAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Dunbar Et Al. (2017) - The Viability of Using Rapid Judgments As A Method of Deception DetectionDocument17 pagesDunbar Et Al. (2017) - The Viability of Using Rapid Judgments As A Method of Deception DetectionAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Nahari Et Al. (2019) - Languaje of Lies Urgent Issues and Prospects in Verbal Lie Detection ResearchDocument24 pagesNahari Et Al. (2019) - Languaje of Lies Urgent Issues and Prospects in Verbal Lie Detection ResearchAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Ramos-Yeo vs. Chua DigestDocument4 pagesRamos-Yeo vs. Chua DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- S4HANA For Consumer ProductsDocument18 pagesS4HANA For Consumer ProductsSandro Luna BazoNo ratings yet

- Securities and Exchange Commission vs. Picop Resources Inc.Document2 pagesSecurities and Exchange Commission vs. Picop Resources Inc.Arianne AstilleroNo ratings yet

- Barakah Sources Time Management PDFDocument13 pagesBarakah Sources Time Management PDFFadimatou100% (3)

- 96 Kuli Maratha Surname List Download PDFDocument3 pages96 Kuli Maratha Surname List Download PDFsatyen Turki0% (1)

- Poll Crosstabs - EconomyDocument73 pagesPoll Crosstabs - EconomyLas Vegas Review-JournalNo ratings yet

- Service MarketingDocument20 pagesService Marketingankit_will100% (4)

- The Gender of The GiftDocument3 pagesThe Gender of The GiftMarcia Sandoval EsparzaNo ratings yet

- Phed213 PrelimDocument1 pagePhed213 PrelimKaye OrtegaNo ratings yet

- GluttonyDocument2 pagesGluttonyFrezel BasiloniaNo ratings yet

- Sonnet Is A 14 Lines Poem Written Iambic PentameterDocument2 pagesSonnet Is A 14 Lines Poem Written Iambic PentameterS ShreeNo ratings yet

- Informant Policies & Practices Evaluation Committee ReportDocument47 pagesInformant Policies & Practices Evaluation Committee ReportLisa Bartley100% (1)

- Sol Gen Vs MMADocument2 pagesSol Gen Vs MMAJude ChicanoNo ratings yet

- Brochure - 6th Annual Treasury Management India Summit 2022Document13 pagesBrochure - 6th Annual Treasury Management India Summit 2022Finogent AdvisoryNo ratings yet

- PUNJAB POLICE Test 78Document9 pagesPUNJAB POLICE Test 78Jan AlamNo ratings yet

- Law of ContractDocument85 pagesLaw of ContractDebbie PhiriNo ratings yet

- Balbheemloan Sanction LetterDocument6 pagesBalbheemloan Sanction LetterVenkatesh DoodamNo ratings yet

- Dome Tank Eng PDFDocument2 pagesDome Tank Eng PDFDustin BooneNo ratings yet

- Dallas Business Journal 20150102 - SiDocument28 pagesDallas Business Journal 20150102 - Sisarah123No ratings yet

- MBA Class of 2024 Semester-1 NCP-1 (Online Test-1) Schedule (Exams Will Be Held in IT-LABS)Document1 pageMBA Class of 2024 Semester-1 NCP-1 (Online Test-1) Schedule (Exams Will Be Held in IT-LABS)XyzNo ratings yet

- Danh Vo Paris Press ReleaseDocument18 pagesDanh Vo Paris Press ReleaseTeddy4321No ratings yet

- 2281 s13 QP 21Document4 pages2281 s13 QP 21IslamAltawanayNo ratings yet

- Communion Songs For Advent SeasonDocument1 pageCommunion Songs For Advent Seasonbinatero nanetteNo ratings yet

- SafetyDocument3 pagesSafetymseroplanoNo ratings yet

- Usurf and VPNDocument11 pagesUsurf and VPNvan_laoNo ratings yet

- Betel Chewing in The PhilippinesDocument1 pageBetel Chewing in The PhilippinesMariz QuilnatNo ratings yet

- Mysticism in Shaivism and Christianity PDFDocument386 pagesMysticism in Shaivism and Christianity PDFproklos100% (2)

Vrij & Turgeon. (2018) - Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses

Vrij & Turgeon. (2018) - Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses

Uploaded by

Andrea Guerrero ZapataOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vrij & Turgeon. (2018) - Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses

Vrij & Turgeon. (2018) - Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses

Uploaded by

Andrea Guerrero ZapataCopyright:

Available Formats

J.

Tort Law 2018; 11(2): 231–244

Aldert Vrij* and Jeannine Turgeon

Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses – are We

Instructing Jurors on Invalid Factors?

https://doi.org/10.1515/jtl-2018-0013

Published online October 9, 2018

1 Introduction

Co-author Aldert Vrij, Ph.D., an internationally respected expert on evaluating

credibility and the European Consortium of Psychological Research on Deception

Detection’s contact person, presented an educational lecture program concerning

the fallacy of considering nonverbal behavior to evaluate credibility at the 2016

Pennsylvania Conference of State Trial Judges. Many of the judges listening to Dr

Vrij, wondered - why then, do judges consistently instruct jurors to consider

demeanor and other nonverbal behaviors to evaluate witnesses’ credibility? Why

do we ignore the overwhelming scientific evidence and continue to give jury

instructions contrary to the overwhelming consensus that witness demeanor is

not a basis to determine the accuracy or truthfulness of their testimony?

Many years ago, co-author Jeannine Turgeon attended United States

Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s lecture “Trial by Jury–In Need

of Repair” at The Chautauqua Institute. Justice O’Connor criticized various

aspects of our current jury system and offered suggestions for its improvement.

She opined that “[j]ust because something has ‘always been done’ a particular

way does not mean that is the best way to do it. If common sense tells us to

change something, we should change it.”1

1 Justice O’Connor inspired co-author Turgeon to commence revising Pennsylvania’s Supreme

Court Suggested Standard Civil Jury Instructions in “Plain English,” seek changes to the rules

permitting jurors to take notes, to recommend judges instruct jurors on the law at the beginning

Jeannine Turgeon, currently serves as Co-Chair of the Civil Jury Instruction Subcommittee of the

Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. The Honorable Jeannine Turgeon http://www.dauphincounty.

org/government/court_departments/turgeon_bio.php.

*Corresponding author: Aldert Vrij, Psychology Department, University of Portsmouth, King

Henry Building, King Henry 1 Street, PO1 2DY, Portsmouth, Hants, UK,

E-mail: aldert.vrij@port.ac.uk

Jeannine Turgeon, Dauphin County Court of Common Pleas, Pennsylvania, USA,

E-mail: jturgeon@dauphinc.or

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

232 A. Vrij and J. Turgeon

Today therefore, it is not “common sense” that tells us that something we

have always done should change, but rather that “scientific proof” tells us that

something - this standard jury instruction - should change. Judges provide jurors

in both civil and criminal cases various factors they should consider in deciding

the truthfulness and credibility of each witness’s testimony. As we have for the

past century or more, judges continue to utilize standard jury instructions

advising jurors to consider the witness’s demeanor and other nonverbal beha-

viors in evaluating witness credibility.

1.1 Existing jury instructions on nonverbal behavior

and a proposed replacement

Pennsylvania’s criminal and civil jury instructions include the following “non-

verbal behavior” factor for jurors to consider when evaluating witness

credibility:

How did the witness look, act, and speak while testifying?2

Most states use similar instructions directing jurors to consider “nonverbal

behavior factors” when evaluating credibility.3 An instruction from another

state advises:

In determining whether to believe any witness you should use the same tests of truthful-

ness which you apply in your everyday lives … including the manner and appearance of

the witness.4

Courts have been including this “nonverbal behavior” factor in jury instructions

most likely because it made “common sense.” However, jury instructions

informing jurors they should or must consider a witness’s demeanor are not

supported by the current scientific research. In fact, the studies establish that

rather than being a valid basis, nonverbal cues have little or nothing to do

as well as at the end of trial and to write a law review article discussing these necessary changes

to improve our jury system. Improving Pennsylvania’s Justice System Through Jury System

Innovations, Jeannine Turgeon and Elizabeth A. Francis, 18 WIDENER L.J. 419 (2009).

2 Pa. Suggested Std. Jury Instruction (Crim.) 4.17(1) (d) “Credibility of Witnesses, General” (3rd

Ed. 2016) and Pa. Suggested Std. Jury Instruction (Civil) 4.20(d”) Believability of Witnesses

Generally” (4th Ed., 2017 Supp.). See Appendix A for the complete Pennsylvania jury instruc-

tions on witness credibility.

3 See Appendix A.

4 North Carolina Pattern Jury Instruction (N.C.P.I.) Civil 101.15 (1994).

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses 233

with a witness’s truthfulness or credibility, as fully discussed below by co-

author Vrij.

Co-author Turgeon’s nearly three (3) decades as a trial judge have taught

her that in nearly every civil and criminal jury trial, jurors based their verdict

upon their credibility determinations. Current peer reviewed cognitive psycho-

logical studies consistently show that most courts’ standard jury instructions

focusing on witness demeanor are simply flawed and wrong, based upon myth

rather than evidence. Now, without further delay, the legal community must

revise instructions that direct jurors to evaluate a witness’s nonverbal behavior

without any guidance as to how to do so. Instead, we should craft new

instructions on this issue, reflecting current knowledge, in order to more

adequately explain to jurors that nonverbal behavior is unrelated to a witness’s

truthfulness or credibility. The following proposed jury instruction would

accomplish this end:

When considering whether to believe a witness, many people think that how the witness

behaves reveals whether he or she is being deceptive or truthful. Research shows, how-

ever, that most people, including experts, are not very good at correctly deciding whether a

witness is truthful based upon how the witness looks or acts, as opposed to what he or she

says. In fact, research shows little difference between the demeanor of deceptive and

truthful people.

Keep this in mind when considering non-verbal behavior by a witness; that is,

such behavior is an unreliable indicator of deception or truthfulness. The types

of nonverbal factors you may encounter include a witness who averts his or her

gaze (or looks others in the eye), shifts in his or her seat (or remains still),

appears nervous or anxious (or calm), and speaks quickly (or slowly). You

should IGNORE these kinds of factors as they are UNRELIABLE indicators of

deception (or truthfulness).

2 Nonverbal behavior and deceit

Aldert Vrij

Throughout history, most people assumed that lying is accompanied by

specific nonverbal behaviors. The underlying assumption was that the fear of

being detected was an essential element of deception.5 A Hindu writing from

900 B. C. mentioned that liars rub the great toe along the ground and shiver and

5 Trovillo, P. V. (1939a). A history of lie detection, I. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology,

29, 848–881.

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

234 A. Vrij and J. Turgeon

that they rub the roots of their hair with their fingers.6 Münsterberg7 described

the utility of observing posture, eye movements, and knee jerks for lie detection

purposes.8 The well-known Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud, father of the

psychoanalysis but not a deception researcher, also expressed his view about

the topic “He who has eyes to see and ears to hear may convince himself that no

mortal can keep a secret. If his lips are silent, he chatters with his finger-tips;

betrayal oozes out of him at every pore.”9

The belief that nonverbal behavior is revealing about deception is still

widespread. In the Netherlands and United Kingdom, 75 % of the police officers

who took part in a survey believed that liars ‘look away and make grooming

gestures.10 A worldwide survey amongst laypersons carried out in 58 different

countries found that 64 % thought that liars look away and that 25 % thought

that liars display an increase in movements.11 Gaze aversion was the most

frequently mentioned belief in 51 out of 58 countries. It showed the lowest

prevalence in the United Arab Emirates, where it still was mentioned by 20 %

of the participants, making it the eighth strongest belief in that country.

There are numerous articles in popular magazines expressing the idea

that nonverbal behavior is revealing about deception, so does the popular TV

series ‘Lie to Me’ where the lead character Dr Cal Lightman and his collea-

gues solve crimes by interpreting facial micro-expressions of emotion and

involuntary behaviors. There are many books conveying the idea that non-

verbal behaviors are revealing of deception including (e. g., Lie spotting12 and

Spy the Lie13 and (American) police manuals typically pay considerably more

6 Trovillo, P. V. (1939a). A history of lie detection, I. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology,

29, 848–881.

7 Münsterberg, H. (1908). On the witness stand: Essays on psychology and crime. New York:

Doubleday.

8 Trovillo, P. V. (1939b). A history of lie detection, II. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology,

30, 104–119.

9 Freud, S. (1959). Collected papers. New York: Basic Books. (Quote appears on page 94).

10 Vrij, A., & Semin, G. R. (1996). Lie experts’ beliefs about nonverbal indicators of deception.

Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 20, 65–80. Doi: 10.1007/ BF02248715; Mann, S., Vrij, A., & Bull,

R. (2004). Detecting true lies: Police officers’ ability to detect deceit. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 89, 137–149. Doi: 10.1037/0021–9010.89.1.137

11 The Global Deception Team (2006). A world of lies. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37,

60–74. Doi: 10.1177/0022022105282295

12 Meyer, P. (2010). Lie spotting: Proven techniques to detect deception. St Martin’s Press, New

York.

13 Houston, P., Floyd, M., & Carnicero, S. (2012). Spy the lie. St Martin’s Press, New York.

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses 235

attention to nonverbal cues to deceit than to verbal cues (see Vrij and

Granhag14 for an overview of such manuals). Nonverbal lie detection tools

such as the Behavior Analysis Interview15 and Ekman’s16 approach of obser-

ving facial expressions and involuntary body language were frequently

taught to practitioners.

2.1 Research into the relationship between nonverbal

behavior and deceit

Research findings shed a pessimistic light on the relationship between nonver-

bal behavior and deception. In recent years, meta-analyses -articles summariz-

ing the published research studies in a certain area- have concluded that

nonverbal cues to deceit are faint and unreliable.17 For example, DePaulo

et al.’s18 meta-analysis included 116 deception studies. Different deception stu-

dies examined various nonverbal cues including 32 nonverbal cues in six or

more deception studies. Of these 32 cues, six (19 %) showed a real difference

between truth tellers and liars, albeit barely perceptible. In fact, the difference

between truth tellers and liars for these six cues was, on average, the equivalent

of the difference in height between 15- and 16-year-old girls. Who could argue

that determining whether a girl is 15 or 16 years old solely based on her height is

a reliable and sensible thing to do?

14 Vrij, A., & Granhag, P. A. (2007). Interviewing to detect deception. In S. A. Christianson

(Ed.), Offenders’ memories of violent crimes (pp. 279–304). Chichester, England: John Wiley &

Sons, Ltd.

15 Horvath, F., Blair, J P., & Buckley, J. P. (2008). The Behavioral Analysis Interview: Clarifying

the practice, theory and understanding of its use and effectiveness. International Journal of

Police Science and Management, 10, 101–118.; Horvath, F., Jayne, B., & Buckley, J. (1994).

Differentiation of truthful and deceptive criminal suspects in behavioral analysis interviews.

Journal of Forensic Sciences, 39, 793–807.

16 Ekman, P. (1985). Telling lies: Clues to deceit in the marketplace, politics and marriage. New

York: W. W. Norton. (Reprinted in 1992, 2001 and 2009).

17 DePaulo, B. M., Lindsay, J. L., Malone, B. E., Muhlenbruck, L., Charlton, K., & Cooper, H.

(2003). Cues to deception. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 74–118. Doi: 10.1037/0033–2909.129.1.74;

Sporer, S. L., & Schwandt, B. (2007). Moderators of nonverbal indicators of deception: A meta-

analytic synthesis. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 13, 1–34 Doi:10.1037/1076–8971.13.1.1;

Vrij, A., Hartwig, M., & Granhag, P. A. (2018). Reading lies: Nonverbal communication and

deception. Annual Review of Psychology. Doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010418–103,135

18 DePaulo, B. M., Lindsay, J. L., Malone, B. E., Muhlenbruck, L., Charlton, K., & Cooper, H.

(2003). Cues to deception. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 74–118. Doi: 10.1037/0033–2909.129.1.74

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

236 A. Vrij and J. Turgeon

Research examining people’s ability to detect deceit by observing other

people’s behavior shows an equally bleak picture. Bond and DePaulo19 pub-

lished a meta-analysis about people’s ability to detect truth and lies. This meta-

analysis, which included the veracity judgements made by almost 25,000 obser-

vers, revealed an average accuracy rate of 54 % in correctly classifying truth

tellers and liars, barely above the chance level of 50 %. In theory, there are two

possible explanations for such low accuracy rates. People perform poorly

because (i) there is little difference between the truth tellers and liars they

observe which makes the task very difficult, or (ii) they look for the wrong

cues and fail to spot the differences that actually exist. In their meta-analysis,

Hartwig and Bond20 examined these two possibilities and found support for the

first explanation: People perform poorly because the differences between truth

tellers and liars are too small to make the task achievable. This also explains

why training people to detect lies - by informing them about “diagnostic non-

verbal cues to deceit”- have hardly any effect.21

Such research findings are criticized by professionals who claim that they

are based on laboratory studies where the stakes (the negative consequences of

getting caught or positive consequences of getting away with the lie) are lower

than in the real-life situations professionals are interested in. They also claim

that lies are easier to detect in high-stakes situations than in low-stakes situa-

tions. Research does not support this latter claim. In a meta-analysis, it was

examined whether differences between truth tellers and liars differed between

low- and high-stakes situations.22 This was not the case. When the stakes are

higher, liars may be more nervous and may be more likely to display signs of

anxiety (which then can be interpreted as signs of deceit) but the same is true for

truth tellers. They also become more nervous when the stakes increase and are

therefore more likely to display signs of anxiety. In other words, raising the

stakes has a similar effect on liars and truth tellers, which makes the difference

19 Bond, C. F., & DePaulo, B. M. (2006). Accuracy of deception judgements. Personality and

Social Psychology Review, 10, 214–234. Doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_2

20 Hartwig, M., & Bond, C. F. (2011). Why do lie-catchers fail? A lens model meta-analysis of

human lie judgments. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 643–659. Doi: 10.1037/a0023589

21 Frank, M. G., & Feeley, T. H. (2003). To catch a liar: Challenges for research in lie detection

training. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 31, 58–75. Doi: 10.1080/00909880305377;

Hauch, V., Sporer, S. L., Michael, S. W., & Meissner, C. A. (2014). Does training improve the

detection of deception? A meta-analysis. Communication Research published online 25 May 2014

Doi: 10.1177/0093650214534974

22 Hartwig, M., & Bond, C. F. (2014). Lie detection from multiple cues: A meta-analysis. Applied

Cognitive Psychology, 28, 661–667. Doi: 10.1002/acp.3052.

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses 237

between them not more pronounced than in low-stakes situations.23 In a well-

known American police manual24 research is cited in which police detectives

attempted to detect truths and lies in real life interviews with arsonists, rapists

and murderers.25 Inbau et al.26 report that the accuracy rates were higher than

typically found in laboratory research. This is true and accuracy rates of 65 %

were found. However, the (British) police detectives in that study relied more on

speech than behavior. The research actually found a negative relationship

between accuracy and paying attention to the nonverbal cues outlined in the

Inbau et al. manual as “diagnostic cues to deceit,” such as gaze aversion,

making grooming gestures, and shifting position. The more the officers said to

rely on such – in fact non-diagnostic - cues to deceit, the worse they performed

in detecting lies.

2.2 Factors contributing to the myth about the strong

relationship between nonverbal behavior and deception

The idea that nonverbal behavior is revealing about deception is a myth. Two

factors probably contribute to this myth about the importance of nonverbal

behavior in lie detection. First, people often overestimate the importance of

nonverbal behavior in the exchange of information. Those who argue in favor

of examining nonverbal cues to detect deceit often use quotes such as ‘according

to various social studies as much as 70 % of a message communicated between

persons occurs at a nonverbal level.27 We took this quote from a police manual.

Other practitioners mention somewhat different percentages, but all commonly

claim that nonverbal behavior is far more important in the exchange of informa-

tion than verbal behavior. The social studies they refer to come from the

psychologist Albert Mehrabian and published in his book Silent Messages.28

23 Hartwig, M., & Bond, C. F. (2014). Lie detection from multiple cues: A meta-analysis. Applied

Cognitive Psychology, 28, 661–667. Doi: 10.1002/acp.3052.

24 Inbau, F. E., Reid, J. E., Buckley, J. P., & Jayne, B. C. (2013). Criminal interrogation and

confessions, 5th edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

25 Mann, S., Vrij, A., & Bull, R. (2002). Suspects, lies and videotape: An analysis of authentic

high-stakes liars. Law and Human Behavior, 26, 365–376. DOI: 10.1023/A:1,015,332,606,792

26 Inbau, F. E., Reid, J. E., Buckley, J. P., & Jayne, B. C. (2013). Criminal interrogation and

confessions, 5th edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

27 Inbau, F. E., Reid, J. E., Buckley, J. P., & Jayne, B. C. (2013). Criminal interrogation and

confessions, 5th edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. The quote appears on page

122.

28 Mehrabian, A. (1971). Silent messages, 1st edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

238 A. Vrij and J. Turgeon

Mehrabian’s research dealt with the communication of positive or negative

emotions via single spoken words, like “dear” or “terrible.” Obviously, if some-

one says little, verbal behavior cannot have much influence on the impression

information. This does not mean that Mehrabian’s findings can be applied to

interview settings such as a courtroom, where witness-interviewees say consid-

erably more than a single word. By Googling “Mehrabian” many links come up

labelled “Mehrabian myths” and these links explain that Mehrabian’s work is

taken entirely out of context. Mehrabian himself shares that opinion, given the

following quote:

I am obviously uncomfortable about misquotes of my work. From the very beginning I

have tried to give people the correct limitations of my findings. Unfortunately the field of

self-styled “corporate image consultants” or “leadership consultants” has numerous prac-

titioners with very little psychological expertise (31 October 2002).

The second factor that may contribute to the myth about the importance of

nonverbal behavior in lie detection is the idea that behavior is more difficult to

control than speech. Four factors contribute to this idea.29 First, there are certain

automatic links between emotions and nonverbal behavior (e. g., the moment

people become afraid, their bodies jerk backwards), whereas automatic links

between emotions and speech content do not exist. Second, people are more

practiced in using words than in using behavior, and this practice makes perfect.

Third, people are more aware of what they are saying than of how they are

behaving, and this awareness makes people better at controlling it. Fourth,

verbally people can pause and think what to say, whereas nonverbally people

cannot be silent. These reasons seem to underestimate the difficulty of telling a

convincing and plausible lie and ignore that investigators can make lying

verbally very difficult by using the right interview techniques. The next section

will discuss four interview techniques that are effective to elicit verbal cues to

deceit.

2.3 Interviewing/questioning to detect deception: verbal cues

to deceit

When a person is being questioned or interviewed, lying is often more mentally

taxing than truth telling which the person posing questions can exploit by

29 DePaulo, B. M., & Kirkendol, S. E. (1989). The motivational impairment effect in the commu-

nication of deception. In J. C. Yuille (Ed.), Credibility assessment (pp. 51–70). Dordrecht, the

Netherlands: Kluwer.

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses 239

making additional requests, making it more difficult - affecting liars more than

truth tellers, because liars have fewer cognitive abilities left over to deal with

these additional requests. A good technique in this context is to ask the person,

after giving his/her account in chronological order to do this subsequently in

reverse order: “Could you tell us again what you did in the afternoon of March 22

2016, but now starting at the end of the afternoon and going backwards to the

beginning of the afternoon?” This task is more challenging for liars than truth

tellers and may result in liars making more contradictions than truth tellers do.

(Therefore, the jury instruction that includes a credibility evaluation factor

concerning whether the witness contradicted himself or herself, is valid.)

Asking the person to give the account in reverse order may also result in

truth tellers providing more additional information than liars do. This reverse

order technique is an effective technique when interviewing cooperative wit-

nesses (truth tellers) as it makes them to think about the event again but this

time from a different perspective, which often leads to additional information. In

contrast, liars are concerned with ‘consistency’ and will try to report again what

they have said before. This will not lead to additional information.

Truth tellers never say everything they know when invited to tell all they can

remember, in part because this is not how people typically communicate (in

daily interactions people give each other brief summaries of activities rather

than detailed descriptions) and in part because people do not know what

amount of detail is expected from them.30 An effective way to raise someone’s

expectations about how much detail is required is to provide them with a ‘model

statement’, an example of a detailed account (about an event unrelated to the

topic the interviewee is interviewed about to prevent them “copying” the text

from the model statement). Truth tellers typically add more detail about the core

event (the part of the event that matters) after the model statement than liars.

Liars may find it mentally difficult to give additional detail (after all, it needs to

sound plausible) but they may also be reluctant to say more out of fear that it

will eventually reveal their lies.31

Liars prepare themselves for anticipated interrogation by preparing possible

answers to questions they expect to be asked.32 This strategy has a limitation. It

30 Vrij, A., Hope, L., & Fisher, R. P. (2014). Eliciting reliable information in investigative interviews.

Policy Insights from Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1, 129–136. Doi: 10.1177/2,372,732,214,548,592

31 Leal, S., Vrij, A., Warmelink, L., Vernham, Z., & Fisher, R. (2015). You cannot hide your

telephone lies: Providing a model statement as an aid to detect deception in insurance tele-

phone calls. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 20, 129–146. Doi: 10.1111/lcrp.12017

32 Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., & Strömwall, L. (2007). Guilty and innocent suspects’ strategies during

police interrogations. Psychology, Crime, & Law, 13, 213–227. Doi: 10.1080/10,683,160,600,750,264

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

240 A. Vrij and J. Turgeon

will be fruitful only if liars correctly anticipate which questions will be asked.

This limitation can be exploited by asking questions that liars do not anticipate.

Though liars can refuse to answer unexpected questions by saying “I don’t

know” or “I can’t remember,” such responses will create suspicion if these

questions are about core aspects of the target event. A liar, therefore, has little

option other than to fabricate a plausible answer on the spot, which is mentally

taxing. One way that has proven to be successful in using the unexpected

questions approach is by asking expected questions followed by unexpected

questions. Liars are likely to have prepared answers to the expected questions

and may therefore be able to answer them in considerable detail. However, they

will not have prepared answers to the unexpected questions and may therefore

struggle to generate detailed answers to them. For truth tellers the unexpected

questions are equally unexpected but they do not find it more difficult to answer

the unexpected questions than the expected questions and can answer them

with similar ease and in similar detail.33

The Verifiability Approach is a fourth new approach which assists in detect-

ing lies. Central to the Verifiability Approach are two assumptions.34 First, liars

realize that providing many details is beneficial for them because detailed

accounts are more likely to be believed. Second, liars prefer to avoid mentioning

too many details out of fear that investigators can check such details and will

discover that they are lying. A strategy that compromises these two conflicting

motivations is to provide details that cannot be verified. Liars prefer to provide

details that are difficult to verify (e. g., “Several people walked by when I sat

there”) and avoid providing details that are easy to verify (e. g., “I phoned my

friend Zvi at 10.30 this morning).35 This difference in providing verifiable details

between truth tellers and liars becomes more pronounced if interviewees first

are asked “to provide details the investigator can check.” Truth tellers then

report details they did not think about before (“I think I saw a CCTV camera in

that street, so you can check the footage,” “I paid lunch with my credit card so

33 Lancaster, G. L. J., Vrij, A., Hope, L., & Waller, B. (2012). Sorting the liars from the truth

tellers: The benefits of asking unanticipated questions. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 27, 107–

114. Doi: 10.1002/acp.2879; Warmelink, L., Vrij, A., Mann, S., Jundi, S., & Granhag, P. A. (2012).

Have you been there before? The effect of experience and question expectedness on lying about

intentions. Acta Psychologica, 141, 178–183. Doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2012.07.011

34 Nahari, G., Vrij, A., & Fisher, R. P. (2014). Exploiting liars’ verbal strategies by examining the

verifiability of details. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 19, 227–239, Doi: 10.1111/j.2044–

8333.2012.02069.x

35 See for a review of this research: Vrij, A. & Nahari, G. (in press). The Verifiability Approach

In J. J. Dickinson, N. Schreiber Compo, R. N. Carol, B. L. Schwartz, & M. R. McCauley (Eds.)

Evidence-Based Investigative Interviewing. New York, U.S.A.: Routledge Press.

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses 241

my receipt will confirm that I was in that restaurant at that particular time”),

whereas liars, by definition, cannot provide checkable details. Verifiable detail

include: (i) activities with identifiable or named persons who the interviewer can

consult, (ii) activities that have been witnessed by identifiable or named persons

who the interviewer can consult; (iii) activities that the interviewee believes may

have been captured on CCTV; (iv) activities that may have been recorded

through technology, such as using debit cards, mobile phones, or computers.

None of these proven approaches to evaluate credibility include considering

nonverbal behavior but rather all involve carefully evaluating verbal behavior.

As stated and discussed above, the concept that nonverbal behavior is a reliable

factor to evaluate credibility is a myth.

3 Conclusion

Current well-accepted scientific studies support that human evaluation of a

person’s credibility based upon nonverbal behaviors such as manner and

appearance is unreliable in determining believability, even when the determina-

tion is made by an expert. Jury instructions that advise a juror to base credibility

determinations upon how a witness looked and acted while testifying are thus

invalid. The legal community therefore should consider substantially revising

jury instructions and craft more complete instructions to jurors by educating

them that nonverbal cues have no connection to a witness’s truthfulness or

credibility.

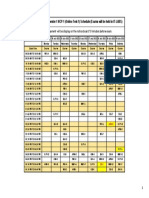

Appendix A: Selected State Jury Instructions

Pennsylvania jury instructions on witness credibility

Criminal 4.17 – “credibility of witnesses, general”

1. As judges of the facts, you are sole judges of the credibility of the witnesses

and their testimony. This means you must judge the truthfulness and

accuracy of each witness’s testimony and decide whether to believe all or

part or none of that testimony. The following are some of the factors that

you may and should consider when judging credibility and deciding

whether or not to believe testimony:

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

242 A. Vrij and J. Turgeon

a. Was the witness able to see, hear, or know the things about which [he]

[she] testified?

b. How well could the witness remember and describe the things about

which [he] [she] testified?

[c. Was the ability of the witness to see, hear, know, remember, or

describe those things affected by youth, old age, or by any physical,

mental, or intellectual deficiency?]

d. Did the witness testify in a convincing manner? [How did [he] [she]

look, act, and speak while testifying? Was [his] [her] testimony

uncertain, confused, self-contradictory, or evasive?]

e. Did the witness have any interest in the outcome of the case, bias,

prejudice, or other motive that might affect [his] [her] testimony?

f. How well does the testimony of the witness square with the other

evidence in the case, including the testimony of other witnesses?

[Was it contradicted or supported by the other testimony and evi-

dence? Does it make sense?]

[g. [give other factors]].

[2. If you believe some part of the testimony of a witness to be inaccurate,

consider whether the inaccuracy casts doubt upon the rest of his or her

testimony. This may depend on whether he or she has been inaccurate in

an important matter or a minor detail and on any possible explanation. For

example, did the witness make an honest mistake or simply forget or did

[he] [she] deliberately falsify?]

[3. While you are judging the credibility of each witness, you are likely to be

judging the credibility of other witnesses or evidence. If there is a real,

irreconcilable conflict, it is up to you to decide which, if any, conflicting

testimony or evidence to believe.]

[4. As sole judges of credibility and fact, you, the jurors, are responsible to

give the testimony of every witness, and all the other evidence, whatever

credibility and weight you think it deserves.]

Pa. SSJI (Crim) 4.17 (2016 3rd Ed.) (emphasis added).

Civil 4.20 – “believability of witnesses generally”

As judges of the facts, you decide the believability of the witnesses’ testimony.

This means that you decide the truthfulness and accuracy of each witness’s

testimony and whether to believe all, or part, or none of each witness’s

testimony.

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

Evaluating Credibility of Witnesses 243

The following are some of the factors that you may and should consider

when determining the believability of the witnesses and their testimony:

a. How well could each witness see, hear, or know the things about which he

or she testified?

b. How well could each witness remember and describe those things?

c. Was the ability of the witness to see, hear, know, remember, or describe

those things affected by age or any physical, mental, or intellectual

disability?

d. Did the witness testify in a convincing manner? How did the witness

look, act, and speak while testifying?

e. Was the witness’s testimony uncertain, confused, self-contradictory, or

presented in an evasive manner?

f. Did the witness have any interest in the outcome of this case, or any bias,

or any prejudice, or any other motive that might have affected his or her

testimony?

g. Was a witness’s testimony contradicted or supported by other witnesses’

testimony or other evidence?

h. Does the testimony make sense?

i. If you believe some part of the testimony of a witness to be inaccurate,

consider whether that inaccuracy cast doubt upon the rest of that same

witness’s testimony. You should consider whether the inaccuracy is in an

important matter or a minor detail.

You should also consider any possible explanation for the inaccuracy. Did

the witness make an honest mistake or simply forget, or was there a

deliberate attempt to present false testimony?

j. If you decide that a witness intentionally lied about a significant fact that

may affect the outcome of the case, you may, for that reason alone, choose

to disbelieve the rest of that witness’s testimony. But, you are not required

to do so.

k. As you decide the believability of each witness’s testimony, you will at the

same time decide the believability of other witnesses and other evidence in

the case.

l. If there is a conflict in the testimony, you must decide which, if any,

testimony you believe is true.

As the only judges of believability and facts in this case, you, the jurors, are

responsible to give the testimony of every witness, and all the other evidence,

whatever weight you think it is entitled to receive.

Pa. SSJI (Civ) 4.20 (2017 2nd Ed.) (emphasis added)

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

244 A. Vrij and J. Turgeon

Jury instruction sample excerpts for states that include a “nonverbal behavior

factor” for evaluating credibility

California (Criminal):

In evaluating a witness’s testimony, you may consider anything that reason-

ably tends to prove or disprove the truth or accuracy of that testimony. Among

the factors that you may consider are: … What was the witness’s behavior

while testifying? … What was the witness’s attitude about the case or about

testifying?

California Criminal Jury Instructions (CALCRIM) No. 266 (2018) (emphasis

added), http://www.courts.ca.gov/partners/documents/calcrim_2018_edition.

pdf.

Florida (Civil):

… In evaluating the believability of any witness and the weight you will give

the testimony of any witness, you may properly consider the demeanor of

the witness while testifying; the frankness or lack of frankness of the witness;

the intelligence of the witness; any interest the witness may have in the outcome

of the case; the means and opportunity the witness had to know the facts about

which the witness testified; the ability of the witness to remember the matters

about which the witness testified; and the reasonableness of the testimony of the

witness, considered in the light of all the evidence in the case and in the light

of your own experience and common sense.

Florida Standard Jury Instructions - Civil Cases, No. 601.2(a) (2018) (empha-

sis added), http://www.floridasupremecourt.org/civ_jury_instructions/instruc

tions.shtml.

Massachusetts (Criminal):

… In deciding whether to believe a witness and how much importance to

give a witness’s testimony, you must look at all the evidence, drawing on

your own common sense and experience of life. Often it may not be what a

witness says, but how he says it that might give you a clue whether or not

to accept his version of an event as believable. You may consider a wit-

ness’s appearance and demeanor on the witness stand, his frankness or lack

of frankness in testifying, whether his testimony is reasonable or unreasonable,

probable or improbable.

Massachusetts Criminal Model Jury Instructions for Use in the District Court,

No. 2.260 (2017) (emphasis added), https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/

2016/11/vc/2260-credibility-of-witnesses.pdf.

Brought to you by | Göteborg University - University of Gothenburg

Authenticated

Download Date | 2/6/20 10:52 AM

You might also like

- Application of Psychology in The Legal SystemDocument18 pagesApplication of Psychology in The Legal SystemOpsOlavario100% (2)

- Nourhan Habib - Forensic Psychology - Curtis FlowersDocument14 pagesNourhan Habib - Forensic Psychology - Curtis FlowersSima Habib100% (1)

- Offender ProfillingDocument192 pagesOffender Profillingcriminalistacris100% (3)

- Associate CalassDocument151 pagesAssociate CalassMuhammad Naveed AnjumNo ratings yet

- Assignment Topic 3 Cá NhânDocument9 pagesAssignment Topic 3 Cá NhânTrường Tiểu học Phú Thịnh Hưng YênNo ratings yet

- ESRB Response To Senator HassanDocument4 pagesESRB Response To Senator HassanPolygondotcomNo ratings yet

- Networked Knowledge Psychological Issues Homepage DR Robert N MolesDocument28 pagesNetworked Knowledge Psychological Issues Homepage DR Robert N MolesSamuel BallouNo ratings yet

- Body Language and Veracity - Lord LeggattDocument21 pagesBody Language and Veracity - Lord LeggattRajah BalajiNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document5 pagesUnit 3ShivaniNo ratings yet

- The Trial Process, Demeanor Evidence and Admissibility 1Document15 pagesThe Trial Process, Demeanor Evidence and Admissibility 1priyanshuNo ratings yet

- John E. Reid and Associates, Inc.: Clarifying Misrepresentations About Law Enforcement Interrogation TechniquesDocument36 pagesJohn E. Reid and Associates, Inc.: Clarifying Misrepresentations About Law Enforcement Interrogation TechniquesCHUKS BRENDANNo ratings yet

- Clarifying Misrepresntations of Law Enforcement Interrgoation Techniques Feb 2022 2022 03-18-140724 NabuDocument36 pagesClarifying Misrepresntations of Law Enforcement Interrgoation Techniques Feb 2022 2022 03-18-140724 NabugrandamianbNo ratings yet

- Cornell Law Review ArticleDocument30 pagesCornell Law Review Articlepalmite9No ratings yet

- Chapter - 1: Circumstantial Evidence Is Evidence That Relies On An Inference To Connect It To ADocument17 pagesChapter - 1: Circumstantial Evidence Is Evidence That Relies On An Inference To Connect It To ARupali RamtekeNo ratings yet

- Re Evaluating The Credibility of Eyewitness Testimony The Misinformation Effect and The Overcritical JurorDocument25 pagesRe Evaluating The Credibility of Eyewitness Testimony The Misinformation Effect and The Overcritical Juroralysa.leemynnNo ratings yet

- Evidence Law ProjectDocument10 pagesEvidence Law ProjectTulika GuptaNo ratings yet

- Methods of InterrogationDocument16 pagesMethods of InterrogationJoshua ReyesNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper # 1-"How To Spot A Liar", by Pamela Meyer, TED TalksDocument7 pagesReaction Paper # 1-"How To Spot A Liar", by Pamela Meyer, TED TalksRoel DagdagNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument7 pagesChapter IAnna Marie BorciNo ratings yet

- Bloom 3Document118 pagesBloom 3jbsayadNo ratings yet

- ProjDocument19 pagesProjAmar SinghNo ratings yet

- Evidence 7TH SemDocument18 pagesEvidence 7TH SemANANYA AGGARWALNo ratings yet

- Psycho ProjectDocument19 pagesPsycho ProjectKashish ChhabraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 15 Social Psychology in CourtDocument31 pagesChapter 15 Social Psychology in CourtReyalyn AntonioNo ratings yet

- Principles of Evidence: Jon SmibertDocument240 pagesPrinciples of Evidence: Jon SmibertArbab Ihtishamul Haq KhalilNo ratings yet

- Eyewitness Testimony Is Not Always AccurateDocument7 pagesEyewitness Testimony Is Not Always AccuratejaimieNo ratings yet

- NAME: Sushmitha.S REG NO: 21BLA1112 SUBJECT: Law of Evidence SUBMITTED TO: Prof. Arjun DATE: 20/07/23Document9 pagesNAME: Sushmitha.S REG NO: 21BLA1112 SUBJECT: Law of Evidence SUBMITTED TO: Prof. Arjun DATE: 20/07/23Sushmitha SelvanathanNo ratings yet

- CDI 313 Module 2Document28 pagesCDI 313 Module 2Anna Rica SicangNo ratings yet

- De-Ritualising The Criminal TrialDocument39 pagesDe-Ritualising The Criminal TrialDavid HarveyNo ratings yet

- Eye Witness Memory: Convictions Were Subsequently Overturned With DNA Evidence, See The Innocence Project WebsiteDocument2 pagesEye Witness Memory: Convictions Were Subsequently Overturned With DNA Evidence, See The Innocence Project WebsiteashvinNo ratings yet

- Circumstantial EvidenceDocument15 pagesCircumstantial Evidencegauravsingh0110No ratings yet

- Monika ReportDocument110 pagesMonika ReportMohit PacharNo ratings yet

- John E. Reid and Associates, IncDocument14 pagesJohn E. Reid and Associates, IncAngelika BandiwanNo ratings yet

- Bite MarksDocument54 pagesBite Marksrobsonconlaw100% (1)

- Beyond PDFDocument7 pagesBeyond PDFLuis gomezNo ratings yet

- Eyewitness EvidenceDocument31 pagesEyewitness Evidencea_gonzalez676No ratings yet

- Circumstantial EvidenceDocument15 pagesCircumstantial EvidenceJugheadNo ratings yet

- Report Wrongful ConvictionDocument16 pagesReport Wrongful ConvictionLorene bby100% (1)

- Can Children Provide Reliable Eyewitness Testimony 01Document2 pagesCan Children Provide Reliable Eyewitness Testimony 01Sam HoqNo ratings yet

- Module 2Document4 pagesModule 2GULTIANO, Ricardo Jr C.No ratings yet

- Witness Interviewing and Suspect Interrogation Nyanza 22-23 Feb 2021 Class BDocument137 pagesWitness Interviewing and Suspect Interrogation Nyanza 22-23 Feb 2021 Class BGabriel Mganga100% (1)

- Lying To A SuspectDocument2 pagesLying To A SuspectAdrian IcaNo ratings yet

- Hearsay Evidence and Its General ExceptionsDocument2 pagesHearsay Evidence and Its General ExceptionsAabir ChattarajNo ratings yet

- American Justice in the Age of Innocence: Understanding the Causes of Wrongful Convictions and How to Prevent ThemFrom EverandAmerican Justice in the Age of Innocence: Understanding the Causes of Wrongful Convictions and How to Prevent ThemNo ratings yet

- JYSONDocument5 pagesJYSONLhiereen AlimatoNo ratings yet

- Procedural Fairness, The Criminal Trial and Forensic Science and MedicineDocument36 pagesProcedural Fairness, The Criminal Trial and Forensic Science and MedicineCandy ChungNo ratings yet

- Newring and OdonohueDocument27 pagesNewring and Odonohuegabrielolteanu101910No ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia: A Project OnDocument18 pagesJamia Millia Islamia: A Project OnSandeep ChawdaNo ratings yet

- Dna: Evidentiary Value of Dna TestingDocument6 pagesDna: Evidentiary Value of Dna TestingAnkit NandeNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Exercise (4.1-4.4)Document8 pagesUnit 3 Exercise (4.1-4.4)xTruthNo ratings yet

- ForensicDocument23 pagesForensicManjot Singh RaiNo ratings yet

- Inglés CriminológicoDocument7 pagesInglés CriminológicoGisela CNo ratings yet

- The Standard of Proof in Criminal Proceedings: The Threshold To Prove Guilt Under Ethiopian LawDocument33 pagesThe Standard of Proof in Criminal Proceedings: The Threshold To Prove Guilt Under Ethiopian LawHenok TeferiNo ratings yet

- Face-Coverings, Demeanour Evidence and The Right To A Fair Trial Lessons From The USA and CanadaDocument19 pagesFace-Coverings, Demeanour Evidence and The Right To A Fair Trial Lessons From The USA and CanadaKen MutumaNo ratings yet

- Trial ProceduresDocument6 pagesTrial ProceduresChristopher LaneNo ratings yet

- The Multiple Dimensions of Tunnel Vision - Findley e ScottDocument108 pagesThe Multiple Dimensions of Tunnel Vision - Findley e ScottPedro Ivo De Moura TellesNo ratings yet

- Expert Evidence Detailed PDFDocument77 pagesExpert Evidence Detailed PDFVarunPratapMehtaNo ratings yet

- Polygraphy Look Judicail Vala PDFDocument47 pagesPolygraphy Look Judicail Vala PDFishmeet kaurNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Forensic Science in The United States: A Path ForwardDocument12 pagesStrengthening Forensic Science in The United States: A Path Forwardchrisr310No ratings yet

- Cases in EvidenceDocument237 pagesCases in EvidenceMary Grace Dionisio-RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Victimless CrimeDocument65 pagesDissertation Victimless CrimeBenjamin SalmonNo ratings yet

- Contextual Bias in Verbal Credibility AssessmentDocument13 pagesContextual Bias in Verbal Credibility AssessmentAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Rape Victim Assessment: Findings by Psychiatrists and Psychologists at Weskoppies HospitalDocument5 pagesRape Victim Assessment: Findings by Psychiatrists and Psychologists at Weskoppies HospitalAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Hamlin Et Al. (2018) - The Dimensions of Deception Detection Self Reported Deception Cue Use Is Underpinned by Two Broad FactorsDocument9 pagesHamlin Et Al. (2018) - The Dimensions of Deception Detection Self Reported Deception Cue Use Is Underpinned by Two Broad FactorsAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisDocument14 pagesPerceptions of Factors Associated With Inclusive Work and Learning Environments in Health Care Organizations A Qualitative Narrative AnalysisAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Deprived of Human Rights: Disability & SocietyDocument7 pagesDeprived of Human Rights: Disability & SocietyAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Australian Clinical Consensus Guideline: The Diagnosis and Acute Management of Childhood StrokeDocument13 pagesAustralian Clinical Consensus Guideline: The Diagnosis and Acute Management of Childhood StrokeAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Denault Et Al. (2019) - The Detection of Deception During TrialsDocument9 pagesDenault Et Al. (2019) - The Detection of Deception During TrialsAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Science and Justice: Samuel J. Leistedt, Paul LinkowskiDocument4 pagesScience and Justice: Samuel J. Leistedt, Paul LinkowskiAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Wright & Wheatcroft. (2017) - Police Officers Beliefs About, and Use Of, Cues To DeceptionDocument14 pagesWright & Wheatcroft. (2017) - Police Officers Beliefs About, and Use Of, Cues To DeceptionAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Dunbar Et Al. (2017) - The Viability of Using Rapid Judgments As A Method of Deception DetectionDocument17 pagesDunbar Et Al. (2017) - The Viability of Using Rapid Judgments As A Method of Deception DetectionAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Nahari Et Al. (2019) - Languaje of Lies Urgent Issues and Prospects in Verbal Lie Detection ResearchDocument24 pagesNahari Et Al. (2019) - Languaje of Lies Urgent Issues and Prospects in Verbal Lie Detection ResearchAndrea Guerrero ZapataNo ratings yet

- Ramos-Yeo vs. Chua DigestDocument4 pagesRamos-Yeo vs. Chua DigestEmir MendozaNo ratings yet

- S4HANA For Consumer ProductsDocument18 pagesS4HANA For Consumer ProductsSandro Luna BazoNo ratings yet

- Securities and Exchange Commission vs. Picop Resources Inc.Document2 pagesSecurities and Exchange Commission vs. Picop Resources Inc.Arianne AstilleroNo ratings yet

- Barakah Sources Time Management PDFDocument13 pagesBarakah Sources Time Management PDFFadimatou100% (3)

- 96 Kuli Maratha Surname List Download PDFDocument3 pages96 Kuli Maratha Surname List Download PDFsatyen Turki0% (1)

- Poll Crosstabs - EconomyDocument73 pagesPoll Crosstabs - EconomyLas Vegas Review-JournalNo ratings yet

- Service MarketingDocument20 pagesService Marketingankit_will100% (4)

- The Gender of The GiftDocument3 pagesThe Gender of The GiftMarcia Sandoval EsparzaNo ratings yet

- Phed213 PrelimDocument1 pagePhed213 PrelimKaye OrtegaNo ratings yet

- GluttonyDocument2 pagesGluttonyFrezel BasiloniaNo ratings yet

- Sonnet Is A 14 Lines Poem Written Iambic PentameterDocument2 pagesSonnet Is A 14 Lines Poem Written Iambic PentameterS ShreeNo ratings yet

- Informant Policies & Practices Evaluation Committee ReportDocument47 pagesInformant Policies & Practices Evaluation Committee ReportLisa Bartley100% (1)

- Sol Gen Vs MMADocument2 pagesSol Gen Vs MMAJude ChicanoNo ratings yet

- Brochure - 6th Annual Treasury Management India Summit 2022Document13 pagesBrochure - 6th Annual Treasury Management India Summit 2022Finogent AdvisoryNo ratings yet

- PUNJAB POLICE Test 78Document9 pagesPUNJAB POLICE Test 78Jan AlamNo ratings yet

- Law of ContractDocument85 pagesLaw of ContractDebbie PhiriNo ratings yet

- Balbheemloan Sanction LetterDocument6 pagesBalbheemloan Sanction LetterVenkatesh DoodamNo ratings yet

- Dome Tank Eng PDFDocument2 pagesDome Tank Eng PDFDustin BooneNo ratings yet

- Dallas Business Journal 20150102 - SiDocument28 pagesDallas Business Journal 20150102 - Sisarah123No ratings yet

- MBA Class of 2024 Semester-1 NCP-1 (Online Test-1) Schedule (Exams Will Be Held in IT-LABS)Document1 pageMBA Class of 2024 Semester-1 NCP-1 (Online Test-1) Schedule (Exams Will Be Held in IT-LABS)XyzNo ratings yet

- Danh Vo Paris Press ReleaseDocument18 pagesDanh Vo Paris Press ReleaseTeddy4321No ratings yet

- 2281 s13 QP 21Document4 pages2281 s13 QP 21IslamAltawanayNo ratings yet

- Communion Songs For Advent SeasonDocument1 pageCommunion Songs For Advent Seasonbinatero nanetteNo ratings yet

- SafetyDocument3 pagesSafetymseroplanoNo ratings yet

- Usurf and VPNDocument11 pagesUsurf and VPNvan_laoNo ratings yet

- Betel Chewing in The PhilippinesDocument1 pageBetel Chewing in The PhilippinesMariz QuilnatNo ratings yet

- Mysticism in Shaivism and Christianity PDFDocument386 pagesMysticism in Shaivism and Christianity PDFproklos100% (2)