Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Have Construction Joints in Concrete. Nothing Else To Realistically Discuss On That Point

Have Construction Joints in Concrete. Nothing Else To Realistically Discuss On That Point

Uploaded by

MarielCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Brazing - Fundamentals - 1Document7 pagesBrazing - Fundamentals - 1Sadashiw PatilNo ratings yet

- Reinforced Concrete Buildings: Behavior and DesignFrom EverandReinforced Concrete Buildings: Behavior and DesignRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- AUH Muncipality Guideline-2of 2Document43 pagesAUH Muncipality Guideline-2of 2cbecdmNo ratings yet

- Aashto T 313-12 BBRDocument22 pagesAashto T 313-12 BBRclint silNo ratings yet

- ASTM D945-16 Standard Test Methods For Rubber Properties in Compression or Shear (Mechanical Oscillograph)Document13 pagesASTM D945-16 Standard Test Methods For Rubber Properties in Compression or Shear (Mechanical Oscillograph)Andre Rodriguez SpirimNo ratings yet

- What Are The Basics of Structural AnalysisDocument8 pagesWhat Are The Basics of Structural AnalysisKutty MansoorNo ratings yet

- Narative ReportDocument2 pagesNarative ReportKarl Angelo CuellarNo ratings yet

- RCC Structures StairDocument31 pagesRCC Structures Staira_j_sanyal259No ratings yet

- CRSI The Designer's ResponsibilityDocument16 pagesCRSI The Designer's ResponsibilityAdam Jones100% (1)

- Tabinas - Ae3 - Activity 01Document22 pagesTabinas - Ae3 - Activity 01Lemuel Kim Cera TabinasNo ratings yet

- Advanced Design of Box GirdersDocument12 pagesAdvanced Design of Box Girderssujups100% (1)

- Steel Interchange: Modern Steel's Monthly Steel Interchange Is For You!Document2 pagesSteel Interchange: Modern Steel's Monthly Steel Interchange Is For You!Andres CasadoNo ratings yet

- Corrosion in TMT Rebar - ReportDocument37 pagesCorrosion in TMT Rebar - ReportRajbanul AkhondNo ratings yet

- Preface: Material in The Sense That It Is Fully Recyclable. PresentlyDocument3 pagesPreface: Material in The Sense That It Is Fully Recyclable. PresentlyKasia MazurNo ratings yet

- Question and Answers-AISCDocument15 pagesQuestion and Answers-AISCkiranNo ratings yet

- CivilDocument4 pagesCivilCamilaCMartinezHNo ratings yet

- Marine Structures Exam QuestionsDocument8 pagesMarine Structures Exam QuestionsAnonymous JSHUTpNo ratings yet

- Analysis On The Causes of Cracks in BridgesDocument14 pagesAnalysis On The Causes of Cracks in BridgesNguyễn Văn MinhNo ratings yet

- Construction JointDocument1 pageConstruction JointNumair Ahmad FarjanNo ratings yet

- Composite and Steel Construction CompendiumDocument3 pagesComposite and Steel Construction CompendiumΤε ΧνηNo ratings yet

- Modern Steel Construction's MonthlyDocument2 pagesModern Steel Construction's MonthlyapirakqNo ratings yet

- Some Mooted Questions in Reinforced Concrete Design American Society of Civil Engineers Transactions Paper No 1169 Volume LXX Dec 1910 2Document148 pagesSome Mooted Questions in Reinforced Concrete Design American Society of Civil Engineers Transactions Paper No 1169 Volume LXX Dec 1910 2Suleiman AldbeisNo ratings yet

- ScarryBNZSEEMarch2015Final CorrectedDocument24 pagesScarryBNZSEEMarch2015Final CorrectedJoão Paulo MendesNo ratings yet

- Axial Load Capacity of The ColumnDocument3 pagesAxial Load Capacity of The ColumnSadanand RaoNo ratings yet

- Design of Beams in Structural SteelDocument15 pagesDesign of Beams in Structural SteelMaqsood92% (13)

- Design of Steel Structure BeamDocument17 pagesDesign of Steel Structure BeamShahrah ManNo ratings yet

- SP ACI TORSION Overview CSGV 20200930Document30 pagesSP ACI TORSION Overview CSGV 20200930ahmedhatemlabibNo ratings yet

- c5099312 2808 473f 9c27 d7c851902a3f.handout10821ES10821CompositeBeamDesignExtensioninRobotStructuralAnalsisProfessional2016Document23 pagesc5099312 2808 473f 9c27 d7c851902a3f.handout10821ES10821CompositeBeamDesignExtensioninRobotStructuralAnalsisProfessional2016antonio111aNo ratings yet

- MSP PrestressDocument14 pagesMSP PrestressAmit MondalNo ratings yet

- Advanced Design of Concrete StructuresDocument115 pagesAdvanced Design of Concrete StructuresAb Rahman BaharNo ratings yet

- Modelling and Analysis of SteelDocument24 pagesModelling and Analysis of SteelJaleel ClaasenNo ratings yet

- PSD Test NotesDocument21 pagesPSD Test Notesmuhfil MuhfilNo ratings yet

- CIVE1151 Learning Guide 2012Document102 pagesCIVE1151 Learning Guide 2012Johnny Le100% (1)

- Design and Analysis of Moment Resisting Bases of Steel Column by Using IS:800-2007 Code and AISC-2010Document6 pagesDesign and Analysis of Moment Resisting Bases of Steel Column by Using IS:800-2007 Code and AISC-2010Manju BirjeNo ratings yet

- Steel Placement HandbookDocument20 pagesSteel Placement Handbookvarshneyrk@rediffmail.comNo ratings yet

- Torsion Design of Structural ConcreteDocument8 pagesTorsion Design of Structural ConcreteEduardo Núñez del Prado100% (1)

- Reinforced Cement Concrete DesignDocument5 pagesReinforced Cement Concrete DesignKimo KenoNo ratings yet

- Fasteners: The ESG ReportDocument4 pagesFasteners: The ESG ReportAnton SurviyantoNo ratings yet

- Numerical Analysis Group 10 (Full Report)Document11 pagesNumerical Analysis Group 10 (Full Report)BruhNo ratings yet

- Singly and Doubly Reinforced Beams FalngDocument67 pagesSingly and Doubly Reinforced Beams Falngmajedmorshed25No ratings yet

- Script Ni BumbayDocument10 pagesScript Ni BumbayHunter BravoNo ratings yet

- 2016 Msods BeeDocument19 pages2016 Msods Beemd ashraful alamNo ratings yet

- Beam (Structure) - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 pagesBeam (Structure) - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediadonodoni0008No ratings yet

- Essay About Reinforced Concrete Design: Rizal Technological UniversityDocument6 pagesEssay About Reinforced Concrete Design: Rizal Technological UniversityEjay EmpleoNo ratings yet

- Thermal BowingDocument22 pagesThermal BowingPedro Dominguez DominguezNo ratings yet

- Topic Reading 7 - Catalog ComponentsDocument28 pagesTopic Reading 7 - Catalog ComponentsDan StrutheNo ratings yet

- STEELDocument27 pagesSTEEL051Bipradeep ChandaNo ratings yet

- Lateral TorsionalBucklingOfSteelBeamDocument5 pagesLateral TorsionalBucklingOfSteelBeammhmdwalid95No ratings yet

- Seismic Performance of A 3D Full Scale HDocument27 pagesSeismic Performance of A 3D Full Scale HPravasNo ratings yet

- What Is Civil EngineeringDocument1 pageWhat Is Civil Engineeringafonso123susanaNo ratings yet

- Steel Strucsdftures 3 - Composite Structures - Lecture Notes Chapter 10.2Document22 pagesSteel Strucsdftures 3 - Composite Structures - Lecture Notes Chapter 10.2iSoK11No ratings yet

- Mechanical Engineering: Latest Mechanical Engineering Interview Questions - Placement Interview QuestionsDocument18 pagesMechanical Engineering: Latest Mechanical Engineering Interview Questions - Placement Interview QuestionsHardikDevdaNo ratings yet

- A Practical Method of Design of Concrete Pedestals For Columns For Anchor Rod Tension BreakoutDocument17 pagesA Practical Method of Design of Concrete Pedestals For Columns For Anchor Rod Tension Breakoutjohn blackNo ratings yet

- Approximate Structural AnalysisDocument10 pagesApproximate Structural Analysis6082838708No ratings yet

- Lecture 3 Short Columns Small Eccentricity-Analysis-1Document57 pagesLecture 3 Short Columns Small Eccentricity-Analysis-1Syed Agha Shah AliNo ratings yet

- Design BookDocument53 pagesDesign BookmollikaminNo ratings yet

- LEC06Document59 pagesLEC06Hamza KhawarNo ratings yet

- Limit States Design 9 ContentsDocument10 pagesLimit States Design 9 Contentssom_bs790% (4)

- The Tectonics of Structural Systems - An Architectural ApproachDocument52 pagesThe Tectonics of Structural Systems - An Architectural ApproachRoque R. RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Biaxial Bending of Steel Angle Section PDFDocument3 pagesBiaxial Bending of Steel Angle Section PDFImam NakhrowiNo ratings yet

- Kahn PostTensionedFloors 317pp, 95Document317 pagesKahn PostTensionedFloors 317pp, 95banyaszmonika2002No ratings yet

- What Are Buckling Restrained Braces?Document1 pageWhat Are Buckling Restrained Braces?Vikas MouryaNo ratings yet

- Some Mooted Questions in Reinforced Concrete Design American Society of Civil Engineers, Transactions, Paper No. 1169, Volume LXX, Dec. 1910From EverandSome Mooted Questions in Reinforced Concrete Design American Society of Civil Engineers, Transactions, Paper No. 1169, Volume LXX, Dec. 1910No ratings yet

- Daily Inspection Report: A. Observation On Quality of WorkDocument2 pagesDaily Inspection Report: A. Observation On Quality of WorkMarielNo ratings yet

- Sealbond Epoxy Test ReportDocument12 pagesSealbond Epoxy Test ReportMarielNo ratings yet

- Materials Delivery Receiving ReportDocument1 pageMaterials Delivery Receiving ReportMarielNo ratings yet

- Masonry Methodology 2 FinalDocument4 pagesMasonry Methodology 2 FinalMarielNo ratings yet

- Punchlist Form: Uma ResidencesDocument3 pagesPunchlist Form: Uma ResidencesMarielNo ratings yet

- PLF 086 PDFDocument2 pagesPLF 086 PDFMarielNo ratings yet

- KyleBauer2021 ThesisDocument86 pagesKyleBauer2021 ThesisAdnan NajemNo ratings yet

- Stresses in Beams: JU. Dr. Ibrahim Abu-AlshaikhDocument20 pagesStresses in Beams: JU. Dr. Ibrahim Abu-AlshaikhqusayNo ratings yet

- Reinforced Concrete DesignDocument5 pagesReinforced Concrete DesignselinaNo ratings yet

- Bar Bending Schedule Is v3.2 - Free Lite Version - EnglishDocument13 pagesBar Bending Schedule Is v3.2 - Free Lite Version - EnglishWening Sitdi AprilianNo ratings yet

- Reinforced Concrete Design-1 Course OutlineDocument3 pagesReinforced Concrete Design-1 Course OutlineHalf EngrNo ratings yet

- An Innovative Method of Teaching Structural Analysis and DesignDocument153 pagesAn Innovative Method of Teaching Structural Analysis and DesignmNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis of Pre Engineered inDocument4 pagesDesign and Analysis of Pre Engineered inAnkur DubeyNo ratings yet

- 2 - Note de Calcule StructureDocument35 pages2 - Note de Calcule StructureJaouad Id BoubkerNo ratings yet

- Strength of Materials-II 2-2 Set-2 (A)Document13 pagesStrength of Materials-II 2-2 Set-2 (A)Sri DNo ratings yet

- Sa 1eeDocument124 pagesSa 1eeLakshmanan RamNo ratings yet

- TLO3 REINFORCING BARS NNNNDocument26 pagesTLO3 REINFORCING BARS NNNNBilly Joe Breakfast TalaugonNo ratings yet

- Cype 3d Calculations 60096Document48 pagesCype 3d Calculations 60096daniel8787No ratings yet

- Buckling Analysis by AbaqusDocument37 pagesBuckling Analysis by AbaqusGurram VinayNo ratings yet

- Lecture 03-Design of Doubly Reinforced Beam in FlexureDocument11 pagesLecture 03-Design of Doubly Reinforced Beam in FlexureOmer MehsudNo ratings yet

- Steel Penstocks - 4 Exposed PenstocksDocument40 pagesSteel Penstocks - 4 Exposed Penstocksjulio83% (6)

- 3 Structural Steel Fabrication3Document28 pages3 Structural Steel Fabrication3yradwohc100% (2)

- ECS478 CHAPTER 3-Flat SlabDocument40 pagesECS478 CHAPTER 3-Flat SlabAmron Abubakar0% (1)

- Shear Wall and Frame Interaction TerminologyDocument5 pagesShear Wall and Frame Interaction TerminologyGRD Journals100% (1)

- Ecs478 Chapter 2-TorsionDocument5 pagesEcs478 Chapter 2-TorsionMohdrafeNo ratings yet

- BP1 Bolt Connection CapacityDocument22 pagesBP1 Bolt Connection CapacityballisnothingNo ratings yet

- Bending StressDocument14 pagesBending StressDavid TurayNo ratings yet

- Session 3615 Models, Models, Models: The Use of Physical Models To Enhance The Structural Engineering ExperienceDocument9 pagesSession 3615 Models, Models, Models: The Use of Physical Models To Enhance The Structural Engineering ExperiencejmmnsantosNo ratings yet

- Iss36 Art2 - 3D Modelling of Train Induced Moving Loads On An EmbankmentDocument6 pagesIss36 Art2 - 3D Modelling of Train Induced Moving Loads On An EmbankmentbrowncasNo ratings yet

- Public Health Engineering Department (PHED) : Government of RajasthanDocument18 pagesPublic Health Engineering Department (PHED) : Government of RajasthanRajesh GangwalNo ratings yet

- SFD & BMDDocument99 pagesSFD & BMDChetanraj Patil100% (2)

- Assignment 2Document2 pagesAssignment 2johnmasefield50% (2)

Have Construction Joints in Concrete. Nothing Else To Realistically Discuss On That Point

Have Construction Joints in Concrete. Nothing Else To Realistically Discuss On That Point

Uploaded by

MarielOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Have Construction Joints in Concrete. Nothing Else To Realistically Discuss On That Point

Have Construction Joints in Concrete. Nothing Else To Realistically Discuss On That Point

Uploaded by

MarielCopyright:

Available Formats

Construction joints in concrete structures are a way of life.

In theory, it would be lovely to be able to wave our magic

wands and have a perfectly-poured monolithic structure, but you cannot pour an entire column in a single lift. There

are no magic wands, and you should not need to point to a provision in a building code to tell you that. Thou shalt

have construction joints in concrete. Nothing else to realistically discuss on that point.

All that's left is for the structural engineer and the contractor to consider the implications of construction joints and to

properly place them.

To give a bit of background regarding how construction joints in columns may affect the structural integrity of a

column, let me offer a brief bit of structural engineering knowledge to the general reader...

As you know, in a typical concrete member, you have longitudinal steel (rebar which runs the full length of the

member), rebar stirrups, and then the matrix of concrete which encases them. In a grossly oversimplified model,

each of these elements resists a certain kind of force that structural engineers design for (in reality, there's a

significant amount of interaction).

Longitudinal steel typically resists bending moments. If you were to support a beam at either end and

stand at the midspan of that beam, you'd be applying a force that would tend to bend the beam, and we

call that the bending moment. The longitudinal steel typically resists that force by offering tensile

resistance.

Rebar stirrups and the concrete matrix help the member resist shear forces. If you were in a tree,

standing next to the trunk on a branch which is way too small to support your weight, if you were to jump

up and down, the branch would snap off at the trunk and down you'd go. The failure would have

happened because you were applying a very high downwards force on the branch at a point where the

the trunk was able to react (remember Newton's laws with equal and opposite reactions...) by applying an

equal, upwards resistance force. So there's a very high upwards force immediately next to a very high

downwards force, and the material between them isn't sufficient to support the shear force developed in

between. Insufficient shear capacity led to a catastrophic shear failure.

(I've given you examples using beams, but columns undergo the same types of forces. Turn your head sideways!)

Think for a moment about our tree example, and about what would happen if you were to introduce a planar

weakness in the branch... say, if you were to sawcut around the entire branch at a point between you and the trunk,

leaving just a small bit of material to support your weight... and you can appreciate how potential sources of planar

discontinuity like construction joints are something to be respected and carefully planned. All that to say that you

don't want to place your construction joints in regions of your concrete members where the shear forces are

the highest.

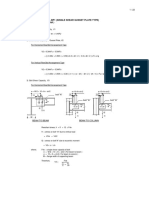

There's some guidance to that effect in the American Concrete Institute's Building Code Requirements for Structural

Concrete (ACI 318-08) and Commentary, in Section 6.4.

6.4.3 states that "Construction joints shall be so made and located as not to impair the strength of the structure.

Provision shall be made for transfer of shear and other forces through construction joints," and refers the reader to

Section 11.6.9, which includes some calculational considerations for your Engineer of Record to consider.

Speaking of the Engineer of Record, the commentary in the section also states that "For the integrity of the structure,

it is important that all construction joints be defined in construction documents and constructed as required. Any

deviations should be approved by the licensed design professional." They ought to have already provided an answer

for you, perhaps in the general notes and details.

So, the code to which you ought to adhere says to keep cold joints away from higher shear regions, but that truly, you

ought to examine the construction documents for direction on this, and if that doesn't yield answers, you ought to

request guidance from your Engineer of Record through an RFI.

You might also like

- Brazing - Fundamentals - 1Document7 pagesBrazing - Fundamentals - 1Sadashiw PatilNo ratings yet

- Reinforced Concrete Buildings: Behavior and DesignFrom EverandReinforced Concrete Buildings: Behavior and DesignRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- AUH Muncipality Guideline-2of 2Document43 pagesAUH Muncipality Guideline-2of 2cbecdmNo ratings yet

- Aashto T 313-12 BBRDocument22 pagesAashto T 313-12 BBRclint silNo ratings yet

- ASTM D945-16 Standard Test Methods For Rubber Properties in Compression or Shear (Mechanical Oscillograph)Document13 pagesASTM D945-16 Standard Test Methods For Rubber Properties in Compression or Shear (Mechanical Oscillograph)Andre Rodriguez SpirimNo ratings yet

- What Are The Basics of Structural AnalysisDocument8 pagesWhat Are The Basics of Structural AnalysisKutty MansoorNo ratings yet

- Narative ReportDocument2 pagesNarative ReportKarl Angelo CuellarNo ratings yet

- RCC Structures StairDocument31 pagesRCC Structures Staira_j_sanyal259No ratings yet

- CRSI The Designer's ResponsibilityDocument16 pagesCRSI The Designer's ResponsibilityAdam Jones100% (1)

- Tabinas - Ae3 - Activity 01Document22 pagesTabinas - Ae3 - Activity 01Lemuel Kim Cera TabinasNo ratings yet

- Advanced Design of Box GirdersDocument12 pagesAdvanced Design of Box Girderssujups100% (1)

- Steel Interchange: Modern Steel's Monthly Steel Interchange Is For You!Document2 pagesSteel Interchange: Modern Steel's Monthly Steel Interchange Is For You!Andres CasadoNo ratings yet

- Corrosion in TMT Rebar - ReportDocument37 pagesCorrosion in TMT Rebar - ReportRajbanul AkhondNo ratings yet

- Preface: Material in The Sense That It Is Fully Recyclable. PresentlyDocument3 pagesPreface: Material in The Sense That It Is Fully Recyclable. PresentlyKasia MazurNo ratings yet

- Question and Answers-AISCDocument15 pagesQuestion and Answers-AISCkiranNo ratings yet

- CivilDocument4 pagesCivilCamilaCMartinezHNo ratings yet

- Marine Structures Exam QuestionsDocument8 pagesMarine Structures Exam QuestionsAnonymous JSHUTpNo ratings yet

- Analysis On The Causes of Cracks in BridgesDocument14 pagesAnalysis On The Causes of Cracks in BridgesNguyễn Văn MinhNo ratings yet

- Construction JointDocument1 pageConstruction JointNumair Ahmad FarjanNo ratings yet

- Composite and Steel Construction CompendiumDocument3 pagesComposite and Steel Construction CompendiumΤε ΧνηNo ratings yet

- Modern Steel Construction's MonthlyDocument2 pagesModern Steel Construction's MonthlyapirakqNo ratings yet

- Some Mooted Questions in Reinforced Concrete Design American Society of Civil Engineers Transactions Paper No 1169 Volume LXX Dec 1910 2Document148 pagesSome Mooted Questions in Reinforced Concrete Design American Society of Civil Engineers Transactions Paper No 1169 Volume LXX Dec 1910 2Suleiman AldbeisNo ratings yet

- ScarryBNZSEEMarch2015Final CorrectedDocument24 pagesScarryBNZSEEMarch2015Final CorrectedJoão Paulo MendesNo ratings yet

- Axial Load Capacity of The ColumnDocument3 pagesAxial Load Capacity of The ColumnSadanand RaoNo ratings yet

- Design of Beams in Structural SteelDocument15 pagesDesign of Beams in Structural SteelMaqsood92% (13)

- Design of Steel Structure BeamDocument17 pagesDesign of Steel Structure BeamShahrah ManNo ratings yet

- SP ACI TORSION Overview CSGV 20200930Document30 pagesSP ACI TORSION Overview CSGV 20200930ahmedhatemlabibNo ratings yet

- c5099312 2808 473f 9c27 d7c851902a3f.handout10821ES10821CompositeBeamDesignExtensioninRobotStructuralAnalsisProfessional2016Document23 pagesc5099312 2808 473f 9c27 d7c851902a3f.handout10821ES10821CompositeBeamDesignExtensioninRobotStructuralAnalsisProfessional2016antonio111aNo ratings yet

- MSP PrestressDocument14 pagesMSP PrestressAmit MondalNo ratings yet

- Advanced Design of Concrete StructuresDocument115 pagesAdvanced Design of Concrete StructuresAb Rahman BaharNo ratings yet

- Modelling and Analysis of SteelDocument24 pagesModelling and Analysis of SteelJaleel ClaasenNo ratings yet

- PSD Test NotesDocument21 pagesPSD Test Notesmuhfil MuhfilNo ratings yet

- CIVE1151 Learning Guide 2012Document102 pagesCIVE1151 Learning Guide 2012Johnny Le100% (1)

- Design and Analysis of Moment Resisting Bases of Steel Column by Using IS:800-2007 Code and AISC-2010Document6 pagesDesign and Analysis of Moment Resisting Bases of Steel Column by Using IS:800-2007 Code and AISC-2010Manju BirjeNo ratings yet

- Steel Placement HandbookDocument20 pagesSteel Placement Handbookvarshneyrk@rediffmail.comNo ratings yet

- Torsion Design of Structural ConcreteDocument8 pagesTorsion Design of Structural ConcreteEduardo Núñez del Prado100% (1)

- Reinforced Cement Concrete DesignDocument5 pagesReinforced Cement Concrete DesignKimo KenoNo ratings yet

- Fasteners: The ESG ReportDocument4 pagesFasteners: The ESG ReportAnton SurviyantoNo ratings yet

- Numerical Analysis Group 10 (Full Report)Document11 pagesNumerical Analysis Group 10 (Full Report)BruhNo ratings yet

- Singly and Doubly Reinforced Beams FalngDocument67 pagesSingly and Doubly Reinforced Beams Falngmajedmorshed25No ratings yet

- Script Ni BumbayDocument10 pagesScript Ni BumbayHunter BravoNo ratings yet

- 2016 Msods BeeDocument19 pages2016 Msods Beemd ashraful alamNo ratings yet

- Beam (Structure) - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument3 pagesBeam (Structure) - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediadonodoni0008No ratings yet

- Essay About Reinforced Concrete Design: Rizal Technological UniversityDocument6 pagesEssay About Reinforced Concrete Design: Rizal Technological UniversityEjay EmpleoNo ratings yet

- Thermal BowingDocument22 pagesThermal BowingPedro Dominguez DominguezNo ratings yet

- Topic Reading 7 - Catalog ComponentsDocument28 pagesTopic Reading 7 - Catalog ComponentsDan StrutheNo ratings yet

- STEELDocument27 pagesSTEEL051Bipradeep ChandaNo ratings yet

- Lateral TorsionalBucklingOfSteelBeamDocument5 pagesLateral TorsionalBucklingOfSteelBeammhmdwalid95No ratings yet

- Seismic Performance of A 3D Full Scale HDocument27 pagesSeismic Performance of A 3D Full Scale HPravasNo ratings yet

- What Is Civil EngineeringDocument1 pageWhat Is Civil Engineeringafonso123susanaNo ratings yet

- Steel Strucsdftures 3 - Composite Structures - Lecture Notes Chapter 10.2Document22 pagesSteel Strucsdftures 3 - Composite Structures - Lecture Notes Chapter 10.2iSoK11No ratings yet

- Mechanical Engineering: Latest Mechanical Engineering Interview Questions - Placement Interview QuestionsDocument18 pagesMechanical Engineering: Latest Mechanical Engineering Interview Questions - Placement Interview QuestionsHardikDevdaNo ratings yet

- A Practical Method of Design of Concrete Pedestals For Columns For Anchor Rod Tension BreakoutDocument17 pagesA Practical Method of Design of Concrete Pedestals For Columns For Anchor Rod Tension Breakoutjohn blackNo ratings yet

- Approximate Structural AnalysisDocument10 pagesApproximate Structural Analysis6082838708No ratings yet

- Lecture 3 Short Columns Small Eccentricity-Analysis-1Document57 pagesLecture 3 Short Columns Small Eccentricity-Analysis-1Syed Agha Shah AliNo ratings yet

- Design BookDocument53 pagesDesign BookmollikaminNo ratings yet

- LEC06Document59 pagesLEC06Hamza KhawarNo ratings yet

- Limit States Design 9 ContentsDocument10 pagesLimit States Design 9 Contentssom_bs790% (4)

- The Tectonics of Structural Systems - An Architectural ApproachDocument52 pagesThe Tectonics of Structural Systems - An Architectural ApproachRoque R. RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Biaxial Bending of Steel Angle Section PDFDocument3 pagesBiaxial Bending of Steel Angle Section PDFImam NakhrowiNo ratings yet

- Kahn PostTensionedFloors 317pp, 95Document317 pagesKahn PostTensionedFloors 317pp, 95banyaszmonika2002No ratings yet

- What Are Buckling Restrained Braces?Document1 pageWhat Are Buckling Restrained Braces?Vikas MouryaNo ratings yet

- Some Mooted Questions in Reinforced Concrete Design American Society of Civil Engineers, Transactions, Paper No. 1169, Volume LXX, Dec. 1910From EverandSome Mooted Questions in Reinforced Concrete Design American Society of Civil Engineers, Transactions, Paper No. 1169, Volume LXX, Dec. 1910No ratings yet

- Daily Inspection Report: A. Observation On Quality of WorkDocument2 pagesDaily Inspection Report: A. Observation On Quality of WorkMarielNo ratings yet

- Sealbond Epoxy Test ReportDocument12 pagesSealbond Epoxy Test ReportMarielNo ratings yet

- Materials Delivery Receiving ReportDocument1 pageMaterials Delivery Receiving ReportMarielNo ratings yet

- Masonry Methodology 2 FinalDocument4 pagesMasonry Methodology 2 FinalMarielNo ratings yet

- Punchlist Form: Uma ResidencesDocument3 pagesPunchlist Form: Uma ResidencesMarielNo ratings yet

- PLF 086 PDFDocument2 pagesPLF 086 PDFMarielNo ratings yet

- KyleBauer2021 ThesisDocument86 pagesKyleBauer2021 ThesisAdnan NajemNo ratings yet

- Stresses in Beams: JU. Dr. Ibrahim Abu-AlshaikhDocument20 pagesStresses in Beams: JU. Dr. Ibrahim Abu-AlshaikhqusayNo ratings yet

- Reinforced Concrete DesignDocument5 pagesReinforced Concrete DesignselinaNo ratings yet

- Bar Bending Schedule Is v3.2 - Free Lite Version - EnglishDocument13 pagesBar Bending Schedule Is v3.2 - Free Lite Version - EnglishWening Sitdi AprilianNo ratings yet

- Reinforced Concrete Design-1 Course OutlineDocument3 pagesReinforced Concrete Design-1 Course OutlineHalf EngrNo ratings yet

- An Innovative Method of Teaching Structural Analysis and DesignDocument153 pagesAn Innovative Method of Teaching Structural Analysis and DesignmNo ratings yet

- Design and Analysis of Pre Engineered inDocument4 pagesDesign and Analysis of Pre Engineered inAnkur DubeyNo ratings yet

- 2 - Note de Calcule StructureDocument35 pages2 - Note de Calcule StructureJaouad Id BoubkerNo ratings yet

- Strength of Materials-II 2-2 Set-2 (A)Document13 pagesStrength of Materials-II 2-2 Set-2 (A)Sri DNo ratings yet

- Sa 1eeDocument124 pagesSa 1eeLakshmanan RamNo ratings yet

- TLO3 REINFORCING BARS NNNNDocument26 pagesTLO3 REINFORCING BARS NNNNBilly Joe Breakfast TalaugonNo ratings yet

- Cype 3d Calculations 60096Document48 pagesCype 3d Calculations 60096daniel8787No ratings yet

- Buckling Analysis by AbaqusDocument37 pagesBuckling Analysis by AbaqusGurram VinayNo ratings yet

- Lecture 03-Design of Doubly Reinforced Beam in FlexureDocument11 pagesLecture 03-Design of Doubly Reinforced Beam in FlexureOmer MehsudNo ratings yet

- Steel Penstocks - 4 Exposed PenstocksDocument40 pagesSteel Penstocks - 4 Exposed Penstocksjulio83% (6)

- 3 Structural Steel Fabrication3Document28 pages3 Structural Steel Fabrication3yradwohc100% (2)

- ECS478 CHAPTER 3-Flat SlabDocument40 pagesECS478 CHAPTER 3-Flat SlabAmron Abubakar0% (1)

- Shear Wall and Frame Interaction TerminologyDocument5 pagesShear Wall and Frame Interaction TerminologyGRD Journals100% (1)

- Ecs478 Chapter 2-TorsionDocument5 pagesEcs478 Chapter 2-TorsionMohdrafeNo ratings yet

- BP1 Bolt Connection CapacityDocument22 pagesBP1 Bolt Connection CapacityballisnothingNo ratings yet

- Bending StressDocument14 pagesBending StressDavid TurayNo ratings yet

- Session 3615 Models, Models, Models: The Use of Physical Models To Enhance The Structural Engineering ExperienceDocument9 pagesSession 3615 Models, Models, Models: The Use of Physical Models To Enhance The Structural Engineering ExperiencejmmnsantosNo ratings yet

- Iss36 Art2 - 3D Modelling of Train Induced Moving Loads On An EmbankmentDocument6 pagesIss36 Art2 - 3D Modelling of Train Induced Moving Loads On An EmbankmentbrowncasNo ratings yet

- Public Health Engineering Department (PHED) : Government of RajasthanDocument18 pagesPublic Health Engineering Department (PHED) : Government of RajasthanRajesh GangwalNo ratings yet

- SFD & BMDDocument99 pagesSFD & BMDChetanraj Patil100% (2)

- Assignment 2Document2 pagesAssignment 2johnmasefield50% (2)