Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Book Reviews: Volume 2, No. 1 - Spring 2012

Book Reviews: Volume 2, No. 1 - Spring 2012

Uploaded by

Gelci Andre ColliOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Book Reviews: Volume 2, No. 1 - Spring 2012

Book Reviews: Volume 2, No. 1 - Spring 2012

Uploaded by

Gelci Andre ColliCopyright:

Available Formats

BOOK REVIEWS

JOURNEY TO THE COMMON GOOD. By W. Brueggemann, Louisville, KY: Westminster John

Knox Press, 2010, 120 pp. $17.00.

As I write this review, the multi-state Mega Millions lottery boasts record numbers – $640 million to

be more or less exact. With a simple Google search you can read various accounts of the hopes and

dreams of people all across the fruited plain. What would you do with the money? Who would you give

some to? How much would be taken in taxes? Does a person tithe on $640 million? And so on. It’s an

interesting dream; it’s a spiritual dream. It’s a dream where problems might evaporate if only you held

the winning ticket. If you read Walter Brueggemann’s compelling book Journey to the Common Good,

you’ll see just how similar this dream is to the dreams of Pharaoh and Solomon, and how different it is

from those of Moses, Jeremiah, Isaiah, Paul, and John. The dreams of the former are predicated on the

expectation of need – or in Brueggemann’s words, of paucity – and rooted in the ideology of scarcity.

Pharaoh’s dreams reverberate with anxiety about having enough – and there is never enough. More

bricks, more control, more dominance, more acquisition, and more military to guard these things.

Solomon, portrayed by Brueggemann as a type of pharaoh, enacts policies which guard resources for the

empire – his empire – reinforcing stratification systems, clearly demarcating who counts as insider and

who counts as outsider, and preventing resources from reaching those who exist in the lower strata. One

thing jackpot lottery winnings do for a person – for Pharaoh, or for you or me – is to free him or her from

the demands of the neighborhood. $640 million quickly removes you from obligation to those around you

– just observe how many people plan to leave their present neighborhoods, jobs, and maybe even

churches if they win. Indeed, winning the lottery makes symbiotic relationship with the neighborhood

optional – you can resist it, ignore it, help it if you wish, or simply leave it. One thing is certain – with that

kind of coin, you don’t really need the neighborhood – you can live a gated life… with some pretty ornate

gates which block outsiders and undesirables from unauthorized entry.

But people of the scriptures can’t really avoid neighborhood – for the Bible is the story of

neighborhood, and the undesirable outsiders are precisely those to whom God freely gives of his

abundance and of whom he requires similar generosity. If love of God is love of neighbor, then to love

God’s kingdom is to love the neighborhood – the two are the same. For God loves the common good.

There is a story in my family about my Russian grandmother who grew up in a Polish orphanage during the

scarcity years following the Russian revolution. When a missionary, who had a soft spot for her, delivered

on his promise to bring her a treat upon his next visit (a large sweet roll), she, in an act of great generosity

passed the roll around to the other girls, and when it circled back to her there was nothing left. The roll

was given for the common good, and while I’m sure it didn’t break the cycle of poverty in that place, her

“act of abundance” demonstrated freedom from anxiety, and provided a powerful counternarrative in that

place of scarcity and need – breaking through “business as usual.” As Brueggemann writes, “It is precisely

an overwhelming, inexplicable act of generosity that breaks the grip of self-destructive anxiety concerning

scarcity” (p. 22). Accordingly, people of faith are called to live outside the nightmare of scarcity, rejecting

the expectation of paucity and the anxiety of that accompanies restless acquisition, and redirecting their

energies away from violence and guardedness to the common good.

Volume 2, No. 1• Spring 2012

Book Review: Journey to the common good 73

Journey to the Common Good traces a scriptural journey which begins with the “nightmare” scarcity

of Egypt, moves through the abundance and provision of God at Sinai, and concludes with an ethic of

common good in the neighborhood. The journey depicted in the scriptural narrative remains, more than

ever, our call and challenge yet today. Developing this challenge for our present context, Brueggemann

asks us to consider the ways in which abundance might overtake scarcity, generosity might break the cycle

of violence and exploitation, and shalom might replace aggressive anxiety. He beckons us to move away

from a world that continuously lives on Orange Alert. The book is nothing less than a call to a new world-

view – one which gives rather than takes, shares rather than guards, and empties self to fill the coffers of

the common good. The message of the book is rather the opposite of the lottery ethic described above.

Join me in a brief account of the journey:

The journey described in the book begins in Egypt where we encounter first Pharaoh, and then

Joseph. Pharaoh controls great wealth and innumerable resources. But he keeps them from the common

good, guarding them with military force fueled by great anxiety. Here in Egypt we find the well-known

Marxian theme of the two-class system – the workers, in contrast with those who control the means of

production amidst an organized system of exploitation. Brueggemann observes that when we read the

story of Joseph in the Egyptian narrative, we are quick to acknowledge God’s provision for his people,

through Joseph, but we overlook the subtext which draws to attention the “down and dirty” narrative of

economic transaction. For example, “Joseph, blessed Israelite that his is, is not only a shrewd dream

interpreter; he is, as well, an able administrator who commits himself to Pharaoh’s food policy. The royal

policy is to accomplish a food monopoly. In that ancient world as in any contemporary world, food is a

weapon and a tool of control” (p. 5). Brueggemann sees a Marxian parallel in the way Joseph, on behalf of

Pharaoh’s monopoly takes first the peasant’s money, then their cattle, and in the third year of the famine,

after their resources have been exhausted, appropriates their freedom in exchange for food. This,

explains Brueggemann is “policy rooted in nightmare” (p. 5) and “Slavery in the Old Testament happens

because the strong ones work a monopoly over the weak ones and eventually exercise control over their

bodies. Not only that; in the end the peasants, now become slaves, are grateful for their dependent

status” (p. 6). To borrow another well known Marxian concept, “false consciousness” reigns over the

oppressed, making them complicit in their own imprisonment.

Brueggemann draws considerable attention to the deep anxiety characterizing the “deteriorated

social situation” which has developed by the end of the book of Genesis, explaining that, “all parties in this

arrangement are beset by anxiety, the slaves because they are exploited, Pharaoh because he is fearful

and on guard” (p. 7). This anxiety drives the human actors in a scarcity system of exploitation and

oppression. Accordingly, “The narrative of the book of Exodus is organized into a great contest that is,

politically and theologically, an exhibit of the ongoing contest between the urge to control and the power

of emancipation that in ancient Israel is perennially linked to the God of the exodus” (p. 7). This leads to

the importance of imagination for the people of God. With their consciousness colonized by the

nightmare system of scarcity found in Egypt, when God provides manna for them in the wilderness, they

can “… hardly take in the alternative abundance given in divine generosity, the purpose of which was to

break the vicious cycle of anxiety about scarcity that in turn produced anger, fear, aggression, and, finally,

predatory violence” (p. 17). We see this in the Israelites’ reaction to divine abundance, wherein they try to

store up manna surpluses – hoarding now, in the face of expected scarcity in the future. They have little

imagination for anything else. The parallel with our own situation is unmistakable.

Volume 2, No. 1 • Spring 2012

74 Vos

Bread has great significance on the journey out Egypt. As they journey, the Israelites long for the

Egyptian bread of scarcity – bread baked of oppression and exploitation. In the wilderness, en route to

Sinai, God provides bread for his people – the bread of grace, leavened with generosity. Brueggemann

tells the reader that when the “bread of heaven” fell on the Israelites in the wilderness they asked “What

is it?” “The Hebrew for that question is man hu’, and so the bread is called ‘manna.’ The bread is named

‘What is it?’ which makes it a ‘wonder bread’ that fit none of their prevailing categories; they wondered

what it was” (p. 14). Consequently, “The wonder bread, as a gesture of divine grace, recharacterizes the

wilderness that Israel now discovered to be a place of viable life, made viable by the generous inclination

of YHWH” (p. 15). Bread has further significance in this exodus narrative from scarcity to abundance, from

dullness to imagination, from nightmare to dream, for over and over again in scripture it is the practice of

feasting – an act of abundance – that breaks the pattern of violence, oppression, expectation of paucity,

and need. “The [feasting] narrative attests that the world is not as we had imagined it, not as Pharaoh had

organized it. Adherence to patterns of scarcity produces a world in which the generosity of God is

nullified. The narratives attest otherwise and invite the listening community into an alternative mode of

existence, one that is ordered according to divine generosity” (p. 19). This alternative mode of existence is

embodied in the practice of neighborhood. Perhaps it is no accident that we are invited to the wedding

feast of the lamb – a feast which once and for all breaks through violence and anxiety, and which reorders

all of existence in an ethic of neighborliness.

And so, out of Egypt, sustained by wonder bread, they come to Sinai. Sinai represents a break with

the Egyptian worldview and system of oppression. Brueggemann explains that there was no common

good in Egypt, because people in a scarcity system cannot entertain the notion – they are too caught up in

anxiety. It is at Sinai that the people of God receive a lesson about the common good. The Ten

Commandments are nothing short of a counternarrative, a new social imaginary, a code of neighborliness.

But, entrenched as we are in the ethic of Egypt, we have too often used the Ten Commandments in ways

which sustain anxiety – enforcing a hierarchy of holiness – rather than using them to inform an ethic of

neighborly care. Brueggemann feels we must rethink the commandments, using them less as a means of

stratification (the good insiders versus the bad outsiders; the really holy versus the not-so-holy), a ranking

by observance, and more as a way of reimagining the world. From the Ten Commandments we learn that

neighbors are to be respected and protected… not exploited. To give two examples, the fourth

commandment, prohibiting work on the Sabbath is primarily about work stoppage – not worship. “Israel

learned from the fourth commandment that Sabbath rest is an alternative to aggressive anxiety… It is

about withdrawal from the anxiety system of Pharaoh, the refusal to let one’s life be defined by

production and consumption and the endless pursuit of private well-being. It is easy to imagine that in

Pharaoh’s system there never was Sabbath for anyone. Everyone was 24/7!” (p. 25, 26). Likewise, the

tenth commandment prohibiting covetousness proclaims that there is a limit to acquisitiveness.

Brueggemann explains that this commandment is not about petty acts of envy. “It is about predatory

practices and aggressive policies that make the little ones vulnerable to the ambitions of the big ones. In a

rapacious economic system, nobody’s house and nobody’s field and nobody’s wife and nobody’s oil are

safe from a stronger force” (p. 25). And so, the message we find in the Ten Commandments is, don’t envy,

don’t work all the time, direct your energies to the other and the common good… and all will be well.

Parts of Journey to the Common Good direct attention to the current situation in America.

Brueggemann sees the US as caught up in the very anxiety and military control which characterized Egypt,

and which was countered in Sinai. First and foremost, he sees the US as gripped by an entitled

The Journal for the Sociological Integration of Religion and Society

Book Review: Journey to the common good 75

consumerism. This drive for more and more – fueled by “aggressive advertising” and guarded by

consumer-driven militarism – leaves the country in a state of perpetual war. And war does not honor or

protect neighbors. Furthermore, entitled consumerism adds up to a culture of anxiety, where, in arguably

the richest country in the world, we live in continual fear of lack. And this fear, this ethic of scarcity, drives

us to lash out at would-be neighbors. Consider the words so many of us use to describe the poor

immigrants among us – not neighbors, but “illegals.” Energies we might otherwise have for neighborhood

and the common good are invested in televised sports (far removed from our own local communities) and

other media which further promote enchanted consumerism and the individualism (read “me” not

“neighbor”) on which it rests. Reflecting on this American ethic Brueggemann advises that the narrative

journey from Egypt to Sinai must be made over and over again. “More to the point, he comments that the

“… journey from anxious scarcity through miraculous abundance to a neighborly common good has been

peculiarly entrusted to the church and its allies” (p. 32). And about the present situation, “When the

church only echoes the world’s kingdom of scarcity, then it has failed in its vocation. But the faithful

church keeps at the task of living out a journey that points to the common good” (p. 32). For

Brueggemann, and to the central message of the book, “The Lord of Sinai intends that all economies

should be renovated for the common good” (p. 43). But it is all too easy to avoid the ethic of Sinai,

retreating back into the anxious world – for the world of Pharaoh is “enormously compelling.” We too

often counternarrate Sinai, rather than Egypt.

While the Exodus-Sinai-Deuteronomy narrative and its ethic of neighborliness hold “center stage” in

the Old Testament, there are challenges to it. One of the most significant of these comes from King

Solomon. Brueggemann writes, “In Solomon there is (a) a fresh enthrallment with Egypt and (b) a passion

for graded holiness” (p. 46). This was, for me, a compelling section of the book. Now sensitized to his

critique of how we read the Joseph/Egypt narrative, I see a similar tendency in how I read the chronicles of

Solomon – with an eye on God’s glory and holiness as it relates to temple design and construction, and

with tacit approval for his methods and vision. Brueggeman’s book opened my eyes to the economic and

social implications of Solomon’s rule – and he is not renovating for the common good. In a sociologically

compelling way Brueggemann deconstructs our class-tolerant understandings of Solomon and his

kingdom. Rather than acknowledging the three-chambered temple as simply “God’s design,” he sees it as

a replica of an imagined social order – one more than subtly reminiscent of the Egyptian empire. And the

focus is on hierarchy. “It is evident that Pharaoh’s notion of the common good – a hierarchical ordering

shaped like an Egyptian pyramid – reappeared in Jerusalem. – The echoes of Pharaoh are matched by a

graded holiness and by its consequent of a hierarchical ordering of society. Solomon, of course, is the

great temple builder in ancient Israel. We have, in the text, what amounts to a blueprint for his temple

that was an imitation of a generic type of building from his culture” (p. 47). In this, Brueggemann finds a

design that subverts the common good, while privileging hierarchy and prestige. When neighbors are

graded according to the social valuations of the powerful, neighborhood and the common good are

suppressed and degraded. Furthermore, “… Solomon’s temple was committed to the commoditization of

all social relationships so that we are able to see what is valued and consequently, who is valued” (p. 49).

And what we see is not neighbor, neighbor, neighbor, but rather gold, gold, gold. Brueggemann’s

indictment: “Solomon is the model in the Bible for a global perspective of the common good, a

perspective that smacks of privilege, entitlement, and exploitation, all in the name of the God of the three-

chambered temple, the three chambers that partition social life and social resources into the qualified, the

partially qualified, and the disqualified. It takes little critical imagination to see that Solomon’s

Volume 2, No. 1 • Spring 2012

76 Vos

perspective, which came to dominate urban Israel’s imagination, is an act of resistance against the

neighborly demands of Sinai, and an alternative to the possibilities of Mount Sinai” (p. 54). Solomon’s

design – for both temple architecture and the broader community – looks a lot like our own “upper,”

“middle,” and “lower” class structure. Gated communities, it seems, are nothing new.

But, he writes… Sinai still has its advocates – the poets, the prophets. These people live “outside

the box” and are rooted in Sinai. And so, in Jeremiah we find YHWH as subject, not object. In Isaiah we

encounter the God of assurance “… who is no longer an agent of settled sovereignty… This God speaks

against fear, the very fear by which the gods of the empire have kept all parties on orange alert. But now,

so goes the poetic utterance, everything has changed. Displaced peoples need no longer cringe; they can

stand tall, reimagine their lives in terms of miracle, and mobilize their energies for new possibility: Do not

fear, for I am with you…” (p. 95). In 1 Corinthians 1:31 the apostle Paul exhorts us to boast only in the Lord

of the neighborhood, and in 1 John we are reminded that love of God is love of neighbor. These and

others poets help us resist Egypt’s allures, and align us with the aims of another, better, more neighborly

world.

This is a helpful book. It can reignite in its reader the call to neighborhood and to the common

good. It can expand our understanding of what neighborliness means in a world of anxiety and orange

alert vigilance. It can remind us that bread is to be shared, and that the only way to break through

predatory violence, nightmare scarcity, and consuming anxiety is with inexplicable acts of generosity and

abundance.

But I must go… I need to turn down the television and tear up my lottery ticket.

Shalom.

M. Vos

Covenant College

The Journal for the Sociological Integration of Religion and Society

You might also like

- Twelve-Tribe Nations: Sacred Number and the Golden AgeFrom EverandTwelve-Tribe Nations: Sacred Number and the Golden AgeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Altruistic Personality: Rescuers Of Jews In Nazi EuropeFrom EverandAltruistic Personality: Rescuers Of Jews In Nazi EuropeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Judaism - Satanism, Sorcery and Black MagicDocument7 pagesJudaism - Satanism, Sorcery and Black Magickitty kat75% (4)

- Abstract Chapter 2 How Languages Are LearnedDocument4 pagesAbstract Chapter 2 How Languages Are LearnedDanielGonzálezZambranoNo ratings yet

- 10 Ways To Create Shareholder ValueDocument3 pages10 Ways To Create Shareholder ValuetahirNo ratings yet

- Implications For The Church As PropheticDocument15 pagesImplications For The Church As PropheticJames KirubakaranNo ratings yet

- Frankenstein ProblemDocument10 pagesFrankenstein ProblemJuan Angel CiarloNo ratings yet

- A Postcolonial Theory of Universal Humanity - Bessie Head's Ethics of The Margins Megan Cole PaustianDocument21 pagesA Postcolonial Theory of Universal Humanity - Bessie Head's Ethics of The Margins Megan Cole PaustianDavid Enrique ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Kristeva, Héréthique de L'amourDocument20 pagesKristeva, Héréthique de L'amourVassilis TsitsopoulosNo ratings yet

- WileyDocument15 pagesWileyMiri García JimenezNo ratings yet

- Basil Od Caeserea Speaks About Common Good When He Speaks Against Stockpilings Where The Rich Is Becoming Richer by Keeping The Materials and These Resources Are Alienated From The PoorDocument4 pagesBasil Od Caeserea Speaks About Common Good When He Speaks Against Stockpilings Where The Rich Is Becoming Richer by Keeping The Materials and These Resources Are Alienated From The Poorsargan kcNo ratings yet

- Celebration of SurpriseDocument20 pagesCelebration of SurpriseignNo ratings yet

- Filon On WomenDocument33 pagesFilon On WomenMartaNo ratings yet

- An Examination of The Masonic RitualDocument21 pagesAn Examination of The Masonic RitualgayatrixNo ratings yet

- A Journey in Imagination: Stories We Want Our Grandchildren to HearFrom EverandA Journey in Imagination: Stories We Want Our Grandchildren to HearNo ratings yet

- LESSON 7 - ReEDDocument2 pagesLESSON 7 - ReEDblahblahblahNo ratings yet

- A Definition of GnosticismDocument7 pagesA Definition of GnosticismZervas Georgios MariosNo ratings yet

- Symbolic: October 31-November 6Document10 pagesSymbolic: October 31-November 6Yrene Villanueva FernandezNo ratings yet

- Fallenangel Flyer For Business CardsDocument17 pagesFallenangel Flyer For Business Cardsapi-231612881No ratings yet

- The Necessity of Hope in Dystopian Times: A Critical ReflectionDocument31 pagesThe Necessity of Hope in Dystopian Times: A Critical ReflectionAntonis BalasopoulosNo ratings yet

- Prophecy & Dreams - Merging Imagination & Reality by Jarard K. A. ArnoldDocument9 pagesProphecy & Dreams - Merging Imagination & Reality by Jarard K. A. ArnoldJarardKennethNo ratings yet

- From Remembering To Re-Living and BackDocument4 pagesFrom Remembering To Re-Living and Backoutdash2No ratings yet

- Journey Back from Ixtlan: A Non-Ordinary Transformation Account of a Persian Enchanted SoulFrom EverandJourney Back from Ixtlan: A Non-Ordinary Transformation Account of a Persian Enchanted SoulNo ratings yet

- Job Mon AmiDocument8 pagesJob Mon AmiNicoleta AldeaNo ratings yet

- Colpron Possible WorldsDocument16 pagesColpron Possible WorldsGuilherme Meneses100% (1)

- Demetrio 1978Document23 pagesDemetrio 1978Ina BerayNo ratings yet

- As in the Heart, So in the Earth: Reversing the Desertification of the Soul and the SoilFrom EverandAs in the Heart, So in the Earth: Reversing the Desertification of the Soul and the SoilRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- We Survived the End of the World: Lessons from Native America on Apocalypse and HopeFrom EverandWe Survived the End of the World: Lessons from Native America on Apocalypse and HopeNo ratings yet

- Not in His Image (15th Anniversary Edition) - Preface and IntroDocument17 pagesNot in His Image (15th Anniversary Edition) - Preface and IntroChelsea Green PublishingNo ratings yet

- NADEL 1952 American - Anthropologist PDFDocument12 pagesNADEL 1952 American - Anthropologist PDFMoacir CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Betrayal Creation AnunnakiDocument37 pagesBetrayal Creation AnunnakiGia VietNo ratings yet

- Changeling Cross Genre Guidelines 1Document21 pagesChangeling Cross Genre Guidelines 1Frank de PaulaNo ratings yet

- Article1379687702 - Omar and DuttaDocument7 pagesArticle1379687702 - Omar and DuttaNirob MahmudNo ratings yet

- Witchcraft and Human Right Abuse Part 1Document6 pagesWitchcraft and Human Right Abuse Part 1David AsareNo ratings yet

- Kremer PDFDocument9 pagesKremer PDFAlin M. MateiNo ratings yet

- What Is This Thing Called Go(O)D?: That's Religion Explained Now Let's Talk Peace!From EverandWhat Is This Thing Called Go(O)D?: That's Religion Explained Now Let's Talk Peace!No ratings yet

- The Synagogue of Satan Dan Fournier Full ChapterDocument52 pagesThe Synagogue of Satan Dan Fournier Full Chapterpamela.shipp639100% (4)

- Intertextuality Contemporary Analysis PaperDocument5 pagesIntertextuality Contemporary Analysis Paperhoney arguellesNo ratings yet

- The Sacred Embrace of Jesus and Mary: The Sexual Mystery at the Heart of the Christian TraditionFrom EverandThe Sacred Embrace of Jesus and Mary: The Sexual Mystery at the Heart of the Christian TraditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Liminal and The Luminescent: Jungian Reflections on Ensouled Living Amid a Troubled EraFrom EverandThe Liminal and The Luminescent: Jungian Reflections on Ensouled Living Amid a Troubled EraRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Understandings of Justice in The New TestamentDocument3 pagesUnderstandings of Justice in The New TestamentIonel BuzatuNo ratings yet

- Woven Together: Faith and Justice for the Earth and the PoorFrom EverandWoven Together: Faith and Justice for the Earth and the PoorNo ratings yet

- Cain and AbelDocument7 pagesCain and AbelAran PatinkinNo ratings yet

- Gnostics Yahweh and Cosmic Mid East WarDocument23 pagesGnostics Yahweh and Cosmic Mid East WarpoyataNo ratings yet

- February 2000 - Patriarchy in The Lap of FeminismDocument4 pagesFebruary 2000 - Patriarchy in The Lap of FeminismcontatoNo ratings yet

- Reasons For Extraterrestrial Denial in Western SocietyDocument9 pagesReasons For Extraterrestrial Denial in Western Societymarczel00100% (1)

- Poverty and Wealth in The Orthodox Spirituality (With Special Reference To St. John Chrysostom)Document6 pagesPoverty and Wealth in The Orthodox Spirituality (With Special Reference To St. John Chrysostom)veres alexNo ratings yet

- Heaven Is GreenDocument19 pagesHeaven Is GreenZulfa RahmaNo ratings yet

- Girard, René. The Bible's Distinctiveness and The Gospel. The Girard Reader. Crossroad Publishing, 1996, Pp. 145-176.Document28 pagesGirard, René. The Bible's Distinctiveness and The Gospel. The Girard Reader. Crossroad Publishing, 1996, Pp. 145-176.LIghtYNo ratings yet

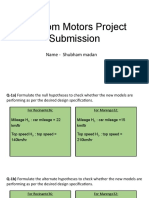

- Random Motors Project Submission: Name - Shubham MadanDocument10 pagesRandom Motors Project Submission: Name - Shubham MadanShubham MadanNo ratings yet

- Kami Export - Baheen Salami - Y6u15 Practice TestDocument2 pagesKami Export - Baheen Salami - Y6u15 Practice TestBaheen SalamiNo ratings yet

- FS360 - Life Partner SelectionDocument71 pagesFS360 - Life Partner Selectioneliza.dias100% (17)

- Feedback Mechanism InstrumentDocument2 pagesFeedback Mechanism InstrumentKing RickNo ratings yet

- Drugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravisDocument3 pagesDrugs To Avoid in Myasthenia GravispapitomalosoNo ratings yet

- Anti ManipulationDocument1 pageAnti ManipulationKasem AhmedNo ratings yet

- Sample of Equipment ProposalDocument2 pagesSample of Equipment ProposalJeasa Mae Jagonia MiñozaNo ratings yet

- Ujian Pembiasaan Bahasa Inggris Kelas 10&11Document2 pagesUjian Pembiasaan Bahasa Inggris Kelas 10&11Alfi HayyiNo ratings yet

- MSC CS&is SyllabusDocument42 pagesMSC CS&is SyllabusSamuel Gregory KurianNo ratings yet

- Kibor HistoryDocument3 pagesKibor HistorymaheenwarisNo ratings yet

- HCLDocument59 pagesHCLvibha_amy100% (1)

- Fesx 412B-30Document74 pagesFesx 412B-30Anonymous mGZOP8No ratings yet

- MSW-Social-Work SlabussDocument16 pagesMSW-Social-Work Slabussshivani chaturvediNo ratings yet

- HSPA - Network Optimization & Trouble Shooting v1.2Document15 pagesHSPA - Network Optimization & Trouble Shooting v1.2Ch_L_N_Murthy_273No ratings yet

- BS10 Lec - Writing A Research Proposal-IIDocument23 pagesBS10 Lec - Writing A Research Proposal-IIAhsan SheikhNo ratings yet

- MAT 171 Precalculus Algebra Section 9-7 Parametric EquationsDocument10 pagesMAT 171 Precalculus Algebra Section 9-7 Parametric EquationsZazliana IzattiNo ratings yet

- Sultans of Swing TabDocument5 pagesSultans of Swing TabNadiaNo ratings yet

- VLSI QnA - Interview Questions On Blocking and Nonblocking AssignmentsDocument3 pagesVLSI QnA - Interview Questions On Blocking and Nonblocking AssignmentsVIKRAMNo ratings yet

- Entrevista en El Britanico Basico 06Document5 pagesEntrevista en El Britanico Basico 06lena1231456No ratings yet

- Rhapsody Analysis and DiscourseDocument180 pagesRhapsody Analysis and DiscoursetbadcNo ratings yet

- 18 Making Math Meaningful For Students With Learning Problems Powerful Teaching Strategies That WorkDocument79 pages18 Making Math Meaningful For Students With Learning Problems Powerful Teaching Strategies That WorkFroilan TinduganNo ratings yet

- Bacillus Atrophaeus: (Atcc 9372™)Document2 pagesBacillus Atrophaeus: (Atcc 9372™)lenongnikaimutNo ratings yet

- Class II Subdivision Treatment With The Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device Vs Intermaxillary ElasticsDocument6 pagesClass II Subdivision Treatment With The Forsus Fatigue Resistant Device Vs Intermaxillary ElasticshemaadriNo ratings yet

- Suturepatterns 2 PDFDocument8 pagesSuturepatterns 2 PDFAsha RaniNo ratings yet

- 5 Anti - Inflammatory Drugs, Anti-Gout DrugsDocument15 pages5 Anti - Inflammatory Drugs, Anti-Gout DrugsAudrey Beatrice ReyesNo ratings yet

- Health Teaching Plan SampleDocument4 pagesHealth Teaching Plan SampleLicha Javier100% (1)

- MALABANAN-School-Based INSET-ReflectionDocument2 pagesMALABANAN-School-Based INSET-ReflectionCarmela BancaNo ratings yet

- Admin STRMDocument442 pagesAdmin STRMjeromenlNo ratings yet