Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Hard Truth About Telecommuting

The Hard Truth About Telecommuting

Uploaded by

Diego RottmanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Hard Truth About Telecommuting

The Hard Truth About Telecommuting

Uploaded by

Diego RottmanCopyright:

Available Formats

Telecommuting

The hard truth about telecommuting

Telecommuting has not permeated the American workplace, and

where it has become commonly used, it is not helpful in reducing

work-family conflicts; telecommuting appears, instead, to have

become instrumental in the general expansion of work hours,

facilitating workers’ needs for additional worktime beyond the

standard workweek and/or the ability of employers to increase or

intensify work demands among their salaried employees

T

Mary C. Noonan elecommuting, defined here as Evidence also reveals that an increasing num-

and

Jennifer L. Glass work tasks regularly performed ber of jobs in the American economy could be

at home, has achieved enough performed at home if employers were willing

traction in the American workplace to to allow employees to do so.5 Often, employees

merit intensive scrutiny, with 24 percent can perform jobs at home without supervision

of employed Americans reporting in recent in the “high-tech” sector, in the financial sector,

surveys that they work at least some hours and many in the communication sector that are

at home each week.1 The definitions of technology dependent. The obstacles or barriers

telecommuting are quite diverse. In this ar- to telecommuting seem to be more organiza-

ticle, we define telecommuters as employ- tional, stemming from the managers’ reluctance

ees who work regularly, but not exclusively, to give up direct supervisory control of workers

at home. In our definition, at-home work and from their fears of shirking among workers

activities do not need to be technologically who telecommute.6

mediated nor do telecommuters need a Where the impact of telecommuting has

formal arrangement with their employer to been empirically evaluated, it seems to boost

work at home. productivity, decrease absenteeism, and increase

Telecommuting is popular with policy retention.7 But can telecommuting live up to its

makers and activists, with proponents promise as an effective work-family policy that

pointing out the multiple ways in which helps employees meet their nonwork responsi-

telecommuting can cut commuting time bilities? To do so, telecommuting needs to be

and costs,2 reduce energy consumption both (1) widely used by workers who most need

and traffic congestion, and contribute to it and (2) instrumental in substituting hours at

worklife balance for those with caregiving home for hours onsite.8 Popular perceptions of

Mary C. Noonan is an Associate

Professor at the Department of

responsibilities.3 Changes in the structure telecommuting conjure images of workers re-

Sociology, The University of Iowa; of jobs that enable mothers to more effec- placing hours worked onsite with hours more

Jennifer L. Glass is the Barbara

Bush Regents Professor of Liberal tively compete in the workplace, such as comfortably worked at home, for mothers and

Arts at the Department of Sociol- telecommuting, may be needed to finally other care workers, especially. Yet, we know little

ogy and Population Research

Center, University of Texas at eliminate the gender gap in earnings and about how telecommuting in practice has be-

Austin. Email: mary-noonan-1@

uiowa.edu or jennifer-glass@ direct more earned income to children, come institutionalized in American workplaces.

austin.utexas.edu. both important public policy goals.4 Which workers telecommute? Is telecom-

38 Monthly Labor Review • June 2012

muting an effective strategy that lowers employees’ Methods

average hours worked onsite, or is telecommuting as-

sociated with longer average weekly work hours? To The NLSY is a national probability sample of 12,686 women

preview our results here, we find that telecommuting and men living in the United States and born between 1957

has not extensively permeated the American work- and 1964. The sample was interviewed annually from 1979 to

place, and where it has become commonly used, it is 1994 and biennially thereafter. In 1989, the NLSY began ask-

not unequivocally helpful in reducing work-family ing questions about the amount of time respondents worked at

conflicts. Instead, telecommuting appears to have be- home. To most closely match the years of the CPS supplements

come instrumental in the general expansion of work (described in the next paragraph), we pool 3 years from the

hours, facilitating workers’ needs for additional work- NLSY for our analysis: 1998, 2002, and 2004.

time beyond the standard workweek and/or the ability The CPS is a monthly survey of about 50,000 households

of employers to increase or intensify work demands representing the nation’s civilian noninstitutional population

among their salaried employees. 16 years of age and over. We use data from the special Work

We use two nationally representative data sources, Schedules and Work at Home supplement to the May 1997,

the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) 2001, and 2004 CPS, which asks workers whether they worked

1979 panel (hereafter, noted as the NLSY) and special at home as part of their job. The advantage of the CPS data is

supplements from the U.S. Census Current Population that, unlike the NLSY, it covers a broader age range of workers

Survey (CPS), to ascertain (1) trends over time in the so that we can compare a cohort similar in age with the NLSY,

use of telecommuting among employees in the civilian as well as a younger cohort of workers who might be more

labor force, (2) who telecommutes across the population technologically sophisticated and more amenable to telecom-

of employees, and (3) the relationship between telecom- muting. As such, we restrict the CPS sample to workers 22 to

muting and longer work hours among employees. These 40 years of age in 1997, 26 to 44 in 2001, and 29 to 47 in 2004.

two data sources provide information on telecommut- We further restrict our sample to individuals who worked

ing from the mid- to late 1990s through the mid-2000s, at least 20 hours per week in nonagricultural jobs and who

a period in which interest and capacity for telecom- provided valid data on all the key variables. Workers who

muting dramatically increased among U.S. businesses. were self-employed or worked exclusively at home are also

(Note that we did not use more recent data because the excluded from the sample. The final sample sizes are 16,298

Work Schedules and Work at Home May CPS supple- for the NLSY and 50,452 for the CPS.

ment was not fielded after 2004.) Our two main variables of interest are total hours worked

Together, these two datasets allow us to ascertain per week for the main job and total hours worked per week at

any general changes over time in the proportion of home for the main job.9 We use these two measures to cre-

employees who telecommute and the time intensity of ate two dummy variables indicating respondents who worked

their telecommuting at their main job. We further disag- overtime (i.e., more than 40, 50, and 60 hours per week) and

gregate telecommuting hours into those hours that are who telecommuted (i.e., worked at least 1 hour at home per

encapsulated within the 40-hour workweek (such that, week), respectively. Finally, for those respondents who tele-

regardless of the day or time worked, these telecommut- commuted, we disaggregate telecommuting hours into regu-

ing hours do not raise total work hours per week above lar telecommuting hours and overtime telecommuting hours. We

the statutory 40-hour threshold) and those hours that create these two variables by first creating a variable equal

extended the total number of hours worked per week to hours worked per week onsite for the main job. If total on-

beyond 40. By dividing telecommuting hours into these site work hours are less than 40, we categorize telecommut-

two categories, we are able to determine whether tele- ing hours that do not raise total work hours above 40 hours

commuting either replaces hours that otherwise would as regular telecommuting hours. If total onsite work hours

have been worked onsite during a standard 40-hour equal 40 or more, we categorize all telecommuting hours as

workweek or expands the workweek beyond the 40 or overtime telecommuting hours. We do not know the day or

more hours already worked onsite. time that onsite and/or telecommuting hours were worked;

In the following sections, we briefly describe our data instead, in our categorization, we assume that onsite hours

sources and measures, provide results from our analysis are “worked first” and telecommuting hours come second.

of the data, and summarize the lessons learned from Note that some workers reported both types of telecommut-

investigating the implementation of telecommuting in ing hours. For example, a worker reporting 45 total hours of

American workplaces. work per week, of which 10 are worked exclusively at home,

Monthly Labor Review • June 2012 39

Telecommuting

would yield 5 hours of regular telecommuting and 5 hours According to our NLSY and CPS estimates, approximately

of overtime telecommuting by our definitions. 10 percent of workers telecommuted in the mid-1990s

Control variables include occupation (measured with (chart 1). The rate of telecommuting increased slightly to

three categories: managerial/professional, sales, and 17 percent in the early 2000s and then remained constant

other), education (measured with four categories: less than to the mid-2000s.10 Our results suggest that telecommut-

high school, high school diploma, some college, and col- ing rates are not significantly different between younger

lege degree or higher), gender, race/ethnicity (measured and older cohorts of workers. Furthermore, no evidence

with three categories: other [White, Asian, etc.], Black, suggests that, among telecommuters, the number of hours

and Hispanic), marital status (measured with three catego- spent telecommuting has increased over time (results not

ries: never married, married, and separated/divorced/wid- shown). For the remainder of our analysis, we use a single

owed), parental status (dummy variable indicating whether CPS sample, not differentiated by age (i.e., the younger

a child 0 to 18 years old lives in household), and age. and older cohorts are pooled together).

Finally, we create synthetic age cohorts for the CPS data Next, we examine how telecommuting varies by educa-

based on the age range of the NLSY sample (32 to 40 years tional attainment, occupation, and parental status (chart 2).

old in 1997). We define the older cohort for the CPS as 32 to Here, we present data from the CPS only; results from the

40 years old in 1997, 36 to 44 years old in 2001, and 39 to NLSY are similar to the CPS results. CPS results show that

47 years old in 2004. The younger cohort from the CPS, by parents are no more likely than the population as a whole

contrast, incorporated workers who were 22 to 29 years old to telecommute, and mothers do not telecommute more

in 1997, maturing to 26 to 33 in 2001 and 29 to 36 in 2004. than fathers (about 17 percent for each group, results not

These two cohorts effectively cover the career stages in which shown). However, college-educated workers and those in

most earnings growth occurs, from the mid-20s to late 40s. managerial and professional occupations are significantly

To begin our analysis, we present trends over time in the more likely to telecommute than the population as a whole.

use of telecommuting for each sample as a whole and then Table 1 presents descriptive statistics on our key vari-

for various demographic groups. Next, we present descriptive ables by telecommuting status for both datasets, NLSY

statistics on all variables by telecommuting status for the CPS (1998, 2002, 2004) and CPS (1997, 2001, 2004). Most no-

sample and the NLSY sample. For each sample, we perform tably, telecommuters worked between 5 and 7 total hours

statistical tests to determine if differences exist between tele- more per week than nontelecommuters. Telecommuters

commuters and nontelecommuters. We pay special attention were significantly less likely to work a regular schedule

to the average hours of telecommuting among telecommuters (i.e., between 20 and 40 hours per week) and were more

and discuss how much telecommuting replaces onsite hours likely to work overtime, regardless of how overtime is de-

within the first 40 hours worked and how much telecom- fined (i.e., as working more than 40, 50, or 60 hours per

muting extends the workweek beyond 40 hours. Finally, we week).

estimate logistic regression models to predict the likelihood Among telecommuters, the average number of hours

of working overtime based on telecommuting status, includ- spent telecommuting each week is relatively modest, ap-

ing the control variables just described. Important to note is proximately 6 hours per week in both the CPS and NLSY

that neither the CPS nor the NLSY provides information on samples. But fully 67 percent (i.e., 4.17/6.20) of telecom-

whether or not the employee has an option to telecommute. muting hours in the NLSY and almost 50 percent (i.e.,

Our regression model assumes that all workers are able to 3.21/6.75) in the CPS occur in the overtime portion of

telecommute and that “telecommuting status” is exogenous the weekly hours distribution (see table 1, “Hours worked

to work hours. In reality, the ability to telecommute is likely by location”). This finding suggests that telecommuting is

a function of one’s occupational type and, within occupation, not being predominately used as a substitute for working

one’s performance. Both occupation and employee perfor- onsite during the first 40 hours worked per week.

mance are likely correlated with hours worked. We deal with Telecommuters are significantly more likely to have

this endogeneity problem by controlling for occupation in a college degree and to work in managerial/professional

our models; data on employee performance are not available. occupations compared with those who do not work at

home. Interestingly, parents are only slightly more pre-

Results dominant among telecommuters than nontelecommut-

ers. Telecommuters are less likely to be Black or Hispanic

To begin, we examine trends over time in telecommuting and less likely to be married compared with those not

for all workers and then for various demographic groups. telecommuting.

40 Monthly Labor Review • June 2012

Chart 1. Percentage of workers telecommuting over time, by cohort

Percent Percent

50 50

40 40

NLSY, older cohort

CPS, older cohort

30 CPS, younger cohort 30

20 20

10 10

0 0

1997/1998 2001/2002 2004

NOTES: Younger cohort is 22–29 years old in 1997. Older cohort is 32–40 years old in 1997.

SOURCES: National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) 1979 panel and special supplement from the U.S. Census Current Population

Survey (CPS).

Chart 2. Percentage of workers telecommuting over time, by education, occupation, and parental status

Percent Percent

50 50

All

College educated

40 40

Managerial/professional

Parent

30 30

20 20

10 10

0 0

1997 2001 2004

SOURCE: Special supplement from the U.S. Census Current Population Survey (CPS).

Monthly Labor Review • June 2012 41

Telecommuting

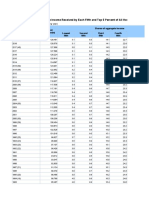

Table 1. Descriptive statistics by telecommuting status

NLSY (1998, 2002, 2004) CPS (1997, 2001, 2004)

Variable Telecommuting status Statistical Telecommuting status Statistical

test test

No Yes No Yes

Total hours worked per week 41.11 47.81 (1) 40.79 45.45 (1)

Hours worked per week (percent)

20–40 73 22 (1) 72 47 (1)

41 or more 27 78 (1) 28 53 (1)

51 or more 7 30 (1) 9 22

61 or more 2 7 (1) 2 6 (1)

Hours worked by location

Onsite 41.11 41.61 (2) 40.79 38.70 (1)

At home — 6.20 — — 6.75 —

Regular — 2.03 — — 3.54 —

Overtime — 4.17 — — 3.21 —

Occupation (percent)

Managerial/professional 26 70 (1) 27 71 (1)

Sales 7 12 (1) 10 14 (1)

Other 67 18 (1) 63 15 (1)

Education (percent)

Less than high school 8 2 (1) 11 1 (1)

High school diploma 47 17 (1) 35 11 (1)

Some college 25 20 (1) 30 20 (1)

College degree or higher 21 60 (1) 24 68 (1)

Gender (percent)

Male 51 54 (3) 55 53 (3)

Female 49 46 (3) 45 47 (3)

Race/ethnicity (percent)

Other (White, Asian, etc.) 78 88 (1) 73 88 (1)

Black 16 8 (1) 12 6 (1)

Hispanic 7 5 (1) 14 6 (1)

Marital status (percent)

Never married 15 11 (1) 26 20 (1)

Married 63 75 (1) 60 69 (1)

Separated/divorced/widowed 22 14 (1) 14 11 (1)

Parental status (percent)

Parent (1 = yes) 65 74 (1) 75 77 (1)

Age 40.24 40.54 ()

3

34.88 36.30 (1)

Number 14,100 2,198 — 43,188 7,264 —

1

p < .001. worked at least 1 hour onsite. In Current Population Survey (CPS) data,

2

p < .10. the parental status question is only asked in 2001 and 2004; statistics

3

p < .01. for this variable represent only these years.

NOTES: All statistics are weighted. Sample includes respondents who SOURCES: National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) 1979 panel

were not self-employed, worked at least 20 hours per week, and and special supplement from the U.S. Census CPS.

Table 2 presents the results of our logistic regression than 60 total hours per week. In each model, we control

models predicting the likelihood of working overtime for occupation, education, gender, race/ethnicity, marital

as a function of telecommuting status. We model three status, and age. Since the 2001 CPS did not collect data

versions of overtime: working more than 40 total hours on parental status, we do not include this variable in the

per week, more than 50 total hours per week, and more models. Because logistic regression coefficients do not

42 Monthly Labor Review • June 2012

Table 2. Logistic regression coefficients predicting working overtime

NLSY hours worked per week (1998, 2002, 2004) CPS hours worked per week (1997, 2001, 2004)

Variable 41 or more 51 or more 61 or more 41 or more 51 or more 61 or more

Telecommute status (1 = yes) 2.17 1.79 1.70 0.89 0.95 0.85

1

(.07) (.08)

1

(.16)

1 1

(.03) 1

(.04) (.08)

1

Occupation

Managerial/professional .39 .18 –.43 .36 .23 .11

1

(.06) (.09)

2

(.19)

3 1

(.03) 1

(.05) (.09)

Sales .42 .07 –.46 .46 .39 .17

1

(.09) (.13) (.26)

2 1

(.04) 1

(.06) (.10)

Other (4) (4) (4) (4) (4) (4)

Education

Less than high school –.17 .36 .31 –.28 –.17 –.04

2

(.10) (.15)

3

(.29) 1

(.05) 3

(.08) (.15)

High school diploma –.10 .30 .32 –.06 –.02 .05

(.06) (.10)

5

(.20)

2

(.03) (.05) (.09)

Some college –.19 .17 .17 –.06 –.05 .00

5

(.07) (.10)

2

(.21) 2

(.03) (.05) (.09)

College degree or higher (4) (4) (4) (4) (4) (4)

Gender

Female –1.32 –1.33 –1.40 –1.07 –1.20 –1.18

1

(.05) 1

(.07) 1

(.15) 1

(.02) 1

(.04) 1

(.07)

Male ()

4

()

4

() 4

()

4

()

4

(4)

Race/ethnicity

White (4) (4) (4) (4) (4) (4)

Black –.26 .01 .38 –.51 –.32 –.12

1

(.05) (.07) 1

(.13) 1

(.04) 1

(.07) (.12)

Hispanic –.21 –.02 –.01 –.46 –.42 –.42

1

(.06) (.08) (.15) 1

(.04) 1

(.07) 1

(.13)

Marital status

Never married –.18 –.04 .05 –.13 –.16 –.07

5

(.07) (.10) (.17) 1

(.03) 1

(.05) (.08)

Married (4) (4) (4) (4) (4) (4)

Separated/divorced/widowed .12 .20 .29 .06 –.04 .17

3

(.06) 3

(.08) 2

(.16) (.03) (.05) 2

(.09)

Age –.01 –.01 .02 .00 .00 –.01

(.01) (.01) (.02) (.01) (.01) (.01)

Constant –.14 –2.04 –4.51 –.44 –1.95 –3.04

(.27) 5

(.40) 5

(.79) 1

(.08) 1

(.12) 1

(.20)

Number 16,298 16,298 16,298 50,452 50,452 50,452

1

p < .001. NOTES: All statistics are weighted. Sample includes respondents who

2

p < .10. were not self-employed, worked at least 20 hours per week, and worked

3

p < .05. at least 1 hour onsite. Parental status not included in regression models

4

Omitted category. because it is not available in the 1997 Current Population Survey (CPS).

5

p < .01. SOURCES: National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) 1979 panel and

special supplement from the U.S. Census CPS.

Monthly Labor Review • June 2012 43

Telecommuting

show how much the probability of an event changes when week is relatively modest, around 6 hours per week in both

the predictors change, we translate the coefficients into the CPS and NLSY samples. No evidence suggests that the

predicted probabilities for four “ideal types” (cases) in table number of hours spent telecommuting is increasing over

3. For each case, we calculate the probability of working time.

overtime, assuming the individual is not a telecommuter Our descriptive results suggest that labor demand for

and again assuming the individual is a telecommuter. In work-family accommodation does not seem to propel

both datasets and in all models, the probability of work- the distribution of telecommuting hours. None of the

ing overtime is higher for telecommuters compared with expected relationships under such a scenario are present

nontelecommuters. The difference in the probability of in the data—parents of dependent children, for example,

working overtime between the two groups is largest when are no more likely to telecommute than the population

we define overtime as 41 hours or more, and smaller, but as a whole. Meanwhile, indicators that suggest a supply-

still significant, when overtime is defined as working 61 side explanation—such as occupational sector and work

hours or more. hours—are more strongly related to telecommuting

hours. As others have noted, the ability to work at home

OUR ANALYSIS OF TELECOMMUTING has yielded appears to be systematically related to authority and sta-

several surprising findings. Though more and more employ- tus in the workplace. Managerial and professional work-

ers claim to be offering flexible work options, the propor- ers are more likely than others to have the type of tasks

tion of workers who telecommute has been essentially flat and autonomous control of their work schedule necessary

over the mid-1990s to mid-2000s and is no larger among to perform work at home. While telecommuting may in

younger cohorts of workers than older cohorts. Moreover, theory be a solution to the dilemmas of combining work

the average number of hours spent telecommuting each and family, telecommuting in practice does not unequiv-

Table 3. Predicted probability of working overtime as a function of telecommuting status and other variables

[In percent]

NLSY hours worked per week CPS hours worked per week

Case (1998, 2002, 2004) (1997, 2001, 2004)

41 or more 51 or more 61 or more 41 or more 51 or more 61 or more

Case 1:

Man, college degree, managerial/professional

No telecommuting 49 10 1 47 16 4

Yes telecommuting 90 40 8 68 33 8

Difference 40 30 6 21 17 5

Case 2:

Man, high school diploma, other occupation

No telecommuting 37 11 3 37 13 4

Yes telecommuting 84 43 15 59 27 8

Difference 47 32 12 22 15 4

Case 3:

Woman, college degree, managerial/professional

No telecommuting 21 3 0 23 5 1

Yes telecommuting 70 15 2 42 13 3

Difference 49 12 2 19 7 2

Case 4:

Woman, high school diploma, other occupation

No telecommuting 14 3 1 17 4 1

Yes telecommuting 58 17 4 33 10 3

Difference 45 13 3 16 6 1

NOTES: In all predictions, the worker is White, married, and 40 years SOURCES: National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) 1979 panel and

old. Predictions based on estimated coefficients from table 2. special supplement from the U.S. Census Current Population Survey (CPS).

44 Monthly Labor Review • June 2012

ocally meet the needs of workers with significant caregiv- Future research employing longitudinal data should explore

ing responsibilities. whether employees increase their work hours after initia-

The most telling problem with telecommuting as a tion of telecommuting.

worklife solution is its strong relationship to long work Since telecommuting is intrinsically linked to infor-

hours and the “work devotion schema.”11 Fully 67 percent mation technologies that facilitate 24/7 communication

of telecommuting hours in the NLSY and almost 50 per- between clients, coworkers, and supervisors, telecommut-

cent in the CPS push respondents’ work hours above 40 per ing can potentially increase the penetration of work tasks

week and essentially occur as overtime work. This dynamic into home time. Bolstering this interpretation, the 2008

suggests that telecommuting in practice expands to meet Pew Networked Workers survey reports that the majority

workers’ needs for additional worktime beyond the stan- of wired workers report telecommuting technology has

dard workweek. As a strategy of resistance to longer work increased their overall work hours and that workers use

hours at the office, telecommuting appears to be somewhat technology, especially email, to perform work tasks even

successful in relocating those hours but not eliminating when sick or on vacation.12 Careful monitoring of this

them. A less sanguine interpretation is that the ability of blurred boundary between work and home time and the

employees to work at home may actually allow employers erosion of “normal working hours” in many professions

to raise expectations for work availability during evenings can help us understand the expansion of work hours over-

and weekends and foster longer workdays and workweeks. all among salaried workers.

NOTES

1

See American Time Use Survey—2010 Results, USDL-11-0919 how many hours did you actually work at your job?” To measure tele-

(U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, June 22, 2011). commuting, all three May CPS questionnaires have a lead-in question

asking, “As part of this job, do you do any of your work at home?” The

2

See Aleksandra Todorova, “Company Programs Help Employees

follow-up question varies slightly depending on which year of the CPS

Save on Gas,” Smart Money, May 29, 2008, http://www.smartmoney.

survey is being used. The May 1997 CPS questionnaire asks, “Last week,

com/spend/family-money/company-programs-help-employees-

of the ___ actual hours of work you did, approximately how many of

save-on-gas-23179.

them did you do at home for this job?” The May 2001/2004 CPS ques-

For review, see Ravi S. Gajendran and David A. Harrison, “The

3

tionnaire, on the other hand, asks, “When you work at home, how

Good, the Bad, and the Unknown about Telecommuting: Meta-Anal- many hours per week do you work at home for this job?” Furthermore,

ysis of Psychological Mediators and Individual Consequences,” Journal the questionnaire wording in the NLSY is slightly different than the

of Applied Psychology 92, no. 6 (2007), pp. 1,524–1,541. CPS. The NLSY question on hours worked (both at home and not at

4

See Nancy Folbre, Who Pays for the Kids? Gender and the Structure home) measures usual hours, not actual hours: “How many hours per

of Constraint (New York: Routledge, 1995), and see Joan Williams, Un- week do you usually work at this job?” and then, “How many hours per

bending Gender: Why Family and Work Conflict and What to Do about It week do you usually work at this job at home?” Studies comparing the

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2000). two measures of hours worked (actual versus usual) find that estimates

of actual hours worked are generally lower than estimates of usual

5

See Gartner, Inc., “Dataquest Insight: Teleworking, The Quiet hours worked (See Richard D. Williams, “Investigating Hours Worked

Revolution (2007 Update),” Gartner (May 14, 2007). Measurements,” 2004, Labor Market Trends 112, no. 2 (2004), pp. 71–

6

See Mary Blair-Loy, Competing Devotions: Career and Family 79. Our results suggest a similar pattern. Finally, “it varies” is a valid

among Women Executives (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, response option in the May 2001/2004 CPS question asking workers

2003). See Arlie Hochschild, The Time Bind (New York: Metropolitan for the number of hours worked at home. Approximately one-third

Books, 1995); See Pamela Stone, Opting Out? Why Women Really Quit of the telecommuters in each year selected “it varies” as their response.

Careers and Head Home (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, We imputed the mean telecommuting hours for those who replied “it

2007). varies” (6.40 for 2001 and 6.74 for 2004) and created a dummy variable

to indicate that the respondent’s value for telecommuting hours was

7

See Gajendran and Harrison, “The Good, the Bad, and the Un-

imputed. This indicator was included in the logistic regression models

known about Telecommuting,” pp. 1,524–1,541.

predicting overtime; the substantive results from these models are not

8

We use the term “onsite” to mean the location where workers labor sensitive to the inclusion of the indicator variable.

under the direction of their employer—an office, store, or other work- 10

Our telecommuting estimates from 2004 are lower than the

site. In the datasets we use for the analysis, we have measures of total

American Time Use Survey (ATUS) estimates for 2010: 17 percent ver-

hours worked and total hours worked at home. For simplicity, we refer

sus 24 percent. The most likely explanation for the difference is sample

to the “hours worked not at home” as hours worked “onsite.” We use

composition. We exclude workers who are self-employed and/or who

the terms “work at home” and “telecommuting” interchangeably.

work exclusively at home; the ATUS does not.

9

Differences exist in questionnaire wording both (1) over time in 11

Outlined by Blair-Loy, Competing Devotions.

the CPS and (2) between the CPS and NLSY that limit comparability of

work hour estimates across time periods and surveys. With all three 12

See Mary Madden and Sydney Jones, Networked Workers (Pew

CPS surveys (1997, 2001, and 2004), we measure total work hours with Research Center, September 24, 2008), http://pewinternet.org/Re-

a question referring to actual hours of work (pehract1). “Last week, ports/2008/Networked-Workers.aspx.

Monthly Labor Review • June 2012 45

You might also like

- Instant Download Ebook PDF Econometric Analysis of Panel Data 5th Edition by Badi H Baltagi PDF ScribdDocument41 pagesInstant Download Ebook PDF Econometric Analysis of Panel Data 5th Edition by Badi H Baltagi PDF Scribdlyn.pound175100% (47)

- (DAILY CALLER OBTAINED) - The State of The Working and Non-Working Man VFDocument40 pages(DAILY CALLER OBTAINED) - The State of The Working and Non-Working Man VFHenry Rodgers100% (1)

- Main Project On Work From HomeDocument53 pagesMain Project On Work From HomeMallavarapu Srikanth100% (3)

- Attitudes Toward Telecommuting Implications For Work-At-Home ProgramsDocument7 pagesAttitudes Toward Telecommuting Implications For Work-At-Home ProgramsKavya GopakumarNo ratings yet

- Informal Report Writ 200 TeleworkDocument12 pagesInformal Report Writ 200 Teleworkapi-340952703No ratings yet

- Telework and Health Effects Review: July 2017Document8 pagesTelework and Health Effects Review: July 2017ConstanzaSCNo ratings yet

- Telecommuting A Growing TrendDocument8 pagesTelecommuting A Growing TrendLTennNo ratings yet

- Telework and Time Use in The United States: Pabilonia - Sabrina@bls - Gov Victoria - Vernon@esc - EduDocument60 pagesTelework and Time Use in The United States: Pabilonia - Sabrina@bls - Gov Victoria - Vernon@esc - Edusafa haddadNo ratings yet

- Jermaine - TeleworkingDocument4 pagesJermaine - Teleworkingapi-3695734No ratings yet

- SWP 1907 20309545Document24 pagesSWP 1907 20309545api-564285765No ratings yet

- TRS6 Test 2 WritingDocument3 pagesTRS6 Test 2 WritingQuốc AnhNo ratings yet

- Freeing Work The Constraints of Location and Time: Lotte BailynDocument10 pagesFreeing Work The Constraints of Location and Time: Lotte BailynirvanNo ratings yet

- @annisuphere #Idea Sheet - Future of Remote WorkDocument12 pages@annisuphere #Idea Sheet - Future of Remote WorkninaNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 11 03067 v2Document17 pagesSustainability 11 03067 v2enlightening warriorNo ratings yet

- Telework The Advantages and Challenges o PDFDocument16 pagesTelework The Advantages and Challenges o PDFMinaNo ratings yet

- Telework The Advantages and ChallengesoDocument16 pagesTelework The Advantages and ChallengesoSania SaeedNo ratings yet

- Telework and Health Effects Review: ReviewsDocument7 pagesTelework and Health Effects Review: ReviewsCharlie MassoNo ratings yet

- At Home With Work: Understanding and Managing Remote and Hybrid WorkFrom EverandAt Home With Work: Understanding and Managing Remote and Hybrid WorkNo ratings yet

- Futureof Workplac E2020Document13 pagesFutureof Workplac E2020anupamNo ratings yet

- A306 Management Information Systems and The Networked Society AssignmentDocument4 pagesA306 Management Information Systems and The Networked Society Assignmentapi-3695734No ratings yet

- Organisational Behaviour WFH Research PaperDocument15 pagesOrganisational Behaviour WFH Research PaperBunnyNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Telecommuting Amidst The Pandemic On Metropolis and Province Areas: A Comparative StudyDocument48 pagesEffectiveness of Telecommuting Amidst The Pandemic On Metropolis and Province Areas: A Comparative StudyRon Michael CruzNo ratings yet

- Effect of Working From Home On Employees' Efficiency in The Public Sector Workplace in KentuckyDocument25 pagesEffect of Working From Home On Employees' Efficiency in The Public Sector Workplace in KentuckyjohnmorriscryptoNo ratings yet

- Hatayama Et Al. (2021) - Job's Amenability To Working From HomeDocument32 pagesHatayama Et Al. (2021) - Job's Amenability To Working From HomeLucas OrdoñezNo ratings yet

- By Serials Section, Dixson Library User On 20 April 2018Document54 pagesBy Serials Section, Dixson Library User On 20 April 2018irvanNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 IMPACT: Offices Will Find A New Purpose: Workforce Insights On Human PerformanceDocument12 pagesCOVID-19 IMPACT: Offices Will Find A New Purpose: Workforce Insights On Human PerformanceanupamNo ratings yet

- Our Proposal 1Document7 pagesOur Proposal 1Greham NicoleNo ratings yet

- Telework and Health Effects ReviewDocument8 pagesTelework and Health Effects ReviewKevin KCHNo ratings yet

- 5 Produtividade TelecomunicaçõesDocument9 pages5 Produtividade TelecomunicaçõesKarina FigueiredoNo ratings yet

- Impact of Remote and Hybrid WorkDocument7 pagesImpact of Remote and Hybrid Work23pba158ajiteshNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Teleworking On The Job Satisfaction, Employee Commitment and Productivity of The Employees During The COVID-19 PandemicDocument11 pagesThe Influence of Teleworking On The Job Satisfaction, Employee Commitment and Productivity of The Employees During The COVID-19 PandemicProme SahaNo ratings yet

- 2012 Executive DistributedWorkReportDocument13 pages2012 Executive DistributedWorkReportdesignedanddeliveredNo ratings yet

- Situational Leadership A Model For Leading TelecommutersDocument8 pagesSituational Leadership A Model For Leading TelecommutersmihkelnurmNo ratings yet

- Perceived Effects of Work From Office and Telecommuting On The Work Performance of AccountantsDocument16 pagesPerceived Effects of Work From Office and Telecommuting On The Work Performance of AccountantsMABALE Jeremy RancellNo ratings yet

- Guide Teleworking During Coronavirus PandemicDocument8 pagesGuide Teleworking During Coronavirus PandemicdanielNo ratings yet

- Emerging Issues in Organisational BehaviorDocument2 pagesEmerging Issues in Organisational Behaviorunwaz50% (2)

- TeleworkingDocument6 pagesTeleworkingКарина КолесникNo ratings yet

- ListeningDocument4 pagesListeningPham Nhat Linh (K18 HCM)No ratings yet

- EJMCM - Volume 7 - Issue 3 - Pages 4621-4627Document7 pagesEJMCM - Volume 7 - Issue 3 - Pages 4621-4627Erin Jocas Umandap100% (1)

- James T. Bond - How Can Employers Increase The Productivity (... ) (2006, Paper)Document17 pagesJames T. Bond - How Can Employers Increase The Productivity (... ) (2006, Paper)Roger KriegerNo ratings yet

- The Psychological Impact of Teleworking: Stress, Emotions and HealthDocument18 pagesThe Psychological Impact of Teleworking: Stress, Emotions and HealthKevin KCHNo ratings yet

- Gauging Perceived Benefits From Working From Home' As A Job BenefitDocument9 pagesGauging Perceived Benefits From Working From Home' As A Job BenefitAzrin ZulfakarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document21 pagesChapter 2MABALE Jeremy RancellNo ratings yet

- Working From Home: Opportunities and Risks: Briefing PaperDocument15 pagesWorking From Home: Opportunities and Risks: Briefing PaperYash PaulNo ratings yet

- Finding A New Balance Between Remote and in Office PresenceDocument11 pagesFinding A New Balance Between Remote and in Office PresenceKevan PerumalNo ratings yet

- Reimagine How and Where The World Will Work Post Covid 19Document26 pagesReimagine How and Where The World Will Work Post Covid 19anupamNo ratings yet

- Model Asst Part 2 TelecommtngDocument14 pagesModel Asst Part 2 TelecommtngSoorajKrishnanNo ratings yet

- Literature Review - 10282020Document13 pagesLiterature Review - 10282020kyroberts1985No ratings yet

- The Hopeful TelecommuterDocument5 pagesThe Hopeful TelecommuterAndrea MalazaNo ratings yet

- Chapter-3 Work Place Change 3.1 Employee Experience ManagementDocument4 pagesChapter-3 Work Place Change 3.1 Employee Experience ManagementJahid Hasan ShaonNo ratings yet

- WP FiveTrendsDocument15 pagesWP FiveTrendsMacarena CarreñoNo ratings yet

- Title 2Document2 pagesTitle 2pratheekshasnair002No ratings yet

- A Management Communication Strategy For Change PDFDocument15 pagesA Management Communication Strategy For Change PDFtibiavramNo ratings yet

- 2003 - The Psychological Impact of Teleworking, Stress, Emotions and HealthDocument16 pages2003 - The Psychological Impact of Teleworking, Stress, Emotions and HealthAlejandro CNo ratings yet

- Impact of Work From Home Model On The Productivity of Employees in The ITDocument10 pagesImpact of Work From Home Model On The Productivity of Employees in The ITNhân Trần TrọngNo ratings yet

- Telework: What Does It Mean For Management?: Viviane Illegems and Alain VerbekeDocument16 pagesTelework: What Does It Mean For Management?: Viviane Illegems and Alain VerbekeaaNo ratings yet

- The Economic Perspective of Remote Working Places: July 2020Document13 pagesThe Economic Perspective of Remote Working Places: July 2020Emine MerterNo ratings yet

- Am Ethical Argument Essay Final DraftDocument9 pagesAm Ethical Argument Essay Final Draftapi-653628343100% (1)

- The Hopeful Telecommuter Answers: 1. If I Were Jennifer, I Would First State My Background and The Work I Do ForDocument7 pagesThe Hopeful Telecommuter Answers: 1. If I Were Jennifer, I Would First State My Background and The Work I Do ForJamie DayagbilNo ratings yet

- Despotism on Demand: How Power Operates in the Flexible WorkplaceFrom EverandDespotism on Demand: How Power Operates in the Flexible WorkplaceNo ratings yet

- The 15-Second Commute: A Work-from-Home Guide for Telecommuters, Managers and EmployersFrom EverandThe 15-Second Commute: A Work-from-Home Guide for Telecommuters, Managers and EmployersNo ratings yet

- Overload: How Good Jobs Went Bad and What We Can Do about ItFrom EverandOverload: How Good Jobs Went Bad and What We Can Do about ItRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- Frequently Asked Questions For SEVP Stakeholders About COVID-19Document26 pagesFrequently Asked Questions For SEVP Stakeholders About COVID-19Diego RottmanNo ratings yet

- Captura 49Document1 pageCaptura 49Diego RottmanNo ratings yet

- SDFSDFDocument19 pagesSDFSDFDiego Rottman0% (1)

- README BmtaggerDocument4 pagesREADME BmtaggerDiego RottmanNo ratings yet

- Captura 48Document1 pageCaptura 48Diego RottmanNo ratings yet

- Captura 41Document1 pageCaptura 41Diego RottmanNo ratings yet

- Captura 45Document1 pageCaptura 45Diego RottmanNo ratings yet

- 7 Hidden Messages You May Have Missed in Company Logos Like,, andDocument2 pages7 Hidden Messages You May Have Missed in Company Logos Like,, andDiego RottmanNo ratings yet

- I Did It! I Did It! I Built A Pringles RingleDocument1 pageI Did It! I Did It! I Built A Pringles RingleDiego RottmanNo ratings yet

- Bscription Rate, Scribd Readers Can View and Read All Such Documents From Their Favorite Platforms Like Android, iOS and Windo WsDocument1 pageBscription Rate, Scribd Readers Can View and Read All Such Documents From Their Favorite Platforms Like Android, iOS and Windo WsDiego RottmanNo ratings yet

- ABC News/Ipsos Poll July 25-26Document4 pagesABC News/Ipsos Poll July 25-26Mark OsborneNo ratings yet

- Topline ABC - Ipsos Poll June 4 2022Document8 pagesTopline ABC - Ipsos Poll June 4 2022ABC News PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Statistics Chapter 2-Part 1Document5 pagesDescriptive Statistics Chapter 2-Part 1aminlaiba2000No ratings yet

- UnemploymentDocument4 pagesUnemploymentDhruv ThakkarNo ratings yet

- TobaccoDocument274 pagesTobaccoPat ChompumingNo ratings yet

- Chap 2Document86 pagesChap 2Imen Kenza ChouaiebNo ratings yet

- ABC News/Ipsos Poll Aug 30Document6 pagesABC News/Ipsos Poll Aug 30ABC News Politics100% (1)

- How Does A Federal Minimum Wage Hike Affect Aggregate Household Spending?Document4 pagesHow Does A Federal Minimum Wage Hike Affect Aggregate Household Spending?Steven HansenNo ratings yet

- Economics 4Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFDocument31 pagesEconomics 4Th Edition Krugman Solutions Manual Full Chapter PDFrick.cain697100% (12)

- EmpsitDocument42 pagesEmpsitPrathamesh GhargeNo ratings yet

- U A D S S A: Ses of Dministrative Ata at The Ocial Ecurity DministrationDocument10 pagesU A D S S A: Ses of Dministrative Ata at The Ocial Ecurity DministrationZulhan Andika AsyrafNo ratings yet

- ABC News/Ipsos Poll May 7 2020Document5 pagesABC News/Ipsos Poll May 7 2020ABC News PoliticsNo ratings yet

- ABC News/Ipsos Poll 11.18Document4 pagesABC News/Ipsos Poll 11.18ABC News Politics100% (1)

- Refugee Report DraftDocument55 pagesRefugee Report DraftTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- openAI (Jobs)Document36 pagesopenAI (Jobs)rationalthinkerddNo ratings yet

- ABC/Ipsos Poll 3.20.20Document4 pagesABC/Ipsos Poll 3.20.20ABC News PoliticsNo ratings yet

- ABC News/Ipsos Poll Sept 4Document5 pagesABC News/Ipsos Poll Sept 4ABC News PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Topline ABC - Ipsos Poll April 7 2023Document6 pagesTopline ABC - Ipsos Poll April 7 2023ABC News PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Econ 230A: Public Economics Lecture: Introduction: Hilary HoynesDocument28 pagesEcon 230A: Public Economics Lecture: Introduction: Hilary HoynesPres Asociatie3kNo ratings yet

- David Card - The Impact of The Mariel Boatlift On The Miami Labor MarketDocument14 pagesDavid Card - The Impact of The Mariel Boatlift On The Miami Labor MarketnappynapNo ratings yet

- Texas Workforce: Texas Workforce Commission's Labor Market & Career InformationDocument54 pagesTexas Workforce: Texas Workforce Commission's Labor Market & Career InformationLisa FabianNo ratings yet

- Mariel ImpactDocument14 pagesMariel ImpactDiana Valenzuela ArayaNo ratings yet

- A Message From The Director of The U.S. Office of Personnel ManagementDocument82 pagesA Message From The Director of The U.S. Office of Personnel ManagementChristopher DorobekNo ratings yet

- Poverty in The United States: 2022: Current Population ReportsDocument67 pagesPoverty in The United States: 2022: Current Population ReportsVeronica SilveriNo ratings yet

- Table H-2. Share of Aggregate Income Received by Each Fifth and Top 5 Percent of All Households: 1967 To 2019Document4 pagesTable H-2. Share of Aggregate Income Received by Each Fifth and Top 5 Percent of All Households: 1967 To 2019DavidNo ratings yet

- Blanchard Macro8e PPT 07Document31 pagesBlanchard Macro8e PPT 073456123No ratings yet

- Human Capital Investment .PPT at Bec DomsDocument34 pagesHuman Capital Investment .PPT at Bec DomsBabasab Patil (Karrisatte)No ratings yet

- Quantitative Research TitleDocument5 pagesQuantitative Research TitleEstela Benegildo80% (10)