Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adelman and Taylor

Adelman and Taylor

Uploaded by

Jakaria AhmedCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- When The World Goes Quiet - Gian SardarDocument283 pagesWhen The World Goes Quiet - Gian Sardarmengchhoungleang.cbvhNo ratings yet

- ASL Informative Essay)Document2 pagesASL Informative Essay)Hayden Miller50% (2)

- Fullan Change ModelDocument13 pagesFullan Change Modelct hajar turemenNo ratings yet

- Makeup Service ContractDocument2 pagesMakeup Service ContractMary V. Warner-ReeseNo ratings yet

- Implementing The Designed Curriculum As A Change ProcessDocument4 pagesImplementing The Designed Curriculum As A Change ProcessStarNo ratings yet

- Curriculum ImplementationDocument36 pagesCurriculum ImplementationChelle Maale78% (9)

- Managing Organizational Change PDFDocument13 pagesManaging Organizational Change PDFvaneknekNo ratings yet

- Sources of Change & Innovation Types of Change Forms of Change Strategies Models Planning and ImplementationDocument6 pagesSources of Change & Innovation Types of Change Forms of Change Strategies Models Planning and ImplementationJhoijoi BautistaNo ratings yet

- Walmart Live Well - Report An Absence - How To Guide (EN) - Nov 2019Document7 pagesWalmart Live Well - Report An Absence - How To Guide (EN) - Nov 2019Jakaria Ahmed0% (2)

- Untitled 3Document2 pagesUntitled 3Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Systemic Change For School Improvement: Howard S. Adelman and Linda TaylorDocument2 pagesSystemic Change For School Improvement: Howard S. Adelman and Linda TaylorJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Section 7 Managing Change For Organizational Improvement: E838 Effective Leadership and Management in EducationDocument12 pagesSection 7 Managing Change For Organizational Improvement: E838 Effective Leadership and Management in EducationRose DumayacNo ratings yet

- Untitled 6Document2 pagesUntitled 6Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Adelman and TaylorDocument2 pagesAdelman and TaylorJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Achieving Sustainable Systemic Change: An Integrated Model of Educational TransformationDocument15 pagesAchieving Sustainable Systemic Change: An Integrated Model of Educational Transformationd1w2d1w2No ratings yet

- 3 Stages of Change ProcessDocument3 pages3 Stages of Change ProcessAsmadera Mat EsaNo ratings yet

- The School Improvement and Transformation SystemDocument13 pagesThe School Improvement and Transformation SystemJewel Alayon CondinoNo ratings yet

- Staff (E.g., Organization Facilitators) - As A Group, Such District Staff HasDocument2 pagesStaff (E.g., Organization Facilitators) - As A Group, Such District Staff HasJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Connell & Klem - Theory of Change & Ed ReformDocument29 pagesConnell & Klem - Theory of Change & Ed ReformLucía GamboaNo ratings yet

- Increasing Student Success in STEMDocument10 pagesIncreasing Student Success in STEMkimshady26No ratings yet

- Innovation and Change in EducationDocument14 pagesInnovation and Change in EducationDidik Agus TNo ratings yet

- Article SummaryDocument19 pagesArticle SummarySaras VathyNo ratings yet

- Strategies in Facilitating Systemic ChangeDocument2 pagesStrategies in Facilitating Systemic ChangeJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- StanleyG 06 SustainableLeadershipDocument10 pagesStanleyG 06 SustainableLeadershipIngi Abdel Aziz SragNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Related To Change ManagementDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Related To Change Managementgz8jpg31100% (1)

- Module 4 - Curriculum PlanningDocument12 pagesModule 4 - Curriculum PlanningMichelle MahingqueNo ratings yet

- School Organization and ChangeDocument24 pagesSchool Organization and ChangeSamuelNo ratings yet

- The School System Transformation SST Protocol 136Document16 pagesThe School System Transformation SST Protocol 136Paula CostaNo ratings yet

- 8 Forces For Leaders of ChangeDocument6 pages8 Forces For Leaders of Changeapi-298600917No ratings yet

- Educational ChangeDocument43 pagesEducational Changeveena9876100% (1)

- Untitled 11Document2 pagesUntitled 11Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- oRzqOS EJ892382Document24 pagesoRzqOS EJ892382sretalNo ratings yet

- Curriculum ChangeDocument35 pagesCurriculum ChangeFifi AinNo ratings yet

- Untitled 12Document2 pagesUntitled 12Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in School Management-Education 4.0Document83 pagesCurrent Trends in School Management-Education 4.0Daisy Joy LacandazoNo ratings yet

- Edited New PresentationDocument6 pagesEdited New PresentationIgnitius DhihwaNo ratings yet

- CDE 802 Innovation and Change in CurriculumDocument19 pagesCDE 802 Innovation and Change in CurriculumObinnaNo ratings yet

- EDUC 205 LESSON No. 1 (LM # 4 Final)Document8 pagesEDUC 205 LESSON No. 1 (LM # 4 Final)Ellarence RafaelNo ratings yet

- Cabral-Proposed Dissertation Title 2Document21 pagesCabral-Proposed Dissertation Title 2Abby- Gail14 CabralNo ratings yet

- Christopher Day, Judyth Sachs - International Handbook On The Continuing Professional Development of Teachers (2005, Open Univ PR)Document31 pagesChristopher Day, Judyth Sachs - International Handbook On The Continuing Professional Development of Teachers (2005, Open Univ PR)Patricia Rejane Feitosa IbiapinaNo ratings yet

- OU Resilience 2017 Paper Hilst SmidDocument19 pagesOU Resilience 2017 Paper Hilst SmidGerhard SmidNo ratings yet

- Leading System TransformationDocument12 pagesLeading System TransformationMatias Reviriego RomeroNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Impl-WPS OfficeDocument6 pagesChapter 3 - Impl-WPS Officemrasonable1027No ratings yet

- Untitled 5Document2 pagesUntitled 5Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Change Theory A Force For School ImprovementDocument15 pagesChange Theory A Force For School Improvementapi-275150179No ratings yet

- Educational Policies On TechnologyDocument3 pagesEducational Policies On TechnologyRodgers OmondiNo ratings yet

- SHARED WEEK 8. Insights Into The Causes and Processes of Educational Change Implementation and ContinuationDocument4 pagesSHARED WEEK 8. Insights Into The Causes and Processes of Educational Change Implementation and ContinuationainhoaferrermartinezNo ratings yet

- Power From Implies Ability To Resist The Power of Others (Riger, 1993) - enDocument2 pagesPower From Implies Ability To Resist The Power of Others (Riger, 1993) - enJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Change ManagementDocument14 pagesChange ManagementshahidNo ratings yet

- Understanding Teacher Change Revisiting The Concerns Based Adoption Model PDFDocument38 pagesUnderstanding Teacher Change Revisiting The Concerns Based Adoption Model PDFPhoebe THian Pik HangNo ratings yet

- Article p946 PDFDocument20 pagesArticle p946 PDFSary MamNo ratings yet

- Key FacetsDocument2 pagesKey FacetsJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Ed. Change ManagementDocument44 pagesEd. Change Managementdeutza_hotNo ratings yet

- 6080-Aaa 5 - Katie Page 1Document11 pages6080-Aaa 5 - Katie Page 1api-583359791No ratings yet

- Format in Written ReportDocument4 pagesFormat in Written ReportPeter O. GoyenaNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Journal of Educational Management: Managing Change in Educational Organization: A ConceptualDocument13 pagesMalaysian Journal of Educational Management: Managing Change in Educational Organization: A ConceptualbavaNo ratings yet

- 2 Focus of Organization ChangeDocument28 pages2 Focus of Organization Changesxcsh88100% (2)

- 教育改革的十个步骤:实现变革Document262 pages教育改革的十个步骤:实现变革wuyugangNo ratings yet

- Implementing Change in EducationDocument4 pagesImplementing Change in EducationrobbagachieNo ratings yet

- Modeling Systems Thinking in Action Among Higher Education Leaders With Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision MakingDocument20 pagesModeling Systems Thinking in Action Among Higher Education Leaders With Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision MakingKhoirul MunirNo ratings yet

- Is Change Management Obsolete?: SciencedirectDocument11 pagesIs Change Management Obsolete?: Sciencedirectahmedanoof7879No ratings yet

- Leaders in Succession: Rotation in International School AdministrationFrom EverandLeaders in Succession: Rotation in International School AdministrationRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Succession Planning and Management: A Guide to Organizational Systems and PracticesFrom EverandSuccession Planning and Management: A Guide to Organizational Systems and PracticesNo ratings yet

- How Does The Manitoba Islamic Mortgage Compare With A Conventional Mortgage?Document1 pageHow Does The Manitoba Islamic Mortgage Compare With A Conventional Mortgage?Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 11Document2 pagesUntitled 11Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 5Document2 pagesUntitled 5Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 12Document2 pagesUntitled 12Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Adelman and TaylorDocument2 pagesAdelman and TaylorJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Strategies in Facilitating Systemic ChangeDocument2 pagesStrategies in Facilitating Systemic ChangeJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Staff (E.g., Organization Facilitators) - As A Group, Such District Staff HasDocument2 pagesStaff (E.g., Organization Facilitators) - As A Group, Such District Staff HasJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Power From Implies Ability To Resist The Power of Others (Riger, 1993) - enDocument2 pagesPower From Implies Ability To Resist The Power of Others (Riger, 1993) - enJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 6Document2 pagesUntitled 6Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Key FacetsDocument2 pagesKey FacetsJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Systemic Change For School Improvement: Howard S. Adelman and Linda TaylorDocument2 pagesSystemic Change For School Improvement: Howard S. Adelman and Linda TaylorJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 3Document2 pagesUntitled 3Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research QualitativeDocument13 pagesQualitative Research QualitativeJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Greater Toronto Area (GTA) Teachers' Perspectives On Teacher EfficacyDocument11 pagesGreater Toronto Area (GTA) Teachers' Perspectives On Teacher EfficacyJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

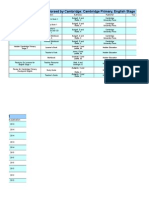

- Cambridge Secondary BooklistDocument5 pagesCambridge Secondary BooklistJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Understanding Lesson Planning - GlossaryDocument1 pageUnderstanding Lesson Planning - GlossaryJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- ParagraphDocument4 pagesParagraphJakaria Ahmed100% (1)

- Marketing: From Evolution To PresentDocument3 pagesMarketing: From Evolution To PresentJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Student CalendarDocument12 pagesStudent CalendarJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Primary BooklistDocument22 pagesCambridge Primary BooklistJakaria Ahmed100% (1)

- Short Term Plan Templete: Pupil(s) / Group: Class Level: Class Teacher: DAY Sunday Monday StrandDocument4 pagesShort Term Plan Templete: Pupil(s) / Group: Class Level: Class Teacher: DAY Sunday Monday StrandJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- ABC Analysis in The Hospitality Sector: A Case Study: January 2017Document4 pagesABC Analysis in The Hospitality Sector: A Case Study: January 2017Sarello AssenavNo ratings yet

- Soal UjianDocument3 pagesSoal UjianNuryeri Efrita HarahapNo ratings yet

- 3 Customer ServiceDocument12 pages3 Customer Serviceharsh2rcokNo ratings yet

- Calif. Wildfire Surges To Nearly 200 Square Miles and Spreads Into Yosemite National ParkDocument3 pagesCalif. Wildfire Surges To Nearly 200 Square Miles and Spreads Into Yosemite National ParkCynthia TingNo ratings yet

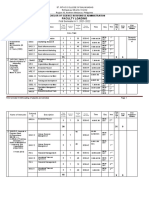

- BSBA FINAL LOADING For BOT 2021-2022 1st SEMESTERDocument5 pagesBSBA FINAL LOADING For BOT 2021-2022 1st SEMESTERMaureen GalendezNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Culture5Document43 pagesAspects of Culture5Almira Bea Eramela Paguagan100% (1)

- The Art of Empathy Translation PDFDocument90 pagesThe Art of Empathy Translation PDFusrjpfptNo ratings yet

- Department of Defense - Joint Vision 2020 PDFDocument40 pagesDepartment of Defense - Joint Vision 2020 PDFPense Vie Sauvage100% (1)

- Elements of A Negligence Claim: Car Accidents Slip and FallDocument19 pagesElements of A Negligence Claim: Car Accidents Slip and FallOlu FemiNo ratings yet

- Book Promotion AssignmentDocument5 pagesBook Promotion Assignmentapi-551846304No ratings yet

- The Absurd in Endgame and The MetamorphosisDocument7 pagesThe Absurd in Endgame and The MetamorphosisMubashra RehmaniNo ratings yet

- Affidavit Sarah JaneDocument2 pagesAffidavit Sarah JaneJholo AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- "Untitled Austin Project": Crown Venice Productions, LLC ReimbursementsDocument2 pages"Untitled Austin Project": Crown Venice Productions, LLC ReimbursementsButtNo ratings yet

- PPP Frame WorkDocument10 pagesPPP Frame WorkchelimilNo ratings yet

- 42 Items Q and ADocument2 pages42 Items Q and AJoy NavalesNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Stock Market With Commodity Market in MalaysiaDocument20 pagesRelationship Between Stock Market With Commodity Market in MalaysiaOmar LuqmanNo ratings yet

- 2022 JOAP Remedial Law Mock Bar ExaminationDocument14 pages2022 JOAP Remedial Law Mock Bar ExaminationVincent Jave GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Grade5 StudentEditionDocument267 pagesGrade5 StudentEditionsyed hassanNo ratings yet

- Symbiosis Law School, Pune: SUBJECT - Media and Entertainment Law Alternative Internal AssessmentDocument15 pagesSymbiosis Law School, Pune: SUBJECT - Media and Entertainment Law Alternative Internal AssessmentAditya KedariNo ratings yet

- Lista 5095568 Planilha Formandos Pronta para SEIDocument193 pagesLista 5095568 Planilha Formandos Pronta para SEIIgor BarretoNo ratings yet

- 61 Journal of Chinese Literature and CultureDocument15 pages61 Journal of Chinese Literature and CultureYvonne ChewNo ratings yet

- SBN-1421: Department of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) Act of 2017Document8 pagesSBN-1421: Department of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) Act of 2017Ralph RectoNo ratings yet

- Basketball Basic RulesDocument10 pagesBasketball Basic RulesMohan ArumugavallalNo ratings yet

- Report of The Film Fact Finding CommitteDocument435 pagesReport of The Film Fact Finding CommitteOmar ZakirNo ratings yet

- Unanswered PrayersDocument3 pagesUnanswered Prayersdeep54321No ratings yet

- Sps. Ong vs. Roban LendingDocument2 pagesSps. Ong vs. Roban LendingPraisah Marjorey PicotNo ratings yet

- Codex HarlequinsDocument10 pagesCodex HarlequinstommythekillerNo ratings yet

Adelman and Taylor

Adelman and Taylor

Uploaded by

Jakaria AhmedOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adelman and Taylor

Adelman and Taylor

Uploaded by

Jakaria AhmedCopyright:

Available Formats

56 ADELMAN AND TAYLOR

does not include major initiatives to delineate and test models for wide-

spread replication of education reforms. Little attention has been paid to

the complexities of large-scale diffusion. Leadership training for

policymakers and education administrators has given short shrift to the

topic of scale-up processes and problems (Duffy, 2005; Elmore, 2003, 2004;

Fullan, 2005; Glennan, Bodilly, Galegher, & Kerr, 2004; Hargreaves & Fink,

2000; Thomas, 2002).

School improvement obviously needs to begin with a clear framework

and map for what changes are to be made. It should be equally obvious

that there must be a clear framework and map for how to get from “here to

there,” especially when the improvements require significant systemic

change. And, in both cases, there is a need for a strong science base, leader-

ship, and adequate resources for capacity building. With all this in mind,

this article focuses on expanding school improvement planning to better

address how schools and districts intend to accomplish designated

changes. Based on our work facilitating systemic changes and scale-up to

enhance how schools address barriers to learning and our analysis of the

strengths and weakness of the available science base, this article frames

and outlines some basic considerations related to systemic change. To en-

courage a greater policy discussion of the complexities of implementing

major school improvements on a large scale, a set of policy actions are

proposed.

SCHOOL IMPROVEMENT, PROJECTS,

AND SYSTEMIC CHANGE

Well-conceived, well-designed, and well-implemented prototype innova-

tions are essential to school improvement. Prototypes for new initiatives

usually are developed and initially implemented as a pilot demonstration

at one or more schools. This is particularly the case for new initiatives that

are specially funded projects.

For those involved in projects or piloting new school programs, a com-

mon tendency is to think about their work as a time limited demonstration.

And, other school stakeholders also tend to perceive the work as tempo-

rary (e.g., “It will end when the grant runs out” or “I’ve seen so many re-

forms come and go; this too shall pass”). This mind-set leads to the view

that new activities will be fleeting, and it contributes to fragmented ap-

proaches and the marginalization of initiatives (Adelman, 1995; Adelman

& Taylor, 1997a, 1997b, 1997c, 2003). It also works against the type of sys-

temic changes needed to sustain and expand major school improvements.

SYSTEM CHANGE 57

The history of schools is strewn with valuable innovations that were not

sustained, never mind replicated. Naturally, financial considerations play

a role in failures to sustain and replicate, but a widespread “project mental-

ity” also is culpable.

Efforts to make substantial and substantive school improvements re-

quire much more than implementing a few demonstrations. Improved ap-

proaches are only as good as a school district’s ability to develop and insti-

tutionalize them equitably in all its schools. This process often is called

diffusion, replication, roll out, or scale-up. The frequent failure to sustain

innovations and take them to scale in school districts has increased interest

in understanding systemic change as a central concern in school improve-

ment.

At this point, we should clarify use of the term systemic change in the

context of this article. Our focus is on district and school organization and

operations and the networks that shape decision making about fundamen-

tal changes and subsequent implementation. From this perspective, sys-

temic change involves modifications that amount to a cultural shift in in-

stitutionalized values (i.e., reculturalization). For interventionists, the

problem is that the greater the distance and dissonance between the cur-

rent culture of schools and intended school improvements, the more diffi-

cult it is to successfully accomplish major systemic changes.

Our interest in systemic change has evolved over many years of imple-

menting demonstrations and working to institutionalize and diffuse them

on a large scale (Adelman & Taylor, 1997c, 2003, 2006a, 2006b; Taylor, Nel-

son, & Adelman, 1999). By now, we are fully convinced that advancing the

field requires escaping “project mentality” (sometimes referred to as

“projectitis”) and becoming sophisticated about facilitating systemic

change. Fullan (2005) stressed that what is needed is leadership that “moti-

vates people to take on the complexities and anxieties of difficult change”

(p. 104). We would add that such leadership also must develop a refined

understanding of how to facilitate systemic change.

LINKING LOGIC MODELS FOR SCHOOL

IMPROVEMENT

Figure 1 suggests how major elements involved in designing school im-

provements are logically connected to considerations about systemic

change. That is, the same elements can be used to frame key intervention

concerns related to school improvement and systemic change, and each is

intimately linked to the other. The elements are conceived as encompass-

ing the (a) vision, aims, and underlying rationale for what follows; (b) re-

You might also like

- When The World Goes Quiet - Gian SardarDocument283 pagesWhen The World Goes Quiet - Gian Sardarmengchhoungleang.cbvhNo ratings yet

- ASL Informative Essay)Document2 pagesASL Informative Essay)Hayden Miller50% (2)

- Fullan Change ModelDocument13 pagesFullan Change Modelct hajar turemenNo ratings yet

- Makeup Service ContractDocument2 pagesMakeup Service ContractMary V. Warner-ReeseNo ratings yet

- Implementing The Designed Curriculum As A Change ProcessDocument4 pagesImplementing The Designed Curriculum As A Change ProcessStarNo ratings yet

- Curriculum ImplementationDocument36 pagesCurriculum ImplementationChelle Maale78% (9)

- Managing Organizational Change PDFDocument13 pagesManaging Organizational Change PDFvaneknekNo ratings yet

- Sources of Change & Innovation Types of Change Forms of Change Strategies Models Planning and ImplementationDocument6 pagesSources of Change & Innovation Types of Change Forms of Change Strategies Models Planning and ImplementationJhoijoi BautistaNo ratings yet

- Walmart Live Well - Report An Absence - How To Guide (EN) - Nov 2019Document7 pagesWalmart Live Well - Report An Absence - How To Guide (EN) - Nov 2019Jakaria Ahmed0% (2)

- Untitled 3Document2 pagesUntitled 3Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Systemic Change For School Improvement: Howard S. Adelman and Linda TaylorDocument2 pagesSystemic Change For School Improvement: Howard S. Adelman and Linda TaylorJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Section 7 Managing Change For Organizational Improvement: E838 Effective Leadership and Management in EducationDocument12 pagesSection 7 Managing Change For Organizational Improvement: E838 Effective Leadership and Management in EducationRose DumayacNo ratings yet

- Untitled 6Document2 pagesUntitled 6Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Adelman and TaylorDocument2 pagesAdelman and TaylorJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Achieving Sustainable Systemic Change: An Integrated Model of Educational TransformationDocument15 pagesAchieving Sustainable Systemic Change: An Integrated Model of Educational Transformationd1w2d1w2No ratings yet

- 3 Stages of Change ProcessDocument3 pages3 Stages of Change ProcessAsmadera Mat EsaNo ratings yet

- The School Improvement and Transformation SystemDocument13 pagesThe School Improvement and Transformation SystemJewel Alayon CondinoNo ratings yet

- Staff (E.g., Organization Facilitators) - As A Group, Such District Staff HasDocument2 pagesStaff (E.g., Organization Facilitators) - As A Group, Such District Staff HasJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Connell & Klem - Theory of Change & Ed ReformDocument29 pagesConnell & Klem - Theory of Change & Ed ReformLucía GamboaNo ratings yet

- Increasing Student Success in STEMDocument10 pagesIncreasing Student Success in STEMkimshady26No ratings yet

- Innovation and Change in EducationDocument14 pagesInnovation and Change in EducationDidik Agus TNo ratings yet

- Article SummaryDocument19 pagesArticle SummarySaras VathyNo ratings yet

- Strategies in Facilitating Systemic ChangeDocument2 pagesStrategies in Facilitating Systemic ChangeJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- StanleyG 06 SustainableLeadershipDocument10 pagesStanleyG 06 SustainableLeadershipIngi Abdel Aziz SragNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Related To Change ManagementDocument7 pagesResearch Paper Related To Change Managementgz8jpg31100% (1)

- Module 4 - Curriculum PlanningDocument12 pagesModule 4 - Curriculum PlanningMichelle MahingqueNo ratings yet

- School Organization and ChangeDocument24 pagesSchool Organization and ChangeSamuelNo ratings yet

- The School System Transformation SST Protocol 136Document16 pagesThe School System Transformation SST Protocol 136Paula CostaNo ratings yet

- 8 Forces For Leaders of ChangeDocument6 pages8 Forces For Leaders of Changeapi-298600917No ratings yet

- Educational ChangeDocument43 pagesEducational Changeveena9876100% (1)

- Untitled 11Document2 pagesUntitled 11Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- oRzqOS EJ892382Document24 pagesoRzqOS EJ892382sretalNo ratings yet

- Curriculum ChangeDocument35 pagesCurriculum ChangeFifi AinNo ratings yet

- Untitled 12Document2 pagesUntitled 12Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Current Trends in School Management-Education 4.0Document83 pagesCurrent Trends in School Management-Education 4.0Daisy Joy LacandazoNo ratings yet

- Edited New PresentationDocument6 pagesEdited New PresentationIgnitius DhihwaNo ratings yet

- CDE 802 Innovation and Change in CurriculumDocument19 pagesCDE 802 Innovation and Change in CurriculumObinnaNo ratings yet

- EDUC 205 LESSON No. 1 (LM # 4 Final)Document8 pagesEDUC 205 LESSON No. 1 (LM # 4 Final)Ellarence RafaelNo ratings yet

- Cabral-Proposed Dissertation Title 2Document21 pagesCabral-Proposed Dissertation Title 2Abby- Gail14 CabralNo ratings yet

- Christopher Day, Judyth Sachs - International Handbook On The Continuing Professional Development of Teachers (2005, Open Univ PR)Document31 pagesChristopher Day, Judyth Sachs - International Handbook On The Continuing Professional Development of Teachers (2005, Open Univ PR)Patricia Rejane Feitosa IbiapinaNo ratings yet

- OU Resilience 2017 Paper Hilst SmidDocument19 pagesOU Resilience 2017 Paper Hilst SmidGerhard SmidNo ratings yet

- Leading System TransformationDocument12 pagesLeading System TransformationMatias Reviriego RomeroNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Impl-WPS OfficeDocument6 pagesChapter 3 - Impl-WPS Officemrasonable1027No ratings yet

- Untitled 5Document2 pagesUntitled 5Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Change Theory A Force For School ImprovementDocument15 pagesChange Theory A Force For School Improvementapi-275150179No ratings yet

- Educational Policies On TechnologyDocument3 pagesEducational Policies On TechnologyRodgers OmondiNo ratings yet

- SHARED WEEK 8. Insights Into The Causes and Processes of Educational Change Implementation and ContinuationDocument4 pagesSHARED WEEK 8. Insights Into The Causes and Processes of Educational Change Implementation and ContinuationainhoaferrermartinezNo ratings yet

- Power From Implies Ability To Resist The Power of Others (Riger, 1993) - enDocument2 pagesPower From Implies Ability To Resist The Power of Others (Riger, 1993) - enJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Change ManagementDocument14 pagesChange ManagementshahidNo ratings yet

- Understanding Teacher Change Revisiting The Concerns Based Adoption Model PDFDocument38 pagesUnderstanding Teacher Change Revisiting The Concerns Based Adoption Model PDFPhoebe THian Pik HangNo ratings yet

- Article p946 PDFDocument20 pagesArticle p946 PDFSary MamNo ratings yet

- Key FacetsDocument2 pagesKey FacetsJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Ed. Change ManagementDocument44 pagesEd. Change Managementdeutza_hotNo ratings yet

- 6080-Aaa 5 - Katie Page 1Document11 pages6080-Aaa 5 - Katie Page 1api-583359791No ratings yet

- Format in Written ReportDocument4 pagesFormat in Written ReportPeter O. GoyenaNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Journal of Educational Management: Managing Change in Educational Organization: A ConceptualDocument13 pagesMalaysian Journal of Educational Management: Managing Change in Educational Organization: A ConceptualbavaNo ratings yet

- 2 Focus of Organization ChangeDocument28 pages2 Focus of Organization Changesxcsh88100% (2)

- 教育改革的十个步骤:实现变革Document262 pages教育改革的十个步骤:实现变革wuyugangNo ratings yet

- Implementing Change in EducationDocument4 pagesImplementing Change in EducationrobbagachieNo ratings yet

- Modeling Systems Thinking in Action Among Higher Education Leaders With Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision MakingDocument20 pagesModeling Systems Thinking in Action Among Higher Education Leaders With Fuzzy Multi-Criteria Decision MakingKhoirul MunirNo ratings yet

- Is Change Management Obsolete?: SciencedirectDocument11 pagesIs Change Management Obsolete?: Sciencedirectahmedanoof7879No ratings yet

- Leaders in Succession: Rotation in International School AdministrationFrom EverandLeaders in Succession: Rotation in International School AdministrationRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Succession Planning and Management: A Guide to Organizational Systems and PracticesFrom EverandSuccession Planning and Management: A Guide to Organizational Systems and PracticesNo ratings yet

- How Does The Manitoba Islamic Mortgage Compare With A Conventional Mortgage?Document1 pageHow Does The Manitoba Islamic Mortgage Compare With A Conventional Mortgage?Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 11Document2 pagesUntitled 11Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 5Document2 pagesUntitled 5Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 12Document2 pagesUntitled 12Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Adelman and TaylorDocument2 pagesAdelman and TaylorJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Strategies in Facilitating Systemic ChangeDocument2 pagesStrategies in Facilitating Systemic ChangeJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Staff (E.g., Organization Facilitators) - As A Group, Such District Staff HasDocument2 pagesStaff (E.g., Organization Facilitators) - As A Group, Such District Staff HasJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Power From Implies Ability To Resist The Power of Others (Riger, 1993) - enDocument2 pagesPower From Implies Ability To Resist The Power of Others (Riger, 1993) - enJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 6Document2 pagesUntitled 6Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Key FacetsDocument2 pagesKey FacetsJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Systemic Change For School Improvement: Howard S. Adelman and Linda TaylorDocument2 pagesSystemic Change For School Improvement: Howard S. Adelman and Linda TaylorJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Untitled 3Document2 pagesUntitled 3Jakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research QualitativeDocument13 pagesQualitative Research QualitativeJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Greater Toronto Area (GTA) Teachers' Perspectives On Teacher EfficacyDocument11 pagesGreater Toronto Area (GTA) Teachers' Perspectives On Teacher EfficacyJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Secondary BooklistDocument5 pagesCambridge Secondary BooklistJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Understanding Lesson Planning - GlossaryDocument1 pageUnderstanding Lesson Planning - GlossaryJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- ParagraphDocument4 pagesParagraphJakaria Ahmed100% (1)

- Marketing: From Evolution To PresentDocument3 pagesMarketing: From Evolution To PresentJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Student CalendarDocument12 pagesStudent CalendarJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Primary BooklistDocument22 pagesCambridge Primary BooklistJakaria Ahmed100% (1)

- Short Term Plan Templete: Pupil(s) / Group: Class Level: Class Teacher: DAY Sunday Monday StrandDocument4 pagesShort Term Plan Templete: Pupil(s) / Group: Class Level: Class Teacher: DAY Sunday Monday StrandJakaria AhmedNo ratings yet

- ABC Analysis in The Hospitality Sector: A Case Study: January 2017Document4 pagesABC Analysis in The Hospitality Sector: A Case Study: January 2017Sarello AssenavNo ratings yet

- Soal UjianDocument3 pagesSoal UjianNuryeri Efrita HarahapNo ratings yet

- 3 Customer ServiceDocument12 pages3 Customer Serviceharsh2rcokNo ratings yet

- Calif. Wildfire Surges To Nearly 200 Square Miles and Spreads Into Yosemite National ParkDocument3 pagesCalif. Wildfire Surges To Nearly 200 Square Miles and Spreads Into Yosemite National ParkCynthia TingNo ratings yet

- BSBA FINAL LOADING For BOT 2021-2022 1st SEMESTERDocument5 pagesBSBA FINAL LOADING For BOT 2021-2022 1st SEMESTERMaureen GalendezNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Culture5Document43 pagesAspects of Culture5Almira Bea Eramela Paguagan100% (1)

- The Art of Empathy Translation PDFDocument90 pagesThe Art of Empathy Translation PDFusrjpfptNo ratings yet

- Department of Defense - Joint Vision 2020 PDFDocument40 pagesDepartment of Defense - Joint Vision 2020 PDFPense Vie Sauvage100% (1)

- Elements of A Negligence Claim: Car Accidents Slip and FallDocument19 pagesElements of A Negligence Claim: Car Accidents Slip and FallOlu FemiNo ratings yet

- Book Promotion AssignmentDocument5 pagesBook Promotion Assignmentapi-551846304No ratings yet

- The Absurd in Endgame and The MetamorphosisDocument7 pagesThe Absurd in Endgame and The MetamorphosisMubashra RehmaniNo ratings yet

- Affidavit Sarah JaneDocument2 pagesAffidavit Sarah JaneJholo AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- "Untitled Austin Project": Crown Venice Productions, LLC ReimbursementsDocument2 pages"Untitled Austin Project": Crown Venice Productions, LLC ReimbursementsButtNo ratings yet

- PPP Frame WorkDocument10 pagesPPP Frame WorkchelimilNo ratings yet

- 42 Items Q and ADocument2 pages42 Items Q and AJoy NavalesNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Stock Market With Commodity Market in MalaysiaDocument20 pagesRelationship Between Stock Market With Commodity Market in MalaysiaOmar LuqmanNo ratings yet

- 2022 JOAP Remedial Law Mock Bar ExaminationDocument14 pages2022 JOAP Remedial Law Mock Bar ExaminationVincent Jave GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Grade5 StudentEditionDocument267 pagesGrade5 StudentEditionsyed hassanNo ratings yet

- Symbiosis Law School, Pune: SUBJECT - Media and Entertainment Law Alternative Internal AssessmentDocument15 pagesSymbiosis Law School, Pune: SUBJECT - Media and Entertainment Law Alternative Internal AssessmentAditya KedariNo ratings yet

- Lista 5095568 Planilha Formandos Pronta para SEIDocument193 pagesLista 5095568 Planilha Formandos Pronta para SEIIgor BarretoNo ratings yet

- 61 Journal of Chinese Literature and CultureDocument15 pages61 Journal of Chinese Literature and CultureYvonne ChewNo ratings yet

- SBN-1421: Department of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) Act of 2017Document8 pagesSBN-1421: Department of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) Act of 2017Ralph RectoNo ratings yet

- Basketball Basic RulesDocument10 pagesBasketball Basic RulesMohan ArumugavallalNo ratings yet

- Report of The Film Fact Finding CommitteDocument435 pagesReport of The Film Fact Finding CommitteOmar ZakirNo ratings yet

- Unanswered PrayersDocument3 pagesUnanswered Prayersdeep54321No ratings yet

- Sps. Ong vs. Roban LendingDocument2 pagesSps. Ong vs. Roban LendingPraisah Marjorey PicotNo ratings yet

- Codex HarlequinsDocument10 pagesCodex HarlequinstommythekillerNo ratings yet