Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Challenging Dominant Discourses On Abortion From A Radical Feminist Standpoint

Challenging Dominant Discourses On Abortion From A Radical Feminist Standpoint

Uploaded by

Tengiz VerulavaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Challenging Dominant Discourses On Abortion From A Radical Feminist Standpoint

Challenging Dominant Discourses On Abortion From A Radical Feminist Standpoint

Uploaded by

Tengiz VerulavaCopyright:

Available Formats

Article

Affilia: Journal of Women and Social

Work

Challenging Dominant 2015, Vol. 30(1) 83-95

ª The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permission:

Discourses on Abortion From sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0886109914549232

a Radical Feminist Standpoint aff.sagepub.com

Indira Gilbert1 and Vishanthie Sewpaul1

Abstract

The article, which is based on the narratives of 15 women in the Durban metropolitan area, contests

liberal feminist views of abortion resting on the free choice of women. Adopting a radical feminist

standpoint, it locates the abortion decision within structural constraints on women’s lives, raising

the relationship between socioeconomic freedom and women’s reproductive health choices. The

article also contests the popular pro-life/pro-choice dichotomy, interrogates the influence of

popular pronatalism and discourses on motherhood on women’s choices, and highlights feminist

relational ethical thinking that underscores women’s choices even as they acknowledge principled

ethical concerns around the sanctity of life.

Keywords

feminist theories and research, narrative discourse, poverty, qualitative, reproductive rights

Introduction

Human rights, ethical, and social justice considerations, which are at the heart of the abortion debate,

are of central concern to social workers. The proposed new global definition of social work (Inter-

national Association of Schools of Social Work [IASSW]/International Federation of Social Work-

ers [IFSW], 2014) reiterates that the pursuit of social justice and human rights grants social work its

legitimacy. In abortion rests the fundamental questions of life and death, the meaning of personhood,

and when life begins that elicit moralizing stances, with an apparent inability to bring together

opposing pro-life and pro-choice views. This article, which is based on an in-depth study of the nar-

ratives of 15 women, contests the liberal feminist view of abortion resting on the free choice of

women. Adopting a radical feminist standpoint, it locates the abortion decision within the structural

constraints on women’s lives, raising the relationship between socioeconomic freedom and women’s

reproductive health choices. The article also contests the popular pro-life/pro-choice dichotomy,

interrogates the influence of popular pronatalism and discourses on motherhood on women’s

1

School of Applied Human Sciences, University of KwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa

Corresponding Author:

Indira Gilbert, School of Applied Human Sciences, University of KwaZulu Natal, Howard College Campus, Durban 4041,

South Africa.

Email: indira.gilbert@gmail.com

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

84 Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work 30(1)

choices, and argues that contextual morality (Tronto, 1993, p. 27), underscored by the feminist

relational ethic of care, frames women’s moral reasoning in abortion decision making, even as they

acknowledge principled ethical concerns about violating the sanctity of life.

Context of the Study

This research was conducted in the Durban metropolitan area in the province of KwaZulu-Natal

(KZN), South Africa. KZN has the largest population in South Africa with approximately 11 million

from the country’s 50 million people of black, Asian, colored and white descent (South Africa Year-

book, 2010/2011). The Durban metropolitan area, 1 of the 11 municipalities in KZN, has a cosmo-

politan population of over 3 million people, with the majority being African black and isiZulu

speaking. Since the legalizing of abortion in South Africa, approximately 650,000 legal abortions

were performed between 1997 and 2007, with 90,000 in KZN. In 2012, there were 85,302 reported

abortions in South Africa (Johnston, 2013).

In 1997, the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act No. 92 of 1996 was promulgated. This Act,

which allows South African women access to abortion on demand up to 12 weeks of pregnancy; on

the recommendation of a medical practitioner from 13 to 20 weeks; and on the recommendation of

two medical practitioners beyond 20 weeks, was welcomed by pro-choice groups but raised strong

opposition from pro-life groups. An exceptionally contentious aspect of the Act is that it allows chil-

dren from 12 years of age to secure an abortion without parental consent. South Africa’s pro-choice

abortion law does not reflect the majority views of its population who are largely pro-life (Human

Sciences Research Council [HSRC], 2004).

Literature Review

Abortion raises controversial ethical questions, often linked to religious and cultural beliefs, which

influence attitudes toward and decisions about abortion (Adamczyk, 2009; Jelen & Wilcox, 2003).

The influence of religion is not absolute; individual values and situational factors mediate the influ-

ence of religion on moral decision making. As the major world religions view abortion as murder,

women who choose abortions might experience guilt, shame, self-hatred, and fear of God (Try-

bulski, 2005; Vukelić, Kapamadzija, & Kondić, 2010). Religious views are generally informed

by the Kantian categorical imperative (CI), based on deontological or duty-based ethics that presume

an eminently autonomous, rational being. The distinguishing feature of the CI is that moral worth is

judged by the rightness or wrongness of an act itself. The maxim of this imperative is that when one

makes a particular choice, one should will that it become the universal law (Beauchamp, 1991). It is

based on principles that are universalizable and committed to an abstract impartiality, where partic-

ular circumstances, outcomes, and relationships bear no relevance to the ethical decision making

(Tronto, 1993). In contrast to this, is contextual morality linked with the feminist relational ethic

of care, with attentiveness, responsibility for others, competence, and responsiveness, being its core

elements (Tronto, 1993)?

Contextual morality is not only women’s prerogative. The relegation of discourses on care to the

private and domestic sphere has disadvantaged women. It is important that the political and public

dimensions of care are recognized and that they are appreciated as issues of concern by both women

and men. Morality reflects individual principles of right and wrong, which are codified into formal

sets of ethical principles. While ethical codes and principles establish what one ought to do in a given

situation, in reality these are not always consistent. While one code may condemn, another might

valorize the same act. There are often double standards, with explicitly stated public, official sys-

tems of ethics and covert, personal morality. Many moral questions are fraught with ambiguity, and

doing one’s duty by following the rules, at times, produces more harm than good (Bauman, 1993).

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

Gilbert and Sewpaul 85

Women’s decision to abort cannot be considered in isolation from their contextual realities. Saul

(2003) posited that women’s right to choose does not negate the impact of the moral dimension.

Women struggle with numerous competing values and life exigencies as they make the abortion

decision. While radical feminism focuses on the structural constraints on women, it does not deny

individual agency. As moral agents, women do exercise responsibility and power, and they seek to

make decisions in their interests and in the interests of others (Tronto, 1993). When women expe-

rience dire financial circumstance and do not have the support of partner, family, and friends, they

are more likely to opt for abortion (Williams & Shames, 2004). The severity of domestic violence

also was found to have increased the chances of women seeking abortion (Kaye, Mirembe, Bante-

bya, Johansson, & Ekstrom, 2006). Physical abuse may contribute to coercion into the abortion deci-

sion, with coercion taking the forms of pressure, emotional blackmail, threats, and/or violence by

persons of influence (Reardon, 2002).

Older women who have completed their childbearing might choose abortion, as they do not want

their children to suffer material and emotional deprivation (Finer, Frohwirth, Dauphinee, Singh, &

Moore, 2005). Where partners deny paternity, women may choose to abort to protect children from

growing up fatherless, among other personal reasons (Finer, et al., 2005; Jones, Frohwirth, & Moore,

2007). Some women who abort compare themselves with the dominant constructs of ideal mother-

hood and decide that they do not want to be inadequate mothers. Thus, Jones, Frohwirth, and Moore

(2007) concluded that abortion could be considered an act of responsibility. There are, however,

arguments that abortion for socioeconomic reasons serves the narrow interests of women (Hilton,

2007). The results of this study, which was designed, as described subsequently, to understand the

experiences of women who opted for abortion, dispute this argument.

Research Design and Methodology

The study adopted a qualitative, interpretivist paradigm (Cohen & Manion, 1994; Creswell, 2012)

and a feminist research design, which is committed to understanding the experiences of women and

gendered power relationships and discourses in a predominantly patriarchal society (Mappes &

Zembaty, 1997). Fifteen conversational style in-depth interviews of over an hour duration each and

follow-up telephone interviews, when necessary, were conducted with the aid of a loosely formu-

lated interview guide. The following key questions framed the study: How do the current contextual

realities affect abortion decision making? What role does religious beliefs and cultural values play in

the decision? How is right and wrong negotiated within the context of religious and cultural expec-

tations? What support systems/structures are available? What is the potential impact of dominant

discourses of motherhood and fatherhood on the abortion decision and on the consequences of abor-

tion? Interviews were arranged per the convenience of the participants at venues chosen by them.

Participants were accessed via convenience sampling at an abortion clinic and a public hospital, with

entry facilitated by the health professionals. The women had access to these facilities on a nonfee-

paying basis.

The interviews were audio recorded with permission from the participants and transcribed verba-

tim, thus allowing for rich presentation of textual data in the analysis. Critical discourse analysis

(CDA), which focuses on social structures and the use of language (Fairclough, 2009) to describe

how existing structures impact the lives of women, was used in the analysis and discussion of the

data. In Fairclough’s (2009) dialectical–relational approach to CDA, the focus is on the analysis

of structures and context in addition to language. While textual analysis is important, it is only a part

of the discourse analysis. The emphasis is on how the language action is framed within a broader

social order (Fairclough, 2009). Wodak and Meyer (2009) highlight language as an activity

and social practice. An oral utterance is embedded in a discourse and regarded as ‘‘a manifestation

of social action which again is widely determined by social structure’’ (Wodak & Meyer, 2009, p. 6).

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

86 Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work 30(1)

All ethical considerations, with particular emphasis on doing no harm, maintaining confidential-

ity, beneficence, anonymity in the reporting of data through the use of pseudonyms and ensuring that

the women cannot be identified by others in the analysis, obtaining written informed consent, and

ensuring that psychosocial support was provided, when necessary, were adhered to. Permission was

granted from the management of both service centers and ethical approval was granted from the

University of KwaZulu Natal Research Ethics Committee. The data were coded, categorized and

built into major themes, and informed by qualitative, interpretivist research and CDA critically

engaged with and interpreted. Thus, the thick description of the data, in the voices of the women,

and the analysis are presented as an integrated whole, rather than separately. In a nutshell, the demo-

graphics showed that 11 of the women were in the 21- to 30-year age-group, 3 were below 20 years

of age, and 1 was over 30; 13 were single and 2 were cohabiting. There were nine women of African

black descent, three of Indian descent, and three of white descent. The majority identified them-

selves as Christian, two of the Indians as Hindu, and one as having no religious affiliation. Six of

the women were students, six were unemployed, and three were employed. Five of the women had

existing children, that is, three had one child each, one had two children, and one had three children.

The data were analyzed in relation to the following researcher constructed themes, based on the nar-

ratives of the women and on literature: (1) structural constraints on women’s lives, (2) challenges to

the pro-life/pro-choice dichotomy, (3) the motherhood mandate and popular pronatalism, and (4) the

influence of feminist relational ethics on the abortion decision.

Structural Constraints on Women’s Lives

One of the recurring themes in the narratives of the women was financial hardship combined, in

some cases, with abandonment by their partners on learning about their pregnancies. Williams and

Shames (2004) found that financial constraints, and women’s concerns about their inability to pro-

vide adequately for the child, were major push factors toward abortion. With pregnancy, childbirth,

and child care constructed as women’s responsibilities (Doucet, 2000; Sewpaul, 1999), many men in

South Africa abandon their partners during pregnancy (Richter & Morrell, 2006). Zanele’s story rep-

resents the experiences of other women in this regard:

When I found out that I was pregnant I called my boyfriend and told him about it. He didn’t like it. He

said that he didn’t want anything to do with it. I said what I am supposed to do. He said that he doesn’t

know. We never spoke since the day. He never came to me. Even to today. He does not know I did this. I

don’t want to see him no more.

Zanele’s partner asserted that ‘‘he didn’t want anything to do with it’’ and that ‘‘he doesn’t know,’’

thus placing the responsibility for the pregnancy on Zanele who was unemployed and poor. This is a

discourse that privileges men into abandoning their partners and evading responsibility, leaving

women to cope on their own. Women have internalized this and have come to accept responsibility

for becoming pregnant, for making the abortion decision, and for coping with its consequences.

Zanele’s feelings of hurt and disappointment were palpable as she described shifting from a position

of having a boyfriend that she thought cared for her to being abandoned to the point of ‘‘we never

spoke since the day.’’ Men assume that it is up to women to decide what to do with pregnancies and

the birth and care of children. In Umlazi, south of Durban, it was reported that only 7,000 of the

67,000 men ordered to pay maintenance toward the care of their children in 2002, complied

(Richter & Morrell, 2006). Men do not only refuse to pay maintenance but sometimes refuse to

acknowledge the existence of their children.

In South Africa, female-headed households are a common feature. Women form the largest

(60%) proportion of the unemployed in the country (Trading Economics, 2012). South Africa has

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

Gilbert and Sewpaul 87

an unemployment rate of about 25% (Statistics South Africa, 2012), which is among the highest in

the world (Kingdom & Knight, 2004). When discouraged work seekers are included, this percentage

expands to 36 (Vavi, 2012). Even those who complete formal schooling are unable to secure

employment, as seen in the case of Phindile who stated, ‘‘I came to Durban with my son to find

employment. Even though I have my matric (a secondary school exit level qualification) I cannot

find employment.’’ Phindile did a further postmatric course in the hope of obtaining a better paying

job. Unskilled and semiskilled women generally hold lower paid jobs compared to men, and even

though women are employed, they suffer financial hardship. With the increasing cost of living in

South Africa and limited work opportunities, women who are dependent only on the Child Support

Grant (CSG; which is currently about US$30 per month for children up to 18 years of age) and the

working poor women experience extreme difficulty in making ends meet. Five of the nine African

black participants, in this study who had children, were in receipt of a CSG which was their primary

means of support. A CSG, which is inadequate for a month’s rent on accommodation, will enable

purchase of about 15 liters of milk and 12 loaves of bread in South Africa. Under circumstances

of dire need, abortion becomes a viable option for many women (Jones et al., 2007; Williams &

Shames, 2004). Mphilo, who was dependent on the CSG, said, ‘‘I receive Child Support grants. . . .

how am I gonna manage? It’s too hard to bring another child when you do not have enough support

for her or for him.’’

Unemployment, poverty, child neglect, and child abandonment are often linked. Some of the

women in this study reasoned that it was more ethical to abort than continue the pregnancy and aban-

don the baby, which has become a feature in South Africa. In 2011, there were 2,583 abandoned

babies, an increase of 36% from 2010 (Chaykowski, 2012). Abandoned babies are left alone, gen-

erally on roadsides, in public toilets, or bushes, primarily on account of unemployment, poverty,

abandonment by partners, and/or HIV/AIDS. Women who experienced difficulty in providing for

their existing children did not wish to repeat this, and they did not want their children to suffer even

more deprivation. It is an irony that amid the dominant discourse of men as providers and protectors,

men abandon their partners and children and do not pay for child support (Richter & Morrell, 2006),

and that women are left to literally carry the baby. Yet women are the ones, not the men, who are

demonized for the pro-abortion choices that they are often forced to make.

The country’s unemployment reflects its racial history and demographics, where the lower

income mainly black women are affected, particularly under conditions of capitalist trade liberal-

ization (Bond, 2005; Sewpaul, 2013a; Trading Economics, 2012). Education is stratified as in all

developing countries (Buchmann & Hannum, 2001), which makes it difficult for the lower socio-

economic groups to secure decent and gainful employment. Some of the women in this study were

struggling against the odds to obtain education, which they rightfully saw as an exit from the cycle

of poverty and a means toward a better future. A premature and unplanned pregnancy would have

negatively impacted their aspirations. Phindile stated, ‘‘I am studying. It will hinder my present

plans for making a future for myself and my son.’’ Contextual moral reasoning framed the deci-

sions of the participants as they considered their future and that of their present/future families.

When women are supported to contribute to their care and those of their children, they are able

to break the intergenerational cycle of poverty. Enhancing women’s access to education, eco-

nomic opportunities, health, and creating cultural spaces that respects women and men equally

reduces fertility rates, child mortality, and intergenerational poverty and may reduce the abortion

rate. Advancing the well-being of people and minimizing gender inequality do contribute to

broader social–economic and political development (Klasen, 2002; Sen, 2005). Participants

expressed the view that they wanted to have children under conditions that were more conducive

to caring for a baby.

Family and partner violence, as a structural constraint, is also a predictor of abortion (Kaye et al.,

2006; Whitehead & Fanslow, 2005). The internalized, patriarchal values of society contribute to

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

88 Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work 30(1)

men treating women as inferior and as property that they have ownership of (Dickerson, 2013). This

was evident in the case of Zama:

He was emotionally abusive. He used to say ‘you listen—you are a woman, you must know your place.

When I am talking you must shut-up.’ If a person is making you feel inferior then how can you share

something with a person like that? So that’s one thing that put me off about him—he doesn’t want

me to speak my mind. If I don’t like something I can’t say it because he’s gonna tell me he’s the man,

I must listen to him so I don’t have to say anything. If he says this or that, it is what he says or nothing at

all. Sort of like controlling so I decided to get rid of him. So as soon as I got rid of the baby I got rid of

him. So the relationship with him also affected my decision to abort.

The gendered power imbalances are clear in the above, where Zama was expected to be passive and

complaint. But Zama indicated that she did not wish to submit to a controlling partner; she took control

of her life. Making a decision to abort was, for her a manifestation of her strength and agency, reflected

in the power of her words, ‘‘as soon as I got rid of the baby I got rid of him.’’ Afika’s narrative spoke of

substance abuse and domestic violence that contributed to her decision to abort. She said:

My dad drinks a lot. He usually says if one of us girls gets pregnant, he’ll kill them or throw them away

from home. When I thought of those things I just couldn’t, I just couldn’t keep my baby. And I thought of

my mum. She would suffer for my consequences. While I was growing up my father used to hit me and

my mum. I just couldn’t, just couldn’t allow that.

Women who had painful experiences with their previous or current partners feared a repeat of the

experience (Jones et al., 2007). Phindile, for example, stated, ‘‘I have an 8-year-old son whose father

abandoned both of us when the baby was born. I was left to be both a mother and father to the child. I

have an unstable relationship with my partner. He visits me whenever he chooses to. He is never

there when I need him for anything.’’ Phindile played a dual parental role, which became very

demanding. Zama’s past relationship also impacted her decision. She stated, ‘‘When I see my child

I remember what I went through with the father. I didn’t want this again.’’ Although Anita was in a

stable relationship, she was afraid of the possibility of being abandoned yet again, proffering this to

be one of the major factors in her abortion decision. Anita said:

I was previously married. My husband was having an affair. We separated after our first child. We later

reconciled and had our second child. He did the same again and we got divorced. I had to go through so

much. I cannot imagine what my children went through. I don’t want to bring a child into this world now

not being married and not having that grounding for three children because if he decides that he wants to

leave one day and walk out what happens to me and the child?

Pro-choice advocates generally adopt a liberal feminist perspective, emphasizing women’s freedom

of choice (Smith, 2005). From a liberal feminist pro-choice stance, women are seen as having a total

control of their bodies and autonomy in decision making. It does not consider how women’s choices

might be affected by structural factors. The narratives of the women speak to the fact that the women

did not choose abortions simply because they had a right to such choice. There were dire life circum-

stances that pushed them into making the decision, thus rendering their choice a constrained one, a

finding that also brings into question the pro-life/pro-choice dichotomy as discussed subsequently.

Challenges to the Pro-life/Pro-choice Dichotomy

Debates around abortion generally center on the pro-life/pro-choice dichotomy. With all the major

religions promoting life and valorizing childbirth and children, South Africans generally adopt a

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

Gilbert and Sewpaul 89

pronatalistic view (Sewpaul, 1999). It is this pronatalism and the value of the sanctity of life that

underscores the pro-life position (Smith, 2005). The majority of South Africans do not approve

of abortion on demand, and a very small minority is in favor of abortion under particular circum-

stances (HSRC, 2004). There is a presumption that if one is pro-life, one cannot or will not make

a pro-abortion decision. The results of this study challenge this view. While it may seem a paradox,

all of the women expressed decidedly pro-life views, even as they chose abortion. None of the

women spoke of the unborn in objectified pro-choice language of ‘‘the fetus.’’ They talked about

the unborn in endearing and humanizing terms like ‘‘my baby’’ or ‘‘my child,’’ and during the course

of the interviews, the women cumulatively made 45 references to the unborn as ‘‘baby.’’ Anita

talked about bonding with the baby that you don’t even know, you don’t ever see.

The women’s pro-life stances could be seen by them taking on the dominant pro-life discourses

about those who opt for abortion being sinners and murderers. Afika said, ‘‘I know that I have killed

an innocent child,’’ while Zama claimed ‘‘there is no difference between me and a murderer.’’ Anne

adds to the chorus of women’s self-imposed judgments and conscience with, ‘‘I think that I am a

murderer—that’s what I’m thinking.’’ The paradox of being pro-life while opting to abort made the

abortion decision more difficult as the women had to bear the burden of guilt and responsibility for

taking a life.

Some of the women humanized the unborn to the extent that they wanted to fulfill cultural rituals

to appease the ancestors and allow the spirit of the unborn to rest in peace. Zama equated the loss of

the unborn to that of family members. She said:

In our Zulu culture, when you lose a baby, when you lose your mother, when you lose your spouse, you

know you need to go for a cleansing ceremony. . . . whether you are only 3 weeks pregnant or 6 weeks

pregnant at the end of the day that was gonna be a human being and a part of your family. So you need to

go for a cleansing . . . it depends on how strong the ancestors are. And it’s worse if it’s from the father’s

side. If the father’s side has very strong ancestors then the effect is very . . . it’s very powerful.

While Mphilo stated that:

In our culture we are not allowed to do this. And when we do this, we believe that it’s a person at the end

of the day. It grows up. When it grows up it will come back—need something to buy like clothes for him

for her, and a name . . . maybe after 5 years when she or he’d grow, come back to me on a dream and say

‘my mother I want my name—I don’t know my name, my mother I’m not wearing anything’. Then I’m

gonna tell them (my parents) that no one was there and I got to do these things.

Pro-choice arguments generally lie within liberal feminism, which adopts a rights-based approach

(Enns, 2010) but within existing sociopolitical and cultural orders. It ignores fundamental aspects

of power imbalances and the multiple social influences on the individual. To this end, women are

not seen in the context of their social milieu, and how they affect, and are affected by those around

them when making the abortion decision. One cannot negate the importance of liberalism in the

abortion debate. Liberal feminism successfully gained a range of rights for women. The abortion

discourse, however, goes beyond a rights-based approach as borne out in this study. Abortion is

linked to issues regarding patriarchy, systems of oppression, and structural conditions that push

women to opt for abortion. Radical feminism views the oppression of women as the most basic form

of societal oppression, which is evident in all races, cultures, and socioeconomic groupings. Radical

feminism challenges the patriarchal division of society along gender lines, which privileges men

while oppressing women (Dickerson, 2013; Dominelli, 2012; Sewpaul, 2013b). Male supremacy,

in itself, is considered a systemic form of domination. It involves more than poor male attitudes

toward women, as dominance and superiority are institutionalized with existing political and social

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

90 Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work 30(1)

organizations promoting patriarchy. This makes radical feminists skeptical of political action within

existing systems. Their demands are that patriarchy be defied at every level of society for meaning-

ful changes to occur in the interests of women.

The results of this study indicate that while women do make the choice to abort, the choices are,

more often than not, constrained ones in response to structural factors such as unemployment and

poverty; partner rejection and abandonment; and the fear, stigma, and shame of being pregnant and

unmarried. From a radical feminist perspective, having to choose abortion is an indictment on soci-

ety, and it highlights the relationship between the personal and political dimensions of women’s

lives. While women have a right to safe and legal reproductive health choices, including abortion,

it is up to society to ensure that societal conditions support women’s choices. Structural oppressions

and limitations, which force women into decisions that may go against their moral impulse, must be

confronted, challenged, and eliminated. If pronatalism and pro-choice are the preferred options as

reflected in popular daily discourse, especially those of religious doctrines, then societal discourse

around pregnancy and childbirth within the institution of marriage will have to be challenged and

de-constructed so that women, who become pregnant outside of marriage, do not opt for abortion

out of fear and shame.

The Motherhood Mandate and Popular Pronatalism

The norms and values of the family, the community, and society influence one’s personal decisions

(Ekstrand, Tydén, Darj, & Larsson, 2009). Popular pronatalism contributes to motherhood being

revered and rarefied (Sewpaul, 1999) but only within designated circumstances—at the right age,

and in an increasingly consumerist society at the right time, and within the context of marriage.

Thus, when pregnancy occurs outside of these ideal circumstances, secrecy is maintained (Engel-

brecht, 2005). Pronatalism and the motherhood mandate, where every woman is supposed to want

to be a mother (Gillespie, 2003; Sewpaul, 1999) irrespective of her life circumstances, contribute to

guilt and an internalization of society’s judgments about one’s moral badness when a proabortion

choice is made (Engelbrecht, 2005). Yet, at the same time, there is an overwhelming sense of shame

on account of the stigma attached to out-of-wedlock pregnancies that push women into the abortion

decision. Thus, women are placed in a double bind demonized for becoming pregnant out of wed-

lock and for making the decision to abort. Shame, guilt, and fear of family and societal reactions

often contribute to women not disclosing both the pregnancy and the subsequent abortion.

Social standing in the community affects individual family member’s behavior and choices. Fam-

ilies, concerned about their own reputation, are less accepting of their daughters’ out-of-wedlock

pregnancies, as reflected by Nerissa who said, ‘‘My family’s name is important to them. A pregnancy

and a baby while I am unmarried will let them down.’’ Vani’s parents coerced her into having an

abortion, ‘‘My dad was very angry when my mother told him that I was pregnant. He just insisted

that I have the abortion.’’ Abortion was used to protect the status and reputation of the family in

the community where issues are gossiped about, preventing women from seeking assistance and sup-

port from local structures. Both out-of-wedlock pregnancies and abortion carry stigma and constitute

sources of gossip. Gossip stems from and leads to further stigma as was observed by Stembile, ‘‘In

communities like back home people would start looking at you differently and start giving you dif-

ferent names. Labeling you and stuff like that—so it is not really easy being in a Zulu culture and

having a person saying that I had an abortion.’’

While Stembile linked her experience to the Zulu culture, such stigma permeates the various

racial, ethnic, and language groups in South Africa. Participants were reluctant to disclose the abor-

tion, as they did not want to be judged. Zama maintained, ‘‘If I have to go to a support group I will

go. But I don’t want to go to where there are people I know—people who are gonna judge me. I’d

rather go to people who are strangers where I can be free—not a person that’s gonna tell me 4 or 5

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

Gilbert and Sewpaul 91

years from that time ‘hey you killed your baby.’’’ What other people knew and thought about them

was important. Zentle said, ‘‘you can talk to them now but then in the future one mistake you do they

tell you about all the bad things you’ve done.’’ The dominant societal discourse in South Africa is

that children are a blessing but within the context of marriage. Children born out of wedlock are

referred to as ‘‘illegitimate,’’ often described by the derogatory term ‘‘bastards’’ (Merriam-

Webster Online, 2013). Participants, in this study, did not reveal the pregnancy or abortion to anyone

except to the partner where they were still in a relationship, and they did not share their postabortion

experiences with anyone. It is inimical that while children are celebrated, there is enormous stigma

attached to pregnancy out of wedlock. The dominant discourses on what constitutes the ideal (gen-

erally conceptualized as the Western nuclear, two-parent family) needs to be challenged, decon-

structed, and reconstructed to allow every child born to be a wanted, loved child.

The Influence of Feminist Relational Ethics on the Abortion Decision

The narratives spoke of the women’s acute awareness of the responsibilities of motherhood and the

responsibilities that they had toward children and other significant people in their lives. On the basis

of contextual morality, women make decisions informed by an ethic of care and responsibility

toward others, including the unborn (Cannold, 1998; Finer et al, 2005; Jones et al., 2007), which was

evident with participants. Mphilo stated that, ‘‘Being a mother means many things . . . it is a big step

because it is too hard to be a mother especially a single mother because all the responsibility it’s for

you, your own. We have to do everything for the children, even if sick, or hungry, for clothes, school.

I go and see to the school. It is also financial.’’ Mphilo was solely dependent on a CSG and could not

provide for her children’s needs. Zanele too experienced motherhood as being hard. She said:

Sometimes, I enjoy being a mother—not always—because it is hard. I am not working and it is hard to

provide for them. It’s good to have children, playing with them, hugging them, seeing them run around. It

is not good when they come to you and say ‘‘mummy, I’m hungry’’ and you don’t know what to give

them. I know that I am not a good mother because I am not educated, and I do not have a good job. Being

a good mother means having a good job, getting a good salary, taking good care of them, when they need

something you are there for them. I think that being a mother takes a lot of your time.

Zanele was dependent on a CSG and her inability to provide food of her children caused anguish.

She judged herself against the standard of a ‘‘good mother’’ who has an education, a good job, a

good salary, and provides for her children. Women internalize societal oppression (Freire, 1970,

1973) and fail to see how external structural constraints impose limitations on access to resources

and on the mothering role. Women believe that they have to be everything to their children, even

when they are denied education, gainful employment, and the support of their partners. The parti-

cipants shouldered the responsibility of caring for children and blamed themselves for not being able

to adequately provide for their children. Sen (1999, pp. xi–xii) cogently draws attention to the rela-

tionship between freedom and responsibility, arguing that, ‘‘the freedom of agency that we indivi-

dually have is inescapably qualified and constrained by the social, political and economic

opportunities that are available to us.’’ If women have to fulfill their responsibilities in feeding,

clothing, educating, and providing adequate health care for their children, they need the economic

freedom to do so. The awareness of the complexities and demands of motherhood influenced parti-

cipants’ decision making, as voiced by Cheryl, ‘‘Being a mother means that I will have to place the

child’s needs first. He will be dependent on me for everything. I cannot be a mother right now. I

complete my degree in a year and want to finish it.’’ Those who were studying wished to complete

their studies in order to secure good jobs and provide a good life for their future families. This mes-

sage was reiterated by Stembile who said, ‘‘I had to choose between having a standstill in life

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

92 Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work 30(1)

looking after a baby or focusing on working on something that will in future help me and the babies I

would have in future.’’ The findings of this study are consistent with that of Jones et al. (2007) who

concluded that women chose abortion on account of their desire to be good mothers.

Women also did not wish to go through the process of developing a strong emotional bond with

the unborn during the pregnancy to give the baby up for adoption. Mphilo stated that with a full-term

pregnancy, one would develop an emotional attachment with the baby and that it would be traumatic

to give up the child, ‘‘You can’t have a baby to give to someone (became emotional). It’s too hard to

part with your child—to have the pain. So, so . . . it’s too hard. So I decided to do the abortion.’’

Mphilo experienced pain just pondering the thought of having a baby and giving the baby up for

adoption.

Women are considered primary childminders, and physical and emotional demands are placed on

them even where they hold outside jobs. The historic view of women being the primary house mind-

ers (Doucet, 2000) has not changed sufficiently to accommodate women who hold outside jobs.

Women therefore, over and above work responsibilities, assume a large portion of domestic respon-

sibility, which remain unrecognized and unpaid, which is a major concern for radical feminists

(Enns, 2010). The stress and difficulty of coping with multiple responsibilities contribute to the

abortion decision, as expressed by Natalie who was employed, ‘‘My baby is 10 months old. I fell

pregnant too soon. Both my partner and I decided on the abortion because there was really no option

of having the baby. We didn’t want to do it but we both know that we had to.’’

Women who are HIV positive may choose not to have another child for fear of HIV transmission

to the child, their own demise, and having to leave an orphan, or that they might become too sick

during the pregnancy. This was Ruth’s concern, ‘‘I hear so many stories if you are positive. Some-

times your baby might be positive. That is why I had the abortion.’’ Ruth’s main concern was that of

her unborn, as she did not want to risk her baby contracting HIV.

Conclusion

Radical feminism has contributed to social work’s understanding of the structural dimensions of

women’s lives, and how dominant religious and cultural constructions of motherhood, pregnancy,

and marriage have contributed to women’s reproductive health decisions. While participants consid-

ered their pro-life, religious and cultural values in making the abortion decision, their immediate life

circumstances and needs, and the needs of others around them took precedence. The primary factors

contributing to the abortion decision among participants in this study were financial constraints;

unemployment; abandonment by partners; and fear and shame in view of familial, religious, and cul-

tural sanctions against pregnancy outside of marriage.

The women held life to be sacrosanct, saw the unborn as babies, and in making the choice for

abortion acted contrary to their own moral impulse. As they internalized dominant pro-life dis-

courses, all of them constructed their choices as bad, sinful, and murderous, and in doing so saw

themselves as immoral sinners and murderers. Contextual morality rooted in the feminist ethic of

care (Tronto, 1993), however, superseded their principled moral reasoning about the wrongfulness

of the abortion act. The women allowed concerns about provision for the unborn child, their respon-

sibility toward existing children, and the need to protect their families to take precedence over the

pain, suffering, and guilt that the abortion decision brought. The structural conditions that disadvan-

tage women and the dominant societal discourses, that uphold pronatalism but only within certain

defined situations, as discussed in this article, reflect an indictment on society. If reproductive health

choices, including abortion, have to be freely, safely, and legally available to women, women must

be granted the socioeconomic freedom and cultural spaces to exercise such choices.

Stemming the incidence of abortions depends on society’s ability to provide structural and cul-

tural conditions conducive enough to render women’s choices to be truly free. Expanding freedom

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

Gilbert and Sewpaul 93

and choice and reducing poverty mean prioritizing access to education and gainful employment and

the introduction of a basic income grant, which social workers have been actively advocating for in

South Africa (Sewpaul, 2005; Triegaardt, 2008). Social work educators, researchers, and practi-

tioners have important roles to play in advocating for structural changes and in lobbying for policies

that allow women expanded freedom and choice. They must also engage policy makers, students,

colleagues, and the community at large, in challenging gender inequality and the taken-for-

granted assumptions about gender roles (Sewpaul, 2013b) that place an inordinate responsibility

on women for childbearing and child rearing, and in getting men to embrace the ethic of care and

responsibilities of fatherhood.

Adopting Freirian–Gramscian strategies (Freire, 1970, 1973; Gramsci, 1971), social workers

can engage people in consciousness raising exercises, use popular media to heighten awareness,

and they can challenge and mobilize communities to confront the double standards of a society

that revere motherhood and children but condemns women for becoming pregnant in less than

socially determined ideal circumstances and more importantly challenge societies that ostracize

and label children as ‘‘unwanted bastards.’’ The most felicitous start to life, after all, is being born

a wanted and loved child.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or

publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Adamczyk, A. (2009). Understanding the effects of personal and school religiousity on the decision to abort a

premarital pregnancy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50, 180–195.

Bauman, Z. (1993). Postmodern ethics, Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing.

Beauchamp, T. L. (1991). Philosophical ethics: An introduction to moral philosophy. New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill.

Bond, P. (2005). Elite transition: From apartheid to neoliberalism in South Africa. Scottsville, South Africa:

University of KwaZulu-Natal Press.

Buchmann, C., & Hannum, E. (2001). Education and stratification in developing countries: A review of theories

and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 77–102.

Cannold, L. (1998). The abortion myth: Feminism, morality, and the hard choices women make. New South

Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Chaykowski, K. (2012). In South Africa, a grassroots battle on baby abandonment. The Wall Street Journal.

Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304065704577424314099355038.html

Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996. Government Gazette No. 1891. Retrieved from http://

www.info.gov.za/view/DownloadFileAction?id¼66711

Cohen, L., & Manion, L. (1994). Research methods in education. London, England: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design. London, England: Sage.

Dickerson, V. (2013). Patriarchy, power, and privilege: A narrative post-structural view of work with couples.

Family Process, 52, 102–114.

Dominelli, L. (2012). Claiming women’s places in the world: Social workers role in eradicating gender inequal-

ity globally. In L. M. Healy & R. J. Link (Eds.), Handbook of international social work: Human rights,

development, and the global profession (pp 63–72). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Doucet, A. (2000). ‘There’s a huge gulf between me as a male carer and women’: Gender, domestic responsi-

bility, and the community as an institutional arena. Community, Work & Family, 3, 163–184.

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

94 Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work 30(1)

Ekstrand, M., Tydén, T., Darj, E., & Larsson, M. (2009). An illusion of power: Qualitative perspectives on abor-

tion decision-making among teenage women in Sweden. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health,

41, 173–180.

Engelbrecht, M. C. (2005). Termination of pregnancy policy and services: An appraisal of the implementation

and operation of the Choice of Termination of Pregnancy Act (92 of 1996). PhD, University of the Free

State. Retrieved from http://etd.uovs.ac.za/ETD-db//theses/available/etd-08212006-132756/unrestricted/

EngelbrechtMC.pdf

Enns, C. Z. (2010). Locational feminisms and feminist social identity analysis. Professional Psychology:

Research and Practice, 41, 333–339.

Fairclough, N. (2009). A dialectical-relational approach to critical discourse analysis in social research. In R.

Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis. London, England: Sage.

Finer, L. B., Frohwirth, L. F., Dauphinee, L. A., Singh, S., & Moore, A. M. (2005). Reasons U.S. women have

abortions: Quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 37,

110–118.

Freire, P. (1970). The pedagogy of the oppressed. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books.

Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness. New York, NY: Seabury Press.

Gillespie, R. (2003). Childfree and feminine: Understanding the gender identity of voluntarily childless women,

Gender & Society, 17, 122–136.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks. In A. Hoare & G. N. Smith (Eds. & Trans.). London,

England: Lawrence & Wishart.

Hilton, A. (2007). The different religions’ views on abortion. Retrieved from http://www.helium.com/items/

716202-the-different-religions-views-on-abortion

Human Sciences Research Council (2004) Media release: Rights or wrongs? Public attitudes towards moral

values. Retrieved August 14, 2014, from http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pages/1278/September%202004.

pdf

IASSW/IFSW (2014). Proposed new global definition of social work. Retrieved from http://www.iassw-aiets.

org/nidofsw-20140221

Jelen, T. G., & Wilcox, C. (2003). Causes and consequences of public attitudes toward abortion: A review and

research agenda. Political Research Quarterly, 56, 489–500.

Johnston, R. W. (2013). Historical abortion statistics, South Africa. Retrieved from http://www.johnstonsarc-

hive.net/policy/abortion/ab-southafrica.html

Jones, R. K., Frohwirth, L. F., & Moore, A. M. (2007). I would want to give my child, like everything in the

world: How issues of motherhood influence women who have abortions. Journal of Family Issues, 29,

79–99.

Kaye, D. K., Mirembe, F. M., Bantebya, G., Johansson, A., & Ekstrom, A. M. (2006). Domestic violence as risk

factor for unwanted pregnancy and induced abortion. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 2,

90–101.

Kingdom, G. G., & Knight, J. (2004). Race and the incidence of unemployment in South Africa. Review of

Development Economics, 8, 198–222.

Klasen, S. (2002). Low schooling for girls, slower growth for all: Cross-country evidence on the effect of gen-

der inequality in education on economic development. The World Bank Economic Review, 16, 345–373.

Mappes, T. A., & Zembaty, J. S. (1997). Social ethics: Morality and social policy. New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill.

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/

bastard

Reardon, D. C. (2002). Aborted women: Silent no more. Springfield, MA: Acorn.

Richter, L., & Morrell, R. (2006). An introduction. In L. M. Richter & R. Morrell (Eds.), Baba: Men and

fatherhood in South Africa (1–12). Cape Town, South Africa: HSRC Press.

Saul, J. M. (2003). Feminism: Issues and arguments. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

Gilbert and Sewpaul 95

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (2005). The argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian culture, history and identity. London, England:

Penguin Books.

Sewpaul, V. (1999). Culture, religion and infertility: A South African perspective. British Journal of Social

Work, 29, 741–754.

Sewpaul, V. (2005). A structural social justice approach to family policy: A critique of the draft South African

Family Policy. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 41, 310–322.

Sewpaul, V. (2013a). Neoliberalism and social work in South Africa, Critical and Radical Social Work, 1,

15–30.

Sewpaul, V. (2013b). Inscribed in our blood: Confronting and challenging the ideology of sexism and racism.

Affilia: The Journal of Women and Social Work, 28, 116–125.

Smith, A. (2005). Beyond pro-choice versus pro-life: Women of color and reproductive justice. NWSA Journal,

17, 119–140.

South Africa Yearbook. (2010, 2011). Retrieved from www.gcis.gov.za/sites/www.gcis.gov.za/files/docs/

resourcecentre/yearbook/chapter1.pdf

Statistics South Africa. (2012). Labour statistics. Retrieved from http://www.statssa.gov.za/keyindicators/key-

indicators.asp

Trading Economics. (2012). Unemployment with primary education; female unemployment in South Africa.

Retrieved from http://www.tradingeconomics.com/south-africa/unemployment-with-primary-education-

female-percent-of-female-unemployment-wb-data.html

Triegaardt, J. D. (2008). Globalisation: What impact and opportunities for the poor and unemployed in South

Africa. International Social Work, 51, 480–492.

Tronto, J. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care. New York, NY: Routledge.

Trybulski, J. (2005). The long-term phenomena of women’s post-abortion experiences. Western Journal of

Nursing Research, 27, 559–576.

Vavi, Z. (2012, February 12). What we must do to create jobs in South Africa. Sunday Times.

Vukelić, J., Kapamadzija, A., & Kondrić, B. (2010). Investigation of risk factors for acute stress reaction fol-

lowing induced abortion. Medicinski Pregled, 63, 399–403.

Whitehead, A., & Fanslow, J. (2005). Prevalence of family violence amongst women attending an abortion

clinic in New Zealand. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 45, 321–324.

Williams, J. C., & Shames, S. L. (2004). Mother’s dreams: Abortion and the high price of motherhood. Journal

of Constitutional Law, 6, 818–842.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2009). Critical discourse analysis: History, agenda, theory and methodology

(pp 1–33). In R. Wodak & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis. London, England: Sage.

Author Biographies

Indira Gilbert is a PhD graduate of the University of KwaZulu Natal, School of Applied Human Sciences

(Social Work) and is employed as a social worker in a special needs school in Durban. She is the vice chair

of the South African Association of Social Workers in Private Practice, KwaZulu Natal branch.

Vishanthie Sewpaul, PhD, is a Senior Professor in the School of Applied Human Sciences (Social work) at the

University of KwaZulu Natal. She is the president of the Association of Schools of Social Work in Africa and

vice president on the Board of the International Association of Schools of Social Work.

Downloaded from aff.sagepub.com by guest on August 9, 2016

You might also like

- The Turnaway Study: The Cost of Denying Women Access to AbortionFrom EverandThe Turnaway Study: The Cost of Denying Women Access to AbortionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- Pearlin The Sociological Study of StressDocument17 pagesPearlin The Sociological Study of StressTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Towards Self Reconstruction: A Grounded Theory Study Among Women Separated From Abuaive RelationshipDocument107 pagesTowards Self Reconstruction: A Grounded Theory Study Among Women Separated From Abuaive RelationshipJana SilvaNo ratings yet

- Feminist CareDocument3 pagesFeminist Carelily bloomNo ratings yet

- Creating, Maintaining and Questioning (Hetero) Relational Normality in Narratives About Vaginal ReconstructionDocument28 pagesCreating, Maintaining and Questioning (Hetero) Relational Normality in Narratives About Vaginal ReconstructionNunuh SulaemanNo ratings yet

- Swan 2020Document16 pagesSwan 2020ZtteffyNo ratings yet

- Feminist Theory and Queer Theory: Implications For HRD Research and PracticeDocument12 pagesFeminist Theory and Queer Theory: Implications For HRD Research and PracticeAlbin Sj SasserilNo ratings yet

- The Interacting Roles of Abortion Stigma and Gender On Attitudes Towardabortion LegalityDocument6 pagesThe Interacting Roles of Abortion Stigma and Gender On Attitudes Towardabortion LegalitykrajcevskaaNo ratings yet

- Debate On Abortion: A Feminist Argument: L. Bishwanth SharmaDocument6 pagesDebate On Abortion: A Feminist Argument: L. Bishwanth SharmaImpact JournalsNo ratings yet

- To Abort or Not Abort - The Ethics of Decriminalizing AbortionDocument7 pagesTo Abort or Not Abort - The Ethics of Decriminalizing AbortionescritoragibassoNo ratings yet

- Conceptulising StigmaDocument16 pagesConceptulising StigmaRitesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Hbse II Policy Paper FinalDocument11 pagesHbse II Policy Paper Finalapi-637050088No ratings yet

- Ecofeminism EssayDocument7 pagesEcofeminism EssayAsisipho Onela MvanaNo ratings yet

- IPAS - Focus Groups For Exploring StigmaDocument24 pagesIPAS - Focus Groups For Exploring StigmaServicios Integrales en Psicología ForenseNo ratings yet

- Agarwal, B 1992 TheGenderAndEnvironmentDebateDocument41 pagesAgarwal, B 1992 TheGenderAndEnvironmentDebateSipokazi NongauzaNo ratings yet

- Trabajo Social Cualitativo 2016 FraserDocument16 pagesTrabajo Social Cualitativo 2016 FrasermhidalgochNo ratings yet

- The Rush To MotherhoodDocument39 pagesThe Rush To MotherhoodHèliaNo ratings yet

- The Gender of Pregnancy Masculine Lesbians Talk About ReproductionDocument16 pagesThe Gender of Pregnancy Masculine Lesbians Talk About ReproductionThePoliticalHatNo ratings yet

- Starving Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have'Document16 pagesStarving Is The Most Fun A Girl Can Have'Criis OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Decriminalization of Sex Work, Feminist Discourses in Light of Research PDFDocument35 pagesDecriminalization of Sex Work, Feminist Discourses in Light of Research PDFRenata AtaideNo ratings yet

- Women Speech EmpowermentDocument27 pagesWomen Speech Empowermentsoc2003No ratings yet

- HannahDocument47 pagesHannahapi-460767991No ratings yet

- Freedom of Religion Women S Agency and Banning The Face Veil The Role of Feminist Beliefs in Shaping Women S OpinionDocument17 pagesFreedom of Religion Women S Agency and Banning The Face Veil The Role of Feminist Beliefs in Shaping Women S Opinionyasir iqbalNo ratings yet

- Murphy UnsettlingcareTroubling 2015Document22 pagesMurphy UnsettlingcareTroubling 2015Christina GrammatikopoulouNo ratings yet

- WomenEmpPersViews PDFDocument8 pagesWomenEmpPersViews PDFManish KumarNo ratings yet

- Female Circumcision Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesFemale Circumcision Literature Reviewaflspwxdf100% (1)

- Idk Nah p2Document18 pagesIdk Nah p2kachaymarcano07No ratings yet

- The Transition To NonparenthoodDocument23 pagesThe Transition To NonparenthoodEstefania DiazNo ratings yet

- Dualisms and Female Bodies in Representations of African Female CircumcisonDocument23 pagesDualisms and Female Bodies in Representations of African Female CircumcisoniamnotsupermanhahahaNo ratings yet

- Enacting MasculinitiesDocument11 pagesEnacting MasculinitiesIvan ViramontesNo ratings yet

- Abortion: Feminist Perspectives On Moral PhilosophyDocument3 pagesAbortion: Feminist Perspectives On Moral PhilosophyУльяна МорозоваNo ratings yet

- Joseph - Ethics - InterimDocument3 pagesJoseph - Ethics - InterimJoseph DarwinNo ratings yet

- Black Women and Choice Theory Reality TherapyDocument12 pagesBlack Women and Choice Theory Reality TherapyMiKael AshantiNo ratings yet

- Agarwal 1992Document41 pagesAgarwal 1992DHRUV KAYESTHNo ratings yet

- Ed 11-Feminism AeDocument25 pagesEd 11-Feminism Aeuri wernukNo ratings yet

- Sophia RDocument3 pagesSophia Rapi-456983151No ratings yet

- Victoria's Dirty SecretDocument15 pagesVictoria's Dirty SecretDesiree Grace Tan-LinNo ratings yet

- ZQ - Analytical Essay - 227732259.doc X: File File 1 1Document10 pagesZQ - Analytical Essay - 227732259.doc X: File File 1 1erikajaneNo ratings yet

- Feminist Dissertation TopicsDocument7 pagesFeminist Dissertation TopicsUK100% (1)

- Doing Narrative Feminist Research: Intersections and ChallengesDocument15 pagesDoing Narrative Feminist Research: Intersections and ChallengesACNNo ratings yet

- What Is Feminist ResearchDocument12 pagesWhat Is Feminist ResearchCrista AbreraNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Female CircumcisionDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On Female Circumcisionaflbrpwan100% (1)

- Fetal Relationality in Feminist Philosophy-An Anthropological CritiqueDocument25 pagesFetal Relationality in Feminist Philosophy-An Anthropological CritiqueanjcaicedosaNo ratings yet

- The Media's Sexual Objectification of Women, Rape Myth Acceptance, and Interpersonal ViolenceDocument20 pagesThe Media's Sexual Objectification of Women, Rape Myth Acceptance, and Interpersonal ViolenceJeda AthifaNo ratings yet

- Lit Review2Document10 pagesLit Review2api-341202764No ratings yet

- Feminist Theory Research PaperDocument8 pagesFeminist Theory Research Paperpukjkzplg100% (1)

- Juan Carlos Muhi Concept Paper AwDocument5 pagesJuan Carlos Muhi Concept Paper Awjc muhiNo ratings yet

- Thesis Paper On TransgenderDocument5 pagesThesis Paper On TransgenderKaren Gomez100% (2)

- Feminist Standpoint TheoryDocument7 pagesFeminist Standpoint TheoryClancy Ratliff100% (1)

- Violence Against Women in The Age of PostfeminismDocument20 pagesViolence Against Women in The Age of PostfeminismAdentro y afuera, Una Ventana Al arteNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation Research Paper OutlineDocument8 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation Research Paper Outlinegz9p83dd100% (1)

- Fem IR K - Michigan7 2014Document52 pagesFem IR K - Michigan7 2014DerekNo ratings yet

- Aalborg Universitet: Walby, SylviaDocument25 pagesAalborg Universitet: Walby, SylviaishikaNo ratings yet

- Final Output (Dalida, Shaina)Document5 pagesFinal Output (Dalida, Shaina)Shaina DalidaNo ratings yet

- Varda Muhlbauer, Joan C. Chrisler, Florence L. Denmark Eds. Women and Aging An International, Intersectional Power PerspectiveDocument182 pagesVarda Muhlbauer, Joan C. Chrisler, Florence L. Denmark Eds. Women and Aging An International, Intersectional Power PerspectivePaz Troncoso100% (1)

- Medical Entanglements: Rethinking Feminist Debates about HealthcareFrom EverandMedical Entanglements: Rethinking Feminist Debates about HealthcareNo ratings yet

- Reinscribing The Birthing Body:: Homebirth As Ritual PerformanceDocument24 pagesReinscribing The Birthing Body:: Homebirth As Ritual PerformanceAnaNo ratings yet

- SelgaDocument3 pagesSelgajheaangelapNo ratings yet

- Feminist Theory Amerol Camama Cariga Pagaura Pangcatan HandoutsDocument11 pagesFeminist Theory Amerol Camama Cariga Pagaura Pangcatan HandoutsAsnia Sarip100% (1)

- Creative Final 3Document5 pagesCreative Final 3api-718614660No ratings yet

- Important During Acute HospitalisationDocument13 pagesImportant During Acute HospitalisationTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Health Insurance in GermanyDocument4 pagesHealth Insurance in GermanyTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- ვაქცინაცია სტუდებტებშDocument6 pagesვაქცინაცია სტუდებტებშTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- მშობლების უარი ბავშვების ვაქცინაციაზეDocument7 pagesმშობლების უარი ბავშვების ვაქცინაციაზეTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Ejm 47374 Original - Article PurutDocument7 pagesEjm 47374 Original - Article PurutTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- ReviuDocument8 pagesReviuTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy Among Primary Healthcare Workers in SingaporeDocument9 pagesCOVID-19 Vaccine Acceptance and Hesitancy Among Primary Healthcare Workers in SingaporeTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: Journal of Affective DisordersDocument20 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: Journal of Affective DisordersTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Does Insurance Market Activity Promote Economic GrowthDocument27 pagesDoes Insurance Market Activity Promote Economic GrowthTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- სტუდენტების ცოდნა კოვიდ 19Document13 pagesსტუდენტების ცოდნა კოვიდ 19Tengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- IDU062 B 1Document62 pagesIDU062 B 1Tengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Employment As Experienced by Disabled People: A Qualitative Analysis in Calgary and Regina, CanadaDocument15 pagesBarriers To Employment As Experienced by Disabled People: A Qualitative Analysis in Calgary and Regina, CanadaTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- The Use of Telephone Consultation in Primary Health Care During COVID-19 PandemicDocument8 pagesThe Use of Telephone Consultation in Primary Health Care During COVID-19 PandemicTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Access To Employment in Kenya: The Voices of Persons With DisabilitiesDocument11 pagesAccess To Employment in Kenya: The Voices of Persons With DisabilitiesTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Hearing Loss Within A Marriage Perceptions of The Spouse With Normal HearingDocument8 pagesHearing Loss Within A Marriage Perceptions of The Spouse With Normal HearingTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Health Care Market Deviations From The Ideal MarkeDocument11 pagesHealth Care Market Deviations From The Ideal MarkeTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Change Management in An Environment of Ongoing Primary Health Care System Reform A Case Study in AustraliaDocument13 pagesChange Management in An Environment of Ongoing Primary Health Care System Reform A Case Study in AustraliaTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Preoperative Mood Disorders in Patients Undergoing Cardiac SurgeryDocument6 pagesPreoperative Mood Disorders in Patients Undergoing Cardiac SurgeryTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- 4 McDonald Hernandez McDonald Et Al ERRJ 2008Document8 pages4 McDonald Hernandez McDonald Et Al ERRJ 2008Tengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Leadership Styles of Military Hospital ManagersDocument7 pagesLeadership Styles of Military Hospital ManagersTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction Among Public Sector PhyDocument94 pagesJob Satisfaction Among Public Sector PhyTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- FMPCR Art 42280-10Document6 pagesFMPCR Art 42280-10Tengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- RH BillDocument23 pagesRH BillArah Obias CopeNo ratings yet

- Legaledge Test SeriesDocument40 pagesLegaledge Test SeriesSaurabhNo ratings yet

- Draft IRR For RA 10354 v2.1Document56 pagesDraft IRR For RA 10354 v2.1CBCP for LifeNo ratings yet

- G10 ActivityDocument7 pagesG10 ActivityElaina Duarte-SantosNo ratings yet

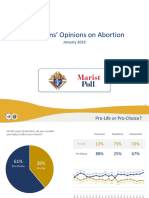

- 2023 Kofc Marist Poll PresentationDocument14 pages2023 Kofc Marist Poll PresentationVeronica SilveriNo ratings yet

- R.A. 10354Document36 pagesR.A. 10354Donzzkie Don100% (5)

- An Overview of AbortionDocument60 pagesAn Overview of AbortionDivisi FER MalangNo ratings yet

- Arguments Against AbortionDocument3 pagesArguments Against AbortionAnne McCoys Burger LumumbaNo ratings yet

- Abortion in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesAbortion in The PhilippinesRosario Antoniete R. Cabilin100% (1)

- University of The Free State Main Test 2 Marking Guide Public Law ASSESSOR: MR K B Motshabi Internal Moderator: DR C Vinti Time: 90 Minutes MarksDocument3 pagesUniversity of The Free State Main Test 2 Marking Guide Public Law ASSESSOR: MR K B Motshabi Internal Moderator: DR C Vinti Time: 90 Minutes Marksnomfundo ngidiNo ratings yet

- Appropriation of EvilDocument34 pagesAppropriation of EvilThằng ThấyNo ratings yet

- Article 257 Unintentional AbortionDocument2 pagesArticle 257 Unintentional AbortionDanica RojalaNo ratings yet

- Pro-Choice Violence in OntarioDocument16 pagesPro-Choice Violence in OntarioHuman Life InternationalNo ratings yet

- Scientific Conference Placenta LakeDocument18 pagesScientific Conference Placenta LakeAlhafiz KarimNo ratings yet

- Prostitution and The Bases: A Continuing Saga of ExploitationDocument13 pagesProstitution and The Bases: A Continuing Saga of ExploitationAida F. SantosNo ratings yet

- Abortion 1st ReferanceDocument61 pagesAbortion 1st ReferancekevinNo ratings yet

- The Economist 23 MarDocument362 pagesThe Economist 23 MarMaryam AzizNo ratings yet

- ANM SyllabusDocument9 pagesANM SyllabusMonica ZineNo ratings yet

- BibliographyDocument3 pagesBibliographyKim Andrei Estrella ApeñaNo ratings yet

- Ap Lang Synthesis EssayDocument2 pagesAp Lang Synthesis Essayapi-319010818No ratings yet

- G3 - BioethicsDocument14 pagesG3 - BioethicsKea GuirreNo ratings yet

- ABORTIONDocument4 pagesABORTIONDave DaviesNo ratings yet

- Abortion EssayDocument3 pagesAbortion EssayAndrew BennettNo ratings yet

- Abortion Position PaperDocument4 pagesAbortion Position Paperapi-306698224No ratings yet

- Crimes Against Women TribunalDocument204 pagesCrimes Against Women TribunalΕλεάνα Μπαϊράμογλου100% (1)

- Biology PaperDocument3 pagesBiology Paperapi-241209265No ratings yet

- Population Control Agenda by Stanley K Monteith, M DDocument12 pagesPopulation Control Agenda by Stanley K Monteith, M Ddebs59No ratings yet

- 5th Circuit Abortion DecisionDocument22 pages5th Circuit Abortion DecisionLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Personnel ManualDocument677 pagesPersonnel ManualdjanakiNo ratings yet

- Caribbean Examination Council Social StudesDocument28 pagesCaribbean Examination Council Social StudesJoel SamuelsNo ratings yet