Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Community and International Nutrition

Community and International Nutrition

Uploaded by

rafrejuOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Community and International Nutrition

Community and International Nutrition

Uploaded by

rafrejuCopyright:

Available Formats

Community and International Nutrition

Arctic Indigenous Peoples Experience the Nutrition Transition with

Changing Dietary Patterns and Obesity1–3

H. V. Kuhnlein,*†4 O. Receveur,* ** R. Soueida,* and G. M. Egeland*†

*Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and Environment (CINE) and †School of Dietetics and Human

Nutrition, McGill University, Ste. Anne de Bellevue, Canada; and **Department of Nutrition,

University of Montreal, Montreal, Canada

ABSTRACT Indigenous Peoples globally are part of the nutrition transition. They may be among the most extreme

for the extent of dietary change experienced in the last few decades. In this paper, we report survey data from 44

representative communities from 3 large cultural areas of the Canadian Arctic: the Yukon First Nations, Dene/Métis,

and Inuit communities. Dietary change was represented in 2 ways: 1) considering the current proportion of

traditional food (TF) in contrast to the precontact period (100% TF); and 2) the amount of TF consumed by older

vs. younger generations. Total diet, TF, and BMI data from adults were investigated. On days when TF was

consumed, there was significantly less (P ⬍ 0.01) fat, carbohydrate, and sugar in the diet, and more protein, vitamin

A, vitamin D, vitamin E, riboflavin, vitamin B-6, iron, zinc, copper, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium,

and selenium. Vitamin C and folate, provided mainly by fortified food, and fiber were higher (P ⬍ 0.01) on days

without TF for Inuit. Only 10 –36% of energy was derived from TF; adults ⬎ 40 y old consistently consumed more

(P ⬍ 0.05) TF than those younger. Overall obesity (BMI ⱖ 30 kg/m2) of Arctic adults exceeded all-Canadian rates.

Measures to improve nutrient-dense market food (MF) availability and use are called for, as are ways to maintain

or increase TF use. J. Nutr. 124: 1447–1453, 2004.

KEY WORDS: ● indigenous peoples ● nutrition transition ● dietary change ● Arctic Canada

● traditional food

Indigenous Peoples are recognized as having unique social, in food availability and receding famine, increases in non-

cultural, and health needs, often within larger mainstream communicable disease, and shifts to decreasing physical

societies to which they are expected to adapt. Whether Indig- activity and increasing use of processed food high in starch,

enous Peoples live concentrated on reservations, integrated fat, and sugar (4). Upward trends in obesity seen in LDCs

within populations of their countries, or maintain residence in have been linked to genetics, malnutrition in fetal and

large territories under their control, they strive to maintain young child development, and poor dietary patterns and

close cultural ties to land and nature, and the resources they lifestyle factors later in life (5,6). Female gender, degree of

provide (1–3). This integration invariably associates use of urbanization, education, and income are all associated with

traditional food (TF)5 resources and other cultural practices increasing obesity, and the chronic disease correlates of

with health. obesity. Uauy et al. (7) described the extent of obesity and

The nutrition transition taking place in less-developed metabolic complications by gender among rural and urban

countries (LDCs) is now widely documented, with changes Mapuche and Aymara Indigenous People in Chile, demon-

strating that being female and living in urban areas in-

1

Presented in part at Experimental Biology 02, April 2002, New Orleans, LA

creased the risk.

[Kuhnlein, H. V., Receveur, O. & Soueida, R. (2002) Nutrition transition in the Several health researchers refer to an epidemiologic tran-

Canadian Arctic: traditional food and dietary energy as indicators and determi- sition for LDCs and Aboriginal People in developed countries.

nants of change. FASEB J. 16: A616 (abs.)] and at the Canadian Federation of

Biological Societies, June 2002, Montreal, Canada [Kuhnlein, H. V., Receveur, O.,

They describe reflection and study on national communicable

Soueida, R. & Egeland G. M. (2002) Arctic dietary change, use of Indigenous and noncommunicable disease patterns, life expectancy, and

Peoples’ traditional food, and increasing obesity. Proceedings of the 45th Annual other vital statistics (8 –12). For Indigenous Peoples, health

Meeting of the Canadian Federation of Biological Societies, Abstract F066].

2

Some data for the Dene/Métis were adapted from Ref. 21.

patterns are often disparate from the national norms, if in fact

3

Supported by the Arctic Environmental Strategy and the Northern Contam- it is possible to disaggregate health data by cultural subgroups

inants Program (Canada), as well as the Canadian Institutes of Health Research within a population. Ethnicity together with poverty are often

(CIHR), Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes (INMD), and the Institute of

Aboriginal Peoples’ Health (IAPH). key determinants of poor health. As part of the International

4

To whom correspondence should be addressed. Decade of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, the WHO has led

E-mail: harriet.kuhnlein@mcgill.ca.

5

the call for development of methods to identify and compile

Abbreviations used: CINE, Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition and

Environment; LDC, less-developed country; LSM, least-square means; MF, mar- health information at national and district levels to identify

ket food; NWT, Northwest Territories; TF, traditional food. marginalized populations by their cultural identity, and to seek

0022-3166/04 $8.00 © 2004 American Society for Nutritional Sciences.

Manuscript received 7 November 2003. Initial review completed 12 January 2004. Revision accepted 23 March 2004.

1447

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jn/article-abstract/134/6/1447/4688754

by guest

on 28 March 2018

1448 KUHNLEIN ET AL.

new strategies for understanding and influencing health deter- Research took place during 2 seasons, a season of high TF use

minants for these special populations (13). (September–November) and a season of low TF use (February–

In Canada, research to understand issues specifically for April). Interviews included 24-h recalls, a food-frequency interview

Indigenous Peoples has been developing steadily, with recog- (TF only), a sociocultural interview, and a 7-d food record (Inuit

nition that trends in Indigenous Peoples’ health parallel those communities only). This report emphasizes information from 24-h

recall and frequency interviews, and height and weight data from men

in national data from LDCs (14,15). Increasing obesity and and nonpregnant or lactating women ⱖ 20 y old. Interviews were

changing health lifestyles for circumpolar Inuit have been conducted in Denendeh during 1994, in Yukon during 1995, and in

noted (16 –18). Dietary patterns researched among Canadian Inuit communities in 1998 –1999. Each cultural group (Dene/Métis,

Arctic peoples point to the high quality of foods taken from Yukon, Inuit) study was reviewed separately by the McGill University

animal and plant species of hunter-gatherer subsistence pat- Human Ethics Committee, and each community maintained a re-

terns still recognized by Dene/Métis, Yukon First Nations, and search agreement with CINE to ensure completion of procedures

Inuit communities (19 –23). Arctic TF is understood to be using locally resident research assistants. Collective consent was

animal and plant species culturally identified as food and obtained from the Council of Yukon First Nations, Dene Nation,

harvested from the local environment, whereas market food Métis Nation of the NWT, and the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. Science

(MF) is that shipped from the South and purchased in stores licenses were obtained from the territorial authorities. The research

(24). Techniques to delineate dietary components by TF and also included sampling of TF used in homes for analysis of nutrients

and other components, when needed for dietary analysis. Results of

MF were used successfully to understand nutritional and cul- these analyses were reported separately (30 –33).

tural benefits in contrast to contaminant risks of TF in the Random sampling of 10% of households was done using commu-

context of the total diet (21,23,25). However, data on TF and nity household or utility lists; in smaller communities, all households,

MF use that are generalizable to the entire Canadian Arctic up to a maximum of 25 households, were interviewed. In each

are not currently available. household, 1 adult man and 1 adult woman were selected by conve-

As part of the research program of the Northern Contam- nience and interviewed. In Inuit communities, interviews were also

inants Program of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, we conducted with 1 adolescent aged 13–19 y, when available (data not

conducted studies on dietary intake from 44 communities of included). In the absence of an adult man or woman in the home,

Indigenous Peoples over a 10-y period in 3 major cultural areas another random household was contacted. The interviewing season

in the Canadian Arctic.6 Research partnerships were devel- was selected to avoid periods of mass absence of community members

oped with communities through leadership within the Gov- due to intensive hunting or fishing. Participation was voluntary and

confidential, conducted in English or the traditional language, and

erning Board of the Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition interviewers were trained in confidential process. In each community,

and Environment (CINE). To devise consistent research strat- a project coordinator trained in the research methodology, usually a

egies and participatory research technique, we worked closely nutrition graduate, supervised the interviews conducted for complete-

with the collective aboriginal organizations of the regions: ness and data entry. Having the research coordinator on site fre-

Dene Nation, Métis Nation of the Northwest Territories quently to screen completed interviews ensured quality control. In-

(NWT), Council of Yukon First Nations, and the Inuit Ta- terviews on 24-h food intake were conducted in the homes of the

piriit Kanatami. Results of these studies were reported back to participants. Interviewers used portion models (prepared from locally

the organizations and the communities using workshops, post- available bowls, cups and spoons), a two-dimensional drawing of

ers, and media interviews, as recognized for good participatory bannock (the frequently consumed homemade bread), and a note-

technique (26). Partial results from the Dene/Métis segment of book of TF photos with local names to prompt recognition. Fre-

this effort were published earlier (21,22). This paper presents quency of TF use was captured with an instrument developed in close

consultation in workshops with representatives from each commu-

TF, MF, and nutrient intakes by age and gender for these 3 nity. Individuals were asked how many days each week the food was

cultural groups in the Canadian Arctic, and BMI correlates of consumed, without portion size. Participation exceeded 90% of indi-

diet for Yukon and Inuit. Estimations of contemporary nutri- viduals contacted for Dene/Métis and Yukon First Nations commu-

ent inadequacy will be reported separately. The extent of the nities, and ⬎75% for communities in the 5 Inuit regions. These high

nutrition transition is represented as the percentage of TF participation rates were due to publicity and encouragement by the

energy (in contrast to 100% TF at the turn of the century, collective leadership organizations (Dene Nation, Métis Nation of

before influx of food stores), and as the contrasting amounts of NWT, Council of Yukon First Nations, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami). The

TF consumed by young (20 – 40 y), middle-aged (41– 60 y) and interview process and materials were consistent in all 3 major studies.

elder (⬎60 y) adults. Due to the prohibition of alcohol consumption in some communities,

alcohol intake was recorded when the information was reported in

24-h recall interviews, but it was not probed. Participants were asked

SUBJECTS AND METHODS whether the day was “usual” or not, including special occasions.

The vast territories of Arctic Canada whose Indigenous Peoples and Records were discarded when energy intakes were ⫾4 SD from the

TF resources are the subject of this report are Yukon Territory (483,450 mean.

km2), the NWT (1,171,918 km2), Nunavut (2,093,190 km2), and La- For the Yukon and Inuit studies, heights and weights were either

brador (294,330 km2). Ten Yukon First Nations, 16 Dene/Métis com- reported or measured, if the respondents did not know their own data.

munities in the NWT, and 18 Inuit communities in the NWT, Nu- Weight measurements were taken in light clothing without shoes

navut, and Labrador were selected by the aboriginal organizations to using ordinal personal scales (precision ⫾ 100 g) tared to zero. Height

represent the breadth of TF system environments in their regions. These measurements were taken with rigid vertical tape to the nearest 0.5

3 major cultural areas represent the major language families of Athapas- cm. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared

kan (10 language groups in Yukon First Nations and Denendeh), Tlingit (m2). There were no significant differences between self-reported and

(Yukon), Eyak (Yukon), and Inuktitut (Inuvialuktun in the NWT). In measured weights, heights, or BMI for subsamples of participant

all, the research represents populations of 7000 Yukon First Nations, volunteers in the Yukon and Inuit studies, and all measures and

18,000 Dene/Métis, 24,000 Inuit in Nunavut, 5000 Inuvialuit in the self-reported data were in good agreement (not shown).

NWT, and 4500 Inuit in Labrador. This comprises 58,500 of Canada’s Two food composition databases were used for nutrient intake

Aboriginal People6 (27–29). analyses: 1) a TF database derived from our own published work on

Arctic TF (30 –38), and 2) a MF database (39) derived from Agri-

culture Handbook 8, adjusted to Canadian nutrient fortification

6

Supplement Appendix Figure 1, a map of surveyed communities, is available levels. The carotenoid content of foods was updated (40). In addition,

with the online posting of this paper at www.nutrition.org. the MF database was fine-tuned for recent requirements of dietary

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jn/article-abstract/134/6/1447/4688754

by guest

on 28 March 2018

DIETARY CHANGE AMONG ARCTIC INDIGENOUS PEOPLES 1449

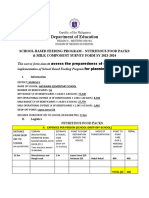

TABLE 1 40-y-old age group, men consumed more TF than did women,

and this pattern occurred in the 41- to 60-y-old age group for

Top 16 market foods mentioned in 24-h recalls of Yukon, Inuit. Other than these, there were no differences between

Dene/Métis, and Inuit adults in 44 representative communities genders among the cultural age groups. Mean intake of all TF

from 3 large cultural areas of the Canadian Arctic1 was ⬎100 g/d, and for older individuals, could exceed 400 g/d

(Fig. 1). Because many individuals did not consume TF on the

Yukon Dene/Métis Inuit days interviewed, intakes of TF derived from the 24-h recalls

Food item (n ⫽ 797) (n ⫽ 1007) (n ⫽ 1604)

Sugar2 72 82 74

Coffee2 77 76 63

Tea2 47 59 53

Bread, white, enriched2 43 64 50

Potatoes, baked, boiled or mashed 42 42 26

Butter 43 45 22

Eggs 37 42 18

Cream, light or powdered 18 42 30

Margarine 17 24 27

Rice, white, enriched 32 20 21

Milk, evaporated 21 21 19

Chicken, all types 15 21 16

Hamburger, beef 17 14 16

Lard 25 45 12

Crystal drinks 11 29 34

Bannock3 7 27 20

1 Percentage of recalls that mentioned the food item. Items in each

recall were compiled as a sum for the day (1 mention maximum per

recall).

2 Top 4 items in all 3 surveys.

3 A quickbread similar to a biscuit.

reference intake procedures (41), and new nutrient data reported by

the USDA (42). There were no missing nutrient values in either data

base.

Data are reported from 1007 interviews of Dene/Métis, 797 inter-

views of Yukon First Nations, and 1604 of Inuit. BMI data from 375

Yukon adults and 960 Inuit are reported. In each study, data were

entered into Epi-Info, version 6 (USD). Extensive checking and

double entry of a 10% random subset were completed and analyses

were conducted with SAS, versions 6 and 8 (SAS Institute). Means

or least-square means (LSM) with SEM were compiled as descriptive

statistics. Adjusting for unbalanced sample sizes across communities,

age groups, and seasons was done using LSM. When nutrient intakes

did not meet the assumption of normality, differences between groups

were tested by Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric ANOVA (43). Bonfer-

roni multiple comparisons were used to identify significant differences

between mean values during multiple comparisons (42). All statisti-

cal analyses used P ⬍ 0.05 for the level of significance.

RESULTS

Estimates of consumption frequency by region (2-season

mean of number of days per week)7 revealed that moose,

caribou, fish (whitefish, char, trout), and seal were the most

heavily consumed TF items in all cultures and regions. Using

all 24-h recall datasets, the ranked top 16 MF in each of the 3

cultural areas were consistent across the Canadian Arctic

(Table 1). A total of ⬎200 MF items were mentioned in the

recalls; a more detailed description of MF items in food groups

frequently consumed in the Dene/Métis area is presented in

Receveur et al. (21).

In all three cultures, significantly more TF was consumed by

FIGURE 1 Traditional food intake by Yukon (A), Dene/Métis (B),

older individuals than by those younger (Fig. 1). In the 20- to and Inuit (C) men and women of different ages, adjusted for season,

site, and day of week. Total participants were considered in all regions

within each cultural area. Values are means from 2 seasons ⫾ SEM for

7

Supplement Appendix Table 1 gives frequency of TF use, and is available the n given above each bar. Means without a common letter differ, P

with the online posting of this paper at www.nutrition.org. ⬍ 0.05. *Different from men of the same age, P ⬍ 0.05.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jn/article-abstract/134/6/1447/4688754

by guest

on 28 March 2018

1450 KUHNLEIN ET AL.

TABLE 2

Micronutrient, fiber, and energy intake on days with and without traditional food (TF) for Yukon, Dene/Métis, and Inuit adults1

Yukon Dene/Métis Inuit

Days with TF Days without TF Days with TF Days without TF Days with TF Days without TF

Nutrient (n ⫽ 410) (n ⫽ 387) (n ⫽ 661) (n ⫽ 346) (n ⫽ 968) (n ⫽ 632)

Vitamin A,2 g RAE 697 ⫾ 45 523 ⫾ 52 1245 ⫾ 424 825 ⫾ 578 911 ⫾ 136a 433 ⫾ 179b

Vitamin D, g 7.3 ⫾ 0.6a 2.1 ⫾ 0.7b 7.9 ⫾ 0.9a 3.5 ⫾ 1.3b 25.1 ⫾ 1.3a 8.6 ⫾ 1.7b

Vitamin E, mg 4.8 ⫾ 0.1a 3.5 ⫾ 0.2b 6.5 ⫾ 0.4a 3.9 ⫾ 0.5b 5.4 ⫾ 0.2a 3.1 ⫾ 0.3b

Vitamin C, mg 61.8 ⫾ 5.2 68.9 ⫾ 5.9 52.6 ⫾ 4.3 60.9 ⫾ 5.9 62.1 ⫾ 3.4a 70.6 ⫾ 4.5b

Riboflavin, mg 2.2 ⫾ 0.1a 1.5 ⫾ 0.1b 2.5 ⫾ 0.1a 1.6 ⫾ 0.1b 2.9 ⫾ 0.1a 1.3 ⫾ 0.1b

Vitamin B-6, mg 3.3 ⫾ 0.1a 1.7 ⫾ 0.1b 3.7 ⫾ 0.1a 1.9 ⫾ 0.1b 4.0 ⫾ 0.1a 1.4 ⫾ 0.1b

Folate, g DFE 311 ⫾ 9 307 ⫾ 11 303 ⫾ 10 316 ⫾ 14 317 ⫾ 10a 319 ⫾ 13b

Calcium, mg 461 ⫾ 20 508 ⫾ 23 533 ⫾ 17 526 ⫾ 24 443 ⫾ 12 451 ⫾ 16

Iron, mg 23.3 ⫾ 0.6a 14.1 ⫾ 0.7b 26.5 ⫾ 0.9a 15.6 ⫾ 1.3b 37.4 ⫾ 1.1a 15.0 ⫾ 1.4b

Zinc, mg 27.7 ⫾ 0.9a 13.1 ⫾ 1.1b 23.8 ⫾ 1.0a 15.4 ⫾ 1.3b 21.5 ⫾ 0.5a 9.5 ⫾ 0.6b

Copper, g 1655 ⫾ 46a 1163 ⫾ 53b 2025 ⫾ 89a 1439 ⫾ 122b 2076 ⫾ 44a 1041 ⫾ 58b

Magnesium, mg 297 ⫾ 6a 240 ⫾ 7b 305 ⫾ 5a 237 ⫾ 7b 597 ⫾ 31a 280 ⫾ 40b

Manganese, mg 3.7 ⫾ 0.1a 3.3 ⫾ 0.1b 3.6 ⫾ 0.1a 3.3 ⫾ 0.1b 3.3 ⫾ 0.1a 2.7 ⫾ 0.1b

Phosphorus, mg 1602 ⫾ 35a 1155 ⫾ 40b 1759 ⫾ 31a 1224 ⫾ 43b 1663 ⫾ 27a 947 ⫾ 36b

Sodium, mg 2334 ⫾ 89a 2692 ⫾ 102b 2544 ⫾ 80a 3050 ⫾ 109b 2199 ⫾ 73a 2437 ⫾ 95b

Potassium, mg 3520 ⫾ 76a 2608 ⫾ 87b 3516 ⫾ 63a 2561 ⫾ 86b 2997 ⫾ 53a 1999 ⫾ 70b

Selenium, g 160 ⫾ 4a 124 ⫾ 5b 151 ⫾ 3a 132 ⫾ 5b 195 ⫾ 10a 107 ⫾ 13b

Dietary fiber, g 14.6 ⫾ 0.4 15.2 ⫾ 0.5 12.6 ⫾ 0.3 12.9 ⫾ 0.4 9.7 ⫾ 0.3a 11.2 ⫾ 0.4b

Total energy, kJ 8735 ⫾ 193 1971 ⫾ 221 9677 ⫾ 173 8759 ⫾ 236 8577 ⫾ 149a 7456 ⫾ 196b

1 Values are LSM ⫾ SEM (Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric ANOVA within each cultural area adjusted for food source, age, gender, season, site, and

day of week): means in a row with superscripts without a common letter differ, P ⬍ 0.01.

2 RAE, retinol activity equivalents; DFE, dietary folate equivalents.

of only those who consumed TF yielded a range of TF intake determined the percentage of energy from TF according to

by age and gender groups from a low of 242 g (Yukon women BMI categories for both Inuit and Yukon First Nations partic-

aged 20 – 40 y, n ⫽ 103) to a high of 567 g (Inuit men 61⫹ y, ipants (Table 4). Using the robust Bonferroni multiple com-

n ⫽ 63) (data not shown). parisons, there were no significant differences by BMI category

Dichotomizing recall data for all ages combined into those for TF use within age groups of either cultural group. Data

containing TF and those without TF8 (Table 2), days with TF showing increased TF use by age within BMI category rein-

had a consistent pattern across cultural groups. TF days had force those shown in Figure 1. Total TF percentage of energy

higher (P ⬍ 0.01) total energy and percentage of energy as varied from 10.5 ⫾ 2.0 (Yukon young women with BMI ⬍ 25

protein. Days without TF had significantly higher percentage kg/m2) to 36.0 ⫾ 4.9 (Inuit older men with BMI ⱖ 30 kg/m2).

of energy as carbohydrate, fat, sucrose, SFA, and PUFA. The Sources of energy from both TF and MF did not differ

phenomenon of TF providing significantly more nutrients was significantly by BMI category.9 The exception was for younger

emphasized. In all cultural groups, TF days contained more (P Inuit men; those in the higher BMI category consumed signif-

⬍ 0.01) vitamin D, vitamin E, riboflavin, vitamin B-6, iron, icantly more fat than those in the lower category. Cell sizes for

zinc, copper, magnesium, manganese, phosphorus, potassium, Yukon were extremely small in the high BMI categories.

and selenium. However, differences in nutrient patterns ex-

isted among the 3 groups (Table 2). Vitamin A, with consid- DISCUSSION

erable variance, differed significantly between days with and

without TF only for Inuit. Vitamin C, folate, and fiber (fiber TF systems in the Arctic, as currently used and reported

determined from MF only) were also significantly higher on during this research, include a rich diversity of animal and

days without TF for Inuit. Calcium was low in all dietary plant species. Arctic cultural areas are among the most distant

records, and vitamin D, primarily in the TF component, for from centers of commerce in all of North America, and one

Inuit was 3 times that of Yukon and Dene/Métis. Sodium was would therefore anticipate the maximum current use of TF.

significantly higher for all cultural groups on days when only Dene/Métis, Yukon First Nations, and Inuit communities have

MF was consumed (added table salt not considered). the contemporary traditional knowledge for use of a surpris-

BMI was computed with data from Yukon and Inuit women ingly high number of food species: 62, 53, and 129 species of

and men, excluding known pregnant and lactating women animals (including fish) used, and 40, 48, and 42 species of

from this data set (Table 3). As is the case in most population plants, respectively (22). The average community TF percent-

groups, BMI tended to increase with age, and men tended to age of energy was earlier noted as 6 – 40% with differences

be slimmer than women. Obesity (BMI ⱖ 30 kg/m2) was more associated with proximity to urban areas, accessibility to roads,

prevalent in Inuit adults than among Yukon First Nations. and Northern latitudes (21,22). However, although these

To check the association between TF use and BMI, we ⬎100 species per cultural group are known, the extent of use

8 9

Supplement Appendix Table 2 gives the percentage of energy from macro- Supplement Appendix Figure 2 gives sources of energy by BMI categories,

nutrients, and is available with the online posting of this paper at www.nutrition. age, and cultural group. This is available with the online posting of this paper at

org. www.nutrition.org.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jn/article-abstract/134/6/1447/4688754

by guest

on 28 March 2018

DIETARY CHANGE AMONG ARCTIC INDIGENOUS PEOPLES 1451

TABLE 3 45– 69 y increased from 1970 to 1992, from 8.1 to 13.4% for

men and 12.7 to 15.4% for women. Further, obesity in women

BMI of Yukon and Inuit women and men1 was 10.6% in the younger group compared with 22.9% in the

older group in the 1986 –1992 time period. Men were slimmer,

20–40 y 41–60 y ⬎60 y

with 12 and 15.7% in the same age categories, respectively.

Yukon Education and income levels were inversely associated with

women higher obesity in Canada (48,49). Brazilian data demonstrate

BMI, kg/m2 25 ⫾ 4.4 28 ⫾ 5.3 28 ⫾ 5.7 opposite trends in obesity by income in this LDC. Over a

n 123 49 26 similar time period in the 1990s, the overall country preva-

% obese2 7 31 38 lence of obesity increased from 2.1 to 6.4% in men and from

Inuit women 6.0 to 12.4% in women, with the 25% richest of the popula-

BMI, kg/m2 27 ⫾ 5.5 28 ⫾ 5.7 29 ⫾ 7.0

n 272 156 36 tion usually being more obese (8 –10% obesity in this segment)

% obese 23 38 44 (50). Yukon and Inuit women exceeded these obesity preva-

Yukon men lences with 31 and 38% in older age groups, and Yukon and

BMI, kg/m2 25 ⫾ 3.0 26 ⫾ 2.9 29 ⫾ 4.6 Inuit men demonstrated 8 and 21% in older age groups,

n 106 48 23 respectively. Overall, the prevalence of obesity for Yukon and

% obese 5 8 35 Inuit women (17 and 30%, respectively) exceeded the all-

Inuit men

BMI, kg/m2 26 ⫾ 3.9 27 ⫾ 5.0 26 ⫾ 5.4 Canadian data reported in 1996 –1997 of 12% for women (49).

n 289 163 44 Similar data for Yukon men (10%) was slightly lower than the

% obese 16 21 23 all-Canadian male (11%), but Inuit men were at 18%. In the

Alaskan Arctic, both Yup’ik and Athabascan Indigenous Peo-

1 Values are means ⫾ SD. ples had levels of obesity similar to those found in Arctic

2 BMI ⱖ30 kg/m2.

Canada, i.e., 25.7 and 27.4% of men (Yup’ik and Athabascan

men) and 29 and 27.4% of women (Yup’ik and Athabascan

women) ⬎ 40 y old were obese (46). Inuit in Greenland had

as shown here was limited. Appendix Table 17 demonstrates a somewhat lower overall obesity (BMI ⱖ 30 kg/m2) preva-

that the 4th and 5th most commonly used seasonal species lence of 19.7%, with 16.4% among men and 22.4% among

were limited in use frequency to 0.7– 0.1 d/wk (⬃1– 8 d/sea- women (51). Thus, overall, indigenous Arctic men and

son). women have obesity prevalence that exceeds North American

Changing patterns of TF use over time are one way in national prevalence, and that also exceeds the prevalence

which to document the nutrition transition among Indigenous from the lowest education and income strata in Canada.

Peoples. Before colonial contact in the Americas, Indigenous The global phenomenon of increasing population obesity is

Peoples had 100% of dietary energy from their TF resources. well documented (4 – 8), but the data disaggregated for Indig-

This pattern persisted in the Canadian Arctic until the advent enous People are sparse. High obesity prevalence and conse-

of Hudson’s Bay stores at the turn of the 20th century. Today quent chronic disease are reported throughout aboriginal com-

only 10 –36% of adult dietary energy is derived from TF munities in North America (52,53) and Uauy et al. (7)

(Table 4). demonstrated that Mapuche women and men in Chile became

An additional measure of dietary change is the difference in more obese when living in an urban area, in contrast to those

TF use between older and younger population subsets. In the living in a rural environment. Urban and rural women had a

research reported here, individuals ⬎ 40 y old consistently

consumed significantly more TF than those younger (20 – 40 y)

(Fig. 1). From Table 1 it is clear that the kinds of MF used TABLE 4

consistently and most frequently across the Canadian Arctic

are least-cost sources of energy, and as a whole, have poor The percentage of energy from traditional food by BMI

nutrient density. It is therefore no surprise that in Appendix categories of Yukon and Inuit women and men1

Table 2,8 the days reported without TF were significantly

higher in carbohydrate, fat, and sucrose, and this was consis- Women Men

tent across all cultural groups. Protein and most micronutri-

ents were superior in recalls from days containing TF. This is BMI, kg/m2 20–40 y 41–60 y 20–40 y 41–60 y

especially meaningful when so little total dietary energy is

%

consumed as TF. Although the effect of markets on the health

of rural Indigenous Peoples is still controversial (44), a poor Yukon

quality diet has long been associated with increasing obesity, ⬍25 10.5 ⫾ 2.0 18.8 ⫾ 5.2# 18.5 ⫾ 3.1 24.1 ⫾ 4.8

diabetes, and glucose intolerance in many North American n 83 18 68 28

indigenous groups (24,45,46). Gittelsohn et al. (47) showed an ⱖ25 and ⬍30 15.1 ⫾ 2.6 21.7 ⫾ 4.8 12.9 ⫾ 3.8 20.1 ⫾ 4.9

association with diabetes risk by junk food and bread/butter n 48 22 46 24

ⱖ30 16.3 ⫾ 6.2 28.1 ⫾ 5.8 23.5 ⫾ 9.8 18.6 ⫾ 12.9

(high-sugar, low-fiber, high-fat) in an Ontario First Nation n 8 15 6 4

community. It is intuitive that meat and fish contribute sub- Inuit

stantially to micronutrient intakes, but it may be less intuitive ⬍25 17.7 ⫾ 2.0 22.6 ⫾ 3.7 15.8 ⫾ 2.1 28.8 ⫾ 3.9*

to realize that Arctic TF systems are most likely the best global n 122 51 123 56

examples of Indigenous Peoples’ food being far superior to the ⱖ25 and ⬍30 17.0 ⫾ 2.3 27.5 ⫾ 3.7# 16.0 ⫾ 2.1 33.2 ⫾ 3.6*

MF presented as alternatives. n 87 47 121 72

ⱖ30 14.1 ⫾ 2.8 30.3 ⫾ 3.4* 18.0 ⫾ 3.5 36.0 ⫾ 4.9*

We demonstrate for Canadian Arctic adults the widely n 3 59 45 34

recognized phenomenon that BMI increases with age. Tor-

rance et al. (48) showed that all Canadian average obesity 1 Values are the LSM estimates ⫾ SEM, adjusted for site. Symbols

(BMI ⱖ 30 kg/m2) rates for men and women 20 – 44 and indicate different from 20 – 40 y group (t test, # P ⬍ 0.05 and * P ⬍ 0.01).

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jn/article-abstract/134/6/1447/4688754

by guest

on 28 March 2018

1452 KUHNLEIN ET AL.

prevalence of obesity of 44.7 and 32.1%, respectively; that for Special thanks for work well done is extended to the 16 CINE

men was 28.3 and 15%, respectively. It is thus clear from the research coordinators and 97 trained interviewers. Additionally, we

available data for Indigenous People that these women and are grateful for special and very competent work on the project by

men exceed the national averages for becoming obese. When Annie May Propert, Amy Ing, Marjolaine Boulay, and Peter Berti.

TF is lost, and low-cost but high-energy MF is substituted, the

basis for developing obesity exists. This is coincident with LITERATURE CITED

additional circumstances of changing activity patterns and

possible genetic predisposition. 1. Civil Society Organizations and Participation Programme (CSOPP) of the

Micronutrient nutrition, with the dietary transition de- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Indigenous Peoples. http://

www.undp.org/csopp/CSO/NewFiles/ipaboutdef.html [accessed Oct. 28, 2003].

scribed here, is also of concern. When traditional Arctic food 2. Cunningham, C. & Stanley, F. (2003) Indigenous by definition, expe-

is consumed, even in small amounts, nutrition for most mi- rience, or world view. Br. Med. J. 327: 403– 404.

cronutrients is improved (Table 2). Even vitamin C, a nutrient 3. Ring, I. & Brown, N. (2003) The health status of indigenous peoples

commonly associated with fresh fruit and vegetables, was and others. Br. Med. J. 327: 404 – 405.

4. Popkin, B. M. (2002) An overview on the nutrition transition and its

shown to exist in ample quantities in Arctic TF meats (31). health implications: the Bellagio meeting. Public Health Nutr. 5: 93–103.

Formerly, all parts of animals, fish, and many plants were 5. Caballero, B. (2001) Symposium: Obesity in developing countries:

consumed, which gave a rich micronutrient base; but fre- biological and ecological factors. Introduction. J. Nutr. 131: 886 – 870.

6. Martorrel, R., Stein, A. D. & Schroeder, D. G. (2001) Early nutrition and

quency data reported here showed that few organ meats now later adiposity. J. Nutr. 131: 874S– 880S.

consumed, and that amounts and frequency of animal/fish flesh 7. Uauy, R., Albala, C. & Kain, J. (2001) Obesity trends in Latin America:

food consumption declined with age. If MF of sufficient quality transiting from under- to overweight. J. Nutr. 131: 893S– 899S.

8. Young, T. K. (1988) Are subarctic Indians undergoing the epidemio-

(meat, low-fat dairy items, vegetables, whole grains) is not logic transition? Soc. Sci. Med. 26: 659 – 671.

available and consumed to replace the missing micronutrients 9. Anand, S. S., Yusuf, S., Jacobs, R., Davis, A. D., Yi, Q., Gerstein, H.,

from traditional meats, fish and organs, the nutrition of the Montague, P. A. & Lonn, E., for the SHARE-AP Investigators (2001) Risk

factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease among Aboriginal people in

entire community is at risk. Our research makes clear that this Canada: the Study of Health Assessment and Risk Evaluation in Aboriginal

type of MF is not used regularly. Peoples (SHARE-AP). Lancet 358: 1147–1153.

In this study, as is customary with 24-h recalls, total energy 10. Yusuf, S., Reddy, S., Ounpuu, S. & Anand, S. (2001) Global burden of

cardiovascular diseases. Part I. General considerations, the epidemiologic tran-

intake may have been slightly underestimated, if only because sition, risk factors and impact of urbanization. Circulation 104: 2746 –2753.

alcohol intake was not regularly recorded. Because energy 11. Yusuf, S., Reddy, S., Ounpuu, S. & Anand, S. (2001) Global burden of

intake was higher with TF (Table 2), it may be interpreted cardiovascular diseases. Part II. Variations in cardiovascular disease by specific

that TF was consumed in addition to MF, rather than as a ethnic groups and geographic regions and prevention strategies. Circulation 104:

2855–2864.

substitute for MF. Alternatively, when TF was available, large 12. Uauy, R. & Kain, J. (2001) The epidemiological transition: need to

portions were consumed, whereas smaller amounts of MF incorporate obesity prevention into nutrition programmes. Public Health Nutr. 5:

meats were eaten by adults, and fat intakes increased. 223–229.

13. World Health Organization (2002) International Decade of the World’s

For all Indigenous Peoples, food is at the heart of culture Indigenous People. Report by the Secretariat. 55th World Health Assembly A55/

and health, and it is considered to be part of the environmen- 35, Geneva, Switzerland.

tal whole in which families live. Close ties to the land for its 14. Waldram, J. B., Herring, D. A. & Young, T. K. (1995) Aboriginal Health

in Canada: Historical, Cultural and Epidemiological Perspectives. University of

health-giving properties are part of cultural identity (2). Toronto Press, Toronto, Canada.

Global warming and other environmental insults such as con- 15. Statistics Canada (2003) 2001 Census. Aboriginal Peoples of Canada:

taminants in air and water resources are signaled by elders and A Demographic Profile. Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

16. Young, T. K. (1996) Sociocultural and behavioural determinants of

indigenous leaders as serious threats because of the potential obesity among Inuit in the Central Canadian Arctic. Soc. Sci. & Med. 43: 1665–

effect on TF quality (1,54). Although recognized as an essen- 1671.

tial part of life, the all-Arctic average of TF energy is now 17. Young, T. K. (1996) Obesity, central fat patterning, and their metabolic

⬃22% (Yukon at 17%, Dene/Métis at 21%, and Inuit at 28%). correlates among the Inuit of the Central Canadian Arctic. Hum. Biol. 68: 245–263.

18. Bjerregard, P. & Young, T. K. (1998) The Circumpolar Inuit: Health of

Even at these average portions of daily energy, TF is critical for a Population in Transition. Munksgaard International; Copenhagen, Denmark.

providing many essential nutrients in adult diets. A variety of 19. Wein, E. (1995) Nutrient intakes of First Nations People in four Yukon

intervention programs to improve MF availability and choices, communities. Nutr. Res. 15: 1105–1119.

20. Kuhnlein, H. V. (1995) Benefits and risks of traditional food for Indig-

as well as acceptable preparation methods, are called for. At enous Peoples: focus on dietary intakes of Arctic men. Can. J. Physiol. Pharma-

the same time, policies and programs should be developed so col. 73: 765–771.

that communities can maintain or improve, if possible, the 21. Receveur, O., Boulay, M. & Kuhnlein, H. V. (1997) Decreasing tradi-

tional food use affects diet quality for adult Dene/Métis in 16 communities of the

availability and accessibility of nutrient-dense, excellent qual- Canadian Northwest Territories. J. Nutr. 127: 2179 –2186.

ity traditional Arctic foods. It is also salient to note that 22. Kuhnlein, H. V., Receveur, O. & Chan, H. M. (2001) Traditional food

protection of TF environments is critical for this to happen. systems research with Canadian Indigenous Peoples. Int. J. Circumpolar Health

60: 112–122.

23. Kuhnlein, H. V., Soueida, R. & Receveur, O. (1996) Dietary nutrient

profiles of Canadian Baffin Island Inuit differ by food source, season and age.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 96: 155–162.

24. Kuhnlein, H. V. & Receveur, O. (1996) Dietary change and traditional

This project was successful because of the many fine research food systems of Indigenous Peoples. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 16: 417– 442.

collaborators we worked with during the 10-year research period. We 25. Kuhnlein, H. V., Receveur, O., Muir, D.C.G., Chan, H. M. & Soueida, R.

appreciated keenly the support, concern, and understanding of the (1995) Arctic Indigenous women consume greater than acceptable levels of

many community members and staff of the Dene Nation, Métis organochlorines. J. Nutr. 125: 2501–2510.

26. World Health Organization and Centre for Indigenous Peoples’ Nutrition

Nation (NWT), the Council of Yukon First Nations, and the Inuit and Environment (2003) Indigenous Peoples and Participatory Health Re-

Tapiriit Kanatami. In particular, we thank Bill Erasmus, Carole Mills, search. Planning and Management/Preparing Research Agreements. WHO, Ge-

William Carpenter, Barney Masuzumi, Ed Schultz, Betsy Jackson, neva, Switzerland.

Norma Kassi, Cindy Dickson, Rosemary Kuptana, Okalik Eegeesiak, 27. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Sites for Nunavut, Labrador, North-

Maryann Demmer, Peter Usher, Craig Boljkovak, and Eric Loring. west Territories and Yukon. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ [accessed Aug. 26,

Community organizations upon which we heavily relied were Dene 2003].

28. The Dene Nation (1984) Denendeh, a Dene Celebration. The Dene

Community Councils, Métis Locals, Yukon Community Councils, Nation, Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, Canada.

Inuit Hamlet Councils, Hunters and Trappers Associations, the La- 29. Council of Yukon First Nations (2000) Yukon Native Peoples and

brador Inuit Association, and the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation. Languages. Yukon Native Language Centre, Whitehorse, Yukon.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jn/article-abstract/134/6/1447/4688754

by guest

on 28 March 2018

DIETARY CHANGE AMONG ARCTIC INDIGENOUS PEOPLES 1453

30. Kuhnlein, H. V., Receveur, O. & Ing, A. (2001) Energy, fat and calcium 43. Zar, J. H. (1984) Biostatistical Analysis, 2nd ed. Prentice-Hall, Engle-

in bannock consumed by Canadian Inuit. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 101: 580 –581. wood Cliffs, NJ.

31. Fediuk, K., Hidiroglou, N., Madère, R. & Kuhnlein, H. V. (2002) Vitamin 44. Godoy, R. & Cardenas, M. (2000) Markets and the health of indige-

C in Inuit traditional food and women’s diets. J. Food Compos. Anal. 15: 221–235. nous people: a methodological contribution. Hum. Organ. 59: 117–124.

32. Kuhnlein, H. V., Chan, H. M., Leggee, D. & Barthet, V. (2002) Macro- 45. West, K. M. & Kalbfleisch, J. M. (1971) Influence of nutritional factors

nutrient, mineral and fatty acid composition of Canadian Arctic traditional food. J. on the prevalence of diabetes. Diabetes 20: 99 –108.

Food Compos. Anal. 15: 545–566. 46. Murphy, N. J., Schraer, C. D., Thiele, M. C., Boyko, M. K., Bulkow, L. R.,

33. Kuhnlein, H. V. (2001) Nutrient benefits of Arctic traditional/country Doby, B. J. & Lanier, A. P. (1995) Dietary change and obesity associated with

foods. In: Synopsis of Research Conducted under the 2000 –2001 Northern glucose intolerance in Alaska Natives. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 95: 676 – 682.

Contaminants Program (Kalhok, S., ed.), pp. 56 – 64. Published under the author- 47. Gittelsohn, J., Wolever, T.M.S., Harris, S. B., Harris-Hiraldo, R., Hanley,

ity of the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Ottawa, Canada. A.J.G. & Zinman, B. (1998) Specific patterns of food consumption and prep-

34. Appavoo, D., Kubow, S. & Kuhnlein, H. V. (1991) Lipid composition of aration are associated with diabetes and obesity in a native Canadian community.

indigenous foods eaten by the Sahtú (Hareskin) Dene/Métis of the Northwest J. Nutr. 128: 542–547.

territories. J. Food Compos. Anal. 4: 107–119. 48. Torrance, G. M., Hooper, M. D. & Reeder, B. A. (2002) Trends in

35. Kuhnlein, H. V., Kubow, S. & Soueida, R. (1991) Lipid components of overweight and obesity among adults in Canada (1970 –1992): evidence from

traditional Inuit foods and diets of Baffin Island. J. Food Compos. Anal. 4: national surveys using measured height and weight. Int. J. Obes. 26: 797– 804.

227–236. 49. Gilmore, J. (1999) Body mass index and health. Statistics Canada

36. Kuhnlein, H. V. & Soueida, R. (1992) Use and nutrient composition of Catalogue 82– 003. Health Rep. 11: 31– 43.

traditional Baffin Inuit foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 5: 112–126. 50. Monteiro, C. A., Conde, W. I. & Popkin, B. M. (2001) What has

37. Morrison, N. & Kuhnlein, H. V. (1993) Retinol content of wild foods happened in terms of some of the unique elements of shift in diet, activity, obesity,

consumed by the Sahtú (Hareskin) Dene/Métis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 6: 10 –23. and other measures of morbidity and mortality within different regions of the

38. Kuhnlein, H. V., Appavoo, D., Morrison, N., Soueida, R. & Pierrot, P. world? Is obesity replacing or adding to undernutrition? Evidence from different

(1994) Use and nutrient composition of traditional Sahtú (Hareskin) Dene/Métis social classes in Brazil. Part I. Public Health Nutr. 5: 105–112.

foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 7: 144 –157. 51. Bjerregard, P., Curtis, T., Borch-Johnsen, K., Mulvad, G., Becker, U.,

39. Murphy, S. P. & Gross, K. R. (1987) The UCB Mini-List Diet Analysis Andersen, S. & Backer, V. (2003) Inuit health in Greenland. A population survey

System. MS-DOS Version User’s Guide (rev. June 1987). The Regents of the of lifestyle and disease in Greenland and among Inuit living in Denmark. Int. J.

University of California, Berkeley, CA. Circumpolar Health 62: 3–79.

40. Holden, J. M., Eldridge, A. L., Beecher, G. R., Buzzard, I. M., Bhagwat, S., 52. Young, T. K. (1994) The Health of Native Americans. Toward a Biocul-

Davis, C. S., Douglass, L. W., Gebhardt, S., Haytowitz, D. & Shakel, S. (1999) tural Epidemiology, pp. 139 –175. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

Carotenoid content of U.S. foods: an update of the database. J. Food Compos. 53. Young, T. K., Reading, J., Elias, B. & O’Neil, J. D. (2000) Type 2

Anal. 12: 169 –196. diabetes mellitus in Canada’s First Nations: status of an epidemic in progress.

41. Murphy, S. P. (2001) Changes in dietary guidance: implications for Can. Med. Assoc. J. 163: 561–566.

food and nutrient databases. J. Food Compos. Anal. 14: 269 –278. 54. Watt-Cloutier, S. (2003) The Inuit journey towards a POPs-free world.

42. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Agricultural Research In: Northern Lights against POPs (Combatting Toxic Threats in the Arctic)

Service. Nutrient Data Laboratory. http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/cgi-bin/nut- (Downie, D. L. & Fenge, T., eds.), pp. 256 –267. McGill-Queens University Press,

_search.pl [accessed June 11, 2000]. Montreal, Canada.

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jn/article-abstract/134/6/1447/4688754

by guest

on 28 March 2018

You might also like

- Baby Food Business PlanDocument1 pageBaby Food Business Planadedoyin123No ratings yet

- An Introduction To RBTI: by Matt Stone Independent Health Researcher FromDocument71 pagesAn Introduction To RBTI: by Matt Stone Independent Health Researcher FromF Woyen100% (1)

- American Academy of PediatricsDocument1,746 pagesAmerican Academy of PediatricsDaniel CastroNo ratings yet

- Assessment & Priorities For The Health and Well-Being in Native Hawaiians and Pacific IslandersDocument43 pagesAssessment & Priorities For The Health and Well-Being in Native Hawaiians and Pacific IslandersHPR News100% (1)

- Action Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesAction Plan TemplateYao Pocillas Christy Zeeky100% (2)

- 2019 ENNS Results Dissemination - Adolescents and WRADocument48 pages2019 ENNS Results Dissemination - Adolescents and WRAbeverlyNo ratings yet

- Kids Guide To Birds of Central Park PDFDocument7 pagesKids Guide To Birds of Central Park PDFrafrejuNo ratings yet

- Level 1 v4 Forms PG 1-9Document9 pagesLevel 1 v4 Forms PG 1-9Jože MajcenNo ratings yet

- Dietary Practices Among Arabic Speaking Immigrants and Refugees I - 2020 - AppetDocument11 pagesDietary Practices Among Arabic Speaking Immigrants and Refugees I - 2020 - AppetHellen OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Demographic and Socioeconomic Determinants of Variation in Food and Nutrient Intake in An Andean CommunityDocument11 pagesDemographic and Socioeconomic Determinants of Variation in Food and Nutrient Intake in An Andean CommunityAndjela RoganovicNo ratings yet

- Traditional Foods Case StudyDocument39 pagesTraditional Foods Case StudytehaliwaskenhasNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument9 pagesAnnotated BibliographySikany S EmmanNo ratings yet

- Ferguson Et Al-2015-Maternal & Child NutritionDocument15 pagesFerguson Et Al-2015-Maternal & Child Nutritionayu38No ratings yet

- 2 - Chinese Overview CoursepaperDocument11 pages2 - Chinese Overview CoursepaperSalma MalihaNo ratings yet

- 04Document12 pages04Ar Shubham JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Child's Growth and Nutritional Status in Two Communities-Mishing Tribe and Kaibarta Caste of Assam, IndiaDocument11 pagesChild's Growth and Nutritional Status in Two Communities-Mishing Tribe and Kaibarta Caste of Assam, IndiaFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Group 6 - STEM 119 - Chapter 2 - DraftDocument26 pagesGroup 6 - STEM 119 - Chapter 2 - Draftpaylleikim95No ratings yet

- Indigenous FoodDocument14 pagesIndigenous Foodfairen xielNo ratings yet

- NutDocument12 pagesNutRohit GadekarNo ratings yet

- Davis 2013. Coping With Diabetes and Generational Trauma in Salish Tribal CommunitiesDocument36 pagesDavis 2013. Coping With Diabetes and Generational Trauma in Salish Tribal CommunitiesfiorelashahinasiNo ratings yet

- Coprolite AnalysisDocument8 pagesCoprolite AnalysiselcyionstarNo ratings yet

- Food Security (Published)Document11 pagesFood Security (Published)Clarice LauNo ratings yet

- Changing Food Culture For Food Wellbeing: Efereed PaperDocument14 pagesChanging Food Culture For Food Wellbeing: Efereed PaperF ANo ratings yet

- Peanuts As Part of Health DietDocument5 pagesPeanuts As Part of Health Dietjuliet hatohoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2161831322003556 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S2161831322003556 MainabuhudzaifNo ratings yet

- Westernization of Dietary Patterns Among Young Japanese and Polish Females - A Comparison StudyDocument9 pagesWesternization of Dietary Patterns Among Young Japanese and Polish Females - A Comparison StudyLuiz Eduardo RodriguezNo ratings yet

- TMP CBB5Document12 pagesTMP CBB5FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Perspective: New England Journal MedicineDocument3 pagesPerspective: New England Journal MedicinekasandraharahapNo ratings yet

- 1 PB PDFDocument19 pages1 PB PDFKharen Domacena DomilNo ratings yet

- Investigating Factors Affecting Food Security in Heipang Community of Barkin Ladi, Plateau StateDocument13 pagesInvestigating Factors Affecting Food Security in Heipang Community of Barkin Ladi, Plateau Statesegun aladeNo ratings yet

- Dietary Profile of Urban Adult Population in South India in The Context of Chronic Disease EpidemiologyDocument8 pagesDietary Profile of Urban Adult Population in South India in The Context of Chronic Disease Epidemiologylatifah zahrohNo ratings yet

- J. Nutr.-2003-Bwibo-3936S-40SDocument5 pagesJ. Nutr.-2003-Bwibo-3936S-40SwaitNo ratings yet

- Proyecto de Tesis JC RiojaDocument72 pagesProyecto de Tesis JC RiojaJuan RiojaNo ratings yet

- Marron 2019Document14 pagesMarron 2019anaceciliafdezNo ratings yet

- Food Neophobia Is Related To Factors Associated With Functional Food Consumption in Older AdultsDocument8 pagesFood Neophobia Is Related To Factors Associated With Functional Food Consumption in Older AdultsrodrigoromoNo ratings yet

- Hata Et Al. - 2017 - The Association Between Health-Related Quality ofDocument6 pagesHata Et Al. - 2017 - The Association Between Health-Related Quality ofarancibiabNo ratings yet

- Assignment TemplateDocument9 pagesAssignment TemplateAbcd 1234No ratings yet

- Awareness of and Adherence To The Food Based Dietary GuidelinesDocument14 pagesAwareness of and Adherence To The Food Based Dietary GuidelinesraffaellamattioniNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Transition in 2 Lowland Bolivian Subsistence PopulationsDocument13 pagesNutrition Transition in 2 Lowland Bolivian Subsistence PopulationslibremdNo ratings yet

- Reni 2002Document10 pagesReni 2002generics54321No ratings yet

- Human Diet and Nutrition in Biocultural Perspective: Past Meets PresentFrom EverandHuman Diet and Nutrition in Biocultural Perspective: Past Meets PresentTina MoffatNo ratings yet

- High-Risk Nutritional Practices in African AmericansDocument12 pagesHigh-Risk Nutritional Practices in African AmericansSammy ChegeNo ratings yet

- A Review On Changes in Food Habits Among Immigrant Women and Implications For HealthDocument9 pagesA Review On Changes in Food Habits Among Immigrant Women and Implications For HealthHellen OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Compassion and Contamination. Cultural Differences in Vegetarianism. AppetiteDocument9 pagesCompassion and Contamination. Cultural Differences in Vegetarianism. AppetitealejandroNo ratings yet

- Journal of Ethnic Foods: Seema Patel, Ha Fiz A.R. SuleriaDocument6 pagesJournal of Ethnic Foods: Seema Patel, Ha Fiz A.R. SuleriaFernando SousaNo ratings yet

- Dietary Quality Indices PHN 2013Document12 pagesDietary Quality Indices PHN 2013Xochitl PonceNo ratings yet

- Diet Food Supply ObesityDocument70 pagesDiet Food Supply ObesityHaNo ratings yet

- Dietary Diversity Score Is A Useful Indicator of Micronutrient Intake in Non-Breast-Feeding Filipino ChildrenDocument6 pagesDietary Diversity Score Is A Useful Indicator of Micronutrient Intake in Non-Breast-Feeding Filipino ChildrenNadiah Umniati SyarifahNo ratings yet

- Fast Food JacnDocument7 pagesFast Food JacnSibel AzisNo ratings yet

- Kyomuhendo Adeola 2021.BSD2153Document12 pagesKyomuhendo Adeola 2021.BSD2153Indiana RidwanNo ratings yet

- Community NutritionDocument3 pagesCommunity NutritionnajeebNo ratings yet

- Dietary Diversity Fact SheetDocument2 pagesDietary Diversity Fact Sheetcaptaincupcakes95No ratings yet

- NutritionDocument1 pageNutritionRainy seasonNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Labels On Pre Packaged Foods A Systematic ReviewDocument11 pagesNutrition Labels On Pre Packaged Foods A Systematic ReviewSiska PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Appetite: Manoshi BhattacharyaDocument34 pagesAppetite: Manoshi BhattacharyaRenu VermaNo ratings yet

- A Posteriori Dietary Patterns, Insulin Resistance, and Diabetes Risk by Hispanic/Latino Heritage in The HCHS/SOL CohortDocument11 pagesA Posteriori Dietary Patterns, Insulin Resistance, and Diabetes Risk by Hispanic/Latino Heritage in The HCHS/SOL CohortLara CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 13 02444Document13 pagesNutrients 13 02444ToghrulNo ratings yet

- Health Indigenous AmazonDocument12 pagesHealth Indigenous AmazonWildan HakimNo ratings yet

- Food Access and Nutritional Status of RuralDocument8 pagesFood Access and Nutritional Status of RuralritapuspaNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Nutrition Research Agenda in Indonesia and Beyond: Ecological Strategy For Food in Health Care DeliveryDocument9 pagesThe Clinical Nutrition Research Agenda in Indonesia and Beyond: Ecological Strategy For Food in Health Care DeliveryFaniaParra FaniaNo ratings yet

- Food Variety Socioeconomic Status and Nutritional Status in Urban and Rural Areas in Koutiala MaliDocument9 pagesFood Variety Socioeconomic Status and Nutritional Status in Urban and Rural Areas in Koutiala MaliGabriel SoaresNo ratings yet

- Childrens Right - Literature PaperDocument7 pagesChildrens Right - Literature Paperapi-664310702No ratings yet

- Healthy Eating Traditional EatingDocument6 pagesHealthy Eating Traditional EatingJeffrey PeekoNo ratings yet

- Accepted ManuscriptDocument34 pagesAccepted ManuscriptOmmi Samuel G SNo ratings yet

- American IndiansDocument16 pagesAmerican Indiansapi-651130562No ratings yet

- How Diverse Is The Diet of Adult South Africans?: Research Open AccessDocument11 pagesHow Diverse Is The Diet of Adult South Africans?: Research Open AccessIndah Permata LillahiNo ratings yet

- Buenos Hábitos Alimenticios para Una Buena SaludDocument15 pagesBuenos Hábitos Alimenticios para Una Buena SaludMelisa RieloNo ratings yet

- International Association For Plant Taxonomy (IAPT)Document4 pagesInternational Association For Plant Taxonomy (IAPT)rafrejuNo ratings yet

- Plant DomesticationDocument9 pagesPlant DomesticationrafrejuNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Double Burden of Undernutrition and Excess Weight in Latin AmericaDocument4 pagesIntroduction To The Double Burden of Undernutrition and Excess Weight in Latin AmericarafrejuNo ratings yet

- Youngia JaponicaDocument6 pagesYoungia Japonicarafreju100% (1)

- Technical Manual. Emergency Food Plants and Poisonous Plants of The Islands of The Pacific. April 15, 1943 (TM 10-420)Document1 pageTechnical Manual. Emergency Food Plants and Poisonous Plants of The Islands of The Pacific. April 15, 1943 (TM 10-420)rafrejuNo ratings yet

- The Nutritional Value of Indigenous Fruits and Vegetables in SarawakDocument8 pagesThe Nutritional Value of Indigenous Fruits and Vegetables in SarawakrafrejuNo ratings yet

- Edible Plants: Eduardo H. Rapoport and Barbara S. DrausalDocument8 pagesEdible Plants: Eduardo H. Rapoport and Barbara S. DrausalrafrejuNo ratings yet

- Four Views On AdamDocument4 pagesFour Views On AdamrafrejuNo ratings yet

- Kindle User GuideDocument145 pagesKindle User GuiderafrejuNo ratings yet

- Effects of Junk FoodDocument16 pagesEffects of Junk FoodKatherine DeeNo ratings yet

- Sicem2016 P 062 Jundrian DoringoDocument3 pagesSicem2016 P 062 Jundrian DoringoSharnelle Valdez NotoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 (Slaughter and Fabrication)Document15 pagesLesson 1 (Slaughter and Fabrication)Angel MantalabaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Whey Protein in Conjunction With A.24Document9 pagesEffect of Whey Protein in Conjunction With A.24Arnold MugaboNo ratings yet

- Fetelo PDFDocument24 pagesFetelo PDFsumit dasNo ratings yet

- Chapter Five Food StorageDocument38 pagesChapter Five Food StorageAyro Business Center100% (1)

- Understanding Calories Wrigley's Chewing GumDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Calories Wrigley's Chewing GumGerishNillasGeeNo ratings yet

- 7 Human Nutrition (Notes)Document20 pages7 Human Nutrition (Notes)Maya YazalNo ratings yet

- Personalized Diet Plan-Fitness Program Meal PlanDocument8 pagesPersonalized Diet Plan-Fitness Program Meal PlanPrincess Pauline AbrasaldoNo ratings yet

- Protocol For Management of Malnutrition in Children: Oy Orar Geeaot Harcral Aret Felcors Harerel AbhiyanDocument24 pagesProtocol For Management of Malnutrition in Children: Oy Orar Geeaot Harcral Aret Felcors Harerel Abhiyantanishqsaxena100210No ratings yet

- Looksmaxxing EbookDocument359 pagesLooksmaxxing Ebookni4805151No ratings yet

- Whey Protein Concentrate 35Document1 pageWhey Protein Concentrate 35restandcleanaguachicaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Adding Non-Conventional Ingredients and Hydrocolloids To Desirable Quality Attributes of Pasta. A Mini ReviewDocument7 pagesThe Effect of Adding Non-Conventional Ingredients and Hydrocolloids To Desirable Quality Attributes of Pasta. A Mini ReviewNguyen Minh TrongNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in Physical Education and HealthDocument5 pagesLesson Plan in Physical Education and HealthKendi SaagundoNo ratings yet

- Mertens 2003 PDFDocument19 pagesMertens 2003 PDFEdgard MalaguezNo ratings yet

- Lesson 8 PovertyDocument5 pagesLesson 8 PovertyRakoviNo ratings yet

- POSHAN TrackerDocument18 pagesPOSHAN TrackerJEEJANo ratings yet

- Marketing Plan Group3 1 1Document44 pagesMarketing Plan Group3 1 1Daisy Jane BayolaNo ratings yet

- Moulting DietDocument7 pagesMoulting DietzahidnaeemahmedNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Food Fortification: The Advantages, Disadvantages and Lessons From Sight and Life ProgramsDocument12 pagesNutrients: Food Fortification: The Advantages, Disadvantages and Lessons From Sight and Life ProgramsArvie ChavezNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Management in Respiratory DiseasesDocument23 pagesNutritional Management in Respiratory DiseasesRafia KhalilNo ratings yet

- Clinical & Non-Clinical Department PPT FinalDocument12 pagesClinical & Non-Clinical Department PPT FinalDavid Raju GollapudiNo ratings yet

- Assignment of Social Welfare Administration Community KitchenDocument2 pagesAssignment of Social Welfare Administration Community KitchenfalguniNo ratings yet

- Antawan SBFP NFP Milk Survey Sy 2023 2024Document8 pagesAntawan SBFP NFP Milk Survey Sy 2023 2024Arlene SayloNo ratings yet