Professional Documents

Culture Documents

10 Thousand Hour Myth

10 Thousand Hour Myth

Uploaded by

Anonymous 2HzrnXC0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views3 pagesThe 10,000 hour rule for achieving expertise is only partially true according to Anders Ericsson, who conducted the original research. While extensive practice is important, it must be "deliberate practice" which involves focused concentration and feedback from expert coaches to refine techniques, rather than just repetitive practicing of mistakes. True experts are able to maintain focused, top-down concentration during practice, even of automated skills, in order to continuously improve, whereas amateurs are satisfied once a skill reaches a "good enough" automatic level.

Original Description:

An article on learning efficiently

Original Title

10_thousand_hour_myth

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe 10,000 hour rule for achieving expertise is only partially true according to Anders Ericsson, who conducted the original research. While extensive practice is important, it must be "deliberate practice" which involves focused concentration and feedback from expert coaches to refine techniques, rather than just repetitive practicing of mistakes. True experts are able to maintain focused, top-down concentration during practice, even of automated skills, in order to continuously improve, whereas amateurs are satisfied once a skill reaches a "good enough" automatic level.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views3 pages10 Thousand Hour Myth

10 Thousand Hour Myth

Uploaded by

Anonymous 2HzrnXCThe 10,000 hour rule for achieving expertise is only partially true according to Anders Ericsson, who conducted the original research. While extensive practice is important, it must be "deliberate practice" which involves focused concentration and feedback from expert coaches to refine techniques, rather than just repetitive practicing of mistakes. True experts are able to maintain focused, top-down concentration during practice, even of automated skills, in order to continuously improve, whereas amateurs are satisfied once a skill reaches a "good enough" automatic level.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 3

The following is an excerpt from Daniel Goleman’s new

book, “Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence.”

The “10,000-hour rule” — that this level of practice holds

the secret to great success in any field — has become

sacrosanct gospel, echoed on websites and recited as

litany in high-performance workshops. The problem: it’s

only half-true.

If you are a duffer at golf, say, and make the same

mistakes every time you try a certain swing or putt,

10,000 hours of practicing that error will not improve your

game. You’ll still be a duffer, albeit an older one.

No less an expert than Anders Ericsson, the Florida State

University psychologist whose research on expertise

spawned the ten-thousand-hour rule-of-thumb, told me,

“You don’t get benefits from mechanical repetition, but by

adjusting your execution over and over to get closer to

your goal.”

“You have to tweak the system by pushing,” he adds,

“allowing for more errors at first as you increase your

limits.”

Ericsson argues the secret of winning is “deliberate

practice,” where an expert coach takes you through well-

designed training over months or years, and you give it

your full concentration.

How experts in any domain pay attention while practicing

makes a crucial difference. While novices and amateurs

are content to let their passive, bottom-up systems take

over their routines, experts never rest their active

concentration during practice.

For instance, in his much-cited study of violinists – the

one that showed the top tier had practiced over 10,000

hours – Ericsson found the experts did so with full

concentration on improving a particular aspect of their

performance that a master teacher identified. The

feedback matters and the concentration does, too – not

just the hours.

Learning how to improve any skill requires top-down

focus. Neuroplasticity, the strengthening of old brain

circuits and building of new ones for a skill we are

practicing, requires our paying attention: When practice

occurs while we are focusing elsewhere, the brain does

not rewire the relevant circuitry for that particular routine.

Daydreaming defeats practice; those of us who browse

TV while working out will never reach the top ranks.

Paying full attention seems to boost the mind’s

processing speed, strengthen synaptic connections, and

expand or create neural networks for what we are

practicing.

At least at first. But as you master how to execute the

new routine, repeated practice transfers control of that

skill from the top-down system for intentional focus to

bottom-up circuits that eventually make its execution

effortless. At that point you don’t need to think about it –

you can do the routine well enough on automatic.

And this is where amateurs and experts part ways.

Amateurs are content at some point to let their efforts

become bottom-up operations. After about 50 hours of

training –whether in skiing or driving – people get to that

“good-enough” performance level, where they can go

through the motions more or less effortlessly. They no

longer feel the need for concentrated practice, but are

content to coast on what they’ve learned. No matter how

much more they practice in this bottom-up mode, their

improvement will be negligible.

The experts, in contrast, keep paying attention top-down,

intentionally counteracting the brain’s urge to automatize

routines. They concentrate actively on those moves they

have yet to perfect, on correcting what’s not working in

their game, and on refining their mental models of how to

play the game. The secret to smart practice boils down to

focus on the particulars of feedback from a seasoned

coach.

You might also like

- Jose Silva's The Silva UltraMind ESP System WorkbookDocument74 pagesJose Silva's The Silva UltraMind ESP System Workbookiva_marosi92% (39)

- Visual Language For DesignersDocument240 pagesVisual Language For DesignersAleksey100% (9)

- 6 Phases of The Perfect Dynamic Warm Up PDFDocument18 pages6 Phases of The Perfect Dynamic Warm Up PDFaphexish100% (2)

- Tom Platz - 7 SecretsDocument3 pagesTom Platz - 7 SecretsSimen Folkestad Soltvedt80% (5)

- Bodybuilding - Pete Sisco - CNS WorkoutDocument22 pagesBodybuilding - Pete Sisco - CNS WorkoutAkshay Narayanan100% (6)

- Chinese Programming Principles For Amateur WeightliftersDocument20 pagesChinese Programming Principles For Amateur WeightliftersY100% (3)

- Pitching Isn't Complicated: The Secrets of Pro Pitchers Aren't Secrets At AllFrom EverandPitching Isn't Complicated: The Secrets of Pro Pitchers Aren't Secrets At AllNo ratings yet

- Orange Lady (From "Weather Report")Document2 pagesOrange Lady (From "Weather Report")Anonymous 2HzrnXC100% (3)

- Enter the Zone: Three Steps for Accessing Peak PerformanceFrom EverandEnter the Zone: Three Steps for Accessing Peak PerformanceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The 10 New Essentials of Training For Power Athletes PDFDocument19 pagesThe 10 New Essentials of Training For Power Athletes PDFTheo Le Floch-andersen100% (1)

- 10 Essentials For Training Power AthletesDocument9 pages10 Essentials For Training Power Athletesinstantoffense100% (1)

- Tony Williams' ConceptsDocument3 pagesTony Williams' ConceptsAnonymous 2HzrnXC100% (3)

- Practice Makes Perfect ESSAYDocument2 pagesPractice Makes Perfect ESSAYpeachyskizNo ratings yet

- Learn Golf Template3Document12 pagesLearn Golf Template3Rob SmithNo ratings yet

- DBs MethodsDocument20 pagesDBs Methodscoctyus100% (4)

- Nick Winkelman Coaching ScienceDocument15 pagesNick Winkelman Coaching ScienceDiego LacerdaNo ratings yet

- Untitled 2Document54 pagesUntitled 2irfandwiwibowoNo ratings yet

- Reaction Time Training - The Right Way - The Sports EduDocument1 pageReaction Time Training - The Right Way - The Sports EduciufinaNo ratings yet

- 5 Things You Should Be Doing at The GymDocument9 pages5 Things You Should Be Doing at The GymTrue TechniqueNo ratings yet

- Over-Practiicing Makes PerfectDocument2 pagesOver-Practiicing Makes PerfectElvistingNo ratings yet

- You Are (Probably) Practicing WrongDocument8 pagesYou Are (Probably) Practicing WrongStoa TogNo ratings yet

- Neuroathletics Training for Beginners More Coordination, Agility and Concentration Thanks to Improved Neuroathletics - Incl. 10-Week Plan For Training in Everyday Life.From EverandNeuroathletics Training for Beginners More Coordination, Agility and Concentration Thanks to Improved Neuroathletics - Incl. 10-Week Plan For Training in Everyday Life.No ratings yet

- Ultimate NLP Home Study CourseDocument169 pagesUltimate NLP Home Study CourseNguyen Thao100% (4)

- Smart TrAInerDocument4 pagesSmart TrAInerUnez KaziNo ratings yet

- Tennis Circuitry: Master the Hardware of a Professional Tennis PlayerFrom EverandTennis Circuitry: Master the Hardware of a Professional Tennis PlayerNo ratings yet

- Control FundDocument3 pagesControl FundMhmd IrakyNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience 101 - 08jun13Document4 pagesNeuroscience 101 - 08jun13Yusuf PathanNo ratings yet

- Practice Makes PerfectDocument1 pagePractice Makes PerfectIsaiah AndreiNo ratings yet

- Limitless: Master the Art of Memory Improvement with Brain Training to Learn Faster, Remember More, Increase Productivity and Improve MemoryFrom EverandLimitless: Master the Art of Memory Improvement with Brain Training to Learn Faster, Remember More, Increase Productivity and Improve MemoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Learn Golf Template2Document9 pagesLearn Golf Template2Rob SmithNo ratings yet

- Toppers Chocie How-To-Improve-Your-MemoryDocument12 pagesToppers Chocie How-To-Improve-Your-MemoryPawan BabelNo ratings yet

- The Making of An ExpertDocument4 pagesThe Making of An ExpertBianca Mihaela ConstantinNo ratings yet

- Protocolos de NeurofeedbackDocument6 pagesProtocolos de NeurofeedbackDomingo Torres SNo ratings yet

- The Science of Choking Under PressureDocument9 pagesThe Science of Choking Under PressuregirishhodlurNo ratings yet

- Improve Mind PowerDocument11 pagesImprove Mind PowerGaurav UpadhyaNo ratings yet

- High Performance Sport Skill Instruction, Training, and Coaching. 9 Powerful Principles for Athletes to Flow and Get in the ZoneFrom EverandHigh Performance Sport Skill Instruction, Training, and Coaching. 9 Powerful Principles for Athletes to Flow and Get in the ZoneNo ratings yet

- The Four Essential Components of Deliberate PracticeDocument2 pagesThe Four Essential Components of Deliberate PracticeVvadaHotta100% (1)

- How To Study Quickly and Effectively - 2. Breathing ExercisesDocument3 pagesHow To Study Quickly and Effectively - 2. Breathing ExercisesfuzzychanNo ratings yet

- UltraMind ESP System Workbook - UDocument28 pagesUltraMind ESP System Workbook - Ucarol100% (1)

- 12 Tips For Learning Combatives or Any Other Skill Better Faster and More Easily Through Deep PracticDocument6 pages12 Tips For Learning Combatives or Any Other Skill Better Faster and More Easily Through Deep PracticBillLudley5No ratings yet

- LIMCHIU - ANAPHY 101 Module 4 Lets Call For A Destination CheckDocument4 pagesLIMCHIU - ANAPHY 101 Module 4 Lets Call For A Destination CheckKyle LimchiuNo ratings yet

- Mental GymnasticsDocument3 pagesMental GymnasticsKim QuỳnhNo ratings yet

- TRAINING SPRINTERS by Kevin O-DonnellDocument26 pagesTRAINING SPRINTERS by Kevin O-DonnellRegender15No ratings yet

- Gcse Pe Circuit Training CourseworkDocument5 pagesGcse Pe Circuit Training Courseworkphewzeajd100% (2)

- Cns WorkoutDocument22 pagesCns WorkoutSergioNo ratings yet

- Deliberate PracticeDocument3 pagesDeliberate PracticeEinah EinahNo ratings yet

- Eye Hand CoordinationDocument12 pagesEye Hand CoordinationCharles JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Neurobics:: The New Science of Brain ExerciseDocument1 pageNeurobics:: The New Science of Brain ExerciseFederico TorresNo ratings yet

- Double Your Natural Gains Type 2Document12 pagesDouble Your Natural Gains Type 2aligaram100% (1)

- Training Strategies For Concentration: Growth To Peak Performance, 5 Edition. Boston: Mcgraw Hill, 404-422Document25 pagesTraining Strategies For Concentration: Growth To Peak Performance, 5 Edition. Boston: Mcgraw Hill, 404-422RafaelAlejandroCamachoOrtega100% (1)

- Microteaching Lesson IdeaDocument2 pagesMicroteaching Lesson Ideaapi-497493358No ratings yet

- Training Strategies For ConcentrationDocument25 pagesTraining Strategies For Concentrationkabshiel100% (1)

- Hope 2 Q4 WK 56Document16 pagesHope 2 Q4 WK 56rogemariegamboaNo ratings yet

- Deliberate PracticeDocument36 pagesDeliberate PracticeBeowulf Odin Son100% (1)

- Neuroplasticity Protocol HubermanDocument4 pagesNeuroplasticity Protocol HubermanStar DeveloperNo ratings yet

- Boxing Training PlansDocument16 pagesBoxing Training PlansKevinNo ratings yet

- Gcse Pe Coursework RoundersDocument8 pagesGcse Pe Coursework Roundersafaybiikh100% (2)

- Coaching - TranscriptDocument14 pagesCoaching - TranscriptNicolas Riquelme AbuffonNo ratings yet

- Xsilva Ultramind's Remote Viewing and Influencing Guidebook PDFDocument35 pagesXsilva Ultramind's Remote Viewing and Influencing Guidebook PDFstrahld100% (2)

- Tennis Circuitry: Master the Software of a Professional Tennis PlayerFrom EverandTennis Circuitry: Master the Software of a Professional Tennis PlayerNo ratings yet

- A Joosr Guide to... Deep Work by Cal Newport: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted WorldFrom EverandA Joosr Guide to... Deep Work by Cal Newport: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted WorldNo ratings yet

- Memory Improvement, Accelerated Learning and Brain Training: Learn How to Optimize and Improve Your Memory and Learning Capabilities for Top Results in University and at WorkFrom EverandMemory Improvement, Accelerated Learning and Brain Training: Learn How to Optimize and Improve Your Memory and Learning Capabilities for Top Results in University and at WorkNo ratings yet

- Criteria For Associative RepertoireDocument1 pageCriteria For Associative RepertoireAnonymous 2HzrnXCNo ratings yet

- Think of YouDocument1 pageThink of YouAnonymous 2HzrnXCNo ratings yet

- Bebob Enclosures (Parker Hinges)Document3 pagesBebob Enclosures (Parker Hinges)Anonymous 2HzrnXCNo ratings yet

- The 3rd Messiaen Mode - Jens LarsenDocument4 pagesThe 3rd Messiaen Mode - Jens LarsenAnonymous 2HzrnXC100% (1)

- Metric Modulation ExampleDocument1 pageMetric Modulation ExampleAnonymous 2HzrnXCNo ratings yet

- A Winter Rose PDFDocument1 pageA Winter Rose PDFAnonymous 2HzrnXCNo ratings yet

- 3rd Symphony Copland Autograph Score PDFDocument71 pages3rd Symphony Copland Autograph Score PDFAnonymous 2HzrnXCNo ratings yet

- Basic PolyrhythmsDocument1 pageBasic PolyrhythmsAnonymous 2HzrnXC100% (1)

- Stars ScoreDocument19 pagesStars ScoreAnonymous 2HzrnXCNo ratings yet

- Arion PianoDocument3 pagesArion PianoAnonymous 2HzrnXC100% (1)

- WHLP PFA and Homeroom Guidance Week2Document2 pagesWHLP PFA and Homeroom Guidance Week2Ginno OsmilloNo ratings yet

- Guia 1 Inglés Quinto - 1st TermDocument12 pagesGuia 1 Inglés Quinto - 1st TermJohan AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Bentuk-Bentuk Pertanyaan Berdasarkan Taxonomy BloomDocument16 pagesBentuk-Bentuk Pertanyaan Berdasarkan Taxonomy BloomyoyokNo ratings yet

- P.E 1 DLP 2 Benefits Objectives and ImportanceDocument4 pagesP.E 1 DLP 2 Benefits Objectives and ImportanceCaruana Hazel-AnnNo ratings yet

- Cs Form No. 212 Attachment - Work Experience SheetDocument1 pageCs Form No. 212 Attachment - Work Experience SheetSonny Aguilar Jr.No ratings yet

- Fundamental Attribution ErrorDocument5 pagesFundamental Attribution ErrorFps KaiNo ratings yet

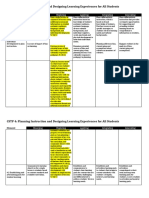

- CSTP 4: Planning Instruction and Designing Learning Experiences For All StudentsDocument6 pagesCSTP 4: Planning Instruction and Designing Learning Experiences For All StudentsHaley BabineauNo ratings yet

- Locations On A MapDocument2 pagesLocations On A Mapapi-244894096No ratings yet

- Expectancy Theory Vroom HR MotivationDocument2 pagesExpectancy Theory Vroom HR MotivationGideon MoyoNo ratings yet

- CSTP 3 Lecheler 12Document11 pagesCSTP 3 Lecheler 12api-468451244No ratings yet

- D-MCT Module 5 Thinking and Reasoning 3Document78 pagesD-MCT Module 5 Thinking and Reasoning 3GGNo ratings yet

- Appendix 1: Lesson Plan (Template)Document5 pagesAppendix 1: Lesson Plan (Template)bashaer abdul azizNo ratings yet

- Feedback ExamplesDocument2 pagesFeedback Examplesapi-237154393No ratings yet

- Listening LPDocument2 pagesListening LPRobertJohnPasteraNo ratings yet

- O.B Assignement MBA - May 2019 - Case Study v35Document4 pagesO.B Assignement MBA - May 2019 - Case Study v35ahmedNo ratings yet

- Frayer Model Template and GuideDocument2 pagesFrayer Model Template and Guideapi-402710096No ratings yet

- Behaviorism: Pavlov, Watson and SkinnerDocument19 pagesBehaviorism: Pavlov, Watson and SkinnerKaty Montoya100% (1)

- Ei PresentationDocument43 pagesEi PresentationRegine BulusanNo ratings yet

- Effect of Cognitive Dissonance On The Performance of Employees in Academic JobsDocument3 pagesEffect of Cognitive Dissonance On The Performance of Employees in Academic JobsAnonymous klP1LOCbNo ratings yet

- TPCK - Technological Pedagogical Content KnowledgeDocument3 pagesTPCK - Technological Pedagogical Content KnowledgeGlaiza Dalayoan FloresNo ratings yet

- Nature of Teaching: What Teachers Need To Know and Do: Bethel T. AbabioDocument12 pagesNature of Teaching: What Teachers Need To Know and Do: Bethel T. AbabioIbtissem HadNo ratings yet

- De Bono's I Am Right You Are Wrong: Informal Logic January 1992Document9 pagesDe Bono's I Am Right You Are Wrong: Informal Logic January 1992Swati DubeyNo ratings yet

- Communicative Approach - ChomskyDocument4 pagesCommunicative Approach - ChomskyMiss AbrilNo ratings yet

- LP Entre 11-21Document1 pageLP Entre 11-21Genelita B. PomasinNo ratings yet

- Study of Student Achievement 2Document23 pagesStudy of Student Achievement 2api-543821252No ratings yet

- Understanding and JaspersDocument12 pagesUnderstanding and Jaspersdakisb1No ratings yet

- Anxiety-Reducing Features Multimedia Online Math LessonDocument2 pagesAnxiety-Reducing Features Multimedia Online Math LessonThivenraj RavichandranNo ratings yet

- Wolgamuth Revised PTLDocument2 pagesWolgamuth Revised PTLapi-590350209No ratings yet

- ABC PPT CH 1Document30 pagesABC PPT CH 1mohammedNo ratings yet