Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 132.154.128.51 On Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 132.154.128.51 On Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

Uploaded by

Arshdeep Singh ChahalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 132.154.128.51 On Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

This Content Downloaded From 132.154.128.51 On Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

Uploaded by

Arshdeep Singh ChahalCopyright:

Available Formats

The Status of Rules of Precedent

Author(s): P. J. Evans

Source: The Cambridge Law Journal , Apr., 1982, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Apr., 1982), pp. 162-179

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of Editorial Committee of the

Cambridge Law Journal

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/4506418

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Cambridge Law Journal

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge Law Journal, 41 (1), April 1982, pp. 162-179

Printed in Great Britain.

THE STATUS OF RULES OF PRECEDENT

P. J. Evans*

In a recent article in the Cambridge Law Journal,1 Laurenc

stein argues that four problems of legal theory which are

to present elements of paradox are capable of a reasonably

solution. I am interested here in only one of the problems d

by Goldstein: that concerning the status of the rules of pr

I agree with Goldstein that this problem has a reasonabl

solution: but I disagree with the solution he proposes. (Broa

is that pronouncements on precedent do not establish rules

I propose in this short article to offer what I believe to be a

solution to this problem. The solution proposed is one w

already been suggested by A. W. B. Simpson in 1961 in " Th

Decidendi of a Case and the Doctrine of Binding Precedent"

there is, I believe, a defect in Simpson's formulation of the a

for it, which has impeded its general acceptance. In any ev

there is clearly still controversy about the issue, it seems wo

restating this solution with fresh arguments. I will first di

problem, then its proposed solution, then Simpson's discus

the topic, and finally some further questions which are su

by the proposed solution.

J. The Problem

As it seems to me, the problem which puzzles us about the sta

of rules of precedent is that of reconciling three apparently irr

cilable propositions, each of which seems to have good clai

support. The three propositions are:

(1) That rules of precedent are ordinary rules of law wh

impose duties identical to those imposed by any other d

imposing rules of law.

(2) That the authority of the rules of precedent cannot res

the rules of precedent themselves.

(3) That rules of precedent can be changed.

* Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Law, University of Auckland.

1 " Four Alleged Paradoxes in Legal Reasoning " [1979] C.L.J. 373.

2 Oxford Essays in Jurisprudence, ed. Guest (1961), p. 148.

162

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J.. Status of Rules of Precedent 163

Most discussions of this problem end up abandon

position 1 or proposition 3.3 The solution I will offe

of reconciling all three propositions. First, though,

case for each of the three propositions:

(a) Proposition 1

According to a view quite commonly put, rules o

not rules at all, but are simply " statements of jud

tradition."4 The implausibility of this view can be

we distinguish sharply between three different thi

might be doing in making pronouncements about

might be:

(i) making historical observations about what

practice is;

(ii) stating the effect of a rule which they believe already exists;

or

(iii) Iaying down (or participating in Iaying down) a rule which

is to apply in the future.

It may sometimes be unclear which of (ii) or (iii) judges believ

themselves to be doing in making such pronouncements, but it is

perfectly clear they do not consider themselves to be doing (i). Co

sider the following from Lord Halsbury in London Tramways Co.

Ltd. v. London County Council5:

My Lords, for my own part I am prepared to say that I adhere

in terms to what has been said by Lord Campbell and assente

to by Lord Wensleydale, Lord Cranworth, Lord Chelmsford

and others, that a decision of this House once given upon

point of law is conclusive upon this House afterwards, and tha

it is impossible to raise that question again as if it was re

integra and could be reargued, and so the House be asked t

reverse its own decision. That is a principle which has been, I

believe, without any real decision to the contrary, established

now for some centuries, and I am therefore of opinion that i

Thus, the following present views which involve abandoning proposition 1

Glanville Williams in Salmond on Jurisprudence (11th ed. 1957), pp. 187-188;

Hicks, "The Liar Paradox in Legal Reasoning" [1971] C.L.J. 275, 290; Lord

Denning in Davis v. Johnson [1978] 1 All E.R. 841, 855; Goldstein, supra,

n. 1 at p. 387. Goldstein does not, however, agree with the others that pro-

nouncements on precedent are mere statements of practice. He takes the view

that they are logically incoherent utterances. C E. F. Rickett in " Precedent in

the Court of Appeal" (1980) M.L.R. 136, 144, puts explicitly the view that

changes in the rules of precedent are revolutionary changes (a rejection of pro¬

position 3), though he suggests that in practice such changes will normally occur

very slowly. The views expressed by Roy L. Stone-de Montpensier in " Logic and

Law: The Precedence of Precedents" (1967) 51 Minnesota L.R. 655, perhaps

involve an attempt to reject proposition 2 (see also [1968] C.L.J. 35).

e.g. Glanville Williams, supra, n. 3.

[1898] A.C. 375,379.

C.L.J.—6 (2)

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

164 The Cambridge Imw Journal [1982]

this case it is not competent for us to rehea

to reargue a question which has been recent

Or this, from Lord Greene in Young v. Bristol A

On a careful examination of the whole matter we have come

to the clear conclusion that this court is bound to follow pre

vious decisions of its own as well as those of courts of co-

ordinate jurisdiction. The only exceptions to this rule (two o

them apparent only) are those already mentioned_

Or this, from Lord Goddard in R v. Taylor7:

This Court [the Court of Criminal Appeal]... has to deal w

questions involving the liberty of the subject, and if it finds,

reconsideration, that, in the opinion of a full court assembl

for that purpose, the lavy has been either misapplied or mis

understood in a decision which it has previously given, and th

on the strength of that decision, an accused person has be

sentenced and imprisoned it is the bounden duty of the cou

to reconsider the earlier decision with a view to seeing wheth

that person has been properly convicted.

The first two of these passages seem to belong under category (

above; the third passage might also be thought of as belonging un

(ii) if we interpret what is being said as the assertion of a rule wh

forms part of the law because of its merit; but it might also

treated as belonging under (iii). None of the passages belong und

(i). It is worth noting also that in so far as the judges believe the

selves to be doing (ii) (stating the effect of an existing rule), th

plainly believe that they are doing so in circumstances under whi

even if they are wrong, the effect of what they do will be to lea

behind a rule for the future. Doing (ii) and (iii) thus share t

feature that they leave a rule for the future. So the view that sta

ments about precedent are merely statements about judiciai pract

or tradition is clearly wrong as a statement about what judg

purport to do—they at least purport to be doing things which ha

the effect of leaving rules for the future.

It remains possible that judges are not doing what they purp

to be doing, so that only interest of what they do is as an histor

indication of the outlook of the time. There is, however, go

reason to believe that judges are doing what they purport to

doing, at least to the extent that they purport to be leaving behi

rules for the future. The crucial point is that later judges, a

lawyers generally, treat the " rules of precedent" as rules. When

judge finds himself bound by a precedent he treats himself as obli

• [1944] K.B. 718, 729.

7 [1950] 2 K.B. 368, 371.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Status of Rules of Precedent 165

to decide as the precedent requires, irrespective o

is a different approach from that which would be

were just an historical fact that judges generally fo

If that were the situation it would still be import

consider precedents, because whatever might be th

of an issue there would be important values to

following an earlier precedent, since people would r

because of the judges' practice. But under such a ci

values would have to be weighed against the disadva

ing the precedent. If the deficiencies of the preced

tial, or the chance of anyone relying on it in decid

of action were siight, then it might be best, all thi

refuse to follow it. Whatever might be the merit

treating precedents, it is not the method which we

As things presently are, we argue about whethe

applicable, and about whether they are binding und

rules of precedent, but because we accept these ru

do not argue about whether precedents should be f

they are applicable and of the right character to

the rules.

Another version of the theory that rules of pr

ordinary rules of law, which may seem more attr

of these considerations, is that rules of precedent

of practice.8 The trouble with this claim is that it

what is meant by " rules of practice." Presumably t

is to practice directions on matters such as the for

or the manner of taking preliminary steps in a tr

myself, see why these rules should not be called o

law. Perhaps they are always subject to some over

in the court to dispense with the requirement the

that is so I would be inclined to call them rules

cretion. It doesn't matter, however, for the presen

characterise these rules. Whatever may be true of

shown clearly that rules of precedent are just as m

as any other rules of the legal system. To facilitat

to this effect let me make a broad division betwe

types of rules which follow from a proper respect

8 The view that rules of precedent are rules of practice wa

in the first edition of Precedent in English Law (1961), p

Rickett in " Precedent in the Court of Appeal " (1980) M.

rules of precedent as " rules of practice," because they are p

recognition of the system. For reasons given in the text,

are part of the rule of recognition, but in any event (again

tho text) I would not consider this a good reason for treatin

other than full rules of law.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

166 The Cambridge Law Journal [1982]

First, we should allow for rules which are binding e

are not binding because of the rules of precedent. I hav

particularly rules which constitute a proper extension o

existing case9; but there is in fact an even clearer in

rules which were laid down by a lower court or an e

court not bound by its own decision, but which should

followed not just, or not at all, because of their m

important legal values such as protection of existing pr

dence in the stability of the law, are protected by thei

This leaves the broad class of rules which are bindin

rules of precedent. Among these we can distingu

would be binding in any event—because they woul

constitute the proper extension of another preceden

are non-binding cases which would justify adheren

cause the precedent establishing them merely corre

or applied an existing rule, or just because the

sound principle—and those which would not be

were not for these rules. We have, then, rules whi

only for reasons other than the rules of precedent,

binding for such reasons as well as because of the ru

and rules which are binding only because of the rul

For the moment let us concentrate on the third class. If we take

away from the rules of precedent the status of ordinary rules of l

then we must take it away also from all these more particular rul

by which judges are bound just because of the rules of precedent

The duties which judges have to observe these more particular rul

can not be of a different type from the duties imposed by the rul

of precedent since they are simply particular instances of this ver

duty: it is because, and only because, of the duty to follow the ru

of precedent that there is a duty to follow these more particula

rules. But there seems no good reason to treat these duties as dif

ferent in regard to their character as legal duties from duties imposed

by either of the other two classes of rules derived from cases, o

indeed any other rules of the system. Certainly the ground on wh

we recognise them to be legal duties is different, but this does n

constitute a difference in what we recognise them to be. They a

legal duties like any other legal duties—they form part of the syst

of requirements which go to make up a particular legal system. L

9 My belief that there are such rules is based on the view that judges are som

times bound, though not by the rules of precedent, to extend the ratio of

case beyond its expressed terms. This is argued more fully in a paper " On ca

law Reasoning " which I hope to publish shortly.

10 For discussion of these cases see; Jones v. Secretary of State [1972] A.C. 9

Knuller Ltd. v. D.P.P. [1972] A.C, 435; Cassell & Co. Ltd. v. Broome [1972]

A.C. 1027, per Lord Reid at 1086E.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Status of Rules of Precedent 167

us now consider the second class of rules—those

because of the rules of precedent as well as fo

is clear that a similar point can be made. In their

which are binding because of the rules of pre

impose duties which are just as fully legal dutie

by any other rules of the system. In both cases

function of the rules of precedent is to give rise

duties of law. We can conclude, then, that the f

sound.

(b) Proposition 2 (That the authority of the rules

not rest on the rules of precedent themselves

This proposition, which has been forcefully s

Williams,11 seems to me to need no supporti

proposition, it should be noted, as put here, i

precedent cannot be established by precedent dec

the authority of such precedents cannot rest

precedent themselves.

(c) Proposition 3 (That rules of precedent can be

At the present time it is a simple matter of

tion that the rules of precedent have been chang

occasions during the last century or so.

When Lord Halsbury stated in JLondon Tram

London County Council12 that the rule (or " prin

it) that the House of Lords is bound by its own

been established for some centuries, he seem

historically accurate. It would not, I think, be c

this rule was established by that case itself, but

to claim that it was first recognised by a court

v. Beamish.13 There appears to be no case pri

which the rule was asserted by the House; and i

have been universally accepted before that time

v. Hutton 14 there was disagreement between Lo

11 Supra, n. 2.

12 Supra, n. 5.

w (1859-61) 9 H.L.C 274.

14 (1852) 3 H.L.C. 341. It seems to me that in Bright v. Hutton the House did

in fact refuse to follow its earlier decision in Hutton v. Upfilt (1850) 2 H.L.C.

674; though it did not do so in so many words. In UpfilVs case it had been held

that a member of a provisional committee of a company who had accepted shares

alfotted to him was liable as a contributory on a windfog up of the company,

because these facts established a contract to be liable for expenses of the manage¬

ment committee in promoting the company. In Bright v. Hutton it was held on

facts admitted to be indistinguishable, that there was no contract, and hence no

liability as a contributory. The lords who spoke, treated UpfiWs case as a

decision on fact, and hence as not binding. Strictly, the finding in UpfilVs case

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

168 The Cambridge Law Journal [1982]

Lord Chancellor) and Lord Campbeli15 as to whether t

bound by such a rule. Lord Campbeli, who believed it

did not cite any authority for his view, but argued (i

such a rule followed from sound constitutional theory

Campbeli reasserted this view as Lord Chancellor

General v. Dean and Canons of Windsor9u in 1860, Lor

expressly reserved his opinion on the point.lf In

Beamish l8 however, Lord Campbeli won the day. W

first came before the House in 1859, the House direet

be argued on the assumption that R. v. Millisie (the re

decision) was a binding authority if applicable; and wh

gave its decision in 1861 each of the Lords asserted tha

not they approved of R. y. Millis they were bound by

Now it is, of course, possible that Lord Campbeli was r

the points on which his argument depends: (i) that

the House is bound by its own decisions follows from s

tutional theory, and (ii) that it was therefore part of t

it was recognised by the House. But Lord Campbell's a

the first point, though weighty, is not beyond challen

since the ratio of a House of Lords decision is binding

tribunals and on all the rest of the Queen's subjects, i

considered equally binding on the House itself, the Ho

arrogating to itself the right of altering the law and w

legislating by its own authority. Strictly, this is not just a

based on constitutional theory, but also on a view abo

use of cases as a source of law. It requires as a premise

tion that single decisions, irrespective of merits, are

authoritative source of law for lower courts. The argu

that if such decisions are not an authoritative source of law for the

court which made them, the law which binds lower courts is not

binding on higher courts. Lord Campbeli believed (reasonably

enough) that one body of law should be binding on all courts, and

he therefore concluded that higher courts should be bound by their

was not about what the facts were, or about the existence of a rule (the rule

that if there was a contract authorising expenses there was liability as a contri¬

butory was accepted in both cases), but about whether the agreed facts couid

be ciassified in a certain way so as to come within an agreed rule. (Such con¬

ceptual questions are often misleadingly spoken of as " mixed questions of law

and fact.") If findings on questions of this sort are not binding, so that the

only findings which bind courts are those about the existence of rules of law,

then there are a tremendous range of precedents normally assumed to be binding

which are not.

15 At pp. 388 and 392 respectively.

*• (1860) 8 H.L.C. 369, 391.

17 At. p. 459.

18 Supra, n. 14.

« (1844) 10 Q, & F. 534.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Status of Rules af Precedent 169

own decisions. It should be noted, however, th

even if accepted, can at best only mitigate, an

evil complained of. Whenever it is true that si

authoritative source of law and there are more than two tiers in

the structure of courts, it is inevitable that there will be decision

which are binding on some courts and not on others. For the lowest

tier of courts is bound by the second tier, and even if the second

tier is bound by its own decisions these decisions will not be binding

on the third tier. Since the evil is thus an inherent feature of the

conception that single decisions are binding on lower courts

long as there are more than two tiers of courts) we might reasona

judge it better to forgo that mitigation of the evil which can b

achieved by making higher courts bound by their own decisions

the advantages of leaving the higher courts free in a wider ran

of cases to reconsider unsatisfactory precedents. Still, even if L

Campbell was right on this point, so that the view that the Hou

of Lords is bound by its own decisions was a proper consequence

the view that single decisions, irrespective of their merits, are bindin

on lower courts, and even if one is willing to accept (as I would

willing to) that it therefore formed part of the law from the accept

ance of this conception, it cannot have ante-dated that concepti

and it seems plausible to claim this was a nineteenth-century develop

ment.20 So even if he was right on both points that only pushes b

a little the origin of the rule that the House of Lords is bound

its own decisions, and makes the time of its origin more vague

As is well known, the rule thus established in the nineteenth

century was abandoned in 1966, and the House has since acted o

the view that it is not bound by its own previous decisions.21 On

point, then, the rules of precedent have changed twice within

space of around 150 years.

Somewhat similar points can be made about the rule that

20 On this see C. K. AUen, Law in the Making, 7th ed. (1964), pp. 210 et

Goodhart, "Precedent in English and Continental Law*' (1934) 50 L.Q.R.

"Case Law: a Short Replication" ibid. 196; Holdsworth, "Case Law" (193

50 L.Q.R. 180, "Precedents in the Eighteenth Century" (1935) 51 L.Q.R. 44

C. K. Alien, "Case Law: an Unwarrantable Intervention" (1935) 51 L.Q.

333; Lord Wright, "Precedents" [1943] C.L.J. 1. A clear sense of the early 19

century position can be derived from Ram, The Science of Legal Judgm

(1834), Chaps. 14 and 18. That rules of precedent may sometimes requi

lower court to adhere to something which is not the law so far as citizens ar

concerned (if we take it the law for citizens is the law which should be appl

by the highest court) is clearly recognised by Stephens J. in Viro v. The Qu

18 A.L.R. 257 at 289-335. I do not accept what the learned judge there se

to suggest, that there must be a " sanction " (of possible reversal) to supp

rules of precedent. (Cf. Jenkins, Correspondence (1981) 1 Legal Studies 340

is inconsistent with the judge's own view that a final court may bind itself

follow its own decisions. Ibid., p. 290.

21 E.g., in Miliangos v. George Frank (Textiles) Ltd. [1976] A.C. 443.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

170 The Cambridge Law Journal [1982]

Court of Appeal is bound by its own previous dec

from the time of the establishment of the modern

by the Judicature Act in 1873, there is a period l

1890s in which the court does not seem to have t

approach to its own earlier decisions, or those of

In 1880, in Mills v. Jennings22 the court departed

of the old Court of Appeal in Chancery stating th

were not uncommon in that court itself. In the Vera Cruz No. 223

in 1884 the court declined to follow one of its own previous decisions

where the decision merely affirmed the decision in the court below

because the Court of Appeal was equally divided. Brett M.R. expres¬

sed the view that the comity among judges which is the ground of

the rule that a court should follow its own previous decisions, or

those of a court of co-ordinate jurisdiction, did not apply in such a

case. In 1886 Lord Esher (as Brett M.R. then was) called together

the full court in Ex parte Stanford24 to review a rule of construction

previously laid down in several decisions as to the meaning of the

term "in accordance with the form" in section 9 of the Bills of

Sale Act 1882 which made bills of sale not ** in accordance with th

form " void. At least one of those earlier decisions, Roberts v

Roberts,25 was a decision of the Court of Appeal and it is clear t

new rule laid down differed from the rule followed in that case. The

course of action taken is explained and justified by Lord Esher in

Kelly & Co. v. Kellond.2* In later discussion of this topic that case

itself was mistakenly thought to be a case in which the full court

had been called to reconsider an earlier decision27; but when in

that case Lord Esher says28:

This Court is one composed of six members and if at any time

a decision of a lesser number is called in question, and a diffi¬

culty arises about the accuracy of it, I think this Court is

entitled, sitting as a full Court, to decide whether we will follow

or not the decision arrived at by the smaller number.

he plainly means by " This Court," not the court presently sitting,

but the whole permanent composition of the Court of Appeal at

that time. He is thus explaining why the court presently sitting is

bound by the rule laid down in Ex parte Stanford (it is bound because

the full court had power to overrule Roberts v. Roberts); and is not

describing the course being taken in the current case. In fact the

22 (1880) 13 Ch.D. 639. 23 (18g4) 9 PJD# 96.

24 (1886) 17 Q.B.D. 259.

25 (1884) 13 Q.B.D. 794.

26 (1888) 20 Q.B.D. 569,571.

27 See, e.g.t Lord Greene in Young v. Bristol Aeroptane Co. Ltd. [1944] K.B.

718, 727.

28 ibid., at p. 572.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Status of Rules of Precedent 171

court in Kelly & Co. v. Kellond was not a full

only three members. During the 1890s a more r

to have emerged. In Pledge v. Carr,29 in 1895

refused to consider overruling an earlier decisio

Appeal in Chancery because it was a decision

ordinate jurisdiction; and in the same year, i

County Council,30 Lindley L.J. expressed the view

strictly bound by an earlier decision of the Cou

In 1903 the procedure of calling together a full c

more to reverse an earlier decision of a court of a lesser number 31;

but this was the last time. The general hardening of attitude then

proceeded. Two cases in 1914 and 1915 respectively Velazquez Ltd.

v. Inland Revenue Commissioners32 and Produce Brokers Co. Ltd.

v. Olympia Oil & Coke Co. Ltd.33 show clearly that courts of a

single division at that time were not willing to reconsider earlier

decisions, irrespective of the merits of those decisions. At this point

one might have thought the question was settled with regard to a

single division; but in 1929,34 and in 1938,35 Greer L.J. relied upon

the cases in which a full court had reversed a decision of a single

division to argue that what a full court could do, a single division

could do, there being no difference in jurisdiction between the two.

Finally, in Young v. Bristol Aeroplane Co. Ltd., in 1944,36 Lord

Greene, giving the judgment of the court, used Greer L.J.'s argu¬

ment in reverse, to assert that since a single division could not

reverse an earlier decision neither could a full court. As a summary

of this, it seems reasonable to say that the rule that a single division

could not reverse an earlier decision was established probably as

early as 1895, and certainly by 1914, and the rule that a full court

cannot do so, was established by YoungJs case itself in 1944.

The uniform rule thus settled in Young's case has not, of course,

been changed up to the present time. But it seems fair to assert

that it could be—though whether the power to make such a chang

lies with the Court of Appeal itself, or with the House of Lords, or

both, is a question which is at present not entirely clear.37

29 [1895] 1 Ch. 51. 30 [1895] 2 Q.B.D. 577.

si Wynne-Finch v. Chaytor [1903] 2 Ch. 475. 32 [1914] 3 K.B. 458.

33 [1915] 21 Com.Cas. 320.

34 Newsholme Bros. v. Road Transport & General Insurance Co. [1929] 2 K.B.

356, 384.

35 In re Shoesmith [1938] 2 K.B. 637, 644. 36 [1944] k.B. 718.

37 On this point see the following passages in Davis v. Johnson [1979] A.C

and further cases cited therein: Lord Denning M.R. at pp. 281 et seq.', G

L.J. pp. 293G-295F; Cumming-Bruce L.J. at pp. 311G; Viscount Dilhorne

336F; Lord Salmon at p. 344A-F;also Attorney-General v. Reynolds [1

A.C. 637, 659F. See also Cross " The House of Lords and the Rules of Prec

dent." In Law. Morality and Society: Essays in Honour of H. L. A. Har

Hacker and Raz (1977), pp. 145, 151-153.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

172 The Cambridge Law Journal [1982]

It is plain, then, that the rules have been chan

of occasions in the past. This in itself does not sh

be changed legally9 for it might be that the jud

number of silent revolutions. We must consider,

these changes were legally made.

If one Iooks back at the changes two things ar

apart from the declaration in 1966, the judges d

be exercising a power to change the rules. They

they were upholding a tradition which had stoo

Lord Halsbury in London Tramways Ltd. v. London County

Council) or as if they were recognising rules which had to be recog¬

nised because they were grounded in sound argument (Lord Camp¬

beli in Bright v. Hutton, and Lord Goddard in R. v. Taylor). The

judges did not apparently see themselves as free to make change.

But the second thing which is striking is that the judges clearly did

believe themselves to be able to settle these issues, and since being

able to settle an issue implies being able to settle it wrongly as well

as rightly, if their belief was correct they did in fact have the power

to make change. The correct way, it seems, to state the position in

which the judges believed themselves to be is that they possessed a

power to make change—as an incident of the power to settle issues

concerning the rules—but that they had a duty not to exercise this

power—since their duty was simply to recognise pre-existing rules.

Can we now move from this analysis of the judges* belief to a

statement about what was the law? It seems to me we can. The

view the judges held was plainly not idiosyncratic, but was share

by other judges and by the legal profession as a whole. That

evidenced by the willingness of later judges and lawyers to treat

these decisions as decisive on the points they purported to settle

Now unless all these people were incorrectly drawing conclusions

from some more basic premises—which seems implausible—then t

state in which the judges believed was in fact the law.

If then, all of these propositions are sound our next task mus

be to try to reconcile them.

II. The Suggested Solution

A reconciliation between propositions 1 and 2 can be achiev

treating rules of precedent as basic rules—as part of the grun

or rule of recognition of the legal system. The position woul

be that the authority of rules of precedent would not depend

precedents or any other source of authority, but merely upon

acceptance as part of the ultimate source of authority of the

system. This solution is blocked, however, by proposition 3,

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.I. Status of Rules of Precedent 173

a rule of recognition cannot be changed. As th

of a system is the ultimate test of legal validity

if a different rule of recognition is asserted there

by virtue of which it is valid. Vis-a-vis the old

it must be invalid. Thus any change of a rule o

be revolutionary.

The way to reconcile propositions 1 and 2 wi

to postulate as the relevant part of the rule of

rules of precedent themselves, but a rule which

justifies as a particular conclusion, that the jud

to time settle the rules of precedent. Such a

judges power to make rules of precedent wh

binding until such time as these rules were chan

of course, a question of detail just which judge

regard to each particular aspect of the rules.

If this view of the rules of precedent is correct

that the judges of at least the highest court can

on themselves which they are also free at any t

may seem disturbing, but it is not such an odd

appear. Even a single individual can make rules

he is at any time free to change. If I make a ru

6.30 every morning and do my exercises, then i

to abandon this rule, and quite another for me

it on a particular occasion. In any event, sinc

court must act as a body to make changes in th

it makes perfectly good sense to say that the

make a rule which is binding on each individ

change is made by a further collective decision

This then is the solution which I propose to

status of rules of precedent. They are rules mad

of a more basic rule.

III. Simpson's Argument for this Solution

As I have said, essentially this solution to the problem was proposed

by A. W. B. Simpson in 1961.38 I now turn to consider Simpson's

arguments.

Simpson argues (correctly in my view) that it only makes sense

to say that the House of Lords can put itself under an obligation

to obey its own decisions if one assumes that there is a rule which

gives the House this power. Unfortunately, however, he treats the

possibility of such a rule as a valid argument against Glanville

38 " The Ratio Decidendi of a Case and the Doctrine of Binding Precedent,"

supra, n. 2.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

174 The Cambridge Law Journal [1982]

Williams's claim that the rules of precedent canno

own authority. It is not: though it is a good argum

conclusion which Glanville Williams draws from th

decisions on precedent cannot establish rules of law

The relevant passage in Simpson's article is the f

Now the most usual reason for citing the Lon

case is to justify an argument about a specific c

for example, that the House is bound by the dec

v. Fletcher. In such an instance there is no circ

method of justification. It is only when the

justify an argument that London Tramways

County Council is binding that Dr. Williams find

tion circular. But are those who use such an arg

accused of circularity or question-begging? The

be set out thus:

(1) The House of Lords has power to make rulings about

the status of its own decisions, whether they are binding

or not.

(2) In London Tramways Ltd. v. London County Council

the House in exercise of this power ruled that all its

own decisions, unless given per incuriam or in ignorance

of a Statute, are binding.

(3) The decision in London Tramways is a decision of the

House of Lords and is therefore binding.

The argument does not assume what it seeks to prove; it assumes

that the House has a power to rule whether its decisions are

binding or not binding, and proves that they are binding.

Given that the reasoning set out is intended to refute Glanville

Williams, one might take (3) here to mean that the decision in

London Tramways, on the point of precedent, is binding because

of the decision in that very case (Le., because of the decision referred

to in (2) ). This reasoning would clearly be circular. But this is not,

I think, what Simpson means. What I take it he means by (3) is

that the decision in London Tramways is binding because it consti¬

tutes an exercise of the power referred to in (1). On this interpreta¬

tion, the reasoning is not circular, but perfectly valid. An exercise

of the power referred to in (1) must be taken, of course, to apply

only de futuro; so that there can be no suggestion that the House,

by ruling that its own decisions are not binding, can make it the case

that its decisions were not binding at a time when a contrary ruling

prevailed. (This, I believe, removes the element of self-contradiction

which Goldstein, in the article I mentioned at the outset,40 claims

39 At p. 152. I have changed the name of the appellant in the quotation from

London Street Tramways Ltd. to London Tramways Ltd., taking account of the

errata at the front of (1898) A.C.

<° Supra, n. 1 at p. 389,

This content downloaded from

fff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.LJ. Status of Rules of Precedent 175

to see in this reasoning.) It ought also to be c

referred to in (1) does not give the House powe

of this very power by ruling that some decisio

has this power is not binding. Since that decisi

been the source of the power, a ruling stating

not binding would not affect the power.41 If,

reasoning is interpreted in this way, it cannot b

argument against Glanville Williams. What Sim

if one accepts the existence of a rule of higher

of precedent, the London Tramways' case could

cited as an authority for the rule that the Hou

own previous decisions because the decision in it

cise of the power given by that higher-order ru

that the case could be cited as an authority for

because of that very rule itself. Since it is only

that Glanville Williams's complaint is addressed,

this complaint unaffected. Glanville Williams wa

that rules of precedent cannot rest on their ow

simply wrong (for reasons indicated by Simpso

clusion from this that decisions about precedent

of law.

IV. Some Problems Raised by this Solution

I will now discuss two problems which are rais

The first is this. If we say that at a time in hist

than 1966 the courts were under a duty not to

precedent (which, as we have seen, was assumed

that time), then what are we to say of the House

in that year of a freedom to change the rules cons

that this at least was a revolutionary change? The a

this seems strong. If this duty formed part of the

then plainly it could not legally be changed. Fu

might posit (though not very plausibly) a basic r

this duty so far as the House of Lords was conce

itself explicitly proclaimed that it was free fro

explicit act occurred. All that we are left with if w

path is the notion of a duty which disappears

observed—and that makes no sense.

I do not think, however, that this conclusion

41 If the court did have this power the basic rule woul

justified a conclusion that the court can determine wha

are until it itself deprives itself of this power. The reas

clearly m relation to a similar problem by Alf Ross in *

a Puzzle in Constitution Law " (1969) 78 Mind 1.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

176 The Cambridge Law Journal [1982]

the premises necessary to avoid it are of an interes

I contend is that the basic commitment in the com

as the use of cases as a source of law is concerned,

just to a specific set of rules but has always includ

residual element, a commitment to that solution o

best promotes the common good. I shall here use an

and refer to this as the solution which reason requ

is to be plausible it is important that I should be c

cisely what is being claimed. First, I do not clai

criterion of validity for propositions based on case

unchanged through the whole history of the law. It

it has changed from time to time. All I claim is th

basic commitment has been at any given time it has alw

least a commitment to the solution reason require

concerning what the criterion should be: that i

questions of evaluation not settled in that part of t

previously accepted as settled. Secondly, I do not c

present time this is the only ultimate criterion of

is, I think, a settled part to the doctrine of prece

sently have it which is immune from legal challeng

of its reasonableness. This is the rule that, loosely

single decisions of higher courts are binding on

taken, that is, as a rule which applies at least unti

changed by a ruling of the highest court. It is pos

that rule first entered the law its claim to recogni

to depend on its reasonableness. In fact I do not th

but that it entered through a nineteenth-century m

of the earlier law. But even if it was so, it seems p

has not been so conceived for well over 100 years.

the responsibilities of a present-day judge, it is not

legitimate to go back to early stages of legal histo

establish that there are conflicts within the tradition about the basic

commitment of a judge, and then to suggest that a judge may choose

between these conflicting conceptions. The whole point of a com¬

mitment to a past system, which is to ensure uniformity and con-

stancy in judgment, suggests that if there are conflicts of this sort

within the tradition it is the more recent part of it which must

prevail. The common law assumption for upward of 100 years, I

contend, has been that the responsibility of a judge to follow deci¬

sions of higher courts is simply a basic premise of the system. So

even if it can be argued, as I think it can, that reason requires that

any single judge should observe this rule while a general commit¬

ment to it remains, it is not as resting on that premise that it

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Status of Rules of Precedent \11

presently forms part of the law. But on novel point

there can in fact be conscious change of this ru

that the basic commitment in the common law

which reason requires. Thirdly, I do not claim t

legal validity has the same degree of explicit re

the rule that lower courts are bound by decision

What I claim is simply that this basis is assumed

arise, and that it is understood to be in accordanc

that it should be.

Let us turn now to the problem of the 1966 d

claim I have made is correct, then the follow

given of the changes discussed in this article. We

time, whenever it occurred, that it became gen

single decisions of higher courts were bindin

irrespective of merits. Once that was accepted,

necessary to work out the implications of this f

relation to their own previous decisions. Obviou

that judges should be able to rule on this, and o

tentious issues regarding the rules which should

those rulings once made should be accepted. Bec

able, it formed part of the law that those ruling

but once such rulings had been made an unus

for there could be no correcting of these rulin

sense. Though one might say at a later time tha

got things wrong, the law after their decision

they ruled it to be. So if later judges were limi

the law was at their time, then, apart from the

lative change, the system would be locked irreve

of things brought about by these rulings. Since

be an unsatisfactory state, what reason seem

that there should then arise a liberty to change t

Two objections, however, might possibly be mad

conclusion concedes a freedom in the judges

whereas it is by tradition felt that their role is

and secondly, the concession of such a freedom

claimed, against the concept of parliamentary s

first objection, my answer is that it remains de

liberty even though it can not be denied that

change the law. In these unusual circumstances,

there should be such a liberty. On the second, it is t

of parliamentary sovereignty is taken to imply

powers within the state to change the law ex

delegated by parliament, it is misconceived. Ther

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

178 The Cambridge Law Journal [1982]

other powers—the prerogative powers, for instance

power of the courts to control their procedure. Pa

ride or take away these powers, but if the prop

of our basic premises justifies the existence of a p

pertinently here, the liberty to exercise a power, then

parliament removes it. If, then, this argument is co

ful under the pre-existing law for the House of L

change which it did in 1966.

The second problem is this. I have spoken so far

having power to alter the rules of precedent, b

imprecise notion: how do we decide, on points

judges have this power in regard to any particu

they must act to exercise it? The general answer

should be clear from what I have just said: on poi

we must look to the answer which reason requires,

this to which our tradition commits us. On the

question, how the power must be exercised, the an

also relatively simple. There is no established conv

judges change the rules of precedent they must fol

form, and there seems no reason why there should be

So long as the court acts by a majority it seems

clearly indicating its intent should be effective, w

is expressed in the course of a case or not, and wh

forms part of the ratio decidendi of a case. (It ma

desirable, as the House of Lords seems to have f

to avoid impact on the parties to a dispute it shoul

of a case.) But the question who possesses the pow

particularly with regard to lower courts. I will con

to one problem: does the authority to change the r

of Appeal is bound by its own decisions belong

Court of Appeal itself, to the House of Lords, or t

If we apply the test of reason to this question it

answer is as follows. The Court of Appeal itself is

tion to judge by constant experience the advantag

ages of the rule. Further, it itself first laid down t

there is no tradition that only the House of Lords

the rules affecting this court. On these grounds it

nised that the Court of Appeal can change the

to, the power to do so being exercisable by a majo

manent members. There seems no reason, thoug

possess this power exclusively. Because of its role

visor of the law, the House of Lords should also b

42 See supra, n. 37.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

C.L.J. Status of Rules of Precedent 179

the rule if it chooses to. That, it seems to me, i

to this question; and if that is so, then on the v

is presently the law on this topic. Still it is not

be the law under all circumstanees. If a major

Lords were to express a contrary view, ruling in

it alone was entitled to change this rule, then I

it is desirable that the House should be able to m

on any point of law its decision should be decis

less complete picture is this: both the Court of A

of Lords presently possess a power to change

possess a liberty to exercise it; the House of

this position by ruling that it was for it alone to m

in this circumstance it would certainly deprive t

of its liberty, and probably also (though the

consideration), of the power itself.

This content downloaded from

132.154.128.51 on Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:49:49 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- GOODHART, Arthur L. Determing The Ratio Decidendi of A Case. The Yale Law Journal. v. 40. N, 2. New Haven.Document24 pagesGOODHART, Arthur L. Determing The Ratio Decidendi of A Case. The Yale Law Journal. v. 40. N, 2. New Haven.Victor MirandaNo ratings yet

- Editorial Committee of The Cambridge Law JournalDocument19 pagesEditorial Committee of The Cambridge Law JournalVarun SenNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of PrecedentDocument22 pagesDoctrine of PrecedentmuhumuzaNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes (NP)Document22 pagesLecture Notes (NP)Anhaita AnyaNo ratings yet

- GoodhartDocument24 pagesGoodhartIshwar MeenaNo ratings yet

- Scots Philosophical Association, Oxford University Press, University of St. Andrews The Philosophical Quarterly (1950-)Document11 pagesScots Philosophical Association, Oxford University Press, University of St. Andrews The Philosophical Quarterly (1950-)VishalNo ratings yet

- Stanford Law ReviewDocument36 pagesStanford Law ReviewMike LlamasNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Renvoi in Australia: Creating The Theoretical FrameworkDocument24 pagesThe Rise of Renvoi in Australia: Creating The Theoretical FrameworkLavanyaa AneeNo ratings yet

- Case Law and Stare Decisis - Concerning ÇáPr+ñjudizienrecht in Amerika Çá Author(s) - Max Radin - CertaintyDocument15 pagesCase Law and Stare Decisis - Concerning ÇáPr+ñjudizienrecht in Amerika Çá Author(s) - Max Radin - Certaintyjkmu113rNo ratings yet

- Goodhart 1930Document24 pagesGoodhart 1930Joffily OrbanNo ratings yet

- Kermit Roosevelt III - A Little Theory Is A Dangerous Thing. The Myth of Adjudicative RetroactivityDocument65 pagesKermit Roosevelt III - A Little Theory Is A Dangerous Thing. The Myth of Adjudicative RetroactivityjoshNo ratings yet

- Determining The Ratio Decidendi of A Case (Goodhart) (40 YALE L. J. 161) PDFDocument23 pagesDetermining The Ratio Decidendi of A Case (Goodhart) (40 YALE L. J. 161) PDFmNo ratings yet

- The Law and The FactsDocument14 pagesThe Law and The FactsNaman SharmaNo ratings yet

- IJLS Vol 1 Issue 2 Article 3 OMahonyDocument45 pagesIJLS Vol 1 Issue 2 Article 3 OMahonyRog DonNo ratings yet

- The Nature of EquityDocument15 pagesThe Nature of EquityKhalid Khair100% (1)

- Note On Stare DecisisDocument5 pagesNote On Stare Decisisanandh88No ratings yet

- ILS MT Essay - Teodora DimitrovaDocument4 pagesILS MT Essay - Teodora DimitrovaTDNo ratings yet

- Lord Bingham, The Rule of Law, Cambridge Law Journal PDFDocument20 pagesLord Bingham, The Rule of Law, Cambridge Law Journal PDFLEE KERNNo ratings yet

- 03 Judicial PrecedentDocument19 pages03 Judicial PrecedentgreavurNo ratings yet

- The Yale Law Journal Company, IncDocument24 pagesThe Yale Law Journal Company, IncKakunguluNo ratings yet

- Eng Leg SysDocument6 pagesEng Leg SysworterrsNo ratings yet

- Topical Aff Must Be Legislation - Judicial Action Is Not T Establish Means Legislate - Courts Only Rule On Established Law Webster's 10Document33 pagesTopical Aff Must Be Legislation - Judicial Action Is Not T Establish Means Legislate - Courts Only Rule On Established Law Webster's 10Clayton RussoNo ratings yet

- Ridge v. Baldwin and Nat JusDocument5 pagesRidge v. Baldwin and Nat JusVishalNo ratings yet

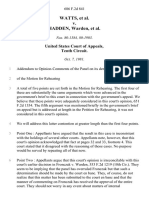

- Watts v. Hadden, Warden, 686 F.2d 841, 10th Cir. (1981)Document3 pagesWatts v. Hadden, Warden, 686 F.2d 841, 10th Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Moot Court BasicsDocument5 pagesMoot Court Basicsanushka kashyapNo ratings yet

- Unjust Enrichment ClaimsDocument28 pagesUnjust Enrichment ClaimsDana AltunisiNo ratings yet

- Stare DecisisDocument4 pagesStare Decisismina villamorNo ratings yet

- Question 6Document2 pagesQuestion 6Ara ShuzanNo ratings yet

- Stare DecisisDocument6 pagesStare DecisisAssignmentLab.comNo ratings yet

- Judicial PrecedentDocument5 pagesJudicial PrecedentJaycee HowNo ratings yet

- Modern Law Review - November 1957 - Montrose - The Ratio Decidendi of A CaseDocument9 pagesModern Law Review - November 1957 - Montrose - The Ratio Decidendi of A Casebsoc-le-05-22No ratings yet

- The Use of Contemporaneous Circumstances and Legislative History in The Interpretation of Statutes in MissouriDocument12 pagesThe Use of Contemporaneous Circumstances and Legislative History in The Interpretation of Statutes in MissouriShing MiNo ratings yet

- Judicial Discretion DworkinDocument16 pagesJudicial Discretion DworkinOrlando AlarcónNo ratings yet

- Mujih, Piercing The Corporate Veil As A Remedy of Last Resort After Prest V Petrodel Resources LTDDocument18 pagesMujih, Piercing The Corporate Veil As A Remedy of Last Resort After Prest V Petrodel Resources LTDLisa RishardNo ratings yet

- Topic 2 - Common Law ReasoningDocument20 pagesTopic 2 - Common Law ReasoningIsaNo ratings yet

- PWS Sources of Hong Kong Law CH 2Document11 pagesPWS Sources of Hong Kong Law CH 2HN WNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Judicial PrecedentDocument30 pagesDoctrine of Judicial PrecedentRafid Amer JimNo ratings yet

- The Practical Difference Between Natural-Law Theory and Legal PositivismDocument33 pagesThe Practical Difference Between Natural-Law Theory and Legal PositivismMEtrowill Siu100% (1)

- The Tort Rule of Private International Law-The Chimera Incarnate?Document41 pagesThe Tort Rule of Private International Law-The Chimera Incarnate?Nishant Navneet SorenNo ratings yet

- Hart-The Ratio Decidendi of A CaseDocument8 pagesHart-The Ratio Decidendi of A CaseSophie Aimer67% (3)

- Sunstein Cass - Testing Minimalim - A ReplyDocument8 pagesSunstein Cass - Testing Minimalim - A ReplyJuan Sebastián BaqueroNo ratings yet

- Why Judges Must Make LawDocument32 pagesWhy Judges Must Make LawMayuresh DalviNo ratings yet

- Briggs - in Praise and Defence of RenvoiDocument9 pagesBriggs - in Praise and Defence of RenvoiKent GohNo ratings yet

- Stare Decisis - A Dissenting ViewDocument11 pagesStare Decisis - A Dissenting ViewSadhvi SinghNo ratings yet

- TAQBIRDocument7 pagesTAQBIRismailnyungwa452No ratings yet

- Prospective OverrulingDocument52 pagesProspective OverrulingjacoboboiNo ratings yet

- SSRN-id2291141 3Document28 pagesSSRN-id2291141 3the junkNo ratings yet

- Essay On Do Judges Make LawDocument6 pagesEssay On Do Judges Make LawMahmudul Haque DhruboNo ratings yet

- Grounds For Review (3) : Procedural Impropriety: Aims and ObjectivesDocument14 pagesGrounds For Review (3) : Procedural Impropriety: Aims and Objectivesmohamm3dNo ratings yet

- Recent Decisions Offending Stare Decisis inDocument12 pagesRecent Decisions Offending Stare Decisis inAfiqNo ratings yet

- PrecedentsDocument7 pagesPrecedentsPreranaNo ratings yet

- Justice and Legal ReasoningDocument27 pagesJustice and Legal ReasoningmartinsskylarNo ratings yet

- In Praise and Defence of RenvoiDocument8 pagesIn Praise and Defence of RenvoiAvani SasindranNo ratings yet

- Ratio Decidendi and Obiter Dictum: Introductory RemarksDocument13 pagesRatio Decidendi and Obiter Dictum: Introductory RemarksShanen Lim0% (1)

- THE of Law For Tort Liability in The Conflict of Laws : ChoiceDocument18 pagesTHE of Law For Tort Liability in The Conflict of Laws : Choiceqaziammar4No ratings yet

- (Columbia Law Review 1964-Dec Vol. 64 Iss. 8) Review by - Edgar Bodenheimer - Essays On Jurisprudence From The Columbia Law Review (1964) (10.2307 - 1120771) - Libgen - LiDocument8 pages(Columbia Law Review 1964-Dec Vol. 64 Iss. 8) Review by - Edgar Bodenheimer - Essays On Jurisprudence From The Columbia Law Review (1964) (10.2307 - 1120771) - Libgen - Likuldeepchamar218No ratings yet

- LAWD10016-Cownie Fiona-English Legal System in Context-English Legal Reasoning The Use of Case Law-Pp81-100 PDFDocument12 pagesLAWD10016-Cownie Fiona-English Legal System in Context-English Legal Reasoning The Use of Case Law-Pp81-100 PDFMaxHengTsuJiunNo ratings yet

- Schauer CommonLawLaw 1989Document18 pagesSchauer CommonLawLaw 1989Moe FoeNo ratings yet

- Criminal Liability of RobotsDocument7 pagesCriminal Liability of RobotsArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Peer-Reviewed Journals and Quality Author(s) : Katherine Swartz Source: Inquiry, Summer 1999, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Summer 1999), Pp. 119-121 Published By: Sage Publications, IncDocument4 pagesPeer-Reviewed Journals and Quality Author(s) : Katherine Swartz Source: Inquiry, Summer 1999, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Summer 1999), Pp. 119-121 Published By: Sage Publications, IncArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 132.154.128.51 On Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:44:54 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 132.154.128.51 On Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:44:54 UTCArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 132.154.128.51 On Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:45:24 UTCDocument5 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 132.154.128.51 On Fri, 11 Sep 2020 05:45:24 UTCArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Seminar, Conference, Workshop and SymposiumDocument8 pagesSeminar, Conference, Workshop and SymposiumArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Countries With Which India Has Extradition TreatiesDocument3 pagesCountries With Which India Has Extradition TreatiesArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Mil's UtilityDocument18 pagesMil's UtilityArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Astronomical Society of The Pacific Publications of The Astronomical Society of The PacificDocument4 pagesAstronomical Society of The Pacific Publications of The Astronomical Society of The PacificArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Plagiarism Scan Report: Plagiarised UniqueDocument2 pagesPlagiarism Scan Report: Plagiarised UniqueArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- China Virus Death Toll Jumps To 106: Globe TrotDocument1 pageChina Virus Death Toll Jumps To 106: Globe TrotArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Syllabus of Pil (Notes On Extradition and Asylum)Document11 pagesSyllabus of Pil (Notes On Extradition and Asylum)Arshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The Concept of Caveat EmptorDocument5 pagesAn Analysis of The Concept of Caveat EmptorArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Book Review of Gender and Human Rights in Islam AnDocument4 pagesBook Review of Gender and Human Rights in Islam AnArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Unit 2: Political and Legal Environment of BusinessDocument9 pagesUnit 2: Political and Legal Environment of BusinessArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Long TermImpactsOfTheSeriesOf1970 - PreviewDocument43 pagesLong TermImpactsOfTheSeriesOf1970 - PreviewArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Randall CollinsDocument20 pagesRandall CollinsArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- 07 - Chapter 2Document15 pages07 - Chapter 2Arshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

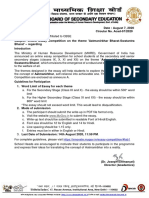

- WWW - Mygov.In: Shikshasadan', 17, Rouse Avenue, Institutional Area, New Delhi - 110002Document3 pagesWWW - Mygov.In: Shikshasadan', 17, Rouse Avenue, Institutional Area, New Delhi - 110002Arshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Potpourri: Fuqmt #1, Fuqmt #2, No Pot Only Puri, Rmikanni, Fetish, AbsenteecfDocument16 pagesPotpourri: Fuqmt #1, Fuqmt #2, No Pot Only Puri, Rmikanni, Fetish, AbsenteecfArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Rule of Caveat Emptor: (Justice ® Dr. Munir Ahmad Mughal)Document22 pagesRule of Caveat Emptor: (Justice ® Dr. Munir Ahmad Mughal)Arshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- ICC Moot Court Competition International Rounds Finalists Defence Memorial PDFDocument44 pagesICC Moot Court Competition International Rounds Finalists Defence Memorial PDFArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- 09 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument15 pages09 - Chapter 1 PDFArshdeep Singh ChahalNo ratings yet

- Barbara I. Morey, Etc. v. United States, 903 F.2d 880, 1st Cir. (1990)Document5 pagesBarbara I. Morey, Etc. v. United States, 903 F.2d 880, 1st Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Article - The UK Constitution - Nicola McEwen (BBC NEWS)Document3 pagesArticle - The UK Constitution - Nicola McEwen (BBC NEWS)PepedNo ratings yet

- Research On Variance DoctrineDocument2 pagesResearch On Variance DoctrineMarianne SerranoNo ratings yet

- Trial of Raja Nand Kumar (1775) : A Judicial MurderDocument6 pagesTrial of Raja Nand Kumar (1775) : A Judicial MurderNupur KatiyarNo ratings yet

- Krissia Rosibel Paz-Avalos, A200 123 950 (BIA Dec. 6, 2012)Document6 pagesKrissia Rosibel Paz-Avalos, A200 123 950 (BIA Dec. 6, 2012)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- 7 Motor Insurers' Bureau of Singapore and Another V Am Ge (1) - Pages-DeletedDocument42 pages7 Motor Insurers' Bureau of Singapore and Another V Am Ge (1) - Pages-DeletedFarah Najeehah ZolkalpliNo ratings yet

- 47) Republic vs. Estate of Menzi G.R. No. 152578 November 23, 2005 PCGG FactsDocument1 page47) Republic vs. Estate of Menzi G.R. No. 152578 November 23, 2005 PCGG FactsYRNo ratings yet

- Gios-Samar, Inc., Represented by Its Chairperson Gerardo M. Malinao, Petitioner, vs. Department of Transportation and Communications and Civil Aviation Authority of The Philippines, Respondents.Document17 pagesGios-Samar, Inc., Represented by Its Chairperson Gerardo M. Malinao, Petitioner, vs. Department of Transportation and Communications and Civil Aviation Authority of The Philippines, Respondents.melody dayagNo ratings yet

- 65-66 Dacillo and Garces CaseDocument4 pages65-66 Dacillo and Garces CaseAisha TejadaNo ratings yet

- BBIssue 40Document84 pagesBBIssue 40MaryNo ratings yet

- Extenuating Circumstances CcmaDocument2 pagesExtenuating Circumstances CcmaapriliaguydocsNo ratings yet

- Tanega v. Masakayan - Full TextDocument2 pagesTanega v. Masakayan - Full TextjiggerNo ratings yet

- Ronquillo Vs CADocument6 pagesRonquillo Vs CAabethzkyyyyNo ratings yet

- DefencesDocument25 pagesDefencesSamantha RnNo ratings yet

- Oblicon 1Document12 pagesOblicon 1Jojo GaiteNo ratings yet

- The Shop and Office Employees ActDocument3 pagesThe Shop and Office Employees ActRajanRanjanNo ratings yet

- Jones V Dirty World Entertainment Personal Jurisdiction RulingDocument17 pagesJones V Dirty World Entertainment Personal Jurisdiction RulingEric GoldmanNo ratings yet

- Criminal Background Check FormDocument1 pageCriminal Background Check FormVirginia MCNo ratings yet

- Kinds of JusticeDocument25 pagesKinds of JusticemurkyNo ratings yet

- 10-11-15 Koller, Cynthia. and Koller, Elizabeth, Splintered Justice: Is Judicial Corruption Breaking The Bench? American Society of Criminology Journal (2010)Document1 page10-11-15 Koller, Cynthia. and Koller, Elizabeth, Splintered Justice: Is Judicial Corruption Breaking The Bench? American Society of Criminology Journal (2010)Human Rights Alert - NGO (RA)No ratings yet

- Nutrimix Feeds Corp. V. Court of Appeals 441 SCRA 357 (2004)Document3 pagesNutrimix Feeds Corp. V. Court of Appeals 441 SCRA 357 (2004)Rando TorregosaNo ratings yet

- Associated Bank Vs Spouses PronstrollerDocument3 pagesAssociated Bank Vs Spouses PronstrollerJudy Ann ShengNo ratings yet

- Aspects of Due ProcessDocument11 pagesAspects of Due ProcessDarkSlumberNo ratings yet

- ZIA V WAPDADocument3 pagesZIA V WAPDAMary Joyce Lacambra AquinoNo ratings yet

- Bacsin Vs WahimanDocument5 pagesBacsin Vs WahimanRavenFoxNo ratings yet

- Interlates Limited Et Al v. Kemira Chemicals Inc. Et Al - Document No. 32Document3 pagesInterlates Limited Et Al v. Kemira Chemicals Inc. Et Al - Document No. 32Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Young Gentleman and Lady'S 1Document260 pagesYoung Gentleman and Lady'S 1Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Artemio Iniego V. The Honorable Judge Guillermo G. Purganan, and Fokker C. Santos G. R. No. 166876 March 24, 2006Document2 pagesArtemio Iniego V. The Honorable Judge Guillermo G. Purganan, and Fokker C. Santos G. R. No. 166876 March 24, 2006ninaNo ratings yet

- Francisco Vs CA NEGODocument3 pagesFrancisco Vs CA NEGOMary LouiseNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 9 Discipleship Through Discernment and VirtuesDocument21 pagesCHAPTER 9 Discipleship Through Discernment and VirtuesRonna Mae Dungog100% (1)