Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Story So Far: Fresh Hurdles Have Emerged in The Road To Peace in

The Story So Far: Fresh Hurdles Have Emerged in The Road To Peace in

Uploaded by

Mahesh Jha0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views3 pagesThe main rebel group NSCN (I-M) is upset with Nagaland Governor R.N. Ravi for allegedly tweaking the original 2015 framework agreement between the group and the Indian government. Ravi has rejected the NSCN (I-M)'s demands to be removed as interlocutor for the peace process. Additional hurdles include the NSCN (I-M)'s insistence on "Naga independence" and idea of a Greater Nagalim homeland that encompasses parts of neighboring states, which those states strongly oppose due to concerns over territorial integrity. The peace process also faces challenges reconciling the positions of the NSCN (I-M) and other rival Naga groups involved

Original Description:

Original Title

NAGA PEACE PROCESS

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThe main rebel group NSCN (I-M) is upset with Nagaland Governor R.N. Ravi for allegedly tweaking the original 2015 framework agreement between the group and the Indian government. Ravi has rejected the NSCN (I-M)'s demands to be removed as interlocutor for the peace process. Additional hurdles include the NSCN (I-M)'s insistence on "Naga independence" and idea of a Greater Nagalim homeland that encompasses parts of neighboring states, which those states strongly oppose due to concerns over territorial integrity. The peace process also faces challenges reconciling the positions of the NSCN (I-M) and other rival Naga groups involved

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

26 views3 pagesThe Story So Far: Fresh Hurdles Have Emerged in The Road To Peace in

The Story So Far: Fresh Hurdles Have Emerged in The Road To Peace in

Uploaded by

Mahesh JhaThe main rebel group NSCN (I-M) is upset with Nagaland Governor R.N. Ravi for allegedly tweaking the original 2015 framework agreement between the group and the Indian government. Ravi has rejected the NSCN (I-M)'s demands to be removed as interlocutor for the peace process. Additional hurdles include the NSCN (I-M)'s insistence on "Naga independence" and idea of a Greater Nagalim homeland that encompasses parts of neighboring states, which those states strongly oppose due to concerns over territorial integrity. The peace process also faces challenges reconciling the positions of the NSCN (I-M) and other rival Naga groups involved

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 3

Why is the main rebel outfit upset?

What is the government

interlocutor’s stand on the ‘framework agreement’?

The story so far: Fresh hurdles have emerged in the road to peace in

Nagaland. After a framework agreement was signed in 2015 between

the Centre and the Isak-Muivah faction of the National Socialist Council

of Nagalim, or the NSCN (I-M), the largest of the extremist groups in the

peace process since 1997, there have been more than 100 rounds of talks

and several twists and turns. The latest involves the demand by the NSCN

(I-M) to remove Nagaland Governor R.N. Ravi as the Centre’s

interlocutor for the 23-year-old peace process and his alleged tweaking of

the original framework agreement.

What has made the peace process wobble?

Talks, fatigue and growing impatience across the Naga domain gave way

to optimism when Mr. Ravi was made Nagaland’s Governor in July

2019. His appointment was seen as a message from New Delhi that the

solution would be found soon. As the Centre’s interlocutor, Mr. Ravi had

signed the framework agreement in the presence of Prime Minister

Narendra Modi. But in October 2019, he issued a statement blaming the

“procrastinating attitude” of the NSCN (I-M) for the delay in a

mutually-agreed draft comprehensive settlement. He also said the NSCN

(I-M) imputed “imaginary contents” to the framework agreement while

referring to the government’s purported acceptance of a ‘Naga national

flag’ and ‘Naga Yezhabo (constitution)’ as part of the deal. In June 2020,

the NSCN (I-M) took offence to Mr. Ravi’s letter to Nagaland Chief

Minister Neiphiu Rio in which he referred to them as “armed gangs”

running parallel governments. The NSCN (I-M) reacted by demanding Mr.

Ravi’s removal from the peace process but the Naga National Political

Groups (NNPGs), a conglomerate of seven rival groups, and some social

organisations want him to stay.

What is the ‘framework agreement’?

On August 3, 2015, the Centre signed a framework agreement with the

NSCN (I-M) to resolve the Naga issue, but both sides maintained secrecy

about its contents. The optimism among some Naga groups eroded a bit

when the NNPGs were brought on board the peace process on November

17, 2017. This agreement ostensibly made the peace process inclusive but

it created suspicion about Delhi exploiting divisions within the Nagas on

tribal and geopolitical lines. It was also a throwback to the first peace deal,

the Shillong Accord of 1975 that Naga hardliners rejected. That had led to

the birth of the NSCN in January 1980. Differences surfaced within the

outfit a few years later over initiating a dialogue process with the Indian

government. It split into the NSCN (I-M) and NSCN (Khaplang) in April

1988 who often engaged in fratricidal battles.

Why is the ‘agreement’ in the news?

A few days ago, the NSCN (I-M) released the contents of the

framework agreement. The outfit said Mr. Ravi had “craftily deleted the

word ‘new’ from the original” line that referred to “shared sovereignty”

between India and the Naga homeland and provided for an “enduring

inclusive new relationship of peaceful co-existence”. The NSCN (I-M)

claimed “new” was a politically sensitive word that defined the meaning of

peaceful co-existence of the two entities (sovereign powers) and strongly

indicated a settlement outside the purview of the Constitution of India. The

group said it had refrained from publishing the contents of the framework

agreement respecting the “tacit understanding reached between the two

sides not to release to the public domain for security reasons”. But, it

claimed, Mr. Ravi took undue advantage and started manipulating the

framework agreement to mislead the Nagas and the Centre. The Governor

said the framework agreement was an “acceptance of the Indian

Constitution” by the outfit.

What are the other hurdles?

In his ‘Naga Independence Day’ speech on August 14, NSCN (I-M)

general secretary Thuingaleng Muivah insisted the Nagas “will never

merge with India”. But States adjoining Nagaland, where the peace

headquarters of NSCN (I-M) is located, are apprehensive of the

sovereignty issue. This is because of the NSCN (I-M)’s idea of Greater

Nagalim — a homeland encompassing all Naga-inhabited areas in

Nagaland and beyond. Apart from Myanmar, where many of more than 50

Naga tribes live, the Greater Nagalim map includes large swathes of

Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Manipur. The Assam government

has vowed not to part with “even an inch of land”, the All Arunachal

Pradesh Students’ Union warned against any “territorial

changes” while finding a solution. Manipur Chief Minister Nongthombam

Biren Singh said he has received the Centre’s assurance that the peace deal

with the NSCN (I-M) will not affect the territorial integrity of

Manipur. But non-Naga groups are suspicious since the Tangkhul

community, forming the core of the NSCN (I-M), is from Manipur and the

outfit may not accept any agreement that excludes areas inhabited by

them. The NNPGs, whose members are primarily from Nagaland, are also

a factor; their inputs for a final solution could be at variance with those of

the NSCN (I-M).

You might also like

- 1026 Form32 PDFDocument3 pages1026 Form32 PDFAnonymous T2VKMaeONo ratings yet

- American Legislative Exchange Council - Federal Government and Corrupt Practices (Updated)Document77 pagesAmerican Legislative Exchange Council - Federal Government and Corrupt Practices (Updated)Robert SloanNo ratings yet

- The History of Naga National MovementDocument5 pagesThe History of Naga National MovementKev Atu SLimes MaresNo ratings yet

- My Ndudas DasdDocument2 pagesMy Ndudas Dasdkkaafow5xrNo ratings yet

- TTP Ends CeasefireDocument9 pagesTTP Ends CeasefireIrtaza HassanNo ratings yet

- Bangsamoro Is A Proposed New Autonomous Political Entity Within The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesBangsamoro Is A Proposed New Autonomous Political Entity Within The PhilippinesilovelawschoolNo ratings yet

- Nagaland's InsurgencyDocument9 pagesNagaland's InsurgencyChandra BhushanNo ratings yet

- Peace Info February 14 2018Document46 pagesPeace Info February 14 2018kyaw thuNo ratings yet

- Naga Issue UPSCDocument6 pagesNaga Issue UPSCNabam Tazap HinaNo ratings yet

- Wheeler Talking and Killing in Southern Thailand 2013Document3 pagesWheeler Talking and Killing in Southern Thailand 2013Bebeny IrawanNo ratings yet

- India Pakistan Relations A Framework ForDocument15 pagesIndia Pakistan Relations A Framework Forsu7075592No ratings yet

- Strengthening India-China RelationsDocument15 pagesStrengthening India-China RelationsRitam TalukdarNo ratings yet

- Placing The Naga Conflict in Present: by Arjoma MoulickDocument7 pagesPlacing The Naga Conflict in Present: by Arjoma MoulickSarvani MoulikNo ratings yet

- Research Paper: University of SargodhaDocument9 pagesResearch Paper: University of SargodhaBilal ArshadNo ratings yet

- 201438761Document56 pages201438761The Myanmar TimesNo ratings yet

- Bodo Accord and Insurgency in AssamDocument6 pagesBodo Accord and Insurgency in AssamAnKit ShaRmaNo ratings yet

- Bangsamoro Is A Proposed New Autonomous Political Entity Within TheDocument7 pagesBangsamoro Is A Proposed New Autonomous Political Entity Within TheilovelawschoolNo ratings yet

- Stamnes de Coning - The Revitalised Agreement On The Resolution of The Conflict in The Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) - FAIR Case Brief, 6Document9 pagesStamnes de Coning - The Revitalised Agreement On The Resolution of The Conflict in The Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS) - FAIR Case Brief, 6jonnybilek2112No ratings yet

- PM No. 24 - 08-09-11Document5 pagesPM No. 24 - 08-09-11taisamyoneNo ratings yet

- Singh and FriendsDocument2 pagesSingh and FriendsakurilNo ratings yet

- Afghan Peace TalksDocument3 pagesAfghan Peace TalksUsama ChaudhryNo ratings yet

- Foriegn Policy of PakistanDocument11 pagesForiegn Policy of PakistanSYEDMUSTAFA QAZINo ratings yet

- The Helsinki AgreementDocument120 pagesThe Helsinki AgreementVanny SihombingNo ratings yet

- Relations Between India and Pakistan Have Been Complex and LargelyDocument2 pagesRelations Between India and Pakistan Have Been Complex and Largelyعرباض لطیفNo ratings yet

- UNFC Press Release - 11 Feb 2015 (ENG)Document1 pageUNFC Press Release - 11 Feb 2015 (ENG)United Nationalities Federal CouncilNo ratings yet

- One Year Afghan PeaceDocument5 pagesOne Year Afghan PeaceAhsan AliNo ratings yet

- Allied in War, Divided in PeaceDocument6 pagesAllied in War, Divided in PeaceThaw Thi KhoNo ratings yet

- Peace Info March 25 2019Document86 pagesPeace Info March 25 2019linn22847No ratings yet

- Pacifism To Confrontation: Conflict Dynamics Between The Nuclear Contenders (India-Pakistan)Document14 pagesPacifism To Confrontation: Conflict Dynamics Between The Nuclear Contenders (India-Pakistan)syed shoaibNo ratings yet

- HE AGA Onflict: M Amarjeet SinghDocument52 pagesHE AGA Onflict: M Amarjeet SinghKev Atu SLimes MaresNo ratings yet

- Dureza: New Bangsamoro Government Unit To Kick of Federalism ShiftDocument2 pagesDureza: New Bangsamoro Government Unit To Kick of Federalism ShiftrlinaoNo ratings yet

- Daily News On February 01 2012-Burm-EnglshDocument20 pagesDaily News On February 01 2012-Burm-EnglshPugh JuttaNo ratings yet

- From Generation To Generation: Advancing Cross-Strait RelationsDocument23 pagesFrom Generation To Generation: Advancing Cross-Strait RelationskuimbaeNo ratings yet

- India China ArticalDocument7 pagesIndia China Articalamit447No ratings yet

- Policy Report: Gujarat, Rajasthan and Punjab: The Need For A Border States GroupDocument40 pagesPolicy Report: Gujarat, Rajasthan and Punjab: The Need For A Border States GroupAmritpal BhagatNo ratings yet

- India - China Relations India-China Political RelationsDocument8 pagesIndia - China Relations India-China Political RelationsDeb DasNo ratings yet

- Confidence-Building Between India and Pakistan: Lessons, Opportunities, and ImperativesDocument22 pagesConfidence-Building Between India and Pakistan: Lessons, Opportunities, and ImperativesSayandNo ratings yet

- The Gandhi - Jinnah Talks - Umer RazzakDocument13 pagesThe Gandhi - Jinnah Talks - Umer RazzakUmer RazzakNo ratings yet

- US-Taliban Peace' Deal: Despite Being A Key Stakeholder, India Has Painted Itself Into A Corner of IrrelevanceDocument3 pagesUS-Taliban Peace' Deal: Despite Being A Key Stakeholder, India Has Painted Itself Into A Corner of IrrelevanceMaheen IdreesNo ratings yet

- Government Peace Treaty With Muslim FilipinosDocument23 pagesGovernment Peace Treaty With Muslim FilipinosBiNo ratings yet

- Joint Statement On The Humanitarian Consequences of Nuclear WeaponsDocument10 pagesJoint Statement On The Humanitarian Consequences of Nuclear Weaponsapi-295118124No ratings yet

- Litreature Review (Dissertation)Document10 pagesLitreature Review (Dissertation)Sungit ImsongNo ratings yet

- Powell Secures Pledge To Finish Comprehensive Sudanese Peace AccordDocument2 pagesPowell Secures Pledge To Finish Comprehensive Sudanese Peace Accordapi-3702364No ratings yet

- Report of The Secretary-General On Children and Armed Conflict in The Philippines (1 December 2012 - 31 December 2016)Document17 pagesReport of The Secretary-General On Children and Armed Conflict in The Philippines (1 December 2012 - 31 December 2016)Roh MihNo ratings yet

- Peace in AchehDocument25 pagesPeace in AchehSyafrizal Ramli YusufNo ratings yet

- 2023 12 30current - PDFDocument15 pages2023 12 30current - PDFNabajyoti DaimariNo ratings yet

- Myanmar - A New Peace Initiative (REPORT)Document38 pagesMyanmar - A New Peace Initiative (REPORT)Phop HtawNo ratings yet

- Afghan Peace Process and The Role of TurkeyDocument5 pagesAfghan Peace Process and The Role of TurkeyInstitute of Policy StudiesNo ratings yet

- Saarc: Ziaur RahmanDocument26 pagesSaarc: Ziaur RahmanAsif ShaikhNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument1 pageNew Microsoft Office Word Documentshaik allauddinNo ratings yet

- PST - Phase LVDocument4 pagesPST - Phase LVDanish TahirNo ratings yet

- Manageable Aggression': Facebook CountDocument3 pagesManageable Aggression': Facebook CountFarooq KhanNo ratings yet

- SAARC and TerrorismDocument115 pagesSAARC and TerrorismshomaniizNo ratings yet

- Unity Government of Malaysia On Wisdom of His Majesty The KingDocument7 pagesUnity Government of Malaysia On Wisdom of His Majesty The Kingplsse 2022No ratings yet

- Intra Afghan Talks - June - 17 - 2020Document5 pagesIntra Afghan Talks - June - 17 - 2020Jatoi AkhtarNo ratings yet

- IB Amina June 17 2020 PDFDocument5 pagesIB Amina June 17 2020 PDFRaees RiazNo ratings yet

- Address On Post Conflict Sri Lank ADocument9 pagesAddress On Post Conflict Sri Lank AdickwaughNo ratings yet

- PresentationDocument4 pagesPresentationNadeem SheikhNo ratings yet

- Peace Deal Between Hekmatyar and AfghanistanDocument5 pagesPeace Deal Between Hekmatyar and AfghanistanInstitute of Policy Studies0% (1)

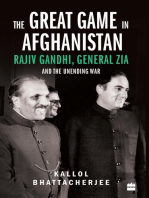

- The Great Game in Afghanistan: Rajiv Gandhi, General Zia and the Unending WarFrom EverandThe Great Game in Afghanistan: Rajiv Gandhi, General Zia and the Unending WarRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Kuknalim, Naga Armed Resistance: Testimonies of Leaders, Pastors, Healers and SoldiersFrom EverandKuknalim, Naga Armed Resistance: Testimonies of Leaders, Pastors, Healers and SoldiersNo ratings yet

- NIP2Document1 pageNIP2Mahesh JhaNo ratings yet

- GS-I: Indian Heritage and Culture, History and Geography of The World and SocietyDocument1 pageGS-I: Indian Heritage and Culture, History and Geography of The World and SocietyMahesh JhaNo ratings yet

- India-China Conflict: Why in NewsDocument7 pagesIndia-China Conflict: Why in NewsMahesh JhaNo ratings yet

- REDD ADocument5 pagesREDD AMahesh JhaNo ratings yet

- Forwarding Report: PEDRO PENDEJO, 47 Years Old, Resident of Putik, Zamboanga CityDocument6 pagesForwarding Report: PEDRO PENDEJO, 47 Years Old, Resident of Putik, Zamboanga CityArvi April NarzabalNo ratings yet

- Akayesu - Rape Definition Only International LawDocument2 pagesAkayesu - Rape Definition Only International LawMaria Guila Renee BaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Veluz v. CADocument4 pagesVeluz v. CARostum AgapitoNo ratings yet

- HRF Letter To Nicki MinajDocument2 pagesHRF Letter To Nicki MinajlizNo ratings yet

- Letterhead: Securities and Exchange CommissionDocument2 pagesLetterhead: Securities and Exchange CommissionGlory Perez100% (1)

- Adult Career Crises and TransitionDocument30 pagesAdult Career Crises and TransitionAlexandra AlasNo ratings yet

- Department of Health V PharmawealthDocument3 pagesDepartment of Health V PharmawealthJohn Basil ManuelNo ratings yet

- Airbus Helicopters: Coloring Book Fun & GamesDocument12 pagesAirbus Helicopters: Coloring Book Fun & GamesLuis RomeroNo ratings yet

- Remman Enterprises vs. PRBRES and PRCDocument5 pagesRemman Enterprises vs. PRBRES and PRCJuris DoctorNo ratings yet

- Mikesell v. Chater, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (1997)Document6 pagesMikesell v. Chater, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Kevin Durant MarketingDocument7 pagesKevin Durant Marketingapi-641785948No ratings yet

- Most Important One Liner Questions and Answers March 2023Document13 pagesMost Important One Liner Questions and Answers March 2023PC MNo ratings yet

- B.A. (H) History-3rd Semester-2017Document24 pagesB.A. (H) History-3rd Semester-2017NILESH KUMARNo ratings yet

- Democracy Is The Best Form of GovernmentDocument2 pagesDemocracy Is The Best Form of GovernmentAmit SinghNo ratings yet

- Israel Public LawDocument6 pagesIsrael Public LawTAU Law ReviewNo ratings yet

- Blue Is The Warmest Colour Computer ... - Curzon CinemasDocument84 pagesBlue Is The Warmest Colour Computer ... - Curzon Cinemasjackjhonk036No ratings yet

- Twisted TeachersDocument158 pagesTwisted TeachersIve HadditNo ratings yet

- Form GST REG-06: Government of IndiaDocument3 pagesForm GST REG-06: Government of IndiaGunjit JunejaNo ratings yet

- VDA. de Lopez vs. LopezDocument2 pagesVDA. de Lopez vs. LopezNeptaly P. ArnaizNo ratings yet

- 26 - Order For Default JudgmentDocument13 pages26 - Order For Default JudgmentCynthia Stine100% (2)

- 21 Edillon V Manila Bankers Life Insurance CorporationDocument2 pages21 Edillon V Manila Bankers Life Insurance CorporationVia Monina ValdepeñasNo ratings yet

- All Saint's Day MassDocument4 pagesAll Saint's Day MassJJ MagallonNo ratings yet

- Mugshot Ban Leg Memo 2019.03.27 (FINAL)Document3 pagesMugshot Ban Leg Memo 2019.03.27 (FINAL)Rachel SilbersteinNo ratings yet

- Tales of The Alhambra ExamDocument4 pagesTales of The Alhambra ExamEmily RiveiroNo ratings yet

- Verbal ReviewerDocument6 pagesVerbal ReviewerKing ina Mo100% (1)

- 2.incorporation of Company and Matters Incidental TheretoDocument58 pages2.incorporation of Company and Matters Incidental TheretoKarthikNo ratings yet

- AMLA PP vs. Estrada 2009Document6 pagesAMLA PP vs. Estrada 2009Honey Mambuay-Barambangan0% (1)

- Affidavit of DesistanceDocument1 pageAffidavit of DesistanceCaoili MarceloNo ratings yet