Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 viewsTRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Di Erent From The Versions

TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Di Erent From The Versions

Uploaded by

Bob BoberuThis document summarizes the historic Korean board game of Sunjang Go, which was last played in 1937 before disappearing. Some key aspects of Sunjang Go included starting positions with 17 fixed stones, a counting method where all stones must be played and territories counted rather than prisoners, and possible local variations in rules. An example game recording is provided to illustrate the Sunjang Go counting method.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Go The Board GameDocument192 pagesGo The Board GameJosé Fidel Valladolid100% (1)

- ShogiDocument5 pagesShogiannca7No ratings yet

- Chess Middlegame Strategies Vol 2 - Ivan Sokolov (2018)Document261 pagesChess Middlegame Strategies Vol 2 - Ivan Sokolov (2018)BG86% (7)

- Elementary Go Series Vol 1 - in The BeginningDocument157 pagesElementary Go Series Vol 1 - in The Beginninganon-27190094% (16)

- How to Play Go: A Beginners to Expert Guide to Learn The Game of Go: An Instructional Book to Learning the Rules, Go Board, and Art of The GameFrom EverandHow to Play Go: A Beginners to Expert Guide to Learn The Game of Go: An Instructional Book to Learning the Rules, Go Board, and Art of The GameRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- How to Play Chess for Children: A Beginner's Guide for Kids To Learn the Chess Pieces, Board, Rules, & StrategyFrom EverandHow to Play Chess for Children: A Beginner's Guide for Kids To Learn the Chess Pieces, Board, Rules, & StrategyRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Istoric Unjang O: TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Different From TheDocument4 pagesIstoric Unjang O: TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Different From TheBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- RenjuforbeginnersDocument30 pagesRenjuforbeginnersIurie GusanNo ratings yet

- Andrew Grant's Go History PagesDocument35 pagesAndrew Grant's Go History PagesTikz KrubNo ratings yet

- Shogi The Chess of JapanDocument50 pagesShogi The Chess of JapanSun-J AkolkarNo ratings yet

- Discover THE GAME OF GO!: Publicity For The Talk), or Books Like Shibumi by Trevanian, TV ShowsDocument23 pagesDiscover THE GAME OF GO!: Publicity For The Talk), or Books Like Shibumi by Trevanian, TV ShowsJoeNo ratings yet

- The Game of Go (Illustrated): The National Game of JapanFrom EverandThe Game of Go (Illustrated): The National Game of JapanNo ratings yet

- Chinese Chess: An Introduction to China's Ancient Game of StrategyFrom EverandChinese Chess: An Introduction to China's Ancient Game of StrategyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (14)

- Classics LuZhanQi 0 2 1 enDocument16 pagesClassics LuZhanQi 0 2 1 endonzhangNo ratings yet

- (Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) Go Wins Review-2003 FallDocument12 pages(Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) Go Wins Review-2003 FallcremeaucafeNo ratings yet

- RyazanDocument4 pagesRyazanRyazan AlesterNo ratings yet

- ShowdownDocument6 pagesShowdownfulon.jeremyNo ratings yet

- Games According To ClassificationDocument9 pagesGames According To ClassificationClarice LizardoNo ratings yet

- Gentle Joseki - Pieter Mioch PDFDocument146 pagesGentle Joseki - Pieter Mioch PDFvalgorunescu@hotmail.comNo ratings yet

- How to Play Mah Jongg: A Beginner's Guide to American Mah Jongg: An Instruction Book to Learning the Rules, Sets, and Art of The GameFrom EverandHow to Play Mah Jongg: A Beginner's Guide to American Mah Jongg: An Instruction Book to Learning the Rules, Sets, and Art of The GameRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (2)

- Ajedrez 123Document152 pagesAjedrez 123trane99100% (1)

- Shogi RuleDocument18 pagesShogi RuleTất Thành VũNo ratings yet

- About This Booklet How To Print:: Do Not Print Page 1 (These Instructions)Document3 pagesAbout This Booklet How To Print:: Do Not Print Page 1 (These Instructions)FabricioFernandezNo ratings yet

- Go Seigen BookDocument539 pagesGo Seigen BooknawwanNo ratings yet

- Go On Go - PsDocument481 pagesGo On Go - Psjyaanb100% (1)

- SaltaDocument2 pagesSaltaWkrscribdNo ratings yet

- SenetDocument2 pagesSenetWkrscribdNo ratings yet

- 2004CCC PDFDocument16 pages2004CCC PDFBinh AnNo ratings yet

- (Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) Go On Go - Analized Games of Go SeigenDocument539 pages(Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) Go On Go - Analized Games of Go Seigenjuan100% (2)

- Play Go GameDocument20 pagesPlay Go GameKARTHIK145100% (2)

- 1 11 Ancient Game NoteDocument6 pages1 11 Ancient Game Noteapi-277283360No ratings yet

- Go - Introduction in GO Game - BookletDocument20 pagesGo - Introduction in GO Game - BookletGabrielNo ratings yet

- Rules TrifoldDocument2 pagesRules TrifoldsaffwanNo ratings yet

- Ancient Board Games 1 The Royal Game ofDocument62 pagesAncient Board Games 1 The Royal Game ofLuiz CarlosNo ratings yet

- Ancient Board GamesDocument120 pagesAncient Board Gamesagueres100% (5)

- Welcome To Ancient Games From Around The WorldDocument37 pagesWelcome To Ancient Games From Around The WorldDragosnicNo ratings yet

- The Red Dragon & the West Wind: The Winning Guide to Official Chinese & American Mah-JonggFrom EverandThe Red Dragon & the West Wind: The Winning Guide to Official Chinese & American Mah-JonggNo ratings yet

- Polo The King of GamesDocument2 pagesPolo The King of GamesSheikh Gulzar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Variant Chess Newsletter 06 PDFDocument16 pagesVariant Chess Newsletter 06 PDFRobert McCordNo ratings yet

- Go - Wikipedia BookDocument197 pagesGo - Wikipedia BookNeovanNo ratings yet

- PE Board GamesDocument4 pagesPE Board GamesJadus Marcus50% (2)

- How To Play Chess: A Beginner's Guide to Learning the Chess Game, Pieces, Board, Rules, & StrategiesFrom EverandHow To Play Chess: A Beginner's Guide to Learning the Chess Game, Pieces, Board, Rules, & StrategiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- CaturDocument14 pagesCaturEdward ThomasNo ratings yet

- Pung Chow The Game of a Hundred Intelligences. Also known as Mah-Diao, Mah-Jong, Mah-Cheuk, Mah-Juck and Pe-LingFrom EverandPung Chow The Game of a Hundred Intelligences. Also known as Mah-Diao, Mah-Jong, Mah-Cheuk, Mah-Juck and Pe-LingNo ratings yet

- Chess: How To Play Chess For Beginners: Learn How to Win at Chess - Master Chess Tactics, Chess Openings and Chess Strategies!From EverandChess: How To Play Chess For Beginners: Learn How to Win at Chess - Master Chess Tactics, Chess Openings and Chess Strategies!Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Sample File: BL Ood HunterDocument6 pagesSample File: BL Ood HunterBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Origin of Go in KoreaDocument1 pageOrigin of Go in KoreaBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Adventures Dark and Deep: Sample FileDocument9 pagesAdventures Dark and Deep: Sample FileBob Boberu100% (1)

- Name Stan The Kobold: Normal StatblockDocument2 pagesName Stan The Kobold: Normal StatblockBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Character SketchDocument1 pageCharacter SketchBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Introducing John Fairbairn 3 April 2000: Made Available On This SiteDocument1 pageIntroducing John Fairbairn 3 April 2000: Made Available On This SiteBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument6 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Introducing John Fairbairn 3 April 2000: Be Made Available On This SiteDocument1 pageIntroducing John Fairbairn 3 April 2000: Be Made Available On This SiteBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Istoric Unjang O: TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Different From TheDocument4 pagesIstoric Unjang O: TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Different From TheBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Zhou Donghou vs. Huang LongshiDocument16 pagesZhou Donghou vs. Huang LongshiBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- 111111go PDFDocument1 page111111go PDFBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Mouse Guard RPG - Realm Guard v1.4 PDFDocument43 pagesMouse Guard RPG - Realm Guard v1.4 PDFBob Boberu100% (2)

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument4 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument2 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument3 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument5 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument6 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- 1995-08-31 PDFDocument4 pages1995-08-31 PDFBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument4 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument5 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A Provisional C0da PDFDocument60 pagesA Provisional C0da PDFBob Boberu100% (1)

- Miskatonic University: Orne LibraryDocument1 pageMiskatonic University: Orne LibraryBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Dungeon VaultDocument2 pagesDungeon VaultBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A Khajiit C0da Full CycleDocument68 pagesA Khajiit C0da Full CycleBob Boberu100% (1)

- WaniaDocument6 pagesWaniaherky napiNo ratings yet

- Historical Dictionary of American Cinema - Keith Booker PDFDocument509 pagesHistorical Dictionary of American Cinema - Keith Booker PDFAndreea Josefin100% (1)

- Declaration of John Branca at Robson CaseDocument7 pagesDeclaration of John Branca at Robson CaseIvy100% (2)

- Sri Muthuswamy DeekshitarDocument172 pagesSri Muthuswamy Deekshitarrburra236492% (13)

- FisheriesDocument49 pagesFisheriesrajarajan092208No ratings yet

- Msi GT62VR-6RD MS-16L21 0a PDFDocument43 pagesMsi GT62VR-6RD MS-16L21 0a PDFEverAguiarNo ratings yet

- WOIN - OLD - Fantasy Careers (v1.1)Document59 pagesWOIN - OLD - Fantasy Careers (v1.1)Rich MNo ratings yet

- Emily in Paris Fashion Analysis FinalDocument9 pagesEmily in Paris Fashion Analysis FinalCHELSEALYANo ratings yet

- Tonga Tong 3Document2 pagesTonga Tong 3Ej RafaelNo ratings yet

- Esl Exam c2 01Document8 pagesEsl Exam c2 01Claudia Sedano IbañezNo ratings yet

- Soal Ulangan Harian BSI Kls 10Document6 pagesSoal Ulangan Harian BSI Kls 10Intan MimyNo ratings yet

- Future of FreelancingDocument6 pagesFuture of FreelancingNishtha AgarwaalNo ratings yet

- Creation - The World Building GameDocument17 pagesCreation - The World Building Gamecameronhyndman100% (1)

- (339.book) Download Program Arcade Games: With Python and Pygame PDFDocument2 pages(339.book) Download Program Arcade Games: With Python and Pygame PDFGiani BuzatuNo ratings yet

- Denmark CuisineDocument35 pagesDenmark CuisineThefoodiesway100% (2)

- A Level Kate Bush Hounds Set Work Support GuideDocument10 pagesA Level Kate Bush Hounds Set Work Support GuideAmir Sanjary ComposerNo ratings yet

- Sonion Introduction To Electret Microphones An Rev005Document16 pagesSonion Introduction To Electret Microphones An Rev005aragon1974No ratings yet

- Snaptube 2Document15 pagesSnaptube 2PatriciaHidalgoHernandezNo ratings yet

- Nessco Hidratron Helium BoosterDocument1 pageNessco Hidratron Helium BoosterdbrunomingoNo ratings yet

- The Great Hall of The Bishops PalaceDocument9 pagesThe Great Hall of The Bishops PalaceMokhtar MorghanyNo ratings yet

- A Tale of Brotherly LoveDocument8 pagesA Tale of Brotherly Loveizmcnorton0% (1)

- Arkham Horror Card Game, Taboo ListDocument1 pageArkham Horror Card Game, Taboo ListPanos SalteasNo ratings yet

- Perpetual Calendar 1901-2099Document2 pagesPerpetual Calendar 1901-2099danielsasikumarNo ratings yet

- KUL KCH: Muhammad Danish / Bin Muhamad Zazilah MRDocument1 pageKUL KCH: Muhammad Danish / Bin Muhamad Zazilah MRdanishzazilah99No ratings yet

- Orbit RolDocument32 pagesOrbit RolThanh CongNo ratings yet

- Gateway Credit CardDocument1 pageGateway Credit CardRafael KrappNo ratings yet

- Retail Store LayoutDocument24 pagesRetail Store Layoutsheebakbs5144No ratings yet

- tripadvisor ru 21 01 11 21 05 result 11916 База от белорусовDocument1,390 pagestripadvisor ru 21 01 11 21 05 result 11916 База от белорусовАнна ПилюгаNo ratings yet

- Big Mamas FuneralDocument9 pagesBig Mamas Funeralsiddarthmahajan15No ratings yet

- Treasuer IslandDocument7 pagesTreasuer Islandapi-283549718No ratings yet

TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Di Erent From The Versions

TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Di Erent From The Versions

Uploaded by

Bob Boberu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views4 pagesThis document summarizes the historic Korean board game of Sunjang Go, which was last played in 1937 before disappearing. Some key aspects of Sunjang Go included starting positions with 17 fixed stones, a counting method where all stones must be played and territories counted rather than prisoners, and possible local variations in rules. An example game recording is provided to illustrate the Sunjang Go counting method.

Original Description:

Original Title

(03-23-2000) Historic Sunjang Go.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document summarizes the historic Korean board game of Sunjang Go, which was last played in 1937 before disappearing. Some key aspects of Sunjang Go included starting positions with 17 fixed stones, a counting method where all stones must be played and territories counted rather than prisoners, and possible local variations in rules. An example game recording is provided to illustrate the Sunjang Go counting method.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views4 pagesTRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Di Erent From The Versions

TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Di Erent From The Versions

Uploaded by

Bob BoberuThis document summarizes the historic Korean board game of Sunjang Go, which was last played in 1937 before disappearing. Some key aspects of Sunjang Go included starting positions with 17 fixed stones, a counting method where all stones must be played and territories counted rather than prisoners, and possible local variations in rules. An example game recording is provided to illustrate the Sunjang Go counting method.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 4

H:S G

ISTORIC UNJANG O

23 March 2000

The freshly added commentary on the last game of Sunjang Go from 1937 can be found here.

TRADITIONAL go in Korea was rather di erent from the versions

played in China or Japan. It dates from the late 16th century, but its

roots may be the version closest to the original form of go. It appears to

have died out only this century. The last known game before it

disappeared was played in 1937. Its recent rediscovery is due to the go

writer Yi Seung-u (Lee Sungwoo), but there has also been intensive

work done on both the rules and history of old Korea go by the

professional Kweon Kyeong-eon 5-dan, and by An Lyeong-i, former

editor of the monthly go magazine Baduk and of modern Korean

versions of the go classics.

Old Korean go is called sun-chang pa-tuk (sunjang baduk).

Sunjang is written in two completely di erent ways when written in

characters, indicating a basic uncertainty about the meaning, but the

commonest way of writing it nowadays - touring o cers - o ers two

possibilities. One is that it refers to a military rank and may refer to

guards who moved from post to post (or are posted round the board).

The other is that the 17 "star" points for the starting stones were called

"guard points" (the usual term is ower points), and sunjang refers to

going round the board placing these stones at the start. The other way

of writing is even more obscure but could be rendered "following one's

seniors." There seems to be some connection with an administrative

system introduced at the time, which relied on ranks.

As the above may indicate, the game was played on a specially

marked traditional board, of which several examples survive. The 17

starting-stone points are marked. It appears that both players placed

eight stones each on the points shown in the game below, and Black

then played rst. But as he was obliged to play his rst move on the

centre point, we can e ectively regard this as a starting stone too.

These stones have no special powers, unlike their equivalents in

Tibetan go. There is a ritualistic order in which they are placed but this

has no bearing on the game.

The basic rules are the same as in modern Japanese go, which no

doubt encouraged players to abandon the old form. For most of the

doubt encouraged players to abandon the old form. For most of the

rst half of this century Korea was a Japanese colony and the status

and strength of visiting Japanese players presumably encouraged

Koreans to play the Japanese way. This trend was accelerated when

senior players such as Cho Nam-ch'eol - the father of modern Korean

go - established even closer links with Japan by studying there.

The real di erence in sunjang go, apart from the starting

position, is in the counting rules. Ko and seki are treated exactly as in

Japan (no points are counted in a seki). There was traditionally no

komi, so clearly Black had a big advantage - yet another factor

favouring adoption of Japanese rules. But at the time the last known

game was recorded, the players were already playing each other in

newspaper games using Japanese rules, and borrowed the idea of komi.

The game here was perhaps even then something of an exhibition

game, but it is valuable that it was played by strong players. The top 10

players at the time ranged from about 4 dan amateur to 2 dan

professional in modern terms.

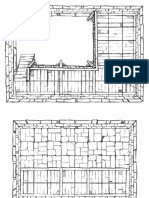

The method of counting requires that the game continues until

all necessary dame have been lled in. As in Chinese go, dame (neutral

points) is a misnomer because they can contribute to the score.

Prisoners are ignored. Once the nal position is reached, all dead

stones are rst removed (and ignored) and then all stones not forming

part of the outside walls are removed. The idea is to achieve the

minimum outside wall - cutting points can be left at this stage but no

stone must be left in atari. The respective total territories (vacant

points surrounded) are then counted and compared. The winner is the

one with the highest total (after komi adjustment, if any), but it seems

that there were in some areas extra provisions such that a tie was a

win for White and a 1-point win for Black counted as a tie. Judging by

the variant rules still extant in Korean chess we can expect some such

local variations in sunjang go.

As an example of old Korean counting, take the following 9x9

position once all moves have been played.

1. Game as actually nished

2. Dead stones are rst removed

3. Then super uous internal stones are removed

Handicap play is also possible. Black occupies points on the

seventh line but not the centre point, while White occupies the centre

point.

The game here is the one known as the "last game." However,

there have been exhibition games since then involving players as

strong as Cho Nam'ch'eol. Typical rst moves in their games have been

K8 and K6. Games invariably become a test of nerve - though excellent

training for life and death and capturing races - and that may be

connected with the fact that until recent times go in Korea was largely

a gambling game.

Note: McCune-Reischauer transliteration without sound changes

(i.e. hyphenated) is used as a basic reference standard, especially in

names (the circum ex being shown as a leading e as in Seoul). More

traditional spellings or sound changes may also be used for

convenience.

You might also like

- Go The Board GameDocument192 pagesGo The Board GameJosé Fidel Valladolid100% (1)

- ShogiDocument5 pagesShogiannca7No ratings yet

- Chess Middlegame Strategies Vol 2 - Ivan Sokolov (2018)Document261 pagesChess Middlegame Strategies Vol 2 - Ivan Sokolov (2018)BG86% (7)

- Elementary Go Series Vol 1 - in The BeginningDocument157 pagesElementary Go Series Vol 1 - in The Beginninganon-27190094% (16)

- How to Play Go: A Beginners to Expert Guide to Learn The Game of Go: An Instructional Book to Learning the Rules, Go Board, and Art of The GameFrom EverandHow to Play Go: A Beginners to Expert Guide to Learn The Game of Go: An Instructional Book to Learning the Rules, Go Board, and Art of The GameRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- How to Play Chess for Children: A Beginner's Guide for Kids To Learn the Chess Pieces, Board, Rules, & StrategyFrom EverandHow to Play Chess for Children: A Beginner's Guide for Kids To Learn the Chess Pieces, Board, Rules, & StrategyRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Istoric Unjang O: TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Different From TheDocument4 pagesIstoric Unjang O: TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Different From TheBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- RenjuforbeginnersDocument30 pagesRenjuforbeginnersIurie GusanNo ratings yet

- Andrew Grant's Go History PagesDocument35 pagesAndrew Grant's Go History PagesTikz KrubNo ratings yet

- Shogi The Chess of JapanDocument50 pagesShogi The Chess of JapanSun-J AkolkarNo ratings yet

- Discover THE GAME OF GO!: Publicity For The Talk), or Books Like Shibumi by Trevanian, TV ShowsDocument23 pagesDiscover THE GAME OF GO!: Publicity For The Talk), or Books Like Shibumi by Trevanian, TV ShowsJoeNo ratings yet

- The Game of Go (Illustrated): The National Game of JapanFrom EverandThe Game of Go (Illustrated): The National Game of JapanNo ratings yet

- Chinese Chess: An Introduction to China's Ancient Game of StrategyFrom EverandChinese Chess: An Introduction to China's Ancient Game of StrategyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (14)

- Classics LuZhanQi 0 2 1 enDocument16 pagesClassics LuZhanQi 0 2 1 endonzhangNo ratings yet

- (Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) Go Wins Review-2003 FallDocument12 pages(Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) Go Wins Review-2003 FallcremeaucafeNo ratings yet

- RyazanDocument4 pagesRyazanRyazan AlesterNo ratings yet

- ShowdownDocument6 pagesShowdownfulon.jeremyNo ratings yet

- Games According To ClassificationDocument9 pagesGames According To ClassificationClarice LizardoNo ratings yet

- Gentle Joseki - Pieter Mioch PDFDocument146 pagesGentle Joseki - Pieter Mioch PDFvalgorunescu@hotmail.comNo ratings yet

- How to Play Mah Jongg: A Beginner's Guide to American Mah Jongg: An Instruction Book to Learning the Rules, Sets, and Art of The GameFrom EverandHow to Play Mah Jongg: A Beginner's Guide to American Mah Jongg: An Instruction Book to Learning the Rules, Sets, and Art of The GameRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (2)

- Ajedrez 123Document152 pagesAjedrez 123trane99100% (1)

- Shogi RuleDocument18 pagesShogi RuleTất Thành VũNo ratings yet

- About This Booklet How To Print:: Do Not Print Page 1 (These Instructions)Document3 pagesAbout This Booklet How To Print:: Do Not Print Page 1 (These Instructions)FabricioFernandezNo ratings yet

- Go Seigen BookDocument539 pagesGo Seigen BooknawwanNo ratings yet

- Go On Go - PsDocument481 pagesGo On Go - Psjyaanb100% (1)

- SaltaDocument2 pagesSaltaWkrscribdNo ratings yet

- SenetDocument2 pagesSenetWkrscribdNo ratings yet

- 2004CCC PDFDocument16 pages2004CCC PDFBinh AnNo ratings yet

- (Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) Go On Go - Analized Games of Go SeigenDocument539 pages(Go Igo Baduk Weiqi) (Eng) Go On Go - Analized Games of Go Seigenjuan100% (2)

- Play Go GameDocument20 pagesPlay Go GameKARTHIK145100% (2)

- 1 11 Ancient Game NoteDocument6 pages1 11 Ancient Game Noteapi-277283360No ratings yet

- Go - Introduction in GO Game - BookletDocument20 pagesGo - Introduction in GO Game - BookletGabrielNo ratings yet

- Rules TrifoldDocument2 pagesRules TrifoldsaffwanNo ratings yet

- Ancient Board Games 1 The Royal Game ofDocument62 pagesAncient Board Games 1 The Royal Game ofLuiz CarlosNo ratings yet

- Ancient Board GamesDocument120 pagesAncient Board Gamesagueres100% (5)

- Welcome To Ancient Games From Around The WorldDocument37 pagesWelcome To Ancient Games From Around The WorldDragosnicNo ratings yet

- The Red Dragon & the West Wind: The Winning Guide to Official Chinese & American Mah-JonggFrom EverandThe Red Dragon & the West Wind: The Winning Guide to Official Chinese & American Mah-JonggNo ratings yet

- Polo The King of GamesDocument2 pagesPolo The King of GamesSheikh Gulzar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Variant Chess Newsletter 06 PDFDocument16 pagesVariant Chess Newsletter 06 PDFRobert McCordNo ratings yet

- Go - Wikipedia BookDocument197 pagesGo - Wikipedia BookNeovanNo ratings yet

- PE Board GamesDocument4 pagesPE Board GamesJadus Marcus50% (2)

- How To Play Chess: A Beginner's Guide to Learning the Chess Game, Pieces, Board, Rules, & StrategiesFrom EverandHow To Play Chess: A Beginner's Guide to Learning the Chess Game, Pieces, Board, Rules, & StrategiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- CaturDocument14 pagesCaturEdward ThomasNo ratings yet

- Pung Chow The Game of a Hundred Intelligences. Also known as Mah-Diao, Mah-Jong, Mah-Cheuk, Mah-Juck and Pe-LingFrom EverandPung Chow The Game of a Hundred Intelligences. Also known as Mah-Diao, Mah-Jong, Mah-Cheuk, Mah-Juck and Pe-LingNo ratings yet

- Chess: How To Play Chess For Beginners: Learn How to Win at Chess - Master Chess Tactics, Chess Openings and Chess Strategies!From EverandChess: How To Play Chess For Beginners: Learn How to Win at Chess - Master Chess Tactics, Chess Openings and Chess Strategies!Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Sample File: BL Ood HunterDocument6 pagesSample File: BL Ood HunterBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Origin of Go in KoreaDocument1 pageOrigin of Go in KoreaBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Adventures Dark and Deep: Sample FileDocument9 pagesAdventures Dark and Deep: Sample FileBob Boberu100% (1)

- Name Stan The Kobold: Normal StatblockDocument2 pagesName Stan The Kobold: Normal StatblockBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Character SketchDocument1 pageCharacter SketchBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Introducing John Fairbairn 3 April 2000: Made Available On This SiteDocument1 pageIntroducing John Fairbairn 3 April 2000: Made Available On This SiteBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument6 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Introducing John Fairbairn 3 April 2000: Be Made Available On This SiteDocument1 pageIntroducing John Fairbairn 3 April 2000: Be Made Available On This SiteBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Istoric Unjang O: TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Different From TheDocument4 pagesIstoric Unjang O: TRADITIONAL Go in Korea Was Rather Different From TheBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Zhou Donghou vs. Huang LongshiDocument16 pagesZhou Donghou vs. Huang LongshiBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- 111111go PDFDocument1 page111111go PDFBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Mouse Guard RPG - Realm Guard v1.4 PDFDocument43 pagesMouse Guard RPG - Realm Guard v1.4 PDFBob Boberu100% (2)

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument4 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument2 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument3 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument5 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument6 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- 1995-08-31 PDFDocument4 pages1995-08-31 PDFBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument4 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TDocument5 pagesA B C D e F G H J K L M N o P Q R S TBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A Provisional C0da PDFDocument60 pagesA Provisional C0da PDFBob Boberu100% (1)

- Miskatonic University: Orne LibraryDocument1 pageMiskatonic University: Orne LibraryBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- Dungeon VaultDocument2 pagesDungeon VaultBob BoberuNo ratings yet

- A Khajiit C0da Full CycleDocument68 pagesA Khajiit C0da Full CycleBob Boberu100% (1)

- WaniaDocument6 pagesWaniaherky napiNo ratings yet

- Historical Dictionary of American Cinema - Keith Booker PDFDocument509 pagesHistorical Dictionary of American Cinema - Keith Booker PDFAndreea Josefin100% (1)

- Declaration of John Branca at Robson CaseDocument7 pagesDeclaration of John Branca at Robson CaseIvy100% (2)

- Sri Muthuswamy DeekshitarDocument172 pagesSri Muthuswamy Deekshitarrburra236492% (13)

- FisheriesDocument49 pagesFisheriesrajarajan092208No ratings yet

- Msi GT62VR-6RD MS-16L21 0a PDFDocument43 pagesMsi GT62VR-6RD MS-16L21 0a PDFEverAguiarNo ratings yet

- WOIN - OLD - Fantasy Careers (v1.1)Document59 pagesWOIN - OLD - Fantasy Careers (v1.1)Rich MNo ratings yet

- Emily in Paris Fashion Analysis FinalDocument9 pagesEmily in Paris Fashion Analysis FinalCHELSEALYANo ratings yet

- Tonga Tong 3Document2 pagesTonga Tong 3Ej RafaelNo ratings yet

- Esl Exam c2 01Document8 pagesEsl Exam c2 01Claudia Sedano IbañezNo ratings yet

- Soal Ulangan Harian BSI Kls 10Document6 pagesSoal Ulangan Harian BSI Kls 10Intan MimyNo ratings yet

- Future of FreelancingDocument6 pagesFuture of FreelancingNishtha AgarwaalNo ratings yet

- Creation - The World Building GameDocument17 pagesCreation - The World Building Gamecameronhyndman100% (1)

- (339.book) Download Program Arcade Games: With Python and Pygame PDFDocument2 pages(339.book) Download Program Arcade Games: With Python and Pygame PDFGiani BuzatuNo ratings yet

- Denmark CuisineDocument35 pagesDenmark CuisineThefoodiesway100% (2)

- A Level Kate Bush Hounds Set Work Support GuideDocument10 pagesA Level Kate Bush Hounds Set Work Support GuideAmir Sanjary ComposerNo ratings yet

- Sonion Introduction To Electret Microphones An Rev005Document16 pagesSonion Introduction To Electret Microphones An Rev005aragon1974No ratings yet

- Snaptube 2Document15 pagesSnaptube 2PatriciaHidalgoHernandezNo ratings yet

- Nessco Hidratron Helium BoosterDocument1 pageNessco Hidratron Helium BoosterdbrunomingoNo ratings yet

- The Great Hall of The Bishops PalaceDocument9 pagesThe Great Hall of The Bishops PalaceMokhtar MorghanyNo ratings yet

- A Tale of Brotherly LoveDocument8 pagesA Tale of Brotherly Loveizmcnorton0% (1)

- Arkham Horror Card Game, Taboo ListDocument1 pageArkham Horror Card Game, Taboo ListPanos SalteasNo ratings yet

- Perpetual Calendar 1901-2099Document2 pagesPerpetual Calendar 1901-2099danielsasikumarNo ratings yet

- KUL KCH: Muhammad Danish / Bin Muhamad Zazilah MRDocument1 pageKUL KCH: Muhammad Danish / Bin Muhamad Zazilah MRdanishzazilah99No ratings yet

- Orbit RolDocument32 pagesOrbit RolThanh CongNo ratings yet

- Gateway Credit CardDocument1 pageGateway Credit CardRafael KrappNo ratings yet

- Retail Store LayoutDocument24 pagesRetail Store Layoutsheebakbs5144No ratings yet

- tripadvisor ru 21 01 11 21 05 result 11916 База от белорусовDocument1,390 pagestripadvisor ru 21 01 11 21 05 result 11916 База от белорусовАнна ПилюгаNo ratings yet

- Big Mamas FuneralDocument9 pagesBig Mamas Funeralsiddarthmahajan15No ratings yet

- Treasuer IslandDocument7 pagesTreasuer Islandapi-283549718No ratings yet