Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Student Storytelling Yhrough Sequential Art PDF

Student Storytelling Yhrough Sequential Art PDF

Uploaded by

Nidia PedrazaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Student Storytelling Yhrough Sequential Art PDF

Student Storytelling Yhrough Sequential Art PDF

Uploaded by

Nidia PedrazaCopyright:

Available Formats

David Fay

U Z B E K I S T A N

Student Storytelling through

Sequential Art

M

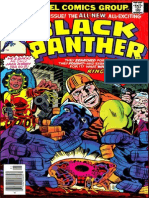

ost all of us are familiar Despite its popularity, sequential

with one form or another art has long been misunderstood.

of sequential art, a term After widespread use throughout the

that the late illustrator Will Eisner first half of the 20th century, comic

(1985, 5) coined for an art form that books in the United States came

has come to include cartoons, comic

under attack in the 1950s when psy-

strips, comic books, and graphic nov-

chiatrist Frederic Wertham wrote, in

els. It is an international art form.

his highly influential Seduction of the

Most French people can recall a scene

Innocent, that they are a “reinforcing

from Tintin or Asterix; most Turks are

familiar with the adventures of Red factor in children’s reading disorders”

Kit; it is hard to find a South Ameri- (1954, 130). Their meatier sibling,

can who does not adore Mafalda or is the graphic novel, has long been

not an avid follower of the sharp wit associated with the seedier end of the

and social commentary in Quino’s vast content spectrum sequential art

cartoons; the Indian sub-continent covers and has only recently been rec-

has access to Chacha Chavdhary in ognized as a serious literary medium.

10 languages; and Finns can actu- Max Collins’ Road to Perdition, which

ally pronounce the name of one of was later turned into a Hollywood

their comic book heroes, Kapteeni blockbuster, Jeff Smith’s Bone series,

Hyperventilanttorimies. The Japanese

and Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer prize-

have their own version of the art

winning Maus all play important

form, manga, which now covers sev-

roles in casting a more positive light

eral racks in most bookstores across

on graphic novels.

the United States. These books can

be found next to the rows of bound In the United States comic books

anthologies of American classics such are, unfortunately, still regarded by

as Spiderman, Archie, and the Fantas- many parents and educators as aca-

tic Four, collections that go back over demically detrimental, despite the

three generations. fact that a growing body of research

2 2007 N U M B E R 3 | E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 2 6/27/07 9:48:04 AM

has shown otherwise. Research by Hayes and a film in English. While some authors of fic-

Ahrens (1988) highlights the fact that comic tion successfully approximate the nature of

books contain a greater number of rare words human speech, their works do not contain

than ordinary conversation and are thus an the visual support that sequential art offers,

excellent stepping stone to more difficult nor are they generally as accessible, in terms

reading. Dorrell and Carroll (1981) and Ujiie of language level, as sequential art. And while

and Krashen (1996a, 1996b) found that film is another important source of this less

the increased use of comic books stimulates formal variety of spoken English, it requires

the reading of non-comics material. Krashen technology that many classrooms around the

(2004) points out that anyone still willing world lack. Films also lack the visual perma-

to associate juvenile delinquency with comic nence of the written page that allows students

book reading should consider the example of to read and re-read target expressions in comic

South Africa’s Bishop Desmond Tutu, who books as often as they like.

praises the role comic books played in his Sequential art also provides an up-to-date

childhood. look at target language culture and soci-

ety. As an art form that is kept current by

Why use sequential art in the EFL class? active publishing houses, newspapers, and

The reasons sequential art is such a popu- the Internet, it is a widely accessible source

lar commercial art form—visual appeal, ver- of popular topics, concerns, and fashions

satility, efficiency and power of message—also that can interest almost any age level. And as

justify its use in the modern foreign language most comics involve a number of characters

classroom. Students are attracted by the rich from different backgrounds interacting over

interplay of graphics and text and by the qual- a long period of time, they can serve as a

ity of the story, a distinguishing feature of tool for studying socio-cultural aspects of a

authentic sources of language. Unlike many people, allowing a teacher to design a lesson

EFL resources, the plot is not sacrificed for based solely on cross-cultural differences and

the benefit of a graded approach to language. similarities between the target language cul-

The higher quality of the story, coupled with ture and the students’ native culture. Due to

the ability of the reader to connect visually the taboo status of the art form in the 1950s

with the cartoon characters, means that stu- in the United States, many comics have a

dents invest in the comics intellectually and healthy dose of “other-ness” that often takes

emotionally (Cary 2004). Its lower readability the shape of cynicism and irony. This makes

level (Wright and Shermann 1999) and the comic books a rich source of alternative

support of graphics also ensure learners can points of view within the target culture and

access the authentic language with less trouble can, as such, provide a perspective that will

than they have with most other authentic help fuel discussion and debate (Chilcoat and

sources. Ligon 1994).

Cary (2004, 33) points out that sequen- The enthusiasm for using sequential art

tial art is rich in ellipses, blends, non-words in the language classroom has spurred the

(uh-huh, humph, sheesh!), and other common publication of many articles and ideas. Cary’s

aspects of spoken language, exposing students outstanding teacher’s resource book, Going

to “the ambiguity, vagueness and downright Graphic, contains probably the most complete

sloppiness of spoken English” (Williams 1995, treatment of the subject to date. There are also

25). Sequential art is a window on the spoken several good articles that specifically address

vernacular, a variety of the target language the use of comics in the EFL classroom.

that is commonly overlooked in EFL classes Among the better articles are Noemi Csabay’s

in large part due to its absence in both educa- (2006) “Using comic strips in language class-

tional material and in more formal authentic es” and Neil Williams’ (1995) “The Comic

texts. The obvious absence of an informal Book as Course Book: Why and How.” In this

register from a students’ linguistic repertoire article I will look at student-created sequential

is a key contributing factor to misunderstand- art, a topic that only a handful of authors have

ing and confusion when students confront a discussed, albeit usually with reference to the

native speaker of English or when they watch native speaker class.

E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M | NUMBER 3 2007 3

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 3 6/27/07 9:48:05 AM

One of the biggest advantages to having awareness of specific social concerns through

students create their own sequential art is that storytelling. By addressing a topic with real-

they take ownership of the learning process, life implications, students learn more about

with the added benefit that the product of their community, city, or country and are

their effort can become a permanent part of inspired to explore solutions that can lead to

the classroom. This helps solve one of the meaningful follow-on activities. By fictional-

more serious problems in EFL today: a lack izing the topic, students are able to use their

of materials. Good comic books can be kept imaginations to explore a multitude of pos-

for future classes and, due to their widespread sible scenarios rather than simply report on

appeal, can be used with different age and the facts. With their invented characters, they

language levels in a school. A project initi- can approach the topic through the eyes of

ated by a Peace Corps Volunteer in Uzbeki- another, adding a rich variety of perspectives

stan resulted in bound, printed copies of on the topic. The coupling of text and graph-

student-generated stories that were based on ics packs a punch. Be prepared to have fun.

popular folk tales and fables. They are now in And be prepared to enjoy, and to have other

their fourth year of use. During the creative classes enjoy, the power of the students’ mes-

process, students practiced research skills, sages and stories.

developed their literacy and critical thinking Step 1: Exploring sequential art

skills, and mastered the structure of storytell-

ing. As students work collaboratively on such Begin by familiarizing students with the art

projects, they also negotiate language among form by bringing in samples that cover a range

themselves and with the teacher, adding to of styles, content, and functions (news stories,

each other’s language knowledge as the project advertisements, instruction booklets, comic

progresses. books, etc.). Material in the students’ native

Students can cover a wide array of top- language can be used for this part of the pro-

ics through this art form. Sequential art can cess, but keep in mind that the Internet is also

revisit or summarize stories that the students an excellent source of English language mate-

have read in class or for homework, thus rials. (See the “Websites of Interest” listed at

serving as a comprehension check or as an the end of the article.) Students should begin

assessment tool. Sequential art can be used exploring the overall layout and approach to

to increase student interest in a subject, sequential art, the balance of visual and text,

as Bryan, Chilcoat and Morrison (2002) and the use of speech bubbles or dialogue

accomplished with a social studies unit on balloons (characters’ speech), thought clouds

the native Arctic coastal Inuit way of life. In (characters’ thoughts) and captions (text at

his “Take a stand” activity, Cary (2004, 100) the top or bottom of a panel). Some of the

argues for introducing the editorial cartoon, key questions that students should discuss are

emphasizing a Freirian model of reflection as follows.

and social action. Another author, Mulhol- 1. What is the story about? If an adver-

land (2004), emphasizes the healing power tisement, what is the message? If a

of comics and argues that one should use user’s manual, what does it explain?

“the creation of comic book characters and 2. What role do the graphics (drawings)

worlds to work through problems in [one’s] play? Do they add to the story, mes-

life” (42). Autobiographies or biographies of sage, or explanation? How so? Can

family members, descriptions of cultural cel- you understand the story without the

ebrations, how-to instructions for a favorite graphics? (The teacher can provide a

hobby, even complex grammar explanations handout, use the board or do a dicta-

are all potential subject matters for this elastic tion to have the students focus on all

art form. or part of the graphics-free text.)

3. What is the role of the text? Can you

Creating sequential art in the EFL class understand the story or message with-

Below is a step-by-step approach to help out the text? (The teacher can provide

teachers get their students started with this a handout with the text covered or

art form. This approach focuses on raising whited-out.)

4 2007 NUMBER 3 | E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 4 6/27/07 9:48:06 AM

4. What kinds of characters are used? Are groups. While not essential, work groups

they realistic? Do they represent some- are probably the best way to work with an

thing? If so, what? art form that involves a considerable level of

5. Do the characters speak in full sen- artistic talent, storytelling expertise, and plan-

tences? Why or why not? What kinds ning. Some students will obviously be better

of new words and expressions do you visual artists than others, while others will be

see? better at finding just the right language for a

6. In what order are the panels (the basic specific character. A project of this size has a

unit of sequential art, the “picture greater chance of succeeding if it taps into an

frame” of the art form) read? In what array of talents. A collaborative approach also

order are the speech bubbles read? Prac- ensures that issues are discussed among group

tice mapping the movement of your members as the story is being developed, thus

eye through the page. After comparing enhancing the language learning experience

with another student, what are the on and off the page.

similarities and differences in the way The world of commercial comics has

you read the panels? clear-cut job titles: researcher, writer, pen-

ciler, inker, colorist, letterer, and editor. This

Teachers should introduce the following

breakdown of responsibilities does not read-

questions specifically for stories.

ily fit the goals of an EFL class, which is to

1. How many panels does the artist use to involve all members in the research, writing,

tell the story? and editing phases of the project. The jobs

2. What are the basic parts of the story of “penciling,” or sketching the images in a

(setting the scene, introducing char- panel, “inking,” or outlining the sketches with

acters, developing the plot, climax, ink, “coloring,” or adding color to the draw-

other)? How many panels are used for ing, and “lettering,” or writing words into the

each part? speech bubbles, thought clouds, and captions,

3. Are there any panels the artist could can be distributed among the group. As one

have inserted? Which ones and where? might guess, the job of penciler is the one

Why do you think they were left out? that requires the most artistic skill and talent.

(Why did the artist choose the specific While a group might have a standout artist,

panels on the page?) it is still a good idea to involve other students

4. What different perspectives does the in this time-consuming phase. We will have

artist use (eye-level view, close-up, a look in Step 7 at alternative approaches to

bird’s-eye view, etc.)? How does the dealing with the artwork.

perspective add to the emotion or A group of three or four students works

energy of the scene? best. It maximizes the potential to include

5. Was the story good? If you had been group members in almost all aspects of the

the author, what would you have done work yet does not burden the students with

differently? too much work, as might happen when work-

Many students are probably familiar with ing in pairs. It is also helpful if the students

sequential art, but they may not have looked know that their effort and their project will be

at it with a critical eye. The idea of this first assessed, both on a group and individual basis.

step is to get students to look more closely Progress checks and frequent informal consul-

at the art form and to explore its power and tations with the teacher will help, although a

secrets as future creators. While there are right student-created “group contract” works even

and wrong answers for some of the questions better. This is an agreement made by the stu-

above, answers will vary according to the dents in the group that describes who will do

samples of sequential art the teacher shares what parts of the project. The teacher gives an

with the class. overview of the tasks and the students decide

on how best to share the responsibilities. The

Step 2: Establishing project groups agreement can be re-negotiated as the project

If the project is to be a collaborative effort, progresses, and it can be handed in to the

this is the best stage during which to form teacher, with progress check notes, at the end

E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M | NUMBER 3 2007 5

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 5 6/27/07 9:48:06 AM

of the project. Whatever shape or form the not enter the university despite a relatively

assessment mechanism takes, the goal is to high score on a national entrance exam, for

motivate the students to be supportive of one example, is better material for a story than a

another so that they collaborate on all phases table with statistics. And the fact that a group

of the project. of after-school mates has to interrupt their

Step 3: Choosing a topic street game of soccer every time a car goes by

will add tenfold to better grasping the issue

Some schools have an integrated curricu- of neighborhoods lacking play-space. If this

lum that concurrently addresses themes across stage of the project is managed correctly, the

a range of subject areas. This means that at result will be a thesis statement with a few

some stage during the school year the math, colorful examples.

literature, and social science teachers all cover

the theme of, to choose a few examples, the Step 4: Researching the topic

environment, health, or space exploration. It is important to set specific deadlines for

The EFL teacher has the advantage of tap- each of the next four steps as they could easily

ping into an established subject area to find a go on for days, if not weeks. This is not nec-

theme or topic for the sequential art project. essarily a bad thing, especially if students are

If the EFL program is self-contained or an busy learning and using the target language.

independent institution altogether, research- But teachers and students alike generally

ing issues that touch upon the students’ lives appreciate a time line for the project. As a

should be part of the syllabus-building phase rough frame of reference, a class that meets

anyway. To find new themes for this particular three hours a week can work through the

project, newspaper articles, conversations in entire project in about four weeks, assum-

the cafeteria, public announcements, and, ing some of the work can be assigned as

most importantly, the students themselves are homework. The research phase should last

good places to start. about one week, with students beginning by

While it is not necessarily a good idea to debating among themselves some of the more

have all groups tackle the same topic, there fundamental questions at play:

are advantages to having different groups

1. What are the key problems? What are

deal with the same theme through different

the causes?

stories. The theme of bettering one’s country’s

2. What are the various points of view on

educational system, for example, can rally the

the issue? Who is behind each of these

entire class to identify different issues and to

opinions?

explore solutions from a variety of angles.

3. What are some of the ways in which

This will add to the depth and breadth of

the key problems can be solved?

knowledge about a theme for the entire class,

4. Have any of the solutions been

especially when the final products are shared.

attempted? Why or why not? Are there

It also fuels a shop-and-share approach as the

any negative consequences to these

projects are progressing, encouraging students

solutions?

to discover ways in which the variations on a

5. Who stands to benefit most from each

common theme are inter-related.

solution? Who benefits from not hav-

To ensure ownership of the project, stu-

ing the issue addressed at all?

dent groups should be tasked with specifying

their topic, within a given theme, and put- Armed with some possible answers, and

ting it into a local context. Whether it’s the hopefully with even more questions, the stu-

absence of after-school recreational space in dents should decide among themselves who

a neighborhood, the lack of textbooks and will investigate what. One possible division

other resources in school, or the shortage of of labor is to have specific students be respon-

universities for a country’s high school gradu- sible for obtaining information from neigh-

ates, there is an abundance of topics on any bors, government offices, businesses, and so

given theme. The more specific and local on. All group member should tap into more

the topic, the easier it will be to deal with, widely available sources of information, such

especially with younger students. Firsthand as newspapers, books in the community or

knowledge of a brother or cousin who could school library, if one exists, and the Internet.

6 2007 NUMBER 3 | E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 6 6/27/07 9:48:06 AM

A viable approach to the research is to have Familiarity with fiction and the ability to

students investigate a group of questions relat- think creatively are usually all the students

ed to one specific aspect of their topic. With need. A good group brainstorm, together with

the topic of a resource-strained school, for some input from the teacher, if even necessary,

example, one student can research historical might help the group come up with the idea

changes in the availability of resources while of some friends unwittingly going on a fish-

another looks at future plans. A third group ing trip to the Aral Sea. Or the story could be

member can investigate the teachers’ current about a family member who has been away in

needs. Some degree of overlap is natural and Russia for many years and decides to return to

should be perceived as a way of strengthening her hometown, a village that used to be near

the story. the shore of the Aral Sea. Students should

Step 5: Developing the story be thinking about the various problems that

could present themselves and about how the

At the risk of oversimplifying the struc- characters will react to each of these problems.

ture of a story, and with reckless disregard There could be bad weather, health issues, or a

for culture-sensitive genres and the work of disingenuous bus driver. These hurdles should

many best-selling authors, there are three basic help shed light on the main social concern.

parts to most stories: a beginning, middle, They should also give the characters reasons

and an end. Sequential art is no different. to interact and talk, simultaneously breathing

The beginning sets the scene, familiarizes the life into the story and the characters. In short,

reader with the characters, and introduces the the group members’ imaginations should be

problem, issue, or concern. The middle is usu- allowed to wander while keeping in mind an

ally a series of episodes or adventures, often overall message.

presented as hurdles or difficulties that need Sequential art lends itself to stereotypes

to be overcome. These episodes add detail and allows students with basic drawing skills

and substance to the story and flesh out the to build a personality with a few symbols rath-

characters’ ideas and personalities. The ending er than through a detailed drawing. A pair of

is the climax, where the problem is resolved, glasses can represent someone who has stud-

for good or for bad. To certain kinds of stories ied long and hard. A large belly can represent

we can also add a moral or coda to the ending. a character with a more relaxed approach to

This helps place the problem in a larger con- life. And in Central Asia, a man with a white

text and gives the reader food for thought. beard can represent truth and wisdom. In his

Fictionalizing a topic of social concern is superb book Making Comics, Scott McCloud

no easy task. But it can be made easier by (2006) recommends basing characters on cer-

localizing the events, using familiar characters, tain well-known formulas: the stereotypes of

and allowing the students’ imaginations to the classic hero with superhuman powers and

explore a variety of scenarios. Once the topic the villain with a penchant for dark magic;

is chosen—let’s take the environment—and Jung’s four types of human thought—intu-

localized—the Aral Sea, for those of us living ition, feeling, intellect, and sensation; the

in Central Asia––the group needs to find a four elements of earth, air, fire and water;

storyline, or plot. As background for the story, astrological signs; the four seasons; historical

student research should have already gener- figures; and favorite animals. To these I would

ated the following general information: add the personalities of famous people in the

The Aral Sea…is a landlocked sea in students’ native culture and the group mem-

Central Asia. Since the 1960s the Aral bers’ own personalities.

Sea has been shrinking, as the rivers With a strong story and characters, an

that feed it were diverted by the Soviet ending should emerge with considerable ease.

Union for irrigation. The Aral Sea is Surprises add to the appeal of a story but are

heavily polluted, largely as the result not essential. Subtle twists often work just as

of weapons testing, industrial projects, well. The fishing buddies might pull out THE

and fertilizer runoff before and after last fish of the sea (appropriately labeled in

the break-up of the Soviet Union. the panel) and the girl who has returned to

(Wikipedia 2007) her village, now miles from a sea that once

E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M | NUMBER 3 2007 7

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 7 6/27/07 9:48:06 AM

provided a livelihood for all, might find com- recommends introducing students to the fol-

fort or a fighting spirit in wise words from lowing structure for each panel:

her grandmother, one of the few remaining Scene/Panel 1, 2, 3 and so on...

villagers. Narrative: (general description of the

Step 6: Structuring the story panel)

The group now needs to fit the story into Dialogue:

panels and write an accompanying script and Character 1:

captions. For teachers and students just begin- Character 2:

ning to work with this art form, I recommend Caption:

three A4 pages doubled over to create a 12- Scene: (visual description of scene)

page booklet. This makes a front and back This brief description of each panel will

cover with 10 pages in-between. Each page allow students to adjust or re-write parts of

(half of the A4 sheet of paper), can be divided the story before the artwork begins. It is also

into four equal quarters, each of which will a good place to conduct a round of peer edit-

become a panel. I recommend adding a space ing. Feedback from a number of readers will

between each panel—known as the “gutter”— help the group determine whether they need

as that adds to the visual appeal of the book to re-think any aspect of the story or the posi-

and allows for one to fit in larger amounts of tion and choice of any of the panels. This is

text in the form of speech bubbles, thought also the time and place for the teacher to give

clouds, and captions. Be sure to leave a larger feedback on the language used in the dialogue

outer margin for the binding. This is usually and caption. If the booklets are to remain

just a few staples down the folded middle and in a classroom library for other students to

should be the last step in the book-making read, it is worth having the students work on

process. polishing certain aspects of the language and

The front cover includes the title, authors, on inserting expressions that are appropriate

and a catchy visual. This is often an enlarge- to the level of the students. The idea is not

ment of one of the more attractive panels to correct every single mistake or reshape the

in the story, so it can be decided upon after text to the teacher’s liking, but to turn the lan-

most of the artwork is finished. The back guage into a slightly more refined form so that

cover should contain a short summary of the it becomes a learning tool for the group and

story that piques the readers’ attention but for future readers at that language level.

avoids giving away the ending. It does not

Step 7: Adding the artwork

need to have artwork on it, but it will be more

appealing if it does. A picture that offers only Often one group member excels at draw-

the scenery from one part of the story works ing, or “penciling.” This is a positive cir-

best. Again, this could be an enlargement of cumstance and is one of the reasons groups

one of the panels, with text in the place of the are formed in the first place. However, all

characters. students need to be included in the artwork

Page 1, the inside front cover, is known as phase of the project. One way of doing this

a “splash” page and is usually one large panel is to have the artistically challenged students

that introduces the characters and establishes “pencil” easier objects, add detail to characters

the setting. A caption often helps provide and objects, or work from images or models

some background information about the provided by the group’s artist. Less demand-

story. If one sticks to four panels per booklet- ing alternatives include tracing over the pen-

page, pages 2 to 9 should have a total of 36 ciled sketches with ink, “inking” in the world

panels. They will contain the plot and climax. of sequential art, or coloring in the sketches,

To cut down on the total number of panels, unless you opt for a simple black and white

and to add visual variety, consider having approach. All students can “letter” the speech

students experiment with one wider or longer bubbles, thought clouds, and captions.

panel by bringing two panels together. To gain To help cut down on the need to start all

a sense of how the story will fit into the pan- over again, make sure students do not begin

els, all students should draft a panel-by-panel “inking” a page until speech bubbles, thought

map, or outline, of the story. Chilcoat (1993) clouds, and captions have been “penciled” in.

8 2007 NUMBER 3 | E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 8 6/27/07 9:48:07 AM

This stage is also the best time at which to pagination and speech bubble order. How-

conduct a second round of peer editing that ever, the English text, for obvious reasons, is

focuses on the artwork of the story. Groups read left to right.) Despite any native language

should share their sketches with one another reading and writing conventions, students

and be encouraged to comment on the clarity should adopt the English language conven-

and effectiveness of the drawings, the visual tion of reading left to right in pagination,

representation of the characters, the connec- speech bubble order and, actual text. Once

tion between speech and character, the choice they have perfected the art form, students

of the panels to tell the story and convey a may want to try being more adventurous. For

message, and the visual cohesiveness of the example, some students with whom I worked

overall story. created a reader’s-choice approach to plot

Once students have critiqued the drawings sequence; they had the reader skip to different

and agreed upon which ones to include, it is pages based on a decision the reader had the

advisable to photocopy, if possible, each “pen- characters make.

ciled” page before students begin “inking.” Many students may try to avoid being

Photocopy again, if possible, before the pages involved in any way with artwork, especially

are colored. This way the team will have back- if they feel it can lead to embarrassment. The

up originals in case a mistake is made. teacher can encourage students by working

Rather than having the students do their closely with the school’s art teachers on the

artwork directly on the three stapled A4 project, if that is an option. The teacher can

pages, it is easier to have them work with also tap into a variety of online resources

half sheets of A4 paper or even smaller pre- that take students step-by-step through the

cut panels and then glue them into a stapled sketching of people, objects, and scenery. As

booklet of blank pages. There are several with language learning itself, it is critical that

advantages to working this way. First, you teachers show some sense of risk-taking them-

avoid the confusion of having to keep in mind selves. Trial and error, mixed with a sense of

which page follows which when working with humor and a healthy dose of courage, are usu-

whole sheets of paper. Second, it avoids doing ally enough to get students beyond a simple

artwork on the back side of a page with other stick-figure approach to characters.

artwork, something that can prove messy Several alternatives to drawing offer dif-

and distracting to a reader depending on ferent approaches to the visual nature of the

the quality of the paper and the ink. Third, project. One of the simplest solutions is to

it adds extra weight to the finished product, trace characters from a magazine, book, or

giving it more durability and the heavier feel newspaper. The resulting realism can often

of a book. Finally, it provides the option of have a humorous effect. The disadvantage is

displaying the entire story on one large poster that if there is only one perspective of the

board instead of, or before, converting it into character, and the character appears in three

a book. This is an important advantage, as we or more panels, it can be monotonous for the

will see in Step 8. reader and the artwork can begin to lose its

The panels in most English language appeal.

comic books and graphic novels are read from More creative solutions involve avoiding

left to right, starting with the top row of pan- human characters altogether and personifying

els. Speech bubbles, thought clouds, and cap- objects or using symbols to represent those

tions within each panel are read in the same characters. In the Aral Sea story, homes, riv-

way—left to right, top to bottom. This should ers, and even rocks could be main characters.

be “discovered” by students when they answer Doonesbury, a popular comic strip in the

question six in Step 1, “Exploring sequential United States, has successfully used punctua-

art.” Students need to follow this convention tion marks and a cigarette with arms and legs

when creating their artwork in order to avoid as characters. Another possibility is to use

confusing the reader. (The only exception I pictures of people from magazines or newspa-

have come across in English language sequen- pers and to fill in only the background with

tial art is “native manga,” which maintains students’ artwork and text. And yet another

the authentic Japanese format of right to left approach that has worked well is to have stu-

E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M | NUMBER 3 2007 9

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 9 6/27/07 9:48:07 AM

dents take photos of themselves posing as the each work, choosing best stories, favorite

story requires, gluing the photos to the page, characters, funniest lines, and the most inter-

and then adding speech bubbles. For those esting scenes. The school’s administrators are

teachers with computers and basic graphics invited to hand out awards for the works that

software, scanned drawings or photos can be have generated the most interest, and a small

touched-up, cropped, and arranged on a page contribution from parents helps publish the

with inserted speech bubbles and thought winning works.

clouds. Yet another idea is to make a series Another follow-on project is for the stu-

of panels on the wall or floor and to then fill dents to act out their stories. Sequential art

them with life-size outlines of the characters lends itself well to dramatization because it

and have students color them in and add already contains visual cues and a script. In

speech bubbles. fact, several graphic novels have already served

Step 8: Sharing the finished product as storyboards for films, including Harvey

Pekar’s brilliant American Splendor. As speech

Ensuring a sense of audience from the very

bubbles are usually not enough to support the

start is an important part of any successful

story entirely, students should be encouraged

writing process. (Before beginning Step 1,

to add additional lines and scenes in order to

teachers will want to tell students what will

fill in any gaps in the storyline. Stories that

happen in Step 8.) Knowing their audience

jump often in time and space, as is the case

motivates students, stimulating interest in

with some graphic novels and comic books,

their topic and ensuring a higher regard for

usually require more effort. One possible twist

quality in their work. It also maximizes the

to this activity is to have other groups act out

language learning experience: students like

the story and then have the original artists or

to read and discuss the work of peers. In

other student groups rate the actors’ interpre-

this project, the added graphic dimension of

sequential art makes the finished product that tation of the story. A simpler approach is to

much more appealing. have other groups use the story as a roadmap

In order to create a visually stimulating for an oral re-telling of the story.

experience for all students, Bryan, Chilcoat Collecting and preserving the students’

and Morrison (2002) recommend a trade stories should be one of the teacher’s main

show in which each group displays their work. goals. A shelf or bookcase of the students’ cre-

The half A4 size pages can be mounted on a ations in the classroom will naturally attract

poster board, or even directly taped to the students and will motivate them to create

wall, for all to see. Students then move from high quality books, especially if they realize

story to story, taking notes on their favorite a younger brother or sister might read their

artwork, characters, scenes, quotes, and over- book in the future. The teacher can set up a

all stories. They should also jot down ques- classroom library with the works, assigning

tions they have for the groups. The teacher them as reading outside of class. The booklets

can provide a handout with evaluation criteria also serve as writing models when new groups

or write the criteria on the board to help guide of students begin working on new projects.

this process. Once this viewing phase is done, Another important step is to share the

each group discusses its work in front of the social concerns that have been addressed in

class and answers questions. the stories with the school community as a

The booklets can be shared with other whole. If an integrated approach to the cur-

classes as well. One of my English language riculum has been taken into consideration

teaching colleagues sets up a “Comics and from the beginning, with the topic fitting into

Graphic Novel Fair” every year in his school; a general theme that is being covered in one

at the fair, students’ creations are circulated or more other subjects, then there should be

and rated by a slightly younger group of read- an opportunity to make the artwork and story

ers. As students know this from the start, one part of a larger display at school. A school

of the goals of the story-writing process is to newspaper, wall board, and website are a few

try to create a storyline and characters that ways to showcase students’ work and bring

appeal specifically to younger readers. The attention to the issue. The neighborhood may

younger audience writes comments about have an art gallery or community center that

10 2007 NUMBER 3 | E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 10 6/27/07 9:48:07 AM

can also display the work. Finally, it is also filling students with an enhanced understand-

worth considering using work and research ing of the target language, the target language

that has gone into the sequential art project as culture, their own culture, and critical issues

a foundation for more sophisticated writing in the rapidly changing world around them.

projects such as newspaper articles and even

grant proposals. References

Bryan, G., G. W. Chilcoat, and T. G. Morrison.

Conclusion 2002. Pow! Zap! Wham! Creating comic books

The idea of using pictures to tell stories in social studies classrooms. Canadian Social

Studies 37 (1): 1–13.

in all likelihood predates the Altamira cave

http://www.quasar.ualberta.ca/css/Css_37_1/

drawings made 14,000 years ago. The inven- FTcomics_in_social_studies.htm.

tion of the alphabet gave us a more efficient Cary, S. 2004. Going Graphic: Comics at work

way to convey ideas, often relegating graphics in the multilingual classroom. Portsmouth:

to the role of supporting illustrations. While Heinemann.

there are excellent examples in the history of Chilcoat, G. W. 1993. Teaching about the civil

art of both literary and graphic forms merging rights movement by using student-generated

comic books. Social Studies 84: 113–120.

to tell a story, including the elegant Japanese

Chilcoat, G. W., and J. Ligon. 1994. The Under-

“Ehon” illustrations and the Soviet children’s ground Comix: A popular culture approach to

picture books of the 1920s and 1930s, none teaching historical, political and social issues of

of these forms “superimpose…the regimens of the sixties and seventies. Michigan Social Studies

art (e.g., perspective, symmetry, brush stroke) Journal 7 (1): 35–40.

and the regimens of literature (e.g., gram- Csabay, N. 2006. Using comic strips in language

class. English Teaching Forum 44 (1): 24–26.

mar, plot, syntax)…upon each other” (Eisner

Dorrell, L., and E. Carroll. 1981. Spider-Man at

1985, 8) in the same way that graphic novels the library. School Library Journal 27: 17–19.

or comic books do. Sequential art presents us Eisner, W. 1985. Comics and sequential art: Prin-

with a unique blend of the representational, ciples and practice of the world’s most popular art

or art itself, and the abstract, words. It cap- form. Paramus: Poorhouse Press.

tures human movement and communication Hayes, D., and M. Ahrens. 1988. Vocabulary sim-

on a page, in the here and now, unlike any plification for children: A special case of “moth-

erese”? Journal of Child Language 15: 395–410.

other art form or medium.

Krashen, S. 2004. The Power of Reading. Ports-

Sequential art offers students a power- mouth: Heinemann.

ful tool with which to express themselves. McCloud, S. 2006. Making comics. New York:

Whether “noodling,” a combination of note Harper Collins.

taking and doodling (Cary 2004, 146), cre- Mulholland, M. J. 2004. Comics as art therapy.

ating a three-panel cartoon to contextualize Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy

a newly learned idiom, or creating a short Association 21 (1): 42–43.

Ujiie, J., and S. Krashen. 1996a. Comic books read-

graphic novel to address a social concern, ing, reading enjoyment and pleasure reading

the art form should play a central role in the among middle class and chapter I middle school

learning of a language, native or foreign. It students. Reading Improvement 33 (1): 51–54.

can be as simple as putting pen to paper or Ujiie, J., And S. Krashen. 1996b. Is comic book

making sketches on the wall or blackboard. reading harmful? Comic book reading, school

It can be as sophisticated as posting episodes achievement, and pleasure reading among sev-

enth graders. California School Library Associa-

of a story on a website or self-publishing a

tion Journal 19 (2): 27–28.

book. In short, sequential art is an accessible Wertham, F. 1954. Seduction of the innocent. New

learning tool requiring the very minimum York: Rinehart.

of a drawing tool, a space on which to draw, Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aral_sea

and one’s imagination. “No matter how many Williams, N. 1995. The comic book as course

tons of ink we’ve spilled on it over the years,” book: Why and how. Paper presented at the

Scott McCloud explains, “comics itself has 29th international convention of Teachers of

English to Speakers of Other Languages, Long

always been a blank page for each new hand Beach, California.

that approaches” (2006, 252). The eight steps Wright, G., and R. Sherman. 1999. Let’s create

presented above should serve as an introduc- a comic strip. Reading Improvement 36 (2):

tion for filling in many blank pages and for 66–72.

Continued on page 21

E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M | NUMBER 3 2007 11

07-0003 ETF_02_11.indd 11 6/27/07 9:48:08 AM

tic about using the language for real, personal Murphey, T., and H. Arao. 2001. Reported belief

purposes through these materials has sold us changes through near peer role modeling. TESL-

EJ 5 (3): 1–15.

on this idea. We realize that, ironically, the

Tudor, I. 1996. Learner-centeredness as language

most valuable and overlooked resource in edu- education. Cambridge: Cambridge University

cation may be sitting right in front of every Press.

teacher. While teachers scramble to make Vygotsky, L. 1962. Thought and language. Cam-

and collect materials and try to imagine how bridge, MA: MIT Press.

students will react to them, an easily accessible

and reliable source of material walks in and HSIAO-YI (ISABELLE) CHOU graduated from the

out of their classrooms every day. But now MATESL program at Hawaii Pacific

you know. So go ahead—make a book with University in 2006. She taught children

your students. And prepare to be enthused! and adults for seven years in Taiwan after

receiving her BA in TESL.

References

SOK-HAN (MONICA) LAU graduated in 2006

Campbell, C., and H. Kryszewska. 1992. Learn- with a MATESL from Hawaii Pacific

er-based teaching. Oxford: Oxford University University. She has taught EFL in Macau for

Press. three years and plans to teach English to

Education World. Young authors and artists col-

children or adults.

laborate on humanitarian project. http://www.

educationworld.org/a_curr/curr253.shtml HUEI-CHIA (STEPHANIE) YANG graduated from

Murphey, T. 1993. Why don’t teachers learn what the MATESL program at Hawaii Pacific

learners learn? Taking the guesswork out with

University in December 2006. She will begin

action logging. English Teaching Forum 31 (1):

advanced studies in Japan in the fall of

6–10.

–––. 1999. Publishing students’ language learning 2007.

histories: For them, their peers, and their teach- TIM MURPHEY teaches at Dokkyo University,

ers. Between the Keys, the Newsletter of the JALT

Japan, and often spends summers as a

Material Writers SIG 7 (2): 8–11.

Murphey, T., J. Chen, and L.-C. Chen. 2005. visiting professor at Hawaii Pacific

Learners’ constructions of identities and imag- University. He taught in Switzerland,

ined communities. In Learners’ stories: Difference where he earned his PhD, and has taught

and diversity in language learning. ed. P. Benson English in Asia for the last 15 years. He is

and D. Nunan, 83–100. Cambridge: Cam- the series editor for TESOL’s Professional

bridge University Press. Development in Language Education.

Student Storytelling… David Fay

(Continued from page 11)

Websites of Interest Student-made Comics

Beginning drawing www.amazing-kids.org/index.html

www.fundoodle.com www.dubuque.k12.ia.us/Fulton/Cartoon_

www.unclefred.com Club/cartoonists/

www.ababasoft.com/how_to_draw/

Comics for social action

www.worldcomics.fi/home_about.shtml

Manga

www.emi-art.com/twtyh/main.html

Online comics DAVID FAY is the Regional English

www.comics.com Language Officer for Central Asia. Before

www.thecomicportal.com joining the State Department, he worked as

www.marvel.com a teacher and trainer in Turkey, Costa Rica,

www.comics.org Spain, and the United States.

E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M | NUMBER 3 2007 21

07-0003 ETF_18_23.indd 21 6/27/07 9:48:35 AM

Student Profile Questions

Appendix 1 for Middle School

Students as Textbook Authors • Hsiao-yi Chou, Sok-Han Lau, Huei-Chia Yang, and Tim Murphey

The Story of ________________ (your name)

My name is ________________.

I come from ______________.

My favorite subject in school is _____________.

My favorite sport is ______________.

I like to ________________.

I like to ________________.

I like to ________________.

I don’t like to _______________.

I don’t like to _______________.

I don’t like to _______________.

When I grow up, I would like to be a(n) _______________.

I think learning English is _________________.

I have been in Hawaii for _________________.

Draw any picture you like.

[This was the bottom half of an A4 sheet.]

22 2007 NUMBER 3 | E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M

07-0003 ETF_18_23.indd 22 6/27/07 9:48:36 AM

Ways to use a student-produced

Appendix 2 booklet

Students as Textbook Authors • Hsiao-yi Chou, Sok-Han Lau, Huei-Chia Yang, and Tim Murphey

1. Students read their own page silently, then out loud to a

partner.

2. Students describe their drawings.

3. Students read their classmates’ pages by changing the

subject of the sentence (e.g., My name is ______. His/her name

is _____.).

4. Students use teacher’s model of how to transform stem sentenc-

es to ask questions of other students (e.g., What is your name?

What do you like?).

5. Students ask about their friends’ drawings (What’s that?).

6. Students look at the photo on the back of the booklet with their

partners and try to name all of their classmates.

7. Students describe a classmate in the photo, and the partner tries

to guess who the person is.

8. After thoroughly familiarizing themselves with the contents of

the booklet, students describe someone’s likes and dislikes, and

their partners try to identify the person—if necessary, by refer-

ring back to the booklet.

9. The teacher chooses one of the students’ profiles, reads some

sentences from it, and has students guess which student was

described.

10. Students show their families their booklets and the next day

share with the class their families’ comments (e.g., My mother

said she liked____. My father said he liked____.)

E N G L I S H T E A C H I N G F O R U M | NUMBER 3 2007 23

07-0003 ETF_18_23.indd 23 6/27/07 9:48:36 AM

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Black Panther 1 Vol 1Document17 pagesBlack Panther 1 Vol 1SamsonSavage100% (7)

- Transformers Comic BookDocument32 pagesTransformers Comic BookIrish Man100% (3)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Marvel Zombies Complete List of Characters by ExpansionDocument28 pagesMarvel Zombies Complete List of Characters by ExpansionMichael Vincent QueNo ratings yet

- Riverdale Episode Script Transcript Season 1 01 Chapter One The Rivers EdgeDocument64 pagesRiverdale Episode Script Transcript Season 1 01 Chapter One The Rivers EdgeThiago LuizNo ratings yet

- 039 Asterix and The PictsDocument50 pages039 Asterix and The PictsColin Naturman95% (19)

- Peeter, B. Four Conceptions of The PageDocument19 pagesPeeter, B. Four Conceptions of The Pageginger_2011No ratings yet

- Ken Hultgren The Know How of Cartooning 1946Document65 pagesKen Hultgren The Know How of Cartooning 1946Igor Costa100% (6)

- TRANSLATION STRATEGIES FOR TRANSLATING A NEWS ARTIclesDocument12 pagesTRANSLATION STRATEGIES FOR TRANSLATING A NEWS ARTIclesStephanie Etsu Alvarado PérezNo ratings yet

- Taken From Teaching Young Learners English by Kang Shin, J. & Crandall, K. (2014) - National Geographic LearningDocument9 pagesTaken From Teaching Young Learners English by Kang Shin, J. & Crandall, K. (2014) - National Geographic LearningStephanie Etsu Alvarado PérezNo ratings yet

- Why Teach Learning StrategiesDocument13 pagesWhy Teach Learning StrategiesStephanie Etsu Alvarado PérezNo ratings yet

- The Sick Rose: by Lee HyoseokDocument16 pagesThe Sick Rose: by Lee HyoseokStephanie Etsu Alvarado PérezNo ratings yet

- (1945) Mary Marvel Story: Mary Marvel Meets Sivana's Daughter GeorgiaDocument7 pages(1945) Mary Marvel Story: Mary Marvel Meets Sivana's Daughter GeorgiaHerbert Hillary Booker 2nd100% (1)

- Survei Genre Webtoon Populer Di IndonesiaDocument23 pagesSurvei Genre Webtoon Populer Di IndonesiaHakkun ElmunsyahNo ratings yet

- English For Academic and Professional Purpose: ObjectivesDocument67 pagesEnglish For Academic and Professional Purpose: ObjectivesJhon Keneth NamiasNo ratings yet

- Comics in Translation An Overview PDFDocument32 pagesComics in Translation An Overview PDFGustavo BrunettiNo ratings yet

- Transformers Robots in Disguise Vol2Document106 pagesTransformers Robots in Disguise Vol2glenngriffonNo ratings yet

- Mapeh Week 8Document45 pagesMapeh Week 8Anne Bacnat GabionNo ratings yet

- Fax From Sarajevo PDFDocument2 pagesFax From Sarajevo PDFRituNo ratings yet

- Spiderman EssayDocument7 pagesSpiderman Essayapi-235303707No ratings yet

- Conditional Questions For Conversation PracticeDocument2 pagesConditional Questions For Conversation PracticeDiegoNo ratings yet

- Comic - Con en InglésDocument2 pagesComic - Con en InglésMarisa Elizabeth MedinaNo ratings yet

- Not Superhero Accessible The Temporal Stickiness of Disability in Superhero ComicsDocument23 pagesNot Superhero Accessible The Temporal Stickiness of Disability in Superhero ComicsBruno SoaresNo ratings yet

- Anarky 4Document1 pageAnarky 4LuckyNo ratings yet

- Heroclix DC - Hypertime Powers and Abilities Card (2002)Document2 pagesHeroclix DC - Hypertime Powers and Abilities Card (2002)mrtibblesNo ratings yet

- Rare Comic Books - 35 Cent Variant GuideDocument20 pagesRare Comic Books - 35 Cent Variant GuideVic JNo ratings yet

- Autobiographical ComicsDocument301 pagesAutobiographical Comicshannahso99100% (1)

- Bleach, Chapter 644 TcbScans Net - Free Manga Online in High QualityDocument1 pageBleach, Chapter 644 TcbScans Net - Free Manga Online in High QualitymichaelsNo ratings yet

- Storyboard Comics - Transition YearDocument4 pagesStoryboard Comics - Transition Yearapi-254225837No ratings yet

- TulikaDocument8 pagesTulikaTERENDER SINGHNo ratings yet

- Heroclix - Additional Team Abilities - DCDocument17 pagesHeroclix - Additional Team Abilities - DCCobralaNo ratings yet

- Sex Exclusive PreviewDocument4 pagesSex Exclusive PreviewUSA TODAY Comics0% (2)

- Flash Rebirth 001Document2 pagesFlash Rebirth 001Murra MacRoryNo ratings yet

- Lee V Marvel 2002 MSJ Marvel Defines Nov 98 KDocument7 pagesLee V Marvel 2002 MSJ Marvel Defines Nov 98 Kstanleemedia4No ratings yet

- The Golden Age of Comic Books - Representations of American CulturDocument14 pagesThe Golden Age of Comic Books - Representations of American CulturGasterSparda8No ratings yet